Skip to content

Read the latest news stories about Mailman faculty, research, and events.

Departments

We integrate an innovative skills-based curriculum, research collaborations, and hands-on field experience to prepare students.

Learn more about our research centers, which focus on critical issues in public health.

Our Faculty

Meet the faculty of the Mailman School of Public Health.

Become a Student

Life and community, how to apply.

Learn how to apply to the Mailman School of Public Health.

Content Analysis

Content analysis is a research tool used to determine the presence of certain words, themes, or concepts within some given qualitative data (i.e. text). Using content analysis, researchers can quantify and analyze the presence, meanings, and relationships of such certain words, themes, or concepts. As an example, researchers can evaluate language used within a news article to search for bias or partiality. Researchers can then make inferences about the messages within the texts, the writer(s), the audience, and even the culture and time of surrounding the text.

Description

Sources of data could be from interviews, open-ended questions, field research notes, conversations, or literally any occurrence of communicative language (such as books, essays, discussions, newspaper headlines, speeches, media, historical documents). A single study may analyze various forms of text in its analysis. To analyze the text using content analysis, the text must be coded, or broken down, into manageable code categories for analysis (i.e. “codes”). Once the text is coded into code categories, the codes can then be further categorized into “code categories” to summarize data even further.

Three different definitions of content analysis are provided below.

Definition 1: “Any technique for making inferences by systematically and objectively identifying special characteristics of messages.” (from Holsti, 1968)

Definition 2: “An interpretive and naturalistic approach. It is both observational and narrative in nature and relies less on the experimental elements normally associated with scientific research (reliability, validity, and generalizability) (from Ethnography, Observational Research, and Narrative Inquiry, 1994-2012).

Definition 3: “A research technique for the objective, systematic and quantitative description of the manifest content of communication.” (from Berelson, 1952)

Uses of Content Analysis

Identify the intentions, focus or communication trends of an individual, group or institution

Describe attitudinal and behavioral responses to communications

Determine the psychological or emotional state of persons or groups

Reveal international differences in communication content

Reveal patterns in communication content

Pre-test and improve an intervention or survey prior to launch

Analyze focus group interviews and open-ended questions to complement quantitative data

Types of Content Analysis

There are two general types of content analysis: conceptual analysis and relational analysis. Conceptual analysis determines the existence and frequency of concepts in a text. Relational analysis develops the conceptual analysis further by examining the relationships among concepts in a text. Each type of analysis may lead to different results, conclusions, interpretations and meanings.

Conceptual Analysis

Typically people think of conceptual analysis when they think of content analysis. In conceptual analysis, a concept is chosen for examination and the analysis involves quantifying and counting its presence. The main goal is to examine the occurrence of selected terms in the data. Terms may be explicit or implicit. Explicit terms are easy to identify. Coding of implicit terms is more complicated: you need to decide the level of implication and base judgments on subjectivity (an issue for reliability and validity). Therefore, coding of implicit terms involves using a dictionary or contextual translation rules or both.

To begin a conceptual content analysis, first identify the research question and choose a sample or samples for analysis. Next, the text must be coded into manageable content categories. This is basically a process of selective reduction. By reducing the text to categories, the researcher can focus on and code for specific words or patterns that inform the research question.

General steps for conducting a conceptual content analysis:

1. Decide the level of analysis: word, word sense, phrase, sentence, themes

2. Decide how many concepts to code for: develop a pre-defined or interactive set of categories or concepts. Decide either: A. to allow flexibility to add categories through the coding process, or B. to stick with the pre-defined set of categories.

Option A allows for the introduction and analysis of new and important material that could have significant implications to one’s research question.

Option B allows the researcher to stay focused and examine the data for specific concepts.

3. Decide whether to code for existence or frequency of a concept. The decision changes the coding process.

When coding for the existence of a concept, the researcher would count a concept only once if it appeared at least once in the data and no matter how many times it appeared.

When coding for the frequency of a concept, the researcher would count the number of times a concept appears in a text.

4. Decide on how you will distinguish among concepts:

Should text be coded exactly as they appear or coded as the same when they appear in different forms? For example, “dangerous” vs. “dangerousness”. The point here is to create coding rules so that these word segments are transparently categorized in a logical fashion. The rules could make all of these word segments fall into the same category, or perhaps the rules can be formulated so that the researcher can distinguish these word segments into separate codes.

What level of implication is to be allowed? Words that imply the concept or words that explicitly state the concept? For example, “dangerous” vs. “the person is scary” vs. “that person could cause harm to me”. These word segments may not merit separate categories, due the implicit meaning of “dangerous”.

5. Develop rules for coding your texts. After decisions of steps 1-4 are complete, a researcher can begin developing rules for translation of text into codes. This will keep the coding process organized and consistent. The researcher can code for exactly what he/she wants to code. Validity of the coding process is ensured when the researcher is consistent and coherent in their codes, meaning that they follow their translation rules. In content analysis, obeying by the translation rules is equivalent to validity.

6. Decide what to do with irrelevant information: should this be ignored (e.g. common English words like “the” and “and”), or used to reexamine the coding scheme in the case that it would add to the outcome of coding?

7. Code the text: This can be done by hand or by using software. By using software, researchers can input categories and have coding done automatically, quickly and efficiently, by the software program. When coding is done by hand, a researcher can recognize errors far more easily (e.g. typos, misspelling). If using computer coding, text could be cleaned of errors to include all available data. This decision of hand vs. computer coding is most relevant for implicit information where category preparation is essential for accurate coding.

8. Analyze your results: Draw conclusions and generalizations where possible. Determine what to do with irrelevant, unwanted, or unused text: reexamine, ignore, or reassess the coding scheme. Interpret results carefully as conceptual content analysis can only quantify the information. Typically, general trends and patterns can be identified.

Relational Analysis

Relational analysis begins like conceptual analysis, where a concept is chosen for examination. However, the analysis involves exploring the relationships between concepts. Individual concepts are viewed as having no inherent meaning and rather the meaning is a product of the relationships among concepts.

To begin a relational content analysis, first identify a research question and choose a sample or samples for analysis. The research question must be focused so the concept types are not open to interpretation and can be summarized. Next, select text for analysis. Select text for analysis carefully by balancing having enough information for a thorough analysis so results are not limited with having information that is too extensive so that the coding process becomes too arduous and heavy to supply meaningful and worthwhile results.

There are three subcategories of relational analysis to choose from prior to going on to the general steps.

Affect extraction: an emotional evaluation of concepts explicit in a text. A challenge to this method is that emotions can vary across time, populations, and space. However, it could be effective at capturing the emotional and psychological state of the speaker or writer of the text.

Proximity analysis: an evaluation of the co-occurrence of explicit concepts in the text. Text is defined as a string of words called a “window” that is scanned for the co-occurrence of concepts. The result is the creation of a “concept matrix”, or a group of interrelated co-occurring concepts that would suggest an overall meaning.

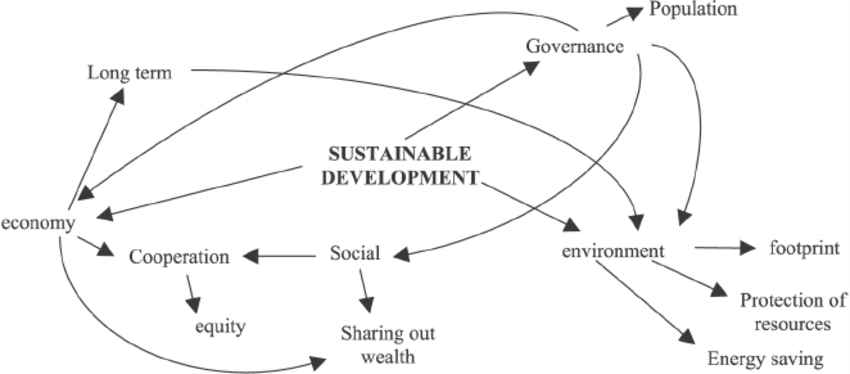

Cognitive mapping: a visualization technique for either affect extraction or proximity analysis. Cognitive mapping attempts to create a model of the overall meaning of the text such as a graphic map that represents the relationships between concepts.

General steps for conducting a relational content analysis:

1. Determine the type of analysis: Once the sample has been selected, the researcher needs to determine what types of relationships to examine and the level of analysis: word, word sense, phrase, sentence, themes. 2. Reduce the text to categories and code for words or patterns. A researcher can code for existence of meanings or words. 3. Explore the relationship between concepts: once the words are coded, the text can be analyzed for the following:

Strength of relationship: degree to which two or more concepts are related.

Sign of relationship: are concepts positively or negatively related to each other?

Direction of relationship: the types of relationship that categories exhibit. For example, “X implies Y” or “X occurs before Y” or “if X then Y” or if X is the primary motivator of Y.

4. Code the relationships: a difference between conceptual and relational analysis is that the statements or relationships between concepts are coded. 5. Perform statistical analyses: explore differences or look for relationships among the identified variables during coding. 6. Map out representations: such as decision mapping and mental models.

Reliability and Validity

Reliability : Because of the human nature of researchers, coding errors can never be eliminated but only minimized. Generally, 80% is an acceptable margin for reliability. Three criteria comprise the reliability of a content analysis:

Stability: the tendency for coders to consistently re-code the same data in the same way over a period of time.

Reproducibility: tendency for a group of coders to classify categories membership in the same way.

Accuracy: extent to which the classification of text corresponds to a standard or norm statistically.

Validity : Three criteria comprise the validity of a content analysis:

Closeness of categories: this can be achieved by utilizing multiple classifiers to arrive at an agreed upon definition of each specific category. Using multiple classifiers, a concept category that may be an explicit variable can be broadened to include synonyms or implicit variables.

Conclusions: What level of implication is allowable? Do conclusions correctly follow the data? Are results explainable by other phenomena? This becomes especially problematic when using computer software for analysis and distinguishing between synonyms. For example, the word “mine,” variously denotes a personal pronoun, an explosive device, and a deep hole in the ground from which ore is extracted. Software can obtain an accurate count of that word’s occurrence and frequency, but not be able to produce an accurate accounting of the meaning inherent in each particular usage. This problem could throw off one’s results and make any conclusion invalid.

Generalizability of the results to a theory: dependent on the clear definitions of concept categories, how they are determined and how reliable they are at measuring the idea one is seeking to measure. Generalizability parallels reliability as much of it depends on the three criteria for reliability.

Advantages of Content Analysis

Directly examines communication using text

Allows for both qualitative and quantitative analysis

Provides valuable historical and cultural insights over time

Allows a closeness to data

Coded form of the text can be statistically analyzed

Unobtrusive means of analyzing interactions

Provides insight into complex models of human thought and language use

When done well, is considered a relatively “exact” research method

Content analysis is a readily-understood and an inexpensive research method

A more powerful tool when combined with other research methods such as interviews, observation, and use of archival records. It is very useful for analyzing historical material, especially for documenting trends over time.

Disadvantages of Content Analysis

Can be extremely time consuming

Is subject to increased error, particularly when relational analysis is used to attain a higher level of interpretation

Is often devoid of theoretical base, or attempts too liberally to draw meaningful inferences about the relationships and impacts implied in a study

Is inherently reductive, particularly when dealing with complex texts

Tends too often to simply consist of word counts

Often disregards the context that produced the text, as well as the state of things after the text is produced

Can be difficult to automate or computerize

Textbooks & Chapters

Berelson, Bernard. Content Analysis in Communication Research.New York: Free Press, 1952.

Busha, Charles H. and Stephen P. Harter. Research Methods in Librarianship: Techniques and Interpretation.New York: Academic Press, 1980.

de Sola Pool, Ithiel. Trends in Content Analysis. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1959.

Krippendorff, Klaus. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1980.

Fielding, NG & Lee, RM. Using Computers in Qualitative Research. SAGE Publications, 1991. (Refer to Chapter by Seidel, J. ‘Method and Madness in the Application of Computer Technology to Qualitative Data Analysis’.)

Methodological Articles

Hsieh HF & Shannon SE. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.Qualitative Health Research. 15(9): 1277-1288.

Elo S, Kaarianinen M, Kanste O, Polkki R, Utriainen K, & Kyngas H. (2014). Qualitative Content Analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. Sage Open. 4:1-10.

Application Articles

Abroms LC, Padmanabhan N, Thaweethai L, & Phillips T. (2011). iPhone Apps for Smoking Cessation: A content analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 40(3):279-285.

Ullstrom S. Sachs MA, Hansson J, Ovretveit J, & Brommels M. (2014). Suffering in Silence: a qualitative study of second victims of adverse events. British Medical Journal, Quality & Safety Issue. 23:325-331.

Owen P. (2012).Portrayals of Schizophrenia by Entertainment Media: A Content Analysis of Contemporary Movies. Psychiatric Services. 63:655-659.

Choosing whether to conduct a content analysis by hand or by using computer software can be difficult. Refer to ‘Method and Madness in the Application of Computer Technology to Qualitative Data Analysis’ listed above in “Textbooks and Chapters” for a discussion of the issue.

QSR NVivo: http://www.qsrinternational.com/products.aspx

Atlas.ti: http://www.atlasti.com/webinars.html

R- RQDA package: http://rqda.r-forge.r-project.org/

Rolly Constable, Marla Cowell, Sarita Zornek Crawford, David Golden, Jake Hartvigsen, Kathryn Morgan, Anne Mudgett, Kris Parrish, Laura Thomas, Erika Yolanda Thompson, Rosie Turner, and Mike Palmquist. (1994-2012). Ethnography, Observational Research, and Narrative Inquiry. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University. Available at: https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide.cfm?guideid=63 .

As an introduction to Content Analysis by Michael Palmquist, this is the main resource on Content Analysis on the Web. It is comprehensive, yet succinct. It includes examples and an annotated bibliography. The information contained in the narrative above draws heavily from and summarizes Michael Palmquist’s excellent resource on Content Analysis but was streamlined for the purpose of doctoral students and junior researchers in epidemiology.

At Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, more detailed training is available through the Department of Sociomedical Sciences- P8785 Qualitative Research Methods.

Join the Conversation

Have a question about methods? Join us on Facebook

What Is Qualitative Content Analysis?

Qca explained simply (with examples).

By: Jenna Crosley (PhD). Reviewed by: Dr Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | February 2021

If you’re in the process of preparing for your dissertation, thesis or research project, you’ve probably encountered the term “ qualitative content analysis ” – it’s quite a mouthful. If you’ve landed on this post, you’re probably a bit confused about it. Well, the good news is that you’ve come to the right place…

Overview: Qualitative Content Analysis

- What (exactly) is qualitative content analysis

- The two main types of content analysis

- When to use content analysis

- How to conduct content analysis (the process)

- The advantages and disadvantages of content analysis

1. What is content analysis?

Content analysis is a qualitative analysis method that focuses on recorded human artefacts such as manuscripts, voice recordings and journals. Content analysis investigates these written, spoken and visual artefacts without explicitly extracting data from participants – this is called unobtrusive research.

In other words, with content analysis, you don’t necessarily need to interact with participants (although you can if necessary); you can simply analyse the data that they have already produced. With this type of analysis, you can analyse data such as text messages, books, Facebook posts, videos, and audio (just to mention a few).

The basics – explicit and implicit content

When working with content analysis, explicit and implicit content will play a role. Explicit data is transparent and easy to identify, while implicit data is that which requires some form of interpretation and is often of a subjective nature. Sounds a bit fluffy? Here’s an example:

Joe: Hi there, what can I help you with?

Lauren: I recently adopted a puppy and I’m worried that I’m not feeding him the right food. Could you please advise me on what I should be feeding?

Joe: Sure, just follow me and I’ll show you. Do you have any other pets?

Lauren: Only one, and it tweets a lot!

In this exchange, the explicit data indicates that Joe is helping Lauren to find the right puppy food. Lauren asks Joe whether she has any pets aside from her puppy. This data is explicit because it requires no interpretation.

On the other hand, implicit data , in this case, includes the fact that the speakers are in a pet store. This information is not clearly stated but can be inferred from the conversation, where Joe is helping Lauren to choose pet food. An additional piece of implicit data is that Lauren likely has some type of bird as a pet. This can be inferred from the way that Lauren states that her pet “tweets”.

As you can see, explicit and implicit data both play a role in human interaction and are an important part of your analysis. However, it’s important to differentiate between these two types of data when you’re undertaking content analysis. Interpreting implicit data can be rather subjective as conclusions are based on the researcher’s interpretation. This can introduce an element of bias , which risks skewing your results.

2. The two types of content analysis

Now that you understand the difference between implicit and explicit data, let’s move on to the two general types of content analysis : conceptual and relational content analysis. Importantly, while conceptual and relational content analysis both follow similar steps initially, the aims and outcomes of each are different.

Conceptual analysis focuses on the number of times a concept occurs in a set of data and is generally focused on explicit data. For example, if you were to have the following conversation:

Marie: She told me that she has three cats.

Jean: What are her cats’ names?

Marie: I think the first one is Bella, the second one is Mia, and… I can’t remember the third cat’s name.

In this data, you can see that the word “cat” has been used three times. Through conceptual content analysis, you can deduce that cats are the central topic of the conversation. You can also perform a frequency analysis , where you assess the term’s frequency in the data. For example, in the exchange above, the word “cat” makes up 9% of the data. In other words, conceptual analysis brings a little bit of quantitative analysis into your qualitative analysis.

As you can see, the above data is without interpretation and focuses on explicit data . Relational content analysis, on the other hand, takes a more holistic view by focusing more on implicit data in terms of context, surrounding words and relationships.

There are three types of relational analysis:

- Affect extraction

- Proximity analysis

- Cognitive mapping

Affect extraction is when you assess concepts according to emotional attributes. These emotions are typically mapped on scales, such as a Likert scale or a rating scale ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 is “very sad” and 5 is “very happy”.

If participants are talking about their achievements, they are likely to be given a score of 4 or 5, depending on how good they feel about it. If a participant is describing a traumatic event, they are likely to have a much lower score, either 1 or 2.

Proximity analysis identifies explicit terms (such as those found in a conceptual analysis) and the patterns in terms of how they co-occur in a text. In other words, proximity analysis investigates the relationship between terms and aims to group these to extract themes and develop meaning.

Proximity analysis is typically utilised when you’re looking for hard facts rather than emotional, cultural, or contextual factors. For example, if you were to analyse a political speech, you may want to focus only on what has been said, rather than implications or hidden meanings. To do this, you would make use of explicit data, discounting any underlying meanings and implications of the speech.

Lastly, there’s cognitive mapping, which can be used in addition to, or along with, proximity analysis. Cognitive mapping involves taking different texts and comparing them in a visual format – i.e. a cognitive map. Typically, you’d use cognitive mapping in studies that assess changes in terms, definitions, and meanings over time. It can also serve as a way to visualise affect extraction or proximity analysis and is often presented in a form such as a graphic map.

To recap on the essentials, content analysis is a qualitative analysis method that focuses on recorded human artefacts . It involves both conceptual analysis (which is more numbers-based) and relational analysis (which focuses on the relationships between concepts and how they’re connected).

Need a helping hand?

3. When should you use content analysis?

Content analysis is a useful tool that provides insight into trends of communication . For example, you could use a discussion forum as the basis of your analysis and look at the types of things the members talk about as well as how they use language to express themselves. Content analysis is flexible in that it can be applied to the individual, group, and institutional level.

Content analysis is typically used in studies where the aim is to better understand factors such as behaviours, attitudes, values, emotions, and opinions . For example, you could use content analysis to investigate an issue in society, such as miscommunication between cultures. In this example, you could compare patterns of communication in participants from different cultures, which will allow you to create strategies for avoiding misunderstandings in intercultural interactions.

Another example could include conducting content analysis on a publication such as a book. Here you could gather data on the themes, topics, language use and opinions reflected in the text to draw conclusions regarding the political (such as conservative or liberal) leanings of the publication.

4. How to conduct a qualitative content analysis

Conceptual and relational content analysis differ in terms of their exact process ; however, there are some similarities. Let’s have a look at these first – i.e., the generic process:

- Recap on your research questions

- Undertake bracketing to identify biases

- Operationalise your variables and develop a coding scheme

- Code the data and undertake your analysis

Step 1 – Recap on your research questions

It’s always useful to begin a project with research questions , or at least with an idea of what you are looking for. In fact, if you’ve spent time reading this blog, you’ll know that it’s useful to recap on your research questions, aims and objectives when undertaking pretty much any research activity. In the context of content analysis, it’s difficult to know what needs to be coded and what doesn’t, without a clear view of the research questions.

For example, if you were to code a conversation focused on basic issues of social justice, you may be met with a wide range of topics that may be irrelevant to your research. However, if you approach this data set with the specific intent of investigating opinions on gender issues, you will be able to focus on this topic alone, which would allow you to code only what you need to investigate.

Step 2 – Reflect on your personal perspectives and biases

It’s vital that you reflect on your own pre-conception of the topic at hand and identify the biases that you might drag into your content analysis – this is called “ bracketing “. By identifying this upfront, you’ll be more aware of them and less likely to have them subconsciously influence your analysis.

For example, if you were to investigate how a community converses about unequal access to healthcare, it is important to assess your views to ensure that you don’t project these onto your understanding of the opinions put forth by the community. If you have access to medical aid, for instance, you should not allow this to interfere with your examination of unequal access.

Step 3 – Operationalise your variables and develop a coding scheme

Next, you need to operationalise your variables . But what does that mean? Simply put, it means that you have to define each variable or construct . Give every item a clear definition – what does it mean (include) and what does it not mean (exclude). For example, if you were to investigate children’s views on healthy foods, you would first need to define what age group/range you’re looking at, and then also define what you mean by “healthy foods”.

In combination with the above, it is important to create a coding scheme , which will consist of information about your variables (how you defined each variable), as well as a process for analysing the data. For this, you would refer back to how you operationalised/defined your variables so that you know how to code your data.

For example, when coding, when should you code a food as “healthy”? What makes a food choice healthy? Is it the absence of sugar or saturated fat? Is it the presence of fibre and protein? It’s very important to have clearly defined variables to achieve consistent coding – without this, your analysis will get very muddy, very quickly.

Step 4 – Code and analyse the data

The next step is to code the data. At this stage, there are some differences between conceptual and relational analysis.

As described earlier in this post, conceptual analysis looks at the existence and frequency of concepts, whereas a relational analysis looks at the relationships between concepts. For both types of analyses, it is important to pre-select a concept that you wish to assess in your data. Using the example of studying children’s views on healthy food, you could pre-select the concept of “healthy food” and assess the number of times the concept pops up in your data.

Here is where conceptual and relational analysis start to differ.

At this stage of conceptual analysis , it is necessary to decide on the level of analysis you’ll perform on your data, and whether this will exist on the word, phrase, sentence, or thematic level. For example, will you code the phrase “healthy food” on its own? Will you code each term relating to healthy food (e.g., broccoli, peaches, bananas, etc.) with the code “healthy food” or will these be coded individually? It is very important to establish this from the get-go to avoid inconsistencies that could result in you having to code your data all over again.

On the other hand, relational analysis looks at the type of analysis. So, will you use affect extraction? Proximity analysis? Cognitive mapping? A mix? It’s vital to determine the type of analysis before you begin to code your data so that you can maintain the reliability and validity of your research .

How to conduct conceptual analysis

First, let’s have a look at the process for conceptual analysis.

Once you’ve decided on your level of analysis, you need to establish how you will code your concepts, and how many of these you want to code. Here you can choose whether you want to code in a deductive or inductive manner. Just to recap, deductive coding is when you begin the coding process with a set of pre-determined codes, whereas inductive coding entails the codes emerging as you progress with the coding process. Here it is also important to decide what should be included and excluded from your analysis, and also what levels of implication you wish to include in your codes.

For example, if you have the concept of “tall”, can you include “up in the clouds”, derived from the sentence, “the giraffe’s head is up in the clouds” in the code, or should it be a separate code? In addition to this, you need to know what levels of words may be included in your codes or not. For example, if you say, “the panda is cute” and “look at the panda’s cuteness”, can “cute” and “cuteness” be included under the same code?

Once you’ve considered the above, it’s time to code the text . We’ve already published a detailed post about coding , so we won’t go into that process here. Once you’re done coding, you can move on to analysing your results. This is where you will aim to find generalisations in your data, and thus draw your conclusions .

How to conduct relational analysis

Now let’s return to relational analysis.

As mentioned, you want to look at the relationships between concepts . To do this, you’ll need to create categories by reducing your data (in other words, grouping similar concepts together) and then also code for words and/or patterns. These are both done with the aim of discovering whether these words exist, and if they do, what they mean.

Your next step is to assess your data and to code the relationships between your terms and meanings, so that you can move on to your final step, which is to sum up and analyse the data.

To recap, it’s important to start your analysis process by reviewing your research questions and identifying your biases . From there, you need to operationalise your variables, code your data and then analyse it.

5. What are the pros & cons of content analysis?

One of the main advantages of content analysis is that it allows you to use a mix of quantitative and qualitative research methods, which results in a more scientifically rigorous analysis.

For example, with conceptual analysis, you can count the number of times that a term or a code appears in a dataset, which can be assessed from a quantitative standpoint. In addition to this, you can then use a qualitative approach to investigate the underlying meanings of these and relationships between them.

Content analysis is also unobtrusive and therefore poses fewer ethical issues than some other analysis methods. As the content you’ll analyse oftentimes already exists, you’ll analyse what has been produced previously, and so you won’t have to collect data directly from participants. When coded correctly, data is analysed in a very systematic and transparent manner, which means that issues of replicability (how possible it is to recreate research under the same conditions) are reduced greatly.

On the downside , qualitative research (in general, not just content analysis) is often critiqued for being too subjective and for not being scientifically rigorous enough. This is where reliability (how replicable a study is by other researchers) and validity (how suitable the research design is for the topic being investigated) come into play – if you take these into account, you’ll be on your way to achieving sound research results.

Recap: Qualitative content analysis

In this post, we’ve covered a lot of ground – click on any of the sections to recap:

If you have any questions about qualitative content analysis, feel free to leave a comment below. If you’d like 1-on-1 help with your qualitative content analysis, be sure to book an initial consultation with one of our friendly Research Coaches.

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

13 Comments

If I am having three pre-decided attributes for my research based on which a set of semi-structured questions where asked then should I conduct a conceptual content analysis or relational content analysis. please note that all three attributes are different like Agility, Resilience and AI.

Thank you very much. I really enjoyed every word.

please send me one/ two sample of content analysis

send me to any sample of qualitative content analysis as soon as possible

Many thanks for the brilliant explanation. Do you have a sample practical study of a foreign policy using content analysis?

1) It will be very much useful if a small but complete content analysis can be sent, from research question to coding and analysis. 2) Is there any software by which qualitative content analysis can be done?

Common software for qualitative analysis is nVivo, and quantitative analysis is IBM SPSS

Thank you. Can I have at least 2 copies of a sample analysis study as my reference?

Could you please send me some sample of textbook content analysis?

Can I send you my research topic, aims, objectives and questions to give me feedback on them?

please could you send me samples of content analysis?

really we enjoyed your knowledge thanks allot. from Ethiopia

can you please share some samples of content analysis(relational)? I am a bit confused about processing the analysis part

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

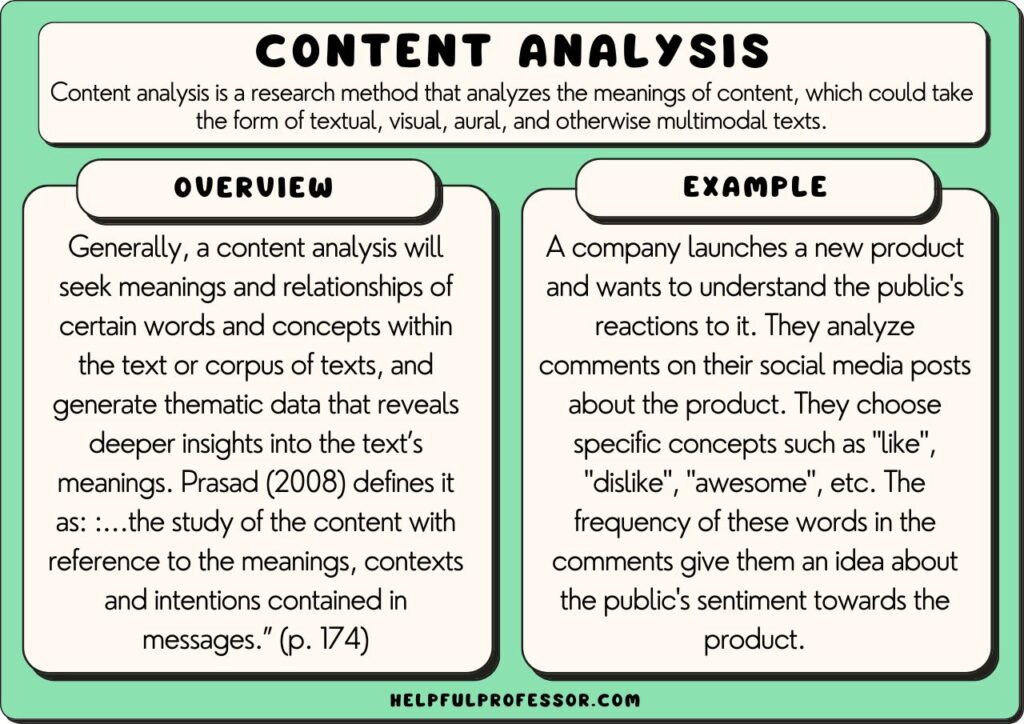

10 Content Analysis Examples

Content analysis is a research method and type of textual analysis that analyzes the meanings of content , which could take the form of textual, visual, aural, and otherwise multimodal texts.

Generally, a content analysis will seek meanings and relationships of certain words and concepts within the text or corpus of texts, and generate thematic data that reveals deeper insights into the text’s meanings.

Prasad (2008) defines it as:

:…the study of the content with reference to the meanings, contexts and intentions contained in messages.” (p. 174)

Content analyses can involve deductive coding , where themes and concepts are asserted before the content is created; or, they can involve inductive coding , where themes and concepts emerge during a close reading of the text.

An example of a content analysis would be a study that analyzes the presence of ideological words and phrases in newspapers to ascertain the editorial team’s political biases.

Content Analysis Examples

1. conceptual analysis.

Also called semantic content analysis, a conceptual analysis selects a concept and tries to count its occurrence within a text (Kosterec, 2016).

An example of a concept that you might examine is sentiment, such as positive, negative, and neutral sentiment. Here, you would need to conduct a semantic study of the text to find instances of words like ‘bad’, ‘terrible’, etc. for negative sentiment, and ‘good’, ‘great’, etc. for positive sentiment. A compare and contrast will demonstrate a balance of sentiment within the text.

A basic conceptual analysis has the weakness of lacking the capacity to read words in context, which would require a deeper qualitative analysis of paragraphs, which is offset by other types of analysis in this list.

Example of Conceptual Analysis

A company launches a new product and wants to understand the public’s initial reactions to it. They use conceptual analysis to analyze comments on their social media posts about the product. They could choose specific concepts such as “like”, “dislike”, “awesome”, “terrible”, etc. The frequency of these words in the comments give them an idea about the public’s sentiment towards the product.

2. Relational Analysis

Relational analysis addresses the above-mentioned weakness of conceptual analysis (i.e. that a mere counting of instances of terms lacks context) by examining how concepts in a text relate to one another .

Here, a scholar might analyze the overlap or sequences between certain concepts and sentiments in language (Kosterec, 2016). To combine the two examples from the above conceptual analysis, a scholar might examine all of a particular masthead newspaper’s columns on global warming. In the study, they would examine the proximity between the word ‘global warming’ and positive, negative, and neutral sentiment words (‘good’, ‘bad’, ‘great’, etc.) to ascertain the newspaper’s sentiment toward a specific concept .

Example of Relational Analysis

A political scientist wants to understand the relationship between the use of emotional rhetoric and audience reaction in political speeches. They carry out a relational analysis on a corpus of speeches and corresponding audience feedback. By exploring the co-occurrence of emotive words (“hope”, “fear”, “pride”) and audience responses (“applause”, “boos”, “silence”), they discover patterns in how different types of emotional language affect audience reactions.

3. Thematic Analysis

A thematic analysis focuses on identifying themes or major ideas running throughout the text.

This can follow a range of strategies, spanning from highly quantitative – such as using statistical software to thematically group words and terms – through to highly qualitative, where trained researchers take notes on each paragraph to extract key ideas that can be thematicized.

Many literature reviews take the form of a thematic analysis, where the scholar reads all recent studies on a topic and tries to ascertain themes, as well as gaps, across the recent literature.

Example of Thematic Analysis

A scholar searches on research bases for all published academic papers containing the keyword “back pain” from the past 10 years. She then uses inductive coding to generate themes that span the studies. From this thematic analysis, she produces a literature review on key emergent themes from the literature on back pain, as well as gaps in the research.

4. Narrative Analysis

This involves a close reading of the framing and structure of narrative elements within content. It can examine personal life stories, biographies, journals, and so on.

In literary research, this method generally explores the elements of the story , such as characters, plot, literary themes , and settings. But in life history research, it will generally involve deconstructing a real person’s life story, analyzing their perspectives and worldview to develop insights into their unique situation, life circumstances, or personality.

The focus generally expands out from the story itself to what it can tell us about the individuals or culture from which it originates.

Example of Narrative Analysis

A social work researcher takes a group of their patients’ personal journals and, after obtaining ethics clearance and permission from the patients, deconstructs the underlying messages in their journals in order to extract an understanding of the core mental hurdles each patient faces, which are then analyzed through the lens of Jungian psychoanalysis.

5. Discourse Analysis

Discourse analysis, the research methodology from which I conducted my PhD studies, involves the study of how language can create and reproduce social realities.

Based on the work of postmodern scholars such as Michel Foucault and Jaques Derrida, it attempts to deconstruct how texts normalize ways of thinking within specific historical, cultural, and social contexts .

Foucault, the most influential scholar in discourse analytic research, demonstrated through the study of how society spoke about madness that different societies constructed madness in different ways: in the renaissance era, mad people we spoken of as wise people, during the classical era, language changed, and they were framed as pariahs. Finally, in the modern era, they were spoken about as if they were sick.

Following Foucault (1988), many content analysis scholars now look at the differing ways societies frame different identities (gender, race, social class, etc.) in different times – and this can be revealed by looking at the language used in the content (i.e. the texts) produced throughout different eras (Johnstone, 2017).

Example of Discourse Analysis

A scholar examines a corpus of immigration speeches from a specific political party from the past 10 years and examines how refugees are discussed in the speeches, with a focus on how language constructs and defines refugees. It finds that refugees appear to be constructed as threats, dirty, and nefarious.

See Here for 10 More Examples of Discourse Analysis

6. Multimodal Analysis

As audiovisual texts became more important in society, many scholars began to critique the fact that content analysis tends to only look at written texts. In response, a methodology called multimodal analysis emerged.

In multimodal analysis, scholars don’t just decode the meanings in written texts, but also in multimodal texts . This involves the study of the signs, symbols, movements, and sounds that are within the text.

This opens up space for the analysis of television advertisements, billboards, and so forth.

For an example, a multimodal analysis of a television advertisement might not just study what is said, but it’ll explore how the camera angles frame some people as powerful (low to high angle) and some people as weak (high to low angle). Similarly, they may examine the colors to see if a character is positioned as sad (dark colors, walking through rain) or joyful (bright colors, sunshine).

Example of Multimodal Analysis

A cultural studies scholar examines the representation of Gender in Disney films, looking not only at the spoken words, but also the dresses worn, the camera angles, and the princesses’ tone of voice when speaking to other characters to assess how Disney’s construction of gender has changed over time.

7. Semiotic Analysis

Semiotic analysis takes multimodal analysis to the next step by providing the specific methods for the analysis of multimodal texts.

Seminal scholars Kress and van Leeuwen (2006) have created a significant repertoire of texts demonstrating how semiotics shape meaning. In their works, they present deconstructions of various modes of address:

- Visual: How images, signs, and symbols create meaning in social contexts. For example, in our modern world, a red octagon has a specific social meaning: stop!

- Textual: How words shape meaning, such as through a sentiment analysis as discussed earlier.

- Motive: How movement can create a sense of pace, distance, the movement of time, and so forth, which shapes meaning.

- Aural: How sounds shape meaning. For example, the words spoken are not the only way we interpret a speech, but also how they’re spoken (shakily, confidently, assertively, etc.)

Example of Semiotic Analysis

A communications studies scholar examines the body language of leaders during meetings at an international political event, using it to explore how the leaders subtly send messages about who they are allied with, where they view themselves in geopolitical terms, and their attitudes toward the event overall.

8. Latent Content Analysis

This involves the interpretation of the underlying, inferred meanings of the words or visuals. The focus here is on what is being implied by the content rather than just what is explicitly said.

For example, in the context of the same newspaper articles, a latent content analysis might examine the way the event is framed, the language or rhetoric used, the themes or narratives that are implied, or the attitudes and ideologies that are expressed or endorsed, either overtly or covertly .

Returning to the work of Foucault, he demonstrated how silence also constructs meaning. The question emerges: what is left unsaid in the content, and how does this shape our understanding of the biases and assumptions of the author?

Example of Latent Content Analysis

A sociologist studying gender roles in films watches the top 10 movies from last year and doesn’t just count instances of words – rather, they analyze the underlying, implicit messages about gender roles. This could include exploring how female characters are portrayed (do they tend to be passive and in need of rescue, or are they active, independent and resourceful?) and how male characters are portrayed (emotional or unemotional?) What kind of occupations do characters of each gender typically have?

9. Manifest Content Analysis

A manifest content analysis is the counterpoint to latent content analysis. It involves a direct and surface-level reading of the visible aspects of the content.

It concerns itself primarily with what is visible, obvious and countable. This approach asserts that we should not read too deeply into anything beyond what is manifest (i.e. present), because the deeper we try to read into the missing or latent elements, the more we stray into the real of guessing and assuming.

Scholars will often do both latent and manifest content analyses side-by-side, exploring how each type of analysis might reveal different interpretations or insights.

Example of Manifest Content Analysis

A researcher is interested in studying bias in media coverage of a particular political event. They might conduct a conceptual analysis where the concept is the tone of language used – positive, neutral, or negative. They would examine a number of articles from different newspapers, tallying up instances of positive, negative, or neutral language to see if there is a bias towards positivity or negativity in coverage of the event.

10. Longitudinal Content Analysis

A longitudinal content analysis analyzes trends in content over a long period of time.

Earlier, I explored the idea in discourse analysis that different eras have different ideas about terms and concepts (consider, for example, evolving ideas of gender and race). A longitudinal analysis would be very useful here. It would involve collecting cross-sectional moments in time , at varying points in time, which would then be compared and contrasted for the representation of varying concepts and terms.

Example of Longitudinal Content Analsis

A scholar might look at newspaper reports on texts from each decade for 100 years, examining environmental terms (‘global warming’, ‘climate change’, ‘recycling’) to identify when and how environmental concepts entered public discourse.

For other Examples of Analysis, See Here

Content analysis is a form of empirical research that uses texts rather than interviews or naturalistic observation to gather data that can then be analyzed. There are a range of methods and approaches to the analysis of content, but their unifying feature is that they involve close readings of texts to identify concepts and themes that might be revealing of core or underlying messages within the content.

The above examples are not mutually exclusive types, but rather different approaches that researchers can use based on their specific goals and the nature of the data they are working with.

Foucault, M. (1988). Madness and civilization: A history of insanity in the age of reason . London: Vintage.

Johnstone, B. (2017). Discourse analysis . London: John Wiley & Sons.

Kosterec, M. (2016). Methods of conceptual analysis. Filozofia , 71 (3).

Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2006). The grammar of visual design . London and New York: Routledge.

Prasad, B. D. (2008). Content analysis: A method of Social Science Research . In D.K. Lal Das (ed) Research Methods for Social Work, (pp.174-193). New Delhi: Rawat Publications.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Data & Finance for Work & Life

Qualitative Content Analysis: a Simple Guide with Examples

Content analysis is a type of qualitative research (as opposed to quantitative research) that focuses on analyzing content in various mediums, the most common of which is written words in documents.

It’s a very common technique used in academia, especially for students working on theses and dissertations, but here we’re going to talk about how companies can use qualitative content analysis to improve their processes and increase revenue.

Whether you’re new to content analysis or a seasoned professor, this article provides all you need to know about how data analysts use content analysis to improve their business. It will also help you understand the relationship between content analysis and natural language processing — what some even call natural language content analysis.

Don’t forget, you can get the free Intro to Data Analysis eBook , which will ensure you build the right practical skills for success in your analytical endeavors.

What is qualitative content analysis, and what is it used for?

Any content analysis definition must consist of at least these three things: qualitative language , themes , and quantification .

In short, content analysis is the process of examining preselected words in video, audio, or written mediums and their context to identify themes, then quantifying them for statistical analysis in order to draw conclusions. More simply, it’s counting how often you see two words close to each other.

For example, let’s say I place in front of you an audio bit, a old video with a static image, and a document with lots of text but no titles or descriptions. At the start, you would have no idea what any of it was about.

Let’s say you transpose the video and audio recordings on paper. Then you use a counting software to count the top ten most used words, excluding prepositions (of, over, to, by) and articles (the, a), conjunctions (and, but, or) and other common words like “very.”

Your results are that the top 5 words are “candy,” “snow,” “cold,” and “sled.” These 5 words appear at least 25 times each, and the next highest word appears only 4 times. You also find that the words “snow” and “sled” appear adjacent to each other 95% of the time that “snow” appears.

Well, now you have performed a very elementary qualitative content analysis .

This means that you’re probably dealing with a text in which snow sleds are important. Snow sleds, thus, become a theme in these documents, which goes to the heart of qualitative content analysis.

The goal of qualitative content analysis is to organize text into a series of themes . This is opposed to quantitative content analysis, which aims to organize the text into categories .

Types of qualitative content analysis

If you’ve heard about content analysis, it was most likely in an academic setting. The term itself is common among PhD students and Masters students writing their dissertations and theses. In that context, the most common type of content analysis is document analysis.

There are many types of content analysis , including:

- Short- and long-form survey questions

- Focus group transcripts

- Interview transcripts

- Legislature

- Public records

- Comments sections

- Messaging platforms

This list gives you an idea for the possibilities and industries in which qualitative content analysis can be applied.

For example, marketing departments or public relations groups in major corporations might collect survey, focus groups, and interviews, then hand off the information to a data analyst who performs the content analysis.

A political analysis institution or Think Tank might look at legislature over time to identify potential emerging themes based on their slow introduction into policy margins. Perhaps it’s possible to identify certain beliefs in the senate and house of representatives before they enter the public discourse.

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) might perform an analysis on public records to see how to better serve their constituents. If they have access to public records, it would be possible to identify citizen characteristics that align with their goal.

Analysis logic: inductive vs deductive

There are two types of logic we can apply to qualitative content analysis: inductive and deductive. Inductive content analysis is more of an exploratory approach. We don’t know what patterns or ideas we’ll discover, so we go in with an open mind.

On the other hand, deductive content analysis involves starting with an idea and identifying how it appears in the text. For example, we may approach legislation on wildlife by looking for rules on hunting. Perhaps we think hunting with a knife is too dangerous, and we want to identify trends in the text.

Neither one is better per se, and they each have carry value in different contexts. For example, inductive content analysis is advantageous in situations where we want to identify author intent. Going in with a hypothesis can bias the way we look at the data, so the inductive method is better

Deductive content analysis is better when we want to target a term. For example, if we want to see how important knife hunting is in the legislation, we’re doing deductive content analysis.

Measurements: idea coding vs word frequency

Two main methodologies exist for analyzing the text itself: coding and word frequency. Idea coding is the manual process of reading through a text and “coding” ideas in a column on the right. The reason we call this coding is because we take ideas and themes expressed in many words, and turn them into one common phrase. This allows researchers to better understand how those ideas evolve. We will look at how to do this in word below.

In short, coding in the context qualitative content analysis follows 2 steps:

- Reading through the text one time

- Adding 2-5 word summaries each time a significant theme or idea appears

Word frequency is simply counting the number of times a word appears in a text, as well as its proximity to other words. In our “snow sled” example above, we counted the number of times a word appeared, as well as how often it appeared next to other words. There’s are online tool for this we’ll look at below.

In short, word frequency in the context of content analysis follows 2 steps:

- Decide whether you want to find a word, or just look at the most common words

- Use word’s Replace function for the first, or an online tool such as Text Analyzer for the second (we’ll look at these in more detail below).

Many data scientists consider coding as the only qualitative content analysis, since word frequency turns to counting the number of times a word appears, making is quantitative.

While there is merit to this claim, I personally do not consider word frequency a part of quantitative content analysis. The fact that we count the frequency of a word does not mean we can draw direct conclusions from it. In fact, without a researcher to provide context on the number of time a word appears, word frequency is useless. True quantitative research carries conclusive value on its own.

Measurements AND analysis logic

There are four ways to approach qualitative content analysis given our two measurement types and inductive/deductive logical approaches. You could do inductive coding, inductive word frequency, deductive coding, and deductive word frequency.

The two best are inductive coding and deductive word frequency. If you would like to discover a document, trying to search for specific words will not inform you about its contents, so inductive word frequency is un-insightful.

Likewise, if you’re looking for the presence of a specific idea, you do not want to go through the whole document to code just to find it, so deductive coding is not insightful. Here’s simple matrix to illustrate:

Qualitative content analysis example

We looked at a small example above, but let’s play out all of the above information in a real world example. I will post the link to the text source at the bottom of the article, but don’t look at it yet . Let’s jump in with a discovery mentality , meaning let’s use an inductive approach and code our way through each paragraph.

Qualitative Content Analysis Example Download

*Click the “1” superscript to the right for a link to the source text. 1

How to do qualitative content analysis

We could use word frequency analysis to find out which are the most common x% of words in the text (deductive word frequency), but this takes some time because we need to build a formula that excludes words that are common but that don’t have any value (a, the, but, and, etc).

As a shortcut, you can use online tools such as Text Analyzer and WordCounter , which will give you breakdowns by phrase length (6 words, 5 words, 4 words, etc), without excluding common terms. Here are a few insightful example using our text with 7 words:

Perhaps more insightfully, here is a list of 5 word combinations, which are much more common:

The downside to these tools is that you cannot find 2- and 1-word strings without excluding common words. This is a limitation, but it’s unlikely that the work required to get there is worth the value it brings.

OK. Now that we’ve seen how to go about coding our text into quantifiable data, let’s look at the deductive approach and try to figure out if the text contains a single word we’re looking for. (This is my favorite.)

Deductive word frequency

We know the text now because we’ve already looked through it. It’s about the process of becoming literate, namely, the elements that impact our ability to learn to read. But we only looked at the first four sections of the article, so there’s more to explore.

Let’s say we want to know how a household situation might impact a student’s ability to read . Instead of coding the entire article, we can simply look for this term and it’s synonyms. The process for deductive word frequency is the following:

- Identify your term

- Think of all the possible synonyms

- Use the word find function to see how many times they appear

- If you suspect that this word often comes in connection with others, try searching for both of them

In my example, the process would be:

- Parents, parent, home, house, household situation, household influence, parental, parental situation, at home, home situation

- Go to “Edit>Find>Replace…” This will enable you to locate the number of instances in which your word or combinations appear. We use the Replace window instead of the simply Find bar because it allows us to visualize the information.

- Accounted for in possible synonyms

The results: 0! None of these words appeared in the text, so we can conclude that this text has nothing to do with a child’s home life and its impact on his/her ability to learn to read. Here’s a picture:

Don’t Be Afraid of Content Analysis

Content analysis can be intimidating because it uses data analysis to quantify words. This article provides a starting point for your analysis, but to ensure you get 90% reliability in word coding, sign up to receive our eBook Beginner Content Analysis . I went from philosophy student to a data-heavy finance career, and I created it to cater to research and dissertation use cases.

Content analysis vs natural language processing

While similar, content analysis, even the deductive word frequency approach, and natural language processing (NLP) are not the same. The relationship is hierarchical. Natural language processing is a field of linguistics and data science that’s concerned with understanding the meaning behind language.

On the other hand, content analysis is a branch of natural language processing that focuses on the methodologies we discussed above: discovery-style coding (sometimes called “tokenization”) and word frequency (sometimes called the “bag of words” technique)

For example, we would use natural language processing to quantify huge amounts of linguistic information, turn it into row-and-column data, and run tests on it. NLP is incredibly complex in the details, which is why it’s nearly impossible to provide a synopsis or example technique here (we’ll provide them in coursework on AnalystAnswers.com ). However, content analysis only focuses on a few manual techniques.

Content analysis in marketing

Content analysis in marketing is the use of content analysis to improve marketing reach and conversions. has grown in importance over the past ten years. As digital platforms become more central to our understanding and interaction with others, we use them more.

We write out ideas, small texts. We post our thoughts on Facebook and Twitter, and we write blog posts like this one. But we also post videos on youtube and express ourselves in podcasts.

All of these mediums contain valuable information about who we are and what we might want to buy . A good marketer aims to leverage this information in three ways:

- Collect the data

- Analyze the data

- Modify his/her marketing messaging to better serve the consumer

- Pretend, with bots or employees, to be a consumer and craft messages that influence potential buyers

The challenge for marketers doing this is getting the rights to access this data. Indeed, data privacy laws have gone into play in the European Union (General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR) as well as in Brazil (General Data Protection Law, or GDPL).

Content analysis vs narrative analysis

Content analysis is concerned with themes and ideas, whereas narrative analysis is concerned with the stories people express about themselves or others. Narrative analysis uses the same tools as content analysis, namely coding (or tokenization) and word frequency, but its focus is on narrative relationship rather than themes. This is easier to understand with an example. Let’s look at how we might code the following paragraph from the two perspectives:

I do not like green eggs and ham. I do not like them, Sam-I-Am. I do not like them here or there. I do not like them anywhere!

Content analysis : the ideas expressed include green eggs and ham. the narrator does not like them

Narrative analysis : the narrator speaks from first person. He has a relationship with Sam-I-Am. He orients himself with regards to time and space. he does not like green eggs and ham, and may be willing to act on that feeling.

Content analysis vs document analysis

Content analysis and document analysis are very similar, which explains why many people use them interchangeably. The core difference is that content analysis examines all mediums in which words appear , whereas document analysis only examines written documents .

For example, if I want to carry out content analysis on a master’s thesis in education, I would consult documents, videos, and audio files. I may transcribe the video and audio files into a document, but I wouldn’t exclude them form the beginning.

On the other hand, if I want to carry out document analysis on a master’s thesis, I would only use documents, excluding the other mediums from the start. The methodology is the same, but the scope is different. This dichotomy also explains why most academic researchers performing qualitative content analysis refer to the process as “document analysis.” They rarely look at other mediums.

Content Gap Analysis

Content gap analysis is a term common in the field of content marketing, but it applies to the analytical fields as well. In a sentence, content gap analysis is the process of examining a document or text and identifying the missing pieces, or “gap,” that it needs to be completed.

As you can imagine, a content marketer uses gap analysis to determine how to improve blog content. An analyst uses it for other reasons. For example, he/she may have a standard for documents that merit analysis. If a document does not meet the criteria, it must be rejected until it’s improved.

The key message here is that content gap analysis is not content analysis. It’s a way of measuring the distance an underperforming document is from an acceptable document. It is sometimes, but not always, used in a qualitative content analysis context.

- Link to Source Text [ ↩ ]

About the Author

Noah is the founder & Editor-in-Chief at AnalystAnswers. He is a transatlantic professional and entrepreneur with 5+ years of corporate finance and data analytics experience, as well as 3+ years in consumer financial products and business software. He started AnalystAnswers to provide aspiring professionals with accessible explanations of otherwise dense finance and data concepts. Noah believes everyone can benefit from an analytical mindset in growing digital world. When he's not busy at work, Noah likes to explore new European cities, exercise, and spend time with friends and family.

File available immediately.

Notice: JavaScript is required for this content.

- Memberships

Content Analysis explained plus example

Content Analysis: this article provides a practical explanation of the term content analysis in the context of research skills. The article begins with a general definition and explanation, followed by a step-by-step plan for performing this type of analysis, including an example at each step. You will also find an overview of the benefits and drawbacks of applying such an analysis in a study. Enjoy reading!

What is a content analysis? A brief explanation

Content analysis is a research method that can identify patterns in recorded communications.

By systematically collecting data from different types of texts, such as written documents, speeches, web content or visual media, researchers can then discover valuable information about the goals , messages and effects of communication.

In this type of analysis, words, themes and concepts in the texts are categorized or “coded” , allowing for both quantitative and qualitative analyses.

Quantitative analysis focuses on counting and precisely measuring events, while qualitative analysis aims to interpret and understand the meaning and semantic relationships of words and concepts.

A Content Analysis example

An example. In a political campaign, content analysis can help researchers understand the importance of employment issues.

By analyzing political leaders’ campaign speeches, they can quantify the frequency of terms such as unemployment, jobs and employment and analyze them statistically for differences over time or between candidates.

In addition, they can also take a qualitative approach, examining the word unemployment in speeches, identifying related words or phrases and analyzing the meanings of these relationships. The aim is then to gain a deeper understanding of the intentions and target groups of different campaigns.

In which fields are content analyzes used?

Content analytics is applied in a variety of fields , including marketing , media studies, anthropology, cognitive science, psychology, and social sciences.

The goals of this type of analysis range from identifying correlations and patterns in communication to understanding intentions and analyzing the consequences of communication.

Research Methods For Business Students Course A-Z guide to writing a rockstar Research Paper with a bulletproof Research Methodology! More information

Step-by-step plan for performing a content analysis

Below you will find the steps that are followed when performing a content analysis.

Please note that the approach to the analysis may differ per situation. The steps you read about below are general steps.

Step 1: Select the content you want to analyze

Start by choosing specific texts or material to examine in the content analysis. This may include sources such as news articles, social media posts, interviews or documents. When analyzing social media posts, make sure you use social media analytics tools for gathering insights and measuring the performance of your content.

When analyzing social media posts, make sure you use social media analytics tools for gathering insights and measuring the performance of your content.

Example: Select a collection of 100 newspaper articles from reputable sources that deal with climate change.

Step 2: Define the units and categories of analysis

Determine the specific units within the content you want to analyze and create categories to classify them. Units can be individual words, sentences, paragraphs, or even entire sections.

Example: Define a unit as a single sentence in the newspaper articles and create categories such as “causes of climate change” , “impacts on the environment” and “policy recommendations” .

Step 3: Develop a set of coding rules

Create a clear and consistent set of guidelines for assigning codes to the units based on the established categories. These rules ensure consistent and reliable coding during analysis.

Example: Code a sentence discussing the role of greenhouse gasses as “GG” and a sentence pointing to renewable energy solutions as “RES” .

Step 4: Code the text according to the rules

Systematically apply the coding rules to the content and assign the correct codes to each unit.

Please read and interpret the content carefully to determine the most accurate code based on established guidelines.

Example: Read each sentence in the newspaper articles and assign the relevant code (GG or RES) to indicate whether the sentence discusses greenhouse gases or renewable energy solutions.

Step 5: Analyze the results from the Content Analysis and draw conclusions

Once coding is complete, analyze the encoded data to identify patterns, frequencies, and relationships between categories.

Calculate percentages or frequencies to quantify the occurrences of specific codes. Interpret the results to draw meaningful conclusions about the content.

Example: Calculate the percentage of sentences related to “causes of climate change” versus “policy recommendations” to understand the focus of the articles.

Analyze how often the code GG occurs compared to the code RES to assess the emphasis on renewable energy solutions.

Sampling as a part of the content analysis

Sampling is an important aspect of content analysis. Sampling determines which texts are included in the analysis.

There are several sampling methods that researchers can use:

Random sampling

In this method, texts are randomly selected from the population. Random sampling ensures that the selected texts are representative of the larger population.

It reduces the risk of bias and allows generalization of the findings to a broader context.

Example: In a content analysis of customer reviews on an e-commerce platform, random sampling can be used to obtain a random selection of reviews from the full pool of available reviews.

Purposive sampling

In purposive sampling, texts are selected based on specific criteria or characteristics relevant to the research purposes.

Researchers deliberately select texts that offer valuable insights or illustrate certain themes or perspectives.

Example: In an analysis of political speeches, purposive sampling can be used to select speeches by major political figures or to choose speeches that address specific policy issues relevant to the study.

Sampling units

Sampling units refer to the elements within the selected texts that will be analyzed. Researchers must determine the appropriate size and scope of analysis by defining the sampling units.

These units can vary depending on the research question, such as individual words, sentences, paragraphs or entire documents.

Example: In a content analysis of online news articles, the sampling units might be individual paragraphs within the articles. Researchers may choose to analyze the statements in these paragraphs.

Benefits of content analysis in research

The benefits are:

Objectivity

Content analysis uses a systematic and structured approach, making it possible to obtain objective and reproducible results . It provides a quantitative basis for analysis and interpretation.

Large amount of data

Content analysis enables researchers to efficiently analyze large amounts of texts. This allows them to spot patterns and trends that would otherwise be difficult to identify.

Flexibility

Content analysis can be applied to different types of texts, such as written, oral or visual sources. This makes it a versatile method that can be adapted to various research questions and disciplines.

Wide applicability

Content analysis is used in various fields such as marketing, media research, sociology, psychology and more. It offers a valuable tool for gaining insight into communication processes and their effects.

Drawbacks of content analysis in research

The use of content analysis also has some drawbacks. Read them below.

Limited to selected content

These types of analysis relies on the availability of recorded communications, such as written documents, interviews, social media posts, etc. It may limit interpretation to what is actually captured and may miss important contextual information.

Subjectivity of the Content Analysis

Because content analysis requires the interpretation of the researcher in coding and analyzing the data, there can be a degree of subjectivity. The researcher’s personal biases or interpretations may affect the results.

Time intensive

These types of analysis can be a time-consuming method, especially when analyzing large amounts of texts. It requires patience and accuracy in coding and analyzing the data.

Possible coding issues

Now it’s your turn

What do you think? Do you recognize the explanation about content analysis? Have you ever used content analysis for research? What challenges did you face while performing this analysis? How important do you think it is to have a representative sample when conducting a content analysis? What other things do you think researchers can use to ensure the reliability of the content analysis? Do you have tips or comments?

Share your experience and knowledge in the comments box below.

More information

- Barick, R. (2021). Research Methods For Business Students . Retrieved 02/16/2024 from Udemy.

- Drisko, J. W., & Maschi, T. (2016). Content analysis . Pocket Guide to Social Work .

- Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology . Sage publications .

- Stemler, S. (2000). An overview of content analysis . Practical assessment, research, and evaluation, 7(1), 17.

- Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic content analysis (Vol. 49). Sage.

How to cite this article: Janse, B. (2023). Content Analysis . Retrieved [insert date] from Toolshero: https://www.toolshero.com/research/content-analysis/

Original publication date: 11/14/2023 | Last update: 02/09/2024

Add a link to this page on your website: <a href=” https://www.toolshero.com/research/content-analysis/”> Toolshero: Content Analysis</a>

Did you find this article interesting?