- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Media Literacy, Essay Example

Pages: 3

Words: 953

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Introduction

Media literacy is a complex issue that requires further investigation and evaluation in the modern era. It is important to identify the resources that are required to effectively adapt to a media-filled culture, whereby there are significant opportunities to achieve growth and change in the context of new ideas for growth and maturity for the average viewer/reader. It is known that “Interactivity as a core factor in multimedia is in some ways closely related to performance and can enable the viewer/reader/user to participate directly in the construction of meaning” (Daley 36). This quote is inspiring because it requires individuals to truly connect with the media on several levels that will have an instrumental impact on personal growth and the ability to be informative on many levels. The media saturates society through Facebook, Twitter, 24-hour news channels, and traditional forms such as magazines newspapers. Therefore, it is essential to identify a personal strategy that enables the reader/viewer to decipher through the hundreds if not thousands of messages that the media delivers on a daily basis so that individuals are better prepared to manage their own degree of literacy effectively.

For a website such as CNN.com, there appears to be a clash of sorts between that which is truly newsworthy and important to the lives of many people and that which might be deemed sensationalism to grab readers’ attention and an increased number of views, as well as ratings. This is a complex situation because the network and its accompanying website strive to remain competitive with the needs of its readers/viewers, while also requiring other factors to be considered that might improve their ability to decipher through the messages and to identify those which are most meaningful and appropriate within their lives. The homepage of the CNN website typically has an emerging or news-worthy story that is designed to grab the reader’s attention and to facilitate a response from the reader, perhaps a visceral reaction. This is part of the appeal of online news, as it attempts to draw viewers’ attention to what the website deems as newsworthy and of value to the reader. Although this is not always the case, the website achieves it key objective by attracting the reader enough to at least read the headlines and perhaps read some of the other stories that are listed on the homepage. Nonetheless, it is likely that many viewers will barely scratch the surface of an article because they lose interest or do not understand the backstory regarding the topic to keep reading. This is a key component of the high level of media illiteracy that exists in the modern era and that supports the development of new strategies to encourage readers to become less media illiterate and to improve their literacy regarding issues that generate much attention and focus from the masses.

There are critical factors associated with media literacy that require further consideration and evaluation, such as the tools that support the growth of individuals as they learn how to weave through the messages that they receive online, on television, and in print. Media literacy is more than merely reading stories, as it is about taking these stories in, forming opinions, developing a passion for a topic or an idea, and forming a bond with others who might share or contrast with these views (Media Literacy Project). In this context, it is important to identify the resources that are required to develop a strategy that supports media literacy on a much larger level that will impact society and its people as they develop a higher level of intelligence and/or acceptance of the ideas set forth within a given story or headline.

Overcoming media illiteracy requires the development of new strategies for individuals to take ideas that they read on a website such as CNN.com and to make them their own and perhaps apply them to their own lives in one or more ways. This is how media literacy works, as it enables individuals to transition from simply reading news stories online towards adapting them to their own lives in one way or another. This process engages readers and enables them to recognize the importance of improving their own level of literacy through these opportunities. It is imperative to recognize the value of media literacy as it applies to the human condition in the modern era, particularly as individuals have become increasingly dependent on the news as a part of their daily routines. This process supports and engages readers/viewers in the context of many different situations that enable them to cross over into a world where they have a better understanding of the media and how it impacts their lives in different ways.

Media literacy is a complex and ongoing phenomenon that has a unique impact on the lives of individuals. Many websites influence how people interpret the news, such as CNN.com, as they only tend to scratch the surface of news without any real opportunity to formulate opinions regarding the topics that are within. Therefore, it is important to identify some of the issues that are common in these stories and to recognize the importance of developing new approaches to stories that will have a positive impact on the response from readers/viewers. Media literacy is an ongoing process that requires the full attention and focus of individuals in order to accomplish the desired goals and objectives, while also considering the value of developing new perspectives that will encourage readers to take greater steps towards formulating their own opinions regarding stories and topics that may impact their own lives on many levels.

Works Cited

CNN.com. 11 May 2014: http://www.cnn.com/

Daley, Elizabeth. “Expanding the concept of literacy.” Educause, 11 May 2014: https://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/erm0322.pdf

Media Literacy Project. “What is media literacy?” 11 May 2014: http://medialiteracyproject.org/learn/media-literacy

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Compression of Morbidity, Essay Example

Analysis of the King Lear, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

For enquiries call:

+1-469-442-0620

Media and Information Literacy: Need, Importance, Example

Home Blog Learning Media and Information Literacy: Need, Importance, Example

The problem of educating consumers to evaluate, examine, and make use of the very diverse spectrum of media accessible in the 21st century has made media and information literacy an ambitious objective. Users now need to gain media literacy not just concerning conventional media and visual representation but also about the abundance of new technologies accessible and the creation of apps enabling completely novel methods of information transmission.

The issue of who will educate our children has not yet been resolved. Is it not reasonable, in general, that media and information literacy become pillars of the educational curriculum since schools are the places where students learn critical thinking, analysis, and decision-making? With the best Software Developer training courses, you can learn diverse skills to advance your career.

What Is Media Literacy?

Media literacy is a broad range of skills that enable individuals to consume, analyze, modify, and even create many media types. In essence, media literacy may assist someone in critically thinking about what they read, see, or hear in the media. In this context, the word "media" refers to a wide range of media, including the internet, movies, music, radio, television, video games, and publications.

To be media literate, one must be capable of decoding media messages (understanding the message and the medium), assessing how the messages affect one's emotions, ideas, and behavior, and intelligently and responsibly producing media. In addition, pupils may benefit greatly from mastering media information literacy .

What Is Media and Information Literacy?

Media and Information Literacy (MIL) strives to empower people to engage in an inquiry process and critically think about the media and the content they receive. According to the UNESCO meaning of media and information literacy , the goal is to empower people to take active roles in their communities and make ethical decisions. The modern media environment makes it extremely important to have media and informational competencies. Whether the news comes from reliable sources or not, it is important to consider who and what to believe critically.

Why Is Media and Information Literacy Important?

Critical thinking is vital for citizens, particularly young learners who need to solve issues, gather information, develop views, assess sources, and more. MIL is a vital skill, especially with the abundance of data and accurate and false information accessible online. A person who knows the meaning of media literacy skills will be able to ask inquiries and look for solutions to the internet debris because of the pace of information delivery.

The instructors are given better information to empower the next generation of people throughout the teaching and learning process. Media and information literacy's meaning is to impart critical knowledge about the roles played by media and information channels in democracies, practical awareness of the circumstances, and the fundamental skills required to assess the effectiveness of media and information providers in light of their roles as expected.

How Does Media and Information Literacy Work?

The foundation for learning media and the function of media in our society is through media and information literacy. MIL also imparts some of the fundamental abilities required for critical thinking, analysis, self-expression, and creativity, all of which are needed for members of a democratic society. From printing to radio, from video to the internet, citizens may analyze media and information in a variety of mediums.

What Are Some Dimensions of Media and Information Literacy?

The term "media and information literacy" (MIL) refers to three often recognized dimensions:

- Information literacy

- Media literacy

- ICT/digital literacy.

As UNESCO emphasizes, MIL brings together stakeholders, such as people, communities, and countries, to contribute to the information society. In addition to serving as an umbrella, MIL also contains various competencies that must be employed properly to critically assess each of its many components.

Media Literacy Examples

Some media literacy examples are:

1. Television

For more than 50 years, families have enjoyed watching television. Today, viewers may access a movie or television show anytime they want, thanks to the pay-per-view or no-cost on-demand options offered by many cable or satellite systems.

2. Blog Posts

Anyone can instantly share information through the internet, which is a constantly evolving platform for quick, decentralized communication. The internet provides venues to educate, enlighten, inspire, and connect, as well as to persuade and control, including news sources, social media, blogs, podcasts, and smartphone applications.

3. YouTube

The YouTube platform engages audiences throughout the globe. With more individuals accessing the internet since its 2005 launch, YouTube's popularity has risen significantly.

4. social media

Social media is one of the most recent platforms that media strategists might use. Social media ads have become commonplace in less than ten years.

5. News Papers

This is the first kind of media that includes all printed materials. Reputable print media sources that are professionally produced and created to satisfy the demands of certain audiences.

6. Magazines

Since the middle class didn't start reading magazines until the 19th century, publishers had to start selling advertising space to cover the high cost of printing and increase circulation.

7. Video games

Video games have been around since the early 1980s, and kids have only become more and more fond of them. Modern video games are engaging and thrilling, and the lifelike images and audio give players the impression that they are really in the scenario.

8. News Websites

The internet is full of opinions from regular people who post with various intentions, which occasionally makes it difficult to distinguish fact from fiction. However, some websites host peer-reviewed information from reliable sources that are essentially digital versions of traditional print sources.

9. Podcasts

An audio file that your viewers may listen to whenever they want is all that makes up a podcast. As pre-recorded content, podcasts are not ideal for situations requiring audience participation.

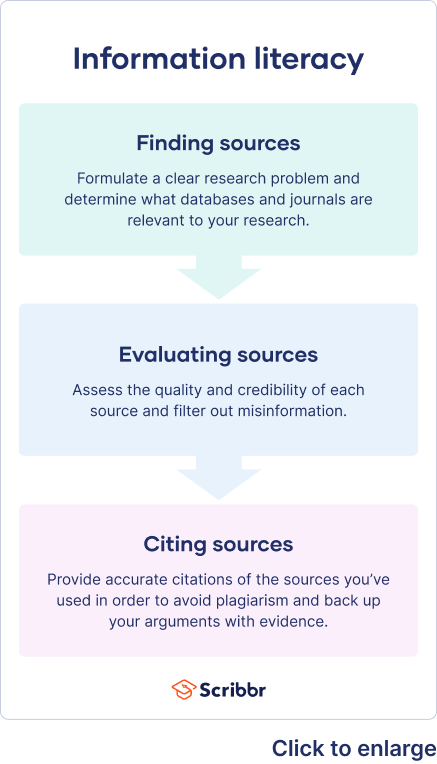

What Is Information Literacy?

The term "information literacy" describes certain abilities required to locate, evaluate, and effectively utilize information. Information literacy refers to a person's understanding of their interaction with the digital world and their interpretation of the information they discover. It also entails the need to utilize such knowledge morally. Study techniques and academic writing, critical analysis, evaluation, and evaluation-based thinking are some traits of information literacy.

Information Literacy Examples

1. Communication

Transfer of information or exchange has done orally, in writing, or by any other means. The effective communication or exchange of ideas and emotions

- Verbal: This includes face-to-face communication, telephone communication, and other media

- Non-verbal: This includes things like our posture, body language, gestures, how we dress or behave, and even our fragrance.

- Written: Writing comprises letters, emails, social media posts, books, periodicals, the internet, and other forms of written communication.

- Visual: Graphs and charts, maps, logos, and other visuals may all be used to convey information.

2. Computer Technology

The term "computer skills" describes the capacity to efficiently operate a computer and associated technology, and it includes both hardware and software expertise. You can also opt for a Full-Stack Developer course with placement to learn more about front-end and back-end web development and start your career as a full-stack developer.

3. Critical Thinking

The process of learning critical thinking techniques improves one's capacity to access information and related concepts. Making a rational decision based on an objective study of information and research results is referred to as critical thinking.

4. Research

The capacity to identify, acquire, collect, assess, use and present knowledge on a certain issue is referred to as having research abilities. These abilities include conducting research, conducting critical analysis, and formulating theories or solutions to specific problems.

Importance of Media and Information Literacy

People in the frame will outright deny facts if they believe that the information contradicts their beliefs, regardless of whether those beliefs are related to politics, the effectiveness of vaccines, the presence of conditions like global warming, or even the nature of reality as we currently understand it. The fact that we can often verify the integrity and correctness of the information serves to make the entire scenario more annoying and terrifying.

But other individuals don't care because they purposefully ignore or justify certain facts since they don't agree with them. And because the internet and allied media can mislead sensitive individuals by spreading these harmful notions.

It's critical to have the ability to sort through the abundance of information available, whether we're discussing the personal lives of individuals or a corporation's marketing plan. Media and information literacy skills are essential for personal and professional aspects of life.

Need for Media and Information Literacy in Today's World

Individuals in 2020 will have an overwhelming variety of media sources. The 24-hour news cycle, television, videos, podcasts, blogs, specialist websites, text messages, blogs, and vlogs are now available in addition to the print and radio media that are still in use.

For better or worse, anybody can make content thanks to technological advancements.

Regrettably, not everyone considers ethics or a truthful way. Even if some opinions are wholly erroneous and inaccurate, when individuals band together in an organized manner, it often gives the impression that they could have a point. As a result, we are constantly surrounded with genuine and deceptive information due to today's technological advancements. Thus, media and information literacy are more important than ever in the modern world.

Difference Between Media, Technology, and Information Literacy

Similar to digital citizenship, several definitions and terminology are used to define media and information literacy . Whether we refer to it as information literacy, internet literacy, digital media literacy , or any other term, the key premise is that literacy includes the capacity to interact intelligently with media and information sources. You can check out KnowledgeHut Software Developer training to develop a thorough understanding of the in-demand digital technologies to launch your career in software development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Individuals who are proficient in media literacy are equipped with the ability to first think critically about media. It also fosters other abilities like creativity, teamwork, and communication and improves digital literacy skills by connecting with media, information, and technology.

Media and information literacy includes all sorts of information resources, including oral, print, and digital. In today's increasingly digital, linked, and global society, media, and information literacy is a fundamental human right that fosters greater social inclusion.

The five elements of information literacy include identifying, finding, evaluating, applying, and acknowledging sources of information.

Information and media literacy skills are the combination of knowledge, attitudes, and abilities necessary to understand when and what information is required, where to get it, how to organize it once obtained, and how to utilize it ethically.

KnowledgeHut .

KnowledgeHut is an outcome-focused global ed-tech company. We help organizations and professionals unlock excellence through skills development. We offer training solutions under the people and process, data science, full-stack development, cybersecurity, future technologies and digital transformation verticals.

Avail your free 1:1 mentorship session.

Something went wrong

Essay on Media And Information Literacy

Students are often asked to write an essay on Media And Information Literacy in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Media And Information Literacy

Understanding media and information literacy.

Media and Information Literacy (MIL) is knowing how to smartly handle and use information from different sources like TV, internet, and books. It’s like learning to swim in a sea of endless news, pictures, and videos.

The Importance of MIL

It’s crucial because it helps you tell what’s true from what’s not. With MIL, you can make better choices about what to read, watch, and share. It’s like having a map in the world of media.

Learning to Check Facts

A big part of MIL is learning to check if something is correct. Before believing a story, see if trusted places also report it. It’s like double-checking your answers in a test.

Using Media Wisely

MIL teaches you to use media in a good way. It means not spending too much time on screens and knowing that not everything online is good for you. It’s about making smart media choices.

Sharing Responsibly

With MIL, you learn to think before you share something online. Ask yourself if it’s helpful, true, and kind. It’s about being a good friend in the digital world.

250 Words Essay on Media And Information Literacy

Media and Information Literacy, or MIL, is knowing how to smartly use the internet, newspapers, books, and other ways we get information. It’s like learning how to fish in a huge sea of news and facts. With MIL, you can tell which fish are good to eat and which might make you sick.

Why MIL is Important

Today, we get bombarded with tons of messages and pictures through our phones, TVs, and computers. Some of these are true, but others are not. MIL helps you sort out the truth from the lies. It’s like having a special tool that helps you know which friend is telling the truth and which is just making up stories.

One part of MIL is checking if something is true or not. Before you believe a story, ask yourself: Who wrote this? Why did they write it? Is there proof? It’s like being a detective, looking for clues to solve a mystery.

MIL also teaches you to use media in a good way. It means spending the right amount of time watching TV or playing games and also using the internet to learn new things. Think of it as a diet for your brain—you need a mix of fun, learning, and rest.

Sharing the Right Information

Lastly, MIL helps you share information the right way. Before you send a message or a picture to others, think: Is it kind? Is it necessary? Is it true? By doing this, you can be a hero who helps stop lies and spread kindness.

500 Words Essay on Media And Information Literacy

Media and information literacy is like learning how to read a map in a world full of signs and messages. It teaches us how to understand and use the information we get from television, the internet, books, and other sources. Just like knowing how to read and write helps us in school, media literacy helps us make sense of the news, advertisements, and even social media posts we see every day.

The Need for Media Literacy

We live in a time when we are surrounded by a sea of information. From the moment we wake up to the time we go to bed, we are bombarded with messages from our phones, TVs, and computers. With so much information coming at us, it’s important to know what is true and what isn’t. This is where media literacy comes in. It helps us tell the difference between facts and opinions, and it teaches us to ask questions about what we see and hear.

Spotting Fake News

One of the biggest challenges today is fake news. This is information that is made to look real but is actually made up to fool people. Media literacy gives us the tools to spot fake news by checking where the information comes from, who is sharing it, and whether other reliable sources are reporting the same thing. By being careful and checking the facts, we can avoid being tricked by false information.

Using Information Wisely

Information isn’t just about news. It’s also about understanding how to use the internet safely and responsibly. Media literacy teaches us to protect our private information online, to be respectful to others, and to understand how our clicks and shares can spread information quickly, for better or for worse. It’s like learning the rules of the road before driving a car.

Advertising and Persuasion

Advertisements are everywhere, trying to persuade us to buy things or think a certain way. Media literacy helps us see the tricks advertisers use to grab our attention and make us want something. By understanding these tricks, we can make better choices about what we buy and believe.

Creating Media

Media literacy is not just about what we take in; it’s also about what we put out into the world. With smartphones and the internet, anyone can be a creator. Media literacy teaches us how to share our own stories and ideas in a clear and honest way, and how to respect other people’s rights and feelings when we do.

In conclusion, media and information literacy is an important skill for everyone, especially students. It helps us navigate through the vast amount of information we encounter every day and use it in a smart and ethical way. By being media literate, we can be better students, smarter consumers, and more responsible citizens in our digital world.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Media And Information Effect On Communication

- Essay on Media And Globalization

- Essay on Media And Crime

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

- Student Guide: Information Literacy | Meaning & Examples

Student Guide: Information Literacy | Meaning & Examples

Published on May 13, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on May 31, 2023.

Information literacy refers to the ability to find, evaluate, and use sources effectively. The term covers a broad range of skills, including the ability to:

- Navigate databases

- Find credible sources

- Cite sources correctly

Table of contents

Why is information literacy important, information literacy skills, finding sources, evaluating sources, citing sources, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about information literacy.

The vast amount of information available online means that it can be hard to distinguish accurate from inaccurate sources. Published articles are not always credible and sometimes reflect a biased viewpoint intended to sway the reader’s opinion.

Outside of academia, think of the concept of fake news : deliberately spreading misinformation intended to undermine other viewpoints. Or native advertising , designed to match other content on a site so that readers don’t notice they’re reading an advertisement.

It’s important to be aware of such unreliable content, to think critically about where you get your information, and to evaluate sources effectively, both in your research and in your media consumption more generally.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Information literacy is really a combination of skills and competencies that guide your research. Each stage of a research project, from choosing a thesis statement to writing your research paper , will require you to use specific skills and knowledge.

Being information literate means that you:

- Know how to find sources

- Can assess the authority and credibility of a source

- Can distinguish biased from unbiased content

- Can use relevant sources to inform your research

- Understand what constitutes plagiarism

- Know how to cite your sources correctly

An early stage in the research process is finding relevant sources. It’s important to understand how to search for these sources efficiently.

First, you need to consider what kind of sources you’re looking for. This will depend on the topic and focus of your project, and what stage you are at in the research process.

In the beginning, you may be looking for definitions or broad overviews of a topic. For this, you might use a tertiary source , like an encyclopedia or a dictionary, that is just for your own understanding. Further along, you might look for primary and secondary sources that you will actually cite in your paper. It’s important to ensure that all sources you consult are reliable.

- Websites: Look for websites with legitimate domain extensions (.edu or .gov).

- Search engines: When using search engines to find relevant academic journals and articles, use a trusted resource, like Google Scholar .

- Databases: Check your institution’s library resources to find out what databases they provide access to. Consider what databases are most appropriate to your research.

Finding the right sources means:

- Having a clear research problem

- Knowing what databases and journals are relevant to your research

- Knowing how to narrow and expand your search

Once you have a well-defined research problem, specific keywords, and have chosen a relevant database, you can use Boolean operators to narrow or expand your search. With them, you can prioritize and exclude keywords and search for exact phrases.

Evaluating the quality and credibility of a source is an important way of filtering out misinformation. A reliable source will be unbiased and informed by up-to-date research, and it will cite other credible sources.

You can evaluate the quality of a source using the CRAAP test . “CRAAP” is an acronym that informs the questions you should ask when analyzing a source. It stands for:

- Currency: Is the source recent or outdated?

- Relevance: Is it relevant to your research?

- Authority: Is the journal respected? Is the author an expert in the field?

- Accuracy: Is the information supported by evidence? Does the source provide relevant citations?

- Purpose: Why was the source published? What are the author’s intentions?

How you evaluate a source based on these criteria will depend on the specific subject. In the sciences, conclusions from a source published 20 years ago may have been disproven by recent findings. In a more interpretive subject like English, an article published decades ago might still be relevant.

Just as you look for sources that are supported by evidence and provide correct citations, your own work should provide relevant and accurate citations when you quote or paraphrase a source.

Citing your sources is important because it:

- Allows you to avoid plagiarism

- Establishes the credentials of your sources

- Backs up your arguments with evidence

- Allows your reader to verify the legitimacy of your conclusions

The most common citation styles are:

- APA Style : Typically used in the behavioral and social sciences

- MLA style : Used in the humanities and liberal arts

- Chicago style : Commonly used in the sciences and for history

It’s important to know what citation style your institute recommends. The information you need to include in a citation depends on the type of source you are citing and the specific citation style you’re using. An APA example is shown below.

You can quickly cite sources using Scribbr’s free Citation Generator .

If you want to know more about ChatGPT, AI tools , citation , and plagiarism , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- ChatGPT vs human editor

- ChatGPT citations

- Is ChatGPT trustworthy?

- Using ChatGPT for your studies

- What is ChatGPT?

- Chicago style

- Paraphrasing

Plagiarism

- Types of plagiarism

- Self-plagiarism

- Avoiding plagiarism

- Academic integrity

- Consequences of plagiarism

- Common knowledge

Information literacy refers to a broad range of skills, including the ability to find, evaluate, and use sources of information effectively.

- Know how to find credible sources

- Use relevant sources to inform your research

It can sometimes be hard to distinguish accurate from inaccurate sources , especially online. Published articles are not always credible and can reflect a biased viewpoint without providing evidence to support their conclusions.

Information literacy is important because it helps you to be aware of such unreliable content and to evaluate sources effectively, both in an academic context and more generally.

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

The CRAAP test is an acronym to help you evaluate the credibility of a source you are considering using. It is an important component of information literacy .

The CRAAP test has five main components:

- Currency: Is the source up to date?

- Relevance: Is the source relevant to your research?

- Authority: Where is the source published? Who is the author? Are they considered reputable and trustworthy in their field?

- Accuracy: Is the source supported by evidence? Are the claims cited correctly?

- Purpose: What was the motive behind publishing this source?

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, May 31). Student Guide: Information Literacy | Meaning & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/information-literacy/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, how to avoid plagiarism | tips on citing sources, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Home — Essay Samples — Information Science and Technology — Digital Literacy — The Importance of Media and Information Literacy

The Importance of Media and Information Literacy

- Categories: Digital Literacy

About this sample

Words: 696 |

Published: Sep 1, 2023

Words: 696 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Information Science and Technology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 985 words

1 pages / 594 words

3 pages / 1146 words

4 pages / 1806 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Digital Literacy

In our increasingly interconnected world, where technology is deeply woven into the fabric of our daily lives, the specter of computer threats looms large. From malware attacks to hacking and data breaches, the digital landscape [...]

Liu, Ziming. 'Digital Reading.' Communications in Information Literacy, vol. 6, no. 2, 2012, pp. 204-217. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2012.6.2.4

In today's rapidly evolving digital landscape, the importance of media and information literacy to students cannot be overstated. As the digital realm continues to shape how we access, consume, and share information, equipping [...]

In an era dominated by information and communication technologies, the importance of media literacy has never been more profound. As individuals interact with an array of media platforms and consume a deluge of information [...]

Morphological Image Processing is an important tool in the Digital Image processing, since that science can rigorously quantify many aspects of the geometrical structure of the way that agrees with the human intuition and [...]

The study in ICT based library and Information Resources and services: a case study of Karnatak Arts, Science and Commerce College, Bidar. The present study demonstrates and elaborates the primary way to learn about ICTs, the [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Chapter 9: Media and Information Literacy

Oreva had nearly two dozen tabs up, showing various websites, videos, and journal articles on her research topic. At first, she was excited by all the information she was findings on the Mali Empire, a Western African Kingdom that flourished from about 1200 to 1600 ADE, that she wanted to present her informative speech on for class. However, as the night deepened, and it dawned on her that she might be pulling an all-nighter at the library, she became more and more despondent. Now, she just listlessly clicked from tab to tab, unable to concentrate on any source for long because there was just so much to read on the topic. A hand on her should startled her out of her reverie: “Hey, are you okay,” said a woman with glasses and brown hair, standing behind her and looking over her shoulder. “Wow, it looks like you have quite a lot of work ahead!” “ Tsh -yeah,” Oreva grumped. “I’m going to be here all night at this rate.” “Do you know how you’re going to organize all of those sources? Do you have some system?” “If you mean, ‘Do I have enough coffee to stay awake all night reading’ then yes,” Orevea joked. “Nah, I mean an actual system , ” the woman laughed. “Do you mind if I gave you some tips? ” “ Sure , but why are you being so helpful? To I look that clueless? ” Oreva asked. “ Oh goodness, no , ” the person reassured . “ I’m sorry, I should have introduced myself. My name’s Rebecca and I’m a research librarian. I’m here to help!”

Have you faced the same trouble as Oreva when looking for credible information? On the surface, it seems like it has never been easier to find material on any topic, whether on politics, fashion, science, relationships, or culture. To get this information, most people turn to search engines. Google search is the most used search engine on the internet, constituting nearly 92% of search engine market and processing nearly 9 billion requests per day (Mohsin, 2023). Although Google is an amazingly efficient search engine, as we talked about in Chapter Eight, it is a webcrawler program —meaning it picks up anything on the web that it detects is similar to your search keywords as well as other considerations such as advertisements and traffic. As such, search engines such as Google , Bing , Yahoo , or DuckDuckGo do not, and cannot, evaluate whether the information your search gets is necessarily factual, reliable, or credible, only what is related or paid for.

Another way that many people get their information from is their preferred social media platform. As Walker and Matsa (2021) found, Facebook still has the largest share of U.S. Americans who get their news from that platform (31%). However, for adults between 18-29, the preferred platforms are Snapchat (63%), TikTok (52%), Reddit (44%), and Instagram (44%) (Walker & Matsa, 2021). Collectively, approximately 79% of U.S. Americans reported getting news through social media websites. Much like the Google search engine, these searches may lead you to what is viral, popular, or trending, but not necessarily what is factual. Social media platforms also inhabit a grey area in media laws—on one hand they are not content producers of the news and have little legal obligation to ensure what is shown on their platform is credible information. On the other hand, they have enormous influence on how people interact with the news because it is the primary way people do engage with media content. Some social media companies have tried to—with varying degrees of success and effort—to combat misinformation , but since their revenue is advertisement generated, they have a monetary incentive to push information that promotes engagement (no matter the reason) not facts.

Unfortunately, there are many bad actors who take advantage of this weakness in search engines or social media platforms. For example, China’s “ Great Fire Wall ” serves to keep out content produced outside of their country while its 50 Cent Army (or wǔmáodǎng) amplifies pro-China propaganda abroad. Russia’s Internet Research Agency is a well-known troll-farm, spreading disinformation and propaganda in an effort to increase tensions, unrest, and dysfunction within enemy countries (including the United States) (Craig Silverman, 2023) while cracking down on Western internet traffic as it pursues its unjust war against Ukraine (Bandurski, 2022). Elon Musk, the owner of Twitter , has cut down on Twitter’s infrastructure to identify, track, and remove untrue, malicious, and unsubstantiated content (Drapkin, 2023) while Facebook has banned university professors studying the spread of disinformation on its platform (Bond, 2021). Entire platforms, such as The Parlor , Truth Social , 4Chan , and 8Kun pride themselves on having little or no content moderation, allowing users to spread everything from targeted hate campaigns to weird or malicious conspiracy theories such as QAnon .

Social media influencers use their vast networks to sell their products, generate advertisement revenue, and run morally and legally dubious operations, such as Stephen Crowder, Gwyneth Paltrow, or Andrew Tate. All of these problems, and more, are even more frightening in the context of research that has found that the top false news traveled through social networks faster and reach approximately 100 times more people than true news (Vosoughi et al., 2018). Your responsibility, as a content consumer and producer, is to make sure that you can identify, avoid, and create information that is rigorously made and vetted. In a democratic society, people make decisions, and their decisions can only be as good as the information they have to inform them. Spreading or consuming bad information (whether intentionally or not) makes it impossible to come to the best decisions for laws or policies for our communities.

Vetting Sources

The challenge of today is not finding information—it’s finding good information. Unfortunately, most people do not develop their information literacy skills and, instead, rely on mental shortcuts to make their decisions. For example, McGeough and Rudick (2018) found that students in public speaking classes made appeals to authority (e.g., “I found it in the library so it must be credible”), appeals to form/style (e.g., “The article was professionally formatted and in a print newspaper so I thought it was reliable”), appeals to popularity (e.g., “A lot of people use this source so it must be good”), and appeals to their own beliefs (e.g., “I am pro-guns and 2 nd Amendment, so I searched for information on ‘problems with gun control’”) when making their presentations. There are many reasons people rely on these shortcuts—lack of formal education, time constraints, stress, or unwillingness to develop ideas that are contrary to their important social groups (e.g., their religion or family). These shortcuts can influence how you vet, read, and use information for your presentations. Many times, students make decisions to choose their information sources because they have limited time (e.g., waiting until the night before an assignment is due) and cognitive bandwidth (e.g., they are stressed due to other class’s demands on time and attention). However, now is the time to develop these skills. If you do not know how to identify or create factual content, then you are more likely to make information choices based on convenience instead of rigor.

In this section, we offer one way that you can start to develop a stronger set of information literacy skills. We wish to be clear—this is not the only way to vet information, nor should this be the end of your journey on being a better information consumer or producer. You will need to routinely practice, revise, and update your skills. Doing so is especially important because internet trolls, online scammers, predatory corporations, and malicious governments are constantly updating their strategies for spreading misinformation and disinformation. Here, we’ll use the information literacy program SIFT to offer some guidance on vetting your sources (Caufield, 2017), informed by the best practices of the Association of College and Research Libraries .

The SIFT method has been found to an excellent way for students to begin learning information literacy skills because it encourages lateral reading (Brodsky et al., 2021). SIFT includes four moves: stop, investigate the source, find trusted coverage, and trace back to the original.

Before you even begin searching the Internet for information, STOP. What is your research purpose (e.g., to persuade, inform, or motivate)? What are you trying to do with the information you are looking at? Are you being open to competing or opposing viewpoints or have you searched using keywords that will automatically limit what kind of information you are going to get? Often, novice searchers have a vague idea of what they are looking for and then land on the first source that seems to connect to their topic. If you search this way, you are likely to land on information that has a particular viewpoint and then find yourself over focusing on it and excluding other information. Worst case scenario, you may find yourself in an echo chamber regardless of the credibility of information. Next, once you have found a source or a series of sources, STOP. Do you already think this source is credible, and if so, why? Relying on it because it is the first result of a search or because it agrees with your beliefs are poor reasons for relying on it. If you don’t know if it is credible or not, what criteria will you use to ascertain whether the source is worthwhile? Here, you should look at the reputation of the outlet (e.g., the news media corporation, academic journal, social media content producer, or individual expert or witness). Do they have a history of truth telling? Or, maybe they only have a history of reporting information that already affirms your beliefs or discounts/ignores competing views. If you don’t know if the source has a history of disseminating credible information, then you need to execute the next moves to ascertain its reliability.

Investigate the Source

If you have encountered a source that you never have before and/or if you don’t know if it is reputable or not, then you need to do some research on the outlet and/or author. What is their expertise and agenda? For example, many non-profit policy organizations such as the Heartland Institute , Heritage Institute , Cato Institute , Americans for Tax Reform , and the Family Research Council receive millions of dollars in donations from tobacco, oil, and gas industries or conservative religious groups. As result, a great deal of their policy downplays the harms of smoking cigarettes, hydraulic fracturing (i.e., fracking), climate change, and/or attacks LGBTQ rights and families. Many people might believe these are reputable sources because they are .org sites instead of .com sites, but .org simply means that it is an organization—there is no obligation on the part of that organization to give better information due to its .org status. This is not to say you should never visit these sources. There might be a need to know what a problem is or why it hasn’t been solved yet, and going to sources that promulgate bad information is a way to trace how untrue, harmful, or hateful content can negatively affect decision-making about a variety of issues. However, sources that are biased because of politics, faith, money, advertisement, or personal relationships must be approached with caution. By figuring out not just what a source says, but why it says it and who benefits from its advocacy, you can be a better content producer and consumer for your community.

Find Trusted Coverage

Next, is their advocacy in line with other outlets and, if not, why? That is, you should go to websites that offer information on the same topic to see if there is broad consensus or disagreement about the topic. For example, maybe the source you are using is older than a more recent source, indicating that knowledge in this field has changed. Or, the author has a fringe or minority view within a field that has broad consensus about an issue. To be clear, we are not saying that information that is generally agreed upon is always correct. However, when there is broad agreement on a topic then it requires a greater burden of proof for those who advocate against the established position. For example, NASA reports that approximately 97 percent of scientists agree that climate change is occurring, is affected by human pollution, and will negatively affect people around the world. But, don’t just take NASA’s word for it— The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change , the United Nations , World Health Organization , and hundreds of other governmental, corporate, non-profit, and academic sources agree on these propositions. To disagree with this, a person would need to demonstrate climate change is not occurring, that if it is occurring humans aren’t the cause for it, and/or that climate change will not harm people— an extremely high burden of proof given the number of sources that agree these things will occur or are occurring. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence and refuting generally agreed on propositions is considered an extraordinary claim. All-too-often, people promote misinformation or disinformation by claiming to have insider knowledge that “they” (i.e., Big Government , Big Pharma , the Illuminati , the Lizard People , etc.) don’t want you to have. This type of discourse is especially useful on U.S. Americans because, culturally, most of our media and history is shaped by the idea that brave truth-tellers, patriots, or morally clear-eyed individuals are often a lone voice against a throng of the evil and ignorant. However, it is important to remember that real-life decisions should be based on facts and facts are something that can and should be agreed to and recognized by the majority of experts on a given topic (no, your uncle posting bad memes information from FreedomEagle.net/ patriotsforcoal is not an expert!). Those who cannot meet this burden of evidence only use this cultural idea to hide the fact that they simply cannot meet the evidential burden of their position and do not want you to draw on other sources that might disagree with their analysis.

Trace the Original

Finding the original source of information is more and more important as it becomes easier to share content and information across the Internet and social media. For example, in response to a medical study, news outlets reported: “Silent, not deadly; how farts cure diseases” (Burnett, 2018), “Sniffing your partners’ farts could help ward off disease” (Sun, 2017), and “Scientists say sniffing farts could prevent cancer” (UPI, 2014). However, tracing their claims to the original study reveals a much different picture. The study (Le Trionnaire, 2014) showed how hydrogen sulfide, compound associated with (among other things) the disgusting smell of rotten eggs or human flatulence, may be delivered to the mitochondria of cells to as a way to fight disease and cancer. The study did not say farts cured disease or cancer or even that the compound hydrogen sulfide did; rather, the report made the more limited claim that the compound may be used as a tool in fighting disease and cancer and its efficacy is promising. Pictures, video clips, tweets, reactions, and even (as we see in this example) full medical studies can be condensed into clickbait titles that are meant to provoke anger, frustration, laughter, or sadness—because in the world of social media algorithms all of those emotions translate into engagement which means more advertisement dollars. You must be able to trace information to its original source and then evaluate whether the information that you have read is accurately reported and credible. Otherwise, you may find yourself sniffing farts for no reason!

It is important to remember that no one, single study, article, podcast, or YouTube video proves or disproves anything. Rather, it is only in reading laterally multiple sources or studies published over years that a clearer picture of credible information emerges. Using SIFT, you can begin to develop the skills that allow you to see information claims as part of a wider network of efforts moving from ignorance to knowledge. For example, the non-profit group Center for Scientific Integrity that tracks retracted academic articles (i.e., articles that have been published but later removed because of research misconduct or fabrication) shows how some scholars have abused their responsibilities as researchers. In one case, Yoshitaka Fuji, a Japanese researcher in anesthesiology and ophthalmology, was forced to retract 183 published papers (Stromberg, 2015)!

On one hand, it is chilling to know how long Fuji was able to elude detection. On the other hand, catching errors (whether intentionally made or not) is exactly why scholars engage in lateral reading. Researchers may review the findings of a study against other studies to see if their findings agree with past work or conduct the same tests to see if they get approximately the same result. If they don’t, then it raises questions about the surety of the previous study’s claims, inviting scrutiny and changing knowledge claims as more evidence supports or doesn’t the original study—which is ultimately how Fuji’s research was found to be fraudulent.

All of this is to say, there is no magic bullet, no one good type of source that will ensure that you have good information. It is a constant practice and one that encourages you to not take mental shortcuts. Working to make sure you are informed, demanding that your sources provide factual information, and informing others with high quality information are the only ways that all of us live in a healthy information ecosystem. As the old saying warns, “Garbage in, garbage out,” or, when you consume bad information, you’ll likely produce bad decisions or conclusions. So, don’t settle for garbage!

Reading Journal Articles

You’ve found a variety of sources, used SIFT to test them, and feel confident that they offer a clear picture of the side or sides of an issue. Great! But, as you begin trying to read the journal articles, you find them to be incredibly dense and difficult to get through. Don’t worry—this is a common problem experienced by novice researchers. We find that one of the challenges of reading research articles is that novice researchers try to read the entire article from start to finish to ascertain if it is worth using or vetting. We wish to be clear—not all journal articles follow the format guidelines we explain here. Some articles are opinion pieces, reviews of books, arguments with fellow researchers, or creative pieces that aren’t easily captured in the type of organization we outline here. Therefore, we implore you to go beyond the advice we give here and develop a wide set of tools for reading a variety of research articles.

However, we do believe this approach to reading articles a great place to start and can provide the foundation for being a good researcher. Therefore, we encourage you to follow this order of reading your articles as you begin researching so you can reduce your time searching for articles, increase your comprehension, and utilize the most valuable knowledge in the manuscript. As you develop as a researcher in your area of study, you will most likely need to develop new skills until you reach mastery in your subject.

Title/Abstract

The title of a research article will contain the major concepts, ideas, theories, method of analysis, or insights from the study. For example, the study “ Highlighting the intersectional experiences of students of color: A mixed methods examination of instructor (mis)behavior ” by Vallade et al. (2023) describes the research participants (i.e., students of color), major concepts (i.e., intersectional experiences and instructor (mis)behaviors), and research methodology (i.e., mix-methods or a combination of quantitative and qualitative research). You should also read the study’s abstract, which appears on the first page of the article. The abstract is usually a 100–300-word outline of the study’s purpose, relevant literature, research method/design, major findings, and implications. By reading the title/abstract, you can get a good idea on whether the article connects to the topic you are studying or not. If not, go onto the next article and read its title and abstract. If so, then you need to proceed to the next step.

Introduction

The introduction of the article is usually not notated or labeled as such. Rather, it is simply the first part of the article, which proceeds from the very start to the first major section heading of the article. The introduction of the article should detail the research purpose, which usually contains two elements. The first is the ‘practical’ issue or the actual challenge, issue, or topic the article responds to. This information lets the reader know what problems they will be able to solve or mitigate by finding out what the researchers found. The second, is the ‘theoretical’ issue, which details the academic questions or gaps that the study tries to address. This content shows the reader how the researchers are building on past scholarship in this area and justifying the need for the present study.

Literature Review

The final section you should read is the literature review. Sometimes the literature review is named ‘Literature Review,’ but often it is not explicitly named. Instead, it is understood that the first major section heading after the introduction is the beginning of the literature review. The purpose of the literature review is to provide a summarization of all the past research that has been conducted in the past about the topic. The literature review should also show how the current research is meaningfully building on that information and should end with the hypotheses or research questions that the study will address. Remember, you should rarely, if ever, cite work from the literature review. Rather, when you find any important information you find in this section, you should find the literature being cited in the reference section and go read that particular study or source.

The method section will describe who (e.g., the participants and their demographic information) or what (e.g., the documents, speeches, or content) they got data from. It will also detail what procedures were used to gather data (e.g., surveys or interviews) or texts (e.g., documents, speeches, or content). For example, in a statistical report, it will show what survey instruments were used and how reliable they have been in past studies as a way to justifying their use in the present study. Finally, the section will detail how the researchers analyzed the data in order to come up with new insights. This could be the author or author team’s explication of their statistical procedures used to test a hypothesis. The method section is important to examine because even if the results and discussion are important, if the method section shows a poorly designed research project, then those insights showed be read with extreme caution.

Results/ Discussion

Now you are going to skip everything between the introduction and the section labeled ‘Results’ or ‘Findings’ and ‘Discussion’ or ‘Implications’ in the article. Novice researchers often think that the whole research article is something that can be cited from. However, information in the introduction, literature review, or method sections is often a summary of past research or information on the topic. In other words, it a secondary source, since you are relying on the author of the present article to understand and convey the information from past studies to you. The information in the results section should be the statistical tests, interview excerpts, or other information that is produced through the application of the research method. The discussion section should summarize what the findings or results of the research article were as well as detail (or, discuss) the implications of the study for the production of knowledge on the topic. Much like the introduction, the discussion will most likely explain the ‘practical’ and ‘theoretical’ implications of the study. In other words, it will describe how the knowledge produced through the research should inform peoples’ actions as they try to address the problems the research responds to (practical) as well as make a case for how it extends or challenges the existing research in that area for future researchers to build on in their own work (theoretical). The information in the article that is new, or is a primary source, is the information in the results and discussion. Therefore, if you find something in the literature review that is helpful, important, or worth noting, you should go to the reference list, find the source, and read the original source so you can cite it in your own work. If you don’t, and you cite information from the literature review in your own work, this is a form of academic dishonesty because you never actually read the original source.

We admit, sometimes research writing is needlessly difficult to read. We remember the first time we read an article that stated, “Due to the established lacunae in the field…” and were intimidated by the word “lacunae.” What does it mean? How important is it? It sounds so daunting! Lacunae, however, just means “gaps” or “holes.” The author, in establishing that there are missing answers to questions that were important to their field of study, used a word that immediately caused consternation and confusion from their audience. This word choice is an example bad writing because it needlessly confuses their audience, which should always be avoided! However, sometimes, technical jargon is necessary. The difference between a vein or artery, mitochondrion or ribosomes, verb or adjective, or discourse and rhetoric are important distinctions within their respective fields of study.

Often, we find that novice researchers, when encountering a new or unfamiliar word, just pass over the word in their reading and don’t use dictionaries to look it up because they: A) aren’t motivated to; or B) they feel like doing so is an admission of ignorance. However, if you wish to be able to consume and vet knowledge from a source, you will need to be able to understand what is written and that burden, ultimately, falls on you (the reader) to do the work to figure it out. Passing over a word, whether due to laziness or anxiety, robs you of a chance to grow your knowledge on a subject and eliminates the possibility that you can use or refute the information in a meaningful way.

Verbal and In-Text Ways to Cite Sources

After you have found a wide range of sources on the topic, winnowed them down to the ones that are the most reliable and credible, and mined them for information regarding your topic, it is time to put them in your speech or writing. We find that citing information can be some of the most anxiety producing work that students do. Often, they report getting incomplete, conflicting, or erroneous information about citing sources. As a result, many students put little effort into their citation practices because they think, “I’m going to get it wrong anyway, so why try?”

Conversely, some students rely solely on computer apps, such as EasyBib , BibTex , or Bib I t Now to do their citations for them. Relying on apps doesn’t build your information literacy skills. Doing so means you never bothered to learn how to do it correctly since there was an app that you thought would do it for you and, therefore, you won’t be able to tell if the program is producing a correct citation or not. As we’ll see later, these programs often incorrectly cite work. In short, you need to learn how to properly cite materials and practice those skills.

We cannot stress enough that properly citing your sources is an incredibly important practice in your work. Not only does it ensure that you are sharing information with others in a responsible way by letting them know where you got your information from, it also increases your credibility with your audience because they recognize your effort to keep them fully informed. Citation guides provide standardized system for reporting your sources so that your listeners or readers know exactly how and where to find your sources. There are a variety of ways to cite your information for your audience, but in this chapter, we’ll focus on the two most common styles: the American Psychological Association (APA) style guide and the Modern Language Society (MLA) handbook.

Verbal Citation

When giving a presentation, you need to verbally cite your sources so your audience can ascertain the quality of your sources. Failing to do so can make your audience to doubt or disagree with the content of your speech even if your information is correct. To avoid this, you need to verbally cite your sources in a way that supports your work while not being overly cumbersome to your speech and interrupting your flow. We suggest you use three pieces of information every time you cite something verbally: Name of Source , Credibility Statement of Source , Year of Publication . Here are a few examples of what you might say:

Dr. McGeough, who is a leading researcher in ancient Greek rhetorical philosophy, argued in a 2023 research article that…

In 2022, the World Health Organization, an internationally renowned inter-governmental body that studies health and medicine, reported…

In a research study spanning from 2015 to 2020, the internationally recognized data scientists at the Pew Research Center tracked voting habits of various groups and found…

Do you see the Name of Source , Credibility Statement of Source , Year of Publication in each of the examples? Although you can report the information in a variety of ways, each contains the information. Typically, you don’t have to give more information than this because doing so makes your speech awkward and filled with a lot of extraneous information. If your audience wants more specific information about your sources, they can ask for your written citations. You should have a “References” (APA) or “Works Cited” (MLA) paper or (if using a slideshow app such as PowerPoint or Google Slides) on the final slide. In those case, make sure to write out the reference information based on our advice below.

In- T ext Citation

There are two primary ways that you can cite information in text, or in the body of your writing. The first is called summary or synopsis . Luckily, we cite and report information the same whether it is a summary or synopsis. Let’s take the following passage that we might find in an academic journal article (sometimes called a periodical ): “After surveying 200 participants, the study found that people like dogs more than cats, hamburgers more than hotdogs, and cake more than pie.” Now, we’ll create a summary in both APA and MLA:

McGeough and Golsan (2023) discovered that people like dogs more than cats.

Researchers have discovered that people like dogs more than cats (McGeough & Golsan, 2023).

McGeough and Golsan discovered that people like dogs more than cats (1).

Researchers have discovered that people like dogs more than cats (McGeough and Golsan 1).

The sentences can be written either way, but both contain information that is specific to their citation style. Notice how in APA, the in-text citation shows the authors’ last names, the year of publication, and uses the ampersand symbol (“&”) whereas the authors last names, the page number the information was found on, and the word “and” was needed in MLA (we made up the year of publication and page number for the sake of the example). Also, notice how the summary focuses on one finding, even though the research found peoples’ preferences on three different things. If we had reported on all three findings, in our own words, then it would have been a synopsis. We can also write a direct quote if we cite it properly. For example:

Past research has found that “people like dogs more than cats, hamburgers more than hotdogs, and cake more than pie” (McGeough & Golsan, 2023, p. 1).

Past research has found that “people like dogs more than cats, hamburgers more than hotdogs, and cake more than pie” (McGeough and Golsan 1).

Note, that in APA, we have now added the page number to help a reader find the information that we are quoting whereas citation in MLA doesn’t change. In both cases, though, we use quotation marks to indicate that we are directly quoting material from a source. You must copy information from the source word-for-word if you are using a direct quotation.

Written References

Your references (APA) or works cited (MLA) pages are where you collect all of the information for your sources into one place. Doing this makes it easier for your reader to find the information you use in your writing. Let’s use the article, “Academic advising as teaching: Undergraduate student perceptions of advisor confirmation” and see how to cite it properly in your papers. First, let’s compare out how the citation appears on the article’s first page , Bib It Now , and proper APA :

Scott Titsworth, Joseph P. Mazer, Alan K. Goodboy, San Bolkan & Scott A. Myers (2015) Two Meta-analyses Exploring the Relationship between Teacher Clarity and Student Learning, Communication Education, 64:4, 385-418, DOI: 10.1080/03634523.2015.1041998

(Article’s first page)

Titsworth, S., Mazer, J. P., Goodboy, A. K., Bolkan, S., & Myers, S. A. (2015). Two Meta-analyses Exploring the Relationship between Teacher Clarity and Student Learning. Communication Education. Retrieved from https://www-tandfonline-com.proxy.lib.uni.edu/doi/full/10.1080/03634523.2015.1041998

(Bib It Now)

Titsworth, S., Mazer, J. P., Goodboy, A. K., Bolkan, S., & Myers, S. A. (2015). Two meta-analyses exploring the relationship between teacher clarity and student learning. Communication Education , 64 (4), 385-418. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2015.1041998

Can you see the differences? The third citation is the correct way to cite it in APA. The differences you see are why it is so important to know how to cite information properly. If you just relied on the journal article or app, then your citation would be incorrect and you wouldn’t be informing your audience of your information in the standardized way. Let’s try it with MLA now:

Titsworth, Scott, et al. “Two Meta-analyses Exploring the Relationship between Teacher Clarity and Student Learning.” Communication Education, 9 June 2015, www-tandfonline-com.proxy.lib.uni.edu/doi/full/10.1080/03634523.2015.1041998.

Titsworth, Scott, et al. “Two Meta-analyses Exploring the Relationship between Teacher Clarity and Student Learning.” Communication Education , vol. 9, no. 4, 2015, pp. 385-418, https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2015.1041998 .

Again, can you spot the differences? The final example is the correct way to cite an article in MLA.

The examples we just gave are for journal articles, but there is a unique way to cite almost anything: tweets, textbooks, websites with authors, websites without authors, YouTube videos, and a whole lot more. There are thousands of books, blogs, online writing centers, and YouTube/TikTok videos on citation. We suggest you visit a reputable website that offers sample papers so you can compare your work to what is the correct, standard way of citing and formatting your paper. We recommend (and often use ourselves!) the Online Writing Lab (or OWL) website from Purdue University, which offers sample papers in APA and MLA .

As you look at the sample paper and your own, sing the children’s song from Sesame Stree t : “One of these things is not like the others/One of these things just doesn’t belong/Can you tell which thing is not like the others/By the time I finish my song?” That is, if your paper looks different than the sample paper’s formatting, in-text citation, or reference/works cited page, yours is most likely the one that is incorrect—fix it! When students turn in papers that do not adhere to proper formatting, then there are two primary explanations: either the student didn’t take the time/energy to do the work properly or the student cannot follow Sesame Street rules and make corrections to their paper based on comparing their work to a sample paper. Frankly, neither is a good look, which is why your professors (and audience) will get frustrated if you don’t take the time to properly reference your sources.

When you are trying to inform, persuade, or motivate your audience, you need to be able to communicate why you have come to the conclusions you have based on the evidence you have gathered. If you cannot explain why you believe something or if you believe something for poor reasons (e.g., “my family believes this,” “my friends all say this,” or “everyone knows this”), then you have not lived up to your responsibility to be a good, careful researcher. Being able to vet your evidence is the first step to not only demanding that you are an informed person, but that others around you live up to their responsibility to communicate in ways that are factually supported about important topics or problems you and your community may face.