Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a literary analysis essay | A step-by-step guide

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on January 30, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on August 14, 2023.

Literary analysis means closely studying a text, interpreting its meanings, and exploring why the author made certain choices. It can be applied to novels, short stories, plays, poems, or any other form of literary writing.

A literary analysis essay is not a rhetorical analysis , nor is it just a summary of the plot or a book review. Instead, it is a type of argumentative essay where you need to analyze elements such as the language, perspective, and structure of the text, and explain how the author uses literary devices to create effects and convey ideas.

Before beginning a literary analysis essay, it’s essential to carefully read the text and c ome up with a thesis statement to keep your essay focused. As you write, follow the standard structure of an academic essay :

- An introduction that tells the reader what your essay will focus on.

- A main body, divided into paragraphs , that builds an argument using evidence from the text.

- A conclusion that clearly states the main point that you have shown with your analysis.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: reading the text and identifying literary devices, step 2: coming up with a thesis, step 3: writing a title and introduction, step 4: writing the body of the essay, step 5: writing a conclusion, other interesting articles.

The first step is to carefully read the text(s) and take initial notes. As you read, pay attention to the things that are most intriguing, surprising, or even confusing in the writing—these are things you can dig into in your analysis.

Your goal in literary analysis is not simply to explain the events described in the text, but to analyze the writing itself and discuss how the text works on a deeper level. Primarily, you’re looking out for literary devices —textual elements that writers use to convey meaning and create effects. If you’re comparing and contrasting multiple texts, you can also look for connections between different texts.

To get started with your analysis, there are several key areas that you can focus on. As you analyze each aspect of the text, try to think about how they all relate to each other. You can use highlights or notes to keep track of important passages and quotes.

Language choices

Consider what style of language the author uses. Are the sentences short and simple or more complex and poetic?

What word choices stand out as interesting or unusual? Are words used figuratively to mean something other than their literal definition? Figurative language includes things like metaphor (e.g. “her eyes were oceans”) and simile (e.g. “her eyes were like oceans”).

Also keep an eye out for imagery in the text—recurring images that create a certain atmosphere or symbolize something important. Remember that language is used in literary texts to say more than it means on the surface.

Narrative voice

Ask yourself:

- Who is telling the story?

- How are they telling it?

Is it a first-person narrator (“I”) who is personally involved in the story, or a third-person narrator who tells us about the characters from a distance?

Consider the narrator’s perspective . Is the narrator omniscient (where they know everything about all the characters and events), or do they only have partial knowledge? Are they an unreliable narrator who we are not supposed to take at face value? Authors often hint that their narrator might be giving us a distorted or dishonest version of events.

The tone of the text is also worth considering. Is the story intended to be comic, tragic, or something else? Are usually serious topics treated as funny, or vice versa ? Is the story realistic or fantastical (or somewhere in between)?

Consider how the text is structured, and how the structure relates to the story being told.

- Novels are often divided into chapters and parts.

- Poems are divided into lines, stanzas, and sometime cantos.

- Plays are divided into scenes and acts.

Think about why the author chose to divide the different parts of the text in the way they did.

There are also less formal structural elements to take into account. Does the story unfold in chronological order, or does it jump back and forth in time? Does it begin in medias res —in the middle of the action? Does the plot advance towards a clearly defined climax?

With poetry, consider how the rhyme and meter shape your understanding of the text and your impression of the tone. Try reading the poem aloud to get a sense of this.

In a play, you might consider how relationships between characters are built up through different scenes, and how the setting relates to the action. Watch out for dramatic irony , where the audience knows some detail that the characters don’t, creating a double meaning in their words, thoughts, or actions.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Your thesis in a literary analysis essay is the point you want to make about the text. It’s the core argument that gives your essay direction and prevents it from just being a collection of random observations about a text.

If you’re given a prompt for your essay, your thesis must answer or relate to the prompt. For example:

Essay question example

Is Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” a religious parable?

Your thesis statement should be an answer to this question—not a simple yes or no, but a statement of why this is or isn’t the case:

Thesis statement example

Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” is not a religious parable, but a story about bureaucratic alienation.

Sometimes you’ll be given freedom to choose your own topic; in this case, you’ll have to come up with an original thesis. Consider what stood out to you in the text; ask yourself questions about the elements that interested you, and consider how you might answer them.

Your thesis should be something arguable—that is, something that you think is true about the text, but which is not a simple matter of fact. It must be complex enough to develop through evidence and arguments across the course of your essay.

Say you’re analyzing the novel Frankenstein . You could start by asking yourself:

Your initial answer might be a surface-level description:

The character Frankenstein is portrayed negatively in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein .

However, this statement is too simple to be an interesting thesis. After reading the text and analyzing its narrative voice and structure, you can develop the answer into a more nuanced and arguable thesis statement:

Mary Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as.

Remember that you can revise your thesis statement throughout the writing process , so it doesn’t need to be perfectly formulated at this stage. The aim is to keep you focused as you analyze the text.

Finding textual evidence

To support your thesis statement, your essay will build an argument using textual evidence —specific parts of the text that demonstrate your point. This evidence is quoted and analyzed throughout your essay to explain your argument to the reader.

It can be useful to comb through the text in search of relevant quotations before you start writing. You might not end up using everything you find, and you may have to return to the text for more evidence as you write, but collecting textual evidence from the beginning will help you to structure your arguments and assess whether they’re convincing.

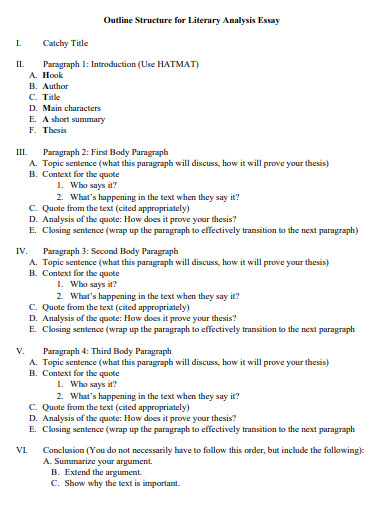

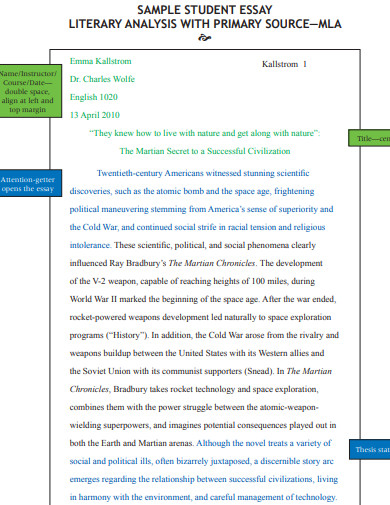

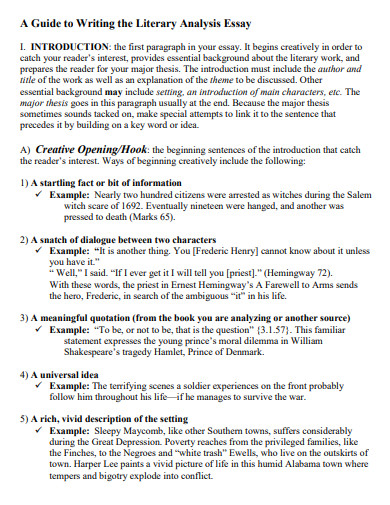

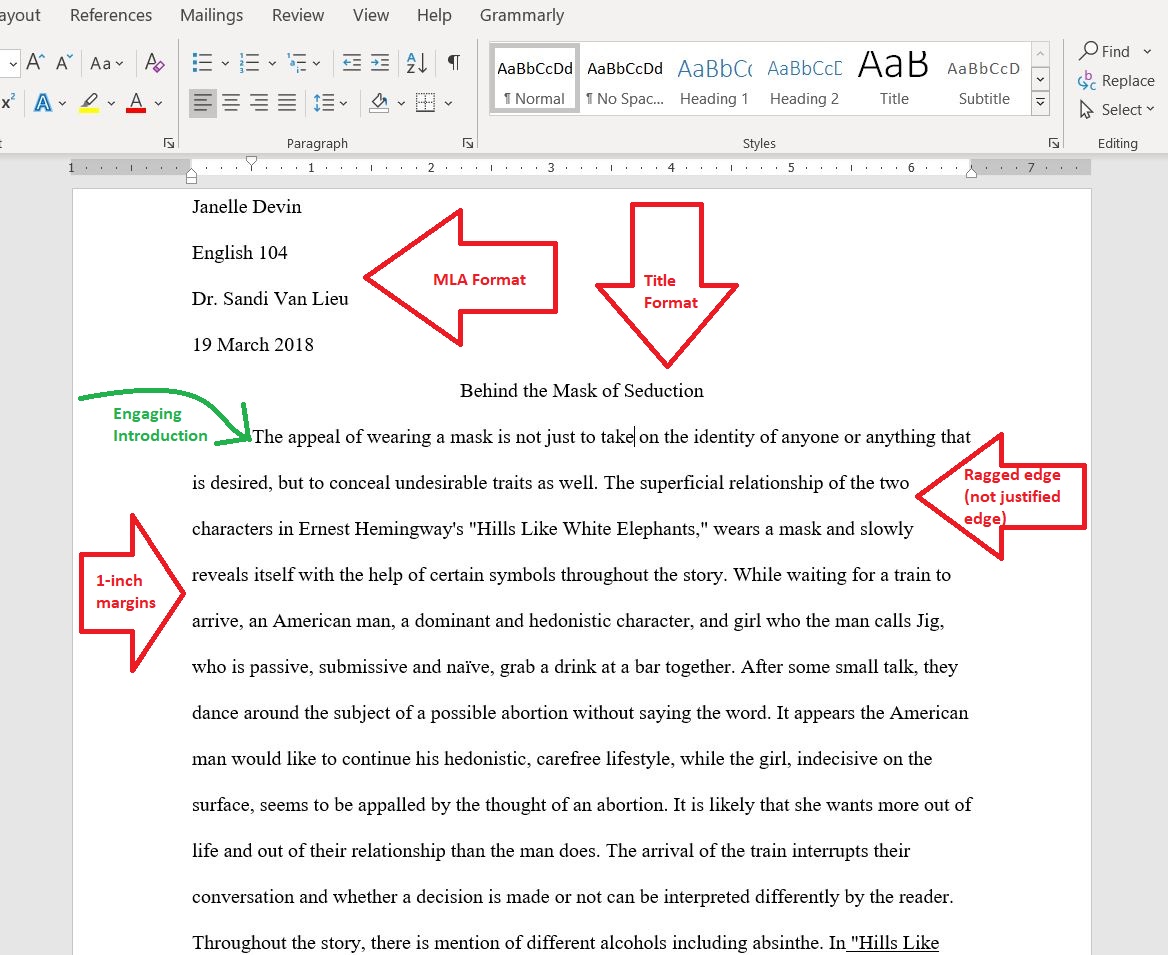

To start your literary analysis paper, you’ll need two things: a good title, and an introduction.

Your title should clearly indicate what your analysis will focus on. It usually contains the name of the author and text(s) you’re analyzing. Keep it as concise and engaging as possible.

A common approach to the title is to use a relevant quote from the text, followed by a colon and then the rest of your title.

If you struggle to come up with a good title at first, don’t worry—this will be easier once you’ve begun writing the essay and have a better sense of your arguments.

“Fearful symmetry” : The violence of creation in William Blake’s “The Tyger”

The introduction

The essay introduction provides a quick overview of where your argument is going. It should include your thesis statement and a summary of the essay’s structure.

A typical structure for an introduction is to begin with a general statement about the text and author, using this to lead into your thesis statement. You might refer to a commonly held idea about the text and show how your thesis will contradict it, or zoom in on a particular device you intend to focus on.

Then you can end with a brief indication of what’s coming up in the main body of the essay. This is called signposting. It will be more elaborate in longer essays, but in a short five-paragraph essay structure, it shouldn’t be more than one sentence.

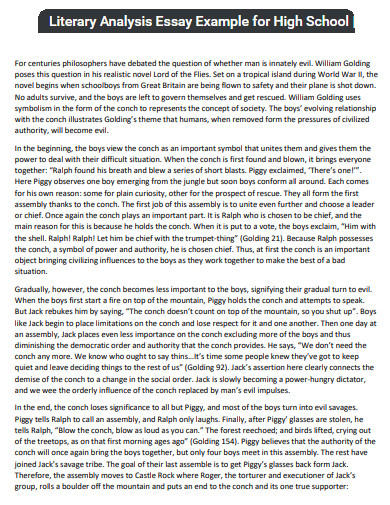

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific advancement unrestrained by ethical considerations. In this reading, protagonist Victor Frankenstein is a stable representation of the callous ambition of modern science throughout the novel. This essay, however, argues that far from providing a stable image of the character, Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as. This essay begins by exploring the positive portrayal of Frankenstein in the first volume, then moves on to the creature’s perception of him, and finally discusses the third volume’s narrative shift toward viewing Frankenstein as the creature views him.

Some students prefer to write the introduction later in the process, and it’s not a bad idea. After all, you’ll have a clearer idea of the overall shape of your arguments once you’ve begun writing them!

If you do write the introduction first, you should still return to it later to make sure it lines up with what you ended up writing, and edit as necessary.

The body of your essay is everything between the introduction and conclusion. It contains your arguments and the textual evidence that supports them.

Paragraph structure

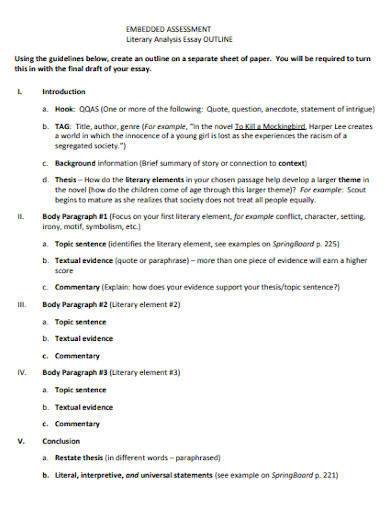

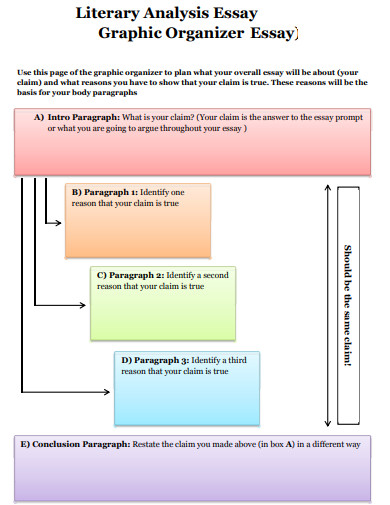

A typical structure for a high school literary analysis essay consists of five paragraphs : the three paragraphs of the body, plus the introduction and conclusion.

Each paragraph in the main body should focus on one topic. In the five-paragraph model, try to divide your argument into three main areas of analysis, all linked to your thesis. Don’t try to include everything you can think of to say about the text—only analysis that drives your argument.

In longer essays, the same principle applies on a broader scale. For example, you might have two or three sections in your main body, each with multiple paragraphs. Within these sections, you still want to begin new paragraphs at logical moments—a turn in the argument or the introduction of a new idea.

Robert’s first encounter with Gil-Martin suggests something of his sinister power. Robert feels “a sort of invisible power that drew me towards him.” He identifies the moment of their meeting as “the beginning of a series of adventures which has puzzled myself, and will puzzle the world when I am no more in it” (p. 89). Gil-Martin’s “invisible power” seems to be at work even at this distance from the moment described; before continuing the story, Robert feels compelled to anticipate at length what readers will make of his narrative after his approaching death. With this interjection, Hogg emphasizes the fatal influence Gil-Martin exercises from his first appearance.

Topic sentences

To keep your points focused, it’s important to use a topic sentence at the beginning of each paragraph.

A good topic sentence allows a reader to see at a glance what the paragraph is about. It can introduce a new line of argument and connect or contrast it with the previous paragraph. Transition words like “however” or “moreover” are useful for creating smooth transitions:

… The story’s focus, therefore, is not upon the divine revelation that may be waiting beyond the door, but upon the mundane process of aging undergone by the man as he waits.

Nevertheless, the “radiance” that appears to stream from the door is typically treated as religious symbolism.

This topic sentence signals that the paragraph will address the question of religious symbolism, while the linking word “nevertheless” points out a contrast with the previous paragraph’s conclusion.

Using textual evidence

A key part of literary analysis is backing up your arguments with relevant evidence from the text. This involves introducing quotes from the text and explaining their significance to your point.

It’s important to contextualize quotes and explain why you’re using them; they should be properly introduced and analyzed, not treated as self-explanatory:

It isn’t always necessary to use a quote. Quoting is useful when you’re discussing the author’s language, but sometimes you’ll have to refer to plot points or structural elements that can’t be captured in a short quote.

In these cases, it’s more appropriate to paraphrase or summarize parts of the text—that is, to describe the relevant part in your own words:

The conclusion of your analysis shouldn’t introduce any new quotations or arguments. Instead, it’s about wrapping up the essay. Here, you summarize your key points and try to emphasize their significance to the reader.

A good way to approach this is to briefly summarize your key arguments, and then stress the conclusion they’ve led you to, highlighting the new perspective your thesis provides on the text as a whole:

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

By tracing the depiction of Frankenstein through the novel’s three volumes, I have demonstrated how the narrative structure shifts our perception of the character. While the Frankenstein of the first volume is depicted as having innocent intentions, the second and third volumes—first in the creature’s accusatory voice, and then in his own voice—increasingly undermine him, causing him to appear alternately ridiculous and vindictive. Far from the one-dimensional villain he is often taken to be, the character of Frankenstein is compelling because of the dynamic narrative frame in which he is placed. In this frame, Frankenstein’s narrative self-presentation responds to the images of him we see from others’ perspectives. This conclusion sheds new light on the novel, foregrounding Shelley’s unique layering of narrative perspectives and its importance for the depiction of character.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, August 14). How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved April 1, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/literary-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, how to write a narrative essay | example & tips, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

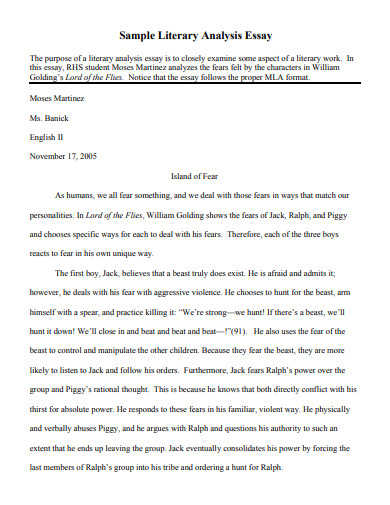

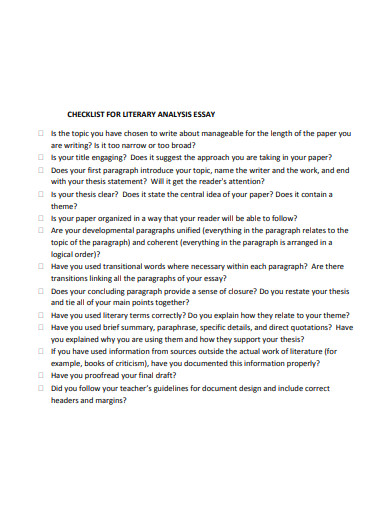

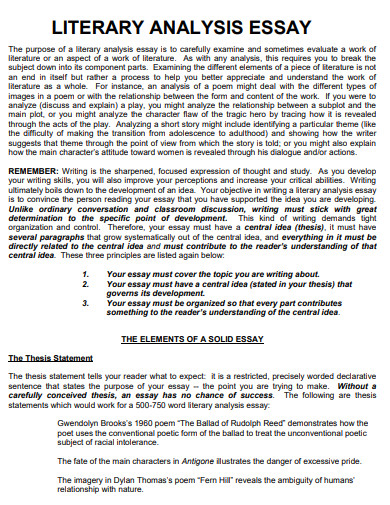

Literary Analysis Essay

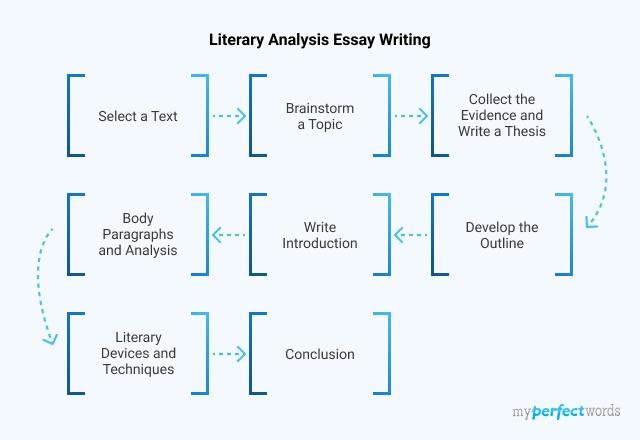

Literary Analysis Essay Writing

Last updated on: May 21, 2023

Literary Analysis Essay - Ultimate Guide By Professionals

By: Cordon J.

Reviewed By: Rylee W.

Published on: Dec 3, 2019

A literary analysis essay specifically examines and evaluates a piece of literature or a literary work. It also understands and explains the links between the small parts to their whole information.

It is important for students to understand the meaning and the true essence of literature to write a literary essay.

One of the most difficult assignments for students is writing a literary analysis essay. It can be hard to come up with an original idea or find enough material to write about. You might think you need years of experience in order to create a good paper, but that's not true.

This blog post will show you how easy it can be when you follow the steps given here.Writing such an essay involves the breakdown of a book into small parts and understanding each part separately. It seems easy, right?

Trust us, it is not as hard as good book reports but it may also not be extremely easy. You will have to take into account different approaches and explain them in relation with the chosen literary work.

It is a common high school and college assignment and you can learn everything in this blog.

Continue reading for some useful tips with an example to write a literary analysis essay that will be on point. You can also explore our detailed article on writing an analytical essay .

On this Page

What is a Literary Analysis Essay?

A literary analysis essay is an important kind of essay that focuses on the detailed analysis of the work of literature.

The purpose of a literary analysis essay is to explain why the author has used a specific theme for his work. Or examine the characters, themes, literary devices , figurative language, and settings in the story.

This type of essay encourages students to think about how the book or the short story has been written. And why the author has created this work.

The method used in the literary analysis essay differs from other types of essays. It primarily focuses on the type of work and literature that is being analyzed.

Mostly, you will be going to break down the work into various parts. In order to develop a better understanding of the idea being discussed, each part will be discussed separately.

The essay should explain the choices of the author and point of view along with your answers and personal analysis.

How To Write A Literary Analysis Essay

So how to start a literary analysis essay? The answer to this question is quite simple.

The following sections are required to write an effective literary analysis essay. By following the guidelines given in the following sections, you will be able to craft a winning literary analysis essay.

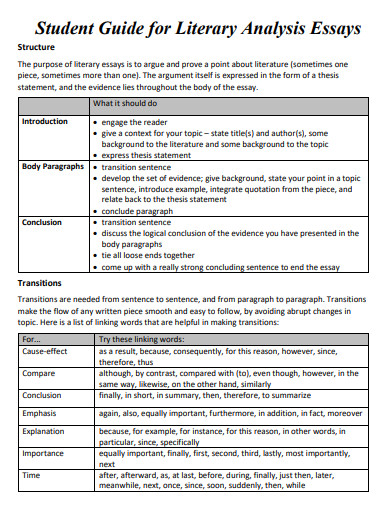

Introduction

The aim of the introduction is to establish a context for readers. You have to give a brief on the background of the selected topic.

It should contain the name of the author of the literary work along with its title. The introduction should be effective enough to grab the reader’s attention.

In the body section, you have to retell the story that the writer has narrated. It is a good idea to create a summary as it is one of the important tips of literary analysis.

Other than that, you are required to develop ideas and disclose the observed information related to the issue. The ideal length of the body section is around 1000 words.

To write the body section, your observation should be based on evidence and your own style of writing.

It would be great if the body of your essay is divided into three paragraphs. Make a strong argument with facts related to the thesis statement in all of the paragraphs in the body section.

Start writing each paragraph with a topic sentence and use transition words when moving to the next paragraph.

Summarize the important points of your literary analysis essay in this section. It is important to compose a short and strong conclusion to help you make a final impression of your essay.

Pay attention that this section does not contain any new information. It should provide a sense of completion by restating the main idea with a short description of your arguments. End the conclusion with your supporting details.

You have to explain why the book is important. Also, elaborate on the means that the authors used to convey her/his opinion regarding the issue.

For further understanding, here is a downloadable literary analysis essay outline. This outline will help you structure and format your essay properly and earn an A easily.

DOWNLOADABLE LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY OUTLINE (PDF)

Types of Literary Analysis Essay

- Close reading - This method involves attentive reading and detailed analysis. No need for a lot of knowledge and inspiration to write an essay that shows your creative skills.

- Theoretical - In this type, you will rely on theories related to the selected topic.

- Historical - This type of essay concerns the discipline of history. Sometimes historical analysis is required to explain events in detail.

- Applied - This type involves analysis of a specific issue from a practical perspective.

- Comparative - This type of writing is based on when two or more alternatives are compared

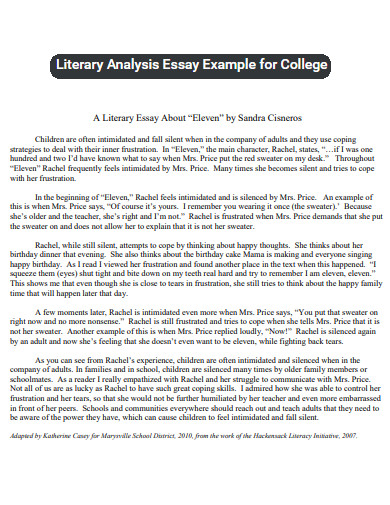

Examples of Literary Analysis Essay

Examples are great to understand any concept, especially if it is related to writing. Below are some great literary analysis essay examples that showcase how this type of essay is written.

A ROSE FOR EMILY LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY

TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY

THE GREAT GATSBY LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY

THE YELLOW WALLPAPER LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY

If you do not have experience in writing essays, this will be a very chaotic process for you. In that case, it is very important for you to conduct good research on the topic before writing.

There are two important points that you should keep in mind when writing a literary analysis essay.

First, remember that it is very important to select a topic in which you are interested. Choose something that really inspires you. This will help you to catch the attention of a reader.

The selected topic should reflect the main idea of writing. In addition to that, it should also express your point of view as well.

Another important thing is to draft a good outline for your literary analysis essay. It will help you to define a central point and division of this into parts for further discussion.

Literary Analysis Essay Topics

Literary analysis essays are mostly based on artistic works like books, movies, paintings, and other forms of art. However, generally, students choose novels and books to write their literary essays.

Some cool, fresh, and good topics and ideas are listed below:

- Role of the Three Witches in flaming Macbeth’s ambition.

- Analyze the themes of the Play Antigone,

- Discuss Ajax as a tragic hero.

- The Judgement of Paris: Analyze the Reasons and their Consequences.

- Oedipus Rex: A Doomed Son or a Conqueror?

- Describe the Oedipus complex and Electra complex in relation to their respective myths.

- Betrayal is a common theme of Shakespearean tragedies. Discuss

- Identify and analyze the traits of history in T.S Eliot’s ‘Gerontion’.

- Analyze the theme of identity crisis in The Great Gatsby.

- Analyze the writing style of Emily Dickinson.

If you are still in doubt then there is nothing bad in getting professional writers’ help.

We at 5StarEssays.com can help you get a custom paper as per your specified requirements with our do essay for me service.

Our essay writers will help you write outstanding literary essays or any other type of essay. Such as compare and contrast essays, descriptive essays, rhetorical essays. We cover all of these.

So don’t waste your time browsing the internet and place your order now to get your well-written custom paper.

Frequently Asked Questions

What should a literary analysis essay include.

A good literary analysis essay must include a proper and in-depth explanation of your ideas. They must be backed with examples and evidence from the text. Textual evidence includes summaries, paraphrased text, original work details, and direct quotes.

What are the 4 components of literary analysis?

Here are the 4 essential parts of a literary analysis essay;

No literary work is explained properly without discussing and explaining these 4 things.

How do you start a literary analysis essay?

Start your literary analysis essay with the name of the work and the title. Hook your readers by introducing the main ideas that you will discuss in your essay and engage them from the start.

How do you do a literary analysis?

In a literary analysis essay, you study the text closely, understand and interpret its meanings. And try to find out the reasons behind why the author has used certain symbols, themes, and objects in the work.

Why is literary analysis important?

It encourages the students to think beyond their existing knowledge, experiences, and belief and build empathy. This helps in improving the writing skills also.

What is the fundamental characteristic of a literary analysis essay?

Interpretation is the fundamental and important feature of a literary analysis essay. The essay is based on how well the writer explains and interprets the work.

Law, Finance Essay

Cordon. is a published author and writing specialist. He has worked in the publishing industry for many years, providing writing services and digital content. His own writing career began with a focus on literature and linguistics, which he continues to pursue. Cordon is an engaging and professional individual, always looking to help others achieve their goals.

Was This Blog Helpful?

Keep reading.

- Interesting Literary Analysis Essay Topics for Students

- Write a Perfect Literary Analysis Essay Outline

People Also Read

- debate topics

- critical essay writing

- how to write an expository essay

- writing case study

- synthesis essay topics

Burdened With Assignments?

Advertisement

- Homework Services: Essay Topics Generator

© 2024 - All rights reserved

beginner's guide to literary analysis

Understanding literature & how to write literary analysis.

Literary analysis is the foundation of every college and high school English class. Once you can comprehend written work and respond to it, the next step is to learn how to think critically and complexly about a work of literature in order to analyze its elements and establish ideas about its meaning.

If that sounds daunting, it shouldn’t. Literary analysis is really just a way of thinking creatively about what you read. The practice takes you beyond the storyline and into the motives behind it.

While an author might have had a specific intention when they wrote their book, there’s still no right or wrong way to analyze a literary text—just your way. You can use literary theories, which act as “lenses” through which you can view a text. Or you can use your own creativity and critical thinking to identify a literary device or pattern in a text and weave that insight into your own argument about the text’s underlying meaning.

Now, if that sounds fun, it should , because it is. Here, we’ll lay the groundwork for performing literary analysis, including when writing analytical essays, to help you read books like a critic.

What Is Literary Analysis?

As the name suggests, literary analysis is an analysis of a work, whether that’s a novel, play, short story, or poem. Any analysis requires breaking the content into its component parts and then examining how those parts operate independently and as a whole. In literary analysis, those parts can be different devices and elements—such as plot, setting, themes, symbols, etcetera—as well as elements of style, like point of view or tone.

When performing analysis, you consider some of these different elements of the text and then form an argument for why the author chose to use them. You can do so while reading and during class discussion, but it’s particularly important when writing essays.

Literary analysis is notably distinct from summary. When you write a summary , you efficiently describe the work’s main ideas or plot points in order to establish an overview of the work. While you might use elements of summary when writing analysis, you should do so minimally. You can reference a plot line to make a point, but it should be done so quickly so you can focus on why that plot line matters . In summary (see what we did there?), a summary focuses on the “ what ” of a text, while analysis turns attention to the “ how ” and “ why .”

While literary analysis can be broad, covering themes across an entire work, it can also be very specific, and sometimes the best analysis is just that. Literary critics have written thousands of words about the meaning of an author’s single word choice; while you might not want to be quite that particular, there’s a lot to be said for digging deep in literary analysis, rather than wide.

Although you’re forming your own argument about the work, it’s not your opinion . You should avoid passing judgment on the piece and instead objectively consider what the author intended, how they went about executing it, and whether or not they were successful in doing so. Literary criticism is similar to literary analysis, but it is different in that it does pass judgement on the work. Criticism can also consider literature more broadly, without focusing on a singular work.

Once you understand what constitutes (and doesn’t constitute) literary analysis, it’s easy to identify it. Here are some examples of literary analysis and its oft-confused counterparts:

Summary: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” the narrator visits his friend Roderick Usher and witnesses his sister escape a horrible fate.

Opinion: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Poe uses his great Gothic writing to establish a sense of spookiness that is enjoyable to read.

Literary Analysis: “Throughout ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ Poe foreshadows the fate of Madeline by creating a sense of claustrophobia for the reader through symbols, such as in the narrator’s inability to leave and the labyrinthine nature of the house.

In summary, literary analysis is:

- Breaking a work into its components

- Identifying what those components are and how they work in the text

- Developing an understanding of how they work together to achieve a goal

- Not an opinion, but subjective

- Not a summary, though summary can be used in passing

- Best when it deeply, rather than broadly, analyzes a literary element

Literary Analysis and Other Works

As discussed above, literary analysis is often performed upon a single work—but it doesn’t have to be. It can also be performed across works to consider the interplay of two or more texts. Regardless of whether or not the works were written about the same thing, or even within the same time period, they can have an influence on one another or a connection that’s worth exploring. And reading two or more texts side by side can help you to develop insights through comparison and contrast.

For example, Paradise Lost is an epic poem written in the 17th century, based largely on biblical narratives written some 700 years before and which later influenced 19th century poet John Keats. The interplay of works can be obvious, as here, or entirely the inspiration of the analyst. As an example of the latter, you could compare and contrast the writing styles of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edgar Allan Poe who, while contemporaries in terms of time, were vastly different in their content.

Additionally, literary analysis can be performed between a work and its context. Authors are often speaking to the larger context of their times, be that social, political, religious, economic, or artistic. A valid and interesting form is to compare the author’s context to the work, which is done by identifying and analyzing elements that are used to make an argument about the writer’s time or experience.

For example, you could write an essay about how Hemingway’s struggles with mental health and paranoia influenced his later work, or how his involvement in the Spanish Civil War influenced his early work. One approach focuses more on his personal experience, while the other turns to the context of his times—both are valid.

Why Does Literary Analysis Matter?

Sometimes an author wrote a work of literature strictly for entertainment’s sake, but more often than not, they meant something more. Whether that was a missive on world peace, commentary about femininity, or an allusion to their experience as an only child, the author probably wrote their work for a reason, and understanding that reason—or the many reasons—can actually make reading a lot more meaningful.

Performing literary analysis as a form of study unquestionably makes you a better reader. It’s also likely that it will improve other skills, too, like critical thinking, creativity, debate, and reasoning.

At its grandest and most idealistic, literary analysis even has the ability to make the world a better place. By reading and analyzing works of literature, you are able to more fully comprehend the perspectives of others. Cumulatively, you’ll broaden your own perspectives and contribute more effectively to the things that matter to you.

Literary Terms to Know for Literary Analysis

There are hundreds of literary devices you could consider during your literary analysis, but there are some key tools most writers utilize to achieve their purpose—and therefore you need to know in order to understand that purpose. These common devices include:

- Characters: The people (or entities) who play roles in the work. The protagonist is the main character in the work.

- Conflict: The conflict is the driving force behind the plot, the event that causes action in the narrative, usually on the part of the protagonist

- Context : The broader circumstances surrounding the work political and social climate in which it was written or the experience of the author. It can also refer to internal context, and the details presented by the narrator

- Diction : The word choice used by the narrator or characters

- Genre: A category of literature characterized by agreed upon similarities in the works, such as subject matter and tone

- Imagery : The descriptive or figurative language used to paint a picture in the reader’s mind so they can picture the story’s plot, characters, and setting

- Metaphor: A figure of speech that uses comparison between two unlike objects for dramatic or poetic effect

- Narrator: The person who tells the story. Sometimes they are a character within the story, but sometimes they are omniscient and removed from the plot.

- Plot : The storyline of the work

- Point of view: The perspective taken by the narrator, which skews the perspective of the reader

- Setting : The time and place in which the story takes place. This can include elements like the time period, weather, time of year or day, and social or economic conditions

- Symbol : An object, person, or place that represents an abstract idea that is greater than its literal meaning

- Syntax : The structure of a sentence, either narration or dialogue, and the tone it implies

- Theme : A recurring subject or message within the work, often commentary on larger societal or cultural ideas

- Tone : The feeling, attitude, or mood the text presents

How to Perform Literary Analysis

Step 1: read the text thoroughly.

Literary analysis begins with the literature itself, which means performing a close reading of the text. As you read, you should focus on the work. That means putting away distractions (sorry, smartphone) and dedicating a period of time to the task at hand.

It’s also important that you don’t skim or speed read. While those are helpful skills, they don’t apply to literary analysis—or at least not this stage.

Step 2: Take Notes as You Read

As you read the work, take notes about different literary elements and devices that stand out to you. Whether you highlight or underline in text, use sticky note tabs to mark pages and passages, or handwrite your thoughts in a notebook, you should capture your thoughts and the parts of the text to which they correspond. This—the act of noticing things about a literary work—is literary analysis.

Step 3: Notice Patterns

As you read the work, you’ll begin to notice patterns in the way the author deploys language, themes, and symbols to build their plot and characters. As you read and these patterns take shape, begin to consider what they could mean and how they might fit together.

As you identify these patterns, as well as other elements that catch your interest, be sure to record them in your notes or text. Some examples include:

- Circle or underline words or terms that you notice the author uses frequently, whether those are nouns (like “eyes” or “road”) or adjectives (like “yellow” or “lush”).

- Highlight phrases that give you the same kind of feeling. For example, if the narrator describes an “overcast sky,” a “dreary morning,” and a “dark, quiet room,” the words aren’t the same, but the feeling they impart and setting they develop are similar.

- Underline quotes or prose that define a character’s personality or their role in the text.

- Use sticky tabs to color code different elements of the text, such as specific settings or a shift in the point of view.

By noting these patterns, comprehensive symbols, metaphors, and ideas will begin to come into focus.

Step 4: Consider the Work as a Whole, and Ask Questions

This is a step that you can do either as you read, or after you finish the text. The point is to begin to identify the aspects of the work that most interest you, and you could therefore analyze in writing or discussion.

Questions you could ask yourself include:

- What aspects of the text do I not understand?

- What parts of the narrative or writing struck me most?

- What patterns did I notice?

- What did the author accomplish really well?

- What did I find lacking?

- Did I notice any contradictions or anything that felt out of place?

- What was the purpose of the minor characters?

- What tone did the author choose, and why?

The answers to these and more questions will lead you to your arguments about the text.

Step 5: Return to Your Notes and the Text for Evidence

As you identify the argument you want to make (especially if you’re preparing for an essay), return to your notes to see if you already have supporting evidence for your argument. That’s why it’s so important to take notes or mark passages as you read—you’ll thank yourself later!

If you’re preparing to write an essay, you’ll use these passages and ideas to bolster your argument—aka, your thesis. There will likely be multiple different passages you can use to strengthen multiple different aspects of your argument. Just be sure to cite the text correctly!

If you’re preparing for class, your notes will also be invaluable. When your teacher or professor leads the conversation in the direction of your ideas or arguments, you’ll be able to not only proffer that idea but back it up with textual evidence. That’s an A+ in class participation.

Step 6: Connect These Ideas Across the Narrative

Whether you’re in class or writing an essay, literary analysis isn’t complete until you’ve considered the way these ideas interact and contribute to the work as a whole. You can find and present evidence, but you still have to explain how those elements work together and make up your argument.

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay

When conducting literary analysis while reading a text or discussing it in class, you can pivot easily from one argument to another (or even switch sides if a classmate or teacher makes a compelling enough argument).

But when writing literary analysis, your objective is to propose a specific, arguable thesis and convincingly defend it. In order to do so, you need to fortify your argument with evidence from the text (and perhaps secondary sources) and an authoritative tone.

A successful literary analysis essay depends equally on a thoughtful thesis, supportive analysis, and presenting these elements masterfully. We’ll review how to accomplish these objectives below.

Step 1: Read the Text. Maybe Read It Again.

Constructing an astute analytical essay requires a thorough knowledge of the text. As you read, be sure to note any passages, quotes, or ideas that stand out. These could serve as the future foundation of your thesis statement. Noting these sections now will help you when you need to gather evidence.

The more familiar you become with the text, the better (and easier!) your essay will be. Familiarity with the text allows you to speak (or in this case, write) to it confidently. If you only skim the book, your lack of rich understanding will be evident in your essay. Alternatively, if you read the text closely—especially if you read it more than once, or at least carefully revisit important passages—your own writing will be filled with insight that goes beyond a basic understanding of the storyline.

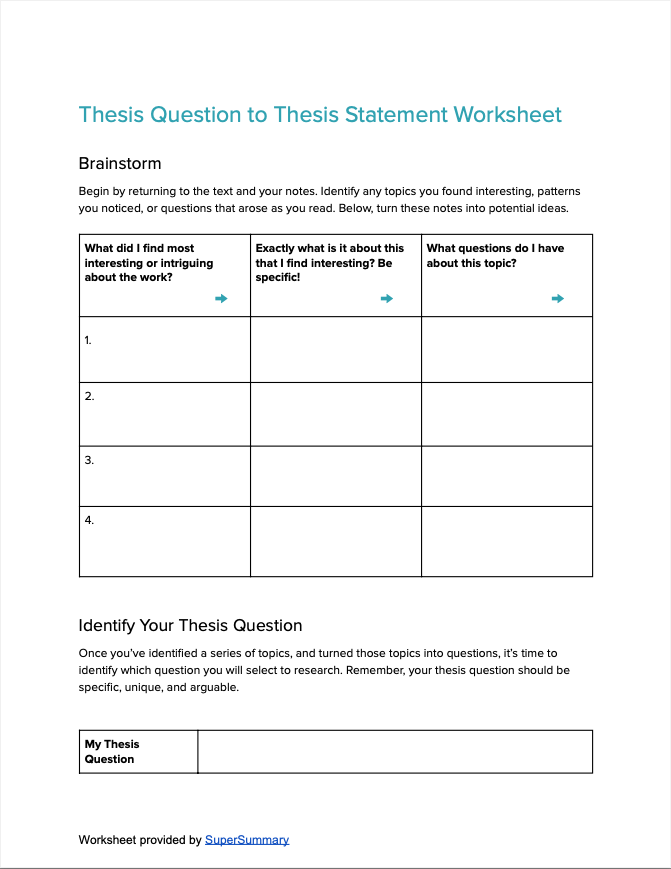

Step 2: Brainstorm Potential Topics

Because you took detailed notes while reading the text, you should have a list of potential topics at the ready. Take time to review your notes, highlighting any ideas or questions you had that feel interesting. You should also return to the text and look for any passages that stand out to you.

When considering potential topics, you should prioritize ideas that you find interesting. It won’t only make the whole process of writing an essay more fun, your enthusiasm for the topic will probably improve the quality of your argument, and maybe even your writing. Just like it’s obvious when a topic interests you in a conversation, it’s obvious when a topic interests the writer of an essay (and even more obvious when it doesn’t).

Your topic ideas should also be specific, unique, and arguable. A good way to think of topics is that they’re the answer to fairly specific questions. As you begin to brainstorm, first think of questions you have about the text. Questions might focus on the plot, such as: Why did the author choose to deviate from the projected storyline? Or why did a character’s role in the narrative shift? Questions might also consider the use of a literary device, such as: Why does the narrator frequently repeat a phrase or comment on a symbol? Or why did the author choose to switch points of view each chapter?

Once you have a thesis question , you can begin brainstorming answers—aka, potential thesis statements . At this point, your answers can be fairly broad. Once you land on a question-statement combination that feels right, you’ll then look for evidence in the text that supports your answer (and helps you define and narrow your thesis statement).

For example, after reading “ The Fall of the House of Usher ,” you might be wondering, Why are Roderick and Madeline twins?, Or even: Why does their relationship feel so creepy?” Maybe you noticed (and noted) that the narrator was surprised to find out they were twins, or perhaps you found that the narrator’s tone tended to shift and become more anxious when discussing the interactions of the twins.

Once you come up with your thesis question, you can identify a broad answer, which will become the basis for your thesis statement. In response to the questions above, your answer might be, “Poe emphasizes the close relationship of Roderick and Madeline to foreshadow that their deaths will be close, too.”

Step 3: Gather Evidence

Once you have your topic (or you’ve narrowed it down to two or three), return to the text (yes, again) to see what evidence you can find to support it. If you’re thinking of writing about the relationship between Roderick and Madeline in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” look for instances where they engaged in the text.

This is when your knowledge of literary devices comes in clutch. Carefully study the language around each event in the text that might be relevant to your topic. How does Poe’s diction or syntax change during the interactions of the siblings? How does the setting reflect or contribute to their relationship? What imagery or symbols appear when Roderick and Madeline are together?

By finding and studying evidence within the text, you’ll strengthen your topic argument—or, just as valuably, discount the topics that aren’t strong enough for analysis.

Step 4: Consider Secondary Sources

In addition to returning to the literary work you’re studying for evidence, you can also consider secondary sources that reference or speak to the work. These can be articles from journals you find on JSTOR, books that consider the work or its context, or articles your teacher shared in class.

While you can use these secondary sources to further support your idea, you should not overuse them. Make sure your topic remains entirely differentiated from that presented in the source.

Step 5: Write a Working Thesis Statement

Once you’ve gathered evidence and narrowed down your topic, you’re ready to refine that topic into a thesis statement. As you continue to outline and write your paper, this thesis statement will likely change slightly, but this initial draft will serve as the foundation of your essay. It’s like your north star: Everything you write in your essay is leading you back to your thesis.

Writing a great thesis statement requires some real finesse. A successful thesis statement is:

- Debatable : You shouldn’t simply summarize or make an obvious statement about the work. Instead, your thesis statement should take a stand on an issue or make a claim that is open to argument. You’ll spend your essay debating—and proving—your argument.

- Demonstrable : You need to be able to prove, through evidence, that your thesis statement is true. That means you have to have passages from the text and correlative analysis ready to convince the reader that you’re right.

- Specific : In most cases, successfully addressing a theme that encompasses a work in its entirety would require a book-length essay. Instead, identify a thesis statement that addresses specific elements of the work, such as a relationship between characters, a repeating symbol, a key setting, or even something really specific like the speaking style of a character.

Example: By depicting the relationship between Roderick and Madeline to be stifling and almost otherworldly in its closeness, Poe foreshadows both Madeline’s fate and Roderick’s inability to choose a different fate for himself.

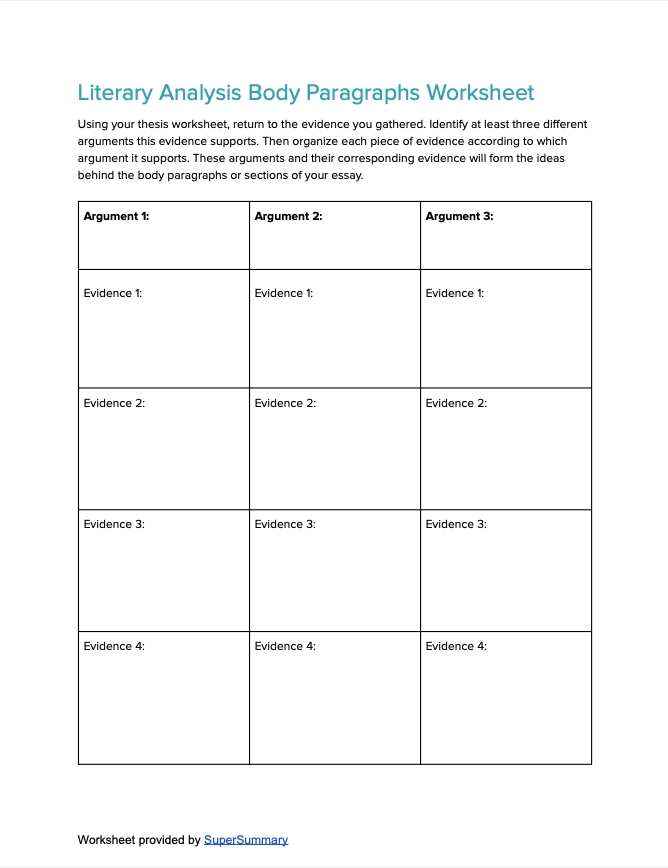

Step 6: Write an Outline

You have your thesis, you have your evidence—but how do you put them together? A great thesis statement (and therefore a great essay) will have multiple arguments supporting it, presenting different kinds of evidence that all contribute to the singular, main idea presented in your thesis.

Review your evidence and identify these different arguments, then organize the evidence into categories based on the argument they support. These ideas and evidence will become the body paragraphs of your essay.

For example, if you were writing about Roderick and Madeline as in the example above, you would pull evidence from the text, such as the narrator’s realization of their relationship as twins; examples where the narrator’s tone of voice shifts when discussing their relationship; imagery, like the sounds Roderick hears as Madeline tries to escape; and Poe’s tendency to use doubles and twins in his other writings to create the same spooky effect. All of these are separate strains of the same argument, and can be clearly organized into sections of an outline.

Step 7: Write Your Introduction

Your introduction serves a few very important purposes that essentially set the scene for the reader:

- Establish context. Sure, your reader has probably read the work. But you still want to remind them of the scene, characters, or elements you’ll be discussing.

- Present your thesis statement. Your thesis statement is the backbone of your analytical paper. You need to present it clearly at the outset so that the reader understands what every argument you make is aimed at.

- Offer a mini-outline. While you don’t want to show all your cards just yet, you do want to preview some of the evidence you’ll be using to support your thesis so that the reader has a roadmap of where they’re going.

Step 8: Write Your Body Paragraphs

Thanks to steps one through seven, you’ve already set yourself up for success. You have clearly outlined arguments and evidence to support them. Now it’s time to translate those into authoritative and confident prose.

When presenting each idea, begin with a topic sentence that encapsulates the argument you’re about to make (sort of like a mini-thesis statement). Then present your evidence and explanations of that evidence that contribute to that argument. Present enough material to prove your point, but don’t feel like you necessarily have to point out every single instance in the text where this element takes place. For example, if you’re highlighting a symbol that repeats throughout the narrative, choose two or three passages where it is used most effectively, rather than trying to squeeze in all ten times it appears.

While you should have clearly defined arguments, the essay should still move logically and fluidly from one argument to the next. Try to avoid choppy paragraphs that feel disjointed; every idea and argument should feel connected to the last, and, as a group, connected to your thesis. A great way to connect the ideas from one paragraph to the next is with transition words and phrases, such as:

- Furthermore

- In addition

- On the other hand

- Conversely

Step 9: Write Your Conclusion

Your conclusion is more than a summary of your essay's parts, but it’s also not a place to present brand new ideas not already discussed in your essay. Instead, your conclusion should return to your thesis (without repeating it verbatim) and point to why this all matters. If writing about the siblings in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” for example, you could point out that the utilization of twins and doubles is a common literary element of Poe’s work that contributes to the definitive eeriness of Gothic literature.

While you might speak to larger ideas in your conclusion, be wary of getting too macro. Your conclusion should still be supported by all of the ideas that preceded it.

Step 10: Revise, Revise, Revise

Of course you should proofread your literary analysis essay before you turn it in. But you should also edit the content to make sure every piece of evidence and every explanation directly supports your thesis as effectively and efficiently as possible.

Sometimes, this might mean actually adapting your thesis a bit to the rest of your essay. At other times, it means removing redundant examples or paraphrasing quotations. Make sure every sentence is valuable, and remove those that aren’t.

Other Resources for Literary Analysis

With these skills and suggestions, you’re well on your way to practicing and writing literary analysis. But if you don’t have a firm grasp on the concepts discussed above—such as literary devices or even the content of the text you’re analyzing—it will still feel difficult to produce insightful analysis.

If you’d like to sharpen the tools in your literature toolbox, there are plenty of other resources to help you do so:

- Check out our expansive library of Literary Devices . These could provide you with a deeper understanding of the basic devices discussed above or introduce you to new concepts sure to impress your professors ( anagnorisis , anyone?).

- This Academic Citation Resource Guide ensures you properly cite any work you reference in your analytical essay.

- Our English Homework Help Guide will point you to dozens of resources that can help you perform analysis, from critical reading strategies to poetry helpers.

- This Grammar Education Resource Guide will direct you to plenty of resources to refine your grammar and writing (definitely important for getting an A+ on that paper).

Of course, you should know the text inside and out before you begin writing your analysis. In order to develop a true understanding of the work, read through its corresponding SuperSummary study guide . Doing so will help you truly comprehend the plot, as well as provide some inspirational ideas for your analysis.

Writing A Literary Analysis Essay

- Library Resources

- Books & EBooks

- What is an Literary Analysis?

- Literary Devices & Terms

- Creating a Thesis Statement This link opens in a new window

- Using quotes or evidence in your essay

- APA Format This link opens in a new window

- MLA Format This link opens in a new window

- OER Resources

- Copyright, Plagiarism, and Fair Use

Video Links

Elements of a short story, Part 1

YouTube video

Elements of a short story, Part 2

online tools

Collaborative Mind Mapping – collaborative brainstorming site

Sample Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Paper Format and Structure

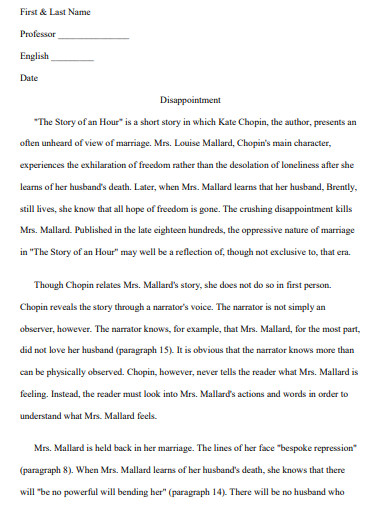

Analyzing Literature and writing a Literary Analysis

Literary Analysis are written in the third person point of view in present tense. Do not use the words I or you in the essay. Your instructor may have you choose from a list of literary works read in class or you can choose your own. Follow the required formatting and instructions of your instructor.

Writing & Analyzing process

First step: Choose a literary work or text. Read & Re-Read the text or short story. Determine the key point or purpose of the literature

Step two: Analyze key elements of the literary work. Determine how they fit in with the author's purpose.

Step three: Put all information together. Determine how all elements fit together towards the main theme of the literary work.

Step four: Brainstorm a list of potential topics. Create a thesis statement based on your analysis of the literary work.

Step five: search through the text or short story to find textual evidence to support your thesis. Gather information from different but relevant sources both from the text itself and other secondary sources to help to prove your point. All evidence found will be quoted and analyzed throughout your essay to help explain your argument to the reader.

Step six: Create and outline and begin the rough draft of your essay.

Step seven: revise and proofread. Write the final draft of essay

Step eight: include a reference or works cited page at the end of the essay and include in-text citations.

When analyzing a literary work pay close attention to the following:

Characters: A character is a person, animal, being, creature, or thing in a story.

- Protagonist : The main character of the story

- Antagonist : The villain of the story

- Love interest : the protagonist’s object of desire.

- Confidant : This type of character is the best friend or sidekick of the protagonist

- Foil – A foil is a character that has opposite character traits from another character and are meant to help highlight or bring out another’s positive or negative side.

- Flat – A flat character has one or two main traits, usually only all positive or negative.

- Dynamic character : A dynamic character is one who changes over the course of the story.

- Round character : These characters have many different traits, good and bad, making them more interesting.

- Static character : A static character does not noticeably change over the course of a story.

- Symbolic character : A symbolic character represents a concept or theme larger than themselves.

- Stock character : A stock character is an ordinary character with a fixed set of personality traits.

Setting: The setting is the period of time and geographic location in which a story takes place.

Plot: a literary term used to describe the events that make up a story

Theme: a universal idea, lesson, or message explored throughout a work of literature.

Dialogue: any communication between two characters

Imagery: a literary device that refers to the use of figurative language to evoke a sensory experience or create a picture with words for a reader.

Figures of Speech: A word or phrase that is used in a non-literal way to create an effect.

Tone: A literary device that reflects the writer's attitude toward the subject matter or audience of a literary work.

rhyme or rhythm: Rhyme is a literary device, featured particularly in poetry, in which identical or similar concluding syllables in different words are repeated. Rhythm can be described as the beat and pace of a poem

Point of view: the narrative voice through which a story is told.

- Limited – the narrator sees only what’s in front of him/her, a spectator of events as they unfold and unable to read any other character’s mind.

- Omniscient – narrator sees all. He or she sees what each character is doing and can see into each character’s mind.

- Limited Omniscient – narrator can only see into one character’s mind. He/she might see other events happening, but only knows the reasons of one character’s actions in the story.

- First person: You see events based on the character telling the story

- Second person: The narrator is speaking to you as the audience

Symbolism: a literary device in which a writer uses one thing—usually a physical object or phenomenon—to represent something else.

Irony: a literary device in which contradictory statements or situations reveal a reality that is different from what appears to be true.

Ask some of the following questions when analyzing literary work:

- Which literary devices were used by the author?

- How are the characters developed in the content?

- How does the setting fit in with the mood of the literary work?

- Does a change in the setting affect the mood, characters, or conflict?

- What point of view is the literary work written in and how does it effect the plot, characters, setting, and over all theme of the work?

- What is the over all tone of the literary work? How does the tone impact the author’s message?

- How are figures of speech such as similes, metaphors, and hyperboles used throughout the text?

- When was the text written? how does the text fit in with the time period?

Creating an Outline

A literary analysis essay outline is written in standard format: introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. An outline will provide a definite structure for your essay.

I. Introduction: Title

A. a hook statement or sentence to draw in readers

B. Introduce your topic for the literary analysis.

- Include some background information that is relevant to the piece of literature you are aiming to analyze.

C. Thesis statement: what is your argument or claim for the literary work.

II. Body paragraph

A. first point for your analysis or evidence from thesis

B. textual evidence with explanation of how it proves your point

III. second evidence from thesis

A. textual evidence with explanation of how it proves your point

IV. third evidence from thesis

V. Conclusion

A. wrap up the essay

B. restate the argument and why its important

C. Don't add any new ideas or arguments

VI: Bibliography: Reference or works cited page

End each body paragraph in the essay with a transitional sentence.

Links & Resources

Literary Analysis Guide

Discusses how to analyze a passage of text to strengthen your discussion of the literature.

The Writing Center @ UNC-Chapel Hill

Excellent handouts and videos around key writing concepts. Entire section on Writing for Specific Fields, including Drama, Literature (Fiction), and more. Licensed under CC BY NC ND (Creative Commons - Attribution - NonCommercial - No Derivatives).

Creating Literary Analysis (Cordell and Pennington, 2012) – LibreTexts

Resources for Literary Analysis Writing

Some free resources on this site but some are subscription only

Students Teaching English Paper Strategies

The Internet Public Library: Literary Criticism

- << Previous: Literary Devices & Terms

- Next: Creating a Thesis Statement >>

- Last Updated: Jan 24, 2024 1:22 PM

- URL: https://wiregrass.libguides.com/c.php?g=1191536

Literary Analysis Essay

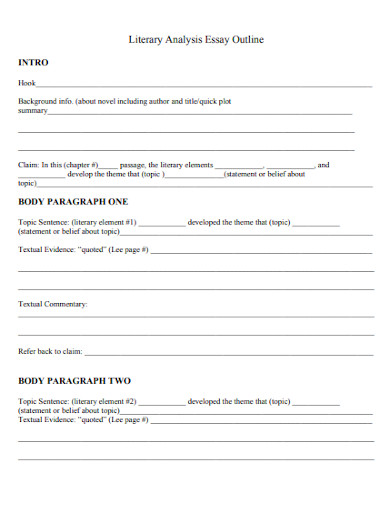

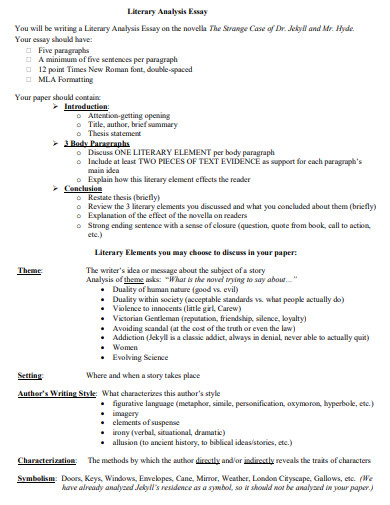

Literary Analysis Essay Outline

Literary Analysis Essay Outline Guide with Examples

Published on: Aug 22, 2020

Last updated on: Mar 25, 2024

People also read

Literary Analysis Essay - Step by Step Guide

Interesting Literary Analysis Essay Topics & Ideas

Share this article

Writing a literary analysis essay may seem intimidating at first, but we're here to simplify the process for you. In this guide, we'll walk you through the steps of creating an effective outline that will enhance your writing and analytical abilities.

Whether you're a seasoned student or new to literary analysis, mastering the art of outlining will help you organize your thoughts and express your ideas with clarity and precision.

Let's dive in!

On This Page On This Page -->

The Basics of Literary Analysis Writing

Before diving into the specifics of the outline, let's grasp the fundamental elements of a literary analysis essay .

At its core, this type of essay requires a thoughtful examination and interpretation of a literary work. Whether it's a novel, poem, or play, the aim is to analyze the author's choices and convey your insights to the reader.

The Significance of an Outline

An outline is important for two reasons: It helps you organize your ideas and allows readers to follow along easily.

Think of it as a map for your essay. Without structure, essays can be confusing. By using an outline, you ensure that your writing is clear and logical, keeping both you and your readers on track.

Literary Analysis Essay Format

Letâs take a look at the specific and detailed format and how to write a literary analysis essay outline in simple steps:

Outline Ideas for Literary Analysis Essay

Here are sample templates for each of the outlined ideas for a literary analysis essay:

Five Paragraph Essay

This format is a traditional structure for organizing essays and is often taught in schools. It consists of an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Each body paragraph focuses on one main point or argument.

MLA Formatted Graphic Organizer

This format is designed to help organize your ideas according to the Modern Language Association (MLA) formatting guidelines. It ensures that your essay is properly structured and formatted according to MLA standards.

Compare and Contrast Essay on Two Texts

This format compares and contrasts two texts, highlighting similarities and differences. This is a common method used to analyze literature. There are two common methods: point by point and block method.

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Literary Analysis Essay Examples Outline

Letâs take a look at the literary analysis essay outline examples in easily downloadable PDF format:

Literary Analysis Essay Outline Middle School

Literary Analysis Outline Graphic Organizer

Critical Analysis Essay Outline Example

Character Analysis Essay Outline

Literary Analysis Essay Topics

Here are some literary analysis essay topics you can take inspiration from:

- Analyze the corrupting influence of power in Shakespeare's "Macbeth."

- Explore the symbolism of the green light in "The Great Gatsby" and its connection to the American Dream.

- Examine Holden Caulfield's journey of self-discovery and identity in "The Catcher in the Rye."

- Understand the use of magical realism in "One Hundred Years of Solitude" and its reflection of Latin American culture.

- Unravel the impact of race, class, and social hierarchy on moral justice in "To Kill a Mockingbird."

- Investigate feminist themes and gender roles in "Jane Eyre": Independence, equality, and the quest for autonomy.

- Examine the theme of fate versus free will in Sophocles' "Oedipus Rex" and its tragic consequences.

- Analyze the allegorical critique of totalitarianism in George Orwell's "Animal Farm."

- Explore survival and resilience in "Life of Pi" through the protagonist's journey of faith and self-discovery.

- Understand existential themes in "The Stranger": Absurdity, alienation, and the search for meaning in an indifferent world.

Need more topic ideas? Check out our â literary analysis essay topics â blog and get unique ideas for your next assignment.

In conclusion, crafting a literary analysis essay outline is a critical step in the writing process. By breaking down the essay into manageable sections and organizing your thoughts effectively, you'll create a compelling and insightful analysis that engages your readers.

Remember, practice makes perfect, so don't hesitate to revise and refine your outline until it reflects your ideas cohesively.

In case you are running out of time you can reach out to our essay writing service. At CollegeEssay.org , we provide high-quality college essay writing help for various literary topics. We have an extensive and highly professional team of qualified writers who are available to work on your assignments 24/7.

Get in touch with our customer service representative and let them know all your requirements.

Also, do not forget to try our AI writing tool !

Barbara P (Literature, Marketing)

Barbara is a highly educated and qualified author with a Ph.D. in public health from an Ivy League university. She has spent a significant amount of time working in the medical field, conducting a thorough study on a variety of health issues. Her work has been published in several major publications.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Terms of Use

- Refunds & Cancellations

- Our Writers

- Success Stories

- Our Guarantees

- Affiliate Program

- Referral Program

- AI Essay Writer

Disclaimer: All client orders are completed by our team of highly qualified human writers. The essays and papers provided by us are not to be used for submission but rather as learning models only.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction

You’ve been assigned a literary analysis paper—what does that even mean? Is it like a book report that you used to write in high school? Well, not really.

A literary analysis essay asks you to make an original argument about a poem, play, or work of fiction and support that argument with research and evidence from your careful reading of the text.

It can take many forms, such as a close reading of a text, critiquing the text through a particular literary theory, comparing one text to another, or criticizing another critic’s interpretation of the text. While there are many ways to structure a literary essay, writing this kind of essay follows generally follows a similar process for everyone

Crafting a good literary analysis essay begins with good close reading of the text, in which you have kept notes and observations as you read. This will help you with the first step, which is selecting a topic to write about—what jumped out as you read, what are you genuinely interested in? The next step is to focus your topic, developing it into an argument—why is this subject or observation important? Why should your reader care about it as much as you do? The third step is to gather evidence to support your argument, for literary analysis, support comes in the form of evidence from the text and from your research on what other literary critics have said about your topic. Only after you have performed these steps, are you ready to begin actually writing your essay.

Writing a Literary Analysis Essay

How to create a topic and conduct research:.

Writing an Analysis of a Poem, Story, or Play

If you are taking a literature course, it is important that you know how to write an analysis—sometimes called an interpretation or a literary analysis or a critical reading or a critical analysis—of a story, a poem, and a play. Your instructor will probably assign such an analysis as part of the course assessment. On your mid-term or final exam, you might have to write an analysis of one or more of the poems and/or stories on your reading list. Or the dreaded “sight poem or story” might appear on an exam, a work that is not on the reading list, that you have not read before, but one your instructor includes on the exam to examine your ability to apply the active reading skills you have learned in class to produce, independently, an effective literary analysis.You might be asked to write instead or, or in addition to an analysis of a literary work, a more sophisticated essay in which you compare and contrast the protagonists of two stories, or the use of form and metaphor in two poems, or the tragic heroes in two plays.

You might learn some literary theory in your course and be asked to apply theory—feminist, Marxist, reader-response, psychoanalytic, new historicist, for example—to one or more of the works on your reading list. But the seminal assignment in a literature course is the analysis of the single poem, story, novel, or play, and, even if you do not have to complete this assignment specifically, it will form the basis of most of the other writing assignments you will be required to undertake in your literature class. There are several ways of structuring a literary analysis, and your instructor might issue specific instructions on how he or she wants this assignment done. The method presented here might not be identical to the one your instructor wants you to follow, but it will be easy enough to modify, if your instructor expects something a bit different, and it is a good default method, if your instructor does not issue more specific guidelines.You want to begin your analysis with a paragraph that provides the context of the work you are analyzing and a brief account of what you believe to be the poem or story or play’s main theme. At a minimum, your account of the work’s context will include the name of the author, the title of the work, its genre, and the date and place of publication. If there is an important biographical or historical context to the work, you should include that, as well.Try to express the work’s theme in one or two sentences. Theme, you will recall, is that insight into human experience the author offers to readers, usually revealed as the content, the drama, the plot of the poem, story, or play unfolds and the characters interact. Assessing theme can be a complex task. Authors usually show the theme; they don’t tell it. They rarely say, at the end of the story, words to this effect: “and the moral of my story is…” They tell their story, develop their characters, provide some kind of conflict—and from all of this theme emerges. Because identifying theme can be challenging and subjective, it is often a good idea to work through the rest of the analysis, then return to the beginning and assess theme in light of your analysis of the work’s other literary elements.Here is a good example of an introductory paragraph from Ben’s analysis of William Butler Yeats’ poem, “Among School Children.”

“Among School Children” was published in Yeats’ 1928 collection of poems The Tower. It was inspired by a visit Yeats made in 1926 to school in Waterford, an official visit in his capacity as a senator of the Irish Free State. In the course of the tour, Yeats reflects upon his own youth and the experiences that shaped the “sixty-year old, smiling public man” (line 8) he has become. Through his reflection, the theme of the poem emerges: a life has meaning when connections among apparently disparate experiences are forged into a unified whole.

In the body of your literature analysis, you want to guide your readers through a tour of the poem, story, or play, pausing along the way to comment on, analyze, interpret, and explain key incidents, descriptions, dialogue, symbols, the writer’s use of figurative language—any of the elements of literature that are relevant to a sound analysis of this particular work. Your main goal is to explain how the elements of literature work to elucidate, augment, and develop the theme. The elements of literature are common across genres: a story, a narrative poem, and a play all have a plot and characters. But certain genres privilege certain literary elements. In a poem, for example, form, imagery and metaphor might be especially important; in a story, setting and point-of-view might be more important than they are in a poem; in a play, dialogue, stage directions, lighting serve functions rarely relevant in the analysis of a story or poem.

The length of the body of an analysis of a literary work will usually depend upon the length of work being analyzed—the longer the work, the longer the analysis—though your instructor will likely establish a word limit for this assignment. Make certain that you do not simply paraphrase the plot of the story or play or the content of the poem. This is a common weakness in student literary analyses, especially when the analysis is of a poem or a play.

Here is a good example of two body paragraphs from Amelia’s analysis of “Araby” by James Joyce.

Within the story’s first few paragraphs occur several religious references which will accumulate as the story progresses. The narrator is a student at the Christian Brothers’ School; the former tenant of his house was a priest; he left behind books called The Abbot and The Devout Communicant. Near the end of the story’s second paragraph the narrator describes a “central apple tree” in the garden, under which is “the late tenant’s rusty bicycle pump.” We may begin to suspect the tree symbolizes the apple tree in the Garden of Eden and the bicycle pump, the snake which corrupted Eve, a stretch, perhaps, until Joyce’s fall-of-innocence theme becomes more apparent.

The narrator must continue to help his aunt with her errands, but, even when he is so occupied, his mind is on Mangan’s sister, as he tries to sort out his feelings for her. Here Joyce provides vivid insight into the mind of an adolescent boy at once elated and bewildered by his first crush. He wants to tell her of his “confused adoration,” but he does not know if he will ever have the chance. Joyce’s description of the pleasant tension consuming the narrator is conveyed in a striking simile, which continues to develop the narrator’s character, while echoing the religious imagery, so important to the story’s theme: “But my body was like a harp, and her words and gestures were like fingers, running along the wires.”

The concluding paragraph of your analysis should realize two goals. First, it should present your own opinion on the quality of the poem or story or play about which you have been writing. And, second, it should comment on the current relevance of the work. You should certainly comment on the enduring social relevance of the work you are explicating. You may comment, though you should never be obliged to do so, on the personal relevance of the work. Here is the concluding paragraph from Dao-Ming’s analysis of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest.

First performed in 1895, The Importance of Being Earnest has been made into a film, as recently as 2002 and is regularly revived by professional and amateur theatre companies. It endures not only because of the comic brilliance of its characters and their dialogue, but also because its satire still resonates with contemporary audiences. I am still amazed that I see in my own Asian mother a shadow of Lady Bracknell, with her obsession with finding for her daughter a husband who will maintain, if not, ideally, increase the family’s social status. We might like to think we are more liberated and socially sophisticated than our Victorian ancestors, but the starlets and eligible bachelors who star in current reality television programs illustrate the extent to which superficial concerns still influence decisions about love and even marriage. Even now, we can turn to Oscar Wilde to help us understand and laugh at those who are earnest in name only.

Dao-Ming’s conclusion is brief, but she does manage to praise the play, reaffirm its main theme, and explain its enduring appeal. And note how her last sentence cleverly establishes that sense of closure that is also a feature of an effective analysis.