- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Power of Healthy Relationships at Work

- Emma Seppälä

- Nicole K. McNichols

Five research-backed principles to cultivate stronger workplace relationships.

Research shows that leaders who prioritize relationships with their employees and lead from a place of positivity and kindness simply do better, and company culture has a bigger influence on employee well-being than salary and benefits. When it comes to cultivating happiness at work, it comes down to fostering positive relationships at work. Citing research from the field of social psychology, the authors outline five core principles that make all relationships, personal or professional, thrive: 1) transparency and authenticity, 2) inspiration, 3) emotional intelligence, 4) self-care, and 5) values.

Kushal Choksi was a successful Wall Street quant who had just entered the doors of the second twin tower on 9/11 when it got hit. As Choksi describes in his best-selling book, On a Wing and a Prayer , his brush with death was a wakeup call. Having mainly focused on wealth acquisition before 9/11, he began to question his approach to work.

- Emma Seppälä , PhD, is a faculty member at the Yale School of Management, faculty director of the Yale School of Management’s Women’s Leadership Program and bestselling author of SOVEREIGN (2024) and The Happiness Track (2017). She is also science director of Stanford University’s Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education . Follow her work at emmaseppala.com , http://www.iamsov.com or on Instagram . emmaseppala

- Nicole K. McNichols Ph.D. is an Associate Teaching Professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Washington where she teaches courses about sex and relationship science in addition to industrial and organizational psychology. Follow her work at www.nicolethesexprofessor.com and on Instagram .

Partner Center

The Importance of Positive Relationships in the Workplace

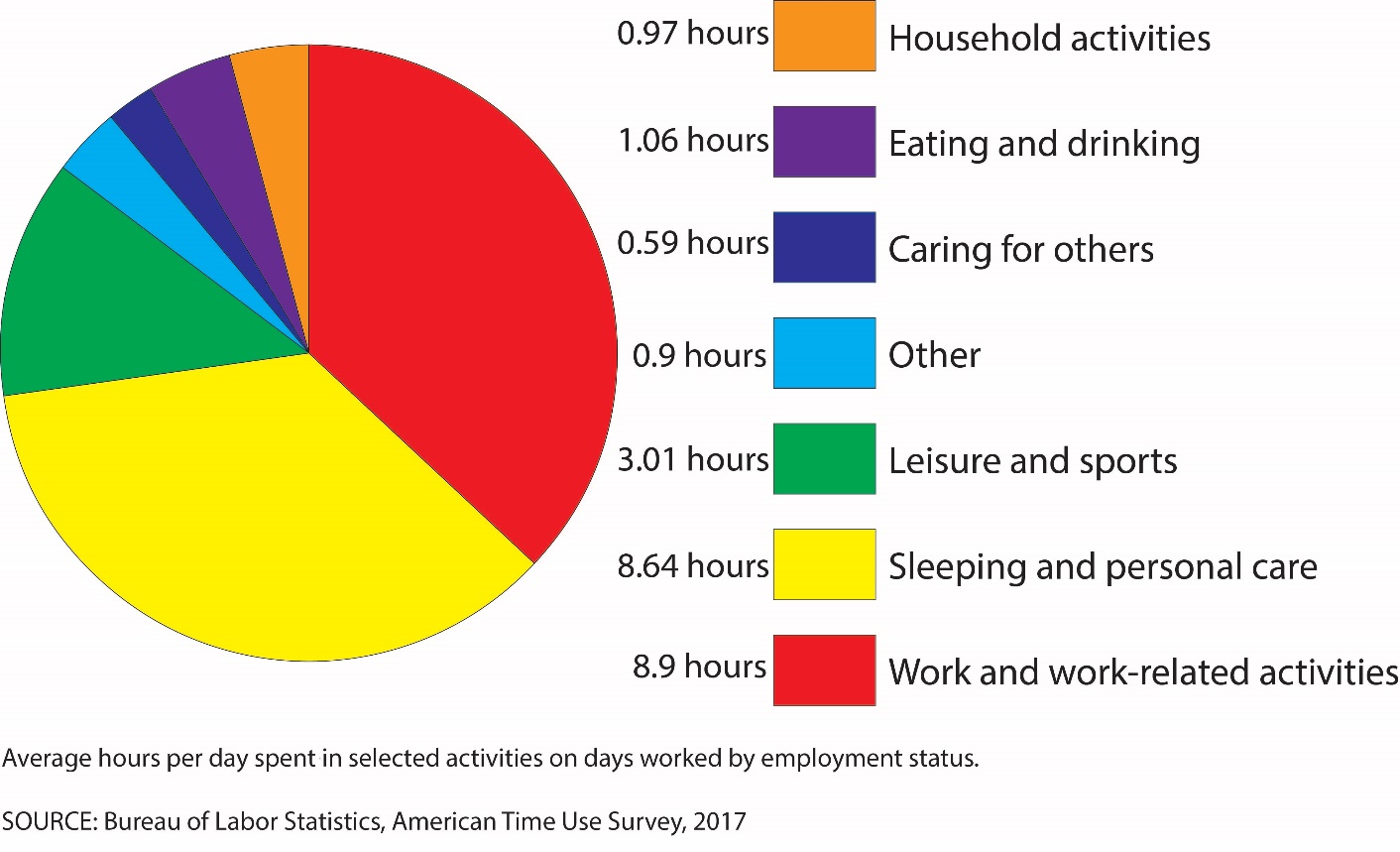

With lots of people spending more time at work than on any other daily activity, it is vital that individuals within any organization feel connected and supported by peers, subordinates, and leaders.

Psychosocial hazards related to the culture within an organization, such as poor interpersonal relations and a lack of policies and practices related to respect for workers, are significant contributors to workplace stress (Stoewen, 2016).

While prolonged exposure to these psychosocial hazards is related to increased psychiatric and physiological health problems, positive social relationships among employees are how work gets done.

Whether organizations and their employees flounder or flourish largely depends on the quality of the social relationships therein.

This article will take a look at the science behind positive relationships at work and the importance of positive social interactions, and discuss some of the ways positive employee interaction can be introduced and encouraged in the workplace.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Work & Career Coaching Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients identify opportunities for professional growth and create a more meaningful career.

This Article Contains:

The science behind positive relationships at work, what are the benefits of social interaction at work, why are positive interactions in the workplace so important, how to foster employee interaction in the workplace, a take-home message.

Psychologists have long identified the desire to feel connected to others as a basic human need, and interpersonal relationships have a significant impact on our mental health, health behavior, physical health, and mortality risk (Umberson & Montez, 2010). Our physiological systems are highly responsive to positive social interactions.

Gable and Gosnell (2011) surmised that humans are endowed with separate reflexive brain networks for social thinking. Close relationships are linked to health as they build certain biological systems that may protect against the adverse effects of stress. Their research found that in response to social contact, the brain releases oxytocin, a powerful hormone linked to trustworthiness and motivation to help others in the workplace.

Dunbar and Dunbar (1998) suggested that when individuals experience social pain in the workplace from feeling isolated, for instance, the region of the brain that is activated is the same as if physical pain had been experienced.

Conversely, when relationships in the workplace are characterized by cooperation, trust, and fairness, the reward center of the brain is activated, which encourages future interactions that promote employee trust, respect, and confidence, with employees believing the best in each other and inspiring each other in their performance (Geue, 2017).

Positive social interactions at work directly affect the body’s physiological processes. According to Heaphy and Dutton (2008), positive social interactions serve to bolster physiological resourcefulness by fortifying the cardiovascular, immune, and neuroendocrine systems through immediate and enduring decreases in cardiovascular reactivity, strengthened immune responses, and healthier hormonal patterns.

Put simply, when employees experience positive relationships, the body’s ability to build, maintain, and repair itself is improved both in and out of the workplace.

1. Employee engagement

Social interactions play an essential role in wellbeing, which, in turn, has a positive impact on employee engagement.

Organizations with higher levels of employee engagement indicated lower business costs, improved performance outcomes, lower staff turnover and absenteeism, and fewer safety incidents (Gallup, 2015).

2. Shared knowledge

Social interaction can lead to knowledge and productivity spillover from trained to untrained workers in collaborative team settings or between senior and junior workers, particularly in low-skilled tasks and occupations (Cornelissen, 2016).

For instance, Mas and Moretti (2009) found that productivity was improved when employees were assigned to work alongside faster, more knowledgeable coworkers.

3. Employee satisfaction

Employees who are satisfied with the overall quality of their workplace relationships are likely to be more attached to the organization.

Leaders who encourage informal interactions, such as after-hours social gatherings, can foster the development of more positive relationships and significantly influence and improve employee satisfaction (Sias, 2005).

4. Reduce health risks

A lack of social interaction in the workplace can have potentially negative consequences in relation to social support.

Several studies have indicated that the sense of isolation that comes from this lack of social support is associated with a host of negative health consequences, including a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, compromised immunity, increased risk of depression, and shortened lifespan (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015; Cacioppo, Hawkley, Norman, & Berntson, 2011; Mushtaq, Shoib, Shah, & Mushtaq, 2014).

5. Innovation

Strong within-group ties with coworkers (characterized by frequent social interactions) provide opportunities to facilitate innovative thinking.

According to Wang, Fang, Qureshi, and Janssen (2015), the strong ties developed by social interactions assist innovators in the search for inspiration, sponsorship, and support within the workplace.

6. Connection

Social interactions in the workplace help to ensure everyone in a group is on the same page. According to Sias, Krone, and Jablin (2002), peer relationships (also referred to as equivalent-status relationships) represent the most common type of employee interaction.

These peer relationships exist between coworkers with no formal authority over one another and act as an important source of informational and emotional support for employees. Coworkers who possess knowledge about and an understanding of their specific workplace experience are given opportunities to feel connected and included through the sharing of information through regular social interactions.

7. Positive feelings

Social interactions in the workplace have been found to increase self-reported positive feelings at the end of the workday (Nolan & Küpers, 2009).

Repeated positive social interactions cultivate greater shared experiences and the gradual development of more trusting relationships (Oh, Chung, & Labianca, 2004). When trust exists between team members, they are more likely to engage in positive, cooperative behavior, which in turn increases employee access to valuable resources.

9. Altruism

Employees who engage in positive social interactions also tend to exhibit more altruistic behaviors by providing coworkers with help, guidance, advice, and feedback on various work-related matters (Hamilton, 2007).

10. Team performance

The information collated through social interaction can help a team collectively improve its performance and the precision of its estimates (Jayles et al., 2017).

11. Improved motivation

Social interaction and positive relationships are important for various attitudinal, wellbeing, and performance-related outcomes. Basford and Offermann (2012) found that employees in both low- and high-status positions reported higher levels of motivation when interpersonal relationships with coworkers were good.

17 More Work & Career Coaching Exercises

These 17 Work & Career Coaching Exercises [PDF] contain everything you need to help others find more meaning and satisfaction in their work.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

As with any interpersonal relationship, those formed in the workplace reflect a varying and dynamic spectrum of quality.

At their very best, interactions can be a source of enrichment and vitality that helps and encourages individuals, groups, and organizations as a whole to thrive and flourish.

Conversely, negative workplace interactions have the potential to be a source of psychological distress, depletion, and dysfunction.

Positive social interactions are often referred to as appetitive. They are characterized by the pursuit of rewarding and desirable outcomes, while negative ones are aversive and commonly characterized by unwelcome and punishing results (Reis & Gable, 2003).

Positive interactions in the workplace have been shown to improve job satisfaction and positively influence staff turnover, as employees who experience support from colleagues are more likely to remain in an organization long term (Hodson, 2004; Moynihan & Pandey, 2008).

Furthermore, positive interactions between supportive coworkers who provide help and clarify tasks can improve an individual’s understanding of their role, thus reducing job role ambiguity and workload, which, according to Chiaburu and Harrison (2008), may ultimately increase job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Positive interactions in the workplace are marked by trust, mutual regard, and active engagement. According to Rosales (2016), interactions characterized in this way can improve employee awareness of others, foster positive emotions such as empathy and compassion, and increase the likelihood of trusting, respectful engagement between individuals.

In contrast, negative ties between two individuals at work are characterized by animosity, exclusion, or avoidance, which can cause stress and job dissatisfaction (Rosales, 2016).

This can, unsurprisingly, have a detrimental effect upon an employee’s emotional wellbeing; social relations at work that are disrespectful, distrustful, and lack reciprocity are independent predictors of medically diagnosed depression (Oksanen, Kouvonen, Vahtera, Virtanen, & Kivimäki, 2010).

Employees tend to be involved in many dyadic relationships within the workplace, with individuals generally possessing both negative and positive ties. However, when individuals have more negative associations with coworkers than positive, they might experience negative moods, emotions, and other adverse outcomes such as social ostracism (Venkataramani & Dalal, 2007).

Mastroianni and Storberg-Walker (2014) indicated that wellbeing is enhanced through work interactions when those interactions are trusting, collaborative, and positive, and when employees feel valued and respected. Interactions lacking these characteristics were found to detract from wellbeing and negatively impacted sleeping and eating patterns, socializing, exercise, personal relations, careers, and energy.

With the amount of time we spend at work, it is imperative that employees feel connected and supported through positive social relationships. Seligman (2011) noted that happiness could not be achieved without social relationships, and while social relationships do not guarantee happiness, happiness does not often occur without them (Diener & Seligman, 2002).

Such connections and interactions give energy to individuals and to the organization in which they work, whereas negative relationships may deplete energy and lead to individual and corporate floundering (Ragins & Dutton, 2007).

Given the organizational and personal benefits of positive workplace relationships, creating opportunities for and fostering positive social interactions should be a paramount objective for team leaders and managers.

According to the Society for Human Resource Management’s 2016 Employee Job Satisfaction and Employee Report , relationships with colleagues were the number one contributor to employee engagement, with 77% of respondents listing workplace connections as a priority.

It is therefore crucial that leaders and managers determine ways to promote positive workplace relationships. In doing so, organizations are better able to adopt a more relationship-centric outlook wherein the fostering of positive employee interactions becomes a goal in and of itself. According to Geue (2017), ‘elevating interactions’ is a critical requirement in creating a positive work environment.

In general, maximizing engagement levels can be boiled down to two key concepts: removing barriers that limit social interaction in the workplace and creating opportunities for employees to engage with each other. These outcomes can be achieved in several ways, and while not all approaches are suitable for all organizational types, the concepts hold true.

Promote face-to-face interaction

With the advent of digital communication, we’re now only ever a few clicks away from contact with virtually anyone anywhere in the world. While the internet has facilitated communication on a scale hereto unrivaled, there’s a lot to be said for traditional face-to-face interaction. An email might be easier, but we lose the nuances of nonverbal cues and tone.

For traditional workplaces, consider the layout of shared working environments. Is the layout of the office conducive to employee interaction? Considering the stereotypical ‘bull-pen’ office environment, literally removing the barriers between employees can open doors for social interaction opportunities.

Include remote workers

What about employees who work remotely? The upward trend in telecommuting is expected to continue over the coming years, with more employees working from home (or otherwise remotely), posing fresh challenges for the relationship-centric organization.

While organizations have been keen to reap the benefits of access to a broader talent pool and reduced office overheads, remote workers pose a challenge to the relationship-centric workplace.

Where in-person interaction isn’t feasible, face-to-face interaction can still be facilitated using social technology. Using video-conferencing software regularly can help to foster positive social relationships for remote workers.

Plan collaborative events

Dedicating time to specifically promoting positive social interactions in the workplace can be a powerful route to ensuring the relationship-centric approach doesn’t fall by the wayside amidst organizational pressure to achieve.

Set aside time for employees to interact; focus on interests and experiences out of work to direct attention to shared interests to allow for employees to discover commonalities and relatedness.

Effectively mediate conflict

Both employees and employers require meaningful relationships with others in the workplace, and yet these needs may be impeded by counterproductive and destructive workplace practices (Bolden & Gosling, 2006).

Organizational leaders should attempt to minimize negative interactions between employees by proactively mediating and resolving differences and building a culture of open communication that fosters trust and relationship building.

Lead by example

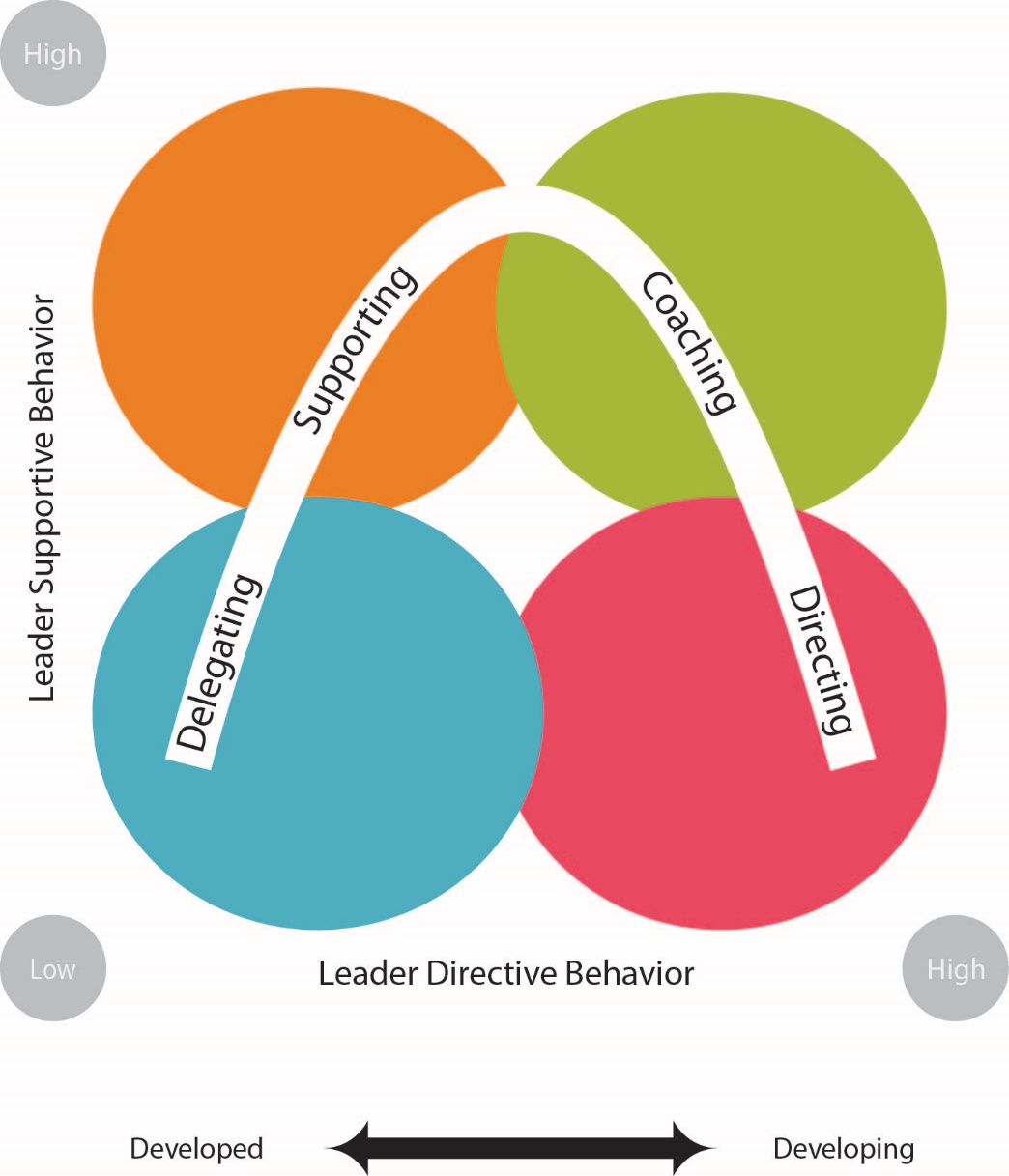

Creating a physical environment that nurtures positive social interactions between employees is a significant first step, but to promote relationships, a good team leader, supervisor, or manager should practice what they preach.

By establishing consistent patterns of behavior that exemplify the desired culture, you can promote an emotional environment of inclusivity and positivity.

Positive psychology founding father Martin Seligman’s (2011) PERMA model highlights five critical elements for mental wellbeing, which business leaders can adopt to promote a positive culture that encourages belonging.

The five elements of the PERMA model are:

- Positive emotion

- Positive relationships

- Achievement/accomplishment

Learn how to put the PERMA model into practice here .

The workplace is one of the few environments where people are ‘forced’ into relationships. By their very nature, workplace environments are made up of a blend of diverse groups of people, many of whom would have very little interest in freely meeting or socializing outside of the workplace. While a company’s greatest asset is its employees, those employees do not work together harmoniously all the time.

There are, however, actions that any individual or organization can take to encourage employee interaction and develop an inclusive workplace culture. Through the promotion of positive social interactions, workplace relationships can be a source of individual and collective growth, learning, and flourishing.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Work & Career Coaching Exercises for free .

- Basford, T. E., & Offermann, L. R. (2012). Beyond leadership: The impact of coworker relationships on employee motivation and intent to stay. Journal of Management & Organization , 8 , 807–817.

- Bolden, R., & Gosling, J. (2006). Leadership competencies. Leadership, 2 , 147–163.

- Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Norman, G. J., & Berntson, G.G. (2011). Social isolation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences , 1231 (1), 17–22.

- Chiaburu, D., & Harrison, D. A. (2008). Do peers make the place? Conceptual synthesis and meta-analysis of lateral social influences on perceptions, attitudes, OCBs, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology , 93 , 1082–1103.

- Cornelissen, T. (2016). Do social interactions in the workplace lead to productivity spillover among co-workers? IZA World of Labor , 314 , 1–10.

- Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science , 13 , 81–84.

- Dunbar, R., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (1998). Grooming, gossip, and the evolution of language . Harvard University Press.

- Gable, S. L., & Gosnell, C. L. (2011). The positive side of close relationships. In K. M. Sheldon, T. B., Kashdan, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Designing positive psychology: Taking stock and moving forward (pp. 265–279). Oxford University Press.

- Gallup. (2015). State of the global workforce [Report]. Retrieved from https://www.gallup.com/workplace/238079/state-global-workplace-2017.aspx

- Geue, P. E., (2017). Positive practices in the workplace: Impact on team climate, work engagement, and task performance. Emerging Leadership Journeys , 10 , 70–99.

- Hamilton, E. A. (2007). Firm friendship: Examining functions and outcomes of workplace friendship among law firm associates (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Boston College, Boston, MA.

- Heaphy, E. D., & Dutton, J. E. (2008). Positive social interactions and the human body at work: Linking organizations and physiology. Academy of Management Review, 33 , 137–162.

- Hodson, R. (2004). Work life and social fulfillment: Does social affiliation at work reflect a carrot or a stick? Social Science Quarterly , 85 , 221–239.

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness, and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Sciences , 10 (2), 227–237.

- Jayles, B., Kim, H-R., Escobedo, R., Cezera, S., Blanchet, A., Kameda, T., … Theraulaz, G. (2017). How social information can improve estimation accuracy in human groups. Proceedings of The National Academy of Sciences , 114 , 12620–12625.

- Mas, A., & Moretti, E. (2009). Peers at work. American Economic Review , 99 , 112−145.

- Mastroianni, K., & Storberg-Walker, J. (2014). Do work relationships matter? Characteristics of workplace interactions that enhance or detract from employee perceptions of well-being and health behaviors. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 2, 798–819.

- Moynihan, D. P., & Pandey, S. K. (2008). The ties that bind: Social networks, person-organization value fit, and turnover intention. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory , 18 , 205–227.

- Mushtaq, R., Shoib, S., Shah, T., & Mushtaq, S. (2014). Relationship between loneliness, psychiatric disorders, and physical health? A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research , 8 (9), WE01–04.

- Nolan, T. & Küpers, W. (2009). Organizational climate, organizational culture, and workplace relationships. In R. L. Morrison & S. L. Wright (Eds.), Friends and enemies in organizations (pp. 57–77). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Oh, H., Chung, M.-H., & Labianca, G. (2004), Group social capital and group effectiveness: the role of informal socializing ties. Academy of Management Journal, 47 , 860–875.

- Oksanen, T., Kouvonen, A., Vahtera, J., Virtanen, M., & Kivimäki, M. (2010). Prospective study of workplace social capital and depression: Are vertical and horizontal components equally important? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health , 64 (8), 684–689

- Ragins, B. R., & Dutton, J. E. (2007). Positive relationships at work: An introduction and invitation. In J. E. Dutton & B. R. Ragins (Eds.), Exploring positive relationships at work: Building a theoretical and research foundation (pp. 29–45). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Reis, H. T., & Gable, S. L. (2003). Toward a positive psychology of relationships. In C. L. Keyes & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: The positive person and the good life (pp. 129–159). American Psychological Association.

- Rosales, R. M. (2016). Energizing social interactions at work: An exploration of relationships that generate employee and organizational thriving. Open Journal of Social Sciences , 4 , 29–33.

- Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

- Sias, P. (2005). Workplace relationship quality and employee information experiences. Communication Studies, 56 , 375–395.

- Sias, P. M., Krone, K. J., & Jablin, F. M. (2002). An ecological systems perspective on workplace relationships. In M. L. Knapp & J. Daly (Eds.), Handbook of interpersonal communication (3rd ed.) (pp. 615–642). Sage.

- Society for Human Resource Management. (2016, April 18). 2016 Employee job satisfaction and engagement: Revitalizing a changing workforce. Retrieved from https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/trends-and-forecasting/research-and-surveys/pages/job-satisfaction-and-engagement-report-revitalizing-changing-workforce.aspx

- Stoewen D. L. (2016). Wellness at work: Building healthy workplaces. The Canadian Veterinary Journal, 57, 1188–1190.

- Umberson, D., & Montez, J. K. (2010). Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51 , S54–S66.

- Wang, X-H. F., Fang, Y., Qureshi, I., & Janssen, O. (2015). Understanding employee innovative behavior: Integrating the social network and leader-member exchange perspectives. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36 , 403-420.

- Venkataramani, V., & Dalal, R. (2007). Who helps and harms whom? Relational antecedents of interpersonal helping and harming in organizations. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92 , 952–966.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Thanks for this article

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Company Culture: How to Create a Flourishing Workplace

Company culture has become a buzzword, particularly in the post-COVID era, with more organizations recognizing the critical importance of a healthy workplace. During the Great [...]

Integrity in the Workplace (What It Is & Why It’s Important)

Integrity in the workplace matters. In fact, integrity is often viewed as one of the most important and highly sought-after characteristics of both employees and [...]

Neurodiversity in the Workplace: A Strengths-Based Approach

Promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in the workplace is a priority for ethical employers who want to optimize productivity and leverage the full potential [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (48)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (17)

- Positive Parenting (2)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (47)

- Resilience & Coping (35)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

Download 3 Free Work & Career Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Download 3 Work & Career Exercises Pack (PDF)

Work Life is Atlassian’s flagship publication dedicated to unleashing the potential of every team through real-life advice, inspiring stories, and thoughtful perspectives from leaders around the world.

Contributing Writer

Work Futurist

Senior Quantitative Researcher, People Insights

Principal Writer

Beyond the buzzwords: Why interpersonal skills matter at work

They’re so much more than resume fluff. Let’s give these “soft” skills the credit they deserve.

Get stories like this in your inbox

What makes somebody successful at work? It’s tempting to point to tangible qualities and accomplishments – things that are easily understood and quantified, like industry certifications, specific expertise, and lengthy experience.

No shade to technical skills – they’re certainly important. But let’s give some credit to their equally crucial yet often underappreciated counterpart: interpersonal skills (often called “soft skills”). These enigmatic abilities carry a lot of weight – depending on who you ask, up to 80% of career achievement is based on soft skills, rather than technical expertise.

Let’s stop dismissing interpersonal skills as touchy-feely traits or needless resume fluff and invest the energy to identify them, understand them, and perhaps most importantly, improve them.

What are interpersonal skills?

Break down the roots of the word and you’ll quickly get a solid understanding of the definition of interpersonal skills:

- Inter : Between or among

- Personal : Relating to a person

Interpersonal skills are often oversimplified to indicate that someone is “nice,” “friendly,” or “likable,” but that’s not accurate. Interpersonal skills aren’t about personality qualities – they’re specific behaviors and competencies that allow someone to work well with other people.

Interpersonal skills are the skills you use when working, communicating, and interacting with other people . These skills come to some people more naturally than others, with extroverts in particular excelling with interpersonal skills. But introverts shouldn’t count themselves out – these are still skills , so they can also be learned and practiced if you aren’t a natural.

8 examples of interpersonal skills

The broad meaning of interpersonal skills gives a basic understanding of how they’re different from technical capabilities (things like knowing a specific programming language or understanding project management methodologies).

But what do these soft skills actually look like in a work setting? There’s no definitive list of the most important interpersonal skills at work, as a lot of that will depend on your role, industry, and even company.

However, these eight interpersonal skills come up frequently and are applicable across a wide range of jobs and workplaces:

- Collaboration

- Communication

- Conflict resolution

- Emotional intelligence

- Negotiation

Benefits of interpersonal skills

Do you know your communication style at work? Take our quiz to find out

If the above list felt like nothing more than a list of buzzwords to beef up your LinkedIn profile or make it past an applicant tracking system, here are a few of the most notable benefits of investing your time, energy, and attention into your interpersonal skills:

- Build stronger relationships: Interpersonal skills allow you to connect and interact positively with other people. They allow you to understand other people’s emotions , communicate more effectively, establish more trust, and all-around foster more solid relationships. Those bonds fuel success at work, with research showing that leaders who prioritize relationships with employees do better – and as an added bonus, their employees do too.

- Set yourself apart: Interpersonal skills are always crucial, but especially when you’re on the job market. Data from LinkedIn states that 92% of talent professionals say soft skills are equally or more important to hire for than hard skills. Even in sectors like FinTech or healthcare that typically demand highly-specialized technical skills, the preference for hard skills was only 4% higher than the preference for soft skills. Developing your interpersonal capabilities helps you stand out in your job search – and in your existing workplace too.

- Improve your happiness (and performance): When you have an easier time relating to and interacting with the people you work with, you’ll help build a positive work environment not just for yourself, but for everyone. That positive helps you feel happier, be more engaged with your work, and even boosts your productivity .

How to improve your interpersonal skills

There are plenty of advantages to reap when you have solid soft skills, but then the question becomes: How do you get there? How do you build your interpersonal skills? It doesn’t feel as straightforward or measurable as mastering Photoshop or marketing analytics, but there are ways that you can improve your interpersonal skills – regardless of where you’re starting from.

1. Build your self-awareness

The Johari window: a fresh take on self-reflection

From conflict resolution to problem-solving, there are a ton of different and meaningful soft skills you could focus on. The key is to understand which ones will be the most impactful for you – and that starts with knowing what you lack.

Nobody wants to take a magnifying glass to their own shortcomings, but it’s essential to understand what you can improve about your interactions with others. You can get this information by:

- Completing a self-assessment like CliftonStrengths

- Participating in a team assessment like Johari Window

- Soliciting feedback from people you work closely with

- Reflecting on past interactions, projects, and performance reviews

Once you have a clearer direction about where you’re falling short (again, a little painful yet necessary), it’s time to think about interpersonal skills through a different filter: Which ones are most pertinent to your current role and your future career goals ?

Maybe you figure out that you aren’t the greatest networker. That’s not necessarily make-or-break as a software developer, but a much bigger deal if you’re in business development.

Think about your existing career as well as where you’d like to head in the future. That will help you pinpoint the soft skills that will make the most meaningful and immediate difference for you – rather than getting overwhelmed by trying to work on all of them at once.

2. Spend time with other people

You’re not going to become a better swimmer if you’re not in the water – and you’re not going to build your interpersonal skills if you’re not around other people.

While there are certainly things you can do independently to bolster your soft skills, you’ll get your most substantial education when you put yourself out there and interact with others. There are tons of ways you can do this at work, including:

- Volunteering for a cross-functional project

- Joining a company committee or employee resource group (ERG)

- Participating in company events and social outlets

Those give you an opportunity to learn more about where you excel and where you struggle interpersonally, as well as a chance to practice the skills you’re working on.

3. Find a mentor

The life-long learner’s guide to mentorship

If there’s someone you admire who shines in a specific area, consider asking them to take you under their wing in a mentorship capacity.

This doesn’t need to be anything formal – it can be as simple as asking your boss, who’s an ace negotiator, for some advice and resources. Or picking the brain of a colleague who always manages to get to the bottom of an issue.

Soaking in tips and experience from somebody skilled can be effective, but this might surprise you: You can get just as much benefit from mentoring someone yourself.

It’s another chance to interact closely with another person (which again, is crucial for bolstering your interpersonal skills) while simultaneously developing your own expertise through practice, repetition, and teaching. Research shows that both mentors and mentees improve their soft skills in a mentoring relationship.

4. Pursue formal training

Courses, articles, podcasts, books, webinars, interviews…there’s a practically endless buffet of educational resources out there for you to peruse.

When you’ve zoned in on a specific interpersonal skill you want to develop, it’s worth seeing what’s already out there that could support you on your journey. Here are a couple of ways you could get started:

- Search a platform like LinkedIn Learning or Coursera to see what formal courses exist for your chosen skill (read the reviews from other learners)

- Ask your colleagues to recommend resources they loved (you can even start a designated Slack channel to share with each other)

- Look for a coach that specializes in the skill you’re trying to advance

How to showcase your interpersonal skills

Here’s the tricky thing about interpersonal skills: You know them when you see them. They’re about actions, not words.

That makes them notoriously tough to tout when you need to – whether that’s on your resume, in a job interview, or in a self-evaluation when it’s time for your performance review.

So much of demonstrating your interpersonal skills is going to be about…well, demonstrating them. Ideally, you shouldn’t have to loudly broadcast them because you’ll embody them. This happens even in small ways. For example, during a job search, it could look like:

- Responding promptly and professionally to all messages from the hiring manager

- Showing up to interviews early and prepared

- Engaging in friendly small talk with anybody you interact with

But what about your pesky resume? How do you capture your soft skills there, without packing it full of bulleted buzzwords? Focus on results – not just what you did, but what you achieved . Make sure to quantify those results wherever you can too. For example, you could say:

- “Identified and resolved a bottleneck in the customer journey, reducing abandoned carts by 32% in one quarter” rather than listing “skilled problem-solver” in your key skills section

- “Collaborated closely with the sales, marketing, and human resources teams to plan a virtual career event that generated 85 new applications from qualified candidates” rather than “dedicated team player”

Soft skills, firm impact

It’s far too tempting to write off interpersonal skills as mushy-gushy, feel-good buzzwords – as if they’re nothing more than qualifications you use to fill up blank space on your resume.

In reality, though, these seemingly superfluous skills play a major role in achieving your career goals – and enjoying the journey too.

Advice, stories, and expertise about work life today.

Interpersonal Communication: A Mindful Approach to Relationships

(12 reviews)

Jason S. Wrench, State University of New York

Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter, Texas Tech University

Katherine S. Thweatt, State University of New York

Copyright Year: 2020

Last Update: 2023

ISBN 13: 9781942341772

Publisher: Milne Open Textbooks

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Jinnie Jeon, Assistant Professor, Adler University on 5/30/23

N/A read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

Content Accuracy rating: 5

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

Clarity rating: 5

Consistency rating: 5

Modularity rating: 5

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

Interface rating: 5

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

“Interpersonal Communication: A Mindful Approach to Relationships” by Jason S. Wrench, Narissa M. Punyanunt-Carter, and Katherine S. Thweatt is a truly illuminating journey into the depths of human interaction. A cutting-edge book written in an engraining and accessible style, it expertly blends theoretical foundations with practical applications, encouraging readers not just to understand but also to implement the principles of effective communication. The author’s unique focus on mindfulness, a concept rarely emphasized in similar literature, provides a fresh perspective and an essential tool for nurturing and enhancing relationships in today’s fast-paced, technology-driven world. This approach enables readers to become more present and thoughtful communicators. Despite the intricacies of the subject matter, the text remains approachable and practical, enriched by real-life examples and exercises that promote self-reflection. The original cover art by Melinda Ahan adds a touch of beauty and uniqueness to this enlightening piece of work. Overall, the book stands as a seminal text for anyone seeking to improve their interpersonal communication skills, from students to professionals and beyond.

Reviewed by Dana Trunnell, Associate Professor of Communication, Prairie State College on 3/15/23

This text covers interpersonal communication concepts and theory in extraordinary detail with the added bonus of weaving mindfulness into each topic. If anything, I find the chapters to be almost too long for undergraduate reading expectations.... read more

This text covers interpersonal communication concepts and theory in extraordinary detail with the added bonus of weaving mindfulness into each topic. If anything, I find the chapters to be almost too long for undergraduate reading expectations. That said, the mindfulness approach, along with the care taken to cover topics from multiple perspectives is appreciated. One especially great resource is the accompanying instructor resource manual, which is very detailed, updated, and helpful. It is not the afterthought that some OER textbooks provide. I would like to see more coverage of LGBTQIA+ issues.

The text is accurate, without grammatical and proofreading errors. I do think the text can be rather repetitive in spots, so word economy might be something to think about for future revisions and editions.

Interpersonal Communication is a timeless discipline and the text reflects this disciplinary longevity. I find the mindfulness approach to be an important update as the mindfulness trend establishes itself into a more long-term approach to thinking about relationships, communication, and life, in general. But, the text should be updated to be more aware and inclusive of emerging norms in race, LGBTQIA+, and sociopolitical issues.

Clarity rating: 4

Information is presented in an easy-to-read format and concepts are explained clearly. As I mentioned above, at times, the text can be pretty repetitive, which affects readability.

The content in this text is consistent with the approaches of for-profit volumes on Interpersonal Communication.

I like that this text displays the full chapter when one clicks on the link instead of only one subsection of that chapter. So, students can read the entire chapter from one link without having to scroll through other pages using navigational tools. I have found that the latter is very confusing to students, who might read only the first subsection and not the entire chapter. These links can easily be incorporated into an LMS module for easy access. In addition, each chapter is organized consistently, beginning with introductory information about each unit. The chapters are divided by major topics/concepts and each division includes Learning Objectives, Key Takeaways, and application Exercises. Time is devoted in each chapter to the application of the mindfulness approach as it relates to the topic of study. Chapters end with a list of important terms, a case study, and end-of-chapter assessments.

The content flowed well with transitions linking the chapters. I think the ordering of the chapters made sense. I also think it makes sense to organize them completely differently. The beauty of interpersonal communication is that it is so important and pervasive in our lives that we can jump in anywhere and get the discussion started. I do think, however, it is easy to adapt the flow of the text to any class – titular notions of “Chapter 1,” “Chapter 2,” etc. mean less with an electronic resource that is linked to LMS modules than a physical book.

Interface rating: 4

The textbook is easy to use and easy to navigate as it uses the consistent approach of other texts housed in the Open Textbook Library. Chapters are consistently organized and it is easy to move throughout the text. I love that hyperlinks are provided so students can access referenced surveys, measures, and other supplementary material. Unfortunately, some of these are dead links.

I did not encounter grammatical errors as I read.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

The book acknowledges the importance of cultural factors as they influence various parts of the interpersonal communication process. However, the text would benefit from an update that helps students navigate the current communication climate, especially as they relate to current issues associated with race, sociopolitical events, and LGBTQIA+ people.

This text is particularly good for introductory-level interpersonal communication students. Instructors who value mindfulness as a daily practice will find this text especially suitable for their teaching style. New instructors will be impressed and feel supported by the extensive ancillary material.

Reviewed by Beth Austin, Assistant Teaching Professor, University of Wisconsin - Superior on 9/23/22

This book covers all the relevant material covered in a typical textbook on interpersonal communication. read more

This book covers all the relevant material covered in a typical textbook on interpersonal communication.

After briefly looking through the book and with publisher and the authors' credentials, I am confident in the accuracy of the content.

This text was published in 2020 and the images, research, and mindfulness angle are still relevant. Only time will tell the reception that mindfulness receives over the years.

This book is easy to read and contains foundational jargon for the discipline.

The text is internally consistent in terms of terminology and framework.

The page layout of this book provides the reader with captivating images which provide reading breaks. The infographics are colorful and visually dynamic.

The flow and structure of this book follow the table of contents for many other interpersonal communication texts.

This book is user-friendly and easy on the eyes.

I did not find any grammatical errors in this book.

I did not see any evidence of insensitive or offensive material in the book.

Chapter 14: The Darkside of Interpersonal Communication provides information about which many undergraduate students may relate.

Reviewed by Riley Richards, Assistant Professor, Oregon Institute of Technology on 8/22/22

This book offers a unique perspective on IPC, particularly through its mindfulness lens. Through this lens, it covers the standard and expected major ideas needed to cover in an IPC class and is covered in other IPC textbooks. The information... read more

This book offers a unique perspective on IPC, particularly through its mindfulness lens. Through this lens, it covers the standard and expected major ideas needed to cover in an IPC class and is covered in other IPC textbooks. The information covered and how it is presented (i.e., readability) are fit for undergraduate students in an introductory or standalone IPC course. Areas of content that stand out in this text, compared to other IPC texts, are the chapters on mediated communication and especially the dark side of IPC. Additionally, emotions through the lens of mindfulness are discussed throughout the text while other IPC texts lump the connection between emotion and communication into a section or chapter. From an instructor standpoint, I especially appreciated the authors explaining how research findings were found (i.e., methodology) instead of simply providing the student with the information and a citation through the research spotlight sections. My only minor critique is the family and marriage relationship chapter. The marriage portion albeit limited is related to family but also seemed out of place in the text. A standalone chapter on romantic/sexual relationships seems like a natural next step in the next edition. Also, instructors can easily substitute this section for other material. Finally, the additional materials (e.g., Ted Talk, YouTube videos) provide accessible material for a student who may wish to learn more in-depth information or prefer information through different mediums.

The authors did well in balancing the breadth and depth of the subject within each chapter and across the book. I did not find parts or the sum of the parts to be biased or inaccurate.

As of this review, the content is up to date across the board from current research findings to the inclusion of seminal research and examples of concepts (e.g., COVID-19) that students can relate to. Additionally, the text is written (also through its license) in such a way that other instructors can freely expand on the authors’ examples or go in and make their own. Finally, I believe the lens of mindfulness to be around and relatable for quite some time based on national data about Generation Z coming through university doors for at least the next few decades.

The text was clear. The authors do a good job clearly defining and calling the reader’s attention to major ideas before going in-depth into the concept. The real-world case study included at the end of every chapter and its prompted thinking questions (which could easily be in-class discussion questions) is helpful for readers to consider key ideas in contexts immediately after reading the chapter.

The text keeps consistent and uses terminology as it was originally defined/discussed and is consistent with the larger IPC literature.

The text is clearly divided into chapters and sections within chapters. Instructors can easily use standalone chapters and/or add/remove sections within chapters to meet their pedagogy needs. The text is not overly self-referential, and a new reader would not need to read chapters in order. However, the reader would be best to have some background to IPC (i.e., chapters 1-3) before reading how the material applies in specific contexts.

The chapters are logically ordered and run in order similar to most IPC texts (i.e., I did not have to change my course vary much when transitioning to a new text). Each chapter opens with clear learning outcomes and ends with a reminder of the key terms and supplies the reader with a means to immediately apply the content through case studies, quizzes, and personality tests.

Overall, there were no major issues. Few exceptions such as a table going over onto the next page, textbox, or section header breaking apart sentences in the same paragraph (e.g., “end of chapter” in chapter 12). These few exceptions do not take away from the content being covered.

In my read through I found no major issues. I also offered my students extra credit to find errors (aids their writing) and they did not find any issues either.

The text was neither culturally insensitive nor offensive. The examples provided vary across genders, sexes, sexualities, races, and ethnicities. This is especially true in the culture chapter.

Overall, I strongly recommend this text to others. This is my first time using and reviewing an OER. I have used it for one summer term so far but plan to continue to use it in the future. No textbook is perfect for our individual needs, we all teach differently. However, the beauty of the author’s choice of license allows each of us to use the text differently. Thus, as the years go on, I will continue to pick and choose and supplement where I need to based on my curriculum and learning outcomes.

Reviewed by Abby Zegers, Correctional Education Coordinator, Des Moines Area Community College on 11/17/21

This text is incredibly comprehensive to the point that I feel that it could possibly be two texts or classes, depending on how much time you had. Each chapter dives relatively deep into its topic and not only is it visually appealing with up to... read more

This text is incredibly comprehensive to the point that I feel that it could possibly be two texts or classes, depending on how much time you had. Each chapter dives relatively deep into its topic and not only is it visually appealing with up to date charts, graphs and pictures, the downloadable version has hyperlinks to directly take the student to a certain inventory that the chapter is utilizing as a supplement. I found this to be really engaging. The text has a separate instructor manual which is incredibly useful with all of the materials, power points, quizzes and other necessary information needed to instruct this class. There is a glossary at the end of the text. No index was available which in my opinion would be helpful simply due to the fact that many topics/subjects or inferences are utilized throughout the chapters and not necessarily in the one devoted to that topic.

I found the content to be accurate and free from bias. I noticed only a few grammatical errors but content was incredibly accurate and up to date with references cited appropriately throughout.

Interpersonal communication is a topic that holds relevance and longevity as many things stay the same however the authors did an excellent job with current communication topics such as Chapter 12 devoted to Interpersonal Communication in Mediated Contexts. This is a topic I spend a great deal of time on with my classes as it is so current and relative to their lives right now. I think that this information will change in the future however the content available now on the topic will remain relevant as “history”. I found value in the links to different personality tests or activities that were relevant to the topic at hand and appreciated that they were available so easily as students are more likely to click a link rather than jot down something they might look up later.

I found this text to be very elaborate into many topics relating to interpersonal communication and the extensive glossary was very helpful. The supplemental activities and videos presented are a wonderful way to apply what is approached in each lesson. The text uses a “mindfulness” approach which might be a new concept to some however I think it’s a great way to see the value and importance of the topic.

I found no issues with consistency. Each chapter is laid out the same with Learning Outcomes identified in each section, exercises that could be great journal activities or discussions, key takeaways, a chapter wrap up including key terms used, a real world case study and a quiz followed by references. It is consistent throughout the text and a great way to appeal to different types of learners.

The way this text is set up allows for one to jump around if need be however; the beginning focuses more on history and theory which in itself is important along with communication models. This in itself could almost be its own text with the depth the authors go to in the material along with the abundance of activities and self-assessments allowing the reading to analyze their own styles creates a nice foundation to continue into the material. For my own classes, I would never have enough time to get through this text and give it the attention that it deserves so the ability to pick and choose topics and chapters relative to today is really an attractive part of it for me.

I think this text flows very well and much of the material from the beginning builds upon itself. The chapters are in appropriate order with building content however; it is beneficial that an instructor could pick and choose different areas they wanted to focus on without losing too much. The text ends with Chapter 13 being Interpersonal Relationships at Work and Chapter 14 being The Dark Side of Interpersonal Communication and I feel that these were appropriate choices to wrap up the text with.

I loved the ability to read through this text in electronic format and the hyperlinks were incredibly helpful and I had no issues with connectivity to sources. Images were clear and loaded as they should. I printed off a copy of the text and there were no formatting issues in doing so. I feel that utilizing the hard copy method or downloading the pdf version are both great options to have that appease different types of learners.

There were a few minor grammatical errors here and there but nothing that distracted me or was relative enough that I documented it. I felt like it was very well written and edited.

There is a specific chapter dedicated to Cultural and Environmental Factors in Interpersonal Communication however; references to cultural and gender issues are spread throughout and I feel like the information is inclusive.

Overall, I found this text to be a really great OER and am using pieces of it for my classes. I appreciate a text that appeals to many different styles of learners with text, videos, interactive quizzes and assessment and slides. So much material is available and covered and I find many sections of this to be useful in a few different classes that I teach. I am thankful to have found this text and look forward to continuing to use it.

Reviewed by Jennifer Adams, Professor, DePauw University on 11/13/21

This book is lengthy, and each chapter contains more good content than I expected. There are chapters on each topic you would expect (although organized somewhat differently than most of the popular print textbooks in this discipline). For... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

This book is lengthy, and each chapter contains more good content than I expected. There are chapters on each topic you would expect (although organized somewhat differently than most of the popular print textbooks in this discipline). For example, the information on perception is mostly in chapter 3, but some info about the topic was found across two other chapters (and attribution theory is not really included at all). There is no specific chapter on emotion, but there is content about it throughout. Furthermore, something that was somewhat new to me was incorporating the idea of "mindfulness" along with competence to understand communication processes. There is a chapter on technology that I think is growing in importance. This book doesn't really push the envelope on considering issues of identity like race or gender, but there is a good chapter on culture (and I would say that is also true of many for-profit books). The sections on relational communication are really thorough and give a good range or ideas and theories for each different relational experience. While the organization was slightly different than the book I was used to using (the Floyd text), I was able to find all of my content normally covered somewhere in this textbook.

I found no errors in this textbook that I have found aside from minor typos or a few strange sentences. The content is accurate and attributed to the correct sources. There is a lengthy and useful reference list.

This book includes all of the theories and concepts that I have been teaching for two decades. Their examples are really useful. One thing I did notice is that a lot of space is taken up by quizzes or activities - things like personality tests. I don't really use those in any way, but I do wonder if those types of things might be trendy - I don't know that or sure, but I didn't use them. I do think that the focus on "mindfulness" is something that is popular now that has not been in the past, but I certainly hope that the value in mindfulness doesn't trend away any time soon. I really thought that the book was up to date and see no reason it can't be updated relatively easily.

This book is comparable to the popular for-profit interpersonal communication textbooks that are available. It is addressed to the reader, and it is easy to read. It does introduce new terminology and concepts , but these are always defined clearly. At the end of every chapter, there is a 'take-away" section that includes key-terms, so there is the ability to look those up outside of the basic text as well. There are activities at the end of each chapter as well, to help develop.

Yes, the entire book is about interpersonal communication and it does not diverge from topics covered in the popular for-profit books. I didn't find any inconsistencies in the way that the material is presented. In fact, the opposite is true: their focus on "mindfulness" as a skill that can be developed holds each chapter together, so that there is not just information about the important ideas and theories, there is also a constant reflection on the values of mindfulness as it relates to all of the topics (and relationship types) that are covered.

This is really well organized. The book is divided into chapters, and each chapter is divided into subsections that have numbered placement within the chapter and headings throughout. (For example, chapter seven materials are divided into 7.1, 7.2, 7.3, etc). If you didn't want to assign the entire book, you could easily pick sections here and there to use (and you can save only those sections as PDFs to insert on your syllabus or organizing platforms).

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The book is not organized like my class was, but it wasn't a major deal and I simply hoped around a bit. So, for example, I thought that the chapter on culture should come sooner than chapter 6, perhaps before verbal and nonverbal communication. I also wasn't sure that some of the content in chapter 7 called "Talking and Listening" was placed well there - it seemed redundant in some ways, but some info (like social penetration theory or the johari window) seem like they should be in an earlier chapter about perception. That being said, these concerns are ultimately very minor - the content I expected was there, and I could assign page #s for specific sections that I needed to address at different times in the semester. I did not use this book chronologically from chapter 1 to the end, but that has been true for for-profit books I have used in the past, too. I found the chronology to be good.

I used this book in the fall of 2021, and recommended that all students download the PDF version, which is what I primarily use. The book's TOC is hyperlinked, and so you can easily find the content you are looking for and click to go to the relevant sections. When I do keyword searches for specific theories or concepts, they come up easily without error. It's easy to use and the layout is professional and attractive (pictures and images come through formatted correctly, charts and graphs look clear).

This book is well written. Aside from a few typos here and there, I didn't find lots of problems with readability. It's not perfect; for example, sometimes where there are bullet points, they are not written in a parallel style, or something like that which might be noticeable, but that was pretty infrequent. The writing is clear and correct.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

There is nothing offensive that I found in this book. The book includes examples and ideas that are inclusive or race, ethnicity and gender. There is an entire chapter on cultural communication, so it does present information about cross-cultural differences and communication. I would like to see more about gender and more explicitly about race, but some of that content IS here (I just find myself spending more time on this every semester, but I must use supplemental material on topics such as white fragility or privilege and how that impacts interpersonal communication).

Although I hate the price of textbooks, I have been hesitant to use open source materials in the past due to a perceived lesser quality. This book has changed my mind. It isn't perfect, but it saves students 50-100 dollars, and the information that they purchase isn't perfect either. This book presents as professional, and it reads that way as well. Of course, I supplement this book with popular readings and examples, but almost all of the academic content I needed was in this book. I do recommend it.

Reviewed by Joseph Nicola, Professor, Century College on 10/6/21

The text provides a very detailed and granular index and glossary. Very helpful when planning lessons and homework readings. The text is hyperlinked from the index/glossary making it helpful for students. Presents a good explanation of the many... read more

The text provides a very detailed and granular index and glossary. Very helpful when planning lessons and homework readings. The text is hyperlinked from the index/glossary making it helpful for students. Presents a good explanation of the many important aspects of the communication discipline.

Content is accurate, error-free and unbiased. Does a fair job at covering the large content scope of Interpersonal Comm subject manner. Does not address some popular content covered in an undergrad course on the subject. However the text does provide a nice foundation for class lecture and discussion. Sources are referenced at the end of every chapter.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

Content is up-to-date, but not in a way that will quickly make the text obsolete within a short period of time. The text is written and/or arranged in such a way that necessary updates will be relatively easy and straightforward to implement.

The text clearly covers the basic principles of the large content subject matter. Does a fare job a covering basic principles that are foundational for the discipline.

The subject of gender identity is not greatly covered. Terms within the LGBTQIA are briefly mentioned but not explained further. A future edition would benefit from this addition.

Good concordance and glossary of terms with page numbers. Easy to read and follow. Has “Key Takeaways” and End of Chapter “Exercises at the end of each chapter. For the most part, the text adequately covers the material needed.

Yes. It appears consistent throughout.

This is a well organized text. That does a fair job at covering that large foundational scope of interpersonal communication. Has “Key Takeaways” and "End of Chapter Exercises" at the end of each chapter.are very nice for class activities and discussion.

Text is organized very well.

Good text and well interfaced. Easy to navigate.

Text is well written with clear paragraphs, bullet points and formatted topic headings. No errors found.

The text does devote a large amount of content to explaining the importance of cultural awareness for being a competent communicator. Provides a good starting foundation to start with class lectures and class discussion. Graphics do depict a diverse student population which is nice to see that intention. Some content that could be added on: *It should be noted that the important subject topic of gender identity is not greatly covered with this text. Terms within the LGBTQIA are briefly mentioned but not explained further. *Only briefly mentioned the importance of Emotional Intelligence but lacks in content and key terms within the subject and practical examples.

The subject of gender identity is not greatly covered. Terms within the LGBTQ+ are briefly mentioned but not explained further. Well designed and layout with some minimal graphics and color-coated topic headings. There could be more for a future printing. Offers some personality and perspective assessment activities that would serve as a good chapter activity.

Reviewed by Aditi Paul, Assistant Professor, Pace University on 8/13/21

The authors do a really good job at covering a variety of introductory, foundational, and contemporary topics pertaining to interpersonal communication. read more

The authors do a really good job at covering a variety of introductory, foundational, and contemporary topics pertaining to interpersonal communication.

Content Accuracy rating: 3

The authors do a good job of laying the foundation of the importance of mindfulness in interpersonal communication. However, the discussion surrounding mindfulness and how it should be integrated into different aspects of interpersonal communication was less than thorough. Mindfulness almost came as an afterthought rather than being weaved into the main material in most chapters.

The importance of mindfulness in interpersonal communication is a highly relevant topic, especially in today's age where most of our communication over digital media has become primarily mindless. The authors also do a good job at including new and relevant topics such as body positivity in non-verbal communication, computer-mediated communication apprehension, internet infidelity, and postmodern friendships.

The text was very clear and easy to follow.

Consistency rating: 3

As mentioned earlier, the lack of consistency was evident in the discussion of mindfulness. The authors introduce mindfulness in terms of "attention, intention, and attitude" in the first chapter. But in the rest of the chapters, especially chapter 5 onward, the conversation around mindfulness dwindles.

The modularity of the book was good.

The organization of the book was good. The only critique I would have is the placement of the chapter on culture and interpersonal communication. I would have preferred that topic to be introduced earlier than chapter 6 since a lot of our verbal and non-verbal communication is colored by culture.

The interface of the book was good.

The grammar of the book was good.

The book was culturally sensitive. It included sexually and culturally marginalized groups into the conversation.

Reviewed by Rebecca Oldham, Assistant Professor, Middle Tennessee State University on 5/20/21

This textbook provides a thorough introduction to communication studies. It covers multiple important theories, seminal research, major concepts, and practical suggestions for improving communication. The instructor guide includes many helpful... read more

This textbook provides a thorough introduction to communication studies. It covers multiple important theories, seminal research, major concepts, and practical suggestions for improving communication. The instructor guide includes many helpful tools, including chapter outlines, presentation slides, in-class activities, practice quiz questions, and links to TEDTalks and YouTube example videos from recent popular films and TV shows. It also comes with a student workbook. This textbook has as many, if not more, supplemental materials as a traditional textbook.

However, some sections of the book could be expounded upon with future revisions. For example, I would have expected to see more variety of research about on marriage beyond Fitzpatricks typologies (e.g., John Gottman's research or references to other romantic relationship research). Other topics I would like to see in future revisions are (1) the rhetorical triangle and (2) the elaboration likelihood model.

However, the comphrehensiveness is still such that instructors additions to this textbook for curriculum would merely be supplemental.

This textbook uses a mixture of seminal and recent research to review major topics of interpersonal communication to supports accuracy. When relevant, the authors describe research studies and methods, not just the findings, which enhances students' science and information literacy.

The textbook is written with up-to-date research and references to recent culture and political issues from the past year (e.g., COVID-19, political polarization). References to mediated communication are very up-to-date, with the exception of TikTok not being mention. The instructor's manual provides excellent examples of concepts in recent popular TV and film that students are sure to enjoy because they are not out-dated and the media is familiar for this age group.

However, I would reframe the concept of relationships in the textbook beyond "marriage" to "committed romantic relationships" given the increase of polyamory/consensual non-monogamy, open relationships, and long-term cohabitation/commitment without marriage. Although marriage is still largely the norm in the United States, the changing landscape of romantic relationship development could be more strongly present in this textbook.

The tone of the authorship balances an academic and conversational tone well-suited for an undergraduate audience. Jargon is well-defined in-text and glossary is provided. The writing is professional and academic, without being esoteric.

No inconsistencies in terminology, theoretical frameworks, nor pedagogical approaches were detected. The authors have clearly reviewed this textbook for quality and consistency.

The textbook is well organized into manageably-sized blocks of text with many headings and subheadings, which helps the reader navigate the text. Instructors should find it easy to identify how parts of this textbook overlap with their existing communcation or relationships course for ready adaptation and integration into existing curriculum.

This textbook is largely organized like other communication textbooks: Introduction/Overview, Identity, Verbal/Nonverbal Communication, Culture, Mediated Communication, and various types of relationships (e.g., family, professional, etc.). It's logical and familiar organization makes it easy to navigate and integrate with standard introducation to communication courses.

Very few issues with distortion of images or overlap in page elements or formatting inconsistencies.

No obvious grammatical errors were detected. The writing style is accessible and easy to read.

Authors clearly took steps to be inclusive and draw attention to issues of equity with regard to gender identity, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, religion, political identity, and other groups (for examples, see sections on dating scripts, post-modern friendships, racist language, cross-group friendships). I would recommend future revisions include information about African American Vernacular English (AAVE) possible under a section about culture, dialects, or accents, given its direct relevance to communication.

I plan on replacing the textbook for my Interpersonal Communication course with this textbook. In most respects, it is equivalent to the textbook that is currently required. However, it also is an improvement on the current textbook in terms of the density of research citations and in the supplemental material. Instructors of introductory communication courses can feel confident in adopting this textbook to reduce costs, lower educational barriers, without sacrificing educational rigor and quality.

Reviewed by Jennifer Burns, Adjunct Faculty, Middlesex Community College on 3/13/21

Interpersonal Communication: A Mindful Approach to Relationships, provides an in-depth understanding to the variables that comprise interpersonal communication, I especially appreciate the mindful (know thyself) lens!! read more

Interpersonal Communication: A Mindful Approach to Relationships, provides an in-depth understanding to the variables that comprise interpersonal communication, I especially appreciate the mindful (know thyself) lens!!

After examining the context and student workbook, I was impressed with the content accuracy. I did not pick up on saturation of bias and or stigmatizing language.

Yes, content is up-to-date, and it is encouraged to contact the author with needed updates, and or changes. It is also encouraged to personalize the book to fit the needs of the students!

This textbook is clear, concise and to the point!

The framework and theory are woven throughout the text.

The text is divided into digestible sections, that allow for independent assignment of course material. The formatting is easy on the eyes!

Love the text organization, the content is clear, logical and sequential!

You do need an access code from author to obtain access to the teacher resources.

Did not notice grammatical errors.

I did not perceive this text to be culturally insensitive.

Reviewed by Jessica Martin, Adjunct Instructor, Communication Studies, Portland Community College on 1/5/21

This book presents a comprehensive breakdown of the major types of interpersonal communication. The chapters included in this course text align with the traditional content in an interpersonal communication course. I like how it also includes a... read more

This book presents a comprehensive breakdown of the major types of interpersonal communication. The chapters included in this course text align with the traditional content in an interpersonal communication course. I like how it also includes a chapter focused on mediated communication, as this is an important topic of discussion for our current day and age.

Consistent sources are cited throughout the course text at the end of each chapter, proving its accuracy . The sources appear to be non-bias and overall boost the credibility of the text.

Being that the text includes a chapter primarily focused on mediated communication, I would say that the text is up to date and contains adequate information to support relevancy.

The text is written in a straightforward, simplistic type of manner. This would make it easy for any college student to follow along with the content and keep up with the terminology. Any time a new term is introduced, plenty of examples are given to explain that term. This same format is followed consistently throughout the course text.

Each chapter begins with clear learning outcomes, follows with consistent sub-headers and clear introductions to new terminology. I also noted how each chapters includes exercises to help students further understand course content.

Each chapter is clearly divided up into specific sections to help with lesson planning and overall lecturing materials. This would make it easy to create lecture material for the course.

The text is organized effectively in that there are clear transitions from one topic to another. As mentioned previously, each chapter begins with clear learning objectives, and concludes with exercises, key-takeaways, and a list of key terms.

I would say that overall this course text is easy to navigate. Plenty of charts, tables, and photographs are consistently used to help introduce new ideas and key theories.

I did not note any grammatical errors.

The text includes a chapter titled "Culture and Environmental Factors in Interpersonal Communication," which includes all of the necessary key terms that you would hope to see in an interpersonal communication course.

Reviewed by Prachi Kene, Professor, Rhode Island College on 10/22/20