8 Lessons We Can Learn From the COVID-19 Pandemic

BY KATHY KATELLA May 14, 2021

Note: Information in this article was accurate at the time of original publication. Because information about COVID-19 changes rapidly, we encourage you to visit the websites of the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), World Health Organization (WHO), and your state and local government for the latest information.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed life as we know it—and it may have changed us individually as well, from our morning routines to our life goals and priorities. Many say the world has changed forever. But this coming year, if the vaccines drive down infections and variants are kept at bay, life could return to some form of normal. At that point, what will we glean from the past year? Are there silver linings or lessons learned?

“Humanity's memory is short, and what is not ever-present fades quickly,” says Manisha Juthani, MD , a Yale Medicine infectious diseases specialist. The bubonic plague, for example, ravaged Europe in the Middle Ages—resurfacing again and again—but once it was under control, people started to forget about it, she says. “So, I would say one major lesson from a public health or infectious disease perspective is that it’s important to remember and recognize our history. This is a period we must remember.”

We asked our Yale Medicine experts to weigh in on what they think are lessons worth remembering, including those that might help us survive a future virus or nurture a resilience that could help with life in general.

Lesson 1: Masks are useful tools

What happened: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) relaxed its masking guidance for those who have been fully vaccinated. But when the pandemic began, it necessitated a global effort to ensure that everyone practiced behaviors to keep themselves healthy and safe—and keep others healthy as well. This included the widespread wearing of masks indoors and outside.

What we’ve learned: Not everyone practiced preventive measures such as mask wearing, maintaining a 6-foot distance, and washing hands frequently. But, Dr. Juthani says, “I do think many people have learned a whole lot about respiratory pathogens and viruses, and how they spread from one person to another, and that sort of old-school common sense—you know, if you don’t feel well—whether it’s COVID-19 or not—you don’t go to the party. You stay home.”

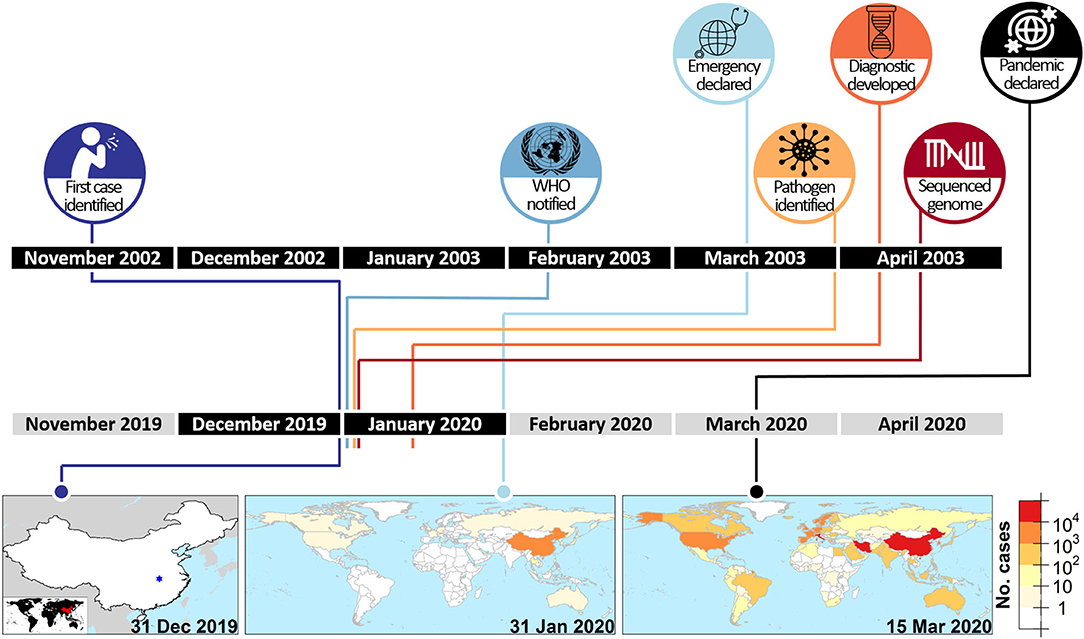

Masks are a case in point. They are a key COVID-19 prevention strategy because they provide a barrier that can keep respiratory droplets from spreading. Mask-wearing became more common across East Asia after the 2003 SARS outbreak in that part of the world. “There are many East Asian cultures where the practice is still that if you have a cold or a runny nose, you put on a mask,” Dr. Juthani says.

She hopes attitudes in the U.S. will shift in that direction after COVID-19. “I have heard from a number of people who are amazed that we've had no flu this year—and they know masks are one of the reasons,” she says. “They’ve told me, ‘When the winter comes around, if I'm going out to the grocery store, I may just put on a mask.’”

Lesson 2: Telehealth might become the new normal

What happened: Doctors and patients who have used telehealth (technology that allows them to conduct medical care remotely), found it can work well for certain appointments, ranging from cardiology check-ups to therapy for a mental health condition. Many patients who needed a medical test have also discovered it may be possible to substitute a home version.

What we’ve learned: While there are still problems for which you need to see a doctor in person, the pandemic introduced a new urgency to what had been a gradual switchover to platforms like Zoom for remote patient visits.

More doctors also encouraged patients to track their blood pressure at home , and to use at-home equipment for such purposes as diagnosing sleep apnea and even testing for colon cancer . Doctors also can fine-tune cochlear implants remotely .

“It happened very quickly,” says Sharon Stoll, DO, a neurologist. One group that has benefitted is patients who live far away, sometimes in other parts of the country—or even the world, she says. “I always like to see my patients at least twice a year. Now, we can see each other in person once a year, and if issues come up, we can schedule a telehealth visit in-between,” Dr. Stoll says. “This way I may hear about an issue before it becomes a problem, because my patients have easier access to me, and I have easier access to them.”

Meanwhile, insurers are becoming more likely to cover telehealth, Dr. Stoll adds. “That is a silver lining that will hopefully continue.”

Lesson 3: Vaccines are powerful tools

What happened: Given the recent positive results from vaccine trials, once again vaccines are proving to be powerful for preventing disease.

What we’ve learned: Vaccines really are worth getting, says Dr. Stoll, who had COVID-19 and experienced lingering symptoms, including chronic headaches . “I have lots of conversations—and sometimes arguments—with people about vaccines,” she says. Some don’t like the idea of side effects. “I had vaccine side effects and I’ve had COVID-19 side effects, and I say nothing compares to the actual illness. Unfortunately, I speak from experience.”

Dr. Juthani hopes the COVID-19 vaccine spotlight will motivate people to keep up with all of their vaccines, including childhood and adult vaccines for such diseases as measles , chicken pox, shingles , and other viruses. She says people have told her they got the flu vaccine this year after skipping it in previous years. (The CDC has reported distributing an exceptionally high number of doses this past season.)

But, she cautions that a vaccine is not a magic bullet—and points out that scientists can’t always produce one that works. “As advanced as science is, there have been multiple failed efforts to develop a vaccine against the HIV virus,” she says. “This time, we were lucky that we were able build on the strengths that we've learned from many other vaccine development strategies to develop multiple vaccines for COVID-19 .”

Lesson 4: Everyone is not treated equally, especially in a pandemic

What happened: COVID-19 magnified disparities that have long been an issue for a variety of people.

What we’ve learned: Racial and ethnic minority groups especially have had disproportionately higher rates of hospitalization for COVID-19 than non-Hispanic white people in every age group, and many other groups faced higher levels of risk or stress. These groups ranged from working mothers who also have primary responsibility for children, to people who have essential jobs, to those who live in rural areas where there is less access to health care.

“One thing that has been recognized is that when people were told to work from home, you needed to have a job that you could do in your house on a computer,” says Dr. Juthani. “Many people who were well off were able do that, but they still needed to have food, which requires grocery store workers and truck drivers. Nursing home residents still needed certified nursing assistants coming to work every day to care for them and to bathe them.”

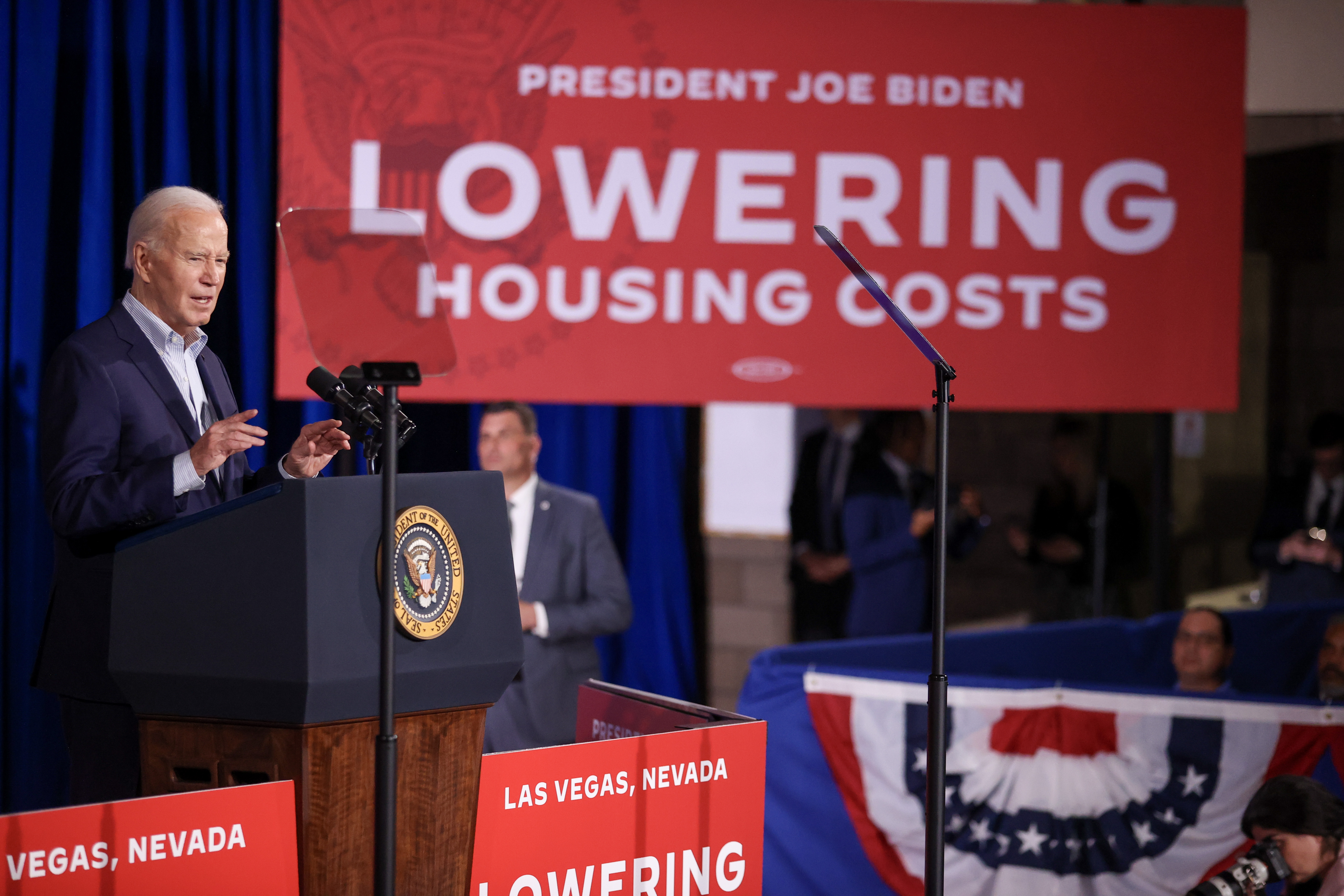

As far as racial inequities, Dr. Juthani cites President Biden’s appointment of Yale Medicine’s Marcella Nunez-Smith, MD, MHS , as inaugural chair of a federal COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force. “Hopefully the new focus is a first step,” Dr. Juthani says.

Lesson 5: We need to take mental health seriously

What happened: There was a rise in reported mental health problems that have been described as “a second pandemic,” highlighting mental health as an issue that needs to be addressed.

What we’ve learned: Arman Fesharaki-Zadeh, MD, PhD , a behavioral neurologist and neuropsychiatrist, believes the number of mental health disorders that were on the rise before the pandemic is surging as people grapple with such matters as juggling work and childcare, job loss, isolation, and losing a loved one to COVID-19.

The CDC reports that the percentage of adults who reported symptoms of anxiety of depression in the past 7 days increased from 36.4 to 41.5 % from August 2020 to February 2021. Other reports show that having COVID-19 may contribute, too, with its lingering or long COVID symptoms, which can include “foggy mind,” anxiety , depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder .

“We’re seeing these problems in our clinical setting very, very often,” Dr. Fesharaki-Zadeh says. “By virtue of necessity, we can no longer ignore this. We're seeing these folks, and we have to take them seriously.”

Lesson 6: We have the capacity for resilience

What happened: While everyone’s situation is different (and some people have experienced tremendous difficulties), many have seen that it’s possible to be resilient in a crisis.

What we’ve learned: People have practiced self-care in a multitude of ways during the pandemic as they were forced to adjust to new work schedules, change their gym routines, and cut back on socializing. Many started seeking out new strategies to counter the stress.

“I absolutely believe in the concept of resilience, because we have this effective reservoir inherent in all of us—be it the product of evolution, or our ancestors going through catastrophes, including wars, famines, and plagues,” Dr. Fesharaki-Zadeh says. “I think inherently, we have the means to deal with crisis. The fact that you and I are speaking right now is the result of our ancestors surviving hardship. I think resilience is part of our psyche. It's part of our DNA, essentially.”

Dr. Fesharaki-Zadeh believes that even small changes are highly effective tools for creating resilience. The changes he suggests may sound like the same old advice: exercise more, eat healthy food, cut back on alcohol, start a meditation practice, keep up with friends and family. “But this is evidence-based advice—there has been research behind every one of these measures,” he says.

But we have to also be practical, he notes. “If you feel overwhelmed by doing too many things, you can set a modest goal with one new habit—it could be getting organized around your sleep. Once you’ve succeeded, move on to another one. Then you’re building momentum.”

Lesson 7: Community is essential—and technology is too

What happened: People who were part of a community during the pandemic realized the importance of human connection, and those who didn’t have that kind of support realized they need it.

What we’ve learned: Many of us have become aware of how much we need other people—many have managed to maintain their social connections, even if they had to use technology to keep in touch, Dr. Juthani says. “There's no doubt that it's not enough, but even that type of community has helped people.”

Even people who aren’t necessarily friends or family are important. Dr. Juthani recalled how she encouraged her mail carrier to sign up for the vaccine, soon learning that the woman’s mother and husband hadn’t gotten it either. “They are all vaccinated now,” Dr. Juthani says. “So, even by word of mouth, community is a way to make things happen.”

It’s important to note that some people are naturally introverted and may have enjoyed having more solitude when they were forced to stay at home—and they should feel comfortable with that, Dr. Fesharaki-Zadeh says. “I think one has to keep temperamental tendencies like this in mind.”

But loneliness has been found to suppress the immune system and be a precursor to some diseases, he adds. “Even for introverted folks, the smallest circle is preferable to no circle at all,” he says.

Lesson 8: Sometimes you need a dose of humility

What happened: Scientists and nonscientists alike learned that a virus can be more powerful than they are. This was evident in the way knowledge about the virus changed over time in the past year as scientific investigation of it evolved.

What we’ve learned: “As infectious disease doctors, we were resident experts at the beginning of the pandemic because we understand pathogens in general, and based on what we’ve seen in the past, we might say there are certain things that are likely to be true,” Dr. Juthani says. “But we’ve seen that we have to take these pathogens seriously. We know that COVID-19 is not the flu. All these strokes and clots, and the loss of smell and taste that have gone on for months are things that we could have never known or predicted. So, you have to have respect for the unknown and respect science, but also try to give scientists the benefit of the doubt,” she says.

“We have been doing the best we can with the knowledge we have, in the time that we have it,” Dr. Juthani says. “I think most of us have had to have the humility to sometimes say, ‘I don't know. We're learning as we go.’"

Information provided in Yale Medicine articles is for general informational purposes only. No content in the articles should ever be used as a substitute for medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician. Always seek the individual advice of your health care provider with any questions you have regarding a medical condition.

More news from Yale Medicine

Long covid, ‘long cold’: what to know about post-acute infection syndromes.

Understanding a Pathologist’s Role

What Happens When You Still Have Long COVID Symptoms?

I Thought We’d Learned Nothing From the Pandemic. I Wasn’t Seeing the Full Picture

M y first home had a back door that opened to a concrete patio with a giant crack down the middle. When my sister and I played, I made sure to stay on the same side of the divide as her, just in case. The 1988 film The Land Before Time was one of the first movies I ever saw, and the image of the earth splintering into pieces planted its roots in my brain. I believed that, even in my own backyard, I could easily become the tiny Triceratops separated from her family, on the other side of the chasm, as everything crumbled into chaos.

Some 30 years later, I marvel at the eerie, unexpected ways that cartoonish nightmare came to life – not just for me and my family, but for all of us. The landscape was already covered in fissures well before COVID-19 made its way across the planet, but the pandemic applied pressure, and the cracks broke wide open, separating us from each other physically and ideologically. Under the weight of the crisis, we scattered and landed on such different patches of earth we could barely see each other’s faces, even when we squinted. We disagreed viciously with each other, about how to respond, but also about what was true.

Recently, someone asked me if we’ve learned anything from the pandemic, and my first thought was a flat no. Nothing. There was a time when I thought it would be the very thing to draw us together and catapult us – as a capital “S” Society – into a kinder future. It’s surreal to remember those early days when people rallied together, sewing masks for health care workers during critical shortages and gathering on balconies in cities from Dallas to New York City to clap and sing songs like “Yellow Submarine.” It felt like a giant lightning bolt shot across the sky, and for one breath, we all saw something that had been hidden in the dark – the inherent vulnerability in being human or maybe our inescapable connectedness .

More from TIME

Read More: The Family Time the Pandemic Stole

But it turns out, it was just a flash. The goodwill vanished as quickly as it appeared. A couple of years later, people feel lied to, abandoned, and all on their own. I’ve felt my own curiosity shrinking, my willingness to reach out waning , my ability to keep my hands open dwindling. I look out across the landscape and see selfishness and rage, burnt earth and so many dead bodies. Game over. We lost. And if we’ve already lost, why try?

Still, the question kept nagging me. I wondered, am I seeing the full picture? What happens when we focus not on the collective society but at one face, one story at a time? I’m not asking for a bow to minimize the suffering – a pretty flourish to put on top and make the whole thing “worth it.” Yuck. That’s not what we need. But I wondered about deep, quiet growth. The kind we feel in our bodies, relationships, homes, places of work, neighborhoods.

Like a walkie-talkie message sent to my allies on the ground, I posted a call on my Instagram. What do you see? What do you hear? What feels possible? Is there life out here? Sprouting up among the rubble? I heard human voices calling back – reports of life, personal and specific. I heard one story at a time – stories of grief and distrust, fury and disappointment. Also gratitude. Discovery. Determination.

Among the most prevalent were the stories of self-revelation. Almost as if machines were given the chance to live as humans, people described blossoming into fuller selves. They listened to their bodies’ cues, recognized their desires and comforts, tuned into their gut instincts, and honored the intuition they hadn’t realized belonged to them. Alex, a writer and fellow disabled parent, found the freedom to explore a fuller version of herself in the privacy the pandemic provided. “The way I dress, the way I love, and the way I carry myself have both shrunk and expanded,” she shared. “I don’t love myself very well with an audience.” Without the daily ritual of trying to pass as “normal” in public, Tamar, a queer mom in the Netherlands, realized she’s autistic. “I think the pandemic helped me to recognize the mask,” she wrote. “Not that unmasking is easy now. But at least I know it’s there.” In a time of widespread suffering that none of us could solve on our own, many tended to our internal wounds and misalignments, large and small, and found clarity.

Read More: A Tool for Staying Grounded in This Era of Constant Uncertainty

I wonder if this flourishing of self-awareness is at least partially responsible for the life alterations people pursued. The pandemic broke open our personal notions of work and pushed us to reevaluate things like time and money. Lucy, a disabled writer in the U.K., made the hard decision to leave her job as a journalist covering Westminster to write freelance about her beloved disability community. “This work feels important in a way nothing else has ever felt,” she wrote. “I don’t think I’d have realized this was what I should be doing without the pandemic.” And she wasn’t alone – many people changed jobs , moved, learned new skills and hobbies, became politically engaged.

Perhaps more than any other shifts, people described a significant reassessment of their relationships. They set boundaries, said no, had challenging conversations. They also reconnected, fell in love, and learned to trust. Jeanne, a quilter in Indiana, got to know relatives she wouldn’t have connected with if lockdowns hadn’t prompted weekly family Zooms. “We are all over the map as regards to our belief systems,” she emphasized, “but it is possible to love people you don’t see eye to eye with on every issue.” Anna, an anti-violence advocate in Maine, learned she could trust her new marriage: “Life was not a honeymoon. But we still chose to turn to each other with kindness and curiosity.” So many bonds forged and broken, strengthened and strained.

Instead of relying on default relationships or institutional structures, widespread recalibrations allowed for going off script and fortifying smaller communities. Mara from Idyllwild, Calif., described the tangible plan for care enacted in her town. “We started a mutual-aid group at the beginning of the pandemic,” she wrote, “and it grew so quickly before we knew it we were feeding 400 of the 4000 residents.” She didn’t pretend the conditions were ideal. In fact, she expressed immense frustration with our collective response to the pandemic. Even so, the local group rallied and continues to offer assistance to their community with help from donations and volunteers (many of whom were originally on the receiving end of support). “I’ve learned that people thrive when they feel their connection to others,” she wrote. Clare, a teacher from the U.K., voiced similar conviction as she described a giant scarf she’s woven out of ribbons, each representing a single person. The scarf is “a collection of stories, moments and wisdom we are sharing with each other,” she wrote. It now stretches well over 1,000 feet.

A few hours into reading the comments, I lay back on my bed, phone held against my chest. The room was quiet, but my internal world was lighting up with firefly flickers. What felt different? Surely part of it was receiving personal accounts of deep-rooted growth. And also, there was something to the mere act of asking and listening. Maybe it connected me to humans before battle cries. Maybe it was the chance to be in conversation with others who were also trying to understand – what is happening to us? Underneath it all, an undeniable thread remained; I saw people peering into the mess and narrating their findings onto the shared frequency. Every comment was like a flare into the sky. I’m here! And if the sky is full of flares, we aren’t alone.

I recognized my own pandemic discoveries – some minor, others massive. Like washing off thick eyeliner and mascara every night is more effort than it’s worth; I can transform the mundane into the magical with a bedsheet, a movie projector, and twinkle lights; my paralyzed body can mother an infant in ways I’d never seen modeled for me. I remembered disappointing, bewildering conversations within my own family of origin and our imperfect attempts to remain close while also seeing things so differently. I realized that every time I get the weekly invite to my virtual “Find the Mumsies” call, with a tiny group of moms living hundreds of miles apart, I’m being welcomed into a pocket of unexpected community. Even though we’ve never been in one room all together, I’ve felt an uncommon kind of solace in their now-familiar faces.

Hope is a slippery thing. I desperately want to hold onto it, but everywhere I look there are real, weighty reasons to despair. The pandemic marks a stretch on the timeline that tangles with a teetering democracy, a deteriorating planet , the loss of human rights that once felt unshakable . When the world is falling apart Land Before Time style, it can feel trite, sniffing out the beauty – useless, firing off flares to anyone looking for signs of life. But, while I’m under no delusions that if we just keep trudging forward we’ll find our own oasis of waterfalls and grassy meadows glistening in the sunshine beneath a heavenly chorus, I wonder if trivializing small acts of beauty, connection, and hope actually cuts us off from resources essential to our survival. The group of abandoned dinosaurs were keeping each other alive and making each other laugh well before they made it to their fantasy ending.

Read More: How Ice Cream Became My Own Personal Act of Resistance

After the monarch butterfly went on the endangered-species list, my friend and fellow writer Hannah Soyer sent me wildflower seeds to plant in my yard. A simple act of big hope – that I will actually plant them, that they will grow, that a monarch butterfly will receive nourishment from whatever blossoms are able to push their way through the dirt. There are so many ways that could fail. But maybe the outcome wasn’t exactly the point. Maybe hope is the dogged insistence – the stubborn defiance – to continue cultivating moments of beauty regardless. There is value in the planting apart from the harvest.

I can’t point out a single collective lesson from the pandemic. It’s hard to see any great “we.” Still, I see the faces in my moms’ group, making pancakes for their kids and popping on between strings of meetings while we try to figure out how to raise these small people in this chaotic world. I think of my friends on Instagram tending to the selves they discovered when no one was watching and the scarf of ribbons stretching the length of more than three football fields. I remember my family of three, holding hands on the way up the ramp to the library. These bits of growth and rings of support might not be loud or right on the surface, but that’s not the same thing as nothing. If we only cared about the bottom-line defeats or sweeping successes of the big picture, we’d never plant flowers at all.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Why We're Spending So Much Money Now

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- Breaker Sunny Choi Is Heading to Paris

- Why TV Can’t Stop Making Silly Shows About Lady Journalists

- The Case for Wearing Shoes in the House

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

Learn new career skills while gaining an edge in today’s job market with Skills Builder for Work.

Popular Searches

AARP daily Crossword Puzzle

Hotels with AARP discounts

Life Insurance

AARP Dental Insurance Plans

Suggested Links

AARP MEMBERSHIP — $12 FOR YOUR FIRST YEAR WHEN YOU SIGN UP FOR AUTOMATIC RENEWAL

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

- right_container

Work & Jobs

Social Security

AARP en Español

- Membership & Benefits

- AARP Rewards

- AARP Rewards %{points}%

Conditions & Treatments

Drugs & Supplements

Health Care & Coverage

Health Benefits

Staying Fit

Your Personalized Guide to Fitness

AARP Hearing Center

Ways To Improve Your Hearing

Brain Health Resources

Tools and Explainers on Brain Health

How to Save Your Own Life

Scams & Fraud

Personal Finance

Money Benefits

View and Report Scams in Your Area

AARP Foundation Tax-Aide

Free Tax Preparation Assistance

AARP Money Map

Get Your Finances Back on Track

Budget & Savings

Make Your Appliances Last Longer

Small Business

Age Discrimination

Flexible Work

Freelance Jobs You Can Do From Home

AARP Skills Builder

Online Courses to Boost Your Career

31 Great Ways to Boost Your Career

ON-DEMAND WEBINARS

Tips to Enhance Your Job Search

Get More out of Your Benefits

When to Start Taking Social Security

10 Top Social Security FAQs

Social Security Benefits Calculator

Medicare Made Easy

Original vs. Medicare Advantage

Enrollment Guide

Step-by-Step Tool for First-Timers

Prescription Drugs

9 Biggest Changes Under New Rx Law

Medicare FAQs

Quick Answers to Your Top Questions

Care at Home

Financial & Legal

Life Balance

LONG-TERM CARE

Understanding Basics of LTC Insurance

State Guides

Assistance and Services in Your Area

Prepare to Care Guides

How to Develop a Caregiving Plan

End of Life

How to Cope With Grief, Loss

Recently Played

Word & Trivia

Atari® & Retro

Members Only

Staying Sharp

Mobile Apps

More About Games

Right Again! Trivia

Right Again! Trivia – Sports

Atari® Video Games

Throwback Thursday Crossword

Travel Tips

Vacation Ideas

Destinations

Travel Benefits

Beach vacation ideas

Vacations for Sun and Fun

Plan Ahead for Tourist Taxes

AARP City Guide

Discover Seattle

How to Pick the Right Cruise for You

Entertainment & Style

Family & Relationships

Personal Tech

Home & Living

Celebrities

Beauty & Style

TV for Grownups

Best Reality TV Shows for Grownups

Robert De Niro Reflects on His Life

Free Online Novel

Read 'Chase'

Sex & Dating

Spice Up Your Love Life

Navigate All Kinds of Connections

How to Create a Home Gym

Store Medical Records on Your Phone?

Maximize the Life of Your Phone Battery

Virtual Community Center

Join Free Tech Help Events

Create a Hygge Haven

Soups to Comfort Your Soul

AARP Smart Guide

Spring Clean All of Your Spaces

Driver Safety

Maintenance & Safety

Trends & Technology

How to Keep Your Car Running

We Need To Talk

Assess Your Loved One's Driving Skills

AARP Smart Driver Course

Building Resilience in Difficult Times

Tips for Finding Your Calm

Weight Loss After 50 Challenge

Cautionary Tales of Today's Biggest Scams

7 Top Podcasts for Armchair Travelers

Jean Chatzky: ‘Closing the Savings Gap’

Quick Digest of Today's Top News

AARP Top Tips for Navigating Life

Get Moving With Our Workout Series

You are now leaving AARP.org and going to a website that is not operated by AARP. A different privacy policy and terms of service will apply.

Go to Series Main Page

15 Lessons the Coronavirus Pandemic Has Taught Us

What we've learned over the past 12 months could pay off for years to come.

For the past year, our country has been mired in not one deep crisis but three: a pandemic , an economic meltdown and one of the most fraught political transitions in our history. Interwoven in all three have been challenging issues of racial disparity and fairness. Dealing with all of this has dominated much of our energy, attention and, for many Americans, even our emotions.

But spring is nearly here, and we are, by and large, moving past the worst moments as a nation — which makes it a good time to take a deep breath and assess the changes that have occurred. While no one would be displeased if we could magically erase this whole pandemic experience, it's been the crucible of our lives for a year, and we have much to learn from it — and even much to gain.

AARP Membership — $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

AARP asked dozens of experts to go beyond the headlines and to share the deeper lessons of the past year that have had a particular impact on older Americans. More importantly, we asked them to share how we can use these learnings to make life better for us as we recover and move forward. Here is what they told us.

Lesson 1: Family Matters More Than We Realized

"The indelible image of the older person living alone and having to struggle — we need to change that. You're going to see more older people home-sharing within families and cohousing across communities to avoid future situations of tragedy."

—Marc Freedman, CEO and president of Encore.org and author of How to Live Forever: The Enduring Power of Connecting the Generations

Norman Rockwell would have needed miles of canvas to portray the American family this past year. You can imagine the titles: The Family That Zooms Together. Generations Under One Roof. Grandkids Outside My Window. The Shared Office . “Beneath the warts and complexities of all that went wrong, we rediscovered the interdependence of generations and how much we need each other,” Freedman says. Among the lessons:

Adult kids are OK. A Pew Research Center survey last summer found that 52 percent of the American population between ages 18 and 29 were living with parents, a figure unmatched since the Great Depression. From February to July 2020, 2.6 million young adults moved back with one or both parents. That's a lot of shared Netflix accounts. It's also a culture shift, says Karen Fingerman, director of the Texas Aging & Longevity Center at the University of Texas at Austin. “After the family dinners together, grandparents filling in for childcare, and the wise economic sense, it's going to be acceptable for adult family members to co-reside,” Fingerman says. “At least for a while.”

What We've Learned From the Pandemic

• Lesson 1: Family Matters • Lesson 2: Medical Breakthroughs • Lesson 3: Self-Care Matters • Lesson 4: Be Financially Prepared • Lesson 5: Age Is Just a Number • Lesson 6: Getting Online for Good • Lesson 7: Working Anywhere • Lesson 8: Restoring Trust • Lesson 9: Gathering Carefully • Lesson 10: Isolation's Health Toll • Lesson 11: Getting Outside • Lesson 12: Wealth Disparities’ Toll • Lesson 13: Preparing for the Future • Lesson 14: Tapping Telemedicine • Lesson 15: Cities Are Changing

Spouses and partners are critical to well-being . “The ones who've done exceptionally well are couples in long-term relationships who felt renewed intimacy and reconnection to each other,” says social psychologist Richard Slatcher, who runs the Close Relationships Laboratory at the University of Georgia.

Difficult caregiving can morph into good-for-all home-sharing. To get older Americans out of nursing homes and into a loved one's home — a priority that has gained in importance and urgency due to the pandemic — will take more than just a willing child or grandchild. New resources could help, like expanding Medicaid programs to pay family caregivers, such as an adult child, or initiatives like the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly, a Medicare-backed benefit currently helping 50,000 “community dwelling” seniors with medical services, home care and transportation.

"A positive piece this year has been the pause to reflect on how we can help people stay in their homes as they age, which is what everyone wants,” says Nancy LeaMond, AARP's chief advocacy and engagement officer. “If you're taking care of a parent, grandparent, aging partner or yourself, you see more than ever the need for community and government support, of having technology to communicate with your doctor and of getting paid leave for family caregivers. The pandemic has forced us to think about all these things, and that's very positive.”

Family may be the best medicine of all . “Now we know if you can't hug your 18-month-old granddaughter in person, you can read to her on FaceTime,” says Jane Isay, author of several books about family relationships. “You can send your adult kids snail mail. You can share your life's wisdom even from a distance. These coping skills may be the greatest gifts of COVID” — to an older generation that deeply and rightly fears isolation.

Lesson 2: We Have Unleashed a Revolution in Medicine

" One of the biggest lessons we've learned from COVID is that the scientific community working together can do some pretty amazing things."

—John Cooke, M.D., medical director of the RNA Therapeutics Program at Houston Methodist Hospital's DeBakey Heart and Vascular Center

In the past it's taken four to 20 years to create conventional vaccines. For the new messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, it was a record-setting 11 months. The process may have changed forever the way drugs are developed.

"Breakthroughs” come after years of research . Supporting the development of the COVID-19 vaccines was more than a decade of research into mRNA vaccines, which teach human cells how to make a protein that triggers a specific immune response. The research had already overcome many challenging hurdles, such as making sure that mRNA wouldn't provoke inflammation in the body, says Lynne E. Maquat, director of the University of Rochester's Center for RNA Biology: From Genome to Therapeutics.

Vaccines may one day treat heart disease and more. In the near future, mRNA technology could lead to better flu vaccines that could be updated quickly as flu viruses mutate with the season, Maquat says, or the development of a “universal” flu shot that might be effective for several years. Drug developers are looking at vaccines for rabies, Zika virus and HIV. “I expect to see the approval of more mRNA-based vaccines in the next several years,” says mRNA researcher Norbert Pardi, a research assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

"We could use mRNA for diseases and conditions that can't be treated with drugs,” Cooke explains.

It may also target our biggest killers . Future mRNA therapies could help regenerate muscle in failing hearts and target the unique genetics of individual cancers with personalized cancer vaccines. “Every case of cancer is unique, with its own genetics,” Cooke says. “Doctors will be able to sequence your tumor and use it to make a vaccine that awakens your immune system to fight it.” Such mRNA vaccines will also prepare us for future pandemics, Maquat says.

In the meantime, use the vaccines we have available. Don't skip recommended conventional vaccines now available to older adults for the flu, pneumonia, shingles and more, Pardi says. The flu vaccine alone, which 1 in 3 older adults skipped in the winter 2019 season, saves up to tens of thousands of lives a year and lowers your risk for hospitalization with the flu by 28 percent and for needing a ventilator to breathe by 46 percent.

Lesson 3: Self Care Is Not Self-Indulgence

"Not only does self-care have positive outcomes for you, but it also sets an example to younger generations as something to establish and maintain for your entire life."

—Richelle Concepcion, clinical psychologist and president of the Asian American Psychological Association

As the virus upended life last spring, America became hibernation nation. Canned, dry and instant soup sales have risen 37 percent since last April. Premium chocolate sales grew by 21 percent in the first six months of the pandemic. The athleisure market that includes sweatpants and yoga wear saw its 2020 U.S. revenue push past an estimated $105 billion.

With 7 in 10 American workers doing their jobs from home, “COVID turned the focus, for all ages, on the small, simple pleasures that soothe and give us meaning,” says Isabel Gillies, author of Cozy: The Art of Arranging Yourself in the World.

Why care about self-care? Pampering is vital to well-being — for yourself and for those around you. Activities that once felt indulgent became essential to our health and equilibrium, and that self-care mindset is likely to endure. Whether it is permission to take long bubble baths, tinkering in the backyard “she shed,” enjoying herbal tea or seeing noon come while still in your robe, “being good to yourself offers a necessary reprieve from whatever horrors threaten us from out there,” Gillies says. Being good to yourself is good for others, too. A recent European survey found that 77 percent of British respondents 75 and younger consider it important to take their health into their own hands in order not to burden the health care system.

Nostalgia TV, daytime PJs. It's OK to use comfort as a crutch. Comfort will help us ease back to life. Some companies are already hawking pajamas you can wear in public. Old-fashioned drive-ins and virtual cast reunions for shows like Taxi, Seinfeld and Happy Days will likely continue as long as the craving is there. (More than half the consumers in a 2020 survey reported finding comfort in revisiting TV and music from their childhood.) Even the iconic “Got Milk?” ads are back, after dairy sales started to show some big upticks.

So, cut yourself some slack. Learn a new skill; adopt a pet; limit your news diet; ask for help if you need it. You've lived long enough to see the value of prioritizing number one. “Not only does self-care have positive outcomes for you,” Concepcion says, “but it also sets an example to younger generations as something to establish and maintain for your entire life."

Lesson 4: Have a Stash Ready for the Next Crisis

"The need to augment our retirement savings system to help people put away emergency savings is crucial."

—J. Mark Iwry, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and former senior adviser to the U.S. secretary of the Treasury

Before the pandemic, nearly 4 in 10 households did not have the cash on hand to cover an unexpected $400 expense, according to a Federal Reserve report. Then the economic downturn hit. By last October, 52 percent of workers were reporting reduced hours, lower pay, a layoff or other hits to their employment situation. A third had taken a loan or early withdrawal from a retirement plan , or intended to. “Alarm bells were already ringing, but many workers were caught off guard without emergency savings,” says Catherine Collinson, CEO and president of the Transamerica Institute. “The pandemic has laid bare so many weaknesses in our safety net."

Companies can help . One solution could be a workplace innovation that's just beginning to catch on: an employee-sponsored rainy-day savings account funded with payroll deductions. By creating a dedicated pot of savings, the thinking goes, workers are less likely to tap retirement accounts in an emergency. “It's much better from a behavioral standpoint to separate short-term savings from long-term savings,” Iwry says. (AARP has been working to make these accounts easier to create and use and is already offering them to its employees.)

Funding that emergency savings account with automatic payroll deductions is a key to the program's success. “Sometimes you think you don't have the money to save, but if a little is put away for you each pay period, you don't feel the pinch,” Iwry notes.

We're off to a good start . Thanks to quarantines and forced frugality, Americans’ savings rate — the average percentage of people's income left over after taxes and personal spending — skyrocketed last spring, peaking at an unprecedented 33.7 percent. On the decline since then, most recently at 13.7 percent, it's still above the single-digit rates characterizing much of the past 35 years. Where it will ultimately settle is unclear; currently, it's in league with high-saving countries Mexico and Sweden. The real model of thriftiness: China, where, according to the latest available figures, the household savings rate averaged at least 30 percent for 14 years straight.

Lesson 5: The Adage ‘Age Is Just a Number’ Has New Meaning

"This isn't just about the pandemic. Your health is directly related to lifestyle — nutrition, physical activity, a healthy weight and restorative sleep."

—Jacob Mirsky, M.D., primary care physician at the Massachusetts General Hospital Revere HealthCare Center and an instructor at Harvard Medical School

Just a few months ago, researchers at Scotland's University of Glasgow asked a big question: If you're healthy, how much does older age matter for risk of death from COVID? The health records of 470,034 women and men revealed some intriguing answers.

Age accounted for a higher risk, but comorbidities (essentially, having two or more health issues simultaneously) mattered much more. Specifically, risk for a fatal infection was four times higher for healthy people 75 and older than for all participants younger than 65. But if you compared all those 75 and older — including those with chronic health condition s like high blood pressure, obesity or lung problems — that shoved the grim odds up thirteenfold.

AARP NEWSLETTERS

%{ newsLetterPromoText }%

%{ description }%

Privacy Policy

ARTICLE CONTINUES AFTER ADVERTISEMENT

Live healthfully, live long . More insights from the study: A healthy 75-year-old was one-third as likely to die from the coronavirus as a 65-year-old with multiple chronic health issues. The bottom line: Age affects your risk of severe illness with COVID, but you should be far more focused on avoiding chronic health conditions. “Coronavirus highlighted yet another reason it's so important to attend to health factors like poor diet and lack of exercise that cause so much preventable illness and death,” says Massachusetts General's Mirsky. “Lifestyle changes can improve your overall health, which will likely directly reduce your risk of developing severe COVID or dying of COVID."

Exercise remains critical . In May 2020 a British study of 387,109 adults in their 40s through 60s found a 38 percent higher risk for severe COVID in people who avoided physical activity. “Mobility should be considered one of the vital signs of health,” concludes exercise psychologist David Marquez, a professor in the department of kinesiology and nutrition at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

AARP® Dental Insurance Plan administered by Delta Dental Insurance Company

Dental insurance plans for members and their families

Lesson 6: We Befriended Technology, and There's No Going Back

"Folks who have tried online banking will stay with it. It won't mean they won't go back to branches, but they might go back for a different purpose."

—Theodora Lau, founder of financial technology consulting firm Unconventional Ventures

Of course, the world has long been going digital . But before the pandemic, standard operating procedure for most older Americans was to buy apples at the grocery, try the shoes on first before buying, have your doctor measure your blood pressure and see that hot new movie at the theater.

Arguably the biggest long-term societal effect of the pandemic will be a grand flipping of the switch that makes the digital solution the first choice of many Americans for handling life's tasks. We still may cling to a few IRL (in real life) experiences, but it is increasingly apparent that easy-to-use modern virtual tools are the new default.

"If nothing else, COVID has shown us how resilient and adaptable humans are as a society when forced to change,” says Joseph Huang, CEO of StartX, a nonprofit that helps tech companies get off the ground. “We've been forced to learn new technologies that, in many cases, have been the only safe way to continue to live our lives and stay connected to our loved ones during the pandemic.”

The tech boom wasn't just video calls and streaming TV. Popular food delivery apps more than doubled their earnings last year. Weddings and memorial services were held over videoconferences (yes, we'll go back to in-person ones but probably with cameras and live feeds now to include remote participants). In the financial sector, PayPal reported that its fastest-growing user group was people over 50; Chase said about half of its new online users were 50-plus. In telehealth, more doctors conducted routine exams via webcam than ever before — and, in response, insurance coverage expanded for these remote appointments. “It quickly became the only way to operate at scale in today's world,” Huang says, “both for us as patients and for the doctors and nurses who treat us. Telemedicine will turn out to be a better and more effective experience in many cases, even after COVID ends."

Tech is for all . To financial technology expert Lau, the tech adoption rate by older people is no surprise. She never believed the myth that older people lack such knowledge. “There's a difference between knowing how to use something versus preferring to use it,” Lau says. “Sometimes we know how, but we prefer face-to-face interaction.” And now those preferences are shifting.

Lesson 7: Work Is Anywhere Now — a Shift That Bodes Well for Older Americans

"One of the major impacts of the new working-from-home focus is that more jobs are becoming non-location-specific."

—Carol Fishman Cohen, cofounder of iRelaunch, which works with employers to create mid-career return-to-work programs for older workers

Necessity is the mother of reinvention : Forced to work remotely since the onset of the pandemic, millions of workers — and their managers — have learned they could be just as productive as they were at the office, thanks to videoconferencing, high-speed internet and other technologies. “This has opened a lot of corporate eyes,” says Steven Allen, professor of economics at North Carolina State University's Poole College of Management. Twitter, outdoor-goods retailer REI and insurer Lincoln Financial Group are a few of the companies that have announced plans to shift toward more remote work on a permanent basis.

Face-lift your Face-Time . Yes, many workers are tied to a location: We will always need nurses, police, roofers, machine operators, farmers and countless other workers to show up. But if you are among the people who are now able to work remotely, you may be able to live in a less expensive area than where your employer is based — or work right away from the home you were planning to retire to later on, Cohen says. As remote hiring takes hold, how you project yourself on-screen becomes more of a factor. “This puts more pressure on you to make sure you show up well in a virtual setting,” Cohen notes. And don't assume being comfortable with Zoom is a feather in your cap; mentioning it is akin to listing “proficient in Microsoft Word” on your résumé.

Self-employed workers have suffered during the pandemic — nearly two-thirds report being hurt financially, according to the “State of Independence in America 2020” report from MBO Partners — but remote work could fuel their comeback. Before the pandemic, notes Steve King, partner at Emergent Research, businesses with a high percentage of remote workers used a high percentage of independent contractors. “Now that companies are used to workers not being as strongly attached physically to a workplace, they'll be more amenable to hiring independent workers,” he says.

Travel less, stay longer . Tired of sitting in traffic to and from work? Can't stand flying across country for a single meeting? Ridding yourself of these hassles with an internet connection and Zoom calls may be the incentive you need to work longer. People often quit jobs because of little frustrations, Allen says. But now, he adds, “the things that wear you down may be going by the wayside."

Ageism remains a threat . Older workers — who before the coronavirus enjoyed lower unemployment rates than mid-career workers — have been hit especially hard by the pandemic. In December, 45.5 percent of unemployed workers 55 and older had been out of work for 27 weeks or more, compared with 35.1 percent of younger job seekers. Some employers, according to reports this fall, are replacing laid-off older workers with younger, lower-cost ones, instead of recalling those older employees. Psychological studies, Allen says, indicate that older workers have better communication and interpersonal skills — both of which are critical for successful remote work. But whether those strengths can offset age discrimination in the workplace is unknown.

Lesson 8: Our Trust in One Another Has Frayed, but It Can Be Slowly Restored

"Truth matters, but it requires messaging and patience.”

—Historian John M. Barry, author of The Great Influenza

Even before our views perforated along lines dotted by pandemic politics, race, class and whether Bill Gates is trying to save us or track us, we were losing faith in society. In 1997, 64 percent of Americans put a “very great or good deal of trust” in the political competence of their fellow citizens; today only a third of us feel that way. A 2019 Pew survey found that the majority of Americans say most people can't be trusted. It's even tougher to trust in the future. Only 13 percent of millennials say America is the greatest country in the world, compared with 45 percent of members of the silent generation. No wonder that by June of last year, “national pride” was lower than at any point since Gallup began measuring. To trust again:

As life returns, look beyond your familiar pod. “Distrust breeds distrust, but hope isn't lost for finding common ground, especially for older people,” says Encore.org's Freedman. “Even in the era of ‘OK, boomer’ and ‘OK, millennial’ — memes that dismiss entire generations with an eye roll — divides are bridgeable with what Freedman calls “proximity and purpose.” Rebuilding trust together, across generations, under shared priorities and common humanity.” He points to pandemic efforts like Good Neighbors from the home-sharing platform Nesterly, which pairs older and younger people to provide cross-generational support, and UCLA's Generation Xchange, which connects Gen X mentors with children in grades K-3 in South Los Angeles, where educational achievement is notoriously poor. “Engaging with people for a common goal makes you trust them,” he says.

Be patient but verify facts. History also provides a guide. In the wake of the 1918 influenza pandemic that killed between 50 million and 100 million people, trust in authority withered after local and national government officials played down the disease's threats in order to maintain wartime morale. Historian Barry points out that the head of the Army's’ division of communicable diseases was so worried about the collective failure of trust that he warned that “civilization could easily disappear ... from the face of the earth.” It didn't then, and it won't now, Barry says.

Verify facts and then decide. Check reliable, balanced news sources (such as Reuters and the Associated Press) and unbiased fact-checking sites (such as PolitiFact) before clamping down on an opinion.

Perhaps most important, be open to changing conditions and viewpoints. “As we see vaccines and therapeutic drugs slowly gain widespread success in fighting this virus, I think we'll start to overcome some of our siloed ways of thinking and find relief — together as one — that this public health menace is ending,” Barry adds. “We have to put our faith in other people to get through this together.”

Lesson 9: The Crowds Will Return, but We'll Gather Carefully

"Masks and sanitizers will be part of the norm for years, the way airport and transportation security measures are still in place from 9/11."

— Christopher McKnight Nichols, associate professor of history at Oregon State University and founder of the Citizenship and Crisis Initiative

The COVID-19 pandemic won't end with bells tolling or a ticker-tape parade . Instead, we'll slowly, cautiously ease back to familiar activities. For all our fears of the coronavirus, many of us can't wait to resume a public life: When 1,000 people 65 and older were asked which pursuits they were most eager to start anew post-pandemic, 78 percent said going out to dinner, 76 percent picked getting together with family and friends, 71 percent chose travel, and 30 percent cited going to the movies.

Seeing art , attending concerts, cheering in a stadium — even going to class reunions we might have once dreaded — we'll do them again. But how will we return to feeling comfortable in groups of tens, hundreds and thousands? And will these gatherings be different? How we come together:

Don't expect the same old, same old . Just as the rationing, isolation and economic crisis caused by World War I and the Spanish flu epidemic “led to a kind of awakening of how we assembled,” Nichols says, expect COVID to shake up the nature and personality of our public spaces. Back in the 1920s, it was the rise of jazz clubs, organized athletics, fraternal organizations and the golden age of the movie cinema. As the pandemic subsides, we'll probably see more temperature-controlled outdoor event and dining spaces, more pedestrian and bicycling options, more city parks and more hybrid events that give you the option to attend virtually.

Retrain your brain . Psychologists say the techniques of cognitive behavioral therapy can help people at any age regain the certainty and confidence they need to venture into the public space post-pandemic. “Visualizing good outcomes and repeating a stated goal can help overcome whatever obstacles are holding you back,” says Gabriele Oettingen, a professor of psychology at New York University, who suggests making an “if-then plan” to reacclimate to public life. If eating indoors at a restaurant is too agitating, even if you've been vaccinated, then try a table outside first. If a bucket-list family vacation to Italy feels too daunting, then book a stateside trip together first. “There's always an alternative if something stands in the way of you fulfilling your wish,” she says. “Eventually, you'll get there.”

Lesson 10: Loneliness Hurts Health More Than We Thought

"What we've learned from COVID is that isolation is everyone's problem. It doesn't just happen to older adults; it happens to us all."

— Julianne Holt-Lunstad, professor of psychology and neuroscience at Brigham Young University

How deadly is the condition of loneliness? During the first five months of the pandemic, nursing home lockdowns intended to safeguard older and vulnerable adults with dementia contributed to the deaths of an additional 13,200 people compared with previous years, according to a shocking Washington Post investigation published last September. “People with dementia are dying,” the article notes, “not just from the virus but from the very strategy of isolation that's supposed to protect them.”

Isolation may be the new normal . Fifty-six percent of adults age 50-plus said they felt isolated in June 2020, double the number who felt lonely in 2018, a University of Michigan poll found. Rates of psychological distress rose for all adults as the pandemic deepened — increasing sixfold for young adults and quadrupling for those ages 30 to 54, according to a Johns Hopkins University survey published in JAMA in June. And it's hard to tell whether the workplace culture many of us relied on for social support will fully return anytime soon.

Those 50-plus have a leg up. “Older adults with higher levels of empathy, compassion, decisiveness and self-reflection score lowest for loneliness,” says Dilip Jeste, M.D., director of the Sam and Rose Stein Institute for Research on Aging at the University of California, San Diego. “Research shows that many older adults have handled COVID psychologically better than younger adults. With age comes experience and wisdom. You've lived through difficult times before and survived.”

Help yourself by helping others. Jeste says that when older adults share their wisdom with younger people, everyone benefits. “Young people are reassured about the future,” he adds. “Older adults feel even more confident. They're role models. Their contributions matter."

Lesson 11: When Your World Gets Small, Nature Lets Us Live Large

"For older people in particular, nature provided a way to shake off the weight and hardships associated with stay-at-home orders, of social isolation and of the stress of being the most vulnerable population in the pandemic."

— Kathleen Wolf, a research social scientist in the School of Environmental and Forest Sciences at the University of Washington

One silver lining to COVID-19's dark cloud : Clouds themselves became more familiar to all of us. So did birds, trees, bees, shooting stars and window gardens. Nearly 6 in 10 Americans have a new appreciation for nature because of the pandemic, according to one survey that also found three-quarters of respondents reported a boost in their mood while spending time outside.

By nearly every measure, the planet got more love during COVI D. And wouldn't it be nice if that continued going forward? The ins and outs on our new outdoor life:

Move somewhere greener (or at least move around more outside). How you access nature is up to you, but consider the options. Nearly a third of Americans were considering moving to less populated areas, according to a Harris Poll taken last year during the pandemic. Walking, running and hiking became national pastimes. One day last September, Boston's BlueBikes bike-share system saw its highest-ever single-day ridership, with 14,400 trips recorded. Stargazers and bird-watchers helped push binocular sales up 22 percent.

Once known mainly as a retirement activity, pickleball has been the fastest-growing sport in America, with almost 3.5 million U.S. players of all ages participating in the contact-free outdoor net game designed for players of any athletic ability. The return of the pandemic “victory garden” reflects research that finds 79 percent of patients feel more relaxed and calm after spending time in a garden.

Make the city less gritty . The University of Washington's Wolf thinks that our collective nature kick will go beyond a run on backyard petunias. Her research brief on the benefits of nearby nature in cities for older adults suggests we may rethink the design of neighborhood environments to facilitate older people's outdoor activities. That means more places to sit, more green spaces associated with the health status of older people, safer routes and paths, and more allotment for community gardens. “It's impossible to overestimate the value these outdoor spaces have on reducing stressful life events, improving working memory and adding meaning and happiness in older people's lives,” Wolf says.

If you can't get out, bring nature in . Even video and sounds of nature can provide health gains to those shut indoors, says Marc Berman of the University of Chicago's Environmental Neuroscience Lab. “Listening to recordings of crickets chirping or waves crashing improved how our subjects performed on cognitive tests,” he says.

Above all, the environment is in your hands, so take action to protect it . “We've seen a lot of older folks stepping up their activity in trail conservation, stream cleaning, being forest guides and things like that this year, which indicates a shift in how that age group interacts with nature,” says Cornell University gerontologist Karl Pillemer.

"There's an old saw that older people care less than younger people about the environment. But given this year's nature boom, I'm expecting that to change. As the generation that gave birth to the environmental movement enters retirement, we're likely to see a wave of interest in conservation among those 60 and up."

Lesson 12: You Can Hope for Stability — but Best Be Prepared for the Opposite

"COVID-19, perhaps more than any other disaster, demonstrated that we need to continue ensuring response plans are flexible and scalable. You can't predict exactly what a disaster will bring, but if you know what tools you have in your tool kit, you can pull out the right one you need when you need it."

— Linda Mastandrea, director of the Office of Disability Integration and Coordination for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

The pandemic was among the toughest slap-in-the-face moments in recent history to remind us that everything — everything — in our lives can change in a moment. While older Americans may have a deep-seated desire for stability and security after all it took to get to an advanced age, we certainly cannot bank on it. Which is why the word of the year, and perhaps the coming century, is “resilience.” Not just at the individual level but at every social tier, from family to community to the nation as a whole.

Banish fear . “We don't have to live in fear” of some looming disaster, says former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Tom Frieden, now president and CEO of global public health initiative Resolve to Save Lives. “By strengthening our defenses and investing in preparedness, we can live easier knowing that communities have what they need to better respond in moments of crisis."

Preparation must start at the top . For government, that means a new commitment to plans that allow, not so much for stockpiles but for the ability to ramp up production of crucial equipment when needed. “We need increased, sustained, predictable base funding for public health security defense programs that prevent, detect and respond to outbreaks such as COVID-19 or pandemic influenza,” Frieden says.

Being creative and even entrepreneurial helps , says Jeff Schlegelmilch, director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University's Earth Institute. Warehouses full of masks could have helped us initially, he says, but stockpiles of equipment aren't the answer on their own. In a free market there is pressure to sell off surpluses, so he suggests we reimagine our manufacturing capacities for times of emergency. When whiskey distillers stepped up to make hand sanitizer, and auto manufacturers switched gears to build ventilators, we saw “glimmers of solutions,” Schlegelmilch says, the sort of responses we may need to tee up in the future.

Focus on health care . Prime among the areas that need to be addressed, crisis management consultant Luiz Hargreaves says, are overwhelmed health care systems. “They were living a disaster before the pandemic. When the pandemic came, it was a catastrophe.” But Hargreaves hopes we will use this wake-up call to produce new solutions, rather than to return to old ways. “Extraordinary times,” he says, “call for extraordinary measures."

Lesson 13: Wealth Inequality Is Growing, and It Affects Us All

"It's outrageous that somebody could work full-time and not even be able to pay rent, let alone food and clothing. There's a recognition that there's a problem on both the left and right. "

— Joseph Stiglitz, Nobel Prize–winning economist, Columbia University professor and author of The Price of Inequality

"The data is pretty dramatic,” says Stiglitz, one of America's most-esteemed economists. Government economists estimate that unemployment rates in this pandemic are less than 5 percent for the highest earners but as high as 20 percent for the lowest-paid ones. “People at the bottom have disproportionately experienced the disease, and those at the bottom have lost jobs in enormous disproportion, too."

As white-collar professionals work from home and stay socially distant, frontline workers in government, transportation and health care — as well as retail, dining and other service sectors — face far greater health risks and unemployment. “We try to minimize interactions as we try to protect ourselves,” he says, “yet we realize that minimizing those interactions is also taking away jobs.” The disparate effects of the pandemic are particularly evident along racial lines, points out Jean Accius, AARP senior vice president for global thought leadership. “Job losses have hit communities of color disproportionately,” he says. And there's a health gap, too, with people of color — who have a greater likelihood than white Americans to be frontline workers — experiencing higher rates of COVID-19 infection, hospitalizations and mortality, and lower rates of vaccinations. “What we're seeing is a double whammy for communities of color,” Accius says. “It is hitting them in their wallets. And it's hitting them with regard to their health."

Those economic and health crises, along with protests over racial injustice over the past year, says Accius, “have really sparked major conversations around what do we need to do in order to advance equity in this country."

A rising gap between rich and poor in any society, Stiglitz argues, increases economic instability, reduces opportunities and results in less investment in public goods such as education and public transportation. But the country appears primed to make some changes that could help narrow the wealth gap, he says. Among them are President Biden's proposals to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour, increase the earned income tax credit for low-income workers and provide paid sick leave. Stiglitz also proposes raising taxes on gains from sales of stocks and other securities not held in retirement accounts. “The notion that people who work for a living shouldn't pay higher taxes than those who speculate for a living seems not to be a hard idea to get across,” Stiglitz says.

"Many people continue to say, ‘It's time for us to get back to normal,'” Accius says. “Well, going back to normal means that we're in a society where those that have the least continue to be impacted the most — a society where older adults are marginalized and communities of color are devalued. We have to be honest with what we are going through as a collective nation. And then we have to be bold and courageous, to really build a society where race and other social demographic factors do not determine your ability to live a longer, healthier and more productive life.”

Who Owns America's Wealth?

For some, hard times bring opportunity.

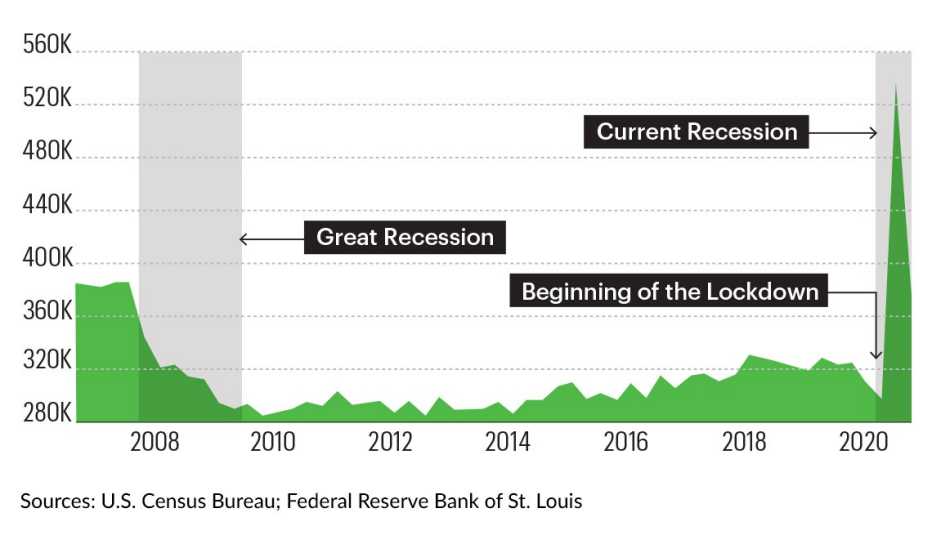

Want a positive reminder of the American way? When the going got tough this past summer, many people responded by planning a new business. In the second half of 2020, there was a 40 percent jump over the prior year's figures in applications to form businesses highly likely to hire employees, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Significantly, no such spike occurred during the Great Recession, points out Alexander Bartik, assistant professor of economics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “That's cause for some optimism — that there are people who are trying to start new things,” he says. One possible reason this time is different: Unlike during that recession, the stock market and home values have held on, and those sources of personal wealth are often what people draw upon to fund small-business start-ups.

High-propensity* Business Applications in the U.S.

*Businesses likely to have employees

Lesson 14: The Benefits of Telemedicine Have Become Indisputable

"The processes we developed to avoid face-to-face care have transformed the way we approach diabetes care management.”

— John P. Martin, M.D., codirector of Diabetes Complete Care for Kaiser Permanente Southern California

If there was ever any truth to the stereotype of the older person whose life revolved around a constant calendar of in-person doctor appointments, it's certainly been tossed out the window this past year due to the strains of the pandemic on our health care system. The timing was fortuitous in one way: Telemedicine was ready for prime time and has proved to be a godsend, particularly for those with chronic health conditions.

Say goodbye to routine doctor visits . Patients who sign up for remote blood sugar monitoring at Kaiser Permanente in Southern California use Bluetooth-enabled meters to transmit results via a smartphone app directly to their health records. “ Remote monitoring allows us to recognize early when there should be adjustments to treatment,” Martin says.

We need to push for more access . The pandemic underlines the need for more home-based medical help with chronic conditions. But that takes both willingness and a lot of gear, such as Bluetooth-enabled blood pressure monitors and, on the doctor side, systems to store and analyze the data. “People need access to the equipment, and health care systems have to be ready to handle all that data,” says Mirsky of Massachusetts General Hospital.

Group doctor visits may be a way forward . Mirsky is conducting virtual group visits and remote monitoring of blood sugar for his patients with type 2 diabetes. “Instead of having a few minutes with each person to talk about important issues — like blood sugar testing, diet and exercise — we get an hour or more to go over it,” he says. “At every meeting somebody in the group has a great tip I've never heard of, like a new YouTube exercise channel or fitness app. There's group support, too. I see group visits like this continuing into the future, becoming part of routine chronic disease care for all patients who want it."

Bottom line: The doctor is in (your house) . Managing chronic health conditions like diabetes “can't just be about getting in your car and driving to your doctor's office,” Martin says. Taking care of your health conditions yourself is the path forward.

Lesson 15: Our Cities Won't Ever Be the Same

"This is obviously a very big watershed moment in how we live, how we organize our cities and our communities. There are going to be long-lasting changes."

— Chris Jones, chief planner at Regional Plan Association, a New York–based urban planning organization

"When you're alone and life is making you lonely, you can always go downtown,” Petula Clark sang in her 1964 chart-topping ode to city life. Well, things change. Suddenly, crowds are the enemy, public buses and subways a health risk, packed office towers out of favor, and a roomy suburban home seems just where you want to be. But don't write off downtowns just yet.

The office and business district will look different. Many workers have little interest in returning to a 9-to-5 life. For those who do make the commute, they may find cubicles replaced with more flexible work spaces focused on common areas, with ample outdoor seating space for meetings and working lunches. And some now-empty offices will likely be converted into apartments and condos, making downtowns more vibrant. “Now you have an opportunity to remake a central business district into an actual neighborhood,” says Richard Florida, author of The Rise of the Creative Class and a cofounder of CityLab, an online publication about urbanism.

Public spaces will serve more of the public. Those areas set up for outdoor restaurant dining — some of those will likely remain. Streets and parking lots have been turned into plazas and promenades. Many cities have already opened miles of bike lanes; in 2020, Americans bought bikes, including electric bikes, in record numbers. “This idea of social space, where you can get outside and enjoy that active public realm, is going to become increasingly important,” says Lynn Richards, the president and CEO of Congress for the New Urbanism, which champions walkable cities.

Contributors to this report: Sari Harrar, David Hochman, Ronda Kaysen, Lexi Pandell, Jessica Ravitz and Ellen Stark

Discover AARP Members Only Access

Already a Member? Login

More From AARP

For Some, Covid-19 Spurs an Identity Crisis: What Do I Want Out of Life?

After Vaccination, Tiptoeing Back to Normalcy

When Can Visitors Return to Nursing Homes?

Vaccination means visits are back with far fewer restrictions

AARP Value & Member Benefits

Carrabba's Italian Grill®

10% off dine-in or curbside carryout orders placed by phone

AARP Travel Center Powered by Expedia: Hotels & Resorts

Up to 10% off select hotels

ADT™ Home Security

Savings on monthly home security monitoring

AARP® Staying Sharp®

Activities, recipes, challenges and more with full access to AARP Staying Sharp®

SAVE MONEY WITH THESE LIMITED-TIME OFFERS

- Get Our Daily Email

- Ways To Support Us

- About InspireMore

- Advertise With Us

- Website Terms

- Privacy Policy

- Advertising Terms

- Causes That Matter

9 Valuable Lessons We’ve Learned During The Pandemic

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

We’re not going to lie: It’s been a little hard to find the silver lining at times this past year.

With so much stress, loss, and pain at the forefront of our minds, it sometimes feels like we’re in a constant waiting game, counting down the minutes until our “normal” lives are back. But after a year like this, there’s no going back to normal because we’ve all been changed forever in one way or another. We’ve lived 12 years in the past 12 months, and we’ve grown in the process – and that is a silver lining to be proud of!

So we decided the best way to acknowledge and appreciate the growth we’ve experienced is by taking a second to reflect on this past year and find the positives that were woven through each day.

To see the good that has come from these hard times, we adopted a lens of learning and growing, and it empowered us to do just that! Here are nine important lessons we’ve learned in the midst of COVID-19.

1. Family is nonnegotiable.

For many of us, this year brought with it quality family time that we never expected and, honestly, might never have had otherwise. It’s reminded us just how much family matters. And I don’t just mean blood relatives, I mean chosen family, too.

We were encouraged to take a step out of the craziness of our former lives and deeply invest in those relationships again, whether it was face-to-face or not.

We’ve had the opportunity to not just catch up on life, but to also spend priceless time with our loved ones, asking personal questions, being there for the important moments, leaning on each other for support, and growing together. As a result, we remembered just how much we need each other!

2. Prioritize health and wellness .

When the pandemic first began, the world started paying attention to health, wellness, and hygiene like never before. We realized just how effective our handwashing wasn’t , how much we shouldn’t be touching our faces, and the beauty of both modern and natural medicine. These are all crucial practices and levels of care that will hopefully stick with us in the future.

Not only that, but without the usual benefits of daily activity, in-person workouts, and restaurant dining, a microscope was placed on just how willing we were to maintain our wellness all on our own.

With the pandemic came a myriad of free cooking and workout classes on social media and a realization that, particularly when we’re stuck inside, our bodies really do need nutrients and activity to survive.

3. We can get by on less. Much less.

The road to discovering how little we need was paved with uncertainty. With the overwhelming job loss that came with the pandemic, people had to learn how to pinch pennies, clip coupons, and trim excess like never before.

Even for those who kept their jobs, without indoor dining, salons, gyms, and a wealth of other standard social activities, saving money actually became easier to do. Even though we’ll all be lining the doors when things are back to normal, we realized in the process that we actually can live on a lot less and still be content.

4. Build that nest egg.

In addition to pinching those pennies, we learned the endless value of having a rainy day fund – or more appropriately, an emergency fund. An emergency fund is one that is set aside for the most essential of needs, including rent, medical expenses, childcare, and food.

As we’ve all heard over and over again, these are unprecedented times. The nature of unprecedented times is that we don’t see them coming, so we don’t plan for them.

If this year has taught us anything, it’s the importance of setting aside a little extra money and leaving it there until the day comes when we might need it.

5. Slow down.

We’ve realized that not only is it OK to slow down, but it’s actually essential.