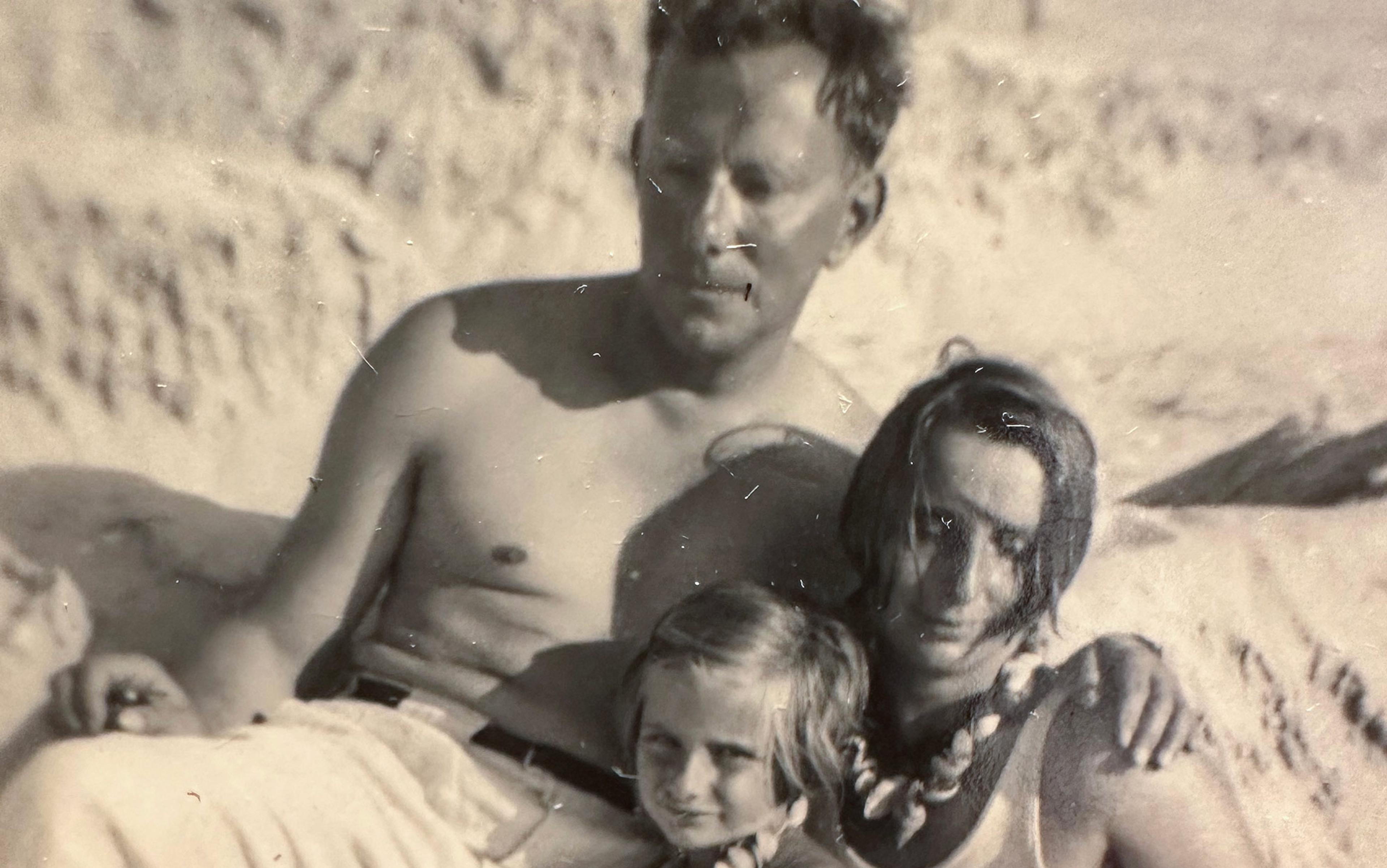

Paris, 1951. Photo by Elliot Erwitt/Magnum

Loved, yet lonely

You might have the unconditional love of family and friends and yet feel deep loneliness. can philosophy explain why.

by Kaitlyn Creasy + BIO

Although one of the loneliest moments of my life happened more than 15 years ago, I still remember its uniquely painful sting. I had just arrived back home from a study abroad semester in Italy. During my stay in Florence, my Italian had advanced to the point where I was dreaming in the language. I had also developed intellectual interests in Italian futurism, Dada, and Russian absurdism – interests not entirely deriving from a crush on the professor who taught a course on those topics – as well as the love sonnets of Dante and Petrarch (conceivably also related to that crush). I left my semester abroad feeling as many students likely do: transformed not only intellectually but emotionally. My picture of the world was complicated, my very experience of that world richer, more nuanced.

After that semester, I returned home to a small working-class town in New Jersey. Home proper was my boyfriend’s parents’ home, which was in the process of foreclosure but not yet taken by the bank. Both parents had left to live elsewhere, and they graciously allowed me to stay there with my boyfriend, his sister and her boyfriend during college breaks. While on break from school, I spent most of my time with these de facto roommates and a handful of my dearest childhood friends.

When I returned from Italy, there was so much I wanted to share with them. I wanted to talk to my boyfriend about how aesthetically interesting but intellectually dull I found Italian futurism; I wanted to communicate to my closest friends how deeply those Italian love sonnets moved me, how Bob Dylan so wonderfully captured their power. (‘And every one of them words rang true/and glowed like burning coal/Pouring off of every page/like it was written in my soul …’) In addition to a strongly felt need to share specific parts of my intellectual and emotional lives that had become so central to my self-understanding, I also experienced a dramatically increased need to engage intellectually, as well as an acute need for my emotional life in all its depth and richness – for my whole being, this new being – to be appreciated. When I returned home, I felt not only unable to engage with others in ways that met my newly developed needs, but also unrecognised for who I had become since I left. And I felt deeply, painfully lonely.

This experience is not uncommon for study-abroad students. Even when one has a caring and supportive network of relationships, one will often experience ‘reverse culture shock’ – what the psychologist Kevin Gaw describes as a ‘process of readjusting, reacculturating, and reassimilating into one’s own home culture after living in a different culture for a significant period of time’ – and feelings of loneliness are characteristic for individuals in the throes of this process.

But there are many other familiar life experiences that provoke feelings of loneliness, even if the individuals undergoing those experiences have loving friends and family: the student who comes home to his family and friends after a transformative first year at college; the adolescent who returns home to her loving but repressed parents after a sexual awakening at summer camp; the first-generation woman of colour in graduate school who feels cared for but also perpetually ‘ in-between ’ worlds, misunderstood and not fully seen either by her department members or her family and friends back home; the travel nurse who returns home to her partner and friends after an especially meaningful (or perhaps especially psychologically taxing) work assignment; the man who goes through a difficult breakup with a long-term, live-in partner; the woman who is the first in her group of friends to become a parent; the list goes on.

Nor does it take a transformative life event to provoke feelings of loneliness. As time passes, it often happens that friends and family who used to understand us quite well eventually fail to understand us as they once did, failing to really see us as they used to before. This, too, will tend to lead to feelings of loneliness – though the loneliness may creep in more gradually, more surreptitiously. Loneliness, it seems, is an existential hazard, something to which human beings are always vulnerable – and not just when they are alone.

In his recent book Life Is Hard (2022), the philosopher Kieran Setiya characterises loneliness as the ‘pain of social disconnection’. There, he argues for the importance of attending to the nature of loneliness – both why it hurts and what ‘that pain tell[s] us about how to live’ – especially given the contemporary prevalence of loneliness. He rightly notes that loneliness is not just a matter of being isolated from others entirely, since one can be lonely even in a room full of people. Additionally, he notes that, since the negative psychological and physiological effects of loneliness ‘seem to depend on the subjective experience of being lonely’, effectively combatting loneliness requires us to identify the origin of this subjective experience.

S etiya’s proposal is that we are ‘social animals with social needs’ that crucially include needs to be loved and to have our basic worth recognised. When we fail to have these basic needs met, as we do when we are apart from our friends, we suffer loneliness. Without the presence of friends to assure us that we matter, we experience the painful ‘sensation of hollowness, of a hole in oneself that used to be filled and now is not’. This is loneliness in its most elemental form. (Setiya uses the term ‘friends’ broadly, to include close family and romantic partners, and I follow his usage here.)

Imagine a woman who lands a job requiring a long-distance move to an area where she knows no one. Even if there are plenty of new neighbours and colleagues to greet her upon her arrival, Setiya’s claim is that she will tend to experience feelings of loneliness, since she does not yet have close, loving relationships with these people. In other words, she will tend to experience feelings of loneliness because she does not yet have friends whose love of her reflects back to her the basic value as a person that she has, friends who let her see that she matters. Only when she makes genuine friendships will she feel her unconditional value is acknowledged; only then will her basic social needs to be loved and recognised be met. Once she feels she truly matters to someone, in Setiya’s view, her loneliness will abate.

Setiya is not alone in connecting feelings of loneliness to a lack of basic recognition. In The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), for example, Hannah Arendt also defines loneliness as a feeling that results when one’s human dignity or unconditional worth as a person fails to be recognised and affirmed, a feeling that results when this, one of the ‘basic requirements of the human condition’, fails to be met.

These accounts get a good deal about loneliness right. But they miss something as well. On these views, loving friendships allow us to avoid loneliness because the loving friend provides a form of recognition we require as social beings. Without loving friendships, or when we are apart from our friends, we are unable to secure this recognition. So we become lonely. But notice that the feature affirmed by the friend here – my unconditional value – is radically depersonalised. The property the friend recognises and affirms in me is the same property she recognises and affirms in her other friendships. Otherwise put, the recognition that allegedly mitigates loneliness in Setiya’s view is the friend’s recognition of an impersonal, abstract feature of oneself, a quality one shares with every other human being: her unconditional worth as a human being. (The recognition given by the loving friend is that I ‘[matter] … just like everyone else.’)

Just as one can feel lonely in a room full of strangers, one can feel lonely in a room full of friends

Since my dignity or worth is disconnected from any particular feature of myself as an individual, however, my friend can recognise and affirm that worth without acknowledging or engaging my particular needs, specific values and so on. If Setiya is calling it right, then that friend can assuage my loneliness without engaging my individuality.

Or can they? Accounts that tie loneliness to a failure of basic recognition (and the alleviation of loneliness to love and acknowledgement of one’s dignity) may be right about the origin of certain forms of loneliness. But it seems to me that this is far from the whole picture, and that accounts like these fail to explain a wide variety of familiar circumstances in which loneliness arises.

When I came home from my study-abroad semester, I returned to a network of robust, loving friendships. I was surrounded daily by a steadfast group of people who persistently acknowledged and affirmed my unconditional value as a person, putting up with my obnoxious pretension (so it must have seemed) and accepting me even though I was alien in crucial ways to the friend they knew before. Yet I still suffered loneliness. In fact, while I had more close friendships than ever before – and was as close with friends and family members as I had ever been – I was lonelier than ever. And this is also true of the familiar scenarios from above: the first-year college student, the new parent, the travel nurse, and so on. All these scenarios are ripe for painful feelings of loneliness even though the individuals undergoing such experiences have a loving network of friends, family and colleagues who support them and recognise their unconditional value.

So, there must be more to loneliness than Setiya’s account (and others like it) let on. Of course, if an individual’s worth goes unrecognised, she will feel awfully lonely. But just as one can feel lonely in a room full of strangers, one can feel lonely in a room full of friends. What plagues accounts that tie loneliness to an absence of basic recognition is that they fail to do justice to loneliness as a feeling that pops up not only when one lacks sufficiently loving, affirmative relationships, but also when one perceives that the relationships she has (including and perhaps especially loving relationships) lack sufficient quality (for example, lacking depth or a desired feeling of connection). And an individual will perceive such relationships as lacking sufficient quality when her friends and family are not meeting the specific needs she has, or recognising and affirming her as the particular individual that she is.

We see this especially in the midst or aftermath of transitional and transformational life events, when greater-than-usual shifts occur. As the result of going through such experiences, we often develop new values, core needs and centrally motivating desires, losing other values, needs and desires in the process. In other words, after undergoing a particularly transformative experience, we become different people in key respects than we were before. If after such a personal transformation, our friends are unable to meet our newly developed core needs or recognise and affirm our new values and central desires – perhaps in large part because they cannot , because they do not (yet) recognise or understand who we have become – we will suffer loneliness.

This is what happened to me after Italy. By the time I got back, I had developed new core needs – as one example, the need for a certain level and kind of intellectual engagement – which were unmet when I returned home. What’s more, I did not think it particularly fair to expect my friends to meet these needs. After all, they did not possess the conceptual frameworks for discussing Russian absurdism or 13th-century Italian love sonnets; these just weren’t things they had spent time thinking about. And I didn’t blame them; expecting them to develop or care about developing such a conceptual framework seemed to me ridiculous. Even so, without a shared framework, I felt unable to meet my need for intellectual engagement and communicate to my friends the fullness of my inner life, which was overtaken by quite specific aesthetic values, values that shaped how I saw the world. As a result, I felt lonely.

I n addition to developing new needs, I understood myself as having changed in other fundamental respects. While I knew my friends loved me and affirmed my unconditional value, I did not feel upon my return home that they were able to see and affirm my individuality. I was radically changed; in fact, I felt in certain respects totally unrecognisable even to those who knew me best. After Italy, I inhabited a different, more nuanced perspective on the world; beauty, creativity and intellectual growth had become core values of mine; I had become a serious lover of poetry; I understood myself as a burgeoning philosopher. At the time, my closest friends were not able to see and affirm these parts of me, parts of me with which even relative strangers in my college courses were acquainted (though, of course, those acquaintances neither knew me nor were equipped to meet other of my needs which my friends had long met). When I returned home, I no longer felt truly seen by my friends .

One need not spend a semester abroad to experience this. For example, a nurse who initially chose her profession as a means to professional and financial stability might, after an especially meaningful experience with a patient, find herself newly and centrally motivated by a desire to make a difference in her patients’ lives. Along with the landscape of her desires, her core values may have changed: perhaps she develops a new core value of alleviating suffering whenever possible. And she may find certain features of her job – those that do not involve the alleviation of suffering, or involve the limited alleviation of suffering – not as fulfilling as they once were. In other words, she may have developed a new need for a certain form of meaningful difference-making – a need that, if not met, leaves her feeling flat and deeply dissatisfied.

Changes like these – changes to what truly moves you, to what makes you feel deeply fulfilled – are profound ones. To be changed in these respects is to be utterly changed. Even if you have loving friendships, if your friends are unable to recognise and affirm these new features of you, you may fail to feel seen, fail to feel valued as who you really are. At that point, loneliness will ensue. Interestingly – and especially troublesome for Setiya’s account – feelings of loneliness will tend to be especially salient and painful when the people unable to meet these needs are those who already love us and affirm our unconditional value.

Those with a strong need for their uniqueness to be recognised may be more disposed to loneliness

So, even with loving friends, if we perceive ourselves as unable to be seen and affirmed as the particular people we are, or if certain of our core needs go unmet, we will feel lonely. Setiya is surely right that loneliness will result in the absence of love and recognition. But it can also result from the inability – and sometimes, failure – of those with whom we have loving relationships to share or affirm our values, to endorse desires that we understand as central to our lives, and to satisfy our needs.

Another way to put it is that our social needs go far beyond the impersonal recognition of our unconditional worth as human beings. These needs can be as widespread as a need for reciprocal emotional attachment or as restricted as a need for a certain level of intellectual engagement or creative exchange. But even when the need in question is a restricted or uncommon one, if it is a deep need that requires another person to meet yet goes unmet, we will feel lonely. The fact that we suffer loneliness even when these quite specific needs are unmet shows that understanding and treating this feeling requires attending not just to whether my worth is affirmed, but to whether I am recognised and affirmed in my particularity and whether my particular, even idiosyncratic social needs are met by those around me.

What’s more, since different people have different needs, the conditions that produce loneliness will vary. Those with a strong need for their uniqueness to be recognised may be more disposed to loneliness. Others with weaker needs for recognition or reciprocal emotional attachment may experience a good deal of social isolation without feeling lonely at all. Some people might alleviate loneliness by cultivating a wide circle of not-especially-close friends, each of whom meets a different need or appreciates a different side of them. Yet others might persist in their loneliness without deep and intimate friendships in which they feel more fully seen and appreciated in their complexity, in the fullness of their being.

Yet, as ever-changing beings with friends and loved ones who are also ever-changing, we are always susceptible to loneliness and the pain of situations in which our needs are unmet. Most of us can recall a friend who once met certain of our core social needs, but who eventually – gradually, perhaps even imperceptibly – ultimately failed to do so. If such needs are not met by others in one’s life, this situation will lead one to feel profoundly, heartbreakingly lonely.

In cases like these, new relationships can offer true succour and light. For example, a lonely new parent might have childless friends who are clueless to the needs and values she develops through the hugely complicated transition to parenthood; as a result, she might cultivate relationships with other new parents or caretakers, people who share her newly developed values and better understand the joys, pains and ambivalences of having a child. To the extent that these new relationships enable her needs to be met and allow her to feel genuinely seen, they will help to alleviate her loneliness. Through seeking relationships with others who might share one’s interests or be better situated to meet one’s specific needs, then, one can attempt to face one’s loneliness head on.

But you don’t need to shed old relationships to cultivate the new. When old friends to whom we remain committed fail to meet our new needs, it’s helpful to ask how to salvage the situation, saving the relationship. In some instances, we might choose to adopt a passive strategy, acknowledging the ebb and flow of relationships and the natural lag time between the development of needs and others’ abilities to meet them. You could ‘wait it out’. But given that it is much more difficult to have your needs met if you don’t articulate them, an active strategy seems more promising. To position your friend to better meet your needs, you might attempt to communicate those needs and articulate ways in which you don’t feel seen.

Of course, such a strategy will be successful only if the unmet needs provoking one’s loneliness are needs one can identify and articulate. But we will so often – perhaps always – have needs, desires and values of which we are unaware or that we cannot articulate, even to ourselves. We are, to some extent, always opaque to ourselves. Given this opacity, some degree of loneliness may be an inevitable part of the human condition. What’s more, if we can’t even grasp or articulate the needs provoking our loneliness, then adopting a more passive strategy may be the only option one has. In cases like this, the only way to recognise your unmet needs or desires is to notice that your loneliness has started to lift once those needs and desires begin to be met by another.

Family life

A patchwork family

After my marriage failed, I strove to create a new family – one made beautiful by the loving way it’s stitched together

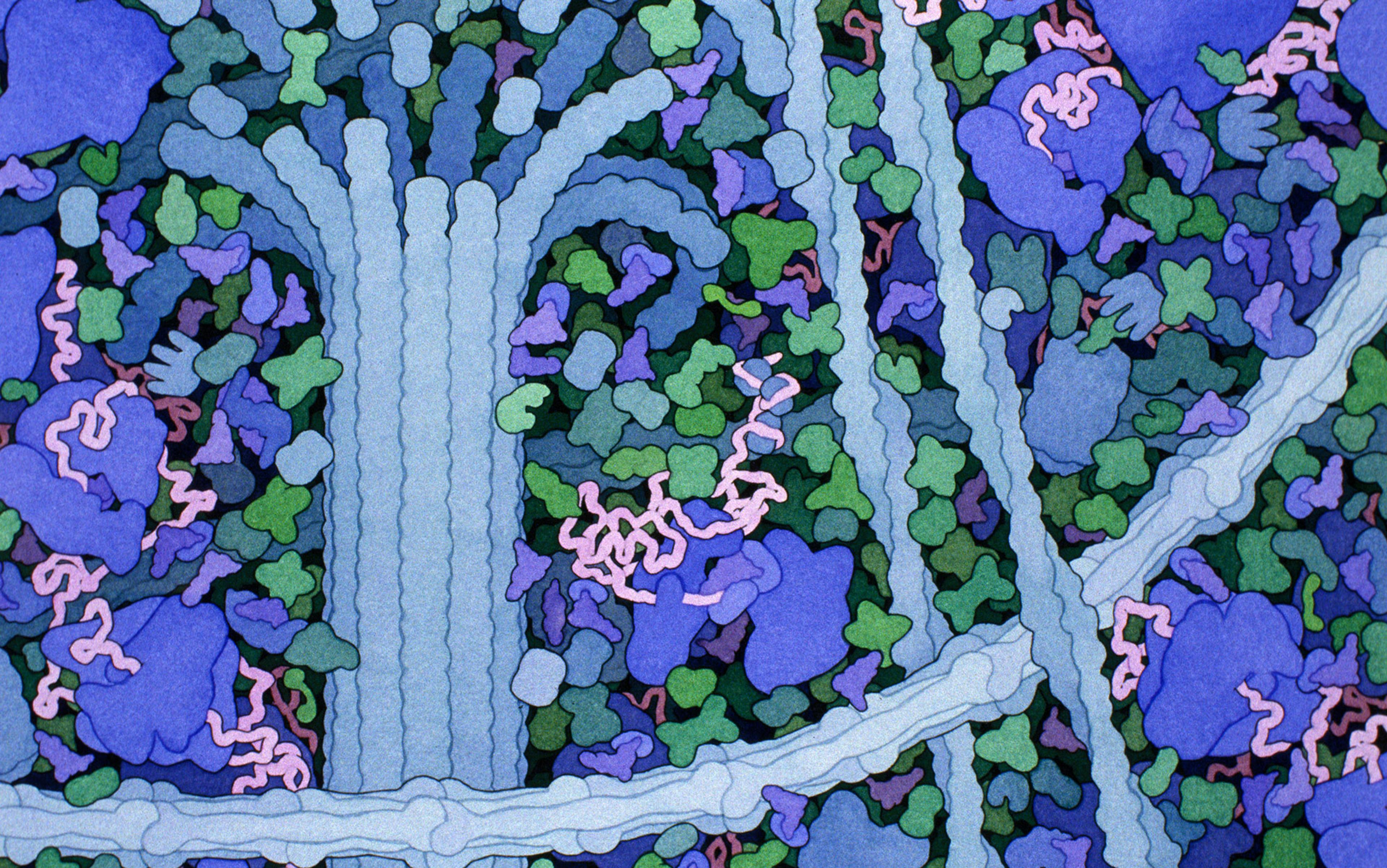

The cell is not a factory

Scientific narratives project social hierarchies onto nature. That’s why we need better metaphors to describe cellular life

Charudatta Navare

Stories and literature

Terrifying vistas of reality

H P Lovecraft, the master of cosmic horror stories, was a philosopher who believed in the total insignificance of humanity

Sam Woodward

The dangers of AI farming

AI could lead to new ways for people to abuse animals for financial gain. That’s why we need strong ethical guidelines

Virginie Simoneau-Gilbert & Jonathan Birch

Thinkers and theories

A man beyond categories

Paul Tillich was a religious socialist and a profoundly subtle theologian who placed doubt at the centre of his thought

Public health

It’s dirty work

In caring for and bearing with human suffering, hospital staff perform extreme emotional labour. Is there a better way?

Susanna Crossman

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Of Mice and Men — The Theme of Loneliness in Of Mice and Men

Analysis of Characters' Loneliness in of Mice and Men

- Categories: Loneliness Of Mice and Men

About this sample

Words: 1842 |

10 min read

Published: May 5, 2022

Words: 1842 | Pages: 4 | 10 min read

The essay delves into the poignant theme of loneliness depicted in John Steinbeck's novella "Of Mice and Men", notably through the characters of George Milton and Crooks. Loneliness, an emotionally desolate experience, is represented as a complex and potent emotion capable of inducing behavioral outbursts and altering characters' outlooks and behaviors. George, bound by obligation and genuine care for Lennie, experiences a unique solitude, being physically accompanied yet emotionally isolated due to Lennie’s mental condition. Crooks, isolated due to racial discrimination, shelters his vulnerability behind a wall of bitterness and emotional hardness, demonstrating how pervasive loneliness can twist personalities and moral compasses. The essay elucidates how such emotional solitude not only significantly influences the characters’ behaviors and mental states but also spotlights the harsh, discriminative societal backdrop, highlighting the varying, profound impacts loneliness imposes on individuals.

Table of contents

Introduction, loneliness in of mice and men, george milton, curley’s wife.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 953 words

2 pages / 881 words

2 pages / 741 words

2 pages / 887 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Of Mice and Men

John Steinbeck’s novel and poignant exploration of friendship, dreams, and the harsh realities of the Great Depression. One of the key literary devices that Steinbeck uses to convey the tragic and inevitable nature of the story [...]

In John Steinbeck's classic novel, "Of Mice and Men," the theme of companionship is woven throughout the narrative, highlighting the importance of human connection in a world marked by isolation and hardship. From the unlikely [...]

Novella Of Mice and Men presents a complex and multifaceted character in the form of Curley's wife. Throughout the story, she is often portrayed as a villainous figure, but a closer analysis reveals a more nuanced [...]

John Steinbeck’s novel, Of Mice and Men, explores the theme of isolation and loneliness through the experiences of its characters. Set during the Great Depression in California, the novel follows the journey of two migrant [...]

Of Mice and Men is a classic novel taking place during the 1930s. The main characters are two migrant farmers, George and Lennie. They end up working at a farm out in California where they attempt to make enough cash to buy [...]

Throughout John Steinbeck’s novel, Of Mice and Men, the author depicts many characters such as Lennie, Candy, Crooks, etc. as having physical or mental impairments. These “disadvantaged” characters quickly become to represent [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Essaying the pop culture that matters since 1999

Photo by aronoeleinilotta ( Pixabay License / Pixabay )

Short Stories: Solitude and Loneliness

Five short stories—by Anton Chekhov, Katherine Mansfield, Bharati Mukherjee, Anthony Doerr, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie—explore various isolation, solitude, and loneliness pathologies from the perspectives of different lives and cultures.

During these times, many writers, artists, and public figures have taken to sharing their lockdown diaries or pandemic reading lists or advice on how to survive isolation . Thanks to this ongoing spate of articles and essays in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, we are well aware that solitude and loneliness are not synonymous words .

The respective histories of these two modes of being also show us that solitude is more about an autonomously-chosen, self-reflective time with oneself, while loneliness is about an undesired and imposed lack of connection with the world around us. Solitude is often a privilege while loneliness is seen as a curse. All that said, being unhappy while alone is a fairly modern idea . And, during these times of social distancing, a good number of us are working to understand and leverage our own isolation pathologies better.

The five short stories here—by Anton Chekhov, Katherine Mansfield, Bharati Mukherjee, Anthony Doerr, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie—explore some of these isolation, solitude, and loneliness pathologies from the perspectives of different lives and cultures. Almost all of them have had solitude or loneliness thrust upon them (not due to any pandemic-like situations) and are trying to cope as best they can. As always, fiction allows us to look at aspects of human nature that we are often unwilling to face within ourselves or in our loved ones. What the characters in these stories experience and how they respond to their isolationary solitude or loneliness allows us certain deeper insights that are, at once, both familiar and eye-opening.

“The Bet”, by Anton Chekhov (translated by Constance Garnett)

In Chekhov’s short story “ The Bet “, a banker and a lawyer make a bet with each other about whether death is better than life in prison. As morbid as this sounds, this story explores more than the usual debate of capital punishment versus life imprisonment. To fulfill the bet’s conditions and win two million rubles from the banker, the young lawyer must live in total isolation for 15 years. The only contact he is allowed with the rest of the world is through letters.The story doesn’t progress as we might expect. But this is Chekhov, so we must put our expectations aside and let him take us on a journey with the evolution of these two characters. Whichever side of the fence we might be with this never-ending debate, it makes us question our beliefs and values while reading.

From a craft perspective, this is classic Chekhov. Even while exploring matters of life and death, there is no moral teaching or didactic personal opinion here. Like the doctor that he was in real life, he probes, diagnoses, and presents every important detail. The prognosis is ours to make as readers. And though the story is written to appeal to the intellect more so than to emotions, Chekhov’s mastery of showing versus telling is always a delight to savor.

Then he remembered what followed that evening. It was decided that the young man should spend the years of his captivity under the strictest supervision in one of the lodges in the banker’s garden. It was agreed that for fifteen years he should not be free to cross the threshold of the lodge, to see human beings, to hear the human voice, or to receive letters and newspapers. He was allowed to have a musical instrument and books, and was allowed to write letters, to drink wine, and to smoke. By the terms of the agreement, the only relations he could have with the outer world were by a little window made purposely for that object. He might have anything he wanted—books, music, wine, and so on—in any quantity he desired by writing an order, but could only receive them through the window.

“Miss Brill”, by Katherine Mansfield

Image by monica1607 ( Pixabay License / Pixabay )

Several of Katherine Mansfield’s short stories feature solitary, lonely women. The title character of “ Miss Brill ” is so beautifully and heartbreakingly portrayed that she has become a timeless literary archetype. Almost the entire story takes place on a park bench. And yet, Mansfield depicts the entire life of this singular character so effectively that we feel we know her as intimately as her writer. There is not one superfluous detail and every sentence builds the story, mood, drama, and emotions in the precise, signature Mansfield manner. Even the seemingly excessive use of metaphors and similes serve important purposes if we read close enough.

As Miss Brill sits in her “special seat”, she observes the people around her with a careful, acute curiosity. We’re deep in her point of view so we get to see, feel, hear, think, and sense her precise impressions of all the interactions teeming around her. But her illusions and delusions are thrown into sharp contrast with the twist ending that’s so brilliantly foreshadowed through all her own judging and romanticizing of others and herself.

Although it was so brilliantly fine—the blue sky powdered with gold and great spots of light like white wine splashed over the Jardins Publiques—Miss Brill was glad that she had decided on her fur. The air was motionless, but when you opened your mouth, there was just a faint chill, like a chill from a glass of iced water before you sip, and now and again a leaf came drifting—from nowhere, from the sky. Miss Brill put up her hand and touched her fur. Dear little thing! It was nice to feel it again.

“The Management of Grief”, by Bharati Mukherjee

The New York Times headlined Bharati Mukherjee’s obituary with the label “writer of immigrant life”. She was certainly that. But she also tackled much more with her writing. Often, such labels are too reductive and they put readers off. Jhumpa Lahiri’s clapback at the New York Times when she was called an immigrant writer remains the best response yet: “If certain books are to be termed immigrant fiction, what do we call the rest? Native fiction? Puritan fiction? This distinction doesn’t agree with me. Given the history of the United States, all American fiction could be classified as immigrant fiction.”

So, while Mukherjee’s “ The Management of Grief ” features Indian immigrants in the US, it’s about a lot more: a woman’s sense of isolation after losing her entire family in a mass tragedy and being surrounded by well-wishers and do-gooders; how communities and individuals deal with loss; how racism and justice play big roles in social acceptance; and how cultural traditions and customs, in the end, are of little help with personal grief.

Having already written an investigative account of the 1985 Air India flight 182 disaster with her husband, Dr Clark Blaise, (see The Sorrow and the Terror ; Penguin Books; September 1987) Mukherjee wrote this short story in one sitting. In a PowellsBook.blog interview , she recalls how she could have been on that fateful flight herself.

Mukherjee’s craft is sharp here as she reveals bits of information through the protagonist’s experiences and observations. We, as readers, begin to piece the tragedy together as Shaila tries to make sense of what has happened. Also, for a lot of readers, this well-anthologized story is their first introduction to this huge disaster that history texts often ignore.

A woman I don’t know is boiling tea the Indian way in my kitchen. There are a lot of women I don’t know in my kitchen, whispering and moving tactfully. They open doors, rummage through the pantry, and try not to ask me where things are kept. They remind me of when my sons were small, on Mother’s Day or when Vikram and I were tired, and they would make big, sloppy omelets. I would lie in bed pretending I didn’t hear them.

“The Deep”, by Anthony Doerr

“ The Deep ” won the 2011 Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award—the biggest award in the world for this literary form. Doerr is a much-celebrated writer, well-known for both his novels and his short stories. This story was also anthologized in the New American Stories (Vintage Contemporaries; July 2015; edited by Ben Marcus.)

Death features strongly in this story as well because the protagonist, Tom, is diagnosed with a terminal illness at a very young age. Due to this life-threatening condition, he’s forced to lead a mostly reclusive kind of life until he meets Ruby at school. Ruby takes risks and gets him to sneak away with her to experience the little pleasures of life that his mother has, until then, protected him from. After they’ve gone their separate ways, Tom settles into a safe routine existence. Until he and Ruby meet again as adults.

Rather than giving us a formulaic story of unrequited love, Doerr goes, well, deeper. He shows Tom struggling with choosing how to live his life even as he manages to live past the age his doctor had predicted. In the last scene, when Tom shares his big epiphany with Ruby, Doerr avoids the many possible clichés and has our hearts aching for these two people trying to somehow connect, comfort, console each other.

Where Doerr’s storytelling craft shines is in the cinematically beautiful contrasts of Tom’s life before, with, and after Ruby. The story is set in 1914 Detroit, during the Great Depression and Doerr’s historically accurate details of how exactly the world around them is falling apart are notable too.

You can see actor Damian Lewis, reading an excerpt of this story here .

Tom is born in 1914 in Detroit, a quarter mile from International Salt. His father is offstage, unaccounted for. His mother operates a six-room, under-insulated boarding house populated with locked doors, behind which drowse the grim possessions of itinerant salt workers: coats the colors of mice, tattered mucking boots, aquatints of undressed women, their breasts faded orange. Every six months a miner is laid off, gets drafted, or dies, and is replaced by another, so that very early in his life Tom comes to see how the world continually drains itself of young men, leaving behind only objects—empty tobacco pouches, bladeless jackknives, salt-caked trousers—mute, incapable of memory.

“New Husband”, by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

“ New Husband ” was published in The Iowa Review in 2003 under this title and then in Adichie ‘s short story collection, The Thing Around Your Neck (Anchor; June 2010) as ‘The Arrangers of Marriage’.

A newly-married woman from Lagos, Chinaza, joins her immigrant husband in New York. They barely know each other due to their arranged marriage. As she tries to adjust to both him and her new world, she deals with the inevitable sense of isolation and loneliness. And, while this might read on the surface like yet another immigrant story, it is also much more than that.

While her husband encourages assimilation into American culture, he discourages any ties back with their culture back home. Almost every impression or ideal Chinaza has of America, the land of opportunity and dreams, slowly crumbles on a daily basis as she tries to understand and accept her confusing reality. It is a lonely struggle because her husband, who likely went through his own assimilation challenges when he first moved to the US, can no longer appreciate or sympathize with what she’s going through.

Adichie adds a twist in the story that we’ll leave unrevealed. It’s not entirely unexpected when it surfaces but it does force Chinaza to make a decision, one way or another. That big decision is also inevitable because of how Adichie foreshadows it carefully. The symbolism of the opening door in the final lines is, of course, perfection.

My new husband carried the suitcase out of the taxi and led the way into the brownstone building, up a flight of brooding stairs, down an airless hallway with frayed carpeting and stopped at a door. 5D, unevenly fashioned from yellowish metal, was plastered on it. “We’re here,” he said. He had always used the word ‘house’ when he told me about our home. I had imagined a gravelly driveway snaking between cucumber-colored lawns, a wide doorway that he would carry me over, walls with serene paintings. Like the white newlyweds in the American films that Lagos Channel 5 showed on Saturday nights.

- Short Stories: Characters Inspired by People in Politics - PopMatters

- Chronicling the Non-Event: Anton Chekhov and the Short Story ...

- Short Stories: Women in the Workplace - PopMatters

- Junot Díaz's Favorite Short Stories: the Future of American Literature ...

- The Penguin Book of Italian Short Stories (review) - PopMatters

- 'The Penguin Book of Japanese Short Stories' Is a Perfect Balance ...

- Short Stories: Souvenirs - PopMatters

- Short Stories: The 12 Best Collections of 2018

- Short Stories: American Writers of South Asian Origin - PopMatters

- Short Stories: Refugees - PopMatters

- The Human Animal in Natural Labitat: A Brief Study of the Outcast - PopMatters

Publish with PopMatters

PopMatters Seeks Book Critics and Essayists

Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered – FILM Winter 2023-24

Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered – MUSIC Winter 2023-24

Submit an Essay, Review, Interview, or List to PopMatters

PopMatters Seeks Music Writers

- Free Case Studies

- Business Essays

Write My Case Study

Buy Case Study

Case Study Help

- Case Study For Sale

- Case Study Service

- Hire Writer

Loneliness Narrative Essay

Loneliness is not something anybody wants. Feeling lonely is like being empty with no way of food or drink.

Most people live their lives and end up happy with a nice family friends and an entire community of people that they can say are their friends. But there are the rare cases of people that don’t either communicate that well or just are not people persons. This feeling of being lonely can cause great amounts of stress and depression. Of mice and men showed what loneliness can do to a person. Lennie was never actually alone physically, but he knew that he had nothing to hold onto or to live for. Teenage loneliness is a very serious problem.

We Will Write a Custom Case Study Specifically For You For Only $13.90/page!

During the teenage years kids are learning how to interact, make friends and be active, participate in events. A lot of teenagers stride to be the most popular, or to be known by everybody which is not always a good thing but it is better than being lonely. Teenagers tend to be bully’s and pick on other kids and embarrass them. That makes it harder for a child to branch out and meet people. The whole idea of going to school is not only to get an education that will last you all of your life, but also to make friends that will last you all of your life.

Lennie was a very big strong man. He was a migrant worker with not a bright though in his head. He had a very big heart and was compassionate but had a problem with hurting things. His right hand man George was a smaller man but had a sense of how things work and knew what he needed to do to survive in the world and make things happen. But every time George would make a move to help himself and Lennie out, Lennie always found a way to mess it up. Lennie had a mouse that was on of the closest things that he had to a friend.

He didn’t even harm it first. The mouse was soft and gentle with Lennie so he was soft and gentle back. But Lennie was departed from his only friend when his partner George made him get rid of it. Although teenagers being lonely now a days, and grown man being lonely in past times are very different and not alike. Loneliness is the same no matter who is going through it. Everybody comes from somewhere.

We can’t all get along with everybody but the people that we can get along with we should. Because going crazy because you haven’t talked to anybody. There is no way you can get around it. My outtake on loneliness is that you are only lonely if you want to be. Nobody makes you be by yourself, it might be what you need to do at the moment but not where you need to stay in life.

Every body needs somebody and if you are a lonely person you should walk outside and make new friends.

Related posts:

- Loneliness and Companionship by John Steinbeck

- Loneliness Free Essay Sample

- Loneliness Within

- The War of Loneliness

- America's Loneliness

- What Causes Loneliness in People?

Quick Links

Privacy Policy

Terms and Conditions

Testimonials

Our Services

Case Study Writing Service

Case Studies For Sale

Our Company

Welcome to the world of case studies that can bring you high grades! Here, at ACaseStudy.com, we deliver professionally written papers, and the best grades for you from your professors are guaranteed!

[email protected] 804-506-0782 350 5th Ave, New York, NY 10118, USA

Acasestudy.com © 2007-2019 All rights reserved.

Hi! I'm Anna

Would you like to get a custom case study? How about receiving a customized one?

Haven't Found The Case Study You Want?

For Only $13.90/page

Theme of Loneliness, Isolation, & Alienation in Literature with Examples

Humans are social creatures. Most of us enjoy communication and try to build relationships with others. It’s no wonder that the inability to be a part of society often leads to emotional turmoil.

Our specialists will write a custom essay specially for you!

World literature has numerous examples of characters who are disconnected from their loved ones or don’t fit into the social norms. Stories featuring themes of isolation and loneliness often describe a quest for happiness or explore the reasons behind these feelings.

In this article by Custom-Writing.org , we will:

- discuss isolation and loneliness in literary works;

- cite many excellent examples;

- provide relevant quotations.

🏝️ Isolation Theme in Literature

- 🏠 Theme of Loneliness

- 👽 Theme of Alienation

- Frankenstein

- The Metamorphosis

- Of Mice and Men

- ✍️ Essay Topics

🔍 References

Isolation is a state of being detached from other people, either physically or emotionally. It may have positive and negative connotations:

- In a positive sense, isolation can be a powerful source of creativity and independence.

- In negative terms , it can cause mental suffering and difficulties with interpersonal relationships.

Theme of Isolation and Loneliness: Difference

As you can see, isolation can be enjoyable in certain situations. That’s how it differs from loneliness : a negative state in which a person feels uncomfortable and emotionally down because of a lack of social interactions . In other words, isolated people are not necessarily lonely.

Isolation Theme Characteristics with Examples

Now, let’s examine isolation as a literary theme. It often appears in stories of different genres and has various shades of meaning. We’ll explain the different uses of this theme and provide examples from literature.

Just in 1 hour! We will write you a plagiarism-free paper in hardly more than 1 hour

Forced vs. Voluntary Isolation in Literature

Isolation can be voluntary or happen for external reasons beyond the person’s control. The main difference lies in the agent who imposes isolation on the person:

- If someone decides to be alone and enjoys this state of solitude, it’s voluntary isolation . The poetry of Emily Dickinson is a prominent example.

- Forced isolation often acts as punishment and leads to detrimental emotional consequences. This form of isolation doesn’t depend on the character’s will, such as in Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter .

Physical vs. Emotional Isolation in Literature

Aside from forced and voluntary, isolation can be physical or emotional:

- Isolation at the physical level makes the character unable to reach out to other people, such as Robinson Crusoe being stranded on an island.

- Emotional isolation is an inner state of separation from other people. It also involves unwillingness or inability to build quality relationships. A great example is Holden Caulfield from The Catcher in the Rye .

These two forms are often interlinked, like in A Rose for Emily . The story’s titular character is isolated from the others both physically and emotionally .

Symbols of Isolation in Literature

In literary works dedicated to emotional isolation, authors often use physical artifacts as symbols. For example, the moors in Wuthering Heights or the room in The Yellow Wallpaper are means of the characters’ physical isolation. They also symbolize a much deeper divide between the protagonists and the people around them.

🏠 Theme of Loneliness in Literature

Loneliness is often used as a theme in stories of people unable to build relationships with others. Their state of mind always comes with sadness and a low self-esteem. Naturally, it causes profound emotional suffering.

Receive a plagiarism-free paper tailored to your instructions. Cut 20% off your first order!

We will examine how the theme of loneliness functions in literature. But first, let’s see how it differs from its positive counterpart: solitude.

Solitude vs. Loneliness: The Difference

Loneliness theme: history & examples.

The modern concept of loneliness is relatively new. It first emerged in the 16 th century and has undergone many transformations since then.

- The first formal mention of loneliness appeared in George Milton’s Paradise Lost in the 17 th century. There are also many references to loneliness in Shakespeare’s works.

- Later on, after the Industrial Revolution , the theme got more popular. During that time, people started moving to large cities. As a result, they were losing bonds with their families and hometowns. Illustrative examples of that period are Gothic novels and the works of Charles Dickens .

- According to The New Yorker , the 20 th century witnessed a broad spread of loneliness due to the rise of Capitalism. Philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus explored existential loneliness, influencing numerous authors. The absurdist writings of Kafka and Beckett also played an essential role in reflecting the isolation felt by people in Capitalist societies. Sylvia Plath has masterfully explored mental health struggles related to this condition in The Bell Jar (you can learn more about it in our The Bell Jar analysis .)

👽 Theme of Alienation in Literature

Another facet of being alone that is often explored in literature is alienation . Let’s see how this concept differs from those we discussed previously.

Alienation vs. Loneliness: Difference

While loneliness is more about being on your own and lacking connection, alienation means involuntary estrangement and a lack of sympathy from society. In other words, alienated people don’t fit their community, thus lacking a sense of belonging.

Isolation vs. Alienation: The Difference

Theme of alienation vs. identity in literature.

There is a prominent connection between alienation and a loss of identity. It often results from a character’s self-search in a hostile society with alien ideas and values. These characters often differ from the dominant majority, so the community treats them negatively. Such is the case with Mrs. Dalloway from Woolf’s eponymous novel.

Get an originally-written paper according to your instructions!

Writers with unique, non-conforming identity are often alienated during their lifetime. Their distinct mindset sets them apart from their social circle. Naturally, it creates discomfort and relationship problems. These experiences are often reflected in their works, such as in James Joyce’s semi-autobiographical A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man .

Alienation in Modernism

Alienation as a theme is mainly associated with Modernism . It’s not surprising, considering that the 20 th century witnessed fundamental changes in people’s lifestyle. Capitalism and the Industrial Revolution couldn’t help eroding the quality of human bonding and the depth of relationships.

It’s also vital to mention that the two World Wars introduced even greater changes in human relationships. People got more locked up emotionally in order to withstand the war trauma and avoid further turmoil. Consequently, the theme of alienation and comradeship found reflection in the works of Ernest Hemingway , Erich Maria Remarque , Norman Mailer, and Rebecca West, among others.

📚 Books about Loneliness and Isolation: Quotes & Examples

Loneliness and isolation themes are featured prominently in many of the world’s greatest literary works. Here we’ll analyze several well-known examples: Frankenstein, Of Mice and Men, and The Metamorphosis.

Theme of Isolation & Alienation in Frankenstein

Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein is among the earliest depictions of loneliness in modern literature. It shows the depth of emotional suffering that alienation can impose.

Victor Frankenstein , a talented scientist, creates a monster from the human body parts. The monster becomes the loneliest creature in the world. Seeing that his master hates him and wouldn’t become his friend, he ruined everything Victor held dear. He was driven by revenge, trying to drive him into the same despair.

The novel contains many references to emotional and physical alienation. It also explores the distinction between voluntary and involuntary isolation:

- The monster is involuntarily driven into an emotionally devastating state of alienation.

- Victor imposes voluntary isolation on himself after witnessing the crimes of his creature.

To learn more about the representation of loneliness and isolation in the novel, check out our article on themes in Frankenstein .

Frankenstein Quotes about Isolation

Here are a couple of quotes from Frankenstein directly related to the theme of isolation and loneliness:

How slowly the time passes here, encompassed as I am by frost and snow…I have one want which I have never yet been able to satisfy and the absence of the object of which I now feel as a most severe evil. I have no friend. Frankenstein , Letter 2

In this quote, Walton expresses his loneliness and desire for company. He uses frost and snow as symbols to refer to his isolation. Perhaps a heart-warming relationship could melt the ice surrounding him.

I believed myself totally unfitted for the company of strangers. Frankenstein , Chapter 3

This quote is related to Victor’s inability to make friends and function as a regular member of society. He also misses his friends and relatives in Ingolstadt, which causes him further discomfort.

I, who had ever been surrounded by amiable companions, continually engaged in endeavouring to bestow mutual pleasure—I was now alone. Frankenstein , Chapter 3

In this quote, Victor shares his fear of loneliness. As a person who used to spend most of his time in social activity among people, Victor feared the solitude that awaited him in Ingolstadt.

Isolation & Alienation in The Metamorphosis

The Metamorphosis is an enigmatic masterpiece by Franz Kafka, telling a story of a young man Gregor. He is alienated at work and home by his demanding, disrespectful family. He lacks deep, rewarding relationships in his life. As a result, he feels profound loneliness.

Gregor’s family isolates him both as a human and an insect, refusing to recognize his personhood. Gregor’s stay in confinement is also a reflection of his broader alienation from society, resulting from his self-perception as a parasite. To learn more about it, feel free to read our article on themes in The Metamorphosis .

The Metamorphosis: Isolation Quotes

Let’s analyze several quotes from The Metamorphosis to see how Kafka approached the theme of isolation.

The upset of doing business is much worse than the actual business in the home office, and, besides, I’ve got the torture of traveling, worrying about changing trains, eating miserable food at all hours, constantly seeing new faces, no relationships that last or get more intimate. The Metamorphosis , Part 1

In this fragment, Gregor’s lifestyle is described with a couple of strokes. It shows that he lived an empty, superficial life without meaningful relationships.

Well, leaving out the fact that the doors were locked, should he really call for help? In spite of all his miseries, he could not repress a smile at this thought. The Metamorphosis , Part 1

This quote shows how Gregor feels isolated even before anyone else can see him as an insect. He knows that being different will inevitably affect his life and his relationships with his family. So, he prefers to confine himself to voluntary isolation instead of seeking help.

He thought back on his family with deep emotion and love. His conviction that he would have to disappear was, if possible, even firmer than his sister’s. The Metamorphosis , Part 3

This final paragraph of Kafka’s story reveals the human nature of Gregor. It also shows the depth of his suffering in isolation after turning into a vermin. He reconciles with his metamorphosis and agrees to disappear from this world. Eventually, he vanishes from his family’s troubled memories.

Theme of Loneliness in Of Mice and Men

Of Mice and Men is a touching novella by John Steinbeck examining the intricacies of laborers’ relationships on a ranch. It’s a snapshot of class and race relations that delves into the depths of human loneliness. Steinbeck shows how this feeling makes people mean, reckless, and cold.

Many characters in this story suffer from being alienated from the community:

- Crooks is ostracized because of his race, living in a separate shabby house as a misfit.

- George also suffers from forced alienation because he takes care of the mentally disabled Lennie.

- Curley’s wife is another character suffering from loneliness. This feeling drives her to despair. She seeks the warmth of human relationships in the hands of Lennie, which causes her accidental death.

Isolation Quotes: Of Mice and Men

Now, let’s analyze a couple of quotes from Of Mice and Men to see how the author approached the theme of loneliness.

Guys like us who work on ranches are the loneliest guys in the world, they ain’t got no family, they don’t belong no place. Of Mice and Men , Section 1

In this quote, Steinbeck describes several dimensions of isolation suffered by his characters:

- They are physically isolated , working on large farms where they may not meet a single person for weeks.

- They have no chances for social communication and relationship building, thus remaining emotionally isolated without a life partner.

- They can’t develop a sense of belonging to the place where they work; it’s another person’s property.

Candy looked for help from face to face. Of Mice and Men , Section 3

Candy’s loneliness on the ranch becomes highly pronounced during his conflict with Carlson. The reason is that he is an old man afraid of being “disposed of.” The episode is an in-depth look into a society that doesn’t cherish human relationships, focusing only on a person’s practical utility.

I never get to talk to nobody. I get awful lonely. Of Mice and Men , Chapter 5

This quote expresses the depth of Curley’s wife’s loneliness. She doesn’t have anyone with whom she would be able to talk, aside from her husband. Curley is also not an appropriate companion, as he treats his wife rudely and carelessly. As a result of her loneliness, she falls into deeper frustration.

✍️ Essay on Loneliness and Isolation: Topics & Ideas

If you’ve got a task to write an essay about loneliness and isolation, it’s vital to pick the right topic. You can explore how these feelings are covered in literature or focus on their real-life manifestations. Here are some excellent topic suggestions for your inspiration:

- Cross-national comparisons of people’s experience of loneliness and isolation.

- Social isolation , loneliness, and all-cause mortality among the elderly.

- Public health consequences of extended social isolation .

- Impact of social isolation on young people’s mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Connections between social isolation and depression.

- Interventions for reducing social isolation and loneliness among older people.

- Loneliness and social isolation among rural area residents.

- The effect of social distancing rules on perceived loneliness.

- How does social isolation affect older people’s functional status?

- Video calls as a measure for reducing social isolation.

- Isolation, loneliness, and otherness in Frankenstein .

- The unique combination of addiction and isolation in Frankenstein .

- Exploration of solitude in Hernan Diaz’ In the Distance .

- Artificial isolation and voluntary seclusion in Against Nature .

- Different layers of isolation in George Eliot’s Silas Marner .

- Celebration of self-imposed solitude in Emily Dickinson’s works.

- Buddhist aesthetics of solitude in Stephen Batchelor’s The Art of Solitude .

- Loneliness of childhood in Charles Dickens’s works.

- Moby-Dick : Loneliness in the struggle.

- Medieval literature about loneliness and social isolation.

Now you know everything about the themes of isolation, loneliness, and alienation in fiction and can correctly identify and interpret them. What is your favorite literary work focusing on any of these themes? Tell us in the comments!

❓ Themes of Loneliness and Isolation FAQs

Isolation is a popular theme in poetry. The speakers in such poems often reflect on their separation from others or being away from their loved ones. Metaphorically, isolation may mean hiding unshared emotions. The magnitude of the feeling can vary from light blues to depression.

In his masterpiece Of Mice and Men , John Steinbeck presents loneliness in many tragic ways. The most alienated characters in the book are Candy, Crooks, and Curley’s wife. Most of them were eventually destroyed by the negative consequences of their loneliness.

The Catcher in the Rye uses many symbols as manifestations of Holden’s loneliness. One prominent example is an image of his dead brother Allie. He’s the person Holden wants to bond with but can’t because he is gone. Holden also perceives other people as phony or corny, thus separating himself from his peers.

Beloved is a work about the deeply entrenched trauma of slavery that finds its manifestation in later generations. Characters of Beloved prefer self-isolation and alienation from others to avoid emotional pain.

In Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World , all people must conform to society’s rules to be accepted. Those who don’t fit in that established order and feel their individuality are erased from society.

- What Is Solitude?: Psychology Today

- Loneliness in Literature: Springer Link

- What Literature and Language Tell Us about the History of Loneliness: Scroll.in

- On Isolation and Literature: The Millions

- 10 Books About Loneliness: Publishers Weekly

- Alienation: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Isolation and Revenge: Where Victor Frankenstein Went Wrong: University of Nebraska-Lincoln

- On Isolation: Gale

- Top 10 Books About Loneliness: The Guardian

- Emily Dickinson and the Creative “Solitude of Space:” Psyche

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

Have you ever loved? Even if you haven’t, you’ve seen it in countless movies, heard about it in songs, and read about it in some of the greatest books in world literature. If you want to find out more about love as a literary theme, you came to the right...

Death is undoubtedly one of the most mysterious events in life. Literature is among the mediums that allow people to explore and gain knowledge of death—a topic that in everyday life is often seen as taboo. This article by Custom-Writing.org will: introduce the topic of death in literature and explain...

Wouldn’t it be great if people of all genders could enjoy equal rights? When reading stories from the past, we can realize how far we’ve made since the dawn of feminism. Books that deal with the theme of gender inspire us to keep fighting for equality. In this article, ourcustom-writing...

What makes a society see some categories of people as less than human? Throughout history, we can see how people divided themselves into groups and used violence to discriminate against each other. When groups of individuals are perceived as monstrous or demonic, it leads to dehumanization. Numerous literary masterpieces explore the meaning of monstrosity and show the dire consequences of dehumanization. This article by Custom-Writing.org will: explore...

Revenge provides relief. Characters in many literary stories believe in this idea. Convinced that they were wronged, they are in the constant pursuit of revenge. But is it really the only way for them to find peace? This article by Custom-Writing.org is going to answer this and other questions related...

Is money really the root of all evil? Many writers and poets have tried to answer this question. Unsurprisingly, the theme of money is very prevalent in literature. It’s also connected to other concepts, such as greed, power, love, and corruption. In this article, our custom writing team will: explore...

Have you ever asked yourself why some books are so compelling that you keep thinking about them even after you have finished reading? Well, of course, it can be because of a unique plotline or complex characters. However, most of the time, it is the theme that compels you. A...

The American Dream theme encompasses crucial values, such as freedom, democracy, equal rights, and personal happiness. The concept’s definition varies from person to person. Yet, books by American authors can help us grasp it better. Many agree that American literature is so distinct from English literature because the concept of...

A fallen leaf, a raven, the color black… What connects all these images? That’s right: they can all symbolize death—one of literature’s most terrifying and mysterious concepts. It has been immensely popular throughout the ages, and it still fascinates readers. Numerous symbols are used to describe it, and if you...

The most ancient text preserved to our days raises more questions than there are answers. When was The Iliad written? What was the purpose of the epic poem? What is the subject of The Iliad? The Iliad Study Guide prepared by Custom-Writing.org experts explores the depths of the historical context...

The epic poem ends in a nostalgic and mournful way. The last book is about a father who lost his son and wishes to make an honorable funeral as the last thing he could give him. The book symbolizes the end of any war when sorrow replaces anger. Book 24,...

The main values glorified in The Iliad and The Odyssey are honor, courage, and eloquence. These three qualities were held as the best characteristics a person could have. Besides, they contributed to the heroic code and made up the Homeric character of a warrior. The Odyssey also promotes hospitality, although...

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a narrative essay | Example & tips

How to Write a Narrative Essay | Example & Tips

Published on July 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A narrative essay tells a story. In most cases, this is a story about a personal experience you had. This type of essay , along with the descriptive essay , allows you to get personal and creative, unlike most academic writing .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is a narrative essay for, choosing a topic, interactive example of a narrative essay, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about narrative essays.

When assigned a narrative essay, you might find yourself wondering: Why does my teacher want to hear this story? Topics for narrative essays can range from the important to the trivial. Usually the point is not so much the story itself, but the way you tell it.

A narrative essay is a way of testing your ability to tell a story in a clear and interesting way. You’re expected to think about where your story begins and ends, and how to convey it with eye-catching language and a satisfying pace.

These skills are quite different from those needed for formal academic writing. For instance, in a narrative essay the use of the first person (“I”) is encouraged, as is the use of figurative language, dialogue, and suspense.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Narrative essay assignments vary widely in the amount of direction you’re given about your topic. You may be assigned quite a specific topic or choice of topics to work with.

- Write a story about your first day of school.

- Write a story about your favorite holiday destination.

You may also be given prompts that leave you a much wider choice of topic.

- Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself.

- Write about an achievement you are proud of. What did you accomplish, and how?

In these cases, you might have to think harder to decide what story you want to tell. The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to talk about a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

For example, a trip where everything went according to plan makes for a less interesting story than one where something unexpected happened that you then had to respond to. Choose an experience that might surprise the reader or teach them something.

Narrative essays in college applications

When applying for college , you might be asked to write a narrative essay that expresses something about your personal qualities.

For example, this application prompt from Common App requires you to respond with a narrative essay.

In this context, choose a story that is not only interesting but also expresses the qualities the prompt is looking for—here, resilience and the ability to learn from failure—and frame the story in a way that emphasizes these qualities.

An example of a short narrative essay, responding to the prompt “Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself,” is shown below.

Hover over different parts of the text to see how the structure works.

Since elementary school, I have always favored subjects like science and math over the humanities. My instinct was always to think of these subjects as more solid and serious than classes like English. If there was no right answer, I thought, why bother? But recently I had an experience that taught me my academic interests are more flexible than I had thought: I took my first philosophy class.

Before I entered the classroom, I was skeptical. I waited outside with the other students and wondered what exactly philosophy would involve—I really had no idea. I imagined something pretty abstract: long, stilted conversations pondering the meaning of life. But what I got was something quite different.

A young man in jeans, Mr. Jones—“but you can call me Rob”—was far from the white-haired, buttoned-up old man I had half-expected. And rather than pulling us into pedantic arguments about obscure philosophical points, Rob engaged us on our level. To talk free will, we looked at our own choices. To talk ethics, we looked at dilemmas we had faced ourselves. By the end of class, I’d discovered that questions with no right answer can turn out to be the most interesting ones.

The experience has taught me to look at things a little more “philosophically”—and not just because it was a philosophy class! I learned that if I let go of my preconceptions, I can actually get a lot out of subjects I was previously dismissive of. The class taught me—in more ways than one—to look at things with an open mind.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

If you’re not given much guidance on what your narrative essay should be about, consider the context and scope of the assignment. What kind of story is relevant, interesting, and possible to tell within the word count?

The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to reflect on a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

Don’t worry too much if your topic seems unoriginal. The point of a narrative essay is how you tell the story and the point you make with it, not the subject of the story itself.

Narrative essays are usually assigned as writing exercises at high school or in university composition classes. They may also form part of a university application.

When you are prompted to tell a story about your own life or experiences, a narrative essay is usually the right response.

The key difference is that a narrative essay is designed to tell a complete story, while a descriptive essay is meant to convey an intense description of a particular place, object, or concept.

Narrative and descriptive essays both allow you to write more personally and creatively than other kinds of essays , and similar writing skills can apply to both.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write a Narrative Essay | Example & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/narrative-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write an expository essay, how to write a descriptive essay | example & tips, how to write your personal statement | strategies & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Loneliness Essay Example

Loneliness is a feeling that many people experience at one point or another. The impact of it on your life can vary greatly depending on the situation. This sample will explore the different types of loneliness, how to deal with them, and some tips for overcoming loneliness in general.

Essay Example On Loneliness

- Thesis Statement – Loneliness Essay

- Introduction – Loneliness Essay

- Main Body – Loneliness Essay

- Conclusion – Loneliness Essay

Thesis Statement – Loneliness Essay Loneliness is a consequence of being robbed of one’s freedom. It can be due to imprisonment, loss of liberty, or being discriminated against. Introduction – Loneliness Essay Loneliness is a social phenomenon that has been the subject of much research since time immemorial. Yet there still does not exist any solid explanation as to why some people are more prone to loneliness than others. This paper will seek to analyze this potentially debilitating condition from different perspectives. It will cover the relationship between loneliness and incarceration or loss of liberty; then it will proceed into discussing how emotions play a role in making us feel lonely; finally, it will look at how these feelings can affect our mental stability and overall well-being. Get Non-Plagiarized Custom Essay on Loneliness in USA Order Now Main Body – Loneliness Essay Loneliness is a universal feeling which has the ability to create its own culture within different societies. In detention facilities, there is a unique kind of loneliness that prevails between prisoners who are often divided into various categories and population groups. This has been described by Mandela as a consequence of being robbed of one’s freedom. The fact that it can be due to imprisonment, loss of liberty, or being discriminated against makes it even clearer why this isolation from other people occurs so frequently among detainees. In addition, when one spends time incarcerated in solitary confinement, they may become more experienced at coping with feelings of loneliness and despondency; however, these feelings do not tend to dissipate completely because living in an artificial environment cannot be compared with living out in the open. There is also a difference between feeling lonely and actually being alone; many individuals who do not feel social pressure, meaning that they are more than happy spending time on their own without any external stimulation, may still find themselves surrounded by people every day. Yet even this does not guarantee that one will escape feelings of isolation or rejection. Loneliness becomes an issue when it is chronic and experienced frequently, if only fleetingly. It can affect our psychological balance as well as our physical health because it usually initiates stress responses within the body which cause high blood pressure and prompt addiction to drugs or alcohol consumption. All these reasons may lead to decreased productivity and ultimately affect one’s ability to develop or maintain social connections. Buy Customized Essay on Loneliness At Cheapest Price Order Now Conclusion – Loneliness Essay Loneliness is a condition that we can’t always avoid, but it is something we should be aware of and try to limit. Thus, while the effects of loneliness on the individual may not be able to stimulate any significant changes in society, at least there will always remain one person more who understands what you are going through. Ultimately, it all comes down to empathy and sharing our own stories so that more people learn how to cope with this potentially dangerous emotional response. Hire USA Experts for Loneliness Essay Order Now

Need expert writers to help you with your essay writing? Get in touch!

This essay sample has given you some insights into the psychology of loneliness as well as suggestions for how to combat it in your own life.

Many of us find it hard to start writing an essay on general topics like loneliness. The free essay sample on loneliness is given here by the experts of Students Assignment Help to those who are assigned an essay on loneliness by professors. With the help of this sample, many ideas can easily be gathered by the college graduates to write their coursework essays.

Best essay helpers are giving to College students throughout the world through this sample. All types of essays like Argumentative Essays and persuasive essays can be written by following this example can be finished on time by the masters. If you still find it difficult to write a supreme quality essay on any topic then ask for the essay writing services from Students Assignment Help anytime.

Explore More Relevant Posts

- Nike Advertisement Analysis Essay Sample

- Mechanical Engineer Essay Example

- Reflective Essay on Teamwork

- Career Goals Essay Example

- Importance of Family Essay Example

- Causes of Teenage Depression Essay Sample

- Red Box Competitors Essay Sample

- Deontology Essay Example

- Biomedical Model of Health Essay Sample-Strengths and Weaknesses

- Effects Of Discrimination Essay Sample

- Meaning of Freedom Essay Example

- Women’s Rights Essay Sample

- Employment & Labor Law USA Essay Example

- Sonny’s Blues Essay Sample

- COVID 19 (Corona Virus) Essay Sample

- Why Do You Want To Be A Nurse Essay Example

- Family Planning Essay Sample

- Internet Boon or Bane Essay Example

- Does Access to Condoms Prevent Teen Pregnancy Essay Sample

- Child Abuse Essay Example

- Disadvantage of Corporate Social Responsibilities (CSR) Essay Sample

- Essay Sample On Zika Virus

- Wonder Woman Essay Sample

- Teenage Suicide Essay Sample

- Primary Socialization Essay Sample In USA