- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Lunar New Year 2024

By: History.com Editors

Updated: February 9, 2024 | Original: February 4, 2010

Lunar New Year is one of the most important celebrations of the year among East and Southeast Asian cultures, including Chinese, Vietnamese and Korean communities, among others. The New Year celebration is celebrated for multiple days—not just one day as in the Gregorian calendar’s New Year.

This Lunar New Year, which begins on February 10, is the Year of the Dragon.

China’s Lunar New Year is known as the Spring Festival or Chūnjié in Mandarin, while Koreans call it Seollal and Vietnamese refer to it as Tết .

Tied to the lunar calendar, the holiday began as a time for feasting and to honor household and heavenly deities, as well as ancestors. The New Year typically begins with the first new moon that occurs between the end of January and spans the first 15 days of the first month of the lunar calendar—until the full moon arrives.

Zodiac Animals

Each year in the Lunar calendar is represented by one of 12 zodiac animals included in the cycle of 12 stations or “signs” along the apparent path of the sun through the cosmos.

The 12 zodiac animals are the rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog and pig. In addition to the animals, five elements of earth, water, fire, wood and metal are also mapped onto the traditional lunar calendar. Each year is associated with an animal that corresponds to an element.

The year 2024 is slated to be the year of the dragon—an auspicious symbol of power, wisdom and good fortune. The year of the dragon last came up in 2012.

Lunar New Year Foods and Traditions

Each culture celebrates the Lunar New Year differently with various foods and traditions that symbolize prosperity, abundance and togetherness. In preparation for the Lunar New Year, houses are thoroughly cleaned to rid them of inauspicious spirits, which might have collected during the old year. Cleaning is also meant to open space for good will and good luck.

Some households hold rituals to offer food and paper icons to ancestors. Others post red paper and banners inscribed with calligraphy messages of good health and fortune in front of, and inside, homes. Elders give out envelopes containing money to children. Foods made from glutinous rice are commonly eaten, as these foods represent togetherness. Other foods symbolize prosperity, abundance and good luck.

Chinese New Year is thought to date back to the Shang Dynasty in the 14th century B.C. Under Emperor Wu of Han (140–87 B.C.), the tradition of carrying out rituals on the first day of the Chinese calendar year began.

“This holiday has ancient roots in China as an agricultural society. It was the occasion to celebrate the harvest and worship the gods and ask for good harvests in times to come," explains Yong Chen, a scholar in Asian American Studies.

During the Cultural Revolution in 1967, official Chinese New Year celebrations were banned in China. But Chinese leaders became more willing to accept the tradition. In 1996, China instituted a weeklong vacation during the holiday—now officially called Spring Festival—giving people the opportunity to travel home and to celebrate the new year.

Did you know? San Francisco, California, claims its Chinese New Year parade is the biggest celebration of its kind outside of Asia. The city has hosted a Chinese New Year celebration since the Gold Rush era of the 1860s, a period of large-scale Chinese immigration to the region.

Today, the holiday prompts major travel as hundreds of millions hit the roads or take public transportation to return home to be with family.

Among Chinese cultures, fish is typically included as a last course of a New Year’s Eve meal for good luck. In the Chinese language, the pronunciation of “fish” is the same as that for the word “surplus” or “abundance.” Chinese New Year’s meals also feature foods like glutinous rice ball soup, moon-shaped rice cakes (New Year’s cake) and dumplings ( Jiǎozi in Mandarin). Sometimes, a clean coin is tucked inside a dumpling for good luck.

The holiday concludes with the Lantern Festival, which is celebrated on the last day of New Year's festivities. Parades, dances, games and fireworks mark the finale of the holiday.

In Vietnamese celebrations of the holiday, homes are decorated with kumquat trees and flowers such as peach blossoms, chrysanthemums, orchids and red gladiolas. As in China, travel is heavy during the holiday as family members gather to mark the new year.

Families feast on five-fruit platters to honor their ancestors. Tết celebrations can also include bánh chưng , a rice cake made with mung beans, pork, and other ingredients wrapped in bamboo leaves. Snacks called mứt tết are commonly offered to guests. These sweet bites are made from dried fruits or roasted seeds mixed with sugar.

In Korea, official Lunar New Year celebrations were halted from 1910-1945. This was when the Empire of Japan annexed Korea and ruled it as a colony until the end of World War II . Celebrations of Seollal were officially revived in 1989, although many families had already begun observing the lunar holiday. North Korea began celebrating the Lunar New Year according to the lunar calendar in 2003. Before then, New Year's was officially only observed on January 1. North Koreans are also encouraged to visit statues of founder Kim Il Sung, and his son Kim Jong Il, during the holidays and provide an offering of flowers.

Among both North and South Koreans, sliced rice cake soup ( tteokguk ) is prepared to mark the Lunar New Year holiday. The clear broth and white rice cakes of tteokguk are believed to symbolize starting the year with a clean mind and body. Rather than giving money in red envelopes, as in China and Vietnam, elders give New Year's money in white and patterned envelopes.

Traditionally, families gather from all over Korea at the house of their oldest male relative to pay their respects to both ancestors and elders. Travel is less common in North Korea and families tend to mark the holiday at home.

Lunar New Year Greetings

Cultures celebrating Lunar New Year have different ways of greeting each other during the holiday. In Mandarin, a common way to wish family and close friends a happy New Year is “ Xīnnián hǎo ,” meaning “New Year Goodness” or “Good New Year.” Another greeting is “ Xīnnián kuàilè, ” meaning "Happy New Year."

Traditional greetings during Tết in Vietnam are “Chúc Mừng Năm Mới” (Happy New Year) and “Cung Chúc Tân Xuân” (gracious wishes of the new spring). For Seollal, South Koreans commonly say "Saehae bok mani badeuseyo” (May you receive lots of luck in the new year), while North Koreans say "Saehaereul chuckhahabnida” (Congratulations on the new year).

— huiying b. chan , Research and Policy Analyst on the Education Justice Research and Organizing Collaborative team at the New York University Metro Center, edited this report.

"Lunar New Year origins, customs explained," by Laura Rico, University of California, Irvine , February 19, 2015.

"Everything you need to know about Vietnamese Tết," Vietnam Insider , December 3, 2020.

"Seollal, Korean Lunar New Year," by Brendan Pickering, Asia Society .

"The Origin of Chinese New Year," by Haiwang Yuan, Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR , February 1, 2016.

"The Lunar New Year: Rituals and Legends," Asia for Educators .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- HISTORY & CULTURE

Why Lunar New Year prompts the world’s largest annual migration

Observed by billions of people, the festival also known as Chinese New Year or Spring Festival is marked by themes of reunion and hope.

Celebrated around the world, it usually prompts the planet’s largest annual migration of people. And though it is known to some in the West as Chinese New Year , it isn’t just celebrated in China. Lunar New Year falls this year on February 10, 2024, kicking off the Year of the Dragon. It is traditionally a time for family reunions, plenty of food, and some very loud celebrations.

What is the Lunar New Year?

Modern China actually uses a Gregorian calendar like most of the rest of the world. Its holidays, however, are governed by its traditional lunisolar calendar , which may have been in use from as early as the 21st century B.C. When the newly founded Republic of China officially adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1912, its leaders rebranded the observation of the Lunar New Year as Spring Festival, as it is known in China today.

( Learn why some people celebrate Christmas in January. )

As its name suggests, the date of the lunar new year depends on the phase of the moon and varies from year to year. Each year in the lunar calendar is named one of the 12 animals in the Chinese zodiac , which are derived from ancient Chinese folklore. Repeating in a rotating basis, these animals are the rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog, and pig.

Today, Spring Festival is celebrated in China and Hong Kong; Lunar New Year is also celebrated in South Korea, Tibet, Vietnam, Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, and places with large Chinese populations. Though the festival varies by country, it is dominated by themes of reunion and hope.

How Lunar New Year is celebrated

For Chinese people, Spring Festival lasts for 40 days and has multiple sub-festivals and rituals. The New Year itself is a seven-day-long state holiday, and on the eve of the new year, Chinese families traditionally celebrate with a massive reunion dinner. Considered the year’s most important meal, it is traditionally held in the house of the most senior family member.

( Learn about Lunar New Year with your kids. )

The holiday may be getting more modern, but millennia-old traditions are still held dear in China and other countries. In China, people customarily light firecrackers, which are thought to chase away the fearful monster Nian. (However, the tradition has been on the decline in recent years due to air pollution restrictions that have hit the fireworks industry hard.) The color red is used in clothing and decorations to ensure prosperity, and people exchange hongbao , red envelopes filled with lucky cash.

Meanwhile in Korea, people make rice cake soup and honor their ancestors during Seollal . And during Tet, the Vietnamese Lunar New Year, flowers play an important role in the celebrations.

Lunar New Year has even spawned its own form of travel: During chunyun , or spring migration, hundreds of million people travel to their hometowns in China for family reunions and New Year’s celebrations. In past years, billions of travelers have taken to the road during the 40-day period. Known as the world’s largest human migration, chunyun regularly clogs already busy roads, trains and airports—proof of the holiday’s enduring significance for those who associate it with luck and love.

This story was originally published on January 2, 2020. It has been updated.

FREE BONUS ISSUE

Related topics.

- HUMAN MIGRATION

- IMPERIAL CHINA

You May Also Like

This ancient festival is a celebration of springtime—and a brand new year

Why Swedish children celebrate Easter by dressing up as witches

How the nation chooses its best and brightest Christmas trees

Meet 5 of history's most elite fighting forces

How do we know when Ramadan starts and ends? It’s up to the moon.

- History & Culture

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

The Origin and History of Chinese New Year: When Start and Why

Chinese New Year, also known as the Lunar New Year or the Spring Festival, is the most important among the traditional Chinese festivals. The origin of the Chinese New Year Festival can be traced back to about 3,500 years ago . Chinese New Year has evolved over a long period of time and its customs have undergone a long development process.

A Legend of the Origin of Chinese New Year

Like all traditional festivals in China, Chinese New Year is steeped with stories and myths. One of the most popular is about the mythical beast Nian (/nyen/), who ate livestock, crops, and even people on the eve of a new year. (It's interesting that Nian, the 'yearly beast', sounds the same as 'year' in Chinese.) To prevent Nian from attacking people and causing destruction, people put food at their doors for Nian.

It's said that a wise old man figured out that Nian was scared of loud noises (firecrackers) and the color red. Then, people put red lanterns and red scrolls on their windows and doors to stop Nian from coming inside, and crackled bamboo (later replaced by firecrackers) to scare Nian away. The monster Nian never showed up again. Click to learn more legends about the Chinese New Year .

Chinese New Year's Origin: In the Shang Dynasty

Chinese New Year has enjoyed a history of about 3,500 years. Its exact beginning is not recorded. Some people believe that Chinese New Year originated in the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BC), when people held sacrificial ceremonies in honor of gods and ancestors at the beginning or the end of each year.

Chinese Calendar "Year" Established: In the Zhou Dynasty

The term Nian ('year') first appeared in the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BC). It had become a custom to offer sacrifices to ancestors or gods, and to worship nature in order to bless harvests at the turn of the year.

Chinese New Year Date Was Fixed: In the Han Dynasty

The date of the festival, the first day of the first month in the Chinese lunar calendar, was fixed in the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD). Certain celebration activities became popular, such as burning bamboo to make a loud cracking sound. See when Chinese New Year is and how the date is determined .

In the Wei and Jin Dynasties

In the Wei and Jin dynasties (220–420), apart from worshiping gods and ancestors, people began to entertain themselves. The customs of a family getting together to clean their house, having dinner, and staying up late on New Year's Eve originated among common people.

More Chinese New Year Activities: From the Tang to Qing Dynasties

The prosperity of economies and cultures during the Tang , Song , and Qing dynasties accelerated the development of the Spring Festival. The customs during the festival became similar to those of modern times.

Setting off firecrackers, visiting relatives and friends, and eating dumplings became important parts of the celebration.

More entertaining activities arose , such as watching dragon and lion dances during the Temple Fair and enjoying lantern shows.

The function of the Spring Festival changed from a religious one to entertaining and social ones, more like that of today.

In Modern Times

In 1912, the government decided to abolish Chinese New Year and the lunar calendar, but adopted the Gregorian calendar instead and made January 1 the official start of the new year.

After 1949, Chinese New Year was renamed to the Spring Festival . It was listed as a nationwide public holiday.

Nowadays, many traditional activities are disappearing but new trends have been generated. CCTV (China Central Television) Spring Festival Gala, shopping online, WeChat red envelopes, fireworks shows, and overseas travel make Chinese New Year more interesting and colorful.

You Might Like

- Top 3 Interesting Chinese New Year Legends/Stories

- 10 Quick Facts about Lunar New Year

- How to Celebrate Chinese New Year: Top 18 Traditions

- Chinese New Year Taboos and Superstitions: 18 Things You Should Not Do

- 8-Day Beijing–Xi'an–Shanghai Private Tour

- 9-Day Beyond the Golden Triangle

- 10-Day Lanzhou–Xiahe–Zhangye–Dunhuang–Turpan–Urumqi Tour

- 11-Day Classic Wonders

- 11-Day Family Happiness

- 12-Day China Silk Road Tour from Xi'an to Kashgar

- 12-day Panda Keeper and Classic Wonders

- 12-Day Shanghai, Huangshan, Hangzhou, Guilin and Hong Kong Tour

- 13-Day Beijing–Xi'an–Dunhuang–Urumqi–Shanghai Tour

- 14-Day China Natural Wonders Discovery

- 2-Week Riches of China

- 3-Week Must-See Places China Tour Including Holy Tibet

- How to Plan Your First Trip to China 2024/2025 — 7 Easy Steps

- How to Plan Your First-Time Family Trip to China

- Best (& Worst) Times to Visit China, Travel Tips (2024/2025)

- One Week in China - 4 Time-Smart Itineraries

- How to Plan a 10-Day Itinerary in China (Best 5 Options)

- Top 4 China Itinerary Options in 12 Days (for First Timers) 2024/2025

- 2-Week China Itineraries: Where to Go & Routes (2024)

- 17-Day China Itineraries: 4 Unique Options

- How to Spend 19 Days in China in 2024/2025 (Top 5 Options and Costs)

- How to Plan a 3-Week Itinerary in China: Best 3 Options (2024)

- China Itineraries from Hong Kong for 1 Week to 3 Weeks

- China Weather in January 2024: Enjoy Less-Crowded Traveling

- China Weather in March 2024: Destinations, Crowds, and Costs

- China Weather in April 2024: Where to Go (Smart Pre-Season Pick)

- China Weather in May 2024: Where to Go, Crowds, and Costs

- China Weather in June 2024: How to Benefit from the Rainy Season

- China Weather in July 2024: How to Avoid Heat and Crowds

- China Weather in August 2024: Weather Tips & Where to Go

- China Weather in September 2024: Weather Tips & Where to Go

- China Weather in October 2024: Where to Go, Crowds, and Costs

- China Weather in November 2024: Places to Go & Crowds

- China Weather in December 2024: Places to Go and Crowds

Get Inspired with Some Popular Itineraries

More travel ideas and inspiration, sign up to our newsletter.

Be the first to receive exciting updates, exclusive promotions, and valuable travel tips from our team of experts.

Why China Highlights

Where can we take you today.

- Southeast Asia

- Japan, South Korea

- India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Sri lanka

- Central Asia

- Middle East

- African Safari

- Travel Agents

- Loyalty & Referral Program

- Privacy Policy

Address: Building 6, Chuangyi Business Park, 70 Qilidian Road, Guilin, Guangxi, 541004, China

How Lunar New Year Is Being Celebrated By Asian Communities Around the World

B illions of people have begun their 15-day celebration of the Lunar New Year, marked by the many red paper cuttings, Chinese lanterns, and banners adorning homes and businesses.

The Lunar New Year is one of the most popular holidays in China, though it is celebrated all across the Asian continent and in pockets of ethnic communities around the globe. The holiday marks the arrival of spring and the start of a new year under the lunisolar calendar in a celebration that dates back to the Chinese agrarian tradition.

Every year, the holiday, also known as the Spring Festival, begins on the second new moon after the winter solstice. In 2024, the celebration falls on Saturday, Feb. 10. and marks the year of the dragon . (There are 12 different animals in the Chinese zodiac—rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog, dragon, and pig—each of which will mark the personality and fortune of those born during that year).

Dragons have a special significance in China. They are the only animal of the zodiac that is mythical, and the creature largely symbolizes luck, strength, ambition, and charm.

Here’s how communities across the world are celebrating.

How China is celebrating Lunar New Year

In the second most populous country of the world, Chinese locals, along with tourists, gathered to observe the holiday by setting off firecrackers and fireworks.

Ancient legend dictates that the tradition wards off evil spirits, specifically scaring the mythical monster of Nian who would allegedly leave its home at the bottom of the sea to feast on people and livestock in villages at the start of the new year. That is, until an elderly man realized that he could scare Nian away by burning bamboo (which is similar to a firecracker), lighting candles or having any bright lights, and pasting red decorations on doors.

The tradition has since stuck, prompting people to light red candles across temples and host colorful fireworks shows on the eve of the Chinese New Year. Some of the celebrations have been stifled by firework bans across hundreds of urban communities in China, with legislators citing pollution and safety hazards as the reason for the ban.

Read more: 5 Things to Know About Lunar New Year

How the U.S. is marking Lunar New Year

A continent away, Asian communities in the U.S. are also commemorating the joyous occasion.

Celebrations are especially prominent in California, the state with the largest number of Chinese immigrants, though New York also has a large population.

The Golden State marks their holiday with festivals featuring lion dances, and floral arts displays in San Marino, and the highly-anticipated G olden Dragon Lunar New Year Parade in Los Angeles. More than 100,000 spectators are expected to attend the aforementioned parade, which has been happening for 124 years .

Other communities, like that of Monterey Park, are healing from the heartache of tragedy as they commemorate the one year anniversary of the shooting that left 11 dead and injured another nine at a local ballroom dance studio during Lunar New Year celebrations.

How South Korea welcomes Lunar New Year

In South Korea, where Lunar New Year is called "Seollal ,” people often travel to their hometowns to honor their ancestors’ spirits. Families traditionally prepare an offering of a table filled with food, and perform a deep bow known as “ sebae ” to acknowledge their older relatives. Some Koreans also choose to wear the traditional Korean clothes, or “hanbok”—typically, a colorful, high-waisted long skirt, or loose-fitting trousers, with a jacket.

To celebrate, people typically prepare traditional food such as mandu dumplings filled with meat, vegetables or kimchi, and tteokguk , a rice cake soup, which some say causes you to grow another year older, or will provide luck. They may also play folk games, including the board game “ Yut Nori ,” or fly a kite .

The way Lunar New Year is observed in South Africa

In South Africa, people gathered to mark the new year at the Buddhist Fo Guang Shan Nan Hua Temple in Bronkhorstspruit.

Celebrants put on traditional outfits, offered prayers, and enjoyed a traditional dance in which people performed with a large dragon puppet.

Indonesia’s Lunar New Year festivities

In Indonesia, families traditionally go to their local temple to mark the beginning of the Lunar New Year. Some temples have been in place for centuries, like the Yin De Yuan Temple in the capital of Jakarta, which was built in 1650. Religious centers are usually decorated with red lanterns and large red candles.

There are other fun cultural events like lion dances, music, and creative performances in the city of Semarang. Other festivals are a blend of Chinese and Javanese culture, such as the Grebeg Sudiro festival in Solo, located in the Central Java Province. Grebeg celebrations have large cone-shaped displays of fruits, vegetables, or cakes that are “fought over” by the spectators, according to Indonesia’s tourist site . The custom stems from a Javanese teaching that emphasizes that people have to earn what they eat.

How the U.K. is celebrating the Lunar New Year

The London Chinatown Chinese Association is hosting a parade in honor of the holiday on Sunday, Feb. 11. The festivities will move through Chinatown, bringing traditional dragon dancers to Trafalgar Square to start things off. Onlookers will also be able to enjoy delicious food, opera, and martial arts performances.

“As the Year of the Dragon begins, I want to thank London’s East and South East Asian communities for everything they contribute to our city,” wrote London Mayor Sadiq Khan in a post on X (formerly Twitter) . “Wishing you all—and everyone celebrating across our capital and around the world—a very Happy Lunar New Year.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Passengers Are Flying up to 30 Hours to See Four Minutes of the Eclipse

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Essay: The Complicated Dread of Early Spring

- Why Walking Isn’t Enough When It Comes to Exercise

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

- Immersion Program

- Learn Chinese Online

- Study Abroad in China

- Custom Travel Programs

- Teach in China

- What is CLI?

- Testimonials

- The CLI Center

- Photo Gallery

A Brief Guide to the Chinese New Year (春节 Chūnjié)

Learn Chinese in China or on Zoom and gain fluency in Chinese!

Join CLI and learn Chinese with your personal team of Mandarin teachers online or in person at the CLI Center in Guilin , China.

Perhaps the most important of all Chinese holidays , the Chinese New Year is celebrated worldwide each January or February in places like Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, the Philippines, and Mainland China.

Also called the Spring Festival (春节 Chūnjié), the Chinese New Year celebrates the beginning of the Chinese year based on the traditional Chinese lunisolar calendar and officially ends 14 days later with the Lantern Festival .

Table of Contents

How is Chinese New Year celebrated?

1. steamed fish | 蒸鱼 | zhēng yú, 2. new year cake | 年糕 | niángāo, 3. spring rolls | 春卷 | chūnjuǎn, 4. fruits | 水果 | shuǐguǒ, 5. dumplings | 饺子 | jiǎozi, 6. “longevity noodles” | 长寿面 | chángshòumiàn, 7. tangyuan | 汤圆 | tāngyuán, 1. 新年快乐 (xīnnián kuàilè) - happy new year, 2. 恭喜发财 (gōngxǐfācái) - may you have a prosperous year, 兔年大吉 (tùnián dàjí) - happy year of the rabbit (2023), 4. 岁岁平安 (suìsuì píng'ān) - may you have peace year after year, 5. 万事如意 (wànshìrúyì) - may all your hopes be fulfilled, 1. no cleaning, 2. no wearing black or white, 3. no cutting hair, 4. no breaking things, why is it called the “lunar” new year, chinese zodiac animal signs, the chinese new year through a local's eyes, chinese vocabulary for the spring festival, join a spring festival celebration and practice your chinese.

Learn Chinese with CLI

Spring Festival is a time for families to come together, exchange money-filled red envelopes (红包, hóngbāo) , and enjoy delicious Chinese food.

The Chinese New Year is a 15-day holiday and includes a variety of festivities depending on the region and its local traditions and customs. However, certain common customs are shared regardless of region.

For example, it is common practice to decorate one’s home with Chinese lanterns . In many homes, you will find auspicious Chinese characters and couplets on red paper stuck on doors. Red is an auspicious color as it scares away the Nian monster . Wearing new clothes is also a common tradition to ward off bad luck—a new year is a time for newness after all!

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Chinese Language Institute (@studycli)

The Chinese New Year is an important time to 拜年 (bàinián, to pay a new year call), so it is common practice to visit relatives and exchange auspicious greetings and Chinese gifts , including the ever-popular lucky red envelopes filled with Chinese currency . Devoted Buddhist and Daoist practitioners also often visit local temples to welcome the new year.

The holiday has even had an influence on the traditional festivals of other cultures with whom the Chinese have historically interacted, including the Koreans, Vietnamese, Mongolians, and Japanese.

What foods are eaten during Chinese New Year?

Family is of central importance in traditional Chinese culture, and Spring Festival is generally a very family-oriented holiday.

The New Year’s Eve dinner (年夜饭 niányèfàn) kick starts the tradition of family reunions. In fact, the Chinese Spring Festival also marks the world’s largest human migration, as overseas Chinese and Chinese migrant laborers return home to celebrate the advent of the new year alongside their families.

Though traditions can vary between northern and southern China, here are a few examples of common “auspicious foods” presented at reunion dinners:

As you may already know, the Chinese language includes many homophones (同音词 tóngyīncí), which results in many characters and words having the same pronunciation as one another.

In this instance, “fish” (鱼 yú) has the same pronunciation as “surplus” (余 yú). There is also a typical New Year greeting, 年年有余 (niánnián yǒuyú), which translates to “may you have a surplus (of blessings) every year”. Therefore, eating fish symbolizes an increase in prosperity.

Sticky rice cakes symbolize a prosperous year to come, as “cake” (糕 gāo) has the same pronunciation as “high/lofty” (高 gāo). This coincides with the greeting 年年高升 (niánniángāoshēng; “advance year after year”). Rice cakes are a must during Chinese New Year festivities!

How can you start spring without spring rolls? This delicacy was originally a seasonal food that was consumed only during the spring. Eating spring rolls is a way to welcome the arrival of spring, and their golden color also symbolizes wealth and prosperity.

Fruits are commonly enjoyed as desserts and snacks during Spring Festival celebrations. They symbolize life and new beginnings and are also a common new year gift.

Due to their resemblance to imperial coins (元宝 yuánbǎo), dumplings are representative of wealth and fortune.

“Longevity noodles” are a kind of flat Cantonese egg noodles which are usually consumed during special occasions (such as the Chinese New Year and birthdays).

As their name indicates, their long strings represent longevity and living to a ripe old age. The trick is to eat them in a single mouthful and not cut the noodles short!

The fifteenth and final day of the new year holiday is celebrated by the Lantern Festival (元宵节 Yuánxiāojié). During this time, it is common to eat a Chinese dessert called tāngyuán (汤圆), which consists of sweet glutinous rice balls filled with a variety of fillings such as sesame, peanut, and red bean paste. Their round shapes represent togetherness and reunion.

How to Say Happy New Year in Chinese

Would you like to wish a friend, colleague, or loved one Happy New Year in Chinese? Read on to learn this festive phrase and more!

Cultural note: In China, people often hold a fist salute or 抱拳礼 (bàoquánlǐ) when saying the below greetings. Remember that this method of greeting is mainly used during formal occasions, so we suggest to avoid using it during informal encounters!

Saying “Xīnnián Kuàilè” is the simplest and most straightforward way to wish your Chinese friends, family and colleagues a happy new year. Want to know how to pronounce it? Just watch the following video and repeat!

In addition to 新年快乐 (Xīnnián Kuàilè), this is probably the most popular saying you'll hear around the Chinese New Year. It has been the center of many 贺年歌曲 (hènián gēqǔ, Chinese New Year songs) and literally means “congratulations, make a fortune!”

Learn to sing along to the famous Chinese New Year song “恭喜” (gōngxǐ) in the following video.

大吉 (dàjí) is a noun meaning very auspicious or lucky. You can put any given year's zodiac animal year before 大吉 and use it as a general new year greeting. You can also simply say 大吉大利 (dàjídàlì), which means “good luck and great prosperity.”

To learn how to say other year-specific Spring Festival greetings, see the Spring Festival Chinese Vocabulary List toward the bottom of this article.

A fun things aspect of Chinese is wordplay based on 同音词 (tóngyīncí, homophones). A great example of this is 岁岁平安. Breaking things during the Chinese new year is a taboo in China as it is believed to bring bad luck resulting in money loss and a family split in the future.

If something does break, you can say “碎碎平安” (suìsuìpíngān) which sounds exactly the same as “岁岁平安” (suìsuìpíngān) . “碎” means to break, whereas “岁” means age or year and is the character used in 岁岁平安. This is a very clever way to negate all that bad luck!

万 literally means “ten thousand” or “a great number.” When you say 万事如意 to your Chinese friends, you are literally wishing that all matters (万事, ten thousand matters/affairs) be according to his/her wishes (如意)。

What are some taboos during Spring Festival?

All auspicious things aside, there are certain taboos that must be avoided during Chinese New Year:

Any type of “spring cleaning” must take place before the new year and never during the actual holiday. This allows the cleaned space to be filled with the new blessings and fortunes of the new year. Cleaning during the holiday consequently means that you are getting rid of these new fortunes!

In Chinese color symbolism, black signifies evil and white is the color of death and used for funerals. Instead, auspicious colors such as red and gold are often worn during the new year.

发 fā (hair) is also the character and sound for 发财 fā cái (to get rich), so cutting hair signifies a loss of fortune.

碎 suì means to break, whereas 岁 suì means age or year. If something does break, you can say “碎碎平安” (suì suì píng ān) which sounds exactly the same as “岁岁平安” (“may you have peace year after year”).

The term “lunar” is an English adaptation, mainly because the holiday starts with the new moon, ends with the full moon 14 days later, and is thus based on the Chinese lunisolar calendar . The name of the holiday in Chinese, 春节 Chūnjié, literally translates to “Spring Festival”.

The Chinese New Year is also a time when the annual zodiac sign changes, meaning that each year is assigned to a specific zodiac animal. Zodiac signs play an integral role in Chinese culture. It is said that your luck regarding financial situations, health and relationships for each year can be calculated based on your zodiac sign.

To ask your Chinese friends and colleagues what their zodiac animal is, just say "你属什么? (nǐ shǔ shénme?)". 属 shǔ can mean “to belong to” or “to be born in the year of". In China, it is common to be asked how old you are or what your 生肖 (shēngxiào, Chinese zodiac sign) is.

In response, you can say: 我属 (wǒ shǔ) + insert animal. For example: “我属牛” (Wǒ shǔ niú, I was born in the Year of the Ox ). Consult CLI's article on the 12 Chinese Zodiac Animals for an in-depth look at this cultural phenomena and to find out what your own zodiac sign is!

In our Spring Festival video, we invite you to peer into the life of a Guilin resident who walked the same arduous path traveled by so many in China from poverty to prosperity. Join Dayong, a CLI team member since 2009, as he converses with Uncle Ye (叶叔叔, Yè Shūshu) about how his quality of life has changed for the better over the decades.

While watching the video, follow along in this downloadable Chinese-English transcript for the Chinese characters, Chinese pinyin , and English translation.

We hope this article helped you learn more about the Chinese New Year! It is truly a fun and festive holiday that is celebrated all across the world. Spring Festival is a time for family reunions, showing appreciation for one’s friends, and delicious feasts.

If you are in China during Spring Festival, we hope you'll get to experience this important holiday for yourself by participating in some Chinese New Year activities with friends or colleagues. Keep in mind that many people will be traveling back and forth during this period as part of the famous Spring Festival travel rush (春运 chūnyùn). If you do plan to go anywhere during this period, especially by train , make sure to buy your tickets far in advance.

If you aren't in China, we encourage you to seek out your local Chinese community, attend holiday events, and even volunteer to help prepare for the Chinese New Year festivities. This is a great way to learn more about Chinese culture and to immerse yourself in the Chinese language .

And now that you know some Chinese New Year greetings, it is time to put them to use! On behalf of the CLI team, we wish you a wonderful Chinese New Year and welcome you to learn Chinese in China . 祝大新年快乐,身体健康,万事如意 !

Free 30-minute Trial Lesson

Continue exploring.

- Chinese Holidays

Copyright 2024 | Terms & Conditions | FAQ | Learn Chinese in China

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

What the Lunar New Year Means to Me

By Lan Samantha Chang

We may earn a commission if you buy something from any affiliate links on our site.

My preparations for each Lunar New Year begin in the bathroom. On Lunar New Year’s Eve, I turn on the hot water and let the air fill with steam. With my bare toes curled against the chilly floor, I scissor off a lock of hair, clip my nails, and discard these symbolic crumbs of bad luck into the trash. Then I get in the shower, where I suds and scour and scrub down every inch of skin.

“You have to wash off all of the bad luck from the year before.” This was my mother’s imperative, as if bad fortune could accumulate into a grungy layer over the course of the year. As if I had one chance—a crucial opening on a February night—in which it would be possible to get rid of it.

The cleanse on Lunar New Year’s Eve is one of many customs—really, superstitions—taught to me by my late mother and father. It’s part of a larger idea that everything should be immaculate, including the body and the home, which should also be tidied and, most importantly, swept out. This is done to lay a perfect groundwork for the coming year: spotless and unblemished by past trouble. A vision of an annual opportunity, of incremental growth, was a fundamental part of my parents’ Chinese lives long before the 1950s, when they put these lives behind them to face a new existence in the US.

My parents’ catalog of rituals must contain only a fraction of the traditions followed by Lunar New Year’s billion celebrants worldwide. But my mother and father were firm about what they believed. We must eat certain lucky foods: labor-intensive sweet-rice-and-red-bean cakes; steamed dumplings; a whole fish covered with ginger and scallions; and lots of fruit, including, especially, oranges and lychees. The lychees, my mother warned, should not be paired with crabmeat—a bad combination, a dangerously “cold” shock to the system, possibly fatal. And we should never make soup because “if you serve soup on New Year’s, it will rain on every special occasion for the rest of the year.” When we had a rare meal out, we went to my parents’ favorite local restaurant, Bao Ju, in Neenah, Wisconsin. It was named after the Chinese word for firecrackers, which were set off on the New Year to chase away evil spirits. The phone number of the restaurant contained several eights; eight was a lucky number, as was nine, whereas four, the unluckiest number of all, should be avoided.

My parents wished so fervently for luck in the New Year. For good health, of course, but especially for money. And so bits of cash were exchanged, to encourage an increase of fortune. We children thanked our older relatives for annual red envelopes that were sent to us by mail. On the second day of the New Year, my father or mother would usually bundle up in something red and hurtle him or herself into the glacial Wisconsin winter, walking, “in all directions,” in an attempt to encounter the Money God. Such a meeting, I was told, would result in a rich year. My questions about this ritual were met with a dead end. “What does the Money God look like?” I asked my mother. “No one knows.” “Will the Money God appear as a person? Is it an inanimate object?” “I don’t know.” “What are the other gods?” Silence.

Thus my parents shut down my questions whenever I tried to cross-examine them about these protocols. I was lectured on the value of a “rational” Western education. They insisted superstitions were for the ignorant and they would sometimes scold me for even mentioning such topics. I learned to keep my mouth shut and my ears open. My sisters and I overheard my father and mother, behind closed doors, discussing in hushed voices our strengths and weaknesses as students and daughters, referring to our birth animals from the Chinese zodiac. When one of us entered the room, they would immediately stop talking. Maybe they didn’t want us to know of their belief in the irrational; maybe they wanted to protect us from succumbing to fatalism. After I left home for college, my mother would phone me on the holiday to deliver Lunar New Year prognostications for my sisters and myself. If a bad year was coming, I should wear a red bracelet. She claimed the predictions were oddities from the Chinese newspaper. She said she didn’t believe any of it. But if I waited long enough, she would drop bits of information denoting genuine concern for me or one of my sisters—that women born in the Year of Dragon (myself) marry late, for example, and that Horse women (my oldest sister) never marry at all.

Decades later, now that both of my parents are gone, I wonder why their New Year practices were so steeped in superstition. My mother and father had US college educations and my father held a master’s degree in engineering from Columbia University. They each claimed a Western rationality. Did they actually believe that taking certain, ritual actions portended good luck? It’s now too late to ask. My mother died in 2014, and my father died in 2020, outlasting her at age 97.

Of course, my parents longed for money—they had four children and my father’s salary as a researcher didn’t cover extras. As they were unable to afford childcare, my mother stayed home with us. We never ate at McDonald’s. My sisters learned to sew their own prom dresses. When my youngest sister started school, my mother began to work, giving piano lessons in our living room. But as we grew, new financial challenges evolved: transportation, books, tuition.

To my mother, I think, the desire for money must have been a way to manage her anxiety over even larger uncertainties: What would become of her poor health, my impractical career choices, the lack of clarity in my sisters’ and my romantic lives? Maybe in the New Year, I would finally start to make some money as a writer. Maybe I would meet the perfect man: a Monkey or a Rat. Born only 40 years after the end of foot-binding, my mother had studied psychology before she married my father, raised us, and eventually made a career as a respected teacher. She had one of the most open minds I’ve known. But in addition to her belief in the value of education and environment, she held a deep need to assume some power outside of herself. She possessed a kind of fatalism that had emerged, I am guessing, during the constant wishing and hoping through her childhood in wartime China and, later, in the US as an impoverished student with no family support.

My father, a chemical engineer, had worked hard for an education in Western science. He generally scoffed at old customs, keeping his silence on this subject. And yet, he didn’t contradict anything my mother said about it. With a child’s instinct, I sensed he believed in the superstitions my mother explicitly asserted. Even then, I knew my father was more afraid of the power of bad luck than he was hopeful for good luck. He had grown up in mainland China under the Japanese occupation, and had been homeless in a war, before he turned 19. He had gone hungry. The prolonged, high-wire act of his life was arriving in this country at age 30 with nothing, raising a family on an inadequate salary, and somehow managing to put all four of his daughters through Ivy League colleges. As a parent now myself, I can see he took responsibility for our lives, and so his fear of bad fortune was embedded in some deeper, more elemental part of his nature. His fear was the bedrock of the nightmares he suffered since I can remember.

By Hannah Jackson

By Hannah Coates

By Christian Allaire

When they first came to Wisconsin—that desolate, frozen tundra—my mother and father decided to have no family holidays at all. They didn’t believe in American customs. The idea of a fat white man in a red suit sliding down the chimney was entirely bizarre to them. As for Lunar New Year, celebrated by more people than any other holiday in the world, almost no one in Appleton, Wisconsin, knew the slightest thing about it. The gathering of family, the making of sticky rice cakes, the noise and celebration of the New Year in diasporic communities all over the world meant nothing to the people around us.

But after a year, my parents realized how important it was to have something to look forward to. Our family began to celebrate not only the Lunar New Year, but Christmas and Thanksgiving as well. With the arrival of more Chinese families in our town, we gathered with them for a big meal on New Year’s Eve. My mother exchanged rumors on the coming year’s horoscopes with the other mothers, finding a lot to discuss even after my oldest sister, the Horse, was happily married.

Now, as a Chinese American living and teaching at a university in the Midwest, Lunar New Year is a cultural holiday I observe and try to share with my coworkers, friends, and family—a cause for celebration in the coldest, darkest part of winter. I accept my parents’ customs as a way of showing my love for them, my loyalty to them and their experience. Because I live in another small Midwestern city, celebrating Lunar New Year has meant learning to share my rituals with people I love to whom the traditions are not familiar. I’ve also explained these customs to my biracial daughter, who is one generation more removed from my parents and their world.

This New Year’s Eve, I don’t know if I’ll have time to clean the house. But I will set aside an hour for my bathroom ritual. I’ll schedule family haircuts, and send emails reminding non-Chinese friends to wash, clip, and snip. And even though next year will not be a Dragon year, I’ll riffle through the cabinets at work to dig up a worn stuffed dragon, the gilt rubbing off its wings, that was given to me as a New Year gift by a beloved and now deceased mentor. I’ll invite interested students to help me throw a party. We’ll decorate the place with the dragon, red signs, cartoon animals, and streamers. We’ll buy oranges and gold foil-covered chocolate coins. Then we’ll host a big, boisterous Chinese lunch. Everyone will eat, make noise, and scare away demons. They’ll take out their phones and look up their birth animals, and try to predict what will happen to them in the Year of the Rabbit. The following day, I will put on something red, so the Money God can see me, and I will go outside to walk in all directions.

Lan Samantha Chang is the author of the novel The Family Chao .

In this story: hair, Charlie Le Mindu; makeup, Fara Homidi. Produced by Hen’s Tooth Productions. Set Design: Griffin Stoddard.

Essay: This Chinese New Year, Make Noise, Be Brave, Create Your Own Luck

Chinese New Year celebrations are all about new beginnings and fresh starts. The new year is a time of hope and good luck.

How one spends the first day of the new year is supposed to foretell how the rest of the year will go. On Lunar New Year’s Day — this past Saturday — parents are not supposed to scold their children, brothers and sisters are not supposed to argue, and (pro tip) no one is supposed to cook or you will end up scolding, arguing, or cooking all year.

Some say that the first person to come visit your house on Lunar New Year’s Day will foretell what the new year will bring. Instead of leaving it up to chance, some people actually arrange for a rich person to come to their door first thing to ensure that their new year will be full of riches.

I am not really that superstitious, so, although I teach my children these old Chinese traditions , I am OK with occasionally nodding toward the spirit of the idea even if we do not get the letter of it exactly right.

RELATED: 10 Lunar New Year Facts to Help Answer Your Pressing Questions

Celebrated jazz pianist and composer Jon Jang is coming to town for a big concert next week. I plot — if the university has not already made plans for him — that maybe I can invite him to our house for dinner, ensuring that our new year will be filled with music, arts, and activism. Maybe I am superstitious enough to believe that this will be one small act of supernatural resistance against reportedly proposed funding cuts to the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities .

"All I want is quiet. But if the news of the past week is any indication, this is not going to be a quiet year."

But our weekend is full of soccer, academic games, Chinese school, and Chinese traditional orchestra rehearsal. Scheduling is going to be tricky. I am invited to a professor’s Lunar New Year party at which Jang will be a guest. Close enough!

Music, arts, and activism may not come to our house directly, but we will be spending the year with them.

Before Lunar New Year’s Day arrives, one is supposed to settle all debts, resolve all fights, clean the house top to bottom, and wrap up the old year so that the new year can begin fresh.

Instead, I usually end up treating the Lunar New Year as an extension, an extra month or two to finish up the old calendar year before I have to start thinking about the new.

On Jan. 1 when people ask, “What are your New Year’s resolutions?” I answer, “Oh, I’m Chinese American, I still have another month.”

However, this past year, I have been feeling so overextended that I have been actively trying to pare down my commitments so that I am not obligated to too many others. During the two weeks of winter break that my children were out of school, I did not leave the house. I just sat in my kitchen, and I worked. Somehow, miraculously, I finished all of my 2016 commitments by Jan. 7, 2017, a first ever for me. I remember spending all of Jan. 8 in a daze. I had new stuff I could do, but there were no emergencies, no fires to put out. Then school started again on Jan. 9 and we were back to frantic freneticism.

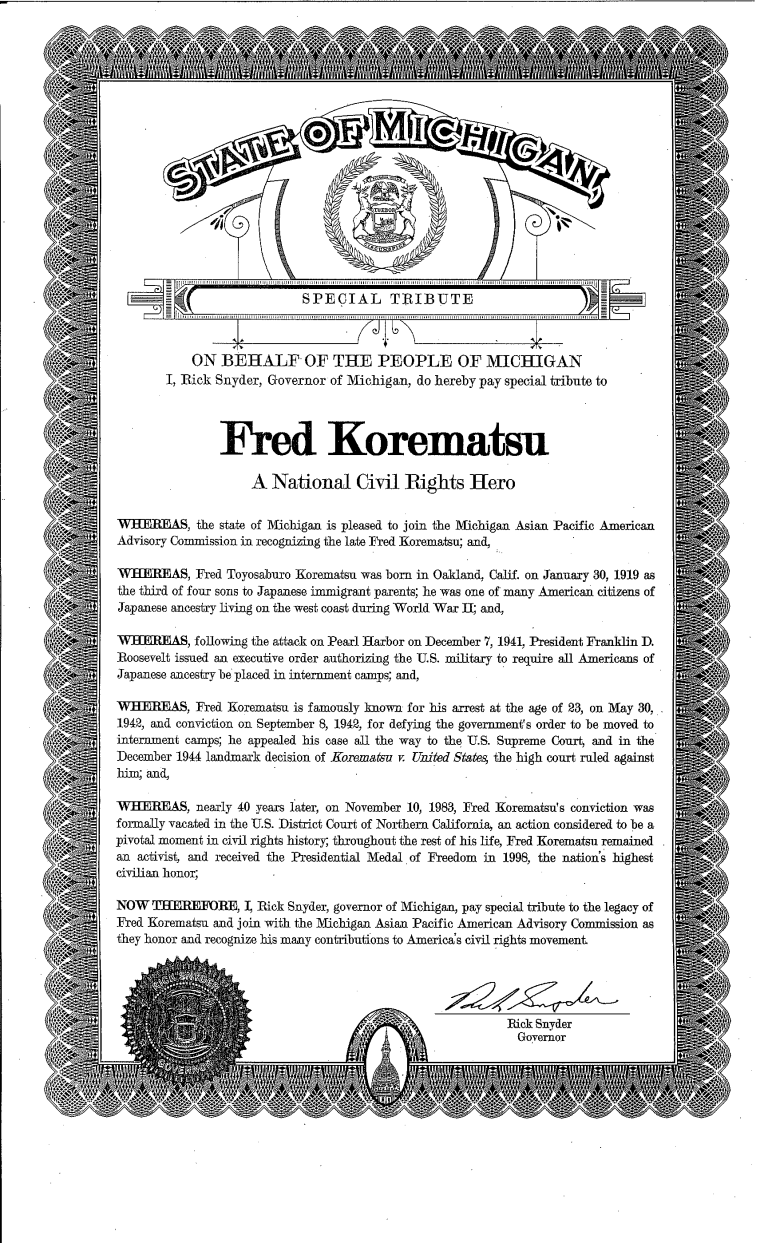

RELATED: New Book on Civil Rights Icon Fred Korematsu Challenges Youth to Speak Up for Justice

All I want is quiet.

But if the news of the past week is any indication, this is not going to be a quiet year.

Monday, Jan. 30, is recognized by several states as the Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution . Korematsu challenged the constitutionality of the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, which helped pave the way for redress and reparations for the Japanese-American community in the 1980s.

Although Korematsu received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, he was also a somewhat reluctant activist. He was only 23 years old at the time and just wanted to hang out with his European-American girlfriend. Yet, once he started fighting, he wanted to make sure that the same thing could never happen to anyone again. He spent the last years of his life standing up for the Muslim-American community after the events of Sept. 11, 2001.

This year will be the 135th anniversary of the Chinese Exclusion Act , which banned Chinese from entering America from 1882 to 1943. It is also the 75th anniversary of Executive Order 9066 , which incarcerated about 120,000 Japanese Americans, two-thirds of whom were American citizens, in incarceration camps during World War II. It is also the 35th anniversary of the baseball bat beating death of Chinese American Vincent Chin by auto workers who blamed the Japanese for the troubles of the automotive industry. These events are all connected.

On Holocaust Remembrance Day, President Trump signed an executive order to ban people from several Muslim-majority countries and to halt the entry of refugees . Refugees, international students, and U.S. permanent residents — who had visas and were already in the air when the order was signed — were not allowed entry upon arrival at the airport, followed by a weekend of mass protests at airports around the country and an emergency stay of the order.

“Don’t be afraid to speak up,” Korematsu had said. “One person can make a difference, even if it takes 40 years.”

So on Monday, I will be at the law school’s Korematsu Day program — with members of the Japanese American Citizens League, American Citizens for Justice, and the Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services (ACCESS) — speaking up about this history and the importance of standing up for others, especially today.

I will be thinking about all the ways that I am privileged to speak, and I will be carrying with me the thousands of people who have been standing up, marching, and protesting for others; the dark humor and new-found resistance of historians, scientists, and park rangers; the courage of Native Americans and veterans protecting the environment at Standing Rock; the image of volunteer attorneys sitting and working on the floors of airports; and the conviction of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance who went on strike at JFK Airport Saturday in protest of the executive order.

Chinese New Year is a boisterous, magical time, with firecrackers and lion dances to scare away bad luck and evil spirits and to set the tone for the new year. Chinese New Year traditions are not about waiting and hoping for good luck to arrive, but about taking steps to make sure that it happens.

So make noise. Be brave. Create your own luck to shape this new year.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook , Twitter , Instagram and Tumblr .

- Essay: Looking to Martin Luther King Jr. Day to Light the Way Forward

- Essay: Celebrating Chinese New Year Far From Home and Family

- Essay: In the 'Las Vegas of Asia,' Lessons in How Multiculturalism Makes Community

- Essay: The Day after Election Day, What Do I Tell My Son?

Frances Kai-Hwa Wang is a freelance writer and speaker based in Michigan and Hawaii. She has been a contributor for AAPIVoices.com, NewAmericaMedia.org, ChicagoIsTheWorld.org, PacificCitizen.org and InCultureParent.com. She teaches Asian Pacific American Studies and writing and she speaks nationally on Asian Pacific American issues.

- Kelvin Smith Library

Lunar New Year: Introduction

- Research Guides

Lunar New Year

Introduction.

- Children's Books

Celebrate Lunar New Year

Happy New Year

This guide had been created for the lunar new year celebration sponsored by the International Student Services Office, the Office of Multicultural Affairs, and First Year Experience and Family Programs of CWRU.

The Gregorian calendar is followed and solar new year is an official holiday in Asian countries. But lunar new year is still the most important festival in several Southeast and Northeast Asian countries, especially among those of Chinese descent. Lunar new year marks the ending of the old and the beginning of the new year. It is on the first day of the first lunar month. In the Gregorian calendar, the festival falls somewhere between January 21 and February 19. Let's take a look at how this most important holiday is observed in different countries.

China (Spring Festival, Xin Nian)

Celebration starts from the beginning of the twelfth lunar month through the 15th day of first lunar month, the Lantern Festival. Legend tells that in ancient times, a horrible monster called "nian" (same word for "year") appeared at the end of the year, attacked people and livestock, but the villagers could not defeat it. Finally, the villagers found out the monster would be terrified by the color red and noise. People set off firecrackers, wore red clothes, hang red lanterns, and painted their homes red at the end of the year. The beast panicked and ran away. The cheerful bright red color is the most popular color for the Spring Festival.

Traditional Spring Festival events include:

Twelfth lunar month:

Day 8: Offering of Soup of the Eighth Day (Laba Gruel). Laba gruel is a thick porridge consisting of "various whole grains and/or rice with dried fruits and nuts such as dates, chestnuts, pine seeds, and raisins."

Day 23: Sending off the Kitchen God. The Kitchen God is the agent of the heavenly authority and spends the whole year with the family. On the 23rd of the last month of the lunar year, he ascends to heaven and makes a report of the family. Family present offerings, hoping the deity will speak of good things. A paper horse is set on fire as the god's steed to ascend to heaven.

Day 30: New Year's Eve (Chu xi). Fierce door Gods (Men shen) are pasted on the center panels of doors, auspicious spring scrolls/couplets (Chun lian) on each side of the front door. People sweep the house to send off misfortune. Offerings to gods and ancestors are made. Family reunion meals take place. People stay awake to safeguard the year.

First Lunar Month:

Day 1: New Year's Day. Set off firecrackers. People change into new clothes and visit elders. Elders pass out red envelopes (Hong bao) containing "lucky money" (Ya sui qian). Burn incense and worship deities in temples.

Days 1-5: Relatives/friends visits. Traditional new year food includes meat dumplings (Jiao zi), fish and sweet steamed glutinous rice pudding (Nian gao). Fruits, nuts and seeds are popular snacks, conveying "wishes for fertility and long life." Especially in the south part of China, flowers such as lotus, camellia, hand citron and narcissus are used to decorate home.

Day 15: the Lantern Festival Day (Deng jie) or the Feast of the First Full Moon (Yuanxiao jie). A wild variety of lanterns are displayed. People go to the streets and view processions of stilt walkers, lions dances, dragon parade and opera performances. Sweet-tasting glutinous rice flour balls called Yuan xiao, is consumed in every household.

- Chang, Mei-Yen. "Lunar New Year In Taiwan." International Journal Of Education Through Art 6.1 (2010): 41-57.

- Stepanchuk, Carol and Wong, Charles. Mooncakes and Hungary Ghosts: Festivals of China. San Francisco: China Books & Periodicals, 1991.

Vietnam (Tet Nguyen Dan or Tet)

Tet is the most important annual festival in Vietnam, both culturally and spiritually. It is marked by a four-day public holiday. But the preparation for Tet starts a full month ahead and continues until the seventh day of the new year. About ten to fifteen days before Tet, people begin shopping for the holiday. Square or hexagonal cardboard candy box bearing "Happy New Year" is a must-have for every household on its ancestral altar. A great variety of calendars are available in the market and hung in every house as an ornament. Calendars have almost replaced the old custom of hanging couplets in Chinese calligraphy. Flowering branches and small trees are brought into homes during the holidays. The favorites are peach branches and small potted mandarin trees. The apricot blossom or mai flower is very popular in the South.

In tradition, Tet commences on the twenty-third day of the twelfth month when the Kitchen Gods, the three Ong Tao, are worshiped and travel to heaven to give an annual report of the family they inhabit. A bowl of three small carps is offered to be ridden by the gods for their journey to see the Heavenly King. Rice cake is an essential food to Tet for offering on ancestral altars and giving as gift exchanges between kins and friends. Cylindrical rice cakes (Banh tet) are popular in the South, while square rice cakes (Banh chung) are popular in the North. In the past, it was a tedious task to make rice cakes as people boiled the cakes ten to twelve hours over fires in a large open space. Today rice cakes can be bought in shops or ordered in advance. "Five-fruit tray" (Mam ngu qua) is another common offering on the ancestral altar, which symbolizes the "good fortune and prosperity hoped for" in the new year.

On the twenty-fifth or twenty-sixth day of the last lunar month, ancestral graves are visited and tidied. In the late afternoon of the last day of the old year or the first day of the new year, families hold a ceremony to "honor the ancestors and invite them to enjoy Tet with the living family." The ancestors will protect the family throughout the new year. Family will visit father's or mother's lineages on the first and second days, and visit teachers or former teachers on the third day of Tet. On the first day of the new year, temples and shrines are full of people. Religious activities also take place at certain sites dedicated to former national or regional heroes.

In rural area, a neu tree, "a long bamboo pole with a pineapple at the top, decorated with a bell, lantern, and flags," would be raised outside the house once the Kitchen God has been sent off. Taking down of the neu tree marks the ending of the celebration on the seventh day of the first lunar month.

- Nguyen, Van Huy. "Tet holidays: ancestral visits and spring journeys." Vietnam: Journeys of Body, Mind, and Spirit. 71-91. Berkeley, CA: U of California P, with American Museum of Natural History, New York; Vietnam Mu

- McAllister, Patrick. "Religion, The State, And The Vietnamese Lunar New Year." Anthropology Today 29.2 (2013): 18-22.

- McAllister, Patrick. "Connecting Places, Constructing Tết: Home, City And The Making Of The Lunar New Year In Urban Vietnam." Journal Of Southeast Asian Studies 43.1 (2012): 111-132.

Lunar new year celebration starts on the first and ends on the fifteenth day of the first lunar month. Home is cleaned and tidied for the new year. On new year's eve, family will enjoy a festive meal together. On New Year's Day, younger generation will visit elders and elders will distribute cash in red envelopes. Visitors will bring two mandarin oranges as new year's gifts, since the name of orange sounds like "good fortune" and "gold (financial wellbeing)." In return, guests will get back two oranges when they leave, conveying blessings for the new year. Streets in Chinatown are beautifully and lavishly lit, and lanterns are hang up. Dragon dance, lion dance, fireworks and fire-eating performance are popular activities.

- The official site of Singapore Tourism Board: Chinese New year. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- Chinese Encyclopedia Online: Singapore Lunar New Year Rites. Retrieved January 24, 2019 (Translated by the author).

Korea (Seollal)

Seollal (Korean New Year) is a three-day national holiday and focuses on family. People spend a lot of time shopping for ancestral rites and gifts. Thousands of travelers are heading for their hometowns and transportation can be time-consuming.

The day before Seollal, family members gather together to prepare the holiday food. Tteokguk (rice cake soup) is the most important food for both ancestral rites and the New Year meal (Sechan). Rice cake (Tteok) used for tteokguk is prepared by "steaming non-glutinous rice flour, pounding the dough with a mallet until it is firm and stick, and then shaping it into the form of a rope." The shape of a long rope signifies an expansion of good fortune in the new year. Seollal food preparation requires long hours of work. Nowadays, ready-made food can be purchased or delivered to home.

On the morning of Seollal, people dress in new clothing, especially Korea's traditional costume (Hanbok). Then the families gather to perform ancestral rites to pay respect to ancestors and pray for good fortune in the new year (Charye ritual). It is believed that ancestors will return to enjoy the holiday food. After the ancestral rites, family share the holiday food together. According to Korean tradition, eating tteokguk on Seollal adds one year to your age. After the meal, the younger generations will bow deeply to the elders to show respect. In return, the elders will offer good wishes along with gifts of money (Sebaetdon). Family members play traditional folk games and share stories. The most common activity is Yutnori, a board game that involves throwing four wooden sticks.

- Paik, Jae-eun. "Tteokguk, Rice Cake Soup." Koreana 21.4 (2007): 76-79.

- The Official Site of Korean Tourism Organization: Learn Traditional Culture to Celebrate Seollal! Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- The Official Site of Korean Tourism Organization: Celebrating Seollal in Korea: A Glimpse of Local Customs. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

Lunar new year is the most important holiday for Chinese Malaysians. The celebration starts from Winter Solstice and and lasts until the fifteenth of the first lunar month. Chinatown in Kuala Lumpur is decorated with red color lanterns and crowded with shoppers. On New Year's Eve, a family reunion dinner will be held. People will stay awake to safeguard the year and light fireworks. On New Year's Day, Chinese Malaysians open their homes for visits from friends of other religions and races. Sweeping the floor on New Year's Day is forbidden as good fortune will be swept away. Bad language and unpleasant topics are strictly discouraged. Relatives and friends will visit each other from the second day of the new year.Yee Sang is a special dish that is only served during Chinese New Year, conveying wishes for prosperity, health and good luck in the new year. Dragon and lion dances are held in Chinatown and there are many prayers in temples. On the fifteenth day of the first lunar month (Chap Goh Mei, known as Chinese Valentine's Day), young unmarried women will throw tangerines into the sea, wishing to find a good husband.

- Wonderful Malaysia, "Chinese New Year in Malaysia." Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- How the Spring Festival is Celebrated in Singapore and Among Chinese Malaysians." Retrieved January 24, 2019 (Translated by the author).

- Lim, Audrey. "Chap Goh Mei." Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- NPR: Yusheng: A Dish To Toss In The air To Celebrate The Chinese New Year.

On New Year's eve, Thai Chinese will hold ancestral rites, offer fruits, taro, sweets and other dishes on the altar, and burn incense. After ancestral worship, family will enjoy reunion meal together. On New Year's Day, Thai Chinese will pay pilgrimage to temples and pray for favorable climatic weathers and good wellbeing in the new year. Chinatown in Bangkok is decorated with lanterns, and dragon parades and lion dances are held.

- "How Thai Chinese Celebrate the Spring Festival." Retrieved January 24, 2019 (Translated by the author).

- Bao, Jiemin. "Chinese in Thailand." Encyclopedia of Diasporas : Immigrant and Refugee Cultures around the World. New York ; London : Kluwer Academic/Plenum, 2004, p. 757.

Philippines

Lunar New Year was announced as a public holiday in 2012 in the Philippines. Lunar new year is the most prominent celebration for Chinese Filipinos. People participate in dragon and lion dances in Chinatown and enjoy Chinese opera performance. Tikoy (sticky rice cake) giving is a tradition and is only available for purchase in stores around Lunar New Year time. Red envelopes containing luck money (Ang pao) are distributed to children.

- Ang See, Teresita. "Chinese in the Philippines." Encyclopedia of Diasporas : Immigrant and Refugee Cultures around the World. New York ; London : Kluwer Academic/Plenum, 2004, p. 767.

- "Chinese New Year Celebrated in the Philippines." Asia Society. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

Japan (Shogatsu, 正月)

Since 1873, the official and cultural Japanese New Year has been celebrated on January first based on the Gregorian calendar. Kadomatsu, the bouquet of pine and bamboo which stands for longevity and righteousness, stand before entrance as new year's decoration. Twisted straw rope (Shimenawa) is put over doors of the house to "bring good luck and keep evil out." New crops and mochi (rice cakes) are offered to gods in thanks and people pray for good harvests in the new year. Osechi is a special cooking for new year prepared in a four-tiered lacquered box. From new years's eve to the seventh day of January, Japanese people pay their first pilgrimage of the year to shrines or temples and pray for good fortune in the new year (Hatsumode). Children receive pocket money (Otoshidama) from parents and kins. Kite-flying is a popular play for boys, and battledore and shuttlecock for girls.

- Japan. Kokusai Kankokyoku. Annual Events in Japan. Tokyo Board of Tourist Industry: Japanese Government Railways, 1938.

- Next: Children's Books >>

- Last Updated: Sep 28, 2023 2:12 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.case.edu/lunar-new-year

Chinese New Year – Few lines, Short Essay and Full Essay

Essays , Festivals 0

Last Updated on January 25, 2020

Few lines about Chinese New Year

- Chinese new year is also known as Lunar new year

- It is a Chinese festival celebrating the beginning of a new year of the Chinese calendar.

- In mainland china, the day marks the onset of spring and is referred as the Spring Festival.

- In 2020, the Chinese New Year is celebrated on 25th January and it’s a public holiday.

- This Chinese year is called the Year of the Rat.

Brief essay on Chinese New Year

Chinese New Year is a well-known Chinese festival that celebrates the beginning of a new year of the Chinese calendar. It is also known as lunar New Year or the Spring Festival as it marks the onset of spring. The first day of Chinese New Year begins on the new moon day that happens between 21 January and 20 February. In 2020 the Chinese New Year is celebrated on 25th January commencing the Year of the Rat. Chinese New Year is an important holiday in China and the festival is also celebrated worldwide in regions with significant Chinese populations.

Long Essay on Chinese New Year

Chinese New Year marks the beginning of a new year in the Chinese calendar. It is also termed as “Lunar New Year”, “Chinese New Year Festival”, and “Spring Festival”. Generally, the Chinese New Year falls on different dates every year in the Gregorian calendar. It is calculated based on the first new moon day that falls between 21th of January and 20th of February.

Chinese New Year celebrations starting from the New Year eve and ends with the Lantern festival that is held on the 15th day of the year. Chinese New Year is observed as a public holiday in china and in several countries with sizable Chinese and Korean population. It is the longest holidays in china. The holidays mark the end of the winter’s coldest days and people welcome the spring, praying to Gods for the upcoming planting and harvest season.

Different regional customs and traditions accompany the festival. Eating dumplings, Yule Log cake, tang yuan or ‘soup balls’, and red envelopes with ‘lucky’ money are part of customary celebration. According to some Myth, the Chinese New Year festival celebrates the death of a monster called Nian, which was killed by a brave boy with fire crackers on the New Year’s Eve. And that’s why firecrackers is considered the crucial part of the Spring Festival as it is believed to scare off monsters and bad luck.

This year, 2020, Chinese New Year falls on 25th of January is called the year of the Rat.

Related Worksheets and Exercises

- St Patrick’s Day Essay

- Favorite Festival – Diwali

- What is Black Friday? Why we call it Black Friday?

- Rakshabandhan 2017

- Thiruvalluvar Day

- Pongal Festival

- Happy New Year

- Guru Nanak Jayanthi

- Rakshabandhan

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

TRAVEL GUIDES

Popular cities, explore by region, featured guide.

Japan Travel Guide

Destinations.

A Creative’s Guide to Thailand

Creative resources, photography, videography, art & design.

7 Tips to Spice up Your Photography Using Geometry

GET INVOLVED

EXPERIENCES

#PPImagineAZ Enter to Win a trip to Arizona!

The journal, get inspired, sustainability.

How to Be a More Responsible Traveler in 2021

Asia , china , travel stories, everything you need to know about lunar new year.

- Published February 11, 2021

Lunar New Year is the most important celebration in China and venerated across other Asian cultures as well, a fact that often goes missing in western interpretations of the event. Lasting for 15 days, the festival is packed with culture, well-wishes, and plenty of good food.

If you’re curious about the Lunar New year, here’s a glimpse into the traditions and customs of the festival, and some advice on how to prepare for and celebrate the holiday.

Chinese New Year is the annual celebration of spring that consists of two weeks of festivities, with most activities taking place on New Year’s Eve, New Year’s Day, and during the Lantern Festival (the closing day of celebrations).

The date of Chinese New Year changes every year, as it is based on the lunar calendar (for 2021, New Year’s Day falls on February 12th). While the Western Gregorian calendar is based on the Earth’s orbit around the sun, the date of Chinese New Year is determined by the moon’s orbit around the Earth. Chinese New Year always falls on the second new moon after the winter solstice. Thus, Chinese New Year is sometimes referred to as the Lunar New Year or the Spring Festival. Each lunar year also has a corresponding animal from the Chinese Zodiac (2021 will be the Year of the Ox).

The two main objectives of the festival are to celebrate a year of hard work and wish for a lucky and prosperous year ahead. It is widely believed that a good start to the year will lead to a lucky year and, therefore, what you choose to do on the first day of the lunar year affects your luck for the rest of the year.

A BIT OF HISTORY

The centuries-old legend of the origin of Chinese New Year varies from teller to teller, but they all include a story about a mythical monster who preyed on villagers. The lion-like monster’s name was Nian , which is also the Chinese word for “year.” The stories also include a wise old man who advises the villagers to ward off Nian by making loud noises with drums and firecrackers, and by hanging red scrolls from their doors. In the end, the villagers take the wise man’s advice and Nian is conquered. On the anniversary of the date, the Chinese recognize the “passing of the Nian,” known in Chinese as guo nian , which is synonymous with celebrating the new year.

LOCAL TRADITIONS

Reunion and togetherness are the main sentiments of the Chinese New Year festival, so most people make the journey back to their hometowns to celebrate with their families. This triggers the world’s largest human migration (aka the “spring movement”), as hundreds of millions flood China’s roads and public transportation networks. After what can be a long and arduous journey, the festivities begin, and many partake in “spring cleaning,” put up decorations, and buy new clothing for the new year celebrations.

There are many cultural activities arranged during the festival: firecrackers are lit, drums can be heard on the streets, red lanterns glow at night, and paper cutouts are hung from doorways. Although rural areas and small towns retain more traditional celebrations compared to urban areas, the major cities hold Chinese New Year parades with dragon and lion dances.

On the first day of the new year, individuals greet one another with “ gongxi ” (pronounced gong-shee), which translates to “respectful joy” or “best wishes.” This greeting is used to wish good luck and happiness to others for the new year. It is also customary for younger generations to visit their elders and wish them health and longevity on this day.

Red Envelopes

Like Christmas in the West, gifts are exchanged during Chinese New Year. The most common of these gifts are red envelopes filled with money. The red envelopes are used to symbolize the hope and good luck given to their receivers.

Certain foods are eaten during the festival, especially during New Year’s Eve dinner. Fish is a must for new year celebrations, as the Chinese word for fish sounds similar to the word for surplus. Because of this, eating fish is believed to bring a surplus of money and good luck in the coming year. Other holiday delicacies include dumplings, spring rolls, glutinous rice cakes, and sweet rice balls.

Lion and Dragon Dances