- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

Story Elements: 7 Main Elements of a Story and 5 Elements of Plot

Krystal N. Craiker

Whether it’s a short story, novel, or play, every type of story has the same basic elements.

Today, we’re taking a look at the seven key elements of a story, as well as the five elements of plot. Knowing these essential elements will ensure that your story is well-developed and engaging.

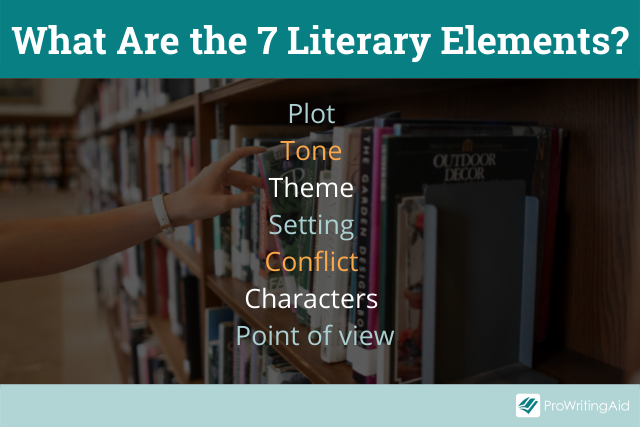

What Are the 7 Literary Elements of a Story?

What are the 5 elements of plot, conclusion: basic story elements.

There are seven basic elements of a story, and they all work together. There’s no particular order of importance because they are all necessary.

When you’re writing a story, you might start with one and develop the others later. For instance, you might create a character before you have a plot or setting.

There’s no correct place to start—as long as you have all seven elements by the end, you’ve got a story.

Every story needs characters. Your protagonist is your main character, and they are the primary character interacting with the plot and the conflict. You might have multiple protagonists or secondary protagonists. An antagonist works against your main character’s goals to create conflict.

There are short stories and even some plays that have only one character, but most stories have several characters. Not every minor character needs to be well-developed and have a story arc, but your major players should.

Your characters don’t have to be human or humanoid, either. Animals or supernatural elements can be characters, too!

Your story must take place somewhere. Setting is where and when the story takes place, the physical location and time period.. Some stories have only one setting, while others have several settings.

A story can have an overarching setting and smaller settings within it. For example, Pride and Prejudice takes place in England. Lizzy travels through several locations in the country. The smaller settings within the story include individual homes and estates, like Longbourn, Netherfield Park, and Pemberley.

Setting also includes time periods. This might be a year or an era. You can be less specific in your time period, like “modern-day” or “near future,” but it is still an important component of your setting.

Our next story element is theme. You can think of theme as the “why” behind the story. What is the big idea? Why did the author write the story, and what message are they trying to convey?

Some common themes in stories include:

- Good versus evil

- Coming of age

Themes can also be warnings, such as the dangers of seeking revenge or the effects of war. Sometimes themes are social criticisms on class, race, gender, or religion.

Tone might be the most complicated of all the story elements. Tone is the overall feeling of your story. A mystery might be foreboding. A women’s literature story might feel nostalgic. A romance might have an optimistic, romantic tone.

Tone should fit both your genre and your individual story. Create tone with writing elements such as word choice, sentence length, and sentence variety. Aspects of the setting, such as the weather, can contribute to tone, as well.

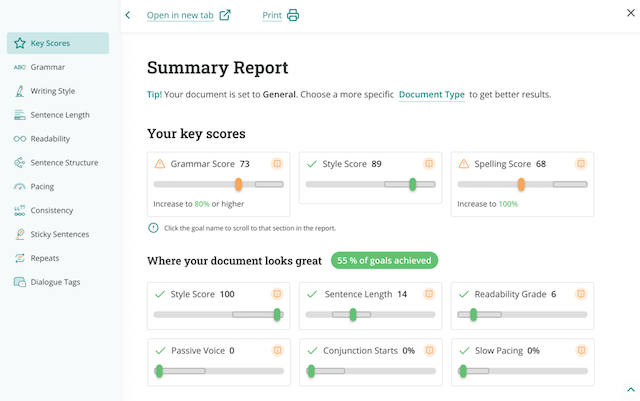

ProWritingAid can help with some of the aspects of tone. In your document settings, change your document type to your genre. The Summary Report will then compare various style aspects to your genre, such as sentence length, emotion tells, and sentence structure. These all play a role in establishing a tone that fits your genre.

Try the Summary Report with a free account.

Point of View

Every story needs a point of view (POV). This determines whether we’re seeing something from the narrator’s perspective or a character’s perspective. There are four main points of view in creative writing and literature.

First person tells the story from a character’s perspective using first person pronouns (I, me, my, mine, we, our, ours). The POV does not have to be from the perspective of the main character. For example, in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby , the narrator, Nick, is mostly an observer and participant in Gatsby and Daisy’s story.

You can also use third person limited to show the story through the eyes of one character. This point of view uses third person pronouns (he, him, his, her, hers, their, theirs). If your story features alternating points-of-view, third person limited only shows one character’s perspective at a time.

First person and third person limited points of view are sometimes referred to as deep POV .

If the story is told from the narrator’s perspective, the POV is typically third person omniscient. Omniscient means all-knowing: the narrator sees all and knows all.

Rarely, stories are written in second person (you, yours). This point of view is more common in short stories than novellas or novels. Fanfiction and choose-your-own-adventure stories use second person more often than traditional creative writing does.

Conflict is the problem that drives a story’s plot forward. The conflict is what is keeping your characters from achieving their goals. There are internal conflicts, in which the character must overcome some internal struggle. There are also external conflicts that the character must face.

There are seven major types of conflict in literature. They are:

- Man vs. man

- Man vs. nature

- Man vs. society

- Man vs. technology

- Man vs. supernatural

- Man vs. fate

- Man vs. self

Typically, a story has several small conflicts and a large, overarching internal or external conflict. While all the elements of a story are crucial, conflict is the one that makes your story interesting and engaging.

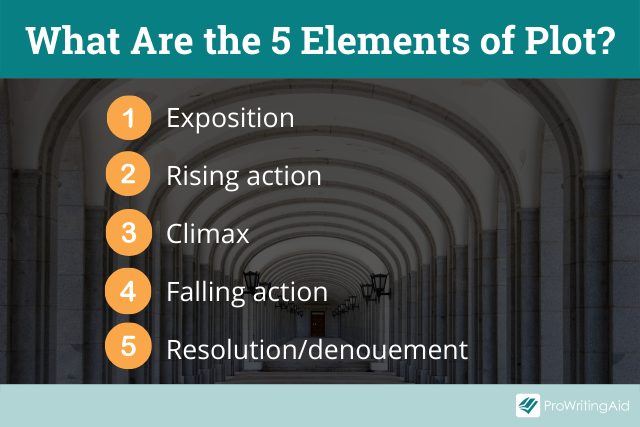

Finally, you can’t have a story without a plot. The plot is the series of events that occur in a story. It’s the beginning, middle, and end. It’s easy to confuse conflict and plot.

Plot is what happens, while conflict is the things standing in the way of different characters’ goals. The two are inextricably linked.

Plot is one of the seven elements of a story, but there are also different elements of plot. We’ll cover this in greater detail in the next section.

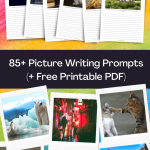

Everything, from a short story to a novel, requires not only the basic elements of a story but also the same essential elements of a plot. While there are multiple types of plot structure (e.g. three-act structure, five-act structure, hero’s journey ), all plots have the same elements. Together, these form a story arc.

Exposition sets the scene. It’s the beginning of the story where we meet our main character and see what their life is like. It also establishes the setting and tone.

Rising Action

The exposition leads to an event known as the inciting incident . This is the gateway to the rising action. This part of the story contains all of the events that lead to the culmination of all the plot points. We see most of the conflict in this section.

The climax is the height of a story. The character finally faces and usually defeats whatever the major conflict is. Tension builds through the rising action and peaks at the climax.

Sometimes, stories have more than one climax, depending on the plot structure, or if there are two different character arcs.

Falling Action

The falling action is when all the other conflicts or character arcs begin resolving. Anything that isn’t addressed in the climax will be addressed in the falling action. Just because the characters have passed the most difficult part of the plot doesn't mean everything is tied up neatly in a bow. Sometimes the climax causes new conflicts!

Resolution or Denouement

The end of a story is called the resolution or denouement. All major conflicts are resolved or purposely left open for a cliff-hanger or sequel. In many stories, this is where you find the happily ever after, but a resolution doesn’t have to be happy. It’s the ending of a story arc or plot, and all the questions are answered or intentionally unanswered.

The seven elements of a story and the five elements of plot work together to form a cohesive and complete story arc. No one element is more important than the other. If you’re writing your own story, planning each of the basic story elements and plot points is a great place to start your outline.

Are you prepared to write your novel? Download this free book now:

The Novel-Writing Training Plan

So you are ready to write your novel. excellent. but are you prepared the last thing you want when you sit down to write your first draft is to lose momentum., this guide helps you work out your narrative arc, plan out your key plot points, flesh out your characters, and begin to build your world..

Write like a bestselling author

Love writing? ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of your stories.

Krystal N. Craiker is the Writing Pirate, an indie romance author and blog manager at ProWritingAid. She sails the seven internet seas, breaking tropes and bending genres. She has a background in anthropology and education, which brings fresh perspectives to her romance novels. When she’s not daydreaming about her next book or article, you can find her cooking gourmet gluten-free cuisine, laughing at memes, and playing board games. Krystal lives in Dallas, Texas with her husband, child, and basset hound.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Narrative Writing: A Complete Guide for Teachers and Students

MASTERING THE CRAFT OF NARRATIVE WRITING

Narratives build on and encourage the development of the fundamentals of writing. They also require developing an additional skill set: the ability to tell a good yarn, and storytelling is as old as humanity.

We see and hear stories everywhere and daily, from having good gossip on the doorstep with a neighbor in the morning to the dramas that fill our screens in the evening.

Good narrative writing skills are hard-won by students even though it is an area of writing that most enjoy due to the creativity and freedom it offers.

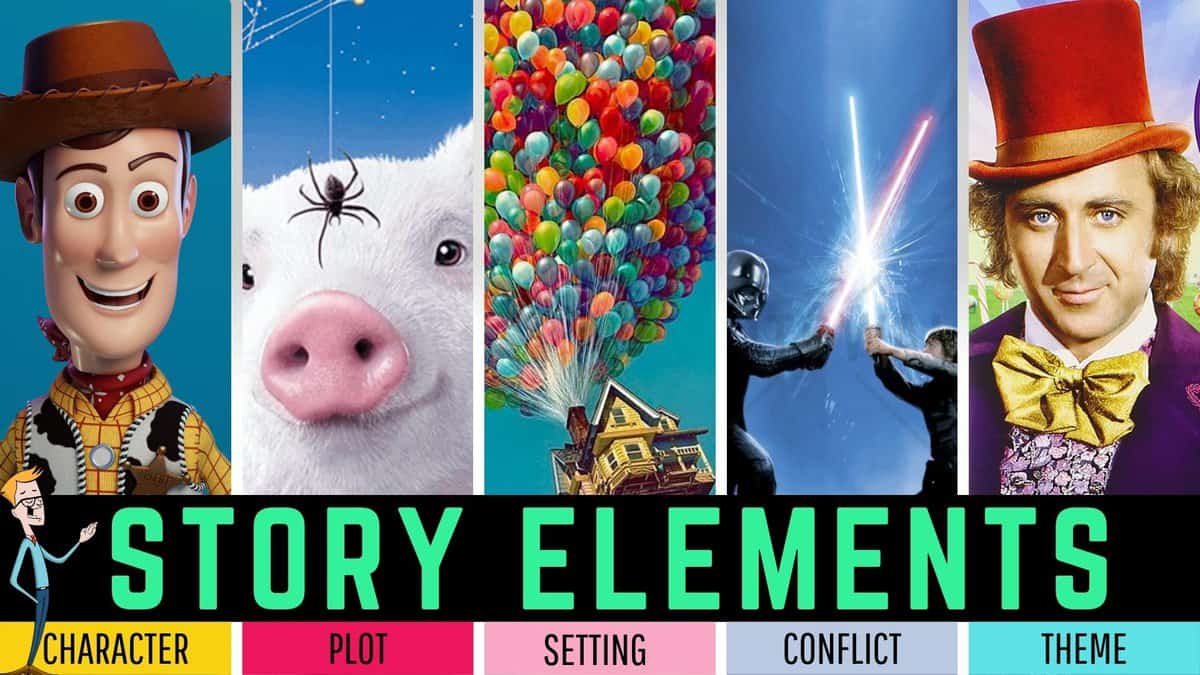

Here we will explore some of the main elements of a good story: plot, setting, characters, conflict, climax, and resolution . And we will look too at how best we can help our students understand these elements, both in isolation and how they mesh together as a whole.

WHAT IS A NARRATIVE?

A narrative is a story that shares a sequence of events , characters, and themes. It expresses experiences, ideas, and perspectives that should aspire to engage and inspire an audience.

A narrative can spark emotion, encourage reflection, and convey meaning when done well.

Narratives are a popular genre for students and teachers as they allow the writer to share their imagination, creativity, skill, and understanding of nearly all elements of writing. We occasionally refer to a narrative as ‘creative writing’ or story writing.

The purpose of a narrative is simple, to tell the audience a story. It can be written to motivate, educate, or entertain and can be fact or fiction.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING NARRATIVE WRITING

Teach your students to become skilled story writers with this HUGE NARRATIVE & CREATIVE STORY WRITING UNIT . Offering a COMPLETE SOLUTION to teaching students how to craft CREATIVE CHARACTERS, SUPERB SETTINGS, and PERFECT PLOTS .

Over 192 PAGES of materials, including:

TYPES OF NARRATIVE WRITING

There are many narrative writing genres and sub-genres such as these.

We have a complete guide to writing a personal narrative that differs from the traditional story-based narrative covered in this guide. It includes personal narrative writing prompts, resources, and examples and can be found here.

As we can see, narratives are an open-ended form of writing that allows you to showcase creativity in many directions. However, all narratives share a common set of features and structure known as “Story Elements”, which are briefly covered in this guide.

Don’t overlook the importance of understanding story elements and the value this adds to you as a writer who can dissect and create grand narratives. We also have an in-depth guide to understanding story elements here .

CHARACTERISTICS OF NARRATIVE WRITING

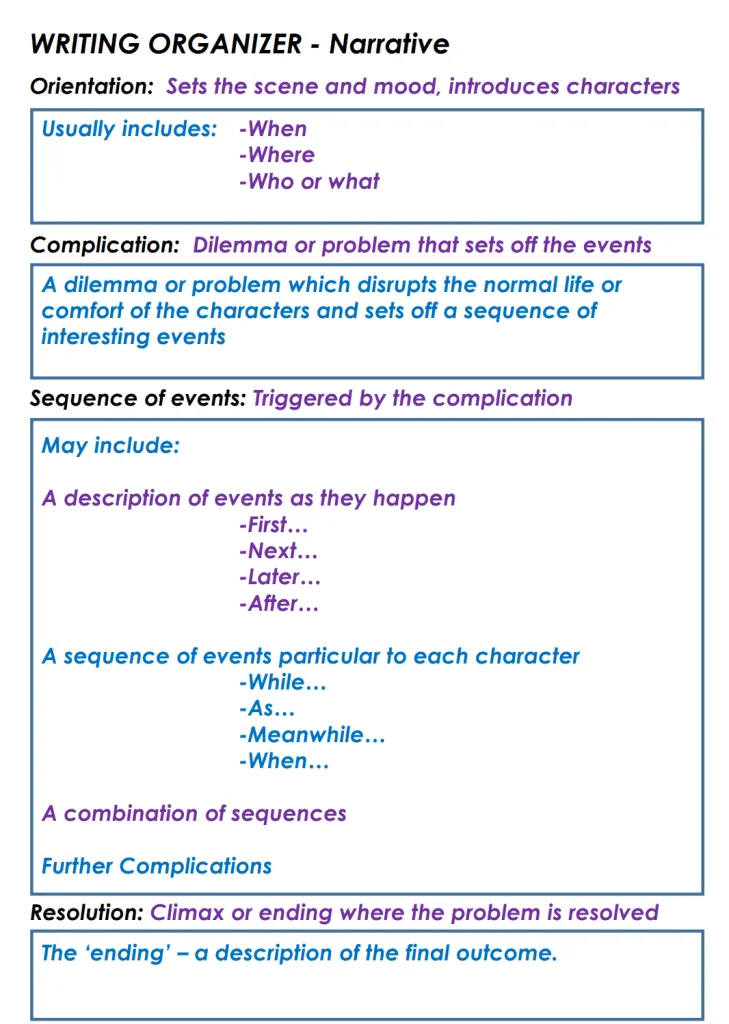

Narrative structure.

ORIENTATION (BEGINNING) Set the scene by introducing your characters, setting and time of the story. Establish your who, when and where in this part of your narrative

COMPLICATION AND EVENTS (MIDDLE) In this section activities and events involving your main characters are expanded upon. These events are written in a cohesive and fluent sequence.

RESOLUTION (ENDING) Your complication is resolved in this section. It does not have to be a happy outcome, however.

EXTRAS: Whilst orientation, complication and resolution are the agreed norms for a narrative, there are numerous examples of popular texts that did not explicitly follow this path exactly.

NARRATIVE FEATURES

LANGUAGE: Use descriptive and figurative language to paint images inside your audience’s minds as they read.

PERSPECTIVE Narratives can be written from any perspective but are most commonly written in first or third person.

DIALOGUE Narratives frequently switch from narrator to first-person dialogue. Always use speech marks when writing dialogue.

TENSE If you change tense, make it perfectly clear to your audience what is happening. Flashbacks might work well in your mind but make sure they translate to your audience.

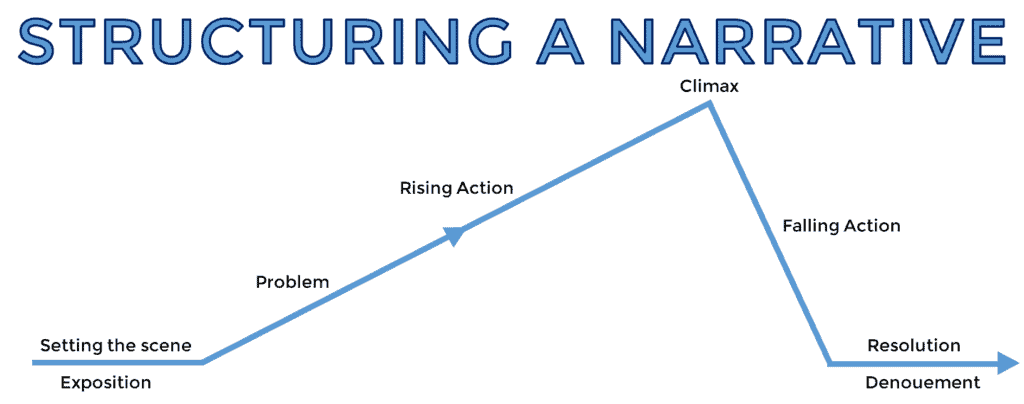

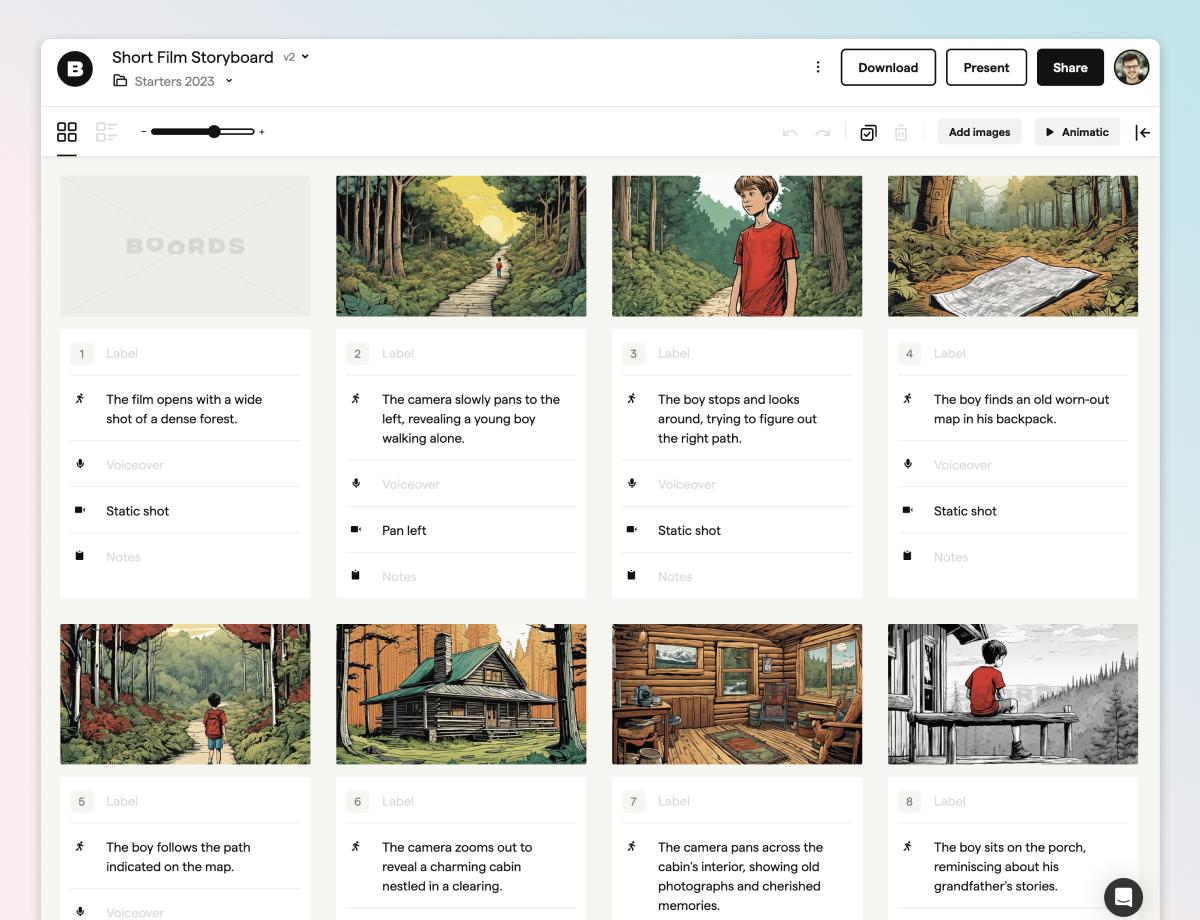

THE PLOT MAP

This graphic is known as a plot map, and nearly all narratives fit this structure in one way or another, whether romance novels, science fiction or otherwise.

It is a simple tool that helps you understand and organise a story’s events. Think of it as a roadmap that outlines the journey of your characters and the events that unfold. It outlines the different stops along the way, such as the introduction, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution, that help you to see how the story builds and develops.

Using a plot map, you can see how each event fits into the larger picture and how the different parts of the story work together to create meaning. It’s a great way to visualize and analyze a story.

Be sure to refer to a plot map when planning a story, as it has all the essential elements of a great story.

THE 5 KEY STORY ELEMENTS OF A GREAT NARRATIVE (6-MINUTE TUTORIAL VIDEO)

This video we created provides an excellent overview of these elements and demonstrates them in action in stories we all know and love.

HOW TO WRITE A NARRATIVE

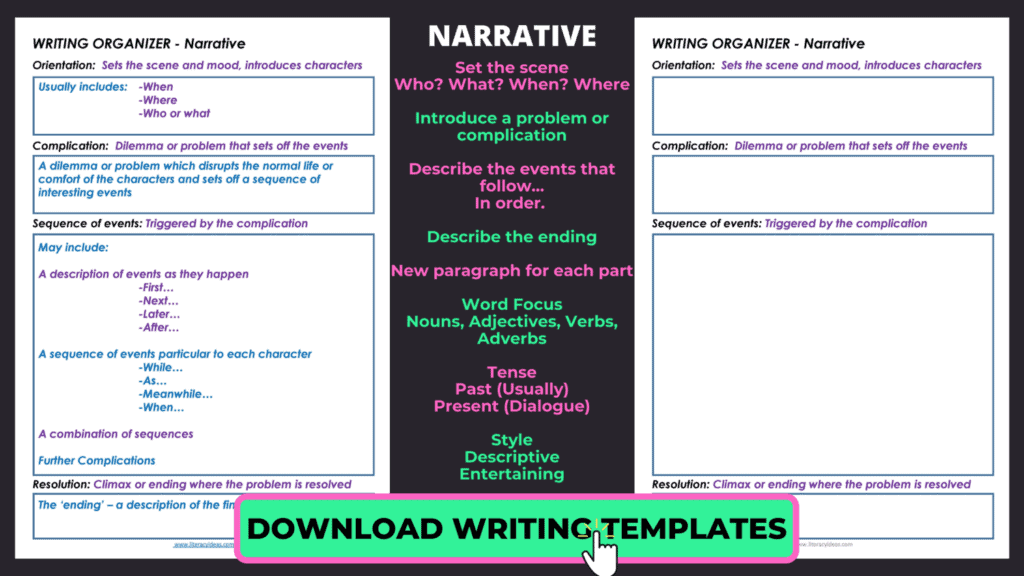

Now that we understand the story elements and how they come together to form stories, it’s time to start planning and writing your narrative.

In many cases, the template and guide below will provide enough details on how to craft a great story. However, if you still need assistance with the fundamentals of writing, such as sentence structure, paragraphs and using correct grammar, we have some excellent guides on those here.

USE YOUR WRITING TIME EFFECTIVELY: Maximize your narrative writing sessions by spending approximately 20 per cent of your time planning and preparing. This ensures greater productivity during your writing time and keeps you focused and on task.

Use tools such as graphic organizers to logically sequence your narrative if you are not a confident story writer. If you are working with reluctant writers, try using narrative writing prompts to get their creative juices flowing.

Spend most of your writing hour on the task at hand, don’t get too side-tracked editing during this time and leave some time for editing. When editing a narrative, examine it for these three elements.

- Spelling and grammar ( Is it readable?)

- Story structure and continuity ( Does it make sense, and does it flow? )

- Character and plot analysis. (Are your characters engaging? Does your problem/resolution work? )

1. SETTING THE SCENE: THE WHERE AND THE WHEN

The story’s setting often answers two of the central questions in the story, namely, the where and the when. The answers to these two crucial questions will often be informed by the type of story the student is writing.

The story’s setting can be chosen to quickly orient the reader to the type of story they are reading. For example, a fictional narrative writing piece such as a horror story will often begin with a description of a haunted house on a hill or an abandoned asylum in the middle of the woods. If we start our story on a rocket ship hurtling through the cosmos on its space voyage to the Alpha Centauri star system, we can be reasonably sure that the story we are embarking on is a work of science fiction.

Such conventions are well-worn clichés true, but they can be helpful starting points for our novice novelists to make a start.

Having students choose an appropriate setting for the type of story they wish to write is an excellent exercise for our younger students. It leads naturally onto the next stage of story writing, which is creating suitable characters to populate this fictional world they have created. However, older or more advanced students may wish to play with the expectations of appropriate settings for their story. They may wish to do this for comic effect or in the interest of creating a more original story. For example, opening a story with a children’s birthday party does not usually set up the expectation of a horror story. Indeed, it may even lure the reader into a happy reverie as they remember their own happy birthday parties. This leaves them more vulnerable to the surprise element of the shocking action that lies ahead.

Once the students have chosen a setting for their story, they need to start writing. Little can be more terrifying to English students than the blank page and its bare whiteness stretching before them on the table like a merciless desert they must cross. Give them the kick-start they need by offering support through word banks or writing prompts. If the class is all writing a story based on the same theme, you may wish to compile a common word bank on the whiteboard as a prewriting activity. Write the central theme or genre in the middle of the board. Have students suggest words or phrases related to the theme and list them on the board.

You may wish to provide students with a copy of various writing prompts to get them started. While this may mean that many students’ stories will have the same beginning, they will most likely arrive at dramatically different endings via dramatically different routes.

A bargain is at the centre of the relationship between the writer and the reader. That bargain is that the reader promises to suspend their disbelief as long as the writer creates a consistent and convincing fictional reality. Creating a believable world for the fictional characters to inhabit requires the student to draw on convincing details. The best way of doing this is through writing that appeals to the senses. Have your student reflect deeply on the world that they are creating. What does it look like? Sound like? What does the food taste like there? How does it feel like to walk those imaginary streets, and what aromas beguile the nose as the main character winds their way through that conjured market?

Also, Consider the when; or the time period. Is it a future world where things are cleaner and more antiseptic? Or is it an overcrowded 16th-century London with human waste stinking up the streets? If students can create a multi-sensory installation in the reader’s mind, then they have done this part of their job well.

Popular Settings from Children’s Literature and Storytelling

- Fairytale Kingdom

- Magical Forest

- Village/town

- Underwater world

- Space/Alien planet

2. CASTING THE CHARACTERS: THE WHO

Now that your student has created a believable world, it is time to populate it with believable characters.

In short stories, these worlds mustn’t be overpopulated beyond what the student’s skill level can manage. Short stories usually only require one main character and a few secondary ones. Think of the short story more as a small-scale dramatic production in an intimate local theater than a Hollywood blockbuster on a grand scale. Too many characters will only confuse and become unwieldy with a canvas this size. Keep it simple!

Creating believable characters is often one of the most challenging aspects of narrative writing for students. Fortunately, we can do a few things to help students here. Sometimes it is helpful for students to model their characters on actual people they know. This can make things a little less daunting and taxing on the imagination. However, whether or not this is the case, writing brief background bios or descriptions of characters’ physical personality characteristics can be a beneficial prewriting activity. Students should give some in-depth consideration to the details of who their character is: How do they walk? What do they look like? Do they have any distinguishing features? A crooked nose? A limp? Bad breath? Small details such as these bring life and, therefore, believability to characters. Students can even cut pictures from magazines to put a face to their character and allow their imaginations to fill in the rest of the details.

Younger students will often dictate to the reader the nature of their characters. To improve their writing craft, students must know when to switch from story-telling mode to story-showing mode. This is particularly true when it comes to character. Encourage students to reveal their character’s personality through what they do rather than merely by lecturing the reader on the faults and virtues of the character’s personality. It might be a small relayed detail in the way they walk that reveals a core characteristic. For example, a character who walks with their head hanging low and shoulders hunched while avoiding eye contact has been revealed to be timid without the word once being mentioned. This is a much more artistic and well-crafted way of doing things and is less irritating for the reader. A character who sits down at the family dinner table immediately snatches up his fork and starts stuffing roast potatoes into his mouth before anyone else has even managed to sit down has revealed a tendency towards greed or gluttony.

Understanding Character Traits

Again, there is room here for some fun and profitable prewriting activities. Give students a list of character traits and have them describe a character doing something that reveals that trait without ever employing the word itself.

It is also essential to avoid adjective stuffing here. When looking at students’ early drafts, adjective stuffing is often apparent. To train the student out of this habit, choose an adjective and have the student rewrite the sentence to express this adjective through action rather than telling.

When writing a story, it is vital to consider the character’s traits and how they will impact the story’s events. For example, a character with a strong trait of determination may be more likely to overcome obstacles and persevere. In contrast, a character with a tendency towards laziness may struggle to achieve their goals. In short, character traits add realism, depth, and meaning to a story, making it more engaging and memorable for the reader.

Popular Character Traits in Children’s Stories

- Determination

- Imagination

- Perseverance

- Responsibility

We have an in-depth guide to creating great characters here , but most students should be fine to move on to planning their conflict and resolution.

3. NO PROBLEM? NO STORY! HOW CONFLICT DRIVES A NARRATIVE

This is often the area apprentice writers have the most difficulty with. Students must understand that without a problem or conflict, there is no story. The problem is the driving force of the action. Usually, in a short story, the problem will center around what the primary character wants to happen or, indeed, wants not to happen. It is the hurdle that must be overcome. It is in the struggle to overcome this hurdle that events happen.

Often when a student understands the need for a problem in a story, their completed work will still not be successful. This is because, often in life, problems remain unsolved. Hurdles are not always successfully overcome. Students pick up on this.

We often discuss problems with friends that will never be satisfactorily resolved one way or the other, and we accept this as a part of life. This is not usually the case with writing a story. Whether a character successfully overcomes his or her problem or is decidedly crushed in the process of trying is not as important as the fact that it will finally be resolved one way or the other.

A good practical exercise for students to get to grips with this is to provide copies of stories and have them identify the central problem or conflict in each through discussion. Familiar fables or fairy tales such as Three Little Pigs, The Boy Who Cried Wolf, Cinderella, etc., are great for this.

While it is true that stories often have more than one problem or that the hero or heroine is unsuccessful in their first attempt to solve a central problem, for beginning students and intermediate students, it is best to focus on a single problem, especially given the scope of story writing at this level. Over time students will develop their abilities to handle more complex plots and write accordingly.

Popular Conflicts found in Children’s Storytelling.

- Good vs evil

- Individual vs society

- Nature vs nurture

- Self vs others

- Man vs self

- Man vs nature

- Man vs technology

- Individual vs fate

- Self vs destiny

Conflict is the heart and soul of any good story. It’s what makes a story compelling and drives the plot forward. Without conflict, there is no story. Every great story has a struggle or a problem that needs to be solved, and that’s where conflict comes in. Conflict is what makes a story exciting and keeps the reader engaged. It creates tension and suspense and makes the reader care about the outcome.

Like in real life, conflict in a story is an opportunity for a character’s growth and transformation. It’s a chance for them to learn and evolve, making a story great. So next time stories are written in the classroom, remember that conflict is an essential ingredient, and without it, your story will lack the energy, excitement, and meaning that makes it truly memorable.

4. THE NARRATIVE CLIMAX: HOW THINGS COME TO A HEAD!

The climax of the story is the dramatic high point of the action. It is also when the struggles kicked off by the problem come to a head. The climax will ultimately decide whether the story will have a happy or tragic ending. In the climax, two opposing forces duke things out until the bitter (or sweet!) end. One force ultimately emerges triumphant. As the action builds throughout the story, suspense increases as the reader wonders which of these forces will win out. The climax is the release of this suspense.

Much of the success of the climax depends on how well the other elements of the story have been achieved. If the student has created a well-drawn and believable character that the reader can identify with and feel for, then the climax will be more powerful.

The nature of the problem is also essential as it determines what’s at stake in the climax. The problem must matter dearly to the main character if it matters at all to the reader.

Have students engage in discussions about their favorite movies and books. Have them think about the storyline and decide the most exciting parts. What was at stake at these moments? What happened in your body as you read or watched? Did you breathe faster? Or grip the cushion hard? Did your heart rate increase, or did you start to sweat? This is what a good climax does and what our students should strive to do in their stories.

The climax puts it all on the line and rolls the dice. Let the chips fall where the writer may…

Popular Climax themes in Children’s Stories

- A battle between good and evil

- The character’s bravery saves the day

- Character faces their fears and overcomes them

- The character solves a mystery or puzzle.

- The character stands up for what is right.

- Character reaches their goal or dream.

- The character learns a valuable lesson.

- The character makes a selfless sacrifice.

- The character makes a difficult decision.

- The character reunites with loved ones or finds true friendship.

5. RESOLUTION: TYING UP LOOSE ENDS

After the climactic action, a few questions will often remain unresolved for the reader, even if all the conflict has been resolved. The resolution is where those lingering questions will be answered. The resolution in a short story may only be a brief paragraph or two. But, in most cases, it will still be necessary to include an ending immediately after the climax can feel too abrupt and leave the reader feeling unfulfilled.

An easy way to explain resolution to students struggling to grasp the concept is to point to the traditional resolution of fairy tales, the “And they all lived happily ever after” ending. This weather forecast for the future allows the reader to take their leave. Have the student consider the emotions they want to leave the reader with when crafting their resolution.

While the action is usually complete by the end of the climax, it is in the resolution that if there is a twist to be found, it will appear – think of movies such as The Usual Suspects. Pulling this off convincingly usually requires considerable skill from a student writer. Still, it may well form a challenging extension exercise for those more gifted storytellers among your students.

Popular Resolutions in Children’s Stories

- Our hero achieves their goal

- The character learns a valuable lesson

- A character finds happiness or inner peace.

- The character reunites with loved ones.

- Character restores balance to the world.

- The character discovers their true identity.

- Character changes for the better.

- The character gains wisdom or understanding.

- Character makes amends with others.

- The character learns to appreciate what they have.

Once students have completed their story, they can edit for grammar, vocabulary choice, spelling, etc., but not before!

As mentioned, there is a craft to storytelling, as well as an art. When accurate grammar, perfect spelling, and immaculate sentence structures are pushed at the outset, they can cause storytelling paralysis. For this reason, it is essential that when we encourage the students to write a story, we give them license to make mechanical mistakes in their use of language that they can work on and fix later.

Good narrative writing is a very complex skill to develop and will take the student years to become competent. It challenges not only the student’s technical abilities with language but also her creative faculties. Writing frames, word banks, mind maps, and visual prompts can all give valuable support as students develop the wide-ranging and challenging skills required to produce a successful narrative writing piece. But, at the end of it all, as with any craft, practice and more practice is at the heart of the matter.

TIPS FOR WRITING A GREAT NARRATIVE

- Start your story with a clear purpose: If you can determine the theme or message you want to convey in your narrative before starting it will make the writing process so much simpler.

- Choose a compelling storyline and sell it through great characters, setting and plot: Consider a unique or interesting story that captures the reader’s attention, then build the world and characters around it.

- Develop vivid characters that are not all the same: Make your characters relatable and memorable by giving them distinct personalities and traits you can draw upon in the plot.

- Use descriptive language to hook your audience into your story: Use sensory language to paint vivid images and sequences in the reader’s mind.

- Show, don’t tell your audience: Use actions, thoughts, and dialogue to reveal character motivations and emotions through storytelling.

- Create a vivid setting that is clear to your audience before getting too far into the plot: Describe the time and place of your story to immerse the reader fully.

- Build tension: Refer to the story map earlier in this article and use conflict, obstacles, and suspense to keep the audience engaged and invested in your narrative.

- Use figurative language such as metaphors, similes, and other literary devices to add depth and meaning to your narrative.

- Edit, revise, and refine: Take the time to refine and polish your writing for clarity and impact.

- Stay true to your voice: Maintain your unique perspective and style in your writing to make it your own.

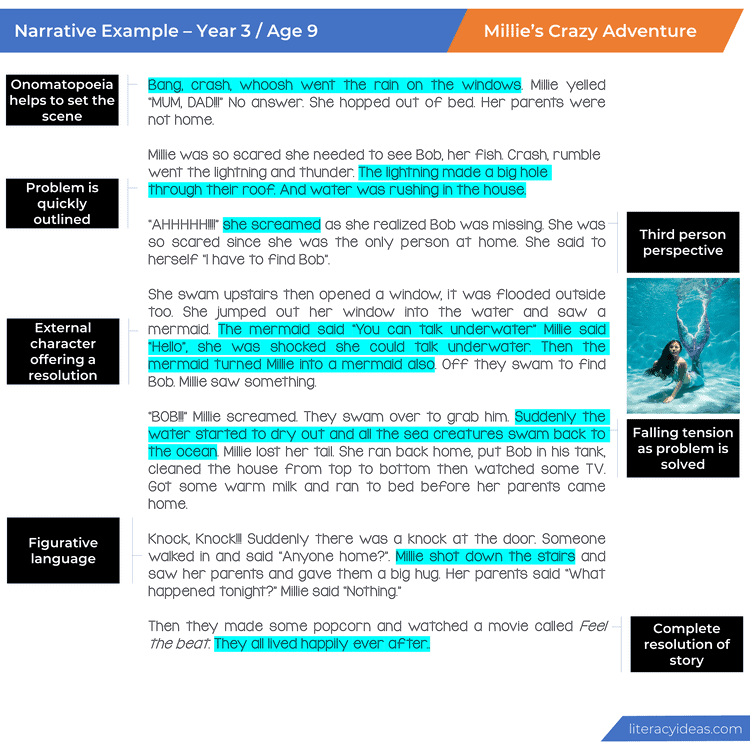

NARRATIVE WRITING EXAMPLES (Student Writing Samples)

Below are a collection of student writing samples of narratives. Click on the image to enlarge and explore them in greater detail. Please take a moment to read these creative stories in detail and the teacher and student guides which highlight some of the critical elements of narratives to consider before writing.

Please understand these student writing samples are not intended to be perfect examples for each age or grade level but a piece of writing for students and teachers to explore together to critically analyze to improve student writing skills and deepen their understanding of story writing.

We recommend reading the example either a year above or below, as well as the grade you are currently working with, to gain a broader appreciation of this text type.

NARRATIVE WRITING PROMPTS (Journal Prompts)

When students have a great journal prompt, it can help them focus on the task at hand, so be sure to view our vast collection of visual writing prompts for various text types here or use some of these.

- On a recent European trip, you find your travel group booked into the stunning and mysterious Castle Frankenfurter for a single night… As night falls, the massive castle of over one hundred rooms seems to creak and groan as a series of unexplained events begin to make you wonder who or what else is spending the evening with you. Write a narrative that tells the story of your evening.

- You are a famous adventurer who has discovered new lands; keep a travel log over a period of time in which you encounter new and exciting adventures and challenges to overcome. Ensure your travel journal tells a story and has a definite introduction, conflict and resolution.

- You create an incredible piece of technology that has the capacity to change the world. As you sit back and marvel at your innovation and the endless possibilities ahead of you, it becomes apparent there are a few problems you didn’t really consider. You might not even be able to control them. Write a narrative in which you ride the highs and lows of your world-changing creation with a clear introduction, conflict and resolution.

- As the final door shuts on the Megamall, you realise you have done it… You and your best friend have managed to sneak into the largest shopping centre in town and have the entire place to yourselves until 7 am tomorrow. There is literally everything and anything a child would dream of entertaining themselves for the next 12 hours. What amazing adventures await you? What might go wrong? And how will you get out of there scot-free?

- A stranger walks into town… Whilst appearing similar to almost all those around you, you get a sense that this person is from another time, space or dimension… Are they friends or foes? What makes you sense something very strange is going on? Suddenly they stand up and walk toward you with purpose extending their hand… It’s almost as if they were reading your mind.

NARRATIVE WRITING VIDEO TUTORIAL

Teaching Resources

Use our resources and tools to improve your student’s writing skills through proven teaching strategies.

When teaching narrative writing, it is essential that you have a range of tools, strategies and resources at your disposal to ensure you get the most out of your writing time. You can find some examples below, which are free and paid premium resources you can use instantly without any preparation.

FREE Narrative Graphic Organizer

THE STORY TELLERS BUNDLE OF TEACHING RESOURCES

A MASSIVE COLLECTION of resources for narratives and story writing in the classroom covering all elements of crafting amazing stories. MONTHS WORTH OF WRITING LESSONS AND RESOURCES, including:

NARRATIVE WRITING CHECKLIST BUNDLE

OTHER GREAT ARTICLES ABOUT NARRATIVE WRITING

Narrative Writing for Kids: Essential Skills and Strategies

7 Great Narrative Lesson Plans Students and Teachers Love

Top 7 Narrative Writing Exercises for Students

How to Write a Scary Story

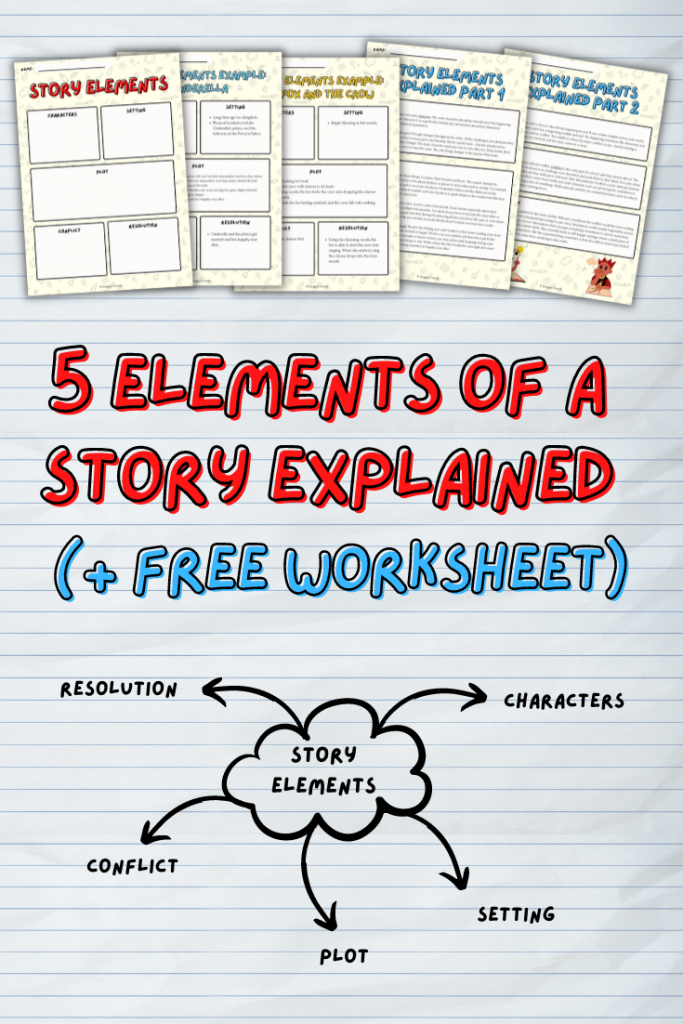

5 Elements Of a Story Explained With Examples (+ Free Worksheet)

What do all good stories have in common? And no it’s not aliens or big explosions! It’s the five elements of a story: Characters, Setting, Plot, Conflict and Resolution. Story elements are needed to create a well-structured story. It doesn’t matter if you’re writing a short story or a long novel, the core elements are always there.

What are Story Elements?

1. characters, 4. conflict, 5. resolution, the fox and the crow, free story elements worksheet (pdf), why are story elements needed, what are the 7 elements of a story, what are the 5 important story elements, what are the 12 elements of a short story, what are the 6 important elements of a story, what are the 9 story elements, what are the 8 elements of a story.

This short video lesson explains the main points relating to the five story elements:

Story elements are the building blocks needed to make a story work. Without these blocks, a story will break down, failing to meet the expectations of readers. Simply put, these elements remind writers what to include in stories, and what needs to be planned. By understanding each element, you increase the chances of writing a better story or novel.

Over the years, writers have adapted these elements to suit their writing process. In fact, there can be as few as 4 elements in literature all the way up to 12 elements. The most universally used story elements contain just five building blocks:

These five elements are a great place to start when you need help planning your story. You may also notice that these story elements are what most book outlining techniques are based on.

5 Elements Of A Story

Below we have explained each of the five elements of a story in detail, along with examples.

Characters are the most familiar element in stories. Every story has at least one main character. Stories can also have multiple secondary characters, such as supporting characters and villain/s. The main character should be introduced at the beginning. While introducing this character it is a good idea to include key information about this character’s personality, past and physical appearance. You should also provide a hint to what this character’s major conflict is in the story (more on conflict later).

The main character also goes through changes throughout the story. All the challenges and obstacles they face in the story allow them to learn, grow and develop. Depending on your plot, they might become a better person, or even a worse one – if this is a villain’s origin story. But be careful here – Growth should not be mistaken for a personality change! The main character must stay true to who they are. Deep inside their personality should stay more or less the same. The only thing that changes is the lessons they learn, and how these impact them.

Check out this post on 20 tips for character development for more guidance.

Settings in stories refer to three things: Location, Time Period and Mood. The easiest element to understand is location . Location is the physical place/s the story takes part in mostly. For example, the tale of Cinderella takes part in two main locations: Cinderella’s Palace and the Ballroom at the Prince’s Palace. It is a good idea to explain each new location in great detail, so the readers feel like they are also right there with the characters. The physical location is also something that can be included at the beginning of the story to set the story’s tone.

Next comes the time period . Every story is set in some time period. Some stories especially about time travel may be set across multiple time periods. You don’t always have to include the exact date or year in your story. But it is a good idea that during the planning phase, you know the year or even dates the story is set in. This can help you include accurate details about location and even key events. For example, you don’t want to be talking about characters using mobile phones in the 18th century – It just wouldn’t make sense (Unless of course, it’s a time travel story)!

The final part of the setting is the mood . The mood is the feeling you want readers to feel when reading your story. Do you want them to be scared, excited or happy? It’s the way you explain and describe a particular location, object or person. For example in horror stories, you may notice dark language being used throughout, such as gore, dismal, damp or vile. While a fairy tale such as Cinderella uses light and warm language like magical, glittering, beautiful or happily ever after. The choice of words sets the mood and adds an extra layer of excitement to a story.

The plot explains what a story is about from beginning to end. It can contain multiple scenes and events. In its simplest form, a plot has a beginning, middle and end. The beginning introduces the characters and sometimes shows a minor conflict. The middle is where the major conflict occurs. And the ending is where all conflicts are resolved, and the story comes to a close. The story mountain template is a great way to plan out a story’s plot.

A story is not a story without conflict. Conflict is also a key part of a story’s plot (see section above). The purpose of conflict in stories is to challenge your characters and push them to their limits. It is only when they face this conflict, do they really grow and reach their full potential. Conflicts can be internal, external or both. Internal conflicts come from inside your main character, such as not having the confidence in themself or having a fear of something. While external conflicts are created elsewhere, such as natural disasters or evil villains creating havoc.

The resolution is a solution to the main conflict. Without a resolution, the conflict would be neverending, and this could lead to a disappointing ending to your story. Resolutions could include huge battle scenes or even the discovery of new information which changes everything. Sometimes in stories resolutions don’t always solve the conflict 100%. This normally leads to cliffhanger endings, where a small piece of conflict still exists somewhere. But the important thing to remember is that all conflicts need some kind of resolution in stories to make them satisfying to the reader.

Story Elements Examples

We explained each story element above, and now it’s time to put our teachings into practice. Here are some common story element examples we created.

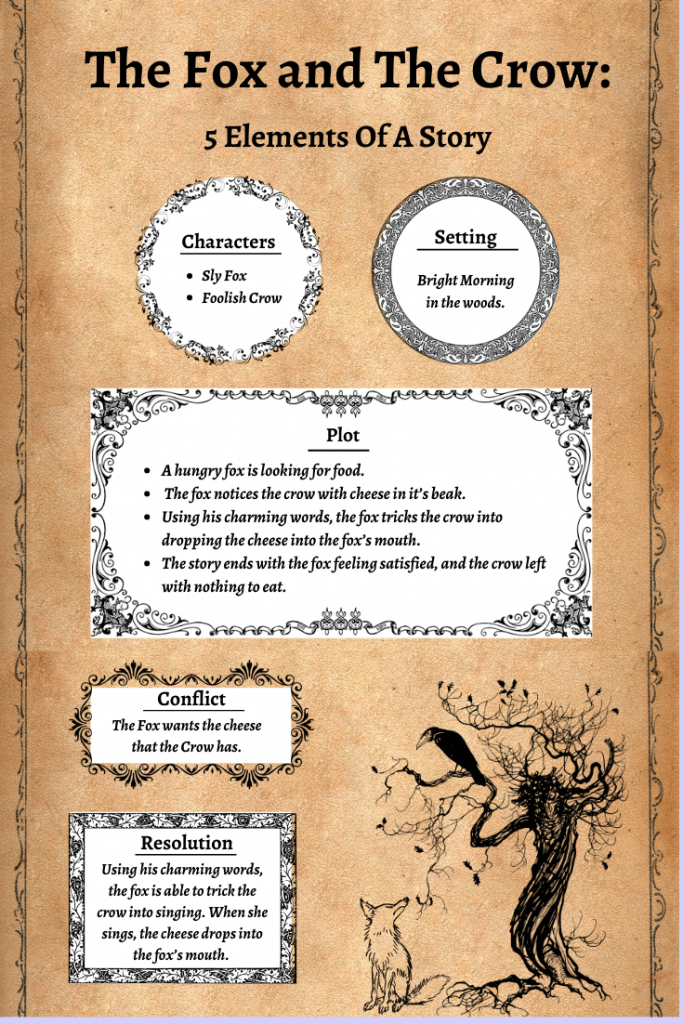

The fox and the crow is one of Aesop’s most famous fables . It tells the story of a sly fox who tricks a foolish crow into giving her breakfast away. You can read the full fable on the read.gov website .

Here are the elements of a story applied to the fable of the fox and the crow:

- Characters: A sly fox and a foolish crow.

- Setting: Bright Morning in the woods.

- Plot: A hungry fox is looking for food. The fox notices the crow with cheese in its beak. Using his charming words, the fox tricks the crow into dropping the cheese into the fox’s mouth. The story ends with the fox feeling satisfied, and the crow left with nothing to eat.

- Conflict: The Fox wants the cheese that the Crow has.

- Resolution: Using his charming words, the fox is able to trick the crow into singing. When she starts to sing, the cheese drops into the fox’s mouth.

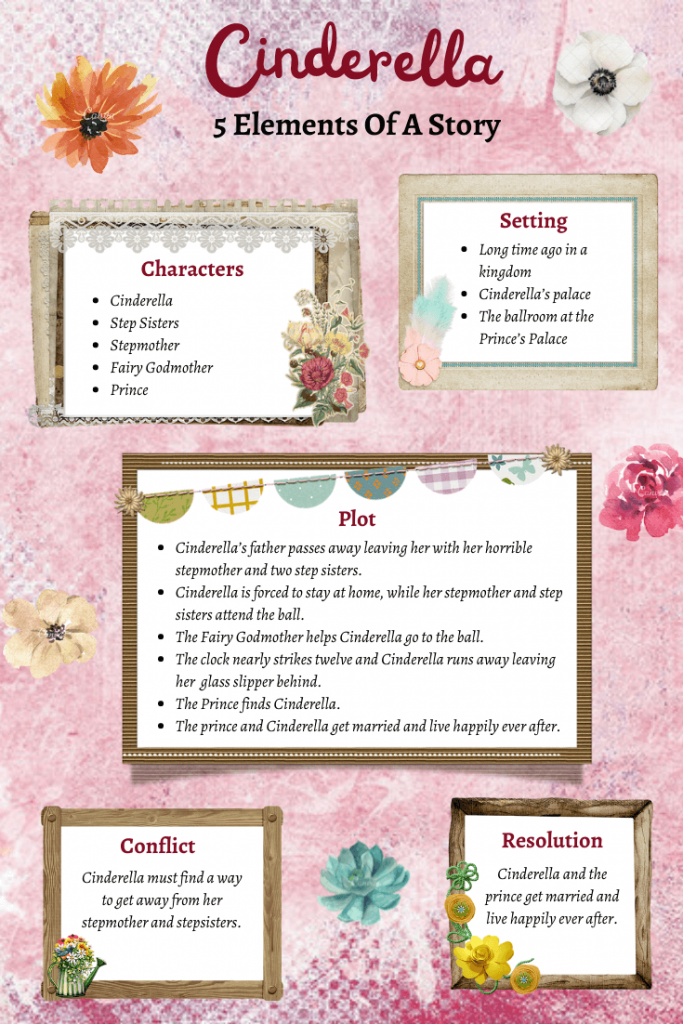

Cinderella is one of the most famous fairy tales of all time. It tells the tale of a poor servant girl who is abused by her stepmother and stepsisters. One night with the help of her fairy godmother, she attends the ball. It is at the ball that the prince falls in love with Cinderella. Eventually leading to a happy ending.

Here are the elements of a story applied to the short story of Cinderella:

- Characters: Cinderella, the stepsisters, the stepmother, the fairy godmother, and the prince.

- Setting: Long time ago in a kingdom. Physical locations include Cinderella’s Palace and the ballroom at the Prince’s Palace.

- Plot: Cinderella’s father passes away leaving her with her horrible stepmother and two stepsisters. They abuse her and make her clean the house all day. One day, an invite comes from the Prince’s palace inviting everyone to the ball. Cinderella is forced to stay at home, while her stepmother and sisters attend. Suddenly Cinderella’s fairy godmother appears and helps her get to the ball. But she must return home by midnight. At the ball, Cinderella and the Prince fall in love. The clock nearly strikes twelve and Cinderella runs away leaving a glass slipper behind. The prince then searches the kingdom to find Cinderella. Eventually, he finds her. The two get married and live happily ever after.

- Conflict: Cinderella must find a way to get away from her stepmother and stepsisters.

- Resolution: Cinderella and the prince get married.

Put everything you learned into practice with our free story elements worksheet PDF. This PDF includes a blank story elements anchor chart or graphic organiser, two completed examples and an explanation of each of the story elements. This worksheet pack is great for planning your own story:

Common Questions About Story Elements

Writing a story is a huge task. Simply just putting pen to paper isn’t really going to cut it, especially if you want to write professionally. Planning is needed. That’s where the story elements come in. Breaking a story down into different components, helps you plan out each area carefully. It also reminds you of the importance of each element and the impact they can have on the final story.

Some writers have expanded the traditional 5 elements to 7 elements of a story. These 7 elements include:

- Theme: What is the moral or main lesson to learn in your story?

- Characters: Who are your main and supporting characters?

- Setting: Where is your story set? Think about location and time period.

- Plot: What happens in your story?

- Conflict: What is the main conflict? Is this conflict internal or external?

- Point of View: Is this story written in first, second or third person view?

- Style: What kind of language or tone of voice will you use?

The 5 elements of a story include:

- Setting: Where is your story set? Think about location, time period and mood.

- Plot: What are the key events that happen in your story ?

- Resolution: How is the main conflict solved?

The longest version of the story elements includes 12 elements:

- Protagonist: Who is the main character or hero of the story?

- Antagonist : Who is the villain of the story?

- Setting : Where is your story set? Think about location and time period.

- Conflict : What is the main conflict? Is this conflict internal or external?

- Sacrifice : What will the main character lose if they fail?

- Rising Action : What action/s lead up to the main conflict?

- Falling Action: What happens after the conflict had ended?

- Message: What is the key message of your story?

- Language : What kind of words would you use? Think about the tone of voice and mood of the story.

- Theme: What is the overall moral or main lesson to learn in your story?

- Reality: How does your story relate to the real world?

Some versions of the story elements, completely remove the conflict element. In the 6 elements structure, conflict is included in the plot element:

- Plot: What happens in your story? Think about the main conflict.

We could consider the order of events, in this 9 story elements structure:

- Tension: What is the source of conflict?

- Climax: The moment when the main conflict happens.

- Plot: What happens in your story?

- Purpose: Why do certain events happen in your story?

- Chronology: What is the order of main events in your story?

The story elements can also be adapted to contain 8 elements:

- Style: What kind of language or words will you use?

- Tone: What is the overall mood of the story? Is it dark, funny or heartfelt?

Got any more questions about the key elements of a story? Share them in the comments below!

Marty the wizard is the master of Imagine Forest. When he's not reading a ton of books or writing some of his own tales, he loves to be surrounded by the magical creatures that live in Imagine Forest. While living in his tree house he has devoted his time to helping children around the world with their writing skills and creativity.

Related Posts

Comments loading...

Narrative Elements: 7 Key Aspects of Narrative Writing

Writing is hard. In a market where publishers and editors are critical of every story or poem, understanding the seven key elements of a narrative is more important than ever before. Regardless of your chosen genre of expertise, mastering these narrative elements will help to make you a more successful writer.

Narrative Elements

Did you just take a big sigh? The thought of crafting a worthy and unpredictable plot is daunting. An understanding of plot and the impact it has on your story is an essential part of crafting a compelling narrative.

The plot is thought of as the sequence of events in your narrative. The plot includes background information, conflict, the climax of the story, and lastly, the conclusion.

Many writers use the plot to map out their stories before beginning the full writing process. For fiction or non-fiction writing, this can work wonderfully as an novel outline . On a smaller scale, poets can use the concept of plot to plan the flow of their poems.

Setting

When you’re reading and feel like you’ve been transported to another universe – that’s setting . This element of the narrative is incredibly important. Setting establishes the time, place, and environment in which the main characters or narrator operates.

Crafting a high-quality setting is the difference between a believable story and one that falls flat. A story’s setting can also help you create rising action in your story!

A Tip from Our Editor

“I love using personification to create setting in a story. Giving human attributes to things in a scene, like the wind, or the walls in an old house, can really bring a piece of writing to life.” – R. R. Noall

Characters

Who are your characters? How do they behave and interact with the narrative as a whole? How are the protagonists and antagonists the same? How are they different?

Characters create your story. Characters are the reason your readers fall in love. Characters keep you up at night.

Invest time researching your character’s identities, behaviors, circumstances, and motivations. All of this will help you to create a world that readers (and you) are invested in whole-heartedly.

Dive head-first into our character development tips here.

Point of View

Who is telling your story and why? Establishing a point of view in your story or poem is essential. This allows readers to understand the motivations behind why the story is being told.

While it can be challenging to craft a consistent point of view, mastering the narrative will provide your work with the guiding voice reader’s crave.

The theme of a work should be clear. While this seems like a fundamental literary element, the theme helps to focus a narrative. Additionally, having a focused and clear theme will help you and publishers to market your book to the right audience.

What lessons are your characters going to learn? At the end of the story or poem, what is the main takeaway? This is your theme.

Symbolism

When studying literature, there is a lot of talk surrounding symbolism. While this may seem like an over-rated literary element, symbolism helps to layer meaning within a narrative.

Examples of symbolism include:

- The green light in The Great Gatsby.

- Harry’s scar in Harry Potter.

In narratives, symbols are what readers hold onto long after the story is over. Symbolism is what readers gravitate to.

Conflict

Conflict motivates characters, affects the plot, and ultimately dictates the theme of a narrative. What is the defining conflict in your story? What conflict inspired a poem?

Having a defined conflict allows your readers to better understand your work, sympathize with your characters or narrator, and ultimately appreciate the complexity of the plot you’ve created.

Practice Makes Perfect When Crafting Narrative Stories

Every writer struggles with these narrative elements. Through reading, exchange with other writers, and practice, you can conquer the 7 key elements of a narrative. Now that you’re inspired , get writing!

We also recommend exploring the Somebody Wanted So But Then framework. This can help you outline a story at a high level and covers many of the story elements discussed above.

Which element do you feel you need to improve upon? Tell us and explain why in the comments!

Have a story you’re ready to share with the world? Check out our submissions page.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Community , Education

Storytelling 101: the 6 elements of every complete narrative.

Everyone enjoys a good story. Telling a good story, however, isn’t as easy at it seems. It takes dedication to the craft, a willingness to learn and understand the different elements and techniques, and a heck of a lot of practice. Regardless of genre or style, however, all good stories have six common elements. When developing your next narrative work, make sure you’re paying careful attention to all of these.

The setting is the time and location in which your story takes place. Settings can be very specific, but can also be more broad and descriptive. A good, well-established setting creates an intended mood and provides the backdrop and environment for your story.

Example 1: July 21st, 1865 – Springfield, Missouri – Town Square – 6pm.

Wood Cabin Night Sky Time Lapse by davidjaffe

2. Characters

A story usually includes a number of characters, each with a different role or purpose. Regardless of how many characters a story has, however, there is almost always a protagonist and antagonist.

Central Characters: These characters are vital to the development of the story. The plot revolves around them.

Protagonist: The protagonist is the main character of a story. He or she has a clear goal to accomplish or a conflict to overcome. Although protagonists don’t always need to be admirable, they must command an emotional involvement from the audience.

Antagonist: Antagonists oppose protagonists, standing between them and their ultimate goals. The antagonist can be presented in the form of any person, place, thing, or situation that represents a tremendous obstacle to the protagonist. https://d3macfshcnzosd.cloudfront.net/056264467_main_xxl.mp4

Demonic Woman by rightcameraman

The plot is the sequence of events that connect the audience to the protagonist and their ultimate goal.

Example: A group of climbers plan to escort paying clients to the summit of Mt. Everest.

There is always a clear goal. In this case, it’s to get the paying clients safely up the mountain and return them to basecamp unharmed.

4. Conflict

The conflict is what drives the story. It’s what creates tension and builds suspense, which are the elements that make a story interesting. If there’s no conflict, not only will the audience not care, but there also won’t be any compelling story to tell.

Example 1: “We climbed Mt. Everest without issue.”

Without some sort of conflict, there’s no story. It’s just a statement. As an audience member, I think, “Oh, cool. Sounds like fun. Did you take any photos?”

Example 2: “We attempted to climb Mt. Everest and were suddenly hit with an unexpected storm, causing our team to become dispersed with zero visibility and a lack of oxygen, ultimately leading to the death of 13 people.”

Now there’s a story. As an audience member, I want to know, “What happened? How did 13 people die?”

Conflict is what engages an audience. It’s what keeps them white-knuckled, at the edge of their seats, waiting impatiently to see if the protagonists will overcome their obstacle. https://d3macfshcnzosd.cloudfront.net/022226895_main_xxl.mp4

Avalanche at Basecamp by RickRay

The theme is what the story is really about. It’s the main idea or underlying meaning. Often, it’s the storyteller’s personal opinion on the subject matter. A story may have both a major theme and minor themes.

Major Theme: An idea that is intertwined and repeated throughout the whole narrative.

Minor Theme: An idea that appears more subtly, and doesn’t necessarily repeat.

6. Narrative Arc

A strong story plot has a narrative arc that has four required elements of its own.

Setup: The world in which the protagonist exists prior to the journey. The setup usually ends with the conflict being revealed.

Rising Tension: The series of obstacles the protagonist must overcome. Each obstacle is usually more difficult and with higher stakes than the previous one.

Climax: The point of highest tension, and the major decisive turning point for the protagonist.

Resolution: The conflict’s conclusion. This is where the protagonist finally overcomes the conflict, learns to accept it, or is ultimately defeated by it. Regardless, this is where the journey ends. https://d3macfshcnzosd.cloudfront.net/059694348_main_xxl.mp4

Friends Watching a Film by hotelfoxtrot While every story is different, a successful one captivates its audience and inspires an emotional response. As humans, we love to be entertained, and storytelling is universally accessible. Learning to craft a compelling story by engaging an active audience is the art of storytelling.

Top Image: Man on the Run by konradbak

Narrative Definition

What is narrative? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

A narrative is an account of connected events. Two writers describing the same set of events might craft very different narratives, depending on how they use different narrative elements, such as tone or point of view . For example, an account of the American Civil War written from the perspective of a white slaveowner would make for a very different narrative than if it were written from the perspective of a historian, or a former slave.

Some additional key details about narrative:

- The words "narrative" and "story" are often used interchangeably, and with the casual meanings of the two terms that's fine. However, technically speaking, the two terms have related but different meanings.

- The word "narrative" is also frequently used as an adjective to describe something that tells a story, such as narrative poetry.

How to Pronounce Narrative

Here's how to pronounce narrative: nar -uh-tiv

Narrative vs. Story vs. Plot

In everyday speech, people often use the terms "narrative," "story," and "plot" interchangeably. However, when speaking more technically about literature these terms are not in fact identical.

- A story refers to a sequence of events. It can be thought of as the raw material out of which a narrative is crafted.

- A plot refers to the sequence of events, but with their causes and effects included. As the writer E.M. Forster put it, while "The King died and the Queen died" is a story (i.e., a sequence of events), "The King died, and then the Queen died of grief" is a plot.

- A narrative , by contrast, has a more broad-reaching definition: it includes not just the sequence of events and their cause and effect relationships, but also all of the decisions and techniques that impact how a story is told. A narrative is how a given sequence of events is recounted.

In order to fully understand narrative, it's important to keep in mind that most sequences of events can be recounted in many different ways. Each different account is a separate narrative. When deciding how to relay a set of facts or describe a sequence of events, a writer must ask themselves, among other things:

- Which events are most important?

- Where should I begin and end my narrative?

- Should I tell the events of the narrative in the order they occurred, or should I use flashbacks or other techniques to present the events in another order?

- Should I hold certain pieces of information back from the reader?

- What point of view should I use to tell the narrative?

The answers to these questions determine how the narrative is constructed, so they have a huge influence on the way a reader sees or understands what they're reading about. The same series of events might be read as happy or sad, boring or exciting—all depending on how the narrative is constructed. Analyzing a narrative just means examining how it is constructed and why it is constructed that way.

Narrative Elements

Narrative elements are the tools writers use to craft narratives. A great way to approach analyzing a narrative is to break it down into its different narrative elements, and then examine how the writer employs each one. The following is a summary of the main elements that a writer might use to build his or her narrative.

- For example, a story about a crime told from the perspective of the victim might be very different when told from the perspective of the criminal.

- For instance, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway were friends, and they wrote during the same era, but their writing is very different from one another because they have markedly different voices.

- For example, Jonathan Swift's essay " A Modest Proposal " satirizes the British government's callous indifference toward the famine in Ireland by sarcastically suggesting that cannibalism could solve the problem—but the essay would have a completely different meaning if it didn't have a sarcastic tone.

- For example, the first half of Charles Dickens' novel David Copperfield tells the story of the narrator David Copperfield's early childhood over the course of many chapters; about halfway through the novel, David quickly glosses over some embarrassing episodes from his teenage years (unfortunate fashion choices and foolish crushes); the second half of the novel tells the story of his adult life. The pacing give readers the sense that David's teen years weren't really that important. Instead, his childhood traumas, the challenges he faced as a young man, and the relationships he formed during both childhood and adulthood make up the most important elements of the novel.

- For example, Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein uses three different "frames" to tell the story of Dr. Frankenstein and the creature he creates: the novel takes the form of letters written by Walton, an arctic explorer; Walton is recounting a story that Dr. Frankenstein told him; and as part of his story, Dr. Frankenstein recounts a story told to him by the creature.

- Linear vs. Nonlinear Narration: You may also hear the word narrative used to describe the order in which a sequence of events is recounted. In a linear narrative, the events of a story are described chronologically , in the order that they occurred. In a nonlinear narrative, events are described out of order, using flashbacks or flash-forwards, and then returning to the present. In some nonlinear narratives, like Ken Kesey's Sometimes a Great Notion , there is a clear sense of when the "present" is: the novel begins and ends with the character Viv sitting in a bar, looking at a photograph. The rest of the novel recounts (out of order) events that have happened in the distant and recent past. In other nonlinear narratives, it may be difficult to tell when the "present" is. For example, in Kurt Vonnegut's novel Slaughterhouse-Five , the character Billy Pilgrim, seems to move forward and backward in time as a result of post-traumatic stress. Billy is not always certain if he is experiencing memories, flashbacks, hallucinations, or actual time travel, and there are inconsistencies in the dates he gives throughout the book—all of which of course has a huge impact on how his stories are relayed to the reader.

Narrative as an Adjective

It's worth noting that the word "narrative" is also frequently used as an adjective to describe something that tells a story.

- Narrative Poetry: While some poetry describes an image, experience, or emotion without necessarily telling a story, narrative poetry is poetry that does tell a story. Narrative poems include epic poems like The Iliad , The Epic of Gilgamesh , and Beowulf . Other, shorter examples of narrative poetry include "Jabberwocky" by Lewis Carrol, "The Lady of Shalott" by Alfred Lord Tennyson, "The Goblin Market" by Christina Rossetti, and "The Glass Essay," by Anne Carson.

- Narrative Art: Similarly, the term "narrative art" refers to visual art that tells a story, either by capturing one scene in a longer story, or by presenting a series of images that tell a longer story when put together. Often, but not always, narrative art tells stories that are likely to be familiar to the viewer, such as stories from history, mythology, or religious teachings. Examples of narrative art include Michelangelo's painting on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and the Pietà ; Paul Revere's engraving entitled The Bloody Massacre ; and Artemisia Gentileschi's painting Judith Slaying Holofernes .

Narrative Examples

Narrative in the book thief by markus zusak.

Zusak's novel, The Book Thief , is narrated by the figure of Death, who tells the story of Liesel, a girl growing up in Nazi Germany who loves books and befriends a Jewish man her family is hiding in their home. In the novel's prologue, Death says of Liesel:

Yes, often, I am reminded of her, and in one of my vast array of pockets, I have kept her story to retell. It is one of the small legion I carry, each one extraordinary in its own right. Each one an attempt—an immense leap of an attempt—to prove to me that you, and your human existence, are worth it.

Narrators do not always announce themselves, but Death introduces himself and explains that he sees himself as a storyteller and a repository of the stories of human lives. Choosing Death (rather than Leisel) as the novel's narrator allows Zusak to use Liesel's story to reflect on the power of stories and storytelling more generally.

Narrative in A Visit From the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan

In A Visit From the Good Squad , Egan structures the narrative of her novel in an unconventional way: each chapter stands as a self-contained story, but as a whole, the individual episodes are interconnected in such a way that all the stories form a single cohesive narrative. For example, in Chapter 2, "The Gold Cure," we meet the character Bennie, a middle-aged music producer, and his assistant Sasha:

"It's incredible," Sasha said, "how there's just nothing there." Astounded, Bennie turned to her…Sasha was looking downtown, and he followed her eyes to the empty space where the Twin Towers had been.

Because there is an empty space where the Twin Towers had been, the reader knows that this dialogue is taking place some time after the September 11th, 2001 attack in which the World Trade Center was destroyed. Bennie appears again later in the novel, in Chapter 6, "X's and O's," which is set ten years prior to "The Gold Cure." "X's and O's" is narrated by Bennie's old friend, Scotty, who goes to visit Bennie at his office in Manhattan:

I looked down at the city. Its extravagance felt wasteful, like gushing oil or some other precious thing Bennie was hoarding for himself, using it up so no one else could get any. I thought: If I had a view like this to look down on every day, I would have the energy and inspiration to conquer the world. The trouble is, when you most need such a view, no one gives it to you.

Just as Sasha did in Chapter 2, Scotty stands with Bennie and looks out over Manhattan, and in both passages, there is a sense that Bennie fails to notice, appreciate, or find meaning in the view. But the reader wouldn't have the same experience if the story had been told in chronological order.

Narrative in Atonement by Ian McEwan

Ian McEwan's novel Atonement tells the story of Briony, a writer who, as a girl, sees something she doesn't understand and, based on this faulty understanding, makes a choice that ruins the lives of Celia, her sister, and Robbie, the man her sister loves. The first part of the novel appears to be told from the perspective of a third-person omniscient narrator; but once we reach the end of the book, we realize that we've read Briony's novel, which she has written as an act of atonement for her terrible mistake. Near the end of Atonement , Briony tells us:

I like to think that it isn’t weakness or evasion, but a final act of kindness, a stand against oblivion and despair, to let my lovers live and to unite them at the end. I gave them happiness, but I was not so self-serving as to let them forgive me. Not quite, not yet. If I had the power to conjure them at my birthday celebration…Robbie and Cecilia, still alive, sitting side by side in the library…

In Briony's novel, Celia and Robbie are eventually able to live together, and Briony visits them in an attempt to apologize; but in real life, we learn, Celia and Robbie died during World War II before they could see one another again, and before Briony could reconcile with them. By inviting the reader to imagine a happy ending, Briony effectively heightens the tragedy of the events that actually occurred. By choosing Briony as his narrator, and by framing the novel Briony wrote with her discussion of her own novel, McEwan is able to create multiple interlacing narratives, telling and retelling what happened and what might have been.

Narrative in Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Slaughterhouse-Five tells the story of Billy Pilgrim, a World War II veteran who survived the bombing of Dresden, and has since “come unstuck in time.” The novel uses flashbacks and flash-forwards, and is narrated by an unreliable narrator who implies to the reader that the narrative he is telling may not be entirely true:

All this happened, more or less. The war parts, anyway, are pretty much true. One guy I knew really was shot in Dresden for taking a teapot that wasn’t his. Another guy I knew really did threaten to have his personal enemies killed by hired gunmen after the war. And so on. I’ve changed all the names.

The narrator’s equivocation in this passage suggests that even though the story he is telling may not be entirely factually accurate, he has attempted to create a narrative that captures important truths about the war and the bombing of Dresden. Or, maybe he just doesn’t remember all of the details of the events he is describing. In any case, the inconsistencies in dates and details in Slaughterhouse-Five give the reader the impression that crafting a single cohesive narrative out of the horrific experience of war may be too difficult a task—which in turn says something about the toll war takes on those who live through it.

What's the Function of Narrative in Literature?

When we use the word "narrative," we're pointing out that who tells a story and how that person tells the story influence how the reader understands the story's meaning. The question of what purpose narratives serve in literature is inseparable from the question of why people tell stories in general, and why writers use different narrative elements to shape their stories into compelling narratives. Narratives make it possible for writers to capture some of the nuances and complexities of human experience in the retelling of a sequence of events.

In literature and in life, narratives are everywhere, which is part of why they can be very challenging to discuss and analyze. Narrative reminds us that stories do not only exist; they are also made by someone, often for very specific reasons. And when you analyze narrative in literature, you take the time to ask yourself why a work of literature has been constructed in a certain way.

Other Helpful Narrative Resources

- Etymology: Merriam-Webster describes the origins and history of usage of the term "narrative."

- Narrative Theory: Ohio State University's "Project Narrative" offers an overview of narrative theory.

- History and Narrative: Read more about the similarities between historical and literary narratives in Hayden White's Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in 19th-Century Europe.

- Narrative Art: This article from Widewalls explores narrative art and discusses what kind of art doesn't tell stories.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1900 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 39,983 quotes across 1900 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- Point of View

- Onomatopoeia

- External Conflict

- Dramatic Irony

- Polysyndeton

- Rising Action

- Verbal Irony

- Blank Verse

- Formal Verse

Looking to publish? Meet your dream editor, designer and marketer on Reedsy.

Find the perfect editor for your next book

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Blog • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Jan 02, 2024

Narrative Structure: Definition, Examples, and Writing Tips

As you plot out your novel, story structure will likely be at the top of your mind. But there’s something else you’ll need to consider in addition to that: narrative structure. While story structure is the overall flow of the story, from the exposition to the rising and falling action, narrative structure is the framing that supports it. Let’s take a deeper dive into what that means.

What is narrative structure?

A narrative structure is the order in which a story’s events are presented. It is the framework from which a writer can hang individual scenes and plot points with the aim of maximizing tension, interest, excitement, or mystery.

Traditionally, most stories start at the chronological beginning ("once upon a time") and finish at the end ("and they lived happily ever after"). However, a story can technically be told in any order. Writers can arrange their plot points in a way that creates suspense — by omitting certain details or revealing information out of order, for example.

Sometimes, storytellers will begin in the middle and literally 'cut to the chase' before revealing the backstory later on. In short, narrative structure is a powerful tool that writers can wield to great effect if handled with care and consideration.

FREE COURSE

How to Plot a Novel in Three Acts

In 10 days, learn how to plot a novel that keeps readers hooked

Types of narrative structure

There’s a whole branch of literary criticism dedicated to studying narrative structure: narratology. We won’t quite go into academic depth, but it’s important to know the main types of structure available for your narrative so you can best choose the one that serves your story’s purpose. Here are four of the most common types of narrative structure used in books and movies.

Linear narrative structure is exactly what it sounds like — when a story is told chronologically from beginning to end. Events follow each other logically and you can easily link the causality of one event to another. At no point does the narrative hop into the past or the future. The story is focused purely on what is happening now. It’s one of the most common types of narrative structures seen in most books, movies, or TV shows.

Example: Pride and Prejudice

A great example of a linear narrative is Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice . We follow Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy's love story from their first disastrous meeting to when they fall in love and admit their feelings for each other. All of the events are presented in the order that they occur, and we can easily see how one misunderstanding led to another right until the very end.

2. Nonlinear

On the flip side, a nonlinear narrative is when a story is told out of order — where scenes from the beginning, middle, and end are mixed up, or in some cases, the chronology may be unclear. With this freedom to jump around in time, new information or perspectives can be introduced at the point in the story where they can have maximum impact. A common feature of this type of narrative is the use of extended flashbacks.

These types of stories tend to be character-centric. Hopping through time allows the author to focus on the emotional states of the characters as they process different events and contrast them against their previous or future selves .

How to Develop Characters

In 10 days, learn to develop complex characters readers will love.