Ambiguously Democratic: Parties, Coalitions, and Candidates in the 2022 Philippine Elections

Elections in the Philippines is a time of alliances, pundits, politicking within and across party lines. A range of candidates have put themselves forward for the upcoming 2022 elections, though their agendas and positions may still be too cloudy for voters to make a clear bet. Persistent problems around politics are present, although reform via the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) is slowly taking place. There’s still plenty of time ahead for unpredictability, by prospective candidates and the voting population.

Editor's Note:

This article was published on 28 October 2021 and on 13 November 2021, several developments lead to the reshuffling of candidacy. Senator Christopher "Bong" Go, a Duterte loyalist, registered on Saturday to run for president after withdrawing from the vice-presidential race, pitting himself against rivals including Mr Ferdinand "Bongbong" Marcos Jr, son of the late dictator. Ms.Sara Duterte-Carpio announced that she will register as a vice-presidential candidate. The current president Rodrigo Duterte had also announced that he would run for vice-president and one day later he changed his mind to run as senator instead.

What political parties?

On 17 July 2021, during the ruling party’s national assembly, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte reminded his party colleagues to “never lose sight of the founding principles upon which this party was built on. Let us never forget that our end goal is to improve the welfare of the Filipino people.” True to form, the president spoke in his usual folksy manner, rallying his party mates for the 2022 elections. At one point he promised , “I will campaign for you. And I will bring lots of money. In sacks if there are.”

The money politics that has characterized elections in the country, one of Asia’s oldest democracies, is a campaign finance issue that is recognized but never arrested and controlled

Elections in the Philippines involves money and political machines. The money politics that has characterized elections in the country, one of Asia’s oldest democracies, is a campaign finance issue that is recognized but never arrested and controlled. This is just one part of the problem. The bigger part of the problem is the low institutionalization of political parties in the Philippines. The lack of genuine programmatic political parties persists even as the language of party politics is constantly used. Notably absent in this national meeting of the PDP–Laban were some key party officials including its vice-chair Senator Aquilino Pimentel III, son of the party founder, and boxer-turned-Senator Manny Pacquiao, the party’s president. The split and creation of new factions within the party is just one more manifestation of the reorientation of Philippine politics before the 2022 national and local elections. And the undermining of a democratic institution under the ruling populist administration.

Meanwhile, a stalwart member of the Liberal Party, purportedly the opposition party, recently announced that he will support the candidacy of Sara Duterte, the president’s daughter, should she decide to run for president. According to Cavite First District Rep. Francis Gerald Aguinaldo Abaya , “I do not know the President, nor do I know the Mayor from Davao City, and I am from the opposition… Still the assistance keeps on coming. There is just no way I can ignore the kindness and support of the President and his daughter.” The congressman was quick to point out that it was a personal decision and not a Liberal Party decision to support the administration’s candidate. According to Abaya, “We all have our own minds in the Liberal Party.”

While party switching is not new in the Philippines, the increasing ‘anarchy of political parties’ is.

When Liberal Party Chairman Leni Robredo filed her candidacy for the presidency, many cheered and as many were wondering why she filed as an independent candidate. In the last five years, multiple members of the Liberal Party have either allied with the administration or have switched to the ruling party. While party switching is not new in the Philippines, the increasing ‘ anarchy of political parties ’ is. The lack of coordinated party behavior, party discipline, and party finance transparency are persistent problems and typical in Philippine politics. Party candidate selection revolves around dynastic families and political clans. Alliances and coalitions crystalize as election day approaches and clientelistic promissory notes are written. The language of party politics is used, and expectations of party politics ensues even as there are no genuine programmatic political parties.

Candidates and a convenor’s group

An initial attempt to unify the opposition against the ruling party frayed and failed. A convenor’s group, 1Sambayan, was formed made up of former high-ranking government officials, including a former Ombudsman and an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. In the political history of the Philippines, a convenor’s group in 1985 launched the candidacy of Corazon Aquino that eventually toppled the Marcos dictatorship. The difference then and now is that the current strongman rule of Rodrigo Duterte continues to remain popular. There is satisfaction and support for the violent war on drugs even as Duterte’s ratings on pandemic performance has slightly declined. The popularity among voters of candidates with authoritarian tendencies past and present is evident and in some cases, factored in by candidates as part of their election calculus. Presidential candidate Panfilo Lacson’s digital campaign includes pictures of him as a uniformed and bemedaled general – an image that he distanced himself from when he initially ran for the Senate.

Thanks to the rehabilitated image of the Marcos name through historical revisionism that celebrates the years of dictatorship as years of development, voter preference for the son of the former dictator remains high.

Bongbong Marcos, a strong ally of the Duterte family and promising to continue the war on drugs, has filed his candidacy for president riding on a strong base of support that includes youth voters. Thanks to the rehabilitated image of the Marcos name through historical revisionism that celebrates the years of dictatorship as years of development, voter preference for the son of the former dictator remains high. Sara Duterte also ranks high in voter preference surveys , and there is expectation that she will continue the brand of leadership of her father should she decide to run for president. Manny Pacquiao, also running for president, once said in an interview, “ Too much democracy is bad for the Philippines.” Manila mayor and now presidential candidate Isko Moreno likes to talk tough and has been likened to the populist brand of Duterte . These public sentiments towards authoritarianism contribute to the ambiguous democracy of the Philippines.

Out of the violent populist woods?

In the last five years, executive powers went unchecked. Institutions that can extract accountability, such as the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), Office of the Ombudsman, and mass media, have been threatened and weakened. What should have been independent branches of government was neutralized by the Duterte administration by targeting top female officials in each: the Supreme Court lost female Chief Justice Lourdes Sereno through a quo warranto; Senator Leila de Lima was left to perform her duties as a legislator while incarcerated without formal charges; and the office of Vice-President Leni Robredo was disabled with limited resources, a budget constantly reduced, almost ridiculed. [1]

In the coming months, all eyes will be on another democratic institution, the Commission on Elections (COMELEC). This constitutional commission tasked with election administration has a history that at times favored the incumbent. Over the years, the commission has tried to modernize and increase its capacity, but there are lingering issues of credibility. Even as COMELEC has addressed issues of reform, much can still be done. Hobbled by resource and capacity issues, part of the trepidation if the COMELEC will perform its mandate with independence is the composition of the commissioners. By 2022, all are appointees of Duterte and with ties to Mindanao. To the credit of COMELEC, so far there are no indications that it will be partisan, nor its autonomy breached. But COMELEC can also be more proactive in shaping electoral politics – it can issue official statements to show that it is the authority on all electoral matters. The sudden revival of small, inactive political parties during election season to serve as vehicles by politicians who were eased out of intra-party competition and the substitution of candidates at the last minute has become a common strategy. It makes the electoral arena seem bereft of a referee to keep the integrity of the game. This can leave some voters and candidates having less confidence that it will be a fair election.

The sudden revival of small, inactive political parties during election season to serve as vehicles by politicians who were eased out of intra-party competition and the substitution of candidates at the last minute has become a common strategy.

There are some pockets of democratic resilience and some authoritarian reversals that can give hope to both candidates and voters in the 2022 elections. Impeachment proceedings in the House against Associate Justice of the Supreme Court Marvic Leonen by Duterte allies did not flourish. The Commission on Audit raised red flags on irregular procurement deals that implicate officials in the Department of Budget and Management (DBM) and Department of Health (DOH) with close ties to the president. Two libel cases against journalist Maria Ressa [2] have been dropped. And a survey from Social Weather Stations (SWS) on the public’s support for the term limit of the president has been consistent for more than a decade – a strong signal from the public that should thwart any thoughts of clinging to power, even for a popular president. Will the Philippines be out of the violent populist woods by 2022?

The constellation of candidates and coalitions, including the seemingly unwilling Sara Duterte, can still realign until 15 November 2021, the last day substitution of candidates allowed by COMELEC. It is an election sleight of hand Duterte used in 2016 when he played reluctant candidate. This proved to be a good delaying strategy that left his opponents with less time for strategic maneuvering. For 2022, Duterte and allies seem to have the same strategy: at the final hour of filing the certificate of candidacy, Senator Bato dela Rosa, former Philippine National Police Chief and enforcer of the war on drugs, arrived to announce that he will be filing as the official presidential candidate of the ruling party. When asked multiple times what made him suddenly run for president, he was quick to answer that it was the party that asked him. When asked if he will eventually give way for the president’s daughter if she decides to run for president, the senator replied, “ Wouldn’t that be better? ” This delayed-candidacy strategy exploits the electoral system and undermines another democratic institution under this populist rule.

When Leni Robredo finally announced her candidacy on 7 October, the hesitancy was more realpolitik than politicking. Her survey numbers were less than impressive, and she knows incumbency advantage is a formidable opponent. Her local politics experience has taught her that. It is likely that Robredo has always seen herself more of a unifier than a candidate for the 2022 elections. Her choice to run as an independent, according to her, is to signal inclusivity . Leni Robredo joining the race nonetheless generated a lot of positive reaction in social media. Buildings turned on pink lights to show support and social media was abuzz. Whether that will cascade to votes, generate support from key political clans, or create a coalition is another issue. She and her campaign team need to keep the positive messaging of inclusivity throughout her campaign to attract coalition-building from a larger base of support.

The nature of elections with the constant live interviews, the closely covered campaigns, will also expose those who have gained traction mostly through social media with their carefully curated and staged performances.

It is still a long way to May 2022. Candidates running against Duterte’s anointed successor will need to strategize and coordinate to get the votes. It is important not to lose sight of the elusive ‘united opposition’. To ensure a non-administration win, each camp will have to run their campaign in a way that can leave an opening for alliances. Power-money-clan coordinates will crystalize closer to election day. But there is also a percentage of market votes that are undecided. The nature of elections with the constant live interviews, the closely covered campaigns, will also expose those who have gained traction mostly through social media with their carefully curated and staged performances. Voters who have not made up their minds will be keenly watching how each will run their campaign and the issues that they will champion. Campaigns can still pick up momentum, while there’s time for some to implode. The 2022 election is a critical juncture for the Philippines.

Dr. Cleo Calimbahin is an Associate Professor at Department of Political Science, De La Salle University, Philippines. Her research interests include Comparative Politics, Democracy, Elections, Election Administration, Corruption and Bureaucratic Capacity.

The views expressed by the author are not necessarily those of Heinrich Böll Stiftung.

[1] The same tactic was used by the administration in 2018 when the Commission on Human Rights was threatened with a PHP 1,000 (USD 20) budget. See https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/930106/house-budget-deliberations-chr-p1000-budget-speaker-alvarez

[2] Maria Ressa received the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize for her work in journalism and speaking truth to power

References:

Ranada, P. (2021, July 17). Duterte vows to bring “sacks of money” when he campaigns for PDP-Laban bets. Rappler . https://www.rappler.com/nation/elections/duterte-vows-bring-sacks-of-money-pdp-laban-candidates

Hicken, A., & Kuhonta, E. (Eds.). (2014). Party System Institutionalization in Asia: Democracies, Autocracies, and the Shadows of the Past . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107300385

Domingo, K. (2021, September 19). Pimentel says “real” PDP-Laban will “fight back” vs party “hijackers” in 2022 elections. ABS-CBN News . https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/09/19/21/real-pdp-laban-to-fight-back-vs-party-hijackers-koko

Escosio, J. (2021, September 26). Cavite Liberal Party rep throws support behind Mayor Sara. Philippine Daily Inquirer . https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1493051/cavite-liberal-party-rep-throws-support-behind-mayor-sara

Kasuya, Y., & Teehankee, J. C. (2020). Duterte Presidency and the 2019 Midterm Election: An Anarchy of Parties? , Philippine Political Science Journal, 41(1-2), 106-126. doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/2165025X-BJA10007

Danguilan-Vitug, M. (1985, November 13). Philippine opposition juggles big pre-election problems. Scrambles to unite behind a candidate, wants later vote. The Christian Science Monitor . https://www.csmonitor.com/1985/1113/oferd.html

Ranada, P. (2021, June 30). Duterte may cap term as most popular Philippine president. So what? Rappler . https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/so-what-if-duterte-may-cap-term-as-philippines-most-popular-president

September 2021 Nationwide Survey on the May 2022 Elections. (2021, September 29). Pulse Asia Research Inc. https://www.pulseasia.ph/september-2021-nationwide-survey-on-the-may-2022-elections

Elemia, C. (2019, March 2). Manny Pacquiao: “Too much democracy is bad for the Philippines.” Rappler . https://www.rappler.com/nation/manny-pacquiao-too-much-democracy-is-bad-for-the-philippines

Calimbahin, C. (2021). The City of Manila under COVID-19: Projecting Mayoral Performance amid Crisis. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 43(1), 70–76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27035526

Ranada, P. (2021, September 28). Duterte Lite: Is fence-sitting a sin or strategy in 2022 elections? Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/presidential-bets-fence-sitting-sin-strategy-2022-polls

Lalu, G. P. (2021, October 8). What if Sara Duterte substitutes for dela Rosa? ‘Mas maganda,’ Bato says. Philippine Daily Inquirer . https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1499249/what-if-sara-duterte-substitutes-for-dela-rosa-mas-maganda-bato-says

Ramos, C. M. (2021, October 8). Robredo says running as independent is ‘symbolic way’ of showing inclusivity. Philippine Daily Inquirer . https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1499055/robredo-says-running-as-independent-is-symbolic-way-of-showing-inclusivity

- Philippines

Duterte Says Yes to Mining in the Philippines. But at What Cost?

Landing Duterte’s Jet Ski Presidency

The 2019 Philippine Elections: Consolidating Power in an Eroding Democracy

© Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung e.V. Schumannstraße 8 10117 Berlin T +49 (30) 285 34-0 F +49 (30) 285 34-109 www.boell.de [email protected]

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Clan politics reign but a family is divided in the race to rule the Philippines

Julie McCarthy

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and his daughter Sara Duterte arrive for the opening of the Boao Forum for Asia Annual Conference 2018. AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and his daughter Sara Duterte arrive for the opening of the Boao Forum for Asia Annual Conference 2018.

A foiled succession plan, sensational allegations, and a family feud at the pinnacle of power — these are the ingredients in what promises to be a riveting race to succeed outgoing Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte.

The no-holds-barred contest scheduled for May 2022 has already produced what some observers see as an unsettling alliance: the offspring of two presidents pairing off in an unprecedented bid to run the country.

Taking full advantage of their prominence, Ferdinand Marcos Jr., son of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr., has teamed up with Sara Duterte, daughter of President Rodrigo Duterte in the national election.

He is running for president in this dynastic duo, while she vies for vice president.

Are dynasties and celebrities narrowing democracy?

Political dynasties in the Philippines are nothing new.

Richard Heydarian, an expert on Philippine politics, says they are such a dominant feature in the country that between 70% and 90% of elected offices have been controlled by influential families.

But even by those standards, this Marcos-Duterte coupling takes powerful clan politics to a new level, says University of the Philippines Diliman political science professor Aries Arugay.

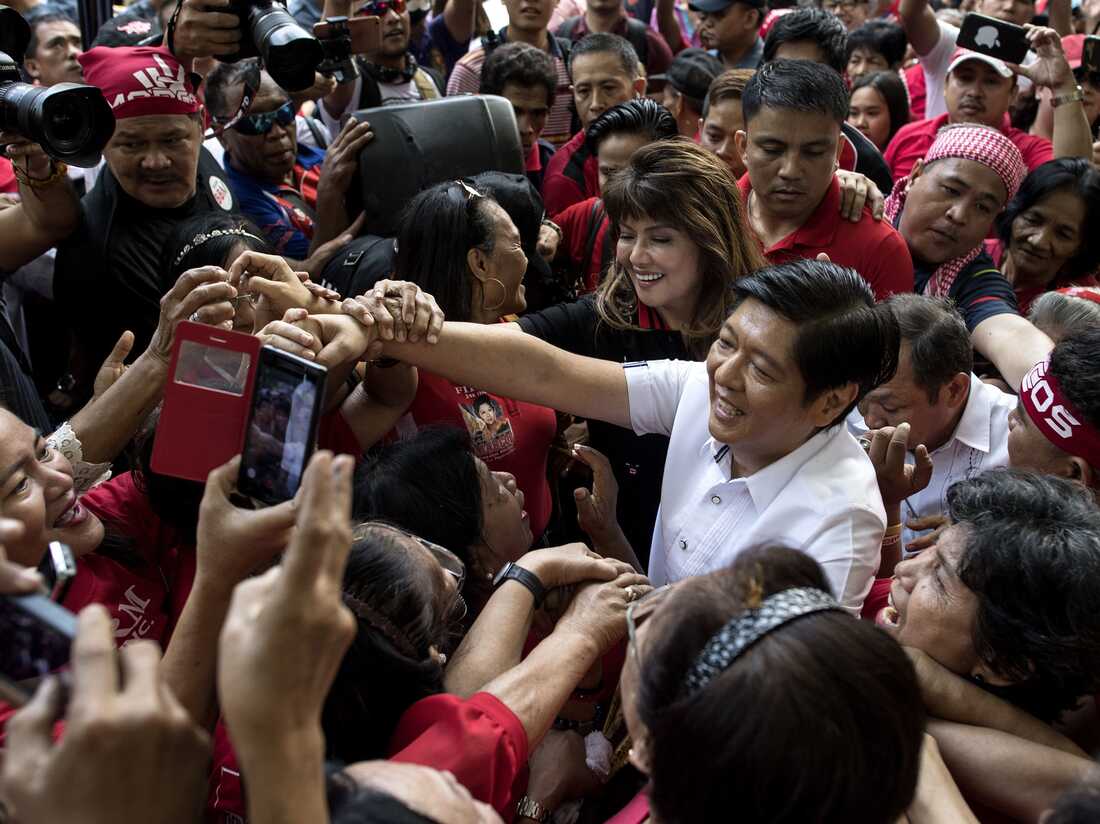

Ferdinand "Bongbong" Marcos Jr. is surrounded by supporters after attending the recount of votes in the 2016 vice presidential race at the Supreme Court. Marcos narrowly lost that contest to Leni Robredo, the current vice president. Noel Celis/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Ferdinand "Bongbong" Marcos Jr. is surrounded by supporters after attending the recount of votes in the 2016 vice presidential race at the Supreme Court. Marcos narrowly lost that contest to Leni Robredo, the current vice president.

Speaking at a recent online forum of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Arugay says second generation dynasts are behaving like a "cartel".

He says their calculus is as damaging as it is simple: "Why can't we just share power, limit competition, and make sure that the next winners of the presidential and national elections come from us?"

Then there is the celebrity factor.

Heydarian notes a narrowing of democracy in the pairing of dynasties with the celebrity class, which includes former film stars, television personalities and sports figures. He says the two elite groups monopolize national office, putting elected office beyond the reach of a lot of ordinary Filipinos who he says may have the merit and passion to serve, but are effectively blocked from fully participating.

It makes a "mockery" of democracy, Heydarian says, but it's also a trend that could be difficult to reverse.

"After all, in politics you need a certain degree of messaging, communications machinery and charisma," he said. And, he added, especially in the age of social media, "It's not for dull people."

Running on a name, not a track record

Consider Manny Pacquiao.

His stardom as one of the legends of the boxing world has catapulted him into the race for president next year. He is currently a sitting senator and is in the running for the highest office not on the power of his record in the upper chamber marked by absenteeism, but on the strength of his career as the country's most acclaimed athlete.

So prized have name recognition and celebrity status become in winning Philippine elections that observers worry it's turning democracy into the preserve of the rich and well-connected.

Marcos is part and parcel of the phenomenon, according to Manila-based analyst Bob Herrera-Lim, who notes that his undistinguished career as a senator and congressman has been no barrier to his ambition for the presidency.

"[Marcos] is running on entitlement. He is running on the weaknesses of the system," Herrera-Lim said.

Sara Duterte poses for a selfie with city hall employees in Davao city, on the southern island of Mindanao. Manman Dejeto/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Sara Duterte poses for a selfie with city hall employees in Davao city, on the southern island of Mindanao.

Marcos' vice presidential partner Sara Duterte is an accomplished politician, occupying the post her father held for decades as the mayor of Davao City, the third largest in the country. But the fact the 43-year-old First Daughter, whose work is little known outside Davao, led in a presidential opinion poll this past summer can only be put down to the power of a famous family name.

Revisionism, a PR campaign of distortion — and fond memories of the Marcos era

Bongbong Marcos is now making waves, rewriting the past and embellishing his family's legacy.

It's been 35 years since his father was ousted by a popular uprising, exiled, and exposed for rights abuses and kleptocracy.

Marcos Sr. is believed to have amassed up to $10 billion while in office, and now his son has been resuscitating the family's image with a sophisticated social media campaign.

Marcos Jr. narrates seamlessly scored videos that cast his parents, Ferdinand and Imelda, as generous philanthropists, and his father as a great innovator who made possible new strains of rice and united the archipelago with infrastructure heralded as the "Golden Age" of the Philippines.

Critics decry what they call the revisionist history and systematic airbrushing of the sins of the father's 20-year rule that turned the country into his personal fiefdom.

Marcos Sr. engaged in land-grabbing, bank-grabbing, and using dummies to hide acquisitions from public view, according to Professor Paul Hutchcroft of the Australian National University, who has written extensively on the political economy of the Philippines.

The late dictator dispensed special privileges to relatives, friends and cronies, writes Ronald Mendoza, dean of the School of Government at Ateneo de Manila University, providing them access to the booty of the state, "even as the country failed to industrialize and was eventually plunged into debt and economic crises in the mid-1980s."

Activists wear masks with anti-Marcos slogans during a rally in front of the Supreme court in Manila in 2016 as they await the high court's decision on whether to allow the burial of the late Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos at the "Cemetery of Heroes." Ted Aljibe/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Activists wear masks with anti-Marcos slogans during a rally in front of the Supreme court in Manila in 2016 as they await the high court's decision on whether to allow the burial of the late Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos at the "Cemetery of Heroes."

Yet, despite all of it, the Marcos family is not without its loyalists among both the elites and ordinary Filipinos.

At a small community market in central Manila, where fishmongers congregate amid aquariums and chopping blocks, vendors and shoppers talk about the Marcos era with a sense of nostalgia.

Chereelyn Dayondon, 49, says she likes how Marcos Sr. ran the country before and she wants that to come back. The single mother earns $80 a month directing traffic and worries that the cost of living is getting too high.

"It's not going to be enough," she says. "You never know, maybe Bongbong can change the Philippines. Let's try him out."

Meanwhile, fish seller Teodora Sibug-Nelval, 57, reminisces about the old Marcos era and memories of cheap food and law and order.

"I had a good life. I was able to send my sibling to school ... I was able to buy a house," she says.

In the pandemic, however, Sibug-Nelval lost her home and her vending stall. And now she wants her life back. She says she believes that if Marcos wins the election, "our lives will be better."

Herrera-Lim also says that many Filipinos see a confusing, chaotic political situation: "There is no clear delineations, political parties don't work for our benefit, we are looking for order."

And that, he says, is what Marcos is offering.

"Bongbong Marcos is saying that during his father's time, there was this order. There was peace in the country, which again, is a myth," he says.

The challenger to the dynasty

Leni Robredo is the current vice president of the Philippines and a liberal progressive.

A lawyer by training, Robredo co-authored an anti-dynasty bill when she served as a member of the Philippine House of Representatives.

In the Philippines, the vice president and president are elected separately and Robredo is on the opposite end of the political spectrum from President Duterte, with whom she has repeatedly sparred over human rights, the handling of the pandemic and Duterte's close ties with China.

Among the many candidates for president, including a former police chief, the mayor of Manila and Duterte's closest aide, Robredo appears to represent the greatest challenge to Bongbong Marcos.

Philippine Vice President Leni Robredo gestures to a crowd of supporters in Manila on Oct. 7, 2021, the day she filed her candidacy for the 2022 presidential race. Jam Sta Rosa/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Philippine Vice President Leni Robredo gestures to a crowd of supporters in Manila on Oct. 7, 2021, the day she filed her candidacy for the 2022 presidential race.

Robredo defeated Marcos Jr. for vice president in 2016, and now she has pledged that if she wins the top office, she will recover the Marcos family's plundered riches.

Alluding to Marcos' perceived popularity, Robredo told a news conference last weekend that it was "sad that the people allow themselves to be fooled" into believing Marcos would save the country when the family's ill-gotten wealth "was the reason they are poor."

Yet Robredo may need more than tough rhetoric and moral rectitude.

Marites Vitug, the editor-at-large for the online news site Rappler, whose CEO won this year's Nobel Peace Prize , said the country was witnessing the "rehabilitation of the Marcos dynasty." Young people were especially susceptible to the Marcos rebranding, she said, because there were no standard history textbooks in the Philippines that explained the Marcos martial law years.

"I was shocked to hear from some millennials that this was never discussed in class," she said.

Vitug said the odd teacher or professor may present it, but it was not systematic.

"It should have been required reading," she said.

Political economist Calixto Chikiamco adds that the revived Marcos family fortunes represent a counter-revolution to the one that ousted Marcos Sr. in 1986. That so-called Yellow Revolution was a model that Chikiamco says has failed to deliver genuine change.

"Because our politics remain dysfunctional, our economy is still not doing so well, a quarter of the workforce is unemployed ... still a large number of people go abroad to seek better opportunities. So it is a revolt against their present situation," he said.

"That's the reason the Marcoses are making a comeback."

The Duterte dynasty is a house divided

The campaign promises to be one of the Philippines' most bitterly fought contests in years, not least because the Marcos-Duterte tie-up has not won the blessing of Sara Duterte's father.

Rodrigo Duterte did make the controversial decision to allow the late dictator's remains to be moved to the "Cemetery of Heroes," a decision confirmed by the Supreme Court. But the once-friendly relations between Rodrigo Duterte and Bongbong Marcos have frayed, possibly beyond repair.

Duterte had wanted his daughter to seek the presidency, not play second fiddle, to provide him protection from the International Criminal Court investigating his violent anti-drug war. The probe has been suspended for a procedural review, but court watchers expect the case of alleged crimes against humanity to resume. Meanwhile, Chikiamco says while Sara may talk of continuing her father's policies, by declining to run for the top job, she has gone her own way.

"The daughter is fiercely independent and didn't want to be under the thumb of President Duterte. And also she could not perhaps tolerate the president's men," Chikiamco said.

A grandmother and her grandchild light a candle beside mock chalk figure representing an extra judicial killing victim during a prayer rally condemning the government's war on drugs in Manila in 2017. Noel Celis/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

A grandmother and her grandchild light a candle beside mock chalk figure representing an extra judicial killing victim during a prayer rally condemning the government's war on drugs in Manila in 2017.

Herrera-Lim adds that daughter and father apparently "did not see eye to eye on many things related to the family or on the governance of Davao."

Fundamentally, though, Herrera-Lim says President Duterte doesn't trust Bongbong Marcos to shield him from ICC prosecutors.

"On these matters, family is very important," he said.

And even if there were such a bargain between the two men, Herrera says Duterte would worry it might not hold.

In what analysts regard as a means to protect himself, Duterte is making a bid for a seat in the Senate in the 2022 election.

One authoritative poll shows Marcos the early frontrunner to succeed him. But not, it seems, if President Duterte has anything to say about it.

He ignited a stir earlier this month by declaring in a televised address that an unnamed candidate for president uses cocaine.

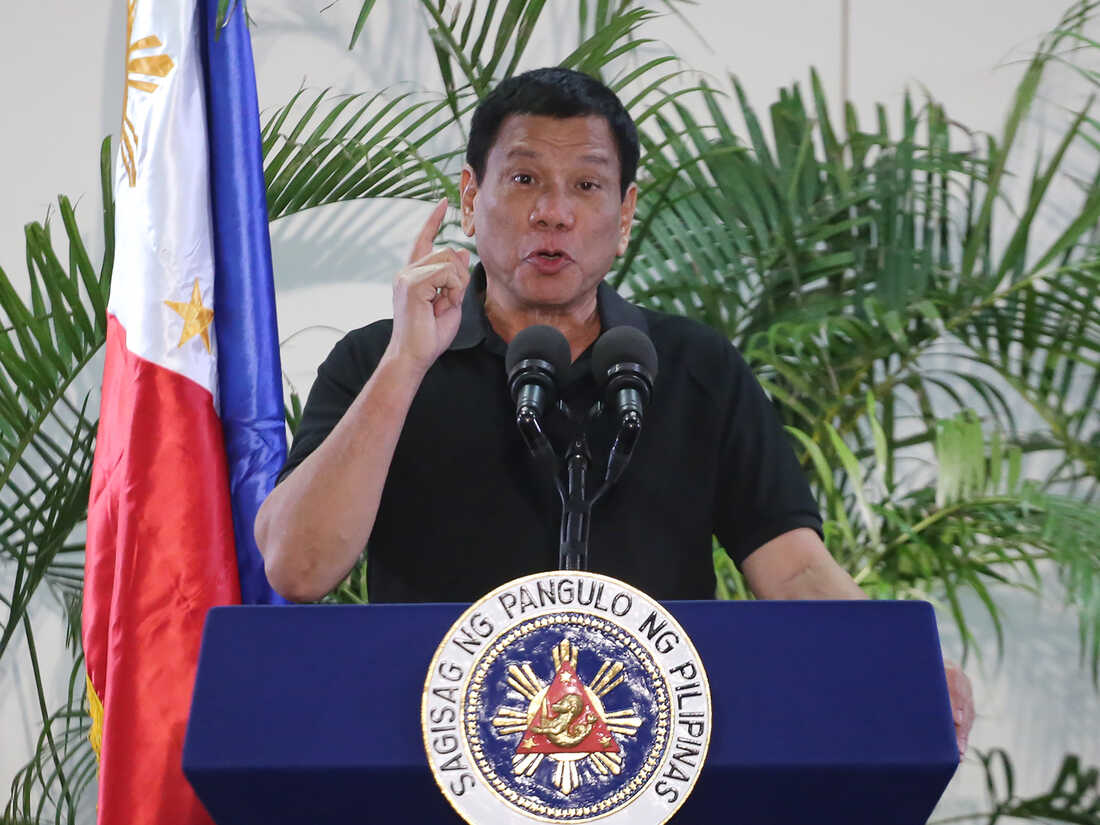

Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte. AFP/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte.

Without identifying who, he said the offender was a "very weak leader" and that "he might win hands down."

Marcos took a drug test this past week, saying he was clean. Other candidates hurriedly lined up to clear their name.

Marcos is also under attack by groups eager to have him disqualified from running at all. The Commission on Elections is reviewing four separate petitions challenging his candidacy. At least one charges that Marcos misrepresented his eligibility to seek the presidency by stating he had no criminal conviction that would bar him from office. Petitioners argue that his 1995 conviction for failing to pay taxes for several years in the 1980s ends his bid for the presidency.

The Commission on Elections announced no ballots will be printed until the petitions are decided.

The campaign that officially begins in February is already generating drama enough for some to lament that the race for president is fast becoming a "political circus."

But Richard Heydarian says circuses are not always the worst thing. "Sometimes," he says, "they can produce a magical outcome. Let's see."

Correction Dec. 16, 2021

An earlier version of this story incorrectly said Aries Arugay was a professor at Philippine University. He is with the University of the Philippines Diliman. Also, Ateneo de Manila University was misspelled as Ateno de Manila University.

- Subscribe Now

In The Public Square: Reforming Philippine political parties

Already have Rappler+? Sign in to listen to groundbreaking journalism.

One of the many crosses the Filipino people have had to bear is the political immaturity of our political parties. “Balimbing,” a choice insult from the 1980s, continues to sting because it continues to reflect one aspect of the lack of development among our political parties: party-switching for electoral and political convenience. There are, of course, other aspects.

What can be done to reform political parties in the Philippines?

In this episode of “In The Public Square,” Rappler host and editorial consultant John Nery is joined by former Dean of Liberal Arts at De La Salle University (DLSU) Julio “July” Teehankee. He is a full professor of political science in DLSU and the chief of party of the Participate consortium.

Watch the episode here on March 27, Wednesday at 8 pm. – Rappler.com

How does this make you feel?

Related Topics

Recommended stories, {{ item.sitename }}, {{ item.title }}, political parties, ex-davao hitman arturo lascañas resurfaces as uniteam sinks.

How Jokowi’s millennial son became the symbol of Indonesia’s newest political dynasty

All right for the Yuletide? Romualdez, Arroyo sit together for Lakas-CMD party picture

Leila de Lima is designated Liberal Party spokesperson

Political parties in the Philippines

Martin-sara duterte rift: house leaders back romualdez, decry ‘political bickering’.

PDP-Laban bigwigs form new party as Marcos enters second year

Group backs state-subsidized ‘democracy fund’ for political parties

‘Anti-balimbing’: Congress urged to pass decades-old bill vs party switching

Checking your Rappler+ subscription...

Upgrade to Rappler+ for exclusive content and unlimited access.

Why is it important to subscribe? Learn more

You are subscribed to Rappler+

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Elections in the Philippines is a time of alliances, pundits, politicking within and across party lines. A range of candidates have put themselves forward for the upcoming 2022 elections, though their agendas and positions may still be too cloudy for voters to make a clear bet. Persistent problems around politics are present, although reform via the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) is slowly ...

But even by those standards, this Marcos-Duterte coupling takes powerful clan politics to a new level, says University of the Philippines Diliman political science professor Aries Arugay ...

One of the many crosses the Filipino people have had to bear is the political immaturity of our political parties. “Balimbing,” a choice insult from the 1980s, continues to sting because it ...