Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

- Student Guide: Information Literacy | Meaning & Examples

Student Guide: Information Literacy | Meaning & Examples

Published on May 13, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on May 31, 2023.

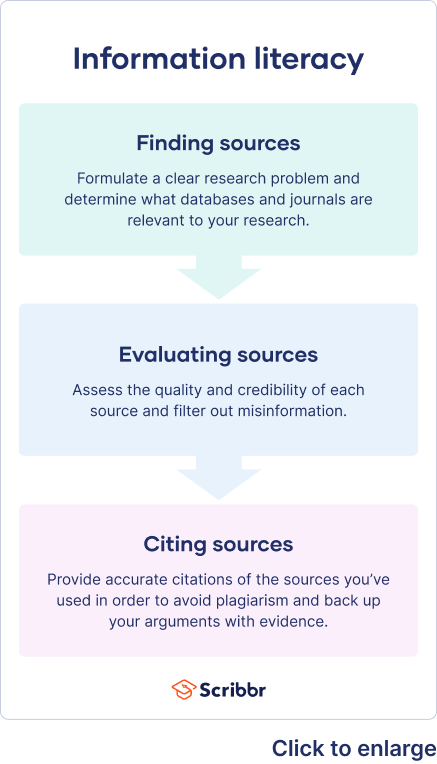

Information literacy refers to the ability to find, evaluate, and use sources effectively. The term covers a broad range of skills, including the ability to:

- Navigate databases

- Find credible sources

- Cite sources correctly

Table of contents

Why is information literacy important, information literacy skills, finding sources, evaluating sources, citing sources, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about information literacy.

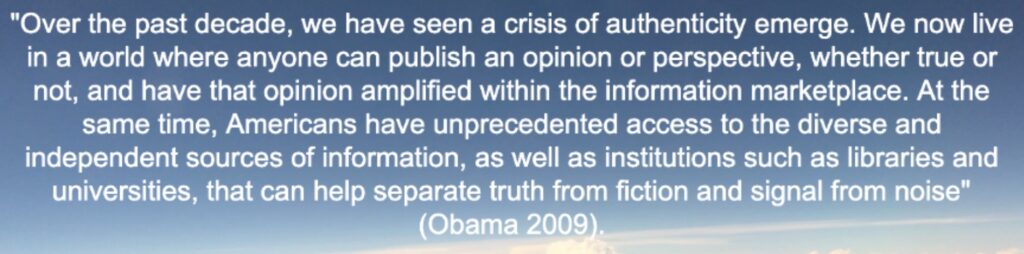

The vast amount of information available online means that it can be hard to distinguish accurate from inaccurate sources. Published articles are not always credible and sometimes reflect a biased viewpoint intended to sway the reader’s opinion.

Outside of academia, think of the concept of fake news : deliberately spreading misinformation intended to undermine other viewpoints. Or native advertising , designed to match other content on a site so that readers don’t notice they’re reading an advertisement.

It’s important to be aware of such unreliable content, to think critically about where you get your information, and to evaluate sources effectively, both in your research and in your media consumption more generally.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Information literacy is really a combination of skills and competencies that guide your research. Each stage of a research project, from choosing a thesis statement to writing your research paper , will require you to use specific skills and knowledge.

Being information literate means that you:

- Know how to find sources

- Can assess the authority and credibility of a source

- Can distinguish biased from unbiased content

- Can use relevant sources to inform your research

- Understand what constitutes plagiarism

- Know how to cite your sources correctly

An early stage in the research process is finding relevant sources. It’s important to understand how to search for these sources efficiently.

First, you need to consider what kind of sources you’re looking for. This will depend on the topic and focus of your project, and what stage you are at in the research process.

In the beginning, you may be looking for definitions or broad overviews of a topic. For this, you might use a tertiary source , like an encyclopedia or a dictionary, that is just for your own understanding. Further along, you might look for primary and secondary sources that you will actually cite in your paper. It’s important to ensure that all sources you consult are reliable.

- Websites: Look for websites with legitimate domain extensions (.edu or .gov).

- Search engines: When using search engines to find relevant academic journals and articles, use a trusted resource, like Google Scholar .

- Databases: Check your institution’s library resources to find out what databases they provide access to. Consider what databases are most appropriate to your research.

Finding the right sources means:

- Having a clear research problem

- Knowing what databases and journals are relevant to your research

- Knowing how to narrow and expand your search

Once you have a well-defined research problem, specific keywords, and have chosen a relevant database, you can use Boolean operators to narrow or expand your search. With them, you can prioritize and exclude keywords and search for exact phrases.

Evaluating the quality and credibility of a source is an important way of filtering out misinformation. A reliable source will be unbiased and informed by up-to-date research, and it will cite other credible sources.

You can evaluate the quality of a source using the CRAAP test . “CRAAP” is an acronym that informs the questions you should ask when analyzing a source. It stands for:

- Currency: Is the source recent or outdated?

- Relevance: Is it relevant to your research?

- Authority: Is the journal respected? Is the author an expert in the field?

- Accuracy: Is the information supported by evidence? Does the source provide relevant citations?

- Purpose: Why was the source published? What are the author’s intentions?

How you evaluate a source based on these criteria will depend on the specific subject. In the sciences, conclusions from a source published 20 years ago may have been disproven by recent findings. In a more interpretive subject like English, an article published decades ago might still be relevant.

Just as you look for sources that are supported by evidence and provide correct citations, your own work should provide relevant and accurate citations when you quote or paraphrase a source.

Citing your sources is important because it:

- Allows you to avoid plagiarism

- Establishes the credentials of your sources

- Backs up your arguments with evidence

- Allows your reader to verify the legitimacy of your conclusions

The most common citation styles are:

- APA Style : Typically used in the behavioral and social sciences

- MLA style : Used in the humanities and liberal arts

- Chicago style : Commonly used in the sciences and for history

It’s important to know what citation style your institute recommends. The information you need to include in a citation depends on the type of source you are citing and the specific citation style you’re using. An APA example is shown below.

You can quickly cite sources using Scribbr’s free Citation Generator .

If you want to know more about ChatGPT, AI tools , citation , and plagiarism , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- ChatGPT vs human editor

- ChatGPT citations

- Is ChatGPT trustworthy?

- Using ChatGPT for your studies

- What is ChatGPT?

- Chicago style

- Paraphrasing

Plagiarism

- Types of plagiarism

- Self-plagiarism

- Avoiding plagiarism

- Academic integrity

- Consequences of plagiarism

- Common knowledge

Information literacy refers to a broad range of skills, including the ability to find, evaluate, and use sources of information effectively.

- Know how to find credible sources

- Use relevant sources to inform your research

It can sometimes be hard to distinguish accurate from inaccurate sources , especially online. Published articles are not always credible and can reflect a biased viewpoint without providing evidence to support their conclusions.

Information literacy is important because it helps you to be aware of such unreliable content and to evaluate sources effectively, both in an academic context and more generally.

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

The CRAAP test is an acronym to help you evaluate the credibility of a source you are considering using. It is an important component of information literacy .

The CRAAP test has five main components:

- Currency: Is the source up to date?

- Relevance: Is the source relevant to your research?

- Authority: Where is the source published? Who is the author? Are they considered reputable and trustworthy in their field?

- Accuracy: Is the source supported by evidence? Are the claims cited correctly?

- Purpose: What was the motive behind publishing this source?

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, May 31). Student Guide: Information Literacy | Meaning & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/information-literacy/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, how to avoid plagiarism | tips on citing sources, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Information Literacy

11 A Beginner’s Guide to Information Literacy

By emily metcalf.

Introduction

Welcome to “A Beginner’s Guide to Information Literacy,” a step-by-step guide to understanding information literacy concepts and practices.

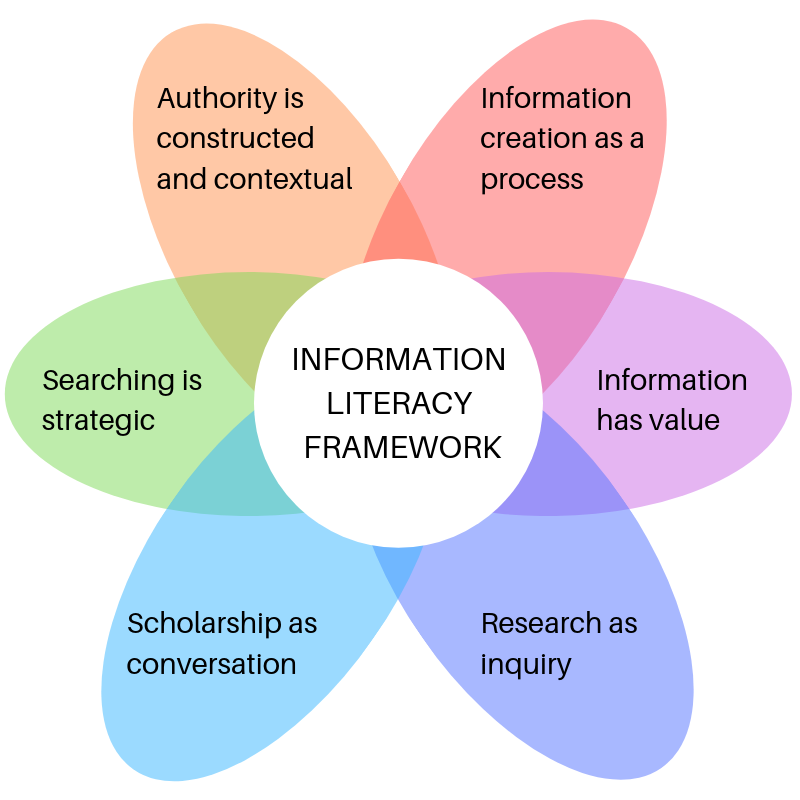

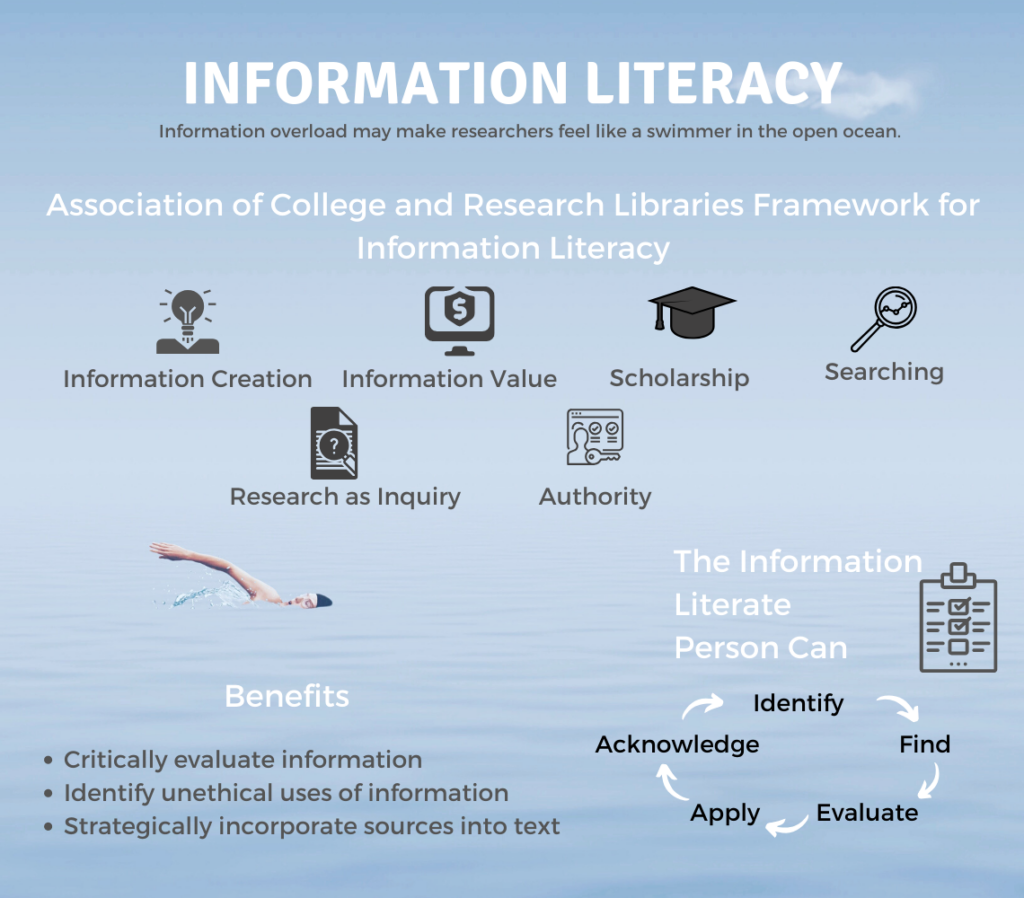

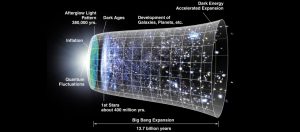

This guide will cover each frame of the “ Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education ,” a document created by the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) to help educators and librarians think about, teach, and practice information literacy (see Figure 11.1). The goal of this guide is to break down the basic concepts in the Framework and put them in accessible, digestible language so that we can think critically about the information we’re exposed to in our daily lives.

To start, let’s look at the ACRL definition of “information literacy,” so we have some context going forward:

Information Literacy is the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning.

Boil that down and what you have are the essentials of information literacy: asking questions, finding information, evaluating information, creating information, and doing all of that responsibly and ethically.

We’ll be looking at each of the frames alphabetically, since that’s how they are presented in the framework. None of these frames is more important than another, and all need to be used in conjunction with the others, but we have to start somewhere, so alphabetical it is!

In order, the frames are

- Authority is constructed and contextual

- Information creation as a process

- Information has value

- Research as inquiry

- Scholarship as conversation

- Searching as strategic exploration

Just because we’re laying this out alphabetically does not mean you have to go through it in order. Some of the sections reference frames previously mentioned, but for the most part you can jump to wherever you like and use this guide however you see fit. You can also open up the framework using the link above or in the attached resources to read the framework in its original form and follow along with each section.

The following sections originally appeared as blog posts for the Texas A&M Corpus Christi’s library blog. Edits have been made to remove institutional context, but you can see the original posts in the Mary and Jeff Bell Library blog archives .

Authority is Constructed and Contextual

The first frame is “ Authority is Constructed and Contextual .” There’s a lot to unpack in that language, so let’s get started.

Start with the word “authority.”

At the root of “authority” is the word “author.” So start there: who wrote the piece of information you’re reading? Why are they writing? What stake do they have in the information they’re presenting? What are their credentials (You can straight up google their name to learn more about them)? Who are they affiliated with? A public organization? A university? A company trying to make a profit? Check it out.

Now let’s talk about how authority is “constructed.”

Have you ever heard the phrase “social construct”? Some people say gender is a social construct or language, written and spoken, is a construct. “Constructed” basically means humans made it up at some point to instill order in their communities. It’s not an observable, scientifically inevitable fact. When we say “authority” is constructed, we’re basically saying that we as individuals and as a society choose who we give authority to, and sometimes we might not be choosing based on facts.

A common way of assessing authority is by looking at an author’s education. We’re inclined to trust someone with a PhD over someone with a high school diploma because we think the person with a PhD is smarter. That’s a construct. We’re conditioned to think that someone with more education is smarter than people with less education, but we don’t know it for a fact.

There are a lot of reasons someone might not seek out higher education. They might have to work full time or take care of a family or maybe they just never wanted to go to college. None of these factors impact someone’s intelligence or ability to think critically.

If aliens land on South Padre Island, TX, there will be many voices contributing to the information collected about the event. Someone with a PhD in astrophysics might write an article about the mechanical workings of the aliens’ spaceship. Cool; they are an authority on that kind of stuff, so I trust them.

But the teenager who was on the island and watched the aliens land has first-hand experience of the event, so I trust them too. They have authority on the event even though they don’t have a PhD in astrophysics.

So, we cannot think someone with more education is inherently more trustworthy or smarter or has more authority than anyone else. Some people who are authorities on a subject are highly educated, some are not.

Likewise, let’s say I film the aliens landing and stream it live on Facebook. At the same time, a police officer gives an interview on the news that says something contradicting my video evidence. All of a sudden, I have more authority than the police officer. Many of us are raised to trust certain people automatically based on their jobs, but that’s also a construct. The great thing about critical thinking is that we can identify what is fact and fiction, and we can decide for ourselves who to trust.

The final word is “contextual.”

This one is a little simpler. If I go to the hospital and a medical doctor takes out my appendix, I’ll probably be pretty happy with the outcome. If I go to the hospital and Dr. Jill Biden, a professor of English, takes out my appendix, I’m probably going to be less happy with the results.

Medical doctors have authority in the context of medicine. Dr. Jill Biden has authority in the context of education. And Doctor Who has authority in the context of inter-galactic heroics and nice scarves.

This applies when we talk about experiential authority, too. If an eighth-grade teacher tells me what it’s like to be a fourth-grade teacher, I will not trust their authority. I will, however, trust a fourth-grade teacher to tell me about teaching fourth grade.

The Takeaway

Basically, when we think about authority, we need to ask ourselves, “Do I trust them? Why?” If they do not have experience with the subject (like witnessing an event or holding a job in the field) or subject expertise (like education or research), then maybe they aren’t an authority after all.

P.S. I’m sorry for the uncalled-for dig, Dr. Biden. I’m sure you’d do your best with an appendectomy.

Ask Yourself

- In what context are you an authority?

- If you needed to figure out how to do a kickflip on a skateboard, who would you ask? Who’s an authority in that situation?

Information Creation as a Process

The second frame is “ Information Creation as a Process .”

Information Creation

So first of all, let’s get this out of the way: everyone is a creator of information. When you write an essay, you’re creating information. When you log the temperature of the lizard tank, you’re creating information. Every Word Doc, Google Doc, survey, spreadsheet, Tweet, and PowerPoint that you’ve ever had a hand in? All information products. That YOU created. In some way or another, you created that information and put it out into the world.

One process you’re probably familiar with if you’re a student is the typical research paper. You know your professor wants about five to eight pages consisting of an introduction that ends in a thesis statement, a few paragraphs that each touch on a piece of evidence that supports your thesis, and then you end in a conclusion paragraph which starts with a rephrasing of your thesis statement. You save it to your hard drive or Google Drive and then you submit it to your professor.

This is one process for creating information. It’s a boring one, but it’s a process.

Outside of the classroom, the information-creation process looks different, and we have lots of choices to make.

One of the choices you’ll need to make is the mode or format in which you present information. The information I’m creating right now comes to you in the mode of an Open Educational Resource . Originally, I created these sections as blog posts. Those five-page essays I mentioned earlier are in the mode of essays.

When you create information (outside of a course assignment), it’s up to you how to package that information. It might feel like a simple or obvious choice, but some information is better suited to some forms of communication. And some forms of communication are received in a certain way, regardless of the information in them.

For example, if I tweet “Jon Snow knows nothing,” it won’t carry with it the authority of my peer-reviewed scholarly article that meticulously outlines every instance in which Jon Snow displays a lack of knowledge. Both pieces of information are accurate, but the processes I went through to create and disseminate the information have an effect on how the information is received by my audience.

And that is perhaps the biggest thing to consider when creating information: your audience.

The Audience Matters

If I just want my twitter followers to know Jon Snow knows nothing, then a tweet is the right way to reach them. If I want my tenured colleagues and other various scholars to know Jon Snow knows nothing, then I’m going to create a piece of information that will reach them, like a peer-reviewed journal article.

Often, we aren’t the ones creating information; we’re the audience members ourselves. When we’re scrolling on Twitter, reading a book, falling asleep during a PowerPoint presentation—we’re the audience observing the information being shared. When this is the case, we have to think carefully about the ways information was created.

Advertisements are a good example. Some are designed to reach a 20-year old woman in Corpus Christi through Facebook, while others are designed to reach a 60-year old man in Hoboken, NJ over the radio. They might both be selling the same car, and they’re going to put the same information (size, terrain, miles per gallon, etc.) in those ads, but their audiences are different, so their information-creation process is different, and we end up with two different ads for different audiences.

Be a Critical Audience Member

When we are the audience member, we might automatically trust something because it’s presented a certain way. I know that, personally, I’m more likely to trust something that is formatted as a scholarly article than I am something that is formatted as a blog. And I know that that’s biased thinking and it’s a mistake to make that assumption.

It’s risky to think like that for a couple of reasons:

- Looks can be deceiving. Just because someone is wearing a suit and tie doesn’t mean they’re not an axe murderer and just because something looks like a well-researched article, doesn’t mean it is one.

- Automatic trust unnecessarily limits the information we expose ourselves to. If I only ever allow myself to read peer-reviewed scholarly articles, think of all the encyclopedias and blogs and news articles I’m missing out on!

If I have a certain topic I’m really excited about, I’m going to try to expose myself to information regardless of the format and I’ll decide for myself (#criticalthinking) which pieces of information are authoritative and which pieces of information suit my needs.

Likewise, as I am conducting research and considering how best to share my new knowledge, I’m going to consider my options for distributing this newfound information and decide how best to reach my audience. Maybe it’s a tweet, maybe it’s a Buzzfeed quiz, or maybe it’s a presentation at a conference. But whatever mode I choose will also convey implications about me, my information creation process, and my audience.

You create information all of the time. The way you package and share it will have an effect on how others perceive it.

- Is there a form of information you’re likely to trust at first glance? Either a publication like a newspaper or a format like a scholarly article?

- Can you think of some voices that aren’t present in that source of information?

- Where might you look to find some other perspectives?

- If you read an article written by medical researchers that says chocolate is good for your health, would you trust the article?

- Would you still trust their authority if you found out that their research was funded by a company that sells chocolate bars? Funding and stakeholders have an impact on the creation process, and it’s worth thinking about how this can compromise someone’s authority.

Information Has Value

Onwards and upwards! We’re onto frame 3: “ Information Has Value .”

What Counts as Value?

There are a lot of different ways we value things. Some things, like money, are valuable to us because we can exchange them for goods and services. On the other hand, some things, like a skill, are valuable to us because we can exchange them for money (which we exchange for more goods and services). Some things are valuable to us for sentimental reasons, like a photograph or a letter. Some things, like our time, are valuable because they are finite.

The Value of Information

Information has all kinds of value.

One kind is monetary. If I write a book and it gets published, I’m probably going to make some money off of that (though not as much money as the publishing company will make). So that’s valuable to me.

But I’m also getting my name out into the world, and that’s valuable to me too. It means that when I apply for a job or apply for a grant, someone can google me and think, “Oh look! She wrote a book! That means she has follow-through and will probably work hard for us!” That kind of recognition is a sort of social value. That social value, by the way, can also become monetary value. If I’ve produced information, a university might give me a job, or an organization might fund my research. If I’ve invented a machine that will floss my teeth for me, the patent for my invention could be worth a lot of money (plus it’d be awesome. Cool factor can count as value.).

In a more altruistic slant, information is also valuable on a societal level. When we have more information about political candidates, for example, it influences how we vote, who we elect, and how our country is governed. That’s some really valuable information right there. That information has an effect on the whole world (plus outer space, if we elect someone who’s super into space exploration). If someone is trying to keep information hidden or secret, or if they’re spreading misinformation to confuse people, it’s probably a sign that the information they’re hiding is important, which is to say, valuable.

On a much smaller scale, think about the information on food packages. If you’re presented with calorie counts, you might make a different decision about the food you buy. If you’re presented with an item’s allergens, you might avoid that product and not end up in an Emergency Room with anaphylactic shock. You know what’s super valuable to me? NOT being in an Emergency Room!

But if you do end up in the Emergency Room, the information that doctors and nurses will use to treat your allergic reaction is extremely valuable. That value of that information is equal to the lives it’s saved.

Acting Like Information is Valuable

When we create our own information by writing papers and blog posts and giving presentations, it’s really important that we give credit to the information we’ve used to create our new information product for a couple of reasons.

First, someone worked really hard to create something, let’s say an article. And that article’s information is valuable enough to you to use in your own paper or presentation. By citing the author properly, you’re giving the author credit for their work, which is valuable to them. The more their article is cited, the more valuable it becomes because they’re more likely to get scholarly recognition and jobs and promotions.

Second, by showing where you’re getting your information, you’re boosting the value of your new information product. On the most basic level, you’ll get a higher grade on your paper, which is valuable to you. But you’re also telling your audience, whether it’s your professor or your boss or your YouTube subscribers, that you aren’t just making stuff up—you did the work of researching and citing, and that makes your audience trust you more. It makes the audience value your information more.

Remember early on when I said the frames all connect? “Information Has Value” ties into the other information literacy frames we’ve talked about, “Information Creation as a Process” and “Authority as Constructed and Contextual.” When I see you’ve cited your sources of information, then I, as the audience, think you’re more authoritative than someone who doesn’t cite their sources. I also can look at your information product and evaluate the effort you’ve put into it. If you wrote a tweet, which takes little time and effort, I’ll generally value it less than if you wrote a book, which took a lot of time and effort to create. I know that time is valuable, so seeing that you were willing to dedicate your time to create this information product makes me feel like it’s more valuable.

Information is valuable because of what goes into its creation (time and effort) and what comes from it (an informed society). If we didn’t value information, we wouldn’t be moving forward as a society, we’d probably have died out thousands of years ago as creatures who never figured out how to use tools or start a fire.

So continue to value information because it improves your life, your audiences’ lives, and the lives of other information creators. More importantly, if we stop valuing information a smarter species will eventually take over and it’ll be a whole Planet of the Apes thing and I just don’t have the energy for that right now.

- Can you think of some ways in which a YouTube video on dog training has value? Who values it? Who profits from it?

- Think of some information that would be valuable to someone applying to college. What does that person need to know?

Research as Inquiry

Easing on down the road, we’ve come to frame number 4: “ Research as Inquiry .”

“Inquiry” is another word for “curiosity” or “questioning.” I like to think of this frame as “Research as Curiosity,” because I think it more accurately captures the way our adorable human brains work.

Inquiring Minds Want to Know

When you think to yourself, “How old is Madonna?” and you google it to find out she’s 62 (as of the creation of this resource), that’s research! You had a question (“how old is Madonna?”), you applied a search strategy (googling “Madonna age”) and you found an answer (62). That’s it! That’s all research has to be!

But it’s not all research can be. This example, like most research, is comprised of the same components we use in more complex situations. Those components are a question and an answer, inquiry and research, “how old is Madonna?” and “62.” But when we’re curious, we go back to the inquiry step again and ask more questions and seek more answers. We’re never really done, even when we’ve answered the initial question and written the paper and given the presentation and received accolades and awards for all our hard work. If it’s something we’re really curious about, we’ll keep asking and answering and asking again.

If you’re really curious about Madonna, you don’t just think, “How old is Madonna?” You think “How old is Madonna? Wait, really ? Her skin looks amazing! What’s her skincare routine? Seriously, what year was she born? Oh my god, she wrote children’s books! Does my library have any?” Your questions lead you to answers which, when you’re really interested in a topic, lead you to more and more questions. Humans are naturally curious ; we have this sort of instinct to be like, “huh, I wonder why that is?” and it’s propelled us to learn things and try things and fail and try again! It’s all research as inquiry.

And to satisfy your curiosity, yes, the library I currently work at does own one of Madonna’s children’s books. It’s called The Adventures of Abdi , and you can find it in our Juvenile Collection on the second floor at PZ8 M26 Adv 2004. And you can find a description of her skincare routine in this article from W Magazine: https://www.wmagazine.com/story/madonna-skin-care-routine-tips-mdna . You’re welcome.

Identifying an Information Need

One of the tricky parts of research as inquiry is determining a situation’s information need. It sounds simple to ask yourself, “What information do I need?” and sometimes we do it unconsciously. But it’s not always easy. Here are a few examples of information needs:

- You need to know what your niece’s favorite Paw Patrol character is so you can buy her a birthday present. Your research is texting your sister. She says, “Everest.” And now you’re done. You buy the present, you’re a rock star at the birthday party. Your information need was a short answer based on a three-year old’s opinion.

- You’re trying to convince someone on Twitter that Nazis are bad. You compile a list of opinion pieces from credible news publications like the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times , gather first-hand narratives of Holocaust survivors and victims of hate crimes, find articles that debunk eugenics, etc. Your information need isn’t scholarly publications, it’s accessible news and testimonials. It’s articles a person might actually read in their free time, articles that aren’t too long and don’t require access to scholarly materials that are sometimes behind paywalls.

- You need to write a literature review for an assignment, but you don’t know what a literature review is. So first you google “literature review example.” You find out what it is, how one is created, and maybe skim a few examples. Next, you move to your library’s website and search tool and try “oceanography literature review,” and find some closer examples. Finally, you start conducting research for your own literature review. Your information need here is both broader and deeper. You need to learn what a literature review is, how one is compiled, and how one searches for relevant scholarly articles in the resources available to you.

Sometimes it helps to break down big information needs into smaller ones. Take the last example, for instance: you need to write a literature review. What are the smaller parts?

- Information Need 1: Find out what a literature review is

- Information Need 2: Find out how people go about writing literature reviews

- Information Need 3: Find relevant articles on your topic for your own literature review

It feels better to break it into smaller bits and accomplish those one at a time. And it highlights an important part of this frame that’s surprisingly difficult to learn: ask questions. You can’t write a literature review if you don’t know what it is, so ask. You can’t write a literature review if you don’t know how to find articles, so ask. The quickest way to learn is to ask questions. Once you stop caring if you look stupid, and once you realized no one thinks poorly of people who ask questions, life gets a lot easier.

So, let’s add this to our components of research: ask a question, determine what you need in order to thoroughly answer the question, and seek out your answers. Not too painful, and when you’re in love with whatever you’re researching, it might even be fun.

- When you have a question, ask it.

- When you’re genuinely interested in something, keep asking questions and finding answers.

- When you have a task at hand, take a second to think realistically about the information you’ll need to accomplish that task. You don’t need a peer-reviewed article to find out if praying mantises eat their mates, but you might if you want to find out why.

- What’s the last thing you looked up on Wikipedia? Did you stop when you found an answer, or did you click on another link and another link until you learned about something completely different?

- If you can’t remember, try it now! Search for something (like a favorite book or tv show) and click on linked words and phrases within Wikipedia until you learn something new!

- What was the last thing you researched that you were really excited about? Do you struggle when teachers and professors tell you to “research something that interests you”? Instead, try asking yourself, “What makes me really angry?” You might find you have more interests than you realized!

Scholarship as Conversation

We’ve made it friends! My favorite frame: “ Scholarship as Conversation .” Is it weird to have a favorite frame of information literacy? Probably. Am I going to talk about it anyway? You betcha!

What does “Scholarship as Conversation” mean?

Scholarship as conversation refers to the way scholars reference each other and build off of one another’s work, just like in a conversation. Have you ever had a conversation that started when you asked someone what they did last weekend and ended with you telling a story about how someone (definitely not you) ruined the cake at your mom’s dog’s birthday party? And then someone says, “but like I was saying earlier…” and they take the conversation back to a point in the conversation where they were reminded of a different point or story? Conversations aren’t linear, they aren’t a clear line to a clear destination, and neither is research. When we respond to the ideas and thoughts of scholars, we’re responding to the scholars themselves and engaging them in conversation.

Why do I Love this Frame so Much?

Let me count the ways.

I really enjoy the imagery of scholarship as a conversation among peers. Just a bunch of well-informed curious people coming together to talk about something they all love and find interesting. I imagine people literally sitting around a big round table talking about things they’re all excited about and want to share with each other. It’s a really lovely image in my head. Eventually the image kind of reshapes and devolves into that painting of dogs playing poker, but I love that image too!

It harkens back to pre-internet scholarship, which sounds excruciating and exhausting, but it was all done for the love of a subject. Scholars used to literally mail each other manuscripts seeking feedback. Then, when they got an article published in a journal, scholars interested in the subject would seek out and read the article in the physical journal it was published in. Then they’d write reviews of the article, praising or criticizing the author’s research or theories or style. As the field grew, more and more people would write and contribute more articles to criticize and praise and build off of one another.

So, for example, if I wrote an article that was about Big Foot and then Joe wrote an article saying, “Emily’s article on Big Foot is garbage; here’s what I think about Big Foot,” Sam and I are now having a conversation. It’s not always a fun one, but we’re writing in response to one another about something we’re both passionate about. Later, Jaiden comes along and disagrees with Joe and agrees with me (because I’m right) and they cite both me and Joe. Now we’re all three in a conversation. And it just grows and grows and more people show up at the table to talk and contribute, or maybe just to listen.

Reason Three

You can roll up to the table and just listen if you want to. Sometimes we’re just listening to the conversation. We’re at the table, but we’re not there to talk. We’re just hoping to get some questions answered and learn from some people. When we’re reading books and articles or listening to podcasts or watching movies, we’re listening to the conversation. You don’t have to do groundbreaking research to be part of a conversation. You can just be there and appreciate what everyone’s talking about. You’re still there in the conversation.

Reason Four

You can contribute to the conversation at any time. The imagery of a conversation is nice because it’s approachable: just pull up a chair and start talking. With any new subject, you should probably listen a little at first, ask some questions, and then start giving your own opinion or theories, but you can contribute at any time. Since we do live in the age of internet research, we can contribute in ways people 50 years ago never dreamed of. Besides writing essays in class (which totally counts because you’re examining the conversation and pulling in the bits you like and citing them to give credit to other scholars), you can talk to your professors and friends about a topic, you can blog about it, you can write articles about it, you can even tweet about it (have you ever seen Humanities folk on Twitter? They go nuts on there having actual, literal scholarly conversations). Your ways for engaging are kind of endless!

Reason Five

Yep, I’m listing reasons.

Conversations are cyclical. Like I said above, they’re not always a straight path and that’s true of research too. You don’t have to engage with who spoke most recently; you can engage with someone who spoke ten years ago, someone who spoke 100 years ago, you can even respond to the person who started the conversation! Jump in wherever you want. And wherever you do jump in, you might just change the course of the conversation. Because sometimes we think we have an answer, but then something new is discovered or a person who hadn’t been at the table or who had been overlooked says something that drastically impacts what we knew, so now we have to reexamine it all over again and continue the conversation in a trajectory we hadn’t realized was available before.

Lastly, this frame is about sharing and responding and valuing one another’s work. If Joe, my Big Foot nemesis, responds to my article, they’re going to cite me. If Jaiden then publishes a rebuttal, they’re going to cite both Joe and me, because fair is fair. This is for a few reasons: 1) even if Jaiden disagrees with Joe’s work, they respect that Joe put effort into it and it’s valuable to them. 2) When Jaiden cites Joe, it means anyone who jumps into the conversation at the point of Jaiden’s article will be able to backtrack and catch up using Jaiden’s citations. A newcomer can trace it back to Joe’s article and trace that back to mine. They can basically see a transcript of the whole conversation so they can read Jaiden’s article with all of the context, and they can write their own well-informed piece on Big Foot.

There’s a lot to take away from this frame, but here’s what I think is most important:

- Be respectful of other scholars’ work and their part in the conversation by citing them.

- Start talking whenever you feel ready, in whatever platform you feel comfortable.

- Make sure everyone who wants to be at the table is at the table. This means making sure information is available to those who want to listen and making sure we lift up the voices that are at risk of being drowned out.

- What scholarly conversations have you participated in recently? Is there a Reddit forum you look in on periodically to learn what’s new in the world of cats wearing hats? Or a Facebook group on roller skating? Do you contribute or just listen?

- Think of a scholarly conversation surrounding a topic—sharks, ballet, Game of Thrones. Who’s not at the table? Whose voice is missing from the conversation? Why do you think that is?

Searching as Strategic Exploration

You’ve made it! We’ve reached the last frame: Searching as Strategic Exploration .

“Searching as Strategic Exploration” addresses the part of information literacy that we think of as “Research.” It deals with the actual task of searching for information, and the word “Exploration” is a really good word choice, because it’s evocative of the kind of struggle we sometimes feel when we approach research. I imagine people exploring a jungle, facing obstacles and navigating an uncertain path towards an ultimate goal (Note: the goal is love and it was inside of us all along). I also kind of imagine all the different Northwest Passage explorations, which were cool in theory, but didn’t super-duper work out as expected.

But research is like that! Sometimes we don’t get where we thought we were headed. But the good news is this: You probably won’t die from exposure or resort to cannibalism in your research. Fun, right?

Step 1: Identify a Goal

The first part of any good exploration is identifying a goal. Maybe it’s a direct passage to Asia or the diamond the old lady threw into the ocean at the end of Titanic. More likely, the goal is to satisfy an information need. Remember when we talked about “Research as Inquiry?” All that stuff about paw patrol and Madonna’s skin care regimen? Those were examples of information needs. We’re just trying to find an answer or learn something new.

So great! Our goal is to learn something new. Now we make a strategy.

Step 2: Make a Strategy

For many of your information needs you might just need to Google a question. There’s your strategy: throw your question into Google and comb through the results. You might limit your search to just websites ending in .org, .gov, or .edu. You might also take it a step further and, rather than type in an entire question fully formed, you just type in keywords. So “Who is the guy who invented mayonnaise?” becomes “mayonnaise inventor.” Identifying keywords is part of your strategy and so is using a search engine and limiting the results you’re interested in.

Step 3: Start Exploring

Googling “mayonnaise inventor” probably brings you to Wikipedia where we often learn that our goals don’t have a single, clearly defined answer. For example, we learn that mayonnaise might have gotten its name after the French won a battle in Port Mahon, but that doesn’t tell us who actually made the mayonnaise, just when it was named. Prior to being named, the sauce was called “aioli bo” and was apparently in a Menorcan recipe book from 1745 by Juan de Altimiras. That’s great for Altimiras, but the most likely answer is that mayonnaise was invented way before him and he just had the foresight to write down the recipe. Not having a single definite answer is an unforeseen obstacle tossed into our path that now affects our strategy. We know we have a trickier question than when we first set sail.

But we have a lot to work with! We now have more keywords like “Port Mahon,” “the French,” and Wikipedia taught us that the earliest known mention of “mayonnaise” was in 1804, so we have “1804” as a keyword too.

Let’s see if we can find that original mention. Let’s take our keywords out of Wikipedia where we found them and voyage to a library’s website! At my library we have a tool that searches through all of our resources. We call it the “Quick Search.” You might have a library available to you, either at school, on a university’s campus, or a local public library. You can do research in any of these places!

So into the Quick Search tool (or whatever you have available to you) go our keywords: “1804,” “mayonnaise,” and “France.” The first result I see is an e-book by a guy who traveled to Paris in 1804, so that might be what we’re looking for. I search through the text and I do, in fact, find a reference to mayonnaise on page 99! The author (August von Kotzebue) is talking about how it’s hard to understand menus at French restaurants, for “What foreigner, for instance, would at first know what is meant by a mayonnaise de poulet, a galatine de volaille, a cotelette a la minute, or even an epigramme d’agneau?” He then goes on to recommend just ordering the fish, since you’ll know what you’ll get (Kotzebue 99).

So that doesn’t tell us who invented mayonnaise, but I think it’s pretty funny! So I’d call that detour a win.

Step 4: Reevaluate

When we hit ends that we don’t think are successful, we can always retrace our steps and reevaluate our question. Dead ends are a part of exploration! We’ve learned a lot, but we’ve also learned that maybe “who invented mayonnaise?” isn’t the right question. Maybe we should ask questions about the evolution of French cuisine or about ownership of culinary experimentation.

I’m going to stick with the history of mayonnaise, for just a little while longer, but my “1804 mayonnaise France” search wasn’t as helpful as I’d hoped, so I’ll try something new. Let’s try looking at encyclopedias.

I searched in a database called Credo Reference (which is a database filled with encyclopedia entries) and just searching “mayonnaise.” I can see that the first entry, “Minorca or Menorca” from The Companion to British History , doesn’t initially look helpful, but we’re exploring, so let’s click on it. It tells us that mayonnaise was invented in 1756 by a French commander’s cook and its name comes from Port Mahon where the French fended off the British during a siege ( Arnold-Baker, 2001 ). That’s awesome! It’s what Wikipedia told us! But let’s corroborate that fact. I click on The Hutchinson Chronology of World History entry for 1756, which says mayonnaise was invented in France in 1756 by the duc de Richelieu ( Helicon, 2018 ). I’m not sure I buy it. I could see a duke’s cook inventing mayonnaise, but I have a hard time imagining a duke and military commander taking the time to create a condiment.

But now I can go on to research the duc de Richelieu and his military campaigns and his culinary successes. Just typing “Duke de Richelieu” into the library’s Quick Search shows me a TON of books (16,742 as of writing this) on his life and he influence on France. So maybe now we’re actually exploring Richelieu or the intertwined history of French cuisine and the lives of nobility.

What Did We Just Do?

Our strategy for exploring this topic has had a lot of steps, but they weren’t random. It was a wild ride, but it was a strategic one. Let’s break the steps down real quick:

- We asked a question or identified a goal

- We identified keywords and googled them

- We learned some background information and got new keywords from Wikipedia and had to reevaluate our question

- We followed a lead to a book but hit a dead end when it wasn’t as useful as we’d hoped

- We identified an encyclopedia database and found several entries that support the theory we learned in Wikipedia, which forced us to reevaluate our question again

- We identified a key player in our topic and searched for him in the library’s Quick Search tool and the resources we found made us reevaluate our question yet again

Other strategies could include looking through an article’s reference list, working through a mind map , outlining your questions, or recording your steps in a research log so you don’t get lost—whatever works for you!

Exploration is tricky. Sometimes you circle back and ask different questions as new obstacles arise. Sometimes you have a clear path and you reach your goal instantly. But you can always retrace your steps, try new routes, discover new information, and maybe you’ll get to your destination in the end. Even if you don’t, you’ve learned something.

For instance, today we learned that if you can’t understand a menu in French, you should just order the fish.

- Where do you start a search for information? Do you start in different places when you have different information needs?

- If your research question was “What is the impact of fast fashion on carbon emissions?” What keywords would you use to start searching?

The Framework for Information Literacy in Higher Education is one heck of a document. It’s complicated, its frames intertwine, it’s written in a way that can be tricky to understand. But essentially, it’s just trying to get us to understand that the ways we interact with information are complicated and we need to think about our interactions to make sure we’re behaving in an ethical and responsible way.

Why do your professors make you cite things? Because those citations are valuable to the original author, and they prove your engagement with the scholarly conversation. Why do we need to hold space in the conversation for voices that we haven’t heard from before? Because maybe no one recognized the authority in those voices before. The old process for creating information shut out lots of voices while prioritizing others. It’s important for us to recognize these nuances when we see what information is available to us and important for us to ask, “Whose voice isn’t here? Why? Am I looking hard enough for those voices? Can I help amplify them?” And it’s important for us to ask, “Why is the loudest voice being so loud? What motivates them? Why should I trust them over others?”

When we think critically about the information we access and the information we create and share, we’re engaging as citizens in one big global conversation. Making sure voices are heard, including your own voice, is what moves us all towards a more intelligent and understanding society.

Of course, part of thinking critically about information means thinking critically about both this guide and the framework. Lots of people have criticized the framework for including too much library jargon. Other folks think the framework needs to be rewritten to explicitly address how information seeking systems and publishing platforms have arisen from racist, sexist institutions. We won’t get into the criticisms here, but they’re important to think about. You can learn more about the criticism of the framework in a blog post by Ian Beilin , or you can do your own search for criticism on the framework to see what else is out there and form your own opinions.

The Final Takeaway

Ask questions, find information, and ask questions about that information.

Attributions

“A Beginner’s Guide to Introduction to Information Literacy” by Emily Metcalf is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA

Writing Arguments in STEM Copyright © by Jason Peters; Jennifer Bates; Erin Martin-Elston; Sadie Johann; Rebekah Maples; Anne Regan; and Morgan White is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Feedback/errata.

Comments are closed.

- How it works

What is Information Literacy – A Complete Student Guide with Examples

Published by Olive Robin at October 17th, 2023 , Revised On October 17, 2023

Information literacy is more than just the ability to find information; it encompasses the skills to recognise when information is needed and the competence to locate, evaluate, use, and ethically disseminate it. Part of this skill includes understanding paraphrasing in sources and knowing how to integrate sources seamlessly into one’s work.

It is about discerning between reliable and dubious sources, understanding context, and using information to create knowledge and make informed decisions.

Importance of Information Literacy in the Digital Age

In today’s digital age, we are bombarded with vast amounts of information at an unprecedented rate. From the articles we read online and the news we consume to the social media posts we encounter daily, there’s a constant flow of information. This massive influx makes the need for information literacy paramount for several reasons:

Combating Misinformation

With the surge of the internet, misinformation, fake news, and biased content have become rampant. Information literacy skills ensure that individuals can discern credible sources from unreliable ones, thus preventing the spread of falsehoods.

Empowering Decision-Making

Whether it is making health decisions based on an online article, purchasing a product after reading reviews, or forming opinions on socio-political matters, information literacy ensures decisions are grounded in well-researched and credible facts.

Nurturing Lifelong Learning

In an ever-evolving digital landscape, information literacy fosters a sense of curiosity, encouraging individuals to seek out reliable information, continually expand their knowledge base, and adapt to the changing world.

Ethical Consumption and Sharing

Information literacy is not just about consumption; it’s also about dissemination. Being information literate means sharing and using information ethically, respecting copyrights, and acknowledging original sources.

Staying Safe Online

With the rise of digital scams, phishing attempts, and misleading websites, information literacy can act as a first line of defence, helping individuals recognise suspicious sources and protect themselves from potential harm.

History and Evolution of Information Data and Media Literacies

Here is how information literacy evolved.

Pre-Digital Era Information Management

Long before the digital era, information was primarily disseminated through oral traditions, manuscripts, and later, printed material. The concept of information literacy, although not named as such, existed in various forms:

Libraries And Cataloguing

With the creation of libraries, such as the famous Library of Alexandria, there was a need to organise and catalogue vast amounts of knowledge. Librarians became gatekeepers and guides, assisting scholars and the public in pursuing knowledge.

The Printing Press

Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press in the 15th century democratised information access. As books became more accessible, so did the need to critically assess and discern their content quality.

Educational Evolution

As education became more widespread, curricula began emphasising critical thinking, source evaluation, and proper research methodologies, laying the groundwork for modern information literacy principles.

The Rise of the Internet and Digital Sources

The advent of the internet brought about a seismic shift in how information was accessed, shared, and understood:

Information Overload

Suddenly, vast amounts of information were available at the click of a button. While this opened up unparalleled access to knowledge, it also led to an overwhelming amount of data, making discernment crucial.

Digital Libraries and Databases

Libraries transitioned online, offering digital catalogues, e-books, and academic databases, requiring users to adapt and learn new search techniques.

Search Engines

Google, Yahoo, and others revolutionised information access. However, with their algorithmic operations, the challenge of understanding how results were ranked and the potential biases therein arose.

Modern-Day Importance in an Era of Fake News and Misinformation

In the current digital landscape, information literacy is not just a valuable skill; it is a necessity for responsible citizenship:

The Misinformation Epidemic

The speed at which information spreads online, combined with algorithms that prioritise sensational content, has made fake news a global concern. Information literacy provides the tools to assess and verify the authenticity of news and articles critically.

Social Media’s Role

Platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram have transformed into major news sources for many. With the rise of user-generated content, understanding biases, source credibility, and the potential for echo chambers becomes vital.

Critical Thinking in the Digital Age

With so much data at our fingertips, the ability to analyse, synthesise, and draw independent conclusions is paramount. Information literacy goes beyond just finding information — it is about understanding context implications and making informed judgments.

Educational Shifts

Institutions now emphasise digital literacy and information literacy as core competencies, preparing students not just for academia but for responsible digital citizenship.

Key Components of Information Literacy

Some of the key components of information literacy include the following.

Recognising The Need for Information

Before diving into research or seeking answers, one must first identify the information gap that exists:

Understanding the Question

Whether it is a research question, a task at work, or personal curiosity, it is essential to clarify what you are seeking. This clarity aids in focused and effective research.

Gauging Current Knowledge

Reflect on what you already know about the topic, and identify the areas that require further exploration.

Identifying Sources of Information

With a clear understanding of what is needed, the next step involves knowing where to look:

Traditional Sources

These include books, journals, newspapers, and other printed materials.

Digital Databases

Online academic databases like JSTOR, PubMed, and Google Scholar offer a wealth of scholarly articles and publications.

Online Platforms

Websites, blogs, forums, and even social media can be valuable, depending on the topic, but require a keen eye for credibility.

Experts and Practitioners

Sometimes, the best information source is someone with expertise in the field of interest.

How to Evaluate the Credibility and Relevance of Sources

Not all sources are created equal. Source evaluation is paramount, and ensuring that the information you rely on is both credible and relevant is crucial:

Check the qualifications and background of the author or the publishing body.

Publication Date

Especially for rapidly evolving fields, the timeliness of the information is essential.

Citations and References

Quality sources usually refer to or are referenced by other credible works.

Bias and Objectivity

Every source has a perspective. Identifying potential biases helps evaluate the objectivity of the information.

Relevance to The Research Question

Ensure the information directly addresses your initial need or question.

Organising, Synthesising, and Using the Information Effectively

Once credible sources are identified, the next step is to derive meaningful insights:

Note-Taking

Highlighting key points, annotating, or using digital tools can help consolidate information.

Combining information from multiple sources provides a well-rounded understanding, allowing for fresh insights and connections.

Application

Use the gathered information to answer your research question, make decisions, or inform others. The true test of information literacy is not just gathering data, but effectively employing it.

Ethical Considerations and Information Use

Using information comes with a responsibility to respect intellectual property and avoid misrepresentation:

Citing Sources

Whenever borrowing ideas, quotes, or data, always provide appropriate citations. Source citing is crucial not only to acknowledge the original creators but also to add credibility to your work.

Avoiding Plagiarism

Using someone else’s work without proper credit is not only unethical but can also have legal implications.

Understanding Copyright

Different sources have different copyright restrictions. Always ensure you have the right to use, reproduce, or share the information, especially in public or commercial settings.

Sharing Responsibly

In this digital age, information spreads rapidly. Ensure that what you share is accurate, and when in doubt, verify before disseminating.

Real-Life Examples Of Information Literacy

To understand this better, here are a few real-life information literacy examples.

Academic Research

Research forms the cornerstone of academic endeavours. Information literacy ensures that the research is thorough, credible, and based on strong evidence.

1. Determining the credibility of a research paper

- The journal in which it was published – is it peer-reviewed?

- The author’s qualifications and affiliations.

- Citations within the paper – are they from credible sources?

- Any potential biases or conflicts of interest mentioned in the paper.

2. Differentiating primary and secondary sources

- Primary sources might include letters from soldiers, official documents, or photographs from the era.

- Secondary sources would be books or articles written about World War II, often using primary sources as references.

Every Day Decision-Making

In our day-to-day lives, we constantly make choices based on the information we consume.

1. Fact-checking a news article

- Check the article’s source – is it a reputable news outlet?

- Searches for the same news on other trusted platforms to corroborate the story.

- Look for expert opinions or official statements within the article.

2. Deciphering product reviews and making informed purchases

- Reads reviews on multiple platforms, not just the product’s official page.

- Differentiates genuine user reviews from potential fake ones by observing patterns or checking review verification.

- Balances out overly positive and overly negative reviews to get a comprehensive understanding.

Digital And Social Media

The digital world, especially social media, presents both a boon and a bane regarding information consumption.

1. Recognizing biased content or sponsored posts

- Checks for tags or mentions indicating if the post is sponsored.

- Reads comments to see if other users had genuine experiences with the product.

- Look for more reviews online before making a decision.

2. Avoiding online scams and understanding online privacy

- Checks the sender’s email address for any discrepancies.

- Doesn’t provide personal or financial information without verifying the authenticity of the email.

- Stays informed about common online scams and always errs on the side of caution.

The research done by our experts have:

- Precision and Clarity

- Zero Plagiarism

- Authentic Sources

Information Literacy Skills for Students

A. research strategies and tools.

As students embark on academic journeys, harnessing effective research tools and strategies is essential to navigate the vast sea of information.

1. Using academic databases and search engines effectively

- She accesses academic databases like JSTOR, PubMed, and Google Scholar to find peer-reviewed articles.

- Uses advanced search features to narrow down results, filtering by date, relevance, or specific journals.

- Saves and organises her findings using reference management tools like Zotero or Mendeley.

2. Understanding how algorithms impact search results

- Search engines use personalised algorithms based on user data, browsing history, and location.

- Incognito or private browsing can provide more neutral results.

- Cross-checking information across multiple platforms ensures diverse perspectives.

B. Critical Thinking and Questioning

Students must cultivate an analytical mindset and embrace a curious spirit to distil valuable insights from information.

1. Asking the right questions

- Formulating specific questions: “How does a Mediterranean diet impact depression rates?”

- Considering potential biases in studies, such as funding sources or sample sizes.

- Being open to revising her questions as she learns more.

2. Looking for corroborative sources

- Searching for other studies or experts that confirm or refute the findings.

- Analysing the methodologies used in the study for potential flaws.

- Considering the broader consensus in the scientific community on the topic.

C. Communication in Information Literacy and Collaboration

Sharing knowledge and collaborating on projects amplifies the learning experience, but it also comes with the responsibility of ensuring accurate and respectful information exchange.

1. Sharing information responsibly

- Citing the original source and giving credit to the author.

- Summarising the article in her own words and avoiding plagiarism.

- Encouraging peers to read the original article and form their own opinions.

2. Collaborating with peers in group research

- They divide topics among themselves to avoid overlapping research.

- Share resources using digital tools like Google Drive or Dropbox.

- Regularly meet to discuss findings, ensuring everyone’s on the same page and synthesising information cohesively.

Tips for Enhancing Information Literacy

Navigating the modern world requires a high degree of information literacy. As the digital realm continues to grow and evolve, so too does the importance of cultivating and refining these skills. Here are some actionable tips to enhance information literacy:

Attend Workshops or Training Sessions

Workshops and training sessions, often organised by libraries, educational institutions, or professional organisations, offer hands-on learning experiences.

- Exposure to a structured curriculum tailored to improving research and information analysis skills.

- Opportunity to learn from experts in the field.

- Networking with like-minded individuals can lead to collaborative learning.

Implementation:

- Look for local workshops at community centres, libraries, or universities.

- Explore online platforms like Coursera, Udemy, or edX for courses on information literacy and related subjects.

- Attend conferences or seminars, which often feature sessions on the latest in research methodologies.

Stay Updated with Evolving Research Tools

Staying abreast of the latest research tools is paramount with the digital landscape continuously changing.

- Efficiently locate and access information.

- Stay competitive in academic or professional settings by using the latest tools.

- Ensure the quality and credibility of the information you gather.

- Subscribe to newsletters or blogs focusing on research methodologies or academic resources.

- Participate in webinars or online demos when new tools or platforms are released.

- Join online forums or groups where members share and discuss their favourite tools.

Engage in Regular Discussions and Debates

Engaging in discussions helps refine your understanding and challenges your preconceptions.

- Enhance critical thinking skills.

- Expose yourself to diverse viewpoints and sources.

- Develop the ability to defend your research or change your stance based on new information.

- Join debate clubs or discussion groups in your community or institution.

- Participate in online forums or social media groups that focus on topics of interest.

- Organise or attend regular meetups or discussion sessions with peers.

Be Proactive in Seeking Feedback on Research Techniques

Continuous improvement is a cornerstone of information literacy. Seeking feedback ensures your methods stay rigorous and effective.

- Identify areas of improvement in your research approach.

- Learn from the expertise and experience of others.

- Build confidence in your research abilities by validating your methods.

- After completing a research project, ask peers, mentors, or experts to review your methodology.

- Use platforms like ResearchGate to share your work and gather feedback from the global academic community.

- Reflect on feedback, and actively incorporate suggestions into future research endeavours.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is information literacy with example.

Information literacy is the ability to locate, evaluate, and use information effectively. For example, when researching climate change, an information literate person can distinguish between reputable scientific sources and biased or unreliable content, ensuring the information they use is accurate and trustworthy.

What are the 5 information literacy skills?

- Identifying the need for information.

- Locating and accessing the information.

- Evaluating the quality and relevance of the information.

- Using the information effectively for a specific purpose.

- Understanding and applying ethical and legal aspects of using information.

What is the main point of information literacy?

The main point of information literacy is to empower individuals to effectively find, evaluate, and use information. This skill set helps in making informed decisions, both in academic pursuits and everyday life, fostering critical thinking, informed citizenship, and lifelong learning in an ever-evolving information landscape.

You May Also Like

Scholarly sources, also known as academic sources, refer to materials created to meet the standards and expectations of the academic community.

Critical thinking is the disciplined art of analysing and evaluating information or situations by applying a range of intellectual skills. It goes beyond mere memorisation or blind acceptance of information, demanding a deeper understanding and assessment of evidence, context, and implications.

A secondary source refers to any material that interprets, analyses, or reviews information originally presented elsewhere. Unlike primary sources, which offer direct evidence or first-hand testimony, secondary sources work on those original materials, offering commentary, critiques, and perspectives.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

Table of Contents

Collaboration, information literacy, writing process, information literacy – discerning quality information from noise.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating , evaluating , using , and archiving information . In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a capital good such as money or social influence — you need to be strategic about how you consume and use information .

What is Information Literacy?

Information Literacy may be refer to

- the ability to recognize “when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate and use the needed information ” (American Library Association, 1989)

- “a cluster of interconnected core activities, frameworks” that constitute information ecosystems ( ACRL 2015 )

- Consuming, evaluating, producing, managing, using, and archiving information–these are topics of ongoing scholarship in information studies, writing studies , and related disciplines. This topic is under constant evolution as new communication technologies evolve.

What is Information? Information is everything your senses perceive, including visual, auditory, or kinesthetic data ( more ).

What is Literacy? Literacy is the ability to identify, interpret signs , and communicate with signs , using whatever medium or semiotic system the audience(s) expects you to use.

Synonymous Terms

Information Literacy may also be called

- Data Information Literacy

- Science Communication

- STEM Literacy for Learning.

Related Concepts: Authority (in Speech and Writing) ; Copyright ; Critical Literacy ; Evidence ; Plagiarism ; Rhetorical Analysis ; Rhetorical Reasoning ; Semiotics ; The CRAAP Test

Why Does Information Literacy Matter?

In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a capital good such as money or social influence — you need to be strategic about how you consume and use information. If you accept what people tell you without engaging in critical literacy practices , such as evaluating the authority , accuracy , and relevance of information, you may

- receive poor grades in school and a loss of clients at work

- be spammed, tricked, or fooled by bad actors

- be uninformed about the best, most relevant information on a topic

- make decisions based on emotions rather than reason

- confuse fake news for real news

- make poor decisions, contrary to the decisions you would make if you had engaged in strategic searching .

By using critical perspectives when consuming, evaluating, or producing information, people develop competencies that have been conceptualized as “a basic human right in a digital world” (Alexandria Proclamation 2005).

What Competencies are Associated with Information Literacy?

Information Literacy refers to a cluster of competencies, including the ability

- to recognize when you need information

- to understand the type of information you need

- to know how to search for information

- to know how to interpret information and distinguish fact from opinion, textual debate over empirical observation

- to know how to engage in the research methods sanctioned by your target audience

- to know how to use and cite information

- to know how to remediate texts in new media .

Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education

Acrl frameworks (aka threshold concepts) for information literacy.

In Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education , the ACRL imagines six critical frameworks, aka mindsets, that inform clear and persuasive acts of communication:

- Authority is Constructed & Contextual

- Information Creation as a Process

- Information Has Value

- Research as Inquiry

- Scholarship as a Conversation

- Searching as Strategic Exploration

Related Resources

- Project Information Literacy: http://www.projectinfolit.org/

- Citation Project: http://www.citationproject.net/

- Students and their sources: http://www.citationproject.net/studies/sats/

Alexandria Proclamation on Information Literacy and Lifelong Learning, 2005. Information literacy. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/access-to-knowledge/information-literacy

Association of College and Research Libraries. “Visual Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education.” Text. Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL), October 10, 2019, http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/visualliteracy .

ACRL (Association of College and Research Libraries) (2015) Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education , http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework , 12/21/19.

CWPA 2011. Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing, http://wpacouncil.org/aws/CWPA/pt/sd/news_article/242845/_PARENT/layout_details/false, 3/3/20.

Obama, Barack (2009). “National Information Literacy Awareness Month” (PDF) .

Related Articles:

ACRL Information Literacy Perspectives & Practices

Archive – What Do Writers Need to Know About the Archive?

Authority - How to Establish Credibility in Speech & Writing

Canon - why is the concept of the canon so important to writers.

Empathetic Information Literacy

Epistemology - theories of knowledge.

Information Architecture

Information Design

Information, Data, Content - Building Blocks Of The Digital Information Age

Interpretation, Interpretative Frameworks

Textuality, intertextuality.

The CRAAP Test - Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, Purpose

Suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Joseph M. Moxley , Grace Veach

In an era where almost anything can be digitally manipulated or “spoofed,” from audio to even making visuals that deceive, you need to discern genuine sources from misleading or false...

- Joseph M. Moxley

An archive traditionally refers to a physical repository of historical documents and texts. Yet in contemporary usage, archives are perceived to be more than sources of information: they are also...

In our modern digital era, advanced editing tools have amplified the spread of misinformation, making the quest for authority and credibility in speech and writing even more important. With countless...

In contemporary usage, a canon is a collection of works, theories, research methods, or practices that are considered foundational and authoritative within a specific academic discipline, professional discipline or cultural...

- LeEtta M. Schmidt