Get 25% OFF new yearly plans in our Spring Sale

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

Narrative Nonfiction Books: Definition and Examples

Hannah Yang

Table of Contents

What is narrative nonfiction, narrative nonfiction examples, how prowritingaid can help you write narrative nonfiction.

There are countless types of nonfiction books that you can consider writing. One popular genre you might have heard of is narrative nonfiction.

So, what exactly is narrative nonfiction?

The short answer is that narrative nonfiction is any true story written in the style of a fiction novel.

Read on to learn more about what narrative nonfiction looks like as well as some examples of bestselling narrative nonfiction books.

Let’s start with a quick overview of what narrative nonfiction means.

Narrative Nonfiction Definition

Narrative nonfiction, which is also sometimes called literary nonfiction or creative nonfiction, is a subgenre of nonfiction . This subgenre includes any true story that’s written in the style of a novel.

It’s easy to understand this term if you break it down into its component parts. The first word, narrative, means story. The second word, nonfiction , means writing that’s based on fact rather than imagination.

So, if you put those two words together, it’s clear that narrative nonfiction refers to true events that are written in the style of a story.

Narrative Nonfiction Meaning

You can think of narrative nonfiction as a genre that focuses both on conveying the truth and on telling a good story.

Everything in a narrative nonfiction book should be an accurate portrayal of true events. However, those events are told using techniques that are often used in fiction.

For example, narrative nonfiction writers might consider writing craft elements such as plot structure, character development, and effective world-building to craft a compelling story.

Most narrative nonfiction books include the following elements:

A protagonist (either the author themselves or the core subject of the story)

A cast of characters (who are real people)

Immersive, fleshed-out scenes

A plot arc similar to the plot arcs found in fiction novels

Use of literary devices such as metaphors, symbols, and flashbacks

Some narrative nonfiction writers also play with more creative elements to make the story more intriguing, such as multiple POVs, alternating timelines, and even the inclusion of emails, diary entries, and text messages.

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

At the end of the day, though, narrative nonfiction is still a form of nonfiction. That means it’s important to try to be as accurate as possible.

Authors writing in this genre need extensive research skills, whether that means combing through historical records or interviewing experts. It’s impossible to create a completely accurate representation of any true story, so it’s fine to take some creative license when writing narrative nonfiction, but most authors still do as much research as they can to make sure they’re correctly depicting what happened.

Which Genres Count as Narrative Nonfiction?

It’s hard to draw a clear line around what counts as narrative nonfiction since many works of writing blur the lines between subgenres.

Two genres that commonly intersect with narrative nonfiction are memoir and autobiography, which are terms that apply when an author tells the story of their own life. When these stories are told in a narrative style, some people consider that to be narrative nonfiction or literary nonfiction, while others believe memoir and autobiography should be a separate category.

Most journalism and biographies aren’t included under the narrative nonfiction umbrella, since they usually focus more on reporting than on telling a story. Still, a form of journalism called literary journalism deliberately aims to tell personal stories in a more creative way, and there are also biographies that do the same.

Some books in other nonfiction subgenres, such as travel writing, true crime, and even food writing, can also be told in a way that resembles narrative nonfiction. In fact, more and more nonfiction books these days are using literary techniques to hook readers in.

Narrative nonfiction books can focus on just about any topic as long as they use literary styles to tell true stories. If you’re writing nonfiction, you can definitely consider incorporating literary elements to craft a compelling narrative around your topic.

The best way to understand a genre of writing is by reading examples within that genre. Here are ten of the best narrative nonfiction books to add to your reading list.

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote (1965)

Truman Capote, best known for his novella Breakfast at Tiffany’s, started out as a fiction writer. When he wrote In Cold Blood , he famously called it a “nonfiction novel,” which introduced that term into the popular consciousness for the first time.

In Cold Blood tells the story of a brutal quadruple murder that took place in 1959 in Holcomb, Kansas. The book describes the details of the murder, the ensuing investigation, and the eventual arrest of the murderers.

In many ways, In Cold Blood defined the narrative nonfiction genre. It was one of the first times an author had written journalism in the structure of a novel, and it inspired many future writers to try creative nonfiction too.

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer (1997)

Jon Krakauer is a journalist and a mountaineer who summited Mt. Everest on the day a terrible storm hit the mountain. That storm ended up claiming five lives and leaving Krakauer himself ridden with guilt.

Into Thin Air is Krakauer’s account of his adventure and its deadly aftermath. It portrays the entire cast of characters that accompanied him up the mountain and also shows the character growth Krakauer experienced as a result.

This book is a famous example of a memoir that reads like an adventure novel. The American Academy of Arts and Letters gave this book an Academy Award in Literature in 1999 and described it as combining “the finest tradition of investigative journalism with the stylish subtlety and profound insight of the born writer.”

Seabiscuit: An American Legend by Laura Hillenbrand (1999)

Seabiscuit was a California racehorse in the 1930s. Because of his crooked leg, he was never expected to win.

However, when Seabiscuit was bought by Charles Howard and ridden by a jockey named Red Pollard, he rose to unexpected success. Now, Seabiscuit is remembered as one of the most iconic racehorses of all time.

Laura Hillenbrand, an equestrian writer, tells Seabiscuit’s story in this classic work of narrative nonfiction. Charles Howard, Red Pollard, and all the other characters involved in Seabiscuit’s life are researched and portrayed in a masterful way.

Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books by Azar Nafisi (2003)

From 1995 to 1997, Nafisi led a secret book club at her house in Tehran. Every Thursday, she met with her most dedicated female student to read banned Western classics together, from Pride and Prejudice to Lolita.

In Reading Lolita in Tehran , Nafisi describes her experiences throughout the Iranian revolution. It’s a gripping book that provides rare and extraordinary insight into what it was like to be a woman in Tehran in the late 1990s.

Like all great narrative nonfiction, this book would be a compelling novel even if you didn’t know it was a true story, but the fact that it’s all true makes it even more powerful.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot (2010)

Henrietta Lacks was a Black woman whose cells were taken by medical researchers in 1951 without her knowledge or consent. Ever since then, her cells, now known as HeLa cells, have been kept alive for medical uses.

HeLa cells have been essential for researching diseases, creating the polio vaccination, and making other medical breakthroughs. And yet, her family never benefited from or consented to their use.

Rebecca Skloot’s bestselling book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks tells Lacks’ story in a thoughtful and illuminating way, weaving in research on the unjust intersection of medicine and race. The book won many awards and was later made into an HBO movie.

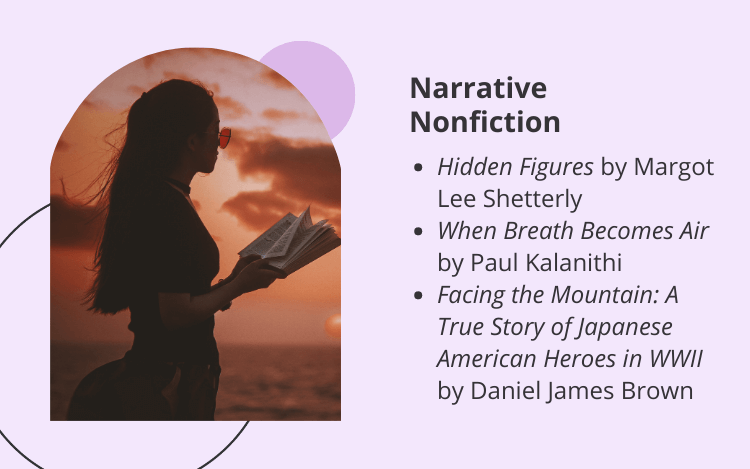

Hidden Figures by Margot Lee Shetterly (2016)

America’s achievements in space could never have happened without the contributions of Black female mathematicians at NASA, known as “human computers.” Before modern computers existed, these women used pen and paper to perform the calculations that launched rockets into space.

Shetterly’s book tells the stories of four of these brilliant women: Dorothy Vaughan, Mary Jackson, Katherine Johnson, and Christine Darden. The story follows them for over three decades as they overcame racial and gender prejudices to help shape American history.

This work of literary nonfiction is well-researched, informative, and powerful. It was also made into a major motion picture by Twentieth Century Fox.

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi (2016)

Paul Kalanithi, a Stanford neurosurgeon, was only 36 years old when he received his Stage IV lung cancer diagnosis. He went from treating patients to becoming the patient in such a short span of time that he had to quickly learn how to accept his own mortality.

Kalanithi wrote this medical memoir during the last years of his life, describing how he came to terms with his diagnosis. When Breath Becomes Air tells Kalanithi’s story in a poignant and unforgettable way.

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann (2017)

Killers of the Flower Moon is a true crime murder mystery about a terrible crime in the 1920s, when members of the Osage Indian nation in Oklahoma started getting killed one by one. Anyone who tried to investigate was in danger of getting murdered too until the death toll rose to over two dozen.

When the truth was finally uncovered, it turned out to be a chilling conspiracy bolstered by prejudice against Indigenous people.

Journalist David Grann tells the story of this shocking crime in this narrative nonfiction book, which is soon to be made into a major motion picture.

I’ll Be Gone in the Dark: One Woman’s Obsessive Search for the Golden State Killer by Michelle McNamara (2018)

The Golden State Killer was a serial killer who raped and murdered dozens of people in the 1970s and 1980s. Michelle McNamara was a true crime journalist who coined the name “Golden State Killer” in 2013 when she was poring over police records, determined to figure out the killer’s identity.

I’ll Be Gone in the Dark, which was still in the process of being written when McNamara died, blurs the genres between nonfiction, memoir, and crime fiction. The book eventually helped lead to the killer’s capture.

Facing the Mountain: A True Story of Japanese American Heroes in WWII by Daniel James Brown (2021)

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Japanese Americans faced suspicion and systemic prejudice from their own country. In spite of the injustices they faced over the next several years, many Japanese Americans still signed up to fight for the US in World War II.

In Facing the Mountain , Daniel James Brown tells the stories of four Japanese American heroes: Rudy Tokiwa, Kats Miho, Gordon Hirabayashi, and Fred Shiosaki. The book follows these four men and their families and communities, who were irreversibly impacted by the events of the war.

Writing narrative nonfiction can be incredibly rewarding, but it can also be unusually tricky because you have to accomplish two goals at once. Unlike other nonfiction, which aims to inform, or most fiction, which aims to entertain, narrative nonfiction seeks to inform and entertain at the same time.

To inform, you’ll need your writing to be clear and easily readable. To entertain, you’ll need it to be gripping and active.

ProWritingAid can help with both of those goals. At the most basic level, the AI-powered grammar checker will make sure your writing is free of grammar, spelling, and punctuation mistakes. At a more sophisticated level, it will also make sure you’re hooking your reader in by using the active voice, precise word choices, and varied sentence lengths.

In addition, you can also use ProWritingAid to make sure you’re writing in the right tone and for the right reading level. Running your narrative nonfiction manuscript through ProWritingAid will ensure your writing truly shines.

There you have it—our complete guide to narrative nonfiction.

Good luck, and happy writing!

Hannah is a speculative fiction writer who loves all things strange and surreal. She holds a BA from Yale University and lives in Colorado. When she’s not busy writing, you can find her painting watercolors, playing her ukulele, or hiking in the Rockies. Follow her work on hannahyang.com or on Twitter at @hannahxyang.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Table of Contents

What is narrative writing?

- First-person versus third-person narrative

- How to get out of your own way & write

- Examples of great narrative writing

How to improve your narrative writing

What is narrative writing (& how to use it in a nonfiction book).

Narrative writing isn’t just for fiction. Not by a long shot.

In fact, the art of storytelling in written form can make or break just about any book.

Why? Because books are long . They have to hold a reader’s attention over thousands of words, and nothing holds a reader’s attention like a good story.

Well-told stories can:

- grab and hold the reader’s attention

- illustrate new ideas in an entertaining way

- help readers relate those ideas to their own lives

If you want readers to love your book, to see themselves in it, and to recommend it to other readers, chances are you’ll need to tell a few good stories.

Narrative writing is any writing that tells a story.

The story can be fiction or nonfiction. It can be a full-length memoir (or novel) that tells one long story from start to finish, or it can be a quick anecdote in the middle of a how-to book.

No matter how long or short it is, whether it’s true or made up, every story in written form is narrative writing.

But here’s the good news: you don’t have to be a professional writer to write a good story .

Whether or not you’ve ever written even one story in your life, I’d bet good money that you’ve told a few.

In fact, you probably have a whole collection of stories. About the best and worst and craziest things that ever happened to you. Stories you’ve told a hundred times or more.

Narrative writing is just storytelling that’s written down.

First-person versus third-person narrative in nonfiction

There are two basic forms of storytelling: first-person and third-person.

One isn’t any better than the other, but first-person stories are the kind most people think of when they think about storytelling.

What is first-person narrative writing?

The first-person point of view uses “I” or “we” to tell a story.

The narrator is the main character, so the story is being told by the person who lived it.

“I’m finally on the road, heading for the convention, and I’m feeling pretty good. Despite the morning from hell, I hadn’t broken my neck, I hadn’t destroyed my marriage, and by some miracle, I’d managed to leave the house just 15 minutes behind schedule.

If I skipped lunch, I could still make it in time to give the keynote address.

This is what I was thinking, mentally patting myself on the back, when I suddenly realized I’d left my lunch on the counter, back in the kitchen, dropping it there during my meltdown.

Along with my speech.”

What is third-person narrative writing?

Third-person narrative writing uses “he,” “she,” or “they” to tell a story.

In nonfiction, third-person narration is often used to illustrate a point through a short story or case study.

“It was the worst setback the company had ever faced. The market for their revolutionary plastics had dried up overnight. And, given their recent expansion, the cash in the bank could only meet their payroll for about six more weeks.

The CEO called an executive meeting. Everyone assumed she was going to lay out a plan for a global shutdown. But what she proposed instead proved to be one of the greatest operational pivots in the history of manufacturing.”

Which one is better?

Like most writing, what’s best depends on the situation.

When the main character or actor in your story is someone else, third-person narrative is the obvious choice.

This is common in business books that include case studies, or in books by investigative journalists who track down stories about other people to learn about a given topic or idea.

When you’re writing a memoir, or when you’re writing a knowledge-share book that includes stories from your own experience, first-person narrative is extremely powerful.

But you don’t need to get bogged down in this kind of literary analysis.

Whether you’re writing a personal narrative or presenting a case study, just write it.

How to get out of your own way and write

Here’s the thing: you already know how to tell a story.

Don’t make the process of writing more complicated than it has to be.

Your book might jump back and forth between different points of view depending on what story you’re telling, but that isn’t something you’ll have to think about.

If you’re writing about something that happened to you, you’ll write “I” or “we” without paying any attention to it. It’s as natural as breathing.

If you’re writing about someone else, you’ll refer to them in the third person without any conscious effort.

The advice I am about to give you goes against most conventional writing wisdom:

People are natural-born storytellers. Trust yourself to tell the stories you need to tell.

What’s far more important is to think about how to tell the story. What should you focus on? What should you leave out?

Those decisions need to happen on a case-by-case basis, and the best way to learn how to make them is to see the results of good writing and editing in action.

Examples of great narrative writing in nonfiction books

Instead of getting hung up on literary terms like first-person or third-person narrative, great Authors worry about entertaining the reader.

No matter what kind of nonfiction you’re writing, people respond to stories, especially stories that start out with a problem.

Like these first paragraphs of Tiffany Haddish’s The Last Black Unicorn.

Tiffany Haddish: The Last Black Unicorn

“School was hard for me, for lots of reasons. One was I couldn’t read until, like, ninth grade. Also I was a foster kid for most of high school, and when my mom went nuts, I had to live with my grandma. That all sucked.

I got popular in high school, but before that, I wasn’t so popular. Kids would tease me all the time in elementary and middle school. They’d say I got flies on me and I smell like onions.

The flies thing came from the moles on my face. I got one under my eye, I had one on my chin, and so on. That was kind of mean.

The onions thing was because my mom used to make eggs in the morning with onions in them. Every damn morning, I had to eat eggs and onions. That would just make you stink. The whole house would stink.

Yeah, it was mean to say I stunk like onions, but…I did stink like onions.”

Story structure: why this is great

These opening paragraphs of Tiffany Haddish’s memoir grab the reader’s attention. Understanding how and why is the first step to strong narrative writing.

1. The style is conversational

There’s nothing formal or stilted about the writing. In fact, it reads like the Author is talking directly to the reader.

That’s the first key to writing narratives: write like you’re talking to someone. In fact, don’t even think of it as writing. Think of it as storytelling.

2. It starts with a highly relatable problem

School might have been hard for different people in different ways, but we’ve all been kids. And most of us had some kind of trouble with school at some point or another.

Opening with a universal problem gives readers something to relate to personally.

3. It gets personal and vulnerable quickly

If the first line of the book presents a problem almost everyone can relate to, the second line moves like lightning into the Author’s specific experience: “I couldn’t read until, like, ninth grade.”

Sharing a vulnerable and personal experience makes the story come alive. It’s straightforward, open, and honest, and admits something that most people would be far too ashamed to admit.

A lot of great writing comes down to the simplest writing lesson of all: be brutally honest about the things that feel the most private or make you feel the most vulnerable.

That’s virtually guaranteed to grab the reader’s attention.

4. It doesn’t over-explain things

In the first few lines, the reader learns that the Author couldn’t read until the ninth grade, that she was a foster kid, and that her mother “went nuts.” But we don’t get any details about any of those things.

At least, not yet.

By not explaining them here, the Author uses those revealed facts to invite the reader deeper into the story. The explanation can come later.

5. It offers the right sensory details

At the same time, the Author does explain some things.

Specifically, she tells the reader where her tormentors’ taunts came from. Details like the stink of onions are vivid in the reader’s imagination.

But these details aren’t just sensory. They’re intensely personal, which is the toughest part of the writing process.

Even in this very short piece of writing, the Author was willing to cut deep.

6. The reader’s interest drives the organization

When they first sit down to write, a lot of Authors feel compelled to present their story in chronological order. But the actual timing of events isn’t what drives a good story.

Instead, narrative text should be driven by the reader’s interest.

In three short paragraphs, the Author jumps from high school to middle school to serve the reader. She uses these miniature flashbacks to set the scene for the whole book.

She isn’t trying to present an ordered storyline.

She’s presenting new information in the order that will best draw the reader into the story. And it works brilliantly.

David Goggins: Can’t Hurt Me

“We found hell in a beautiful neighborhood. In 1981, Williamsville offered the tastiest real estate in Buffalo, New York. Leafy and friendly, its safe streets were dotted with dainty homes filled with model citizens. Doctors, attorneys, steel plant executives, dentists, and professional football players lived there with their adoring wives and their 2.2 kids. Cars were new, roads swept, possibilities endless. We’re talking about a living, breathing American Dream. Hell was a corner on Paradise Road.

That’s where we lived in a two-story, four-bedroom, white wooden home with four square pillars framing a front porch that led to the widest, greenest lawn in Williamsville. We had a vegetable garden out back and a two-car garage stocked with a 1962 Rolls Royce Silver Cloud, a 1980 Mercedes 450 SLC, and, in the driveway, a sparkling new 1981 black Corvette. Everyone on Paradise Road lived near the top of the food chain, and based on appearances, most of our neighbors thought that we, the so-called happy, well-adjusted Goggins family, were the tip of that spear. But glossy surfaces reflect much more than they reveal.”

Although the paragraph structure here is more like a narrative essay than a casual conversation, the writing skills are just as obvious.

1. It starts with a personal problem

Here, again, the very first line presents a problem. By using the first-person “we,” the Author makes the problem personal.

But, in this case, what draws the reader in isn’t relatability but curiosity about the unexpected.

“We found hell in a beautiful neighborhood.”

The juxtaposition between hell and a beautiful, presumably peaceful neighborhood catches the reader’s attention and holds their interest, making them want to know more.

2. It presents a powerful conflict

The opening line mentions hell. Then several sentences describe a beautiful neighborhood, but the paragraph ends with hell again.

One of the most basic facts about stories is that readers need conflict to stay interested.

Paradise, in and of itself, is boring.

Why? Because the human brain was built to solve problems. When we find one, we latch onto it.

Here, the Author paints the picture of an affluent American neighborhood but continues to touch on the idea of finding hell there, creating tension through foreshadowing.

“But glossy surfaces reflect much more than they reveal.”

3. It paints a picture with details

The Author could have simply said it was a wealthy neighborhood, but the writing paints a more vivid image by using just the right level of detail.

“Doctors, attorneys, steel plant executives, dentists, and professional football players lived there with their adoring wives and their 2.2 kids.”

By listing specific professions, the Author brings the street alive. These are real people.

At the same time, he shows the reader the facade they’re all hiding behind by using the phrase “2.2 kids.” There’s no such thing as two-tenths of a kid. The street is both real and fake at the same time.

Which is exactly the Author’s point, without having to say it directly.

The art of good storytelling is important, but you can’t get hung up on it while you’re trying to write your first draft.

Just write your book. And be as honest as you can while you’re doing it.

I can’t stress that enough.

All great books move through several rounds of editing before they’re published . They don’t come out looking perfect in the first round.

But the core value of a good book comes from being true to yourself when you’re writing it.

So, don’t worry about your writing style or choosing the right sensory details or any of that when you’re writing your rough draft.

Just get your truth down on the page.

Once your draft is finished, the polish comes in the editing . Hire a great editor , and trust them.

They’ll help you hone that draft until it grabs the reader’s attention and holds it until the end.

The Scribe Crew

Read this next.

How to Choose the Best Book Ghostwriting Package for Your Book

How to Choose the Best Ghostwriting Company for Your Nonfiction Book

How to Choose a Financial Book Ghostwriter

What is Narrative Nonfiction?

Narrative nonfiction infuses true-life accounts with the storytelling techniques of your favorite fictional narratives. From mind-boggling scientific odysseys and eye-opening historical reports to nerve-jangling true crime investigations, the genre has something for everyone. But what is narrative nonfiction, and how is it different from other literary genres? Buckle up as we journey into the history and controversies of narrative nonfiction, where we’ll discover some captivating reads that are anything but dull.

What Is Narrative Nonfiction?

Sometimes referred to as literary nonfiction or creative nonfiction, narrative nonfiction draws on the literary methods of fiction writing to present well-researched information. It’s a flexible term that can be applied to various works and styles, including memoir , history , investigative journalism , current affairs , and scientific accounts. What sets the genre apart from more traditional nonfiction is that narrative nonfiction aims to entertain as much as inform by building a compelling story around its central subject.

As such, some of the most popular narrative nonfiction books center on groundbreaking discoveries, ripped-from-the-headlines investigations, or major historical events. Recent examples include Paul Kix’s You Have to Be Prepared to Die Before You Can Begin to Live , which chronicles a crucial moment in the Civil Rights Movement, and Elon Green’s Edgar Award–winning true crime book Last Call , which examines a harrowing murder case from 1980s and ’90s New York. Narrative nonfiction also excels at telling quieter human stories that connect to deep social issues. One such example is Brothers on Three by journalist Abe Streep. The award-winning nonfiction book follows a group of young basketball players from Montana’s Flathead Indian Reservation as they embark on their final year of high school. What begins as a seemingly straightforward sports book about a championship season soon blossoms into a moving examination of identity, community, and growing up under the weight of generational trauma.

The appeal of narrative nonfiction is that it invites us to learn about real-life people and events in a way that’s both edifying and enthralling. By enhancing factual accounts with literary techniques like world-building, character development, rising action, and compelling dialogue, authors of narrative nonfiction connect with their readers on multiple levels — and, ideally, help them gain a more thorough understanding of the topic at hand. The key, of course, is applying these narrative enhancements without damaging factual accuracy.

What Are the Origins of Narrative Nonfiction?

Perhaps you noticed that a number of the authors mentioned thus far are journalists . In fact, the origins of narrative nonfiction can be traced back to the New Journalism movement of the 1960s, which sought to infuse nonfiction reporting with literary sensibilities. Traditional journalism typically featured reporters who delivered the news with impartial authority. New Journalists, in contrast, saw personal transparency, subjective reporting, and uniqueness of voice as keys to capturing a moment and connecting with an audience. Leaders of the New Journalism movement included Tom Wolfe, Truman Capote , Joan Didion , Hunter S. Thompson , and Norman Mailer . While their works differed in tone and format — for instance, Tom Wolfe’s Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test and Norman Mailer’s Armies of the Night tended toward novelistic memoir, while Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood was an innovative true crime book — they all pushed back at the notion that neutrality was necessary for impactful and effective journalism.

Are There Controversies About Narrative Nonfiction?

When you test the limits of nonfiction, you inevitably run into thorny issues about the truth. After all, how much creative license are you allowed to take before your true-life account crosses into fiction? As a result, narrative nonfiction has had its share of controversies. Throughout his career, Capote faced questioning about the veracity of certain scenes and dialogue from In Cold Blood. Janet Malcolm, an author and a New Yorker journalist who frequently explored issues of journalistic objectivity in her work, was sued for libel by a subject of her 1984 book In the Freud Archives . She later provoked debate in 1990 with The Journalist and the Murderer, which delves into the ethics of journalism and the troubled relationship between an author and their subject. Perhaps the most high-profile narrative nonfiction controversy centers on James Frey’s 2003 book A Million Little Pieces . While the work was marketed as a memoir, it was later revealed to contain multiple alterations and outright fabrications . The revelation sparked a heated conversation over what constitutes a memoir and led to a notoriously tense interview with Oprah Winfrey just weeks after she had picked the book for her book club.

What Are Some Different Styles of Narrative Nonfiction?

As discussed, narrative nonfiction covers an array of subjects, styles, and authorial positions. Here are just a few of the most popular subgenres of narrative nonfiction.

Historical Nonfiction

Historical nonfiction books investigate the chapters of the past from a lively perspective, bringing yesteryear to life and often drawing parallels to present-day events. Popular works include In the Garden of Beasts by Erik Larson and Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns, an award-winning account of Black migration in America. Another excellent example of historical nonfiction is You Have to Be Prepared to Die Before You Can Begin to Live by journalist Paul Kix. In it, Kix vividly chronicles Project C, the 10-week 1963 Civil Rights campaign to desegregate Birmingham, Alabama, that was led by Martin Luther King, Jr., Wyatt Walker, Fred Shuttlesworth, and James Bevel. Kix’s gripping prose and fine eye for detail transport readers back to this crucial moment in history, guiding us through the campaign and tracing a clear line from the events of 1963 to today’s continuing fight against discrimination and racial inequality .

True crime is a popular literary genre that traces back through history but reached a new level of readership with the 1966 publication of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood . The influential work centers on the 1959 murder of the Clutter family in Kansas. Capote spent years researching the murders, gathering accounts from locals, and interviewing the convicted killers before crafting his account. The resulting narrative was a national bestseller that read more like a novel than a work of reporting — indeed, Capote himself viewed In Cold Blood as a “ nonfiction novel .” Today it stands as a landmark of true crime and narrative nonfiction. A modern-day example of exceptional true crime is Elon Green’s Last Call : A True Story of Love, Lust, and Murder in Queer New York . The Edgar Award–winning book examines the lesser-known case of the Last Call Killer, a serial murderer who targeted gay men in New York City in the 1980s and ’90s, at the height of the AIDS epidemic. Green’s book not only recounts the investigation but condemns the entrenched intolerance that allowed these killings to go overlooked for years, and it champions the strength of the gay community in the face of violence, persecution, and sustained social ostracization.

Investigative Journalism

In many ways, investigative journalism is an ideal form of narrative nonfiction: Each account examines a harrowing real-life event from a deeply personal perspective, often with the journalist at the center of their own story. All the President’s Men by Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward is a seminal work. More recent examples include Beth Macy’s Dopesick, which examines the opioid crisis in America, and She Said by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, which recounts the sexual harassment investigation that sparked the #MeToo reckoning. In Bad City: Peril and Power in the City of Angels , Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Paul Pringle combines investigative reporting with personal narrative to compelling effect. The nonfiction thriller takes readers along for the ride as Pringle and his colleagues at the L.A. Times unearth a web of criminality at the University of Southern California and root out corruption across Los Angeles. Rather than writing an impartial report, Pringle chronicles the investigation from his perspective, beat by beat. As a result, Bad City reads like a noir novel come to life, merging true crime and investigative reporting with the shocking twists of an L.A. mystery .

We’ve only just begun to scratch the surface of narrative nonfiction, and there’s a vast world to explore. Whether you’re looking to dive deep into the past, learn about scientific breakthroughs, or lose yourself in a true-life story, there’s a perfect nonfiction book out there that will open your eyes and keep you enthralled until the last page is turned.

Share with your friends

Related articles.

13 Dark and Twisted Murder Mystery Books

11 Remarkable Books About Productivity That Everyone Should Read

13 New Queer Novels We Can't Wait to Read in 2024

Celadon delivered.

Subscribe to get articles about writing, adding to your TBR pile, and simply content we feel is worth sharing. And yes, also sign up to be the first to hear about giveaways, our acquisitions, and exclusives!

" * " indicates required fields

Connect with

Sign up for our newsletter to see book giveaways, news, and more.

What is Narrative Nonfiction? Meaning and Types

This post may contains affiliate links. If you click and buy we may make a commission, at no additional charge to you. Please see our disclosure policy for more details.

Have you heard about the term Narrative Nonfiction? This form of writing is popular among readers.

Narrative nonfiction brings life to true stories by inducing the element of fiction to make it more exciting and engaging. When a real-life story is told with a proper plotline, dialogues, and added suspense, it becomes all the more interesting!

In this article, I have explained the concept of narrative fiction in detail, along with recommending some books under the category. Want to learn more about the topic? Then stay with me throughout the article!

Table of Contents

What is Narrative Nonfiction?

Before stating the meaning of narrative nonfiction , let me briefly describe what fiction and nonfiction are. Fiction is a type of writing based on a person’s imagination, whereas nonfiction is based on facts and features.

Narrative nonfiction is a type of nonfiction writing where a story is written based on facts, information, and true events, but it is written in the style of a fiction novel, inducing entertainment, suspense, character development, and more to make it interesting and engaging for the readers.

Creative nonfiction and literary nonfiction are other terms that can be used instead of narrative nonfiction. In short, it means incorporating literary styles and techniques to tell a true story.

In this kind of writing, a balance must be maintained between imagination and ethical behavior so that the content remains true throughout. A blend of accurate information and entertainment!

Types of Narrative Nonfiction

If we talk about the types of narrative nonfiction, then there are two categories they can be divided into: Media and Novels.

Modern Media

Nowadays, the media sector is also using narrative nonfiction writing. Whether it be publishing news articles, magazines, podcasts, etc., fact-based storytelling is taking its place everywhere. The difference between both styles of writing is a blur.

Modern Books

Many authors are incorporating fictional methods into nonfiction writings to make the books engaging.

Writing true factual information using elements such as plot, dialogues, mystery , and scenes is a new way to narrate the stories, known as narrative nonfiction.

What Makes Narrative Nonfiction Writing Good?

It is essential to understand the basic elements to make a narrative nonfiction writing good. You need to know a few major aspects before diving into this category. I have mentioned some points below for you to check out!

Research is a very important step in the writing process. Every type of writing requires thorough research, and every writer, regardless of the genre and category in which they are writing, has to do research beforehand.

Narrative nonfiction is a combination of fiction and nonfiction, so with the storytelling element, it should also be informative.

The factual information should be gathered through interviews, diary entries, newspaper articles, historical reports, etc., in order for the data to be accurate and reliable.

So, the writers should ensure conducting proper research, developing an understanding of the topic, and fact-checking everything before putting the data in writing.

Balance Between Fact and Fiction

While writing narrative nonfiction, it is essential to understand how much fact and fiction can be included to maintain the overall balance.

This kind of writing uses literary styles and techniques to make the story interesting, along with stating the facts and information accurately.

But it is tough to represent every detail of an event that happened long ago with complete accuracy and reliability until and unless you have records and sources for everything.

So, in these situations, authors use conjecture in the narratives to fill the gap and maintain the flow.

As a writer, ensure to maintain the balance between fact and fiction so the story is entertaining without losing the essence of truth. Also, while using conjecture, keep it subtle and informed so it does not sound like a true statement.

Author Presence

It is important to have an individual perspective within the story so it feels authentic to the readers. In narrative nonfiction, the presence of a strong authorial voice is less, but it must be subtly present throughout to drive the story.

In the stories, there are a lot of interviews, original research, reports, etc., so the readers may feel the lack of narration, but including the author’s perspective in several areas makes them a part of the story.

Writers should keep in mind to involve their voice in the story so the readers can connect with it more and understand the motive and thoughts behind the actual work.

High Quality

The quality of writing plays a vital role in narrative nonfiction. As a writer, you cannot state the facts directly without adding other elements because it will make the story bland.

Narrative nonfiction needs the elements of fiction, plot, dialogues, suspense, etc. so that readers can find it entertaining to read. Using various writing styles and techniques is essential to enhance the quality of the writing.

You can be playful, switch timelines, change perspective, make it intriguing, and add mystery to make the story overall a worthy read.

Some Narrative Nonfiction Books to Read 2024

There are several good narrative nonfiction books to read, and I have added three books below. You can have a look!

- The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder by David Grann

- In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

- Friday Night Lights by H.G. Bissinger

Brief Descriptions of the Nonfiction Books

The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder

In 1740, the British vessel called Wager left England on a secret mission during the war but was wrecked on an island. After suffering months of starvation, the men on the ship built a craft and sailed for over a hundred days; finally, thirty men reached the coast of Brazil. These men had tales to tell and were greeted as heroes.

Six months later, another group arrived who had a very different tale of the past. They claimed the other group as mutineers, not heroes. Both groups accused each other, and the fight carried on. A court-martial revealed a shocking truth.

The author has incredibly narrated this incident.

In Cold Blood

This narrative nonfiction book narrates the incident of November 15, 1959, where members of the Clutter family who lived in Holcomb, Kansas, were brutally murdered. They were killed by a shotgun held a few inches away from their faces.

A real-life cold-blooded murder mystery . The author reconstructs the murder case and the entire investigation that led to the final execution of the culprits.

Friday Night Lights

This is a classic story of a high school football team. Permian Panthers of Odessa is the best high school football team in the history of Texas. Friday Night plays of the Panthers from September to December were known to be a big deal.

The author narrates a season in the life of Odessa and shows the devotion of the community toward the team.

Nonfiction lovers should know the various types of this category to differentiate and pick their reads. Lately, this form of writing is preferred by many. I hope this article clarifies the concept of narrative nonfiction.

Do you like to read narrative nonfiction books? Which is your favorite?

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

- About Children’s Book Insider

- Why This Site? Why Now? Behind Our New Mission.

- Literacy Matters

- Social Action

- Anti-Harassment Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- FREE Beginner Guide

- FREE Writing Courses

- Essential Webinars

- Kidlit Social Replays

- Just for Beginners

- Notes on the Revolution

- The Craft of Writing for Children

- Creating & Publishing Children’s eBooks

- Creating Your Own Book App

- Marketing Your Book, App or eBook

- Self-Published Physical Books

- Your Personal Journey to Success

- Subscribe Now

Narrative Nonfiction: Making Facts into a Story

When editors say they are looking for narrative nonfiction, what does that mean?

Narrative nonfiction is creative nonfiction yet while both are fact-based book categories , narrative nonfiction is also about storytelling, not just presenting facts in a clever way. It gives people, places and events meaning and emotional content – without making anything up. If you make up dialog or alter facts, then it becomes fiction.

The primary goal of the narrative nonfiction writer is to communicate information, like a reporter, but to shape it in a way that reads like fiction.

So how do you do that?

✏️ Set the tone with opening images or word usage or even a juicy quote. My book, An Eye for Color , starts out: “Josef Albers saw art in the simplest things.” I wanted to set the tone that this story was about art, but simple art that kids could relate to. As the story unfolded, I connected to that idea of keeping it simple.

✏️ Voice . When writing narrative nonfiction, avoid the dull, droning textbook voice that makes you feel like you’re reading a reference book. Perky, fast-paced and humorous works better to capture your reader right from the start.

✏️ Don’t give away the point you’re trying to make, build up to it . Use obstacles and rising stakes. Ask yourself, if this thing doesn’t happen, then what?

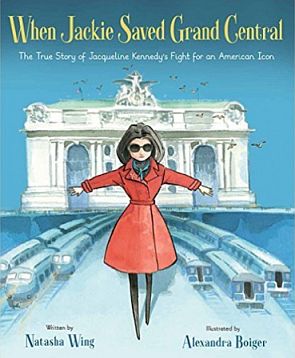

✏️ Use poetic language rather than dry statements . Using my new biography, When Jackie Saved Grand Central , as an example, I wanted to say that Jackie was mad and she wanted to join the protestors so I wrote: “Like a powerful locomotive, Jackie led the charge to preserve the landmark she and New York City loved.” This language ties into the train theme.

✏️ Use active verbs! Trim out phrases like: decided to. For example, She decided to build another model. Change to: She built another model.

✏️ Build your world or era. But do it quickly! Don’t spend a lot of opening text on setting up the year, the location, or the era. Here’s how the Jackie story starts out: “When Jackie became First Lady of the United States in 1961, she moved into the White House with President John F. Kennedy and their children.” Nuff said. I didn’t have to tell you when Jackie was born, or how many kids she had and their names, or what number president John Kennedy was, or that the White House was in Washington, D.C.

✏️ Find tension . Like all books, narrative nonfiction requires tension and conflict to grab a reader. Does your main character have a competitor who is trying to beat your guy to the patent office? Is the event something that could change the world? Is the main character full of doubt which could sabotage everything?

✏️ Find “aha” moments . Did your character have a breakthrough on her invention? Did the artist discover something he’d never seen before in his paintings that made him follow a new path? Did your character get an idea while observing ladybugs that helped solve his problem?

✏️ Is there an emotional journey for the main character? How does she succeed or grow? This works great for narrative nonfiction inventor stories. Why did the person want to invent something in the first place? Did he have a sick mother? Was a machine too cumbersome? During his journey did he ever want to give up? Did he have a breakthrough, or a break down? Did he get the recognition he wanted, or choose to live alone in a cabin instead?

✏️ Is there a kid-friendly or universal theme? Historic preservation is a tough theme to sell to younger kids, so I had to make it about saving buildings people love to use rather than pontificating about the value of restoring the architectural integrity of a landmark. See the difference?

✏️ Make us care about the person or object or invention . In my Jackie book, the biggest breakthrough in my revisions came when I started looking at the object that Jackie was trying to save – Grand Central Terminal – as something people cared about. Rather than just describing the building, I showed examples where people attended dances there, where politicians gave speeches, and friends met for lunch. That way the reader could have an emotional attachment to the building and therefore care if it was going to be destroyed or not.

✏️ Limit use of facts . This sounds odd when you’re writing narrative nonfiction, but too many facts can drag down the poetic flow of the text. Choose the facts that support your theme or opinion about the topic. Interesting nuggets that are visual or help children relate to the topic are keepers.

And don’t pile them up in one giant paragraph. Sprinkle them throughout the story, and use quotes to break up stretches of text. Visually, quotes give the eye something different to see, therefore re-investing the reader in your story.

If you still think some facts are pertinent, put them in the endnotes instead.

When you’re writing narrative nonfiction, always keep in mind, is it kid friendly and am I telling a story? Then weave those facts into your story so that readers will learn while also being entertained.

Before you start writing your narrative nonfiction manuscript keep these things in mind:

🔸 How can you connect kids to your topic? For example, how does an invention affect their lives today?

🔸 Does your story have an unusual slant?

🔸 Is your biography of someone not heard about or someone kids should know about?

🔸 Check to see what other books have been done on that topic and how the author treated the telling and incorporated the information. Check out their sidebars and endnotes, too.

🔸 Is yours different and fresh?

🔸 Has new information come out on that topic to warrant a new book? Such as when a new president is elected. Or a new technology invented. How does this new bit of information make what’s out there obsolete – the topic could use a freshening up.

🔸 Has the publisher you work with already published that topic? Then don’t submit to them.

🔸 Did you publish a chapter book on a topic that would make a good picture book? If so, choose one through line and simplify and use poetic language. Choose one thing the person did and focus on that.

🔸 Is there an anniversary coming up in 4-5 years that you can hook your topic to? Start gathering research now.

🔸 Make sure you document where every fact is from so you can easily find it when you need to revise with an editor, or when you need proof where you got a quote.

🔸 Keep a list of experts you contacted so they can vet your manuscript before you submit it.

Natasha Wing is a best-selling author who has been writing for 25 years. She is best known for her Night Before series, but also has written several narrative nonfictions. When Jackie Saved Grand Central: The True Story of Jacqueline Kennedy’s Fight for an American Icon (HMH Books for Young Readers) received starred reviews from Booklist and Kirkus .

✏ Word Counts & Age Groups for Every Kidlit Category

✏ FAQs, Glossaries and Reading Lists

✏ Category-specific Tips, from Picture Books Through Young Adult Novels

✏ 5 Easy Ways to Improve Your Manuscript

✏ Writing For Magazines …and more!

This is a gift from the editors of Children’s Book Insider, and there’s no cost or obligation of any kind.

We will never spam you or share your personal information with anyone. Promise!

More to Explore!

June 18th by Guest Author

I love the suggestion to limit use of facts! It’s really true, but we as writers are often compelled to include every little detail in a story when most of them are irrelevant (though it’s difficult to see that sometimes without the help of a good editor). Great tips here!

Learning from experience can’t be beat! Experience is the best “teacher” in the world…no matter if it’s not YOUR personal experience. Listen, observe, learn…just keep your “mouth closed,, eyes, ears and mind OPEN!” Thank You, Thank You, Thank You…for sharing your priceless list of advice to others less “bruised from the rough road traveled on the interstate of writing. Best Regards, “Cartoon Bill” Crowley PS: Brief background: I’m an artist / cartoonist and have illustrated my share of mostly Children’s books and truly love doing so. Yes, I’ve written my own children’ book…but…have re-written and re-written it several times. The illustrations are all in my head screaming and screaming “Let me out! Let me out!!!” For sure, they will be “let out’ some time in 2018. Count of it! My story has the “Judy Seal of Approval” ( my wife) …and she is NOT a “Yes” person.If it’s bad, she says so, and likewise on the affirmative side of the equation…the best type of person to have as a partner, for sure!! Thank You Again, “Cartoon Bill” Crowley.

Natasha….this is a goldmine of info and recommendations…..wow! Can’t wait to share. I think many of the action items you listed also will help with my songwriting. Congratulations to all involved in this interesting and beautiful book.

Search the Site

Get in touch.

Copyright © Children's Book Insider, LLC. All rights reserved.

Privacy Overview

- More Networks

How to Master Narrative Nonfiction – A Guide to Telling Great True Stories

by Harry Wallett

Do you have an incredible true story but are unsure how to tell it? Indeed, personal accounts can be difficult to write if they’re too personal. So, consider the approach of narrative nonfiction writers who reveal their true stories through the devices relied on by fiction writers.

There are undoubtedly many ways to tell personal stories – you might choose to stick directly to the facts and give a straightforward account of the real-life events leading to the story’s climax. Or you might consider a more creative approach to bringing your story to life.

This article is about narrative nonfiction and literary techniques you might consider borrowing from fiction storytelling. We’ll share some great examples of narrative nonfiction encompassing true crime, travel writing, and serial killer tales that have contributed to this increasingly popular genre.

What is the definition of narrative nonfiction?

Narrative nonfiction is often referred to as literary nonfiction or creative nonfiction, and these terms are used to describe true stories written in the typical style of a fiction novel.

Some narrative nonfiction examples:

- Seabiscuit: An American Legend by Laura Hillenbrand – the story of a real-life racehorse and its rise to success during World War II.

- The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot – written through intense research of interview and meeting transcripts, photos, and notes from a real-world event.

- In Cold Blood by Truman Capote – attributed as the piece that changed literary journalism, using true crime events with fiction storytelling techniques. One man’s journey into the depths of crime and its consequences.

Narrative nonfiction writers aim to take the facts of true events and compellingly tell them – in the way that fiction writers make creative choices about how they reveal revelations and plot points.

And while there’s an emphasis on storytelling, the best narrative nonfiction books rely on the truth as much as possible.

What Is the Difference Between Nonfiction Narratives and Memoir?

Good question!

While memoir and narrative nonfiction aim for factually accurate storytelling, there are some significant differences in the mediums.

What is a memoir?

A memoir uses a first-person narrator regaling personal stories, seeking the emotional truth. Memoir writers examine and re-evaluate the events of their lives rather than simply retell the story parrot-fashion.

And while memoir usually tells a story with a linear narrative (in order of the events as they happened), the medium is most interesting when the writer views their own experiences through a critical lens.

This provides the reader with a deeper understanding of the writer’s motivations, driving the success or failure that drives the narrative. The writer might identify significant moments in the story, reflecting on how things could have been if they hadn’t made a particular decision.

What is narrative nonfiction?

Narrative nonfiction is similar to memoir in that it’s a true story written to convey real events, but it uses significant creative license in the telling. Stylistically, narrative nonfiction is closer to a fictional novel.

Narrative nonfiction requires a lot of research as the writer needs to understand every angle of the characters’ motivations and objectives within the prism of the specific world of the story.

Factual and well researched

A narrative nonfiction writer will use extensive research techniques, such as:

- Extensive interviews – exploring the story from every possible angle through the people who were there

- Newspaper articles and news reports – helping the writer understand the popular interpretation or events

- Geological history – recognizing the significance of location in a historical context

- Personal essays or journals – analyzing first-person accounts from the protagonists and central characters of the action

Which techniques do narrative nonfiction books borrow from literary fiction?

A remarkable fictional novel has great characters with clear objectives, a problem that leads to a crisis, and a confrontation that leads to a resolution. And narrative nonfiction books rely heavily on these tropes to regale a true story in an exciting way.

Let’s look at those in a little more detail:

Narrative nonfiction needs fascinating characters

The narrative nonfiction writer gathers personal experience from the principal “characters” in the story. They seek out the truth and make creative decisions regarding the details of the characters’ pasts that may have contributed to their significant actions in the true story.

A compelling character has:

- An objective – something they want that they believe will help solve the problem of the world

- A redemption arc – something in the past that haunts them and drives them to redeem themselves

- A fatal flaw – something that threatens their ultimate success (some kind of self-destructive behavior, such as addiction or poor life choices)

Narrative nonfiction needs a problem, a crisis, and a confrontation

In creative fiction, a character is nothing without a problem to overcome. In great novels, the problem of the world is almost insurmountable – it requires the protagonist to go on a journey of self-discovery to overcome the obstacles holding them back from self-actualization.

What is the structure of narrative nonfiction books?

In a literary fiction novel, the problem of the world drives the character’s objective, and this kickstarts our storyline structure.

The second part of the story is where the protagonist pursues their objective and achieves it, but this turns the problem into a crisis because the pursuit didn’t solve it.

So, the story’s third section forces the protagonist to confront the problem head-on. But they often fail, or the problem becomes too complicated to overcome. Typically, they hit the reverse climax (or their low point) at this stage.

And that low point drives the protagonist to make the final confrontation in the fourth section of the story, truly addressing the problem holding them back at the novel’s beginning.

Of course, in real life, stories don’t always have a happy ending, so the fourth section – the confrontation – can equally result in failure as success.

And the narrative nonfiction genre is most successful when the writer considers these storytelling elements.

Some great narrative nonfiction books for you to read

Some of your best learning as a writer comes from your dedication to reading. So, it’s always helpful to be well-read in the creative genre you seek to pursue. I think these books find the right balance between fact and fiction.

The right balance between fact and fiction

If you’re new to the narrative nonfiction genre, check out our top recommendations:

Best-selling books to read

Hidden figures by margot lee shetterly .

You might have seen the 2016 movie starring Octavia Spencer, Janelle Monáe, and Kevin Costner, about the team of brilliant black women who significantly contributed to launching the first rockets into space.

This story has it all:

- An insurmountable world problem.

- Clear-cut objectives of the principal characters.

- Intense obstacles to overcome.

- A compelling story that drives you all the way through to the end.

A brilliant read.

My Friend Anna by Rachel DeLoache Williams

A narrative nonfiction book that has inspired a compelling podcast and a Netflix series about Anna Delvey, who swindled her way into the New York art scene, leaving a string of huge debts in her wake.

This story is driven by a compelling narrative that effectively shines a light on the capitalistic greed that has shaped American history.

Travelling to Infinity by Jane Hawking

This is the nonfiction narrative that inspired the 2014 movie, The Theory of Everything . We follow fascinating and somewhat eccentric characters as we explore the devastating personal life of world-famous British scientist Stephen Hawking, told from the perspective of his wife, Jane Hawking.

An emotional journey that keeps you hooked to the end.

True stories to engage and educate middle-grade readers

You’re never too young to adopt the narrative nonfiction writing style. Check out some of our recommendations for literary works that rely on stories that explore personal experiences, high-school football, the plight of African Americans, and the American dream.

Check out these collections of short stories and full-length narrative nonfiction books:

- Mud, Sweat and Tears by Bear Grylls

- The Elephant Whisperer by Lawrence Anthony

- The Acclaimed Biography of Sean Smith by JK Rowling

- Children of the Blitz by Robert Westall

- Alma’s Suitcase by Karen Levine

- Nothing is Impossible by Christopher Reeve

- If Only They Could Talk by James Herriot

- The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

- The Last Rhinos by Rose Humphreys

Want to Learn More About Writing Narrative nonfiction?

Check out Cascadia’s blog for tons of helpful articles that help develop your skills in writing narrative nonfiction books with high-quality narratives.

We help ambitious people who want to kickstart their book careers, helping time-pressed people connect with reputable publishing professionals.

Find out more about Cascadia here .

Harry Wallett is the Managing Director of Cascadia Author Services. He has a decade of experience as the Founder and Managing Director of Relay Publishing, which has sold over 3 million copies of books in all genres for its authors, and looks after a team of 50+ industry professionals working across the world.

Harry is inspired by the process of book creation and is passionate about the stories and characters behind the prose. He loves working with the writers and has shepherded 1000s of titles to publication over the years. He knows first-hand what it takes to not only create an unputdownable book, but also how to get it into the hands of the right readers for success.

Books are still one of the most powerful mediums to communicate ideas and establish indisputable authority in a field, boosting your reach and stature. But publishing isn’t a quick and easy process—nor should it be, or everyone would do it!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Same Cascadia, New Management!

Protected: Publishing for Peace: Author Ben JS Maure Inspires Canadian Peacekeepers

Unleashing Literary Flames: Award-Winning Author TK Riggins Keeps Readers Coming Back for More with 7-Book Series

Author Ray McGinnis Reaches an International Audience with 100+ Interviews in 2 Years

Get our free definitive guide to creating a nonfiction bestseller here.

Disabled Poets Prize

Deptford literature festival, nature nurtures, early career bursaries, criptic x spread the word, lewisham, borough of literature, what is narrative non-fiction .

The London Writers Awards focuses on four genres of prose writing: literary fiction, commercial fiction, YA/children’s fiction and narrative non-fiction. In this blog post, we explore narrative non-fiction – what it is, who it is for and the key features of this genre…

Let’s begin by breaking down the term ‘narrative non-fiction’: the first part, ‘narrative’, essentially means ‘a story’. The second : ‘non-fiction’ is widely understood as prose writing that is informative or factual, rather than fictional. Put together, ‘narrative non-fiction’ is a true story written in the style of a fiction novel.

Literary nonfiction and creative nonfiction are also terms used instead of or in association with narrative nonfiction. They all refer to the same thing – using literary techniques and styles to tell a true story. Sometimes a writer will invert the description, Janet Galloway calls her two volumes about her childhood and young adulthood ‘true novels’. Then there is ‘life writing’ that pertains to this territory and more – an inclusive term for writing that has sprung from living the life – memoir, blogs, diary, oral testimony, letters, emails autobiography; both the raw material and the shaped work. Journalism and biography on the other hand, are not included here as this generally relies on reportage… but there will always be exceptions to the rule.

T here are some key challenges in writing narrative non-fiction which we’ll explore in more detail below .

As narrative non-fiction uses literary styles and techniques, writers sometimes employ creative license to drive the story forward. This raises a lot of interesting questions about ethics but unless you have recorded every conversation and miniscule detail, it is very difficult to recreate a completely accurate representation of what actually happened. Maintaining the balance between imagination and retelling a story is personal to each writer, but every narrative nonfiction writer has a responsibility to stick to ethical behaviour throughout and to ensure the content is truthful.

Another way of looking at this approach is to think about the reader. The reader’s expectations are to be both informed and entertained. Therefore, the writer has a responsibility to accurately research the facts and details in the story so that they are presented as happened, as far as they can. For the details that they cannot remember or do not have access to, then they can inform the reader of this or drop heavy hints within the text – often stylistically – that the details here are vague or write them as close to what had actually happened. This will enable the reader to trust in the writer, and the story that they are sharing.

Another aspect of narrative nonfiction is its focus on play . This is where the distinction between this style of literature and other types of nonfiction writing – particularly memoirs, biographies and autobiographies come in. Often the latter are written from one perspective – the writer’s . Narrative nonfiction, on the other hand can switch perspectives, tenses and timelines. As a result of this, b oundaries are reinvented with chronological order being discarded in favour of telling the story in a more intriguing way.

More recently, this emphasis on play has enabled narrative nonfiction writers to cross-over into other genres – for example infusing poetry, experimental writing and elements from stage / screen writing within the text. There are no rules as to how the story can be presented, that you may expect from more traditional forms of nonfiction, such as literary journalism and diary entries. Further, books that are normally ‘one-genre’ are being infused into narrative nonfiction narratives to give them more scope and a wider readership, particularly travel writing, food writing and true crime.

As a genre, narrative non-fiction is becoming increasingly popular, with a broader readership. There are many theories as to why this may be: perhaps it is viewed as a novel approach to writing non- fiction stories, perhaps social media platforms have enabled writers to create new readerships and interest in their stories, or maybe the gatekeepers themselves have embraced this new form of writing. Regardless of this, the ability of a skilled narrative non-fiction writer to represent true stories in new ways that educates and simultaneously, entertains.

Examples of books that fit into this genre are: Colin Grant ’s ‘ Bageye at the Wheel’, which is a delightful account of a feckless father told through his son’s childhood experience of him. Maggie Nelson ’s The Argonauts is a deeply personal account of her voyage into motherhood, queer family making and identity, where she parses the contemporary iconography of motherhood, the act of writing and the limits language. Other reads that fall into this category include Truman Capote ’s In Cold Blood, Sara Baume’s handiwork, Roxane Gay ’s Hunger, Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, Azar Nafisi ’s Reading Lolita in Tehran and Paul Ka lanithi ’s When Breath Becomes Air . You can check out extensive reading lists and furt h er discussion on this topic here:

https://bookriot.com/2018/07/12/creative-nonfiction-books/

https://www.writersstore.com/creative-license-vs-creative-arrangement/

https://www.thecreativepenn.com/2017/08/17/writing-creative-non-fiction/

http://theeditorspov.blogspot.com/2012/05/fact-vs-artistic-license-in-creative.html

https://www.bookbub.com/blog/best-narrative-nonfiction-books-publishers-blurbs

Published 20 August 2020

Read the 2024 Nature Nurtures Anthology & Watch the Nature Nurtures Short Films

Announcing the winners of the lba literary agency feedback opportunity 2024, teach with us: developing tutors programme.

- Opportunities

We’re hiring: Programme and Communications Assistant

Stay in touch, join london writers network, spread the word’s e-newsletter.

Sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with Spread the Word’s news and opportunities.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Additional menu

The Creative Penn

Writing, self-publishing, book marketing, making a living with your writing

How To Write Narrative Non-Fiction With Matt Hongoltz-Hetling

posted on August 24, 2020

Podcast: Download (Duration: 1:04:14 — 52.2MB)

Subscribe: Spotify | TuneIn | RSS | More

What is narrative non-fiction and how do you write a piece so powerful it is nominated for a Pulitzer? In this interview, Matt Hongoltz-Hetling talks about his process for finding stories worth writing about and how he turns them into award-winning articles.

In the intro, I talk about Spotify (possibly) getting into audiobooks and Amazon (possibly) getting into podcasts as reported on The Hotsheet , and the New Publishing Standard . David Gaughran's How to Sell Books in 2020 ; a college student who used GPT3 to reach the top of Hacker News with an AI-generated blog post [ The Verge ]; and ALLi on Is Copyright Broken? Artificial Intelligence and Author Copyright . Plus, synchronicity in book research, and my personal podcast episode on Druids, Freemasons, and Frankenstein: The Darker Side of Bath, England (where I live!)

Matt Hongoltz-Hetling is a Pulitzer finalist and award-winning investigative journalist. He's also the author of A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear .

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript below.

- From writing for pennies an article to writing a Pulitzer – nominated article

- What is narrative non-fiction?

- How does narrative non-fiction differ from fiction?

- Where ideas come from and how to begin forming a story idea

- The necessity of being respectful of the real lives being examined and written about

- Portraying interview subjects with shades of grey

- Turning hours of source material into something coherent

- Finding the balance between story structure and meaning

- Knowing when an idea is appropriate for a book

You can find Matt Hongoltz-Hetling at matt-hongoltzhetling.com and on Twitter @hh_matt

Transcript of Interview with Matt Hongoltz-Hetling

Joanna: Matt Hongoltz-Hetling is a Pulitzer finalist and award-winning investigative journalist. He's also the author of A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear . Welcome, Matt.

Matt: Hey, thanks for having me on, Joanna.

Joanna: It's great to have you on the show.

First up, tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing.

Matt: I got into writing when I was eight years old and I wrote this amazing book. I don't want to brag, but I wrote this book about an elf that was fighting in a dungeon, and this elf had some items of a magical persuasion and used them to defeat all sorts of monsters. So, that was pretty awesome. And I've been writing stuff ever since.

I grew up knowing that I wanted to write, loving to read, all that. And then my career path never really seemed to go that way. I actually started a student newspaper when I was in college in the hopes that that would be primarily a writing occupation, but I found very quickly that it was more small business skills that were needed.

I was selling advertisements much more so than writing to fill the newspaper sadly. And so, at some point I had just got the pile of rejection slips that I think we're all familiar with. I just didn't really know how to go about getting into the industry.

I was literally writing articles for, like, 25 cents an article, these, like, ‘How do you fix an engine?' or not even an engine, nothing that complicated, but, ‘How do you clean a window?'

Joanna: Content farms.

Matt: Yes, right. Content farms. Yes. Thank you. But I was writing.

My wife encouraged me to submit an article for my local weekly newspaper in a small town in the state of Maine. And that led to me being able to write more articles, still for very small amounts, 30 bucks an article. And that led to me getting a full-time job as a journalist at a weekly newspaper in rural Maine.

And even though that was fantastically exciting for me, I always knew that I wanted to do more. And so, I was always pushing, looking for that next level that would allow me to write more of the stuff that I wanted to write. And so, that led to larger newspapers, and then magazine opportunities, and then magazine opportunities led to a book opportunity. Now, I'm happy that I am just on the cusp of publishing my first book. I'm very excited about that.

Joanna: We're going to get into that in a second, but I just wonder because this is so fascinating.

How many years was it between writing for a content farm to being a Pulitzer finalist?

Matt: That was actually the shortest journey that you can imagine. Within, let's say, two years of my first newspaper article. I wrote the article that led to my highest-profile resume point which was that Pulitzer finalist status. And that article was about substandard housing conditions in the federal Section 8 program. It's federally subsidized housing and it's meant to be kept up to a certain standard, and the article which I wrote with a writing partner demonstrated that it was not and that there were a lot of people at fault.

What really elevated that article, it was a good article and all of that, but what really got it that level of recognition was that it also turned out to be an impactful article. It happened to come at a time when other people were looking at the housing authority for various reasons. It really struck a nerve and our Senator, Republican Susan Collins of Maine, she took a very avid interest in our reporting and was motivated to encourage reforms of the national Section 8 system.

She was in a political position to do that because she held the purse strings for the housing authorities. And so, it happened to have this very disproportionate impact and because it led to a positive change for the Section 8 housing program in the United States.

I think the people in the Pulitzer committee must've loved the idea that this tiny little rural weekly newspaper where we had three reporter desks, one of which was perennially vacant, had managed to write a story that was really relevant to the national scene.

Joanna: Absolutely fascinating. And I hope that encourages people listening who might feel that they're in a place in their writing career where they're not feeling very successful and yet you bootstrapped your way up there to something really impactful, as you say.

We're going to come back to the craft of writing, but let's just define ‘narrative nonfiction.' Your book, A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear , which is a great title.

What is narrative nonfiction and where's the line between that and fiction or straight nonfiction?