Advertisement

Supported by

'1491': Vanished Americans

- Share full article

By Kevin Baker

- Oct. 9, 2005

New Revelations of the Americas

Before Columbus.

By Charles C. Mann.

Illustrated. 462 pp.

Alfred A. Knopf. $30.

MOST of us know, or think we know, what the first Europeans encountered when they began their formal invasion of the Americas in 1492: a pristine world of overwhelming natural abundance and precious few people; a hemisphere where -- save perhaps for the Aztec and Mayan civilizations of Central America and the Incan state in Peru -- human beings indeed trod lightly upon the earth. Small wonder that, right up to the present day, American Indians have usually been presented as either underachieving metahippies, tree-hugging saints or some combination of the two.

The trouble with all such stereotypes, as Charles C. Mann points out in his marvelous new book, "1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus," is that they are essentially dehumanizing. For cultural reasons of their own, Europeans and white Americans have "implicitly depicted Indians as people who never changed their environment from its original wild state. Because history is change, they were people without history."

Mann, a science journalist and co-author of four previous books on subjects ranging from aspirin to physics to the Internet, provides an important corrective -- a sweeping portrait of human life in the Americas before the arrival of Columbus. This would be a formidable task under any circumstance, and it is complicated by the fact that so much of the deep American past is embroiled in vituperative political and scientific controversies.

Nearly everything about the Indians is currently a matter of contention. There is little or no agreement about when their ancestors first came to the Americas and where they came from; how many there were, how and where they lived and why they were not more effective in resisting the European invasion. New archaeological discoveries and interpretations of Indian materials are constantly altering the historical record, and every debate comes equipped with its own bevy of archaeologists, anthropologists and other social scientists tossing around personal invective with the abandon of Rudy Giuliani on a bad day.

Mann navigates adroitly through the controversies. He approaches each in the best scientific tradition, carefully sifting the evidence, never jumping to hasty conclusions, giving everyone a fair hearing -- the experts and the amateurs; the accounts of the Indians and their conquerors. And rarely is he less than enthralling. A remarkably engaging writer, he lucidly explains the significance of everything from haplogroups to glottochronology to landraces. He offers amusing asides to some of his adventures across the hemisphere during the course of his research, but unlike so many contemporary journalists, he never lets his personal experiences overwhelm his subject.

Instead, Mann builds his story around what we want to know -- the "Frequently Asked Questions," as he heads one chapter. He moves nimbly back and forth from the earliest prehistoric humans in the Americas to the Pilgrims' first encounter with the Indian they (mistakenly) called "Squanto"; from the villages of the Amazon rain forests to Cahokia, near modern St. Louis, the sole, long-vanished city of the North American Mound Builders; from the cultivation of maize to why it was that the Incas apparently developed the wheel but never used it as anything but a child's toy.

Mann remains resolutely agnostic on some of the fiercest debates. What he is most interested in showing us is how American Indians -- like all other human beings -- were intensely involved in shaping the world they lived in. He is sure that "many though not all Indians were superbly active land managers -- they did not live lightly on the land." Just how they did live, so long uninfluenced by the vast majority of the world's population in Africa and Eurasia, forms the bulk of his fascinating narrative.

What emerges is an epic story, with a subtly altered tragedy at its heart. For all the European depredations in the Americas, the work of conquest was largely accomplished for them by their microbes, even before the white men arrived in any great numbers. The diseases brought along by the very first unwitting Spanish conquistadors, and probably by English fishermen working the New England coast, very likely triggered one of the greatest catastrophes in human history. Before the 16th century, there may have been as many as 90 million to 112 million people living in the Americas -- people who could be as different from each other "as Turks and Swedes," but who had cumulatively developed an incredible range of natural environments, from seeding the Amazon Basin with fruit trees to terracing the mountains of Peru. (Even the term "New World" may be a misnomer; it is possible that the world's first city was in South America.)

Then, disaster. According to some estimates, as much as 95 percent of the Indians may have died almost immediately on contact with various European diseases, particularly smallpox. That would have amounted to about one-fifth of the world's total population at the time, a level of destruction unequaled before or since. The exact numbers, like everything else, are in dispute, but it is clear that these plagues wreaked havoc on traditional Indian societies. European misreadings of America should not be attributed wholly to ethnic arrogance. The "savages" most of the colonists saw, without ever realizing it, were usually the traumatized, destitute survivors of ancient and intricate civilizations that had collapsed almost overnight. Even the superabundant "nature" the Europeans inherited had been largely put in place by these now absent gardeners, and had run wild only after they had ceased to cull and harvest it.

In the end, the loss to us all was incalculable. As Mann writes, "Having grown separately for millennia, the Americas were a boundless sea of novel ideas, dreams, stories, philosophies, religions, moralities, discoveries and all the other products of the mind. Few things are more sublime or characteristically human than the cross-fertilization of cultures. The simple discovery by Europe of the existence of the Americas caused an intellectual ferment. How much grander would have been the tumult if Indian societies had survived in full splendor!"

Kevin Baker is the author of the forthcoming historical novel "Strivers Row."

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

Stephen King, who has dominated horror fiction for decades , published his first novel, “Carrie,” in 1974. Margaret Atwood explains the book’s enduring appeal .

The actress Rebel Wilson, known for roles in the “Pitch Perfect” movies, gets vulnerable about her weight loss, sexuality and money in her new memoir.

“City in Ruins” is the third novel in Don Winslow’s Danny Ryan trilogy and, he says, his last book. He’s retiring in part to invest more time into political activism .

Jonathan Haidt, the social psychologist and author of “The Anxious Generation,” is “wildly optimistic” about Gen Z. Here’s why .

Do you want to be a better reader? Here’s some helpful advice to show you how to get the most out of your literary endeavor .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

'1491' Explores the Americas Before Columbus

John Ydstie

Our founding myth suggests the Americas were a lightly populated wilderness before Europeans arrived. Historian Charles C. Mann compiled evidence of a far more complex and populous pre-Columbian society. He tells John Ydstie about 1491 .

Author Charles C. Mann hide caption

More from the Interview

Settlement of the americas, inca building technologies, related npr stories, summer reading: nonfiction, excerpt: 'over the edge of the world', retracing the journey, interviews: mapping the human race's journey, a contemporary history of columbus, the chinese discovered america, author claims, read an excerpt.

Buy Featured Book

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

JOHN YDSTIE, host:

This is ALL THINGS CONSIDERED from NPR News. I'm John Ydstie.

What were the Americas like in 1491, before Columbus landed? Our founding myths suggest the hemisphere was sparsely populated mostly by nomadic tribes living lightly on the land and that the land was, for the most part, a vast wilderness. That's what most of us learned in school, along with a few paragraphs about more highly developed cultures in Central and South America. Research of the past few decades suggests, though, that the Americas were home to more people than Europe when Columbus landed and that most lived in complex, highly organized societies. In his new book titled "1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus," Charles C. Mann compiled evidence of the sophistication of pre-Columbian America. He joins us now from the studios of WFCR in Amherst, Massachusetts.

Welcome to the program.

Mr. CHARLES C. MANN (Author, "1491"): Glad to be here.

YDSTIE: Let's just quickly paint a picture of what the new evidence suggests that America looked like in 1491, what the Indian cultures looked like. And let's start in a very familiar place for Americans, for North Americans, and that is in New England, in the area of the Plymouth Colony. What kind of Indian society was there at the time?

Mr. MANN: From southern Maine down to about the Carolinas, you would have seen pretty much the entire coastline lined with farms, cleared land, interior for many miles and densely populated villages generally rounded with wooden walls. And then in the Southeast, you would have seen these priestly chiefdoms, which were centered on these large mounds, thousands and thousands of them, which still exist. And then as you went further down, you would have come across what is often called the Aztec empire and maybe better known as the Triple Alliance 'cause it was a group of three people, which was a very aggressive, expansionistic empire that had one of the world's largest cities as its capital, Tenutchtitlan, which is now Mexico City.

YDSTIE: Bigger than either London or Paris.

Mr. MANN: Oh, yeah. It was a fantastic place. The Spaniards who first saw it just couldn't believe their eyes. It was in the middle of an immense lake called Lake Texcoco with this huge, artificially constructed set of islands there surrounded by boats. It was kind of like Venice.

YDSTIE: And if you went further down into South America you would run into--on the Pacific Coast, you would run into the Inca empire.

Mr. MANN: Yes, which was probably the largest state then on Earth. If it was in Europe, it would have stretched from Stockholm to Cairo and covered every imaginable ecosystem. And then if you went further into the Amazon, there were dozens and dozens of chiefdoms culminating in a fairly large state on this gigantic island at the mouth of the Amazon comargo(ph).

YDSTIE: And the new research over the past few decades also suggests that North America was as populated as Europe.

Mr. MANN: Yeah. Because the Indians were wiped out to an extraordinary degree by disease, these diseases went ahead of the settlers. And so European colonists would come in and they would find essentially recently deserted land. And so their whole impression was of a sparsely populated area. And it's only been in the last few decades, thanks to more advanced archaeological and scientific tools, we've been able to realize exactly how many people were there before the Europeans arrived.

YDSTIE: Mm-hmm. And, in fact, if we go back up to North America and to the New England area, for instance, in the first hundred years or so after Europeans began coming to America, they really couldn't establish colonies because the area was so populated.

Mr. MANN: And the Indians, rather naturally, didn't really want these people setting up permanent camps. And so you read the early chronicles and people will make short visits and trade, and the Indians will be very hospitable. And then after a certain amount of time, a large force of armed men will show up and inform the Europeans of the limited duration of Indian hospitality, and the Europeans would shove off. And this happened again and again and again.

YDSTIE: And what changed was disease.

Mr. MANN: Yes.

YDSTIE: And so when the Pilgrims showed up, they found a devastated area or at least an empty area.

Mr. MANN: It was an emptied area, if that makes any sense. `It was a widowed land,' as one historian has called it. In fact, the first 50 settlements in New England were on deserted Indian villages. And they were deserted because all the people in them had died. And, again, if you read the Colonial accounts, they're constantly finding skeletons scattered all over the place, and they landed in a cemetery.

YDSTIE: And, of course, the sort of myth before all of this was that the Indians succumbed to the Europeans because of superior European technology, superior European political organization, maybe even superior moral character. But this whole theory of disease suggests that none of those characteristics were quite as important. And, in fact, you suggest that technologically many of the Indian cultures were just as advanced, though not in the same areas, as the European cultures.

Mr. MANN: Yeah. Take the conquest of the Inca empire, which Pizarro did with just a couple of hundred people--168 I think is the exact number--and usually that's laid to the possession of the horse and steel weaponry. But, in fact, the Inca rapidly learned how to fight the horses. And as far as the steel goes, the armor was actually an impediment. The Spaniards threw it off because the Inca armor, which was made out of this densely woven cotton, was so far superior in those conditions that these things didn't matter.

What really did matter was the appalling political shape that the empire was in from civil war and, also, that Pizarro was an extraordinary leader, and he was extremely adept at playing one faction off against the other. And this kind of thing, the traditional way that people lose, from better generalship, is what mattered, not the technology so much.

YDSTIE: Let's talk a little bit more about the technology and the technological difference. One point that you make is that European technology was sort of based on compression, compression of metal and that sort of thing, while the Indian technology was--and particularly in South America, was focused on tension and the use of fibers.

Mr. MANN: Yeah. And a perfect example of that is these bridges that the Indians had, which were suspension bridges that would go over canyons and so forth. Suspension bridges at the time didn't exist in Europe, and the Spaniards at first refused to cross these bridges because they couldn't see what was holding them up. There was nothing underneath them. And there's all these letters where they'd say, `They have these incredible bridges. And guess what? You can actually walk across them.' Again, it's just a matter of a different kind of technology.

The Inca had a very, very sophisticated metallurgy, but for their purposes, metals were most important as a means of display, for their color. And so they had all these techniques for creating these very thin alloys that could be used to coat stuff. They were able to work with types of metals that the Europeans didn't understand. Yet they didn't have steel tools. And the reason was that metal wasn't valued in that way. They valued it for its flexibility, for its plasticity rather than its hardness.

YDSTIE: Let's talk a little bit about the predecessors to the Incas. One of the things that we understand because of research of the past couple of decades is that the Incas weren't the first highly developed culture in that area; there were several predecessor cultures. And that's part of what has been the most interesting work in this new research over the last few years.

Mr. MANN: Oh, yeah. If, you know, in 2,500 or 3,000 BC you were a martian and you had wanted to land in the most sophisticated cultures on Earth, you would have had a very limited number of choices. And one of them would have been the coast of Peru, where there was a group of cities, 20 or 30 small cities, probably the biggest urban complex on Earth at that point. And this was very much at the time of Sumeria and Egypt, and this has just been discovered. The age of the cities was first established in 2001, and last year was the first publication of this survey. And essentially wherever scientists have looked in the Americas, they've seen more evidence of more people doing more things at a higher level of complexity at a much earlier time than they had believed.

YDSTIE: Charles C. Mann is the author of "1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus." Thanks very much for joining us.

Mr. MANN: It was my pleasure.

Copyright © 2005 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

- Member Login

- Library Patron Login

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR

FREE NEWSLETTERS

Search: Title Author Article Search String:

Reviews of 1491 by Charles Mann

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus

by Charles C. Mann

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' Opinion:

- History, Current Affairs and Religion

- 17th Century or Earlier

- Nature & Environment

Rate this book

About this Book

- Reading Guide

Book Summary

A groundbreaking study that radically alters our understanding of the Americas before the arrival of the Europeans in 1492. Traditionally, Americans learned in school that the ancestors of the people who inhabited the Western Hemisphere at the time of Columbus’s landing had crossed the Bering Strait twelve thousand years ago; existed mainly in small, nomadic bands; and lived so lightly on the land that the Americas was, for all practical purposes, still a vast wilderness. But as Charles C. Mann now makes clear, archaeologists and anthropologists have spent the last thirty years proving these and many other long-held assumptions wrong. In a book that startles and persuades, Mann reveals how a new generation of researchers equipped with novel scientific techniques came to previously unheard-of conclusions. Among them:

- In 1491 there were probably more people living in the Americas than in Europe.

- Certain cities–such as Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital–were far greater in population than any contemporary European city. Furthermore, Tenochtitlán, unlike any capital in Europe at that time, had running water, beautiful botanical gardens, and immaculately clean streets.

- The earliest cities in the Western Hemisphere were thriving before the Egyptians built the great pyramids.

- Pre-Columbian Indians in Mexico developed corn by a breeding process so sophisticated that the journal Science recently described it as "man’s first, and perhaps the greatest, feat of genetic engineering."

- Amazonian Indians learned how to farm the rain forest without destroying it–a process scientists are studying today in the hope of regaining this lost knowledge.

- Native Americans transformed their land so completely that Europeans arrived in a hemisphere already massively "landscaped" by human beings.

Mann sheds clarifying light on the methods used to arrive at these new visions of the pre-Columbian Americas and how they have affected our understanding of our history and our thinking about the environment. His book is an exciting and learned account of scientific inquiry and revelation.

Why Billington Survived The Friendly Indian On March 22, 1621, an official Native American delegation walked through what is now southern New England to negotiate with a group of foreigners who had taken over a recently deserted Indian settlement. At the head of the party was an uneasy triumvirate: Massasoit, the sachem (political-military leader) of the Wampanoag confederation, a loose coalition of several dozen villages that controlled most of what is now southeastern Massachusetts; Samoset, sachem of an allied group to the north; and Tisquantum, a distrusted captive, whom Massasoit had reluctantly brought along as an interpreter. Massasoit was an adroit politician, but the dilemma he faced would have tested Machiavelli. About five years before, most of his subjects had fallen before a terrible calamity. Whole villages had been ...

Please be aware that this discussion guide will contain spoilers!

- "Beyond the Book" articles

- Free books to read and review (US only)

- Find books by time period, setting & theme

- Read-alike suggestions by book and author

- Book club discussions

- and much more!

- Just $45 for 12 months or $15 for 3 months.

- More about membership!

Media Reviews

Reader reviews, bookbrowse review.

In a book that startles and persuades, Mann reveals how a new generation of researchers equipped with novel scientific techniques came to previously unheard-of conclusions... continued

Full Review (286 words) This review is available to non-members for a limited time. For full access, become a member today .

(Reviewed by BookBrowse Review Team ).

Write your own review!

Beyond the Book

The article that formed the basis for this book was originally published in The Atlantic Monthly in 2002. If, after reading the extensive book excerpt and author interview at BookBrowse, you want to read more you can read the Atlantic Monthly article here . Also of interest is an extensive review in the Washington Post Book World written by Alan Taylor, the author of American Colonies , and a professor of history at the University of California at Davis. Did you know? In response to the frequently asked question, "why do you have a 'pretentious' C in your name?" Charles C Mann replies, "I get asked about this a lot, occasionally in exactly those words. The answer is not very interesting. I am named after ...

This "beyond the book" feature is available to non-members for a limited time. Join today for full access.

Read-Alikes

- Genres & Themes

If you liked 1491, try these:

On Savage Shores

by Caroline Dodds Pennock

Published 2023

About this book

A landmark work of narrative history that shatters our previous Eurocentric understanding of the Age of Discovery by telling the story of the Indigenous Americans who journeyed across the Atlantic to Europe after 1492

In Search of a Kingdom

by Laurence Bergreen

Published 2022

More by this author

In this grand and thrilling narrative, the acclaimed biographer of Magellan, Columbus, and Marco Polo brings alive the singular life and adventures of Sir Francis Drake, the pirate/explorer/admiral whose mastery of the seas during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I changed the course of history.

Books with similar themes

Support bookbrowse.

Join our inner reading circle, go ad-free and get way more!

Find out more

BookBrowse Book Club

Members Recommend

Bad Animals by Sarah Braunstein

A sexy, propulsive novel that confronts the limits of empathy and the perils of appropriation through the eyes of a disgraced small-town librarian.

The Day Tripper by James Goodhand

The right guy, the right place, the wrong time.

The Mystery Writer by Sulari Gentill

There's nothing easier to dismiss than a conspiracy theory—until it turns out to be true.

Who Said...

Experience is not what happens to you; it's what you do with what happens to you

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Solve this clue:

and be entered to win..

Your guide to exceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Subscribe to receive some of our best reviews, "beyond the book" articles, book club info and giveaways by email.

Authors & Events

Recommendations

- New & Noteworthy

- Bestsellers

- Popular Series

- The Must-Read Books of 2023

- Popular Books in Spanish

- Coming Soon

- Literary Fiction

- Mystery & Thriller

- Science Fiction

- Spanish Language Fiction

- Biographies & Memoirs

- Spanish Language Nonfiction

- Dark Star Trilogy

- Ramses the Damned

- Penguin Classics

- Award Winners

- The Parenting Book Guide

- Books to Read Before Bed

- Books for Middle Graders

- Trending Series

- Magic Tree House

- The Last Kids on Earth

- Planet Omar

- Beloved Characters

- The World of Eric Carle

- Llama Llama

- Junie B. Jones

- Peter Rabbit

- Board Books

- Picture Books

- Guided Reading Levels

- Middle Grade

- Activity Books

- Trending This Week

- Top Must-Read Romances

- Page-Turning Series To Start Now

- Books to Cope With Anxiety

- Short Reads

- Anti-Racist Resources

- Staff Picks

- Memoir & Fiction

- Features & Interviews

- Emma Brodie Interview

- James Ellroy Interview

- Nicola Yoon Interview

- Qian Julie Wang Interview

- Deepak Chopra Essay

- How Can I Get Published?

- For Book Clubs

- Reese's Book Club

- Oprah’s Book Club

- happy place " data-category="popular" data-location="header">Guide: Happy Place

- the last white man " data-category="popular" data-location="header">Guide: The Last White Man

- Authors & Events >

- Our Authors

- Michelle Obama

- Zadie Smith

- Emily Henry

- Amor Towles

- Colson Whitehead

- In Their Own Words

- Qian Julie Wang

- Patrick Radden Keefe

- Phoebe Robinson

- Emma Brodie

- Ta-Nehisi Coates

- Laura Hankin

- Recommendations >

- 21 Books To Help You Learn Something New

- The Books That Inspired "Saltburn"

- Insightful Therapy Books To Read This Year

- Historical Fiction With Female Protagonists

- Best Thrillers of All Time

- Manga and Graphic Novels

- happy place " data-category="recommendations" data-location="header">Start Reading Happy Place

- How to Make Reading a Habit with James Clear

- Why Reading Is Good for Your Health

- 10 Facts About Taylor Swift

- New Releases

- Memoirs Read by the Author

- Our Most Soothing Narrators

- Press Play for Inspiration

- Audiobooks You Just Can't Pause

- Listen With the Whole Family

1491 (Second Edition) Reader’s Guide

By charles c. mann.

Category: Indigenous Peoples’ History | Science & Technology

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Tumblr

READERS GUIDE

Introduction, questions and topics for discussion.

1. Mann begins the book with a question about our moral responsibility to the earth’s environment: Do we have an obligation, as some green activists believe, to restore environmental conditions to the state in which they were before human intervention [p. 5]? What does the story of the Beni tell us about what “before human intervention” might mean?

2. What scientists have learned about the early Americas gives the lie to what Charles C. Mann, and most of us, learned in high school: “that Indians came to the Americas across the Bering Strait about thirteen thousand years ago, that they lived for the most part in small, isolated groups, and that they had so little impact on their environment that even after millennia of habitation the continents remained mostly wilderness” [p. 4]. What is the effect of learning that most of what we have assumed about the past is “wrong in almost every aspect” [p. 4]?

3. There are many scholarly disagreements about the research described in 1491 . If our knowledge of the past is based on the findings of scholars, what happens to the past when scholars don’t agree? How convincing is anthropologist Dean R. Snow’s statement, “you can make the meager evidence from the ethnohistorical record tell you anything you want” [p. 5]? Are certain scholars introduced here more believable than others? Why or why not?

4. Probably the most devastating impact from the contact between Europeans and Americans came from the spread of biological agents like smallpox. Of Mann’s various descriptions of the effects of foreign diseases on the Americas’ native populations [pp. 96—124], which are most shocking, and why? How do you respond to his questions on page 123: “In our antibiotic era, how can we imagine what it means to have entire ways of life hiss away like steam? How can one assay the total impact of the unprecedented calamity that gave rise to the world we live in?”

5. In the nineteenth century, historian George Bancroft described pre-contact America as “an unproductive waste. . . . Its only inhabitants were a few scattered tribes of feeble barbarians, destitute of commerce and of political connection” [pp. 14—15]. To what degree is the reflexive ethnocentrism of earlier times responsible for the erroneous history of the Americas we have inherited?

6. When Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto brought pigs along on his expedition in order to feed himself and his men, the pigs carried microbes that apparently wiped out the Indian populations in the southeast part of the current United States [p. 108—09]. While this episode illustrates the haphazard quality of biological devastation, how does it also connect 1491 to our contemporary world, in which the media reports daily on scientists’ fear of diseases like avian flu jumping from animal to human populations? In our present global environment, are we as vulnerable as the Indian tribes discussed by Mann? Are there, as he suggests, moral reverberations to be felt as a result of the European entrance into the Americas five centuries ago [p. 112]?

7. Several of the cultures discussed by Mann honored their dead so highly that, in effect, the dead were treated as if they were still alive. What is most interesting about the attitudes toward death and the dead found in the Chinchorro [pp. 200—01], the Chimor [p. 264], and the Inka [p. 98] cultures?

8. Much of America’s founding mythology is based on the idea of the land as an untouched wilderness, yet most scholars now agree that this pristine myth [p. 365] was a convenient story that the early settlers told themselves. What kinds of actions did the myth support, and how did it serve the purposes of the settlers?

9. Because of the lack of documentary and statistical evidence for the mass death caused by disease in the New World, experts have argued about the size of the pre-Columbian population. The so-called High Counters, according to their detractors, “are like people who discover an empty bank account and claim from its very emptiness that it once contained millions of dollars. Historians who project large Indian populations, Low Counter critics say, are committing the intellectual sin of arguing from silence” [p. 112]. Yet those who count low, Indian activists say, do so in order to diminish not only the mass death suffered by indigenous peoples, but also the significant achievements of their pre-contact cultures. Which side does it seem Charles Mann leans toward? Which side do you find more believable?

10. Consider Mann’s remark about what was lost because of the destruction wrought by Cortés and others: “Here, at last, we begin to appreciate the enormity of the calamity, for the disintegration of native America was a loss not just to those societies but to the human enterprise as a whole. . . . The Americas were a boundless sea of novel ideas, dreams, stories, philosophies, religions, moralities, discoveries, and all the other products of the mind” [p. 137]. How might the world have been different had the ancient cultures of the Americas survived into the present?

11. Mann writes, “Native Americans were living in balance with Nature–but they had their thumbs on the scale. . . . The American landscape had come to fit their lives like comfortable clothing. It was a highly successful and stable system, if ‘stable’ is the appropriate word for a regime that involves routinely enshrouding miles of countryside in smoke and ash” [p. 284]. Why did the Indians burn acres of land? Does Mann suggest that there are the ecological lessons for our own time in the Native Americans’ active manipulation of their environment?

12. Using the words of Harvard biologist Edward O. Wilson, Mann explains that a “keystone” species is one “that affects the survival and abundance of many other species”; Mann adds that, “Keystone species have disproportionate impact on their ecosystems” [p. 352—53]. Indians were a keystone species in most of the hemisphere before the arrival of Columbus. What force led to their greatly diminished importance in the evolution of the hemisphere’s ecosystems? If our species now has an even greater impact on the world ecosystems, does Mann suggest ways to avoid disasters such as those he delineates in 1491 ?

13. Discussing foreign environmentalists’ opinions about saving the Amazonian forests, Mann raises a problem with the whole environmental movement: Those in poverty-stricken areas like Amazonia want development and jobs; wealthy, well-educated people in the U.S. and Europe tend to want to preserve these forests [pp. 363—64]. How can this problem be resolved?

14. The Gitksan Indians of Canada’s Northwest have argued a case in the Supreme Court of Canada that “the Gitksan had lived there a long time, had never left, had never agreed to give their land away, and had thus retained legal title to about eleven thousand square miles of the province” [p. xi]. What are the implications of such a claim for the various peoples and tribes that Mann discusses in 1491 , and for the descendants of European settlers?

15. What does Mann mean in saying, “Understanding that nature is not normative does not mean that anything goes. . . . Instead the landscape is an arena for the interaction of natural and social forces, a kind of display, and one that like all displays is not fully under the control of its authors” [p. 365—66]?

16. People have long believed that being in the wilderness conveys a sense of the sacred. Mann explains, “The trees closing over my head in the Amazon furo made me feel the presence of something beyond myself, an intuition shared by almost everyone who has walked in the woods alone. That something seemed to have rules and resistances of its own, ones that did not stem from me” [p. 365]. What happens to this idea of a non-human force in nature if, as Mann concludes, the concept of nature is a human creation?

17. Why does Mann end 1491 with a coda on the Haudenosaunee “Great Law of Peace,” and what resonance does it have for the book as a whole?

About this Author

Suggested reading, related books and guides.

Visit other sites in the Penguin Random House Network

Raise kids who love to read

Today's Top Books

Want to know what people are actually reading right now?

An online magazine for today’s home cook

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

- Period 1: 1491–1607

Period 1: 1491-1607

On a North American continent controlled by American Indians, contact among the peoples of Europe, the Americas, and West Africa created a new world. Topics may include

Native American Societies before European Contact

European exploration in the new world, the columbian exchange, labor, slavery, and caste in the spanish colonial system, cultural interactions between europeans, native americans, and africans.

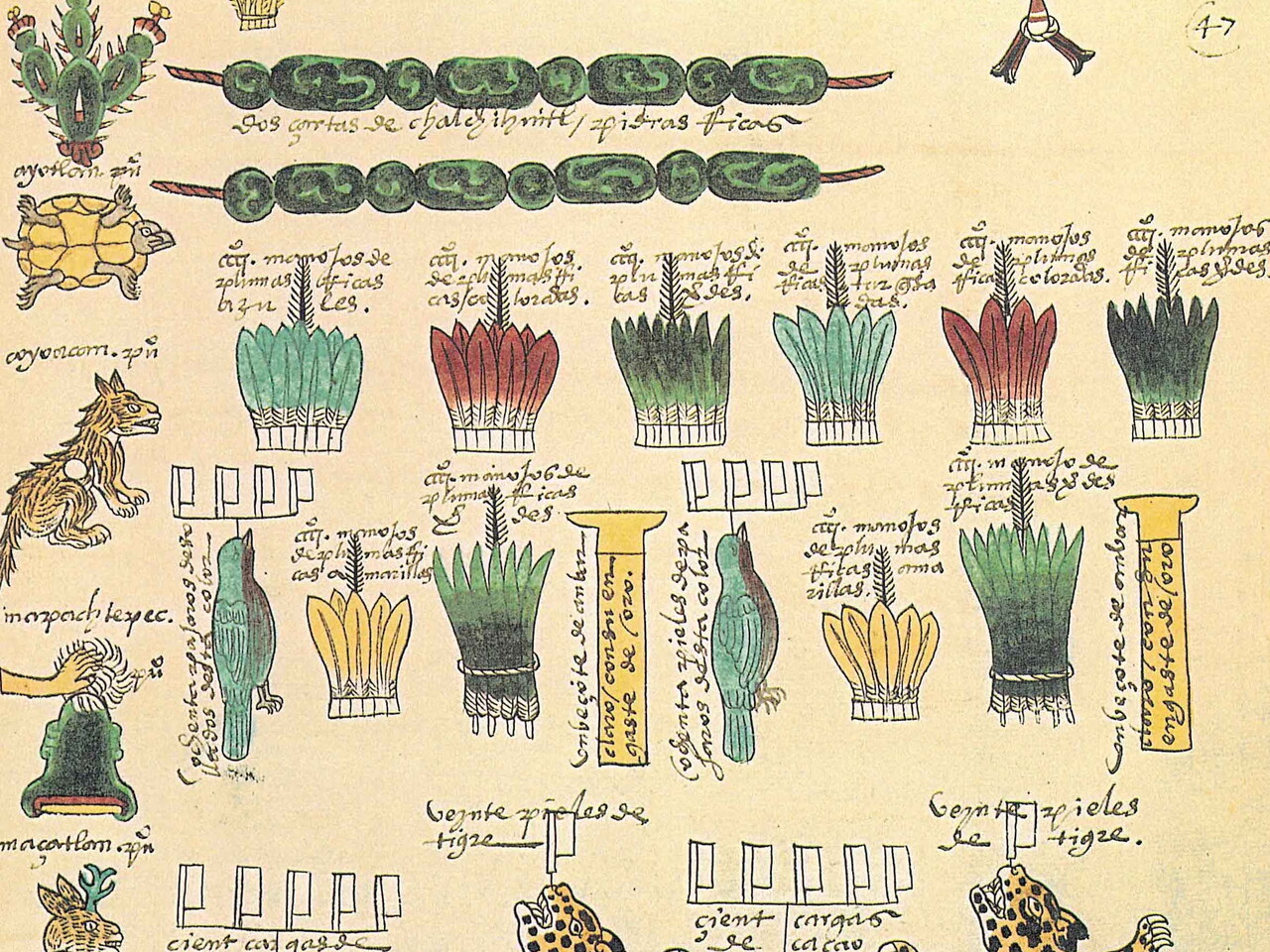

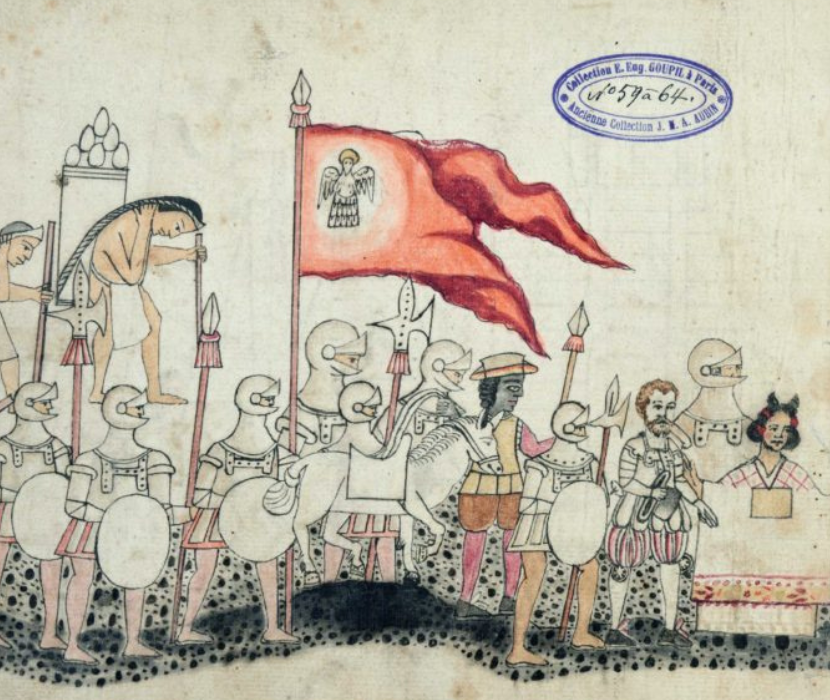

Image Source : View of icons representing conquered towns and the tributes they paid to the Aztecs in a detail from the Codex Mendoza, ca. 1541 (Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford)

4–6% Exam Weighting

Resources by Period:

- Period 2: 1607–1754

- Period 3: 1754–1800

- Period 4: 1800–1848

- Period 5: 1844–1877

- Period 6: 1865–1898

- Period 7: 1890–1945

- Period 8: 1945–1980

- Period 9: 1980–Present

Key Concepts

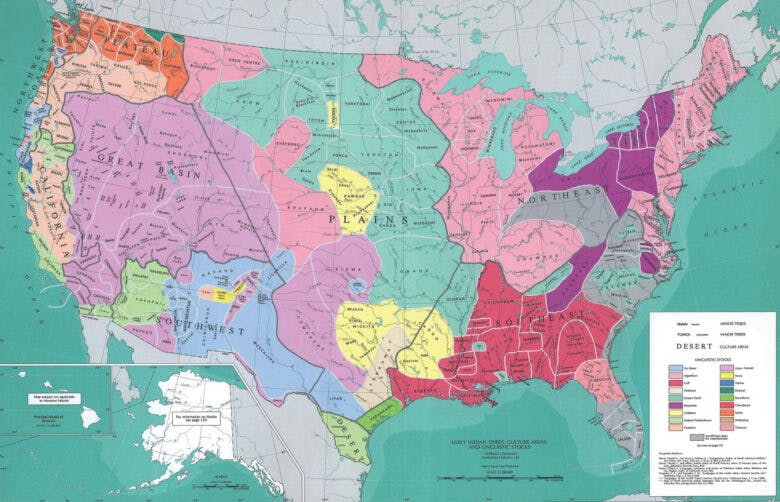

1.1 : As native populations migrated and settled across the vast expanse of North America over time, they developed distinct and increasingly complex societies by adapting to and transforming their diverse environments.

1.2 : Contact among Europeans, Native Americans, and Africans resulted in the Columbian Exchange and significant social, cultural, and political changes on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

American Indians

By elliott west.

Learn about the diversity of Indigenous tribes in North America.

Cahokia: A Pre-Columbian American City

By timothy r. pauketat.

Learn about a center of trade and interaction built along the banks of the Mississippi.

Nature, Culture, and Native Americans

By daniel wildcat.

Watch a discussion about Indigenous peoples and their interaction with the environment.

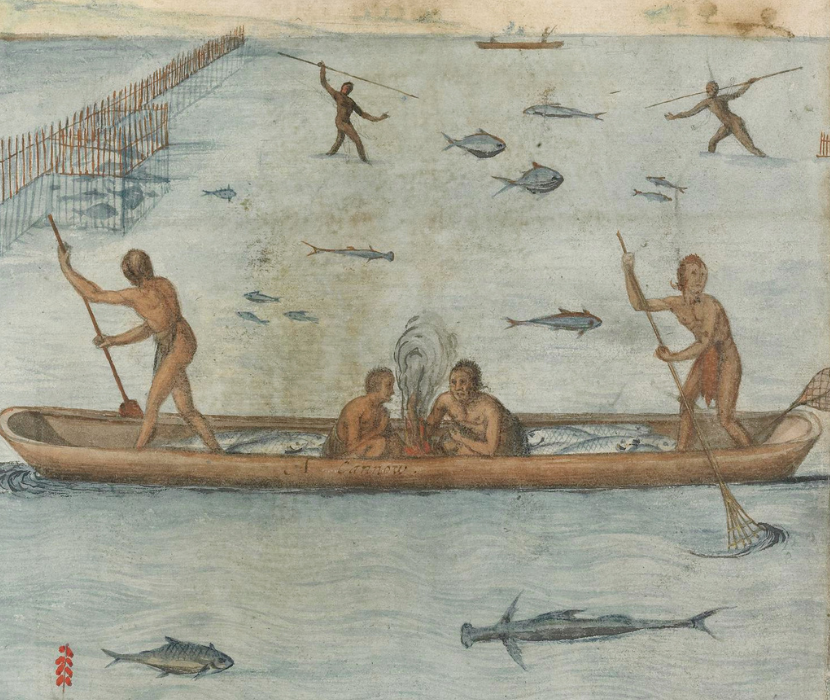

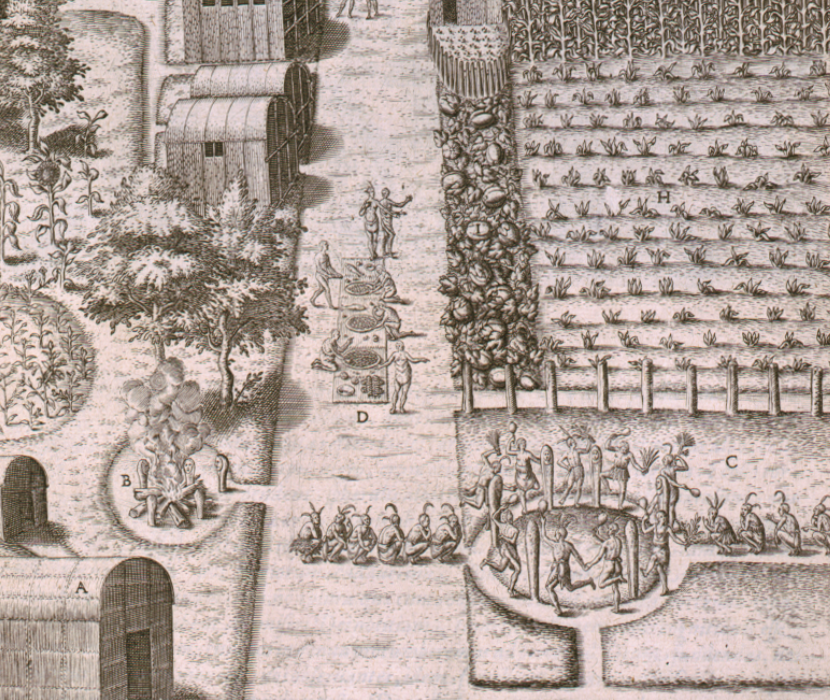

Secotan, an Algonquian village

Engraving of an agrarian town in North America, based on a watercolor by English mapmaker John White

- Primary Source

North America on the Eve of the European Invasion

By christopher l. miller.

Discover the way Native Americans lived in North America before Europeans arrived.

Native American Discoveries of Europe

By daniel k. richter.

Learn about the cultural context of Native peoples' responses to the arrival of European explorers and colonists.

America before Columbus

By charles c. mann.

Watch a discussion about the pre-Columbian population and settlement of the Americas.

An Introduction to the History of Migration and Settlement in North America

By edward a. jolie.

Learn about the migrations of indigenous peoples in the Americas.

Europeans and the New World

By brian delay.

Watch a discussion of the context of western European exploration and European interactions with Indigenous peoples.

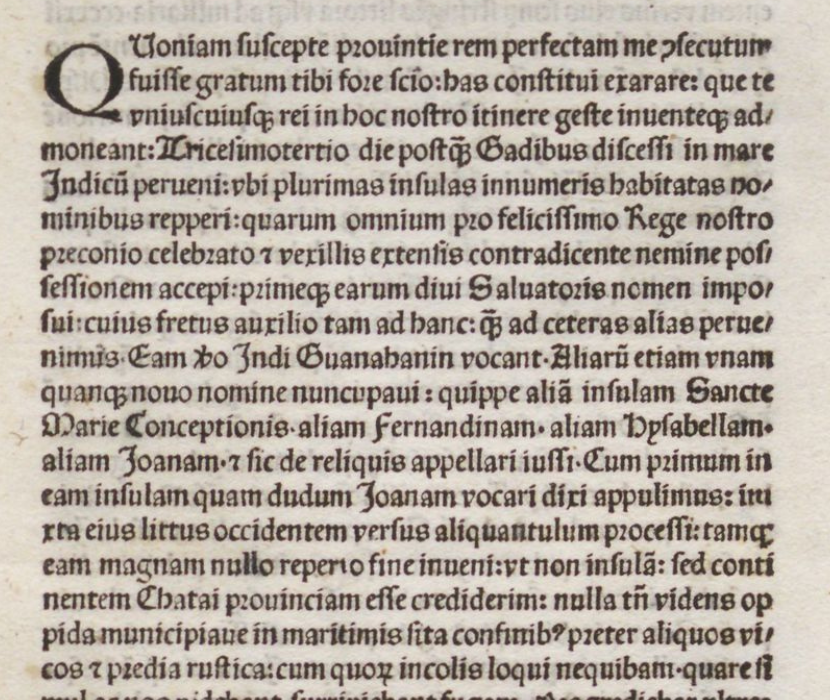

Columbus reports on his first voyage

Columbus’s letter to Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain announcing the discovery of unknown lands

Imperial Rivalries

By peter c. mancall.

Understand how European political competition in the late fifteenth century drove exploration and colonization.

Sir Francis Drake's attack on St. Augustine

Illustration depicting an English naval attack on Spanish St. Augustine in present-day Florida

The Rise and Fall of New Netherland

By david middleton.

Read about Henry Hudson’s voyages for the Dutch Republic.

Mexicans in the Making of America

By neil foley.

Learn about Spanish exploration and conquest of the Americas in a broad essay about changes and continuities.

European Exploration

By felipe fernández-armesto and benjamin sacks.

Learn about European navigation and the exploration of the Americas.

Navigating the Age of Exploration

By ted widmer.

Learn about the vast global movements that characterized the Columbian Exchange.

by Alfred W. Crosby

Discover how the commingling of Old and New World plants, animals, and bacteria remade global ecologies.

The Spanish Borderlands and Columbian Exchange

By ned blackhawk.

Learn about Indigenous and European interactions in Spanish colonial holdings in the Americas.

The Americas to 1620

Learn about the broad context of European, African, and Indigenous interactions.

The Doctrine of Discovery

Pope Alexander VI’s decree granting Spain the exclusive right to lands in the Americas

Iberian Roots of the Transatlantic Slave Trade

By david wheat.

Understand the role of Portugal and Spain in the transatlantic slave trade.

Disputing the subjugation of the Indians

Bartolomé de las Casas versus Juan Ginés Sepúlveda on the enslavement of the Taíno in Hispaniola

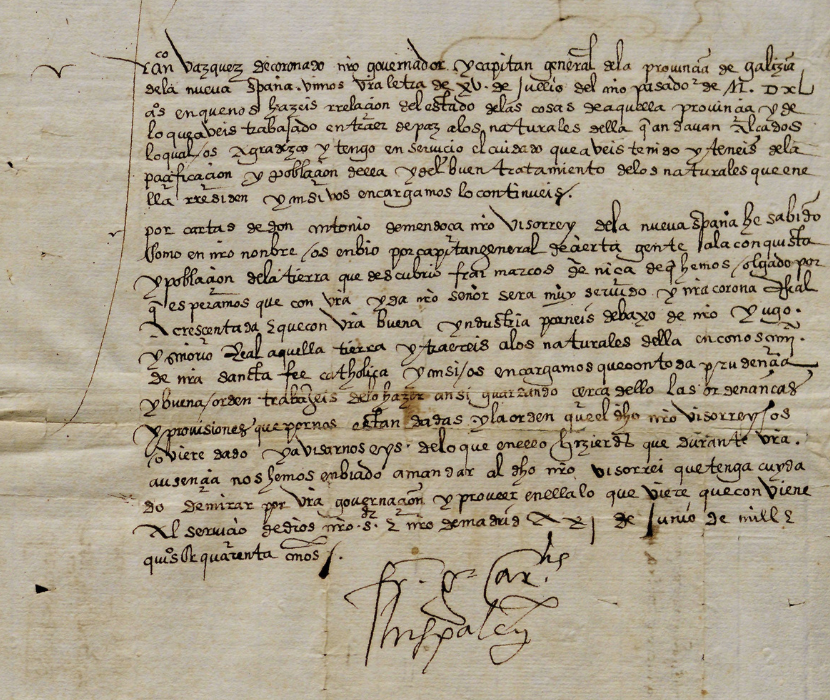

Spain authorizes Coronado's conquest in the Southwest

Royal letter instructing Francisco Coronado to explore the northern lands in search of wealth and resources

Early North America

Look beyond the Euro-centric view of the “New World.”

Indian Slavery in the Americas

By alan gallay.

Learn about the European enslavement of Indigenous peoples in the Americas.

The New York African Burial Ground

By edna greene medford.

Read about one of the earliest graveyards for free and enslaved Africans.

The African Slave Trade

By philip morgan.

Watch a discussion of the core experiences of slavery from East Africa to sugar plantations in the New World.

American History Timeline: 1491-1607

Image citations.

Listed in order of appearance in the sections above

- White, John. The Towne of Pomeiock. 1585-1593. Drawing on paper. British Museum. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1906-0509-1-8

- William Iseminger, Cahokia Mounds, 1982, Painting. Image courtesy of Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site.

- White, John. The Manner of Their Fishing. 1585-1593. Watercolor over graphite on paper. British Museum.

- de Bry, Theodor. Village of Secotan. In A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia: of the Commodities and of the Nature and Manners of the Naturall Inhabitants. Frankfurt am Main: J. Wechelus, 1590. Engraving based on a drawing by John White. Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

- "Naw-Kaw, a Winnebago Chief." In The Indian Tribes of North America, vol. 1, by Thomas L. McKenney and James Hall. Philadelphia, ca. 1840. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC05120.02. Grasset de Saint-Saveur, Jacques. "Tableau des principaux peuples de l'Amérique." Paris, France. 1789. Etching and aquatint with hand coloring. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Theodore de Bry, Indians worship the column in honor of the French king, 1591, engraving for Collectiones peregrinationum in Indiam occidentalem, vol. 2: René de Laudonnière, Brevis narratio eorum quae in Florida Americae provincia Gallis acciderunt (Frankfurt am Main: J. Wechelus, 1591) (Rijksmuseum)

- Hiser, David. Pictograph at Newspaper Rock, Indian Creek State Park, San Juan County, Utah. DOCUMERICA: The Environmental Protection Agency's Program to Photographically Document Subjects of Environmental Concern, 1972. Photograph. National Archives.

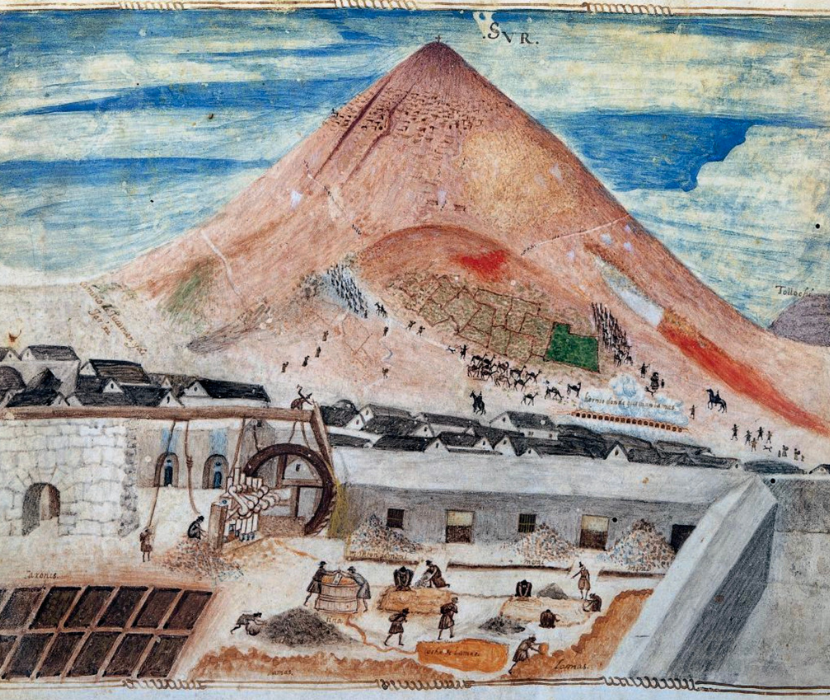

- Anonymous Spanish artist. The Silver Mine at Potosí. ca. 1585. Watercolor on parchment. The Hispanic Society of America.

- Columbus, Christopher. Letter to Ferdinand and Isabella, February 1493. Epistola Chirstofori Colom: cui [a]etas nostra multu[m] debet: de Insulis Indi[a]e supra Gangem nuper inuentis. Rome, 1493. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC01427.

- Engagement [between] La Blanche and La Pare, ca. 1786-1805. Watercolor on paper. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC01450.800.

- Boazio, Baptista. Drake’s Attack on St. Augustine, Florida, May 28–29, 1586. St. Augustine Map. 1589. Rare Books and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress.

- Schenk, Peter. Nieu Amsterdam, een Stedeken in Noord Amerikaes Nieu Hollant. s.l., 1702. Print. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC03022

- "An illustrated account of Aztec life-cycles" Codex Mendoza. ca. 1540. Manuscript on paper. Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

- Martin, Johnson & Company. Landing of Columbus. New York, 1856. Engraving based on a painting by John Vanderlyn. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC08878.0001.

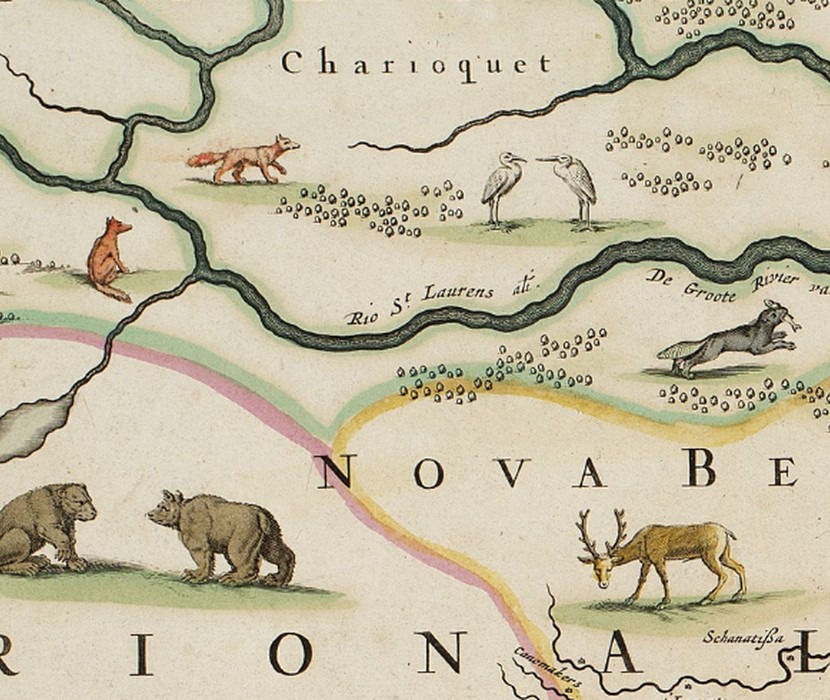

- Visscher, Nicholas. Novi Belgi Novaeque Angliae [Map of New Netherland and New England]. Amsterdam, 1682. Map. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC03582.

- Kemmelmeyer, Frederick. First Landing of Christopher Columbus. 1800/1805. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art.

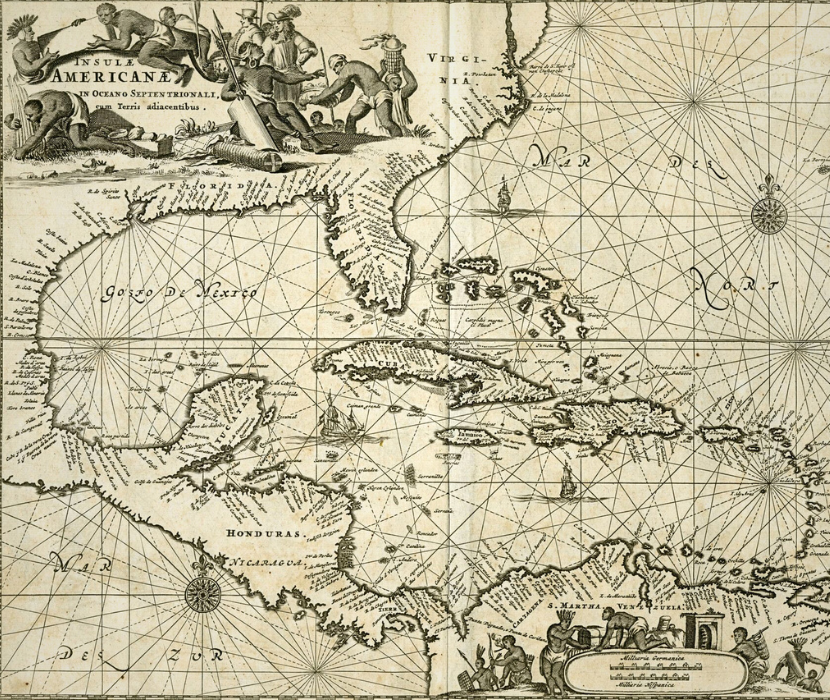

- Montanus. Insulae Americanae in Oceano Septentrionali, cum Terris adiacentibus [Map of the Americas]. s.l., 1671 Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC09789.

- Johnson, Fry & Company. Landing of Roger Williams. New York, 1867. Engraving based on a painting by Alonzo Chappel. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC08878.0006

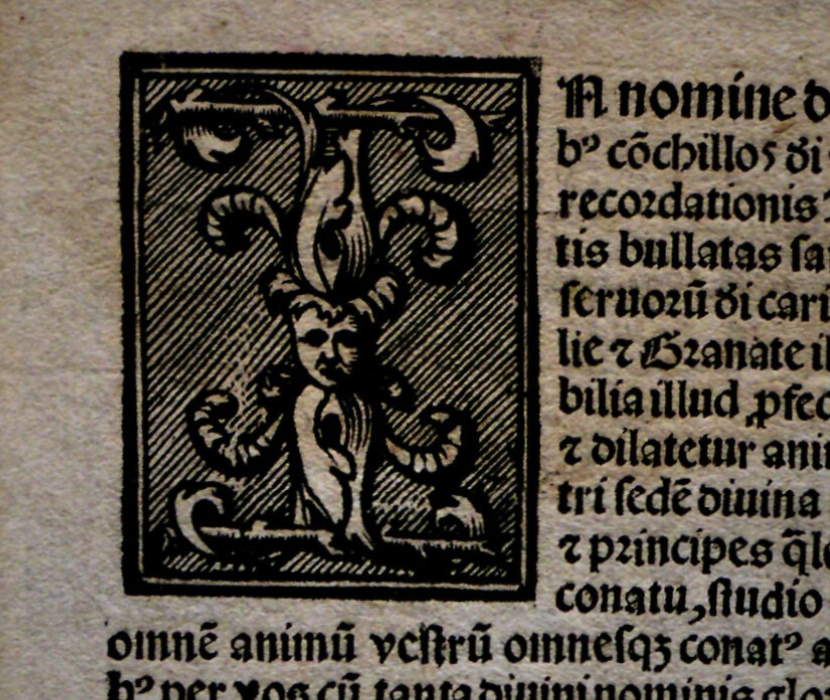

- Alexander VI. Copia de la bula del decreto y concession q[ue] hizo el papa [Inter caetera]. [Valladolio], 1493. Broadside. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC04093.

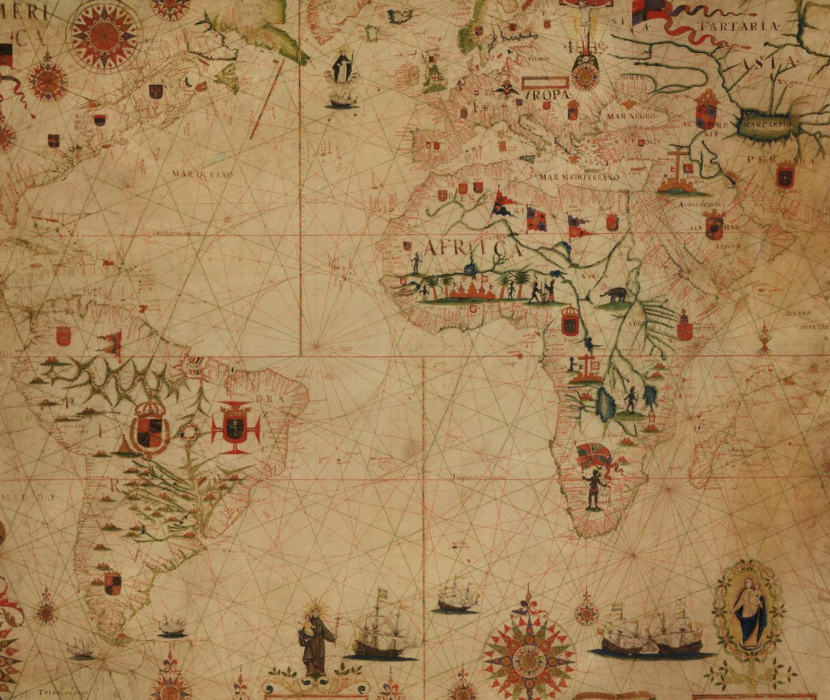

- Roiz, Pascoal. A portolan chart of the Atlantic Ocean and adjacent continents. 1633. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2008621738/.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé de. Aqui se contiene una disputa . . . Seville, 1552. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC04220.

- García de Loaysa, Francisco. Letter to Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, June 21, 1540. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC04883.

- Cliff Palace. Ancestral Puebloan (formerly Anasazi), 450–1300 C.E. Sandstone. Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado. Photo courtesy of Sara Charles.

- "The March of the Spaniards into Tenochtitlan." Codex Azcatitlan. ca. 1530. Manuscript on paper. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- Carol Highsmith. African Burial Ground National Monument. New York, 2008. Photograph. Carol Highsmith Archive. Library of Congress.

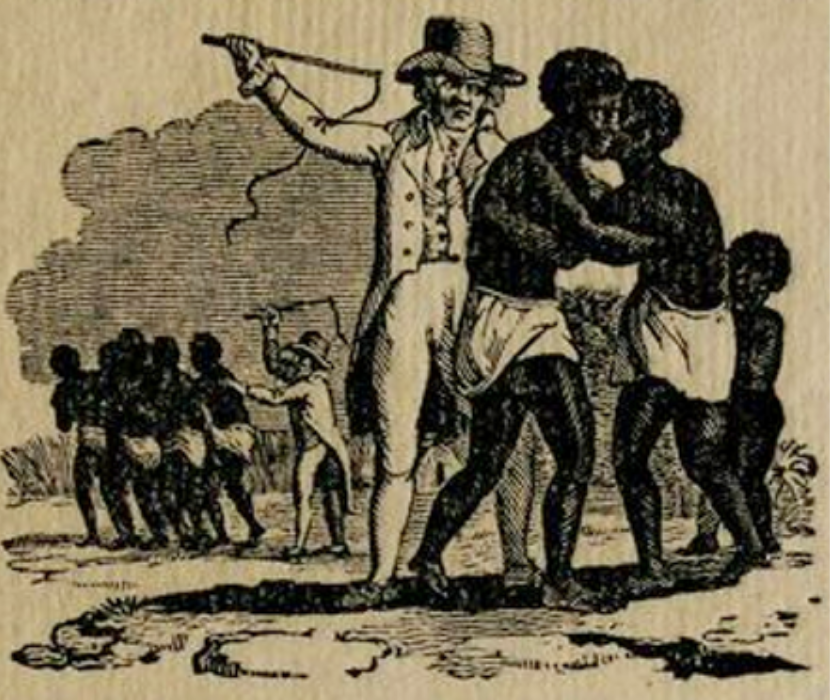

- Wood, Samuel. Injured Humanity; Being a Representation of What the Unhappy Children of Africa Endure from Those Who Call Themselves Christians. New York, 1805. Broadside. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC05113.

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

Chapter 1 Introductory Essay: 1491-1607

Written by: Alan Taylor, University of Virginia

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain the context for European encounters in the Americas from 1491 to 1607

Introduction

During the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, Europeans explored the world’s oceans and distant coasts. Once a barrier to exploration, the Atlantic Ocean now became their route to other seas, faraway regions, and people unknown. In the “Age of European Exploration,” voyagers rounded southern Africa to cross the Indian Ocean, reaching India and the East Indies. Between 1519 and 1521, Portugal’s Ferdinand Magellan became the first person to circle the globe. In an unprecedented burst of new geographic knowledge, daring, and enterprise, explorers built outposts on newly discovered shores, creating the first global trade empires based on oceanic shipping. (See the Ship Technology Lesson.)

The Iberian countries of Spain and Portugal led the way in the European Age of Exploration and the creation of maritime empires. Spanish shipping routes are shown in white and Portuguese routes in blue.

The Portuguese and the Spanish in the New World

The expansion was begun by Portugal, a kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula of southwestern Europe. Sailing along the west coast of Africa, Portuguese mariners sought new sources of gold, ivory, pepper, and slaves. They slowly but steadily probed southward until 1498, when Vasco da Gama sailed around the continent’s southern tip and crossed the Indian Ocean to reach India. The riches of that new trade route fascinated Portugal’s Iberian neighbors, the Spanish. Seeking an alternate route to the trade riches of Asia, the Spanish rulers Ferdinand and Isabella enlisted the help of a mariner from Genoa (in what is now Italy) named Christopher Columbus. Like other educated Europeans, Columbus knew the world was round. Therefore, in theory, sailing due west would take his fleet to China or Japan, promising sources of silks and spices. He had no idea, however, of the exact circumference of the earth and greatly underestimated it. He also did not know that the Americas would block a direct voyage westward. In 1492, with three ships and ninety men, Columbus followed the trade winds southwest from Spain past the Canary Islands and out into the Atlantic. To his surprise, he reached then-unknown islands, the Bahamas and West Indies, located in the Caribbean Sea. Columbus stubbornly insisted that the islands were the East Indies near the mainland of Asia. Although the natives, the Taino, were unlike any people he had ever seen or read about, he called them “Indians,” a name for all the native populations that has stuck in the writings of Europeans and their descendants. (See the Native People Narrative.) Sailing home, Columbus reported to Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain in early 1493. They authorized an immediate and larger expedition of seventeen ships, twelve hundred men, and many livestock. This time the Spanish came to stay, to dominate the land and the natives, and to weave the new settlements into an empire to support a European power. Colonization proved tragic for the Taino. The Spanish viewed them as primitive savages fit for conquest and slavery. They aimed to convert the natives to Christianity and introduce them to the civilization of Spain. Using the military advantages of horses, cannons, steel swords, pikes, and crossbows, the Spanish killed and captured thousands of Taino. Others they shipped to Spain for sale as slaves, but most had to work on plantations or in gold mines in the new Spanish colonies. The Taino population declined from 300,000 in 1492 to a mere five hundred by 1548. Most died as a result of diseases to which they lacked immunity and that unintentionally were brought across the Atlantic by the Spanish, though some died because of enslavement and outbreaks of violence. The Spanish had not intended to destroy the Indians, whom they preferred to exploit as workers and tributaries—but exploitation sometimes led to violence. (See the First Contacts Narrative the Should We Remember Christopher Columbus as a Conqueror or Explorer? Point-Counterpoint and the Paideia Seminar: Christopher Columbus Lesson.) To continue to work their mines, ranches, and plantations, the Spanish colonists sought new slaves by raiding the mainland of Central and South America. In Cuba, a brilliant but ruthless adventurer named Hernán Cortés became intrigued by reports of a wealthy empire in the highlands of central Mexico. There, by conquering their neighbors and exacting tribute, the Aztecs had grown rich and built a city called Tenochtitlan that was larger than any city in Spain. It featured lofty pyramids superintended by priests and ruled by an emperor named Montezuma. But in their rise to power, the Aztecs had also made enemies an invader could recruit. By alternating brutal force with shrewd diplomacy, Cortés forged partnerships with Indians along his route into Mexico’s interior. Alarmed by the Spanish weapons and alliances, Montezuma tried to buy Cortés off with gifts. Instead, the invader seized the emperor. When the Aztecs fought back, the Spanish destroyed Tenochtitlan. Deploying thousands of new captives as slaves, the Spanish rebuilt the city as the capital of a new colony, which they called New Spain. By his death in 1547, Cortés had become the wealthiest man in the new Spanish empire. (See the Montezuma and Cortes Decision Point and the Cortes’s Account of Tenochtitlan 1522 Primary Source.) Cortés’s spectacular success inspired other Spanish conquistadores—enterprising soldiers who sought wealth. The conquistadores regarded plunder, slaves, and tribute as just rewards for men who forced pagans to accept Spanish rule and the Christian faith. Although many Indians embraced the Christianity promoted by Roman Catholic Spanish missionaries and its promise of eternal life in heaven, many others, noting that the Spanish appeared immune to disease, suspected the newcomers knew some powerful supernatural secret that spread death. In search of relief, some embraced the new religion because they saw it as a source of magical protection. Some missionaries spoke out against the heavy casualties and massive destruction wrought by the conquistadores. These missionaries urged the Spanish crown to exercise greater control over the distant colonies, subordinating the private armies of soldiers. The most eloquent critic was Bartolomé de Las Casas, a former conquistador who repented and became a priest. (See the Las Casas on the Destruction of the Indies 1522 Primary Source.) Las Casas argued for the humanity and natural rights of the natives. He asked: “Are these Indians not men? Do they not have rational souls? Are you not obliged to love them as you love yourselves?”

The Spanish crown did issue more rules governing the colonies, but the effort was hampered by continental wars and the Protestant Reformation in Europe, which diverted attention away from the colonies. The crown agreed that the conquistadores killed too many Indians, who might otherwise have become Christian converts and taxpaying subjects. From about ten million in 1500, the Indian population of Mexico declined to one million by 1620. The decline came about primarily from epidemics of new diseases unwittingly introduced by the invaders, but also was the result of violence. (See the Columbian Exchange Narrative and The Florentine Codex c. 1585 Primary Source.)

Missionary priests also criticized the legal authority granted to conquistadores as exploitive and destructive to Indian communities. Successful conquistadores obtained legal rights known as encomienda to govern and collect tribute from particular Indian village. In return, the encomendero was supposed to promote the conversion of Indians to Christianity by supporting a priest and building a church. Other Spaniards obtained private land grants known as hacienda, which displaced Indian settlements and substituted ranches and mines. In 1573, the priests persuaded the crown to issue the Royal Orders for New Discoveries, which sought to reduce violence against Indians by increasing the power of priests over expeditions by conquistadores . (See the Life in the Spanish Colonies Narrative and the Columbus’s Letter to Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain 1494 Primary Source.)

In this startling image from the Kingsborough Codex (a book written and drawn by native Mesoamericans) a well-dressed Spaniard is shown pulling the hair of a bleeding severely injured Indian. The drawing was part of a complaint about Spanish abuses of their encomiendas.

The priests were not blameless. They demanded that Indians surrender their traditional beliefs and behaviors and adopt the ways of the Spanish. To that end, they oversaw the destruction of Indian temples, prohibited customary dances, and obliged Indians to practice the rituals of a new faith. The missionaries also ended the Aztec practice of human sacrifice to appease their sun god. Many Indians tried to adapt, but few, if any, could so quickly and completely change everything they believed. While publicly practicing Christianity, some still secretly venerated old idols and conducted traditional ceremonies. They assimilated the Christian faith into their traditional forms of worship. By 1540 in the Americas, the Spanish had developed the largest empire ever ruled by Europeans, larger even than the ancient domain of the Romans. At its core were the gold- and silver-rich colonies of Mexico and Peru, which eclipsed Spain’s initial settlements on the islands of the Caribbean. During the sixteenth century, the new colonies attracted 250,000 Spanish emigrants. Most of the emigrants were men; they married the widows and daughters of conquered Indians, with whom they produced mixed-race children known as mestizos, who became the majority population of New Spain by 1700. The core colonies developed hundreds of carefully planned towns with a grid of streets around a central plaza, which featured a municipal hall and a church. These towns were trading centers for a land of shrinking Indian villages and expanding Spanish farms and ranches. Ambitious conquistadores probed northward, deep into the continental interior of what is now the United States, in search of riches held by other Indian empires. In 1539, Hernando de Soto led an expedition from Cuba that landed in what is now Florida and crossed the American southeast, reaching the Mississippi River. The Spanish discovered many large towns, vast fields of corn, and earthen pyramids topped by wooden temples, but almost no gold. In frustration, they slaughtered Indians who resisted them. In 1542, de Soto fell ill and died, and the remaining men built boats to sail down the Mississippi and return empty handed to Mexico. They left behind diseases that ravaged the region’s Indian nations, reducing the populations to a fraction of their size before contact with Europeans. The survivors of these epidemics abandoned the great riverside towns and pyramids, dispersing into the hilly hinterland. (See the Hernando de Soto Narrative.)

Hernando de Soto’s exact route is not known but he and his men opened the door for future Spanish exploration and settlement.

In 1540, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado led a similar expedition north, this time from Mexico into the American southwest, seeking the mythical Seven Cities of Cibola and their fabulous riches. Reaching modern New Mexico, he found substantial villages made of stone and adobe brick, which he called pueblos. He called all the inhabitants “the Pueblos,” although they actually belonged to several cultures with distinct languages. Failing to find gold or silver, Coronado and his conquistadores provoked violence with the Pueblos after demanding supplies. The Spanish also attacked a dozen villages of the Tiwa Indians after again failing to acquire gold or supplies. Pressing northeastward, they crossed a vast grassy plain known now as the Great Plains. With little wealth to show for his venture, Coronado retreated to Mexico in 1542. The de Soto and Coronado expeditions were expensive failures and discouraged further efforts by conquistadores. But missionaries wanted to return to the northern frontier of Spain’s new empire, to convert the Indians of Florida and New Mexico. They won support from Charles V, who, as the leader of the preeminent Catholic power in Europe, took the conversion of Indians and the expansion of the faith seriously. The king also saw a Spanish missionary presence as a buffer to keep rival European powers from developing colonies that might be used as a base from which to attack Spain’s valuable territory in Mexico. In 1564, in fact, a French expedition built a fort it called Fort Caroline on the Atlantic coast of Florida. In 1565, the Spanish sent Pedro Menéndez de Avilés with a small army to take the fort by surprise, slaughter the French garrison, and build a Spanish town named San Agustin (now St. Augustine). The Spanish were unable to attract many colonists to Florida because of repeated Indian attacks and the vast distance from Mexico. However, they tried to convert Indians to Hispanic ways at missions that stretched across the region to the Gulf Coast. By 1675, forty priests were ministering to twenty thousand Indians at thirty-six missions in Florida. The Spanish also reoccupied the Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico, with a system of forts and missions centered around a capital they named Santa Fe (meaning “holy faith”). Too few colonists went to such a distant and isolated colony, so again the soldiers and priests had to rely on converting the Indians and taking tribute from them. By the end of the sixteenth century, King Philip II of Spain ruled not only the Iberian Peninsula (including Portugal) but also a massive empire in the New World, which stretched from modern Florida and New Mexico in North America to the lands of the conquered Inca empire in South America. The Spanish generated great wealth at their core bases in Mexico and Peru. Between 1500 and 1650, they shipped 181 tons of gold and sixteen-thousand tons of silver from the Americas to Europe. This bullion enabled the Spanish to raise and pay for large armies in Europe. The armies dominated Italy and the Netherlands and threatened the rest of Europe.

Threats to Spanish Sovereignty

To even the military odds in Europe, the French, English, and Dutch wanted a share of the wealth being generated in the Americas. The quickest way to get it was to steal gold and silver from Spanish ships bound for Europe. Queen Elizabeth I of England (even sanctioned privateers, government-licensed pirates, to raid Spanish ships laden with New World treasure. During the 1580s and 1590s, Francis Drake the most successful English pirate sailed into the Pacific Ocean to capture Spanish ships along the Peruvian and Mexican coasts before heading west to complete his voyage around the globe. Lashing back in 1588, Philip II sent an armada of warships to seize control of the English Channel and assist in an invasion of England. But the English navy and fierce storms combined to scatter and destroy most of the Spanish fleet. Thereafter, Spanish naval power declined while England and France expanded their commercial and colonial reach.

This famous Arcada Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I was painted after England’s defeat of Spain in 1588. How has the artist communicated the queen’s power in this image?

State-sanctioned piracy could generate spectacular but unpredictable windfalls. To obtain steadier profits, the other European powers wanted their own American colonies. They wanted to exploit precious mines and develop plantations to raise tropical crops—sugar, cacao, and tobacco—that sold for high prices in Europe. Arguing for the benevolence of their own New World colonies, the French and English developed the “black legend” that the Spanish were uniquely cruel and destructive. Therefore, these critics argued, the Indians would welcome other Europeans as liberators. The French and the English had many violent encounters with American Indians in Canada and the eastern seaboard of North America. One English colonist wrote, “Our intrusion into their possession shall tend to their great good, and no way to their hurt, unlesse as unbridled beastes, they procure it to themselves.” For his part, the Powhatan leader Opechancanough asserted, “Before the end of two moons there should not be an Englishman in all their countries.” English settlers at Jamestown and Powhatan Indians attacked each other and sometimes engaged in wholesale massacres and retaliatory strikes. Although most encounters were based upon mutually beneficial trade, violence erupted often between Europeans and American Indians.

The French Arrive in the North

As the French found out in Florida in 1565, it was dangerous to settle too close to the Spanish colonies. The French did better when they probed the northern waters and coasts of Canada—a land the Spanish had dismissed as too cold and barren—in the early seventeenth century. The French hoped to find either precious metals or the fabled Northwest Passage through, or around, the continent to reach the Pacific and the trade riches of Asia. Failing in both goals, they instead discovered coastal waters teeming with fish and sea mammals: seals and whales. During the warmer months, French fishermen began to visit the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Grand Banks near Newfoundland. In the fall, they sailed home with their catch, which they had dried in the sun and packed into barrels. Some fishermen began to trade with the Indians, who were skilled hunters living among many fur-bearing mammals, particularly beaver. Although the northern climate discouraged agriculture, it yielded especially thick and valuable furs, which fetched high prices back in Europe, where a craze for felt hats had developed. Indians eagerly traded the furs for European goods, including steel knives, hatchets, and arrowheads. (See the Henry Hudson and Exploration Narrative.) Indians grew dependent on these new goods, especially the steel weapons. Well-armed Indians nations could attack their neighbors, taking away valuable hunting grounds where they could kill more beavers to trade for more weapons. To avoid destruction, all had to find a European trade partner. But the Indians could also manipulate the French traders, who dared not alienate their suppliers of furs. Coming in small numbers as they did, the French could not afford to bully, dispossess, or enslave the Indians of Canada. In 1608, Samuel de Champlain founded a permanent French trading post at Quebec on the St. Lawrence River. His Indian allies and suppliers—the Montagnais and Algonquin—demanded that he help them against their enemies, the Iroquois, who lived to the south. In 1609, Champlain and nine French soldiers joined their Indian allies’ raiding party. Reaching the lake now named for Champlain, they attacked an Iroquois encampment there. Shocked by the French firearms, which killed three chiefs, the Iroquois broke and fled.

This engraving styled after a 1609 sketch by Samuel de Champlain depicts the battle between the Iroquois and Algonquian tribes. Note the presence of the French armed with guns.

The French advantage proved short-lived, for the Iroquois soon obtained their own guns from Dutch traders who settled along the Hudson River. With their new weapons, the Iroquois raided French settlements and the villages of their Indian allies. In pursuit of fur-trade profits, the French became entangled in complicated Indian alliances and enmities. At the same time, the fur trade escalated the warfare between Indian nations to unprecedented levels of bloodshed and destruction. (See The Oral Tradition of the Foundation of the Iroquois Confederacy Primary Source.)

The English and the Atlantic Coast

While the Spanish dominated the southern part of North America and the French focused their efforts on northern waters, the intervening Atlantic coast became, by default, the target of English colonizers. The English named the region “Virginia,” after Queen Elizabeth I, the “Virgin Queen” who never married. In 1587, English adventurers built their first American settlement on Roanoke, a sandy island within the Outer Banks of present-day North Carolina. Raising too few crops, they relied on taking food from the local Indians. Within a few years, the colony mysteriously disappeared, though historians are not sure whether by assimilation with the Croatan tribe or by a devastating attack. (See the Watercolors of Algonquian Peoples in North Carolina 1585 Primary Source.)

n 1607, the English tried again, a bit farther north at the Chesapeake Bay, which offered better harbors, navigable rivers, and fertile land. The Virginia Company, an entrepreneurial joint-stock company, erected a settlement at Jamestown beside the James River, both places named for the new king of England, James I. One of its leaders was John Smith, bold and dashing despite his humble origins in England, who claimed the Indian Pocahontas had saved him from execution by her father, a powerful chief named Powhatan.

John Smith included an image of his encounter with Powhatan on a map of Virginia drawn in 1622. The caption beneath the image reads: “Powhatan held this state & fashion when Capt. Smith was delivered to him prisoner 1607.”

Repeating the mistake of Roanoke, however, the Jamestown colonists worked too little at raising crops, perhaps because Smith and the other leaders required them to tend communal fields where shirking was widespread. The colony’s ever-changing succession of leaders also ordered them to hunt for gold and seize food from the Indians. As a result, the newcomers suffered from hunger, disease, and violence wrought by Indians led by Powhatan. When a new governor, Thomas Dale, arrived in 1611, he observed untended communal fields, only “some few seeds put into a private garden or two,” and the inhabitants engaged in “their daily and usuall workes, bowling in the streets.” He introduced martial law, which further impinged upon the liberties of the colonists. The subsequent introduction of private property on which they would grow their own food met with considerable success, however. As settler Ralph Hamor observed in 1615, “When our people were fedde out of the common store and laboured jointly in the manuring of the ground, and planting corne, glad was that man that could slippe from his labour, nay the most honest of them in a generall businese, would take so much faithfull and true paines, in a weeke, as now he will doe in a day.”

Conditions slowly improved during the 1610s, thanks in part to the efforts of an especially enterprising colonist named John Rolfe. In 1614, Rolfe married Pocahontas a union that diminished hostilities between her people and the English, just as marriages among European royalty cemented diplomatic relations between families and nations. Taking the name “Rebecca” and embracing Christianity, Pocahontas went to England with Rolfe on a promotional tour to raise money for the colony. Her presence, in fine European clothing, suggested the English would succeed in converting the natives. Her capture and conversion also persuaded her elderly and weary father to suspend his war against the Virginia colony. But in 1617, at the age of just 21 years, Pocahontas died of disease in England.

This 1616 engraving by Simon van de Passe, completed when Pocahontas and John Rolfe were presented at court in England, is the only known contemporary image of Pocahontas, then known as Rebecca. Note her European garb and pose. What message did the artist likely intend to convey with this portrait of Pocahontas, the daughter of a powerful Indian chief?

Rolfe also promoted the cultivation of a promising new crop: tobacco. Although worthless as food, the plant was mildly intoxicating and highly addictive after being dried and cured so it could be smoked. After Rolfe developed milder strains of the plant, the English began to crave tobacco, which grew better in the Virginia heat than in the cool climate of Britain. By 1624, Virginia had produced 200,000 pounds of tobacco. Fourteen years later, that production had soared to three million pounds. Profits from tobacco and greater opportunity attracted more immigrants to the Virginia colony. From only 350 people in 1616, its numbers had swelled to thirteen thousand by 1650. Most arrived as poor young men who signed an indenture or labor contract to work for wealthy landowners for a set period in return for their passage, food, clothing, and lodging. Settlers also often earned land, transferred to them from planters who received it through the “headright system,” which rewarded those who brought Englishmen to Virginia and thereby saved the Virginia Company, and later the Crown, the expense of populating the colony. The terms of the settlers’ “indentured servitude” typically lasted at least four years. Indentured servants gambled their lives on an unhealthy climate. If they survived their terms, they would obtain land and buy their own servants. Starting in 1619, an occasional shipment of enslaved Africans arrived to provide another source of labor for those who could afford to buy them. Initially, the colonists treated some of the Africans as indentured servants, who also became free at the end of their terms. Free black people were not an uncommon sight in the first few decades of settlement; some African-born Virginians owned their own land and the labor of English indentured servants and African slaves. In the aftermath of Bacon’s Rebellion (1676), Virginia increasingly switched its labor force from indentured servants to African slaves, as greater opportunity in England reduced the supply of indentures and the growing Atlantic slave trade expanded the supply of Africans. Over the course of the century, however, the colonists increasingly treated the Africans as lifelong slaves who were forced to pass that status on to their children.

This eighteenth-century English advertisement for Virginia tobacco (“Martin’s Best Virginia at the Tobacco Role in Bloomsbury Market”) shows black children working on a tobacco plantation in Virginia. What does the presence of children working the tobacco fields reveal about slavery in the colony by the 1700s?

The colony’s early years took a grisly toll. Between 1607 and 1622, about ten thousand colonists settled in Virginia, but only a fifth were still alive in 1622 when their Indian neighbors launched a massacre that had left 347 Englishmen dead by day’s end. A critic declared that the colony had become “a slaughterhouse.” The death rate exceeded the birth rate in Virginia throughout the seventeenth century because of the unhealthy Tidewater climate and prevalence of disease. (See The Anglo-Powhatan War of 1622 Narrative.)

Yet the English had come to Virginia to stay, to the dismay of the Indians, whose numbers also decreased as a result of war and disease. However, the king took control of the colony because the Virginia Company could not handle the problems with the Indian population or the discontent of the settlers. Moreover, an investigation revealed the shocking mortality rates. Thereafter, the crown appointed a governor who had to cooperate with the New World’s earliest elected legislature, known as the House of Burgesses. This body first convened in Jamestown in the summer of 1619, only a few days before the first ship carrying enslaved Africans arrived at a dock a few hundred feet away. These conflicting visions of democracy and slavery continued to shape America. (See the Origins of the Slave Trade Narrative.)

n the 1620s, the English developed another set of colonies, known as “New England,” farther north along the coast (and beyond the small Dutch colony of New Netherland on the Hudson River). A colder, rockier land, New England was less promising for cultivating crops for export to England. A group called the Pilgrims was the first to arrive there in 1620. The Pilgrims were separatists who believed the Church of England was irredeemable and saw no other solution but to leave the Church and the country. After a brief stay in Holland, the Pilgrims eventually set sail for the New World and settled just north of Cape Cod in the town of Plymouth. According to their governor, William Bradford, they “fell upon their knees and blessed the God of Heaven, who had brought them over the vast and furious ocean, and delivered them from all the perils and miseries thereof, again to set their feet on the firm and stable earth.” In signing the Mayflower Compact, they agreed to cooperate and write just laws. The region also attracted colonists who adhered to a purist form of Protestant Christianity, which had led their critics at home in England to call them “Puritans.” The Puritans felt persecuted by the English government and troubled by the immoralities they detected in England. They were a hard-working as well as a moralistic people. One Puritan preached, “God sent you unto this world as unto a Workhouse, not a Playhouse.” While most Puritans stayed behind in England, thousands went to New England during the 1630s to establish a model society governed by their understanding of the Bible. They expected that such a “Bible Commonwealth” would prosper and inspire the people back in England to copy their example—as Governor John Winthrop put it, to be “a city upon a hill,” a phrase he borrowed from the Book of Matthew. (See the A City Upon a Hill: Winthrop’s “Modell of Christian Charity ” 1630 Primary Source.)

(a) In the 1629 seal of the Massachusetts Bay Colony an Indian is shown asking colonists to “Come over and help us.” This seal indicates the religious ambitions of (b) John Winthrop, the colony’s first governor, for his “city upon a hill.”