An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMJ Glob Health

- v.6(1); 2021

Abortion metrics: a scoping review of abortion measures and indicators

Veronique filippi.

1 London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Faculty of Epidemiology and Population Health, London, UK

Mardieh Dennis

Clara calvert, Özge tunçalp.

2 Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research, UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), WHO, Geneva, Switzerland

Bela Ganatra

Caron rahn kim, carine ronsmans, associated data.

bmjgh-2020-003813supp001.pdf

bmjgh-2020-003813supp002.pdf

Consensus is lacking on the most appropriate indicators to document progress in safe abortion at programmatic and country level. We conducted a scoping review to provide an extensive summary of abortion indicators used over 10 years (2008–2018) to inform the debate on how progress in the provision and access to abortion care can be best captured. Documents were identified in PubMed and Popline and supplemented by materials identified on major non-governmental organisation websites. We screened 1999 abstracts and seven additional relevant documents. Ultimately, we extracted information on 792 indicators from 142 documents. Using a conceptual framework developed inductively, we grouped indicators into seven domains (social and policy context, abortion access and availability, abortion prevalence and incidence, abortion care, abortion outcomes, abortion impact and characteristics of women) and 40 subdomains. Indicators of access and availability and of the provision of abortion care were the most common. Indicators of outcomes were fewer and focused on physical health, with few measures of psychological well-being and no measures of quality of life or functioning. Similarly, there were few indicators attempting to measure the context, including beliefs and social attitudes at the population level. Most indicators used special studies either in facilities or at population level. The list of indicators (in online supplemental appendix) is an extensive resource for the design of monitoring and evaluation plans of abortion programmes. The large number indicators, many specific to one source only and with similar concepts measured in a multitude of ways, suggest the need for standardisation.

Key questions

What is already known.

- Recent decades have seen progress in the delivery of safe abortion services.

- However, consensus is lacking on the most appropriate measures or indicators to document progress at programmatic and country level.

- A recent systematic review has identified 75 indicators of abortion quality subdivided into structure, process and outcomes indicator.

What are the new findings?

- We extracted information on 792 indicators, many specific to one source only.

- Indicators of access and availability and of the provision of abortion care were the most common.

- Indicators of outcomes focused on physical health, with few measures of psychological well-being and no measures of quality of life or functioning.

- There were few indicators attempting to measure the context, including beliefs and social attitudes at the population level.

- The majority of indicators used special studies either in facilities or at population level.

What do the new findings imply?

- The large number indicators, with similar concepts measured in a multitude of ways, suggest the need for standardisation.

- Areas of further development include population-based indicators of effective coverage and standardised indicators of well-being and respectful care.

Introduction

Improving women’s reproductive health and rights is essential to achieving the sustainable development goals. Recent decades have seen progress in the delivery of safe abortion services. The development of medical abortion, for example, is a relatively recent technology which can allow women to access abortion at home or in primary healthcare services. However, many social, economic, health service and policy factors continue to affect women’s ease of access to comprehensive abortion services. Modelled estimates suggest that 56 million women had an abortion annually between 2010 and 2014, and 25 million of these were classified as less or least safe. 1 Abortion complications therefore continue to be an important cause of maternal death globally, with 22 800 women dying from these every year. 2

Researchers and evaluators support public health efforts to improve women’s reproductive health and rights by monitoring progress, 3 documenting women’s reproductive health needs, 4 conducting implementation research 5 and testing novel approaches to improve access to quality abortion care services in experimental or quasi-experimental studies. 6 7 Measuring accurately the interventions or care provided, how and in which context women in need access them, and their impact on health and other outputs or outcomes is essential to improve the evidence base, to enhance the implementation of safe abortion programmes and to track progress in reducing unsafe abortions.

Measures and indicators are key ingredients for research and evaluation. The terminology measures refers to numbers or quantities, whereas indicators are more specific time-bound measures or statements that are used to establish targets or demonstrate changes following programmatic or public health interventions. While there have been efforts to refine and standardise the methodology around capturing the incidence of abortion, 8 9 and measuring access to, delivery of, and quality of abortion care, 10 consensus on the most appropriate measures or indicators is lacking and there are gaps in ‘practical’ implementation metrics. 11 For example, different sets of abortion indicators are used or have been proposed by international non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and other international actors such as MEASURE Evaluation. As part of its coordinating role in establishing standards, the WHO published a technical document on national-level monitoring for achievement of universal access to reproductive health, proposing related indicators of safe abortion care that countries are encouraged to report within the context of monitoring national reproductive and maternal health programmes. 9 12 Consequently, the WHO safe abortion guidelines included 11 indicators for monitoring access and outcomes and noted 21 other issues to consider for periodic assessment grouped into access to safe abortion services, availability of safe abortion and quality of care. 9 However, these guidelines do not provide further details on indicators that sexual and reproductive health programmes might use to evaluate the success of their interventions in these 21 areas.

A recent systematic review of three databases and grey literature has since identified 75 indicators of ‘abortion quality’ subdivided into structure, process and outcomes indicators. 10 Following on this review, the objective of this paper is to provide a broader and more extensive summary of relevant abortion measures and indicators used over 10 years in the published scientific literature. Our aim is to inform and enlarge the debate on how progress in the provision and access to abortion care can be best captured.

Study design

We undertook a scoping review rather than a systematic review as we anticipated that the primary studies reporting abortion measures and indicators were likely to be very broad in their scope. The methods for the review were informed by a framework developed for scoping reviews. 13 This paper follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines for reporting on systematic reviews.

Patient and public involvement statement

Abortion patients and the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of our scoping review.

Search strategy

We searched two databases (PubMed and Popline) on 10 August 2018. The full search strategy is provided in online supplemental appendix 1 , covering free-text and MESH terms for “abortion”, combined with free-text and MESH terms for “measurements” and “indicator”. We consulted websites of international NGOs and associations working on women’s reproductive rights for additional data. We included information that was available on the websites at the time of our search, regardless of when it was originally published.

Supplementary data

Document selection and data extraction.

We included studies and NGO documents reporting abortion-related measures or indicators that captured various domains relevant to reproductive health programmes such as abortion policies, access or availability, prevalence or incidence, quality of care, or health outcomes. In the rest of this paper, we will use the terminology ‘indicators’ throughout, unless otherwise necessary. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were published within a 10-year period, from the beginning of 2008, and were conducted within health facilities or at the population level (ie, regionally or nationally representative), with the aim of measuring changes, success or progress or assessing programmatic needs. We focus on the 10 recent years only, as there have been major changes in the way abortion is perceived, and in the abortion methods and techniques. Study designs included cross-sectional studies, intervention studies, time series and cohort studies. Policy studies, NGOs’ monitoring and evaluation documents and methodological papers that reported on new indicators were also included. We did not exclude any articles, documents or websites based on language during title and abstract screening; however, full review was only conducted for papers written in English or French. We did not assess study quality.

Titles and abstracts were screened by one reviewer (MD and VF), with 10% double screened to assess concordance. Potentially relevant papers were read in full by one reviewer (MD) and were checked again by VF and CC to verify that they met the inclusion criteria. Data were extracted into Excel if the publication was deemed relevant. The type of data extracted depended on whether the paper identified a new indicator, which had not yet been identified through the review of full texts, or whether we had already captured the indicator from another study. For new indicators, we extracted the name of the indicator, what it measures (eg, women’s satisfaction with abortion care), a description of the numerator and the denominator (where relevant) and data sources. For a few indicators, which were qualitative in nature (such as description of regulation availability), we included the descriptive statement in place of the numerator. If the indicator had already been extracted from another full-text, the details already extracted were checked, and the new reference was added to the list of studies using that indicator. Where a description of an indicator was provided, but the indicator appeared aspirational and untested, with no source of empirical data provided, we left the description of the data sources empty. 14

Data synthesis

Data synthesis was conducted using the steps suggested by Arskey and O’Malley, covering preparation of an analytical framework, numerical analysis on the extent and nature of studies, and thematic analysis. 15 Once data extraction was completed, we grouped indicators according to a conceptual framework, which was developed inductively by bringing indicators into thematic groups. Several existing frameworks were also consulted, including one of which was proposed by Taylor and colleagues 16 and one by Bryce and colleagues. 17 According to our framework, indicators were classified into one of seven mutually exclusive groups, ranging from abortion access and availability through to the health impact of abortion (eg, death). Although family planning is a crucial intervention to prevent unwanted pregnancy, family planning indicators were only included in the context of post-abortion care and number of abortions averted.

After grouping the indicators, all authors met and reviewed the list of indicators and their groupings, agreeing the most appropriate group for certain indicators when there was uncertainty, and standardising the terminology across indicators. We then counted the number of indicators in each category of the conceptual framework as well as the number of indicators using each data source. We also counted the number of times an indicator was reported in more than one document.

Figure 1 shows the process of selecting studies. A total of 1999 abstracts were identified from the search of the two databases. Most of these were excluded after reviewing the title and abstract (N=1782); no additional articles were identified for inclusion based on double screening a 10% sample by a second reviewer. All included documents in this paper were in English. There are nine scientific papers for which we did not conduct a full review because they were not in English or French. Of the 199 articles for which the full text was obtained and reviewed, 135 were identified as relevant for this review. Additionally, through the search of websites, seven relevant documents were added. Ultimately, we extracted information on 792 indicators from 142 documents (add online weblink/see online supplemental appendix 2 ).

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram for the scoping review.

The conceptual framework, developed as part of the review, alongside the number of indicators extracted for each domain of the conceptual framework is shown in figure 2 . Indicators could be grouped in seven different domains as follows: (1) social and policy context (including attitudes and beliefs among women and the population, stigma and laws and regulations); (2) abortion access and availability (including signal functions); (3) abortion prevalence and incidence; (4) safe abortion and post-abortion care (ie, measures of quality of care, including clinical and respectful care); (5) abortion outcomes (including adverse events, near-miss and other physical or psychological complications for women using services); (6) abortion impact on health (ie, measures of disabilities and mortality at the population level; indicators of financial impact appear in access and availability) and (7) characteristics of women who have abortion and with abortion outcomes.

Conceptual framework for scoping review, with numbers of indicators for seven domains and forty subdomains (NB: domain 3 has two sub-domains for which results have been combined in this figure).

Using a logical model design, the conceptual model represents how access to and availability of services, and care provided, can lead to health outcomes in individual women or impact on mortality and morbidity at the population level, considering the influences of context and women’s characteristics. In this framework, the arrow between ‘abortion access and availability’ and ‘abortion prevalence and incidence’ is used to capture the complex relationship between these domains, whereby in some contexts the frequency of abortion will drive the availability of services, while in other contexts the availability of services may lead to an increase in the frequency of abortion. Each of these seven domains is then further divided into subcategories as presented in figure 2 . For example, abortion care has the largest number of subcategories (N=13), followed by abortion access and availability (N=8) and abortion care (N=7), reflecting perhaps the large number of indicators in these domains.

There were 225, 206 and 150 indicators related to abortion access and availability, abortion care and abortion outcomes (adverse events/morbidity/psychological well-being), respectively. There were far fewer indicators looking at the social and policy context or measuring abortion incidence/prevalence or impact (67, 28 and 18, respectively). In addition, 98 indicators covered the characteristics of women who used abortion care or for whom abortion outcomes were documented (53 for demographic and reproductive characteristics; 11 for reasons for abortion; 20 for socioeconomic characteristics and 14 for women’s knowledge and perception). Most of the indicators in this group were not population based. There were no indicators of the consequences of being denied a termination of pregnancy, such as household poverty.

Details of each of the 792 indicators, including the definition of the numerator and denominator and data sources can be found in the online weblink (see online supplemental appendix 2 ). Table 1 provides a summary of the number of indicators within each domain captured by each different type of data source. For example, the majority of indicators on abortion access and availability were calculated using health provider surveys (N=114, 56% of indicators in this domain). In contrast, facility records/ Health Management Information System (HMIS) data (N=19, 70%) and population survey/census (N=13, 48%) were the predominant sources of data for abortion incidence and prevalence. Facility-based records and health information management systems were a moderately common data source, used for 211 indicators overall. However, all the remaining indicators relied on data sources requiring special studies either in facilities or at population level. Of these, client exit interviews were the most common data source (N=180) and, despite their potential to provide representative data, population-based surveys and censuses were among the least used data sources (N=99).

Number of abortion indicators obtained according to data sources, 2008–2018 (N=760*)

Some indicators are measured with more than one sources.

*32 aspirational indicators, for which a data source was not proposed, are excluded from this table.

†Total in column, not row which includes double counting (953 count).

HMIS, Health Management Information System.

Finally, many indicators were specific to a particular data collection approach (eg, attitudes of health providers obtained in provider surveys), 18 a type of intervention (indicators of clinical management obtained in clinical audits or the evaluation of a clinical intervention) 19 or a context (measures of emotional or psychological well-being only found in studies conducted in high-income country contexts). 20 Some appear limited to specific authors or institutions, as they developed methodologies suited to their own purpose. Less than a quarter of indicators were proposed by multiple sources, as shown in our weblink (N=175; 22%). These included most indicators in the prevalence and incidence category (19 out of 28).

In this scoping review of 10 years of published literature, we found a very large number of abortion-related indicators, with less than a quarter proposed or used by more than one source. Indicators of access and availability and of the provision of abortion care were by far the most common. Indicators of outcomes were fewer and less comprehensive as they very much focused on physical health, with few measures of psychological well-being and no measures of quality of life or functioning. Similarly, there were few indicators attempting to measure the context, including beliefs and social attitudes at the population level. These indicators of knowledge and ‘demand’ for reproductive health services are however important to ensure speedy access to safe abortion services when needed. 21

We conducted a comprehensive scoping review of published papers. Our search and screening strategies were designed to be sensitive. We included all research papers that focus on documenting changes including assessing the success or progress of abortion programmes or interventions, supplemented by programme documents that were specific to monitoring and evaluation and could be found online on the website of key NGOs and some governmental agencies active in sexual and reproductive health. Our scoping review is broader compared with the review conducted by Dennis and colleagues, 10 since we went beyond quality of care and monitoring and evaluation, and consequently we identified over ten times as many indicators (792 vs 75). Our online list of indicators provides a rich resource for abortion programmes and research projects, enabling the selection of indicators that can be tailored to their own goals and objectives. Our list also includes examples of country level indicators that can measure the performance of health sector programmes in ensuring sexual and reproductive health, including for abortion services. 11 We have conducted this review as the first step in a multi-stage process for deriving a set of standardised indicators which can be used across reproductive health programmes in diverse settings.

Our review has some limitations. It is possible that screening criteria about what counts as a measure or an indicator of success or progress were different between the screeners. We did attempt to minimise this risk, by double screening a sample of studies and discussing the selection of indicators in detail during the standardisation process. The inductive process for building up the indicator conceptual framework was a subjective process, and another group of investigators may have classified the indicators differently. Although family planning is an important intervention to reduce deaths from unwanted pregnancies, our exclusion of papers that focused exclusively on family planning constitutes arguably another possible limitation. The MEASURE Evaluation website can be consulted for its extensive list of family planning and reproductive health indicators. 14 As we only included two databases and the grey literature available online from well-known international NGOs active in reproductive health and only two country reports from high-income countries (UK, USA), relevant documents may have been missed. In particular, we did not systematically search websites of national health management information systems for abortion indicators. Finally, we categorise indicators into only one of the domains in the conceptual framework; however, in many cases, indicators could have been categorised into several domains.

Due to the extensive number of indicators identified, it was beyond the scope of this project to provide an assessment of their suitability and robustness. Good indicators have several characteristics including validity, reliability, relevance, ease of measurement, actionability, comparability potential and responsiveness to change 22 as well as being based on evidence and acceptability. 23 Indeed, we found in our review that similar constructs are defined and measured in a myriad of ways, increasing the number of indicators without ensuring the use of validated and standardised measures. Moving forward, a more consistent understanding of validity can help guide prioritisation of indicators and development of new indicators where there is a validity gap identified. 24 It also allows standardisation enabling comparison across time and settings where these indicators are used.

Validation and standardisation have some uniquely important features for sexual and reproductive health indicators. Even though many such indicators are established, there are measurement difficulties specific to induced abortion related to the stigmatisation and restrictive nature of the procedure in some contexts, which will affect the data sources, validity, reliability and utilisation of the indicators depending on the setting, and therefore comparisons. For example, reporting bias can severely under-estimate the measurement of abortion incidence, abortion outcomes and abortion care utilisation with population survey approaches, explaining the under-utilisation of this data source. 8 It is difficult to distinguish when post-abortion care is provided to women with spontaneous abortion vs those with induced abortion in legally restrictive settings as information on induced abortion is often omitted or inaccurate in medical records and facility registers leading to misclassification. 25 Severe abortion complications are not always found in the gynaecological wards, 26 requiring investigators to screen records in emergency rooms and general intensive care units. Abortion-related deaths may not be reported. Women and their partners buy misoprostol and mifepristone ‘under the radar’ from licensed and unlicensed drugs sellers, community networks and increasingly online. This can limit the comparability of information over time and across settings for all types of indicators. Recent efforts to improve the usefulness of indicators or the utilisation of available data are multiple, and include for example, the development of approaches to measure the coverage of signal functions for abortion care at the population level through the use of multiple sources of data 27 28 and advanced statistical modelling to fill the gaps in information on unsafe abortion incidence. 1

Our scoping review results could be used by different stakeholders, including researchers and programme managers, to inform their own development of data collection tools for monitoring and evaluation of sexual and reproductive health programmes. Each indicator in our list was provided with one or several references to illustrate the use of the indicators. These results also aim to inform a future research agenda on abortion indicators measurement. While our list of indicators is extensive, there remains a need in some areas to develop or test new indicators: for example, to broaden the type of health outcome indicators for abortion to quality of life and functioning; to respond to the challenge of collecting valid data in the community as the provision of abortion care is shifting to community-based distribution of medical abortion; to standardise indicators, in particular those that are morbidity related 29 ; to measure performance of the health sector 11 and to align with other initiatives on effective coverage 30 and health system strengthening monitoring. 31 Comprehensive measurement of patient-centred indicators, such as women’s experience of care is also required. 32

The list of indicators identified in this paper provides a good ‘starting point’ and an extensive resource for the design of monitoring and evaluation plans of abortion programmes. 33 The large number of indicators, with similar concepts measured in a multitude of overlapping ways, suggest a need for further investigation on their validity and for standardisation. This is especially needed for when the measurement intention is a comparison over time or between settings. In particular, a smaller set of standardised and prioritised indicators may be required for tracking global trends, monitoring the implementation of guidelines at the country level or comparing success across programmes and countries. Areas of further development include population-based indicators of effective coverage and standardised indicators of well-being and respectful care.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Louise Skrzypczak for her help with identifying and screening articles. We thank Dr Onikepe Owolabi for the feedback she provided on our initial findings. We are pleased to acknowledge DFID for their financial support under the WHO grant 'Improving Accountability for Sexual and Reproductive Health for the young, the poorest and those in crisis'.

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @1verofilippi, @MardiehD, @otuncalp

Contributors: CC and MD wrote the first draft of the scoping review protocol with inputs from VF and CR and comments from BG and OT. MD screened and extracted most papers, on a spreadsheet she designed, with inputs from VF and CC. MD and CC wrote the first draft of the final conceptual framework. All authors discussed the findings (presentation, grouping, meaning). VF wrote the first draft of the paper, together with CC, and she led on revisions of subsequent drafts. All authors commented and/or added text on all drafts.

Funding: Department for International Development WHO grant “Improving Accountability for Sexual and Reproductive Health for the young, the poorest and those in crisis".

Disclaimer: The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information as indicated in the article.

In addition to the online supplemental appendix 2, a fully searchable online spreadsheet with the full list of indicators is also available by contacting directly the authors at WHO or LSHTM, or by accessing the website of the maternal and newborn health group at LSHTM: https://mnhgroup.lshtm.ac.uk/maternal-health-team/

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

2. social and moral considerations on abortion.

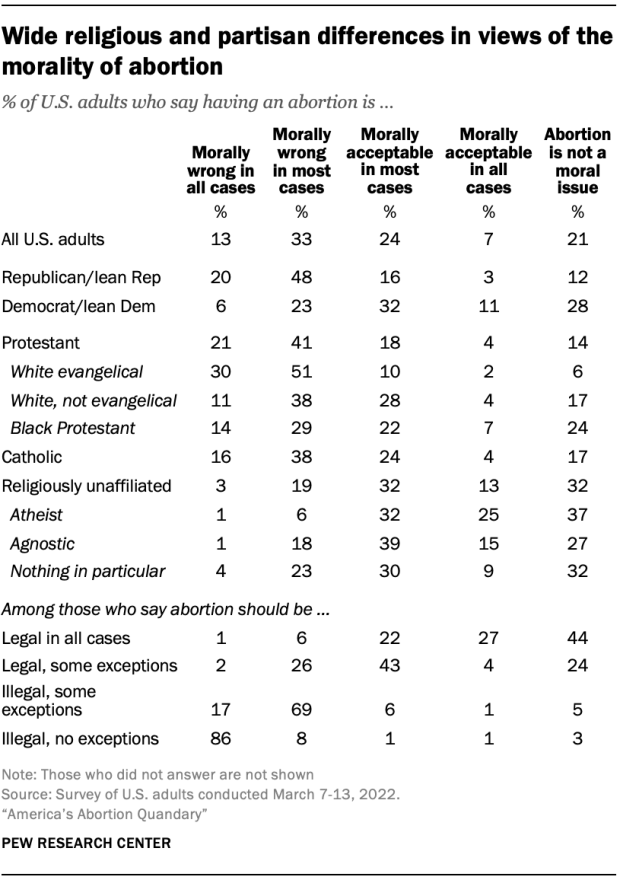

Relatively few Americans view the morality of abortion in stark terms: Overall, just 7% of all U.S. adults say abortion is morally acceptable in all cases, and 13% say it is morally wrong in all cases. A third say that abortion is morally wrong in most cases, while about a quarter (24%) say it is morally acceptable most of the time. About an additional one-in-five do not consider abortion a moral issue.

There are wide differences on this question by political party and religious affiliation. Among Republicans and independents who lean toward the Republican Party, most say that abortion is morally wrong either in most (48%) or all cases (20%). Among Democrats and Democratic leaners, meanwhile, only about three-in-ten (29%) hold a similar view. About four-in-ten Democrats say abortion is morally acceptable in most (32%) or all (11%) cases, while an additional 28% say abortion is not a moral issue.

White evangelical Protestants overwhelmingly say abortion is morally wrong in most (51%) or all cases (30%). A slim majority of Catholics (53%) also view abortion as morally wrong, but many also say it is morally acceptable in most (24%) or all cases (4%), or that it is not a moral issue (17%). And among religiously unaffiliated Americans, about three-quarters see abortion as morally acceptable (45%) or not a moral issue (32%).

There is strong alignment between people’s views of whether abortion is morally wrong and whether it should be illegal. For example, among U.S. adults who take the view that abortion should be illegal in all cases without exception, fully 86% also say abortion is always morally wrong. The prevailing view among adults who say abortion should be legal in all circumstances is that abortion is not a moral issue (44%), though notable shares of this group also say it is morally acceptable in all (27%) or most (22%) cases.

Most Americans who say abortion should be illegal with some exceptions take the view that abortion is morally wrong in most cases (69%). Those who say abortion should be legal with some exceptions are somewhat more conflicted, with 43% deeming abortion morally acceptable in most cases and 26% saying it is morally wrong in most cases; an additional 24% say it is not a moral issue.

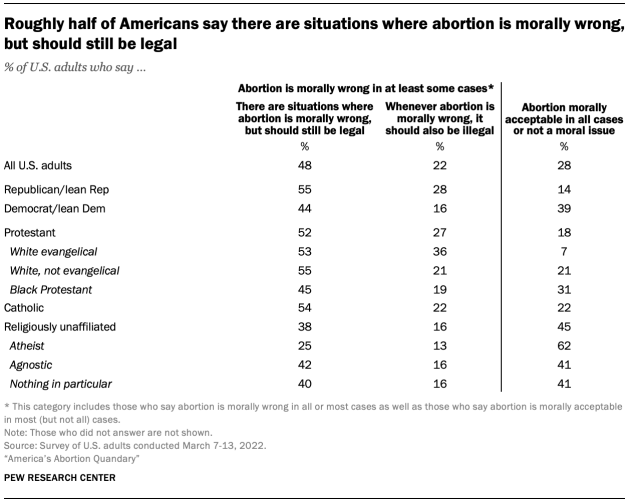

The survey also asked respondents who said abortion is morally wrong in at least some cases whether there are situations where abortion should still be legal despite being morally wrong. Roughly half of U.S. adults (48%) say that there are, in fact, situations where abortion is morally wrong but should still be legal, while just 22% say that whenever abortion is morally wrong, it should also be illegal. An additional 28% either said abortion is morally acceptable in all cases or not a moral issue, and thus did not receive the follow-up question.

Across both political parties and all major Christian subgroups – including Republicans and White evangelicals – there are substantially more people who say that there are situations where abortion should still be legal despite being morally wrong than there are who say that abortion should always be illegal when it is morally wrong.

Public views of what would change the number of abortions in the U.S.

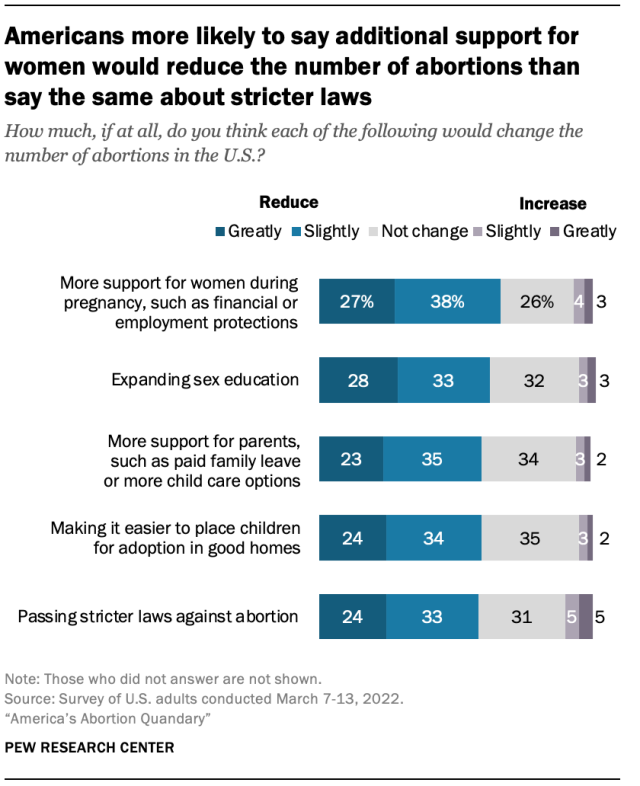

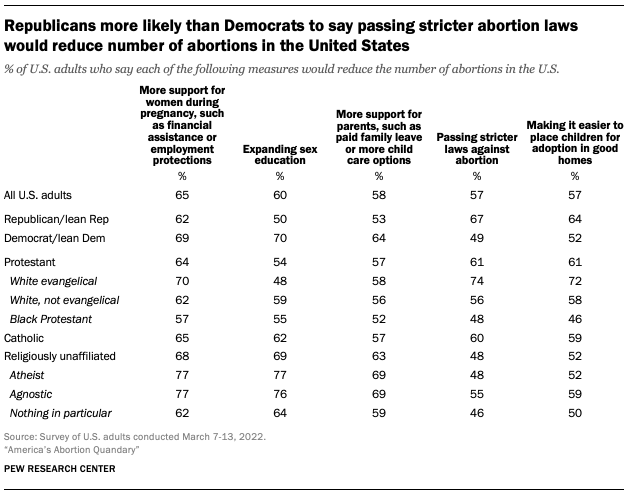

Asked about the impact a number of policy changes would have on the number of abortions in the U.S., nearly two-thirds of Americans (65%) say “more support for women during pregnancy, such as financial assistance or employment protections” would reduce the number of abortions in the U.S. Six-in-ten say the same about expanding sex education and similar shares say more support for parents (58%), making it easier to place children for adoption in good homes (57%) and passing stricter abortion laws (57%) would have this effect.

While about three-quarters of White evangelical Protestants (74%) say passing stricter abortion laws would reduce the number of abortions in the U.S., about half of religiously unaffiliated Americans (48%) hold this view. Similarly, Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say this (67% vs. 49%, respectively). By contrast, while about seven-in-ten unaffiliated adults (69%) say expanding sex education would reduce the number of abortions in the U.S., only about half of White evangelicals (48%) say this. Democrats also are substantially more likely than Republicans to hold this view (70% vs. 50%).

Democrats are somewhat more likely than Republicans to say support for parents – such as paid family leave or more child care options – would reduce the number of abortions in the country (64% vs. 53%, respectively), while Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say making adoption into good homes easier would reduce abortions (64% vs. 52%).

Majorities across both parties and other subgroups analyzed in this report say that more support for women during pregnancy would reduce the number of abortions in America.

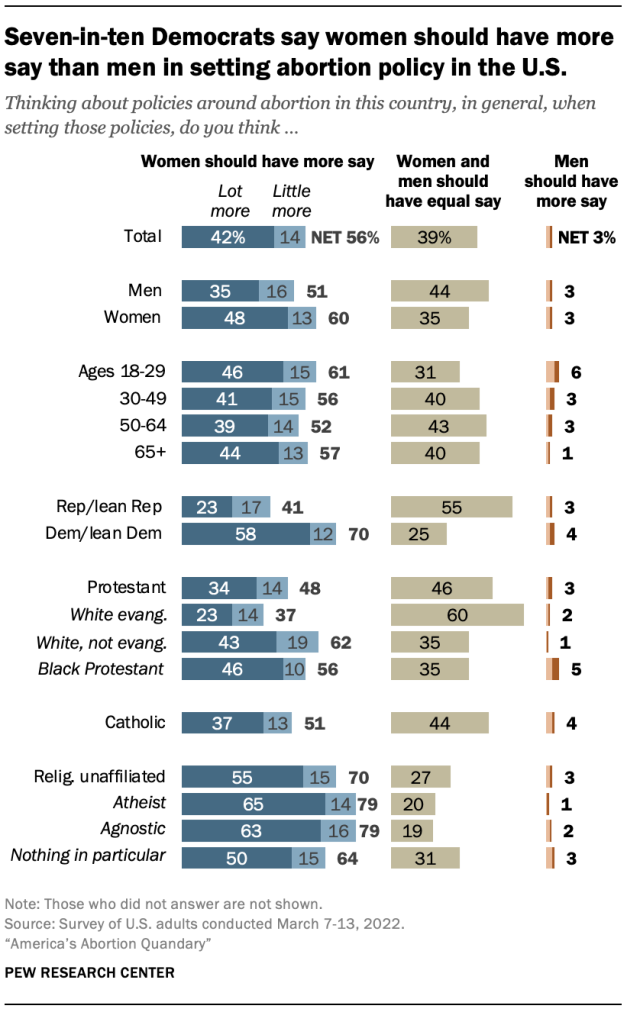

A majority of Americans say women should have more say in setting abortion policy in the U.S.

More than half of U.S. adults (56%) say women should have more say than men when it comes to setting policies around abortion in this country – including 42% who say women should have “a lot” more say. About four-in-ten (39%) say men and women should have equal say in abortion policies, and 3% say men should have more say than women.

Six-in-ten women and about half of men (51%) say that women should have more say on this policy issue.

Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to say women should have more say than men in setting abortion policy (70% vs. 41%). Similar shares of Protestants (48%) and Catholics (51%) say women should have more say than men on this issue, while the share of religiously unaffiliated Americans who say this is much higher (70%).

How do certain arguments about abortion resonate with Americans?

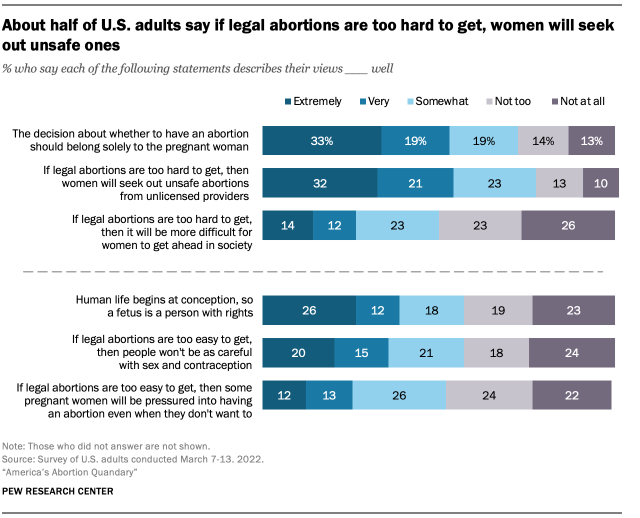

Seeking to gauge Americans’ reactions to several common arguments related to abortion, the survey presented respondents with six statements and asked them to rate how well each statement reflects their views on a five-point scale ranging from “extremely well” to “not at all well.”

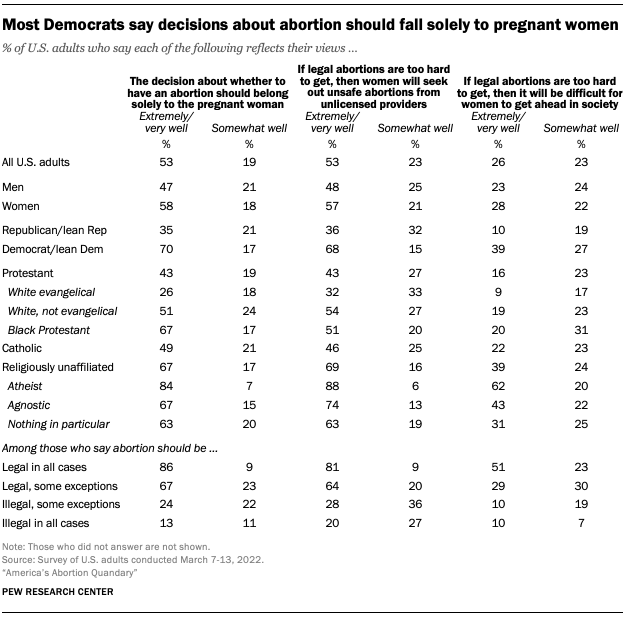

The list included three statements sometimes cited by individuals wishing to protect a right to abortion: “The decision about whether to have an abortion should belong solely to the pregnant woman,” “If legal abortions are too hard to get, then women will seek out unsafe abortions from unlicensed providers,” and “If legal abortions are too hard to get, then it will be more difficult for women to get ahead in society.” The first two of these resonate with the greatest number of Americans, with about half (53%) saying each describes their views “extremely” or “very” well. In other words, among the statements presented in the survey, U.S. adults are most likely to say that women alone should decide whether to have an abortion, and that making abortion illegal will lead women into unsafe situations.

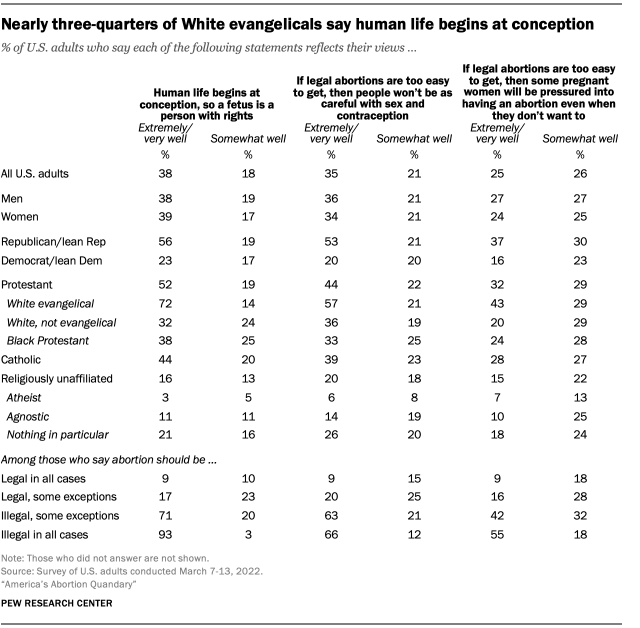

The three other statements are similar to arguments sometimes made by those who wish to restrict access to abortions: “Human life begins at conception, so a fetus is a person with rights,” “If legal abortions are too easy to get, then people won’t be as careful with sex and contraception,” and “If legal abortions are too easy to get, then some pregnant women will be pressured into having an abortion even when they don’t want to.”

Fewer than half of Americans say each of these statements describes their views extremely or very well. Nearly four-in-ten endorse the notion that “human life begins at conception, so a fetus is a person with rights” (26% say this describes their views extremely well, 12% very well), while about a third say that “if legal abortions are too easy to get, then people won’t be as careful with sex and contraception” (20% extremely well, 15% very well).

When it comes to statements cited by proponents of abortion rights, Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to identify with all three of these statements, as are religiously unaffiliated Americans compared with Catholics and Protestants. Women also are more likely than men to express these views – and especially more likely to say that decisions about abortion should fall solely to pregnant women and that restrictions on abortion will put women in unsafe situations. Younger adults under 30 are particularly likely to express the view that if legal abortions are too hard to get, then it will be difficult for women to get ahead in society.

In the case of the three statements sometimes cited by opponents of abortion, the patterns generally go in the opposite direction. Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say each statement reflects their views “extremely” or “very” well, as are Protestants (especially White evangelical Protestants) and Catholics compared with the religiously unaffiliated. In addition, older Americans are more likely than young adults to say that human life begins at conception and that easy access to abortion encourages unsafe sex.

Gender differences on these questions, however, are muted. In fact, women are just as likely as men to say that human life begins at conception, so a fetus is a person with rights (39% and 38%, respectively).

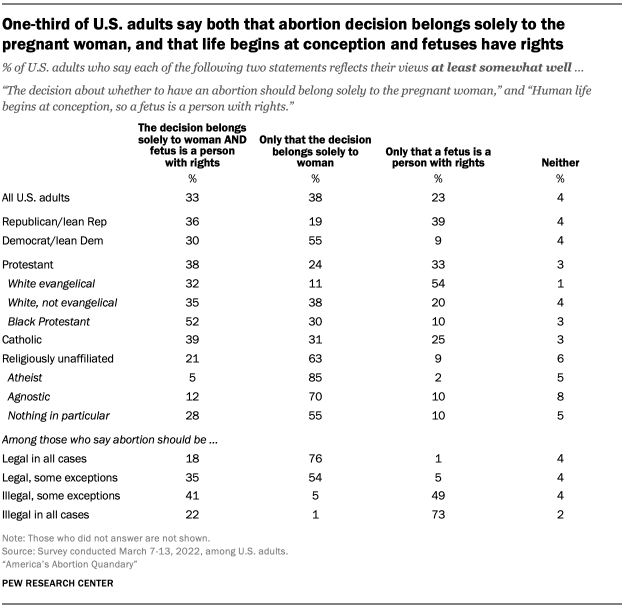

Analyzing certain statements together allows for an examination of the extent to which individuals can simultaneously hold two views that may seem to some as in conflict. For instance, overall, one-in-three U.S. adults say that both the statement “the decision about whether to have an abortion should belong solely to the pregnant woman” and the statement “human life begins at conception, so the fetus is a person with rights” reflect their own views at least somewhat well. This includes 12% of adults who say both statements reflect their views “extremely” or “very” well.

Republicans are slightly more likely than Democrats to say both statements reflect their own views at least somewhat well (36% vs. 30%), although Republicans are much more likely to say only the statement about the fetus being a person with rights reflects their views at least somewhat well (39% vs. 9%) and Democrats are much more likely to say only the statement about the decision to have an abortion belonging solely to the pregnant woman reflects their views at least somewhat well (55% vs. 19%).

Additionally, those who take the stance that abortion should be legal in all cases with no exceptions are overwhelmingly likely (76%) to say only the statement about the decision belonging solely to the pregnant woman reflects their views extremely, very or somewhat well, while a nearly identical share (73%) of those who say abortion should be illegal in all cases with no exceptions say only the statement about human life beginning at conception reflects their views at least somewhat well.

In their own words: How Americans feel about abortion

When asked to describe whether they had any other additional views or feelings about abortion, adults shared a range of strong or complex views about the topic. In many cases, Americans reiterated their strong support – or opposition to – abortion in the U.S. Others reflected on how difficult or nuanced the issue was, offering emotional responses or personal experiences to one of two open-ended questions asked on the survey.

One open-ended question asked respondents if they wanted to share any other views or feelings about abortion overall. The other open-ended question asked respondents about their feelings or views regarding abortion restrictions. The responses to both questions were similar.

Overall, about three-in-ten adults offered a response to either of the open-ended questions. There was little difference in the likelihood to respond by party, religion or gender, though people who say they have given a “lot” of thought to the issue were more likely to respond than people who have not.

Of those who did offer additional comments, about a third of respondents said something in support of legal abortion. By far the most common sentiment expressed was that the decision to have an abortion should be solely a personal decision, or a decision made jointly with a woman and her health care provider, with some saying simply that it “should be between a woman and her doctor.” Others made a more general point, such as one woman who said, “A woman’s body and health should not be subject to legislation.”

About one-in-five of the people who responded to the question expressed disapproval of abortion – the most common reason being a belief that a fetus is a person or that abortion is murder. As one woman said, “It is my belief that life begins at conception and as much as is humanly possible, we as a society need to support, protect and defend each one of those little lives.” Others in this group pointed to the fact that they felt abortion was too often used as a form of birth control. For example, one man said, “Abortions are too easy to obtain these days. It seems more women are using it as a way of birth control.”

About a quarter of respondents who opted to answer one of the open-ended questions said that their views about abortion were complex; many described having mixed feelings about the issue or otherwise expressed sympathy for both sides of the issue. One woman said, “I am personally opposed to abortion in most cases, but I think it would be detrimental to society to make it illegal. I was alive before the pill and before legal abortions. Many women died.” And one man said, “While I might feel abortion may be wrong in some cases, it is never my place as a man to tell a woman what to do with her body.”

The remaining responses were either not related to the topic or were difficult to interpret.

Sign up for our Religion newsletter

Sent weekly on Wednesday

Report Materials

Table of contents, majority of public disapproves of supreme court’s decision to overturn roe v. wade, wide partisan gaps in abortion attitudes, but opinions in both parties are complicated, key facts about the abortion debate in america, about six-in-ten americans say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, fact sheet: public opinion on abortion, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How the Right to Legal Abortion Changed the Arc of All Women’s Lives

By Katha Pollitt

I’ve never had an abortion. In this, I am like most American women. A frequently quoted statistic from a recent study by the Guttmacher Institute, which reports that one in four women will have an abortion before the age of forty-five, may strike you as high, but it means that a large majority of women never need to end a pregnancy. (Indeed, the abortion rate has been declining for decades, although it’s disputed how much of that decrease is due to better birth control, and wider use of it, and how much to restrictions that have made abortions much harder to get.) Now that the Supreme Court seems likely to overturn Roe v. Wade sometime in the next few years—Alabama has passed a near-total ban on abortion, and Ohio, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Missouri have passed “heartbeat” bills that, in effect, ban abortion later than six weeks of pregnancy, and any of these laws, or similar ones, could prove the catalyst—I wonder if women who have never needed to undergo the procedure, and perhaps believe that they never will, realize the many ways that the legal right to abortion has undergirded their lives.

Legal abortion means that the law recognizes a woman as a person. It says that she belongs to herself. Most obviously, it means that a woman has a safe recourse if she becomes pregnant as a result of being raped. (Believe it or not, in some states, the law allows a rapist to sue for custody or visitation rights.) It means that doctors no longer need to deny treatment to pregnant women with certain serious conditions—cancer, heart disease, kidney disease—until after they’ve given birth, by which time their health may have deteriorated irretrievably. And it means that non-Catholic hospitals can treat a woman promptly if she is having a miscarriage. (If she goes to a Catholic hospital, she may have to wait until the embryo or fetus dies. In one hospital, in Ireland, such a delay led to the death of a woman named Savita Halappanavar, who contracted septicemia. Her case spurred a movement to repeal that country’s constitutional amendment banning abortion.)

The legalization of abortion, though, has had broader and more subtle effects than limiting damage in these grave but relatively uncommon scenarios. The revolutionary advances made in the social status of American women during the nineteen-seventies are generally attributed to the availability of oral contraception, which came on the market in 1960. But, according to a 2017 study by the economist Caitlin Knowles Myers, “The Power of Abortion Policy: Re-Examining the Effects of Young Women’s Access to Reproductive Control,” published in the Journal of Political Economy , the effects of the Pill were offset by the fact that more teens and women were having sex, and so birth-control failure affected more people. Complicating the conventional wisdom that oral contraception made sex risk-free for all, the Pill was also not easy for many women to get. Restrictive laws in some states barred it for unmarried women and for women under the age of twenty-one. The Roe decision, in 1973, afforded thousands upon thousands of teen-agers a chance to avoid early marriage and motherhood. Myers writes, “Policies governing access to the pill had little if any effect on the average probabilities of marrying and giving birth at a young age. In contrast, policy environments in which abortion was legal and readily accessible by young women are estimated to have caused a 34 percent reduction in first births, a 19 percent reduction in first marriages, and a 63 percent reduction in ‘shotgun marriages’ prior to age 19.”

Access to legal abortion, whether as a backup to birth control or not, meant that women, like men, could have a sexual life without risking their future. A woman could plan her life without having to consider that it could be derailed by a single sperm. She could dream bigger dreams. Under the old rules, inculcated from girlhood, if a woman got pregnant at a young age, she married her boyfriend; and, expecting early marriage and kids, she wouldn’t have invested too heavily in her education in any case, and she would have chosen work that she could drop in and out of as family demands required.

In 1970, the average age of first-time American mothers was younger than twenty-two. Today, more women postpone marriage until they are ready for it. (Early marriages are notoriously unstable, so, if you’re glad that the divorce rate is down, you can, in part, thank Roe.) Women can also postpone childbearing until they are prepared for it, which takes some serious doing in a country that lacks paid parental leave and affordable childcare, and where discrimination against pregnant women and mothers is still widespread. For all the hand-wringing about lower birth rates, most women— eighty-six per cent of them —still become mothers. They just do it later, and have fewer children.

Most women don’t enter fields that require years of graduate-school education, but all women have benefitted from having larger numbers of women in those fields. It was female lawyers, for example, who brought cases that opened up good blue-collar jobs to women. Without more women obtaining law degrees, would men still be shaping all our legislation? Without the large numbers of women who have entered the medical professions, would psychiatrists still be telling women that they suffered from penis envy and were masochistic by nature? Would women still routinely undergo unnecessary hysterectomies? Without increased numbers of women in academia, and without the new field of women’s studies, would children still be taught, as I was, that, a hundred years ago this month, Woodrow Wilson “gave” women the vote? There has been a revolution in every field, and the women in those fields have led it.

It is frequently pointed out that the states passing abortion restrictions and bans are states where women’s status remains particularly low. Take Alabama. According to one study , by almost every index—pay, workforce participation, percentage of single mothers living in poverty, mortality due to conditions such as heart disease and stroke—the state scores among the worst for women. Children don’t fare much better: according to U.S. News rankings , Alabama is the worst state for education. It also has one of the nation’s highest rates of infant mortality (only half the counties have even one ob-gyn), and it has refused to expand Medicaid, either through the Affordable Care Act or on its own. Only four women sit in Alabama’s thirty-five-member State Senate, and none of them voted for the ban. Maybe that’s why an amendment to the bill proposed by State Senator Linda Coleman-Madison was voted down. It would have provided prenatal care and medical care for a woman and child in cases where the new law prevents the woman from obtaining an abortion. Interestingly, the law allows in-vitro fertilization, a procedure that often results in the discarding of fertilized eggs. As Clyde Chambliss, the bill’s chief sponsor in the state senate, put it, “The egg in the lab doesn’t apply. It’s not in a woman. She’s not pregnant.” In other words, life only begins at conception if there’s a woman’s body to control.

Indifference to women and children isn’t an oversight. This is why calls for better sex education and wider access to birth control are non-starters, even though they have helped lower the rate of unwanted pregnancies, which is the cause of abortion. The point isn’t to prevent unwanted pregnancy. (States with strong anti-abortion laws have some of the highest rates of teen pregnancy in the country; Alabama is among them.) The point is to roll back modernity for women.

So, if women who have never had an abortion, and don’t expect to, think that the new restrictions and bans won’t affect them, they are wrong. The new laws will fall most heavily on poor women, disproportionately on women of color, who have the highest abortion rates and will be hard-pressed to travel to distant clinics.

But without legal, accessible abortion, the assumptions that have shaped all women’s lives in the past few decades—including that they, not a torn condom or a missed pill or a rapist, will decide what happens to their bodies and their futures—will change. Women and their daughters will have a harder time, and there will be plenty of people who will say that they were foolish to think that it could be otherwise.

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Jia Tolentino

By Isaac Chotiner

By Jessica Winter

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Norms that can affect women’s abortion-related decisions and experiences include the primacy of procreation and motherhood for women, 3 cultural expectations around pregnancy and parenting, 5 the unacceptability of adolescent sexuality and premarital sex 12,13 and women’s responsibility for contraception. 14 In places where norms condemn ...

Abstract. This article presents a research study on abortion from a theoretical and empirical point of view. The theoretical part is based on the method of social documents analysis, and presents a complex perspective on abortion, highlighting items of medical, ethical, moral, religious, social, economic and legal elements.

Abstract. Consensus is lacking on the most appropriate indicators to document progress in safe abortion at programmatic and country level. We conducted a scoping review to provide an extensive summary of abortion indicators used over 10 years (2008–2018) to inform the debate on how progress in the provision and access to abortion care can be ...

Social and moral considerations on abortion. Relatively few Americans view the morality of abortion in stark terms: Overall, just 7% of all U.S. adults say abortion is morally acceptable in all cases, and 13% say it is morally wrong in all cases. A third say that abortion is morally wrong in most cases, while about a quarter (24%) say it is ...

A frequently quoted statistic from a recent study by the Guttmacher Institute, which reports that one in four women will have an abortion before the age of forty-five, may strike you as high, but ...