Find anything you save across the site in your account

Autobiographical Notes

By Jorge Luis Borges

I cannot tell whether my first memories go back to the eastern or to the western bank of the muddy, slow-moving Rio de la Plata—to Montevideo, where we spent long, lazy holidays in the villa of my uncle Francisco Haedo, or to Buenos Aires. I was born there, in the very heart of that city, in 1899, on Tucumán Street, between Suipacha and Esmeralda, in a small, unassuming house belonging to my maternal grandparents. Like most of the houses of that day, it had a flat roof; a long, arched entrance way, called a zaguán ; a cistern, where we got our water; and two patios. We must have moved out to the suburb of Palermo quite soon, because there I have my first memories of another house with two patios, a garden with a tall windmill pump, and, on the other side of the garden, an empty lot. Palermo at that time—the Palermo where we lived, at Serrano and Guatemala streets—was on the shabby northern outskirts of town, and many people, ashamed of saying they lived there, spoke in a dim way of living on the Northside. We lived in one of the few two-story homes on our street; the rest of the neighborhood was made up of low houses and vacant lots. I have often spoken of this area as a slum, but I do not quite mean that in the American sense of the word. In Palermo lived shabby-genteel people as well as more undesirable sorts. There was also a Palermo of hoodlums, called compadritos , famed for their knife fights, but this Palermo was only later to capture my imagination, since we did our best—our successful best—to ignore it. Unlike our neighbor Evaristo Carriego, however, who was the first Argentine poet to explore the literary possibilities that lay there at hand. As for myself, I was hardly aware of the existence of compadritos , since I lived essentially indoors.

My father, Jorge Guillermo Borges, worked as a lawyer. He was a philosophical anarchist—a disciple of Spencer—and also a teacher of psychology at the Normal School for Modern Languages, where he gave his course in English, using as his text William James’s shorter book of psychology. My father’s English came from the fact that his mother, Frances Haslam, was born in Staffordshire of Northumbrian stock. A rather unlikely set of circumstances brought her to South America. Fanny Haslam’s elder sister married an Italian-Jewish engineer named Jorge Suárez, who brought the first horse-drawn tramcars to Argentina, where he and his wife settled and sent for Fanny. I remember an anecdote concerning this venture. Suárez was a guest at General Urquiza’s “palace” in Entre Ríos, and very improvidently won his first game of cards with the General, who was the stern dictator of that province and not above throat-cutting. When the game was over, Suárez was told by alarmed fellow-guests that if he wanted the license to run his tramcars in the province, it was expected of him to lose a certain amount of gold coins each night. Urquiza was such a poor player that Suárez had a great deal of trouble losing the appointed sums.

It was in Paraná, the capital city of Entre Ríos, that Fanny Haslam met Colonel Francisco Borges. This was in 1870 or 1871, during the siege of the city by the montoneros , or gaucho militia, of Ricardo López Jordán. Borges, riding at the head of his regiment, commanded the troops defending the city. Fanny Haslam saw him from the flat roof of her house; that very night a ball was given to celebrate the arrival of the government relief forces. Fanny and the Colonel met, danced, fell in love, and eventually married.

My father was the younger of two sons. He had been born in Entre Ríos and used to explain to my grandmother, a respectable English lady, that he wasn’t really an Entrerriano, since “I was begotten on the pampa.” My grandmother would say, with English reserve, “I’m sure I don’t know what you mean.” My father’s words, of course, were true, since my grandfather was, in the early eighteen-seventies, Commander-in-Chief of the northern and western frontiers of the Province of Buenos Aires. As a child, I heard many stories from Fanny Haslam about frontier life in those days. One of these I set down in my “Story of the Warrior and the Captive.” My grandmother had spoken with a number of Indian chieftains, whose rather uncouth names were, I think, Simón Coliqueo, Catriel, Pincén, and Namuncurá. In 1874, during one of our civil wars, my grandfather, Colonel Borges, met his death. He was forty-one at the time. In the complicated circumstances surrounding his defeat at the battle of La Verde, he rode out slowly on horseback, wearing a white poncho and followed by ten or twelve of his men, toward the enemy lines, where he was struck by two Remington bullets. This was the first time Remington rifles were used in the Argentine, and it tickles my fancy to think that the firm that shaves me every morning bears the same name as the one that killed my grandfather.

Fanny Haslam was a great reader. When she was over eighty, people used to say, in order to be nice to her, that nowadays there were no writers who could be with Dickens and Thackeray. My grandmother would answer, “On the whole, I rather prefer Arnold Bennett, Galsworthy, and Wells.” When she died, at the age of ninety, in 1935, she called us to her side and said, in English (her Spanish was fluent but poor), in her thin voice, “I am only an old woman dying very, very slowly. There is nothing remarkable or interesting about this.” She could see no reason whatever why the whole household should be upset, and she apologized for taking so long to die.

My father was very intelligent and, like all intelligent men, very kind. Once, he told me that I should take a good look at soldiers, uniforms, barracks, flags, churches, priests, and butcher shops, since all these things were about to disappear, and I could tell my children that I had actually seen them. The prophecy has not yet come true, unfortunately. My father was such a modest man that he would have liked being invisible. Though he was very proud of his English ancestry, he used to joke about it, saying with feigned perplexity, “After all, what are the English?! Just a pack of German agricultural laborers.” His idols were Shelley, Keats, and Swinburne. As a reader, he had two interests. First, books on metaphysics and psychology (Berkeley, Hume, Royce, and William James). Second, literature and books about the East (Lane, Burton, and Payne). It was he who revealed the power of poetry to me—the fact that words are not only a means of communication but also magic symbols and music. When I recite poetry in English now, my mother tells me, I take on his very voice. He also, without my being aware of it, gave me my first lessons in philosophy. When I was still quite young, he showed me, with the aid of a chessboard, the paradoxes of Zeno—Achilles and the tortoise, the unmoving flight of the arrow, the impossibility of motion. Later, without mentioning Berkeley’s name, he did his best to teach me the rudiments of idealism.

My mother, Leonor Acevedo de Borges, comes of old Argentine and Uruguayan stock, and at ninety-four is still hale and hearty and a good Catholic. When I was growing up, religion belonged to women and children; most men in Buenos Aires were freethinkers—though, had they been asked, they might have called themselves Catholics. I think I inherited from my mother her quality of thinking the best of people and also her strong sense of friendship. My mother has always had a hospitable mind. From the time she learned English, through my father, she has done most of her reading in that language. After my father’s death, finding that she was unable to keep her mind on the printed page, she tried her hand at translating William Saroyan’s “The Human Comedy” in order to compel herself to concentrate. The translation found its way into print, and she was honored for this by a society of Buenos Aires Armenians. Later on, she translated some of Hawthorne’s stories and one of Herbert Read’s books on art, and she also produced some of the translations of Melville, Virginia Woolf, and Faulkner that are considered mine. She has always been a companion to me—especially in later years, when I went blind—and an understanding and forgiving friend. For years, until recently, she handled all my secretarial work, answering letters, reading to me, taking down my dictation, and also travelling with me on many occasions both at home and abroad. It was she, though I never gave a thought to it at the time, who quickly and effectively fostered my literary career.

Her grandfather was Colonel Isidoro Suárez, who, in 1824, at the age of twenty-four, led a famous charge of Peruvian and Colombian cavalry, which turned the tide of the Battle of Junín, in Peru. This was the next to last battle of the South American War of Independence. Although Suárez was a second cousin to Juan Manuel de Rosas, who ruled as dictator in Argentina from 1835 to 1852, he preferred exile and poverty in Montevideo to living under a tyranny in Buenos Aires. His lands were, of course, confiscated, and one of his brothers was executed. Another member of my mother’s family was Francisco de Laprida, who, in 1816, in Tucumán, where he presided over the Congress, declared the independence of the Argentine Confederation, and was killed in 1829 in a civil war. My mother’s father, Isidoro Acevedo, though a civilian, took part in the fighting of yet other civil wars in the eighteen-sixties and eighties. So, on both sides of my family, I have military forebears; this may account for my yearning after that epic destiny which my gods denied me, no doubt wisely.

I have already said that I spent a great deal of my boyhood indoors. Having no childhood friends, my sister and I invented two imaginary companions, named, for some reason or other, Quilos and The Windmill. (When they finally bored us, we told our mother that they had died.) I was always very nearsighted and wore glasses, and I was rather frail. As most of my people had been soldiers—even my father’s brother had been a naval officer—and I knew I would never be, I felt ashamed, quite early, to be a bookish kind of person and not a man of action. Throughout my boyhood, I thought that to be loved would have amounted to an injustice. I did not feel I deserved any particular love, and I remember my birthdays filled me with shame, because everyone heaped gifts on me and I thought that I had done nothing to deserve them—that I was a kind of fake. After the age of thirty or so, I got over the feeling.

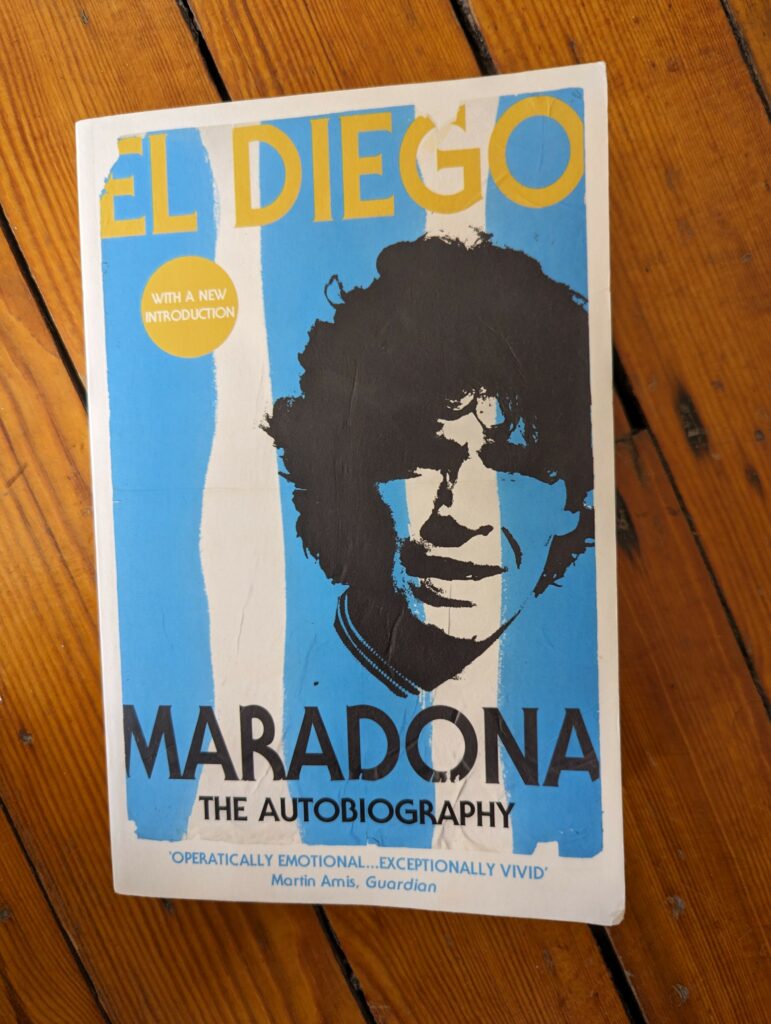

At home, both English and Spanish were commonly used. If I were asked to name the chief event in my Ilife, I should say my father’s library. In fact, I sometimes think I have never strayed outside that library. I can still picture it. It was in a room of its own, with glass-fronted shelves, and must have contained several thousand volumes. Being so nearsighted, I have forgotten most of the faces of that time (perhaps even when I think of my Grandfather Acevedo I am thinking of his photograph), and yet I vividly remember so many of the steel engravings in Chambers’s Encyclopædia and in the Britannica. The first novel I ever read through was “Huckleberry Finn.” Next came “Roughing It” and “Flush Days in California.” I also read books by Captain Marryat, Wells’ “First Men in the Moon,” Poe, a one-volume edition of Longfellow, “Treasure Island,” Dickens, “Don Quixote,” “Tom Brown’s School Days,” Grimms’ “Fairy Tales,” Lewis Carroll, “The Adventures of Mr. Verdant Green” (a now forgotten book), Burton’s “A Thousand Nights and a Night.” The Burton, filled with what was then considered obscenity, was forbidden, and I had to read it in hiding up on the roof. But at the time, I was so carried away with the magic that I took no notice whatever of the objectionable parts, reading the tales unaware of any other significance. All the foregoing books I read in English. When later I read “Don Quixote” in the original, it sounded like a bad translation to me. I still remember those red volumes with the gold lettering of the Garnier edition. At some point, my father’s library was broken up, and when I read the “Quijote” in another edition I had the feeling that it wasn’t the real “Quijote.” Later, I had a friend get me the Garnier, with the same steel engravings, the same footnotes, and also the same errata. All those things form part of the book for me; this I consider the real “Quijote.”

In Spanish, I also read many of the books by Eduardo Gutiérrez about Argentine outlaws and desperadoes—“Juan Moreira” foremost among them—as well as his “Siluetas militares,” which contains a forceful account of Colonel Borges’ death. My mother forbade the reading of “Martin Fierro,” since that was a book fit only for hoodlums and schoolboys and, besides, was not about real gauchos at all. This, too, I read on the sly. Her feelings were based on the fact that Hernandez had been an upholder of Rosas and therefore an enemy to our Unitarian ancestors. I read also Sarmiento’s “Facundo,” many books on Greek mythology, and later Norse. Poetry came to me through English—Shelley, Keats, FitzGerald, and Swinburne, those great favorites of my father, who could quote them voluminously, and often did.

A tradition of literature ran through my father’s family. His great-uncle Juan Crisóstomo Lafinur was one of the first Argentine poets, and he wrote an ode on the death of his friend General Manuel Belgrano, in 1820. One of my father’s cousins, Alvaro Melián Lafinur, whom I knew from childhood, was a leading minor poet and later found his way into the Argentine Academy of Letters. My father’s maternal grandfather, Edward Young Haslam, edited one of the first English papers in Argentina, the Southern Cross , and was a Doctor of Philosophy or Letters, I’m not sure which, of the University of Heidelberg. Haslam could not afford Oxford or Cambridge, so he made his way to Germany, where he got his degree, going through the whole course in Latin. Eventually, he died in Parank. My father wrote a novel, which he published in Majorca in 1921, about the history of Entre Ríos. It was called “The Caudillo.” He also wrote (and destroyed) a book of essays, and published a translation of FitzGerald’s “Omar Khayyam” in the same metre as the original. He destroyed a book of Oriental stories—in the manner of the Arabian Nights—and a drama, “Hacia la nada” (“Toward Nothingness”), about a man’s disappointment in his son. He published some fine sonnets after the style of the Argentine poet Enrique Banchs. From the time I was a boy, when blindness came to him, it was tacitly understood that I had to fulfill the literary destiny that circumstances had denied my father. This was something that was taken for granted (and such things are far more important than things that are merely said). I was expected to be a writer.

I first started writing when I was six or seven. I tried to imitate classic writers of Spanish—Miguel de Cervantes, for example. I had set down in quite bad English a kind of handbook on Greek mythology, no doubt cribbed from Lemprière. This may have been my first literary venture. My first story was a rather nonsensical piece after the manner of Cervantes, an old-fashioned romance called “La visera fatal” (“The Fatal Helmet”). I very neatly wrote these things into copybooks. My father never interfered. He wanted me to commit all my own mistakes, and once said, “Children educate their parents, not the other way around.” When I was nine or so, I translated Oscar Wilde’s “The Happy Prince” into Spanish, and it was published in one of the Buenos Aires dailies, El País . Since it was signed merely “Jorge Borges,” people naturally assumed that the translation was my father’s.

I take no pleasure whatever in recalling my early school days. To begin with, I did not start school until I was nine. This was because my father, as an anarchist, distrusted all enterprises run by the state. As I wore spectacles and dressed in an Eton collar and tie, I was jeered at and bullied by most of my schoolmates, who were amateur hooligans. I cannot remember the name of the school but recall that it was on Thames Street. My father used to say that Argentine history had taken the place of the catechism, so we were expected to worship all things Argentine. We were taught Argentine history, for example, before we were allowed any knowledge of the many lands and many centuries that went into its making. As far as Spanish composition goes, I was taught to write in a flowery way: “ Aquellos que lucharon por una patria libre, independiente, gloriosa . . .” (“Those who struggled for a free, independent, and glorious nation . . .”). Later on, in Geneva, I was to be told that such writing was meaningless and that I must see things through my own eyes. My sister Norah, who was born in 1901, of course attended a girls’ school.

During all these years, we usually spent our summers out in Adrogué, some ten or fifteen miles to the south of Buenos Aires, where we had a place of our own—a large one-story house with grounds, two summerhouses, a windmill, and a shaggy brown sheepdog. Adrogué then was a lost and undisturbed maze of summer homes surrounded by iron fences with masonry planters on the gateposts, of parks, of streets that radiated out of the many plazas, and of the ubiquitous smell of eucalyptus trees. We continued to visit Adrogué for decades.

My first real experience of the pampa came around 1909, on a trip we took to a place belonging to relatives near San Nicolás, to the northwest of Buenos Aires. I remember that the nearest house was a kind of blur on the horizon. This endless distance, I found out, was called the pampa, and when I learned that the farmhands were gauchos, like the characters in Eduardo Gutiérrez, that gave them a certain glamour. I have always come to things after coming to books. Once, I was allowed to accompany them on horseback, taking cattle to the river early one morning. The men were small and darkish and wore bombachas , a kind of wide, baggy trousers. When I asked them if they knew how to swim, they replied, “Water is meant for cattle.” My mother gave a doll, in a large cardboard box, to the foreman’s daughter. The next year, we went back and asked after the little girl. “What a delight the doll has been to her!” they told us. And we were shown it, still in its box, nailed to the wall like an image. Of course, the girl was allowed only to look at it, not to touch it, for it might have been soiled or broken. There it was, high up out of harm’s way, worshiped from afar. Lugones has written that in Córdoba, before magazines came in, he had many times seen a playing card used as a picture and nailed to the wall in gauchos’ shacks. The four of copas , with its small lion and two towers, was particularly coveted. I think I began writing a poem about gauchos, probably under the influence of the poet Ascasubi, before I went to Geneva. I recall trying to work in as many gaucho words as I could, but the technical difficulties were beyond me. I never got past a few stanzas.

In 1914, we moved to Europe. My father’s eyesight had begun to fail and I remember his saying, “How on earth can I sign my name to legal papers when I am unable to read them?” Forced into early retirement, he planned our trip in exactly ten days. The world was unsuspicious then; there were no passports or other red tape. We first spent some weeks in Paris, a city that neither then nor since has particularly charmed me, as it does every other good Argentine. Perhaps, without knowing it, I was always a bit of a Britisher; in fact, I always think of Waterloo as a victory. The idea of the trip was for my sister and me to go to school in Geneva; we were to live with my maternal grandmother, who travelled with us and eventually died there, while my parents toured the Continent. At the same time, my father was to be treated by a famous Genevan eye doctor. Europe in those days was cheaper than Buenos Aires, and Argentine money then stood for something. We were so ignorant of history, however, that we had no idea that the First World War would break out in August. My mother and father were in Germany when it happened, but managed to get back to us in Geneva. A year or so later, despite the war, we were able to journey across the Alps into northern Italy. I have vivid memories of Verona and Venice. In the vast and empty amphitheater of Verona I recited, loud and bold, several gaucho verses from Ascasubi.

That first fall—1914—I started school at the College of Geneva, founded by John Calvin. It was a day school. In my class there were some forty of us; a good half were foreigners. The chief subject was Latin, and I soon found out that one could let other studies slide a bit as long as one’s Latin was good. All these other courses, however—algebra, chemistry, physics, mineralogy, botany, zoology—were studied in French. That year, I passed all my exams successfully, except for French itself. Without a word to me, my fellow-schoolmates sent a petition around to the headmaster, which they had all signed. They pointed out that I had had to study all of the different subjects in French, a language I also had to learn. They asked the headmaster to take this into account, and he very kindly did so. At first, I had not even understood when a teacher was calling on me, because my name was pronounced in the French manner, in a single syllable (rhyming roughly with “forge”), while we pronounce it with two syllables, the “g” sounding like a strong Scottish “h.” Every time I had to answer, my schoolmates would nudge me.

We lived in a flat on the southern, or old, side of town. I still know Geneva far better than I know Buenos Aires, which is easily explained by the fact that in Geneva no two street corners are alike, and one quickly learns the differences. Every day, I walked along that green and icy river, the Rhone, which runs through the very heart of the city, spanned by seven quite different-looking bridges. The Swiss are rather proud and standoffish. My two bosom friends were of Polish-Jewish origin—Simon Jichlinski and Maurice Abramowicz. One became a lawyer and the other a physician. I taught them to play truco , and they learned so well and fast that at the end of our first game they left me without a cent. I became a good Latin scholar, while I did most of my private reading in English. At home, we spoke Spanish, but my sister’s French soon became so good that she even dreamed in it. I remember my mother’s coming home one day and finding Norah hidden behind a red plush curtain, crying out in fear, “ Une mouche, une mouche! ” It seems she had adopted the French notion that flies are dangerous. “You come out of there,” my mother told her, somewhat unpatriotically. “You were born and bred among flies!” As a result of the war—apart from the Italian trip and journeys inside Switzerland—we did no travelling. Later on, braving German submarines and in the company of only four or five other passengers, my English grandmother joined us.

On my own, outside of school, I took up the study of German. I was sent on this adventure by Carlyle’s “Sartor Resartus” (“The Tailor Retailored”), which dazzled and also bewildered me. The hero, Diogenes Devil’sdung, is a German professor of idealism. In German literature I was looking for something Germanic, akin to Tacitus, but I was only later to find this in Old English and in Old Norse. German literature turned out to be romantic and sickly. At first I tried Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason,” but was defeated by it, as most people—including most Germans—are. Then I thought verse would be easier, because of its brevity. So I got hold of a copy of Heine’s early poems, the “Lyrisches Intermezzo,” and a German-English dictionary. Little by little, owing to Heine’s simple vocabulary, I found I could do without the dictionary. Soon I had worked my way into the loveliness of the language. I also managed to read Meyrink’s novel “Der Golem.” (In 1969, when I was in Israel, I talked over the Bohemian legend of the Golem with Gershom Scholem, a leading scholar of Jewish mysticism, whose name I had twice used as the only possible rhyming word in a poem of my own on the Golem.) I tried to be interested in Jean Paul Richter, for Carlyle’s and De Quincey’s sake—this was around 1917—but I soon discovered that I was very bored by him. Richter, in spite of his two British champions, seemed to me very long-winded and perhaps a passionless writer. I became, however, very interested in German Expressionism and still think of it as beyond other contemporary schools, such as Imagism, Cubism, Futurism, Surrealism, and so on. A few years later, in Madrid, I was to attempt some of the first, and perhaps the only, translations of a number of Expressionist poets into Spanish.

At some point while in Switzerland, I began reading Schopenhauer. Today, were I to choose a single philosopher, I would choose him. If the riddle of the universe can be stated in words, I think these words would be in his writings. I have read him many times over, both in German and, with my father and his close friend Macedonio Fernández, in translation. I still think of German as being a beautiful language—perhaps more beautiful than the literature it has produced. French, rather paradoxically, has a fine literature despite its fondness for schools and movements, but the language itself is, I think, rather ugly. Things tend to sound trivial when they are said in French. In fact, I even think of Spanish as being the better of the two languages, though Spanish words are far too long and cumbersome. As an Argentine writer, I have to cope with Spanish and so am only too aware of its shortcomings. I remember that Goethe wrote that he had to deal with the worst language in the world—German. I suppose most writers think along these lines concerning the language they have to struggle with. As for Italian, I have read and reread “The Divine Comedy” in more than a dozen different editions. I’ve also read Ariosto, Tasso, Croce, and Gentile, but I am quite unable to speak Italian or to follow an Italian play or film.

It was also in Geneva that I first met Walt Whitman, through a German translation by Johannes Schlaf (“ Als ich in Alabama meinen Morgengang machte ”—“As I have walk’d in Alabama my morning walk”). Of course, I was struck by the absurdity of reading an American poet in German, so I ordered a copy of “Leaves of Grass” from London. I remember it still—bound in green. For a time, I thought of Whitman not only as a great poet but as the only poet. In fact, I thought that all poets the world over had been merely leading up to Whitman until 1855, and that not to imitate him was a proof of ignorance. This feeling had already come over me with Carlyle’s prose, which is now unbearable to me, and with the poetry of Swinburne. These were phases I went through. Later on, I was to go through similar experiences of being overwhelmed by some particular writer.

We remained in Switzerland until 1919. After three or four years in Geneva, we spent a year in Lugano. I had my bachelor’s degree by then, and it was now understood that I should devote myself to writing. I wanted to show my manuscripts to my father, but he told me that he didn’t believe in advice and that I must work my way all by myself through trial and error. I had been writing sonnets in English and in French. The English sonnets were poor imitations of Wordsworth, and the French, in their own watery way, were imitative of symbolist poetry. I still recall one line of my French experiments: “ Petite boîte noire pour le violon cassé .” The whole piece was titled “Poéme pour être récité avec un accent russe.” As I knew I wrote a foreigner’s French, I thought a Russian accent better than an Argentine one. In my English experiments, I affected some eighteenth-century mannerisms, such as “o’er” instead of “over” and, for the sake of metrical ease, “doth sing” instead of “sings.” I knew, however, that Spanish would be my unavoidable destiny.

We decided to go home, but to spend a year or so in Spain first. Spain at that time was slowly being discovered by Argentines. Until then, even eminent writers like Leopoldo Lugones and Ricardo Güraldes deliberately left Spain out of their European travels. This was no whim. In Buenos Aires, Spaniards always held menial jobs—as domestic servants, waiters, and laborers—or were small tradesmen, and we Argentines never thought of ourselves as Spanish. We had, in fact, left off being Spaniards in 1816, when we declared our independence from Spain. When, as a boy, I read Prescott’s “Conquest of Peru,” it amazed me to find that he portrayed the conquistadores in a romantic way. To me, descended from certain of these officials, they were an uninteresting lot. Through French eyes, however, Latin Americans saw the Spaniards as picturesque, thinking of them in terms of the stock in trade of García Lorca—gypsies, bullfights, and Moorish architecture. But though Spanish was our language and we came mostly of Spanish and Portuguese blood, my own family never thought of our trip in terms of going back to Spain after an absence of some three centuries.

We went to Majorca because it was cheap, beautiful, and had hardly any tourists but ourselves. We lived there nearly a whole year, in Palma and in Valldemosa, a village high up in the hills. I went on studying Latin, this time under the tutelage of a priest, who told me that since the innate was sufficient to his needs, he had never attempted reading a novel. We went over Vergil, of whom I still think highly. I remember I astonished the natives by my fine swimming, for I had learned in swift rivers, such as the Uruguay and the Rhone, while Majorcans were used only to a quiet, tideless sea. My father was writing his novel, which harked back to old times during the civil war of the eighteen-seventies in his native Entre Ríos. I recall giving him some quite bad metaphors, borrowed from the German Expressionists, which he accepted out of resignation. He had some five hundred copies of the book printed, and brought them back to Buenos Aires, where he gave them away to friends. Every time the word “Paraná”—his home town—came up in the manuscript, the printers had changed it to “Panama,” thinking they were correcting a mistake. Not to give them trouble, and also seeing that it was funnier that way, my father let this pass. Now I repent my youthful intrusions into his book. Seventeen years later, before he died, he told me that he would very much like me to rewrite the novel in a straightforward way, with all the fine writing and purple patches left out. I myself in those days wrote a story about a werewolf and sent it to a popular magazine in Madrid, La Esfera , whose editors very wisely turned it down.

The winter of 1919-20 we spent in Seville, where I saw my first poem into print. It was titled “Hymn to the Sea” and appeared in the magazine Grecia , in its issue of December 31, 1919. In the poem, I tried my hardest to be Walt Whitman:

O seal O myth! O sun! O wide resting place! I know why I love you. I know that we are both very old, that we have known each other for centuries. . . . O Protean, I have been born of you— both of us chained and wandering, both of us hungering for stars, both of us with hopes and disappointments . . . !

Today, I hardly think of the sea, or even of myself, as hungering for stars. Years after, when I came across Arnold Bennett’s phrase “the third-rate grandiose,” I understood at once what he meant. And yet when I arrived in Madrid a few months later, as this was the only poem I had ever printed, people there thought of me as a singer of the sea.

In Seville, I fell in with the literary group formed around Grecia . This group, who called themselves Ultraists, had set out to renew literature, a branch of the arts of which they knew nothing whatever. One of them once told me his whole reading had been the Bible, Cervantes, Dario, and one or two of the books of the Master, Rafael Cansinos-Asséns. It baffled my Argentine mind to learn that they had no French and no inkling at all that such a thing as English literature existed. I was even introduced to a local worthy popularly known as “the Humanist” and was not long in discovering that his Latin was far smaller than mine. As for Grecia itself, the editor, Isaac del Vando Villar, had the whole corpus of his poetry written for him by one or another of his assistants. I remember one of them telling me one day, “I’m very busy—Isaac is writing a poem.”

Next, we went to Madrid, and there the great event to me was my friendship with Rafael Cansinos-Asséns. I still like to think of myself as his disciple. He had come from Seville, where he studied for the priesthood, but, having found the name Cansinos in the archives of the Inquisition, he decided he was a Jew. This led him to the study of Hebrew, and later on he even had himself circumcised. Literary friends from Andalusia took me to meet him. I timidly congratulated him on a poem he had written about the sea. “Yes,” he said, “and how I’d like to see it before I die.” He was a tall man, with the Andalusian contempt for all things Castilian. The most remarkable fact about Cansinos was that he lived completely for literature, without regard for money or fame. He was a fine poet and wrote a book of psalms—chiefly erotic—called “El candelabro de los siete brazos,” which was published in 1915. He also wrote novels, stories, and essays, and, when I knew him, presided over a literary circle.

Every Saturday I would go to the Café Colonial, where we met at midnight, and the conversation lasted until daybreak. Sometimes there were as many as twenty or thirty of us. The group despised all Spanish local color— cante jondo and bullfights. They admired American jazz, and were more interested in being Europeans than Spaniards. Cansinos would propose a subject—the Metaphor, Free Verse, the Traditional Forms of Poetry, Narrative Poetry, the Adjective, the Verb. In his own quiet way, he was a dictator, allowing no unfriendly allusions to contemporary writers and trying to keep the talk on a high plane.

Cansinos was a wide reader. He had translated De Quincey’s “Opium-Eater,” the “Meditations of Marcus Aurelius” from the Greek, novels of Barbusse, and Schwob’s “Vies imaginaires.” Later, he was to undertake complete translations of Goethe and Dostoevski. He also made the first Spanish version of the Arabian Nights, which is very free compared to Burton’s or Lane’s, but which makes, I think, for more pleasurable reading. Once, I went to see him and he took me into his library. Or, rather, I should say his whole house was a library. It was like making your way through woods. He was too poor to have shelves, and the books were piled one on top of the other from floor to ceiling, forcing you to thread your way among the vertical columns. Cansinos seemed to me as if he were all the past of that Europe I was leaving behind—something like the symbol of all culture, Western and Eastern. But he had a perversity that made him fail to get on with his leading contemporaries. It lay in writing books that lavishly praised second- or third-rate writers. At the time, Ortega y Gasset was at the height of his fame, but Cansinos thought of him as a bad philosopher and a bad writer. What I got from him, chiefly, was the pleasure of literary conversation. Also, I was stimulated by him to far-flung reading. In writing, I began aping him. He wrote long and flowing sentences with an un-Spanish and strongly Hebrew flavor to them.

Oddly, it was Cansinos who, in 1919, invented the term “Ultraism.” He thought Spanish literature had always been behind the times. Under the pen name of Juan Las, he wrote some short, laconic Ultraist pieces. The whole thing—I see now—was done in a spirit of mockery. But we youngsters took it very seriously. Another of the earnest followers was Guillermo de Torre, whom I met in Madrid that spring and who married my sister Norah nine years later.

In Madrid at this time, there was another group gathered around Gómez de la Serna. I went there once and didn’t like the way they behaved. They had a buffoon who wore a bracelet with a rattle attached. He would be made to shake hands with people and the rattle would rattle and Gómez de la Serna would invariably say, “Where’s the snake?” That was supposed to be funny. Once, he turned to me proudly and remarked, “You’ve never seen this kind of thing in Buenos Aires, have you?” I owned, thank God, that I hadn’t.

In Spain, I wrote two books. One was a series of essays called, I now wonder why, “Los naipes del tahur” (“The Sharper’s Cards”). They were literary and political essays (I was still an anarchist and a freethinker and in favor of pacifism), written under the influence of Pío Baroja. Their aim was to be bitter and relentless, but they were, as a matter of fact, quite tame. I went in for using such words as “fools,” “harlots,” “lars.” Failing to find a publisher, I destroyed the manuscript on my return to Buenos Aires. The second book was titled either “The Red Psalms” or “The Red Rhythms.” It was a collection of poems—perhaps some twenty in all—in free verse and in praise of the Russian Revolution, the brotherhood of man, and pacifism. Three or four of them found their way into magazines—“Bolshevik Epic,” “Trenches,” “Russia.” This book I destroyed in Spain on the eve of our departure. I was then ready to go home.

We returned to Buenos Aires on the Reina Victoria Eugenia toward the end of March, 1921. It came to me as a surprise, after living in so many European cities—after so many memories of Geneva, Zurich, Nimes, Córdoba, and Lisbon—to find that my native town had grown, and that it was now a very large, sprawling, and almost endless city of low buildings with flat roofs, stretching west toward the pampa. It was more than a homecoming; it was a rediscovery. I was able to see Buenos Aires keenly and eagerly because I had been away from it for a long time. Had I never gone abroad, I wonder whether I would ever have seen it with the peculiar shock and glow that it now gave me. The city—not the whole city, of course, but a few places in it that became emotionally significant to me—inspired the poems of my first published book, “Fervor de Buenos Aires.”

I wrote these poems in 1921 and 1922, and the volume came out early in 1923. The book was actually printed in five days; the printing had to be rushed, because it was necessary for us to return to Europe. (My father wanted to consult his Genevan doctor about his sight.) I had bargained for sixty-four pages, but the manuscript ran too long and at the last minute five poems had to be left out—mercifully. I can’t remember a single thing about them. The book was produced in a somewhat boyish spirit. No proofreading was done, no table of contents was provided, and the pages were unnumbered. My sister made a woodcut for the cover, and three hundred copies were printed. In those days, publishing a book was something of a private venture. I never thought of sending copies to the booksellers or out for review. Most of them I just gave away. I recall one of my methods of distribution. Having noticed that many people who went to the offices of Nosotros —one of the older, more solid literary magazines of the time—left their overcoats hanging in the cloak room, I brought fifty or a hundred copies to Alfredo Bianchi, one of the editors. Bianchi stared at me in amazement and said, “Do you expect me to sell these books for you?” “No,” I answered. “Although I’ve written them, I’m not altogether a lunatic. I thought I might ask you to slip some of these books into the pockets of those coats hanging out there.” He generously did so. When I came back after a year’s absence, I found that some of the inhabitants of the overcoats had read my poems, and a few had even written about them. As a matter of fact, in this way I got myself a small reputation as a poet.

The book was essentially romantic, though it was written in a rather lean style and abounded in laconic metaphors. It celebrated sunsets, solitary places, and unfamiliar corners; it ventured into Berkeleian metaphysics and family history; it recorded early loves. At the same time, I also mimicked the Spanish seventeenth century and cited Sir Thomas Browne’s “Urne-Buriall” in my preface. I’m afraid the book was a plum pudding—there was just too much in it. And yet, looking back on it now, I think I have never strayed beyond that book. I feel that all my subsequent writing has only developed themes first taken up there; I feel that all during my lifetime I have been rewriting that one book.

Were the poems in “Fervor de Buenos Aires” Ultraist poetry? When I came back from Europe in 1921, I came bearing the banners of Ultraism. I am still known to literary historians as “the father of Argentine Ultraism.” When I talked things over at the time with fellow-poets Eduardo González Lanuza, Norah Lange, Francisco Piñero, my cousin Guillermo Juan (Borges), and Roberto Ortelli, we came to the conclusion that Spanish Ultraism was overburdened—after the manner of Futurism—with modernity and gadgets. We were unimpressed by railway trains, by propellers, by airplanes, and by electric fans. While in our manifestos we still upheld the primacy of the metaphor and the elimination of transitions and decorative adjectives, what we wanted to write was essential poetry—poems beyond the here and now, free of local color and contemporary circumstances. I think the poem “Plainness” sufficiently illustrates what I personally was after:

The garden’s grillwork gate opens with the ease of a page in a much thumbed book, and, once inside, our eyes have no need to dwell on objects already fixed and exact in memory. Here habits and minds and the private language all families invent are everyday things to me. What necessity is there to speak or pretend to be someone else? The whole house knows me, they’re aware of my worries and weakness. This is the best that can happen— what Heaven perhaps will grant us: not to be wondered at or required to succeed but simply to be let in as part of an undeniable Reality, like stones of the road, like trees.

I think this is a far cry from the timid extravagances of my earlier Spanish Ultraist exercises, when I saw a trolley car as a man shouldering a gun, or the sunrise as a shout, or the setting sun as being crucified in the west. A sane friend to whom I later recited such absurdities remarked, “Ah, I see you held the view that poetry’s chief aim is to startle.” As to whether the poems in “Fervor” are Ultraist or not, the answer—for me—was given by my friend and French translator Néstor Ibarra, who said, “Borges left off being an Ultraist poet with the first Ultraist poem he wrote.” I can now only regret my early Ultraist excesses. After nearly a half century, I find myself still striving to live down that awkward period of my life.

Perhaps the major event of my return was Macedonio Fernández. Of all the people I have met in my life—and I have met some quite remarkable men—no one has ever made so deep and so lasting an impression on me as Macedonio. A tiny figure in a black bowler hat, he was waiting for us on the Dársena Norte when we landed, and I came to inherit his friendship from my father. Both men had been born in 1874. Paradoxically, Macedonio was an outstanding conversationalist and at the same time a man of long silences and few words. We met on Saturday evenings at a café—the Perla, in the Plaza del Once. There we would talk till daybreak, Macedonio presiding. As in Madrid Cansinos had stood for all learning, Macedonio now stood for pure thinking. At the time, I was a great reader and went out very seldom (almost every night after dinner, I used to go to bed and read), but my whole week was lit up with the expectation that on Saturday I’d be seeing and hearing Macedonio. He lived quite near us and I could have seen him whenever I wanted, but I somehow felt that I had no right to that privilege and that in order to give Macedonio’s Saturday its full value I had to forgo him throughout the week. At these meetings, Macedonio would speak perhaps three or four times, risking only a few quiet observations, which were addressed—seemingly—to his neighbor alone. These remarks were never affirmative. Macedonio was very courteous and soft-spoken and would say, for example, “Well, I suppose you’ve noticed . . .” And thereupon he would let loose some striking, highly original thought. But, invariably, he attributed his remark to the hearer.

He was a frail, gray man with a kind of ash-colored hair and mustache that made him look like Mark Twain. The resemblance pleased him, but when he was reminded that he also looked like Paul Valéry, he resented it, since he had little use for Frenchmen. He always wore that black bowler, and for all I know may even have slept in it. He never undressed to go to bed, and at night, to fend off drafts that he thought might cause him toothache, he draped a towel around his head. This made him look like an Arab. Among his other eccentricities were his nationalism (he admired one Argentine president after another for the sufficient reason that the Argentine electorate could not be wrong), his fear of dentistry (this led him to tugging at his teeth, in public, behind a hand, so as to stave off the dentist’s pliers), and a habit of falling sentimentally in love with streetwalkers.

As a writer, Macedonio published several rather unusual volumes, and papers of his are still being collected close to twenty years after his death. His first book, published in 1928, was called “No toda es vigilia la de los ojos abiertos” (“We’re Not Always Awake When Our Eyes Are Open”). It was an extended essay on idealism, written in a deliberately tangled and crabbed style, in order, I suppose, to match the tangledness of reality. The next year, a miscellany of his writings appeared—“Papeles de recienvenido” (“Newcomer’s Papers”)—in which I myself took a hand, collecting and ordering the chapters. This was a sort of miscellany of jokes within jokes. Macedonio also wrote novels and poems, all of them startling but hardly readable. One novel of twenty chapters is prefaced by fifty-six different forewords. For all his brilliance, I don’t think Macedonio is to be found in his writings at all. The real Macedonio was in his conversation.

Macedonio lived modestly in boarding houses, which he seemed to change with frequency. This was because he was always skipping out on the rent. Every time he would move, he’d leave behind piles and piles of manuscripts. Once, his friends scolded him about this, telling him it was a shame all that work should be lost. He said to us, “Do you really think I’m rich enough to lose anything?”

Readers of Hume and Schopenhauer may find little that is new in Macedonio, but the remarkable thing about him is that he arrived at his conclusions by himself. Later on, he actually read Hume, Schopenhauer, Berkeley, and William James, but I suspect he had not done much other reading, and he always quoted the same authors. He considered Sir Walter Scott the greatest of novelists, maybe just out of loyalty to a boyhood enthusiasm. He had once exchanged letters with William James, whom he had written in a medley of English, German, and French, explaining that it was because “I knew so little in any one of these languages that I had constantly to shift tongues.” I think of Macedonio as reading a page or so and then being spurred into thought. He not only argued that we are such stuff as dreams are made on but he really believed that we are all living in a dream world. Macedonio doubted whether truth was communicable. He thought that certain philosophers had discovered it but that they had failed to communicate it completely. However, he also believed that the discovery of truth was quite easy. He once told me that if he could lie out on the pampa, forgetting the world, himself, and his quest, truth might suddenly reveal itself to him. He added that, of course, it might be impossible to put that sudden wisdom into words.

Macedonio was fond of compiling small oral catalogues of people of genius, and in one of them I was amazed to find the name of a very lovable lady of our acquaintance, Quica González Acha de Tomkinsan Alvear. I stared at him openmouthed. I somehow did not think Quica ranked with Hume and Schopenhauer. But Macedonio said, “Philosophers have had to try and explain the universe, while Quica simply feels and understands it.” He would turn to her and ask, “Quica, what is Being?” Quica would answer, “I don’t know what you mean, Macedonio.” “You see,” he would say to me, “she understands so perfectly that she cannot even grasp the fact that we are puzzled.” This was his proof of Quica’s being a woman of genius. When I later told him he might say the same of a child or a cat, Macedonio took it angrily.

Before Macedonio, I had always been a credulous reader. His chief gift to me was to make me read skeptically. At the outset, I plagiarized him devotedly, picking up certain stylistic mannerisms of his that I later came to regret. I look back on him now, however, as an Adam bewildered by the Garden of Eden. His genius survives in but a few of his pages; his influence was of a Socratic nature. I truly loved the man, on this side idolatry, as much as any.

This period, from 1921 to 1930, I was one of great activity, but much of it was perhaps reckless and even pointless. I wrote and published no less than seven books—four of them essays and three of them verse. I also founded three magazines and contributed with fair frequency to nearly a dozen other periodicals, among them La Prensa , Nosotros , Inicial , Criterio , and Sintesis . This productivity now amazes me as much as the fact that I feel only the remotest kinship with the work of these years. Three of the four essay collections—whose names are best forgotten—I have never allowed to be reprinted. In fact, when, in 1953, my present publisher, Emecé, proposed to bring out my “complete writings,” the only reason I accepted was that it would allow me to keep those preposterous volumes suppressed. This reminds me of Mark Twain’s suggestion that a fine library could be started by leaving out the works of Jane Austen, and that even if that library contained no other books it would still be a fine library, since her books were left out.

In the first of these reckless compilations, there was a quite bad essay on Sir Thomas Browne, which may have been the first ever attempted on him in the Spanish language. There was another essay that set out to classify metaphors as though other poetic elements, such as rhythm and music, could be safely ignored. There was a longish essay on the nonexistence of the ego, cribbed from Bradley or the Buddha or Macedonio Fernández. When I wrote these pieces, I was trying to play the sedulous ape to two Spanish-baroque seventeenth-century writers, Quevedo and Saavedra Fajardo, who stood in their own stiff, arid, Spanish way for the same kind of writing as Sir Thomas Browne in “Urne-Buriall.” I was doing my best to write Latin in Spanish, and the book collapses under the sheer weight of its involutions and sententious judgments. The next of these failures was a kind of reaction. I went to the other extreme—I tried to be as Argentine as I could. I got hold of Segovia’s dictionary of Argentinisms and worked in so many local words that many of my countrymen could hardly understand it. Since I have mislaid the dictionary, I’m not sure I would any longer understand the book myself, and so have given it up as utterly hopeless. The third of these unmentionables stands for a kind of partial redemption. I was creeping out of the second book’s style and slowly going back to sanity, to writing with some attempt at logic and at making things easy for the reader rather than dazzling him with purple passages. One such experiment, of dubious value, was “Hombres pelearon” (“Men Fought”), my first venture into the mythology of the old Northside of Buenos Aires. In it, I was trying to tell a purely Argentine story in an Argentine way. This story is one I have been retelling, with small variations, ever since. It is the tale of the motiveless, or disinterested, duel—of courage for its own sake. I insisted when I wrote it that in our sense of the language we Argentines were different from the Spaniards. Now, instead, I think we should try to stress our linguistic affinities. I was still writing, but in a milder way, so that Spaniards would not understand me—writing, it might be said, to be ununderstood. The Gnostics claimed that the only way to avoid a sin was to commit it and be rid of it. In my books of these years, I seem to have committed most of the major literary sins, some of them under the influence of a great writer, Leopoldo Lugones, whom I still cannot help admiring. These sins were fine writing, local color, a quest for the unexpected, and a seventeenth-century style. Today, I no longer feel guilty over these excesses; those books were written by somebody else. Until a few years ago, if the price were not too stiff, I would buy up copies and burn them.

Of the poems of this time, I should perhaps have also suppressed my second collection, “Luna de enfrente” (“Moon Across the Way”). It was published in 1925 and is a kind of riot of sham local color. Among its tomfooleries were the spelling of my first name in the nineteenth-century Chilean fashion as “Jorje” (it was a halfhearted attempt at phonetic spelling); the spelling of the Spanish for “and” as “ i ” instead of “ y ” (our greatest writer, Sarmiento, had done the same, trying to be as un-Spanish as he could); and the omission of the final “d” in words like “ autoridá ” and “ ciudá .” In later editions, I dropped the worst poems, pruned the eccentricities, and, successively—through several reprintings—revised and toned down the verses. The third collection of the time, “Cuaderno San Martín” (the title has nothing to do with the national hero; it was merely the brand name of the out-of-fashion copybook into which I wrote the poems), includes some quite legitimate pieces, such as “La noche que en el Sur lo velaron,” whose title has been strikingly translated by Robert Fitzgerald as “Deathwatch on the Southside,” and “Muertes de Buenos Aires” (“Deaths of Buenos Aires”), about the two chief graveyards of the Argentine capital. One poem in the book (no favorite of mine) has somehow become a minor Argentine classic: “The Mythical Founding of Buenos Aires.” This book, too, has been improved, or purified, by cuts and revisions down through the years.

In 1929, that third book of essays won the Second Municipal Prize of three thousand pesos, which in those days was a lordly sum of money. I was, for one thing, to acquire with it a second-hand set of the Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. For another, I was insured a year’s leisure and decided I would write a longish book on a wholly Argentine subject. My mother wanted me to write about any of three really worthwhile poets—Ascasubi, Almafuerte, or Lugones. I now wish I had. Instead, I chose to write about a popular but minor poet, Evaristo Carriego. My mother and father pointed out that his poems were not good. “But he was a friend and neighbor of ours,” I said. “Well, if you think that qualifies him as the subject for a book, go ahead,” they said. Carriego was the man who discovered the literary possibilities of the run-down and ragged outskirts of the city—the Palermo of my boyhood. His career followed the same evolution as the tango—rollicking, daring, courageous at first, then turning sentimental. In 1912, at the age of twenty-nine, he died of tuberculosis, leaving behind a single volume of his work. I remember that a copy of it, inscribed to my father, was one of several Argentine books that we had taken to Geneva and that I read and reread there. Around 1909, Carriego had dedicated a poem to my mother. Actually, he had written it in her album. In it, he spoke of me: “And may your son . . . go forth, led by the trusting wing of inspiration, to carry out the vintage of a new annunciation, which from lofty grapes will yield the wine of Song.” But when I began writing my book the same thing happened to me that happened to Carlyle as he wrote his “Frederick the Great.” The more I wrote, the less I cared about my hero. I had started out to do a straight biography, but on the way I became more and more interested in old-time Buenos Aires. Readers, of course, were not slow in finding out that the book hardly lived up to its title, “Evaristo Carriego,” and so it fell flat. When the second edition appeared twenty-five years later, in 1955, as the fourth volume of my “complete” works, I enlarged the book with several new chapters, one a “History of the Tango.” As a consequence of these additions, I feel “Evaristo Carriego” has been rounded out for the better.

Prisma , founded in 1921 and lasting two numbers, was the earliest of the magazines I edited. Our small Ultraist group was eager to have a magazine of its own, but a real magazine was beyond our means. I had noticed billboard ads, and the thought came to me that we might similarly print a “mural magazine” and paste it up ourselves on the walls of buildings in different parts of town. Each issue was a large single sheet and contained a manifesto and some six or eight short, laconic poems, printed with plenty of white space around them, and a woodcut by my sister. We sallied forth at night—González Lanuza, Piñero, my cousin, and I—armed with pastepots and brushes provided by my mother, and, walking miles on end, slapped them up along Santa Fe, Calao, Entre Ríos, and Mexico Streets. Most of our handiwork was torn down by baffled readers almost at once, but, luckily for us, Alfredo Bianchi, of Nosotros , saw one of them and invited us to publish an Ultraist anthology among the pages of his solid magazine. After Prisma , we went in for a six-page magazine, which was really just a single sheet printed on both sides and folded twice. This was the first Proa ( Prow ), and three numbers of it were published. Two years later, in 1924, came the second Proa . One afternoon, Brandin Caraffa, a young poet from Córdoba, came to see me at the Garden Hotel, where we were living upon return from our second European trip. He told me that Ricardo Gitiraldes and Pablo Rojas Paz had decided to found a magazine that would represent the new literary generation, and that everyone had said that if that were its goal I could not possibly be left out. Naturally, I was flattered. That night, I went around to the Phoenix Hotel, where Güiraldes was staying. He greeted me with these words: “Brandin told me that the night before last all of you got together to found a magazine of young writers, and everyone said I couldn’t be left out.” At that moment, Rojas Paz came in and told us excitedly, “I’m quite flattered.” I broke in and said, “The night before last, the three of us got together and decided that in a magazine of new writers you couldn’t be left out.” Thanks to this innocent stratagem, Proa was born. Each one of us put in fifty pesos, which paid for an edition of three to five hundred copies with no misprints and on fine paper. But a year and a half and fifteen issues later, for lack of subscriptions and ads, we had to give it up.

These years were quite happy ones because they stood for many friendships. There were those of Norah Lange, Macedonio, Piñero, and my father. Behind our work was a sincerity; we felt we were renewing both prose and poetry. Of course, like all young men, I tried to be as unhappy as I could—a kind of Hamlet and Raskolnikov rolled into one. What we achieved was quite bad, but our comradeships endured.

In 1924, I found my way into two different literary sets. One, whose memory I still enjoy, was that of Güiraldes, who was yet to write “Don Segundo Sombra.” Güiraldes was very generous to me. I would give him a quite clumsy poem and he would read between the lines and divine what I had been trying to say but what my literary incapacity had prevented me from saying. He would then speak of the poem to other people, who were baffled not to find these things in the text. The other set, which I rather regret, was that of the magazine Martín Fierro . I disliked what Martín Fierro stood for, which was the French idea that literature is being continually renewed—that Adam is reborn every morning—and also for the idea that since Paris had literary cliques that wallowed in publicity and bickering, we should be up to date and do the same. One result of this was that a sham literary feud was cooked up in Buenos Aires—that between Florida and Boedo. Florida represented downtown and Boedo the proletariat. I’d have preferred to be in the Boedo group, since I was writing about the old Northside and slums, sadness, and sunsets. But I was informed by one of the two conspirators—they were Ernesto Palacio, of Florida, and Roberto Mariani, of Boedo—that I was already one of the Florida warriors and it was too late for me to change. The whole thing was just a put-up job. Some writers belonged to both groups—Roberto Arlt and Nicolás Olivari, for example. This sham is now taken into serious consideration by “credulous universities.” But it was partly publicity, partly a boyish prank.

Linked to this time are the names of Silvina and Victoria Ocampo, of the poet Carlos Mastronardi, of Eduardo Mallea, and, not least, of Alejandro Xul-Solar. In a rough-and-ready way, it may be said that Xul, who was a mystic, a poet, and a painter, is our William Blake. I remember asking him on one particularly sultry afternoon about what he had done that stifling day. His answer was “Nothing whatever, except for founding twelve religions after lunch.” Xul was also a philologist and the inventor of two languages. One was a philosophical language after the manner of John Wilkins and the other a reformation of Spanish with many English, German, and Greek words thrown in. He came of Baltic and Italian stock. “Xul” was his version of “Schulz” and “Solar” of “Solari.” At this time, I also met Alfonso Reyes. He was the Mexican Ambassador to Argentina, and used to invite me to dinner every Sunday at the Embassy. I think of Reyes as the finest Spanish prose stylist of this century, and in my writing I learned a great deal about simplicity and directness from him.

Summing up this span of my life, I find myself completely out of sympathy with the priggish and rather dogmatic young man I then was. Those friends, however, are still very living and very close to me. In fact, they form a precious part of me. Friendship is, I think, the one redeeming Argentine passion.

In the course of a lifetime devoted chiefly to books, I have read but few novels, and, in most cases, only a sense of duty has enabled me to find my way to their last page. At the same time, I have always been a reader and rereader of short stories. Stevenson, Kipling, James, Conrad, Poe, Chesterton, the tales of Lane’s “Arabian Nights,” and certain stories by Hawthorne have been habits of mine since I can remember. The feeling that great novels like “Don Quixote” and “Huckleberry Finn” are virtually shapeless served to reinforce my taste for the short-story form, whose indispensable elements are economy and a clearly stated beginning, middle, and end. As a writer, however, I thought for years that the short story was beyond my powers, and it was only after a long and roundabout series of timid experiments in narration that I sat down to write real stories.

It took me some six years, from 1927 to 1933, to go from that all too self-conscious sketch “Hombres pelearon” to my first outright short story, “Hombre de la esquina rosada” (“Streetcorner Man”). A friend of mine, don Nicolás Paredes, a former political boss and professional gambler of the Northside, had died, and I wanted to record something of his voice, his anecdotes, and his particular way of telling them. I slaved over my every page, sounding out each sentence and striving to phrase it in his exact tones. We were living out in Adrogué at the time and, because I knew my mother would heartily disapprove of the subject matter, I composed in secret over a period of several months. Originally titled “Hombres de las orillas” (“Men from the Edge of Town”), the story appeared in the Saturday supplement, which I was editing, of a yellow-press daily called Crítica . But out of shyness, and perhaps a feeling that the story was a bit beneath me, I signed it with a pen name—the name of one of my great-great-grandfathers, Francisco Bustos. Although the story became popular to the point of embarrassment (today, I only find it stagy and mannered and the characters bogus), I never regarded it as a starting point. It simply stands there as a kind of freak.

The real beginning of my career as a story writer starts with the series of sketches entitled “Historia universal de la infamia” (“A Universal History of Infamy”), which I contributed to the columns of Crítica in 1933 and 1934. The irony of this is that “Streetcorner Man” really was a story but that these sketches and several of the fictional pieces which followed them, and which very slowly led me to legitimate stories, were in the nature of hoaxes and pseudo-essays. In my “Universal History,” I did not want to repeat what Marcel Schwob had done in his “Imaginary Lives.” He had invented biographies of real men about whom little or nothing is recorded. I, instead, read up on the lives of known persons and then deliberately varied and distorted them according to my own whims. For example, after reading Herbert Asbury’s “The Gangs of New York,” I set down my free version of Monk Eastman, the Jewish gunman, in flagrant contradiction of my chosen authority. I did the same for Billy the Kid, for John Murrel (whom I rechristened Lazarus Morell), for the Veiled Prophet of Khorassan, for the Tichborne Claimant, and for several others. I never thought of book publication. The pieces were meant for popular consumption in Crítica and were pointedly picturesque. I suppose now the secret value of those sketches—apart from the sheer pleasure the writing gave me—lay in the fact that they were narrative exercises. Since the general plots or circumstances were all given me, I had only to embroider sets of vivid variations.

My next story, “The Approach to al-Mu’tasim,” written in 1935, is both a hoax and a pseudo-essay. It purports to be a review of a book published originally in Bombay three years earlier. I endowed its fake second edition with a real publisher, Victor Gollancz, and a preface by a real writer, Dorothy L. Sayers. But the author and the book are entirely my own invention. I gave the plot and details of some chapters—borrowing from Kipling and working in the twelfth-century Persian mystic Farid ud-Din Attar—and then carefully pointed out its shortcomings. The story appeared the next year in a volume of my essays, “Historia de la eternidad” (“A History of Eternity”), buried at the back of the book together with an article on the “Art of Insult.” Those who read “The Approach to al-Mu’tasim” took it at face value, and one of my friends even ordered a copy from London. It was not until 1942 that I openly published it as a short story in my first story collection, “El jardin de senderos que se bifurcan” (“The Garden of Branching Paths”). Perhaps I have been unfair to this story; it now seems to me to foreshadow and even to set the pattern for those tales that were somehow awaiting me, and upon which my reputation as a storyteller was to be based.

Along about 1937, I took my first regular full-time job. I had previously worked at small editing tasks. There was the Crítica supplement, which was a heavily and even gaudily illustrated entertainment sheet. There was El Hogar , a popular society weekly, to which, twice a month, I contributed a couple of literary pages on foreign books and authors. I had also written newsreel texts and had been editor of a pseudo-scientific magazine called Urbe , which was really a promotional organ of a privately owned Buenos Aires subway system. These had all been small-paving jobs, and I was long past the age when I should have begun contributing to our household upkeep. Now, through friends, I was given a very minor position as First Assistant in the Miguel Cané branch of the Municipal Library, out in a drab and dreary part of town to the southwest. While there were Second and Third Assistants below me, there were also a Director and First, Second, and Third Officials above me. I was paid two hundred and ten pesos a month and later went up to two hundred and forty. These were sums roughly equivalent to seventy or eighty American dollars.

At the library, we did very little work. There were some fifty of us doing what fifteen could easily have done. My particular job, shared with fifteen or twenty colleagues, was classifying and cataloguing the library’s holdings, which until that time were uncatalogued. The collection, however, was so small that we knew where to find the books without the system, so the system, though laboriously carried out, was never needed or used. The first day, I worked honestly. On the next, some of my fellows took me aside to say that I couldn’t do this sort of thing because it showed them up. “Besides,” they argued, “as this cataloguing has been planned to give us some semblance of work, you’ll put us out of our jobs.” I told them I had classified four hundred titles instead of their one hundred. “Well, if you keep that up,” they said, “the boss will be angry and won’t know what to do with us.” For the sake of realism, I was told that from then on I should do eighty-three books one day, ninety another, and one hundred and four the third.

I stuck out the library for about nine years. They were nine years of solid unhappiness. At work, the other men were interested in nothing but horse racing, soccer matches, and smutty stories. Once, a woman, one of the readers, was raped on her way to the ladies’ room. Everybody said such things were bound to happen, since the men’s and ladies rooms were adjoining. One day, two rather posh and well-meaning friends—society ladies—came to see me at work. They phoned me a day or two later to say, “You may think it amusing to work in a place like that, but promise us you will find at least a nine-hundred-peso job before the month is out.” I gave them my word that I would. Ironically, at the time I was a fairly well-known writer—except at the library. I remember a fellow-employee’s once noting in an encyclopedia the name of a certain Jorge Luis Borges—a fact that set him wondering at the coincidence of our identical names and birth dates. Now and then during these years, we municipal workers were rewarded with gifts of a two-pound package of maté to take home. Sometimes in the evening, as I walked the ten blocks to the tramline, my eyes would be filled with tears. These small gifts from above always underlined my menial and dismal existence.

A couple of hours each day, riding back and forth on the tram, I made my way through “The Divine Comedy,” helped as far as “Purgatory” by John Aitken Carlyle’s prose translation and then ascending the rest of the way on my own. I would do all my library work in the first hour and then steal away to the basement and pass the other five hours in reading or writing. I remember in this way rereading the six volumes of Gibbon’s “Decline and Fall” and the many volumes of Vicente Fidel López “History of the Argentine Republic.” I read Léon Bloy, Claudel, Groussac, and Bernard Shaw. On holidays, I translated Faulkner and Virginia Woolf. At some point, I was moved up to the dizzying height of Third Official. One morning, my mother rang me up and I asked for leave to go home, arriving just in time to see my father die. He had undergone a long agony and was very impatient for his death.

It was on Christmas Eve of 1938—the same year my father died—that I had a severe accident. I was running up a stairway and suddenly felt something brush my scalp. I had grazed a freshly painted open casement window. In spite of first-aid treatment, the wound became poisoned, and for a period of a week or so I lay sleepless every night and had hallucinations and high fever. One evening, I lost the power of speech and had to be rushed to the hospital for an immediate operation. Septicemia had set in, and for a month I hovered, all unknowingly, between life and death. (Much later, I was to write about this in my story “The South.”) When I began to recover, I feared for my mental integrity. I remember that my mother wanted to read to me from a book I had just ordered, C. S. Lewis’s “Out of the Silent Planet,” but for two or three nights I kept putting her off. At last, she prevailed, and after hearing a page or two I fell to crying. My mother asked me why the tears. “I’m crying because I understand,” I said. A bit later, I wondered whether I could ever write again. I had previously written quite a few poems and dozens of short reviews. I thought that if I tried to write a review now and failed, I’d be all through intellectually but that if I tried something I had never really done before and failed at that it wouldn’t be so bad and might even prepare me for the final revelation. I decided I would try to write a story. The result was “Pierre Menard, Author of ‘Don Quixote.’ ”

“Pierre Menard,” like its forerunner “The Approach to al-Mu’tasim,” was still a halfway house between the essay and the true tale. But the achievement spurred me on. I next tried something more ambitious—“Tlön, Ugbar, Orbis Tertius,” about the discovery of a new world that finally replaces our present world. Both were published in Victoria Ocampo’s magazine Sur . I kept up my writing at the library. Though my colleagues thought of me as a traitor for not sharing their boisterous fun, I went on with work of my own in the basement, or, when the weather was warm, up on the flat roof. My Kafkian story “The Library of Babel” was meant as a nightmare version or magnification of that municipal library, and certain details in the text have no particular meaning. The numbers of books and shelves that I recorded in the story were literally what I had at my elbow: Clever critics have worried over those ciphers, and generously endowed them with mystic significance. “The Lottery in Babylon,” “Death and the Compass,” and “The Circular Ruins” were also written, in whole or part, while I played truant. These tales and others were to become “The Garden of Branching Paths,” a book expanded and retitled “Ficciones” in 1944. “Ficciones” and “El Aleph” (1949 and 1952), my second story collection, are, I suppose, my two major books.

In 1946, a president whose name I do not want to remember came into power. One day soon after, I was honored with the news that I had been “promoted” out of the library to the inspectorship of poultry and rabbits in the public markets. I went to the City Hall to find out what it was all about. “Look here,” I said. “It’s rather strange that among so many others at the library I should be singled out as worthy of this new position.” “Well,” the clerk answered, “you were on the side of the Allies—what do you expect?” His statement was unanswerable; the next day, I sent in my resignation. My friends rallied round me at once and offered me a public dinner. I prepared a speech for the occasion but, knowing I was too shy to read it myself, I asked my friend Pedro Henríquez Ureña to read it for me.

I was now out of a job. Several months before, an old English lady had read my tea leaves and had foretold that I was soon to travel, to lecture, and to make vast sums of money thereby. When I told my mother about it, we both laughed, for public speaking was far beyond me. At this juncture, a friend came to the rescue, and I was made a teacher of English literature at the Asociación Argentina de Cultura Inglesa. I was also asked at the same time to lecture on classic American literature at the Colegio Libre de Estudios Superiores. Since this pair of offers was made three months before classes opened, I accepted, feeling quite safe. As the time grew near, however, I grew sicker and sicker. My series of nine lectures was to be on Hawthorne, Poe, Thoreau, Emerson, Melville, Whitman, Twain, Henry James, and Veblen. I wrote the first one down. But I had no time to write out the second one. Besides, thinking of the first lecture as Doomsday, I felt that only eternity could come after. The first one went off well enough—miraculously. Two nights before the second lecture, I took my mother for a long walk around Adrogué and had her time me as I rehearsed my talk. She said she thought it was overlong. “In that case,” I said, “I’m safe.” My fear had been of running dry. So, at forty-seven, I found a new and exciting life opening up for me. I travelled up and down Argentina and Uruguay, lecturing on Swedenborg, Blake, the Persian and Chinese mystics, Buddhism, gauchesco poetry, Martin Buber, the Kabbalah, the Arabian Nights, T. E. Lawrence, medieval Germanic poetry, the Icelandic sagas, Heine, Dante, Expressionism, and Cervantes. I went from town to town, staying overnight in hotels I‘d never see again. Sometimes my mother or a friend accompanied me. Not only did I end up making far more money than at the library but I enjoyed the work and felt that it justified me.

One of the chief events of these years—and of my life—was the beginning of my friendship with Adolfo Bioy-Casares. We met in 1930 or 1931, when he was about seventeen and I was just past thirty. It is always taken for granted in these cases that the older man is the master and the younger his disciple. This may have been true at the outset, but several years later, when we began to work together, Bioy was really and secretly the master. He and I attempted many different literary ventures. We compiled anthologies of Argentine poetry, tales of the fantastic, and detective stories; we wrote articles and forewords; we annotated Sir Thomas Browne and Gracián; we translated short stories by writers like Beerbohm, Kipling, Wells, and Lord Dunsany; we founded a magazine, Destiempo , which lasted three issues; we wrote film scripts, which were invariably rejected. Opposing my taste for the pathetic, the sententious, and the baroque, Bioy made me feel that quietness and restraint are more desirable. If I may be allowed a sweeping statement, Bioy led me gradually toward classicism.