So What Is Culture, Exactly?

THEPALMER/Getty Images

- Archaeology

- Ph.D., Sociology, University of California, Santa Barbara

- M.A., Sociology, University of California, Santa Barbara

- B.A., Sociology, Pomona College

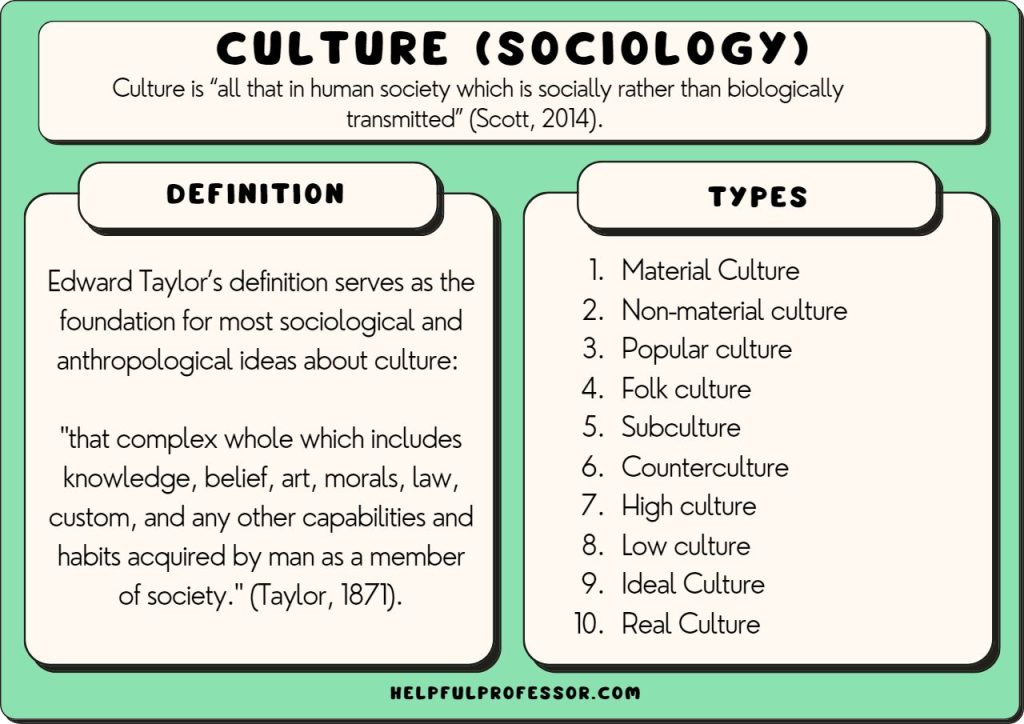

Culture is a term that refers to a large and diverse set of mostly intangible aspects of social life. According to sociologists, culture consists of the values, beliefs, systems of language, communication, and practices that people share in common and that can be used to define them as a collective. Culture also includes the material objects that are common to that group or society. Culture is distinct from social structure and economic aspects of society, but it is connected to them—both continuously informing them and being informed by them.

How Sociologists Define Culture

Culture is one of the most important concepts within sociology because sociologists recognize that it plays a crucial role in our social lives. It is important for shaping social relationships, maintaining and challenging social order, determining how we make sense of the world and our place in it, and in shaping our everyday actions and experiences in society. It is composed of both non-material and material things.

In brief, sociologists define the non-material aspects of culture as the values and beliefs, language, communication, and practices that are shared in common by a group of people. Expanding on these categories, culture is made up of our knowledge, common sense, assumptions, and expectations. It is also the rules, norms, laws, and morals that govern society; the words we use as well as how we speak and write them (what sociologists call " discourse "); and the symbols we use to express meaning, ideas, and concepts (like traffic signs and emojis, for example). Culture is also what we do and how we behave and perform (for example, theater and dance). It informs and is encapsulated in how we walk, sit, carry our bodies, and interact with others; how we behave depending on the place, time, and "audience;" and how we express identities of race, class, gender, and sexuality, among others. Culture also includes the collective practices we participate in, such as religious ceremonies, the celebration of secular holidays, and attending sporting events.

Material culture is composed of the things that humans make and use. This aspect of culture includes a wide variety of things, from buildings, technological gadgets, and clothing, to film, music, literature, and art, among others. Aspects of material culture are more commonly referred to as cultural products.

Sociologists see the two sides of culture—the material and non-material—as intimately connected. Material culture emerges from and is shaped by the non-material aspects of culture. In other words, what we value, believe, and know (and what we do together in everyday life) influences the things that we make. But it is not a one-way relationship between material and non-material culture. Material culture can also influence the non-material aspects of culture. For example, a powerful documentary film (an aspect of material culture) might change people’s attitudes and beliefs (i.e. non-material culture). This is why cultural products tend to follow patterns. What has come before in terms of music, film, television, and art, for example, influences the values, beliefs, and expectations of those who interact with them, which then, in turn, influence the creation of additional cultural products.

Why Culture Matters to Sociologists

Culture is important to sociologists because it plays a significant and important role in the production of social order. The social order refers to the stability of society based on the collective agreement to rules and norms that allow us to cooperate, function as a society, and live together (ideally) in peace and harmony. For sociologists, there are both good and bad aspects of social order.

Rooted in the theory of classical French sociologist Émile Durkheim , both material and non-material aspects of culture are valuable in that they hold society together. The values, beliefs, morals, communication, and practices that we share in common provide us with a shared sense of purpose and a valuable collective identity. Durkheim revealed through his research that when people come together to participate in rituals, they reaffirm the culture they hold in common, and in doing so, strengthen the social ties that bind them together. Today, sociologists see this important social phenomenon happening not only in religious rituals and celebrations like (some) weddings and the Indian festival of Holi but also in secular ones—such as high school dances and widely-attended, televised sporting events (for example, the Super Bowl and March Madness).

Famous Prussian social theorist and activist Karl Marx established the critical approach to culture in the social sciences. According to Marx, it is in the realm of non-material culture that a minority is able to maintain unjust power over the majority. He reasoned that subscribing to mainstream values, norms, and beliefs keep people invested in unequal social systems that do not work in their best interests, but rather, benefit the powerful minority. Sociologists today see Marx's theory in action in the way that most people in capitalist societies buy into the belief that success comes from hard work and dedication, and that anyone can live a good life if they do these things—despite the reality that a job which pays a living wage is increasingly hard to come by.

Both theorists were right about the role that culture plays in society, but neither was exclusively right. Culture can be a force for oppression and domination, but it can also be a force for creativity, resistance, and liberation. It is also a deeply important aspect of human social life and social organization. Without it, we would not have relationships or society.

Luce, Stephanie. " Living wages: a US perspective ." Employee Relations , vol. 39, no. 6, 2017, pp. 863-874. doi:10.1108/ER-07-2017-0153

- Definition of Cultural Materialism

- What is a Norm? Why Does it Matter?

- The Concept of Collective Consciousness

- All About Marxist Sociology

- How Do Sociologists Define Consumption?

- Introduction to Sociology

- The Challenges of Ethical Living in a Consumer Society

- The Sociology of Race and Ethnicity

- The Importance Customs in Society

- Overview of Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft in Sociology

- What Is the Meaning of Globalization in Sociology?

- Understanding Diffusion in Sociology

- Understanding Socialization in Sociology

- Olmec Religion

- The History of Sociology Is Rooted in Ancient Times

- How Emile Durkheim Made His Mark on Sociology

3.1 What Is Culture?

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Differentiate between culture and society

- Explain material versus nonmaterial culture

- Discuss the concept of cultural universals as it relates to society

- Compare and contrast ethnocentrism and xenocentrism

Humans are social creatures. According to Smithsonian Institution research, humans have been forming groups for almost 3 million years in order to survive. Living together, people formed common habits and behaviors, from specific methods of childrearing to preferred techniques for obtaining food.

Almost every human behavior, from shopping to marriage, is learned. In the U.S., marriage is generally seen as an individual choice made by two adults, based on mutual feelings of love. In other nations and in other times, marriages have been arranged through an intricate process of interviews and negotiations between entire families. In Papua New Guinea, almost 30 percent of women marry before the age of 18, and 8 percent of men have more than one wife (National Statistical Office, 2019). To people who are not from such a culture, arranged marriages may seem to have risks of incompatibility or the absence of romantic love. But many people from cultures where marriages are arranged, which includes a number of highly populated and modern countries, often prefer the approach because it reduces stress and increases stability (Jankowiak 2021).

Being familiar with unwritten rules helps people feel secure and at ease. Knowing to look left instead of right for oncoming traffic while crossing the street can help avoid serious injury and even death. Knowing unwritten rules is also fundamental in understanding humor in different cultures. Humor is common to all societies, but what makes something funny is not. Americans may laugh at a scene in which an actor falls; in other cultures, falling is never funny. Most people want to live their daily lives confident that their behaviors will not be challenged or disrupted. But even an action as seemingly simple as commuting to work evidences a great deal of cultural propriety, that is, there are a lot of expected behaviors. And many interpretations of them.

Take the case of going to work on public transportation. Whether people are commuting in Egypt, Ireland, India, Japan, and the U.S., many behaviors will be the same and may reveal patterns. Others will be different. In many societies that enjoy public transportation, a passenger will find a marked bus stop or station, wait for the bus or train, pay an agent before or after boarding, and quietly take a seat if one is available. But when boarding a bus in Cairo, Egypt, passengers might board while the bus is moving, because buses often do not come to a full stop to take on patrons. In Dublin, Ireland, bus riders would be expected to extend an arm to indicate that they want the bus to stop for them. And when boarding a commuter train in Mumbai, India, passengers must squeeze into overstuffed cars amid a lot of pushing and shoving on the crowded platforms. That kind of behavior might be considered rude in other societies, but in Mumbai it reflects the daily challenges of getting around on a train system that is taxed to capacity.

Culture can be material or nonmaterial. Metro passes and bus tokens are part of material culture, as are the buses, subway cars, and the physical structures of the bus stop. Think of material culture as items you can touch-they are tangible . Nonmaterial culture , in contrast, consists of the ideas, attitudes, and beliefs of a society. These are things you cannot touch. They are intangible . You may believe that a line should be formed to enter the subway car or that other passengers should not stand so close to you. Those beliefs are intangible because they do not have physical properties and can be touched.

Material and nonmaterial aspects of culture are linked, and physical objects often symbolize cultural ideas. A metro pass is a material object, but it represents a form of nonmaterial culture, namely, capitalism, and the acceptance of paying for transportation. Clothing, hairstyles, and jewelry are part of material culture, but the appropriateness of wearing certain clothing for specific events reflects nonmaterial culture. A school building belongs to material culture symbolizing education, but the teaching methods and educational standards are part of education’s nonmaterial culture.

As people travel from different regions to entirely different parts of the world, certain material and nonmaterial aspects of culture become dramatically unfamiliar. What happens when we encounter different cultures? As we interact with cultures other than our own, we become more aware of the differences and commonalities between others and our own. If we keep our sociological imagination awake, we can begin to understand and accept the differences. Body language and hand gestures vary around the world, but some body language seems to be shared across cultures: When someone arrives home later than permitted, a parent or guardian meeting them at the door with crossed arms and a frown on their face means the same in Russia as it does in the U.S. as it does in Ghana.

Cultural Universals

Although cultures vary, they also share common elements. Cultural universals are patterns or traits that are globally common to all societies. One example of a cultural universal is the family unit: every human society recognizes a family structure that regulates sexual reproduction and the care of children. Even so, how that family unit is defined and how it functions vary. In many Asian cultures, for example, family members from all generations commonly live together in one household. In these cultures, young adults continue to live in the extended household family structure until they marry and join their spouse’s household, or they may remain and raise their nuclear family within the extended family’s homestead. In the U.S., by contrast, individuals are expected to leave home and live independently for a period before forming a family unit that consists of parents and their offspring. Other cultural universals include customs like funeral rites, weddings, and celebrations of births. However, each culture may view and conduct the ceremonies quite differently.

Anthropologist George Murdock first investigated the existence of cultural universals while studying systems of kinship around the world. Murdock found that cultural universals often revolve around basic human survival, such as finding food, clothing, and shelter, or around shared human experiences, such as birth and death or illness and healing. Through his research, Murdock identified other universals including language, the concept of personal names, and, interestingly, jokes. Humor seems to be a universal way to release tensions and create a sense of unity among people (Murdock, 1949). Sociologists consider humor necessary to human interaction because it helps individuals navigate otherwise tense situations.

Sociological Research

Is music a cultural universal.

Imagine that you are sitting in a theater, watching a film. The movie opens with the protagonist sitting on a park bench with a grim expression on their face. The music starts to come in. The first slow and mournful notes play in a minor key. As the melody continues, the heroine turns her head and sees a man walking toward her. The music gets louder, and the sounds don’t seem to go together – as if the orchestra is intentionally playing the wrong notes. You tense up as you watch, almost hoping to stop. The character is clearly in danger.

Now imagine that you are watching the same movie – the exact same footage – but with a different soundtrack. As the scene opens, the music is soft and soothing, with a hint of sadness. You see the protagonist sitting on the park bench with a grim expression. Suddenly, the music swells. The woman looks up and sees a man walking toward her. The notes are high and bright, and the pace is bouncy. You feel your heart rise in your chest. This is a happy moment.

Music has the ability to evoke emotional responses. In television shows, movies, commercials, and even the background music in a store, music has a message and seems to easily draw a response from those who hear it – joy, sadness, fear, victory. Are these types of musical cues cultural universals?

In 2009, a team of psychologists, led by Thomas Fritz of the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany, studied people’s reactions to music that they’d never heard (Fritz et al., 2009). The research team traveled to Cameroon, Africa, and asked Mafa tribal members to listen to Western music. The tribe, isolated from Western culture, had never been exposed to Western culture and had no context or experience within which to interpret its music. Even so, as the tribal members listened to a Western piano piece, they were able to recognize three basic emotions: happiness, sadness, and fear. Music, the study suggested, is a sort of universal language.

Researchers also found that music can foster a sense of wholeness within a group. In fact, scientists who study the evolution of language have concluded that originally language (an established component of group identity) and music were one (Darwin, 1871). Additionally, since music is largely nonverbal, the sounds of music can cross societal boundaries more easily than words. Music allows people to make connections, where language might be a more difficult barricade. As Fritz and his team found, music and the emotions it conveys are cultural universals.

Ethnocentrism and Cultural Relativism

Although human societies have much in common, cultural differences are far more prevalent than cultural universals. For example, while all cultures have language, analysis of conversational etiquette reveals tremendous differences. In some Middle Eastern cultures, it is common to stand close to others in conversation. Americans keep more distance and maintain a large “personal space.” Additionally, behaviors as simple as eating and drinking vary greatly from culture to culture. Some cultures use tools to put the food in the mouth while others use their fingers. If your professor comes into an early morning class holding a mug of liquid, what do you assume they are drinking? In the U.S., it’s most likely filled with coffee, not Earl Grey tea, a favorite in England, or Yak Butter tea, a staple in Tibet.

Some travelers pride themselves on their willingness to try unfamiliar foods, like the late celebrated food writer Anthony Bourdain (1956-2017). Often, however, people express disgust at another culture's cuisine. They might think that it’s gross to eat raw meat from a donkey or parts of a rodent, while they don’t question their own habit of eating cows or pigs.

Such attitudes are examples of ethnocentrism , which means to evaluate and judge another culture based on one’s own cultural norms. Ethnocentrism is believing your group is the correct measuring standard and if other cultures do not measure up to it, they are wrong. As sociologist William Graham Sumner (1906) described the term, it is a belief or attitude that one’s own culture is better than all others. Almost everyone is a little bit ethnocentric.

A high level of appreciation for one’s own culture can be healthy. A shared sense of community pride, for example, connects people in a society. But ethnocentrism can lead to disdain or dislike of other cultures and could cause misunderstanding, stereotyping, and conflict. Individuals, government, non-government, private, and religious institutions with the best intentions sometimes travel to a society to “help” its people, because they see them as uneducated, backward, or even inferior. Cultural imperialism is the deliberate imposition of one’s own cultural values on another culture.

Colonial expansion by Portugal, Spain, Netherlands, and England grew quickly in the fifteenth century was accompanied by severe cultural imperialism. European colonizers often viewed the people in these new lands as uncultured savages who needed to adopt Catholic governance, Christianity, European dress, and other cultural practices.

A modern example of cultural imperialism may include the work of international aid agencies who introduce agricultural methods and plant species from developed countries into areas that are better served by indigenous varieties and agricultural approaches to the particular region. Another example would be the deforestation of the Amazon Basin as indigenous cultures lose land to timber corporations.

When people find themselves in a new culture, they may experience disorientation and frustration. In sociology, we call this culture shock . In addition to the traveler’s biological clock being ‘off’, a traveler from Chicago might find the nightly silence of rural Montana unsettling, not peaceful. Now, imagine that the ‘difference’ is cultural. An exchange student from China to the U.S. might be annoyed by the constant interruptions in class as other students ask questions—a practice that is considered rude in China. Perhaps the Chicago traveler was initially captivated with Montana’s quiet beauty and the Chinese student was originally excited to see a U.S.- style classroom firsthand. But as they experience unanticipated differences from their own culture, they may experience ethnocentrism as their excitement gives way to discomfort and doubts about how to behave appropriately in the new situation. According to many authors, international students studying in the U.S. report that there are personality traits and behaviors expected of them. Black African students report having to learn to ‘be Black in the U.S.’ and Chinese students report that they are naturally expected to be good at math. In African countries, people are identified by country or kin, not color. Eventually, as people learn more about a culture, they adapt to the new culture for a variety of reasons.

Culture shock may appear because people aren’t always expecting cultural differences. Anthropologist Ken Barger (1971) discovered this when he conducted a participatory observation in an Inuit community in the Canadian Arctic. Originally from Indiana, Barger hesitated when invited to join a local snowshoe race. He knew he would never hold his own against these experts. Sure enough, he finished last, to his mortification. But the tribal members congratulated him, saying, “You really tried!” In Barger’s own culture, he had learned to value victory. To the Inuit people, winning was enjoyable, but their culture valued survival skills essential to their environment: how hard someone tried could mean the difference between life and death. Over the course of his stay, Barger participated in caribou hunts, learned how to take shelter in winter storms, and sometimes went days with little or no food to share among tribal members. Trying hard and working together, two nonmaterial values, were indeed much more important than winning.

During his time with the Inuit tribe, Barger learned to engage in cultural relativism . Cultural relativism is the practice of assessing a culture by its own standards rather than viewing it through the lens of one’s own culture. Practicing cultural relativism requires an open mind and a willingness to consider, and even adapt to, new values, norms, and practices.

However, indiscriminately embracing everything about a new culture is not always possible. Even the most culturally relativist people from egalitarian societies—ones in which women have political rights and control over their own bodies—question whether the widespread practice of female genital mutilation in countries such as Ethiopia and Sudan should be accepted as a part of cultural tradition. Sociologists attempting to engage in cultural relativism, then, may struggle to reconcile aspects of their own culture with aspects of a culture that they are studying. Sociologists may take issue with the practices of female genital mutilation in many countries to ensure virginity at marriage just as some male sociologists might take issue with scarring of the flesh to show membership. Sociologists work diligently to keep personal biases out of research analysis.

Sometimes when people attempt to address feelings of ethnocentrism and develop cultural relativism, they swing too far to the other end of the spectrum. Xenocentrism is the opposite of ethnocentrism, and refers to the belief that another culture is superior to one’s own. (The Greek root word xeno-, pronounced “ZEE-no,” means “stranger” or “foreign guest.”) An exchange student who goes home after a semester abroad or a sociologist who returns from the field may find it difficult to associate with the values of their own culture after having experienced what they deem a more upright or nobler way of living. An opposite reaction is xenophobia, an irrational fear or hatred of different cultures.

Perhaps the greatest challenge for sociologists studying different cultures is the matter of keeping a perspective. It is impossible for anyone to overcome all cultural biases. The best we can do is strive to be aware of them. Pride in one’s own culture doesn’t have to lead to imposing its values or ideas on others. And an appreciation for another culture shouldn’t preclude individuals from studying it with a critical eye. This practice is perhaps the most difficult for all social scientists.

Sociology in the Real World

Overcoming culture shock.

During her summer vacation, Caitlin flew from Chicago, Illinois to Madrid, Spain to visit Maria, the exchange student she had befriended the previous semester. In the airport, she heard rapid, musical Spanish being spoken all around her.

Exciting as it was, she felt isolated and disconnected. Maria’s mother kissed Caitlin on both cheeks when she greeted her. Her imposing father kept his distance. Caitlin was half asleep by the time supper was served—at 10 p.m. Maria’s family sat at the table for hours, speaking loudly, gesturing, and arguing about politics, a taboo dinner subject in Caitlin’s house. They served wine and toasted their honored guest. Caitlin had trouble interpreting her hosts’ facial expressions, and did not realize she should make the next toast. That night, Caitlin crawled into a strange bed, wishing she had not come. She missed her home and felt overwhelmed by the new customs, language, and surroundings. She’d studied Spanish in school for years—why hadn’t it prepared her for this?

What Caitlin did not realize was that people depend not only on spoken words but also on body language, like gestures and facial expressions, to communicate. Cultural norms and practices accompany even the smallest nonverbal signals (DuBois, 1951). They help people know when to shake hands, where to sit, how to converse, and even when to laugh. We relate to others through a shared set of cultural norms, and ordinarily, we take them for granted.

For this reason, culture shock is often associated with traveling abroad, although it can happen in one’s own country, state, or even hometown. Anthropologist Kalervo Oberg (1960) is credited with first coining the term “culture shock.” In his studies, Oberg found that most people are excited at first to encounter a new culture. But bit by bit, they become stressed by interacting with people from a different culture who speak another language and use different regional expressions. There is new food to digest, new daily schedules to follow, and new rules of etiquette to learn. Living with this constant stress can make people feel incompetent and insecure. People react to frustration in a new culture, Oberg found, by initially rejecting it and glorifying one’s own culture. An American visiting Italy might long for a “real” pizza or complain about the unsafe driving habits of Italians.

It helps to remember that culture is learned. Everyone is ethnocentric to an extent, and identifying with one’s own country is natural. Caitlin’s shock was minor compared to that of her friends Dayar and Mahlika, a Turkish couple living in married student housing on campus. And it was nothing like that of her classmate Sanai. Sanai had been forced to flee war-torn Bosnia with her family when she was fifteen. After two weeks in Spain, Caitlin had developed more compassion and understanding for what those people had gone through. She understood that adjusting to a new culture takes time. It can take weeks or months to recover from culture shock, and it can take years to fully adjust to living in a new culture.

By the end of Caitlin’s trip, she had made new lifelong friends. Caitlin stepped out of her comfort zone. She had learned a lot about Spain, but discovered a lot about herself and her own culture.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 3e

- Publication date: Jun 3, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/3-1-what-is-culture

© Jan 18, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of culture

(Entry 1 of 2)

Definition of culture (Entry 2 of 2)

transitive verb

- accomplishment

- civilization

- cultivation

Examples of culture in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'culture.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Noun and Verb

Middle English, cultivated land, cultivation, from Anglo-French, from Latin cultura , from cultus , past participle — see cult

15th century, in the meaning defined at sense 4

1510, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Phrases Containing culture

- culture shock

- culture of success

- self - culture

- cancel culture

- co - culture

- tissue culture

- Maker culture

Articles Related to culture

Words of the Year: A Decade in Review

Let’s take a look at a decade in words.

Back to School Vocabulary

Word lookups that spike in September

2014 Word of the Year: Culture

Here's What this Year's Top Lookups Say About Us

Dictionary Entries Near culture

culture and personality

Cite this Entry

“Culture.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/culture. Accessed 7 Apr. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of culture.

Kids Definition of culture (Entry 2 of 2)

Medical Definition

Medical definition of culture.

Medical Definition of culture (Entry 2 of 2)

More from Merriam-Webster on culture

Nglish: Translation of culture for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of culture for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about culture

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

The tangled history of 'it's' and 'its', more commonly misspelled words, why does english have so many silent letters, your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - apr. 5, 12 bird names that sound like compliments, 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 12 more bird names that sound like insults (and sometimes are), 8 uncommon words related to love, games & quizzes.

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Analysis of T.S. Eliot’s Notes towards the Definition of Culture

Analysis of T.S. Eliot’s Notes towards the Definition of Culture

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on July 5, 2020 • ( 0 )

Notes towards the Definition of Culture (1948) Eliot himself gives an uncustomarily detailed account of the publication of Notes towards the Definition of Culture in his brief preface to the booklength edition first published in November 1948. Four years earlier, what he calls “a preliminary sketch” of the eventual work was published, under the same title, in three consecutive issues of The New English Weekly, accounting for Eliot’s apparent coyness later in calling such a thoughtful work, as the completed study turned out to be, mere “notes.” He goes on to tell his readers that those preliminary notes were subsequently perfected into a longer paper, “Cultural Forces in the Human Order,” and published in a 1945 volume, Prospect for Christendom . Revised, it is the first chapter of the finished book. He also tells his readers that the second chapter is a revised version of a paper first published in The New English Review in October 1945, and that there is an appendix compiled from three radio broadcasts he had made, in German, to the German people in 1946.

While Eliot may not have had any specific intention behind presenting such a detailed bibliographical history for the material at hand, the reader ought to be impressed by the fact that the ideas expressed therein did not simply spring full-blown onto the page in some effort of Eliot’s to write a book on the topic, but were themselves the products of much working out of issues and nuances over an extended period of time and in a variety of contexts and venues. One can go further than that, however. So much did Eliot’s literary criticism begin to merge with social criticism, social criticism with religious criticism, and religious criticism with cultural criticism, that anyone would have to say that Notes towards the Definition of Culture, his last major published prose work, is a culmination of Eliot’s thinking to date on a wide range of issues, all of which can be safely gathered together under the single heading, culture, at least inasmuch as he will set about defining the term. So much, indeed, are these earlier positions and opinions, though modified, embedded in the text of Notes that, for the sake of moving on into a consideration of its content, it would be more effective to contrast Eliot’s earlier with his present views as these relevant issues are raised and brought to bear by him the pages of Notes towards the Definition of Culture.

Eliot states at the outset that his sole purpose, rather than to propose a social or political philosophy, is to define culture , a term that he feels “has come to be misused.” He imagines that, as a result, perhaps, of the destructiveness of the recent war, the term has come to be used by journalists, for example, as if it were a term synonymous with civilization. Eliot does not deny that those two words may be interchangeable in certain contexts, so his aim is not to erect any artificial distinctions between them but to define the one, culture, in such a way that it will not continue to be easily mistaken for being a synonym for “art” in general or, even more vaguely, for “a kind of emotional stimulant.” It is the latter case that he implies, and fears, is becoming the more and more common.

As he outlines his approach to the topic in the coming essay, Eliot also reveals, of course, his personal bias, which is that there is a relation between culture and religion, so much so, indeed, that “the culture [of a people] will appear to be the product of the religion, or the religion the product of the culture.” Furthermore, he believes that a culture is “organic,” that is, that it grows and changes so that it may be transmitted through succeeding generations; that it should be reducible to more and more local manifestations, as is implied by regionalism; and that, as far as religion is concerned, it should reflect both unity and diversity.

By way of an example of his meaning here, readers familiar with the ideas that Eliot had already expressed in his book-length essay The Idea of a Christian Society a decade earlier would already be acquainted with his hope that, at least in the Christian nations of Western Europe, a universality of doctrine would be mitigated, but not diluted, by local devotional custom and practice. Where these three conditions—transmission through generations, regional flexibility, and diversity in unity—are not met, Eliot goes as far to say, a high civilization is not possible.

Finally, Eliot promises that any such discussion must close itself by “disentangling” just such a definition of culture from any consideration of the educational and political life of the community. Here Eliot freely admits that he is liable to trample on what others may regard as sacred ground by appearing to be elitist or exclusive in his definition of culture. That, however, he argues, underscores his very reason for wishing to define the term: If a culture is to be sacrificed in the name of other social and political goals, so be it, Eliot would say. But, he would add, let it be clear what one means to sacrifice when they speak of sacrificing culture.

This is an Eliot who, far back in his own career as a social commentator, in essays such as The Function of Criticism in 1923 and After Strange Gods in 1934, had been arguing, sometimes stridently but always with a passionate cogency, against literary and other intellectual forces that he saw to be at enmity with his own cherished beliefs and attitudes. Now he appears to be ready to accept that such intellectual and moral conflict is inevitable as long as it is recognized as a necessary conflict, not as a foregone conclusion. He seems to be ready to make peace with those positions with which he does not agree by continuing to explain why he does not agree with them rather than by trying to present the opposing position as patently disagreeable, as he had done in many an earlier diatribe.

Here now, Eliot makes every effort to establish himself as one who is opposed neither to change nor to opposition. Rather, he is opposed to those who “have believed in particular changes as good in themselves, without worrying about the future of civilisation, and without finding it necessary to recommend their innovations by the specious glitter of unmeaning promises.” Eliot would like to see enter such dialogues a “permanent standard” by which one could compare one civilization with another, not just one’s own with others’, but one’s own with the civilization that it has been at various times or may be becoming. So, then, his essay will ask “whether there are any permanent conditions, in the absence of which no higher culture can be expected.” Culture, for Eliot, is not something that one can “deliberately aim at” achieving, nor, one might suspect, changing either. The conditions of culture, he asserts as he concludes his introduction, are “natural” to human beings. If he places quotation marks around the word natural, it is only to suggest that one need not know what it means in order to recognize that it does nevertheless apply. In any event, it will be this emphasis on the naturalness of culture, as opposed to the idea, for example, that it can or should be consciously manipulated, that the reader should keep in mind, for Eliot certainly will as he continues to frame his definition.

In his first chapter, Eliot discusses “The Three Senses of ‘Culture.’ ” (Again, putting quotation marks around the word culture reminds the reader that these are uncharted seas that nevertheless seem deceptively familiar.) Culture, then, can describe the development of an individual, he says, a group or class, or the society as a whole. Since the last comprises the other two, it is there that he wishes to begin. Normally, however, it has been the other way around, Eliot argues, for he demonstrates convincingly that sociological and other treatments of culture, such as Matthew Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy, generally begin and end by focusing on the class or group if not even, as in Arnold’s case, just the individual. Such lapses, Eliot contends, give the term culture the “thinness” with which it is often popularly associated.

Furthermore, there are various contexts in which one may think of culture—in terms of manners, for example, or of learning, of philosophy, or of the arts—and these are all too often neither taken into account or accounted for. The net result is that people are thus encouraged to think of themselves as persons of culture when they are versed in one area of it but are totally unaware that there are other areas as well.

Eliot’s point is that all these various senses, then, and all these various levels of culture must be taken into account in a coherent manner if anything approaching an adequate definition can ever hope to be achieved. These various characteristics and categories of culture overlap; there is, for example, even in more primitive cultures, distinct separation between art and religion or between the activities of the individual and the goals of the group. The more advanced a culture, the more abstract distinctions are forced on these critical activities of any culture, specifically, religion, science, politics, and art, so that there begin equally abstract struggles for dominance of one over the other three. Those tensions, Eliot argues, may further become tensions within individuals, citing for his example the contention between the demands of the state and the demands of the church that form the basis for the tragedy in Sophocles’ Antigone.

A culture in which these kinds of conflicts begin to occur represents a very advanced stage of civilization, Eliot proposes, for it requires an audience already aware of those tensions in order for a dramatist to articulate them.

Little by little then, the culture of the class or group emerges from the intracultural tensions formed between the individual and society. These more highly cultured groups—groups, that is, whose motive for being is shaped by cultural tensions—lead to further specialization, and that, of course, can lead to cultural disintegration, a point that enables Eliot to begin to focus his discussion on the contemporary scene. “Cultural disintegration,” he writes, “is present when two or more strata so separate that these become in effect distinct cultures,” and this can result from a separation of classes as well. The religious sensibility becomes separated and distinct from the artistic, for example, or manners become a class distinction unique to a particular economic stratum within the society. This process of disintegration and stratification leads inevitably to a decline of the total culture, a decline manifested, internally, in social ailments and, on a global scale, in relations among nations. In the latter case, it becomes a matter of defining a nation or people in terms of its state or political identity rather than on the basis of each people’s own cultural cohesion, abstracting human-to-human interaction all that much more. These difficulties ultimately influence matters of education as trivial-seeming on the surface as the decline of a national cuisine, since that implies a lack of cohesion in the culture resulting in a disconnect between the requirements of life and the quality of life. “Culture,” Eliot can say at this juncture, “may even be described simply as that which makes life worth living.”

Thus, Eliot’s presentation arrives at a critical moment: “[N]o culture can appear or develop except in relation to a religion.” Indeed, Eliot goes even further in linking a people’s culture to their belief system by noting that all that he has just said by way of describing how a culture may decline and disintegrate may also be said of the same phenomena as they would occur in the history of a religion. Here, of course, he can again bring to bear as evidence present conditions in Western Europe, a situation that he had already addressed in 1939 in The Idea of a Christian Society. The divergence of belief in Christianity that commenced in the 16th century may not be, in Eliot’s view, anywhere near as pernicious a sign of its decline as a cultural mainstay as much as an increasing tradition of a nurtured skepticism is. Not only can culture, as Eliot views it, not be preserved or extended in the absence of religion, but in the absence of a religious foundation, it is possible, Eliot is afraid, to adopt an indifferent attitude toward culture.

Rather, Eliot would like to imagine a society in which “both ‘religion’ and ‘culture’ . . . should mean for the individual and for the group something toward which they strive, not merely something which they possess.” Religion can thus be “the whole way of life of a people, . . . and that way of life is also its culture,” or it may be a way of life that a people share with other peoples but with whom they do not share a common culture, as in the case of Christian Europe. Ultimately, then, if culture “includes all the characteristic activities and interests of a people”— and here Eliot cites numerous English interests and activities as disparate as Derby Day and beetroot in vinegar—then all those interests and activities are “also a part of our lived religion.”

But if culture is a people’s lived religion, the converse is not necessarily true: that religion is a people’s lived culture. “[T]he actual religion of no European people has ever been purely Christian, or purely anything.” Indeed, Eliot contends, “behaviour is also belief,” and the purity of line between how a people believe and how a people behave colors every aspect of their being and constitutes, ultimately, what may be called their culture, even if it is not seen exclusively as their religion. Or, as Eliot puts it, “bishops are a part of English culture, and horses and dogs are a part of English religion.” Put yet another way, a people’s culture is “an incarnation of its religion,” no matter how well they profess the particular faith that they otherwise adhere to. The truth or falsity of a faith, then, does not matter as far as culture is concerned, so that a people with a “truer light” may have a culture inferior to a people who live a lesser faith with a greater intensity.

Eliot is wise to avoid particular examples, but who would deny that a people who do not believe in the values by which the culture claims that lives ought to be led are leading a sham cultural existence that cannot long sustain itself? Eliot therefore can conclude his first chapter by proposing that “any religion, while it lasts, . . . gives an apparent meaning to life, provides the framework for a culture, and protects the mass of humanity from boredom and despair.”

Eliot begins his next chapter, “The Class and the Elite,” by carefully addressing two sensitive issues even for his time: the notion of higher civilizations versus lower or primitive societies, and the notion of cultural elites.

It has understandably become more and more difficult if not embarrassing to pronounce a particular way of life as more “advanced” than another or a particular social class as more inherently privileged than another, yet qualitative differences, whether or not such distinctions are openly addressed by a society, are made nevertheless and permeate every human society. Indeed the potential for allowing the pernicious nature of these ways of thinking and of behaving to dominate a society’s way of life and treatment of others is increased especially when distinctions of that kind are not openly addressed, analyzed, and questioned. For then it becomes an unspoken commonplace that the making of such judgments is “the way it’s always been done.”

Eliot’s addressing the entire matter, then, forms a very real part of the analysis that he is carrying on in order not to prescribe but to describe those elements that constitute a “definition of culture.” Seen from that perspective, his interest in describing how class and, ultimately, a class of elites eventually emerges in so-called higher civilizations is a way neither of justifying or condemning such a state of affairs but, rather, a necessary part of the analytical processes that enable definition. That said, Eliot quickly in his second chapter establishes a fact that is presented not as something to be praised or lamented, but merely understood. While a classless society remains the ideal at higher stages of development, a culture divides into classes. Higher classes emerge wherein “superior individuals” in political administration, the arts, science, philosophy, and physical prowess form “into suitable groups, endowed with appropriate powers, and perhaps with varied emoluments and honours.” These groups, he tells his readers, telling them nothing that they do not already know, “are what we call élites.”

Not to belabor the matter, but it is necessary for the reader to note that Eliot is neither defending nor attacking a cultural elitism, only describing the manner in which such a state of affairs comes about. Indeed, he imagines that at some future point in the development of a society stratified by class distinctions, congregations of elites will replace class structure by transcending it. Today such an idea might be called a meritocracy, and it seems to foster its own inequitable divisions.

Nevertheless, all that Eliot is really suggesting is that when a culture begins to identify inherent skill and talent, class distinctions are seen for the artificial criteria that they are and thus class is not a measure or reflection of the relative merits of an individual’s potential for contributing to the larger community. The result of the emergence of elites would, therefore, be that “all positions in society should be occupied by those who are best fitted to exercise the functions of the positions.” The danger of investing all cultural integrity in the hands of elites, however, is that they tend to become further and further isolated, one group from another, whereas the notion that there is within a culture, guiding and forming it, the elite enables its various groupings to interact more harmoniously for the common good.

Eliot takes up the views of Dr. Karl Mannheim to espouse his own opposing view. Mannheim, Eliot tells his readers, fails to distinguish between elites, with their tendency to cluster and become isolated in their various fields, and the elite, who through separate interests would nevertheless operate in concert in support of the common interest of a common culture. This elite may represent or be constituted of the ruling or governing class in some instances, but “in concerning ourselves with class versus élites,” which is what for Eliot has been a primary focus of his argument throughout, “we are concerned with the total culture of a country, and that involves a good deal more than government.”

It may be that, rather than a “classless” society, Eliot is making a case for what a society should want its so-called “ruling” class to be. So, then, “[w]hat is important is a structure in which there will be, from ‘top’ to ‘bottom,’ a continuous gradation of cultural levels.” This culture must, meanwhile, be transmitted primarily by the family rather than what Eliot calls educationists, inasmuch as the latter will dispute whether or not there ought to be a class structure present in the society at all, while the family, rather than concerning itself with the pros and cons of a class structure, will naturally represent the values of the culture in miniature, whatever class the particular family embodies or belongs to.

However, in order to ensure the viability of the family unit, Eliot ends his second chapter with what sounds like an impossible requirement for a modern industrial state such as England: that there must be “groups of families persisting, from generation to generation, each in the same way of life.” And he follows that stipulation by sounding once more his ominous caution that while such conditions may not bring about a higher civilization, “when they are absent, the higher civilization is unlikely to be found.”

Eliot’s chapters 3 and 4 are continuations of each other, inasmuch as he now sets out to describe how a unified culture must nevertheless both enable and express diversity in order to remain viable. In a manner of speaking, Eliot’s entire essay throughout to this point has been tacitly endorsing the same proposition, what with its talk of higher and lower levels of society acting in concert to make a way of national life constitute what, by his definition, can be rightfully called a culture. None of this should come as any surprise to present-day readers, who should already be well schooled in the idea that differences among and between groups and regions, nations and peoples, are both inevitable and welcomed.

Eliot’s contemporary readers would have been as equally well versed in that same proposition, however. Those political organizations that are now defined as “nations,” which may by now seem to have been the building blocks of diverse human societies since time immemorial, are actually fairly recent historical developments. There was not, for example, any such political entity as Germany or Italy before 1865, less than 100 years before the time of Eliot’s writing, and even Great Britain’s “United Kingdom” of England, Scotland, and Ireland is a political invention of the late 18th century. For Eliot to speak of regions and sects and cults within the context of a Christianized Western Europe is mandatory, then, since post-Reformation Europe, even within the relatively insular realms of the British Isles, had long ago become as fragmented religiously as it had always been regionally and, in the oldest sense of the term, tribally.

“Unity and Diversity,” the general title that Eliot gives to chapters 3 and 4, is hardly proposed as an original conceptualization by Eliot, who then discusses “The Region” in his third chapter and “Sect and Cult” in his fourth. Instead, it is his yielding to the social, spiritual, ethnic, and even geographical realities of the varied peoples of the very English culture that he had earlier defined as the “whole life of the whole people.” If these two chapters have a common thesis, as Eliot’s titulary way of linking them suggests that they do, it can be found in the epigraph from the 20th-century British thinker A. N. Whitehead’s Science and the Modern World that Eliot cites at the opening of chapter 3: “A diversification among human communities is essential. . . . Other nations of different habits are not enemies: they are godsends. Men require of their neighbours something sufficiently akin to be understood, something sufficiently different to provoke attention, and something great enough to command admiration.”

In summary, if differences inspire competition, that competition ought to be itself inspired by emulation. From that, the health of the entire human community emerges. What is true of the benefits of a healthy diversity between nations and peoples, Eliot happily and wisely contends in his next two chapters, must be true as well of the diversity among an otherwise common people sharing what, from the outsider’s point of view, appears to be a common culture.

Eliot’s is always the time-honored media via, middle way, of the Anglican tradition of England that was itself inspired by that people’s desire, during the Reformation, to be free of the dominance of what they regarded as a foreign culture, Rome’s, over their national religion and yet to remain true, by and large, to long-standing Catholic Christian practices, rituals, and devotions. Thus, Eliot is always taking pains to point out that a totally classless society is as pernicious to the maintenance and growth of a healthy national culture as a society that is very rigidly organized by class distinctions.

Rather, he writes, “[t]he unity with which I am concerned must be largely unconscious,” that is to say, it should not be something that is being perpetually identified and celebrated, “and therefore can perhaps be best approached through a consideration of the useful diversities.” Region is one. Citizens, then, should be encouraged to think of themselves as citizens not of the nation, but “of a particular part of [their] country, with local loyalties.” By the same token and in the same spirit, however, one’s loyalty to a locality or region, no matter how exotic or unique its cultural heritage may seem to be in its own right, cannot be fostered in such a way that it ends up taking precedence over one’s sense of belonging to those ever-enlarging groups that eventually make up the whole people and the whole culture.

Nor is this sense of locality or region limited to geographical entities, even when it may seem to be defined or interpreted in that manner. Dialects provide a point of immediate reference, and Eliot uses the Irish for an example. While as a people they had long since, at least in Eliot’s time, lost their own language and were for the most part, as a result of English colonial policies in Ireland, English- speaking, the English that they speak retains idiomatic and other markers of their original Gaelic tongue. Furthermore, it would be unfair to define their ethnic background and the dialect and other idiosyncratic habits that have emerged from it as distinctions peculiar of a region inasmuch as Irish could be found in every major metropolis in England itself. Still, such distinctions can nevertheless be identified as “regional” for all the other reasons already cited.

These satellite cultures, as Eliot comes to call them, using Ireland, Scotland, and Wales as outstanding examples, must be encouraged to maintain and nurture their original identities as well, but not so much as to cut themselves off completely from the primary culture, in this case England’s, through which they are linked to Europe and, through Europe, the world. Eliot does take a tangent here, however, that may not find universal agreement. When a satellite culture has become united by language to another, he argues, it ought to abandon its own language in favor of the central culture for literary purposes. This sort of cultural imperialism should certainly strike most as inexcusable, including even Eliot, who only a few years earlier, in “The Social Function of Literature,” had rightfully commended the Norwegians, just recently liberated from the control of Nazi Germany, for tenaciously clinging to a national, Norwegian-language literature and arguing that it is vital that every people do so for the benefit of all other peoples.

A special exception could be made in the case of English, nevertheless, as a common tongue for all the peoples of the British Isles. (The same phenomenon, for example, has occurred in modern Italy, a land of many dialects and of long literary traditions in each, where, nevertheless, the Tuscan dialect of Dante Alighieri has, since national unification, become what the world knows as the Italian language, a situation of which Eliot would have been well aware, although he does not cite it.) His argument, in any case, regards the transmission of a culture, not the dynamics of its political and often military history. A culture, he insists, is “a peculiar way of thinking, feeling and behaving.” He continues: “[F]or its maintenance, there is no safeguard more reliable than a language. And to survive for this purpose it must continue to be a literary language— not necessarily a scientific language but certainly a poetic one. . . .” Regarded from that point of view, in fact, his comments on the maintenance of Norwegian as a literary language under Nazi rule are no less in keeping with his remarks here on the various peoples of the British Isles writing solely in English, although all individuals of Welsh, Irish, and Scottish extraction might not find themselves in agreement with his position.

Eliot himself would go as far as to defend and encourage such disagreements, for they too form a part of a culture. Whereas friction in the mechanical universe may be a waste of energy, in human cultures, all those frictions created by class and region, including those just discussed involving satellite cultures that have been reduced to secondary roles, “by dividing the inhabitants of a country into . . . different kinds of groups, lead to a conflict favourable to creativeness and progress.” As he puts it, paraphrasing the Whitehead epigraph for effect, “One needs the enemy.” Indeed, the disastrous transformation of Italian and German cultures by the ideological single-mindedness of fascism provides Eliot with a vivid and recent illustration of what can occur when dialogue and debate cease within a culture.

As the reader might have already observed, Eliot appears to be proposing a model of culture that involves ever-widening but concentric circles, from the village to the region to the nation to the world. The difficulty there, of course, is that once one transcends the idea of a national culture, one has to abandon most of the political associations that culture also implies. The United Nations had already been formed by the time of Eliot’s writing, and the visionary ideal of a world government had become a utopian commonplace ever since U.S. president Woodrow Wilson’s proposing a League of Nations following hard on the catastrophe of World War I in 1919.

Still, Eliot contends that if his pleading for the integrity of local cultures has any practical validity, then “a world culture which was simply a uniform culture would be no culture at all.” Eliot is forced to conclude that although we are “pressed to maintain the ideal of a world culture,” we are at the same time forced to admit “that it is something we cannot imagine. ” Indeed, the “colonization problem,” as he terms the imposition of one culture on another by force by an outside power, would only be exacerbated to an intolerable degree by any effort to impose a world culture, since cultures do not all follow the same processes of growth, a condition that such an imposition would require. Some areas of the world, Eliot notes in ending his remarks on unity and diversity as regional issues, citing as an example India, where a Hindu and Muslim culture existed side by side at the time, have seen the evolution of competing cultures to a degree that would make Eliot’s comments on British regionalism seem a mockery.

In his fourth chapter, as previously noted, Eliot takes up the topic of cultural unity and diversity as it is affected by cults and sects. Specifically, he defines his topic as “the cultural significance of religious divisions.” He begins by lamenting, in what he terms “more developed societies” such as one might find in Western Europe, the sort of cohesion between religious and nonreligious activities that one would expect to find in more primitive or less developed societies, keeping in mind that he is speaking of degrees of complexity and abstraction here, not quality and significance. As he puts it, the more conscious belief becomes, the more conscious unbelief becomes, leading to habits of indifference, doubt, and skepticism.

In The Idea of a Christian Society a decade earlier, Eliot had already addressed many of these same difficulties attendant on maintaining a meaningful national religious life in a postindustrial, highly materialistic, and contentious modern society. Now, however, he emphasizes that he wishes to explore those same issues not from the point of view of the Christian apologist but from that of the sociologist. As a result, “[m]ost of my generalisations are intended to have applicability to all religion, and not only Christianity.” If, then, he nevertheless appears to be discussing matters that are wholly Christian, it is because he is “particularly concerned with Christian culture, with the Western World, with Europe, and with England.” Finally, he emphasizes as well that whether one is a believer or an unbeliever, no one can be so completely detached from the religious experience as to approach and discuss it in a wholly objective manner.

That said, he continues by undertaking a consideration of “unity and diversity in religious belief and practice” in order to “enquire what is the situation most favourable to the preservation and improvement of culture.” Those religions that have the greatest universality, as he sees it, are most likely to “stimulate culture,” and their universality is determined in part by their being able to appeal to and be accepted by peoples of different cultures. Christianity certainly fills that bill; however, Eliot observes that there is always the danger that too broad a cross-cultural appeal can also result in the dilution of a religion’s core values.

These general premises established, Eliot announces that he will devote the remainder of this discussion to the relation of Catholicism and Protestantism in Europe, as well as to the diversity of sects that Protestantism has itself produced. It serves his purpose, for he finds himself compelled to admit that Europe since the 16th century, a convenient period reference for the Protestant Reformation, has certainly not suffered in terms of overall cultural development. While he must also admit that it is impossible to say what sort of cultural developments may have occurred instead had Europe remained Catholic and Christian, he cannot avoid the obvious conclusion that, based on the European experience, “[e]ither religious unity or religious division may coincide with cultural efflorescence or cultural decay.”

When he uses England itself as the focus for a similar discussion, however, he is less sanguine, for while the two dominant religious cultures in England are both Protestant—the Established Anglican Church and the various Protestant sects that have splintered from it during the centuries—the English atheist still shares in the religious life of culture when it comes to signficant social events such as births, marriages, and deaths. Nevertheless, Eliot sees the major Protestant cultures of Northern Europe, where the Protestant Reformation suffered its widest and most enduring successes, as having cut those regions off from the mainstream of European cultural development, which is largely Latin in origin. While he avoids evaluating the pros and cons of that separation for the cultures of the north, he returns again to its consequence for the English.

Since Anglicanism as an offshoot of Catholicism was the result of a decision made at the top, in this case by Henry VIII in his own dispute with Rome, whereas the Protestant dissenters were opposing themselves on native ground specifically against what they saw as little more than a national expression of Catholicism, England may be culturally more stratified religiously in ways that are themselves modified by cultural distinctions among classes. This Eliot is willing to attribute to the regional divisions based on ethnicities that he desribed in the preceding chapter. In the most basic terms, he is willing to concede that the British Isles’ having been home to many peoples makes it ripe for frequent dissension and stratification in all areas of culture, but especially religion.

The next logical step is to consider the ecumenical movements that are becoming more common. After making a distinction between intercommunion and reunion, he observes that complete reunion would entail a “community of culture.” The result would not, however, be that dreaded uniform culture worldwide, but rather a “Christian culture” manifested in its various local components. Here again, the danger would lie in such a Christianity’s attempting to be all things to all people, reducing “theology to such principles that a child can understand,” which he sees as a cultural debility. A worse danger, in keeping with the modern tendency to be polite to avoid the risk of appearing assertive, is that a sort of “cultural equality” may begin to prevail, and again the lowest-common-denominator approach to both theology and ritual might very well follow. When it comes to determining whether there should be an international church—Roman Catholicism—or a national church—here Anglicanism would provide a good example—or separated sects, Eliot takes the moderating position as he so often has done in this present treatise, proposing that the maintenance of a persistent tension among all three possibilities is desirable. “Christendom should be one,” but “within that unity there should be an endless conflict between ideas.”

Eliot devotes his last two chapters to culture and politics and culture and education. That he treats both topics in a far more cursory fashion than he had culture and class, culture and region, and culture and religion suggests that he does not view those last two categories as being as critical to the maintenance and transmission of cultural values. However, culture and religion, politics, and education together form a broader category, which is culture and the nation. Politics and education, from that point of view, are relatively equal to religion in forming the bedrock of a people’s culture as a nation, although the reader should recall at all times that, as far as Eliot is concerned, religion and culture are virtually inseparable.

No wonder, then, the short shrift that he gives to politics, which is in and of itself, though dominant in the short term, a transitory aspect of any culture’s ongoing health. Still, Eliot is enough a child of his time to recognize the importance that the culture itself, particularly in the postwar environment in which he is writing, attaches to the political sphere, so he treats it gingerly but with a profound respect for its genuine even if superficial importance. The political, for one thing, bandy the word culture about quite freely. Yet, while all may engage in the political process, by voting, for example, or paying taxes, few actually engage in politics, so that, in view of the considerable power that they wield, these few form a virtual elite unto themselves. It is that idea, if not practical reality, that Eliot hopes to short circuit somewhat as he now defines what he sees to be the place of the political in a culture.

“In a healthily stratified society,” he observes, “public affairs would be a responsibility not equally borne.” Nevertheless, the governing elite must not itself become one “sharply divided from the other elites of society.” To achieve this aim, he would not like to define the governing elite as opposed to the other elites as if the first were men of action as opposed to men of thought. Rather, he says, the relationship should be regarded as one “between men of different types of mind and different areas of thought and action.”

A society that is graded accordingly, Eliot contends, with “several levels of power and authority,” might find the politician “restrained” in his use of language by his fear of censure if not ridicule from “a smaller and more critical public,” composed of those other segments of the elite who are not directly involved with the governing elite. In other words, these “men of action,” the political, would not be isolated in their own dangerously and disproportionately powerful subculture but would instead be subject to the judgment of those who respect thought over action. This governing elite should, then, be required to study history and political theory, so that they are inculcated in the life of the mind.

Eliot has a pointed reason for bringing the political to the broader cultural table: “Today, we have become culture-conscious in a way which nourishes nazism, communism and nationalism all at once; in a way which emphasises separation without helping us to overcome it.” A more culturally astute governing elite would obviously go a long way toward overcoming those separations that are otherwise exposed to the exploitation of unscrupulous parties with agendas of their own.

Eliot cites present-day communist Russia as an example of a culture attempting to export their revolution to all kinds of disparate cultures throughout the world by presenting theirs as a culture condoning the equality of cultures at all cost—a successful strategy despite its patently obvious contradictions. The democratic West, meanwhile, does little better. Eliot cites the British Council, an official body created to promote “cultural exchanges,” to show how those tactics are little different, since it too makes the transmission and exchange of culture a function of the state apparatus.

Eliot rightfully wonders when it “again will be possible for intellectual elites of all countries to travel as private citizens.” As should be apparent, he imagines that that can occur only if there is a governing elite who do not imagine that the national culture and its dissemination and transmission is not the exclusive prerogative of the state. Eliot concludes chapter 5 on culture and politics by reiterating that we cannot “slip into the assumption that culture can be planned. Culture,” he says emphatically, “can never be wholly conscious.”

When Eliot, in chapter 6, takes up the topic of culture and education, the reader may recall that Eliot had, in chapter 2, argued that culture is better maintained and transmitted by the family than by those he calls educationists for the simple reason that the family unconsciously embodies the culture, while education, to be successful, must be a conscious process. And, as the reader is amply cautioned at the conclusion of chapter 5, culture can never—should never—be a “wholly conscious” affair. Rather than revisit that earlier argument in chapter 6, then, Eliot analyzes the general expectations associated with the idea of education by the culture, in order to extrapolate a more general idea of how education might best serve cultural purposes. To do so, he first sets out to examine and set in order the prevalent assumptions regarding education.

The first examination, involving the prevailing notions of the purpose of education, entails the most extensive summary on Eliot’s part, citing such contemporary authorities as H. C. Dent, Herbert Read, and C. E. M. Joad. In each instance, he convincingly demonstrates that to varying degrees education has come to be seen as an instrument for advancing social ideals. He remarks that it is therefore unfortunate if education as a means for individuals to acquire wisdom, knowledge, and a respect for learning is overlooked in the interest of serving broader social aims. If nevertheless it is finally agreed that education’s purpose is “making people happier,” then that assumption ought too to be examined. Eliot quickly concludes in this particular case that “education is a strain” that very often “can impose greater burdens upon a mind than that mind can bear.”

Eliot deals with his three other “assumptions” regarding the value and purpose of education in equally quick succession. (He could have as easily called them “myths” except that he has a poet’s respect for the meaning of words.) Thus, he is happy to debunk the notion that everyone wants an education. (“A high average of general education,” he observes, “is perhaps less necessary for a civil society than a respect for learning.”) He dismisses the notion that education makes for an “equality of opportunity” (he imagines instead that expanding educational opportunity can as likely lower educational standards) and the somewhat related notion that an exposure to education will unleash latent abilities that may otherwise lay dormant (the “Mute Inglorious Milton dogma” he calls it, invoking a central image from Thomas Gray’s sentimental masterpiece, “Elegy in a Country Churchyard”).

If there is a commonality to these assumptions that he raises only to challenge them, it is that they all emphasize the social benefits of education rather than promoting it for its own sake and as a force to help shape individual lives. The emphasis on opportunity and education, for example, he sees as indicative of the “depression of the family” and the “disintegration of class.” The reader should recall how integral Eliot sees the role of the family and class to be in the maintenance, dissemination, and transmission of culture.

Eliot goes as far as to assert that in the modern world education has become an abstraction, “remote from life” and implying a disintegrated society. Meanwhile, education is thought to be the panacea for “putting civilisation together again.” If by education in that regard, Eliot continues, we mean “everything that goes to form the good individual in a good society,” then he has no problem with that, revealing in the process his own definition of education. If, however, education means a standardized curriculum mandated by government bureaucracies, then “the remedy is manifestly and ludicrously inadequate.”

Ideally, education, he continues, defining the term as he goes, is the “process by which the community attempts to pass on to all its members its culture.” But when in practice education becomes what today would be called a government-sponsored and -directed entitlement, thereby bringing preselected aspects of the whole culture to bear in order to satisfy social and political agendas, the more systematically is the root culture betrayed. “Whether education can foster and improve culture or not, it can surely adulterate and degrade it,” Eliot concludes, imagining a future in which, the root culture lost to living human memory by the distortions of programmatic education, all that would be left of the culture would be “barbarian nomads . . . encamp[ed] in their mechanised caravans.”

Eliot closes by reminding his reader of what he clearly thinks is a cardinal point, perhaps the cardinal point of his entire presentation thus far: “. . . we cannot set about to create or improve culture, . . only will the means which are favourable to culture.” To do as much, returning to his purpose for composing the essay at hand, one must at least know what one means, what values of behavior, habits, and institutions one refers to, in invoking the term.

European Culture

In an appendix, which comprises the English-language transcriptions of three radio broadcast talks that Eliot originally made in German in 1946, he comments on the unity of European culture. Addressing a German-speaking audience in their own language within a year after they had suffered a deserved and total defeat in World War II, Eliot introduces himself as a poet and editor—a man of letters. He begins by commenting on the rich variety of languages that make up modern English, which he identifies as the best language for writing poetry, for that reason. It has extensive elements from German, Scandinavian through Danish, French through the Normans, not to mention the Celtic that has infiltrated the language through the Welsh, Irish, and Scottish peoples of the British Isles.