Home — Essay Samples — Life — Personality — Emily Dickinson Personality

Emily Dickinson Personality

- Categories: Personality Poetry Women's Rights

About this sample

Words: 415 |

Published: Mar 16, 2024

Words: 415 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Introspective nature, fierce independence and nonconformity.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life Literature Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 384 words

2 pages / 711 words

2 pages / 736 words

1 pages / 514 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Personality

Personality traits are the individual differences in characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving that distinguish one person from another. These traits have been the subject of extensive research in psychology and [...]

Cain, Susan. Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking. Crown Publishers, 2012.

I feel that people think I have a nice personality that can help influence others. I always try and act respectfully and consider others feelings. Person 1 said I still need to become more confident in how I word things, which I [...]

Writing an essay describing yourself is like gazing into a mirror, attempting to capture the complex facets that compose your identity. It is an introspective journey that transcends the surface, delving into the core of your [...]

Everyone has his or her own ideal person in one way or another. When most people talk about whom they admire most, it’s usually a person when they hold in false regard and most commonly someone in the public eyes. Without reason [...]

Frida Kahlo, the most famous female artist to date. Frida was a confident and brave woman, especially for her time. She didn’t let anyone tell her what she could and could not accomplish. Even through her personal troubles, she [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

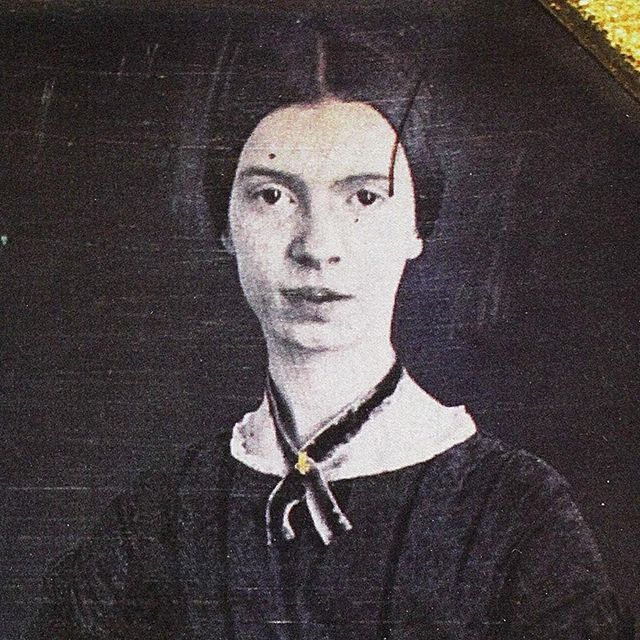

Emily Dickinson

(1830-1886)

Who Was Emily Dickinson?

Emily Dickinson left school as a teenager, eventually living a reclusive life on the family homestead. There, she secretly created bundles of poetry and wrote hundreds of letters. Due to a discovery by sister Lavinia, Dickinson's remarkable work was published after her death — on May 15, 1886, in Amherst — and she is now considered one of the towering figures of American literature.

Early Life and Education

Dickinson was born on December 10, 1830, in Amherst, Massachusetts. Her family had deep roots in New England. Her paternal grandfather, Samuel Dickinson, was well known as the founder of Amherst College. Her father worked at Amherst and served as a state legislator. He married Emily Norcross in 1828 and the couple had three children: William Austin, Emily and Lavinia Norcross.

An excellent student, Dickinson was educated at Amherst Academy (now Amherst College) for seven years and then attended Mount Holyoke Female Seminary for a year. Though the precise reasons for Dickinson's final departure from the academy in 1848 are unknown; theories offered say that her fragile emotional state may have played a role and/or that her father decided to pull her from the school. Dickinson ultimately never joined a particular church or denomination, steadfastly going against the religious norms of the time.

Family Dynamics and Writing

Among her peers, Dickinson's closest friend and adviser was a woman named Susan Gilbert, who may have been an amorous interest of Dickinson's as well. In 1856, Gilbert married Dickinson's brother, William. The Dickinson family lived on a large home known as the Homestead in Amherst. After their marriage, William and Susan settled in a property next to the Homestead known as the Evergreens. Emily and sister Lavinia served as chief caregivers for their ailing mother until she passed away in 1882. Neither Emily nor her sister ever married and lived together at the Homestead until their respective deaths.

Dickinson's seclusion during her later years has been the object of much speculation. Scholars have thought that she suffered from conditions such as agoraphobia, depression and/or anxiety, or may have been sequestered due to her responsibilities as guardian of her sick mother. Dickinson was also treated for a painful ailment of her eyes. After the mid-1860s, she rarely left the confines of the Homestead. It was also around this time, from the late 1850s to mid-'60s, that Dickinson was most productive as a poet, creating small bundles of verse known as fascicles without any awareness on the part of her family members.

In her spare time, Dickinson studied botany and produced a vast herbarium. She also maintained correspondence with a variety of contacts. One of her friendships, with Judge Otis Phillips Lord, seems to have developed into a romance before Lord's death in 1884.

Death and Discovery

Dickinson died of heart failure in Amherst, Massachusetts, on May 15, 1886, at the age of 55. She was laid to rest in her family plot at West Cemetery. The Homestead, where Dickinson was born, is now a museum .

Little of Dickinson's work was published at the time of her death, and the few works that were published were edited and altered to adhere to conventional standards of the time. Unfortunately, much of the power of Dickinson's unusual use of syntax and form was lost in the alteration. After her sister's death, Lavinia discovered hundreds of poems that Dickinson had crafted over the years. The first volume of these works was published in 1890. A full compilation, The Poems of Emily Dickinson , wasn't published until 1955, though previous iterations had been released.

Dickinson's stature as a writer soared from the first publication of her poems in their intended form. She is known for her poignant and compressed verse, which profoundly influenced the direction of 20th-century poetry. The strength of her literary voice, as well as her reclusive and eccentric life, contributes to the sense of Dickinson as an indelible American character who continues to be discussed today.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Emily Dickinson

- Birth Year: 1830

- Birth date: December 10, 1830

- Birth State: Massachusetts

- Birth City: Amherst

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Female

- Best Known For: Emily Dickinson was a reclusive American poet. Unrecognized in her own time, Dickinson is known posthumously for her innovative use of form and syntax.

- Fiction and Poetry

- Writing and Publishing

- Astrological Sign: Sagittarius

- Mount Holyoke Female Seminary

- Amherst Academy (now Amherst College)

- Interesting Facts

- In addition to writing poetry, Emily Dickinson studied botany. She compiled a vast herbarium that is now owned by Harvard University.

- Death Year: 1886

- Death date: May 15, 1886

- Death State: Massachusetts

- Death City: Amherst

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Emily Dickinson Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/emily-dickinson

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: May 7, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- 'Hope' is the thing with feathers - That perches in the soul - And sings the tunes without the words - And never stops - at all -

- Dwell in possibility.

- The Truth must dazzle gradually/Or every man be blind.

- Truth is so rare, it is delightful to tell it.

- If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way?

- Success is counted sweetest/By those who ne'er succeed./To comprehend a nectar/Requires sorest need.

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

14 Hispanic Women Who Have Made History

10 Famous Langston Hughes Poems

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

Amanda Gorman

Langston Hughes

7 Facts About Literary Icon Langston Hughes

Maya Angelou

How Did Edgar Allan Poe Die?

Why Edgar Allan Poe’s Death Remains a Mystery

Edgar Allan Poe

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Search more than 3,000 biographies of contemporary and classic poets.

Page submenu block

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

Emily Dickinson

Emily Dickinson was born on December 10, 1830, in Amherst, Massachusetts. She attended Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in South Hadley, but only for one year. Her father, Edward Dickinson, was actively involved in state and national politics, serving in Congress for one term. Her brother, Austin, who attended law school and became an attorney, lived next door with his wife, Susan Gilbert. Dickinson’s younger sister, Lavinia, also lived at home, and she and Austin were intellectual companions for Dickinson during her lifetime.

Dickinson’s poetry was heavily influenced by the Metaphysical poets of seventeenth-century England, as well as her reading of the Book of Revelation and her upbringing in a Puritan New England town, which encouraged a Calvinist, orthodox, and conservative approach to Christianity. She admired the poetry of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning , as well as John Keats . Though she was dissuaded from reading the verse of her contemporary Walt Whitman by rumors of its disgracefulness, the two poets are now connected by the distinguished place they hold as the founders of a uniquely American poetic voice. While Dickinson was extremely prolific and regularly enclosed poems in letters to friends, she was not publicly recognized during her lifetime. The first volume of her work was published posthumously in 1890 and the last in 1955. She died in Amherst in 1886.

Upon her death, Dickinson’s family discovered forty handbound volumes of nearly 1,800 poems, or “fascicles,” as they are sometimes called. Dickinson assembled these booklets by folding and sewing five or six sheets of stationery paper and copying what seem to be final versions of poems. The handwritten poems show a variety of dash-like marks of various sizes and directions (some are even vertical). The poems were initially unbound and published according to the aesthetics of her many early editors, who removed her annotations. The current standard version of her poems replaces her dashes with an en-dash, which is a closer typographical approximation to her intention. The original order of the poems was not restored until 1981, when Ralph W. Franklin used the physical evidence of the paper itself to restore her intended order, relying on smudge marks, needle punctures, and other clues to reassemble the packets. Since then, many critics have argued that there is a thematic unity in these small collections, rather than their order being simply chronological or convenient. The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson (Belknap Press, 1981) is the only volume that keeps the order intact.

Related Poets

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth, who rallied for "common speech" within poems and argued against the poetic biases of the period, wrote some of the most influential poetry in Western literature, including his most famous work, The Prelude , which is often considered to be the crowning achievement of English romanticism.

W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats, widely considered one of the greatest poets of the English language, received the 1923 Nobel Prize for Literature. His work was greatly influenced by the heritage and politics of Ireland.

Walt Whitman

Edgar Allan Poe

Born in 1809, Edgar Allan Poe had a profound impact on American and international literature as an editor, poet, and critic.

William Blake

William Blake was born in London on November 28, 1757, to James, a hosier, and Catherine Blake. Two of his six siblings died in infancy. From early childhood, Blake spoke of having visions—at four he saw God "put his head to the window"; around age nine, while walking through the countryside, he saw a tree filled with angels.

Newsletter Sign Up

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

The Oxford Handbook of Emily Dickinson

Karen Sánchez-Eppler is L. Stanton Williams 1941 Professor of American Studies and English at Amherst College and serves on the boards of the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Foundation and of the Emily Dickinson Museum. Her first book, Touching Liberty: Abolition, Feminism and the Politics of the Body (1993), included work on Dickinson. Dependent States: The Child’s Part in Nineteenth-Century American Culture (2005) initiated her turn to childhood studies. She is one of the founding coeditors of The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth and past president of C19: The Society of Nineteenth-Century Americanists.

Cristanne Miller is SUNY Distinguished Professor and Edward H. Butler Professor at the University at Buffalo SUNY. She has published broadly on nineteenth- and twentieth-century poetry. Her books on Dickinson include Emily Dickinson: A Poet’s Grammar (1987), Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century (2012), and the edition Emily Dickinson’s Poems: As She Preserved Them (2016), winner of the Modern Language Association’s Best Scholarly Edition Prize. She serves on the editorial advisory board for the Emily Dickinson Archive and is currently coediting a new complete letters of Emily Dickinson with Domhnall Mitchell. Among other work on modernist poetry, Miller is founder and director of the Marianne Moore Digital Archive .

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The Oxford Handbook of Emily Dickinson is designed to engage, inform, interest, and delight students and scholars of Emily Dickinson, of nineteenth-century US literature and cultural studies, of American poetry, and of the lyric. It also aims to establish potential agendas for future work in the field of Dickinson studies. This is the first essay collection on Dickinson to foreground the material and social culture of her time while opening new windows to interpretive possibility in ours. The collection strives to balance Dickinson’s own center of gravity in the material culture and historical context of nineteenth-century Amherst with the significance of important critical conversations of our present, thus understanding her poetry with the broadest “Latitude of Home”—as she puts it in her poem “Forever – is composed of Nows –”. Debates about the lyric, about Dickinson’s manuscripts and practices of composition, about the viability of translation across language, media, and culture, and about the politics of class, gender, place, and race circulate through this volume. These debates matter to our moment but also to our understanding of hers. Although rooted in the evolving history of Dickinson criticism, the essays in this handbook foreground truly new original research and a wide range of innovative critical methodologies, including artistic responses to her poetry by musicians, visual artists, and other poets. The suppleness and daring of Dickinson’s thought and uses of language remain open to new possibilities and meanings, even while they are grounded in contexts from over 150 years ago, and this collection seeks to express and celebrate the breadth of her accomplishments and relevance.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Major Characteristics of Dickinson’s Poetry

Using the poem below as an example, this section will introduce you to some of the major characteristics of Emily Dickinson’s poetry.

Sunrise in the Connecticut River Valley near Amherst.

I’ll tell you how the Sun rose – A Ribbon at a time – The steeples swam in Amethyst The news, like Squirrels, ran – The Hills untied their Bonnets – The Bobolinks – begun – Then I said softly to myself – “That must have been the Sun”! But how he set – I know not – There seemed a purple stile That little Yellow boys and girls Were climbing all the while – Till when they reached the other side – A Dominie in Gray – Put gently up the evening Bars – And led the flock away – (Fr204)

Theme and Tone

Form and style, meter and rhyme, punctuation and syntax.

Reading at Home: Emily...

Search form.

- Reading at Home: Emily Dickinson's Domestic Contexts

- Introduction by Gabrielle Dean

- “I am glad there are Books. They are better than Heaven”: Religious Texts in the Dickinson Family Libraries by Jane Wald

- Letters to the World: Popular Manuscript Circulation in the Nineteenth Century and Emily Dickinson’s Handwritten Verse by Thomas Lawrence Long

- “The Last Rose of Summer”: How Emily Dickinson Read and Rewrote the Favorite Song of the Nineteenth Century by Gabrielle Dean

- Contributors

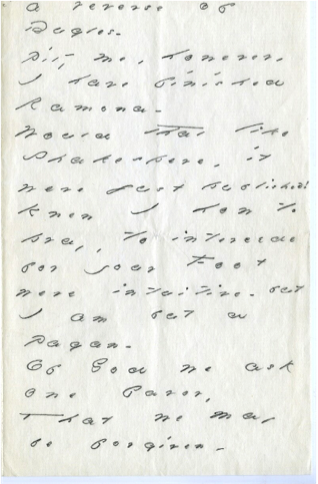

“They… address an eclipse”: Belief at Home

Emily Dickinson came of age in an orthodox household steeped in the Puritan theology that was gradually unraveling in the face of new varieties of Protestant experience. Like most Amherst families, the Dickinsons held daily religious observances in their home, but Emily was a less than enthusiastic participant: “They are religious, except me,” Dickinson wrote of her family, “and address an eclipse, every morning, whom they call their ‘Father’” (L 261, 2:404-05) (figs. 1-5).

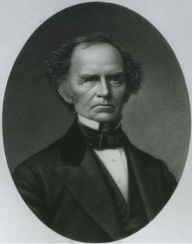

Figure 1. Edward Dickinson. Portrait, 1853, photographer unknown. Emily Dickinson Museum collection.

Figure 2. Emily Norcross Dickinson. Daguerreotype portrait, ca. 1847, by William C. North. Monson Free Library.

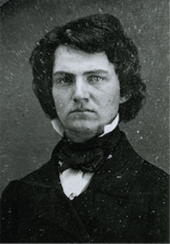

Figure 3. William Austin Dickinson, ca. 1850, photographer unknown. Amherst College Archives & Special Collections.

Figure 4. Emily Dickinson. Daguerreotype portrait, ca. 1847, photographer unknown. Amherst College Archives & Special Collections.

Figure 5. Lavinia Norcross Dickinson. Dagurreotype portrait, 1852, by J.L. Lovell. Dickinson family photographs, MS Am 1118.99b (27). Houghton Library, Harvard University.

In her teen years, a wave of religious revivals moved through New England and through Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, which she attended for a single year. One by one, her friends and family members made the public profession of belief in Christ that was necessary to become a full member of the church.

Although she agonized over her relationship to God, Dickinson ultimately did not join the church: “I feel that the world holds a predominant place in my affections. I do not feel that I could give up all for Christ, were I called to die” (L 13, 1:36-38). By the time she reached her thirties, Emily Dickinson had stopped attending services altogether, a decision that coincided with her most productive writing years, the national tragedy of Civil War, the threat of losing her vision, a telling emotional crisis of an unknown nature, and increasing reclusiveness.

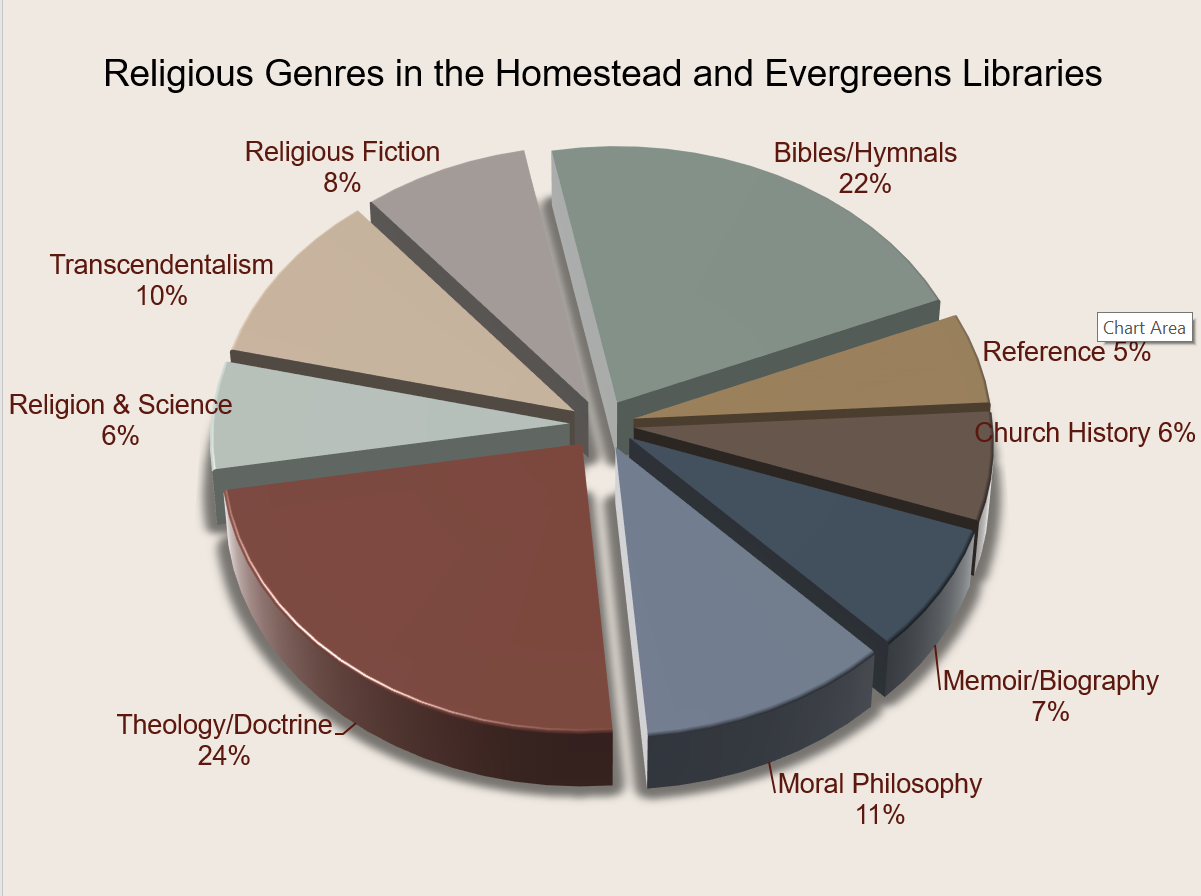

A persistent misconception about Dickinson’s refusal to become a full member of the church and to style herself a “pagan” is that she rejected God altogether, cloistered herself in her room, took little notice of the world beyond her four walls, and composed poem after poem for no one but herself. On the contrary—and despite her absence from public religious life—Dickinson’s letters and poems chronicle a lifelong struggle with issues of faith and doubt, suffering and salvation, nature and deity, mortality and immortality. An examination of the religious texts on the shelves of her family’s libraries could cast more light on Emily Dickinson’s personal theological explorations. My aim here is to begin this important task. First, I will sketch in broad strokes the contents of the libraries at the family Homestead, where Emily Dickinson lived most of her life, and at The Evergreens, her brother’s house next door. Next, I will offer a profile of religious texts associated with various family members, which provides insight not only into their personal interests but also into the broader contours of nineteenth-century American religious movements. Finally, I will examine two books in particular that suggest broad interaction with contemporary theology in the Dickinson households.

“This then is a book!”: Literary Context And Household Libraries

Emily Dickinson’s patterns as a reader naturally have important implications for her choices as a writer. The problem of how to place a reclusive poet in meaningful context has plagued scholars and readers ever since Dickinson’s first anonymous publications. Over the past several decades, however, a scholarly focus on more thorough accounts of Dickinson’s context—social, literary, political, material—has offered some hope of filling in Dickinson’s elusive “omitted center.” Beginning with Jack Capps’ 1966 survey, Emily Dickinson’s Reading , scholars have combed the texts Emily Dickinson consumed for direct and indirect literary influences on her poetic art. Others have extended this effort by describing as accurately as possible the cultural milieux of Dickinson’s opus to better understand the magnitude of her achievement. Simultaneously, others have probed Dickinson’s self-conscious connections to women’s literature, the American Civil War, religion, contemporary understandings of science and the natural world, and more. Emily Dickinson as a reader and the books she had at hand have recently attracted increased attention. [2]

To be sure, the Dickinson family’s libraries offer an exceptional view of Dickinson’s personal literary context, for they contained the books she lived with every day. The libraries’ physical dispersal in the twentieth century, however, has made it challenging for researchers to study the original collections and assess their import.

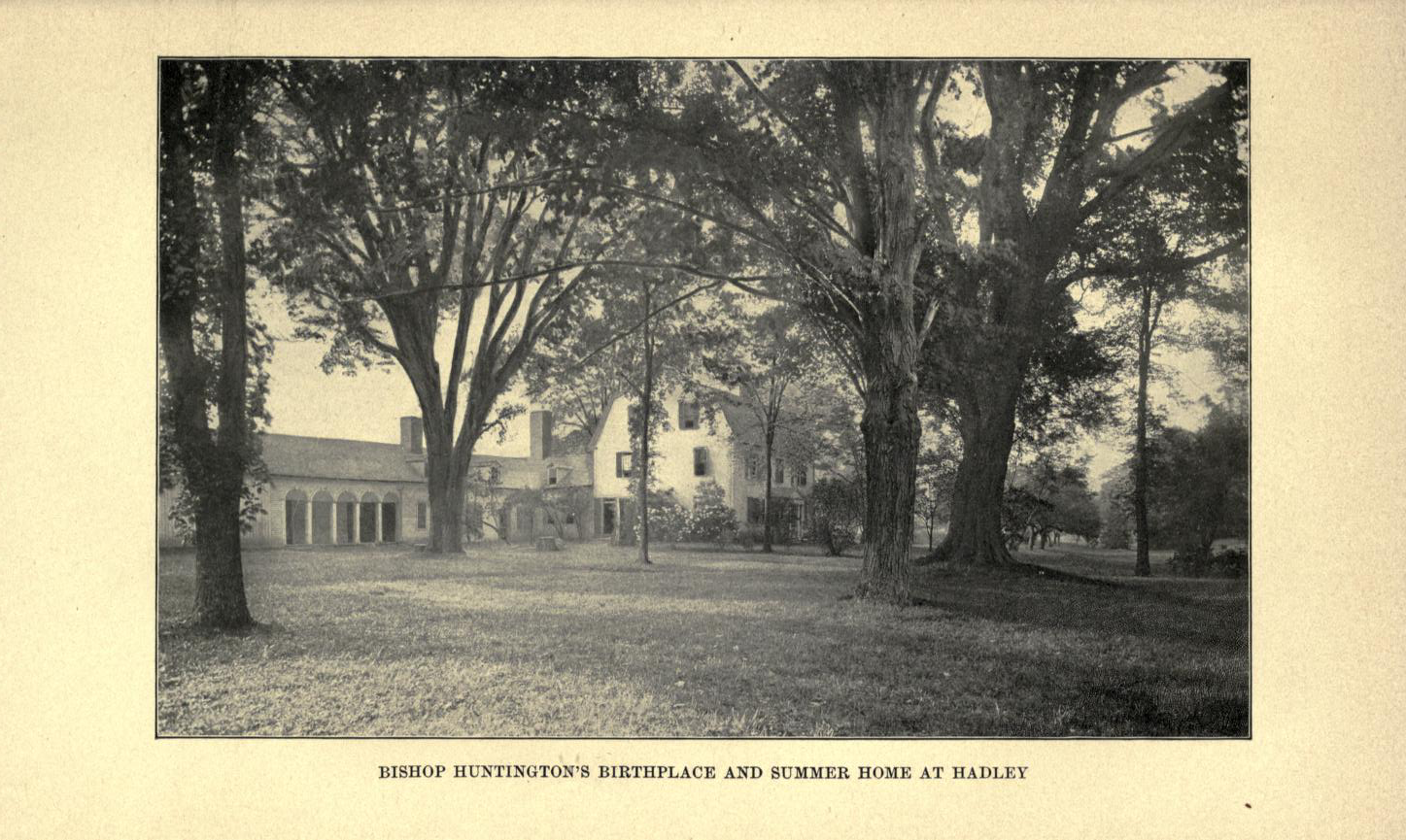

Figure 6. The Homestead. Photograph by Michael Medeiros. Emily Dickinson Museum collection.

Figure 7. The Evergreens. Photograph by Michael Medeiros. Emily Dickinson Museum collection.

Dickinson was born, wrote poetry, and died in the family homestead built in 1813 by her attorney grandfather (fig. 6). In 1855, after an absence of fifteen years, the Dickinson family settled back into the Homestead while construction of a new home for Austin and his bride-to-be Susan began on the adjacent lot. Their daughter, Martha Dickinson Bianchi (by 1914 the last surviving family member), sold the Homestead in 1916 but continued to live at The Evergreens until her own death in 1943 (fig. 7). Martha moved her aunt’s manuscripts, family furnishings, keepsakes, and books from the Homestead to The Evergreens, assembling a memorial collection in what she called the “Emily Room” (figs. 8-10).

Figure 8. Martha Gilbert Dickinson Bianchi, ca. 1900. Photographer unknown. Emily Dickinson Museum collection.

Figures 9 and 10. Emily Dickinson’s furniture in the “Emily Room” at The Evergreens, 1934. Photographer unknown. Emily Dickinson Museum collection.

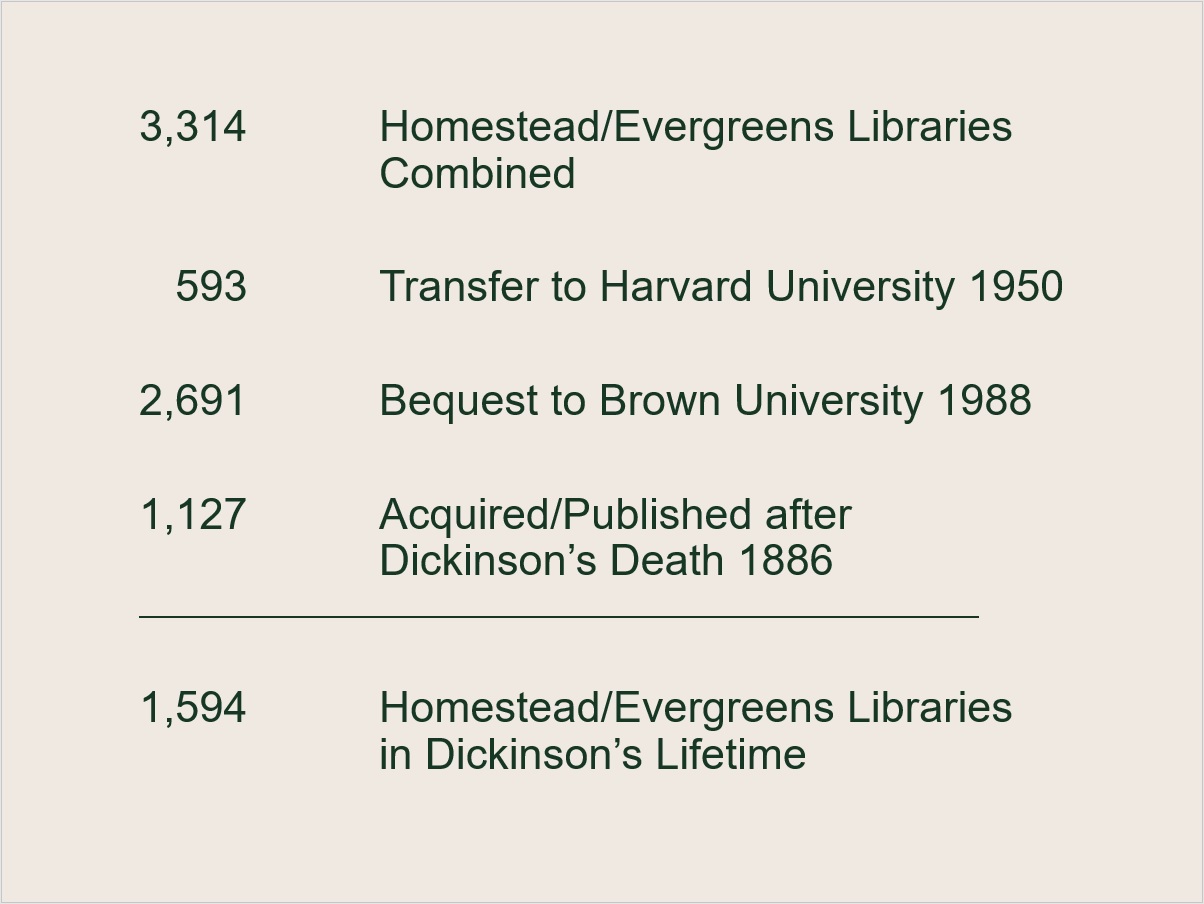

Wishing to secure Dickinson’s literary legacy, Martha’s heirs, Alfred and Mary Hampson, agreed in 1950 to transfer Emily’s manuscripts and personal effects, selected family furnishings, and approximately six hundred volumes—personal copies belonging to Emily Dickinson or titles of significance to her but owned by other members of the family—to Harvard University’s Houghton Library. Upon her death in 1988, Mary Hampson established the Martha Dickinson Bianchi Trust to care for The Evergreens and its contents, and left remaining Dickinson family papers and some 2,700 additional volumes to Brown University where they now reside in the John Hay Library (fig. 11).

Figure 11. Count and distribution of books from the Dickinson family libraries.

Emily Dickinson’s manuscripts are increasingly available to scholars and the public. The Dickinson Electronic Archive has made numerous resources available since 1994. Harvard University’s Houghton Library is systematically digitizing its six-hundred-volume collection of Dickinson family books ( www.oasis.lib.harvard.edu/oasis/deliver/~hou00321 ) as well as its collection of Dickinson letters and manuscripts. Amherst College has digitized its entire Dickinson manuscript collection ( www.acdc.amherst.edu/collection/ed ). The collaborative online Emily Dickinson Archive ( www.edickinson.org ), led by Harvard University Press, now furnishes images of all poem manuscripts in the collection edited by Ralph Franklin in 1998. These projects offer opportunities for many new robust research projects, including closer examination of a subset of Dickinson family book holdings that influenced Emily Dickinson’s poetics and theology—religious texts in the two family libraries (figs. 12-13). [3]

Figure 12. Library at the Dickinson Homestead. Photograph by Michael Medeiros. Emily Dickinson Museum collection.

Figure 13. Library at The Evergreens. Photograph by Michael Medeiros. Emily Dickinson Museum collection.

A preliminary analysis of the combined Brown and Harvard inventories reveals that, at the time of Emily Dickinson’s death in 1886, the two family libraries contained close to 1,600 volumes. Yet, the formation, use, and contents of these libraries have received little attention, due in part to the prominence of the Houghton collection of six hundred hand-picked books and the relative inaccessibility of the majority of family books at Brown University. [4]

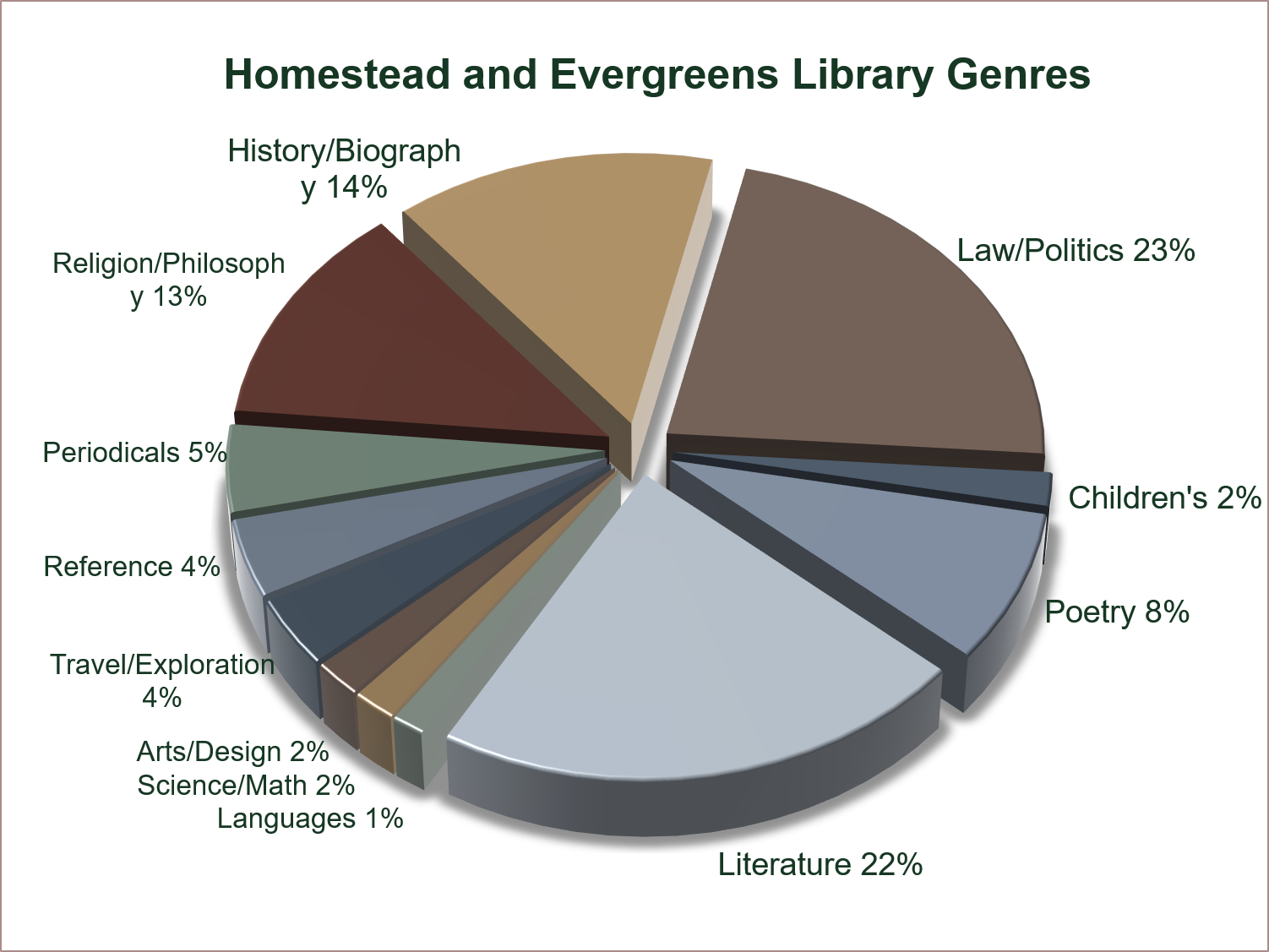

Not surprisingly, the leading genre on the shelves was literature—fiction, poetry, and children’s stories comprised a third of all books. Almost a quarter of library holdings were books related to law, government, and politics. There were a couple of hundred books on religion, theology, and natural philosophy. History and biography accounted for a similar proportion. Family subscriptions to periodicals—including the Atlantic Monthly , Scribner’s Monthly , and Harper’s —claimed five percent of library shelf space. A lesser smattering of instruction books in languages, science, and mathematics sat alongside a clutch of art and reference books and exploration narratives (fig. 14).

Figure 14. Genres in the Dickinson family libraries in 1886.

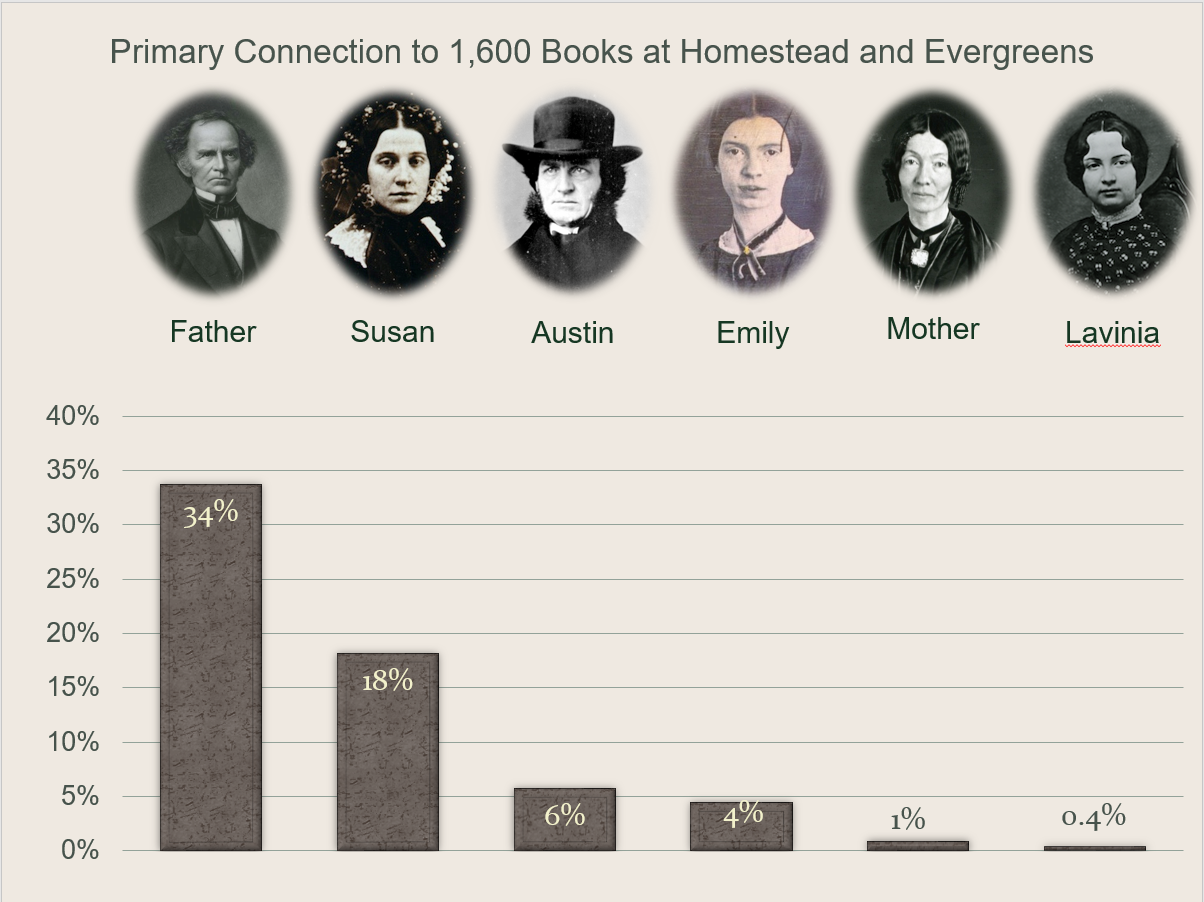

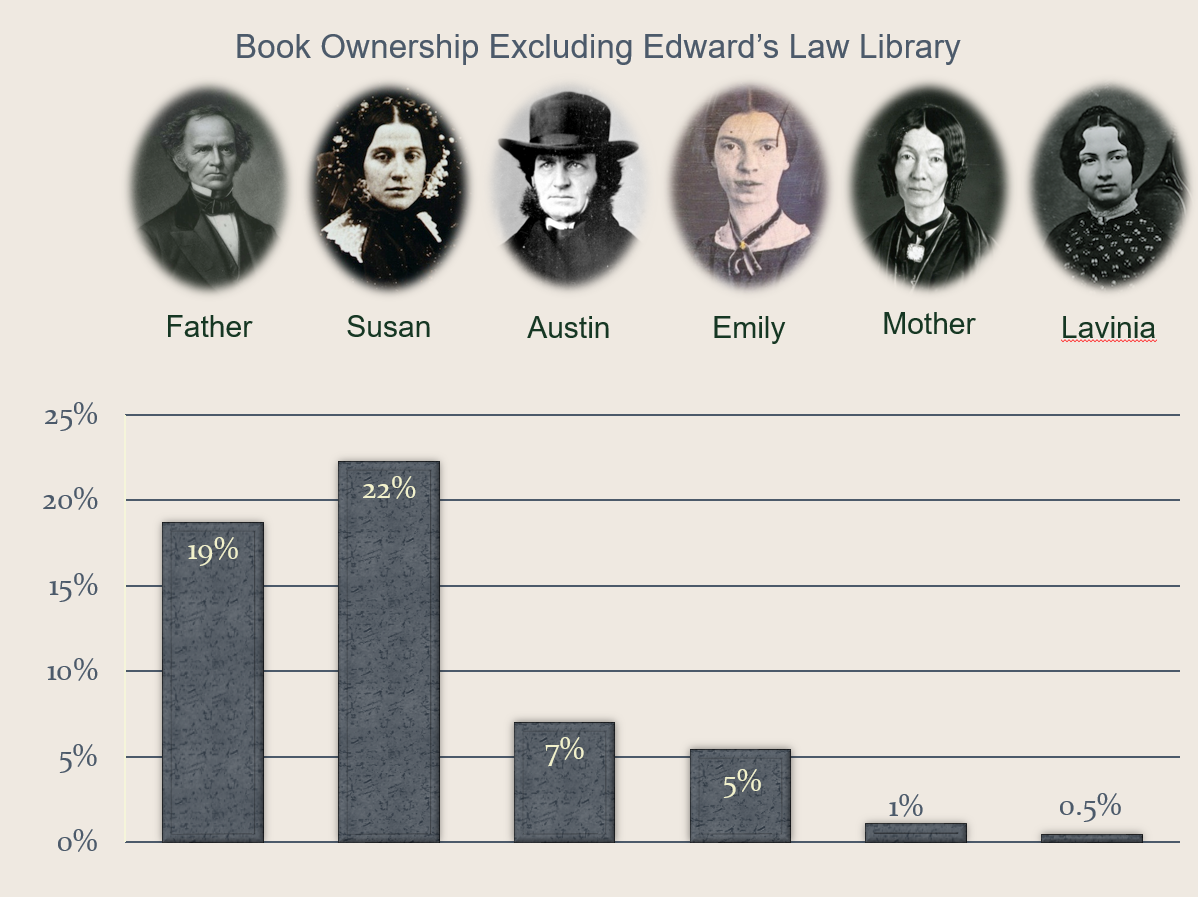

Despite the fact that the family libraries were compiled and used by four generations of Dickinsons, it is possible to postulate—by analyzing inscriptions, correspondence, dates of publication, and genre—which member of the family purchased, owned, or was most closely associated with each of 1,400 volumes, or about 90% of the collection (fig. 15).

Figure 15. Primary connection of 1600 titles to Dickinson family members.

The prize for book acquisition in the Dickinson family goes to Edward Dickinson, who, according to his daughter “only reads on Sunday—he reads lonely & rigorous books” (L342a, 2:472-74). A lawyer, legislator, and Amherst College treasurer, Edward Dickinson built a professional library of legal, political, and economic works: at least 230 volumes of Congressional debates and proceedings, diplomatic correspondence, executive documents of the U.S. House of Representatives, reports on trade and agriculture, and the like. Another 300 books were heavily weighted toward history, exploration narratives, orthodox religious texts, and literary classics. In total, no fewer than 540 books from the family library can be linked with Edward Dickinson.

Emily’s confidante and sister-in-law, Susan Gilbert Huntington Dickinson, was known for her intelligence and cultured interests. Her personal book holdings rivaled those of her father-in-law Edward, omitting his Congressional records (fig. 16).

Figure 16. Primary connection of titles to Dickinson family members, excluding Edward Dickinson’s law library.

Upon her engagement to Austin Dickinson, Sue’s brother Frank promised a wedding present of fifty books of her choice, many of which can be identified from her application of an elegant bookplate inside the cover with the inscription of the date of acquisition in her hand (fig. 17). Under Sue’s direction, The Evergreens filled with literary classics and contemporary fiction, poetry, art, and eclectic theological and philosophical treatises. “Austin’s taste,” as described by his daughter Martha, “was strongly individual and often diverged until the absorption of his legal professional work . . . left him little leisure for even the books he cared for most.” Martha indicated that “many were given him by Sue” (Bianchi, [Family Books]). As an attorney and Amherst College treasurer like his father, Austin amassed a prodigious professional library housed in his Palmer Block offices, which was lost to fire in 1888, along with numerous documents important to Amherst town history.

Figure 17. Susan Huntington Gilbert’s bookplate. Emily Dickinson Museum collection.

Despite her feeling that books are “the strongest friends of the soul,” Emily Dickinson seems to have had an ambiguous relationship to book ownership (Sewall, Life , 76). Only about 5% of the titles in the family libraries can be distinguished specifically as her personal property. But, obviously, she had access to the full family libraries as well as to holdings of Amherst College’s library. She traded books with friends, belonged to reading clubs, and even indulged in hiding contraband books from her parents. Niece Martha Dickinson Bianchi observed that Austin, Sue, and Emily shared and “read the same books with apparent delight,” and that few [of Emily’s own books] were written in—gifts or especial favorites only being claimed as personal” (Bianchi, [Family Books]). More important to Emily Dickinson than the book as object or personal possession was the text .

The “household of faith”: Varieties of Religious Experience in the Dickinson Households

Before looking at a few of the religious texts in the family libraries, some observations about the spiritual views of the Dickinson siblings and their sister-in-law may be helpful. Austin, Emily, and Lavinia—each in his or her own way—merged the rationalism of their parents’ generation with Calvinist insistence on the depravity of human nature into a romantic and sentimental confidence in the perfectibility of humankind. In Amherst at mid-century, close upon the heels of a general religious revival, it may have been difficult, but not impossible, for members of one of the town’s most influential and orthodox families to buck the religious status quo. Clearly, the Dickinson siblings (and perhaps even their father) tested the boundaries of religious orthodoxy and found their theological voyages less than smooth sailing.

Martha Dickinson Bianchi reported that in young adulthood “both Emily and Austin seem to have inwardly departed from a theology that would now hold Fundamentalism to be heresy” (Bianchi, Face to Face , 133-34). Austin, like Emily, expressed grave doubts about the church’s insistence that only those who confessed faith in Christ were to be saved from sin and inherit eternal life. He stated these misgivings in a long letter to Susan’s sister Martha in 1852:

I see them [mankind] marshaled in mighty hosts, yet under different banners, and marching on to the word of their several leaders, whom they believe, each his own, have received from the Omnipotent himself the true and only true chart of the route to knowledge, to happiness everlasting &to him. And now new doubts encompass me, for if either , and only one , which is right ? . . . I ask myself, Is it possible that God, all powerful, all wise, all benevolent, as I must believe him, could have created all these millions upon millions of human souls, only to destroy them? That he could have revealed himself & his ways to a chosen few, and left the rest to grovel on in utter darkness? I cannot believe it. I can only bow & pray, Teach me, O God, what thou wilt have me do, & obedience shall be my highest pleasure (A. Dickinson, qtd. in Sewall, Life , 106).

Austin’s views about spiritual matters were suspiciously progressive. In a draft of his 1856 confessional statement, Austin acknowledged that he had once—but no longer—considered religion “‘a delusion, the bible a fable, life an enigma’” (qtd. in Habegger, Wars , 336). Elsewhere, he expressed admiration for the noble character of the converted but admitted his “‘great difficulty has been in getting a sense of my sinfulness’” (qtd. in Habegger, Wars , 243). He managed to overcome his resistance to orthodox expectations just enough to join the church as Susan urged. By 1870 his dearest friend, Rev. Jonathan Jenkins, minister of First Church, described Austin as “‘not an atheist or freethinker . . . but only about fifty years in advance of his generation’s views’” (qtd. in Bianchi, Face to Face , 133).

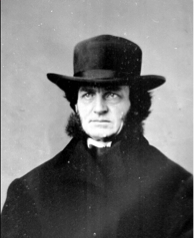

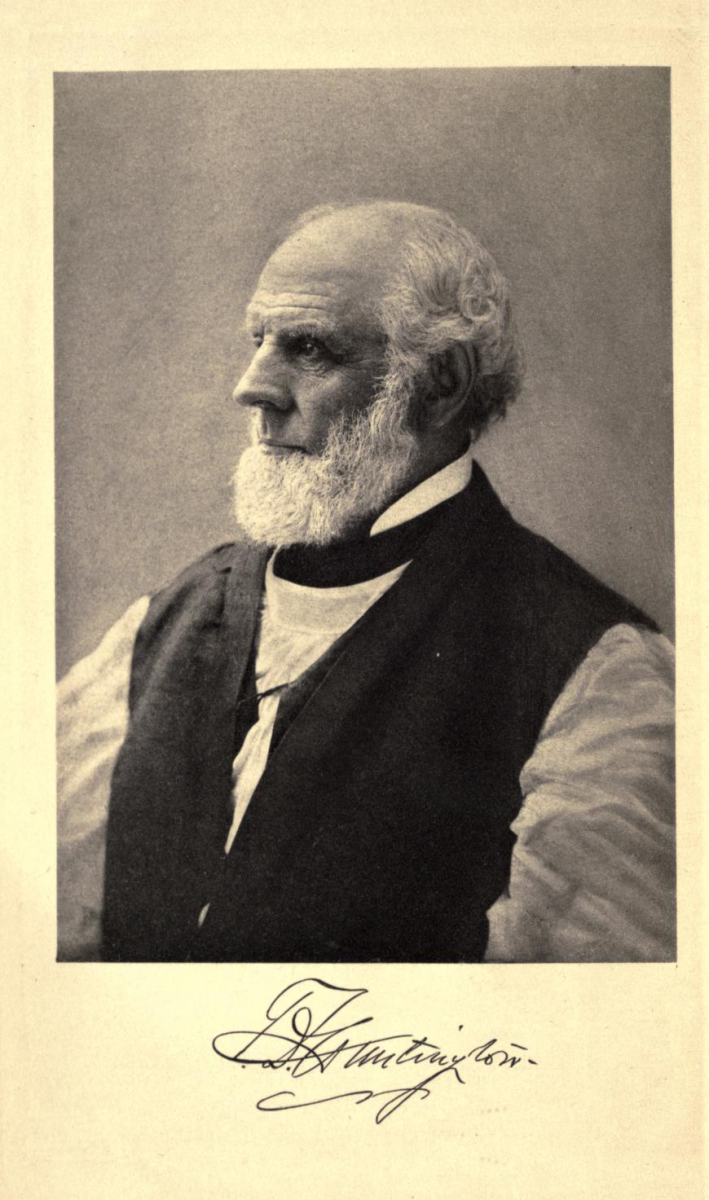

Figure 18. Austin Dickinson. Photographic portrait, ca. 1869, by Richard Hurley. Special Collections, Brown University Library.

Martha Dickinson Bianchi recalled that neither of her parents wanted their children to experience the oppression of “the more Puritan Sunday of their own youth” (Bianchi, “Life Before Last,” 27). When a conscientious young Sunday School teacher offered too lurid a description of the “lake of burning brimstone awaiting us all,” Austin’s prompt response was to “wipe out hell and Sunday-school with one burst of indignation” (Bianchi, “Life Before Last,” 26). His patience with Congregational theology ran out after Jenkins left Amherst in 1877 to accept a call in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Austin “brought home all our hymn books and wouldn’t go to church anymore” (Bianchi, “Life Before Last,” 92). Jenkins’ departure provoked a controversy between Austin and the church elders about “the delinquencies of his individual interpretation of belief.” The deacon delegated to remonstrate with Austin met only with an amused brush-off: “Excommunicate away, Deacon! That’s all right. Bear you no ill-will. I’ll bid you good morning!” (Bianchi, Face to Face , 134). Ten years later, Austin began a long affair with Mabel Loomis Todd, which put the two squarely at odds with the moral teachings of the church, but both remained active parishioners. Austin contributed liberally to the church treasury, remained a pillar of the Parish Committee, and oversaw construction of the new meetinghouse directly across the street from The Evergreens. Church leaders turned to Austin for an address on “Representative Men of the Parish, Church Buildings and Finances” to celebrate the church’s 150 th anniversary (fig. 19). Austin’s community stature—and his pocketbook—encouraged clergy and parishioners alike to overlook his heterodox religious opinions.

Figure 19. Title page, A Historical Review. One Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary. First Church of Christ. Amherst, Massachusetts. November 7, 1889. Amherst: Press of the Amherst Record, 1890. New York Public Library via Internet Archive.

Figure 20. First Church of Christ (Congregational), built 1867. From A Historical Review. One Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary. First Church of Christ. Amherst, Massachusetts. November 7, 1889. Amherst: Press of the Amherst Record, 1890. New York Public Library via Internet Archive.

Although less is known about Lavinia’s religious views, it appears that she did not struggle as vigorously to find a personally satisfactory theology as did her brother and sister. She responded readily to the 1850 revivals by exhorting her brother and sister to become Christians early in the year and by joining the church herself in November. [5] Lavinia was subsequently an active participant in church activities and among intimates always prepared to render an opinion—and use her gift for mimicry—on the sermon, services, or fellow parishioners. An obituary in the Springfield Republican noted that Lavinia was “very reticent” about her own religious experiences and sympathies.

She often questioned the dealings of Providence, and sometimes seemed defiant in the presence of some cruel bereavement. But for all this, I do not believe that her faith in an all-wise, benevolent Being ever suffered more than momentary eclipse. She was not given to analyzing her spiritual condition. She seemed less conscious of her duties toward her Creator than toward the creatures of his hand. [6]

Martha Dickinson Bianchi remembered her aunt Lavinia as a realist with a thoroughgoing “dread of cant and all conventional religious conversation” (Bianchi, “Life Before Last,” 291). She “wasted little time” upon spiritual matters except—in keeping with a general family characteristic—as it was reflected through Nature (Bianchi, “Life Before Last,” 290).

A vast but still inconclusive literature attempts to explain Emily Dickinson’s religious and spiritual platform. [7] It is not within the scope of this essay to distill that literature or to draw new interpretations, but rather to remind us that our interest in the family libraries serves the purpose of developing a more informed context for Dickinson’s spiritual explorations. Because she experienced profound and conscientious religious doubts as a teenager, went through an existential crisis of unknown origin as a young adult, exercised detailed knowledge of the Bible, encountered a ferment of contemporary religious thought, withdrew from her ecclesiastical tradition, and expressed her relationship to spiritual matters in poetic form even as that relationship changed, it has been difficult for scholars and readers to stabilize that religious platform.

In her elegant obituary of Emily, even Susan Dickinson had difficulty defining (or, perhaps, protecting) her friend’s religious mind, but she linked it implicitly with a bare-bones library.

Keen and eclectic in her literary tastes, she sifted libraries to Shakespeare and Browning —quick as lightning in her intuitions, and analyses, she seized the kernel instantly, almost impatient of the fewest words by which she must make her revelation. To her life was rich, and all aglow with God and immortality. With no creed, no formulated faith, hardly knowing the names of dogmas she walked this life with the gentleness and reverence of old saints, with the firm step of martyrs who sing while they suffer. (S. Dickinson, 268)

The absence of a straightforward statement of her beliefs makes it all the more difficult to square the circle—or circumference—of Dickinson’s spiritual journey and identity. As was her habit, Dickinson framed this process of spiritual formation in poetic form:

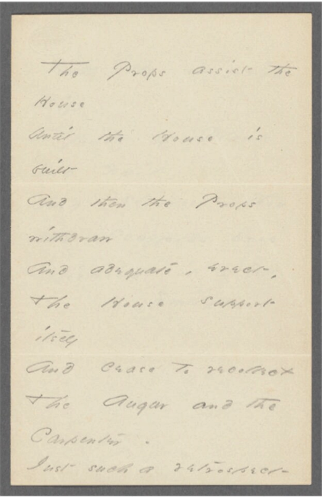

The Props assist the House Until the House is built And then the Props withdraw And adequate, erect, The House support itself And cease to recollect The Augur and the Carpenter – Just such a retrospect Hath the perfected Life – A Past of Plank and Nail And slowness – then the scaffolds drop Affirming it a Soul – (Fr729b)

Figure 21. Emily Dickinson, “The Props assist the house” ( Fr729b ). Poems: Loose sheets. The Props assist the House. MS Am 1118.3 (347). Houghton Library, Harvard University. From the Emily Dickinson Archive .

In perfect metaphor, Dickinson portrays the individual being as a “House” whose construction is ultimately completed or “perfected,” through Jesus Christ “the Carpenter,” as a fully endowed and unimpeded “Soul.” Even in such straightforward poetic form, Dickinson conveys a far more complex theology than some of her more familiar poems imply:

Some keep the Sabbath going to Church – I keep it, staying at Home – With a Bobolink for a Chorister – And an Orchard, for a Dome – (Fr236)

With its brisk, lighthearted mood and plain references to the natural world that are immediately recognizable to the reader, this poem has become one of Dickinson’s most memorable verses. Its flippant tone concerning mainstream religious observance, however, has reinforced popular perceptions of Dickinson’s attention to religion as less that serious. In these two examples, it is clear that Dickinson’s tone and sense of gravity concerning religious experience varies tremendously. Some poems embrace the need for faith:

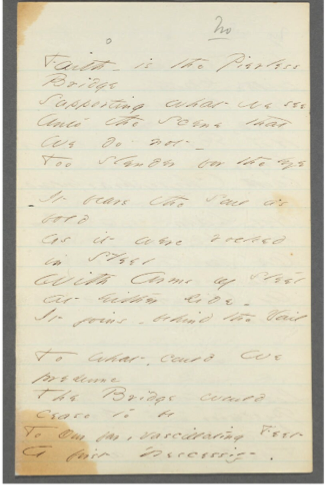

Faith - is the Pierless Bridge Supporting what We see Unto the Scene that We do not - Too slender for the eye (Fr978)

Figure 22. Emily Dickinson, “Faith - is the Pierless Bridge” ( Fr978a ). Poems: Packet XXXIII (mixed sets). Includes 26 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862-1864. Houghton Library, Harvard University. From the Emily Dickinson Archive .

Others are plainly and comically irreverent:

The Bible is an antique Volume - Written by faded Men At the suggestion of Holy Spectres – (Fr1577)

Sometimes Dickinson rails at God’s distance:

Of Course - I prayed - And did God Care? He cared as much as on the Air A Bird - had stamped her foot - And cried “Give Me” - (Fr581)

Even more startling than her anger is Dickinson’s disgust at the notion that humankind’s capacity for faith is a prop for a powerless God.

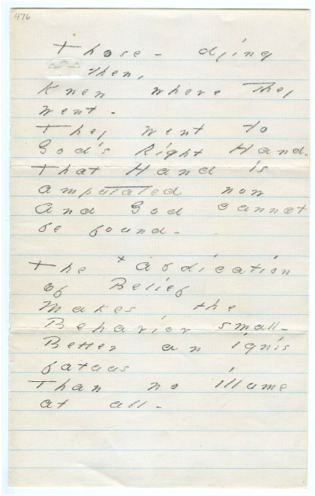

Those - dying then, Knew where they went - They went to God’s Right Hand - That Hand is amputated now And God cannot be found - (Fr1581)

Figure 23. Emily Dickinson, “Those - dying then” (Fr1581). * Amherst Manuscript #476. Amherst College. From the Emily Dickinson Archive. *

A substantial bibliography traces Emily Dickinson’s wary stance toward orthodox religious beliefs and practices during her lifetime. The few poems noted above illustrate the myriad ways in which Emily Dickinson resisted and grappled with conventional religious culture in the second half of the nineteenth century and in the second half of her life. She cultivated a close familiarity with biblical texts and regularly deployed those texts in poetry and correspondence, sometimes accepting their import at face value, at other times insinuating new meanings. At her most extravagant, Dickinson pushed her use of the scriptures over the normative edge, perhaps abetted by the contents of the books on the shelves of the family libraries.

A principal recipient and interpreter of Dickinson’s biblical allusions in poems and letters was her sister-in-law Susan Gilbert Dickinson. The two handed back and forth texts by religious philosophers and exchanged views about spiritual concerns. Susan joined the congregational First Church in Amherst on the very same day as her future father-in-law Edward Dickinson and, as we have seen, considered commitment to Christ a sine qua non for her marriage to Austin. Yet, Susan introduced at least a few un conventional elements—from the trivial to the momentous—into the Dickinson family. As a newlywed, for example, she raised the neighbors’ eyebrows as well as suspicions of Romanism when she brought the New York Knickerbocker tradition of hanging Christmas wreaths at the windows of The Evergreens. [8]

More significantly, Susan became known for evenings of cultural and intellectual interchange at The Evergreens where statesmen and legislators, ministers, philosophers, and scientists discussed contemporary topics of all kinds, including religion. Amherst College professor Elihu Root used the occasion of a supper party at The Evergreens to introduce “the daring theory of Evolution,” aided by Professor Benjamin Kendall Emerson, proudly declaring himself a “Theistic Evolutionist,” and Maria Whitney, “all but excommunicated from the Jonathan Edwards church in Northampton for her scientific free-thinking acquired in Germany” (Bianchi, “Life Before Last,” 103). Susan was also active during the 1880s in working with poor children and families in Logtown, east of Amherst, providing food, clothes, literacy instruction, and Sunday School lessons. Her work with clergy and families at Dwight Chapel grew out of the beginnings of a social gospel movement championed by leaders such as Horace Bushnell, Henry Ward Beecher, and Frederic Dan Huntington, men who visited The Evergreens and whose works appeared on the Dickinson library shelves.

Some Dickinson biographers have taken a jaundiced view of Susan Dickinson’s religious beliefs, observing, with implications of hypocrisy, that she was “never famous for her piety” (Sewall, Life , 100), that she “sporadically insisted on certain orthodox prohibitions” (Habegger, Wars , 266), or that her charitable work carried the trappings of “missionary zeal” (Habegger, Wars , 619). Perhaps the documented tensions between Austin and Susan over his conversion, or disproportionate reliance on Mabel Loomis Todd’s writings for biographical information about Susan, have allowed this skepticism to go relatively unchecked. A more in-depth biography of Susan Dickinson may offer a less idiosyncratic understanding of her personality and beliefs. [9]

“ Those — dying then, / Knew where they went — ”: Annihilation and Its Discontents

While Emily documented her spiritual struggle in poetic form, Susan Dickinson documented hers in her library. Of the roughly 200 religious texts on the shelves at the Homestead and Evergreens, easily a third can be linked to Susan, and about a quarter can be linked to Edward Dickinson (fig. 23).

Figure 24. Primary connection of religious titles in the family libraries to Dickinson family members.

Given Emily Dickinson’s engagement with spiritual themes in her poetry and letters, it is surprising that only a handful of these books can be specifically identified by inscription with her: a couple of Bibles, a school textbook on ecclesiastical history, Emerson’s transcendentalist essays, and a few others. When Emily claimed “my father buys me many books, but begs me not to read them,” she probably was not referring to religious texts (L 261, 2:404-05). Inventories show that Edward gave his poet daughter just four titles in this genre. He presented to her at age thirteen, as he did to each of his three children, the King James version of the Bible (figs. 25-26). It was the text to which Dickinson turned again and again in prose and poetry for references to biblical persons, stories, epigrams, and texts.

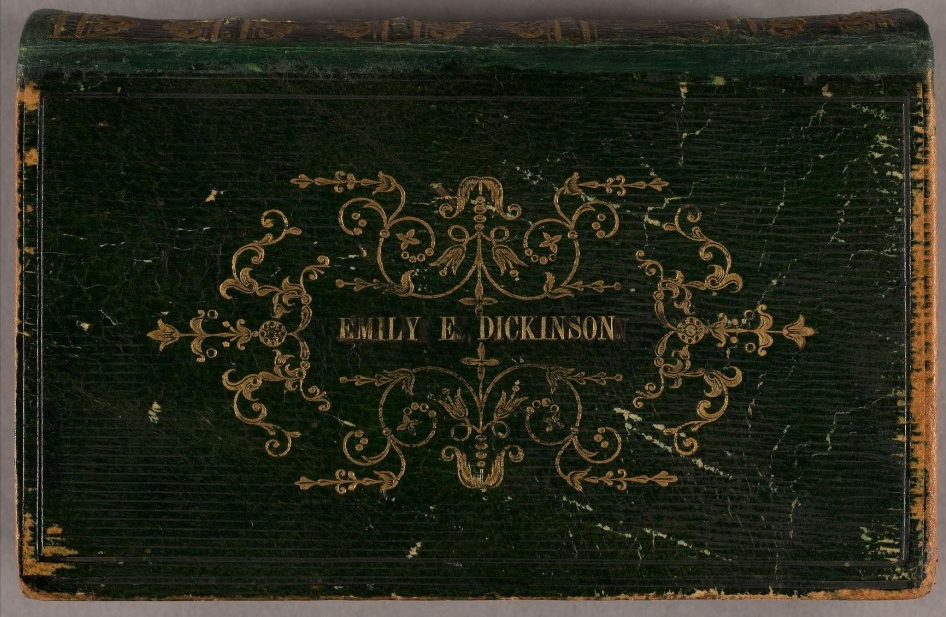

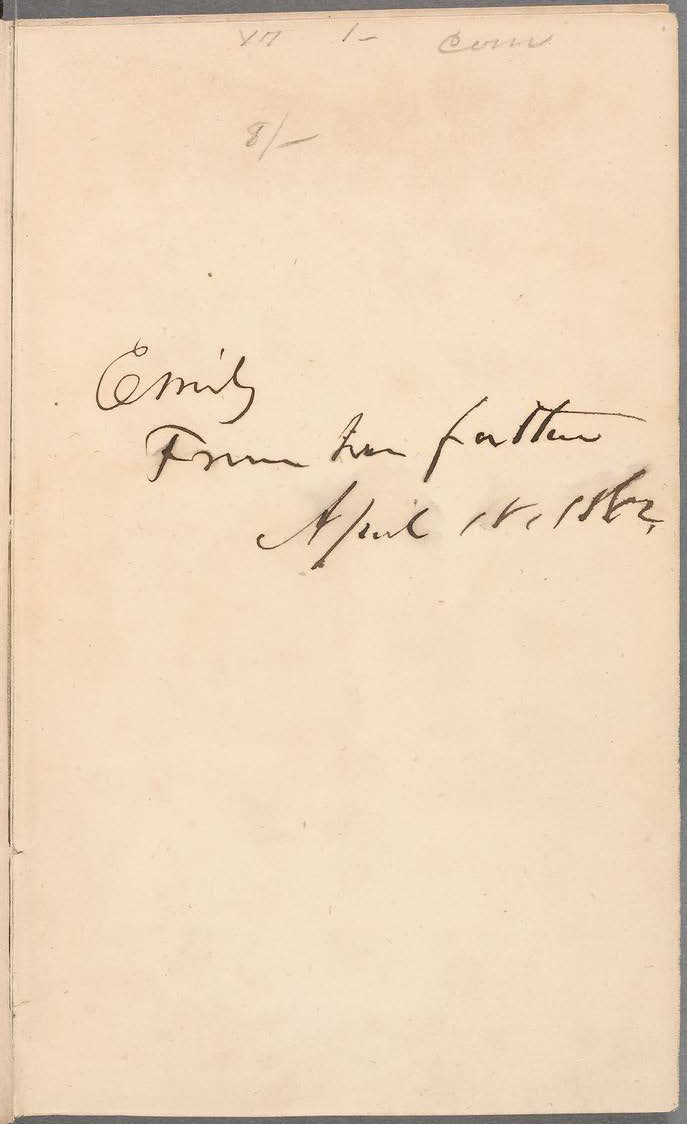

Figures 25 and 26. Cover and inscription, “Emily E Dickinson, a present from her father, 1844.” The Holy Bible. Philadelphia, 1843. Dickinson family library, EDR 8. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

A second volume Dickinson received from her father was Christian Believing and Living , sermons by family friend Frederic Dan Huntington. Born into a family of Congregational clergymen turned Unitarian, Huntington was a specially valued friend of Susan Dickinson. The third religious text inscribed to Emily from her father (April 18, 1862) was William Buell Sprague’s Letters on Practical Subjects , published in 1851 (fig. 27-28). The last paternal gift, made just before Edward’s death in 1874, was The Life of Theodore Parker , by Octavius Brooks Frothingham. With her father’s death too painfully recent, Dickinson offered the book to her literary preceptor Thomas Wentworth Higginson a year later. Her first encounter with the writings of the Unitarian transcendentalist and abolitionist Parker came in 1859 when Mary Bowles sent her The Two Christmas Celebrations as a holiday present. “I never read before what Mr. Parker wrote. I heard that he was ‘poison’. Then I like poison very well,” Dickinson wrote with obvious relish. She wasn’t the only one: “Austin stayed from service yesterday afternoon, and I, calling upon him, found him reading my Christmas gift” (L 213, 2:358-59). An example of Parker’s “poison” is his statement, “I believe that Jesus Christ taught eternal torment—I do not accept it on his authority” (Parker, from “Two Sermons,” qtd. in Bartlett, 15n). In light of such heresy, the fact that Edward Dickinson gave his daughter a gift that would appeal to her theological interests, no matter his own views, seems a clear indication that he was not as doctrinaire as might be assumed.

Figures 27 and 28. Inscription, “Emily from her father, April 18, 1862,” and title page. Letters on Practical Subjects to a Daughter . Albany, 1851. Dickinson family library, EDR 528. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

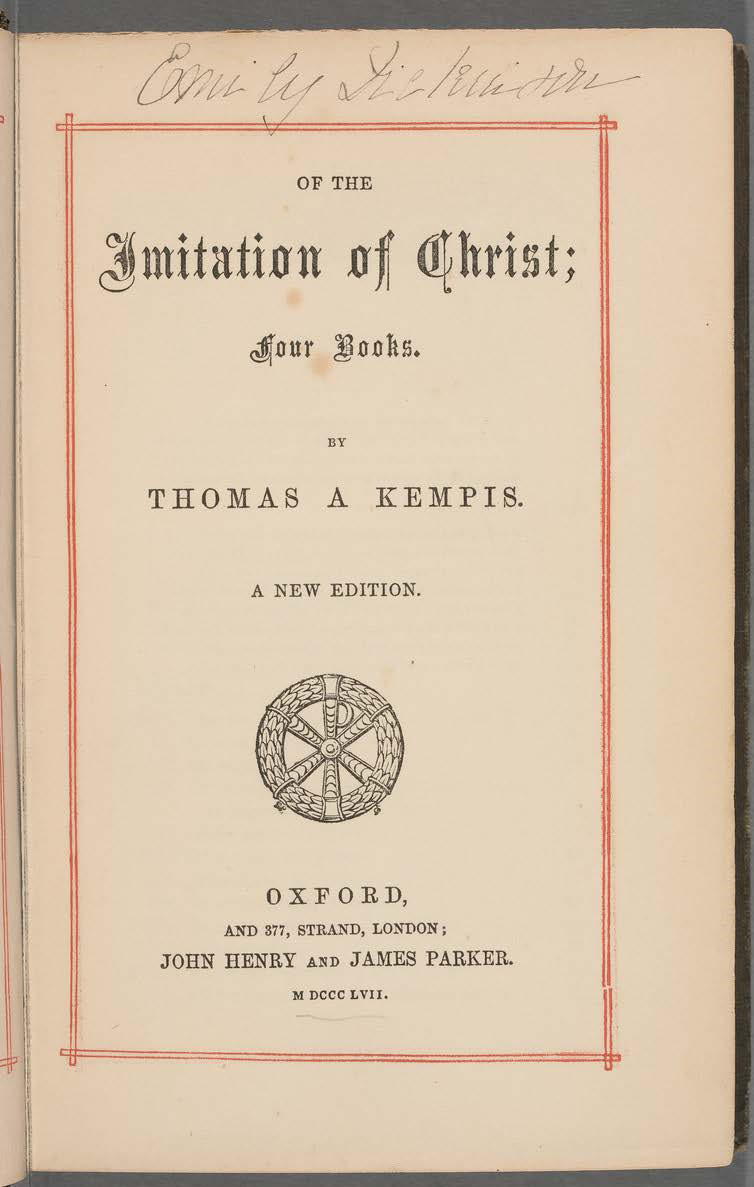

Two additional texts Emily owned that are significant and suggestive of her struggles with faith are Thomas a Kempis’ Of the Imitation of Christ , a gift from Susan, which she kept in her bedroom (fig. 29), and John Foster’s Miscellaneous Essays on Christian Morals; Experimental and Practical (fig. 30).

Figure 29. Title page. Thomas à Kempis, Of the Imitation of Christ . Oxford, 1857. Dickinson family library, EDR 529. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Figure 30. Title page. John Foster, Miscellaneous Essays on Christian Morals . New York; Philadelphia, 1844. Dickinson family library, EDR 136. Houghton Library, Harvard University.