How to Write the AP Lit Prose Essay with Examples

March 30, 2024

AP Lit Prose Essay Examples – The College Board’s Advanced Placement Literature and Composition Course is one of the most enriching experiences that high school students can have. It exposes you to literature that most people don’t encounter until college , and it helps you develop analytical and critical thinking skills that will enhance the quality of your life, both inside and outside of school. The AP Lit Exam reflects the rigor of the course. The exam uses consistent question types, weighting, and scoring parameters each year . This means that, as you prepare for the exam, you can look at previous questions, responses, score criteria, and scorer commentary to help you practice until your essays are perfect.

What is the AP Lit Free Response testing?

In AP Literature, you read books, short stories, and poetry, and you learn how to commit the complex act of literary analysis . But what does that mean? Well, “to analyze” literally means breaking a larger idea into smaller and smaller pieces until the pieces are small enough that they can help us to understand the larger idea. When we’re performing literary analysis, we’re breaking down a piece of literature into smaller and smaller pieces until we can use those pieces to better understand the piece of literature itself.

So, for example, let’s say you’re presented with a passage from a short story to analyze. The AP Lit Exam will ask you to write an essay with an essay with a clear, defensible thesis statement that makes an argument about the story, based on some literary elements in the short story. After reading the passage, you might talk about how foreshadowing, allusion, and dialogue work together to demonstrate something essential in the text. Then, you’ll use examples of each of those three literary elements (that you pull directly from the passage) to build your argument. You’ll finish the essay with a conclusion that uses clear reasoning to tell your reader why your argument makes sense.

AP Lit Prose Essay Examples (Continued)

But what’s the point of all of this? Why do they ask you to write these essays?

Well, the essay is, once again, testing your ability to conduct literary analysis. However, the thing that you’re also doing behind that literary analysis is a complex process of both inductive and deductive reasoning. Inductive reasoning takes a series of points of evidence and draws a larger conclusion. Deductive reasoning departs from the point of a broader premise and draws a singular conclusion. In an analytical essay like this one, you’re using small pieces of evidence to draw a larger conclusion (your thesis statement) and then you’re taking your thesis statement as a larger premise from which you derive your ultimate conclusion.

So, the exam scorers are looking at your ability to craft a strong thesis statement (a singular sentence that makes an argument), use evidence and reasoning to support that argument, and then to write the essay well. This is something they call “sophistication,” but they’re looking for well-organized thoughts carried through clear, complete sentences.

This entire process is something you can and will use throughout your life. Law, engineering, medicine—whatever pursuit, you name it—utilizes these forms of reasoning to run experiments, build cases, and persuade audiences. The process of this kind of clear, analytical thinking can be honed, developed, and made easier through repetition.

Practice Makes Perfect

Because the AP Literature Exam maintains continuity across the years, you can pull old exam copies, read the passages, and write responses. A good AP Lit teacher is going to have you do this time and time again in class until you have the formula down. But, it’s also something you can do on your own, if you’re interested in further developing your skills.

AP Lit Prose Essay Examples

Let’s take a look at some examples of questions, answers and scorer responses that will help you to get a better idea of how to craft your own AP Literature exam essays.

In the exam in 2023, students were asked to read a poem by Alice Cary titled “Autumn,” which was published in 1874. In it, the speaker contemplates the start of autumn. Then, students are asked to craft a well-written essay which uses literary techniques to convey the speaker’s complex response to the changing seasons.

The following is an essay that received a perfect 6 on the exam. There are grammar and usage errors throughout the essay, which is important to note: even though the writer makes some mistakes, the structure and form of their argument was strong enough to merit a 6. This is what your scorers will be looking for when they read your essay.

Example Essay

Romantic and hyperbolic imagery is used to illustrate the speaker’s unenthusiastic opinion of the coming of autumn, which conveys Cary’s idea that change is difficult to accept but necessary for growth.

Romantic imagery is utilized to demonstrate the speaker’s warm regard for the season of summer and emphasize her regretfulness for autumn’s coming, conveying the uncomfortable change away from idyllic familiarity. Summer, is portrayed in the image of a woman who “from her golden collar slips/and strays through stubble fields/and moans aloud.” Associated with sensuality and wealth, the speaker implies the interconnection between a season and bounty, comfort, and pleasure. Yet, this romantic view is dismantled by autumn, causing Summer to “slip” and “stray through stubble fields.” Thus, the coming of real change dethrones a constructed, romantic personification of summer, conveying the speaker’s reluctance for her ideal season to be dethroned by something much less decorated and adored.

Summer, “she lies on pillows of the yellow leaves,/ And tries the old tunes for over an hour”, is contrasted with bright imagery of fallen leaves/ The juxtaposition between Summer’s character and the setting provides insight into the positivity of change—the yellow leaves—by its contrast with the failures of attempting to sustain old habits or practices, “old tunes”. “She lies on pillows” creates a sympathetic, passive image of summer in reaction to the coming of Autumn, contrasting her failures to sustain “old tunes.” According to this, it is understood that the speaker recognizes the foolishness of attempting to prevent what is to come, but her wishfulness to counter the natural progression of time.

Hyperbolic imagery displays the discrepancies between unrealistic, exaggerated perceptions of change and the reality of progress, continuing the perpetuation of Cary’s idea that change must be embraced rather than rejected. “Shorter and shorter now the twilight clips/The days, as though the sunset gates they crowd”, syntax and diction are used to literally separate different aspects of the progression of time. In an ironic parallel to the literal language, the action of twilight’s “clip” and the subject, “the days,” are cut off from each other into two different lines, emphasizing a sense of jarring and discomfort. Sunset, and Twilight are named, made into distinct entities from the day, dramatizing the shortening of night-time into fall. The dramatic, sudden implications for the change bring to mind the switch between summer and winter, rather than a transitional season like fall—emphasizing the Speaker’s perspective rather than a factual narration of the experience.

She says “the proud meadow-pink hangs down her head/Against the earth’s chilly bosom, witched with frost”. Implying pride and defeat, and the word “witched,” the speaker brings a sense of conflict, morality, and even good versus evil into the transition between seasons. Rather than a smooth, welcome change, the speaker is practically against the coming of fall. The hyperbole present in the poem serves to illustrate the Speaker’s perspective and ideas on the coming of fall, which are characterized by reluctance and hostility to change from comfort.

The topic of this poem, Fall–a season characterized by change and the deconstruction of the spring and summer landscape—is juxtaposed with the final line which evokes the season of Spring. From this, it is clear that the speaker appreciates beautiful and blossoming change. However, they resent that which destroys familiar paradigms and norms. Fall, seen as the death of summer, is characterized as a regression, though the turning of seasons is a product of the literal passage of time. Utilizing romantic imagery and hyperbole to shape the Speaker’s perspective, Cary emphasizes the need to embrace change though it is difficult, because growth is not possible without hardship or discomfort.

Scoring Criteria: Why did this essay do so well?

When it comes to scoring well, there are some rather formulaic things that the judges are searching for. You might think that it’s important to “stand out” or “be creative” in your writing. However, aside from concerns about “sophistication,” which essentially means you know how to organize thoughts into sentences and you can use language that isn’t entirely elementary, you should really focus on sticking to a form. This will show the scorers that you know how to follow that inductive/deductive reasoning process that we mentioned earlier, and it will help to present your ideas in the most clear, coherent way possible to someone who is reading and scoring hundreds of essays.

So, how did this essay succeed? And how can you do the same thing?

First: The Thesis

On the exam, you can either get one point or zero points for your thesis statement. The scorers said, “The essay responds to the prompt with a defensible thesis located in the introductory paragraph,” which you can read as the first sentence in the essay. This is important to note: you don’t need a flowery hook to seduce your reader; you can just start this brief essay with some strong, simple, declarative sentences—or go right into your thesis.

What makes a good thesis? A good thesis statement does the following things:

- Makes a claim that will be supported by evidence

- Is specific and precise in its use of language

- Argues for an original thought that goes beyond a simple restating of the facts

If you’re sitting here scratching your head wondering how you come up with a thesis statement off the top of your head, let me give you one piece of advice: don’t.

The AP Lit scoring criteria gives you only one point for the thesis for a reason: they’re just looking for the presence of a defensible claim that can be proven by evidence in the rest of the essay.

Second: Write your essay from the inside out

While the thesis is given one point, the form and content of the essay can receive anywhere from zero to four points. This is where you should place the bulk of your focus.

My best advice goes like this:

- Choose your evidence first

- Develop your commentary about the evidence

- Then draft your thesis statement based on the evidence that you find and the commentary you can create.

It will seem a little counterintuitive: like you’re writing your essay from the inside out. But this is a fundamental skill that will help you in college and beyond. Don’t come up with an argument out of thin air and then try to find evidence to support your claim. Look for the evidence that exists and then ask yourself what it all means. This will also keep you from feeling stuck or blocked at the beginning of the essay. If you prepare for the exam by reviewing the literary devices that you learned in the course and practice locating them in a text, you can quickly and efficiently read a literary passage and choose two or three literary devices that you can analyze.

Third: Use scratch paper to quickly outline your evidence and commentary

Once you’ve located two or three literary devices at work in the given passage, use scratch paper to draw up a quick outline. Give each literary device a major bullet point. Then, briefly point to the quotes/evidence you’ll use in the essay. Finally, start to think about what the literary device and evidence are doing together. Try to answer the question: what meaning does this bring to the passage?

A sample outline for one paragraph of the above essay might look like this:

Romantic imagery

Portrayal of summer

- Woman who “from her golden collar… moans aloud”

- Summer as bounty

Contrast with Autumn

- Autumn dismantles Summer

- “Stray through stubble fields”

- Autumn is change; it has the power to dethrone the romance of Summer/make summer a bit meaningless

Recognition of change in a positive light

- Summer “lies on pillows / yellow leaves / tries old tunes”

- Bright imagery/fallen leaves

- Attempt to maintain old practices fails: “old tunes”

- But! There is sympathy: “lies on pillows”

Speaker recognizes: she can’t prevent what is to come; wishes to embrace natural passage of time

By the time the writer gets to the end of the outline for their paragraph, they can easily start to draw conclusions about the paragraph based on the evidence they have pulled out. You can see how that thinking might develop over the course of the outline.

Then, the speaker would take the conclusions they’ve drawn and write a “mini claim” that will start each paragraph. The final bullet point of this outline isn’t the same as the mini claim that comes at the top of the second paragraph of the essay, however, it is the conclusion of the paragraph. You would do well to use the concluding thoughts from your outline as the mini claim to start your body paragraph. This will make your paragraphs clear, concise, and help you to construct a coherent argument.

Repeat this process for the other one or two literary devices that you’ve chosen to analyze, and then: take a step back.

Fourth: Draft your thesis

Once you quickly sketch out your outline, take a moment to “stand back” and see what you’ve drafted. You’ll be able to see that, among your two or three literary devices, you can draw some commonality. You might be able to say, as the writer did here, that romantic and hyperbolic imagery “illustrate the speaker’s unenthusiastic opinion of the coming of autumn,” ultimately illuminating the poet’s idea “that change is difficult to accept but necessary for growth.”

This is an original argument built on the evidence accumulated by the student. It directly answers the prompt by discussing literary techniques that “convey the speaker’s complex response to the changing seasons.” Remember to go back to the prompt and see what direction they want you to head with your thesis, and craft an argument that directly speaks to that prompt.

Then, move ahead to finish your body paragraphs and conclusion.

Fifth: Give each literary device its own body paragraph

In this essay, the writer examines the use of two literary devices that are supported by multiple pieces of evidence. The first is “romantic imagery” and the second is “hyperbolic imagery.” The writer dedicates one paragraph to each idea. You should do this, too.

This is why it’s important to choose just two or three literary devices. You really don’t have time to dig into more. Plus, more ideas will simply cloud the essay and confuse your reader.

Using your outline, start each body paragraph with a “mini claim” that makes an argument about what it is you’ll be saying in your paragraph. Lay out your pieces of evidence, then provide commentary for why your evidence proves your point about that literary device.

Move onto the next literary device, rinse, and repeat.

Sixth: Commentary and Conclusion

Finally, you’ll want to end this brief essay with a concluding paragraph that restates your thesis, briefly touches on your most important points from each body paragraph, and includes a development of the argument that you laid out in the essay.

In this particular example essay, the writer concludes by saying, “Utilizing romantic imagery and hyperbole to shape the Speaker’s perspective, Cary emphasizes the need to embrace change though it is difficult, because growth is not possible without hardship or discomfort.” This is a direct restatement of the thesis. At this point, you’ll have reached the end of your essay. Great work!

Seventh: Sophistication

A final note on scoring criteria: there is one point awarded to what the scoring criteria calls “sophistication.” This is evidenced by the sophistication of thought and providing a nuanced literary analysis, which we’ve already covered in the steps above.

There are some things to avoid, however:

- Sweeping generalizations, such as, “From the beginning of human history, people have always searched for love,” or “Everyone goes through periods of darkness in their lives, much like the writer of this poem.”

- Only hinting at possible interpretations instead of developing your argument

- Oversimplifying your interpretation

- Or, by contrast, using overly flowery or complex language that does not meet your level of preparation or the context of the essay.

Remember to develop your argument with nuance and complexity and to write in a style that is academic but appropriate for the task at hand.

If you want more practice or to check out other exams from the past, go to the College Board’s website .

Brittany Borghi

After earning a BA in Journalism and an MFA in Nonfiction Writing from the University of Iowa, Brittany spent five years as a full-time lecturer in the Rhetoric Department at the University of Iowa. Additionally, she’s held previous roles as a researcher, full-time daily journalist, and book editor. Brittany’s work has been featured in The Iowa Review, The Hopkins Review, and the Pittsburgh City Paper, among others, and she was also a 2021 Pushcart Prize nominee.

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Essay

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High School Success

- High Schools

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Private High School Spotlight

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

Sign Up Now

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write the AP Lit Prose Essay + Example

Do you know how to improve your profile for college applications.

See how your profile ranks among thousands of other students using CollegeVine. Calculate your chances at your dream schools and learn what areas you need to improve right now — it only takes 3 minutes and it's 100% free.

Show me what areas I need to improve

What’s Covered

What is the ap lit prose essay, how will ap scores affect my college chances.

AP Literature and Composition (AP Lit), not to be confused with AP English Language and Composition (AP Lang), teaches students how to develop the ability to critically read and analyze literary texts. These texts include poetry, prose, and drama. Analysis is an essential component of this course and critical for the educational development of all students when it comes to college preparation. In this course, you can expect to see an added difficulty of texts and concepts, similar to the material one would see in a college literature course.

While not as popular as AP Lang, over 380,136 students took the class in 2019. However, the course is significantly more challenging, with only 49.7% of students receiving a score of three or higher on the exam. A staggeringly low 6.2% of students received a five on the exam.

The AP Lit exam is similar to the AP Lang exam in format, but covers different subject areas. The first section is multiple-choice questions based on five short passages. There are 55 questions to be answered in 1 hour. The passages will include at least two prose fiction passages and two poetry passages and will account for 45% of your total score. All possible answer choices can be found within the text, so you don’t need to come into the exam with prior knowledge of the passages to understand the work.

The second section contains three free-response essays to be finished in under two hours. This section accounts for 55% of the final score and includes three essay questions: the poetry analysis essay, the prose analysis essay, and the thematic analysis essay. Typically, a five-paragraph format will suffice for this type of writing. These essays are scored holistically from one to six points.

Today we will take a look at the AP Lit prose essay and discuss tips and tricks to master this section of the exam. We will also provide an example of a well-written essay for review.

The AP Lit prose essay is the second of the three essays included in the free-response section of the AP Lit exam, lasting around 40 minutes in total. A prose passage of approximately 500 to 700 words and a prompt will be given to guide your analytical essay. Worth about 18% of your total grade, the essay will be graded out of six points depending on the quality of your thesis (0-1 points), evidence and commentary (0-4 points), and sophistication (0-1 points).

While this exam seems extremely overwhelming, considering there are a total of three free-response essays to complete, with proper time management and practiced skills, this essay is manageable and straightforward. In order to enhance the time management aspect of the test to the best of your ability, it is essential to understand the following six key concepts.

1. Have a Clear Understanding of the Prompt and the Passage

Since the prose essay is testing your ability to analyze literature and construct an evidence-based argument, the most important thing you can do is make sure you understand the passage. That being said, you only have about 40 minutes for the whole essay so you can’t spend too much time reading the passage. Allot yourself 5-7 minutes to read the prompt and the passage and then another 3-5 minutes to plan your response.

As you read through the prompt and text, highlight, circle, and markup anything that stands out to you. Specifically, try to find lines in the passage that could bolster your argument since you will need to include in-text citations from the passage in your essay. Even if you don’t know exactly what your argument might be, it’s still helpful to have a variety of quotes to use depending on what direction you take your essay, so take note of whatever strikes you as important. Taking the time to annotate as you read will save you a lot of time later on because you won’t need to reread the passage to find examples when you are in the middle of writing.

Once you have a good grasp on the passage and a solid array of quotes to choose from, you should develop a rough outline of your essay. The prompt will provide 4-5 bullets that remind you of what to include in your essay, so you can use these to structure your outline. Start with a thesis, come up with 2-3 concrete claims to support your thesis, back up each claim with 1-2 pieces of evidence from the text, and write a brief explanation of how the evidence supports the claim.

2. Start with a Brief Introduction that Includes a Clear Thesis Statement

Having a strong thesis can help you stay focused and avoid tangents while writing. By deciding the relevant information you want to hit upon in your essay up front, you can prevent wasting precious time later on. Clear theses are also important for the reader because they direct their focus to your essential arguments.

In other words, it’s important to make the introduction brief and compact so your thesis statement shines through. The introduction should include details from the passage, like the author and title, but don’t waste too much time with extraneous details. Get to the heart of your essay as quick as possible.

3. Use Clear Examples to Support Your Argument

One of the requirements AP Lit readers are looking for is your use of evidence. In order to satisfy this aspect of the rubric, you should make sure each body paragraph has at least 1-2 pieces of evidence, directly from the text, that relate to the claim that paragraph is making. Since the prose essay tests your ability to recognize and analyze literary elements and techniques, it’s often better to include smaller quotes. For example, when writing about the author’s use of imagery or diction you might pick out specific words and quote each word separately rather than quoting a large block of text. Smaller quotes clarify exactly what stood out to you so your reader can better understand what are you saying.

Including smaller quotes also allows you to include more evidence in your essay. Be careful though—having more quotes is not necessarily better! You will showcase your strength as a writer not by the number of quotes you manage to jam into a paragraph, but by the relevance of the quotes to your argument and explanation you provide. If the details don’t connect, they are merely just strings of details.

4. Discussion is Crucial to Connect Your Evidence to Your Argument

As the previous tip explained, citing phrases and words from the passage won’t get you anywhere if you don’t provide an explanation as to how your examples support the claim you are making. After each new piece of evidence is introduced, you should have a sentence or two that explains the significance of this quote to the piece as a whole.

This part of the paragraph is the “So what?” You’ve already stated the point you are trying to get across in the topic sentence and shared the examples from the text, so now show the reader why or how this quote demonstrates an effective use of a literary technique by the author. Sometimes students can get bogged down by the discussion and lose sight of the point they are trying to make. If this happens to you while writing, take a step back and ask yourself “Why did I include this quote? What does it contribute to the piece as a whole?” Write down your answer and you will be good to go.

5. Write a Brief Conclusion

While the critical part of the essay is to provide a substantive, organized, and clear argument throughout the body paragraphs, a conclusion provides a satisfying ending to the essay and the last opportunity to drive home your argument. If you run out of time for a conclusion because of extra time spent in the preceding paragraphs, do not worry, as that is not fatal to your score.

Without repeating your thesis statement word for word, find a way to return to the thesis statement by summing up your main points. This recap reinforces the arguments stated in the previous paragraphs, while all of the preceding paragraphs successfully proved the thesis statement.

6. Don’t Forget About Your Grammar

Though you will undoubtedly be pressed for time, it’s still important your essay is well-written with correct punctuating and spelling. Many students are able to write a strong thesis and include good evidence and commentary, but the final point on the rubric is for sophistication. This criteria is more holistic than the former ones which means you should have elevated thoughts and writing—no grammatical errors. While a lack of grammatical mistakes alone won’t earn you the sophistication point, it will leave the reader with a more favorable impression of you.

Discover your chances at hundreds of schools

Our free chancing engine takes into account your history, background, test scores, and extracurricular activities to show you your real chances of admission—and how to improve them.

[amp-cta id="9459"]

Here are Nine Must-have Tips and Tricks to Get a Good Score on the Prose Essay:

- Carefully read, review, and underline key instruction s in the prompt.

- Briefly outlin e what you want to cover in your essay.

- Be sure to have a clear thesis that includes the terms mentioned in the instructions, literary devices, tone, and meaning.

- Include the author’s name and title in your introduction. Refer to characters by name.

- Quality over quantity when it comes to picking quotes! Better to have a smaller number of more detailed quotes than a large amount of vague ones.

- Fully explain how each piece of evidence supports your thesis .

- Focus on the literary techniques in the passage and avoid summarizing the plot.

- Use transitions to connect sentences and paragraphs.

- Keep your introduction and conclusion short, and don’t repeat your thesis verbatim in your conclusion.

Here is an example essay from 2020 that received a perfect 6:

[1] In this passage from a 1912 novel, the narrator wistfully details his childhood crush on a girl violinist. Through a motif of the allure of musical instruments, and abundant sensory details that summon a vivid image of the event of their meeting, the reader can infer that the narrator was utterly enraptured by his obsession in the moment, and upon later reflection cannot help but feel a combination of amusement and a resummoning of the moment’s passion.

[2] The overwhelming abundance of hyper-specific sensory details reveals to the reader that meeting his crush must have been an intensely powerful experience to create such a vivid memory. The narrator can picture the “half-dim church”, can hear the “clear wail” of the girl’s violin, can see “her eyes almost closing”, can smell a “faint but distinct fragrance.” Clearly, this moment of discovery was very impactful on the boy, because even later he can remember the experience in minute detail. However, these details may also not be entirely faithful to the original experience; they all possess a somewhat mysterious quality that shows how the narrator may be employing hyperbole to accentuate the girl’s allure. The church is “half-dim”, the eyes “almost closing” – all the details are held within an ethereal state of halfway, which also serves to emphasize that this is all told through memory. The first paragraph also introduces the central conciet of music. The narrator was drawn to the “tones she called forth” from her violin and wanted desperately to play her “accompaniment.” This serves the double role of sensory imagery (with the added effect of music being a powerful aural image) and metaphor, as the accompaniment stands in for the narrator’s true desire to be coupled with his newfound crush. The musical juxtaposition between the “heaving tremor of the organ” and the “clear wail” of her violin serves to further accentuate how the narrator percieved the girl as above all other things, as high as an angel. Clearly, the memory of his meeting his crush is a powerful one that left an indelible impact on the narrator.

[3] Upon reflecting on this memory and the period of obsession that followed, the narrator cannot help but feel amused at the lengths to which his younger self would go; this is communicated to the reader with some playful irony and bemused yet earnest tone. The narrator claims to have made his “first and last attempts at poetry” in devotion to his crush, and jokes that he did not know to be “ashamed” at the quality of his poetry. This playful tone pokes fun at his childhood self for being an inexperienced poet, yet also acknowledges the very real passion that the poetry stemmed from. The narrator goes on to mention his “successful” endeavor to conceal his crush from his friends and the girl; this holds an ironic tone because the narrator immediately admits that his attempts to hide it were ill-fated and all parties were very aware of his feelings. The narrator also recalls his younger self jumping to hyperbolic extremes when imagining what he would do if betrayed by his love, calling her a “heartless jade” to ironically play along with the memory. Despite all this irony, the narrator does also truly comprehend the depths of his past self’s infatuation and finds it moving. The narrator begins the second paragraph with a sentence that moves urgently, emphasizing the myriad ways the boy was obsessed. He also remarks, somewhat wistfully, that the experience of having this crush “moved [him] to a degree which now [he] can hardly think of as possible.” Clearly, upon reflection the narrator feels a combination of amusement at the silliness of his former self and wistful respect for the emotion that the crush stirred within him.

[4] In this passage, the narrator has a multifaceted emotional response while remembering an experience that was very impactful on him. The meaning of the work is that when we look back on our memories (especially those of intense passion), added perspective can modify or augment how those experiences make us feel

More essay examples, score sheets, and commentaries can be found at College Board .

While AP Scores help to boost your weighted GPA, or give you the option to get college credit, AP Scores don’t have a strong effect on your admissions chances . However, colleges can still see your self-reported scores, so you might not want to automatically send scores to colleges if they are lower than a 3. That being said, admissions officers care far more about your grade in an AP class than your score on the exam.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Calculate for all schools

Your chance of acceptance, your chancing factors, extracurriculars, writing a prose essay.

I've got an assignment to write a prose essay, but I'm not exactly sure what that means. Can any of you help me understand the definition of a prose essay and maybe some tips on how to write one?

A prose essay is a type of essay written in prose, which is a natural, flowing form of language, as opposed to verse or poetry. Essentially, when you're asked to write a prose essay, you're being asked to write an essay in complete sentences, organized into paragraphs, that clearly communicates your thoughts and ideas.

To write a prose essay, follow these steps:

1. Understand the prompt: Read the essay prompt or question carefully and make sure you fully comprehend what is being asked of you. Ask your teacher if you're unclear about what the point of the question is.

2. Brainstorm and outline: Jot down your thoughts and ideas related to the prompt and begin organizing them into a logical structure. Create an outline to serve as the framework for your essay, with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion.

3. Introduction: Start with an engaging opening line that grabs the reader's attention and introduces the topic. Provide some background information and outline the main points you plan to cover in the essay.

4. Body paragraphs: Each paragraph should focus on a single main point that supports your overall argument. Use evidence, examples, and analysis to back up your claims and explain how they connect to the essay's central theme.

5. Transitions: Smoothly transition between paragraphs and ideas with appropriate phrases and sentences. This will help improve the readability and flow of your essay.

6. Conclusion: Summarize the most important points made in the body paragraphs and restate the thesis or main argument. Offer some insight or thoughts about the implications of your analysis.

7. Edit and revise: Carefully review your essay for clarity, coherence, grammar, and spelling errors—even small typos may give your reader the impression that you don't care all that much about what you're writing about. Make necessary changes to improve readability and ensure that your essay effectively addresses the prompt. Reading your essay out loud can sometimes be a good way of identifying snag points.

Finally, remember to keep your language clear and concise, while still using a variety of sentence structures and vocabulary to make your essay more engaging. Good luck with your prose essay assignment!

About CollegeVine’s Expert FAQ

CollegeVine’s Q&A seeks to offer informed perspectives on commonly asked admissions questions. Every answer is refined and validated by our team of admissions experts to ensure it resonates with trusted knowledge in the field.

What Is Prose? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Prose definition.

Prose (PROHzuh) is written language that appears in its ordinary form, without metrical structure or line breaks. This definition is an example of prose writing, as are most textbooks and instruction manuals, emails and letters, fiction writing, newspaper and magazine articles, research papers, conversations, and essays.

The word prose first entered English circa 1300 and meant “story, narration.” It came from the Old French prose (13th century), via the Latin prosa oratio , meaning “straightforward or direct speech.” Its meaning of “prose-writing; not poetry” arrived in the mid-14th century.

Types of Prose Writing

Prose writing can appear in many forms. These are some of the most common:

- Heroic prose: Literary works of heroic prose, which may be written down or recited, employ many of the same tropes found in the oral tradition. Examples of this would include the Norse Prose Edda or other legends and tales.

- Nonfictional prose: This is prose based on facts, real events, and real people, such as biography , autobiography , history, or journalism.

- Prose fiction: Literary works in this style are imagined. Parts may be based on or inspired by real-life events or people, but the work itself is the product of an author’s imagination. Examples of this would include novels and short stories.

- Purple Prose: The term purple prose carries a negative connotation. It refers to prose that is too elaborate, ornate, or flowery. It’s categorized by excessive use of adverbs, adjectives, and bad metaphors .

Prose and Verse

While both are styles of writing, there are certain key differences between prose, which is used in standard writing, and verse, which is typically used for poetry .

As stated, prose follows the natural patterns of speech. It’s formed through common grammatical structures, such as sentences that are built into paragraphs. For example, in the opening paragraph of Diana Spechler’s New York Times article “ Among the Healers ,” she writes:

We arrive at noon and take our numbers. The more motivated, having traveled from all over Mexico, began showing up at 3 a.m. About half of the 80 people ahead of us sit in the long waiting room on benches that line the walls, while others stand clustered outside or kill the long hours wandering around Tonalá, a suburb of Guadalajara known for its artisans, its streets edged with handmade furniture, vases as tall as men, mushrooms constructed of shiny tiles. Rafael, the healer, has been receiving one visitor after another since 5. That’s what he does every day except Sunday, every week of his life.

Although Spechler utilizes some of the literary devices often associated with verse, such as strong imagery and simile , she doesn’t follow any poetic conventions. This piece of writing is comprised of sentences, which means it is written in prose.

Unlike prose, verse is formed through patterns of meter , rhyme , line breaks, and stanzaic structure—all aspects that relate to writing poems . For example, the free verse poem “ I am Trying to Break Your Heart ” by Kevin Young begins:

I am hoping

to hang your head

While this poem doesn’t utilize meter or rhyme, it’s categorized as verse because it’s composed in short two-line stanzaic units called couplets . The remainder of the poem is comprised of couplets and the occasional monostich (one-line stanza).

- Prose Poetry

Although verse and prose are different, there is a form that combines the two: prose poetry. Poems in this vein contains poetic devices, such as imagery, white space, figurative language , sound devices , alliteration , rhyme , rhythm , repetition, and heightened emotions. However, it’s written in prose form—sentences and paragraphs—instead of stanzas.

Examples of Prose in Literature

1. José Olivarez “ Ars Poetica ”

In this prose poem, Olivarez writes:

Migration is derived from the word “migrate,” which is a verb defined by Merriam-Webster as “to move from one country, place, or locality to another.” Plot twist: migration never ends. My parents moved from Jalisco, México to Chicago in 1987. They were dislocated from México by capitalism, and they arrived in Chicago just in time to be dislocated by capitalism. Question: is migration possible if there is no “other” land to arrive in. My work: to imagine. My family started migrating in 1987 and they never stopped. I was born mid-migration. I’ve made my home in that motion. Let me try again: I tried to become American, but America is toxic. I tried to become Mexican, but México is toxic. My work: to do more than reproduce the toxic stories I inherited and learned. In other words: just because it is art doesn’t mean it is inherently nonviolent. My work: to write poems that make my people feel safe, seen, or otherwise loved. My work: to make my enemies feel afraid, angry, or otherwise ignored. My people: my people. My enemies: capitalism. Susan Sontag: “victims are interested in the representation of their own sufferings.” Remix: survivors are interested in the representation of their own survival. My work: survival. Question: Why poems? Answer:

Olivarez crafted this poem in prose form rather than verse. He uses literary techniques such as surprising syntax, white space, heightened emotion, and unexpected turns to heighten the poetic elements of his work, but he doesn’t utilize verse tools, such as meter, rhyme, line breaks, or stanzaic structure.

2. Herman Melville, Moby Dick

Melville’s novel is a classic work of prose fiction, often referenced as The Great American Novel. It opens with the following lines:

Call me Ishmael. Some years ago—never mind how long precisely—having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world.

3. Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark

Playing in the Dark , which examines American literature through the lens of race, freedom, and individualism, was originally delivered while Morrison was a guest speaker at Harvard University. She begins:

These chapters put forth an argument for extending the study of American literature into what I hope will be a wider landscape. I want to draw a map, so to speak, of a critical geography and use that map to open as much space for discovery, intellectual adventure, and close exploration as did the original charting of the New World—without the mandate for conquest.

Further Resources on Prose

David Lehman edited a wonderful anthology of prose poetry called Great American Prose Poems: From Poe to the Present .

For fans of prose in fiction, the editors of Modern Library put together a list of the 100 greatest novels .

Nonfiction prose fans may enjoy Longform , which curates and links to new and classic nonfiction from around the web.

Related Terms

- Blank Verse

- Literary Terms

- When & How to Write a Prose

- Definition & Examples

How to Write Prose

There’s just one rule for writing prose: don’t write verse by mistake. If you grew up in the modern world, chances are you’ve been writing prose since the day you started stringing sentences together on a page. So all you have to do now is keep it up!

- In general, prose does not have line breaks; rather, it has complete sentences with periods or other punctuation marks.

- There’s another very important kind of line break that makes your prose easier to understand: paragraph breaks. Paragraphs break up your writing into manageable chunks that the reader can digest one at a time as they read. This is especially important in essays , where each paragraph contains a single “step” in the argument. Without paragraph breaks, prose becomes pretty ugly: just a huge block of words without any breaks or structure at all!

When to Use Prose

Unless you’re writing poetry, you’re writing prose. (Remember that prose has a negative definition.) As we saw in §2, essays use prose. This is mainly just a convention – it’s what readers are used to, so it’s what writers use. In the modern world, we generally find prose easier to read, so readers prefer to have essays written that way. The same thing is true for stories – we have an easier time following the story when it’s written in prose simply because it’s what we’re accustomed to.

So you can use prose pretty much anywhere – poetry is the only kind of writing that frequently uses verse, meaning prose covers everything else . And even poetry, as we’ve seen, can be written in prose. So when should you use prose? The answer is: all over the place.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

- Scriptwriting

What is Prose — Definition and Examples in Literature

- What is a Poem

- What is a Stanza in a Poem

- What is Dissonance

- What is a Sonnet

- What is a Haiku

- What is Prose

- What is an Ode

- What is Repetition in Poetry

- How to Write a Poem

- Types of Poems Guide

- What is an Acrostic Poem

- What is an Epic Poem

- What is Lyric Poetry

P rose can be a rather general literary term that many use to describe all types of writing. However, prose by definition pertains to specific qualities of writing that we will dive into in this article. What is the difference between prose and poetry and what is prose used for? Let’s define this essential literary concept and look at some examples to find out.

What is Prose in Literature?

First, let’s define prose.

Prose is used in various ways for various purposes. It's a concept you need to understand if your goal to master the literary form. Before we dive in, it’s important to understand the prose definition and how it is distinguished from other styles of writing.

PROSE DEFINITION

What is prose.

In writing, prose is a style used that does not follow a structure of rhyming or meter. Rather, prose follows a grammatical structure using words to compose phrases that are arranged into sentences and paragraphs. It is used to directly communicate concepts, ideas, and stories to a reader. Prose follows an almost naturally verbal flow of writing that is most common among fictional and non-fictional literature such as novels, magazines, and journals.

Four types of prose:

Nonfictional prose, fictional prose, prose poetry, heroic prose, prose meaning , prose vs poetry.

To better understand prose, it’s important to understand what structures it does not follow which would be the structure of poetry. Let’s analyze the difference between prose vs poetry.

Poetry follows a specific rhyme and metric structure. These are often lines and stanzas within a poem. Poetry also utilizes more figurative and often ambiguous language that purposefully leaves room for the readers’ analysis and interpretation.

Finally, poetry plays with space on a page. Intentional line breaks, negative space, and varying line lengths make poetry a more aesthetic form of writing than prose.

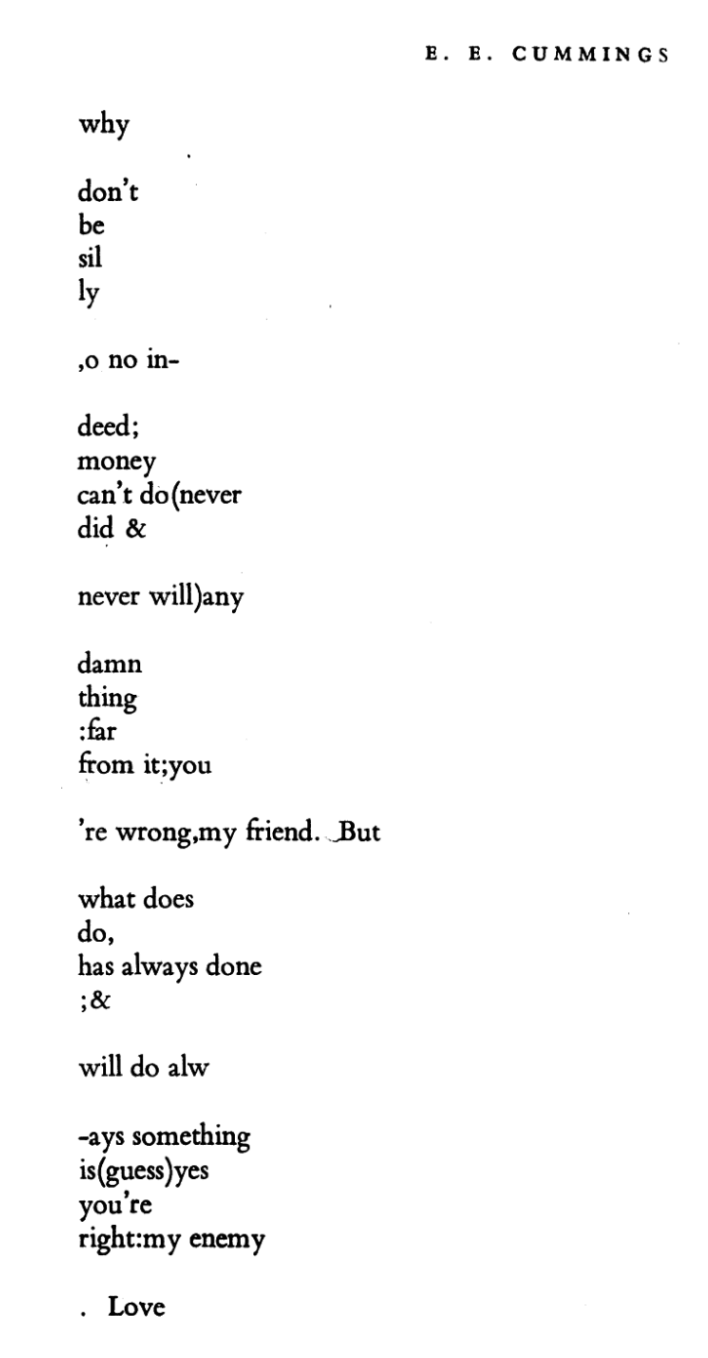

Take, for example, the structure of this [Why] by E.E. Cummings. Observe his use of space and aesthetics as well as metric structure in the poem.

E.E. Cummings Poem

E.E. Cummings may be one of the more stylish poets when it comes to use of page space. But poetry is difference in structure and practice than prose.

Prose follows a structure that makes use of sentences, phrases, and paragraphs. This type of writing follows a flow more similar to verbal speech and communication. This makes it the best style of writing to clearly articulate and communicate concepts, events, stories, and ideas as opposed to the figurative style of poetry.

What is Prose in Literature?

Take, for example, the opening paragraph of JD Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye . We can tell immediately the prose is written in a direct, literal way that also gives voice to our protagonist .

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.

From this example, you can see how the words flow more conversationally than poetry and is more direct with what information or meaning is being communicated. Now that you understand the difference between poetry, let’s look at the four types of prose.

Related Posts

- What is Litotes — Definition and Examples →

- Different Types of Poems and Poem Structures →

- What is Iambic Pentameter? Definition and Examples →

Prose Examples

Types of prose.

While all four types of prose adhere to the definition we established, writers use the writing style for different purposes. These varying purposes can be categorized into four different types.

Nonfictional prose is a body of writing that is based on factual and true events. The information is not created from a writer’s imagination, but rather true accounts of real events.

This type can be found in newspapers, magazines, journals, biographies, and textbooks. Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl , for example, is a work written in nonfictional style.

Unlike nonfictional, fictional prose is partly or wholly created from a writer’s imagination. The events, characters, and story are imagined such as Romeo and Juliet , The Adventures of Tom Sawyer , or Brave New World . This type is found as novels, short stories, or novellas .

Heroic prose is a work of writing that is meant to be recited and passed on through oral or written tradition. Legends, mythology, fables, and parables are examples of heroic prose that have been passed on over time in preservation.

Finally, prose poetry is poetry that is expressed and written in prose form. This can be thought of almost as a hybrid of the two that can sometimes utilize rhythmic measures. This type of poetry often utilizes more figurative language but is usually written in paragraph form.

An example of prose poetry is “Spring Day” by Amy Lowell. Lowell, an American poet, published this in 1916 and can be read almost as hyper short stories written in a prose poetry style.

The first section can be read below:

The day is fresh-washed and fair, and there is a smell of tulips and narcissus in the air.

The sunshine pours in at the bath-room window and bores through the water in the bath-tub in lathes and planes of greenish-white. It cleaves the water into flaws like a jewel, and cracks it to bright light.

Little spots of sunshine lie on the surface of the water and dance, dance, and their reflections wobble deliciously over the ceiling; a stir of my finger sets them whirring, reeling. I move a foot, and the planes of light in the water jar. I lie back and laugh, and let the green-white water, the sun-flawed beryl water, flow over me. The day is almost too bright to bear, the green water covers me from the too bright day. I will lie here awhile and play with the water and the sun spots.

The sky is blue and high. A crow flaps by the window, and there is a whiff of tulips and narcissus in the air."

While these four types of prose are varying ways writers choose to use it, let’s look at the functions of them to identify the strengths of the writing style.

What Does Prose Mean in Writing

Function of prose in literature.

What is prose used for and when? Let’s say you want to tell a story, but you’re unsure if using prose or poetry would best tell your story.

To determine if the correct choice is prose, it’s important to understand the strengths of the writing style.

Direct communication

Prose, unlike poetry, is often less figurative and ambiguous. This means that a writer can be more direct with the information they are trying to communicate. This can be especially useful in storytelling, both fiction and nonfiction, to efficiently fulfill the points of a plot.

Curate a voice

Because prose is written in the flow of verbal conversation, it’s incredibly effective at curating a specific voice for a character. Dialogue within novels and short stories benefit from this style.

Think about someone you know and how they talk. Odds are, much of their character and personality can be found in their voice.

When creating characters, prose enables a writer to curate the voice of that character. For example, one of the most iconic opening lines in literature informs us of what type of character we will be following.

Albert Camus’ The Stranger utilizes prose in first person to establish the voice of the story’s protagonist.

“Mother died today. Or, maybe, yesterday; I can’t be sure. The telegram from the Home says: YOUR MOTHER PASSED AWAY. FUNERAL TOMORROW. DEEP SYMPATHY. Which leaves the matter doubtful; it could have been yesterday.”

Build rapport with the reader

Lastly, in addition to giving character’s a curated voice, prose builds rapport with the reader. The conversational tone allows readers to become familiar with a type of writing that connects them with the writer.

A great example of this is Hunter S. Thompson’s Hell’s Angels . As a nonfiction work written in prose, Thompson’s voice and style in the writing is distinct and demands a relationship with the reader.

Whether it is one of contradiction or agreement, the connection exists through the prose. It is a connection that makes a reader want to meet or talk with the writer once they finish their work.

Prose is one of the most common writing styles for modern writers. But truly mastering it means understanding both its strengths and its shortcomings.

Different Types of Poems

Curious about learning about the counterpart to prose? In our next article we dive in different types of poems as well as different types of poem structures. Check out the complete writer’s guide to poetry types up next.

Up Next: Types of Poems →

Write and produce your scripts all in one place..

Write and collaborate on your scripts FREE . Create script breakdowns, sides, schedules, storyboards, call sheets and more.

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- The Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets (with FREE Call Sheet Template)

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- What is the Rule of Three — A Literary Device for Writers

- Best Free Crime Movie Scripts Online (with PDF Downloads)

- What is a Graphic Novel — The Art of Pictorial Storytelling

- Types of Animation — Styles, Genres & Techniques

- What is an Apple Box in Film — Film Set Essentials

- 1 Pinterest

What Is Prose?

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Prose is ordinary writing (both fiction and nonfiction ) as distinguished from verse. Most essays , compositions , reports , articles , research papers , short stories, and journal entries are types of prose writings.

In his book The Establishment of Modern English Prose (1998), Ian Robinson observed that the term prose is "surprisingly hard to define. . . . We shall return to the sense there may be in the old joke that prose is not verse."

In 1906, English philologist Henry Cecil Wyld suggested that the "best prose is never entirely remote in form from the best corresponding conversational style of the period" ( The Historical Study of the Mother Tongue ).

From the Latin, "forward" + "turn"

Observations

"I wish our clever young poets would remember my homely definitions of prose and poetry: that is, prose = words in their best order; poetry = the best words in the best order." (Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Table Talk , July 12, 1827)

Philosophy Teacher: All that is not prose is verse; and all that is not verse is prose. M. Jourdain: What? When I say: "Nicole, bring me my slippers, and give me my night-cap," is that prose? Philosophy Teacher: Yes, sir. M. Jourdain: Good heavens! For more than 40 years I have been speaking prose without knowing it. (Molière, Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme , 1671)

"For me, a page of good prose is where one hears the rain and the noise of battle. It has the power to give grief or universality that lends it a youthful beauty." (John Cheever, on accepting the National Medal for Literature, 1982)

" Prose is when all the lines except the last go on to the end. Poetry is when some of them fall short of it." (Jeremy Bentham, quoted by M. St. J. Packe in The Life of John Stuart Mill , 1954)

"You campaign in poetry. You govern in prose ." (Governor Mario Cuomo, New Republic , April 8, 1985)

Transparency in Prose

"[O]ne can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one's own personality. Good prose is like a window pane." (George Orwell, "Why I Write," 1946) "Our ideal prose , like our ideal typography, is transparent: if a reader doesn't notice it, if it provides a transparent window to the meaning, then the prose stylist has succeeded. But if your ideal prose is purely transparent, such transparency will be, by definition, hard to describe. You can't hit what you can't see. And what is transparent to you is often opaque to someone else. Such an ideal makes for a difficult pedagogy." (Richard Lanham, Analyzing Prose , 2nd ed. Continuum, 2003)

" Prose is the ordinary form of spoken or written language: it fulfills innumerable functions, and it can attain many different kinds of excellence. A well-argued legal judgment, a lucid scientific paper, a readily grasped set of technical instructions all represent triumphs of prose after their fashion. And quantity tells. Inspired prose may be as rare as great poetry--though I am inclined to doubt even that; but good prose is unquestionably far more common than good poetry. It is something you can come across every day: in a letter, in a newspaper, almost anywhere." (John Gross, Introduction to The New Oxford Book of English Prose . Oxford Univ. Press, 1998)

A Method of Prose Study

"Here is a method of prose study which I myself found the best critical practice I have ever had. A brilliant and courageous teacher whose lessons I enjoyed when I was a sixth-former trained me to study prose and verse critically not by setting down my comments but almost entirely by writing imitations of the style . Mere feeble imitation of the exact arrangement of words was not accepted; I had to produce passages that could be mistaken for the work of the author, that copied all the characteristics of the style but treated of some different subject. In order to do this at all it is necessary to make a very minute study of the style; I still think it was the best teaching I ever had. It has the added merit of giving an improved command of the English language and a greater variation in our own style." (Marjorie Boulton, The Anatomy of Prose . Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1954)

Pronunciation: PROZ

- Genres in Literature

- AP English Exam: 101 Key Terms

- An Introduction to Prose in Shakespeare

- Defining Nonfiction Writing

- Figure of Sound in Prose and Poetry

- Overview of Baroque Style in English Prose and Poetry

- Interior Monologues

- Everything You Need to Know About Shakespeare's Plays

- 12 Classic Essays on English Prose Style

- style (rhetoric and composition)

- Overview of Imagism in Poetry

- What You Should Know About Travel Writing

- Examples of Iambic Pentameter in Shakespeare's Plays

- What You Need to Know About the Epic Poem 'Beowulf'

- An Interview With Ellen Hopkins

- Creative Nonfiction

Understanding Prose in Literature: A Comprehensive Guide

Defining prose, types of prose, prose vs. verse, prose styles, narrative style, descriptive style, expository style, argumentative style, literary devices in prose, foreshadowing, analyzing prose, close reading, theme and message, notable authors and their prose, jane austen, ernest hemingway, toni morrison, prose in different cultures, greek prose, indian prose, japanese prose.

Prose in literature is a fascinating topic that has captured the attention of readers and writers for centuries. In this comprehensive guide, we will explore the different aspects of prose and how it shapes the world of literature. By understanding prose, you will be able to appreciate the beauty of written language and enhance your own writing skills. So, let's dive into the captivating world of prose in literature!

Prose is a form of written language that follows a natural, everyday speech pattern. It is the way we communicate in writing without adhering to the strict rules of poetry or verse. In literature, prose encompasses a wide range of written works, from novels and short stories to essays and articles. To better understand prose in literature, let's look at the different types of prose and how it compares to verse.

There are several types of prose in literature, each serving a unique purpose and offering a different reading experience:

- Fiction: Imaginative works, such as novels and short stories, that tell a story.

- Non-fiction: Informative works, such as essays, articles, and biographies, that present facts and real-life experiences.

- Drama: Plays and scripts written in prose form, often featuring dialogue and stage directions.

- Prose poetry: A hybrid form that combines elements of prose and poetry, creating a more fluid and expressive style.

By exploring these types of prose, you can better appreciate the versatility and depth of prose in literature.

Prose and verse are two distinct forms of written language, each with its own characteristics and purposes. Here's a quick comparison:

- Prose: Written in a natural, conversational style, prose uses sentences and paragraphs to convey meaning. It is the most common form of writing and can be found in novels, essays, articles, and other forms of literature.

- Verse: Written in a structured, rhythmic pattern, verse often uses stanzas, rhyme, and meter to create a more musical quality. It is most commonly found in poetry and song lyrics.

Understanding the differences between prose and verse can help you appreciate the unique qualities of each form and how they contribute to the richness of literature.

Just as there are different types of prose, there are also various prose styles that authors use to convey their ideas and stories. These styles can be categorized into four main groups:

The narrative style tells a story by presenting events in a sequence, typically involving characters and a plot. This style is commonly used in novels, short stories, and biographies. Some key features of the narrative style include:

- Chronological or non-chronological structure

- Use of dialogue and description

- Focus on characters, their actions, and motivations

- Development of a plot, consisting of a beginning, middle, and end

By using the narrative style, authors can create engaging stories that draw readers in and make them feel a part of the experience.

The descriptive style focuses on painting a vivid picture of a person, place, or thing. This style is used to provide detailed information and create a strong sensory experience for the reader. Some key features of the descriptive style include:

- Use of sensory language, such as sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch

- Adjectives and adverbs to enhance descriptions

- Figurative language, such as similes and metaphors, to create vivid imagery

- Attention to detail and setting

By mastering the descriptive style, authors can transport readers to new worlds and enrich their understanding of the subject matter.

The expository style is used to explain, inform, or describe a topic. This style is commonly found in textbooks, essays, and articles. Some key features of the expository style include:

- Clear, concise language

- Logical organization of information

- Use of examples, facts, and statistics to support the main idea

- An objective, unbiased tone

By employing the expository style, authors can effectively convey information and help readers gain a deeper understanding of a subject.

The argumentative style is used to persuade or convince the reader of a certain viewpoint. This style is often found in opinion pieces, essays, and debates. Some key features of the argumentative style include:

- A clear, well-defined thesis statement

- Logical organization of arguments and evidence

- Use of facts, statistics, and examples to support the thesis

- Addressing and refuting opposing viewpoints

- A persuasive, confident tone

By mastering the argumentative style, authors can effectively present their opinions and persuade readers to consider their perspective.

Understanding these different prose styles can help you appreciate the diverse ways authors use language to convey their ideas and enhance your own writing abilities.

Authors use various literary devices to enrich their prose and make it more engaging for the reader. These devices help create an emotional connection, build suspense, or bring out deeper meanings in the text. Let's explore some of the most commonly used literary devices in prose:

Imagery is the use of vivid and descriptive language to create a picture in the reader's mind. This technique appeals to the five senses and can make a piece of writing more immersive and memorable. Some examples of imagery include:

- Visual imagery: describing the appearance of a character or setting

- Auditory imagery: describing sounds, such as the rustling of leaves or the roar of a crowd

- Olfactory imagery: describing smells, such as the scent of fresh-baked cookies or the aroma of a garden

- Gustatory imagery: describing tastes, such as the sweetness of a ripe fruit or the bitterness of a cup of coffee

- Tactile imagery: describing textures and physical sensations, such as the softness of a blanket or the warmth of the sun

By using imagery, authors can create a richer, more engaging experience for the reader.

Foreshadowing is a technique used to hint at events that will occur later in the story. This can create suspense, build anticipation, and keep the reader engaged. Foreshadowing can be subtle or more direct and can take various forms, such as:

- Character dialogue or thoughts

- Symbolism or motifs

- Setting or atmosphere

- Actions or events that mirror or prefigure future events

By incorporating foreshadowing, authors can create a sense of mystery and intrigue that keeps readers turning the pages.

Allusion is a reference to a well-known person, event, or work of art, literature, or music. This technique allows authors to make connections and add depth to their writing without explicitly stating the reference. Allusions can serve various purposes, such as:

- Creating a shared understanding between the author and the reader

- Establishing a cultural, historical, or literary context

- Adding layers of meaning or symbolism

- Providing a subtle commentary or critique

By using allusion, authors can enhance their prose and engage readers with shared knowledge and cultural references.

These are just a few examples of the many literary devices that authors use to enrich their prose in literature. By understanding and recognizing these techniques, you can deepen your appreciation of the written word and perhaps even add some of these tools to your own writing repertoire.

Analyzing prose in literature involves closely examining the text to gain a deeper understanding of the author's intentions, themes, and techniques. This process can help you appreciate the nuances of the writing and uncover new insights. Let's explore some approaches to analyzing prose:

Close reading is a method of carefully examining the text to identify its structure, themes, and literary devices. This approach involves paying attention to details such as:

- Word choice and diction

- Sentence structure and syntax

- Imagery and figurative language

- Characterization and dialogue

- Setting and atmosphere

By closely examining these elements, you can gain a deeper understanding of the author's intentions and the text's overall meaning.

Identifying the theme or central message of a piece of prose is another important aspect of analysis. A theme is a recurring idea, topic, or subject that runs through the text. Some common themes in literature include:

- Love and relationships

- Identity and self-discovery

- Power and authority

- Conflict and resolution

- Nature and the environment

To identify the theme of a piece of prose, consider the overall message or lesson that the author is trying to convey. Look for patterns, motifs, and symbols that support this message. Understanding the theme can help you better appreciate the author's intentions and the text's significance.

By employing these approaches to analyzing prose in literature, you can deepen your understanding of the text and enhance your appreciation of the author's craft. Whether you're studying a classic novel or a contemporary short story, these skills will help you unlock the richness and complexity of the written word.

Throughout history, numerous authors have made significant contributions to the world of prose in literature. Their unique writing styles and innovative approaches to storytelling have left an indelible mark on the literary landscape. Let's take a closer look at some notable authors and their distinctive prose:

Jane Austen, an English author from the early 19th century, is well-known for her witty and satirical prose. Her novels often center on themes of love, marriage, and social class in the Georgian era. Examples of her work include Pride and Prejudice , Sense and Sensibility , and Emma . Austen's prose is characterized by:

- Sharp wit and humor

- Observant descriptions of characters and their social interactions

- Realistic dialogue that reveals the personalities and motivations of her characters

- Insightful commentary on societal norms and expectations of her time

Ernest Hemingway, an American author from the 20th century, is celebrated for his distinctive writing style that has had a lasting impact on prose in literature. His works often explore themes of war, love, and the human condition, such as in A Farewell to Arms , The Old Man and the Sea , and For Whom the Bell Tolls . Hemingway's prose is characterized by:

- Simple, direct language and short sentences

- An emphasis on action and external events

- Understated emotions and a focus on the physical world

- A "less is more" approach that leaves room for reader interpretation

Toni Morrison, an American author and Nobel laureate, is renowned for her powerful, evocative prose that delves into the complexities of human relationships and the African American experience. Notable works include Beloved , Song of Solomon , and The Bluest Eye . Morrison's prose is characterized by:

- Rich, lyrical language and vivid imagery

- Complex characters and multi-layered narratives

- Explorations of race, gender, and identity

- A strong sense of voice and emotional intensity

These authors, among many others, have each left their unique imprint on the realm of prose in literature. By studying their works and understanding their techniques, we can better appreciate the diverse ways in which writers can use prose to convey their stories and ideas.

Prose in literature is a global phenomenon, with each culture bringing its own distinctive style, themes, and literary traditions to the table. Let's explore how prose has developed and evolved in some cultures around the world:

Ancient Greek prose has had a profound influence on Western literature. Spanning various genres such as philosophy, history, and drama, Greek prose is known for its intellectual depth and stylistic sophistication. Key features of Greek prose include:

- Rhetorical devices like repetition, parallelism, and antithesis

- Emphasis on logic, reason, and argumentation

- Rich vocabulary and complex sentence structures

- Notable authors like Plato, Aristotle, and Herodotus

Indian prose in literature spans thousands of years and numerous languages, with each region and time period contributing its own flavor to the mix. Indian prose is often characterized by:

- Epic tales and religious texts, such as the Mahabharata and the Ramayana

- Folk tales, fables, and parables that convey moral lessons

- Ornate and poetic language, with a focus on imagery and symbolism

- Notable authors like Rabindranath Tagore, R. K. Narayan, and Arundhati Roy

Japanese prose in literature is known for its elegance, subtlety, and attention to detail. Spanning various genres such as poetry, drama, and fiction, Japanese prose often explores themes of nature, human emotion, and the passage of time. Key features of Japanese prose include:

- Haiku and other poetic forms that emphasize simplicity and precision

- Descriptions of the natural world and the changing seasons

- Understated emotions and a focus on the inner lives of characters

- Notable authors like Yasunari Kawabata, Yukio Mishima, and Haruki Murakami

By examining the diverse range of prose in literature from various cultures, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the many ways in which authors use language to tell stories, express ideas, and convey the human experience.

If you found this blog post intriguing and want to delve deeper into writing from your memories, be sure to check out Charlie Brogan's workshop, ' Writing From Memory - Part 1 .' This workshop will guide you through the process of tapping into your memories and transforming them into captivating stories. Don't miss this opportunity to enhance your writing skills and unleash your creativity!

Live classes every day

Learn from industry-leading creators

Get useful feedback from experts and peers

Best deal of the year

* billed annually after the trial ends.

*Billed monthly after the trial ends.

Find what you need to study

AP Lit Prose Analysis: Practice Prompt Samples & Feedback

9 min read • january 2, 2021

Candace Moore

Practicing Prose Analysis is a great way to prep for the AP exam! Review practice writing samples and corresponding feedback from Fiveable teacher Candace Moore.

The Practice Prompt

Notes from the teacher.

While reading, consider the following questions:

- What is the author’s language doing ?

- What choices has the author made in her language?

- What is the meaning/impact of those choices?

As if you were writing a whole essay, write a thesis that establishes

1) the relationship Petry establishes between Lutie Johnson and the setting,

2) which figurative language devices Petry employed to establish the relationship, and

3) any complexity you identified in that relationship. Start a new paragraph that analyzes one pattern of figurative language and its role in the relationship. You should have at least two pieces of evidence and at least three sentences of commentary making the connection between the language and the claim from your thesis.

Replay: Prose Analysis Thesis and Introduction

Read the selection carefully and then write an essay analyzing how Petry establishes Lutie Johnson’s relationship to the urban setting through the use of literary devices.

Passage and Prompt

Writing Samples and Feedback

Student sample 1.