- Data, AI, & Machine Learning

- Managing Technology

- Social Responsibility

- Workplace, Teams, & Culture

- AI & Machine Learning

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Big ideas Research Projects

- Artificial Intelligence and Business Strategy

- Responsible AI

- Future of the Workforce

- Future of Leadership

- All Research Projects

- AI in Action

- Most Popular

- The Truth Behind the Nursing Crisis

- Work/23: The Big Shift

- Coaching for the Future-Forward Leader

- Measuring Culture

The spring 2024 issue’s special report looks at how to take advantage of market opportunities in the digital space, and provides advice on building culture and friendships at work; maximizing the benefits of LLMs, corporate venture capital initiatives, and innovation contests; and scaling automation and digital health platform.

- Past Issues

- Upcoming Events

- Video Archive

- Me, Myself, and AI

- Three Big Points

What Makes Work Meaningful — Or Meaningless

New research offers insights into what gives work meaning — as well as into common management mistakes that can leave employees feeling that their work is meaningless.

- Workplace, Teams, & Culture

- Leadership Skills

- Managing Your Career

- Talent Management

- Organizational Behavior

Meaningful work is something we all want. The psychiatrist Viktor Frankl famously described how the innate human quest for meaning is so strong that, even in the direst circumstances, people seek out their purpose in life. 1 More recently, researchers have shown meaningfulness to be more important to employees than any other aspect of work, including pay and rewards, opportunities for promotion, or working conditions. 2 Meaningful work can be highly motivational, leading to improved performance, commitment, and satisfaction. 3 But, so far, surprisingly little research has explored where and how people find their work meaningful and the role that leaders can play in this process. 4

We interviewed 135 people working in 10 very different occupations and asked them to tell us stories about incidents or times when they found their work to be meaningful and, conversely, times when they asked themselves, “What’s the point of doing this job?” We expected to find that meaningfulness would be similar to other work-related attitudes, such as engagement or commitment, in that it would arise purely in response to situations within the work environment. However, we found that, unlike these other attitudes, meaningfulness tended to be intensely personal and individual; 5 it was often revealed to employees as they reflected on their work and its wider contribution to society in ways that mattered to them as individuals. People tended to speak of their work as meaningful in relation to thoughts or memories of significant family members such as parents or children, bridging the gap between work and the personal realm. We also expected meaningfulness to be a relatively enduring state of mind experienced by individuals toward their work; instead, our interviewees talked of unplanned or unexpected moments during which they found their work deeply meaningful.

We were anticipating that our data would show that the meaningfulness experienced by employees in relation to their work was clearly associated with actions taken by managers, such that, for example, transformational leaders would have followers who found their work meaningful, whereas transactional leaders would not. 6 Instead, our research showed that quality of leadership received virtually no mention when people described meaningful moments at work, but poor management was the top destroyer of meaningfulness.

We also expected to find a clear link between the factors that drove up levels of meaningfulness and those that eroded them. Instead, we found that meaningfulness appeared to be driven up and decreased by different factors. Whereas our interviewees tended to find meaningfulness for themselves rather than it being mandated by their managers, we discovered that if employers want to destroy that sense of meaningfulness, that was far more easily achieved. The feeling of “Why am I bothering to do this?” strikes people the instant a meaningless moment arises, and it strikes people hard. If meaningfulness is a delicate flower that requires careful nurturing, think of someone trampling over that flower in a pair of steel-toed boots. Avoiding the destruction of meaning while nurturing an ecosystem generative of feelings of meaningfulness emerged as the key leadership challenge.

The Five Qualities of Meaningful Work

Our research aimed to uncover how and why people find their work meaningful. (See “About the Research.”) For our interviewees, meaningfulness, perhaps unsurprisingly, was often associated with a sense of pride and achievement at a job well done, whether they were professionals or manual workers. Those who could see that they had fulfilled their potential, or who found their work creative, absorbing, and interesting, tended to perceive their work as more meaningful than others. Equally, receiving praise, recognition, or acknowledgment from others mattered a great deal. 7 These factors alone were not enough to render work meaningful, however. 8 Our study also revealed five unexpected features of meaningful work; in these, we find clues that might explain the fragile and intangible nature of meaningfulness.

1. Self-Transcendent

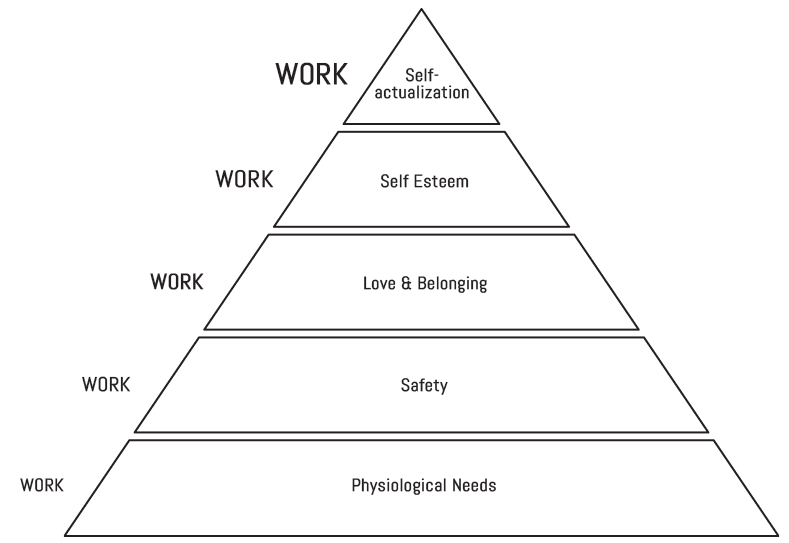

Individuals tended to experience their work as meaningful when it mattered to others more than just to themselves. In this way, meaningful work is self-transcendent. Although it is not a well-known fact, the famous motivation theorist Abraham Maslow positioned self-transcendence at the apex of his pyramid of human motivation, situating it beyond even self-actualization in importance. 9 People did not just talk about themselves when they talked about meaningful work; they talked about the impact or relevance their work had for other individuals, groups, or the wider environment. For example, a garbage collector explained how he found his work meaningful at the “tipping point” at the end of the day when refuse was sent to recycling. This was the time he could see how his work contributed to creating a clean environment for his grandchildren and for future generations. An academic described how she found her work meaningful when she saw her students graduate at the commencement ceremony, a tangible sign of how her own hard work had helped others succeed. A priest talked about the uplifting and inspiring experience of bringing an entire community together around the common goal of a church restoration project.

2. Poignant

The experience of meaningful work can be poignant rather than purely euphoric. 10 People often found their work to be full of meaning at moments associated with mixed, uncomfortable, or even painful thoughts and feelings, not just a sense of unalloyed joy and happiness. People often cried in our interviews when they talked about the times when they found their work meaningful. The current emphasis on positive psychology has led us to focus on trying to make employees happy, engaged, and enthused throughout the working day. Psychologist Barbara Held refers to the current pressure to “accentuate the positive” as the “tyranny of the positive attitude.” 11 Traditionally, meaningfulness has been linked with such positive attributes.

Our research suggests that, contrary to what we may have thought, meaningfulness is not always a positive experience. 12 In fact, those moments when people found their work meaningful tended to be far richer and more challenging than times when they felt simply motivated, engaged, or happy. The most vivid examples of this came from nurses who described moments of profound meaningfulness when they were able to use their professional skills and knowledge to ease the passing of patients at the end of their lives. Lawyers often talked about working hard for extended periods, sometimes years, for their clients and winning cases that led to life-changing outcomes. Participants in several of the occupational groups found moments of meaningfulness when they had triumphed in difficult circumstances or had solved a complex, intractable problem. The experience of coping with these challenging conditions led to a sense of meaningfulness far greater than they would have experienced dealing with straightforward, everyday situations.

3. Episodic

A sense of meaningfulness arose in an episodic rather than a sustained way. It seemed that no one could find their work consistently meaningful, but rather that an awareness that work was meaningful arose at peak times that were generative of strong experiences. For example, a university professor talked of the euphoric experience of feeling “like a rock star” at the end of a successful lecture. One actor we spoke to summed this feeling up well: “My God, I’m actually doing what I dreamt I could do; that’s kind of amazing.” Clearly, sentiments such as these are not sustainable over the course of even one single working day, let alone a longer period, but rather come and go over one’s working life, perhaps rarely arising. Nevertheless, these peak experiences have a profound effect on individuals, are highly memorable, and become part of their life narratives.

Meaningful moments such as these were not forced or managed. Only in a few instances did people tell us that an awareness of their work as meaningful arose directly through the actions of organizational leaders or managers. Conservation stonemasons talked of the significance of carving their “banker’s mark” or mason’s signature into the stone before it was placed into a cathedral structure, knowing that the stone might be uncovered hundreds of years in the future by another mason who would recognize the work as theirs. They felt they were “part of history.” One soldier described how he realized how meaningful his work was when he reflected on his quick thinking in setting off the warning sirens in a combat situation, ensuring that no one at the camp was injured in the ensuing rocket attack. Sales assistants talked about times when they were able to help others, such as an occasion when a customer passed out in one store and the clerk was able to support her until she regained consciousness. Memorable moments such as these contain high levels of emotion and personal relevance, and thus become redolent of the symbolic meaningfulness of work.

4. Reflective

In the instances cited above, it was often only when we asked the interviewees to recount a time when they found their work meaningful that they developed a conscious awareness of the significance of these experiences. Meaningfulness was rarely experienced in the moment, but rather in retrospect and on reflection when people were able to see their completed work and make connections between their achievements and a wider sense of life meaning.

One of the entrepreneurs we interviewed talked about the time when he was switching the lights out after his company’s Christmas party and paused to reflect back over the year on what he and his employees had achieved together. Garbage collectors explained how they were able to find their work meaningful when they finished cleaning a street and stopped to look back at their work. In doing this, they reflected on how the tangible work of street sweeping contributed to the cleanliness of the environment as a whole. One academic talked about research he had done for many years that seemed fairly meaningless at the time, but 20 years later provided the technological solution for touch-screen technology. The experience of meaningfulness is therefore often a thoughtful, retrospective act rather than just a spontaneous emotional response in the moment, although people may be aware of a rush of good feelings at the time. You are unlikely to witness someone talking about how meaningful they find their job during their working day. For most of the people we spoke to, the discussions we had about meaningful work were the first time they had ever talked about these experiences.

5. Personal

Other feelings about work, such as engagement or satisfaction, tend to be just that: feelings about work. Work that is meaningful, on the other hand, is often understood by people not just in the context of their work but also in the wider context of their personal life experiences. We found that managers and even organizations actually mattered relatively little at these times. One musician described his profound sense of meaningfulness when his father attended a performance of his for the first time and finally came to appreciate and understand the musician’s work. A priest was able to find a sense of meaning in her work when she could relate the harrowing personal experiences of a member of her congregation to her own life events, and used that understanding to help and support her congregant at a time of personal tragedy. An entrepreneur’s motivation to start his own business included the desire to make his grandfather proud of him. The customary dinner held to mark the end of a soldier’s service became imbued with meaning for one soldier because it was shared with family members who were there to hear her army stories. One lawyer described how she found her work meaningful when her services were recommended by friends and family and she felt trusted and valued in both spheres of her life. A garbage collector described the time when the community’s water supply became contaminated and he was asked to work on distributing water to local residents; that was meaningful, as he could see how he was helping vulnerable neighbors.

Get Updates on Transformative Leadership

Evidence-based resources that can help you lead your team more effectively, delivered to your inbox monthly.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up

Privacy Policy

Moments of especially profound meaningfulness arose when these experiences coalesced with the sense of a job well done, one recognized and appreciated by others. One example of many came from a conservation stonemason who described how his work became most meaningful to him when the restoration of a section of the cathedral he had been working on for years was unveiled, the drapes and scaffolding withdrawn, and the work of the craftsmen celebrated. This event involved all the masons and other trades such as carpenters and glaziers, as well as the cathedral’s religious leaders, members of the public, and local dignitaries. “Everyone goes, ‘Doesn’t it look amazing?’” he said. “That’s the moment you realize you’ve saved something and ensured its future; you’ve given part of the cathedral back to the local community.”

These particular features of meaningful work suggest that the organizational task of helping people find meaning in their work is complex and profound, going far beyond the relative superficialities of satisfaction or engagement — and almost never related to one’s employer or manager.

Meaninglessness: The Seven Deadly Sins

What factors serve to destroy the fragile sense of meaningfulness that individuals find in their work? Interestingly, the factors that seem to drive a sense of meaninglessness and futility around work were very different from those associated with meaningfulness. The experiences that actively led people to ask, “Why am I doing this?” were generally a function of how people were treated by managers and leaders. Interviewees noted seven things that leaders did to create a feeling of meaninglessness (listed in order from most to least grievous).

1. Disconnect people from their values. Although individuals did not talk much about value congruence as a promoter of meaningfulness, they often talked about a disconnect between their own values and those of their employer or work group as the major cause of a sense of futility and meaninglessness. 13 This issue was raised most frequently as a source of meaninglessness in work. A recurring theme was the tension between an organizational focus on the bottom line and the individual’s focus on the quality or professionalism of work. One stonemason commented that he found the organization’s focus on cost “deeply depressing.” Academics spoke of their administrations being most interested in profits and the avoidance of litigation, instead of intellectual integrity and the provision of the best possible education. Nurses spoke despairingly of being forced to send patients home before they were ready in order to free up bed space. Lawyers talked of a focus on profits rather than on helping clients.

2. Take your employees for granted. Lack of recognition for hard work by organizational leaders was frequently cited as invoking a feeling of pointlessness. Academics talked about department heads who didn’t acknowledge their research or teaching successes; sales assistants and priests talked of bosses who did not thank them for taking on additional work. A stonemason described the way managers would not even say “good morning” to him, and lawyers described how, despite putting in extremely long hours, they were still criticized for not moving through their work quickly enough. Feeling unrecognized, unacknowledged, and unappreciated by line or senior managers was often cited in the interviews as a major reason people found their work pointless.

3. Give people pointless work to do. We found that individuals had a strong sense of what their job should involve and how they should be spending their time, and that a feeling of meaninglessness arose when they were required to perform tasks that did not fit that sense. Nurses, academics, artists, and clergy all cited bureaucratic tasks and form filling not directly related to their core purpose as a source of futility and pointlessness. Stonemasons and retail assistants cited poorly planned projects where they were left to “pick up the pieces” by senior managers. A retail assistant described the pointless task of changing the shop layout one week on instructions from the head office, only to be told to change it back again a week later.

4. Treat people unfairly. Unfairness and injustice can make work feel meaningless. Forms of unfairness ranged from distributive injustices, such as one stonemason who was told he could not have a pay raise for several years due to a shortage of money but saw his colleague being given a raise, to freelance musicians being asked to write a film score without payment. Procedural injustices included bullying and lack of opportunities for career progression.

5. Override people’s better judgment. Quite often, a sense of meaninglessness was connected with a feeling of disempowerment or disenfranchisement over how work was done. One nurse, for example, described how a senior colleague required her to perform a medical intervention that was not procedurally correct, and how she felt obliged to complete this even against her better judgment. Lawyers talked of being forced to cut corners to finish cases quickly. Stonemasons described how being forced to “hurry up” using modern tools and techniques went against their sense of historic craft practices. One priest summed up the role of the manager by saying, “People can feel empowered or disempowered by the way you run things.” When people felt they were not being listened to, that their opinions and experience did not count, or that they could not have a voice, then they were more likely to find their work meaningless.

6. Disconnect people from supportive relationships. Feelings of isolation or marginalization at work were linked with meaninglessness. This could occur through deliberate ostracism on the part of managers, or just through feeling disconnected from coworkers and teams. Most interviewees talked of the importance of camaraderie and relations with coworkers for their sense of meaningfulness. Entrepreneurs talked about their sense of loneliness and meaninglessness during the startup phase of their business, and the growing sense of meaningfulness that arose as the business developed and involved more people with whom they could share the successes. Creative artists spoke of times when they were unable to reach out to an audience through their art as times of profound meaninglessness.

7. Put people at risk of physical or emotional harm. Many jobs entail physical or emotional risks, and those taking on this kind of work generally appreciate and understand the choices they have made. However, unnecessary em> exposure to risk was associated with lost meaningfulness. Nurses cited feelings of vulnerability when left alone with aggressive patients; garbage collectors talked of avoidable accidents they had experienced at work; and soldiers described exposure to extreme weather conditions without the appropriate gear.

These seven destroyers emerged as highly damaging to an individual’s sense of his or her work as meaningful. When several of these factors were present, meaningfulness was considerably lower.

Cultivating an Ecosystem For Meaningfulness

In the 1960s, Frederick Herzberg showed that the factors that give rise to a sense of job satisfaction are not the same as those that lead to feelings of dissatisfaction. 14 It seems that something similar is true for meaningfulness. Our research shows that meaningfulness is largely something that individuals find for themselves in their work, 15 but meaninglessness is something that organizations and leaders can actively cause. Clearly, the first challenge to building a satisfied workforce is to avoid the seven deadly sins that drive up levels of meaninglessness.

Given that meaningfulness is such an intensely personal and individual experience that is interpreted by individuals in the context of their wider lives, can organizations create an environment that cultivates high levels of meaningfulness? The key to meaningful work is to create an ecosystem that encourages people to thrive. As other scholars have argued, 16 efforts to control and proscribe the meaningfulness that individuals inherently find in their work can paradoxically lead to its loss.

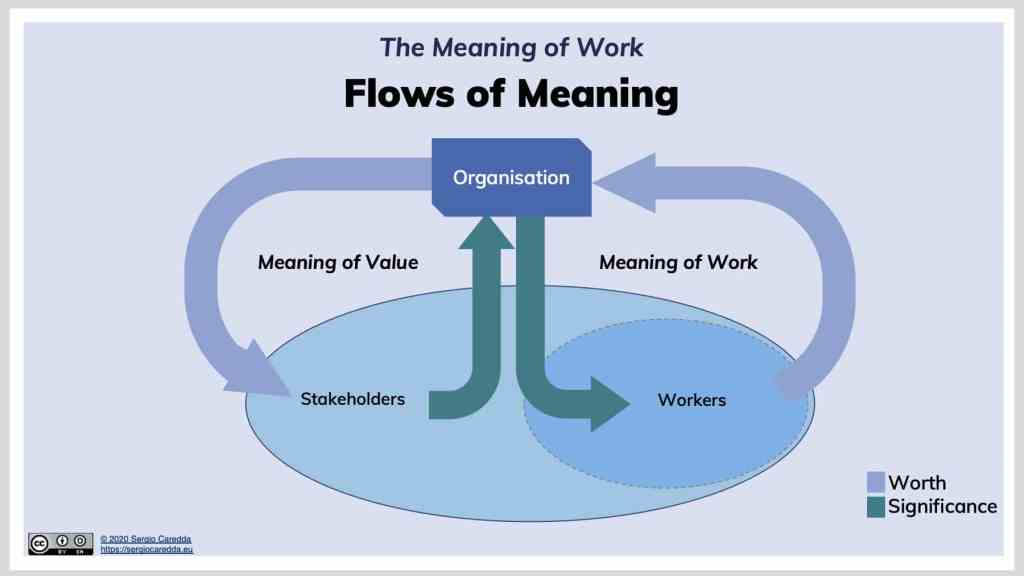

Our interviews and a wider reading of the literature on meaningfulness point to four elements that organizations can address that will help foster an integrated sense of holistic meaningfulness for individual employees. 17 (See “The Elements of a Meaningfulness Ecosystem.”)

1. Organizational Meaningfulness

At the macro level, meaningfulness is more likely to thrive when employees understand the broad purpose of the organization. 18 This purpose should be formulated in such a way that it focuses on the positive contribution of the organization to the wider society or the environment. This involves articulating the following:

- What does the organization aim to contribute? What is its “core business”?

- How does the organization aspire to go about achieving this? What values underpin its way of doing business?

This needs to be done in a genuine and thoughtful way. People are highly adept at spotting hypocrisy, like the nurses who were told their hospital put patients first but were also told to discharge people as quickly as possible. The challenge lies not only in articulating and conveying a clear message about organizational purpose, but also in not undermining meaningfulness by generating a sense of artificiality and manipulation. 19

Reaching employees in ways that make sense to them can be a challenge. A clue for addressing this comes from the garbage collectors we interviewed. One described to us how the workers used to be told by management that the waste they returned to the depot would be recycled, but this message came across as highly abstract. Then the company started putting pictures of the items that were made from recycled waste on the side of the garbage trucks. This led to a more tangible realization of what the waste was used for. 20

2. Job Meaningfulness

The vast majority of interviewees found their work meaningful, whether they were musicians, sales assistants, lawyers, or garbage collectors. Studies have shown that meaning is so important to people that they actively go about recrafting their jobs to enhance their sense of meaningfulness. 21 Often, this recrafting involves extending the impact or significance of their role for others. One example of this was sales assistants in a large retail store who listened to lonely elderly customers.

Organizations can encourage people to see their work as meaningful by demonstrating how jobs fit with the organization’s broader purpose or serve a wider, societal benefit. The priests we spoke to often explained how their ministry work in their local parishes contributed to the wider purpose of the church as a whole. In the same way, managers can be encouraged to show employees what their particular jobs contribute to the broader whole and how what they do will help others or create a lasting legacy. 22

Alongside this, we need to challenge the notion that meaningfulness can only arise from positive work experiences. Challenging, problematic, sad, or poignant 23 jobs have the potential to be richly generative of new insights and meaningfulness, and overlooking this risks upsetting the delicate balance of the meaningfulness ecosystem. Providing support to people at the end of their lives is a harrowing experience for nurses and clergy, yet they cited these times as among the most meaningful. The task for leaders is to acknowledge the problematic or negative side of some jobs and to provide appropriate support for employees doing them, yet to reveal in an honest way the benefits and broader contribution that such jobs make. 24

3. Task Meaningfulness

Given that jobs typically comprise a wide range of tasks, it stands to reason that some of these tasks will constitute a greater source of meaningfulness than others. 25 To illustrate, a priest will have responsibility for leading acts of worship, supporting sick and vulnerable individuals, developing community relations and activities, and probably a wide range of other tasks such as raising funds, managing assistants and volunteers, ensuring the upkeep of church buildings, and so on. In fact, the priests were the most hard-working group that we spoke to, with the majority working a seven-day week on a bewildering range of activities. Even much simpler jobs will involve several different tasks. One of the challenges facing organizations is to help people understand how the individual tasks they perform contribute to their job and to the organization as a whole.

When individuals described some of the sources of meaninglessness they faced in their work, they often talked about how to come to terms with the tedious, repetitive, or indeed purposeless work that is part of almost every job. For example, the stonemasons described how the first few months of their training involved learning to “square the stone,” which involves chiseling a large block of stone into a perfectly formed square with just a few millimeters of tolerance on each plane. As soon as they finished one, they had to start another, repeating this over and over until the master mason was satisfied that they had perfected the task. Only then were they allowed to work on more interesting and intricate carvings. Several described their feelings of boredom and futility; one said that he had taken 18 attempts to get the squaring of the stone correct. “It feels like you are never ever going to get better,” he recalled. Many felt like giving up at this point, fearing that stonemasonry was not for them. It was only in later years, as they looked back on this period in their working lives, that they could see the point of this detailed level of training as the first step on their path to more challenging and rewarding work.

Filling out forms, cited earlier, is another good example of meaningless work. Individuals in a wide range of occupations all reported that what they perceived as “mindless bureaucracy” sapped the meaningfulness from their work. For instance, most of the academics we spoke to were highly negative about the amount of form filling the job entailed. One said, “I was dropping spreadsheets into a huge black hole.”

Where organizations successfully managed the context within which these necessary but tedious tasks were undertaken, the tasks came to be perceived not exactly as meaningful, but equally as not meaningless. Another academic said, “I’m pretty good with tedious work, as long as it’s got a larger meaning.”

4. Interactional Meaningfulness

There is widespread agreement that people find their work meaningful in an interactional context in two ways: 26 First, when they are in contact with others who benefit from their work; and, second, in an environment of supportive interpersonal relationships. 27 As we saw earlier, negative interactional experiences — such as bullying by a manager, lack of respect or recognition, or forcing reduced contact with the beneficiaries of work — all drive up a sense of meaninglessness, since the employee receives negative cues from others about the value they place on the employee’s work. 28 The challenge here is for leaders to create a supportive, respectful, and inclusive work climate among colleagues, between employees and managers, and between organizational staff and work beneficiaries. It also involves recognizing the importance of creating space in the working day for meaningful interactions where employees are able to give and receive positive feedback, communicate a sense of shared values and belonging, and appreciate how their work has positive impacts on others.

Not surprisingly, the most striking examples of the impact of interactional meaningfulness on people came from the caring occupations included in our study: nurses and clergy. In these cases, there was very frequent contact between the individual and the direct beneficiaries of his or her work, most often in the context of supporting and healing people at times of great vulnerability in their lives. Witnessing firsthand, and hearing directly, about how their work had changed people’s lives created a work environment conducive to meaningfulness. Although prior research 29 has similarly highlighted the importance of such direct contact for enhancing work’s meaningfulness, we also found that past or future generations, or imagined future beneficiaries, could play a role. This was the case for the stonemasons who felt connected to past and future generations of masons through their bankers’ marks on the back of the stones and for the garbage collectors who could envisage how their work contributed to the living environment for future generations.

Holistic Meaningfulness

The four elements of the meaningfulness ecosystem combine to enable a state of holistic meaningfulness, where the synergistic benefits of multiple sources of meaningfulness can be realized. 30 Although it is possible for someone to describe meaningful moments in terms of any one of the subsystems, meaningfulness is enriched when more than one or all of these are present. 31 A sales assistant, for example, described how she had been working with a team on the refurbishment of her store: “We’d all been there until 2 a.m., working together moving stuff, everyone had contributed and stayed late and helped, it was a good time. We were exhausted but we still laughed and then the next morning we were all bright in our uniforms, it was a lovely feeling, just like a little family coming together. The day [the store] opened, it did bring tears to my eyes. We had a little gathering and a speech; the managers said ‘thank you’ to everybody because everyone had contributed.”

Finding work meaningful is an experience that reaches beyond the workplace and into the realm of the individual’s wider personal life. It can be a very profound, moving, and even uncomfortable experience. It arises rarely and often in unexpected ways; it gives people pause for thought — not just concerning work but what life itself is all about. In experiencing work as meaningful, we cease to be workers or employees and relate as human beings, reaching out in a bond of common humanity to others. For organizations seeking to manage meaningfulness, the ethical and moral responsibility is great, since they are bridging the gap between work and personal life.

Yet the benefits for individuals and organizations that accrue from meaningful workplaces can be immense. Organizations that succeed in this are more likely to attract, retain, and motivate the employees they need to build sustainably for the future, and to create the kind of workplaces where human beings can thrive.

About the Authors

Catherine Bailey is a professor in the department of business and management at the University of Sussex in Brighton, U.K. Adrian Madden is a senior lecturer in the department of human resources and organizational behavior at the business school of the University of Greenwich in London.

1. V.E. Frankl, “Man’s Search For Meaning” (Boston: Beacon Press, 1959).

2. W.F. Cascio, “Changes in Workers, Work, and Organizations,” vol. 12, chap. 16 in “Handbook of Psychology,” ed. W. Borman, R. Klimoski, and D. Ilgen (New York: Wiley, 2003).

3. M.G. Pratt and B.E. Ashforth, “Fostering Meaningfulness in Working and at Work,” in “Positive Organizational Scholarship,” ed. K.S. Cameron, J.E. Dutton, and R.E. Quinn (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2003).

4. C. Bailey, R. Yeoman, A. Madden, M. Thompson, and G. Kerridge, “A Narrative Evidence Synthesis of Meaningful Work: Progress and Research Agenda” (paper to be presented at the U.S. Academy of Management Conference, Anaheim, California, Aug. 5-9, 2016); and M.G. Pratt, C. Pradies, and D.A. Lepisto, “Doing Well, Doing Good, and Doing With: Organizational Practices For Effectively Cultivating Meaningful Work,” in “Purpose and Meaning in the Workplace,” ed. B.J. Dik, Z.S. Byrne, and M.F. Steger (Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2013), 173-196.

5. We have defined meaningful work as arising “when an individual perceives an authentic connection between their work and a broader transcendent life purpose beyond the self.” See C. Bailey and A. Madden, “Time Reclaimed: Temporality and the Experience of Meaningful Work,” Work, Employment, & Society (October 2015), doi: 10.1177/0950017015604100. Meaningfulness is therefore different from engagement, which is defined as a positive work-related attitude comprising vigor, dedication, and absorption. See W.B. Schaufeli, “What Is Engagement?,” in “Employee Engagement in Theory and Practice,” ed. C. Truss, K. Alfes, R. Delbridge, A. Shantz, and E. Soane (London: Routledge, 2014), 15-35.

6. K. Arnold, N. Turner, J. Barling, E.K. Kelloway, and M.C. McKee, “Transformational Leadership and Psychological Wellbeing: The Mediating Role of Meaningful Work,” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 12, no. 3 (July 2007): 193-203.

7. M. Lips-Wiersma and S. Wright, “Measuring the Meaning of Meaningful Work: Development and Validation of the Comprehensive Meaningful Work Scale,” Group & Organization Management 37, no. 5 (October 2012): 665-685.

8. B.D. Rosso, K.H. Dekas, and A. Wrzesniewski, “On the Meaning of Work: A Theoretical Integration and Review,” Research in Organizational Behavior 30 (2010): 91-127.

9. A. Maslow, “Motivation and Personality” (New York: Harper and Row, 1954).

10. H. Ersner-Hershfield, J.A. Mikels, S.J. Sullivan, and L.L. Carstensen, “Poignancy: Mixed Emotional Experience in the Face of Meaningful Endings,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 94, no. 1 (January 2008): 158-167.

11. B.S. Held, “The Tyranny of the Positive Attitude in America: Observation and Speculation,” Journal of Clinical Psychology 58, no. 9 (September 2002): 965-991.

12. J.S. Bunderson and J.A. Thompson, “The Call of the Wild: Zookeepers, Callings, and the Double-Edged Sword of Deeply Meaningful Work,” Administrative Science Quarterly 54, no.1 (March 2009): 32-57.

13. S. Cartwright and N. Holmes, “The Meaning of Work: The Challenge of Regaining Employee Engagement and Reducing Cynicism,” Human Resource Management Review 16, no. 2 (June 2006): 199-208.

14. F. Herzberg, “The Motivation-Hygiene Concept and Problems of Manpower,” Personnel Administrator 27, no. 1 (1964): 3-7.

15. M. Lips-Wiersma and L. Morris, “Discriminating Between ‘Meaningful Work’ and the ‘Management of Meaning,’” Journal of Business Ethics 88, no. 3 (September 2009): 491-511.

18. N. Chalofsky, “Meaningful Workplaces” (San Francisco: Wiley, 2010); and F.O. Walumbwa, A.L. Christensen, and M.K. Muchiri, “Transformational Leadership and Meaningful Work,” in Dik, Byrne, and Steger, “Purpose and Meaning,” 197-215.

19. J.M. Podolny, R. Khurana, and M. Hill-Popper, “Revisiting the Meaning of Leadership,” Research in Organizational Behavior 26 (2004), doi:10.1016/S0191-3085(04)26001-4.

20. Organizational theorist Marya L. Besharov highlights the challenge of managing in an organizational setting where employees have differing views over which values matter the most and points out the “dark side” of seeking to impose a unitary organizational ideology on employees. Based on our research, we take the view here that in general terms employees welcome a broad statement of organizational purpose and values that gives them the space to interpret it in a way that is meaningful for them. See M.L. Besharov, “The Relational Ecology of Identification: How Organizational Identification Emerges When Individuals Hold Divergent Values,” Academy of Management Journal 57, no. 5 (October 2014): 1485-1512.

21. A. Wrzesniewski and J.E. Dutton, “Crafting a Job: Revisioning Employees as Active Crafters of Their Work,” Academy of Management Review 26, no. 2 (April 2001): 179-201; and J.M. Berg, J.E. Dutton, and A. Wrzesniewski, “Job Crafting and Meaningful Work,” in Dik, Byrne, and Steger, “Purpose and Meaning,” 81-104.

22. B.E. Ashforth and G.E. Kreiner, “Profane or Profound? Finding Meaning in Dirty Work,” in Dik, Byrne, and Steger, “Purpose and Meaning,” 127-150.

23. Held, “Tyranny of the Positive Attitude”; and Ersner-Hershfield et al., “Poignancy: Mixed Emotional Experience.”

24. Lips-Wiersma and Morris, “Discriminating Between ‘Meaningful Work.’”

25. A. Grant, “Relational Job Design and the Motivation to Make a Prosocial Difference,” Academy of Management Review 32, no. 2 (2007): 393-417.

26. Lips-Wiersma and Wright, “Measuring the Meaning.”

27. A. Grant, “Leading With Meaning: Beneficiary Contact, Prosocial Impact, and the Performance Effects of Transformational Leadership,” Academy of Management Journal 55, no. 2 (April 2012): 458-476.

28. A. Wrzesniewski, J.E. Dutton, and G. Debebe, “Interpersonal Sensemaking and the Meaning of Work,” Research in Organizational Behavior 25 (2003): 93-135.

29. Grant, “Leading With Meaning.”

30. Lips-Wiersma and Wright, “Measuring the Meaning.”

i. Bailey and Madden, “Time Reclaimed: Temporality and the Experience.”

More Like This

Add a comment cancel reply.

You must sign in to post a comment. First time here? Sign up for a free account : Comment on articles and get access to many more articles.

Comments (55)

Aaron mccullough, harihara sudhan sundarararaj, deepanshu mangla, sandeep baranwal, helen christy, rodolfo martins, fatima andra flores felizardo, nancy ekwerike, blaze coyle, lorren cargill, bhavisha jogi, olivia davis, ruchi chaturvedi, chimbirai chimbirai, gessika sousa, imelda pedrero, hongshin yoon, gabriela ilha, muhammad rushan khan, louise turner, komal bhise, rajesh kumar c, alejandra gomez, lajuan huff, montse carrasco-gallardo, daniel solorzano, crystal wan, samantha widmer, paula barcarse, subinoy dey, hashim syed, daisuke arikura, gaurab banerjee, pearl panthaki, henrique marcondes, sakshi jain, steven meng, maricris see, jean pierre lópez bustos, chandra pandey, andrewdonovan, katie bailey, speck kevin pratt.

Essays About Work: 7 Examples and 8 Prompts

If you want to write well-researched essays about work, check out our guide of helpful essay examples and writing prompts for this topic.

Whether employed or self-employed, we all need to work to earn a living. Work could provide a source of purpose for some but also stress for many. The causes of stress could be an unmanageable workload, low pay, slow career development, an incompetent boss, and companies that do not care about your well-being. Essays about work can help us understand how to achieve a work/life balance for long-term happiness.

Work can still be a happy place to develop essential skills such as leadership and teamwork. If we adopt the right mindset, we can focus on situations we can improve and avoid stressing ourselves over situations we have no control over. We should also be free to speak up against workplace issues and abuses to defend our labor rights. Check out our essay writing topics for more.

5 Examples of Essays About Work

1. when the future of work means always looking for your next job by bruce horovitz, 2. ‘quiet quitting’ isn’t the solution for burnout by rebecca vidra, 3. the science of why we burn out and don’t have to by joe robinson , 4. how to manage your career in a vuca world by murali murthy, 5. the challenges of regulating the labor market in developing countries by gordon betcherman, 6. creating the best workplace on earth by rob goffee and gareth jones, 7. employees seek personal value and purpose at work. be prepared to deliver by jordan turner, 8 writing prompts on essays about work, 1. a dream work environment, 2. how is school preparing you for work, 3. the importance of teamwork at work, 4. a guide to find work for new graduates, 5. finding happiness at work, 6. motivating people at work, 7. advantages and disadvantages of working from home, 8. critical qualities you need to thrive at work.

“For a host of reasons—some for a higher salary, others for improved benefits, and many in search of better company culture—America’s workforce is constantly looking for its next gig.”

A perennial search for a job that fulfills your sense of purpose has been an emerging trend in the work landscape in recent years. Yet, as human resource managers scramble to minimize employee turnover, some still believe there will still be workers who can exit a company through a happy retirement. You might also be interested in these essays about unemployment .

“…[L]et’s creatively collaborate on ways to re-establish our own sense of value in our institutions while saying yes only to invitations that nourish us instead of sucking up more of our energy.”

Quiet quitting signals more profound issues underlying work, such as burnout or the bosses themselves. It is undesirable in any workplace, but to have it in school, among faculty members, spells doom as the future of the next generation is put at stake. In this essay, a teacher learns how to keep from burnout and rebuild a sense of community that drew her into the job in the first place.

“We don’t think about managing the demands that are pushing our buttons, we just keep reacting to them on autopilot on a route I call the burnout treadmill. Just keep going until the paramedics arrive.”

Studies have shown the detrimental health effects of stress on our mind, emotions and body. Yet we still willingly take on the treadmill to stress, forgetting our boundaries and wellness. It is time to normalize seeking help from our superiors to resolve burnout and refuse overtime and heavy workloads.

“As we start to emerge from the pandemic, today’s workplace demands a different kind of VUCA career growth. One that’s Versatile, Uplifting, Choice-filled and Active.”

The only thing constant in work is change. However, recent decades have witnessed greater work volatility where tech-oriented people and creative minds flourish the most. The essay provides tips for applying at work daily to survive and even thrive in the VUCA world. You might also be interested in these essays about motivation .

“Ultimately, the biggest challenge in regulating labor markets in developing countries is what to do about the hundreds of millions of workers (or even more) who are beyond the reach of formal labor market rules and social protections.”

The challenge in regulating work is balancing the interest of employees to have dignified work conditions and for employers to operate at the most reasonable cost. But in developing countries, the difficulties loom larger, with issues going beyond equal pay to universal social protection coverage and monitoring employers’ compliance.

“Suppose you want to design the best company on earth to work for. What would it be like? For three years, we’ve been investigating this question by asking hundreds of executives in surveys and in seminars all over the world to describe their ideal organization.”

If you’ve ever wondered what would make the best workplace, you’re not alone. In this essay, Jones looks at how employers can create a better workplace for employees by using surveys and interviews. The writer found that individuality and a sense of support are key to creating positive workplace environments where employees are comfortable.

“Bottom line: People seek purpose in their lives — and that includes work. The more an employer limits those things that create this sense of purpose, the less likely employees will stay at their positions.”

In this essay, Turner looks at how employees seek value in the workplace. This essay dives into how, as humans, we all need a purpose. If we can find purpose in our work, our overall happiness increases. So, a value and purpose-driven job role can create a positive and fruitful work environment for both workers and employers.

In this essay, talk about how you envision yourself as a professional in the future. You can be as creative as to describe your workplace, your position, and your colleagues’ perception of you. Next, explain why this is the line of work you dream of and what you can contribute to society through this work. Finally, add what learning programs you’ve signed up for to prepare your skills for your dream job. For more, check out our list of simple essays topics for intermediate writers .

For your essay, look deeply into how your school prepares the young generation to be competitive in the future workforce. If you want to go the extra mile, you can interview students who have graduated from your school and are now professionals. Ask them about the programs or practices in your school that they believe have helped mold them better at their current jobs.

In a workplace where colleagues compete against each other, leaders could find it challenging to cultivate a sense of cooperation and teamwork. So, find out what creative activities companies can undertake to encourage teamwork across teams and divisions. For example, regular team-building activities help strengthen professional bonds while assisting workers to recharge their minds.

Finding a job after receiving your undergraduate diploma can be full of stress, pressure, and hard work. Write an essay that handholds graduate students in drafting their resumes and preparing for an interview. You may also recommend the top job market platforms that match them with their dream work. You may also ask recruitment experts for tips on how graduates can make a positive impression in job interviews.

Creating a fun and happy workplace may seem impossible. But there has been a flurry of efforts in the corporate world to keep workers happy. Why? To make them more productive. So, for your essay, gather research on what practices companies and policy-makers should adopt to help workers find meaning in their jobs. For example, how often should salary increases occur? You may also focus on what drives people to quit jobs that raise money. If it’s not the financial package that makes them satisfied, what does? Discuss these questions with your readers for a compelling essay.

Motivation could scale up workers’ productivity, efficiency, and ambition for higher positions and a longer tenure in your company. Knowing which method of motivation best suits your employees requires direct managers to know their people and find their potential source of intrinsic motivation. For example, managers should be able to tell whether employees are having difficulties with their tasks to the point of discouragement or find the task too easy to boredom.

A handful of managers have been worried about working from home for fears of lowering productivity and discouraging collaborative work. Meanwhile, those who embrace work-from-home arrangements are beginning to see the greater value and benefits of giving employees greater flexibility on when and where to work. So first, draw up the pros and cons of working from home. You can also interview professionals working or currently working at home. Finally, provide a conclusion on whether working from home can harm work output or boost it.

Identifying critical skills at work could depend on the work applied. However, there are inherent values and behavioral competencies that recruiters demand highly from employees. List the top five qualities a professional should possess to contribute significantly to the workplace. For example, being proactive is a valuable skill because workers have the initiative to produce without waiting for the boss to prod them.

If you need help with grammar, our guide to grammar and syntax is a good start to learning more. We also recommend taking the time to improve the readability score of your essays before publishing or submitting them.

Meet Rachael, the editor at Become a Writer Today. With years of experience in the field, she is passionate about language and dedicated to producing high-quality content that engages and informs readers. When she's not editing or writing, you can find her exploring the great outdoors, finding inspiration for her next project.

View all posts

More From Forbes

The why of work: purpose and meaning really do matter.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

People are more likely to thrive when their work has clear purpose and meaning.

It’s a question all of us should ask ourselves. Why do we do what we do? In particular, why do we do the work that, for many of us, occupies most of our waking hours for our entire adult lives?

Ralph Waldo Emerson left us a quote worthy of one of those inspirational wall posters: “The purpose of life is not to be happy. It is to be useful, to be honorable, to be compassionate, to have it make some difference that you have lived and lived well.”

That thought may feel warm and fuzzy, but the question remains: Why do we do the work we do?

David and Wendy Ulrich address that and many related issues in The Why of Work: How Great Leaders Build Abundant Organizations That Win .

David Ulrich, professor of business at the University of Michigan, has authored or coauthored more than 30 books that have shaped the human resources profession and the field of leadership development. Wendy Ulrich is a psychologist, educator and writer with a passion for helping people create healthy relationships and meaning-rich lives.

I visited with this dynamic duo to explore their thinking on issues affecting engagement, productivity, and—yes—purpose and meaning in the workplace.

Rodger Dean Duncan: In the context of meaning in the workplace, how do you define abundance?

David and Wendy Ulrich

David Ulrich: Abundance is to have a fullness (e.g., an abundant harvest) or to live life to its fullest (e.g., an abundant life).

An abundant organization enables its employees to be completely fulfilled by finding meaning and purpose from their work experience. This meaning enables employees to have personal hope for the future and create value for customers and investors. When we ask people how the feel about their work, we can quickly get a sense of how work helps them fulfill the things that matter most in their lives.

Duncan: You point out that meaning and abundance are more about what we do with what we have than about what we have to begin with or what we accumulate. How can a leader persuade people to adopt that viewpoint and to “operationalize” it in the workplace?

Wendy Ulrich: Clearly this won’t fly if a leader is trying to talk people into ignoring bad working conditions when something could be done to change them. But I learned long ago with therapy clients that their misery often had less to do with their circumstances and more to do with what they told themselves those circumstances meant about them. (“This means I’ll never be happy …. my future is hopeless ... people don’t like me ... I’ll never succeed.”) Fortunately, even when we cannot change our circumstances, we do control what we tell ourselves those circumstances mean about us. Checking out what is real, changing the story, seeing a different perspective, or getting creative can turn a problem into an opportunity.

Duncan: How can an organization institutionalize, not merely individualize, abundance and meaning in the workplace?

D. Ulrich: The concept of abundant organizations draws on many diverse literatures related to the employee experience at work: positive psychology, high performing teams, culture, commitment, learning, civility, growth mindset. By distilling these literatures, we identified seven principles of the abundant organization (identity, purpose, relationships/teamwork, positive work environment, personalizing work, resilience/growth, and delight/civility). These principles are institutionalized into organizations by designing and delivering HR practices around people, performance, information, and work that enable organizations to create a personality that outlasts any single individual.

Duncan: You say leaders are meaning makers. In terms of observable behaviors, what does that look like?

W. Ulrich: People find meaning when they see a clear connection between what they highly value and what they spend time doing. That connection is not always obvious, however. Leaders are in a great position to articulate the values a company is trying to enact and to shape the story of how today’s work connects with those values. This means sharing stories of how the company is making a difference for good in the lives of real people, including customers, employees, and communities.

Leaders operationalize that by formally and informally sharing those stories, speaking passionately about what the company stands for and sharing personal lessons learned in that process. Leaders can involve employees in both articulating those values and creating plans to act on them. One way to make those stories come alive is to bring in people who have been helped by the company’s products or services and letting them share their stories. We are usually pretty good at sharing financial data. Often more motivating to employees are stories about human impact.

Open the door to employee engagement.

Duncan: As the story goes, people feel differently about the meaning of their work if they see themselves as bricklayers rather than as building a cathedral to God. What can leaders (and individuals) do to make work more about cathedral-building?

D. Ulrich: There is an old fable of the three bricklayers all working on the same wall. Someone asked the bricklayers, “What you are doing?” The first said “I am laying bricks”; the second bricklayer replied, “I am building a wall”; and the third answered, “I am building a great cathedral for God.” The third had a vision of how the daily tasks of laying bricks fit into a broader, more meaningful purpose. Likewise, employees who envision the outcomes of their daily routines find more meaning from doing them. I am not just presenting a lecture as I teach, but preparing the next generation of business leaders.

Duncan: What advice do you give workers who don’t have a charismatic leader who pushes an abundance agenda? What can they do to flourish?

D. Ulrich: Martin Seligman’s exceptional book Flourish suggests that employees can acquire a most positive outlook on their work by having Positive emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishments (what he calls PERMA). When employees take personal accountability for creating these attributes (which relate to our seven dimensions of abundance) they do not depend on the leader, but themselves for their work experience. Leaders matter to employee experience, but employee responsibility for the experience matters more. Children mature when they no longer depend on parents to provide all their needs. Likewise, mature employees become agents for their own development.

Duncan: In the spirit of the Olympic athlete in Chariots of Fire , how can a person find abundant forms of accomplishment? (Insight, Achievement, Connection, Empowerment)

D. Ulrich: Defining what matters most or what success looks like is an easy question that is not simple to answer. Success varies by person and over time for any individual person. Olympic athletes like Eric Liddell of Chariots of Fire fame, started with success in his achievements (I can run fast enough to win the medal), but then morphed to insight (I run to find the pleasure God granted me), and ultimately to empower others (I can help others run to find their purpose). Likewise, an employee can continually ask “what do I want” and “how do I define success.” These reflection questions help s take personal accountability for their work and personal lives.

Duncan: Gallup research shows that employees who have a best friend at work are seven times more likely to be highly engaged at work than those who don’t. What can be done to create a workplace that fosters those kinds of relationships?

W. Ulrich: Plenty!

- Leaders can model healthy relationships at work.

- They can encourage people to get to know each other by making time, space, and resources available for them to do so.

- They can try to catch people in the act of being nice, thanking and encouraging them.

- They can set up ways to teach and coach people in the skills of good relating, such as good listening, being curious about others, apologizing effectively, controlling anger, and letting go of slights—some of the specific skills people can learn and practice that will help them enjoy others and be easier to like.

People with the skills to create and maintain friendship will likely experience less stress at home, increased effectiveness with customers, and improved communications throughout the organization.

Duncan: What role does personal humility play in a leader’s ability to inspire others and create meaning in the workplace?

W. Ulrich: Recent work by Dacher Keltner at UC Berkeley on the dynamics of power is fascinating in this regard. He found that people are most likely to rise to power when they have qualities like kindness, good listening, concern for the greater good, enthusiasm, focus, high empathy, and humility. He also found that once people are in power positions, those qualities too often take a back seat to self-entitlement, indifference to the plight of others, negative interruptions in conversation, and ignoring even basic politeness.

When a leader manages to hold on to his or her humanity and humility even when in the power seat, modeling the highest ideals we have for ourselves as human beings, others want to join that team. Humility is at the heart of a growth mindset that encourages and models learning instead of defensiveness in the face of setbacks, paving the way for creativity and resilience.

Duncan: Conflict, even if rare, is inevitable in most any work setting. What have you seen as best practices in addressing conflict so the “why” of work is appropriately reinforced?

W. Ulrich: Conflict is not only inevitable, it is valuable, bringing problems to light and different viewpoints to bear on problems. But conflict can also be destructive if not handled with fairness, respect, and good will.

When there’s a problem it’s almost always best to bring it up in a straightforward way directly with the person involved. If we are contemptuous, critical, or cruel we can expect to get defensiveness and anger in return. If we are calm, curious, and compassionate as we try to both explain our point of view and listen to others, conflict can help us get to better outcomes for all. It’s amazing how healing it can be to simply feel genuinely heard and cared about and to receive a respectful apology. Most people will listen if they don’t feel threatened or attacked.

Duncan: How can people find intrinsic value in their work if it’s not readily apparent to them?

W. Ulrich: Take a careful look at your deepest values for how to treat other people (especially in the face of disagreement), what matters most in life, what problems you like to solve or want to solve, or what personal strengths are most meaningful to you to contribute to others. Then actively look for ways to live those values, even in small ways, in the everyday work you do.

Living with meaning and purpose is not easy. It may not make us happy in the moment. It requires self-reflection, effort, getting our hands dirty, and struggling with problems that can make us feel frustrated and inadequate. But when we connect with people, remember humor and playfulness, practice creativity and resilience, and go into work situations with a plan, we’ll find ample opportunities to practice the values and skills that get us closer to what we want our lives to stand for. That’s the intrinsic value of our work.

Duncan: How should leaders serve as models for meaning in the workplace?

D. Ulrich: When we ask workshop participants to identify leaders who shaped their lives, everyone can quickly name someone. These leaders generally model the principles of abundance in their personal lives and work to instill them in others. Leaders who are meaning-makers are acutely aware of how their good intentions need to show up in good behaviors; how their daily interactions need to reflect their personal values; and how their job as a leader is not just to be personally authentic, but to help others develop their authenticity.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Philosophical Approaches to Work and Labor

Work is a subject with a long philosophical pedigree. Some of the most influential philosophical systems devote considerable attention to questions concerning who should work, how they should work, and why. For example, in the ideally just city outlined in the Republic , Plato proposed a system of labor specialization, according to which individuals are assigned to one of three economic strata, based on their inborn abilities: the laboring or mercantile class, a class of auxiliaries charged with keeping the peace and defending the city, or the ruling class of ‘philosopher-kings’. Such a division of labor, Plato argued, will ensure that the tasks essential to the city’s flourishing will be performed by those most capable of performing them.

In proposing that a just society must concern itself with how work is performed and by whom, Plato acknowledged the centrality of work to social and personal life. Indeed, most adults spend a significant time engaged in work, and many contemporary societies are arguably “employment-centred” (Gorz 2010). In such societies, work is the primary source of income and is ‘normative’ in the sociological sense, i.e., work is expected to be a central feature of day-to-day life, at least for adults.

Arguably then, no phenomenon exerts a greater influence on the quality and conditions of human life than work. Work thus deserves the same level of philosophical scrutiny as other phenomena central to economic activity (for example, markets or property) or collective life (the family, for instance).

The history of philosophy contains an array of divergent perspectives concerning the place of work in human life (Applebaum 1992, Schaff 2001, Budd 2011, Lis and Soly 2012, Komlosy 2018). Traditional Confucian thought, for instance, embraces hard work, perseverance, the maintenance of professional relations, and identification with organizational values. The ancient Mediterranean tradition, exemplified by Plato and Aristotle, admired craft and knowledge-driven productive activity while also espousing the necessity of leisure and freedom for a virtuous life. The Christian tradition contains several different views of work, including that work is toil for human sin, that work should be a calling or vocation by which one glorifies God or carries out God’s will, and that work is an arena in which to manifest one’s status as elect in the eyes of God (the ‘Protestant work ethic’). The onset of the Industrial Revolution and the adverse working conditions of industrial labor sparked renewed philosophical interest in work, most prominently in Marxist critiques of work and labor that predict the alienation of workers under modern capitalism and the emergence of a classless society in which work is minimized or equitably distributed.

Philosophical attention to work and labor seems to increase when work arrangements or values appear to be in flux. For example, recent years have witnessed an increase in philosophical research on work, driven at least in part by the perception that is in ‘crisis’: Economic inequality in employment-centred societies continues to rise, technological automation seems poised to eliminate jobs and to augur an era of persistent high unemployment, and dissatisfaction about the quality or meaningfulness of work in present day jobs appears to be increasing (Schwartz 2015, Livingston 2016, Graeber 2018, Danaher 2019). Many scholars now openly question whether work should be treated as a ‘given’ in modern societies (Weeks 2011).

This entry will attempt to bring systematicity to the extant philosophical literature on work by examining the central conceptual, ethical, and political questions in the philosophy of work and labor (Appiah 2021).

1. Conceptual Distinctions: Work, Labor, Employment, Leisure

2.1 the goods of work, 2.2 opposition to work and work-centred culture, 3.1 distributive justice, 3.2 contributive and productive justice, 3.3 equality and workplace governance, 3.4 gender, care, and emotional labor, 4. work and its future, 5. conclusion, other internet resources, related entries.

It is not difficult to enumerate examples of work. Hence, Samuel Clark:

by work I mean the familiar things we do in fields, factories, offices, schools, shops, building sites, call centres, homes, and so on, to make a life and a living. Examples of work in our commercial society include driving a taxi, selling washing machines, managing a group of software developers, running a till in a supermarket, attaching screens to smartphones on an assembly line, fielding customer complaints in a call centre, and teaching in a school (Clark 2017: 62).

Some contemporary commentators have observed that human life is increasingly understood in work-like terms: parenthood is often described as a job, those with romantic difficulties are invited to ‘work on’ their relationships, those suffering from the deaths of others are advised to undertake ‘grief work,’ and what was once exercise is now ‘working out’ (Malesic 2017). The diversity of undertakings we designate as ‘work’, and the apparent dissimilarities among them, have led some philosophers to conclude that work resists any definition (Muirhead 2007: 4, Svendsen 2015) or is at best a loose concept in which different instances of work share a ‘family resemblance’ (Pence 2001: 96–97).

The porousness of the notion of work notwithstanding, some progress in defining work seems possible by first considering the variety of ways in which work is organized. For one, although many contemporary discussions of work focus primarily on employment , not all work takes the form of employment. It is therefore important not to assimilate work to employment, because not every philosophically interesting claim that is true of employment is true of work as such, and vice versa. In an employment relationship, an individual worker sells their labor to another in exchange for compensation (usually money), with the purchaser of their labor serving as a kind of intermediary between the worker and those who ultimately enjoy the goods that the worker helps to produce (consumers). The intermediary, the employer , typically serves to manage (or appoints those who manage) the hired workers — the employees—, setting most of the terms of what goods are thereby to be produced, how the process of production will be organized, etc. Such an arrangement is what we typically understand as having a job .

But a worker can produce goods without their production being mediated in this way. In some cases, a worker is a proprietor , someone who owns the enterprise as well as participating in the production of the goods produced by that enterprise (for example, a restaurant owner who is also its head chef). This arrangement may also be termed self-employment , and differs from arrangements in which proprietors are not workers in the enterprise but merely capitalize it or invest in it. And some proprietors are also employers, that is, they hire other workers to contribute their labor to the process of production. Arguably, entrepreneurship or self-employment, rather than having a job, has been the predominant form of work throughout human history, and it continues to be prevalent. Over half of all workers are self-employed in parts of the world such as Africa and South Asia, and the number of self-employed individuals has been rising in many regions of the globe (International Labor Organization 2019). In contrast, jobs — more or less permanent employment relationships — are more a byproduct of industrial modernity than we realise (Suzman 2021).

Employees and proprietors are most often in a transactional relationship with consumers; they produce goods that consumers buy using their income. But this need not be the case. Physicians at a ‘free clinic’ are not paid by their patients but by a government agency, charity, etc. Nevertheless, such employees expect to earn income from their work from some source. But some instances of work go unpaid or uncompensated altogether. Slaves work, as do prisoners in some cases, but their work is often not compensated. So too for those who volunteer for charities or who provide unpaid care work , attending to the needs of children, the aged, or the ill.

Thus, work need not involve working for others, nor need it be materially compensated. These observations are useful inasmuch as they indicate that certain conditions we might presume to be essential to work (being employed, being monetarily compensated) are not in fact essential to it. Still, these observations only inform as to what work is not. Can we say more exactly what work is ?

Part of the difficulty in defining work is that whether a person’s actions constitute work seems to depend both on how her actions shape the world as well on the person’s attitudes concerning those actions. On the one hand, the activity of work is causal in that it modifies the world in some non-accidental way. As Bertrand Russell (1932) remarked, “work is of two kinds: first, altering the position of matter at or near the earth’s surface relatively to other such matter; second, telling other people to do so.” But work involves altering the world in presumptively worthwhile ways. In this respect, work is closely tied to the production of what Raymond Geuss (2021:5) has called ‘objective’ value, value residing in “external” products that can be “measured and valued independently of anything one might know about the process through which that product came to be or the people who made it.” By working, we generate goods (material objects but also experiences, states of mind, etc.) that others can value and enjoy in their own right. In most cases of work (for example, when employed), a person is compensated not for the performance of labor as such but because their labor contributes to the production of goods that have such ‘objective’ value. Note, however, that although work involves producing what others can enjoy or consume, sometimes the objective value resulting from work is not in fact enjoyed by others or by anyone at all. A self-sufficient farmer works by producing food solely for their own use, in which case the worker (rather than others) ends up consuming the objective value of their work. Likewise, the farmer who works to produce vegetables for market that ultimately go unsold has produced something whose objective value goes unconsumed.

Geuss has suggested a further characteristic of work, that it is “necessary” for individuals and for “societies as a whole” (2021:18). Given current and historical patterns of human life, work has been necessary to meet human needs. However, if some prognostications about automation and artificial intelligence prove true (see section 4 on ‘The Future of Work’), then the scarcity that has defined the human condition up to now may be eliminated, obviating the necessity of work at both the individual and societal level. Moreover, as Geuss observes, some work aims to produce goods that answer to human wants rather than human needs or necessities (that is, to produce luxuries), and some individuals manage to escape the necessity of work thanks to their antecedent wealth.

Still, work appears to have as one of its essential features that it be an activity that increases the objective (or perhaps intersubjective) value in the world. Some human activities are therefore arguably not work because they generate value for the actor instead of for others. For instance, work stands in contrast to leisure . Leisure is not simply idleness or the absence of work, nor is it the absence of activity altogether (Pieper 1952, Walzer 1983: 184–87, Adorno 2001, Haney and Kline 2010). When at leisure, individuals engage in activities that produce goods for their own enjoyment largely indifferent to the objective value that these activities might generate for others. The goods resulting from a person’s leisure are bound up with the fact that she generates them through her activity. We cannot hire others to sunbathe for us or enjoy a musical performance for us because the value of such leisure activities is contingent upon our performing the activities. Leisure thus produces subjective value that we ‘make’ for ourselves, value that (unlike the objective value generated from work) cannot be transferred to or exchanged with others. It might also be possible to create the objective value associated with working despite being at leisure. A professional athlete, for instance, might be motivated to play her sport as a form of leisure but produce (and be monetarily compensated for the production of) objective value for others (spectators who enjoy the sport). Perhaps such examples are instances of work and leisure or working by way of leisure.

Some accounts of work emphasize not the nature of the value work produces but the individual’s attitudes concerning work. For instance, many definitions of work emphasize that work is experienced as exertion or strain (Budd 2011:2, Veltman 2016:24–25, Geuss 2021: 9–13). Work, on this view, is inevitably laborious. No doubt work is often strenuous. But defining work in this way seems to rule out work that is sufficiently pleasurable to the worker as to hardly feel like a burden. An actor may so enjoy performing that it hardly feels like a strain at all. Nevertheless, the performance is work inasmuch as the actor must deliberately orient their activities to realize the objective value the performance may have for others. Her acting will not succeed in producing this objective value unless she is guided by a concern to produce the value by recalling and delivering her lines, etc. In fact, the actor may find performing pleasurable rather than a burden because she takes great satisfaction in producing this objective value for others. Other work involves little exertion of strain because it is nearly entirely passive; those who are paid subjects in medical research are compensated less for their active contribution to the research effort but simply “to endure” the investigative process and submit to the wills of others (Malmqvist 2019). Still, the research subject must also be deliberate in their participation, making sure to abide by protocols that ensure the validity of the research. Examples such as these suggest that a neglected dimension of work is that, in working, we are paradigmatically guided by the wills of others, for we are aiming in our work activities to generate goods that others could enjoy.

2. The Value of Work

The proposed definition of work as the deliberate attempt to produce goods that others can enjoy or consume indicates where work’s value to those besides the worker resides. And the value that work has to others need not be narrowly defined in terms of specific individuals enjoying or consuming the goods we produce. Within some religious traditions, work is way to serve God and or one’s community.

But these considerations do not shed much light on the first-personal value of work: What value does one’s work have to workers? How do we benefit when we produce goods that others could enjoy?

On perhaps the narrowest conception of work’s value, it only has exchange value. On this conception, work’s value is measured purely in terms of the material goods it generates for the worker, either in monetary terms or in terms of work’s products (growing one’s own vegetables, for instance). To view work as having exchange value is to see its value as wholly extrinsic; there is no value to work as such, only value to be gained from what one’s work concretely produces. If work only has exchange value, then work is solely a cost or a burden, never worth doing for its own sake. Echoing the Biblical tale of humanity’s fall, this conception of work’s value casts it as a curse foisted upon us due to human limitations or inadequacies.