Was the Civil War necessary? A thought 150 years later

Share story.

Was the Civil War unnecessary? Contributor Doug Bandow of the Cato Institute asks this in a column posted on Sept. 19 at Forbes.com . Sept. 19 was a couple of days after the 151 th anniversary of the bloodiest battle in U.S. history, at Antietam.

Bandow quotes North Carolina historian David Goldfield, who writes in “America Aflame: How the Civil War Created a Nation” that slavery existed in a number of nations, but all of them except the United States and Haiti ended it peacefully. Part of the reason, he writes, is that people in those countries didn’t moralize the question as much as the Americans, who had just gone through a religious revival. Other countries treated it more as a practical problem to be solved.

I recently read a book that made the same point: Thomas Fleming’s “A Disease of the Public Mind: A New Understanding of Why We Fought the Civil War.” Fleming argues that each side had a “disease of the mind” that made it unnecessarily intransigent. For the South, the “disease” was fear of a race war, and belief that that’s what the Northern abolitionists really wanted. For the North the “disease” was the thinking of the abolitionists, who cultivated hatred of “the Slave Power” and willingness to fight it to the death.

Fleming’s argument is that there was a peaceful way out: that slaveowners could be compensated and the slaves released. That was the way it was done in some of the Caribbean colonies, apparently. You can argue that that way was wrong, because slave owners didn’t deserve any payment, it was the slaves who deserved payment, and morally you’d make a lot of sense. But paying the slaveowners, he argues, could have prevented 600,000 people from dying in the war.

Most Read Opinion Stories

- When it comes to math, maybe the kids aren't the problem

- School truancy crisis means more than missed classes VIEW

- Zero traffic deaths by 2030? Put more emphasis on law enforcement

- Bailed out Alaska Airlines executives are raking in big bonuses

- Keep lights on as Washington transitions to clean power

It’s a thing to think about. We tend to present the Civil War as a simple contest between right and wrong, and we put ourselves on the side of right. And I believe that if they were going to have a fight, it was best that the Union won. Still—did they have to have a fight?

I have my own bit to add to this. I have been reading Civil War newspapers from Washington Territory as part of a project for the Museum of History and Industry. The Civil War wasn’t fought here, but the political arguments were made here between Republicans and Democrats of various stripes (mostly not secessionists) and you can get a feeling for both sides. And the feeling I get is that the Republican side —Lincoln’s side — was the more shrill.

I recall reading one newspaper editor at war’s end calling for Jeff Davis, Robert E. Lee and all high Confederate army officers to be hanged. The pro-Lincoln side was loose with the words, “treason” and “traitor.”Lincoln wanted to be magnanimous toward the South, but many on his side didn’t. The Democrat papers here were more openly racist, in an off-hand, totally not-worried way that is a bit shocking to modern sensibilities, but I didn’t catch them talking about stringing people up.

10 Facts: What Everyone Should Know About the Civil War

Fact #1: The Civil War was fought between the Northern and the Southern states from 1861-1865.

The American Civil War was fought between the United States of America and the Confederate States of America, a collection of eleven southern states that left the Union in 1860 and 1861. The conflict began primarily as a result of the long-standing disagreement over the institution of slavery. On February 9, 1861, Jefferson Davis , a former U.S. Senator and Secretary of War, was elected President of the Confederate States of America by the members of the Confederate constitutional convention. After four bloody years of conflict, the United States defeated the Confederate States. In the end, the states that were in rebellion were readmitted to the United States, and the institution of slavery was abolished nation-wide.

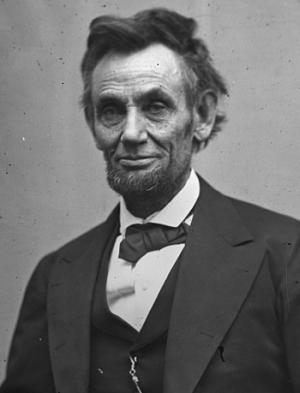

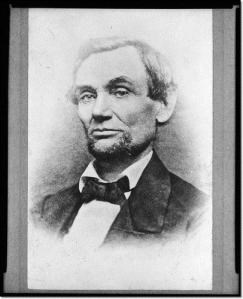

Fact #2: Abraham Lincoln was the President of the United States during the Civil War.

Abraham Lincoln grew up in a log cabin in Kentucky. He worked as a shopkeeper and a lawyer before entering politics in the 1840s. Alarmed by his anti-slavery stance, seven southern states seceded soon after he was elected president in 1860—with four more states to soon follow. Lincoln declared that he would do everything necessary to keep the United States united as one country. He refused to recognize the southern states as an independent nation and the Civil War erupted in the spring of 1861. On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation , which freed the slaves in the areas of the country that "shall then be in rebellion against the United States." The Emancipation Proclamation laid the groundwork for the eventual freedom of slaves across the country. Lincoln won re-election in 1864 against opponents who wanted to sign a peace treaty with the southern states. On April 14, 1865, Lincoln was shot by assassin John Wilkes Booth, a southern sympathizer. Abraham Lincoln died at 7:22 am the next morning.

Fact #3: The issues of slavery and central power divided the United States.

Slavery was concentrated mainly in the southern states by the mid-19th century, where slaves were used as farm laborers, artisans, and house servants. Chattel slavery formed the backbone of the largely agrarian southern economy. In the northern states, industry largely drove the economy. Many people in the north and the south believed that slavery was immoral and wrong, yet the institution remained, which created a large chasm on the political and social landscape. Southerners felt threatened by the pressure of northern politicians and “abolitionists,” who included the zealot John Brown , and claimed that the federal government had no power to end slavery, impose certain taxes, force infrastructure improvements, or influence western expansion against the wishes of the state governments. While some northerners felt that southern politicians wielded too much power in the House and the Senate and that they would never be appeased. Still, from the earliest days of the United States through the antebellum years, politicians on both sides of the major issues attempted to find a compromise that would avoid the splitting of the country, and ultimately avert a war. The Missouri Compromise , the Compromise of 1850 , the Kansas-Nebraska Act , and many others, all failed to steer the country away from secession and war. In the end, politicians on both sides of the aisle dug in their heels. Eleven states left the United States in the following order and formed the Confederate States of America: South Carolina , Mississippi , Florida, Alabama, Georgia , Louisiana, Texas , Virginia , Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

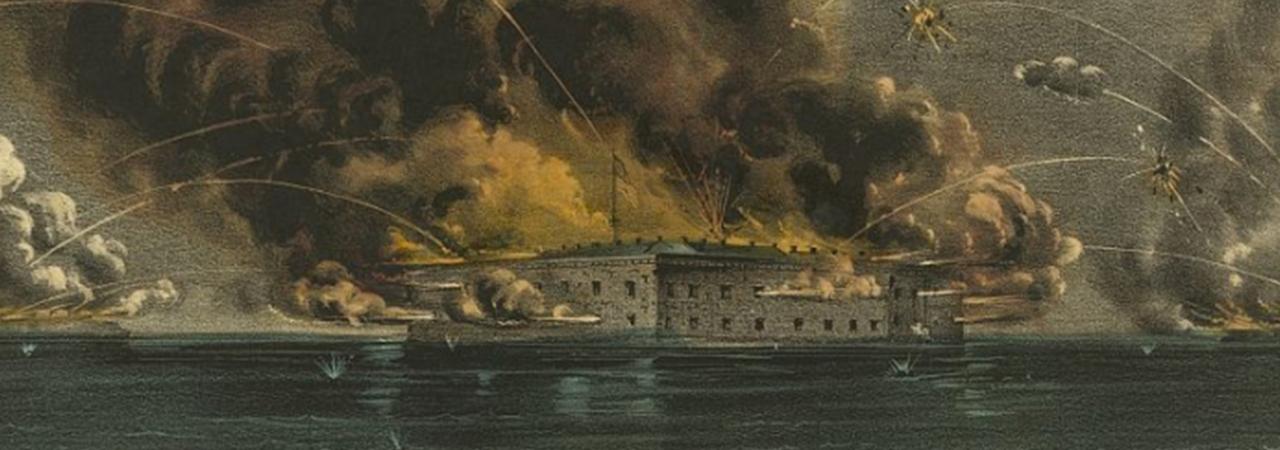

Fact #4: The Civil War began when Southern troops bombarded Fort Sumter, South Carolina.

When the southern states seceded from the Union, war was still not a certainty. Federal forts, barracks, and naval shipyards dotted the southern landscape. Many Regular Army officers clung tenaciously to their posts, rather than surrender their facilities to the growing southern military presence. President Lincoln attempted to resupply these garrisons with food and provisions by sea. The Confederacy learned of Lincoln’s plans and demanded that the forts surrender under threat of force. When the U.S. soldiers refused, South Carolinians bombarded Fort Sumter in the center of Charleston harbor. After a 34-hour battle, the soldiers inside the fort surrendered to the Confederates. Legions of men from north and south rushed to their respective flags in the ensuing patriotic fervor.

Fact #5: The North had more men and war materials than the South.

At the beginning of the Civil War, 22 million people lived in the North and 9 million people (nearly 4 million of whom were slaves) lived in the South. The North also had more money, more factories, more horses, more railroads, and more farmland. On paper, these advantages made the United States much more powerful than the Confederate States. However, the Confederates were fighting defensively on territory that they knew well. They also had the advantage of the sheer size of the Southern Confederacy. Which meant that the northern armies would have to capture and hold vast quantities of land across the south. Still, too, the Confederacy maintained some of the best ports in North America—including New Orleans, Charleston, Mobile, Norfolk, and Wilmington. Thus, the Confederacy was able to mount a stubborn resistance.

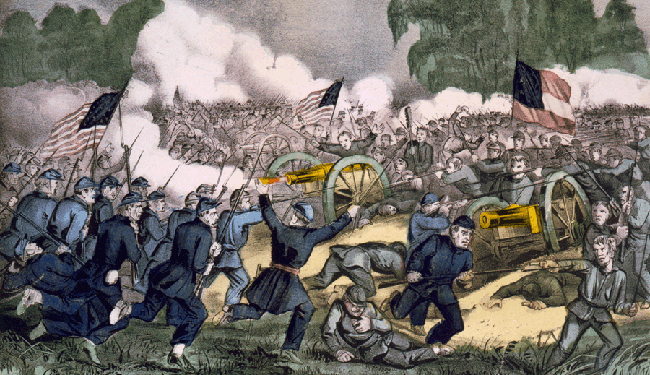

Fact #6: The bloodiest battle of the Civil War was the Battle of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

The Civil War devastated the Confederate states. The presence of vast armies throughout the countryside meant that livestock, crops, and other staples were consumed very quickly. In an effort to gather fresh supplies and relieve the pressure on the Confederate garrison at Vicksburg, Mississippi, Confederate General Robert E. Lee launched a daring invasion of the North in the summer of 1863. He was defeated by Union General George G. Meade in a three-day battle near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania that left nearly 51,000 men killed, wounded, or missing in action. While Lee's men were able to gather the vital supplies, they did little to draw Union forces away from Vicksburg, which fell to Federal troops on July 4, 1863. Many historians mark the twin Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg , Mississippi, as the “turning point” in the Civil War. In November of 1863, President Lincoln traveled to the small Pennsylvania town and delivered the Gettysburg Address, which expressed firm commitment to preserving the Union and became one of the most iconic speeches in American history.

Fact #7: Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee did not meet on the field of battle until May of 1864.

Arguably the two most famous military personalities to emerge from the American Civil War were Ohio born Ulysses S. Grant , and Virginia born Robert E. Lee . The two men had very little in common. Lee was from a well respected First Family of Virginia, with ties to the Continental Army and the founding fathers of the nation. While Grant was from a middle-class family with no martial or family political ties. Both men graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point and served in the old army as well as the Mexican-American War. Lee was offered command of the federal army amassing in Washington, in 1861, but he declined the command and threw his hat in with the Confederacy. Lee's early war career got off to a rocky start, but he found his stride in June of 1862 after he assumed command of what he dubbed the Army of Northern Virginia. Grant, on the other hand, found early success in the war but was haunted by rumors of alcoholism. By 1863, the two men were by far the best generals on their respective sides. In March of 1864, Grant was promoted to lieutenant general and brought to the Eastern Theater of the war, where he and Lee engaged in a relentless campaign from May of 1864 to Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House eleven months later.

Fact #8: The North won the Civil War.

After four years of conflict, the major Confederate armies surrendered to the United States in April of 1865 at Appomattox Court House and Bennett Place . The war bankrupted much of the South, left its roads, farms, and factories in ruins, and all but wiped out an entire generation of men who wore the blue and the gray. More than 620,000 men died in the Civil War, more than any other war in American history. The southern states were occupied by Union soldiers, rebuilt, and gradually re-admitted to the United States over the course of twenty difficult years known as the Reconstruction Era.

Fact #9: After the war was over, the Constitution was amended to free the slaves, to assure “equal protection under the law” for American citizens, and to grant black men the right to vote.

During the war, Abraham Lincoln freed some slaves and allowed freedmen to join the Union Army as the United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.). It was clear to many that it was only a matter of time before slavery would be fully abolished. As the war drew to a close, but before the southern states were re-admitted to the United States, the northern states added the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the Constitution. The amendments are also known as the "Civil War Amendments." The 13th Amendment abolished slavery in the United States, the 14th Amendment guaranteed that citizens would receive “equal protection under the law,” and the 15th Amendment granted black men the right to vote. The 14th Amendment has played an ongoing role in American society as different groups of citizens continue to lobby for equal treatment by the government.

Fact #10: Many Civil War battlefields are threatened by development.

The United States government has identified 384 battles that had a significant impact on the larger war. Many of these battlefields have been developed—turned into shopping malls, pizza parlors, housing developments, etc.—and many more are threatened by development. Since the end of the Civil War, veterans and other citizens have struggled to preserve the fields on which Americans fought and died. The American Battlefield Trust and its partners have preserved tens of thousands of acres of battlefield land.

Learn More: Civil War Animated Map

Death by Fire

Silent Witness

Augmented Reality: Preserving Lost Stories

Related battles, explore the american civil war.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 20, 2023 | Original: October 15, 2009

The Civil War in the United States began in 1861, after decades of simmering tensions between northern and southern states over slavery, states’ rights and westward expansion. The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 caused seven southern states to secede and form the Confederate States of America; four more states soon joined them. The War Between the States, as the Civil War was also known, ended in Confederate surrender in 1865. The conflict was the costliest and deadliest war ever fought on American soil, with some 620,000 of 2.4 million soldiers killed, millions more injured and much of the South left in ruin.

Causes of the Civil War

In the mid-19th century, while the United States was experiencing an era of tremendous growth, a fundamental economic difference existed between the country’s northern and southern regions.

In the North, manufacturing and industry was well established, and agriculture was mostly limited to small-scale farms, while the South’s economy was based on a system of large-scale farming that depended on the labor of Black enslaved people to grow certain crops, especially cotton and tobacco.

Growing abolitionist sentiment in the North after the 1830s and northern opposition to slavery’s extension into the new western territories led many southerners to fear that the existence of slavery in America —and thus the backbone of their economy—was in danger.

Did you know? Confederate General Thomas Jonathan Jackson earned his famous nickname, "Stonewall," from his steadfast defensive efforts in the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas). At Chancellorsville, Jackson was shot by one of his own men, who mistook him for Union cavalry. His arm was amputated, and he died from pneumonia eight days later.

In 1854, the U.S. Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act , which essentially opened all new territories to slavery by asserting the rule of popular sovereignty over congressional edict. Pro- and anti-slavery forces struggled violently in “ Bleeding Kansas ,” while opposition to the act in the North led to the formation of the Republican Party , a new political entity based on the principle of opposing slavery’s extension into the western territories. After the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Dred Scott case (1857) confirmed the legality of slavery in the territories, the abolitionist John Brown’s raid at Harper’s Ferry in 1859 convinced more and more southerners that their northern neighbors were bent on the destruction of the “peculiar institution” that sustained them. Abraham Lincoln ’s election in November 1860 was the final straw, and within three months seven southern states—South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas—had seceded from the United States.

Outbreak of the Civil War (1861)

Even as Lincoln took office in March 1861, Confederate forces threatened the federal-held Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. On April 12, after Lincoln ordered a fleet to resupply Sumter, Confederate artillery fired the first shots of the Civil War. Sumter’s commander, Major Robert Anderson, surrendered after less than two days of bombardment, leaving the fort in the hands of Confederate forces under Pierre G.T. Beauregard. Four more southern states—Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina and Tennessee—joined the Confederacy after Fort Sumter. Border slave states like Missouri, Kentucky and Maryland did not secede, but there was much Confederate sympathy among their citizens.

Though on the surface the Civil War may have seemed a lopsided conflict, with the 23 states of the Union enjoying an enormous advantage in population, manufacturing (including arms production) and railroad construction, the Confederates had a strong military tradition, along with some of the best soldiers and commanders in the nation. They also had a cause they believed in: preserving their long-held traditions and institutions, chief among these being slavery.

In the First Battle of Bull Run (known in the South as First Manassas) on July 21, 1861, 35,000 Confederate soldiers under the command of Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson forced a greater number of Union forces (or Federals) to retreat towards Washington, D.C., dashing any hopes of a quick Union victory and leading Lincoln to call for 500,000 more recruits. In fact, both sides’ initial call for troops had to be widened after it became clear that the war would not be a limited or short conflict.

The Civil War in Virginia (1862)

George B. McClellan —who replaced the aging General Winfield Scott as supreme commander of the Union Army after the first months of the war—was beloved by his troops, but his reluctance to advance frustrated Lincoln. In the spring of 1862, McClellan finally led his Army of the Potomac up the peninsula between the York and James Rivers, capturing Yorktown on May 4. The combined forces of Robert E. Lee and Jackson successfully drove back McClellan’s army in the Seven Days’ Battles (June 25-July 1), and a cautious McClellan called for yet more reinforcements in order to move against Richmond. Lincoln refused, and instead withdrew the Army of the Potomac to Washington. By mid-1862, McClellan had been replaced as Union general-in-chief by Henry W. Halleck, though he remained in command of the Army of the Potomac.

Lee then moved his troops northwards and split his men, sending Jackson to meet Pope’s forces near Manassas, while Lee himself moved separately with the second half of the army. On August 29, Union troops led by John Pope struck Jackson’s forces in the Second Battle of Bull Run (Second Manassas). The next day, Lee hit the Federal left flank with a massive assault, driving Pope’s men back towards Washington. On the heels of his victory at Manassas, Lee began the first Confederate invasion of the North. Despite contradictory orders from Lincoln and Halleck, McClellan was able to reorganize his army and strike at Lee on September 14 in Maryland, driving the Confederates back to a defensive position along Antietam Creek, near Sharpsburg.

On September 17, the Army of the Potomac hit Lee’s forces (reinforced by Jackson’s) in what became the war’s bloodiest single day of fighting. Total casualties at the Battle of Antietam (also known as the Battle of Sharpsburg) numbered 12,410 of some 69,000 troops on the Union side, and 13,724 of around 52,000 for the Confederates. The Union victory at Antietam would prove decisive, as it halted the Confederate advance in Maryland and forced Lee to retreat into Virginia. Still, McClellan’s failure to pursue his advantage earned him the scorn of Lincoln and Halleck, who removed him from command in favor of Ambrose E. Burnside . Burnside’s assault on Lee’s troops near Fredericksburg on December 13 ended in heavy Union casualties and a Confederate victory; he was promptly replaced by Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker , and both armies settled into winter quarters across the Rappahannock River from each other.

After the Emancipation Proclamation (1863-4)

Lincoln had used the occasion of the Union victory at Antietam to issue a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation , which freed all enslaved people in the rebellious states after January 1, 1863. He justified his decision as a wartime measure, and did not go so far as to free the enslaved people in the border states loyal to the Union. Still, the Emancipation Proclamation deprived the Confederacy of the bulk of its labor forces and put international public opinion strongly on the Union side. Some 186,000 Black Civil War soldiers would join the Union Army by the time the war ended in 1865, and 38,000 lost their lives.

In the spring of 1863, Hooker’s plans for a Union offensive were thwarted by a surprise attack by the bulk of Lee’s forces on May 1, whereupon Hooker pulled his men back to Chancellorsville. The Confederates gained a costly victory in the Battle of Chancellorsville , suffering 13,000 casualties (around 22 percent of their troops); the Union lost 17,000 men (15 percent). Lee launched another invasion of the North in June, attacking Union forces commanded by General George Meade on July 1 near Gettysburg, in southern Pennsylvania. Over three days of fierce fighting, the Confederates were unable to push through the Union center, and suffered casualties of close to 60 percent.

Meade failed to counterattack, however, and Lee’s remaining forces were able to escape into Virginia, ending the last Confederate invasion of the North. Also in July 1863, Union forces under Ulysses S. Grant took Vicksburg (Mississippi) in the Siege of Vicksburg , a victory that would prove to be the turning point of the war in the western theater. After a Confederate victory at Chickamauga Creek, Georgia, just south of Chattanooga, Tennessee, in September, Lincoln expanded Grant’s command, and he led a reinforced Federal army (including two corps from the Army of the Potomac) to victory in the Battle of Chattanooga in late November.

Toward a Union Victory (1864-65)

In March 1864, Lincoln put Grant in supreme command of the Union armies, replacing Halleck. Leaving William Tecumseh Sherman in control in the West, Grant headed to Washington, where he led the Army of the Potomac towards Lee’s troops in northern Virginia. Despite heavy Union casualties in the Battle of the Wilderness and at Spotsylvania (both May 1864), at Cold Harbor (early June) and the key rail center of Petersburg (June), Grant pursued a strategy of attrition, putting Petersburg under siege for the next nine months.

Sherman outmaneuvered Confederate forces to take Atlanta by September, after which he and some 60,000 Union troops began the famous “March to the Sea,” devastating Georgia on the way to capturing Savannah on December 21. Columbia and Charleston, South Carolina, fell to Sherman’s men by mid-February, and Jefferson Davis belatedly handed over the supreme command to Lee, with the Confederate war effort on its last legs. Sherman pressed on through North Carolina, capturing Fayetteville, Bentonville, Goldsboro and Raleigh by mid-April.

Meanwhile, exhausted by the Union siege of Petersburg and Richmond, Lee’s forces made a last attempt at resistance, attacking and captured the Federal-controlled Fort Stedman on March 25. An immediate counterattack reversed the victory, however, and on the night of April 2-3 Lee’s forces evacuated Richmond. For most of the next week, Grant and Meade pursued the Confederates along the Appomattox River, finally exhausting their possibilities for escape. Grant accepted Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9. On the eve of victory, the Union lost its great leader: The actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre in Washington on April 14. Sherman received Johnston’s surrender at Durham Station, North Carolina on April 26, effectively ending the Civil War.

HISTORY Vault: The Secret History of the Civil War

The American Civil War is one of the most studied and dissected events in our history—but what you don't know may surprise you.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

150 Years of Misunderstanding the Civil War

As the anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg approaches, it's time for America to question the popular account of a war that tore apart the nation.

In early July, on the 150 th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, pilgrims will crowd Little Round Top and the High Water Mark of Pickett's Charge. But venture beyond these famous shrines to battlefield valor and you'll find quiet sites like Iverson's Pits, which recall the inglorious reality of Civil War combat.

On July 1 st , 1863, Alfred Iverson ordered his brigade of North Carolinians across an open field. The soldiers marched in tight formation until Union riflemen suddenly rose from behind a stone wall and opened fire. Five hundred rebels fell dead or wounded "on a line as straight as a dress parade," Iverson reported. "They nobly fought and died without a man running to the rear. No greater gallantry and heroism has been displayed during this war."

Soldiers told a different story: of being "sprayed by the brains" of men shot in front of them, or hugging the ground and waving white kerchiefs. One survivor informed the mother of a comrade that her son was "shot between the Eye and ear" while huddled in a muddy swale. Of others in their ruined unit he wrote: "left arm was cut off, I think he will die... his left thigh hit and it was cut off." An artilleryman described one row of 79 North Carolinians executed by a single volley, their dead feet perfectly aligned. "Great God! When will this horrid war stop?" he wrote. The living rolled the dead into shallow trenches--hence the name "Iverson's Pits," now a grassy expanse more visited by ghost-hunters than battlefield tourists.

This and other scenes of unromantic slaughter aren't likely to get much notice during the Gettysburg sesquicentennial, the high water mark of Civil War remembrance. Instead, we'll hear a lot about Joshua Chamberlain's heroism and Lincoln's hallowing of the Union dead.

It's hard to argue with the Gettysburg Address. But in recent years, historians have rubbed much of the luster from the Civil War and questioned its sanctification. Should we consecrate a war that killed and maimed over a million Americans? Or should we question, as many have in recent conflicts, whether this was really a war of necessity that justified its appalling costs?

"We've decided the Civil War is a 'good war' because it destroyed slavery," says Fitzhugh Brundage, a historian at the University of North Carolina. "I think it's an indictment of 19 th century Americans that they had to slaughter each other to do that."

Similar reservations were voiced by an earlier generation of historians known as revisionists. From the 1920s to 40s, they argued that the war was not an inevitable clash over irreconcilable issues. Rather, it was a "needless" bloodbath, the fault of "blundering" statesmen and "pious cranks," mainly abolitionists. Some revisionists, haunted by World War I, cast all war as irrational, even "psychopathic."

World War II undercut this anti-war stance. Nazism was an evil that had to be fought. So, too, was slavery, which revisionists--many of them white Southerners--had cast as a relatively benign institution, and dismissed it as a genuine source of sectional conflict. Historians who came of age during the Civil Rights Movement placed slavery and emancipation at the center of the Civil War. This trend is now reflected in textbooks and popular culture. The Civil War today is generally seen as a necessary and ennobling sacrifice, redeemed by the liberation of four million slaves.

But cracks in this consensus are appearing with growing frequency, for example in studies like America Aflame , by historian David Goldfield. Goldfield states on the first page that the war was "America's greatest failure." He goes on to impeach politicians, extremists, and the influence of evangelical Christianity for polarizing the nation to the point where compromise or reasoned debate became impossible.

Unlike the revisionists of old, Goldfield sees slavery as the bedrock of the Southern cause and abolition as the war's great achievement. But he argues that white supremacy was so entrenched, North and South, that war and Reconstruction could never deliver true racial justice to freed slaves, who soon became subject to economic peonage, Black Codes, Jim Crow, and rampant lynching.

Few contemporary scholars go as far as Goldfield, but others are challenging key tenets of the current orthodoxy. Gary Gallagher, a leading Civil War historian at the University of Virginia, argues that the long-reigning emphasis on slavery and liberation distorts our understanding of the war and of how Americans thought in the 1860s. "There's an Appomattox syndrome--we look at Northern victory and emancipation and read the evidence backward," Gallagher says.

Very few Northerners went to war seeking or anticipating the destruction of slavery. They fought for Union, and the Emancipation Proclamation was a means to that end: a desperate measure to undermine the South and save a democratic nation that Lincoln called "the last best, hope of earth."

Recommended Reading

The Nasty Logistics of Returning Your Too-Small Pants

The Pandemic Has Created a Class of Super-Savers

This Is What Happens When You Drunkenly Swallow a Live Catfish

Gallagher also feels that hindsight has dimmed recognition of how close the Confederacy came to achieving its aims. "For the South, a tie was as good as a win," he says. It needed to inflict enough pain to convince a divided Northern public that defeating the South wasn't worth the cost. This nearly happened at several points, when rebel armies won repeated battles in 1862 and 1863. As late as the summer of 1864, staggering casualties and the stalling of Union armies brought a collapse in Northern morale, cries for a negotiated peace, and the expectation that anti-war (and anti-black) Democrats would take the White House. The fall of Atlanta that September narrowly saved Lincoln and sealed the South's eventual surrender.

Allen Guelzo, director of Civil War studies at Gettysburg College, adds the Pennsylvania battle to the roster of near-misses for the South. In his new book, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion , he identifies points when Lee's army came within minutes of breaking the Union line. If it had, he believes the already demoralized Army of the Potomac "would have gone to pieces." With a victorious Southern army on the loose, threatening Northern cities, "it would have been game over for the Union."

Imagining these and other scenarios isn't simply an exercise in "what if" history, or the fulfillment of Confederate fantasy fiction. It raises the very real possibility that many thousands of Americans might have died only to entrench secession and slavery. Given this risk, and the fact that Americans at the time couldn't see the future, Andrew Delbanco wonders if we ourselves would have regarded the defeat of the South as worth pursuing at any price. "Vindicated causes are easy to endorse," he observes in The Abolitionist Imagination.

Recent scholarship has also cast new light on the scale and horror of the nation's sacrifice. Soldiers in the 1860s didn't wear dog tags, the burial site of most was unknown, and casualty records were sketchy and often lost. Those tallying the dead in the late 19 th century relied on estimates and assumptions to arrive at a figure of 618,000, a toll that seemed etched in stone until just a few years ago.

But J. David Hacker, a demographic historian, has used sophisticated analysis of census records to revise the toll upward by 20%, to an estimated 750,000, a figure that has won wide acceptance from Civil War scholars. If correct, the Civil War claimed more lives than all other American wars combined, and the increase in population since 1860 means that a comparable war today would cost 7.5 million lives.

This horrific toll doesn't include the more than half million soldiers who were wounded and often permanently disabled by amputation, lingering disease, psychological trauma and other afflictions. Veterans themselves rarely dwelled on this suffering, at least in their writing. "They walled off the horror and mangling and tended to emphasize the nobility of sacrifice," says Allen Guelzo. So did many historians, who cited the numbing totals of dead and wounded but rarely delved into the carnage or its societal impact.

That's changed dramatically with pioneering studies such as Drew Gilpin Faust's This Republic of Suffering , a 2008 examination of "the work of death" in the Civil War: killing, dying, burying, mourning, counting. "Civil War history has traditionally had a masculine view," says Faust, now president of Harvard, "it's all about generals and statesmen and glory." From reading the letters of women during the war, though, she sensed the depth of Americans' fear, grief, and despair. Writing her book amid "the daily drumbeat of loss" in coverage of Iraq and Afghanistan, Faust's focus on the horrors of this earlier war was reinforced.

"When we go to war, we ought to understand the costs," she says. "Human beings have an extraordinary capacity to forget that. Americans went into the Civil War imagining glorious battle, not gruesome disease and dismemberment."

Disease, in fact, killed roughly twice as many soldiers as did combat; dysentery and diarrhea alone killed over 44,000 Union soldiers, more than ten times the Northern dead at Gettysburg. Amputations were so routine, Faust notes, that soldiers and hospital workers frequently described severed limbs stacked "like cord wood," or heaps of feet, legs and arms being hauled off in carts, as if from "a human slaughterhouse." In an era before germ theory, surgeons' unclean saws and hands became vectors for infection that killed a quarter or more of the 60,000 or so men who underwent amputation.

Other historians have exposed the savagery and extent of the war that raged far from the front lines, including guerrilla attacks, massacres of Indians, extra-judicial executions and atrocities against civilians, some 50,000 of whom may have died as a result of the conflict. "There's a violence within and around the Civil War that doesn't fit the conventional, heroic narrative,' says Fitzhugh Brundage, whose research includes torture during the war. "When you incorporate these elements, the war looks less like a conflict over lofty principles and more like a cross-societal bloodletting."

In other words, it looks rather like ongoing wars in the Middle East and Afghanistan, which have influenced today's scholars and also their students. Brundage sees a growing number of returning veterans in his classes at the University of North Carolina, and new interest in previously neglected aspects of the Civil War era, such as military occupation, codes of justice, and the role of militias and insurgents.

More broadly, he senses an opening to question the limits of war as a force for good. Just as the fight against Nazism buttressed a moral vision of the Civil War, so too have the last decade's conflicts given us a fresh and cautionary viewpoint. "We should be chastened by our inability to control war and its consequences," Brundage says. "So much of the violence in the Civil War is laundered or sanctified by emancipation, but that result was by no means inevitable."

It's very hard, however, to see how emancipation might have been achieved by means other than war. The last century's revisionists thought the war was avoidable because they didn't regard slavery as a defining issue or evil. Almost no one suggests that today. The evidence is overwhelming that slavery was the "cornerstone" of the Southern cause, as the Confederacy's vice-president stated, and the source of almost every aspect of sectional division.

Slaveholders also resisted any infringement of their right to human property. Lincoln, among many others, advocated the gradual and compensated emancipation of slaves. This had been done in the British West Indies, and would later end slavery in Brazil and Cuba. In theory it could have worked here. Economists have calculated that the cost of the Civil War, estimated at over $10 billion in 1860 dollars, would have been more than enough to buy the freedom of every slave, purchase them land, and even pay reparations. But Lincoln's proposals for compensated emancipation fell on deaf ears, even in wartime Delaware, which was behind Union lines and clung to only 2,000 slaves, about 1.5% of the state's population.

Nor is there much credible evidence that the South's "peculiar institution" would have peacefully waned on its own. Slave-grown cotton was booming in 1860, and slaves in non-cotton states like Virginia were being sold to Deep South planters at record prices, or put to work on railroads and in factories. "Slavery was a virus that could attach itself to other forms," says historian Edward Ayers, president of the University of Richmond. "It was stronger than it had ever been and was growing stronger."

Most historians believe that without the Civil War, slavery would have endured for decades, possibly generations. Though emancipation was a byproduct of the war, not its aim, and white Americans clearly failed during Reconstruction to protect and guarantee the rights of freed slaves, the post-war amendments enshrined the promise of full citizenship and equality in the Constitution for later generations to fulfill.

What this suggests is that the 150 th anniversary of the Civil War is too narrow a lens through which to view the conflict. We are commemorating the four years of combat that began in 1861 and ended with Union victory in 1865. But Iraq and Afghanistan remind us, yet again, that the aftermath of war matters as much as its initial outcome. Though Confederate armies surrendered in 1865, white Southerners fought on by other means, wearing down a war-weary North that was ambivalent about if not hostile to black equality. Looking backwards, and hitting the pause button at the Gettysburg Address or the passage of the 13 th amendment, we see a "good" and successful war for freedom. If we focus instead on the run-up to war, when Lincoln pledged to not interfere with slavery in the South, or pan out to include the 1870s, when the nation abandoned Reconstruction, the story of the Civil War isn't quite so uplifting.

But that also is an arbitrary and insufficient frame. In 1963, a century after Gettysburg, Martin Luther King Jr. invoked Lincoln's words and the legacy of the Civil War in calling on the nation to pay its "promissory note" to black Americans, which it finally did, in part, by passing Civil Rights legislation that affirmed and enforced the amendments of the 1860s. In some respects, the struggle for racial justice, and for national cohesion, continues still.

From the distance of 150 years, Lincoln's transcendent vision at Gettysburg of a "new birth of freedom" seems premature. But he himself acknowledged the limits of remembrance. Rather than simply consecrate the dead with words, he said, it is for "us the living" to rededicate ourselves to the unfinished work of the Civil War.

- Search Menu

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access Options

- Why Publish with JAH?

- About Journal of American History

- About the Organization of American Historians

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Space, time, and sectionalism, the historian's use of sectionalism and vice versa, … with liberty and justice for whom.

- < Previous

What Twenty-First-Century Historians Have Said about the Causes of Disunion: A Civil War Sesquicentennial Review of the Recent Literature

I would like to thank David Dangerfield, Allen Driggers, Tiffany Florvil, Margaret Gillikin, Ramon Jackson, Evan Kutzler, Tyler Parry, David Prior, Tara Strauch, Beth Toyofuku, and Ann Tucker for their comments on an early version of this essay, and to extend special thanks to Mark M. Smith for perceptive criticism of multiple drafts. I would also like to thank Edward Linenthal for his expert criticism and guidance through the publication process and to express my gratitude to the four JAH readers, Ann Fabian, James M. McPherson, Randall Miller, and one anonymous reviewer, for their exceptionally thoughtful and helpful comments on the piece.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Michael E. Woods, What Twenty-First-Century Historians Have Said about the Causes of Disunion: A Civil War Sesquicentennial Review of the Recent Literature, Journal of American History , Volume 99, Issue 2, September 2012, Pages 415–439, https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jas272

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Professional historians can be an argumentative lot, but by the dawn of the twenty-first century, a broad consensus regarding Civil War causation clearly reigned. Few mainstream scholars would deny that Abraham Lincoln got it right in his second inaugural address—that slavery was “somehow” the cause of the war. Public statements by preeminent historians reaffirmed that slavery's centrality had been proven beyond a reasonable doubt. Writing for the popular Civil War magazine North and South in November 2000, James M. McPherson pointed out that during the war, “few people in either North or South would have dissented” from Lincoln's slavery-oriented account of the war's origins. In ten remarkably efficient pages, McPherson dismantled arguments that the war was fought over tariffs, states' rights, or the abstract principle of secession. That same year, Charles Joyner penned a report on Civil War causation for release at a Columbia, South Carolina, press conference at the peak of the Palmetto State's Confederate flag debate. Endorsed by dozens of scholars and later published in Callaloo, it concluded that the “historical record … clearly shows that the cause for which the South seceded and fought a devastating war was slavery.” 1

Despite the impulse to close ranks amid the culture wars, however, professional historians have not abandoned the debate over Civil War causation. Rather, they have rightly concluded that there is not much of a consensus on the topic after all. Elizabeth Varon remarks that although “scholars can agree that slavery, more than any other issue, divided North and South, there is still much to be said about why slavery proved so divisive and why sectional compromise ultimately proved elusive.” And as Edward Ayers observes: “slavery and freedom remain the keys to understanding the war, but they are the place to begin our questions, not to end them.” 2 The continuing flood of scholarship on the sectional conflict suggests that many other historians agree. Recent work on the topic reveals two widely acknowledged truths: that slavery was at the heart of the sectional conflict and that there is more to learn about precisely what this means, not least because slavery was always a multifaceted issue.

This essay analyzes the extensive literature on Civil War causation published since 2000, a body of work that has not been analyzed at length. This survey cannot be comprehensive but seeks instead to clarify current debates in a field long defined by distinct interpretive schools—such as those of the progressives, revisionists, and modernization theorists—whose boundaries are now blurrier. To be sure, echoes still reverberate of the venerable arguments between historians who emphasize abstract economic, social, or political forces and those who stress human agency. The classic interpretive schools still command allegiance, with fundamentalists who accentuate concrete sectional differences dueling against revisionists, for whom contingency, chance, and irrationality are paramount. But recent students of Civil War causation have not merely plowed familiar furrows. They have broken fresh ground, challenged long-standing assumptions, and provided new perspectives on old debates. This essay explores three key issues that vein the recent scholarship: the geographic and temporal parameters of the sectional conflict, the relationship between sectionalism and nationalism, and the relative significance of race and class in sectional politics. All three problems stimulated important research long before 2000, but recent work has taken them in new directions. These themes are particularly helpful for navigating the recent scholarship, and by using them to organize and evaluate the latest literature, this essay underscores fruitful avenues for future study of a subject that remains central in American historiography. 3

Historians of the sectional conflict, like their colleagues in other fields, have consciously expanded the geographic and chronological confines of their research. Crossing the borders of the nation-state and reaching back toward the American Revolution, many recent studies of the war's origins situate the clash over slavery within a broad spatial and temporal context. The ramifications of this work will not be entirely clear until an enterprising scholar incorporates those studies into a new synthesis, but this essay will offer a preliminary evaluation.

Scholarship following the transnational turn in American history has silenced lingering doubts that nineteenth-century Americans of all regions, classes, and colors were deeply influenced by people, ideas, and events from abroad. Historians have long known that the causes of the Civil War cannot be understood outside the context of international affairs, particularly the Mexican-American War (1846–1848). Three of the most influential narrative histories of the Civil War era open either on Mexican soil (those written by Allan Nevins and James McPherson) or with the transnational journey from Mexico City to Washington of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (David M. Potter's The Impending Crisis ). The domestic political influence of the annexation of Texas, Caribbean filibustering, and the Ostend Manifesto, a widely publicized message written to President Franklin Pierce in 1854 that called for the acquisition of Cuba, are similarly well established. 4

Recent studies by Edward Bartlett Rugemer and Matthew J. Clavin, among others, build on that foundation to show that the international dimensions of the sectional conflict transcended the bitterly contested question of territorial expansion. Rugemer, for instance, demonstrates that Caribbean emancipation informed U.S. debates over slavery from the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) through Reconstruction. Situating sectional politics within the Atlantic history of slavery and abolition, he illustrates how arguments for and against U.S. slavery drew from competing interpretations of emancipation in the British West Indies. Britain's “mighty experiment” thus provided “useable history for an increasingly divided nation.” Proslavery ideologues learned that abolitionism sparked insurrection, that Africans and their descendants would become idlers or murderers or both if released from bondage, and that British radicals sought to undermine the peculiar institution wherever it persisted. To slavery's foes, the same history revealed that antislavery activism worked, that emancipation could be peaceful and profitable, and that servitude, not skin tone, degraded enslaved laborers. Clavin's study of American memory of Toussaint L'Ouverture indicates that the Haitian Revolution cast an equally long shadow over antebellum history. Construed as a catastrophic race war, the revolution haunted slaveholders with the prospect of an alliance between ostensibly savage slaves and fanatical whites. Understood as a hopeful story of the downtrodden overthrowing their oppressors, however, Haitian history furnished abolitionists, white and black, with an inspiring example of heroic self-liberation by the enslaved. By the 1850s it also furnished abolitionists, many of whom were frustrated by the abysmally slow progress of emancipation in the United States, with a precedent for swift, violent revolution and the vindication of black masculinity. The Haitian Revolution thus provided “resonant, polarizing, and ultimately subversive symbols” for antislavery and proslavery partisans alike and helped “provoke a violent confrontation and determine the fate of slavery in the United States.” 5

These findings will surprise few students of Civil War causation, but they demonstrate that the international aspects of the sectional conflict did not begin and end with Manifest Destiny. They also encourage Atlantic historians to pay more attention to the nineteenth century, particularly to the period after British emancipation. Rugemer and Clavin point out that deep connections among Atlantic rim societies persisted far into the nineteenth century and that, like other struggles over New World slavery, the American Civil War is an Atlantic story. One of their most stimulating contributions may therefore be to encourage Atlantic historians to widen their temporal perspectives to include the middle third of the nineteenth century. By foregrounding the hotly contested public memory of the Haitian Revolution, Rugemer and Clavin push the story of American sectionalism back into the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, suggesting that crossing geographic boundaries can go hand in hand with stretching the temporal limits of sectionalism. 6

The internationalizing impulse has also nurtured economic interpretations of the sectional struggle. Brian Schoen, Peter Onuf, and Nicholas Onuf situate antebellum politics within the context of global trade, reinvigorating economic analysis of sectionalism without summoning the ghosts of Charles Beard and Mary Beard. Readers may balk at their emphasis on tariff debates, but these histories are plainly not Confederate apologia. As Schoen points out, chattel slavery expanded in the American South, even as it withered throughout most of the Atlantic world, because southern masters embraced the nineteenth century's most important crop: cotton. Like the oil titans of a later age, southern cotton planters reveled in the economic indispensability of their product. Schoen adopts a cotton-centered perspective from which to examine southern political economy, from the earliest cotton boom to the secession crisis. “Broad regional faith in cotton's global power,” he argues, “both informed secessionists' actions and provided them an indispensable tool for mobilizing otherwise reluctant confederates.” Planters' commitment to the production and overseas sale of cotton shaped southern politics and business practices. It impelled westward expansion, informed planters' jealous defense of slavery, and wedded them to free trade. An arrogant faith in their commanding economic position gave planters the impetus and the confidence to secede when northern Republicans threatened to block the expansion of slavery and increase the tariff. The Onufs reveal a similar dynamic at work in their complementary study, Nations, Markets, and War. Like Schoen, they portray slaveholders as forward-looking businessmen who espoused free-trade liberalism in defense of their economic interests. Entangled in political competition with Yankee protectionists throughout the early national and antebellum years, slaveholders seceded when it became clear that their vision for the nation's political economy—most importantly its trade policy—could no longer prevail. 7

These authors examine Civil War causation within a global context, though in a way more reminiscent of traditional economic history than similar to other recent transnational scholarship. But perhaps the most significant contribution made by these authors lies beyond internationalizing American history. After all, most historians of the Old South have recognized that the region's economic and political power depended on the Atlantic cotton trade, and scholars of the Confederacy demonstrated long ago that overconfidence in cotton's international leverage led southern elites to pursue a disastrous foreign policy. What these recent studies reveal is that cotton-centered diplomatic and domestic politics long predated southern independence and had roots in the late eighteenth century, when slaveholders' decision to enlarge King Cotton's domain set them on a turbulent political course that led to Appomattox. The Onufs and Schoen, then, like Rugemer and Clavin, expand not only the geographic parameters of the sectional conflict but also its temporal boundaries. 8

These four important histories reinforce recent work that emphasizes the eruption of the sectional conflict at least a generation before the 1820 Missouri Compromise. If the conflict over Missouri was a “firebell in the night,” as Thomas Jefferson called it, it was a rather tardy alarm. This scholarship mirrors a propensity among political historians—most notably scholars of the civil rights movement—to write “long histories.” Like their colleagues who dispute the Montgomery-to-Memphis narrative of the civil rights era, political historians of the early republic have questioned conventional periodization by showing that sectionalism did not spring fully grown from the head of James Tallmadge, the New York congressman whose February 1819 proposal to bar the further extension of slavery into Missouri unleashed the political storm that was calmed, for the moment, by the Missouri Compromise. Matthew Mason, for instance, maintains that “there never was a time between the Revolution and the Civil War in which slavery went unchallenged.” Mason shows that political partisans battered their rivals with the club of slavery, with New England Federalists proving especially adept at denouncing their Jeffersonian opponents as minions of southern slaveholders. In a series of encounters, from the closure of the Atlantic slave trade in 1807 to the opening (fire)bell of the Missouri crisis, slavery remained a central question in American politics. Even the outbreak of war in 1812 failed to suppress the issue. 9

A complementary study by John Craig Hammond confirms that slavery roiled American politics from the late eighteenth century on and that its westward expansion proved especially divisive years before the Missouri fracas. As America's weak national government continued to bring more western acreage under its nominal control, it had to accede to local preferences regarding slavery. Much of the fierce conflict over slavery therefore occurred at the territorial and state levels. Hammond astutely juxtaposes the histories of slave states such as Louisiana and Missouri alongside those of Ohio and Indiana, where proslavery policies were defeated. In every case, local politics proved decisive. Neither the rise nor the extent of the cotton kingdom was a foregone conclusion, and the quarrel over its expansion profoundly influenced territorial and state politics north and south of the Ohio River. Bringing the growing scholarship on both early republic slavery and proslavery ideology into conversation with political history, Hammond demonstrates that the bitterness of the Missouri debate stemmed from that dispute's contentious prehistory, not from its novelty. Just as social, economic, and intellectual historians have traced the “long history” of the antebellum South back to its once relatively neglected early national origins, political historians have uncovered the deep roots of political discord over slavery's expansion. 10

Scholars have applied the “long history” principle to other aspects of Civil War causation as well. In his study of the slave power thesis, Leonard L. Richards finds that northern anxieties about slaveholders' inordinate political influence germinated during the 1787 Constitutional Convention. Jan Lewis's argument that the concessions made to southern delegates at the convention emboldened them to demand special protection for slavery suggests that those apprehensions were sensible. David L. Lightner demonstrates that northern demands for a congressional ban on the domestic slave trade, designed to strike a powerful and, thanks to the interstate commerce clause, constitutional blow against slavery extension emerged during the first decade of the nineteenth century and informed antislavery strategy for the next fifty years. Richard S. Newman emphasizes that abolitionist politics long predated William Lloyd Garrison's founding of the Liberator in 1831. Like William W. Freehling, who followed the “road to disunion” back to the American Revolution, Newman commences his study of American abolitionism with the establishment of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society in 1775. Most recently, Christopher Childers has invited historians to explore the early history of the doctrine of popular sovereignty. 11

Skeptics might ask where the logic of these studies will lead. Why not push the origins of sectional strife even further back into colonial history? Why not begin, as did a recent overview of Civil War causation, with the initial arrival of African slaves in Virginia in 1619? This critique has a point—hopefully we will never read an article called “Christopher Columbus and the Coming of the American Civil War”—but two virtues of recent work on the long sectional conflict merit emphasis. First, its extended view mirrors the very long, if chronically selective, memories of late antebellum partisans. By the 1850s few sectional provocateurs failed to trace northern belligerence toward the South, and vice versa, back to the eighteenth century. Massachusetts Republican John B. Alley reminded Congress in April 1860 that slavery had been “a disturbing element in our national politics ever since the organization of the Government.” “In fact,” Alley recalled, “political differences were occasioned by it, and sectional prejudices grew out of it, at a period long anterior to the formation of the Federal compact.” Eight tumultuous months later, U.S. senator Robert Toombs recounted to the Georgia legislature a litany of northern aggressions and insisted that protectionism and abolitionism had tainted Yankee politics from “ the very first Congress .” Tellingly, the study of historical memory, most famously used to analyze remembrance of the Civil War, has moved the study of Civil War causation more firmly into the decades between the nation's founding and the Missouri Compromise. Memories of the Haitian Revolution shaped antebellum expectations for emancipation. Similarly, recollections of southern economic sacrifice during Jefferson's 1807 embargo and the War of 1812 heightened white southerners' outrage over their “exclusion” from conquered Mexican territory more than three decades later. And as Margot Minardi has shown, Massachusetts abolitionists used public memory of the American Revolution to champion emancipation and racial equality. The Missouri-to-Sumter narrative conceals that these distant events haunted the memories of late antebellum Americans. Early national battles over slavery did not make the Civil War inevitable, but in the hands of propagandists they could make the war seem inevitable to many contemporaries. 12

Second, proponents of the long view of Civil War causation have not made a simplistic argument for continuity. Elizabeth Varon's study of the evolution of disunion as a political concept and rhetorical device from 1789 to 1859 demonstrates that long histories need not obscure change over time. Arguing that “sectional tensions deriving from the diverging interests of the free labor North and the slaveholding South” were “as old as the republic itself,” Varon adopts a long perspective on sectional tension. But her nuanced analysis of the diverse and shifting political uses of disunion rhetoric suggests that what historians conveniently call the sectional conflict was in fact a series of overlapping clashes, each with its own dynamics and idiom. Quite literally, the terms of sectional debate remained in flux. The language of disunion came in five varieties—“a prophecy of national ruin, a threat of withdrawal from the federal compact, an accusation of treasonous plotting, a process of sectional alienation, and a program for regional independence”—and the specific meanings of each cannot be interpreted accurately without regard to historical context, for “their uses changed and shifted over time.” To cite just one example, the concept of disunion as a process of increasing alienation between North and South gained credibility during the 1850s as proslavery and antislavery elements clashed, often violently, over the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and the extension of slavery into Kansas. Republican senator William Henry Seward's famous “irrepressible conflict” speech of 1858 took this interpretation of disunion, one that had long languished on the radical margins of sectional politics, and thrust it into mainstream discourse. Shifting political circumstances reshaped the terms of political debate from the 1830s, when the view of disunion as an irreversible process flourished only among abolitionists and southern extremists, to the late 1850s, when a leading contender for the presidential nomination of a major party could express it openly. 13

Consistent with Varon's emphasis on the instability of political rhetoric, other recent studies of Civil War causation have spotlighted two well-known and important forks in the road to disunion. Thanks to their fresh perspective on the crisis of 1819–1821, scholars of early national sectionalism have identified the Missouri struggle as the first of these turning points. The battle over slavery in Missouri, Robert Pierce Forbes argues, was “a crack in the master narrative” of American history that fundamentally altered how Americans thought about slavery and the Union. In the South, it nurtured a less crassly self-interested defense of servitude. Simultaneously, it tempted northerners to conceptually separate “the South” from “America,” thereby sectionalizing the moral problem of slavery and conflating northern values and interests with those of the nation. The intensity of the crisis demonstrated that the slavery debate threatened the Union, prompting Jacksonian-era politicians to suppress the topic and stymie sectionalists for a generation. But even as the Missouri controversy impressed moderates with the need for compromise, it fostered “a new clarity in the sectional politics of the United States and moved each section toward greater coherence on the slavery issue” by refining arguments for and against the peculiar institution. The competing ideologies that defined antebellum sectional politics coalesced during the contest over Missouri, now portrayed as a milestone rather than a starter's pistol. 14

A diverse body of scholarship identifies a second period of discontinuity stretching from 1845 to 1850. This literature confirms rather than challenges traditional periodization, for those years have long marked the beginning of the “Civil War era.” This time span has attracted considerable attention because the slavery expansion debate intensified markedly between the annexation of Texas in 1845 and the Compromise of 1850. Not surprisingly, recent work on slavery's contested westward extension continues to present the late 1840s as a key turning point—perhaps a point of no return—in the sectional conflict. As Michael S. Green puts it, by 1848, “something in American political life clearly had snapped. … [T]he genies that [James K.] Polk, [David] Wilmot, and their allies had let out of the bottle would not be put back in.” 15

Scholars not specifically interested in slavery expansion have also identified the late 1840s as a decisive period. In his history of southern race mythology—the notion that white southerners' “Norman” ancestry elevated them over Saxon-descended northerners—Ritchie Devon Watson Jr. identifies these years as a transition period between two theories of sectional difference. White southerners' U.S. nationalism persisted into the 1840s, he argues, and although they recognized cultural differences between the Yankees and themselves, the dissimilarities were not imagined in racial terms. After 1850, however, white southerners increasingly argued for innate differences between the white southern “race” and its ostensibly inferior northern rival. This mythology was a “key element” in the “flowering of southern nationalism before and during the Civil War.” Susan-Mary Grant has shown that northern opinion of the South underwent a simultaneous shift, with the slave power thesis gaining widespread credibility by the late 1840s. The year 1850 marked an economic turning point as well. Marc Egnal posits that around that year, a generation of economic integration between North and South gave way to an emerging “Lake Economy,” which knit the Northwest and Northeast into an economic and political alliance at odds with the South. Taken together, this scholarship reaffirms what historians have long suspected about the sectional conflict: despite sectionalism's oft-recalled roots in the early national period, the late 1840s represents an important period of discontinuity. It is unsurprising that these years climaxed with a secession scare and a makeshift compromise reached not through bona fide give-and-take but rather through the political dexterity of Senator Stephen A. Douglas. 16

That Douglas succeeded where the eminent Henry Clay had failed suggests another late 1840s discontinuity that deserves more scholarly attention. Thirty-six years older than the Little Giant, Clay was already Speaker of the House when Douglas was born in 1813. Douglas's shepherding of Clay's smashed omnibus bill through the Senate in 1850 “marked a changing of the guard from an older generation, whose time already might have passed, to a new generation whose time had yet to come.” This passing of the torch symbolized a broader shift in political personnel. The Thirty-First Congress, which passed the compromise measures of 1850, was a youthful assembly. The average age for representatives was forty-three, only two were older than sixty-two, and more than half were freshmen. The Senate was similarly youthful, particularly its Democratic members, fewer than half of whom had reached age fifty. Moreover, the deaths of John C. Calhoun, Henry Clay, and Daniel Webster between March 1850 and October 1852 signaled to many observers the end of an era. In 1851 members of the University of Virginia's Southern Rights Association reminded their southern peers that “soon the destinies of the South must be entrusted to our keeping. The present occupants of the arena of action must soon pass away, and we be called upon to fill their places. … It becomes therefore our sacred duty to prepare for the contest.” 17

Students of Civil War causation would do well to probe this intergenerational transfer of power. This analysis need not revive the argument, most popular in the 1930s and 1940s, that the “blundering generation” of hot-headed and self-serving politicos who grasped the reins of power around 1850 brought on an unnecessary war. Caricaturing the rising generation as exceptionally inept is not required to profitably contrast the socioeconomic environments, political contexts, and intellectual milieus in which Clay's and Douglas's respective generations matured. These differences, and the generational conflict that they engendered, may have an important bearing on both the origins and the timing of the Civil War. Peter Carmichael's study of Virginia's last antebellum generation explores this subject in detail. Historians have long recognized that disproportionately high numbers of young white southerners supported secession. Carmichael offers a compelling explanation for why this was so, without portraying his subjects as mediocre statesmen or citing the eternal impetuousness of youth. Deftly blending cultural, social, economic, and political history, Carmichael rejects the notion that young Virginia gentlemen who came of age in the late 1850s were immature, impassioned, and reckless. They were, he argues, idealistic and ambitious men who believed deeply in progress but worried that their elders had squandered Virginia's traditional economic and political preeminence. Confronted with their state's apparent degeneration and their own lack of opportunity for advancement, Carmichael's young Virginians endorsed a pair of solutions that put them at odds with their conservative elders: economic diversification and, after John Brown's 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry, southern independence. Whether this generational dynamic extended beyond Virginia remains to be seen. But other recent works, including Stephen Berry's study of young white men in the Old South and Jon Grinspan's essay on youthful Republicans during the 1860 presidential campaign, indicate that similar concerns about progress, decline, and sectional destiny haunted many young minds on the eve of the Civil War. More work in this area is necessary, especially on how members of the new generation remembered the sectional conflict that had been raging since before they were born. Clearly, though, the generation that ascended to national leadership during the 1850s came of age in a very different world than had its predecessor. Further analysis of this shift promises to link the insights of the long sectional conflict approach (particularly regarding public memory) with the emphasis on late 1840s discontinuity that veins recent scholarship on sectionalism. 18

Recent historians have challenged conventional periodization by expanding the chronological scope of the sectional conflict, even as they confirm two key moments of historical discontinuity. This work revises older interpretations of Civil War causation without overturning them. A second trend in the literature, however, is potentially more provocative. A number of powerfully argued studies building on David Potter's classic essay, “The Historian's Use of Nationalism and Vice Versa,” have answered his call for closer scrutiny of the “seemingly manifest difference between the loyalties of a nationalistic North and a sectionalistic South.” Impatient with historians who read separatism into all aspects of prewar southern politics or Unionism into all things northern, Potter admonished scholars not to project Civil War loyalties back into the antebellum period. A more nuanced approach would reveal “that in the North as well as in the South there were deep sectional impulses, and support or nonsupport of the Union was sometimes a matter of sectional tactics rather than of national loyalty.” Recent scholars have accepted Potter's challenge, and their findings contribute to an emerging reinterpretation of the sectional conflict and the timing of secession. 19

Disentangling northern from national interests and values has been difficult thanks in part to the Civil War itself (in which “the North” and “the Union” overlapped, albeit imperfectly) and because of the northern victory and the temptation to classify the Old South as an un-American aberration. But several recent studies have risen to the task. Challenging the notion that the antebellum North must have been nationalistic because of its opposition to slavery and its role in the Civil War, Susan-Mary Grant argues that by the 1850s a stereotyped view of the South and a sense of moral and economic superiority had created a powerful northern sectional identity. Championed by the Republican party, this identity flowered into an exclusionary nationalism in which the South served as a negative reference point for the articulation of ostensibly national values, goals, and identities based on the North's flattering self-image. This sectionalism-cum-nationalism eventually corroded national ties by convincing northerners that the South represented an internal threat to the nation. Although this vision became genuinely national after the war, in the antebellum period it was sectionally specific and bitterly divisive. “It was not the case,” Grant concludes, “that the northern ideology of the antebellum period was American, truly national, and supportive of the Union and the southern ideology was wholly sectional and destructive of the Union.” Matthew Mason makes a related point about early national politics, noting that the original sectionalists were antislavery New England Federalists whose flirtation with secession in 1815 crippled their party. Never simply the repository of authentic American values, the nineteenth-century North developed a sectional identity in opposition to an imagined (though not fictitious) South. Only victory in the Civil War allowed for the reconstruction of the rest of the nation in this image. 20

If victory in the war obscured northern sectionalism, it was the defense of slavery, coupled with defeat, that has distorted our view of American nationalism in the Old South. The United States was founded as a slaveholding nation, and there was unfortunately nothing necessarily un-American about slavery in the early nineteenth century. Slavery existed in tension with, not purely in opposition to, the nation's perennially imperfect political institutions, and its place in the young republic was a hotly contested question with a highly contingent resolution. Moreover, despite their pretensions to being an embattled minority, southern elites long succeeded in harnessing national ideals and federal power to their own interests. Thus, defense of slavery was neither inevitably nor invariably secessionist. This is a key theme of Robert Bonner's expertly crafted history of the rise and fall of proslavery American nationalism. Adopting a long-sectional-conflict perspective, Bonner challenges historians who have “conflate[d] an understandable revulsion at proslavery ideology with a willful disassociation of bondage from prevailing American norms.” He details the efforts of proslavery southerners to integrate slavery into national identity and policy and to harmonize slaveholding with American expansionism, republicanism, constitutionalism, and evangelicalism. Appropriating the quintessentially American sense of national purpose, proslavery nationalists “invited outsiders to consider [slavery's] compatibility with broadly shared notions of American values and visions of a globally redeeming national mission.” This effort ended in defeat, but not because proslavery southerners chronically privileged separatism over nationalism. Rather, it was their failure to bind slavery to American nationalism—signaled by the Republican triumph in 1860—that finally drove slaveholders to secede. Lincoln's victory “effectively ended the prospects for achieving proslavery Americanism within the federal Union,” forcing slavery's champions to pin their hopes to a new nation-state. Confederate nationalism was more a response to the demise of proslavery American nationalism than the cause of its death. 21

Other recent studies of slaveholders' efforts to nationalize their goals and interests complement Bonner's skilled analysis. Matthew J. Karp casts proslavery politicians not as jumpy sectionalists but as confident imperialists who sponsored an ambitious and costly expansion of American naval power to protect slavery against foreign encroachment and to exert national influence overseas. For these slaveholding nationalists, “federal power was not a danger to be feared, but a force to be utilized,” right up to the 1860 election. Similarly, Brian Schoen has explored cotton planters' efforts to ensure that national policy on tariff rates and slavery's territorial status remained favorable to their interests. As cotton prices boomed during the 1850s, planters grew richer and the stakes grew higher, especially as their national political power waned with the ascension of the overtly sectional Republican party. The simultaneous increase in planters' economic might and decline in their political dominance made for an explosive mixture that shattered the bonds of the Union. Still, one must not focus solely on cases in which proslavery nationalism was thwarted, for its successes convinced many northerners of the veracity of the slave power thesis, helping further corrode the Union. James L. Huston shows that both southern efforts to nationalize property rights in slaves and the prospect of slavery becoming a national institution—in the sense that a fully integrated national market could bring slave and free labor into competition—fueled northern sectionalism and promoted the rise of the Republican party. Proslavery nationalism and its policy implications thus emboldened the political party whose victory in 1860 convinced proslavery southerners that their goals could not be realized within the Union. 22