An Essay on Man: Epistle I

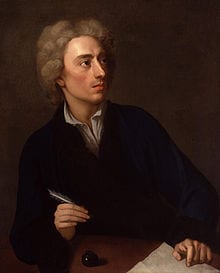

by Alexander Pope

To Henry St. John, Lord Bolingbroke Awake, my St. John! leave all meaner things To low ambition, and the pride of kings. Let us (since life can little more supply Than just to look about us and to die) Expatiate free o’er all this scene of man; A mighty maze! but not without a plan; A wild, where weeds and flow’rs promiscuous shoot; Or garden, tempting with forbidden fruit. Together let us beat this ample field, Try what the open, what the covert yield; The latent tracts, the giddy heights explore Of all who blindly creep, or sightless soar; Eye Nature’s walks, shoot folly as it flies, And catch the manners living as they rise; Laugh where we must, be candid where we can; But vindicate the ways of God to man. I. Say first, of God above, or man below, What can we reason, but from what we know? Of man what see we, but his station here, From which to reason, or to which refer? Through worlds unnumber’d though the God be known, ‘Tis ours to trace him only in our own. He, who through vast immensity can pierce, See worlds on worlds compose one universe, Observe how system into system runs, What other planets circle other suns, What varied being peoples ev’ry star, May tell why Heav’n has made us as we are. But of this frame the bearings, and the ties, The strong connections, nice dependencies, Gradations just, has thy pervading soul Look’d through? or can a part contain the whole? Is the great chain, that draws all to agree, And drawn supports, upheld by God, or thee? II. Presumptuous man! the reason wouldst thou find, Why form’d so weak, so little, and so blind? First, if thou canst, the harder reason guess, Why form’d no weaker, blinder, and no less! Ask of thy mother earth , why oaks are made Taller or stronger than the weeds they shade? Or ask of yonder argent fields above, Why Jove’s satellites are less than Jove? Of systems possible, if ’tis confest That Wisdom infinite must form the best, Where all must full or not coherent be, And all that rises, rise in due degree; Then, in the scale of reas’ning life, ’tis plain There must be somewhere, such a rank as man: And all the question (wrangle e’er so long) Is only this, if God has plac’d him wrong? Respecting man, whatever wrong we call, May, must be right, as relative to all. In human works, though labour’d on with pain, A thousand movements scarce one purpose gain; In God’s, one single can its end produce; Yet serves to second too some other use. So man, who here seems principal alone , Perhaps acts second to some sphere unknown, Touches some wheel, or verges to some goal; ‘Tis but a part we see, and not a whole. When the proud steed shall know why man restrains His fiery course, or drives him o’er the plains: When the dull ox, why now he breaks the clod, Is now a victim, and now Egypt’s God: Then shall man’s pride and dulness comprehend His actions’, passions’, being’s, use and end; Why doing, suff’ring, check’d, impell’d; and why This hour a slave, the next a deity. Then say not man’s imperfect, Heav’n in fault; Say rather, man’s as perfect as he ought: His knowledge measur’d to his state and place, His time a moment, and a point his space. If to be perfect in a certain sphere, What matter, soon or late, or here or there? The blest today is as completely so, As who began a thousand years ago. III. Heav’n from all creatures hides the book of fate, All but the page prescrib’d, their present state: From brutes what men, from men what spirits know: Or who could suffer being here below? The lamb thy riot dooms to bleed today, Had he thy reason, would he skip and play ? Pleas’d to the last, he crops the flow’ry food, And licks the hand just rais’d to shed his blood. Oh blindness to the future! kindly giv’n, That each may fill the circle mark’d by Heav’n: Who sees with equal eye, as God of all, A hero perish, or a sparrow fall, Atoms or systems into ruin hurl’d, And now a bubble burst, and now a world. Hope humbly then; with trembling pinions soar; Wait the great teacher Death; and God adore! What future bliss, he gives not thee to know, But gives that hope to be thy blessing now. Hope springs eternal in the human breast: Man never is, but always to be blest: The soul, uneasy and confin’d from home, Rests and expatiates in a life to come. Lo! the poor Indian, whose untutor’d mind Sees God in clouds, or hears him in the wind; His soul, proud science never taught to stray Far as the solar walk, or milky way; Yet simple nature to his hope has giv’n, Behind the cloud -topt hill, an humbler heav’n; Some safer world in depth of woods embrac’d, Some happier island in the wat’ry waste, Where slaves once more their native land behold, No fiends torment, no Christians thirst for gold. To be, contents his natural desire, He asks no angel’s wing, no seraph’s fire; But thinks, admitted to that equal sky, His faithful dog shall bear him company. IV. Go, wiser thou! and, in thy scale of sense Weigh thy opinion against Providence; Call imperfection what thou fanciest such, Say, here he gives too little, there too much: Destroy all creatures for thy sport or gust, Yet cry, if man’s unhappy, God’s unjust; If man alone engross not Heav’n’s high care, Alone made perfect here, immortal there: Snatch from his hand the balance and the rod, Rejudge his justice , be the God of God. In pride, in reas’ning pride, our error lies; All quit their sphere, and rush into the skies. Pride still is aiming at the blest abodes, Men would be angels, angels would be gods. Aspiring to be gods, if angels fell, Aspiring to be angels, men rebel: And who but wishes to invert the laws Of order, sins against th’ Eternal Cause. V. ask for what end the heav’nly bodies shine, Earth for whose use? Pride answers, ” ‘Tis for mine: For me kind Nature wakes her genial pow’r, Suckles each herb, and spreads out ev’ry flow’r; Annual for me, the grape, the rose renew, The juice nectareous, and the balmy dew; For me, the mine a thousand treasures brings; For me, health gushes from a thousand springs; Seas roll to waft me, suns to light me rise; My foot -stool earth, my canopy the skies.” But errs not Nature from this gracious end, From burning suns when livid deaths descend, When earthquakes swallow, or when tempests sweep Towns to one grave, whole nations to the deep? “No, (’tis replied) the first Almighty Cause Acts not by partial, but by gen’ral laws; Th’ exceptions few; some change since all began: And what created perfect?”—Why then man? If the great end be human happiness, Then Nature deviates; and can man do less? As much that end a constant course requires Of show’rs and sunshine, as of man’s desires; As much eternal springs and cloudless skies, As men for ever temp’rate, calm, and wise. If plagues or earthquakes break not Heav’n’s design , Why then a Borgia, or a Catiline? Who knows but he, whose hand the lightning forms, Who heaves old ocean, and who wings the storms, Pours fierce ambition in a Cæsar’s mind, Or turns young Ammon loose to scourge mankind? From pride, from pride, our very reas’ning springs; Account for moral , as for nat’ral things: Why charge we Heav’n in those, in these acquit? In both, to reason right is to submit. Better for us, perhaps, it might appear, Were there all harmony, all virtue here; That never air or ocean felt the wind; That never passion discompos’d the mind. But ALL subsists by elemental strife; And passions are the elements of life. The gen’ral order, since the whole began, Is kept in nature, and is kept in man. VI. What would this man? Now upward will he soar, And little less than angel, would be more; Now looking downwards, just as griev’d appears To want the strength of bulls, the fur of bears. Made for his use all creatures if he call, Say what their use, had he the pow’rs of all? Nature to these, without profusion, kind, The proper organs, proper pow’rs assign’d; Each seeming want compensated of course, Here with degrees of swiftness, there of force; All in exact proportion to the state; Nothing to add, and nothing to abate. Each beast, each insect, happy in its own: Is Heav’n unkind to man, and man alone? Shall he alone, whom rational we call, Be pleas’d with nothing, if not bless’d with all? The bliss of man (could pride that blessing find) Is not to act or think beyond mankind; No pow’rs of body or of soul to share, But what his nature and his state can bear. Why has not man a microscopic eye? For this plain reason, man is not a fly. Say what the use, were finer optics giv’n, T’ inspect a mite, not comprehend the heav’n? Or touch, if tremblingly alive all o’er, To smart and agonize at ev’ry pore? Or quick effluvia darting through the brain, Die of a rose in aromatic pain? If nature thunder’d in his op’ning ears, And stunn’d him with the music of the spheres, How would he wish that Heav’n had left him still The whisp’ring zephyr, and the purling rill? Who finds not Providence all good and wise, Alike in what it gives, and what denies? VII. Far as creation’s ample range extends, The scale of sensual, mental pow’rs ascends: Mark how it mounts, to man’s imperial race, From the green myriads in the peopled grass : What modes of sight betwixt each wide extreme, The mole’s dim curtain, and the lynx’s beam: Of smell, the headlong lioness between, And hound sagacious on the tainted green: Of hearing, from the life that fills the flood, To that which warbles through the vernal wood: The spider’s touch, how exquisitely fine! Feels at each thread, and lives along the line: In the nice bee, what sense so subtly true From pois’nous herbs extracts the healing dew: How instinct varies in the grov’lling swine, Compar’d, half-reas’ning elephant, with thine: ‘Twixt that, and reason, what a nice barrier; For ever sep’rate, yet for ever near! Remembrance and reflection how allied; What thin partitions sense from thought divide: And middle natures, how they long to join, Yet never pass th’ insuperable line! Without this just gradation, could they be Subjected, these to those, or all to thee? The pow’rs of all subdu’d by thee alone, Is not thy reason all these pow’rs in one? VIII. See, through this air, this ocean, and this earth, All matter quick, and bursting into birth. Above, how high, progressive life may go! Around, how wide! how deep extend below! Vast chain of being, which from God began, Natures ethereal, human, angel, man, Beast, bird, fish, insect! what no eye can see, No glass can reach! from infinite to thee, From thee to nothing!—On superior pow’rs Were we to press, inferior might on ours: Or in the full creation leave a void, Where, one step broken, the great scale’s destroy’d: From nature’s chain whatever link you strike, Tenth or ten thousandth, breaks the chain alike. And, if each system in gradation roll Alike essential to th’ amazing whole, The least confusion but in one, not all That system only, but the whole must fall. Let earth unbalanc’d from her orbit fly, Planets and suns run lawless through the sky; Let ruling angels from their spheres be hurl’d, Being on being wreck’d, and world on world; Heav’n’s whole foundations to their centre nod, And nature tremble to the throne of God. All this dread order break—for whom? for thee? Vile worm!—Oh madness, pride, impiety! IX. What if the foot ordain’d the dust to tread, Or hand to toil, aspir’d to be the head? What if the head, the eye, or ear repin’d To serve mere engines to the ruling mind? Just as absurd for any part to claim To be another, in this gen’ral frame: Just as absurd, to mourn the tasks or pains, The great directing Mind of All ordains. All are but parts of one stupendous whole, Whose body Nature is, and God the soul; That, chang’d through all, and yet in all the same, Great in the earth, as in th’ ethereal frame, Warms in the sun, refreshes in the breeze, Glows in the stars, and blossoms in the trees , Lives through all life, extends through all extent, Spreads undivided, operates unspent, Breathes in our soul, informs our mortal part, As full, as perfect, in a hair as heart; As full, as perfect, in vile man that mourns, As the rapt seraph that adores and burns; To him no high, no low, no great, no small; He fills, he bounds, connects, and equals all. X. Cease then, nor order imperfection name: Our proper bliss depends on what we blame. Know thy own point: This kind, this due degree Of blindness, weakness, Heav’n bestows on thee. Submit.—In this, or any other sphere, Secure to be as blest as thou canst bear: Safe in the hand of one disposing pow’r, Or in the natal, or the mortal hour. All nature is but art, unknown to thee; All chance, direction, which thou canst not see; All discord, harmony, not understood; All partial evil, universal good: And, spite of pride, in erring reason’s spite, One truth is clear, Whatever is, is right.

Summary of An Essay on Man: Epistle I

- Popularity of “An Essay on Man: Epistle I”: Alexander Pope, one of the greatest English poets, wrote ‘An Essay on Man’ It is a superb literary piece about God and creation, and was first published in 1733. The poem speaks about the mastery of God’s art that everything happens according to His plan, even though we fail to comprehend His work. It also illustrates man’s place in the cosmos. The poet explains God’s grandeur and His rule over the universe.

- “An Essay on Man: Epistle I” As a Representative of God’s Art: This poem explains God’s ways to men. This is a letter to the poet’s friend, St. John, Lord Bolingbroke. He urges him to quit all his mundane tasks and join the speaker to vindicate the ways of God to men. The speaker argues that God may have other worlds to observe but man perceives the world with his own limited system. A man’s happiness depends on two basic things; his hopes for the future and unknown future events. While talking about the sinful and impious nature of mankind, the speaker argues that man’s attempt to gain more knowledge and to put himself at God’s place becomes the reason of his discontent and constant misery. In section 1, the poet argues that man knows about the universe with his/her limited knowledge and cannot understand the systems and constructions of God. Humans are unaware of the grander relationships between God and His creations. In section 2, he states that humans are not perfect. However, God designed humans perfectly to suit his plan, in the order of the creation of things. Humans are after angelic beings but above every creature on the planet. In section 3 the poet tells that human happiness depends on both his lack of knowledge as they don’t know the future and also on his hope for the future. In section 4 the poet talks about the pride of humans, which is a sin. Because of pride, humans try to gain more knowledge and pretend that is a perfect creation. This pride is the root of man’s mistakes and sorrow. If humans put themselves in God’s place, then humans are sinners. In section 5, the poet explains the meaninglessness of human beliefs. He thinks that it is extremely ridiculous to believe that humans are the sole cause of creation. God expecting perfection and morality from people on this earth does not happen in the natural world. In section 6, the poet criticizes human nature because of the unreasonable demands and complaints against God and His providence. He argues that God is always good; He loves giving and taking. We also learn that if man possesses the knowledge of God, he would be miserable. In section 7, he shows that the natural world we see, including the universal order and degree, is observable by humans as per their perspective . The hierarchy of humans over earthly creatures and their subordination to man is one of the examples. The poet also mentions sensory issues like physical sense, instinct, thought, reflection, and reason. There’s also a reason which is above everything. In section 8, the poet reclaims that if humans break God’s rules of order and fail to obey are broken, then the entire God’s creation must also be destroyed. In section 9, he talks about human craziness and the desire to overthrow God’s order and break all the rules. In the last section the speaker requests and invites humans to submit to God and His power to follow his order. When humans submit to God’s absolute submission, His will, and ensure to do what’s right, then human remains safe in God’s hand.

- Major Themes in “An Essay on Man: Epistle I”: Acceptance, God’s superiority, and man’s nature are the major themes of this poem Throughout the poem, the speaker tries to justify the working of God, believing there is a reason behind all things. According to the speaker, a man should not try to examine the perfection and imperfection of any creature. Rather, he should understand the purpose of his own existence in the world. He should acknowledge that God has created everything according to his plan and that man’s narrow intellectual ability can never be able to comprehend the greater logic of God’s order.

Analysis of Literary Devices Used in “An Essay on Man: Epistle I”

literary devices are modes that represent writers’ ideas, feelings, and emotions. It is through these devices the writers make their few words appealing to the readers. Alexander Pope has also used some literary devices in this poem to make it appealing. The analysis of some of the literary devices used in this poem has been listed below.

- Assonance : Assonance is the repetition of vowel sounds in the same line. For example, the sound of /o/ in “To him no high, no low, no great, no small” and the sound of /i/ in “The whisp’ring zephyr, and the purling rill?”

- Anaphora : It refers to the repetition of a word or expression in the first part of some verses. For example, “As full, as perfect,” in the second last stanza of the poem to emphasize the point of perfection.

- Alliteration : Alliteration is the repetition of consonant sounds in the same line in quick succession. For example, the sound of /m/ in “A mighty maze! but not without a plan”, the sound of /b/ “And now a bubble burst, and now a world” and the sound of /th/ in “Subjected, these to those, or all to thee.”

- Enjambment : It is defined as a thought in verse that does not come to an end at a line break ; instead, it rolls over to the next line. For example.

“Lo! the poor Indian, whose untutor’d mind Sees God in clouds, or hears him in the wind.”

- Imagery : Imagery is used to make readers perceive things involving their five senses. For example, “All chance, direction, which thou canst not see”, “Planets and suns run lawless through the sky” and “Where, one step broken, the great scale’s destroy’d”

- Rhetorical Question : Rhetorical question is a question that is not asked in order to receive an answer; it is just posed to make the point clear and to put emphasis on the speaker’s point. For example, “Why has not man a microscopic eye?”, “And what created perfect?”—Why then man?” and “What matter, soon or late, or here or there?”

Analysis of Poetic Devices Used in “An Essay on Man: Epistle I”

Poetic and literary devices are the same, but a few are used only in poetry. Here is the analysis of some of the poetic devices used in this poem.

- Heroic Couplet : There are two constructive lines in heroic couplet joined by end rhyme in iambic pentameter . For example,

“And, spite of pride, in erring reason’s spite, One truth is clear, Whatever is, is right.”

- Rhyme Scheme : The poem follows the ABAB rhyme scheme and this pattern continues till the end.

- Stanza : A stanza is a poetic form of some lines. This is a long poem divided into ten sections and each section contains different numbers of stanzas in it.

Quotes to be Used

The lines stated below are useful to put in a speech delivered on the topic of God’s grandeur. These are also useful for children to make them understand that we constitute just a part of the whole.

“ All nature is but art, unknown to thee; All chance, direction, which thou canst not see; All discord, harmony, not understood; All partial evil, universal good.”

Related posts:

- Eloisa to Abelard

- My Last Duchess

- Ode to a Nightingale

- A Red, Red Rose

- I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

- The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

- Death, Be Not Proud

- “Hope” is the Thing with Feathers

- I Heard a Fly Buzz When I Died

- I Carry Your Heart with Me

- The Second Coming

- Ode on a Grecian Urn

- A Visit from St. Nicholas

- The Owl and the Pussy-Cat

- A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning

- God’s Grandeur

- A Psalm of Life

- To His Coy Mistress

- Ode to the West Wind

- Miniver Cheevy

- The Tide Rises, the Tide Falls

- Not Waving but Drowning

- Thanatopsis

- Home Burial

- The Passionate Shepherd to His Love

- Nothing Gold Can Stay

- In the Bleak Midwinter

- The Chimney Sweeper

- Still I Rise

- See It Through

- The Arrow and the Song

- The Emperor of Ice-Cream

- To an Athlete Dying Young

- Success is Counted Sweetest

- Lady Lazarus

- The Twelve Days of Christmas

- On Being Brought from Africa to America

- Jack and Jill

- Much Madness is Divinest Sense

- Little Boy Blue

- On the Pulse of Morning

- Theme for English B

- From Endymion

- Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird

- Insensibility

- The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

- A Bird, Came Down the Walk

- To My Mother

- In the Desert

- Neutral Tones

- Blackberry-Picking

- Some Keep the Sabbath Going to Church

- On My First Son

- We Are Seven

- Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood

- Sonnet 55: Not Marble nor the Gilded Monuments

- There’s a Certain Slant of Light

- To a Skylark

- The Haunted Palace

- Buffalo Bill’s

- Arms and the Boy

- The Children’s Hour

- In Memoriam A. H. H. OBIIT MDCCCXXXIII: 27

- New Year’s Day

- Love Among The Ruins

- She Dwelt Among the Untrodden Ways

- This Is Just To Say

- To — — –. Ulalume: A Ballad

- Who Has Seen the Wind?

- The Landlord’s Tale. Paul Revere’s Ride

- The Chambered Nautilus

- The Wild Swans at Coole

- The Hunting of the Snark

Post navigation

Pope's Poems and Prose

By alexander pope, pope's poems and prose summary and analysis of an essay on man: epistle ii.

The subtitle of the second epistle is “Of the Nature and State of Man, with Respect to Himself as an Individual” and treats on the relationship between the individual and God’s greater design.

Here is a section-by-section explanation of the second epistle:

Section I (1-52): Section I argues that man should not pry into God’s affairs but rather study himself, especially his nature, powers, limits, and frailties.

Section II (53-92): Section II shows that the two principles of man are self-love and reason. Self-love is the stronger of the two, but their ultimate goal is the same.

Section III (93-202): Section III describes the modes of self-love (i.e., the passions) and their function. Pope then describes the ruling passion and its potency. The ruling passion works to provide man with direction and defines man’s nature and virtue.

Section IV (203-16): Section IV indicates that virtue and vice are combined in man’s nature and that the two, while distinct, often mix.

Section V (217-30): Section V illustrates the evils of vice and explains how easily man is drawn to it.

Section VI (231-294): Section VI asserts that man’s passions and imperfections are simply designed to suit God’s purposes. The passions and imperfections are distributed to all individuals of each order of men in all societies. They guide man in every state and at every age of life.

The second epistle adds to the interpretive challenges presented in the first epistle. At its outset, Pope commands man to “Know then thyself,” an adage that misdescribes his argument (1). Although he actually intends for man to better understand his place in the universe, the classical meaning of “Know thyself” is that man should look inwards for truth rather than outwards. Having spent most of the first epistle describing man’s relationship to God as well as his fellow creatures, Pope’s true meaning of the phrase is clear. He then confuses the issue by endeavoring to convince man to avoid the presumptuousness of studying God’s creation through natural science. Science has given man the tools to better understand God’s creation, but its intoxicating power has caused man to imitate God. It seems that man must look outwards to gain any understanding of his divine purpose but avoid excessive analysis of what he sees. To do so would be to assume the role of God.

The second epistle abruptly turns to focus on the principles that guide human action. The rest of this section focuses largely on “self-love,” an eighteenth-century term for self-maintenance and fulfillment. It was common during Pope’s lifetime to view the passions as the force determining human action. Typically instinctual, the immediate object of the passions was seen as pleasure. According to Pope’s philosophy, each man has a “ruling passion” that subordinates the others. In contrast with the accepted eighteenth-century views of the passions, Pope’s doctrine of the “ruling passion” is quite original. It seems clear that with this idea, Pope tries to explain why certain individual behave in distinct ways, seemingly governed by a particular desire. He does not, however, make this explicit in the poem.

Pope’s discussion of the passions shows that “self-love” and “reason” are not opposing principles. Reason’s role, it seems, is to regulate human behavior while self-love originates it. In another sense, self-love and the passions dictate the short term while reason shapes the long term.

Pope’s Poems and Prose Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Pope’s Poems and Prose is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

The Rape of the Lock

In Canto I, a dream is sent to Belinda by Ariel, “her guardian Sylph” (20). The Sylphs are Belinda’s guardians because they understand her vanity and pride, having been coquettes when they were humans. They are devoted to any woman who “rejects...

Who delivers the moralizing speech on the frailty of beauty? A. Chloe B. Clarissa C. Ariel D. Thalestris

What is the significance of Belinda's petticoat?

Did you answer this?

Study Guide for Pope’s Poems and Prose

Pope's Poems and Prose study guide contains a biography of Alexander Pope, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About Pope's Poems and Prose

- Pope's Poems and Prose Summary

- Character List

Essays for Pope’s Poems and Prose

Pope's Poems and Prose essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of Alexander Pope's Poems and Prose.

- Of the Characteristics of Pope

- Breaking Clod: Hierarchical Transformation in Pope's An Essay on Man

- Fortasse, Pope, Idcirco Nulla Tibi Umquam Nupsit (The Rape of the Lock)

- An Exploration of 'Dulness' In Pope's Dunciad

- Belinda: Wronged On Behalf of All Women

Wikipedia Entries for Pope’s Poems and Prose

- Introduction

- Translations and editions

- Spirit, skill and satire

British Literature Wiki

An Essay on Man

“Is the great chain, that draws all to agree, And drawn supports, upheld by God, or Thee?” – Alexander Pope (From “An Essay on Man”)

“Then say not Man’s imperfect, Heav’n in fault; Say rather, Man’s as perfect as he ought.” – Alexander Pope (From “An Essay on Man”)

“All are but parts of one stupendous whole, Whose body Nature is, and God the soul.” – Alexander Pope (From “An Essay on Man”)

Awake, my St. John! leave all meaner things

To low ambition, and the pride of kings., let us (since life can little more supply, than just to look about us and die), expatiate free o’er all this scene of man;, a mighty maze but not without a plan;, a wild, where weed and flow’rs promiscuous shoot;, or garden, tempting with forbidden fruit., together let us beat this ample field,, try what the open, what the covert yield;, the latent tracts, the giddy heights explore, of all who blindly creep, or sightless soar;, eye nature’s walks, shoot folly as it flies,, and catch the manners living as they rise;, laugh where we must, be candid where we can;, but vindicate the ways of god to man. (pope 1-16), background on alexander pope.

Alexander Pope is a British poet who was born in London, England in 1688 (World Biography 1). Growing up during the Augustan Age, his poetry is heavily influenced by common literary qualities of that time, which include classical influence, the importance of human reason and the rules of nature. These qualities are widely represented in Pope’s poetry. Some of Pope’s most notable works are “The Rape of the Lock,” “An Essay on Criticism,” and “An Essay on Man.”

Overview of “An Essay on Man”

“An Essay on Man” was published in 1734 and contained very deep and well thought out philosophical ideas. It is said that these ideas were partially influenced by his friend, Henry St. John Bolingbroke, who Pope addresses in the first line of Epistle I when he says, “Awake, my St. John!”(Pope 1)(World Biography 1) The purpose of the poem is to address the role of humans as part of the “Great Chain of Being.” In other words, it speaks of man as just one small part of an unfathomably complex universe. Pope urges us to learn from what is around us, what we can observe ourselves in nature, and to not pry into God’s business or question his ways; For everything that happens, both good and bad, happens for a reason. This idea is summed up in the very last lines of the poem when he says, “And, Spite of pride in erring reason’s spite, / One truth is clear, Whatever IS, is RIGHT.”(Pope 293-294) The poem is broken up into four epistles each of which is labeled as its own subcategory of the overall work. They are as follows:

- Epistle I – Of the Nature and State of Man, with Respect to the Universe

- Epistle II – Of the Nature and State of Man, with Respect to Himself, as an Individual

- Epistle III – Of the Nature and State of Man, with Respect to Society

- Epistle IV – Of the Nature and State of Man with Respect to Happiness

Epistle 1 Intro In the introduction to Pope’s first Epistle, he summarizes the central thesis of his essay in the last line. The purpose of “An Essay on Man” is then to shift or enhance the reader’s perception of what is natural or correct. By doing this, one would justify the happenings of life, and the workings of God, for there is a reason behind all things that is beyond human understanding. Pope’s endeavor to highlight the infallibility of nature is a key aspect of the Augustan period in literature; a poet’s goal was to convey truth by creating a mirror image of nature. This is envisaged in line 13 when, keeping with the hunting motif, Pope advises his reader to study the behaviors of Nature (as hunter would watch his prey), and to rid of all follies, which we can assume includes all that is unnatural. He also encourages the exploration of one’s surroundings, which provides for a gateway to new discoveries and understandings of our purpose here on Earth. Furthermore, in line 12, Pope hints towards vital middle ground on which we are above beats and below a higher power(s). Those who “blindly creep” are consumed by laziness and a willful ignorance, and just as bad are those who “sightless soar” and believe that they understand more than they can possibly know. Thus, it is imperative that we can strive to gain knowledge while maintaining an acceptance of our mental limits.

1. Pope writes the first section to put the reader into the perspective that he believes to yield the correct view of the universe. He stresses the fact that we can only understand things based on what is around us, embodying the relationship with empiricism that characterizes the Augustan era. He encourages the discovery of new things while remaining within the bounds one has been given. These bounds, or the Chain of Being, designate each living thing’s place in the universe, and only God can see the system in full. Pope is adamant in God’s omniscience, and uses that as a sure sign that we can never reach a level of knowledge comparable to His. In the last line however, he questions whether God or man plays a bigger role in maintaining the chain once it is established.

2. The overarching message in section two is envisaged in one of the last couplets: “Then say not Man’s imperfect, Heav’n in fault; Say rather, Man’s as perfect as he ought.” Pope utilizes this section to explain the folly of “Presumptuous Man,” for the fact that we tend to dwell on our limitations rather than capitalize on our abilities. He emphasizes the rightness of our place in the chain of being, for just as we steer the lives of lesser creatures, God has the ability to pilot our fate. Furthermore, he asserts that because we can only analyze what is around us, we cannot be sure that there is not a greater being or sphere beyond our level of comprehension; it is most logical to perceive the universe as functioning through a hierarchal system.

3. Pope utilizes the beginning of section three to elaborate on the functions of the chain of being. He claims that each creatures’ ignorance, including our own, allows for a full and happy life without the possible burden of understanding our fates. Instead of consuming ourselves with what we cannot know, we instead should place hope in a peaceful “life to come.” Pope connects this after-life to the soul, and colors it with a new focus on a more primitive people, “the Indian,” whose souls have not been distracted by power or greed. As humble and level headed beings, Indian’s, and those who have similar beliefs, see life as the ultimate gift and have no vain desires of becoming greater than Man ought to be.

4. In the fourth stanza, Pope warns against the negative effects of excessive pride. He places his primary examples in those who audaciously judge the work of God and declare one person to be too fortunate and another not fortunate enough. He also satirizes Man’s selfish content in destroying other creatures for his own benefit, while complaining when they believe God to be unjust to Man. Pope capitalizes on his point with the final and resonating couplet: “who but wishes to invert the laws of order, sins against th’ Eternal Cause.” This connects to the previous stanza in which the soul is explored; those who wrestle with their place in the universe will disturb the chain of being and warrant punishment instead of gain rewards in the after-life.

5. In the beginning of the fifth stanza, Pope personifies Pride and provides selfish answers to questions regarding the state of the universe. He depicts Pride as a hoarder of all gifts that Nature yields. The image of Nature as a benefactor and Man as her avaricious recipient is countered in the next set of lines: Pope instead entertains the possible faults of Nature in natural disasters such as earthquakes and storms. However, he denies this possibility on the grounds that there is a larger purpose behind all happenings and that God acts by “general laws.” Finally, Pope considers the emergence of evil in human nature and concludes that we are not in a place that allows us to explain such things–blaming God for human misdeeds is again an act of pride.

6. Stanza six connects the different inhabitants of the earth to their rightful place and shows why things are the way they should be. After highlighting the happiness in which most creatures live, Pope facetiously questions if God is unkind to man alone. He asks this because man consistently yearns for the abilities specific to those outside of his sphere, and in that way can never be content in his existence. Pope counters the notorious greed of Man by illustrating the pointless emptiness that would accompany a world in which Man was omnipotent. Furthermore, he describes a blissful lifestyle as one centered around one’s own sphere, without the distraction of seeking unattainable heights.

7. The seventh stanza explores the vastness of the sensory and cognitive spectrums in relation to all earthly creatures. Pope uses an example related to each of the five senses to conjure an image that emphasizes the intricacies with which all things are tailored. For instance, he references a bee’s sensitivity, which allows it to collect only that which is beneficial amid dangerous substances. Pope then moves to the differences in mental abilities along the chain of being. These mental functions are broken down into instinct, reflection, memory, and reason. Pope believes reason to trump all, which of course is the one function specific to Man. Reason thus allows man to synthesize the means to function in ways that are unnatural to himself.

8. In section 8 Pope emphasizes the depths to which the universe extends in all aspects of life. This includes the literal depths of the ocean and the reversed extent of the sky, as well as the vastness that lies between God and Man and Man and the simpler creatures of the earth. Regardless of one’s place in the chain of being however, the removal of one link creates just as much of an impact as any other. Pope stresses the maintenance of order so as to prevent the breaking down of the universe.

9. In the ninth stanza, Pope once again puts the pride and greed of man into perspective. He compares man’s complaints of being subordinate to God to an eye or an ear rejecting its service to the mind. This image drives home the point that all things are specifically designed to ensure that the universe functions properly. Pope ends this stanza with the Augustan belief that Nature permeates all things, and thus constitutes the body of the world, where God characterizes the soul.

10. In the tenth stanza, Pope secures the end of Epistle 1 by advising the reader on how to secure as many blessings as possible, whether that be on earth or in the after life. He highlights the impudence in viewing God’s order as imperfect and emphasizes the fact that true bliss can only be experienced through an acceptance of one’s necessary weaknesses. Pope exemplifies this acceptance of weakness in the last lines of Epistle 1 in which he considers the incomprehensible, whether seemingly miraculous or disastrous, to at least be correct, if nothing else.

1. Epistle II is broken up into six smaller sections, each of which has a specific focus. The first section explains that man must not look to God for answers to the great questions of life, for he will never find the answers. As was explained in the first epistle, man is incapable of truly knowing anything about the things that are higher than he is on the “Great Chain of Being.” For this reason, the way to achieve the greatest knowledge possible is to study man, the greatest thing we have the ability to comprehend. Pope emphasizes the complexity of man in an effort to show that understanding of anything greater than that would simply be too much for any person to fully comprehend. He explains this complexity with lines such as, “Created half to rise, and half to fall; / Great lord of all things, yet a prey to all / Sole judge of truth, in endless error hurl’d: / The glory, jest, and riddle of the world!”(15-18) These lines say that we are created for two purposes, to live and die. We are the most intellectual creatures on Earth, and while we have control over most things, we are still set up to die in some way by the end. We are a great gift of God to the Earth with enormous capabilities, yet in the end we really amount to nothing. Pope describes this contrast between our intellectual capabilities and our inevitable fate as a “riddle” of the world. The first section of Epistle II closes by saying that man is to go out and study what is around him. He is to study science to understand all that he can about his existence and the universe in which he lives, but to fully achieve this knowledge he must rid himself of all vices that may slow down this process.

2. The second section of Epistle II tells of the two principles of human nature and how they are to perfectly balance each other out in order for man to achieve all that he is capable of achieving. These two principles are self-love and reason. He explains that all good things can be attributed to the proper use of these two principles and that all bad things stem from their improper use. Pope further discusses the two principles by claiming that self-love is what causes man to do what he desires, but reason is what allows him to know how to stay in line. He follows that with an interesting comparison of man to a flower by saying man is “Fix’d like a plant on his peculiar spot, / To draw nutrition, propagate and rot,” (Pope 62-63) and also of man to a meteor by saying, “Or, meteor-like, flame lawless thro’ the void, / Destroying others, by himself destroy’d.” (Pope 64-65) These comparisons show that man, according to Pope, is born, takes his toll on the Earth, and then dies, and it is all part of a larger plan. The rest of section two continues to talk about the relationship between self-love and reason and closes with a strong argument. Humans all seek pleasure, but only with a good sense of reason can they restrain themselves from becoming greedy. His final remarks are strong, stating that, “Pleasure, or wrong or rightly understood, / Our greatest evil, or our greatest good,”(Pope 90-91) which means that pleasure in moderation can be a great thing for man, but without the balance that reason produces, a pursuit of pleasure can have terrible consequences.

3. Part III of Epistle II also pertains to the idea of self-love and reason working together. It starts out talking about passions and how they are inherently selfish, but if the means to which these passions are sought out are fair, then there has been a proper balance of self-love and reason. Pope describes love, hope and joy as being “Fair treasure’s smiling train,”(Pope 117) while hate, fear and grief are “The family of pain.”(Pope 118) Too much of any of these things, whether they be from the negative or positive side, is a bad thing. There is a ratio of good to bad that man must reach to have a well balanced mind. We learn, grow, and gain character and perspective through the elements of this “Family of pain,”(Pope 118) while we get great rewards from love, hope and joy. While our goal as humans is to seek our pleasure and follow certain desires, there is always one overall passion that lives deep within us that guides us throughout life. The main points to take away from Section III of this Epistle is that there are many aspects to the life of man, and these aspects, both positive and negative, need to coexist harmoniously to achieve that balance for which man should strive.

4. The fourth section of Epistle II is very short. It starts off by asking what allows us to determine the difference between good and bad. The next line answers this question by saying that it is the God within our minds that allows us to make such judgements. This section finishes up by discussing virtue and vice. The relationship between these two qualities are interesting, for they can exist on their own but most often mix, and there is a fine line between something being a virtue and becoming a vice.

5. Section V is even shorter than section IV with just fourteen lines. It speaks only of the quality of vice. Vices are temptations that man must face on a consistent basis. A line that stands out from this says that when it comes to vices, “We first endure, then pity, then embrace.”(Pope 218) This means that vices start off as something we know is wrong, but over time they become an instinctive part of us if reason is not there to push them away.

6. Section VI, the final section of Epistle II, relates many of the ideas from Sections I-V back to ideas from Epistle I. It works as a conclusion that ties in the main theme of Epistle II, which mainly speaks of the different components of man that balance each other out to form an infinitely complex creature, into the idea from Epistle I that man is created as part of a larger plan with all of his qualities given to him for a specific purpose. It is a way of looking at both negative and positive aspects of life and being content with them both, for they are all part of God’s purpose of creating the universe. This idea is well concluded in the third to last line of this Epistle when Pope says, “Ev’n mean self-love becomes, by force divine.”(Pope 288) This shows that even a negative quality in a man, such as excessive self-love without the stability of reason, is technically divine, for it is what God intended as part of the balance of the universe.

Contributors

- Dan Connolly

- Nicole Petrone

“Alexander Pope.” : The Poetry Foundation . N.p., n.d. Web. 14 May 2013. < http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/alexander-pope >.

“Alexander Pope Photos.” Rugu RSS . N.p., n.d. Web. 14 May 2013. < http://www.rugusavay.com/alexander-pope-photos/ >.

“An Essay on Man: Epistle 1 by Alexander Pope • 81 Poems by Alexander PopeEdit.” An Essay on Man: Epistle 1 by Alexander Pope Classic Famous Poet . N.p., n.d. Web. 14 May 2013. < http://allpoetry.com/poem/8448567-An_Essay_on_Man_Epistle_1-by-Alexander_Pope >.

“An Essay on Man: Epistle II.” By Alexander Pope : The Poetry Foundation. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 May 2013. < http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/174166 >.

“Benjamin Franklin’s Mastodon Tooth.” About.com Archaeology . N.p., n.d. Web. 14 May 2013. < http://archaeology.about.com/od/artandartifacts/ss/franklin_4.htm >.

“First Edition of An Essay on Man by Alexander Pope Offered by The Manhattan Rare Book Company.” First Edition of An Essay on Man by Alexander Pope Offered by The Manhattan Rare Book Company. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 May 2013. < http://www.manhattanrarebooks- literature.com/pope_essay.htm>.

Alexander Pope's Essay on Man: An Introduction

David cody , associate professor of english, hartwick college.

Victorian Web Home —> Some Pre-Victorian Authors —> Neoclassicism —> Alexander Pope ]

The Essay on Man is a philosophical poem, written, characteristically, in heroic couplets , and published between 1732 and 1734. Pope intended it as the centerpiece of a proposed system of ethics to be put forth in poetic form: it is in fact a fragment of a larger work which Pope planned but did not live to complete. It is an attempt to justify, as Milton had attempted to vindicate, the ways of God to Man, and a warning that man himself is not, as, in his pride, he seems to believe, the center of all things. Though not explicitly Christian, the Essay makes the implicit assumption that man is fallen and unregenerate, and that he must seek his own salvation.

The "Essay" consists of four epistles, addressed to Lord Bolingbroke, and derived, to some extent, from some of Bolingbroke's own fragmentary philosophical writings, as well as from ideas expressed by the deistic third Earl of Shaftesbury. Pope sets out to demonstrate that no matter how imperfect, complex, inscrutable, and disturbingly full of evil the Universe may appear to be, it does function in a rational fashion, according to natural laws; and is, in fact, considered as a whole, a perfect work of God. It appears imperfect to us only because our perceptions are limited by our feeble moral and intellectual capacity. His conclusion is that we must learn to accept our position in the Great Chain of Being — a "middle state," below that of the angels but above that of the beasts — in which we can, at least potentially, lead happy and virtuous lives.

Epistle I concerns itself with the nature of man and with his place in the universe; Epistle II, with man as an individual; Epistle III, with man in relation to human society, to the political and social hierarchies; and Epistle IV, with man's pursuit of happiness in this world. An Essay on Man was a controversial work in Pope's day, praised by some and criticized by others, primarily because it appeared to contemporary critics that its emphasis, in spite of its themes, was primarily poetic and not, strictly speaking, philosophical in any really coherent sense: Dr. Johnson , never one to mince words, and possessed, in any case, of views upon the subject which differed materially from those which Pope had set forth, noted dryly (in what is surely one of the most back-handed literary compliments of all time) that "Never were penury of knowledge and vulgarity of sentiment so happily disguised." It is a subtler work, however, than perhaps Johnson realized: G. Wilson Knight has made the perceptive comment that the poem is not a "static scheme" but a "living organism," (like Twickenham ) and that it must be understood as such.

Considered as a whole, the Essay on Man is an affirmative poem of faith: life seems chaotic and patternless to man when he is in the midst of it, but is in fact a coherent portion of a divinely ordered plan. In Pope's world God exists, and he is benificent: his universe is an ordered place. The limited intellect of man can perceive only a tiny portion of this order, and can experience only partial truths, and hence must rely on hope, which leads to faith. Man must be cognizant of his rather insignificant position in the grand scheme of things: those things which he covets most — riches, power, fame — prove to be worthless in the greater context of which he is only dimly aware. In his place, it is man's duty to strive to be good, even if he is doomed, because of his inherent frailty, to fail in his attempt. Do you find Pope's argument convincing? In what ways can we relate the Essay on Man to works like Swift's Gulliver's Travels , Johnson's "The Vanity of Human Wishes" ( text ), Tennyson's In Memoriam and Eliot's The Wasteland ?

Incorporated in the Victorian Web July 2000

François Voltaire

- Literature Notes

- Alexander Pope's Essay on Man

- Book Summary

- Character List

- Summary and Analysis

- Chapters II-III

- Chapters IV-VI

- Chapters VII-X

- Chapters XI-XII

- Chapters XIII-XVI

- Chapters XVII-XVIII

- Chapter IXX

- Chapters XX-XXIII

- Chapters XXIV-XXVI

- Chapters XXVII-XXX

- Francois Voltaire Biography

- Critical Essays

- The Philosophy of Leibnitz

- Poème Sur Le Désastre De Lisoonne

- Other Sources of Influence

- Structure and Style

- Satire and Irony

- Essay Questions

- Cite this Literature Note

Critical Essays Alexander Pope's Essay on Man

The work that more than any other popularized the optimistic philosophy, not only in England but throughout Europe, was Alexander Pope's Essay on Man (1733-34), a rationalistic effort to justify the ways of God to man philosophically. As has been stated in the introduction, Voltaire had become well acquainted with the English poet during his stay of more than two years in England, and the two had corresponded with each other with a fair degree of regularity when Voltaire returned to the Continent.

Voltaire could have been called a fervent admirer of Pope. He hailed the Essay of Criticism as superior to Horace, and he described the Rape of the Lock as better than Lutrin. When the Essay on Man was published, Voltaire sent a copy to the Norman abbot Du Resnol and may possibly have helped the abbot prepare the first French translation, which was so well received. The very title of his Discours en vers sur l'homme (1738) indicates the extent Voltaire was influenced by Pope. It has been pointed out that at times, he does little more than echo the same thoughts expressed by the English poet. Even as late as 1756, the year in which he published his poem on the destruction of Lisbon, he lauded the author of Essay on Man. In the edition of Lettres philosophiques published in that year, he wrote: "The Essay on Man appears to me to be the most beautiful didactic poem, the most useful, the most sublime that has ever been composed in any language." Perhaps this is no more than another illustration of how Voltaire could vacillate in his attitude as he struggled with the problems posed by the optimistic philosophy in its relation to actual experience. For in the Lisbon poem and in Candide , he picked up Pope's recurring phrase "Whatever is, is right" and made mockery of it: "Tout est bien" in a world filled with misery!

Pope denied that he was indebted to Leibnitz for the ideas that inform his poem, and his word may be accepted. Those ideas were first set forth in England by Anthony Ashley Cowper, Earl of Shaftesbury (1671-1731). They pervade all his works but especially the Moralist. Indeed, several lines in the Essay on Man, particularly in the first Epistle, are simply statements from the Moralist done in verse. Although the question is unsettled and probably will remain so, it is generally believed that Pope was indoctrinated by having read the letters that were prepared for him by Bolingbroke and that provided an exegesis of Shaftesbury's philosophy. The main tenet of this system of natural theology was that one God, all-wise and all-merciful, governed the world providentially for the best. Most important for Shaftesbury was the principle of Harmony and Balance, which he based not on reason but on the general ground of good taste. Believing that God's most characteristic attribute was benevolence, Shaftesbury provided an emphatic endorsement of providentialism.

Following are the major ideas in Essay on Man: (1) a God of infinite wisdom exists; (2) He created a world that is the best of all possible ones; (3) the plenum, or all-embracing whole of the universe, is real and hierarchical; (4) authentic good is that of the whole, not of isolated parts; (5) self-love and social love both motivate humans' conduct; (6) virtue is attainable; (7) "One truth is clear, WHATEVER IS, IS RIGHT." Partial evil, according to Pope, contributes to the universal good. "God sends not ill, if rightly understood." According to this principle, vices, themselves to be deplored, may lead to virtues. For example, motivated by envy, a person may develop courage and wish to emulate the accomplishments of another; and the avaricious person may attain the virtue of prudence. One can easily understand why, from the beginning, many felt that Pope had depended on Leibnitz.

Previous The Philosophy of Leibnitz

Next Poème Sur Le Désastre De Lisoonne

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Alexander Pope — Analysis of “An Essay on Man” by Alexander Pope

Analysis of "An Essay on Man" by Alexander Pope

- Categories: Alexander Pope

About this sample

Words: 779 |

Published: Jul 18, 2018

Words: 779 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3.5 pages / 2123 words

7 pages / 3092 words

2 pages / 964 words

2 pages / 888 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Aphra Behn and Alexander Pope both present various situations of crisis and uprising in their works, Oroonoko and The Rape of the Lock, respectively. Although the nature and intensity of the crisis situations are very different, [...]

The fear of a dystopian future that is explored in both Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis and George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty Four is reflective of the values of the societies at the time and the context of the authors. As [...]

The power of words is enough to control an entire nation. Although many would consider physical power and brute force to be absolute power, George Orwell’s 1984 demonstrates a dystopian society where language is the ultimate [...]

In order for one to exist in a totalitarian society whose government is successful in its control, one must deal on a day-to-day basis with strong persuasion and propaganda. These totalitarian societies have an iron grip on [...]

Problems faced by characters in literature often repeat themselves, and when these characters decide to solve these standard problems, their actions are often more similar than they first appear. This idea is evident when [...]

A government of an ideal society is meant to represent the people. It is the people’s choice to support, to select, and to seize government. The idea of open communication is employed as a way for people to choose the best [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

An Essay on Man

30 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Epistle Summaries & Analyses

Symbols & Motifs

Literary Devices

Further Reading & Resources

Discussion Questions

An Orderly Universe

In “Essay on Man,” the speaker has an optimistic view of the universe: Order and purpose characterize everything that exists and happens. The speaker writes: “Order is heaven’s first law” (Epistle 4, Line 49). The speaker believes that the universe appears disorderly only because humans have a limited view. However, by trying to understand themselves, people hope to gain a greater understanding of the universe as well. The speaker uses a variety of images and metaphors to convey this.

The speaker compares the world to a garden (Epistle 1, Line 16). They allude to the Garden of Eden and, in another alliterative moment, reference the “forbidden fruit” (Epistle 1, Line 8), linking their perspective with that of God looking down upon Eden. Their descriptions emphasize the grand scope of their view and convey their large perspective on human nature and the world.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,350+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,950+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Alexander Pope

An Essay on Criticism

Alexander Pope

Eloisa to Abelard

The Dunciad

The Rape of the Lock

Featured Collections

Philosophy, Logic, & Ethics

View Collection

Religion & Spirituality

School Book List Titles

Valentine's Day Reads: The Theme of Love

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

That Viral Essay Wasn’t About Age Gaps. It Was About Marrying Rich.

But both tactics are flawed if you want to have any hope of becoming yourself..

Women are wisest, a viral essay in New York magazine’s the Cut argues , to maximize their most valuable cultural assets— youth and beauty—and marry older men when they’re still very young. Doing so, 27-year-old writer Grazie Sophia Christie writes, opens up a life of ease, and gets women off of a male-defined timeline that has our professional and reproductive lives crashing irreconcilably into each other. Sure, she says, there are concessions, like one’s freedom and entire independent identity. But those are small gives in comparison to a life in which a person has no adult responsibilities, including the responsibility to become oneself.

This is all framed as rational, perhaps even feminist advice, a way for women to quit playing by men’s rules and to reject exploitative capitalist demands—a choice the writer argues is the most obviously intelligent one. That other Harvard undergraduates did not busy themselves trying to attract wealthy or soon-to-be-wealthy men seems to flummox her (taking her “high breasts, most of my eggs, plausible deniability when it came to purity, a flush ponytail, a pep in my step that had yet to run out” to the Harvard Business School library, “I could not understand why my female classmates did not join me, given their intelligence”). But it’s nothing more than a recycling of some of the oldest advice around: For women to mold themselves around more-powerful men, to never grow into independent adults, and to find happiness in a state of perpetual pre-adolescence, submission, and dependence. These are odd choices for an aspiring writer (one wonders what, exactly, a girl who never wants to grow up and has no idea who she is beyond what a man has made her into could possibly have to write about). And it’s bad advice for most human beings, at least if what most human beings seek are meaningful and happy lives.

But this is not an essay about the benefits of younger women marrying older men. It is an essay about the benefits of younger women marrying rich men. Most of the purported upsides—a paid-for apartment, paid-for vacations, lives split between Miami and London—are less about her husband’s age than his wealth. Every 20-year-old in the country could decide to marry a thirtysomething and she wouldn’t suddenly be gifted an eternal vacation.

Which is part of what makes the framing of this as an age-gap essay both strange and revealing. The benefits the writer derives from her relationship come from her partner’s money. But the things she gives up are the result of both their profound financial inequality and her relative youth. Compared to her and her peers, she writes, her husband “struck me instead as so finished, formed.” By contrast, “At 20, I had felt daunted by the project of becoming my ideal self.” The idea of having to take responsibility for her own life was profoundly unappealing, as “adulthood seemed a series of exhausting obligations.” Tying herself to an older man gave her an out, a way to skip the work of becoming an adult by allowing a father-husband to mold her to his desires. “My husband isn’t my partner,” she writes. “He’s my mentor, my lover, and, only in certain contexts, my friend. I’ll never forget it, how he showed me around our first place like he was introducing me to myself: This is the wine you’ll drink, where you’ll keep your clothes, we vacation here, this is the other language we’ll speak, you’ll learn it, and I did.”

These, by the way, are the things she says are benefits of marrying older.

The downsides are many, including a basic inability to express a full range of human emotion (“I live in an apartment whose rent he pays and that constrains the freedom with which I can ever be angry with him”) and an understanding that she owes back, in some other form, what he materially provides (the most revealing line in the essay may be when she claims that “when someone says they feel unappreciated, what they really mean is you’re in debt to them”). It is clear that part of what she has paid in exchange for a paid-for life is a total lack of any sense of self, and a tacit agreement not to pursue one. “If he ever betrayed me and I had to move on, I would survive,” she writes, “but would find in my humor, preferences, the way I make coffee or the bed nothing that he did not teach, change, mold, recompose, stamp with his initials.”

Reading Christie’s essay, I thought of another one: Joan Didion’s on self-respect , in which Didion argues that “character—the willingness to accept responsibility for one’s own life—is the source from which self-respect springs.” If we lack self-respect, “we are peculiarly in thrall to everyone we see, curiously determined to live out—since our self-image is untenable—their false notions of us.” Self-respect may not make life effortless and easy. But it means that whenever “we eventually lie down alone in that notoriously un- comfortable bed, the one we make ourselves,” at least we can fall asleep.

It can feel catty to publicly criticize another woman’s romantic choices, and doing so inevitably opens one up to accusations of jealousy or pettiness. But the stories we tell about marriage, love, partnership, and gender matter, especially when they’re told in major culture-shaping magazines. And it’s equally as condescending to say that women’s choices are off-limits for critique, especially when those choices are shared as universal advice, and especially when they neatly dovetail with resurgent conservative efforts to make women’s lives smaller and less independent. “Marry rich” is, as labor economist Kathryn Anne Edwards put it in Bloomberg, essentially the Republican plan for mothers. The model of marriage as a hierarchy with a breadwinning man on top and a younger, dependent, submissive woman meeting his needs and those of their children is not exactly a fresh or groundbreaking ideal. It’s a model that kept women trapped and miserable for centuries.

It’s also one that profoundly stunted women’s intellectual and personal growth. In her essay for the Cut, Christie seems to believe that a life of ease will abet a life freed up for creative endeavors, and happiness. But there’s little evidence that having material abundance and little adversity actually makes people happy, let alone more creatively generativ e . Having one’s basic material needs met does seem to be a prerequisite for happiness. But a meaningful life requires some sense of self, an ability to look outward rather than inward, and the intellectual and experiential layers that come with facing hardship and surmounting it.

A good and happy life is not a life in which all is easy. A good and happy life (and here I am borrowing from centuries of philosophers and scholars) is one characterized by the pursuit of meaning and knowledge, by deep connections with and service to other people (and not just to your husband and children), and by the kind of rich self-knowledge and satisfaction that comes from owning one’s choices, taking responsibility for one’s life, and doing the difficult and endless work of growing into a fully-formed person—and then evolving again. Handing everything about one’s life over to an authority figure, from the big decisions to the minute details, may seem like a path to ease for those who cannot stomach the obligations and opportunities of their own freedom. It’s really an intellectual and emotional dead end.

And what kind of man seeks out a marriage like this, in which his only job is to provide, but very much is owed? What kind of man desires, as the writer cast herself, a raw lump of clay to be molded to simply fill in whatever cracks in his life needed filling? And if the transaction is money and guidance in exchange for youth, beauty, and pliability, what happens when the young, beautiful, and pliable party inevitably ages and perhaps feels her backbone begin to harden? What happens if she has children?

The thing about using youth and beauty as a currency is that those assets depreciate pretty rapidly. There is a nearly endless supply of young and beautiful women, with more added each year. There are smaller numbers of wealthy older men, and the pool winnows down even further if one presumes, as Christie does, that many of these men want to date and marry compliant twentysomethings. If youth and beauty are what you’re exchanging for a man’s resources, you’d better make sure there’s something else there—like the basic ability to provide for yourself, or at the very least a sense of self—to back that exchange up.

It is hard to be an adult woman; it’s hard to be an adult, period. And many women in our era of unfinished feminism no doubt find plenty to envy about a life in which they don’t have to work tirelessly to barely make ends meet, don’t have to manage the needs of both children and man-children, could simply be taken care of for once. This may also explain some of the social media fascination with Trad Wives and stay-at-home girlfriends (some of that fascination is also, I suspect, simply a sexual submission fetish , but that’s another column). Fantasies of leisure reflect a real need for it, and American women would be far better off—happier, freer—if time and resources were not so often so constrained, and doled out so inequitably.

But the way out is not actually found in submission, and certainly not in electing to be carried by a man who could choose to drop you at any time. That’s not a life of ease. It’s a life of perpetual insecurity, knowing your spouse believes your value is decreasing by the day while his—an actual dollar figure—rises. A life in which one simply allows another adult to do all the deciding for them is a stunted life, one of profound smallness—even if the vacations are nice.

Things you buy through our links may earn Vox Media a commission

The Case for Marrying an Older Man

A woman’s life is all work and little rest. an age gap relationship can help..

In the summer, in the south of France, my husband and I like to play, rather badly, the lottery. We take long, scorching walks to the village — gratuitous beauty, gratuitous heat — kicking up dust and languid debates over how we’d spend such an influx. I purchase scratch-offs, jackpot tickets, scraping the former with euro coins in restaurants too fine for that. I never cash them in, nor do I check the winning numbers. For I already won something like the lotto, with its gifts and its curses, when he married me.

He is ten years older than I am. I chose him on purpose, not by chance. As far as life decisions go, on balance, I recommend it.

When I was 20 and a junior at Harvard College, a series of great ironies began to mock me. I could study all I wanted, prove myself as exceptional as I liked, and still my fiercest advantage remained so universal it deflated my other plans. My youth. The newness of my face and body. Compellingly effortless; cruelly fleeting. I shared it with the average, idle young woman shrugging down the street. The thought, when it descended on me, jolted my perspective, the way a falling leaf can make you look up: I could diligently craft an ideal existence, over years and years of sleepless nights and industry. Or I could just marry it early.

So naturally I began to lug a heavy suitcase of books each Saturday to the Harvard Business School to work on my Nabokov paper. In one cavernous, well-appointed room sat approximately 50 of the planet’s most suitable bachelors. I had high breasts, most of my eggs, plausible deniability when it came to purity, a flush ponytail, a pep in my step that had yet to run out. Apologies to Progress, but older men still desired those things.

I could not understand why my female classmates did not join me, given their intelligence. Each time I reconsidered the project, it struck me as more reasonable. Why ignore our youth when it amounted to a superpower? Why assume the burdens of womanhood, its too-quick-to-vanish upper hand, but not its brief benefits at least? Perhaps it came easier to avoid the topic wholesale than to accept that women really do have a tragically short window of power, and reason enough to take advantage of that fact while they can. As for me, I liked history, Victorian novels, knew of imminent female pitfalls from all the books I’d read: vampiric boyfriends; labor, at the office and in the hospital, expected simultaneously; a decline in status as we aged, like a looming eclipse. I’d have disliked being called calculating, but I had, like all women, a calculator in my head. I thought it silly to ignore its answers when they pointed to an unfairness for which we really ought to have been preparing.

I was competitive by nature, an English-literature student with all the corresponding major ambitions and minor prospects (Great American novel; email job). A little Bovarist , frantic for new places and ideas; to travel here, to travel there, to be in the room where things happened. I resented the callow boys in my class, who lusted after a particular, socially sanctioned type on campus: thin and sexless, emotionally detached and socially connected, the opposite of me. Restless one Saturday night, I slipped on a red dress and snuck into a graduate-school event, coiling an HDMI cord around my wrist as proof of some technical duty. I danced. I drank for free, until one of the organizers asked me to leave. I called and climbed into an Uber. Then I promptly climbed out of it. For there he was, emerging from the revolving doors. Brown eyes, curved lips, immaculate jacket. I went to him, asked him for a cigarette. A date, days later. A second one, where I discovered he was a person, potentially my favorite kind: funny, clear-eyed, brilliant, on intimate terms with the universe.

I used to love men like men love women — that is, not very well, and with a hunger driven only by my own inadequacies. Not him. In those early days, I spoke fondly of my family, stocked the fridge with his favorite pasta, folded his clothes more neatly than I ever have since. I wrote his mother a thank-you note for hosting me in his native France, something befitting a daughter-in-law. It worked; I meant it. After graduation and my fellowship at Oxford, I stayed in Europe for his career and married him at 23.

Of course I just fell in love. Romances have a setting; I had only intervened to place myself well. Mainly, I spotted the precise trouble of being a woman ahead of time, tried to surf it instead of letting it drown me on principle. I had grown bored of discussions of fair and unfair, equal or unequal , and preferred instead to consider a thing called ease.

The reception of a particular age-gap relationship depends on its obviousness. The greater and more visible the difference in years and status between a man and a woman, the more it strikes others as transactional. Transactional thinking in relationships is both as American as it gets and the least kosher subject in the American romantic lexicon. When a 50-year-old man and a 25-year-old woman walk down the street, the questions form themselves inside of you; they make you feel cynical and obscene: How good of a deal is that? Which party is getting the better one? Would I take it? He is older. Income rises with age, so we assume he has money, at least relative to her; at minimum, more connections and experience. She has supple skin. Energy. Sex. Maybe she gets a Birkin. Maybe he gets a baby long after his prime. The sight of their entwined hands throws a lucid light on the calculations each of us makes, in love, to varying degrees of denial. You could get married in the most romantic place in the world, like I did, and you would still have to sign a contract.

Twenty and 30 is not like 30 and 40; some freshness to my features back then, some clumsiness in my bearing, warped our decade, in the eyes of others, to an uncrossable gulf. Perhaps this explains the anger we felt directed at us at the start of our relationship. People seemed to take us very, very personally. I recall a hellish car ride with a friend of his who began to castigate me in the backseat, in tones so low that only I could hear him. He told me, You wanted a rich boyfriend. You chased and snuck into parties . He spared me the insult of gold digger, but he drew, with other words, the outline for it. Most offended were the single older women, my husband’s classmates. They discussed me in the bathroom at parties when I was in the stall. What does he see in her? What do they talk about? They were concerned about me. They wielded their concern like a bludgeon. They paraphrased without meaning to my favorite line from Nabokov’s Lolita : “You took advantage of my disadvantage,” suspecting me of some weakness he in turn mined. It did not disturb them, so much, to consider that all relationships were trades. The trouble was the trade I’d made struck them as a bad one.

The truth is you can fall in love with someone for all sorts of reasons, tiny transactions, pluses and minuses, whose sum is your affection for each other, your loyalty, your commitment. The way someone picks up your favorite croissant. Their habit of listening hard. What they do for you on your anniversary and your reciprocal gesture, wrapped thoughtfully. The serenity they inspire; your happiness, enlivening it. When someone says they feel unappreciated, what they really mean is you’re in debt to them.

When I think of same-age, same-stage relationships, what I tend to picture is a woman who is doing too much for too little.

I’m 27 now, and most women my age have “partners.” These days, girls become partners quite young. A partner is supposed to be a modern answer to the oppression of marriage, the terrible feeling of someone looming over you, head of a household to which you can only ever be the neck. Necks are vulnerable. The problem with a partner, however, is if you’re equal in all things, you compromise in all things. And men are too skilled at taking .