Looking to publish? Meet your dream editor, designer and marketer on Reedsy.

Find the perfect editor for your next book

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Jul 24, 2023

15 Examples of Great Dialogue (And Why They Work So Well)

Great dialogue is hard to pin down, but you know it when you hear or see it. In the earlier parts of this guide, we showed you some well-known tips and rules for writing dialogue. In this section, we'll show you those rules in action with 15 examples of great dialogue, breaking down exactly why they work so well.

1. Barbara Kingsolver, Unsheltered

In the opening of Barbara Kingsolver’s Unsheltered, we meet Willa Knox, a middle-aged and newly unemployed writer who has just inherited a ramshackle house.

“The simplest thing would be to tear it down,” the man said. “The house is a shambles.” She took this news as a blood-rush to the ears: a roar of peasant ancestors with rocks in their fists, facing the evictor. But this man was a contractor. Willa had called him here and she could send him away. She waited out her panic while he stood looking at her shambles, appearing to nurse some satisfaction from his diagnosis. She picked out words. “It’s not a living thing. You can’t just pronounce it dead. Anything that goes wrong with a structure can be replaced with another structure. Am I right?” “Correct. What I am saying is that the structure needing to be replaced is all of it. I’m sorry. Your foundation is nonexistent.”

Alfred Hitchcock once described drama as "life with the boring bits cut out." In this passage, Kingsolver cuts out the boring parts of Willa's conversation with her contractor and brings us right to the tensest, most interesting part of the conversation.

By entering their conversation late , the reader is spared every tedious detail of their interaction.

Instead of a blow-by-blow account of their negotiations (what she needs done, when he’s free, how she’ll be paying), we’re dropped right into the emotional heart of the discussion. The novel opens with the narrator learning that the home she cherishes can’t be salvaged.

By starting off in the middle of (relatively obscure) dialogue, it takes a moment for the reader to orient themselves in the story and figure out who is speaking, and what they’re speaking about. This disorientation almost mirrors Willa’s own reaction to the bad news, as her expectations for a new life in her new home are swiftly undermined.

FREE COURSE

How to Write Believable Dialogue

Master the art of dialogue in 10 five-minute lessons.

2. Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

In the first piece of dialogue in Pride and Prejudice , we meet Mr and Mrs Bennet, as Mrs Bennet attempts to draw her husband into a conversation about neighborhood gossip.

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?” Mr. Bennet replied that he had not. “But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.” Mr. Bennet made no answer. “Do you not want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently. “You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.” This was invitation enough. “Why, my dear, you must know, Mrs. Long says that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England; that he came down on Monday in a chaise and four to see the place, and was so much delighted with it, that he agreed with Mr. Morris immediately; that he is to take possession before Michaelmas, and some of his servants are to be in the house by the end of next week.”

Austen’s dialogue is always witty, subtle, and packed with character. This extract from Pride and Prejudice is a great example of dialogue being used to develop character relationships .

We instantly learn everything we need to know about the dynamic between Mr and Mrs Bennet’s from their first interaction: she’s chatty, and he’s the beleaguered listener who has learned to entertain her idle gossip, if only for his own sake (hence “you want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it”).

There is even a clear difference between the two characters visually on the page: Mr Bennet responds in short sentences, in simple indirect speech, or not at all, but this is “invitation enough” for Mrs Bennet to launch into a rambling and extended response, dominating the conversation in text just as she does audibly.

The fact that Austen manages to imbue her dialogue with so much character-building realism means we hardly notice the amount of crucial plot exposition she has packed in here. This heavily expository dialogue could be a drag to get through, but Austen’s colorful characterization means she slips it under the radar with ease, forwarding both our understanding of these people and the world they live in simultaneously.

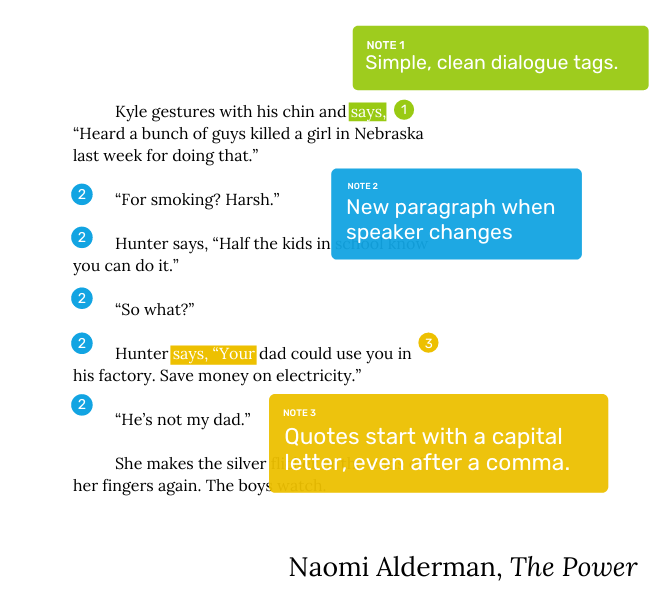

3. Naomi Alderman, The Power

In The Power , young women around the world suddenly find themselves capable of generating and controlling electricity. In this passage, between two boys and a girl who just used those powers to light her cigarette.

Kyle gestures with his chin and says, “Heard a bunch of guys killed a girl in Nebraska last week for doing that.” “For smoking? Harsh.” Hunter says, “Half the kids in school know you can do it.” “So what?” Hunter says, “Your dad could use you in his factory. Save money on electricity.” “He’s not my dad.” She makes the silver flicker at the ends of her fingers again. The boys watch.

Alderman here uses a show, don’t tell approach to expositional dialogue. Within this short exchange, we discover a lot about Allie, her personal circumstances, and the developing situation elsewhere. We learn that women are being punished harshly for their powers; that Allie is expected to be ashamed of those powers and keep them a secret, but doesn’t seem to care to do so; that her father is successful in industry; and that she has a difficult relationship with him. Using dialogue in this way prevents info-dumping backstory all at once, and instead helps us learn about the novel’s world in a natural way.

Show, Don't Tell

Master the golden rule of writing in 10 five-minute lessons.

4. Kazuo Ishiguro, Never Let Me Go

Here, friends Tommy and Kathy have a conversation after Tommy has had a meltdown. After being bullied by a group of boys, he has been stomping around in the mud, the precise reaction they were hoping to evoke from him.

“Tommy,” I said, quite sternly. “There’s mud all over your shirt.” “So what?” he mumbled. But even as he said this, he looked down and noticed the brown specks, and only just stopped himself crying out in alarm. Then I saw the surprise register on his face that I should know about his feelings for the polo shirt. “It’s nothing to worry about.” I said, before the silence got humiliating for him. “It’ll come off. If you can’t get it off yourself, just take it to Miss Jody.” He went on examining his shirt, then said grumpily, “It’s nothing to do with you anyway.”

This episode from Never Let Me Go highlights the power of interspersing action beats within dialogue. These action beats work in several ways to add depth to what would otherwise be a very simple and fairly nondescript exchange. Firstly, they draw attention to the polo shirt, and highlight its potential significance in the plot. Secondly, they help to further define Kathy’s relationship with Tommy.

We learn through Tommy’s surprised reaction that he didn’t think Kathy knew how much he loved his seemingly generic polo shirt. This moment of recognition allows us to see that she cares for him and understands him more deeply than even he realized. Kathy breaking the silence before it can “humiliate” Tommy further emphasizes her consideration for him. While the dialogue alone might make us think Kathy is downplaying his concerns with pragmatic advice, it is the action beats that tell the true story here.

5. J R R Tolkien, The Hobbit

The eponymous hobbit Bilbo is engaged in a game of riddles with the strange creature Gollum.

"What have I got in my pocket?" he said aloud. He was talking to himself, but Gollum thought it was a riddle, and he was frightfully upset. "Not fair! not fair!" he hissed. "It isn't fair, my precious, is it, to ask us what it's got in its nassty little pocketses?" Bilbo seeing what had happened and having nothing better to ask stuck to his question. "What have I got in my pocket?" he said louder. "S-s-s-s-s," hissed Gollum. "It must give us three guesseses, my precious, three guesseses." "Very well! Guess away!" said Bilbo. "Handses!" said Gollum. "Wrong," said Bilbo, who had luckily just taken his hand out again. "Guess again!" "S-s-s-s-s," said Gollum, more upset than ever.

Tolkein’s dialogue for Gollum is a masterclass in creating distinct character voices . By using a repeated catchphrase (“my precious”) and unconventional spelling and grammar to reflect his unusual speech pattern, Tolkien creates an idiosyncratic, unique (and iconic) speech for Gollum. This vivid approach to formatting dialogue, which is almost a transliteration of Gollum's sounds, allows readers to imagine his speech pattern and practically hear it aloud.

We wouldn’t recommend using this extreme level of idiosyncrasy too often in your writing — it can get wearing for readers after a while, and Tolkien deploys it sparingly, as Gollum’s appearances are limited to a handful of scenes. However, you can use Tolkien’s approach as inspiration to create (slightly more subtle) quirks of speech for your own characters.

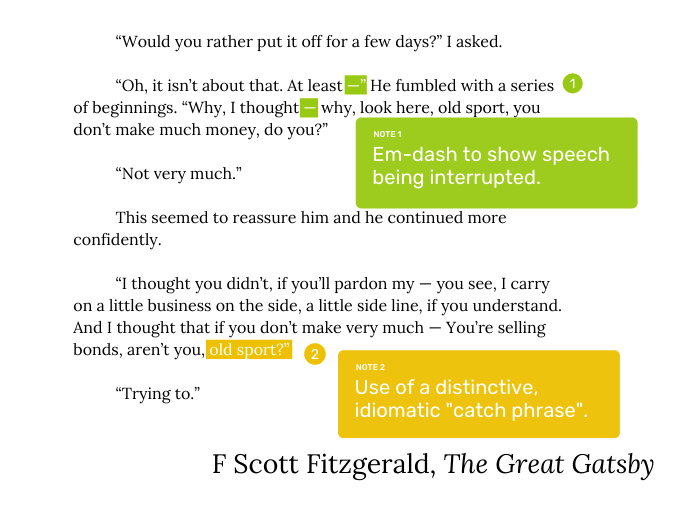

6. F Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

The narrator, Nick has just done his new neighbour Gatsby a favor by inviting his beloved Daisy over to tea. Perhaps in return, Gatsby then attempts to make a shady business proposition.

“There’s another little thing,” he said uncertainly, and hesitated. “Would you rather put it off for a few days?” I asked. “Oh, it isn’t about that. At least —” He fumbled with a series of beginnings. “Why, I thought — why, look here, old sport, you don’t make much money, do you?” “Not very much.” This seemed to reassure him and he continued more confidently. “I thought you didn’t, if you’ll pardon my — you see, I carry on a little business on the side, a little side line, if you understand. And I thought that if you don’t make very much — You’re selling bonds, aren’t you, old sport?” “Trying to.”

This dialogue from The Great Gatsby is a great example of how to make dialogue sound natural. Gatsby tripping over his own words (even interrupting himself , as marked by the em-dashes) not only makes his nerves and awkwardness palpable but also mimics real speech. Just as real people often falter and make false starts when they’re speaking off the cuff, Gatsby too flounders, giving us insight into his self-doubt; his speech isn’t polished and perfect, and neither is he despite all his efforts to appear so.

Fitzgerald also creates a distinctive voice for Gatsby by littering his speech with the character's signature term of endearment, “old sport”. We don’t even really need dialogue markers to know who’s speaking here — a sign of very strong characterization through dialogue.

7. Arthur Conan Doyle, A Study in Scarlet

In this first meeting between the two heroes of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, Sherlock Holmes and John Watson, John is introduced to Sherlock while the latter is hard at work in the lab.

“How are you?” he said cordially, gripping my hand with a strength for which I should hardly have given him credit. “You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.” “How on earth did you know that?” I asked in astonishment. “Never mind,” said he, chuckling to himself. “The question now is about hemoglobin. No doubt you see the significance of this discovery of mine?” “It is interesting, chemically, no doubt,” I answered, “but practically— ” “Why, man, it is the most practical medico-legal discovery for years. Don’t you see that it gives us an infallible test for blood stains. Come over here now!” He seized me by the coat-sleeve in his eagerness, and drew me over to the table at which he had been working. “Let us have some fresh blood,” he said, digging a long bodkin into his finger, and drawing off the resulting drop of blood in a chemical pipette. “Now, I add this small quantity of blood to a litre of water. You perceive that the resulting mixture has the appearance of pure water. The proportion of blood cannot be more than one in a million. I have no doubt, however, that we shall be able to obtain the characteristic reaction.” As he spoke, he threw into the vessel a few white crystals, and then added some drops of a transparent fluid. In an instant the contents assumed a dull mahogany colour, and a brownish dust was precipitated to the bottom of the glass jar. “Ha! ha!” he cried, clapping his hands, and looking as delighted as a child with a new toy. “What do you think of that?”

This passage uses a number of the key techniques for writing naturalistic and exciting dialogue, including characters speaking over one another and the interspersal of action beats.

Sherlock cutting off Watson to launch into a monologue about his blood experiment shows immediately where Sherlock’s interest lies — not in small talk, or the person he is speaking to, but in his own pursuits, just like earlier in the conversation when he refuses to explain anything to John and is instead self-absorbedly “chuckling to himself”. This helps establish their initial rapport (or lack thereof) very quickly.

Breaking up that monologue with snippets of him undertaking the forensic tests allows us to experience the full force of his enthusiasm over it without having to read an uninterrupted speech about the ins and outs of a science experiment.

Starting to think you might like to read some Sherlock? Check out our guide to the Sherlock Holmes canon !

8. Brandon Taylor, Real Life

Here, our protagonist Wallace is questioned by Ramon, a friend-of-a-friend, over the fact that he is considering leaving his PhD program.

Wallace hums. “I mean, I wouldn’t say that I want to leave, but I’ve thought about it, sure.” “Why would you do that? I mean, the prospects for… black people, you know?” “What are the prospects for black people?” Wallace asks, though he knows he will be considered the aggressor for this question.

Brandon Taylor’s Real Life is drawn from the author’s own experiences as a queer Black man, attempting to navigate the unwelcoming world of academia, navigating the world of academia, and so it’s no surprise that his dialogue rings so true to life — it’s one of the reasons the novel is one of our picks for must-read books by Black authors .

This episode is part of a pattern where Wallace is casually cornered and questioned by people who never question for a moment whether they have the right to ambush him or criticize his choices. The use of indirect dialogue at the end shows us this is a well-trodden path for Wallace: he has had this same conversation several times, and can pre-empt the exact outcome.

This scene is also a great example of the dramatic significance of people choosing not to speak. The exchange happens in front of a big group, but — despite their apparent discomfort — nobody speaks up to defend Wallace, or to criticize Ramon’s patronizing microaggressions. Their silence is deafening, and we get a glimpse of Ramon’s isolation due to the complacency of others, all due to what is not said in this dialogue example.

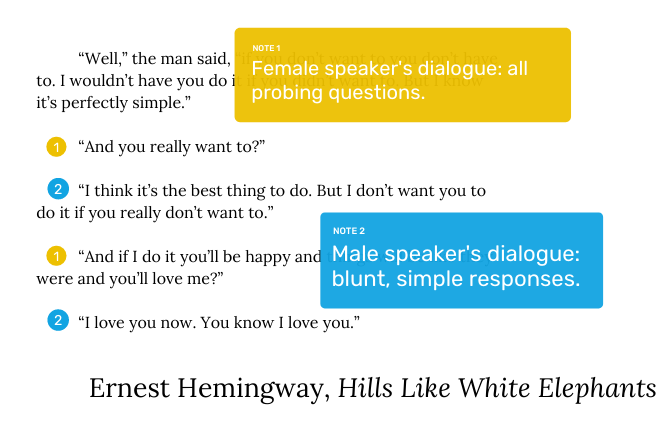

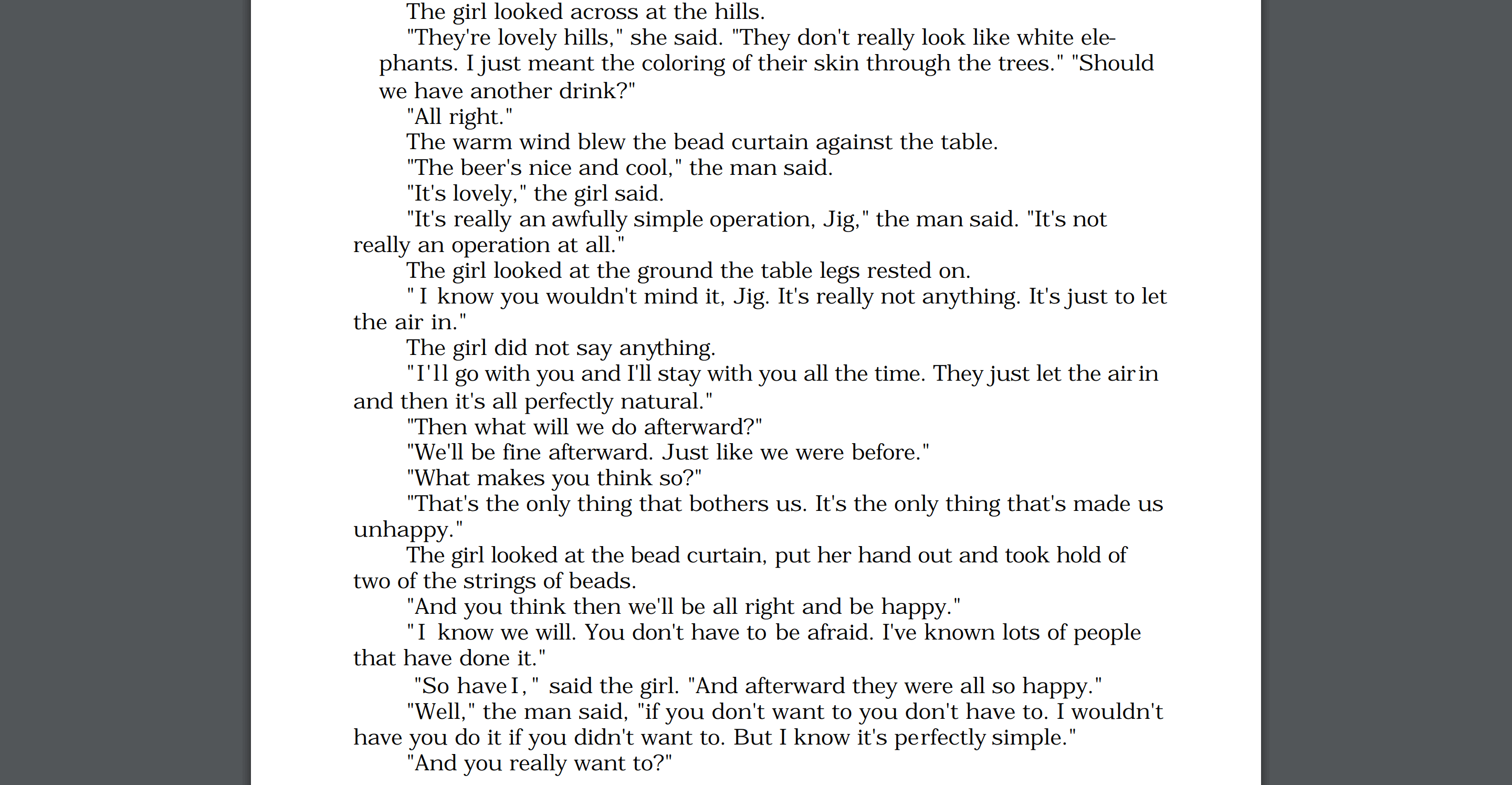

9. Ernest Hemingway, Hills Like White Elephants

In this short story, an unnamed man and a young woman discuss whether or not they should terminate a pregnancy while sitting on a train platform.

“Well,” the man said, “if you don’t want to you don’t have to. I wouldn’t have you do it if you didn’t want to. But I know it’s perfectly simple.” “And you really want to?” “I think it’s the best thing to do. But I don’t want you to do it if you really don’t want to.” “And if I do it you’ll be happy and things will be like they were and you’ll love me?” “I love you now. You know I love you.” “I know. But if I do it, then it will be nice again if I say things are like white elephants, and you’ll like it?” “I’ll love it. I love it now but I just can’t think about it. You know how I get when I worry.” “If I do it you won’t ever worry?” “I won’t worry about that because it’s perfectly simple.”

This example of dialogue from Hemingway’s short story Hills Like White Elephants moves at quite a clip. The conversation quickly bounces back and forth between the speakers, and the call-and-response format of the woman asking and the man answering is effective because it establishes a clear dynamic between the two speakers: the woman is the one seeking reassurance and trying to understand the man’s feelings, while he is the one who is ultimately in control of the situation.

Note the sparing use of dialogue markers: this minimalist approach keeps the dialogue brisk, and we can still easily understand who is who due to the use of a new paragraph when the speaker changes .

Like this classic author’s style? Head over to our selection of the 11 best Ernest Hemingway books .

10. Madeline Miller, Circe

In Madeline Miller’s retelling of Greek myth, we witness a conversation between the mythical enchantress Circe and Telemachus (son of Odysseus).

“You do not grieve for your father?” “I do. I grieve that I never met the father everyone told me I had.” I narrowed my eyes. “Explain.” “I am no storyteller.” “I am not asking for a story. You have come to my island. You owe me truth.” A moment passed, and then he nodded. “You will have it.”

This short and punchy exchange hits on a lot of the stylistic points we’ve covered so far. The conversation is a taut tennis match between the two speakers as they volley back and forth with short but impactful sentences, and unnecessary dialogue tags have been shaved off . It also highlights Circe’s imperious attitude, a result of her divine status. Her use of short, snappy declaratives and imperatives demonstrates that she’s used to getting her own way and feels no need to mince her words.

11. Andre Aciman, Call Me By Your Name

This is an early conversation between seventeen-year-old Elio and his family’s handsome new student lodger, Oliver.

What did one do around here? Nothing. Wait for summer to end. What did one do in the winter, then? I smiled at the answer I was about to give. He got the gist and said, “Don’t tell me: wait for summer to come, right?” I liked having my mind read. He’d pick up on dinner drudgery sooner than those before him. “Actually, in the winter the place gets very gray and dark. We come for Christmas. Otherwise it’s a ghost town.” “And what else do you do here at Christmas besides roast chestnuts and drink eggnog?” He was teasing. I offered the same smile as before. He understood, said nothing, we laughed. He asked what I did. I played tennis. Swam. Went out at night. Jogged. Transcribed music. Read. He said he jogged too. Early in the morning. Where did one jog around here? Along the promenade, mostly. I could show him if he wanted. It hit me in the face just when I was starting to like him again: “Later, maybe.”

Dialogue is one of the most crucial aspects of writing romance — what’s a literary relationship without some flirty lines? Here, however, Aciman gives us a great example of efficient dialogue. By removing unnecessary dialogue and instead summarizing with narration, he’s able to confer the gist of the conversation without slowing down the pace unnecessarily. Instead, the emphasis is left on what’s unsaid, the developing romantic subtext.

Furthermore, the fact that we receive this scene in half-reported snippets rather than as an uninterrupted transcript emphasizes the fact that this is Elio’s own recollection of the story, as the manipulation of the dialogue in this way serves to mimic the nostalgic haziness of memory.

Understanding Point of View

Learn to master different POVs and choose the best for your story.

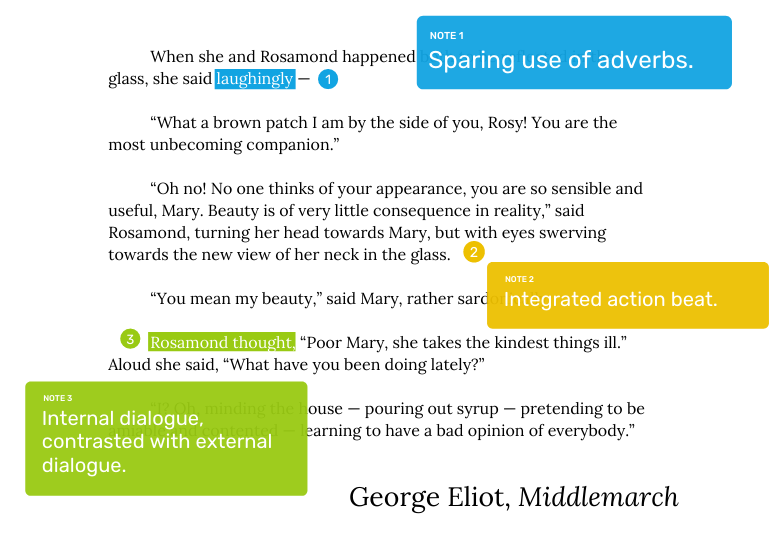

12. George Eliot, Middlemarch

Two of Eliot’s characters, Mary and Rosamond, are out shopping,

When she and Rosamond happened both to be reflected in the glass, she said laughingly — “What a brown patch I am by the side of you, Rosy! You are the most unbecoming companion.” “Oh no! No one thinks of your appearance, you are so sensible and useful, Mary. Beauty is of very little consequence in reality,” said Rosamond, turning her head towards Mary, but with eyes swerving towards the new view of her neck in the glass. “You mean my beauty,” said Mary, rather sardonically. Rosamond thought, “Poor Mary, she takes the kindest things ill.” Aloud she said, “What have you been doing lately?” “I? Oh, minding the house — pouring out syrup — pretending to be amiable and contented — learning to have a bad opinion of everybody.”

This excerpt, a conversation between the level-headed Mary and vain Rosamond, is an example of dialogue that develops character relationships naturally. Action descriptors allow us to understand what is really happening in the conversation.

Whilst the speech alone might lead us to believe Rosamond is honestly (if clumsily) engaging with her friend, the description of her simultaneously gazing at herself in a mirror gives us insight not only into her vanity, but also into the fact that she is not really engaged in her conversation with Mary at all.

The use of internal dialogue cut into the conversation (here formatted with quotation marks rather than the usual italics ) lets us know what Rosamond is actually thinking, and the contrast between this and what she says aloud is telling. The fact that we know she privately realizes she has offended Mary, but quickly continues the conversation rather than apologizing, is emphatic of her character. We get to know Rosamond very well within this short passage, which is a hallmark of effective character-driven dialogue.

13. John Steinbeck, The Winter of our Discontent

Here, Mary (speaking first) reacts to her husband Ethan’s attempts to discuss his previous experiences as a disciplined soldier, his struggles in subsequent life, and his feeling of impending change.

“You’re trying to tell me something.” “Sadly enough, I am. And it sounds in my ears like an apology. I hope it is not.” “I’m going to set out lunch.”

Steinbeck’s Winter of our Discontent is an acute study of alienation and miscommunication, and this exchange exemplifies the ways in which characters can fail to communicate, even when they’re speaking. The pair speaking here are trapped in a dysfunctional marriage which leaves Ethan feeling isolated, and part of his loneliness comes from the accumulation of exchanges such as this one. Whenever he tries to communicate meaningfully with his wife, she shuts the conversation down with a complete non sequitur.

We expect Mary’s “you’re trying to tell me something” to be followed by a revelation, but Ethan is not forthcoming in his response, and Mary then exits the conversation entirely. Nothing is communicated, and the jarring and frustrating effect of having our expectations subverted goes a long way in mirroring Ethan’s own frustration.

Just like Ethan and Mary, we receive no emotional pay-off, and this passage of characters talking past one another doesn’t further the plot as we hope it might, but instead gives us insight into the extent of these characters’ estrangement.

14. Bret Easton Ellis , Less Than Zero

The disillusioned main character of Bret Easton Ellis’ debut novel, Clay, here catches up with a college friend, Daniel, whom he hasn’t seen in a while.

He keeps rubbing his mouth and when I realize that he’s not going to answer me, I ask him what he’s been doing. “Been doing?” “Yeah.” “Hanging out.” “Hanging out where?” “Where? Around.”

Less Than Zero is an elegy to conversation, and this dialogue is an example of the many vacuous exchanges the protagonist engages in, seemingly just to fill time. The whole book is deliberately unpoetic and flat, and depicts the lives of disaffected youths in 1980s LA. Their misguided attempts to fill the emptiness within them with drink and drugs are ultimately fruitless, and it shows in their conversations: in truth, they have nothing to say to one another at all.

This utterly meaningless exchange would elsewhere be considered dead weight to a story. Here, rather than being fat in need of trimming, the empty conversation is instead thematically resonant.

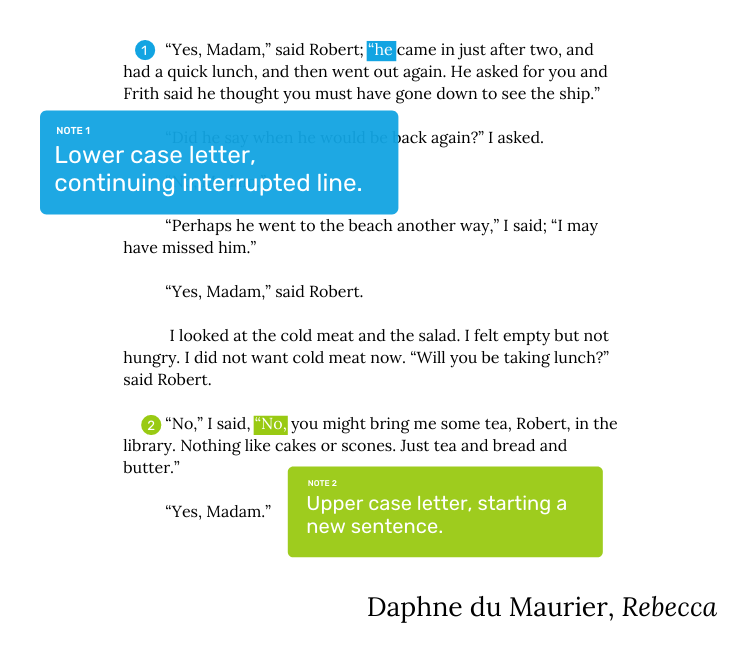

15. Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca

The young narrator of du Maurier’s classic gothic novel here has a strained conversation with Robert, one of the young staff members at her new husband’s home, the unwelcoming Manderley.

“Has Mr. de Winter been in?” I said. “Yes, Madam,” said Robert; “he came in just after two, and had a quick lunch, and then went out again. He asked for you and Frith said he thought you must have gone down to see the ship.” “Did he say when he would be back again?” I asked. “No, Madam.” “Perhaps he went to the beach another way,” I said; “I may have missed him.” “Yes, Madam,” said Robert. I looked at the cold meat and the salad. I felt empty but not hungry. I did not want cold meat now. “Will you be taking lunch?” said Robert. “No,” I said, “No, you might bring me some tea, Robert, in the library. Nothing like cakes or scones. Just tea and bread and butter.” “Yes, Madam.”

We’re including this one in our dialogue examples list to show you the power of everything Du Maurier doesn’t do: rather than cycling through a ton of fancy synonyms for “said”, she opts for spare dialogue and tags.

This interaction's cold, sparse tone complements the lack of warmth the protagonist feels in the moment depicted here. By keeping the dialogue tags simple , the author ratchets up the tension — without any distracting flourishes taking the reader out of the scene. The subtext of the conversation is able to simmer under the surface, and we aren’t beaten over the head with any stage direction extras.

The inclusion of three sentences of internal dialogue in the middle of the dialogue (“I looked at the cold meat and the salad. I felt empty but not hungry. I did not want cold meat now.”) is also a masterful touch. What could have been a single sentence is stretched into three, creating a massive pregnant pause before Robert continues speaking, without having to explicitly signpost one. Manipulating the pace of dialogue in this way and manufacturing meaningful silence is a great way of adding depth to a scene.

Phew! We've been through a lot of dialogue, from first meetings to idle chit-chat to confrontations, and we hope these dialogue examples have been helpful in illustrating some of the most common techniques.

If you’re looking for more pointers on creating believable and effective dialogue, be sure to check out our course on writing dialogue. Or, if you find you learn better through examples, you can look at our list of 100 books to read before you die — it’s packed full of expert storytellers who’ve honed the art of dialogue.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Bring your stories to life

Our free writing app lets you set writing goals and track your progress, so you can finally write that book!

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Write Dialogue: 7 Great Tips for Writers (With Examples)

Hannah Yang

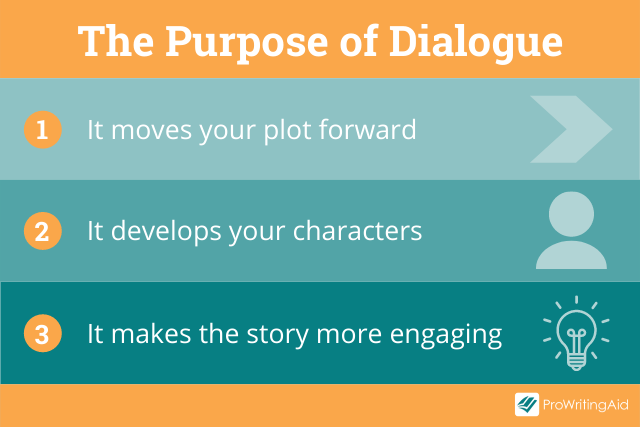

Great dialogue serves multiple purposes. It moves your plot forward. It develops your characters and it makes the story more engaging.

It’s not easy to do all these things at once, but when you master the art of writing dialogue, readers won’t be able to put your book down.

In this article, we will teach you the rules for writing dialogue and share our top dialogue tips that will make your story sing.

Dialogue Rules

How to format dialogue, 7 tips for writing dialogue in a story or book, dialogue examples.

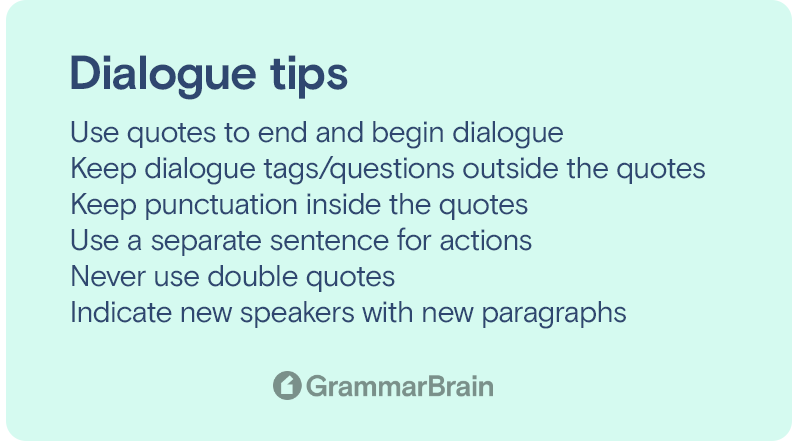

Before we look at tips for writing powerful dialogue, let’s start with an overview of basic dialogue rules.

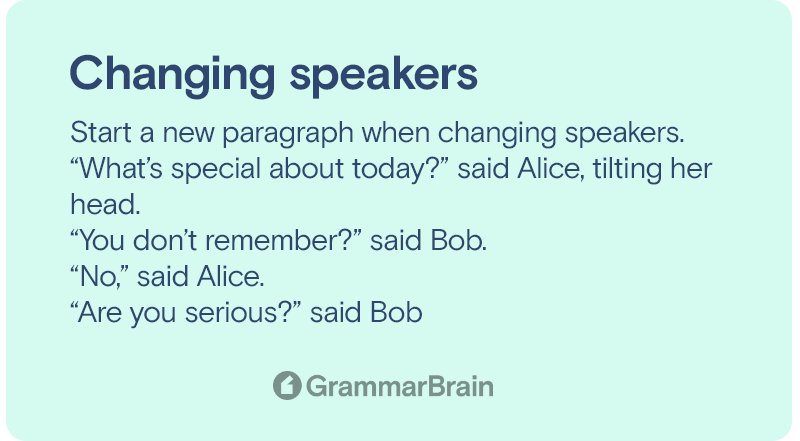

- Start a new paragraph each time there’s a new speaker. Whenever a new character begins to speak, you should give them their own paragraph. This rule makes it easier for the reader to follow the conversation.

- Keep all speech between quotation marks . Everything that a character says should go between quotation marks, including the final punctuation marks. For example, periods and commas should always come before the final quotation mark, not after.

- Don’t use end quotations for paragraphs within long speeches. If a single character speaks for such a long time that you break their speech up into multiple paragraphs, you should omit the quotation marks at the end of each paragraph until they stop talking. The final quotation mark indicates that their speech is over.

- Use single quotes when a character quotes someone else. Whenever you have a quote within a quote, you should use single quotation marks (e.g. She said, “He had me at ‘hello.’”)

- Dialogue tags are optional. A dialogue tag is anything that indicates which character is speaking and how, such as “she said,” “he whispered,” or “I shouted.” You can use dialogue tags if you want to give the reader more information about who’s speaking, but you can also choose to omit them if you want the dialogue to flow more naturally. We’ll be discussing more about this rule in our tips below.

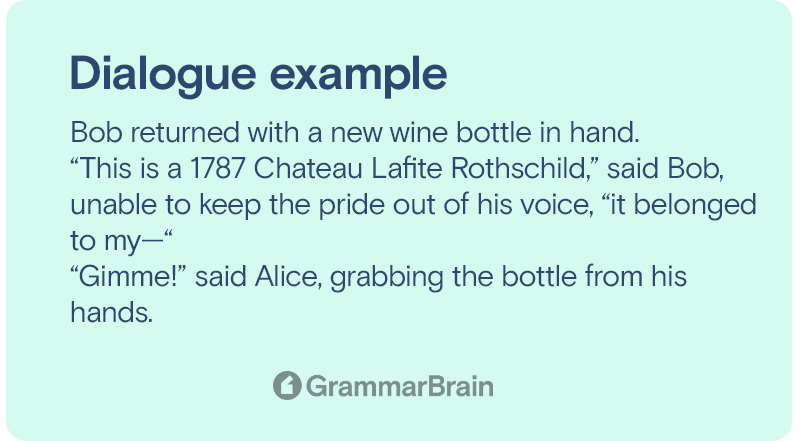

Let’s walk through some examples of how to format dialogue .

The simplest formatting option is to write a line of speech without a dialogue tag. In this case, the entire line of speech goes within the quotation marks, including the period at the end.

- Example: “I think I need a nap.”

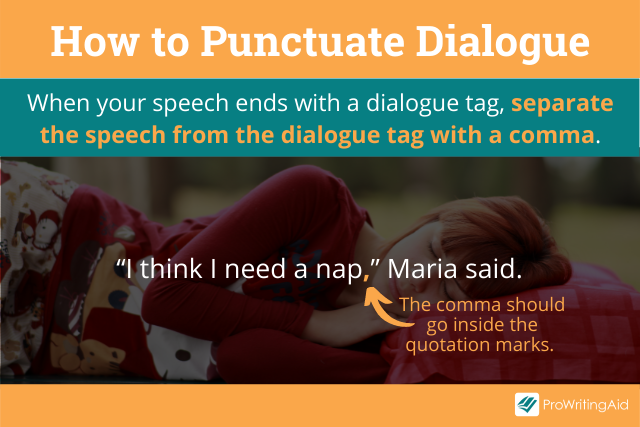

Another common formatting option is to write a single line of speech that ends with a dialogue tag.

Here, you should separate the speech from the dialogue tag with a comma, which should go inside the quotation marks.

- Example: “I think I need a nap,” Maria said.

You can also write a line of speech that starts with a dialogue tag. Again, you separate the dialogue tag with a comma, but this time, the comma goes outside the quotation marks.

- Example: Maria said, “I think I need a nap.”

As an alternative to a simple dialogue tag, you can write a line of speech accompanied by an action beat. In this case, you should use a period rather than a comma, because the action beat is a full sentence.

- Example: Maria sat down on the bed. “I think I need a nap.”

Finally, you can choose to include an action beat while the character is talking.

In this case, you would use em-dashes to separate the action from the dialogue, to indicate that the action happens without a pause in the speech.

- Example: “I think I need”—Maria sat down on the bed—“a nap.”

Now that we’ve covered the basics, we can move on to the more nuanced aspects of writing dialogue.

Here are our seven favorite tips for writing strong, powerful dialogue that will keep your readers engaged.

Tip #1: Create Character Voices

Dialogue is a great way to reveal your characters. What your characters say, and how they say it, can tell us so much about what kind of people they are.

Some characters are witty and gregarious. Others are timid and unobtrusive.

Speech patterns vary drastically from person to person.

To make someone stop talking to them, one character might say “I would rather not talk about this right now,” while another might say, “Shut your mouth before I shut it for you.”

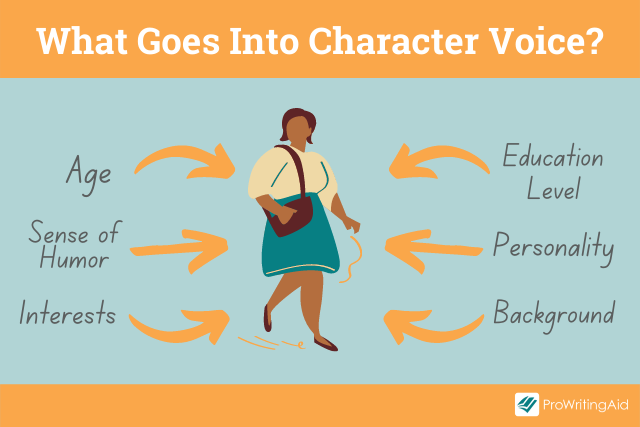

When you’re writing dialogue, think about your character’s education level, personality, and interests.

- What kind of slang do they use?

- Do they prefer long or short sentences?

- Do they ask questions or make assertions?

Each character should have their own voice.

Ideally, you want to write dialogue that lets your reader identify the person speaking at any point in your story just by looking at what’s between the quotation marks.

Tip #2: Write Realistic Dialogue

Good dialogue should sound natural. Listen to how people talk in real life and try to replicate it on the page when you write dialogue.

Don’t be afraid to break the rules of grammar, or to use an occasional exclamation point to punctuate dialogue.

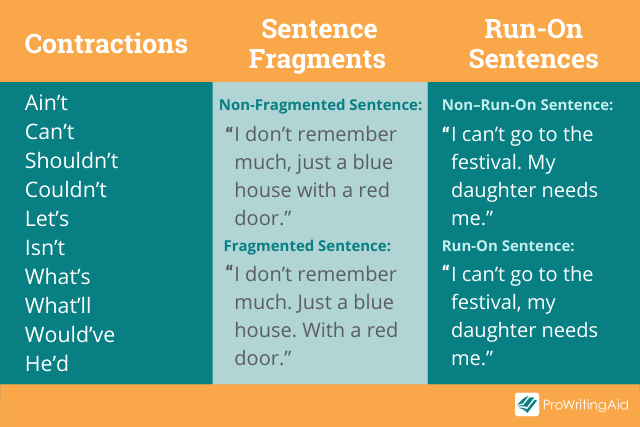

It’s okay to use contractions , sentence fragments , and run-on sentences , even if you wouldn’t use them in other parts of the story.

This doesn’t mean that realistic dialogue should sound exactly like the way people speak in the real world.

If you’ve ever read a court transcript, you know that real-life speech is riddled with “ums” and “ahs” and repeated words and phrases. A few paragraphs of this might put your readers to sleep.

Compelling dialogue should sound like a real conversation, while still being wittier, smoother, and better worded than real speech.

Tip #3: Simplify Your Dialogue Tags

A dialogue tag is anything that tells the reader which character is talking within that same paragraph, such as “she said” or “I asked.”

When you’re writing dialogue, remember that simple dialogue tags are the most effective .

Often, you can omit dialogue tags after the conversation has started flowing, especially if only two characters are participating.

The reader will be able to keep up with who’s speaking as long as you start a new paragraph each time the speaker changes.

When you do need to use a dialogue tag, a simple “he said” or “she said” will do the trick.

Our brains generally skip over the word “said” when we’re reading, while other dialogue tags are a distraction.

A common mistake beginner writers make is to avoid using the word “said.”

Characters in amateur novels tend to mutter, whisper, declare, or chuckle at every line of dialogue. This feels overblown and distracts from the actual story.

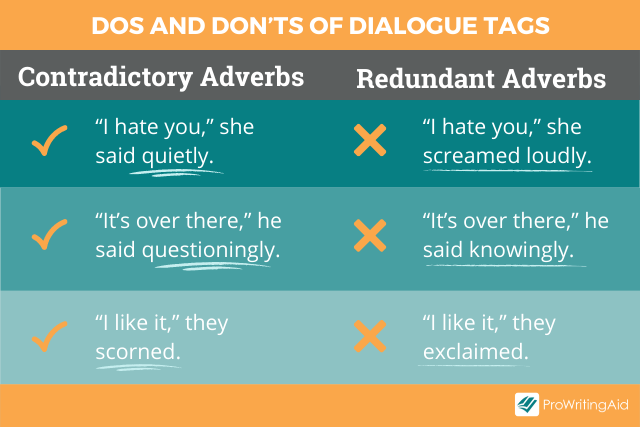

Another common mistake is to attach an adverb to the word “said.” Characters in amateur novels rarely just say things—they have to say things loudly, quietly, cheerfully, or angrily.

If you’re writing great dialogue, readers should be able to figure out whether your character is cheerful or angry from what’s within the quotation marks.

The only exception to this rule is if the dialogue tag contradicts the dialogue itself. For example, consider this sentence:

- “You’ve ruined my life,” she said angrily.

The word “angrily” is redundant here because the words inside the quotation marks already imply that the character is speaking angrily.

In contrast, consider this sentence:

- “You’ve ruined my life,” she said thoughtfully.

Here, the word “thoughtfully” is well-placed because it contrasts with what we might otherwise assume. It adds an additional nuance to the sentence inside the quotation marks.

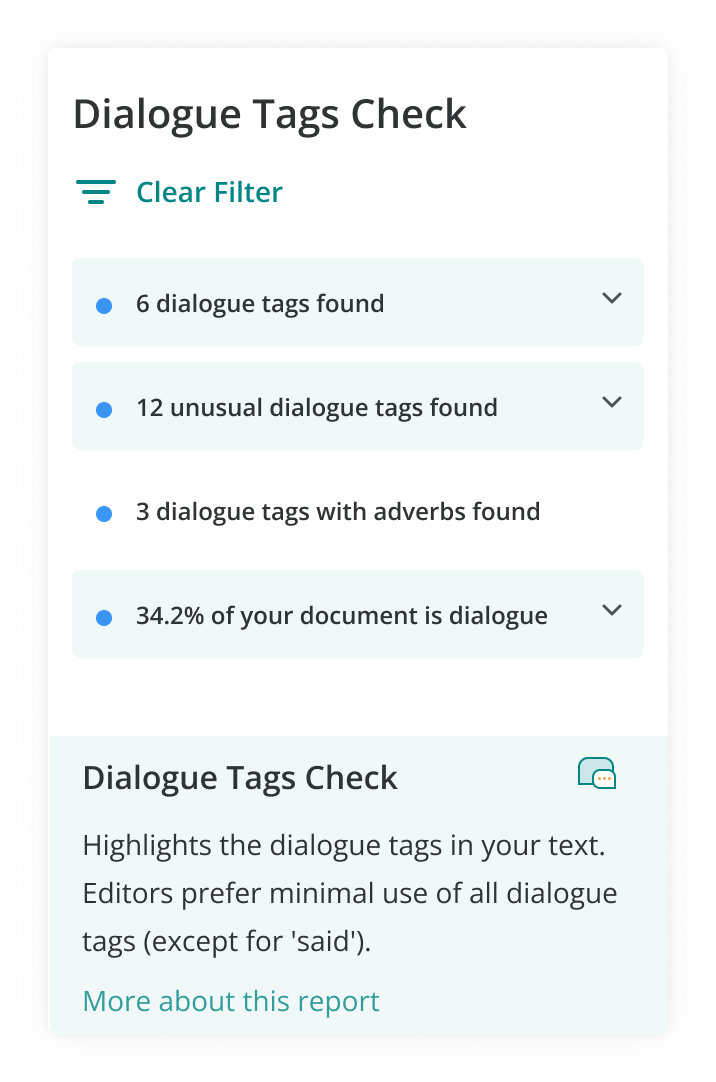

You can use the ProWritingAid dialogue check when you write dialogue to make sure your dialogue tags are pulling their weight and aren’t distracting readers from the main storyline.

Sign up for your free ProWritingAid account to check your dialogue tags today.

Tip #4: Balance Speech with Action

When you’re writing dialogue, you can use action beats —descriptions of body language or physical action—to show what each character is doing throughout the conversation.

Learning how to write action beats is an important component of learning how to write dialogue.

Good dialogue becomes even more interesting when the characters are doing something active at the same time.

You can watch people in real life, or even characters in movies, to see what kinds of body language they have. Some pick at their fingernails. Some pace the room. Some tap their feet on the floor.

Including physical action when writing dialogue can have multiple benefits:

- It changes the pace of your dialogue and makes the rhythm more interesting

- It prevents “white room syndrome,” which is when a scene feels like it’s happening in a white room because it’s all dialogue and no description

- It shows the reader who’s speaking without using speaker tags

You can decide how often to include physical descriptions in each scene. All dialogue has an ebb and flow to it, and you can use beats to control the pace of your dialogue scenes.

If you want a lot of tension in your scene, you can use fewer action beats to let the dialogue ping-pong back and forth.

If you want a slower scene, you can write dialogue that includes long, detailed action beats to help the reader relax.

You should start a separate sentence, or even a new paragraph, for each of these longer beats.

Tip #5: Write Conversations with Subtext

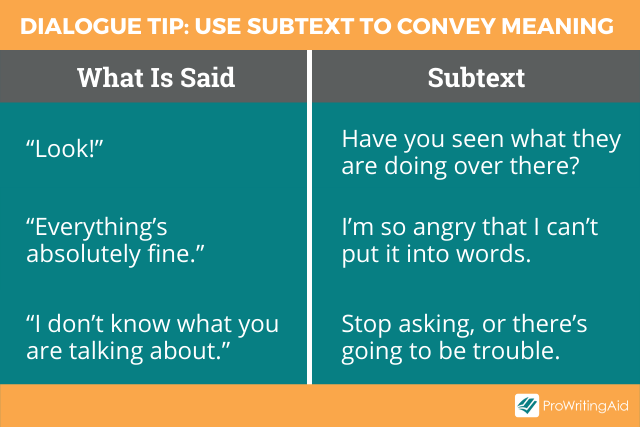

Every conversation has subtext , because we rarely say exactly what we mean. The best dialogue should include both what is said and what is not said.

I once had a roommate who cared a lot about the tidiness of our apartment, but would never say it outright. We soon figured out that whenever she said something like “I might bring some friends over tonight,” what she meant was “Please wash your dishes, because there are no clean plates left for my friends to use.”

When you’re writing dialogue, it’s important to think about what’s not being said. Even pleasant conversations can hide a lot beneath the surface.

Is one character secretly mad at the other?

Is one secretly in love with the other?

Is one thinking about tomorrow’s math test and only pretending to pay attention to what the other person is saying?

Personally, I find it really hard to use subtext when I write dialogue from scratch.

In my first drafts I let my characters say what they really mean. Then, when I’m editing, I go back and figure out how to convey the same information through subtext instead.

Tip #6: Show, Don’t Tell

When I was in high school, I once wrote a story in which the protagonist’s mother tells her: “As you know, Susan, your dad left us when you were five.”

I’ve learned a lot about the writing craft since high school, but it doesn’t take a brilliant writer to figure out that this is not something any mother would say to her daughter in real life.

The reason I wrote that line of dialogue was because I wanted to tell the reader when Susan last saw her father, but I didn’t do it in a realistic way.

Don’t shoehorn information into your characters’ conversations if they’re not likely to say it to each other.

One useful trick is to have your characters get into an argument.

You can convey a lot of information about a topic through their conflicting opinions, without making it sound like either of the characters is saying things for the reader’s benefit.

Here’s one way my high school self could have conveyed the same information in a more realistic way in just a few lines:

Susan: “Why didn’t you tell me Dad was leaving? Why didn’t you let me say goodbye?”

Mom: “You were only five. I wanted to protect you.”

Tip #7: Keep Your Dialogue Concise

Dialogue tends to flow out easily when you’re drafting your story, so in the editing process, you’ll need to be ruthless. Cut anything that doesn’t move the story forward.

Try not to write dialogue that feels like small talk.

You can eliminate most hellos and goodbyes, or summarize them instead of showing them. Readers don’t want to waste their time reading dialogue that they hear every day.

In addition, try not to write dialogue with too many trigger phrases, which are questions that trigger the next line of dialogue, such as:

- “And then what?”

- “What do you mean?”

It’s tempting to slip these in when you’re writing dialogue because they keep the conversation flowing. I still catch myself doing this from time to time.

Remember that you don’t need three lines of dialogue when one line could accomplish the same thing.

Let’s look at some dialogue examples from successful novels that follow each of our seven tips.

Dialogue Example #1: How to Create Character Voice

Let’s start with an example of a character with a distinct voice from Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets by J.K. Rowling.

“What happened, Harry? What happened? Is he ill? But you can cure him, can’t you?” Colin had run down from his seat and was now dancing alongside them as they left the field. Ron gave a huge heave and more slugs dribbled down his front. “Oooh,” said Colin, fascinated and raising his camera. “Can you hold him still, Harry?”

Most readers could figure out that this was Colin Creevey speaking, even if his name hadn’t been mentioned in the passage.

This is because Colin Creevey is the only character who speaks with such extreme enthusiasm, even at a time when Ron is belching slugs.

This snippet of written dialogue does a great job of showing us Colin’s personality and how much he worships his hero Harry.

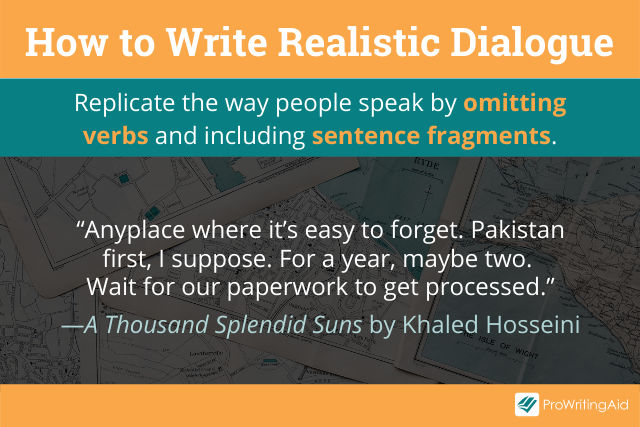

Dialogue Example #2: How to Write Realistic Dialogue

Here’s an example of how to write dialogue that feels realistic from A Thousand Splendid Suns by Khaled Hosseini.

“As much as I love this land, some days I think about leaving it,” Babi said. “Where to?” “Anyplace where it’s easy to forget. Pakistan first, I suppose. For a year, maybe two. Wait for our paperwork to get processed.” “And then?” “And then, well, it is a big world. Maybe America. Somewhere near the sea. Like California.”

Notice the punctuation and grammar that these two characters use when they speak.

There are many sentence fragments in this conversation like, “Anyplace where it’s easy to forget.” and “Somewhere near the sea.”

Babi often omits the verbs from his sentences, just like people do in real life. He speaks in short fragments instead of long, flowing paragraphs.

This dialogue shows who Babi is and feels similar to the way a real person would talk, while still remaining concise.

Dialogue Example #3: How to Simplify Your Dialogue Tags

Here’s an example of effective dialogue tags in Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier.

In this passage, the narrator’s been caught exploring the forbidden west wing of her new husband’s house, and she’s trying to make excuses for being there.

“I lost my way,” I said, “I was trying to find my room.” “You have come to the opposite side of the house,” she said; “this is the west wing.” “Yes, I know,” I said. “Did you go into any of the rooms?” she asked me. “No,” I said. “No, I just opened a door, I did not go in. Everything was dark, covered up in dust sheets. I’m sorry. I did not mean to disturb anything. I expect you like to keep all this shut up.” “If you wish to open up the rooms I will have it done,” she said; “you have only to tell me. The rooms are all furnished, and can be used.” “Oh, no,” I said. “No. I did not mean you to think that.”

In this passage, the only dialogue tags Du Maurier uses are “I said,” “she said,” and “she asked.”

Even so, you can feel the narrator’s dread and nervousness. Her emotions are conveyed through what she actually says, rather than through the dialogue tags.

This is a splendid example of evocative speech that doesn’t need fancy dialogue tags to make it come to life.

Dialogue Example #4: How to Balance Speech with Action

Let’s look at a passage from The Princess Bride by William Goldman, where dialogue is melded with physical action.

With a smile the hunchback pushed the knife harder against Buttercup’s throat. It was about to bring blood. “If you wish her dead, by all means keep moving," Vizzini said. The man in black froze. “Better,” Vizzini nodded. No sound now beneath the moonlight. “I understand completely what you are trying to do,” the Sicilian said finally, “and I want it quite clear that I resent your behavior. You are trying to kidnap what I have rightfully stolen, and I think it quite ungentlemanly.” “Let me explain,” the man in black began, starting to edge forward. “You’re killing her!” the Sicilian screamed, shoving harder with the knife. A drop of blood appeared now at Buttercup’s throat, red against white.

In this passage, William Goldman brings our attention seamlessly from the action to the dialogue and back again.

This makes the scene twice as interesting, because we’re paying attention not just to what Vizzini and the man in black are saying, but also to what they’re doing.

This is a great way to keep tension high and move the plot forward.

Dialogue Example #5: How to Write Conversations with Subtext

This example from Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card shows how to write dialogue with subtext.

Here is the scene when Ender and his sister Valentine are reunited for the first time, after Ender’s spent most of his childhood away from home training to be a soldier.

Ender didn’t wave when she walked down the hill toward him, didn’t smile when she stepped onto the floating boat slip. But she knew that he was glad to see her, knew it because of the way his eyes never left her face. “You’re bigger than I remembered,” she said stupidly. “You too,” he said. “I also remembered that you were beautiful.” “Memory does play tricks on us.” “No. Your face is the same, but I don’t remember what beautiful means anymore. Come on. Let’s go out into the lake.”

In this scene, we can tell that Valentine missed her brother terribly, and that Ender went through a lot of trauma at Battle School, without either of them saying it outright.

The conversation could have started with Valentine saying “I missed you,” but instead, she goes for a subtler opening: “You’re bigger than I remembered.”

Similarly, Ender could say “You have no idea what I’ve been through,” but instead he says, “I don’t remember what beautiful means anymore.”

We can deduce what each of these characters is thinking and feeling from what they say and from what they leave unsaid.

Dialogue Example #6: How to Show, Not Tell

Let’s look at an example from The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss. This scene is the story’s first introduction of the ancient creatures called the Chandrian.

“I didn’t know the Chandrian were demons,” the boy said. “I’d heard—” “They ain’t demons,” Jake said firmly. “They were the first six people to refuse Tehlu’s choice of the path, and he cursed them to wander the corners—” “Are you telling this story, Jacob Walker?” Cob said sharply. “Cause if you are, I’ll just let you get on with it.” The two men glared at each other for a long moment. Eventually Jake looked away, muttering something that could, conceivably, have been an apology. Cob turned back to the boy. “That’s the mystery of the Chandrian,” he explained. “Where do they come from? Where do they go after they’ve done their bloody deeds? Are they men who sold their souls? Demons? Spirits? No one knows.” Cob shot Jake a profoundly disdainful look. “Though every half-wit claims he knows...”

The three characters taking part in this conversation all know what the Chandrian are.

Imagine if Cob had said “As we all know, the Chandrian are mysterious demon-spirits.” We would feel like he was talking to us, not to the two other characters.

Instead, Rothfuss has all three characters try to explain their own understanding of what the Chandrian are, and then shoot each other’s explanations down.

When Cob reprimands Jake for interrupting him and then calls him a half-wit for claiming to know what he’s talking about, it feels like a realistic interaction.

This is a clever way for Rothfuss to introduce the Chandrian in a believable way.

Dialogue Example #7: How to Keep Your Dialogue Concise

Here’s an example of concise dialogue from The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger.

“Do you blame me for flunking you, boy?” he said. “No, sir! I certainly don’t,” I said. I wished to hell he’d stop calling me “boy” all the time. He tried chucking my exam paper on the bed when he was through with it. Only, he missed again, naturally. I had to get up again and pick it up and put it on top of the Atlantic Monthly. It’s boring to do that every two minutes. “What would you have done in my place?” he said. “Tell the truth, boy.” Well, you could see he really felt pretty lousy about flunking me. So I shot the bull for a while. I told him I was a real moron, and all that stuff. I told him how I would’ve done exactly the same thing if I’d been in his place, and how most people didn’t appreciate how tough it is being a teacher. That kind of stuff. The old bull.

Here, the last paragraph diverges from the prior ones. After the teacher says “Tell the truth, boy,” the rest of the conversation is summarized, rather than shown.

The summary of what the narrator says in the last paragraph—“I told him I was a real moron, and all that stuff”—serves to hammer home that this is the type of “old bull” that the narrator has fed to his teachers over and over before.

It doesn’t need to be shown because it’s not important to the narrator—it’s just “all that stuff.”

Salinger could have written out the entire conversation in dialogue, but instead he kept the dialogue concise.

Final Words

Now you know how to write clear, effective dialogue! Start with the basic rules for dialogue and try implementing the more advanced tips as you go.

What are your favorite dialogue tips? Let us know in the comments below.

Do you know how to craft memorable, compelling characters? Download this free book now:

Creating Legends: How to Craft Characters Readers Adore… or Despise!

This guide is for all the writers out there who want to create compelling, engaging, relatable characters that readers will adore… or despise., learn how to invent characters based on actions, motives, and their past..

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Improve your writing in one of the largest and most successful writing groups online

Join our writing community!

How to Write Dialogue: Rules, Examples, and 8 Tips for Engaging Dialogue

by Fija Callaghan

You’ll often hear fiction writers talking about “character-driven stories”—stories where the strengths, weaknesses, and aspirations of the central cast of characters stay with us long after the book is closed. But what drives character, and how do we create characters that leave long-lasting impressions?

The answer lies in dialogue : the device used by our characters to communicate with each other. Powerful dialogue can elevate a story and subtly reveal important information, but poorly written dialogue can send your work straight to the slush bin. Let’s look at what dialogue is in writing, how to properly format dialogue, and how to make your characters’ dialogue the best it can be.

What is dialogue in a story?

Dialogue is the verbal exchange between two or more characters. In most fiction, the exchange is in the form of a spoken conversation. However, conversations in a story can also be things like letters, text messages, telepathy, or even sign language. Any moment where two characters speak or connect with each other through their choice of words, they’re engaging in dialogue.

Why does dialogue matter in a story?

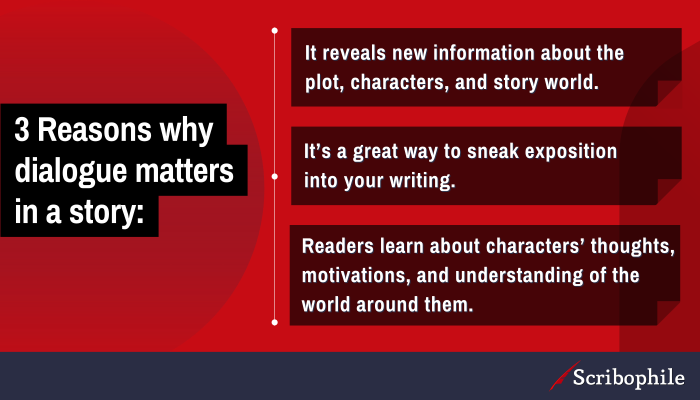

We use dialogue in a story to reveal new information about the plot, characters, and story world. Great dialogue is essential to character development and helps move the plot forward in a story.

Writing good dialogue is a great way to sneak exposition into your story without stating it overtly to the reader; you can also use tools like dialect and diction in your dialogue to communicate more detail about your characters.

Through a character’s dialogue, we can learn about their motivations, relationships, and understanding of the world around them.

A character won’t always say what they mean (more on dialogue subtext below), but everything they say will serve some larger purpose in the story. If your dialogue is well-written, the reader will absorb this information without even realizing it. If your dialogue is clunky, however, it will stand out and pull your reader away from your story.

Rules for writing dialogue

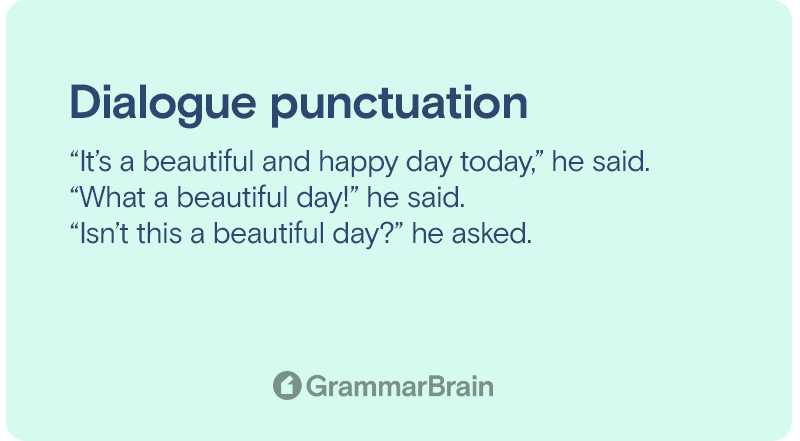

Before we get into how to make your dialogue realistic and engaging, let’s make sure you’ve got the basics down: how to properly format dialogue in a story. We’ll look at how to punctuate dialogue, how to write dialogue correctly when using a question mark or exclamation point, and some helpful dialogue writing examples.

Here are the need-to-know rules for formatting dialogue in writing.

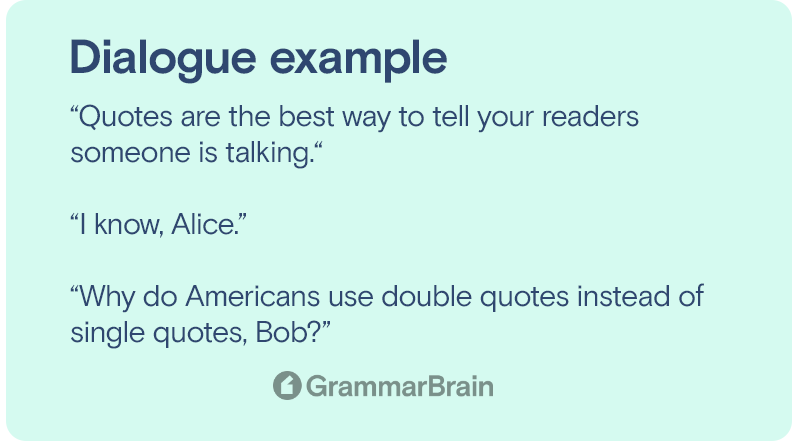

Enclose lines of dialogue in double quotation marks

This is the most essential rule in basic dialogue punctuation. When you write dialogue in North American English, a spoken line will have a set of double quotation marks around it. Here’s a simple dialogue example:

“Were you at the party last night?”

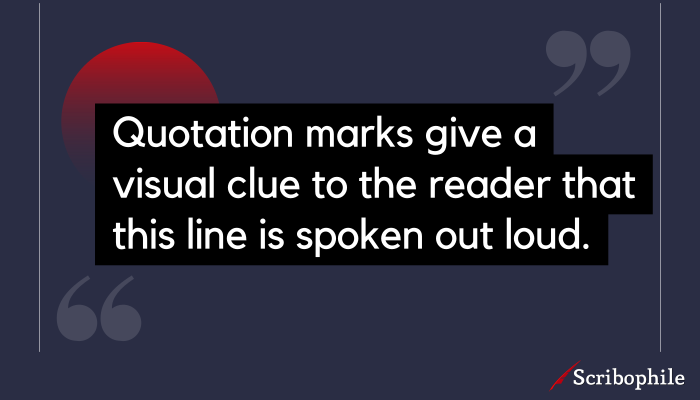

Any punctuation such as periods, question marks, and exclamation marks will also go inside the quotation marks. The quotation marks give a visual clue to the reader that this line is spoken out loud.

In European or British English, however, you’ll often see single quotation marks being used instead of double quotation marks. All the other rules stay the same.

Enclose nested dialogue in single quotation marks

Nested dialogue is when one line of dialogue happens inside another line of dialogue—when someone is verbally quoting someone else. In North American English, you’d use single quotation marks to identify where the new dialogue line starts and stops, like this:

“And then, do you know what he said to me? Right to my face, he said, ‘I stayed home all night.’ As if I didn’t even see him.”

The double and single quotation marks give the reader clues as to who’s speaking. In European or British English, the quotation marks would be reversed; you’d use single quotation marks on the outside, and double quotation marks on the inside.

Every speaker gets a new paragraph

Every time you switch to a new speaker, you end the line where it is and start a new line. Here are some dialogue examples to show you how it looks:

“Were you at the party last night?” “No, I stayed home all night.”

The same is true if the new “speaker” is only in focus because of their action. You can think of the paragraphs like camera angles, each one focusing on a different person:

“Were you at the party last night?” “No, I stayed home all night.” She raised a single, threatening eyebrow. “Yeah, I wasn’t feeling that well, so I just stayed in and watched Netflix instead.”

If you kept the action on the same line as the dialogue, it would get confusing and make it look like she was the one saying it. Giving each character a new paragraph keeps the speakers clear and distinct.

Use em-dashes when dialogue gets cut short

If your character begins to speak but is interrupted, you’ll break off their line of dialogue with an em-dash, like this:

“Yeah, I wasn’t feeling that well, so I just stayed in and—” “Is that really what happened?”

Be careful with this one, because many word processors will treat your em-dash like the beginning of a new sentence and attach your closing quotation marks backwards:

“Yeah, I wasn’t feeling that well, so I just stayed in and—“

You may need to keep an eye out and adjust as you go along.

In this dialogue example, the new speaker doesn’t lead with an em-dash; they just start speaking like normal. The only time you’ll ever open a line of dialogue with an em-dash is if the speaker who’s been cut off continues with what they were saying:

“Yeah, I wasn’t feeling that well, so I just stayed in and—” “Is that really what happened?” “—watched Netflix instead. Yes, that’s what happened.”

This shows the reader that there’s actually only one line of dialogue, but it’s been cut in the middle by another speaker.

Each line of dialogue is indented

Every time you give your speaker a new paragraph, it’s indented from the left-hand side. Many word processors will do this automatically. The only exception is if your dialogue is opening your story or a new section of your story, such as a chapter; these will always start at the far left margin of the page, whether they’re dialogue or narration.

Long speeches don’t use use closing quotation marks until the end

Most writers favor shorter lines of dialogue in their writing, but sometimes you might need to give your character a longer one—for instance, if the character speaking is giving a speech or telling a story. In these cases, you might choose to break up their speech into shorter paragraphs the way you would if you were writing regular narrative.

However, here the punctuation gets a bit weird. You’ll begin the character’s dialogue with a double quotation mark, like normal. But you won’t use a double quotation mark at the end of the paragraph, because they haven’t finished speaking yet. But! You’ll use another opening quotation mark at the beginning of the subsequent paragraph. This means that you may use several opening double quotation marks for your character’s speech, but only ever one closing quotation mark.

If your character is telling a story that involves people talking, remember to use single quotation marks for your dialogue-within-dialogue as we looked at above.

Sometimes these dialogue formatting rules are easier to catch later on, during the editing process. When you’re writing, worry less about using the exact dialogue punctuation and more about writing great dialogue that supports your character development and moves the story forward.

How to use dialogue tags

Dialogue tags help identify the speaker. They’re especially important if you have a group of people all talking together, and it can get pretty confusing for the reader trying to keep everybody straight. If you’re using a speech tag after your line of dialogue—he said, she said, and so forth—you’ll end your sentence with a comma, like this:

“No, I stayed home all night,” he said.

But if you’re using an action to identify the person speaking instead, you’ll punctuate the sentence like normal and start a new sentence to describe the action taking place:

“No, I stayed home all night.” He looked down at his feet.

The dialogue tags and action tags always follow in the same paragraph. When you move your story lens to a new person, you’ll switch to a new paragraph. Each line where a new person speaks propels the story forward.

When to use capitals in dialogue tags

You may have noticed in the two examples above that one dialogue tag begins with a lowercase letter, and one—which is technically called an action tag—begins with a capital letter. Confusing? The rules are simple once you get a little practice.

When you use a dialogue tag like “he said,” “she said,” “he whispered,” or “she shouted,” you’re using these as modifiers to your sentence—dressing it up with a little clarity. They’re an extension of the sentence the person was speaking. That’s why you separate them with a comma and keep going.

With an action tag , you’re ending one sentence and beginning a whole new one. Each sentence represents two distinct moments in the story. That’s why you end the first sentence with a period, and then open the next one with a capital letter.

If you’re not sure, try reading them out loud:

“No, I stayed home all night,” he said. “No, I stayed home all night.” He looked down at his feet.

Since you can’t hear quotation marks out loud, the way you say them will show you if they’re one sentence or two. In the first example, you can hear how the sentence keeps going after the dialogue ends. In the second example, you can hear how one sentence comes to a full stop and another one begins.

But what if your dialogue tag comes before the dialogue, instead of after? In this case, the dialogue is always capitalized because the speaker is beginning a new sentence:

He said, “No, I stayed home all night.” He looked down at his feet. “No, I stayed home all night.”

You’ll still use a comma after the dialogue tag and a period after the action tag, just like if you’d separate them if you were putting your tag at the end.

If you’re not sure, ask yourself if your leading tag sounds like a full sentence or a partial sentence. If it sounds like a partial sentence, it gets a comma. If it reads like a full sentence that stands on its own, it gets a period.

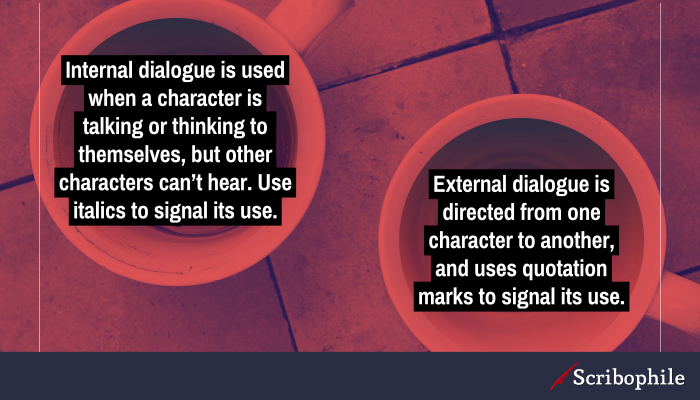

External vs. internal dialogue

All of the dialogue we’ve looked at so far is external dialogue, which is directed from one character to another. The other type of dialogue is internal dialogue, or inner dialogue, where a character is talking to themselves. You’ll use this when you want to show what a character is thinking, but other characters can’t hear.

Usually, internal dialogue will be written in italics to distinguish it from the rest of the text. That shows the reader that the line is happening inside the character’s head. For example:

It’s not a big deal, she thought. It’s just a new school. It’ll be fine. I’ll be fine.

Here you can see that the dialogue tag is used in the same way, just as if it was a line of external dialogue. However, “she thought” is written in regular text because it’s not a part of what the character is thinking. This helps keep everything clear for the reader.

In your story, you can play with using contrasting internal and external dialogue to show that what your characters say isn’t always what they mean. You may also choose to use this internal dialogue formatting if you’re writing dialogue between two or more characters that isn’t spoken out loud—for instance, telepathically or by sign language.

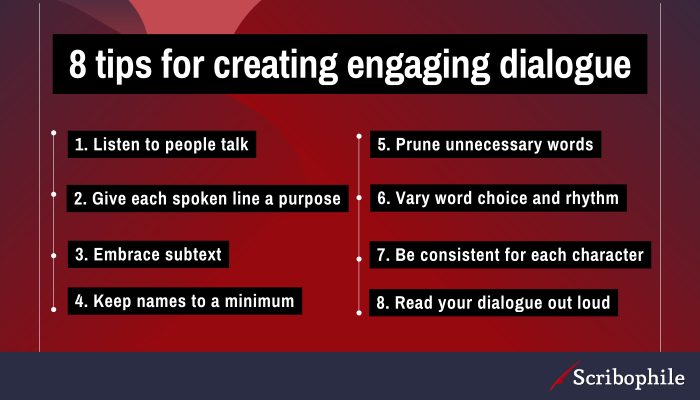

8 tips for creating engaging dialogue in a story

Now that you’ve mastered the mechanics of how to write dialogue, let’s look at how to create convincing, compelling dialogue that will elevate your story.

1. Listen to people talk

To write convincingly about people, you’ll first need to know something about them. The work of great writers is often characterized by their insight into humanity; you read them and think, “Yes, this is exactly what people are like.” You can begin accumulating your own insight by listening to what real people say to each other.

You can go to any public place where people are likely to gather and converse: cafés, art galleries, political events, dimly lit pubs, bookshops. Record snippets of conversation, pay attention to how people’s voices change as they move from speaking to one person to another, try to imagine what it is they’re not saying, the words simmering just under the surface.

By listening to stories unfold in real time, you’ll have a better idea of how to recreate them in your writing—and inspiration for some new stories, too.

2. Give each spoken line a purpose

Here is something that actors have drilled into their heads from their first day at drama school, and writers would do well to remember it too: every single line of dialogue has a hidden motivation. Every time your character speaks, they’re trying to achieve something, either overtly or covertly.

Small talk is rare in fiction, because it doesn’t advance the plot or reveal something about your characters. The exception is when your characters are using their small talk for a specific purpose, such as to put off talking about the real issue, to disarm someone, or to pretend they belong somewhere they don’t.

When writing your own dialogue, ask yourself what the line accomplishes in the story. If you come up blank, it probably doesn’t need to be there. Words need to earn their place on the page.

3. Embrace subtext

In real life, we rarely say exactly what we really mean. The reality of polite society is that we’ve evolved to speak in circles around our true intentions, afraid of the consequences of speaking our mind. Your characters will be no different. If your protagonist is trying to tell their best friend they’re in love with them, for instance, they’ll come up with about fifty different ways to say it before speaking the deceptively simple words themselves.

To write better dialogue, try exploring different ways of moving your characters around what’s really being said, layering text and subtext side by side. The reader will love picking apart the conversation between your characters and deducing what’s really happening underneath (incidentally, this is also the place where fan fiction is born).

4. Keep names to a minimum

You may notice that on television, in moments of great upheaval, the characters will communicate exactly how important the moment is by saying each other’s names in dramatic bursts of anger/passion/fear/heartbreak/shock. In real life, we say each other’s names very rarely; saying someone’s name out loud can actually be a surprisingly intimate experience.

Names may be a necessary evil right at the beginning of your story so your reader knows who’s who, but after you’ve established your cast, try to include names in dialogue only when it makes sense to do so. If you’re not sure, try reading the dialogue out loud to see if it sounds like something someone would actually say (we’ll talk more about reading out loud below).

5. Prune unnecessary words

This is one area where reality and story differ. In life, dialogue is full of filler words: “Um, uh, well, so yeah, then I was like, erm, huh?” You may have noticed this when you practiced listening to dialogue, above. We won’t say there’s never a place for these words in fiction, but like all words in storytelling, they need to earn their place. You might find filler words an effective tool for showing something about one particular character, or about one particular moment, but you’ll generally find that you use them a lot less than people really do in everyday speech.

When you’re reviewing your characters’ dialogue, remember the hint above: each line needs a purpose. It’s the same for each word. Keep only the ones that contribute something to the story.

6. Vary word choices and rhythms

The greatest dialogue examples in writing use distinctive character voices; each character sounds a little bit different, because they have their own personality.

This can be tricky to master, but an easy way to get started is to look at the word choice and rhythm for each character. You might have one character use longer words and run-on sentences, while another uses smaller words and simple, single-clause sentences. You might have one lean on colloquial regional dialect, where another sounds more cosmopolitan. Play around with different ways to develop characters and give each one their own voice.

7. Be consistent for each character

When you do find a solid, believable voice for your character, make sure that it stays consistent throughout your entire story. It’s easy to set a story aside for a while, then return to it and forget some of the work you did in distinguishing your characters’ dialogue. You might find it helpful to write down some notes about the way each character speaks so you can refer back to it later.

The exception, of course, is if your character’s speech pattern goes through a transformation over the course of the story, like Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady . In this case, you can use your character’s distinctive voice to communicate a major change. But as with all things in writing, make sure that it comes from intention and not from forgetfulness.

8. Read your dialogue out loud

After you’ve written a scene between two or more characters, you can take the dialogue for a trial run by speaking it out loud. Ask yourself, does the dialogue sound realistic? Are there any moments where it drags or feels forced? Does the voice feel natural for each character? You’ll often find there are snags you miss in your writing that only become apparent when read out loud. Bonus: this is great practice for when you become rich and famous and do live readings at bookshops.

3 mistakes to avoid when writing dialogue

Easy, right? But there are also a few pitfalls that new writers often encounter when writing dialogue that can drag down an otherwise compelling story. Here are the things to watch out for when crafting your story dialogue.

1. Too much exposition

Exposition is one of the more demanding literary devices , and one of the ones most likely to trip up new writers. Dialogue is a good place to sneak in some information about your story—but subtlety is essential. This is one place where the adage “show, don’t tell” really shines.

Consider these dialogue examples:

“How is she, Doctor?” “Well Mr. Stuffington, I don’t have to remind you that your daughter, the sole heiress to your estate and currently engaged to the Baron of Flippingshire, has suffered a grievous injury when she fell from her horse last Sunday. We don’t need to discuss right now whether or not you think her jealous maid was responsible; what matters is your daughter’s well being. As to your question, I’m afraid it’s very unlikely that she’ll ever walk again.” Can’t you just feel your arm aching to throw the poor book across the room? There’s a lot of important information here, but you can find subtler ways to work it into your story. Let’s try again: “How is she, Doctor?” “Well Mr. Stuffington, your daughter took quite a blow from that horse—worse than we initially thought. I’m afraid it’s very unlikely that she’ll ever walk again.” “And what am I supposed to say to Flippingshire?” “The Baron? I suppose you’ll have to tell him that his future wife has lost the use of her legs.”

And so forth. To create good dialogue exposition, look for little ways to work in the details of your story, instead of piling it up in one great clump.

2. Too much small talk

We looked at how each line of dialogue needs a specific purpose above. Very often small talk in a story happens because the writer doesn’t know what the scene is about. Small talk doesn’t move the scene along unless it’s there for a reason. If you’re not sure, ask yourself what each character wants in this moment.

For example, imagine you’re in an office, and two characters are talking by the water cooler. How was your weekend, what did you think of the game, how’s your wife doing, are those new shoes, etc etc. Can’t you just feel the reader’s will to live slipping away?

But what about this: your characters are talking by the water cooler—Character A and Character B. Character A knows that his friend is inside Character B’s office looking for evidence of corporate espionage, so A is doing everything he can to stop B from going in. How was your weekend, what did you think of the game, how’s your wife doing, are those new shoes, literally anything just to keep him talking. Suddenly these benign little phrases have a purpose.

If you find your characters slipping into small talk, double check that it’s there for a purpose, and not just a crutch to keep you from moving forward in your scene. When writing dialogue, Make each line of dialogue earn its place.

3. Too much repetition

Variation is the spice of a good story. To keep your readers engaged, avoid using the same sentence structure and the same dialogue tags over and over again. Using “he said” and “she said” is effective and clear cut, but only for about three beats. After that, try switching to an action tag instead or letting the line of dialogue stand on its own.

You can also experiment with varying the length of your sentences or groupings of sentences. By changing up the rhythm of your story regularly, you’ll keep it feeling fresh and present for the reader.

Effective dialogue examples from literature

With all of these tips and tricks in mind, let’s look at how other writers have used good dialogue to elevate their stories.

Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine , by Gail Honeyman

“I’m going to pick up a carryout and head round to my mate Andy’s. A few of us usually hang out there on Saturday nights, fire up the playstation, have a smoke and a few beers.” “Sounds utterly delightful,” I said. “What about you?” he asked. I was going home, of course, to watch a television program or read a book. What else would I be doing? “I shall return to my flat,” I said. “I think there might be a documentary about komodo dragons on BBC4 later this evening.”

In this dialogue example, the author gives her characters two very distinctive voices. From just a few words we can begin to see these people very clearly in our minds—and with this distinction comes the tension that drives the story. Dialogue is an excellent place to show your character dynamics using speech patterns and word choices.

Pride and Prejudice , by Jane Austen

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?” Mr. Bennet replied that he had not. “But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.” Mr. Bennet made no answer. “Do you not want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently. “You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.” This was invitation enough. “Why, my dear, you must know, Mrs. Long says that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England; that he came down on Monday in a chaise and four to see the place, and was so much delighted with it, that he agreed with Mr. Morris immediately; that he is to take possession before Michaelmas, and some of his servants are to be in the house by the end of next week.”

In this famous dialogue example, the author illustrates the relationship between these two characters clearly and succinctly. Their dialogue shows Mr. B’s stalwart, tolerant love for his wife and Mrs. B’s excitement and propensity for gossip. The author shows us everything we need to know about these people in just a few lines.

Dinner in Donnybrook , by Maeve Binchy

“Look, I thought you ought to know, we’ve had a very odd letter from Carmel.” “A what… from Carmel?” “A letter. Yes, I know it’s sort of out of character, I thought maybe something might be wrong and you’d need to know…” “Yes, well, what did she say, what’s the matter with her?” “Nothing, that’s the problem, she’s inviting us to dinner.” “To dinner?” “Yes, it’s sort of funny, isn’t it? As if she wasn’t well or something. I thought you should know in case she got in touch with you.” “Did you really drag me all the way down here, third years are at the top of the house you know, I thought the house had burned down! God, wait till I come home to you. I’ll murder you.” “The dinner’s in a month’s time, and she says she’s invited Ruth O’Donnell.” “Oh, Jesus Christ.”

This dialogue example is a telephone conversation between two people. The lack of dialogue tags or action tags allows the words to come to the forefront and immerses us in their back-and-forth conversation. Even though there are no tags to indicate the speakers, the language is simple and straightforward enough that the reader always knows who’s talking. Through this conversation the author slowly builds the tension from the benign to the catastrophic within a domestic setting.

Compelling dialogue is the key to a good story

A writer has a lot riding on their characters’ dialogue, and learning how to write dialogue is a critical skill for any writer. When done well, it can leaves a lasting impact on the reader. But when dialogue is clumsy and awkward, it can drag your story down and make your reader feel like they’re wasting their time.

But if you keep these tips in mind, listen to dialogue in your everyday life, and practice , you’ll be sure to create realistic dialogue that brings your story to life.

Get feedback on your writing today!

Scribophile is a community of hundreds of thousands of writers from all over the world. Meet beta readers, get feedback on your writing, and become a better writer!

Join now for free

Related articles

Writing Effective Dialogue: Advanced Techniques

What is Alliteration? Definition, examples and tips

What is a Writer’s Voice & Tips for Finding Your Writing Voice

Dialogue Tag Format: What are Speech Tags? With Examples

What is Dialect in Literature? Definition and Examples

Nonfiction Writing Checklist for Your Book

Enter a search request and press enter. Press Esc or the X to close.

- Bookfox Academy (All Courses)

- Write Your Best Novel

- How to Write a Splendid Sentence

- Two Weeks to Your Best Children’s Book

- Revision Genius

- The Ultimate Guide to Writing Dialogue

- Your First Bestseller

- Master Your Writing Habits

- Writing Techniques to Transform Your Fiction

- Triangle Method of Character Development

- Children’s Book Editing

- Copy Editing

- Novel Editing

- Short Story Editing

- General Books

- Children’s Books

50 Examples of Dialogue to Inspire Writers

This post isn’t about how to punctuate dialogue, or the basics of how to write dialogue, but more advanced techniques, as shown by established authors.

It doesn’t matter what genre you write: every writer needs to improve their dialogue. And whether you’re writing a novel or working on a short story, the examples below will help you.

After all, dialogue is where characters come alive, and characters are the heartbeat of fiction.

These fifty examples of excellent dialogue include everything from writing comic dialogue to writing dialogue between two people (and three people!), and focuses exclusively on fiction.

1. Use Ellipsis to Avoid Saying Hard Things

A Visit from the Goon Squad, Jennifer Egan