The countries in which the process of development has started but is not completed, have a developing phase of different economic aspects or dimensions like per capita income or GDP per capita, human development index (HDI), living standards, fulfillment of basic needs, and so on. The UN identifies developing countries as a country with a relatively low standard of living, underdeveloped industrial bases, and moderate to low human development index. Therefore, developing nations are those nations of the world, which have lower per capita income as compared to developed nations like the USA, Germany, China, Japan, etc. Here we will discuss the different characteristics of developing countries of the world.

Developing countries have been suffering from common attributes like mass poverty, high population growth, lower living standards, illiteracy, unemployment and underemployment, underutilization of resources, socio-political variability, lack of good governance, uncertainty, and vulnerability, low access to finance, and so on.

Developing countries are sometimes also known as underdeveloped countries or poor countries or third-world countries or less developed countries or backward countries. These countries are in a hurry for economic development by utilizing their resources. However, they are lagging in the race of development and instability. The degree of uncertainty and vulnerability in these countries may differ from one to another but all are facing some degree of susceptibility and struggle to develop.

The common characteristics of developing nations are briefly explained below.

Major Characteristics of Developing Countries

Low Per Capita Real Income

The real per capita income of developing countries is very low as compared to developed countries. This means the average income or per person income of developing nations is little and it is not sufficient to invest or save. Therefore, low per capita income in developing countries results in low savings, and low investment and ultimately creates a vicious cycle of poverty. This is one of the most serious problems faced by underdeveloped countries.

Mass Poverty

Most individuals in developing nations have been suffering from the problem of poverty. They are not able to fulfill even their basic needs. The low per capita in developing nations also reflects the problem of poverty. So, poverty in underdeveloped countries is seen in terms of lack of fulfillment of basic needs, illiteracy, unemployment, and lack of other socio-economic participation and access apart from low per capita income.

Rapid Population Growth

Developing countries have either a high population growth rate or a larger size of population. There are different factors behind higher population growth in developing countries. The higher child and infant mortality rates in such countries compel people to feel insured and give birth to more children. Lack of family planning education and options, lack of sex education, and belief that additional kids mean additional labor force and additional labor force means additional income and wealth, etc. also stimulate people in developing countries to give birth to more children. This is also supported by the thought of conservatism existed in such nations.

The Problem of Unemployment and Underemployment

Unemployment and underemployment are other major problems and common features of developing or underdeveloped nations. The problem of unemployment and underemployment in developing countries is emerged due to excessive dependency on agriculture, low industrial development, lack of proper utilization of natural resources, lack of workforce planning, and so on. In developing nations, the problem of underemployment is more serious than unemployment. People are compelled to engage themselves in inferior jobs due to the non-availability of alternative sources of jobs. The underemployment problem in high extent is found especially in rural and back warded areas of such countries.

Excessive Dependence on Agriculture

The majority of the population in developing nations is engaged in the agriculture sector, especially in rural areas. Agriculture is the only sole source of income and employment in such nations. This sector has also a higher share of the gross domestic product in poor countries. In the case of the South Asian economies, more than 70 percent population is, directly and indirectly, engaged in the agriculture sector.

Technological Backwardness

The development of a nation is a positive and increasing function of innovative technology. Technological use in developing countries is very low and used technology is also outdated. This causes a high cost of production and a high capital-output ratio in underdeveloped nations. Because of the high capital-output ratio, high labor-output ratio, and low wage rates, the input productivity is low and that reduces the gross domestic product of the nations. Illiteracy, lack of proper education, lack of skill development programs, and deficiency of capital to install innovative techniques are some of the major causes of technological backwardness in developing nations.

Dualistic Economy

Duality or dualism means the existence of two sectors as the modern sector or advanced sector and the traditional or back warded sector within an economy that operates side by side. Most developing countries are characterized by the existence of dualism. Urban sectors are highly advanced and rural parts are having the problems like a lack of social and economic facilities. People in rural areas are majorly engaged in the agriculture sector and in urban areas they are in the service and industrial sectors of the economy.

Lack of Infrastructures

Infrastructural development like the development of transportation, communication, irrigation, power, financial institutions, social overheads, etc. is not well developed in developing nations. Moreover, developed infrastructure is also unmanaged, and not distributed efficiently and equitably. This has created a threat to development in such nations.

Lower Productivity

In developing nations, the productivity of factors is also low. This is due to a lack of capital and managerial skills for getting innovative technologies, and policies and managing them efficiently. Malnutrition, insufficient health care, a healthy support system, living in an unhygienic environment, poor health and work-life of workers, etc. are factors that are attributed to lower productivity in developing nations.

High Consumption and Low Saving

In developing countries, income is low and this causes a high propensity to consume, a low propensity to save and capital formation is also low. People living in such nations have been facing the problems of poverty and they are being unable to fulfill most of their needs. This will compel them to expend more portion of their income on consumption. The higher portion of consumption out of earned income results in a lower saving rate and consequently lower capital formation. Ultimately these countries will depend on foreign aid, loans, and remittance earnings that have limited utility to expand the economy.

The above-explained points show the state and characteristics of developing countries. Apart from explained points, excessive dependency on developed nations, having inadequate provisions of social services like education facilities, health facilities, safe drinking water distribution, sanitation, etc., and dependence on primary exports due to lack of development and expansion of secondary and tertiary sectors of the economy, etc. are also major characteristics of developing countries of the world. These countries are affected more severely by the economic crisis derived from the coronavirus of 2020. So, challenges to development for developing nations have been added furthermore. In a summary, the major characteristics of developing countries are presented in the following table.

Ahuja, H.L (2016). Advanced Economic Theory . New Delhi: S Chand and Company Limited.

Todaro, M.P. & Smith, S.C. (2009). Economic Development . New York: Pearson Education.

6 thoughts on “Characteristics of Developing Countries”

Pingback: Is Thailand a Developing Country? – Thailand Trip Expert

thanks for the reality points they have fully drawn a picture of poverty. my question is how can dualistic economy be handled as away of reducing poverty?

I really enjoyed reading this So true

The lesson is so nice I understand and I enjoy the lesson

The lesson is good and points are easy to understand and master Thank you for the good services

These are indicators of poverty as proposed by the Global North’s perception of poverty in Global South. Why not ask the Global South to give their voice to what define poverty in their right.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Privacy Overview

Insert/edit link.

Enter the destination URL

Or link to existing content

Common Characteristics of Developing Countries | Economics

Following are some of the basic and important characteristics which are common to all developing economies:

An idea of the characteristics of a developing economy must have been gathered from the above analysis of the definitions of an underdeveloped economy. Various developing countries differ a good deal from each other. Some countries such as countries of Africa do not face problem of rapid population growth, others have to cope with the consequences of rapid population growth. Some developing countries are largely dependent on exports of primary products, others do not show such dependence, and others do not show such dependence.

Some developing countries have weak institutional structure such as lack of property rights, absence of the rule of law and political instability which affect incentives to invest. Besides, there are lot of differences with regard to levels of education, health, food production and availability of natural resources. However, despite this great diversity there are many common features of the developing economies. It is because of common characteristics that their developmental problems are studied within a common analytical framework of development economics.

Characteristic # 1. Low Per Capita Income :

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The first important feature of the developing countries is their low per capita income. According to the World Bank estimates for the year 1995, average per capita income of the low income countries is $ 430 as compared to $ 24,930 of the high-income countries including U.S.A., U.K., France and Japan. According to these estimates for the year 1995, per capita income was $340 in India, $ 620 in China, $240 in Bangladesh, $ 700 in Sri Lanka. As against these, for the year 1995 per capita income was $ 26,980 in USA, $ 23,750 in Sweden, $ 39,640 in Japan and 40,630 in Switzerland.

It may however be noted that the extent of poverty prevailing in the developing countries is not fully reflected in the per capita income which is only an average income and also includes the incomes of the rich also. Large inequalities in income distribution prevailing in these economies have made the lives of the people more miserable. A large bulk of population of these countries lives below the poverty line.

For example, the recent estimates reveal that about 28 per cent of India’s population (i.e. about 260 million people) lives below the poverty line, that is, they are unable to get even sufficient calories of food needed for minimum subsistence, not to speak of minimum clothing and housing facilities. The situation in other developing countries is no better.

The low levels of per capita income and poverty in developing countries is due to low levels of productivity in various fields of production. The low levels of productivity in the developing economies has been caused by dominance of low-productivity agriculture and informal sectors in their economies, low levels of capital formation – both physical and human (education, health), lack of technological progress, rapid population growth which are in fact the very characteristics of the underdeveloped nature of the developing economies. By utilising their natural resources accelerating rate of capital formation and making progress in technology they can increase their levels of productivity and income and break the vicious circle of poverty operating in them.

It may however be noted that after the Second World War and with getting political freedom from colonial rule, in a good number of the underdeveloped countries the process of growth has been started and their gross domestic product (GDP) and per capita income are increasing.

Characteristic # 2. Excessive Dependence on Agriculture :

A developing country is generally predominantly agricultural. About 60 to 75 per cent of its population depends on agriculture and its allied activities for its livelihood. Further, about 30 to 50 per cent of national income of these countries is obtained from agriculture alone. This excessive dependence on agriculture is the result of low productivity and backwardness of their agriculture and lack of modern industrial growth.

In the present-day developed countries, the modern industrial growth brought about structural transformation with the proportion of working population engaged in agriculture falling drastically and that employed in the modern industrial and services sectors rising enormously. This occurred due to the rapid growth of the modern sector on the one hand and tremendous rise in productivity in agriculture on the other.

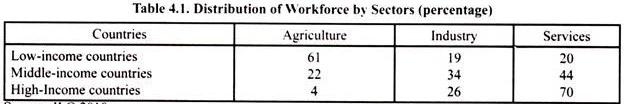

The dominance of agriculture in developing countries can be known from the distribution of their workforce by sectors. According to estimates made by ILO given in Table 4.1 on an average 61 per cent of workforce of low-income developing countries was employed in agriculture whereas only 19 per cent in industry and 20 per cent in services. On the contrary, in high income, that is, developed countries only 4 per cent of their workforce is employed in agriculture, while 26 per cent of their workforce is employed in industry and 70 per cent in services.

IvyPanda . (2023) '119 Developing Countries Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 26 September.

IvyPanda . 2023. "119 Developing Countries Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/developing-countries-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "119 Developing Countries Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/developing-countries-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "119 Developing Countries Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/developing-countries-essay-topics/.

- Economic Topics

- Third World Countries Research Ideas

- Demography Paper Topics

- Poverty Essay Titles

- Immigration Titles

- Birth control Questions

- Refugee Paper Topics

- Agriculture Essay Ideas

- Capitalism Paper Topics

- Deforestation Research Ideas

- Child Labour Research Topics

- Equality Topics

- Famine Essay Titles

- Gender Discrimination Research Topics

- Macroeconomics Topics

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Lecture 2 Major Characteristics of Developing Countries

Related Papers

MISHECK PHIRI

Social Indicators Research

Luigi Biggeri

zenebe birhanu

Renz Marion Viernes

Ronald Cherutich

Julkur knine Bahlull

Morrisson Christian

chaliweme mbofwana

Md. Lutfur Rahman

Hussein A B D E L A Z I Z Mubarak

There are certain characteristics and features by which a distinction is made between developed and developing countries, and these are well-known characteristics. but what the author is trying to present in this article is to show some new or additional characteristics are the reasons for underdevelopment and is not a result of it. That is why the author believes that these additional criteria are what must be taken care of and focused on when trying to bring about development in developing countries, because if it taking place the development is achieved immediately. The world has been running towards recognized standards and indicators to distinguish between developed and developing countries for several decades, However, it is useless. Development is never achieved in developing countries, the situation of the poor around the world is getting worse, and the debts of developing countries are on the increase. With the Corona pandemic, it became clear to all of us that the world needs new indicators and other criteria that must be relied upon when making this distinction between developed and developing countries. The Corona pandemic had the merit of uncovering economic terms that have become sterile and do not present new, and it is time to introduce new and useful in the field of sustainable development in order to improve the conditions of the poor in these countries and providing them with decent livelihoods.

RELATED PAPERS

Carlos Alberto Herrera

Pediatric Research

Richard Grand

Ieda Parra Barbosa Rinaldi

Resources Environment and Information Engineering

Siddique Baig

Matthias Reinert

Honvédségi Szemle

Attila Hadi

International Journal of Basic & Clinical Pharmacology

Middle School Journal

Matthew J Moulton

Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.

Vlasta Mohaček Grošev

Chemosphere

Kevin Yeager

Thaysa Alvim

Ana Luiza R . Braz

Journal of Consciousness Studies

charles heywood

Cholesterol

Zacharoula Karabouta

Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging

Elena Kosheleva

Journal of Physics: Conference Series

Daniel Grolimund

Boletim do Centro de Pesquisa de Processamento de Alimentos

Andréa Teixeira

Stephka Chankova

David McFarlane

JURNAL TADZAKKUR

Hasan Albanna

yyjugf hfgerfd

Diane Morrad

The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology

Ludmila Kasatkina

Archives of Disease in Childhood

Sarah Stewart-brown

See More Documents Like This

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

No Poverty pp 1–11 Cite as

Developing Countries: Modern Perspectives on Ideas for Upliftment

- Subrato Banerjee 8 , 9

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 10 April 2020

212 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Part of the book series: Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals ((ENUNSDG))

Less-developed countries ; Underdeveloped countries

Development , for the purposes of this entry, can be defined as the process of gaining competence and sufficiency in the provision of current and future necessities that improve the quality of life, such as quality education, job opportunities, well-functioning institutions, healthcare and nutrition, and infrastructure beyond basic levels.

Developing country is characterized by some features of a developed nation and some of an underdeveloped nation. Countries like China and India have prominent features of a developed country that include sufficient investment in institutions, education, healthcare, infrastructure, agriculture, and those in the private sector, thereby promoting entrepreneurship. Developing countries however also have many characteristics of underdeveloped countries such as a sizeable proportion of citizens that live below the poverty line. This means that this section of the population cannot...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Acemoglu D, Robinson JA (2012) Why nations fail. Profile Books, London

Google Scholar

Banerjee S (2015) Testing for fairness in regulation: application to the Delhi transportation market. J Dev Stud 51(4):464–483

Article Google Scholar

Banerjee A, Duflo E, Qian N (2012) On the road: access to transportation infrastructure and economic growth in China. NBER working paper no. 17897. https://www.nber.org/papers/w17897

Bigman D (2002) Globalization and the developing countries. CABI Publishing, Wallingford

Camfield L (2012) Quality of life in developing countries. In: Land K, Michalos A, Sirgy M (eds) Handbook of social indicators and quality of life research. Springer, Dordrecht

Duflo E, Kremer M, Robinson J (2011) Nudging farmers to use fertilizer: theory and experimental evidence from Kenya. Am Econ Rev 101(6):2350–2390

Furtado C (1964) Development and underdevelopment. University of California Press, Berkeley

Gollin D, Jedwan R, Vollrath D (2016) Urbanization with and without industrialization. J Econ Growth 21(1):35–70

Gough I, McGregor JA (2007) Wellbeing in developing countries: from theory to research. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book Google Scholar

Hettne B (1983) The development of development theory. Acta Sociol 26(3/4):247–266

Hirschman A (1958) The strategy of economic development. Yale University Press, New Haven

Illich I (1969) Celebration of awareness. Doubleday, New York

Jenks M, Burgess R (2000) Compact cities: sustainable urban forms for developing countries. Spon Press, London

Khalil M (2003) The wireless internet opportunity for developing countries. In: The Wireless Internet Opportunity for Developing Countries (Ed: The Wireless Internet Institute, World Times): 1–4. Retrieved from: http://www.infodev.org/sites/default/files/resource/InfodevDocuments_24.pdf

Kumar A (1999) The black economy in India. Penguin, New Delhi

Lagos-Matus G (1963) International stratification and underdeveloped countries. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill

Lewis WA (1954) Economic development with unlimited supplies of labor. Manch Sch Econ Soc Stud 22:139–191

Maxfield S (1997) Gatekeepers of growth the international political economy of central banking in developing countries. Princeton University Press, Princeton

McCalla AF, Nash J (2007) Reforming agricultural trade for developing countries. The World Bank, Washington, DC

Mincer J (1981) Human capital and economic growth. (Working Paper No. 803). National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA. Retrieved from: https://www.nber.org/papers/w0803

Mullainathan S, Shafir E (2013) Scarcity. Henry-Holt, New York

Nielsen L (2013) How to classify countries based on their level of development. Soc Indic Res 114(3):1087–1107

Nurkse R (1953) Problems of capital formation in underdeveloped countries. Oxford University Press, New York

Patnaik U (2003) Global capitalism, deflation and agrarian crisis in developing countries. Social Policy and Development Programme paper number 15. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development

Portes A (1976) On the sociology of national development: theories and issues. Am J Sociol 82(1):55–85

Ranis G, Fei JCH (1961) A theory of economic development. Am Econ Rev 51(4):533–565

Rao VKRV (1952) Investment, income and the multiplier in an underdeveloped economy. Indian Econ Rev 1(1):55–67. (Reprinted in The economics of underdevelopment. Agarwala AN and Singh SP (eds). Oxford University Press, Bombay, 1958)

Ray D (1998) Development economics. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Ray D (2010) Uneven growth: a framework for research in development economics. J Econ Perspect 24(3):45–60

Romer P (1989) Human capital and growth: Theory and evidence (Working Paper No. 3173). National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA. Retrieved from: https://www.nber.org/papers/w3173.pdf

Rosenstein-Rodan PN (1943) Problems of industrialization of eastern and southeastern Europe. Econ J 53(210/211):202–211

Rostow WW (1960) The stages of economic growth: a non-communist manifesto. Cambridge University Press, New York

Semba RD, Bloem MW (2001) Nutrition and health in developing countries. Humana Press, Totowa

Sen AK (1993) Capability and well-being. In: Sen A, Nussbaum M (eds) The quality of life. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Sen AK (1999) Development as freedom. Alfred A. Knopf, New York

UNDP (2016) Human development index and environmental sustainability. Retrieved from: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-and-environmental-sustainability

UNDP (2018) Statistical update. Human development indices and indicators. Retrieved from: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2018_human_development_statistical_update.pdf ; http://hdr.undp.org/en/2018-update

Weiner M (1966) In: Weiner M (ed) Modernization: the dynamics of growth. Basic Books, New York

World Bank (2006) Doing business 2007: how to reform. World Bank, Washington, DC

World Bank (2009) Reshaping economic geography. World Development Report. Retrieved from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/730971468139804495/pdf/437380REVISED01BLIC1097808213760720.pdf

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Australia India Institute, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Subrato Banerjee

Centre for Behavioural Economics, Society and Technology (BEST), Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Subrato Banerjee .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

European School of Sustainability, Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

Walter Leal Filho

Center for Neuroscience & Cell Biology, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

Anabela Marisa Azul

Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Passo Fundo University Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Passo Fundo, Brazil

Luciana Brandli

HAW Hamburg, Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

Amanda Lange Salvia

Istinye University, Istanbul, Turkey

Pinar Gökcin Özuyar

International Centre for Thriving, University of Chester, Chester, UK

Section Editor information

Dept. of Economics, Faculty of Arts, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

Sarah Ahmed Ph.D

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Banerjee, S. (2020). Developing Countries: Modern Perspectives on Ideas for Upliftment. In: Leal Filho, W., Azul, A., Brandli, L., Lange Salvia, A., Özuyar, P., Wall, T. (eds) No Poverty. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69625-6_13-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69625-6_13-1

Received : 16 December 2018

Accepted : 29 March 2019

Published : 10 April 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-69625-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-69625-6

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Earth and Environm. Science Reference Module Physical and Materials Science Reference Module Earth and Environmental Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

The O’Malley Archives

- O'Malley's political interviews

- Padraig O'Malley

- Social Disintegration in the Black Community - Implications for Transformation by Mamphela Ramphele

- Non-Collaboration with Dignity

- Economic Issues

- World Human Development

- Characteristics of Developing Countries

- A Social Market Economy for South Africa - Prerequisites

- Poverty and Development

- Constitutional Issues

- Accountability in Transition

- Constitutional Rule in a Participatory Democracy

- Democratic Party Discussion Document on Constitutional Proposals

- Constitutional Proposals of the National Party - A Critical Analysis

- The Constitutional Issues

- Human Rights Issues

- The Bill Proposed by the South African Law Commission

- Peace Treaty of Vereeniging, 31 May 1902

- Letter from E. R. Roux to Douglas Wolton, 5 September 1928

- Resolution on 'the South African question', 1928

- 'Our Annual Conference - An Inspiring Gathering', 31 January 1929

- Programme of the Communist Party of South Africa adopted at the seventh annual conference of the Party, 1 January 1929

- Africans' claims in South Africa, 16 December 1943

- The Freedom Charter 26 June 1955

- Letter on the current situation and suggesting a multi-racial convention, from Chief Albert J. Luthuli to Prime Minister J. G. Strijdom, 28 May 1957

- Nelson Mandela's Testimony at the Treason Trial 1956-60

- 'General Strike' - Statement by Nelson Mandela

- "Racial Crisis in South Africa"

- Forced Withdrawal Of South Africa From The Commonwealth

- Document 9: First letter from Nelson Mandela to Hendrik Verwoerd, 20 April 1961

- Document 10: Letter from Nelson Mandela to Sir de Villiers Graaff, leader of the United Party, 23 May 1961

- Document 11: Second letter from Nelson Mandela to Hendrik Verwoerd, 26 June 1961

- Nelson Mandela's First Court Statement - 1962

- No Arms for South Africa

- Operation Mayibuye

- The ANC calls on you - Save the Leaders!

- "I am Prepared to Die"

- Statement At Press Conference In Dar Es Salaam Concerning Sentences In The Rivonia Trial June 12, 1964

- Statement To The Delegation Of The United Nations Special Committee Against Apartheid, London, April 1964

- Document 21. Memorandum on ANC "discord" smuggled out of Robben Island, 1975?

- Declaration Of The Seminar On The Legal Status Of The Apartheid Regime And Other Legal Aspects Of The Struggle Against Apartheid

- Address by State President P. W. Botha, August 15, 1985

- Harare Declaration

- Notes prepared by Nelson Mandela for his meeting with P. W. Botha 5 July 1989

- Resolution by the Conference for a Democratic Future on negotiations and the Constituent Assembly 8 December 1989

- 'A document to create a climate of understanding'; Nelson Mandela to F. W. de Klerk 12 December 1989

- Chronology of Documents and Reports

- 1806. Cape Articles of Capitulation

- 1806. Proclamation The British

- 1809. 'Hottentot Proclamation'

- 1811. Proclamation

- 1812. Apprenticeship of Servants Act

- 1818. Proclamation

- 1819. Proclamation

- 1826. Ordinance No 19

- 1827. Ordinance No 33

- 1828. Criminal Procedure Act No 40

- 1828. Ordinance No 49

- 1828. Ordinance No 50

- 1829. Ordinance No 60

- 1830. Evidence Act No 72

- 1832. [First] Reform Act

- 1833. Abolition of Slavery Act

- 1834. Vagrancy Act

- 1835. Ordinance No 1

- 1836. Municipal Boards Ordinance

- 1836. [Cape of Good Hope] Punishment Act

- 1837. Ordinance No 2

- 1841. Masters & Servants Ordinance No 1

- 1848. Ordinance No 3

- 1850. Squatters Ordinance

- 1853. Cape Constitution

- 1856. Masters & Servants Act No 15

- 1857. Kaffir Pass Act No 23

- 1857. Kaffir Employment Act No 27

- 1865. Natal Exemption Law

- 1865. Natal Native Franchise Act No 28

- 1865. [British] Colonial Laws Validity Acts Nos 28 & 29

- 1866. Orange Free State Occupation Law

- 1867. [Second] Reform Act

- 1867. Vagrancy Act

- 1868. Land Beacons Act

- 1870. 'Cattle Removal' Act

- 1872. Proclamation

- 1872. Proclamation No 14

- 1873. Masters & Servants Amendment Act

- 1874. Ordinance No 2

- 1874. Seven Circles Act

- 1878. Peace Preservation Act

- 1879. Native Locations Act

- 1879. Vagrancy Amendment Act No 23

- 1880. Searching Ordinance No 1

- 1881. Village Management Act

- 1882. Trade in Diamonds Consolidation Act

- 1883. Mining Regulations

- 1883. Liquor Law

- 1883. Public Health Act No 4

- 1884. [Third] Reform Act

- 1885. Asiatic Bazaar Law [?]

- 1887. Cape Parliamentary Registration Act

- 1891. Orange Free State Statute Book Act

- 1891. Natal Native Code

- 1892. Cape Franchise & Ballot Act

- 1893. Mining Law

- 1894. Glen Grey Act

- 1896. Mining Code

- 1896. Mining Regulations

- 1896. Natal Franchise Act

- 1897. Mining Law No 11

- 1897. Public Health Amendment Act No 23

- 1898. Mining Law No 12

- 1899. Native Labour Locations Act No 30

- 1900. Indemnity & Special Tribunals Act No 6

- 1900. Natal Courts Special Act No 14

- 1902. Native Reserve Locations Act No 40

- 1903. Mines, Works & Machinery Ordinance

- 1903. Precious Stones Ordinance

- 1903. Bloemfontein Municipal Ordinance

- 1903. Transvaal Municipalities Election Ordinance

- 1904. Transvaal Labour Ordinance

- 1904. Natal Native Locations Act

- 1904. Transvaal Labour Importation Ordinance

- 1905. Cape School Boards Act

- 1906. Mining Regulations

- 1906. Coloured Labourers Health Regulations

- 1906. Immigration Act

- 1906. Transvaal Asiatic Law Amendment Act

- 1908. Natal Special Courts Act No 8

- 1908. Gold Law & Townships Act

- 1908. Railway Regulation Act

- 1909.? Act No 29

- 1909. Industrial Disputes Prevention Act

- 1909. Transvaal Industrial Disputes Prevention Act

- 1909. Transvaal Companies Act

- 1909. [Union of] South Africa Act

- 1911. Mines & Works Act No 12

- 1911. Immigrants Restriction Act

- 1911. Native Labour Regulation Act

- 1911. Official Secrets Act

- 1912. Defence Act

- 1912. Mines & Works Regulations Act

- 1912. Riotous Assemblies Act

- 1913. Immigration Act

- 1913. Admission of Persons to the Union Regulation Act No 22

- 1913. Natives Land Act No 27

- 1914. Indian Relief Act

- 1914. Riotous Assemblies & Criminal Law Amendment Act No 27

- 1915. Indemnity & Special Tribunals Act No 11

- 1917. Criminal Procedure & Evidence Act No 31

- 1918. Status Quo Act

- 1918. Regulation of Wages, Apprenices & Improves Act.

- 1920. Housing Act

- 1920. Native Affairs Act No 23

- 1921. Education Proclamation No 55

- 1921. Juvenile Act

- 1922. Apprenticeship Act

- 1922. Strike Condonation Act

- 1923. Native Urban Areas Act No 21

- 1924. Industrial Conciliation Act No 11

- 1925. Wage Act

- 1925. Customs Tariff Act

- 1926. Education Proclamation No 16

- 1926. Mines & Works Amendment Act No 25

- 1926. Masters & Servants Amendment Act

- 1926. Job Reservation Act

- 1927. Immorality Act No 5

- 1927. Asiatics in the Northern Districts or Natal Act No 33

- 1927. Native Administration Act No 38

- 1927. Union Nationality & Flag Act

- 1928.? Act No 13

- 1929. Native Administration Amendment Act

- 1929. Colonial Development Act

- 1930. Riotous Assemblies Amendment Act No 19

- 1930. Native Urban Areas Amendment Act

- 1931. Entertainments Censorship Act No 28

- 1932. Soil Erosion Act

- 1932. Natal Native [Amendment?] Code

- 1932. Transvaal Asiatic Land Tenure Act No 35

- 1932. Native Service Contract Act

- 1934. Status of the Union Act

- 1934. Status & Seal Act 1

- 1934. Slums Act

- 1936. Representation of Natives Act No 12

- 1936. Native Trust & Land Act No 18

- 1936. Act No 22

- 1937. Aliens Act

- 1937. Native Urban Areas Amendment Act

- 1937. Natives Laws Amendment Act

- 1937. Industrial Conciliation [Amendment] Act No 36

- 1937. Wage Act

- 1937. Immigration Amendment Act

- 1937. Marketing Act

- 1939. Asiatics Land & Trading Act

- 1940. War Measures Act No 13

- 1941. War Measure No 6

- 1941. War Measure No 28

- 1941. Factories, Machinery & Building Works Act

- 1941. Workmen's Compensation Act

- 1942. War Measure No 9

- 1942. War Measure No 13

- 1942. War Measure No 145

- 1942. National Education & Finance Act

- 1943. Trading of Occupation & Land (Transvaal & Natal) Act

- 1943. Pegging Act

- 1944. Apprenticeship Act No 37

- 1944. Native Urban Areas Amendment Act

- 1944. Nursing Act

- 1945. War Measure No 1425

- 1945. Housing Emergency Powers Act

- 1945. Native Urban Areas Consolidation Act No 25

- 1945. Natives Laws Amendment Act

- 1946. Indian Representation Act

- 1946. Asiatic Land Tenure & [Indian] Representation Act No 28

- 1946. Electoral Consolidation Act No 31

- 1946. Ghetto Act

- 1947. Commissions Act No 8

- 1947. Natural Resources Development Act No 51

- From 7 June 1985 New York Times, Nicholas Kristof, "Pretoria Curb: Business View"

- From 2 August 1985: Financial Times, Jim Jones et al., "Rand Steadies as Pretoria Faces Increasing Unrest"

- From 2 August 1985, London Times, "Big House majority for sanctions, but Helms holds up the Senate"

- From 9 August 1985, Financial Times, Alexander Nicoll, "Short-term debt Pretoria's Achilles heel"

- From 2 April 1986, Financial Times, Anthony Robinson, "Trade Sanctions & Disinvestment Intensified"

- From 19 March 1989, Journal of Commerce, Tony Koenderman, "South Africa: One of Few Repaying Debt"

- From 14 February 1990, The Independent, "Outlook: Sanctions Lesson from the Banks"

- From 24 September 1993, Journal of Commerce, Lucy Komisar, "S. African Sanctions: A Success"

- 1948. Asiatic Law Amendment Act No 47

- 1949. Unemployment Insurance Amendment Act

- 1949. Railway & Harbours Amendment Act

- 1949. Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act No 55

- 1949. Natives Laws Amendment Act

- 1949. South West Africa Affairs Amendment Act

- 1949. South African Citizenship Act

- 1950. Immorality Amendment Act No 21

- 1950. Population Registration Act No 30

- 1950. Group Areas Act No 41

- 1950. Suppression of Communism Act No 44

- 1950 - Stock Limitation Act

- 1951- Native Building Workers Act No 27

- 1951 - Separate Representation of Voters Act No 46

- 1951. Bantu Authorities Act No 68

- 1951. Suppression of Communism Amendment Act

- 1951. Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act

- 1952. Native Services Levy Act

- 1952. Native Urban Areas Amendment Act

- 1952. Criminal Sentences Amendment Act No 33

- 1952. High Court of Parliament Act No 35

- 1952. Electoral Laws Amendment Act

- 1952. Natives Laws Amendment Act No 54

- 1952. Natives Abolition of Passes & Coordination of Doc's Act No 67

- 1953. Public Safety Act No 3

- 1953. Criminal Law Amendment Act No 8

- 1953. Native Labour Settlement of Disputes Act No 48

- 1953. Reservation of Separate Amenities Act No 49

- 1953. Immigrants Regulation Amendment Act

- 1953. Bantu Education Act

- 1954. Natives Resettlement Act

- 1954. Riotous Assemblies & Criminal Laws Amendment Act No 15

- 1954. Native Urban Areas Consolidation Act

- 1955. Appellate Division Quorum Act No 25 or 27.

- 1955. Criminal Procedure & Evidence Amendment Act No 29

- 1955. Departure from the Union Regulation Act No 34

- 1955. Motor Carrier Transportation Amendment Act No 44

- 1955. Senate Act No 53

- 1955. Customs Act No 55

- 1955. Criminal Procedure Act No 56

- 1955. Group Areas Development Act

- 1955. Native Urban Areas Amendment Act

- 1956. South Africa Amendment Act No 9

- 1956. Separate Representation of Voters Amendment Act

- 1956. Official Secrets Act No 16

- 1956. Riotous Assemblies [Amendment?] Act No 17

- 1956. Mines & Works Amendment Act No 27

- 1956. Industrial Conciliation Amendment Act No 28

- 1956. Bantu Education Amendment Act

- 1956. Native Urban Areas Amendment Act

- 1956. Native Administration Amendment Act No 42

- 1956. General Laws Amendment Act No 50

- 1956. Bantu Prohibition of Interdicts Act No 64

- 1956. ? Amendment Act

- 1957. Immorality Act No 23

- 1957. Defence Act No 44

- 1957. State-Aided Institutions Act

- 1957. Flag Amendment Act

- 1957. Nursing Amendment Act

- 1957. Native Urban Areas Amendment Act No 77

- 1957. Proclamation No 333

- 1958. Criminal Procedure Amendment Act No 9

- 1958. Special Criminal Courts Amendment Act

- 1959. Trespass Act No 6

- 1959. Prisons Act No 8

- 1959. Industrial Conciliation Amendment Act

- 1959. Bantu Investment Corporation Act

- 1959. Native Labour Settlement of Disputes Amendment Act

- 1959. Extension of University Education Act No 45

- 1959. Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act No 46

- 1959. Supreme Court Act No 59

- 1960. Reservation of Separate Amenities Amendment Act No 10

- 1960. Unlawful Organizations Act No 24 or 34

- 1960. Emergency Regulations in Transkei Nos R.400 & R.413

- 1961. Republic of South Africa Constitution Act No 32

- 1961. General Laws Amendment Act

- 1961. Urban Bantu Councils Act No 79

- 1962. ? Act

- 1962. Sabotage Act General Laws Amendment Act No 76

- 1963. Publications & Entertainments Act No 26

- 1963. General Laws Amendment Act No 37

- 1963. Transkei Constitution Act No 48

- 1963. Censorship Act

- 1964. Bantu Urban Areas Amendment Act

- 1964. Coloured Persons Representative Council Act No 49

- 1964. Bantu Labour Act No 67

- 1964. General Laws Amendment Act No 80

- 1965. Bantu Laws Amendment Act

- 1965. Bantu Labour Regulations Act

- 1965. Bantu Homelands Development Corporations Act

- 1965. Criminal Procedure Amendment Act No 96

- 1966. Community Development Act

- 1966. Group Areas [Amendment?] Act No 36

- 1966. General Laws Amendment Act No 62

- 1967. Prohibition of Improper Political Inference Act

- 1967. Defence Amendment Act

- 1967. Suppression of Communism Amendment Act No 24

- 1967. Terrorism Act

- 1967. Physical Planning & Utilization of Resources Act No 88

- 1968. Criminal Procedure Amendment Act No 9

- 1968. Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Amendment Act No 21

- 1968. South Africa Indian Council Act No 31

- 1968. Separate Representation of Voters Amendment Act No 50

- 1968. Prohibition of Political Interference Act No 51

- 1968. Coloured Persons Representative Council Amendment Act No 52

- 1968. Affected Organizations Act

- 1968. Promotion of Economic Development of the Homelands Act

- 1969. South Africa Amendment Act

- 1969. Legal Aid Act No 22

- 1969. Abolition of Juries Act No 34

- 1969. South West Africa Affairs Amendment Act

- 1969. Public Service Amendment Act

- 1969. Electoral Laws Amendment Act No 99

- 1969. General Laws Amendment Act No 101

- 1970. Bantu Homelands Citizen Act No 26

- 1970. General Laws Further Amendment Act No 92

- 1971. Bantu Urban Areas Amendment Act

- 1971. Bantu Homelands Constitution Act No 21

- 1973. Venda Constitution Act

- 1973. Gazankulu Constitution Act

- 1973. Aliens Control Act No 40

- 1973. ? Act

- 1973. Gatherings & Demonstrations Act No 52

- 1973. Bantu Labour Relations Regulations Amendment Act No 70

- 1973. Proclamation on the Group Areas Act No 228

- 1974. Riotous Assemblies Amendment Act No 30

- 1974. Affected Organizations Act No 31

- 1974. Publications Act No 42

- 1974. Bantu Laws Amendment Act No 70

- 1974. Defence Further Amendment Act No 83

- 1974. [Second] General Laws Amendment Act No 94

- 1974. Qwaqwa Constitution Act

- 1975. KwaZulu Constitution Act

- 1975. Coloured Persons Representative Council Amendment Act No 32

- 1976. Republic of Transkei Constitution Act No 15

- 1976. Parliamentary Internal Security Commission Act No 67

- 1976. Internal Security Amendment Act No 79

- 1976. Status of Bophuthatswana Act No 89

- 1976. Status of the Transkei Act No 100

- 1977. Transkei Public Security Act No 30

- 1977. Criminal Procedure Act No 51

- 1977. Community Councils Act

- 1978. Black Urban Areas Consolidation Amendment Act

- 1979. Status of Venda Act

- 1979. Industrial Conciliation Amendment Act No 94

- 1979. Status of the Ciskei Act

- 1981. Labour Relations Amendment Act No 57

- 1982. Internal Security Act No 74

- 1982. Registration of Newspapers Amendment Act

- 1982. Black Local Authorities Act

- 1983. Republic of South Africa Constitution Act No 110

- 1984. Black Communities Development Act Davenport

- 1985. Regional Services Council Act

- 1986. ? Act(s)

- 1986. Constitutional Affairs Amendment Act No 104

- 1986. Abolition of Influx Control Act No 68

- 1986. Restoration of South African Citizenship Act No 73

- 1987. ? Act

- 1987. Act/Regulations

- 1988. Free Settlement Areas Act

- 1988. Prevention of Illegal Squatting Amendment Act

- 1989. ? Act

- 1990. ? Act(s)

- Collapse of BLA's and introduction of Auxillary Forces

- Policing Approach

- The South African Police: Managers of conflict or party to the conflict

- State Security Council and related structures

- The Policing of Public Gatherings and Demonstrations in South Africa 1960-1994

- Third Force Proposals

- Torture and Death in Custody

- The 70's riot control - Jimmy Kruger

- The use of Torture in Detention (refers to Rooi Rus Swanepoel)

- From Pariah to Partner - Bophuthatswana, the NPKF, and the SANDF

- Organisational Structure of SA State

- Tricameral Parliament Description 1

- Tricameral Parliament Description 2

- Tricameral Constitution 1983

- Where Thought Remained Unprisoned

- Clear the Obstacles and Confront the Enemy

- Whither the Black Consciousness Movement?

- We Shall Overcome!

- Indian South Africans - A Future Bound with the Cause of the African Majority

- The Anatomy of the Problems of the National Liberation Struggle in South Africa

- Through the Eyes of the Workers

- Towards Freedom

- Let us Work Together for Unity

- SWAPO Leads Namibia

- About the editor

- List of Abbreviations

- A History of the IWW in South Africa

- Loyalists and Rebels

- Resistance and Reaction

- "Fight for Africa, which you deserve": The Industrial Workers of Africa in South Africa, 1917-1921

- Transition (1990 - 1994)

- Post-Transition (1994 - 1999)

- Transformation (1999-)

- General Information

- Mac Maharaj

About this site

This resource is hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation , but was compiled and authored by Padraig O’Malley. It is the product of almost two decades of research and includes analyses, chronologies, historical documents, and interviews from the apartheid and post-apartheid eras.

This resource is hosted by the Nelson Mandela Foundation , but was compiled and authored by Padraig O’Malley. Return to theThis resource is hosted by the site.

Characteristics of Developing Economies

Even though developing nations have very different backgrounds in terms of resources, history, demography, religion and politics, they still share a few common characteristics. Today, we will go over six common characteristics of developing economies.

Common Characteristics of Developing Economies

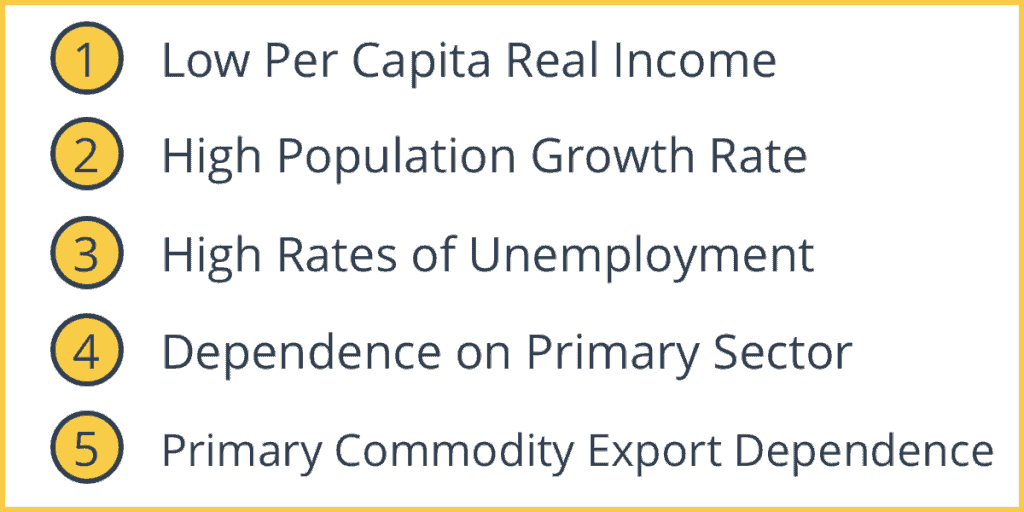

1. Low Per Capita Real Income

Low per capita real income is one of the most defining characteristics of developing economies. They suffer from low per capita real income level, which results in low savings and low investments.

It means the average person doesn’t earn enough money to invest or save money. They spend whatever they make. Thus, it creates a cycle of poverty that most of the population struggles to escape. The percentage of people in absolute poverty (the minimum income level) is high in developing countries.

2. High Population Growth Rate

Another common characteristic of developing countries is that they either have high population growth rates or large populations. Often, this is because of a lack of family planning options and the belief that more children could result in a higher labor force for the family to earn income. This increase in recent decades could be because of higher birth rates and reduced death rates through improved health care.

3. High Rates of Unemployment

In rural areas, unemployment suffers from large seasonal variations. However, unemployment is a more complex problem requiring policies beyond traditional fixes.

4. Dependence on Primary Sector

Almost 75% of the population of low-income countries is rurally based. As income levels rise, the structure of demand changes, which leads to a rise in the manufacturing sector and then the services sector.

5. Dependence on Exports of Primary Commodities

Since a significant portion of output originates from the primary sector, a large portion of exports is also from the primary sector. For example, copper accounts for two-thirds of Zambia’s exports.

Similar Posts:

- Cyclical Unemployment

- Frictional Unemployment

- Structural Unemployment

- Economies of Scale

- The Demographic Transition Model

2 thoughts on “Characteristics of Developing Economies”

Thank you intelligenteconomist.com i love you all! This helped me pass my test and I THINK I want to live again. ps. very sad whats happening in the world.. ;(

To what extent would it be argued that all developing countries share same set of characteristics

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name and email in this browser for the next time I comment.

Provide details on what you need help with along with a budget and time limit. Questions are posted anonymously and can be made 100% private.

Studypool matches you to the best tutor to help you with your question. Our tutors are highly qualified and vetted.

Your matched tutor provides personalized help according to your question details. Payment is made only after you have completed your 1-on-1 session and are satisfied with your session.

- Homework Q&A

- Become a Tutor

All Subjects

Mathematics

Programming

Health & Medical

Engineering

Computer Science

Foreign Languages

Access over 20 million homework & study documents

Characteristics of developing countries essay.

Sign up to view the full document!

24/7 Homework Help

Stuck on a homework question? Our verified tutors can answer all questions, from basic math to advanced rocket science !

Similar Documents

working on a homework question?

Studypool is powered by Microtutoring TM

Copyright © 2024. Studypool Inc.

Studypool is not sponsored or endorsed by any college or university.

Ongoing Conversations

Access over 20 million homework documents through the notebank

Get on-demand Q&A homework help from verified tutors

Read 1000s of rich book guides covering popular titles

Sign up with Google

Sign up with Facebook

Already have an account? Login

Login with Google

Login with Facebook

Don't have an account? Sign Up

- All Categories

Characteristics of Developing Countries

The theme of this essay is: the importance of a study of other semi-developed countries as they struggle for economic growth, the elimination of mass poverty and, at the political level, for democratisation and the reduction of reliance on coercion. New countries are finding their voices in all sorts of ways and are managing to interest an international audience.

South Africa is not least among them; contemporary international consciousness of the travail of our particular path towards modernity testifies at least to a considerable national talent for dramatic communication and (for those who care to look more deeply) a far from extinct tradition of moral conscientiousness. One aspect of this flowering is a rapidly growing crop of social scientific studies of semi-developed countries of which this university is fortunate to have a substantial collection, contained mainly in the library of Jan Smuts House.

From this literature, one can extract five themes of particular interest. The first is the problem of uneven development and effective national unification, especially in deeply divided societies. Capitalist development has impinged on semi-developed countries from outside rather than transforming slowly from within, incorporating different groups in different ways. Particular problems arise when differential incorporation coincides in substantial measure with boundaries between ethnic groups.

If Donald Horowitz’s remarkable study of ethnic groups in conflict is right, more energy goes into attempting to maximise differences in the welfare of in groups and out groups than into maximising their joint welfare, with adverse consequences for the possibilities of building the national political and economic institutions required for development. Gordon Tullock has argued that this is an additional reason for preferring market-based rather than state-led economic growth in deeply divided societies. In itself it is, but the secondary effects of different paths on distribution have to be taken into account.

In so far as they lead to worsening differentials between groups, the possibility of heightened conflict is created. The only long-term hope is to make ethnic boundaries less salient; the happiest outcome would seem to be when ethnicity becomes decorative in a high income economic environment. This is likely to be the work of decades, perhaps of centuries; even so, appalling retrogressions always seem to remain possible. The consequence of deep divisions is that there is likely to exist an unusually large number of prisoner’s dilemma situations. The prisoner’s dilemma arises when partners in crime are apprehended and held separately. The prisoners will be jointly better off if they do not inform on each other, but each prisoner will be better off if he informs on the other, while the other does not inform on him. Attempts at individual maximisation may lead to both prisoners informing on each other which leads to the worst joint outcome. The dilemma arises because of the absence of the opportunity for co-operation. ) Under such conditions, negotiation skills are at a premium.

There are also advantages in the acceptance of a deontological liberal philosophy which (in the shorthand of political philosophers) places the right over the good. This involves seeking to regulate social relations by just procedures while leaving individuals as free as possible to pursue their own, diverse conceptions of the good life. Such an enterprise has a better chance of success if its conception of justice implies that attention should be paid simultaneously to the reduction of poverty. The analytical Marxist, Adam Przeworski has analysed analogous problems which arise in the case of severe class conflict.

In his view, social democratic compromises are held together by virtue of the propensity of capitalists to reinvest part of their profits with the effect of increasing worker incomes in the future. Class compromise is made possible by two simultaneous expectations: workers expect that their incomes will rise over time, while capitalists expect to be able to devote some of their profits to consumption. In conditions of severe class conflict, these expectations about the future become uncertain, time horizons shorten, workers become militant, capitalists disinvest and political instability results.

Three forms of resolution are available: stabilising external intervention, negotiation or renegotiation of a social contract or the strengthening of the position of one or other class by a shift towards conservatism or revolution. Przeworski’s sternest warnings are to Marxists who assume that revolution and the introduction of socialism is the inevitable outcome of a crisis. The second theme in the literature on semi-developed countries has to do with their position within the world economy. Three related sub-themes can be identified.

Firstly, there has been a debate about the forms and limits of the diffusion of industrialisation. Dependency theory – now somewhat out of fashion, since its predictions of severe limitations on industrialisation in developing countries have been falsified – asserted that relationships between developing and developed countries are such as to keep the latter in perpetual economic subordination. The contrary thesis – that advanced industrial countries have had to deal with increased competition arising from quite widespread diffusion – now seems more plausible.

Lester Thurow, for instance, has argued that the increase in inequality in the United States since the late 1970s is not to be attributed either to the Reagan administration’s tax welfare policies nor to demographic change, but to intense international competitive pressures coupled with high unemployment. Secondly, some theorists have asserted that a process of the “globalisation of capital” unprecedented opportunities for international movement of short-term and long-term capital – has removed the possibilities of national reformism (i. e. lass compromise reached at the level of the nation state) and is ushering in a period of global class conflict. If there is any truth in this hypothesis at all, it would have to be qualified both by a careful study of precisely how the capital (and trade) flows of the 1980s differed from those of earlier periods and the sorts of changes in national policy choices capable of delivering a broadly-based rise in living standards which follow from these differences. Even if some options may have disappeared, it does not follow that new ones are not available.

Finally, there has been a preoccupation with the problems of structural adjustment (in both developed and developing economies) necessitated by a changing international environment. Structural adjustment is a subject for both economic and political analysis. At the economic level the issues of maintaining macroeconomic balance, changing industrial and manpower policy and protecting the poor against a period of deflation which is – or seems to be – necessary in many cases, all have to be considered. Political problems arise when it comes to the distribution of the burdens of adjustment and the creation of new capacities for development.

Lack of ability to handle structural adjustment problems can lead to a variety of outcomes, from the shifting of a large part of the burden of change to future generations (as both the United States and Brazil have done in recent years), to loss of control at the macroeconomic level leading to rapid drops in living standards, hyperinflation and/or defaults on international obligations, political instability and even regime change. Identification and study of the capacities available to avoid undesirable outcomes are of considerable interest.

The third theme in the semi-developed country literature is that of the relationship between economic inequality and political conflict. Characteristically, semi-developed countries have more unequal distributions of income between households than developed countries. It used to be thought that inequality peaked at the intermediate stage of development, partly because of limitations of the spread of education (and therefore of human capital) and partly because low-paying sectors continued to account for a substantial proportion of employment.

Recent evidence has thrown doubt on the view that inequality necessarily increases during the early stages of development; it is much clearer that it tends to decrease during the later stages. The relationship between economic inequality and political conflict is also complex: studies of cross-national correlations between indicators of the two phenomena have led to unclear, even contradictory results. One reasonably robust result is that revolutions at a relatively early stage of development have much to do with inequality in land holdings. But coherent fmdings in semi-developed countries are virtually non-existent.

Part of the reason for this is mindless number-crunching with insufficient attention paid to the theoretical tradition dealing with conflict and revolution. There is probably quite a lot to be said, for instance, for the Hobbesian view that the proximate cause of violent conflict is itself political in the form of the weakening of the power of the state. Economic factors may also matter, but among these, income distribution may be relatively unimportant and improvements may play as significant a role as deterioration. Rational actor models of regime change have recently appeared in the political science literature.

John Roemer, for instance, conceives of revolution as a two person game between the present ruler (whom he calls the Tsar) and a revolutionary entrepreneur, whose name is Lenin. In his attempt to ovethrow the Tsar, Lenin can propose redistribution of the fixed pie of income. The Tsar can announce a list of penalties which define what each agent who chooses to join Lenin will forfeit, should the revolution fail. Each possible coalition of the population has a probability of succeeding in making the revolution, depending on its size and composition.

Lenin chooses the income redistribution which maximises the probability of overthrowing the Tsar and the Tsar in turn chooses the list of penalties which minimises this maximum value. The solution to this minimax game defines the instability of the regime, i. e. the probability tht it will be overthrown. From game theoretical results, Roemer is able to draw conclusions about the strategies of the players according with experience. For instance, the Tsar will treat the poor harshly and let off the rich lightly if the conditional probabilities of revolution by coalitions are the least bit sensitive to the penalties announced.

Lenin, on the other hand, will only propose a progressive redistribution of income as his optimal strategy under some circumstances. Highly probable revolutions are highly polarised revolutions. Lurking in this literature is also the issue of whether a coherent distinction can be made between revolutions and other forms of regime change, but exploration of that issue would require a lecture of its own. The fourth theme in the semi-developed country literature concerns the bearers of the capacities for economic development. In no society are these likely to be located wholly within the state or within the private sector.

Instead, rather complicated networks able to mount major initiatives may straddle both the public and private sectors. In some semi-developed countries described as “bureaucratic authoritarian”, it may even be the case that some parts of the state continue to act with leading components of the private sector to manage economic development, while other parts of the state induce periodic crises by losing macro-economic control. Two debates in political science are relevant here. The first concerns the nature and functions of civil society.

In its classical use by Adam Smith and Hegel, civil society refers to a social system sufficiently productively advanced and regulated by morality and law to be able to support both the division of labour and the institution of private property. Hegel throws in the police and the civil service as regulators of last resort for good measure. The term “civil society” has been taken up in recent South African debate, sometimes in a rather quaint fashion – one contributor to a recent seminar defined it as consisting of the trade unions, civics, the SA Council of Churches and the Kagiso Trust!

Marxists have criticised liberals for representing the interests of a part as the good of the whole; liberals, it seems, are not the only people capable of making that mistake. A more interesting redefinition of the term has been proposed by Michael Lipton who reserves for it institutions forming neither part of the state nor part of the market, but whose influence may make both state and market function more efficiently. The original definitions are probably the most useful; in terms of them, the strengthening of civil society is indeed a prerequisite for development.

It amounts to developing new specialisations, to building institutions with new capacities and to creating the attitudes and legal framework necessary to support these endeavours. Much of the time, these changes will evolve from existing resources and capacities. But there are also periods of rapid and discontinuous change in which the positions of major groups within societies are fundamentally changed. This amounts to a social and economic revolution, which may or may not be accompanied by a political revolution.

At the analytical level, the classical Marxist conflation of the social, economic and political processes is a serious distortion. At the political level, versions of the Marxist formulation have been used to represent the most grinding political oppression as inaugurating social and economic emancipation. The second political debate is about corporatism. This refers to a situation in which powerful organised interests play a major role in political life as opposed to individuals organised into political parties in a liberal democratic system.

Indeed, to the liberal ear, the term “corporatism” has an authoritarian sound about it. Powerful organised interests, of course, exist in liberal democracies but these function as interest groups with no formal political status. Corporatism emerges when political institutions are shaped to include them. An important distinction needs to be drawn between democratic corporatism where these arrangements are subject to choices made by the electorate in regular elections and authoritarian corporatism where they are not.

Fascist Italy and some Latin American countries provide examples of the latter and the European democracies examples of the former. The mildest form of corporatism is probably tripartite institutions comprised of trade unions, employer organisations and state departments. These participate in the determination of macroeconomic and/or labour market policy in advanced industrial countries, the whole process being described as that of a “social contract”.

Democratic corporatism is subject to changes depending on changes of opinion within the electorate; particular forms put together by left of centre governments are often modified or dissolved by succeeding conservative governments. Authoritarian corporatism, on the other hand, produces an oligarchical system based on deals between elites which sometimes deliver stability and economic growth, quite possibly for long periods of time, but which are not subject to popular approval. Indeed, they are characteristically accompanied by a substantial degree of repression.

In this way they contain divergences of interest which would rip liberal democracies apart. Even in democracies, corporatist arrangements display a degree of inertia; it appears from the recent literature that the welfare state has been more resistant to conservative dismantling in European countries in which corporatist arrangements have been well developed. They also deliver control; it has also been suggested that corporatist structures (as well as a highly competitive configuration) in the labour market result in lower real wages than collective bargaining between employers and industry-wide trade unions.

Democratic systems in which linguistic, religious and ethnic identities perform the function of corporations are referred to as consociational and have some of the same authoritarian logic as corporatist systems. The final theme of interest in the literature on semi-developed countries is that of the transition from authoritarian to democratic rule, the subject of a major scholarly enterprise directed from the Woodrow Wilson International Centre at Princeton University about a decade ago.

Alfred Stepan pointed out that there are a number of distinctive paths leading to democratiastion: in some, warfare and conquest play an integral part, as in Europe after the Second World War. Here, three sub-cases can be distinguished: internal restoration of democracy after external conquest, redemocratisation after a conqueror has been defeated by external force, and externally monitored installation of democracy. In others, the termination of authoritarian regimes is initiated by the wielders of authoritarian power themselves.

In yet others, oppositional forces play a major role in terminating authoritarian rule via diffuse protests by grass-roots organisations, general strikes and general withdrawal of support for the government, by the formation of a grand oppositional pact, possibly with consociational features, by organised violent revolt co-ordinated by democratic reformist parties or by Marxist-led revolutionary war (though the latter has usually led to the installation of an authoritarian successor regime).

These are all ideal types with rather different dynamics; any actual process is likely to contain elements of more than oue ideal type. In a companion piece, John Sheahan observes that economic policy in support of democratisation must meet two conflicting requirements. On the one hand, economic growth requires the ability to limit claims which would seriously damage efficiency or outrun productive capacity. On the other, policy must deliver sufficient fulfilment of the expectations of politically aware groups to gain and hold their acceptance.

Both external economic circumstances and internal political conflicts are capable of rendering impossible the striking of a viable balance between these requirements, with the result that the process of democratisation aborts. The position is complicated in countries which have a long history of import substitution resulting in high levels of protection but which now need to re-orient themselves in order to promote exports. In such cases, the timing of structural adjustment and increases in domestic demand pose tricky problems of economic management.

The overall objective must be to permit the most rapid and broadly based rise in domestic demand while maintaining external balance, subject to the constraints arising from the structure of the domestic labour market. Part of successful management must involve the greatest possible exploitation of new willingness to co-operate induced by the democratisation process itself. Adroit proposals are needed which reduce initially high risks and increase incentives to support economic growth among the principal parties at each stage in the process. Some reconceptualisation of interests is essential.

Intelligent international support allowing constraints to be relaxed at crucial junctures is also of considerable importance. It is sometimes supposed that the transformation of an authoritarian regime into a democracy is a fragile process, for the success of which a range of necessary conditions has to be present. In particular, it is argued both that a democracy has small chance of survival if it does not deliver social and economic improvements for the population at large and that democracies are unable to administer the economic medicine required by crisis conditions.

A recent study of Latin American countries since 1982, however, finds that democracies not only handled economic crises as effectively as authoritarian regimes; they also achieved a far better record of avoiding acute crises in the first place. The puzzle turns out not to be the fragility of democracy, but its vitality. The suggestion is that both the behaviour of political elites and their followers has been misdescribed. On the one hand, democratic governments that displace highly repressive or widely discredited authoritarian regimes may count on a special reserve of political support and trust to carry them through economic crises.

On the other, elected officials may understand the self-defeating nature of enhancing their legitimacy by delivering material payoffs to the bulk of the population, even at the cost of financial disaster. So far, this lecture has not been about South Africa, but has been concerned to identify intellectual resources which might be used when thinking about South African problems. Time permits only a sketchy application of some ideas to our present circumstances. Let me start from the economic side.

One of the more encouraging features of our economic evolution in the last few years is that, although real per capita incomes have declined, the evidence suggests that the distribution of income has improved to such an extent that the proportion of households in poverty did not increase in the years between 1985 and 1990 and probably declined slightly despite a drop in real per capita incomes. The burden of the decline has been borne by the relatively well-to-do if not by the very rich. This trend is unlikely to be sustained in the face of further economic decline.

On the contrary, the prospects for the poor will be served by rapid economic growth; far from there being a conflict between growth and equality in South Africa, the two processes will reinforce each other, especially given appropriate policies. In the light of the importance of a widespread improvement in standards of living to the sustenance of the process of democratisation, it is in the interests of all parties who desire a negotiated settlement to support developments which increase growth. But where is this growth to come from?

All the contemporary evidence suggests that the balance of payments is critical. It is possible to argue in theoretical terms that there ought to be no such thing as a balance of payments constraint. But there is no policy purchase to be had from a static comparison between our present situation and a superior one. A path from the one state to the other has to be specified. There are two difficulties in doing so. Firstly, the path to a better state depends on what other countries are doing. Prisoner’s dilemmas certainly exist at the level of international trade as the very existence of the GATT system testifies.

Secondly, since the process has to be supported politically, the distribution of the costs of adjustment borne by domestic actors has to be taken into account. Either the costs have to be imposed unilaterally by the exercise of political power or compensation has to be negotiated, assuming sufficient gains from liberalisation have been captured domestically. Studies of interest group battles over the determination of the various aspects of balance of payments policy is certainly a topic in political economy.

Another major determinant of macroeconomic policy in recent years is the desire of the state not to make itself vulnerable to international sources of political pressure through loss of control over external balances. This would have meant risking the loss of control over the timing and extent of concessions. Monetary policy, for instance, has been mainly discussed in terms of domestic variables, notably the rate of inflation. But avoidance of adverse developments on the short-term capital account must always have been a major consideration.

Here, analysis of domestic interest groups does not help at all; it will take favourable developments on international markets or purposeful risk reduction to permit a more expansionary policy. The second issue involves efficiency gains from improved taxation and expenditure policy. So far, a discussion of the economic role of the state has largely consisted of old-fashioned arguments over size and ownership, which have been driven by (often imaginary) conceptions of political interest.

But a determined effort to raise popular living standards will require quite a different approach. Its principal component will be a restructuring of government expenditure, particularly that relating to social services, urban infrastructure and rural development in order to create new opportunities for formerly discriminated against or excluded groups. As Professor McGrath has observed, there are more gains to be had from restructuring the expenditure side of government economic activity than from changes on the revenue side.

There are both normative and positive approaches to this question. The positive approach would observe that the restructuring of state expenditure is already under way and would seek to relate it to two developments, significant from the point of view of public choice theory: first, the lowering of the income of the median voter associated with the introduction of the tricameral parliament and secondly, the rise in power of the extraparliamentary movement.

The latter has led to a growing expectation of its political incorporation via the universal franchise leading to an anticipatory set of adjustments. A normative approach could be based on an investigation of what is required to minimise an appropriate measure of poverty. At the political level, an advance in the positive account of what our political system is becoming is most urgently needed. Accounts of competing normative positions and the similarities and differences between them abound.

So do narrative accounts of particular political episodes. But a deeper analysis of fundamental concepts – power in its various aspects, the nature and dynamics of transition, the incentives facing various actors and their strategic choices, the real scope and prospects for legality and, above all, whether steering capacities are being lost or gained by the political system – virtually all remain to be carried out in a convincing fashion.