Freedom Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on freedom.

Freedom is something that everybody has heard of but if you ask for its meaning then everyone will give you different meaning. This is so because everyone has a different opinion about freedom. For some freedom means the freedom of going anywhere they like, for some it means to speak up form themselves, and for some, it is liberty of doing anything they like.

Meaning of Freedom

The real meaning of freedom according to books is. Freedom refers to a state of independence where you can do what you like without any restriction by anyone. Moreover, freedom can be called a state of mind where you have the right and freedom of doing what you can think off. Also, you can feel freedom from within.

The Indian Freedom

Indian is a country which was earlier ruled by Britisher and to get rid of these rulers India fight back and earn their freedom. But during this long fight, many people lost their lives and because of the sacrifice of those people and every citizen of the country, India is a free country and the world largest democracy in the world.

Moreover, after independence India become one of those countries who give his citizen some freedom right without and restrictions.

The Indian Freedom Right

India drafted a constitution during the days of struggle with the Britishers and after independence it became applicable. In this constitution, the Indian citizen was given several fundaments right which is applicable to all citizen equally. More importantly, these right are the freedom that the constitution has given to every citizen.

These right are right to equality, right to freedom, right against exploitation, right to freedom of religion¸ culture and educational right, right to constitutional remedies, right to education. All these right give every freedom that they can’t get in any other country.

Value of Freedom

The real value of anything can only be understood by those who have earned it or who have sacrificed their lives for it. Freedom also means liberalization from oppression. It also means the freedom from racism, from harm, from the opposition, from discrimination and many more things.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Freedom does not mean that you violate others right, it does not mean that you disregard other rights. Moreover, freedom means enchanting the beauty of nature and the environment around us.

The Freedom of Speech

Freedom of speech is the most common and prominent right that every citizen enjoy. Also, it is important because it is essential for the all-over development of the country.

Moreover, it gives way to open debates that helps in the discussion of thought and ideas that are essential for the growth of society.

Besides, this is the only right that links with all the other rights closely. More importantly, it is essential to express one’s view of his/her view about society and other things.

To conclude, we can say that Freedom is not what we think it is. It is a psychological concept everyone has different views on. Similarly, it has a different value for different people. But freedom links with happiness in a broadway.

FAQs on Freedom

Q.1 What is the true meaning of freedom? A.1 Freedom truly means giving equal opportunity to everyone for liberty and pursuit of happiness.

Q.2 What is freedom of expression means? A.2 Freedom of expression means the freedom to express one’s own ideas and opinions through the medium of writing, speech, and other forms of communication without causing any harm to someone’s reputation.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Essays About Freedom: 5 Helpful Examples and 7 Prompts

Freedom seems simple at first; however, it is quite a nuanced topic at a closer glance. If you are writing essays about freedom, read our guide of essay examples and writing prompts.

In a world where we constantly hear about violence, oppression, and war, few things are more important than freedom. It is the ability to act, speak, or think what we want without being controlled or subjected. It can be considered the gateway to achieving our goals, as we can take the necessary steps.

However, freedom is not always “doing whatever we want.” True freedom means to do what is righteous and reasonable, even if there is the option to do otherwise. Moreover, freedom must come with responsibility; this is why laws are in place to keep society orderly but not too micro-managed, to an extent.

5 Examples of Essays About Freedom

1. essay on “freedom” by pragati ghosh, 2. acceptance is freedom by edmund perry, 3. reflecting on the meaning of freedom by marquita herald.

- 4. Authentic Freedom by Wilfred Carlson

5. What are freedom and liberty? by Yasmin Youssef

1. what is freedom, 2. freedom in the contemporary world, 3. is freedom “not free”, 4. moral and ethical issues concerning freedom, 5. freedom vs. security, 6. free speech and hate speech, 7. an experience of freedom.

“Freedom is non denial of our basic rights as humans. Some freedom is specific to the age group that we fall into. A child is free to be loved and cared by parents and other members of family and play around. So this nurturing may be the idea of freedom to a child. Living in a crime free society in safe surroundings may mean freedom to a bit grown up child.”

In her essay, Ghosh briefly describes what freedom means to her. It is the ability to live your life doing what you want. However, she writes that we must keep in mind the dignity and freedom of others. One cannot simply kill and steal from people in the name of freedom; it is not absolute. She also notes that different cultures and age groups have different notions of freedom. Freedom is a beautiful thing, but it must be exercised in moderation.

“They demonstrate that true freedom is about being accepted, through the scenarios that Ambrose Flack has written for them to endure. In The Strangers That Came to Town, the Duvitches become truly free at the finale of the story. In our own lives, we must ask: what can we do to help others become truly free?”

Perry’s essay discusses freedom in the context of Ambrose Flack’s short story The Strangers That Came to Town : acceptance is the key to being free. When the immigrant Duvitch family moved into a new town, they were not accepted by the community and were deprived of the freedom to live without shame and ridicule. However, when some townspeople reach out, the Duvitches feel empowered and relieved and are no longer afraid to go out and be themselves.

“Freedom is many things, but those issues that are often in the forefront of conversations these days include the freedom to choose, to be who you truly are, to express yourself and to live your life as you desire so long as you do not hurt or restrict the personal freedom of others. I’ve compiled a collection of powerful quotations on the meaning of freedom to share with you, and if there is a single unifying theme it is that we must remember at all times that, regardless of where you live, freedom is not carved in stone, nor does it come without a price.”

In her short essay, Herald contemplates on freedom and what it truly means. She embraces her freedom and uses it to live her life to the fullest and to teach those around her. She values freedom and closes her essay with a list of quotations on the meaning of freedom, all with something in common: freedom has a price. With our freedom, we must be responsible. You might also be interested in these essays about consumerism .

4. Authentic Freedom by Wilfred Carlson

“Freedom demands of one, or rather obligates one to concern ourselves with the affairs of the world around us. If you look at the world around a human being, countries where freedom is lacking, the overall population is less concerned with their fellow man, then in a freer society. The same can be said of individuals, the more freedom a human being has, and the more responsible one acts to other, on the whole.”

Carlson writes about freedom from a more religious perspective, saying that it is a right given to us by God. However, authentic freedom is doing what is right and what will help others rather than simply doing what one wants. If freedom were exercised with “doing what we want” in mind, the world would be disorderly. True freedom requires us to care for others and work together to better society.

“In my opinion, the concepts of freedom and liberty are what makes us moral human beings. They include individual capacities to think, reason, choose and value different situations. It also means taking individual responsibility for ourselves, our decisions and actions. It includes self-governance and self-determination in combination with critical thinking, respect, transparency and tolerance. We should let no stone unturned in the attempt to reach a state of full freedom and liberty, even if it seems unrealistic and utopic.”

Youssef’s essay describes the concepts of freedom and liberty and how they allow us to do what we want without harming others. She notes that respect for others does not always mean agreeing with them. We can disagree, but we should not use our freedom to infringe on that of the people around us. To her, freedom allows us to choose what is good, think critically, and innovate.

7 Prompts for Essays About Freedom

Freedom is quite a broad topic and can mean different things to different people. For your essay, define freedom and explain what it means to you. For example, freedom could mean having the right to vote, the right to work, or the right to choose your path in life. Then, discuss how you exercise your freedom based on these definitions and views.

The world as we know it is constantly changing, and so is the entire concept of freedom. Research the state of freedom in the world today and center your essay on the topic of modern freedom. For example, discuss freedom while still needing to work to pay bills and ask, “Can we truly be free when we cannot choose with the constraints of social norms?” You may compare your situation to the state of freedom in other countries and in the past if you wish.

A common saying goes like this: “Freedom is not free.” Reflect on this quote and write your essay about what it means to you: how do you understand it? In addition, explain whether you believe it to be true or not, depending on your interpretation.

Many contemporary issues exemplify both the pros and cons of freedom; for example, slavery shows the worst when freedom is taken away, while gun violence exposes the disadvantages of too much freedom. First, discuss one issue regarding freedom and briefly touch on its causes and effects. Then, be sure to explain how it relates to freedom.

Some believe that more laws curtail the right to freedom and liberty. In contrast, others believe that freedom and regulation can coexist, saying that freedom must come with the responsibility to ensure a safe and orderly society. Take a stand on this issue and argue for your position, supporting your response with adequate details and credible sources.

Many people, especially online, have used their freedom of speech to attack others based on race and gender, among other things. Many argue that hate speech is still free and should be protected, while others want it regulated. Is it infringing on freedom? You decide and be sure to support your answer adequately. Include a rebuttal of the opposing viewpoint for a more credible argumentative essay.

For your essay, you can also reflect on a time you felt free. It could be your first time going out alone, moving into a new house, or even going to another country. How did it make you feel? Reflect on your feelings, particularly your sense of freedom, and explain them in detail.

Check out our guide packed full of transition words for essays .If you are interested in learning more, check out our essay writing tips !

Martin is an avid writer specializing in editing and proofreading. He also enjoys literary analysis and writing about food and travel.

View all posts

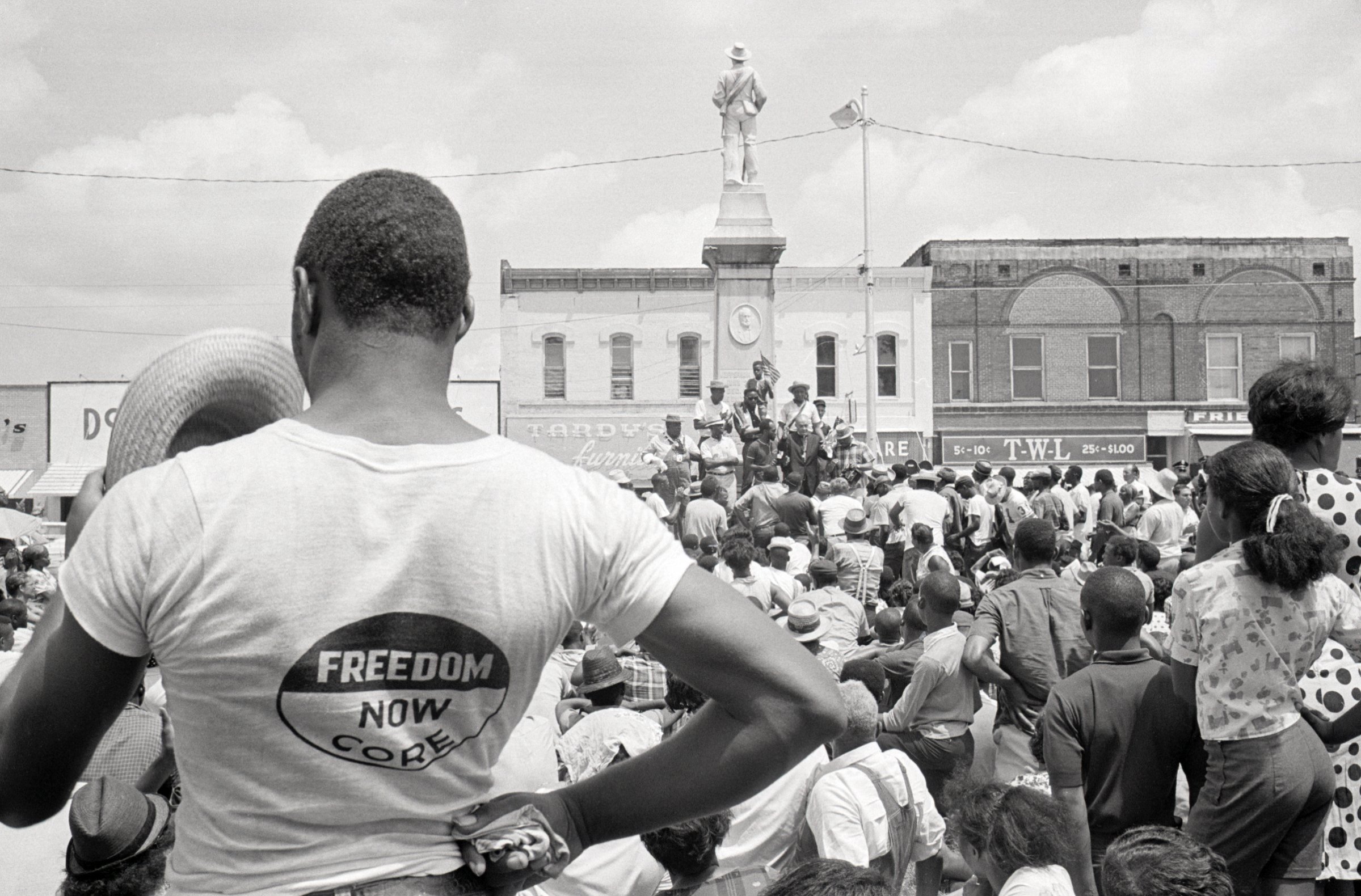

‘Freedom’ Means Something Different to Liberals and Conservatives. Here’s How the Definition Split—And Why That Still Matters

W e tend to think of freedom as an emancipatory ideal—and with good reason. Throughout history, the desire to be free inspired countless marginalized groups to challenge the rule of political and economic elites. Liberty was the watchword of the Atlantic revolutionaries who, at the end of the 18th century, toppled autocratic kings, arrogant elites and ( in Haiti ) slaveholders, thus putting an end to the Old Regime. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Black civil rights activists and feminists fought for the expansion of democracy in the name of freedom, while populists and progressives struggled to put an end to the economic domination of workers.

While these groups had different objectives and ambitions, sometimes putting them at odds with one another, they all agreed that their main goal—freedom—required enhancing the people’s voice in government. When the late Rep. John Lewis called on Americans to “let freedom ring” , he was drawing on this tradition.

But there is another side to the story of freedom as well. Over the past 250 years, the cry for liberty has also been used by conservatives to defend elite interests. In their view, true freedom is not about collective control over government; it consists in the private enjoyment of one’s life and goods. From this perspective, preserving freedom has little to do with making government accountable to the people. Democratically elected majorities, conservatives point out, pose just as much, or even more of a threat to personal security and individual right—especially the right to property—as rapacious kings or greedy elites. This means that freedom can best be preserved by institutions that curb the power of those majorities, or simply by shrinking the sphere of government as much as possible.

This particular way of thinking about freedom was pioneered in the late 18th century by the defenders of the Old Regime. From the 1770s onward, as revolutionaries on both sides of the Atlantic rebelled in the name of liberty, a flood of pamphlets, treatises and newspaper articles appeared with titles such as Some Observations On Liberty , Civil Liberty Asserted or On the Liberty of the Citizen . Their authors vehemently denied that the Atlantic Revolutions would bring greater freedom. As, for instance, the Scottish philosopher Adam Ferguson—a staunch opponent of the American Revolution—explained, liberty consisted in the “security of our rights.” And from that perspective, the American colonists already were free, even though they lacked control over the way in which they were governed. As British subjects, they enjoyed “more security than was ever before enjoyed by any people.” This meant that the colonists’ liberty was best preserved by maintaining the status quo; their attempts to govern themselves could only end in anarchy and mob rule.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

In the course of the 19th century this view became widespread among European elites, who continued to vehemently oppose the advent of democracy. Benjamin Constant, one of Europe’s most celebrated political thinkers, rejected the example of the French revolutionaries, arguing that they had confused liberty with “participation in collective power.” Instead, freedom-lovers should look to the British constitution, where hierarchies were firmly entrenched. Here, Constant claimed, freedom, understood as “peaceful enjoyment and private independence,” was perfectly secure—even though less than five percent of British adults could vote. The Hungarian politician Józseph Eötvös, among many others, agreed. Writing in the wake of the brutally suppressed revolutions that rose against several European monarchies in 1848, he complained that the insurgents, battling for manhood suffrage, had confused liberty with “the principle of the people’s supremacy.” But such confusion could only lead to democratic despotism. True liberty—defined by Eötvös as respect for “well-earned rights”—could best be achieved by limiting state power as much as possible, not by democratization.

In the U.S., conservatives were likewise eager to claim that they, and they alone, were the true defenders of freedom. In the 1790s, some of the more extreme Federalists tried to counter the democratic gains of the preceding decade in the name of liberty. In the view of the staunch Federalist Noah Webster, for instance, it was a mistake to think that “to obtain liberty, and establish a free government, nothing was necessary but to get rid of kings, nobles, and priests.” To preserve true freedom—which Webster defined as the peaceful enjoyment of one’s life and property—popular power instead needed to be curbed, preferably by reserving the Senate for the wealthy. Yet such views were slower to gain traction in the United States than in Europe. To Webster’s dismay, overall, his contemporaries believed that freedom could best be preserved by extending democracy rather than by restricting popular control over government.

But by the end of the 19th century, conservative attempts to reclaim the concept of freedom did catch on. The abolition of slavery, rapid industrialization and mass migration from Europe expanded the agricultural and industrial working classes exponentially, as well as giving them greater political agency. This fueled increasing anxiety about popular government among American elites, who now began to claim that “mass democracy” posed a major threat to liberty, notably the right to property. Francis Parkman, scion of a powerful Boston family, was just one of a growing number of statesmen who raised doubts about the wisdom of universal suffrage, as “the masses of the nation … want equality more than they want liberty.”

William Graham Sumner, an influential Yale professor, likewise spoke for many when he warned of the advent of a new, democratic kind of despotism—a danger that could best be avoided by restricting the sphere of government as much as possible. “ Laissez faire ,” or, in blunt English, “mind your own business,” Sumner concluded, was “the doctrine of liberty.”

Being alert to this history can help us to understand why, today, people can use the same word—“freedom”—to mean two very different things. When conservative politicians like Rand Paul and advocacy groups FreedomWorks or the Federalist Society talk about their love of liberty, they usually mean something very different from civil rights activists like John Lewis—and from the revolutionaries, abolitionists and feminists in whose footsteps Lewis walked. Instead, they are channeling 19th century conservatives like Francis Parkman and William Graham Sumner, who believed that freedom is about protecting property rights—if need be, by obstructing democracy. Hundreds of years later, those two competing views of freedom remain largely unreconcilable.

Annelien de Dijn is the author of Freedom: An Unruly History , available now from Harvard University Press.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Passengers Are Flying up to 30 Hours to See Four Minutes of the Eclipse

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Essay: The Complicated Dread of Early Spring

- Why Walking Isn’t Enough When It Comes to Exercise

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

How Do We Define Freedom?

Reilience skills of communication and finding purpose and meaning are necessary..

Posted January 13, 2021

The New Oxford American Dictionary definition of freedom is the “power or right to act, speak or think as one wants without hindrance or restraint.” What is your definition? What does the word "freedom" mean to you? How should freedom be exercised? And do you think that one of the purposes of the government of the United States is to ensure that people in this country have the freedom to act, speak or think as they want?

Realistically, there have always been limits to our freedom. One of the purposes of government is to make laws and to ensure that they are enforced. Relative to freedom, this means that we do not have the freedom to terrorize or endanger others. For example, we have laws against drunk driving. We have laws that require drivers and their passengers to wear a seat belt. In some states, there are laws that require a motorcycle rider to wear a helmet.

Freedom has traditionally been linked with the idea of responsibility. George Bernard Shaw expressed this succinctly, “Liberty means responsibility. That is why most men dread it.” It is an existential concept. To be free means that one has the burden of making choices and decisions. And in making those decisions and choices, we are responsible for both our own and others’ freedom.

The right to act freely and speak freely should end when it endangers others’ rights to do the same. This country is in crisis. Interestingly enough, it is a crisis over how we define freedom in this country. Each one of us needs to ask ourselves our definition of freedom and what limits, if any, should be imposed on our freedom.

This has been demonstrated clearly to us in the last few weeks, specifically in regard to the pandemic. Do Americans have the right to decide if they should wear a mask in public or if they should social distance? Many would say no. If the behavior endangers others, then they do not have the right to engage in it.

Restrictions on an individual's behavior as it relates to the health of other people is not new. If we recognize a public health danger to ourselves and others, we should act to eliminate it. This is why smoking in public places has been banned in most areas in this country. We do not have the freedom to endanger others.

Creating meaning and purpose in our lives and in our institutions is a critical part of being resilient, and God knows we need resilience at this point in time.

Ron Breazeale, Ph.D. , is the author of Duct Tape Isn’t Enough: Survival Skills for the 21st Century as well as the novel Reaching Home .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

267 Freedom Essay Topics & Examples

Need freedom topics for an essay or research paper? Don’t know how to start writing your essay? The concept of freedom is very exciting and worth studying!

📃 Freedom Essay: How to Start Writing

📝 how to write a freedom essay: useful tips, 🏆 freedom essay examples & topic ideas, 🥇 most interesting freedom topics to write about, 🎓 simple topics about freedom, 📌 writing prompts on freedom, 🔎 good research topics about freedom, ❓ research questions about freedom.

The field of study includes personal freedom, freedom of the press, speech, expression, and much more. In this article, we’ve collected a list of great writing ideas and topics about freedom, as well as freedom essay examples and writing tips.

Freedom essays are common essay assignments that discuss acute topics of today’s global society. However, many students find it difficult to choose the right topic for their essay on freedom or do not know how to write the paper.

We have developed some useful tips for writing an excellent paper. But first, you need to choose a good essay topic. Below are some examples of freedom essay topics.

Freedom Essay Topics

- American (Indian, Taiwanese, Scottish) independence

- Freedom and homelessness essay

- The true value of freedom in modern society

- How slavery affects personal freedom

- The problem of human rights and freedoms

- American citizens’ rights and freedoms

- The benefits and disadvantages of unlimited freedom

- The changing definition of freedom

Once you have selected the issue you want to discuss (feel free to get inspiration from the ones we have suggested!), you can start working on your essay. Here are 10 useful tips for writing an outstanding paper:

- Remember that freedom essay titles should state the question you want to discuss clearly. Do not choose a vague and non-descriptive title for your paper.

- Work on the outline of your paper before writing it. Think of what sections you should include and what arguments you want to present. Remember that the essay should be well organized to keep the reader interested. For a short essay, you can include an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

- Do preliminary research. Ask your professor about the sources you can use (for example, course books, peer-reviewed articles, and governmental websites). Avoid using Wikipedia and other similar sources, as they often have unverified information.

- A freedom essay introduction is a significant part of your paper. It outlines the questions you want to discuss in the essay and helps the reader understand your work’s purpose. Remember to state the thesis of your essay at the end of this section.

- A paper on freedom allows you to be personal. It should not focus on the definition of this concept. Make your essay unique by including your perspective on the issue, discussing your experience, and finding examples from your life.

- At the same time, help your reader to understand what freedom is from the perspective of your essay. Include a clear explanation or a definition with examples.

- Check out freedom essay examples online to develop a structure for your paper, analyze the relevance of the topics you want to discuss and find possible freedom essay ideas. Avoid copying the works you will find online.

- Support your claims with evidence. For instance, you can cite the Bill of Rights or the United States Constitution. Make sure that the sources you use are reliable.

- To make your essay outstanding, make sure that you use correct grammar. Grammatical mistakes may make your paper look unprofessional or unreliable. Restructure a sentence if you think that it does not sound right. Check your paper several times before sending it to your professor.

- A short concluding paragraph is a must. Include the summary of all arguments presented in the paper and rephrase the main findings.

Do not forget to find a free sample in our collection and get the best ideas for your essay!

- Freedom of Expression Essay For one to be in a position to gauge the eventuality of a gain or a loss, then there should be absolute freedom of expression on all matters irrespective of the nature of the sentiments […]

- Freedom of Speech in Social Media Essay Gelber tries to say that the history of the freedom of speech in Australia consists of the periods of the increasing public debates on the issue of human rights and their protection.

- Freedom Writers: Promoting Good Moral Values The movie portrays a strong and civilized view of the world; it encourages development and use of positive moral values by people in making the world a better place.

- Philosophy and Relationship between Freedom and Responsibility Essay As a human being, it is hard to make a decision because of the uncertainty of the outcome, but it is definitely essential for human being to understand clearly the concept and connection between freedom […]

- Freedom and equality According to Liliuokalani of Hawaii, the conquest contravened the basic rights and freedoms of the natives and their constitution by undermining the power of their local leaders.

- Rio (2011) and the Issue of Freedom As a matter of fact, this is the only scene where Blu, Jewel, Linda, Tulio, and the smugglers are present at the same time without being aware of each other’s presence.

- Human Freedom in Relation to Society Human freedom has to do with the freedom of one’s will, which is the freedom of man to choose and act by following his path through life freely by exercising his ‘freedom’).

- Human Will & Freedom and Moral Responsibility Their understanding of the definition of human will is based on the debate as to whether the will free or determined.

- Freedom and Determinism On the other hand, determinism theory explains that there is an order that leads to occurrences of events in the world and in the universe.

- The Efforts and Activities of the Paparazzi are Protected by the Freedom of the Press Clause of the Constitution The First Amendment of the American constitution protects the paparazzi individually as American citizens through the protection of their freedom of speech and expression and professionally through the freedom of the press clause.

- Four Freedoms by President Roosevelt Throughout the discussion we shall elaborate the four freedoms in a broader way for better understating; we shall also describe the several measures that were put in place in order to ensure the four freedoms […]

- “Long Walk to Freedom” by Nelson Mandela In the fast developing world, advances and progress move countries and nations forward but at the same time, some things are left behind and become a burden for the people and evolution to better life […]

- Fighting for the Right to Choose: Students Should Have the Freedom to Pick the Courses They Want Consequently, students should be allowed to pick the subjects which they are going to study together with the main one. Thus, students should be allowed to choose the subjects they need in accordance with their […]

- Chapters 4-6 of ”From Slavery to Freedom” by Franklin & Higginbotham At the same time, the portion of American-born slaves was on the increase and contributed to the multiracial nature of the population.

- Mandela’s Leadership: Long Walk to Freedom The current paper analyses the effectiveness of leadership with reference to Nelson Mandela, the late former president of South Africa, as depicted in the movie, Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom.

- Jean-Paul Sartre’s Views on Freedom For example, to Sartre, a prisoner of war is free, existentially, but this freedom does not exist in the physical realm.

- Rousseau and Kant on their respective accounts of freedom and right The difference in the approaches assumed by Kant and Rousseau regarding the norms of liberty and moral autonomy determine the perspective of their theories of justice.

- “Gladiator” by Ridley Scott: Freedom and Affection This desire to be free becomes the main motive of the film, as the plot follows Maximus, now enslaved, who tries to avenge his family and the emperor and regain his liberty.

- 70’s Fashion as a Freedom of Choice However, with the end of the Vietnam War, the public and the media lost interest in the hippie style in the middle of the decade, and began to lean toward the mod subculture. The 70’s […]

- Protecting Freedom of Expression on the Campus An annotated version of “Protecting Freedom of Expression on the Campus” by Derek Bok in The Boston Globe.*and these stars are where I have a question or opinion on a statement* For several years, universities […]

- Voices of Freedom The history of the country is made up of debates, disagreements and struggles for freedom that have seen the Civil War, and the Cold War which have changed the idea of freedom in the US.

- Social Values: Freedom and Justice It is evident that freedom and justice are mutually exclusive, as “the theory of justice signifies its implications in regards to freedom as a key ingredient to happiness”.

- Women in Early America: Struggle, Survival, and Freedom in a New World The writer shows that women had the same capacities as those of men but were not allowed to contribute their ideas in developing the country.

- Pettit’s Conception of Freedom as Anti-Power According to Savery and Haugaard, the main idea that Pettit highlights in this theory is the notion that the contrary to freedom is never interference as many people claim, but it is slavery and the […]

- Freedom in Henrik Ibsen’s “A Doll’s House” Literature Analysis In Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, the main character, Nora is not an intellectual, and spends no time scouring books or libraries or trying to make sense of her situation.

- Freedom in Antebellum America: Civil War and Abolishment of Slavery The American Civil War, which led to the abolishment of slavery, was one of the most important events in the history of the United States.

- Freedom and the Role of Civilization The achievements demonstrated by Marx and Freud play a significant role in the field of sociology and philosophy indeed; Marx believed in the power of labor and recognized the individual as an integral part of […]

- Balance of Media Censorship and Press Freedom Government censorship means the prevention of the circulation of information already produced by the official government There are justifications for the suppression of communication such as fear that it will harm individuals in the society […]

- “Human Freedom and the Self” by Roderick Chisholm According to the author, human actions do not depend on determinism or “free will”. I will use this idea in order to promote the best actions.

- “Freedom Riders”: A Documentary Revealing Personal Stories That Reflect Individual Ideology The ideal of egalitarianism was one of the attractive features of the left wing for many inquiring minds in the early decades of the 20th century.

- Art and Freedom. History and Relationship The implication of this term is that genus art is composed of two species, the fine arts, and the useful arts. This, according to Cavell, is the beauty of art.

- Power and Freedom in America Although it is already a given that freedom just like the concept love is not easy to define and the quest to define it can be exhaustive but at the end of the day what […]

- Concept of Individual Freedom Rousseau and Mill were political philosophers with interest in understanding what entailed individual freedom. This paper compares Rousseau’s idea of individual freedom with Mill’s idea.

- Predetermination and Freedom of Choice We assume that every happens because of a specific reason and that the effects of that event can be traced back to the cause.

- Freedom and Social Justice Through Technology These two remarkable minds have made significant contributions to the debates on technology and how it relates to liberty and social justice.

- Personal Understanding of Freedom Freedom is essential for individual growth and development, and it helps individuals to make informed decisions that are in alignment with their values and beliefs.

- Balancing Freedom of Speech and Responsibility in Online Commenting The article made me perceive the position of absolute freedom of speech in the Internet media from a dual perspective. This desire for quick attention is the creation of information noise, distracting from the user […]

- The Effect of Emotional Freedom Techniques on Nurses’ Stress The objectives for each of the three criteria are clearly stated, with the author explaining the aims to the reader well throughout the content in the article’s title, abstract, and introduction.

- The Freedom Summer Project and Black Studies The purpose of this essay is to discuss to which degree the story of the Freedom Summer project illustrates the concepts of politics outlined in Karenga’s book Introduction to black studies.

- Democracy: The Influence of Freedom Democracy is the basis of the political systems of the modern civilized world. Accordingly, the democracy of Athens was direct that is, without the choice of representatives, in contrast to how it is generated nowadays.

- Freedom of Speech as a Basic Human Right Restricting or penalizing freedom of expression is thus a negative issue because it confines the population of truth, as well as rationality, questioning, and the ability of people to think independently and express their thoughts.

- Kantian Ethics and Causal Law for Freedom The theory’s main features are autonomy of the will, categorical imperative, rational beings and thinking capacity, and human dignity. The theory emphasizes not on the actions and the doers but the consequences of their effects […]

- Principles in M. L. King’s Quest for African American Freedom The concept of a nonviolent approach to the struggles for African American freedom was a key strategy in King’s quest for the liberation of his communities from racial and social oppressions.

- Technology Revolutionizing Ethical Aspects of Academic Freedom As part of the solution, the trends in technology are proposed as a potential solution that can provide the necessary support to improve the freedom of expression as one of the ethical issues that affect […]

- The Journey Freedom Tour 2022 Performance Analysis Arnel Pineda at age 55 keeps rocking and hitting the high notes and bringing the entire band very successfully all through their live concert tour.

- Freedom of Speech and Propaganda in School Setting One of the practical solutions to the problem is the development and implementation of a comprehensive policy for balanced free speech in the classroom.

- Twitter and Violations of Freedom of Speech and Censorship The sort of organization that examines restrictions and the opportunities and challenges it encounters in doing so is the center of a widely acknowledged way of thinking about whether it is acceptable to restrict speech.

- Freedom of the Press and National Security Similarly, it concerns the freedom of the press of the media, which are protected in the United States of America by the First Amendment.

- The Views on the Freedom from Fear in the Historical Perspective In this text, fear is considered in the classical sense, corresponding to the interpretation of psychology, that is, as a manifestation of acute anxiety for the inviolability of one’s life.

- Freedom of Speech in Social Networks The recent case of blocking the accounts of former US President Donald Trump on Twitter and Facebook is explained by the violation of the rules and conditions of social platforms.

- Emotion and Freedom in 20th-Century Feminist Literature The author notes that the second layer of the story can be found in the antagonism between the “narrator, author, and the unreliable protagonist”.

- Analysis of UK’s Freedom of Information Act 2000 To preserve potentially disruptive data that must not be released to the public, the FOIA integrates several provisions that allow the officials to decline the request for information without suffering possible consequences.

- Fight for Freedom, Love Has No Labels, and Ad Council: Key Statement The most important part of the message, to me, is the fact that the freedoms mentioned in the PSA are not available to every American citizen, despite America being the land of freedom.

- Teachers’ Freedom of Speech in Learning Institutions The judiciary system has not clearly defined the limits of the First Amendment in learning institutions, and it’s a public concern, especially from the teachers.

- Freedom of Expression in the Classroom The NEA Code of Ethics establishes a link between this Freedom and a teacher’s responsibilities by requiring instructors to encourage “independent activity in the pursuit of learning,” provide “access to diverse points of view,” and […]

- Is There Press Freedom in Modern China? There is a large body of literature in the field of freedom of the press investigations, media freedom in China, and press freedom and human rights studies.

- Freedom of the Press in the Context of UAE It gives the people the ability to understand the insight of the government and other crucial activities happening within the country.

- Freedom of the Press in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) According to oztunc & Pierre, the UAE is ranked 119 in the global press freedom data, classifying the country as one of the most suppressive regarding the liberty of expression.

- Mill’s Thesis on the Individual Freedom The sphere of personal freedom is an area of human life that relates to the individual directly. The principle of state intervention is that individuals, separately or collectively, may have the right to interfere in […]

- Privacy and Freedom of Speech of Companies and Consumers At the same time, in Europe, personal data may be collected following the law and only with the consent of the individuals.

- Review of “Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom” From the youth, Mandela started to handle the unfairness of isolation and racial relations in South Africa. In Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom, Chadwick’s masterful screen memoir of Nelson Mandela passes on the anguish as […]

- Expansion of Freedom and Slavery in British America The settlement in the city of New Plymouth was founded by the second, and it laid the foundation for the colonies of New England.

- Power, Property, and Freedom: Bitcoin Discourse In the modern world, all people have the right to freedom and property, but not all have the power to decide who may have this freedom and property.

- Religious Freedom Policy Evaluation Ahmed et al.claim that the creation of the ecosystem can facilitate the change as the members of the community share their experiences and learn how to respond to various situations.

- The Concepts of Freedom and the Great Depression Furthermore, blacks were elected to construct the constitution, and black delegates fought for the rights of freedpeople and all Americans. African-Americans gained the freedom to vote, work, and be elected to government offices during Black […]

- Freedom of Choices for Women in Marriage in “The Story of an Hour” The story describes the sentiments and feelings of Louisa Mallard when she learns the news about her husband. The readers can see the sudden reaction of the person to the demise of her significant other.

- Freedom of Speech in Shouting Fire: Stories From the Edge of Free Speech Even though the First Amendment explicitly prohibits any laws regarding the freedom of speech, Congress continues to make exceptions from it.

- Personal Freedom: The Importance in Modern Society To show my family and friends how important they are to me, I try contacting them more often in the way they prefer.

- Economic Freedom and Its Recent Statements Economic freedom is an important indicator and benchmark for the level of income of companies or individual citizens of a country.

- The Freedom Concept in Plato’s “Republic” This situation shows that the concept of democracy and the freedom that correlates with it refers to a flawed narrative that liberty is the same as equality.

- Freedom of Speech as the Most Appreciated Liberty In the present-day world, the progress of society largely depends on the possibility for people to exercise their fundamental rights. From this perspective, freedom of speech is the key to everyone’s well-being, and, in my […]

- The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom In the introductory part of the book, the author discusses his main theses concerning the link between the development of networks and shifts in the economy and society.

- Freedom of Association for Radical Organizations This assertion is the primary and fundamental argument in the debate on this topic – radical groups should not use freedom of association to harm other people potentially.

- Freedom of Expression on the Internet Randall describes the challenges regarding the freedom of speech raised by the Internet, such as anonymity and poor adaptation of mass communication to the cyber environment.

- Black Sexual Freedom and Manhood in “For Colored Girls” Movie Despite the representation of Black sexual freedoms in men and women and Black manhood as a current social achievement, For Colored Girls shows the realities of inequality and injustice, proving womanism’s importance in America.

- Frederick Douglass’s My Bondage and My Freedom Review He criticizes that in spite of the perceived knowledge he was getting as a slave, this very light in the form of knowledge “had penetrated the moral dungeon”.

- The Essence of Freedom of Contract The legal roots of the notion of freedom of contract are manifested in the ideals of liberalism and theoretical capitalism, where the former values individual freedom and the latter values marker efficiency and effectiveness.

- Why Defamation Laws Must Prioritize Freedom of Speech The body of the essay will involve providing information on the nature of defamation laws in the USA and the UK, the implementation of such laws in the two countries, and the reason why the […]

- Domination in the Discussion of Freedom For this reason, the principle of anti-power should be considered as the position that will provide a better understanding of the needs of the target population and the desirable foreign policy to be chosen.

- Freedom or Security: Homeland Issues In many ways, the author sheds light on the overreactions or inadequate responses of the US government, which led to such catastrophes as 9/11 or the war in Iraq.

- War on Terror: Propaganda and Freedom of the Press in the US There was the launching of the “Center for Media and Democracy”, CMD, in the year 1993 in order to create what was the only public interest at that period. There was expansive use of propaganda […]

- The Freedom of Expression and the Freedom of Press It is evident that the evolution of standards that the court has adopted to evaluate the freedom of expression leaves a lot to be desired. The court has attempted to define the role of the […]

- Information and Communication Technology & Economic Freedom in Islamic Middle Eastern Countries This is a unique article as it gives importance to the role ecommerce plays in the life of the educationists and students and urges that the administrators are given training to handle their students in […]

- Is the Good Life Found in Freedom? Example of Malala Yousafzai The story of Malala has shown that freedom is crucial for personal happiness and the ability to live a good life.

- The Path to Freedom of Black People During the Antebellum Period In conclusion, the life of free blacks in 19th century America was riddled with hindrances that were meant to keep them at the bottom of society.

- Civil Rights Movement: Fights for Freedom The Civil Rights Movement introduced the concept of black and white unification in the face of inequality. Music-related to justice and equality became the soundtrack of the social and cultural revolution taking place during the […]

- Voices of Freedom: Lincoln, M. L. King, Kirkaldy He was named after his grandfather Abraham Lincoln, the one man that was popular for owning wide tracks of land and a great farmer of the time.

- Freedom: Malcolm X’s vs. Anna Quindlen’s Views However, in reality, we only have the freedom to think whatever we like, and only as long as we know that this freedom is restricted to thought only.

- Net Neutrality: Freedom of Internet Access In the principle of Net neutrality, every entity is entitled access and interaction with other internet users at the same cost of access.

- The Golden Age of Youth and Freedom However, it is interesting to compare it to the story which took place at the dawn of the cultural and sexual revolution in Chinese society.

- Academic Freedom: A Refuge of Intellectual Individualism Also known as intellectual, scientific or individual freedom, academic freedom is defined as the freedom of professionals and students to question and to propose new thoughts and unpopular suggestions to the government without jeopardizing their […]

- The Literature From Slavery to Freedom Its main theme is slavery but it also exhibits other themes like the fight by Afro-Americans for freedom, the search for the identity of black Americans and the appreciation of the uniqueness of African American […]

- John Stuart Mill on Freedom in Today’s Perspective The basic concept behind this rose because it was frustrating in many cases in the context of the penal system and legislation and it was viewed that anything less than a capital punishment would not […]

- Conformity Versus Freedom at University To the author, this is objectionable on the grounds that such a regimen infringes on the freedom of young adults and that there is much to learn outside the classroom that is invaluable later in […]

- US Citizens and Freedom As an example of freedom and obtaining freedom in the US, the best possible subject would be the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, particularly during 1963-64, as this would serve as the conceptual and […]

- Value of Copyright Protection in Relation to Freedom of Speech The phrase, freedom of expression is often used to mean the acts of seeking, getting, and transfer of information and ideas in addition to verbal speech regardless of the model used. It is therefore important […]

- Social Factors in the US History: Respect for Human Rights, Racial Equality, and Religious Freedom The very first years of the existence of the country were marked by the initiatives of people to provide as much freedom in all aspects of social life as possible.

- Freedom of Speech and the Internet On the one hand, the freedom of expression on the internet allowed the general public to be informed about the true nature of the certain events, regardless of geographical locations and restrictions.

- Freedom Definition Revision: Components of Freedom That which creates, sustains, and maintains life in harmony with the natural cycles of this planet, doing no harm to the ecology or people of the Earth- is right.

- Freedom of Information Act in the US History According to the legislation of the United States, official authorities are obliged to disclose information, which is under control of the US government, if it is requested by the public.

- Media Freedom in the Olympic Era The Chinese government is heavily involved in the affairs of the media of that country. In the past, it was the responsibility of government to fund media houses however; today that funding is crapped off.

- Managing the Internet-Balancing Freedom and Regulations The explosive growth in the usage of Internet forms the basis of new digital age. Aim of the paper is to explore the general role of internet and its relationship with the society.

- Freedom, Equality & Solidarity by Lucy Parsons In the lecture and article ‘The Principles of Anarchism’ she outlines her vision of Anarchy as the answer to the labor question and how powerful governments and companies worked for hand in hand to stifle […]

- Ways Liberals Define Freedom Liberals are identified by the way they value the freedom of individuals, freedom of markets, and democratic freedoms. The term freedom is characterized by Liberals as they use it within the context of the relationship […]

- Boredom and Freedom: Different Views and Links Boredom is a condition characterized by low levels of arousal as well as wandering attention and is normally a result of the regular performance of monotonous routines.

- The Idea of American Freedom Such implications were made by the anti-slavery group on each occasion that the issue of slavery was drawn in the Congress, and reverberated wherever the institution of slavery was subjected to attack within the South.

- Human Freedom: Liberalism vs Anarchism It is impoverished because liberals have failed to show the connection between their policies and the values of the community. More fundamentally, however, a policy formulated in such a way that it is disconnected from […]

- Liberal Definition of Freedom Its origins lie in the rejection of the authoritarian structures of the feudalistic order in Europe and the coercive tendencies and effects of that order through the imposition of moral absolutes.

- Newt Gingrich Against Freedom of Speech According to the constitution, the First Amendment is part of the United States Bill of rights that was put in place due to the advocation of the anti-federalists who wanted the powers of the federal […]

- Freedom is One of the Most Valuable Things to Man Political philosophers have many theories in response to this and it is necessary to analyze some of the main arguments and concepts to get a clearer idea of how to be more precise about the […]

- The Enlightment: The Science of Freedom In America, enlightment resulted to the formation of the American Revolution in the form of resistance of Britain imperialism. In the United States of America, enlightment took a more significant form as demonstrated by the […]

- Determinism and Freedom in the movie ‘Donnie Darko’ The term determinism states, the all the processes in the world are determined beforehand, and only chosen may see or determine the future.

- Spinoza’ Thoughts on Human Freedom The human being was once considered of as the Great Amphibian, or the one who can exclusively live in the two worlds, a creature of the physical world and also an inhabitant of the spiritual, […]

- Political Freedom According to Machiavelli and Locke In this chapter, he explains that “It may be answered that one should wish to be both, but, because it is difficult to unite them in one person, is much safer to be feared than […]

- Freedom From Domination: German Scientists’ View He made the greatest ever attempt to unify the country, as Western Europe was divided into lots of feudal courts, and the unification of Germany led to the creation of single national mentality and appearing […]

- The Freedom of Speech: Communication Law in US By focusing on the on goings in Guatemala, the NYT may have, no doubt earned the ire of the Bush administration, but it is also necessary that the American people are made aware of the […]

- Freedom of Speech and Expression in Music Musicians are responsible and accountable for fans and their actions because in the modern world music and lyrics become a tool of propaganda that has a great impact on the circulation of ideas and social […]

- American Vision and Values of Political Freedom The significance of the individual and the sanctity of life were all central to the conceptions of Plato, Aristotle, or Cicero.

- Democracy and Freedom in Pakistan Pakistan lies in a region that has been a subject of worldwide attention and political tensions since 9/11. US influence in politics, foreign and internal policies of Pakistan has always been prominent.

- Spanish-American War: The Price of Freedom He was also the only person in the history of the United States to have attained the rank of Admiral of the Navy, the most senior rank in the United States Navy.

- Male Dominance as Impeding Female Sexual Freedom Therefore, there is a need to further influence society to respect and protect female sexuality through the production of educative materials on women’s free will.

- Interrelation and Interdependence of Freedom, Responsibility, and Accountability Too much responsibility and too little freedom make a person unhappy. There must be a balance between freedom and responsibility for human happiness.

- African American History: The Struggle for Freedom The history of the Jacksons Rainbow coalition shows the rise of the support of the African American politicians in the Democratic party.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Definition of Freedom The case of Nicola Sacco can be seen as the starting point of the introduction of Roosevelt’s definition of freedom as liberty for all American citizens.

- Freedom of Speech and International Relations The freedom of speech or the freedom of expression is a civil right legally protected by many constitutions, including that of the United States, in the First Amendment.

- Canada in Freedom House Organization’s Rating The Freedom in the World Reports are most notable because of their contribution to the knowledge about the state of civil and political liberties in different countries, ranking them from 1 to 7.

- Philosophy of Freedom in “Ethics” by Spinoza Thus, the mind that is capable of understanding love to God is free because it has the power to control lust.

- Slavery Abolition and Newfound Freedom in the US One of the biggest achievements of Reconstruction was the acquisition of the right to vote by Black People. Still, Black Americans were no longer forced to tolerate inhumane living conditions, the lack of self-autonomy, and […]

- Japanese-American Internment: Illusion of Freedom The purpose of this paper is to analyze the internment of Japanese-Americans in Idaho as well as events that happened prior in order to understand how such a violation of civil rights came to pass […]

- The Existence of Freedom This paper assumes that it is the cognizance of the presence of choices for our actions that validates the existence of free will since, even if some extenuating circumstances and influences can impact what choice […]

- Philosophy, Ethics, Religion, Freedom in Current Events The court solely deals with acts of gross human rights abuses and the signatory countries have a statute that allows the accused leaders to be arrested in the member countries.

- Mill’s Power over Body vs. Foucault’s Freedom John Stuart Mill’s view of sovereignty over the mind and the body focuses on the tendency of human beings to exercise liberalism to fulfill their self-interest.

- Rousseau’s vs. Confucius’ Freedom Concept Similarly, the sovereignty of a distinctive group expresses the wholeness of its free will, but not a part of the group.

- The Importance of Freedom of Speech In a bid to nurture the freedom of speech, the United States provides safety to the ethical considerations of free conversations.

- Slavery and Freedom: The American Paradox Jefferson believed that the landless laborers posed a threat to the nation because they were not independent. He believed that if Englishmen ruled over the world, they would be able to extend the effects of […]

- Freedom in the Workplace of American Society In the workplace, it is vital to implement freedom-oriented policies that would address the needs of each employee for the successful performance of the company which significantly depends on the operation of every participant of […]

- 19th-Century Marxism with Emphasis on Freedom As the paper reveals through various concepts and theories by Marx, it was the responsibility of the socialists and scientists to transform the society through promoting ideologies of class-consciousness and social action as a way […]

- Political Necessity to Safeguard Freedom He determined that the existence of the declared principles on which the fundamental structure of equality is based, as well as the institutions that monitor their observance, is the critical prerequisite for social justice and […]

- Aveo’s Acquisition of Freedom Aged Care Portfolio The mode of acquisition points to the possibility that Freedom used the White Knight defense mechanism when it approached the Aveo group.

- Aveo Group’s Acquisition of Freedom Aged Care Pty Ltd The annual report of AVEO Group indicated that the company acquired Freedom Aged Care based on its net book value. It implies that the Aveo Group is likely to achieve its strategic objectives through the […]

- Freedom Hospital Geriatric Patient Analysis The importance of statistics in clinical research can be explained by a multitude of factors; in clinical management, it is used for monitoring the patients’ conditions, the quality of health care provided, and other indicators.

- Hegel and Marx on Civil Society and Human Freedom First of all, the paper will divide the concepts of freedom and civil society in some of the notions that contribute to their definitions.

- Individual Freedom: Exclusionary Rule The exclusionary rule was first introduced by the US Supreme Court in 1914 in the case of Weeks v.the United States and was meant for the application in the federal courts only, but later it […]

- History of American Conceptions and Practices of Freedom The government institutions and political regimes have been accused of allowing amarginalisation’ to excel in the acquisition and roles assigned to the citizens of the US on the basis of social identities.

- Canada’s Freedom of Speech and Its Ineffectiveness In the developed societies of the modern world, it is one of the major premises that freedom of expression is the pivotal character of liberal democracy.

- Freedom and Liberty in American Historical Documents The 1920s and the 1930s saw particularly ardent debates on these issues since it was the time of the First World War and the development of the American sense of identity at the same time.

- Anglo-American Relations, Freedom and Nationalism Thus, in his reflection on the nature of the interrelations between two powerful empires, which arose at the end of the 19th century, the writer argues that the striving of the British Empire and the […]

- American Student Rights and Freedom of Speech As the speech was rather vulgar for the educational setting, the court decided that the rights of adults in public places cannot be identic to those the students have in school.

- Freedom of Speech in Modern Media At the same time, the bigoted approach to the principles of freedom of speech in the context of the real world, such as killing or silencing journalists, makes the process of promoting the same values […]

- Singapore’s Economic Freedom and People’s Welfare Business freedom is the ability to start, operating and closing a business having in mind the necessary regulations put by the government.

- “Advancing Freedom in Iraq” by Steven Groves The aim of the article is to describe the current situation in Iraq and to persuade the reader in the positive role of the U.S.authorities in the promoting of the democracy in the country.

- Freedom: Definition, Meaning and Threats The existence of freedom in the world has been one of the most controversial topics in the world. As a result, he suggests indirectly that freedom is found in the ability to think rationally.

- Expression on the Internet: Vidding, Copyright and Freedom It can be defined as the practice of creating new videos by combining the elements of already-existing clips. This is one of the reasons why this practice may fall under the category of fair use.

- Doha Debate and Turkey’s Media Freedom He argued that the Turkish model was a work in progress that could be emulated by the Arab countries not only because of the freedom that the government gave to the press, but also the […]

- The Pursuit of Freedom in the 19th Century Britain The ambition to improve one’s life was easily inflated by the upper grade that focused on dominating the system at the expense of the suffering majority.

- The Story of American Freedom The unique nature of the United States traces its history to the formation of political institutions between 1776 and 1789, the American Revolution between 1776 and 1783 and the declaration of independence in 1776. Additionally, […]

- Military Logistics in Operation “Iraqi Freedom” It was also very easy for the planners to identify the right amount of fuel needed for distribution in the farms, unlike other classes of supply which had a lot of challenges. The soldiers lacked […]

- The Freedom of Information Act The Freedom of Information Act is popularly understood to be the representation of “the people’s right to know” the various activities of the government.

- The United States Role in the World Freedom The efforts of NATO to engage Taliban and al-Qaida insurgents in the war resulted in the spreading of the war into the North West parts of Pakistan.

- Fighting Terrorism: “Iraqi Freedom” and “Enduring Freedom” One is bound to be encouraged by the fact that the general and both his immediate and distant families had dedicated their services to the military of the USA and had achieved great heights in […]

- Freedom of Speech: Julian Assange and ‘WikiLeaks’ Case

- Do Urban Environments Promote Freedom?

- Claiming the Freedom to Shape Politics

- US Progress in Freedom, Equality and Power Since Civil War

- Thomas Jefferson’s Views on Freedom of Religion

- Religious Freedom and Labor Law

- Gilded Age and Progressive Era Freedom Challenges

- Philosophical Approach to Freedom and Determinism

- The Life of a Freedom Fighter in Post WWII Palestine

- Fighting for Freedom of American Identity in Literature

- Philosophy of Freedom in “The Apology“

- Philosophy in the Freedom of Will by Harry Frankfurt

- Advertising and Freedom of Speech

- How the Law Limits Academic Freedom?

- The Issue of American Freedom in Toni Morrison’s “Beloved”

- The Jewish Freedom Fighter Recollection

- Kuwait’s Opposition and the Freedom of Expression

- Abraham Lincoln: A Legacy of Freedom

- Freedom of Speech and Expression

- Multicultural Education: Freedom or Oppression

- “The Freedom of the Streets: Work, Citizenship, and Sexuality in a Gilded Age City” by Sharon Wood

- Information Freedom in Government

- Dr.Knightly’s Problems in Academic Freedom

- Mill on Liberty and Freedom

- Texas Women University Academic Freedom

- Freedom of speech in the Balkans

- Media Freedom in Japan

- Rivalry and Central Planning by Don Lavoie: Study Analysis

- Review of “Freedom Writers”

- Freedom Degree in Colonial America

- What Is ‘Liberal Representative Democracy’ and Does the Model Provide an Appropriate Combination of Freedom and Equality?

- Is the Contemporary City a Space of Control or Freedom?

- Native Americans Transition From Freedom to Isolation

- “The Weight of the Word” by Chris Berg

- What Does Freedom Entail in the US?

- Leila Khaled: Freedom Fighter or Terrorist?

- Environmentalism and Economic Freedom

- Freedom of Speech in China and Political Reform

- Colonial Women’s Freedom in Society

✍️ Freedom Essay Topics for College

- The S.E.C. and the Freedom of Information Act

- African Americans: A Journey Towards Freedom

- Freedom of the Press

- Coming of Age in Mississippi: The Black Freedom Movement

- Freedom of Women to Choose Abortion

- Human Freedom as Contextual Deliberation

- Women and Freedom in “The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin

- The Required Freedom and Democracy in Afghanistan

- PRISM Program: Freedom v. Order

- Human rights and freedoms

- Controversies Over Freedom of Speech and Internet Postings

- Gender and the Black Freedom Movement

- Culture and the Black Freedom Struggle

- Freedom from Poverty as a Human Right and the UN Declaration of Human Rights

- Personal Freedom in A Doll’s House, A Room of One’s Own, and Diary of a Madman

- Hegel’s Ideas on Action, Morality, Ethics and Freedom

- Satre human freedom

- The Ideas of Freedom and Slavery in Relation to the American Revolution

- Psychological Freedom

- The Freedom Concept

- Free Exercise Clause: Freedom and Equality

- Television Effects & Freedoms

- Government’s control versus Freedom of Speech and Thoughts

- Freedom of Speech: Exploring Proper Limits

- Freedom of the Will

- Benefits of Post 9/11 Security Measures Fails to Outway Harm on Personal Freedom and Privacy

- Civil Liberties: Freedom of the Media

- Human Freedom and Personal Identity

- Freedom of Religion in the U.S

- Freedom of Speech, Religion and Religious Tolerance

- Why Free Speech Is An Important Freedom

- The meaning of the word “freedom” in the context of the 1850s!

- American History: Freedom and Progress

- The Free Exercise Thereof: Freedom of Religion in the First Amendment

- Twilight: Freedom of Choices by the Main Character

- Frank Kermode: Timelessness and Freedom of Expression

- The meaning of freedom today

- Human Nature and the Freedom of Speech in Different Countries

- What Is the Relationship Between Personal Freedom and Democracy?

- How Does Religion Limit Human Freedom?

- What Is the Relationship Between Economic Freedom and Fluctuations in Welfare?

- How Effectively the Constitution Protects Freedom?

- Why Should Myanmar Have Similar Freedom of Speech Protections to the United States?

- Should Economics Educators Care About Students’ Academic Freedom?

- Why Freedom and Equality Is an Artificial Creation Created?

- How the Attitudes and Freedom of Expression Changed for African Americans Over the Years?

- What Are the Limits of Freedom of Speech?

- How Far Should the Right to Freedom of Speech Extend?

- Is There a Possible Relationship Between Human Rights and Freedom of Expression and Opinion?

- How Technology Expanded Freedom in the Society?

- Why Did Jefferson Argue That Religious Freedom Is Needed?

- How the Civil War Sculpted How Americans Viewed Their Nation and Freedom?

- Should Society Limit the Freedom of Individuals?

- Why Should Parents Give Their Children Freedom?

- Was Operation Iraqi Freedom a Legitimate and Just War?

- Could Increasing Political Freedom Be the Key To Reducing Threats?

- How Does Financial Freedom Help in Life?

- What Are Human Rights and Freedoms in Modern Society?

- How the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom Affects the Canadian Politics?

- Why Should Schools Allow Religious Freedom?

- Does Internet Censorship Threaten Free Speech?

- How Did the American Civil War Lead To the Defeat of Slavery and Attainment of Freedom by African Americans?

- Why Are Men Willing To Give Up Their Freedom?

- How Did the Economic Development of the Gilded Age Affect American Freedom?

- Should Artists Have Total Freedom of Expression?

- How Does Democracy, Economic Freedom, and Taxation Affect the Residents of the European Union?

- What Restrictions Should There Be, if Any, on the Freedom of the Press?

- How To Achieving Early Retirement With Financial Freedom?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 24). 267 Freedom Essay Topics & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/freedom-essay-examples/

"267 Freedom Essay Topics & Examples." IvyPanda , 24 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/freedom-essay-examples/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '267 Freedom Essay Topics & Examples'. 24 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "267 Freedom Essay Topics & Examples." February 24, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/freedom-essay-examples/.

1. IvyPanda . "267 Freedom Essay Topics & Examples." February 24, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/freedom-essay-examples/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "267 Freedom Essay Topics & Examples." February 24, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/freedom-essay-examples/.

- Freedom Of Expression Questions

- Equality Topics

- Free Will Paper Topics

- Constitution Research Ideas

- Civil Rights Movement Questions

- Respect Essay Topics

- Bill of Rights Research Ideas

- Liberalism Research Topics

- Civil Disobedience Essay Topics

- Tolerance Essay Ideas

- First Amendment Research Topics

- Social Democracy Essay Titles

- Personal Ethics Titles

- Justice Questions

- American Dream Research Topics

- Human Editing

- Free AI Essay Writer

- AI Outline Generator

- AI Paragraph Generator

- Paragraph Expander

- Essay Expander

- Literature Review Generator

- Research Paper Generator

- Thesis Generator

- Paraphrasing tool

- AI Rewording Tool

- AI Sentence Rewriter

- AI Rephraser

- AI Paragraph Rewriter

- Summarizing Tool

- AI Content Shortener

- Plagiarism Checker

- AI Detector

- AI Essay Checker

- Citation Generator

- Reference Finder

- Book Citation Generator

- Legal Citation Generator

- Journal Citation Generator

- Reference Citation Generator

- Scientific Citation Generator

- Source Citation Generator

- Website Citation Generator

- URL Citation Generator

- Proofreading Service

- Editing Service

- AI Writing Guides

- AI Detection Guides

- Citation Guides

- Grammar Guides

- Paraphrasing Guides

- Plagiarism Guides

- Summary Writing Guides

- STEM Guides

- Humanities Guides

- Language Learning Guides

- Coding Guides

- Top Lists and Recommendations

- AI Detectors

- AI Writing Services

- Coding Homework Help

- Citation Generators

- Editing Websites

- Essay Writing Websites

- Language Learning Websites

- Math Solvers

- Paraphrasers

- Plagiarism Checkers

- Reference Finders

- Spell Checkers

- Summarizers

- Tutoring Websites

Most Popular

Ai or not ai a student suspects one of their peer reviewer was a bot, how to summarize a research article, loose vs lose.

13 days ago

Typely Review

How to cite a blog, what is freedom definition essay example.

freepik.com

The given prompt: How do political, personal, and societal freedoms differ?

Freedom is a word that resonates deeply with most of us, often evoking powerful emotions. It is a term, however, that means different things in different contexts. From the vast political landscapes to the intimate corners of our minds, freedom has distinct implications. To grasp its true essence, let’s traverse the realms of political, personal, and societal freedoms.

Imagine living in a place where voicing your opinions could lead to imprisonment, or worse. Frightening, isn’t it? That’s where political freedom, or the lack of it, comes into play. Rooted in a country’s governance and laws, political freedom embodies the rights and liberties of its citizens. It speaks of democracy, of the right to vote, voice opinions, and participate in civic duties. This freedom ensures that power remains in the hands of the people and that leaders act in the nation’s best interest.

Shift the lens to a more individual perspective, and we encounter personal freedom. It’s about the choices we make daily, shaping our lives and destinies. Do you pursue a passion or follow a well-trodden path? Do you voice your disagreement in a conversation or remain silent? Personal freedom revolves around such choices. It’s the autonomy to think, act, and live according to one’s beliefs without undue external influence. This freedom lets us be authentic, honoring our true selves.

Now, imagine living in a society that dictates what you should wear, whom you should marry, or which profession you should choose. Sounds restrictive, right? Societal freedom is the antidote. It focuses on a community’s collective rights, ensuring that cultural norms or societal pressures do not stifle individual choices. This freedom ensures a harmonious coexistence, celebrating diversity and promoting inclusivity.

While these freedoms might seem distinct, they often intertwine and influence each other. A country that values political freedom is more likely to uphold societal and personal freedoms. Similarly, a society that cherishes diverse beliefs will likely advocate for both personal and political freedoms.

However, with freedom comes responsibility. Just as a bird must know its strength to fly high, individuals and societies must understand the boundaries of freedom. It should empower, not harm. It should uplift, not suppress. True freedom respects and values the freedoms of others.

In conclusion, while freedom is a universal aspiration, its interpretation varies across political, personal, and societal domains. It’s the right to vote, the power to choose, and the ability to coexist. In understanding these nuances, we appreciate the true depth of freedom. It’s a reminder that while freedom is a right, it’s also a privilege, one that we must cherish, nurture, and protect. Whether it’s in the ballot box, the choices we make, or the societies we build, freedom is the foundation of progress, happiness, and harmony.

Follow us on Reddit for more insights and updates.

Comments (0)

Welcome to A*Help comments!

We’re all about debate and discussion at A*Help.

We value the diverse opinions of users, so you may find points of view that you don’t agree with. And that’s cool. However, there are certain things we’re not OK with: attempts to manipulate our data in any way, for example, or the posting of discriminative, offensive, hateful, or disparaging material.

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

More from Definition Essay Examples and Samples

Oct 25 2023

What Is Identity? Definition Essay Sample

Oct 23 2023

What Is Respect? Definition Essay Example

Oct 20 2023