Inspiration to your inbox

- spirituality

- Law Of Attraction

- Beauty And FItness

- Better Life

- Energy Healing

- mental health

- Anger Management Tips

- relationship

- Personality

- Toxic People

- Blood Sugar

- Natural Remedies

- Pain Relief

- Weight Loss

- Friendship , Lifestyle

17 Reasons to Keep Old Friends in Your Life

- By Sarah Barkley

- Published on September 27, 2022

- Last modified May 21, 2023

Some of your best memories include old friends. The memories might come to mind unexpectedly, leaving you wondering how that old friend is doing now. Keeping friendships in your life allows you to stay in touch and create new memories.

Life isn’t as exciting or fulfilling without friends, with the friends who knew you the longest being around for all of it. They teach you about how people work outside of your immediate family. Many of them are there for you when life gets overwhelming, guiding and supporting you through every hardship.

As you age, you may lose touch with some of your friends. You’ll create new social relationships, and others will fizzle without a cause or reason. However, you should foster those friendships and stay in touch as often as possible.

You might not be able to see old friends often, but you can find ways to reconnect. Even if you’re each on entirely different life paths, you can stay in touch and influence one another.

Seventeen Reasons to Keep Old Friends in Your Life

1 – Old Freinds can give another perspective

If your old friends aren’t in your usual social group, they can offer another perspective. It’s good to have friends that offer their opinion because they can give you an unbiased thought or solution. When you’re in the middle of a problem, it can be hard for you to see a logical answer.

2 – Friendship is one more good reason to go on vacation

If the person lives far from you, keeping in touch can give you a reason to go on vacation. While this reason is superficial, it offers a nice escape to spend time together.

You’ll make memories with your friend during your trip, allowing your friendship to last forever. These trips will be experiences you’ll never regret.

3 – Friendship improves your mental health and makes your friend happy

Connecting with old friends can improve your mental health. It also boosts your friend’s mental health, making it helpful for both of you. Your old friend will appreciate it every time you reach out to them.

4 – You don’t have to impress old friends

Lifelong friends know you as no one else does. You’ll never have to impress them or feel like you must put on a show. These are friends you can go to when you’re at your worst because you know they’ll accept you as you are.

You’ll be that person for them, too, because they know they can let their guard down. It’s a powerful connection, and you can both appreciate the benefits. These relationships can be hard to come by, so don’t let go if you find one.

5 – Nostalgia

When you spend time with old friends, you’ll experience nostalgia as it brings a feeling of youthfulness. Memories will come rushing back, making you feel comfortable and safe. You can spend time remembering how things were before, basking in the joy of your memories.

6 – Friendship eases loneliness

Connection eases loneliness and symptoms of mental health conditions. People supporting you can make you feel good and find meaning.

You can continue staying in contact if your old friend lives far away. Studies show that electronic interaction is beneficial and can decrease the risk of depression and loneliness.

7 – Old friends understand your past

When you’ve known someone for a while, they understand your past. They’ll know how your family functions and what causes stress. These friends make good people vent to when you experience family problems because they’ll understand you and offer helpful advice.

Your old friends will also know what makes you tick and how you approach conflict. They know the little details others might not recognize, showing how much they understand who you are.

8 – Remind you of imagination and innocence

Childhood friends can help you remember the feeling of imagination and innocence. You knew them when life seemed simple and it was about playing together. If you still have a friend from early childhood, it’s a blessing you shouldn’t let dismiss.

9 – Provides comfort

A friend who knew you in older periods of life can give you comfort that you can’t find elsewhere. It’s an opportunity to talk about intimate details and heartache after a tragedy. You might not feel comfortable voicing these details in other social relationships but can feel safe with an old friend.

10 – Honesty

Your old friends will likely be honest with you because they’ve known you for so long. They’ll speak up when necessary and won’t tell you what you want to hear unless it’s the truth. While you must make your own decisions, you can trust their opinion on essential topics.

11 – Old friends influenced your social network

Your high school friends helped shape your social behavior and ability to connect. They taught you that it’s essential to have support from someone other than your family. Your friendship with these people impacts how you interact as an adult, and they can continue to help you grow.

12 – Seeing how your paths connect as adults

The people you were close to in the past might lead a completely different life now. However, you might have some similarities you hadn’t considered before. Spending time with them helps you see how you’re alike later in life .

You grew together for a while, and while you branch out, you still hold a connection nothing can take away. Everyone goes on to live separate lives, and it’s always fun to catch up and reconnect with the people that knew you so well.

13 – Old friends encourage growth

Staying in touch with someone you knew from the past can encourage you to keep growing. You’ll remember how much you’ve grown since then, and it’ll push you to keep going. Or you might realize that you haven’t grown as much as you’d hoped, and you’ll get motivated.

14 – Helps you remember your journey

Your old friends can help you remember where you came from and all the obstacles you overcame. They can also help you remember all your fun and memories. You’ll see how you have evolved while you embrace the past and remember your journey.

15 – Old friends know how to make you happy

Your oldest friends know what it takes to cheer you up and make you happy. They can sense if something’s wrong and start working on brightening your spirits before you even say anything. Old friends remember the things that cheer you up and won’t hesitate to make it happen.

16 – You can see how much you’ve changed

Your relationship helps you see how much you’ve changed if you have friends you only see occasionally. These friends know you at all points in your life, reminding you of your progress. They can also help you experience gratitude for where you are now.

Seeing how much you changed can help you remember where you began. It can also push you to keep growing because you see how far you’ve already come.

17 – Intellectual conversation

Experts indicate that college friends offer academic and social support involving intellectual conversation. You likely shared enlightening moments with these friends, including voicing concerns about the future and questioning everything.

College friends also saw you in intimate moments when you let loose and had fun. They may have helped you through rough nights and been there for you during your first experience away from home. These friends will support you and challenge your thoughts or ideas as you grow.

How to Reach Out to an Old Friend When You Haven’t Spoken for a While

Many people lose touch with old friends and feel awkward about reconnecting. However, there’s nothing to worry about because they’ll likely be happy to hear from you. Either way, it’s worth the attempt.

You can call the old friend, send a text message, or reach out another way. Tell them you’ve been thinking of them and ask how they’re doing. Depending on the conversation, ask if they’d like to get coffee and catch up.

When You Shouldn’t Reconnect with Old Friends

While keeping old friends in your life can be beneficial and enjoyable, there are some instances when you should avoid them. Only reach out if you can recall positive interactions with the person. Reaching out to harmful or toxic people can be detrimental to your well-being.

Consider a few things before you reconnect with an old friend, including:

- if it could be harmful to either of you

- what you want from the reconnection

- if you’re thinking of your best interests

- whether you’re willing to share details of your life

- if you feel comfortable with them

Avoid reaching out to someone if your relationship with them is unhealthy or abusive. Taking the time to understand why you want to reach out can help determine if you’re doing it for the right reasons.

Final Thoughts on Reasons to Keep Old Friends in Your Life

Old friends are treasures that you should keep in your life. They know you in ways no one else does and can bring positivity to your life.

If you’ve lost touch with old friends, reach out to them to reconnect. You’ll be glad you did, but make sure you’re not rekindling unhealthy friendships.

These reasons to keep old friends in your life can motivate you to reconnect. Don’t be afraid to invite them somewhere to catch up. Remember that they might be as happy as you are.

Comments & Discussions

Connect With Me

About the Author

Sarah Barkley

Sarah Barkley is a lifestyle blogger and freelance writer with a Bachelor’s Degree in Literature from Baker College.

She is experienced in all things related to parenting, marriage, and life as a millennial parent, but loves to learn new things. She enjoys the research that goes into a strong article, and no topic is off-limits to Sarah.

When she isn’t writing, she is immersed in a book or watching Gilmore Girls. Sarah loves reading classic novels but also enjoys a good thriller.

Related Articles

15 Behaviors When a Man Is Falling in Love

15 Behaviors of a Truly Loving Partner

10 Warning Signs Someone Has High-Functioning Drug Addiction

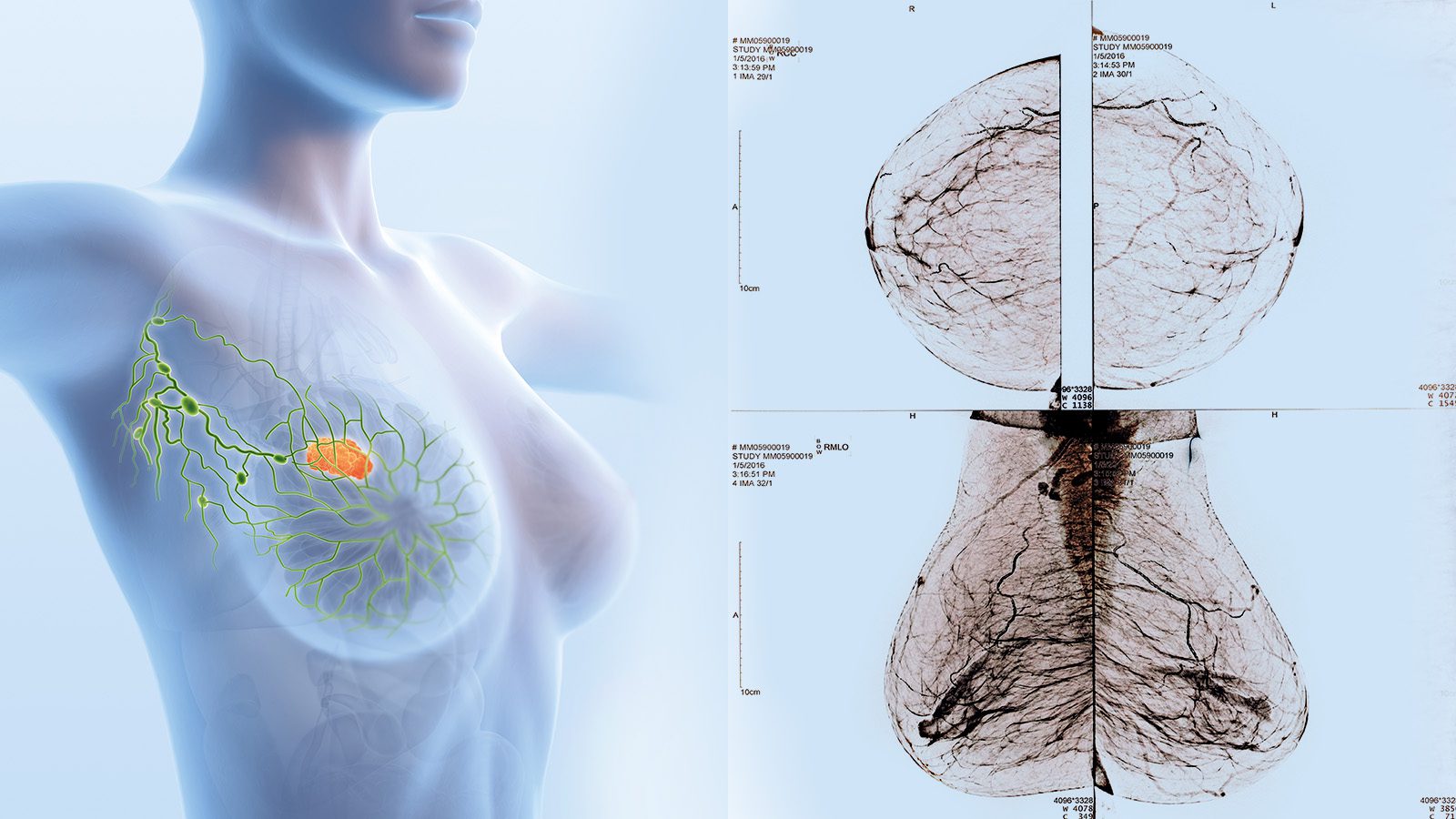

10 Silent Symptoms of Breast Cancer to Never Ignore

10 Signs of Partners With Unconditional Love

How to Attract a New Partner (Without Saying a Word)

20 Phrases That Reveal a Man Really Cares

10 Things a Cheating Partner Does Without Realizing It

Why Past Trauma Isn’t Worth It Anymore, But You Are

The community, our free community of positively powerful superfans.

Join our free community of superfans today and get access to courses, affirmations, accountability, and so much more… plus meet other like-minded positive people committed to living the power of positivity. Over the years, we’ve brought 50+ million people together through the Power of Positivity … this free community is an evolution of our journey so far, empowering you to take control, live your best life, and have fun while doing so.

Rise and Shine On! Master Your Day with the Ultimate Positive Morning Guide + Checklist

Stay connected with, every day is a day to shine. shine on.

This site is not intended to provide, and does not constitute, medical, health, legal, financial or other professional advice. This site is for entertainment purposes only. Our editors handpick the products that we feature. We may earn commission from the links on this page.

All rights Reserved. All trademarks and service marks are the property of their respective owners.

Please see our Privacy Policy | Terms of Service | About | Cookie Policy | Editorial Policy | Contact | Accessibility | [cookie_settings] | Disclaimer

- Copyright Power of Positivity 2024

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

Quote Remedy — Positive Energy+

When an Old Friendship Needs to Change, or End

The role you're playing in the friendship is no longer who you are. now what.

Posted October 31, 2021 | Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Nothing stays the same, including us. We change and grow over our lifetimes—thankfully. And often, our longest and dearest friendships need to change too, to keep up with who we are. The process of changing a long-term friendship isn’t usually an easy one, however, and sometimes, the friendship doesn’t survive. Sometimes the friendship can only be what it was when we were, or were willing to be, someone else.

Liza met Callie when they were college freshman and they quickly became best friends. After graduation, they both got jobs in New York City and lived as roommates for the majority of their twenties. Eventually, they both married and built families, and ended up living in different cities, but the friendship remained strong. After 38 years, they had a lifetime of shared history, and Liza considered Callie one of her most important and dearest friends.

But then something changed. An incident occurred that made Liza aware of an unspoken dynamic in the friendship that she had been participating in for decades. What became clear too, was that Liza wasn’t willing to engage in this pattern and to play this role any longer.

The incident was triggered because, in a rare moment, Liza was honest with Callie—about her experience with her. She told her dear friend that something Callie was doing in the relationship was painful for her. Furthermore, she asked Callie if she would consider a different way of doing things.

But what Liza’s honesty instigated in her oldest friend was exactly what Liza now understood had always been underlying and, to some degree, controlling the friendship, or at least her role in it. Callie’s response to hearing Liza’s experience was to go silent; she pulled away from the friendship without explanation. As Liza put it, it was "radio silence, with a distinct aroma of punishment .” When Liza then requested that they talk about what had happened, she was pummeled with a litany of things she had done to Callie over the years that Callie had not been okay with, but never said anything about. Liza’s inbox was soon filled with long, well-documented lists of her aggressions and issues, evidence for why she was a bad friend, guilty and deserving of Callie’s rage.

In fact, there had been numerous episodes in the friendship when Callie had unexplainably disappeared and stopped responding—once for several years. There had been a number of times too when Liza had said something minor, or misunderstood something Callie said, with no malintent, and had later come to find out that Callie had been enraged about the comment, stewing in it and building the case in her head against Liza.

But in this most recent episode, Liza became acutely aware of the rules of the bond with Callie, the role she had been playing to keep the friendship intact. Simultaneously, she became aware of her own truth, the fact that she had always walked on eggshells, and always had to work hard to get it right with Callie and not misstep. She realized that she had been living in fear of Callie’s anger for decades, and of her disappearing because of something “bad” Liza had done. The unspoken rules were that Liza behaved as Callie wanted her to behave. So too, Liza knew at a visceral level that she was not allowed to say anything about how Callie’s behavior affected her, and how she felt about Callie.

What the two old friends shared was a belief that Liza was guilty, responsible for whatever had ever gone wrong in the friendship. And that she needed to be what Callie deemed okay, so as to keep the friendship and not reaffirm her own guilt . Ultimately, Liza became aware of the role she had unconsciously agreed to play in the friendship.

But Liza also recognized how her friendship with Callie, which formed when they were just 18 and fresh out of their childhood homes, was a carbon copy of the relationship she had with her own mother. Like Callie, her mother had been emotionally erratic and would periodically withdraw her love because of something Liza had said or done. The narrative on Liza in her relationship with her mother was similarly that she was guilty, a selfish daughter who deprived her mother of the kind of love she deserved. At the same time, there was an understanding that she was never to bring up her mother’s behavior, or call her mother out on how she was affecting Liza. And most certainly, not what Liza herself might need from her mother—as a daughter. Not surprisingly, the role she played in her longest friendship was precisely as it was in her childhood home, where the nature of love and attachment is born.

In this relationship with her best friend, Liza had been playing the same role of the guilty one, the one who wasn’t allowed to have her own experience. Now aware of it, she knew this dynamic was over. The friendship couldn’t exist as it had existed; she wasn’t willing to walk on eggshells anymore, to behave so as not to be judged. Ultimately, she wasn't willing to abandon herself to maintain the bond.

We all do this: We form relationships that mirror our early experience, that keep us in the same roles we played with our early caretakers or other important people. We are, until we become aware of it, acting from underlying assumptions about what an intimate relationship demands, and who we have to be to feel loved. As a result, we end up in long-term friendships that are often unsatisfying at the deepest level, and keep us stuck in old patterns, not getting what we really need.

Start paying attention to the roles you play in your long-term friendships and who you have to be to maintain them, to keep being loved. Consider if this version of you is an outdated or limited one. Then, with compassion for yourself, consider who you are now, who you want to be in relationships at this point in your life, who you are willing to be—and who you are not willing to be.

The truth is, we are not who we were when some of our oldest friendships began, and yet we behave as if we still are, often at our own expense. Some friendships can survive our authenticity and evolution and some cannot. But if not, it makes one wonder if they are worth saving. It takes courage to unpack the rules of the bond, the unspoken agreements about who we are and are supposed to be in our longest friendships. But ultimately, this process sets us free from our old patterns, and allows us to experience new and more real and satisfying friendships. Bringing light to a relationship always includes risk, but in this case, it's worth it.

Nancy Colier, LCSW, Rev., is a psychotherapist, interfaith minister, and the author of The Emotionally Exhausted Woman, Can’t Stop Thinking , The Power of Off, and Inviting a Monkey to Tea .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

It's Been Too Long: 7 Reasons Why You Should Reconnect With Old Friends

Life wouldn’t be nearly as interesting, exciting or emotional without friends along for the ride. Friends are there to teach us about how other people work – they are our window to the world outside ourselves and our family life.

They introduce us to the diversity of human nature as well as teach us how difficult it can be to get along.

Friends serve a very important role in our development as individuals. They also function as a support team when life gets a bit overwhelming – which, at one point or another, it always does. As we grow older, we create new friendships and allow older ones to die out.

There are, however, several reasons we should reconnect with our roots and reach out to those who once were a fundamental part of our lives. Here are seven of them:

1. At the very least, you’ll experience a hint of nostalgia – everybody loves nostalgia.

Meeting up with old friends brings an air of youth along with it. It brings memories rushing to the forefront of our minds, allowing us to bask in the warmth.

Nostalgia is a beautiful feeling. It reminds us of the way things once were, the happiness that we experienced growing up, and all the wonder. If you have no other reason to contact any of your old friends, then do it for the sake of the smile it’ll bring to your face.

2. It’s fascinating to see how our roads diverge over time, taking those that were once close to us to opposite sides of the world.

Each of us writes his or her own story and although many stories have similar beginnings, the middle and the end will differ greatly. As humans, we often only rely on our own perspectives, paying attention to the way our own stories play out.

Reconnecting with past friends will allow you to see the world in a new light. It will show you how funny and weird life can really be. You were a part of their lives at one point and they a part of yours.

Maybe you influenced each other more than you know.

3. They’ll remind you of the person you once were and will allow you to better judge the person you have become.

Life seems to become more complicated and more difficult with age. Life’s daunting questions weigh heavier upon us year after year. With all that goes on, it’s easy to lose sight of ourselves.

To lose sight of the dreams we once had and the people we hoped to one day become. Life may not have been simpler back then, but to us it was.

We had a simpler way of thinking – more black and white, with much fewer greys. Getting in touch with your old friends will remind you of the person you used to be. Maybe you lost track. Maybe you’ve grown wiser. Either way, it’s good to know.

4. It may convince you that you knew how to find real friends better when you were younger than you do now.

Friends, generally speaking, aren’t easy to make – especially when you get older. The older we get, the more independent we become. Frankly, the older we get, the less we need friends. Or, rather, the less we believe that we need friends.

As adults, most of the people in our lives are mere acquaintances. However, we don’t always recognize them as such. We sometimes get lost in the illusion that the acquaintances in our lives are actual friends.

While most people become better judges of character with age, they also get lonelier and more desperate with age. You may have awful friends right now and not even know it.

5. On the other hand, you may realize that your judgment has improved significantly with time.

You may meet your old friends and decide that you were crazy thinking that these people should have stayed in your life. You may even remember why you cut them off in the first place.

A reminder of what friends shouldn’t be is just as good as a reminder of what friends ought to be.

6. It’s not unthinkable that you may reconnect and continue the friendship.

I feel that all the excitement of growing up, of going to high school, then college, then finding a job, makes us lose a lot of valuable connections. We lose touch with a lot of people due to geographical reasons.

We also lose touch with many friends because we get overly excited about making new ones. Maybe it’s time to rekindle the friendship.

7. Friends are a fundamental part of our lives – there should be a reason for either letting them go or keeping them around.

We shouldn’t simply leave things to chance and allow them to either dwindle or carry on simply because. But that’s what often happens. Friendship breakups don’t have the pizazz that relationship breakups do; they usually fade away as if they were never there to begin with.

This says nothing more about us other than the fact that we are egocentric and lazy creatures. You could have made an effort to stay friends, but you didn’t.

That’s not a very good reason not to keep a good person in your life. Good people are hard to come by.

Photo Courtesy: Tumblr

For More Of His Thoughts And Ramblings, Follow Paul Hudson On Twitter And Facebook .

Essays About Friendships: Top 6 Examples and 8 Prompts

Friendships are one of life’s greatest gifts. To write a friendship essay, make this guide your best friend with its essays about friendships plus prompts.

Every lasting relationship starts with a profound friendship. The foundations that keep meaningful friendships intact are mutual respect, love, laughter, and great conversations. Our most important friendships can support us in our most trying times. They can also influence our life for the better or, the worse, depending on the kind of friends we choose to keep.

As such, at an early age, we are encouraged to choose friends who can promote a healthy, happy and productive life. However, preserving our treasured friendships is a lifelong process that requires investments in time and effort.

6 Informative Essay Examples

1. the limits of friendships by maria konnikova, 2. friendship by ralph waldo emerson, 3. don’t confuse friendships and business relationships by jerry acuff, 4. a 40-year friendship forged by the challenges of busing by thomas maffai, 5. how people with autism forge friendships by lydia denworth, 6. friendships are facing new challenges thanks to the crazy cost of living by habiba katsha , 1. the importance of friendship in early childhood development, 2. what makes a healthy friendship, 3. friendships that turn into romance, 4. long-distance friendship with social media, 5. dealing with a toxic friendship, 6. friendship in the workplace, 7. greatest friendships in literature, 8. friendships according to aristotle .

…”[W]ithout investing the face-to-face time, we lack deeper connections to them, and the time we invest in superficial relationships comes at the expense of more profound ones.”

Social media is challenging the Dunbar number, proving that our number of casual friends runs to an average of 150. But as we expand our social base through social media, experts raise concerns about its effect on our social skills, which effectively develop through physical interaction.

“Friendship requires that rare mean betwixt likeness and unlikeness, that piques each with the presence of power and of consent in the other party.”

The influential American essayist Emerson unravels the mysteries behind the divine affinity that binds a friendship while laying down the rules and requirements needed to preserve the fellowship. To Emerson, friendship should allow a certain balance between agreement and disagreement. You might also be interested in these articles about best friends .

“Being friendly in business is necessary but friendships in business aren’t. That’s an important concept. We can have a valuable business relationship without friendship. Unfortunately, many mistakenly believe that the first step to building a business relationship is to develop a friendship.”

This essay differentiates friends from business partners. Using an anecdote, the essay warns against investing too much emotion and time in building friendships with business partners or customers, as such an approach may be futile in increasing sales.

“As racial tensions mounted around them, Drummer and Linehan developed a close connection—one that bridged their own racial differences and has endured more than four decades of evolving racial dynamics within Boston’s schools. Their friendship also served as a public symbol of racial solidarity at a time when their students desperately needed one.”

At a time when racial discrimination is at its highest, the author highlights a friendship they built and strengthened at the height of tensions during racial desegregation. This friendship proves that powerful interracial friendships can still be forged and separate from the politics of race.

“…15-year-old Massina Commesso worries a lot about friendship and feeling included. For much of her childhood, Massina had a neurotypical best friend… But as they entered high school, the other friend pulled away, apparently out of embarrassment over some of Massina’s behavior.”

Research debunks the myth that people with autism naturally detest interaction — evidence suggests the opposite. Now, research is shedding more light on the unique social skills of people with autism, enabling society to find ways to help them find true friendships.

“The cost of living crisis is affecting nearly everyone, with petrol, food and electricity prices all rising. So understandably, it’s having an impact on our friendships too.”

People are now more reluctant to dine out with friends due to the rapidly rising living costs. Friendships are being tested as friends need to adjust to these new financial realities and be more creative in cultivating friendships through lower-cost get-togethers.

8 Topic Prompts on Essays About Friendships

More than giving a sense of belonging, friendships help children learn to share and resolve conflicts. First, find existing research linking the capability to make and keep friends to one’s social, intellectual, and emotional development.

Then, write down what schools and households can do to reinforce children’s people skills. Here, you can also tackle how they can help children with learning, communication, or behavioral difficulties build friendships, given how their conditions interfere with their capabilities and interactions.

As with plants, healthy friendships thrive on fertile soil. In this essay, list the qualities that make “fertile soil” and explain how these can grow the seeds of healthy friendships. Some examples include mutual respect and the setting of boundaries.

Then, write down how you should water and tend to your dearest friendships to ensure that it thrives in your garden of life. You can also discuss your healthy friendships and detail how these have unlocked the best version of yourself.

Marrying your best friend is a romance story that makes everyone fall in love. However, opening up about your feelings for your best friend is risky. For this prompt, collate stories of people who boldly made the first step in taking their friendship to a new level.

Hold interviews to gather data and ask them the biggest lesson they learned and what they can share to help others struggling with their emotions for their best friend. Also, don’t forget to cite relevant data, such as this study that shows several romantic relationships started as friendships.

It’s challenging to sustain a long-distance friendship. But many believe that social media has narrowed that distance through an online connection. In your essay, explain the benefits social media has offered in reinforcing long-distance friendships.

Determine if these virtual connections suffice to keep the depth of friendships. Make sure to use studies to support your argument. You can also cite studies with contrasting findings to give readers a holistic view of the situation.

It could be heartbreaking to feel that your friend is gradually becoming a foe. In this essay, help your readers through this complicated situation with their frenemies by pointing out red flags that signal the need to sever ties with a friend. Help them assess when they should try saving the friendship and when they should walk away. Add a trivial touch to your essay by briefly explaining the origins of the term “frenemies” and what events reinforced its use.

We all know that there is inevitable competition in the workplace. Added to this are the tensions between managers and employees. So can genuine friendships thrive in a workplace? To answer this, turn to the wealth of experience and insights of long-time managers and human resource experts.

First, describe the benefits of fostering friendships in the workplace, such as a deeper connection in working toward shared goals, as well as the impediments, such as inherent competition among colleagues. Then, dig for case studies that prove or disprove the relevance and possibility of having real friends at work.

Whether it be the destructive duo like Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, or the hardworking pair of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John Watson, focus on a literary friendship that you believe is the ultimate model of friendship goals.

Narrate how the characters met and the progression of their interactions toward becoming a friendship. Then, describe the nature of the friendship and what factors keep it together.

In Book VIII of his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle writes about three kinds of friendships: pleasure, utility, and virtue. Dive deeper into the Greek philosopher’s mind and attempt to differentiate his three types of friendships.

Point out ideas he articulated most accurately about friendship and parts you disagree with. For one, Aristotle refutes the concept that friendships are necessarily built on likeness alone, hence his classification of friendships. Do you share his sentiments?

Read our Grammarly review before you submit your essay to make sure it is error-free! Tip: If writing an essay sounds like a lot of work, simplify it. Write a simple 5 paragraph essay instead.

Yna Lim is a communications specialist currently focused on policy advocacy. In her eight years of writing, she has been exposed to a variety of topics, including cryptocurrency, web hosting, agriculture, marketing, intellectual property, data privacy and international trade. A former journalist in one of the top business papers in the Philippines, Yna is currently pursuing her master's degree in economics and business.

View all posts

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

How to Maintain Friendships

By Anna Goldfarb

- Jan. 18, 2018

Age and time have a funny relationship: Sure, they both move in the same direction, but the older we get, the more inverse that relationship can feel. And as work and family commitments take up a drastically outsize portion of that time, it’s the treasured friendships in our life that often fade.

A recent study found that the maximum number of social connections for both men and women occurs around the age of 25. But as young adults settle into careers and prioritize romantic relationships, those social circles rapidly shrink and friendships tend to take a back seat.

The impact of that loss can be both social and physiological, as research shows that bonds of friendship are critical to maintaining both physical and emotional health. Not only do strong social ties boost the immune system and increase longevity, but they also decrease the risk of contracting certain chronic illnesses and increase the ability to deal with chronic pain, according to a 2010 report in the Journal of Health and Social Behavior.

“In terms of mortality, loneliness is a killer,” said Andrea Bonior , the author of “ The Friendship Fix .”

We don’t have to go out and spend every minute of every day with a rotating cast of friends, Dr. Bonior said. Rather, “It’s about feeling like you are supported in the ways that you want to be supported,” she added, and believing that the connections you do have are nourishing and strong.

An estimated 42.6 million Americans over the age of 45 suffer from chronic loneliness, which significantly raises their risk for premature death, according to a study by AARP. One researcher called the loneliness epidemic a greater health threat than obesity.

Most people aren’t aware that friendships are so beneficial: “They think of it as a luxury rather than the fact that it can actually add years to their life,” Dr. Bonior said.

The good news is that keeping cherished friendships afloat doesn’t need to be a huge time commitment. There are several things you can do to keep a bond strong even when your to-do list is a mile long.

Communicate expectations

Miriam Kirmayer , a therapist and friendship researcher, suggests being clear about your limits when you’re feeling frenzied.

“If there are certain days or weeks where you are going to be less available, giving your friend a heads up can go a long way toward minimizing misunderstandings or conflicts where somebody feels left out or like they’re being ignored,” she said.

Tell your friends how long you expect to be off the radar, how to communicate with you best during this time (“I’m drowning in emails; texts are better!”), and when your schedule is expected to go back to normal.

Nix ‘I’m too busy’ …

You might be booked from dusk until dawn, but without giving your friend context, that phrase “I’m too busy” can feel like a blowoff.

“When we hear somebody say, ‘I’m too busy,’ we don’t actually know if that is true for just their lives at this time, or if that’s their way of not really valuing us or wanting to spend time with us,” said Shasta Nelson , the author of “ Frientimacy: How to Deepen Friendships for Lifelong Health and Happiness .”

“Therefore, the friendship often just dies, not from lack of anything wrong or anybody even necessarily wanting it to die, but just simply chaotic lives and a lot of distance gets put in there,” she said.

Instead of offering vague, blanket statements about your bustling schedule, qualify your busyness: “I’m busy for the rest of the month,” or “I’m tied up until the end of the year.” Then make a counter offer. If you can’t meet face-to-face anytime soon, suggest a phone date, Skype session, or other way to connect so your friend doesn’t feel abandoned.

… Then examine your busyness

If you find yourself telling longtime pals you’re too snowed under to connect, it’s time to look at how you truly spend your time.

“If you can find the time to binge-watch TV shows and check Facebook a million times a day,” said Carlin Flora , the author of “ Friendfluence: The Surprising Way Friends Make Us Who We Are ,” “you can make time for your friends.”

Dr. Bonior agrees: “When you feel like you can’t squeeze in a book club or brunch or happy hour, pedicures or whatever it is, maybe assess a little bit more. Like, ‘O.K., well, how am I spending my time, and might there be a window in some of that time that actually allows for a real phone call or a walk around the block at lunch with one of my co-workers that I really like or whatever it might be?”

The author Laura Vanderkam credits tracking her time for helping her banish her “I’m too busy” mind-set. In making detailed notes on how she allotted her energy for a year, she found that “the stories I told myself about where my time went weren’t always true.” She suggests using an Excel spreadsheet with half-hour increments to track the day and using the Toggl app, for starters.

Once a clearer picture emerges of how one chooses to spend their time, it becomes possible to make positive, thoughtful changes.

Personal, small gestures are the way to go

Tailored, thoughtful text messages are a low-effort way to keep up connections when you’re short on time. The key is to share little bits of information about your day that your friend couldn’t glean from your Instagram feed or Snapchat story.

Ms. Kirmayer suggests making messages as personal as possible to show somebody you’re thinking about them.

“So remembering obviously big life events — things like birthdays are a given — but also maybe smaller things like: They had a doctor’s appointment coming up or you know they were going to have a stressful day at work and kind of checking in to see how it went,” she said. “Even a quick text message can go a long way.”

Ask questions that invite reveals (“How was your vacation? How’s your new job going?”) and avoid statements (“I hope you’re having a great day!” or “You’re in my thoughts”), which don’t tend to prompt meaningful back-and-forth exchanges.

Cultivate routines

Having a regular hang with your closest confidants can take the guesswork out of scheduling quality time.

“It might sound like you’re not aiming very high if you’re only going to see certain friends once a year, but if you have an annual barbecue or Memorial Day party or something, where it’s kind of a guarantee you’ll see certain friends,” Ms. Flora said, “that’s actually much better than kind of leaving it up to two people haggling over schedules.”

Another idea is multitask to combine your errands with some valuable BFF facetime. Ask a friend to come to your favorite spin class, join your book club or accompany you to a volunteer gig.

“The more things you can do together, potentially the more often you’ll be able to see each other,” Ms. Kirmayer said. “These repeated interactions are so important for keeping a friendship going.”

Come through when it counts

Another way to cement longstanding friendships when things are hectic is to go out of your way to attend any milestone events — fly in for the baby shower, attend the 40th birthday party, make an appearance at the retirement party. Just show up. There aren’t too many chances to make an impact in someone’s life, but if you move mountains and carve out time for your friend’s event, it’ll sustain a friendship for a long time.

“Once in a while, do a big gesture to those friends who you really, really care about and then that will kind of power the friendship for a while, even if you’re too busy to see each other,” Ms. Flora said. Being that person who comes through will “make that person feel loved and taken care of even if you’re not in constant contact.”

Ms. Nelson also suggests being aware of the three areas to measure and evaluate a functional friendship. The first area is positivity: laughter, affirmation, gratitude and any acts of service. The second is consistency, or having interactions on a continual basis, which makes people feel safe and close to each other. The third is vulnerability, which is the revealing and the sharing of our lives.

“Any relationship that doesn’t have those three things isn’t a healthy friendship,” Ms. Nelson said. If you’re noticing a cooling with a friend, usually one of these areas needs special consideration.

Knowing what makes a friendship tick is important because it allows us to be more effective, especially when time is in short supply. “Obviously we wouldn’t want a friendship to live on text messages, but it can certainly survive hectic times if we know where to put our energy,” Ms. Nelson said.

Acknowledge efforts made

While the energy expended to keep contact going may not always be equal, it’s important to be mindful of the attempts your friends make to connect. Reach out to nip resentment in the bud.

“If one person is consistently or chronically putting in more effort, issues can come up,” Ms. Kirmayer said. “Let your friend know that it means so much to you that they’re checking in so often and that you really appreciate it.”

She also recommends piping up if the balance feels off: “If you want them to kind of tone it down a little bit because you’re not able to respond all the time, you can say you feel really bad that you’re not able to get back to them all the time.” Addressing friends’ bids for attention can mean the difference between having a dear friendship flourish or fade during a frantic time.

“Most people just want to know they’re loved and thought of,” Ms. Nelson said. “If we can, like, give that validation and affirmation rather than just dismissing and saying we’re too busy, if we can kind of combine those things, most people understand and will still feel loved during that time.”

Anna Goldfarb is a freelance writer and author of the humor memoir, “ Clearly, I Didn’t Think This Through .”

A Guide to Building and Nurturing Friendships

Friendships are an essential ingredient in a happy life. here’s how to give them the care and attention they deserve..

How does one make meaningful friendships as an adult? Here are some suggestions , useful tools and tips from an expert .

If you are an introvert, it can be hard to reconcile the need for close connections with the urge to cancel social plans. Here is how to find your comfort zone .

A friendship with a sibling can be a lifelong gift. Whether you’ve always been close, or wish you got along better, here’s how to bolster your connection .

All relationships require some work. For your friendships to thrive , focus on your listening skills, compassion and communication. And make sure to spend time together .

American men are in a “friendship recession,” but experts say a few simple strategies can help. One tip? Practice being more vulnerable with your pals .

It’s quite common for people to feel jealousy or envy toward their friends. Luckily, there are ways to turn those emotions into an opportunity for growth.

Being a good friend means offering your support in times of need. Just remember: Sometimes less is better than more .

How Friendships Change in Adulthood

“We need to catch up soon!”

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic , Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

In the hierarchy of relationships, friendships are at the bottom. Romantic partners, parents, children—all these come first.

This is true in life, and in science, where relationship research tends to focus on couples and families. When Emily Langan, an associate communication professor at Wheaton College, goes to conferences for the International Association of Relationship Researchers, she says, “friendship is the smallest cluster there. Sometimes it’s a panel, if that.”

Friendships are unique relationships because unlike family relationships, we choose to enter into them. And unlike other voluntary bonds, such as marriages and romantic relationships, they lack a formal structure. You wouldn’t go months without speaking with or seeing your significant other (hopefully), but you might go that long without contacting a friend.

Still, survey upon survey upon survey shows how important people’s friends are to their happiness. And though friendships tend to change as people age, there is some consistency in what people want from them.

“I’ve listened to someone as young as 14 and someone as old as 100 talk about their close friends, and [there are] three expectations of a close friend that I hear people describing and valuing across the entire life course,” says William Rawlins, the Stocker Professor of Interpersonal Communication at Ohio University. “Somebody to talk to, someone to depend on, and someone to enjoy. These expectations remain the same, but the circumstances under which they’re accomplished change.”

The voluntary nature of friendship makes it subject to life’s whims in a way that more formal relationships aren’t. In adulthood, as people grow up and go away, friendships are the relationships most likely to take a hit. You’re stuck with your family, and you’ll prioritize your spouse. But where once you could run over to Jonny’s house at a moment’s notice and see if he could come out to play, now you have to ask Jonny if he has a couple hours to get a drink in two weeks.

The beautiful, special thing about friendship, that friends are friends because they want to be, that they choose each other, is “a double agent,” Langan says, “because I can choose to get in, and I can choose to get out.”

Throughout life, from grade school to the retirement home, friendship continues to confer health benefits, both mental and physical . But as life accelerates, people’s priorities and responsibilities shift, and friendships are affected, for better or, often, sadly, for worse.

The saga of adult friendship starts off well enough. “I think young adulthood is the golden age for forming friendships,” Rawlins says. “Especially for people who have the privilege and the blessing of being able to go to college.”

During young adulthood, friendships become more complex and meaningful. In childhood, friends are mostly other kids who are fun to play with; in adolescence, there’s a lot more self-disclosure and support between friends, but adolescents are still discovering their identity, and learning what it means to be intimate. Their friendships help them do that.

But “in adolescence, people have a really tractable self,” Rawlins says. “They’ll change.” How many band T-shirts from Hot Topic end up sadly crumpled at the bottom of dresser drawers because the owners’ friends said the band was lame? The world may never know. By young adulthood, people are usually a little more secure in themselves, more likely to seek out friends who share their values on the important things, and let the little things be.

To go along with their newly sophisticated approach to friendship, young adults also have time to devote to their friends. According to the Encyclopedia of Human Relationships , many young adults spend 10 to 25 hours a week with friends, and the 2014 American Time Use Survey found that people ages 20 to 24 spent the most time per day socializing on average of any age group.

Recommended Reading

Playing House : Finally, a TV Show Gets Female Friendships Right

What It’s Like to Get Worse at Something

American Trees Are Moving West, and No One Knows Why

College is an environment that facilitates this, with keggers and close quarters, but even young adults who don’t go to college are less likely to have some of the responsibilities that can take away from time with friends, such as marriage, or caring for children or older parents.

Friendship networks are naturally denser, too, in youth, when most of the people you meet go to your school or live in your town. As people move for school, work, and family, networks spread out. Moving out of town for college gives some people their first taste of this distancing. In a longitudinal study that followed pairs of best friends over 19 years, a team led by Andrew Ledbetter, an associate communications-studies professor at Texas Christian University, found that participants had moved an average of 5.8 times during that period.

“I think that’s just kind of a part of life in the very mobile and high-level transportation- and communication-technology society that we have,” Ledbetter says. “We don’t think about how that’s damaging the social fabric of our lives.”

We aren’t obligated to our friends the way we are to our romantic partners, our jobs, and our families. We’ll be sad to go, but go we will. This is one of the inherent tensions of friendships, which Rawlins calls “the freedom to be independent and the freedom to be dependent.”

“Where are you situated?” Rawlins asks me, in the course of explaining this tension. “Washington, D.C.,” I tell him.

“Where’d you go to college?”

“Okay, so you’re in Chicago, and you have close friends there. You say ‘Ah, I’ve got this great opportunity in Washington …’ and [your friend] goes, ‘Julie, you gotta take that!’ [She’s] essentially saying, ‘You’re free to go. Go there, do that, but if you need me, I’ll be here for you.’”

I wish he wouldn’t use me as an example. It makes me sad.

As people enter middle age, they tend to have more demands on their time, many of them more pressing than friendship. After all, it’s easier to put off catching up with a friend than it is to skip your kid’s play or an important business trip. The ideal of people’s expectations for friendship is always in tension with the reality of their lives, Rawlins says.

“The real bittersweet aspect is young adulthood begins with all this time for friendship, and friendship just having this exuberant, profound importance for figuring out who you are and what’s next,” Rawlins says. “And you find at the end of young adulthood, now you don’t have time for the very people who helped you make all these decisions.”

The time is poured, largely, into jobs and families. Not everyone gets married or has kids, of course, but even those who stay single are likely to see their friendships affected by others’ couplings. “The largest drop-off in friends in the life course occurs when people get married,” Rawlins says. “And that’s kind of ironic, because at the [wedding], people invite both of their sets of friends, so it’s kind of this last wonderful and dramatic gathering of both people’s friends, but then it drops off.”

In a set of interviews he did in 1994 with middle-aged Americans about their friendships, Rawlins wrote that “an almost tangible irony permeated these [adults’] discussions of close or ‘real’ friendship.” They defined friendship as “being there” for one another, but reported that they rarely had time to spend with their most valued friends, whether because of circumstances, or the age-old problem of good intentions and bad follow-through: “Friends who lived within striking distance of each other found that … scheduling opportunities to spend or share some time together was essential,” Rawlins writes. “Several mentioned, however, that these occasions often were talked about more than they were accomplished.”

As they move through life, people make and keep friends in different ways. Some are independent, make friends wherever they go, and may have more friendly acquaintances than deep friendships. Others are discerning, meaning they have a few best friends they stay close with over the years, but the deep investment means that the loss of one of those friends would be devastating. The most flexible are the acquisitive—people who stay in touch with old friends, but continue to make new ones as they move through the world.

Rawlins says that any new friends people might make in middle age are likely to be grafted onto other kinds of relationships—as with co-workers, or parents of their children’s friends—because it’s easier for time-strapped adults to make friends when they already have an excuse to spend time together. As a result, the “making friends” skill can atrophy. “[In a study we did,] we asked people to tell us the story of the last person they became friends with, how they transitioned from acquaintance to friend,” Langan says. “It was interesting that people kind of struggled.”

But if you plot busyness across the life course, it makes a parabola. The tasks that take up our time taper in old age. Once people retire and their kids have grown up, there seems to be more time for the shared-living kind of friendship again. People tend to reconnect with old friends whom they’ve lost touch with. And it seems more urgent to spend time with them—according to socio-emotional selectivity theory, toward the end of life, people begin prioritizing experiences that will make them happiest in the moment, including spending time with close friends and family.

And some people do manage to stay friends for life, or at least for a sizable chunk of life. But what predicts who will last through the maelstrom of middle age and be there for the silver age of friendship?

Whether people hold onto their old friends or grow apart seems to come down to dedication and communication. In Ledbetter’s longitudinal study of best friends, the number of months that friends reported being close in 1983 predicted whether they were still close in 2002, suggesting that the more you’ve invested in a friendship already, the more likely you are to keep it going. Other research has found that people need to feel like they are getting as much out of the friendship as they are putting in, and that that equity can predict a friendship’s continued success.

Hanging out with a set of lifelong best friends can be annoying, because the years of inside jokes and references often make their communication unintelligible to outsiders. But this sort of shared language is part of what makes friendships last. In the longitudinal study, the researchers were also able to predict friends’ future closeness by how well they performed on a word-guessing game in 1983. (The game was similar to Taboo, in that one partner gave clues about a word without actually saying it, while the other guessed.)

“Such communication skill and mutual understanding may help friends successfully transition through life changes that threaten friendship stability,” the study reads. Friends don’t necessarily need to communicate often, or intricately, just similarly.

Of course, people can communicate with friends in more ways than ever, and media multiplexity theory suggests that the more platforms through which friends communicate—texting and emailing, sending each other funny Snapchats and links on Facebook, and seeing each other in person—the stronger their friendship is. “If we only have the Facebook tie, that’s probably a friendship that’s in greater jeopardy of not surviving into the future,” Ledbetter says.

Though you would think we would all know better by now than to draw a hard line between online relationships and “real” relationships, Langan says her students still use “real” to mean “in-person.”

There are four main levels of maintaining a relationship, and digital communication works better for some than for others. The first is just keeping a relationship alive at all, just to keep it in existence. Saying “Happy birthday” on Facebook, liking a friend’s tweet—these are the life-support machines of friendship. They keep it breathing, but mechanically.

Next is keeping a relationship at a stable level of closeness. “I think you can do that online too,” Langan says. “Because the platforms are broad enough in terms of being able to write a message, being able to send some support comments if necessary.” It’s sometimes possible to repair a relationship online too (another maintenance level), depending on how badly it was broken—getting back in touch with someone, or sending a heartfelt apology email.

“But then when you get to the next level, which is: Can I make it a satisfying relationship? That’s I think where the line starts to break down,” Langan says. “Because what happens often is people think of satisfying relationships as being more than an online presence.”

Social media makes it possible to maintain more friendships, but more shallowly. And it can also keep relationships on life support that would (and maybe should) otherwise have died out.

“The fact that Tommy, who I knew when I was 5, is still on my Facebook feed is bizarre to me,” Langan says. “I don’t have any connection to Tommy’s current life, and going back 25 years ago, I wouldn’t. Tommy would be a memory to me. Like, I seriously have not seen Tommy in 35 years. Why would I care that Tommy’s son just got accepted to Notre Dame? Yay for him! He’s relatively a stranger to me. But in the current era of mediated relationships, those relationships never have to time out.”

By middle age, people have likely accumulated many friends from different jobs, different cities, and different activities, who don’t know one another at all. These friendships fall into three categories: active, dormant, and commemorative. Friendships are active if you are in touch regularly; you could call on them for emotional support and it wouldn’t be weird; if you pretty much know what’s going on with their lives at this moment. A dormant friendship has history; maybe you haven’t spoken in a while, but you still think of that person as a friend. You’d be happy to hear from them, and if you were in their city, you’d definitely meet up.

A commemorative friend is not someone you expect to hear from, or see, maybe ever again. But they were important to you at an earlier time in your life, and you think of them fondly for that reason, and still consider them a friend.

Facebook makes things weird by keeping these friends continually in your peripheral vision. It violates what I’ll call the camp-friend rule of commemorative friendships: No matter how close you were with your best friend from summer camp, it is always awkward to try to stay in touch when school starts again. Because your camp self is not your school self, and it dilutes the magic of the memory a little to try to attempt a pale imitation of what you had.

The same goes for friends you see only online. If you never see your friends in person, you’re not really sharing experiences so much as just keeping each other updated on your separate lives. It becomes a relationship based on storytelling rather than shared living—not bad, just not the same.

“This is one thing I really want to tell you,” Rawlins says. “Friendships are always susceptible to circumstances. If you think of all the things we have to do—we have to work, we have to take care of our kids, or our parents—friends choose to do things for each other, so we can put them off. They fall through the cracks.”

After young adulthood, he says, the reasons that friends stop being friends are usually circumstantial—due to things outside of the relationship itself. One of the findings from Langan’s “friendship rules” study was that “adults feel the need to be more polite in their friendships,” she says. “We don’t feel like, in adulthood, we can demand very much of our friends. It’s unfair; they’ve got other stuff going on. So we stop expecting as much, which to me is kind of a sad thing, that we walk away from that.” For the sake of being polite.

But the things that make friendship fragile also make it flexible. Rawlins’s interviewees tended to think of their friendships as continuous, even if they went through long periods in which they were out of touch. This is a fairly sunny view—you wouldn’t assume you were still on good terms with your parents if you hadn’t heard from them in months. But the default assumption with friends is that you’re still friends.

“That is how friendships continue, because people are living up to each other’s expectations. And if we have relaxed expectations for each other, or we’ve even suspended expectations, there’s a sense in which we realize that,” Rawlins says. “A summer when you’re 10, three months is one-thirtieth of your life. When you’re 30, what is it? It feels like the blink of an eye.”

Perhaps friends are more willing to forgive long lapses in communication because they’re feeling life’s velocity acutely too. It’s sad, sure, that we stop relying on our friends as much when we grow up, but it allows for a different kind of relationship, based on a mutual understanding of each other’s human limitations. It’s not ideal, but it’s real, as Rawlins might say. Friendship is a relationship with no strings attached except the ones you choose to tie, one that’s just about being there, as best as you can.

127 Friendship Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

When you have a good friendship topic, essay writing becomes as easy as it gets. We have some for you!

📝 Friendship Essay Structure

🏆 best friendship topic ideas & essay examples, 💡 good essay topics on friendship, 🎓 simple & easy friendship essay titles, 📌 most interesting friendship topics to write about, ❓ research questions about friendship.

Describing a friend, talking about your relationship and life experiences can be quite fun! So, take a look at our topics on friendship in the list below. Our experts have gathered numerous ideas that can be extremely helpful for you. And don’t forget to check our friendship essay examples via the links.

Writing a friendship essay is an excellent way to reflect on your relationships with other people, show your appreciation for your friends, and explore what friendship means to you. What you include in your paper is entirely up to you, but this doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t structure it properly. Here is our advice on structuring an essay on friendship:

- Begin by selecting the right topic. It should be focused and creative so that you can earn a high mark. Think about what friendship means to you and write down your thoughts. Reflect on your relationship with your best friend and see if you can write an essay that incorporates these themes. If these steps didn’t help – don’t worry! Fortunately, there are many web resources that can help you choose. Browse samples of friendship essays online to see if there are any topics that interest you.

- Create a title that reflects your focus. Paper titles are important because they grasp the reader’s attention and make them want to read further. However, many people find it challenging to name their work, so you can search for friendship essay titles online if you need to.

- Once you get the first two steps right, you can start developing the structure of your essay. An outline is a great tool because it presents your ideas in a clear and concise manner and ensures that there are no gaps or irrelevant points. The most basic essay outline has three components: introduction, body, and conclusion. Type these out and move to the next step. Compose an introduction. Your introduction should include a hook, some background information, and a thesis. A friendship essay hook is the first sentence in the introduction, where you draw the reader’s attention. For instance, if you are creating an essay on value of friendship, include a brief description of a situation where your friends helped you or something else that comes to mind. A hook should make the reader want to read the rest of the essay. After the hook, include some background information on your chosen theme and write down a thesis. A thesis statement is the final sentence of the first paragraph that consists of your main argument.

- Write well-structured body paragraphs. Each body paragraph should start with one key point, which is then developed through examples, references to resources, or other content. Make sure that each of the key points relates to your thesis. It might be useful to write out all of your key points first before you write the main body of the paper. This will help you to see if any of them are irrelevant or need to be swapped to establish a logical sequence. If you are composing an essay on the importance of friendship, each point should show how a good friend can make life better and more enjoyable. End each paragraph with a concluding sentence that links it to the next part of the paper.

- Finally, compose a conclusion. A friendship essay conclusion should tie together all your points and show how they support your thesis. For this purpose, you should restate your thesis statement at the beginning of the final paragraph. This will offer your reader a nice, well-balanced closure, leaving a good impression of your work.

We hope that this post has assisted you in understanding the basic structure of a friendship paper. Don’t forget to browse our website for sample papers, essay titles, and other resources!

- Gilgamesh and Enkidu Friendship Essay The role of friendship in the Epic of Gilgamesh is vital. This essay unfolds the theme of friendship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu that develops in the course of the story.

- Friendship of Amir and Hassan in The Kite Runner The idea of friendship in The Kite Runner is considered to be one of the most important, particularly in terms of how friendship is appreciated by boys of different classes, how close the concepts of […]

- Classification of Friendship Best friends An acquaintance is someone whose name you know, who you see every now and then, who you probably have something in common with and who you feel comfortable around.

- Friendship and Friend’s Support It is the ability to find the right words for a friend, help in a difficult moment, and find a way out together.

- Friendship as a Personal Relationship Friends should be people who are sources of happiness to one another and will not forsake each other even when everybody around is against them.

- The Confessions of St. Augustine on Friendship: Term Paper Augustine of Hippo believes that the only real source of friendship is God, and he adds that it is only through this God-man relationship that people can understand the ideal meaning of friendship.

- Defining of True Friendship This is the same devotion that my friends and I have toward each other. Another thing that best defines friends is the sacrifices that they are willing to make for each other.

- “Is True Friendship Dying Away?” and “The Price We Pay” Then Purpose of the essay is to depict the way social media such as Facebook and Twitter have influenced the lifestyles of every person in the world.

- Friendship in The Old Man and The Sea The book was the last published during the author’s lifetime, and some critics believe that it was his reflection on the topics of death and the meaning of life.

- Friendship’s Philosophical Description In order for a friendship to exist, the two parties must demonstrate first and foremost a willingness to ensure that only the best occurs to their counterpart.

- Friendship as Moral Experience One of the things I have realized over the course of the last few years is that while it is possible to experience friendship and have a deep, spiritual connection with another person, it is […]

- Greek and Roman Perspectives on Male Friendship in Mythology The reason for such attitude can be found in the patriarchal culture and the dominant role of free adult males in the Greek and Roman social life. However, this was not the only, and probably […]

- Friendship in the ‘Because of Winn Dixie’ by Kate Dicamillo In the book “Because of Winn Dixie”, Kate DiCamillo focuses on a ten-year-old girl India Opal Buloni and her friend, a dog named Winn Dixie.

- Effect of Friendship on Students’ Emotional Health The study discovered a significant positive correlation between the quality of new friendships and adjustment to university; this association is more robust for students living in residence than those commuting to university. Friday and Adkins […]

- Friendship’s meaning around the world Globally it’s very ludicrous today for people to claim that they are in a friendship yet they do not even know the true meaning of friendship.

- “Feminism and Modern Friendship” by Marilyn Friedman Individualism denies that the identity and nature of human beings as individuals is a product of the roles of communities as well as social relationships.

- Social Media Communication and Friendship According to Maria Konnikova, social media have altered the authenticity of relationships: the world where virtual interactions are predominant is likely to change the next generation in terms of the ability to develop full social […]

- Friendship Type – Companionship Relationship A friendship is ideally not an obsession since the latter involves a craving for another person that might even lead to violence just to be in site of the other party.

- The Theme of Friendship in the “Arranged” Film As can be seen, friendship becomes the source of improved emotional and mental well-being, encouraging Rochel and Nasira to remain loyal to their values and beliefs.

- True Friendship from Personal Perspective The perfect understanding of another person’s character and visions is one of the first characteristics of a true friendship. In such a way, true friendship is an inexhaustible source of positive emotions needed for everyone […]

- How to Develop a Friendship: Strategies to Meet New Friends Maintaining a connection with old friends and finding time to share life updates with them is a good strategy not to lose ties a person already has. A person should work hard to form healthy […]

- Friendship: To Stay or to Leave Each member of the group found out who really is a friend and who is not. This implies that the level of trust is high between Eddie and Vic.

- Faux Friendship and Social Networking The modern-day relationships have dissolved the meaning of the word friendship; as aromatic lovers refer to each other as friends, parents want their children to think of them as friends, teachers, clergymen and bosses have […]

- Trust Aspect of Friendship: Qualitative Study Given the previous research on preserving close communication and terminating it, the authors seek to examine the basics of productive friendship and the circumstances that contribute to the end of the interaction.

- Friendship and Peer Networking in Middle Childhood Peer networking and friendship have a great impact on the development of a child and their overall well-being. Students in elementary need an opportunity to play and network with their peers.

- Friendship in “The Song of Roland” This phrase sums up Roland’s predicament in the book as it relates to his reluctance to sound the Oliphant horn. In the final horn-blowing episode, Roland is aggressively persuaded to blow the horn for Charlemagne’s […]

- Analysis of Internet Friendship Issues Despite the correlation that develops on the internet, the question of whether social media can facilitate and guarantee the establishment of a real friend has remained a key area of discussion.

- The Importance of Friendship in “The Epic of Gilgamesh” At the beginning of the story, Gilgamesh, the king of the Sumerian city of Uruk, despite achievements in the development of the town, causes the dislike of his subjects.

- Educator-Student Relationships: Friendship or Authority? Ford and Sassi present the view that the combination of authority and the establishment of interpersonal relations should become the way to improve the performance of learners.

- Friendship in the Film “The Breakfast Club” The main themes which can be identified in the storyline are crisis as a cause and catalyst of friendship, friendship and belonging, and disclosure and intimacy in friendship.

- Friendship Police Department Organizational Change The one that is going to challenge the efforts, which will be aimed at rectifying the situation, is the lack of trust that the employees have for the new leader who they expect to become […]

- Friendship in the Analects and Zhuangzi Texts The author of “The Analects of Confucius” uses the word friend in the first section of the text to emphasize the importance of friendship.

- Is There Friendship Between Women? In conclusion, comparing my idea of women’s friendship discussed in my proposal to the theoretic materials of the course I came to a conclusion that strong friendship between women exists, and this is proved in […]

- Online Friendship Formationby in Mesch’s View The modern world tends to the situation when people develop the greatest empathy towards their online friends because it seems that the ratio and the deepness of these relationships can be controlled; written and posted […]

- Canadian-American Diefenbaker-Eisenhower Friendship In particular, the paper investigates the Mandatory Oil Import Program and the exemption of Canada from this initiative as well as the historical treaty that was officially appended by the two leaders in regard to […]

- Friendship from a Sociological Perspective For example Brazilians studying in Europe and United States were met with the stereotypes that Brazilians are warm people and are easy to establish friendships.

- Friendship Influencing Decisions When on Duty The main stakeholders are the local community, the judge, and the offenders. The right of the society is to receive objective and impartial treatment of its members.

- “Understanding Others, and Individual Differences in Friendship Interaction in Young Children”: Article Analysis The aspect of socio-cognitive abilities of small children in the process of interaction was disclosed with the help of psychological theories.

- Friendship: Sociological Term Review But one is not aware of that type of friendship; it is necessary to study it. Friendship is a matter of consciousness; love is absolutely unconscious.

- The Significance of Friendship in Yeonam The paper examines the depth and extent to which Yeonam was ready to go and if he was bound by the norms of the human friendship and association of his era.

- Cicero and Plutarch’s Views on Friendship He believed that befriending a man for sensual pleasures is the ideal of brute beasts; that is weak and uncertain with caprice as its foundation than wisdom. It is this that makes such carelessness in […]

- Friendship: The Meaning and Relevance Although the basic definition of a friendship falls under the category of somebody whom we feel a level of affection and trust for or perhaps a favored companion, the truth of the matter is that […]

- Gender and Cultural Studies: Intimacy, Love and Friendship Regardless of the driving force, intimacy and sexual connections are common in many happy relationships. Of significance is monogamy whose definition among the heterosexuals and lesbians remains a challenge.

- Fate of Friendship and Contemporary Ethics Is friendship possible in the modern world dominated by pragmatism and will it exist in the future? For instance, Cicero takes the point of view of the social entity, in other words, he defines friendship […]

- Feminism and Modern Friendship While criticizing these individuals, Marilyn asserts that the omission of sex and gender implies that these individuals wanted to affirm that social attachment such as societies, families, and nationalities contribute to identity rather than sex […]

- Creating a Friendship Culture This family will ensure every church member and youth is part of the youth ministry. I will always help every newcomer in the ministry.

- Friendship is in Everyone’s Life Though, different books were written in different times, the descriptions of a friendship have the same essence and estimate that one cannot be completely satisfied with his/her life if one does not have a friend.