- Open access

- Published: 21 April 2022

Domestic violence in Indian women: lessons from nearly 20 years of surveillance

- Rakhi Dandona 1 , 2 ,

- Aradhita Gupta 1 ,

- Sibin George 1 ,

- Somy Kishan 1 &

- G. Anil Kumar 1

BMC Women's Health volume 22 , Article number: 128 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

11 Citations

63 Altmetric

Metrics details

Prevalence of self-reported domestic violence against women in India is high. This paper investigates the national and sub-national trends in domestic violence in India to prioritise prevention activities and to highlight the limitations to data quality for surveillance in India.

Data were extracted from annual reports of National Crimes Record Bureau (NCRB) under four domestic violence crime-headings—cruelty by husband or his relatives, dowry death, abetment to suicide, and protection of women against domestic violence act. Rate for each crime is reported per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years, for India and its states from 2001 to 2018. Data on persons arrested and legal status of the cases were extracted.

Rate of reported cases of cruelty by husband or relatives in India was 28.3 (95% CI 28.1–28.5) in 2018, an increase of 53% from 2001. State-level variations in this rate ranged from 0.5 (95% CI − 0.05 to 1.5) to 113.7 (95% CI 111.6–115.8) in 2018. Rate of reported dowry deaths and abetment to suicide was 2.0 (95% CI 2.0–2.0) and 1.4 (95% CI 1.4–1.4) in 2018 for India, respectively. Overall, a few states accounted for the temporal variation in these rates, with the reporting stagnant in most states over these years. The NCRB reporting system resulted in underreporting for certain crime-headings. The mean number of people arrested for these crimes had decreased over the period. Only 6.8% of the cases completed trials, with offenders convicted only in 15.5% cases in 2018. The NCRB data are available in heavily tabulated format with limited usage for intervention planning. The non-availability of individual level data in public domain limits exploration of patterns in domestic violence that could better inform policy actions to address domestic violence.

Conclusions

Urgent actions are needed to improve the robustness of NCRB data and the range of information available on domestic violence cases to utilise these data to effectively address domestic violence against women in India.

Peer Review reports

The Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target 5 is to eliminate all forms of violence against women and girls, and the two indicators of progress towards this are the rates of intimate partner violence (IPV) and non-partner violence [ 1 ]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated a 26% prevalence of IPV in ever-married/partnered women aged 15 years or more globally in 2018, and this prevalence is higher at 35% for southern Asia region in which India falls [ 2 ]. The self-reported domestic violence (majority by an intimate partner) in any form is reported between 33 to 41% among ever-married women from India [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Furthermore, the suicide death rate among women in India was reported to be twice the global rate [ 9 ], and housewives account for the majority of suicide deaths, the reasons for which are documented as “personal/social” [ 10 ].

Domestic violence was first recognized as a punishable offence in India in 2005 with the passing of the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act (PWDVA) [ 11 , 12 ]. A significant focus of domestic violence against women in India has been on dowry-related harassment. Dowry is the transfer of goods, money and/or property from the bride’s family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage [ 13 ], initially meant to provide funds to women who were unable to inherit family property [ 14 ]. Dowry is very prevalent in India [ 15 ], and it has propagated domestic violence as means to extract money or property from the bride and her family [ 13 , 16 ]. While earlier sections of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) criminalized only dowry-related domestic violence, PWDVA expanded legal recourse for domestic violence beyond dowry harassment for more effective protection of the rights of women guaranteed under the Constitution who are victims of violence of any kind occurring within the family [ 11 ].

The major official source of surveillance for domestic violence in India are the reports compiled by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) [ 17 ]. Though under-reporting in NCRB reports is well documented for certain types of injuries [ 9 , 10 , 18 ], it remains the most comprehensive longitudinal source of domestic violence available at the state-level for India. We undertook a situational analysis for the years 2001 to 2018 using the NCRB reports to highlight the trends in the reported magnitude of domestic violence over time, to highlight the variations within country that could facilitate prioritization of immediate actions for prevention, and to discuss the limitations of the available NCRB reports for surveillance.

The primary source of the NCRB data is the First Information Report (FIR) completed by a police officer for any domestic violence incident which is compiled at the state level and provided to NCRB. FIR is a document prepared by police when they receive information about the commission of a cognizable offence either by the victim of the cognizable offence or by someone on their behalf [ 19 , 20 ]. It captures the date, time and location of offence, the details of offence, the details of victim and person reporting the offence, and steps taken by the police after receiving these details. The NCRB reports provide summary data based on these FIRs, which we utilized from 2001 to 2018 available in the public domain for this analysis. The details of data extracted and utilized are described below.

Type of data

Four crime headings corresponding to domestic violence related crimes against women were considered after consultation with legal experts who dealt with domestic violence cases based on the crime headings under which these are registered in India —cruelty by husband or his relatives, dowry death, abetment of suicide of women, and cases registered under PWDVA (Additional file 1 : Table S1). A case is filed under ‘cruelty by husband or his relatives’ (Section 498A of the IPC) when there is evidence of violence causing grave injury or of harassment to fulfil an unlawful demand for property [ 21 ]. Case of death of a woman within 7 years of marriage with evidence of dowry harassment is filed under dowry death (IPC Section 304B) [ 22 ]. As domestic violence is known as a risk factor for death by suicide among married women, we also considered the cases registered under abetment of suicide of women [ 23 ]. The cases under the PWDVA act criminalize perpetrators of domestic violence, defined to include physical, verbal, sexual, emotional and economic abuse in addition to dowry-related violence [ 11 ]. The NCRB reports data based on the “Principal Offence Rule,” which means that regardless of the number of offences under which a case of domestic violence is legally registered, it is reported only under the most serious crime heading by the NCRB [ 24 ].

Data extraction

NCRB reports included the number of cases filed as well as the number of victims under each of the four crime headings for 2014–2018 but reported only the number of cases filed from 2001 to 2013. The ratio of the number of cases to victims was 1.0 for 2014 to 2018, and hence we use the number of cases filed for this analysis from 2001 to 2018. Individual level-data is not published in the NCRB report.

Data for cruelty by husband or his relatives and for dowry death were available from 2001 to 2018, while data for abetment of suicide of women and PWDVA were available only from 2014 to 2018. We extracted the number of cases filed under each of the four domestic violence crime heads for each year for each state and for India. We also extracted data on the number of persons arrested under each crime category, which were available from 2001 to 2015 for the states and until 2018 for India. Here too, the data on abetment of suicide and PWDVA was available from 2014 to 2018 only. Lastly, we extracted data on the number of legal cases filed for these crimes and their current status in the judicial system. This legal data was available cumulatively for only India, and since it could not be extrapolated for each year from the tables, we analyzed this only for 2018.

Data analysis

Our analysis was aimed at understanding trends in the rate for each type of domestic violence crime heading. We calculated the rate of cruelty by husband or his relatives and dowry deaths from 2001 to 2018, and the rate of abetment of suicide of women and PWDVA from 2014 to 2018. As the NCRB reports do not specify the age of women who had reported these crimes, we assumed the age group of women to be 15–49 years to estimate the rates as the previous reports on domestic violence in India are predominately for women aged 15–49 years [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ]. We used the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study 2019 state-wise annual population estimates for women aged 15–49 years as the denominator [ 32 ], and report the rates per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years with 95% confidence intervals (CI) estimated for these rates. We report these rates across three administrative splits: nationally, by groups of state and individual state. The state groups were populated based on the Socio-demographic Index (SDI) computed by the GBD study, which uses lag distributed income, average years of education for population > 15 years of age, and total fertility rate [ 9 , 32 ].

To assess the trends in arrests related to domestic violence crimes, we computed the mean number of people arrested under each crime heading by dividing the number of people arrested with the total number of cases. The statistical analysis was done using MS Excel 2016, and maps were created using QGIS [ 33 ]. As this analysis used aggregated data available in the public domain, no ethics approval was necessary.

Cruelty by husband or his relatives

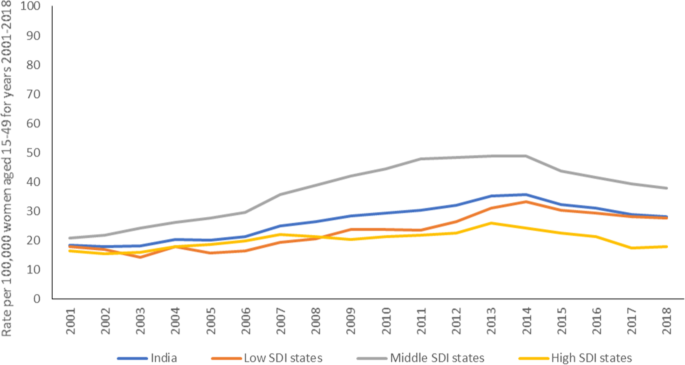

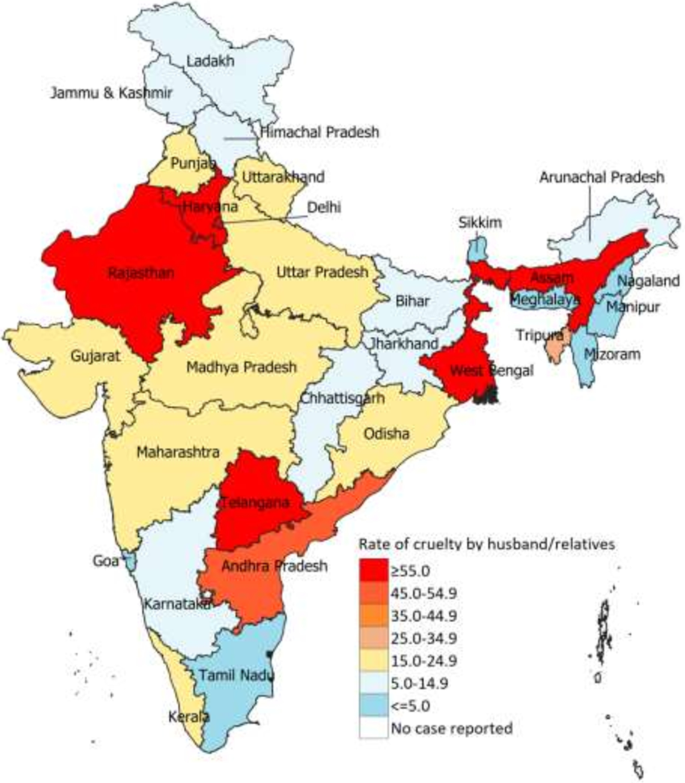

A total of 1,548,548 cases were reported under cruelty by husband or his relatives in India from 2001 to 2018, with 554,481 (35.8%) between 2014 and 2018. The reported rate of this crime in India was 18.5 (95% CI 18.3–18.6) in 2001 and 28.3 (95% CI 28.1–28.5) in 2018 per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years, marking a significant increase of 53% (95% CI 51.7–54.3) over this period (Table 1 ). This rate was 37.9 (95% CI 37.5–38.3) for the middle SDI states as compared with 27.6 (95% CI 27.4–27.8) in the low- and 18.1 (95% CI 17.8–18.4) in the high-SDI states in 2018 (Table 1 ). This reported crime rate remained higher in the middle SDI states between 2001 and 2018 as compared with the other states, reaching its highest levels between 2011 and 2014 (Fig. 1 ). Wide variations were seen in the rate for reported cruelty by husband or his relatives in 2018 at the state-level, which ranged from 0.5 (95% CI -0.05 0–1.5) in Sikkim to 113.7 (95% CI 111.6–115.8) in Assam (Table 1 and Fig. 2 ). The state of Delhi, Assam, West Bengal, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya and Jammu and Kashmir documented > 160% increase in this reported crime rate during 2001–2018 (Table 1 ). The greatest decline in the rate of this reported crime was seen in Mizoram, 74.3% from 2001 to 2018 (Table 1 ).

Yearly trend in the rate of cruelty by husband or his relatives per 100,000 women of 15–49 years, 2001–2018. SDI denotes Socio-demographic Index

Crime rate for cruelty by husband or his relatives per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years in 2018 in India, by state

Interestingly, the 53% increase in this reported crime rate between 2001 and 2018 for India was accounted for by increased rates for only a few states, and the rate remained stagnant in most states (Additional file 2 : Fig. S1, Additional file 3 : Fig. S2, Additional file 4 : Fig. S3). Only the states of Assam and Rajasthan among the low SDI states (Additional file 2 : Fig. S1), Andhra Pradesh and Tripura among the middle SDI states (Additional file 3 : Fig. S2), and Kerala and Delhi among the high SDI states (Additional file 4 : Fig. S3) showed increased reporting of this crime over the study period. The mean number of persons arrested under this crime in India decreased from 2.2 in 2001 to 1.1 in 2018, and the numbers were similar across the state SDI groups (Additional file 5 : Fig. S4).

Dowry deaths

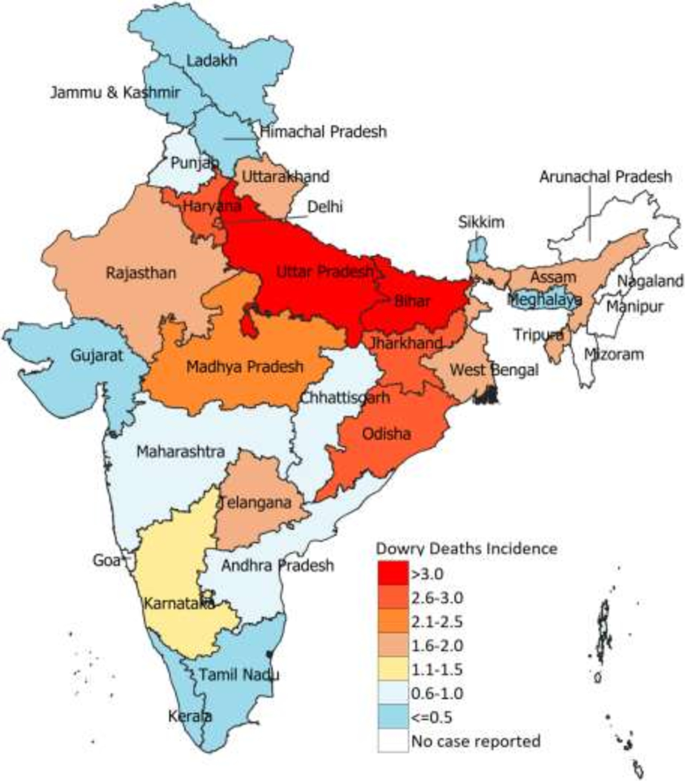

A total of 137,627 crimes were reported as dowry deaths between 2001 and 2018, with 38,342 (27.9%) cases between 2014 and 2018. The rate of this reported crime in India was 2.0 (95% CI 2.5–2.7) in 2018 per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years (Table 1 ). This rate in 2018 was 3.1 (95% CI 3.0–3.2) in the low-SDI states as compared to 1.2 (95% CI 1.1–1) in the middle- and 0.7 (95% CI 0.60–0.8) in the high-SDI states, and this trend was seen throughout the period studied (Table 1 ). At the state level in 2018, this rate ranged from 0.11 (95% CI 0–0.32) in Meghalaya to 4.0 (95% CI 3.8–4.2) in Uttar Pradesh; no cases were reported in Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Mizoram or Nagaland (Table 1 and Fig. 3 ). The largest decline in this rate was seen in the states of Tamil Nadu and Gujarat over the study period (Table 1 ).

Rate of dowry deaths per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years in 2018 in India, by state

The mean number of persons arrested for dowry deaths in India declined from 3 in 2001 to 2.3 in 2018. In 2001, this mean was markedly higher in the high-SDI states (4.9) than the low- (2.7) and middle- (2.6) SDI states. However, by 2015 this rate was higher in the low-SDI states (2.9) than high- (2.2) and middle- (1.8) SDI states (Additional file 5 : Fig. S4).

Abetment of suicide of women

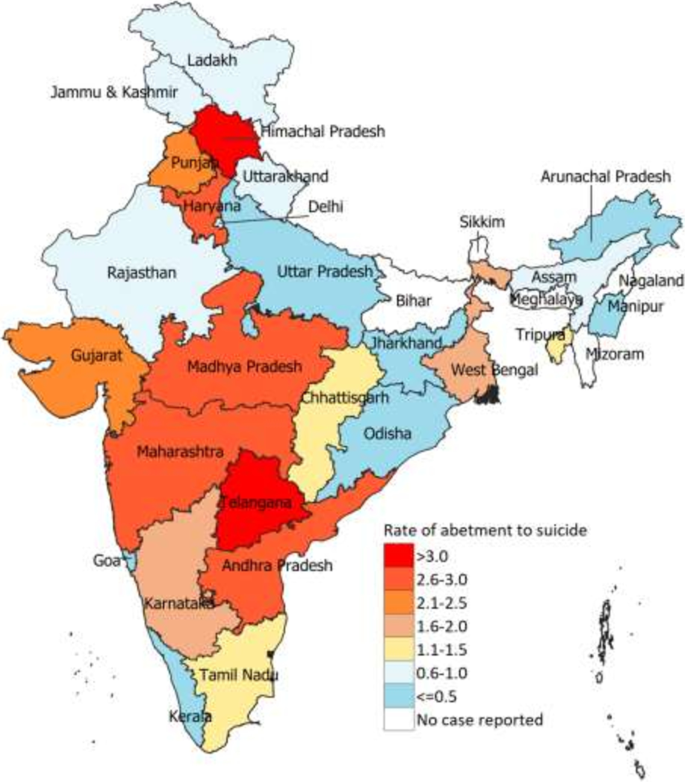

Data under this crime head was available from 2014 to 2018, during which 22,579 cases were reported. The average rate of this crime was 1.27 (95% CI 1.25–1.29) per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years over this period. Overall, relatively higher rates were recorded in middle-SDI states (2.2; 95% CI 2.1–2.3), followed by high- (1.7; 95% CI 1.6–1.8) and low- (0.73; 95% CI 0.69–0.77) SDI states (Table 1 ). Notably, the middle- and high-SDI groups recorded a similar rate in 2014, after which the middle-SDI states recorded a steady increase in rate until 2017, while the high-SDI states saw an initial dip in 2015 and then an increase till 2017. The rate in the low-SDI states remained low throughout this period (Table 1 ).

At the state-level in 2018, this rate ranged from 0.07 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.12) in Odisha to 4.0 (95% CI 3.6–4.4) in Telangana; no cases were reported in Bihar, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Sikkim and Nagaland (Table 1 and Fig. 4 ). While some states did not record any case, other states recorded significant changes between the 2014 and 2018. This rate in Tamil Nadu increased by 450% from 2014 to 2018, and West Bengal and Gujarat recorded an increase of over 100%, while this rate declined the most in Telangana, by 31% (Table 1 ). The mean number of persons arrested for this crime in India recorded a small increase from 1.4 in 2014 to 1.7 in 2018, and was similar across the state SDI groups (Additional file 5 : Fig. S4).

Rate of abetment of suicide of women per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years in 2018 in India, by state

PWDVA, 2005

A total of 2,519 cases were reported under PWDVA between 2014 and 2018, with an average crime rate of 0.14 (95% CI 0.13–0.15) per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years during this period (Table 1 ). Majority of the states did not report any case under this Act (Table 1 ). The mean number of persons arrested in India for this crime decreased from 1.6 in 2014 to 1 in 2018 (Additional file 5 : Fig. S4).

Status of the legal cases

A total of 658,418 cases were sent for trial in India in 2018, of which trial was completed in only 44,648 (6.8%) cases. Among the cases in which trial was completed, the offender(s) was convicted in only 6,921 (15.5%) cases.

In India between 2001 and 2018, the majority of domestic violence cases were filed under ‘cruelty by husband or his relatives’, with the reported rate of this crime increasing by 53% over the 18 years. However, it is important to note that only some states recorded change in the reported rate with the almost stagnant reported rate of domestic violence in many states over time. Significant heterogeneity was seen in the pattern of the four types of crimes at the state-level. Overall, the mean persons arrested decreased irrespective of the crime during the period studied, and less than 7% of the filed cases had completed legal trial in 2018. We discuss the gaps identified in the reported data which unless addressed have major implications in the facilitating action to reduce domestic violence against women in India.

The rate of reported crime under all the considered categories excluding dowry deaths in 2018 in India in the NCRB was close to the 33% self-reported domestic violence reported by women in the national survey in 2015–16 [ 3 ], though there is an indication that the prevalence of domestic violence could be as high as 41% in India [ 4 ]. The NCRB data provides passive surveillance with the source being the FIR filed by family/kin/community member with the police for a crime, and hence is dependent on the reporting from the community, which is known to be selective as women report less to the police for domestic violence due to various reasons including lack of social support, shame, and stigma [ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ]. These differences could account for differential rates of domestic violence between the police records and self-reporting of domestic violence in the surveys [ 3 , 4 ]. Recently, it is also shown that how women are asked about domestic violence in surveys can also result in different estimates [ 38 ]. Furthermore, the Principal Offence Rule followed by NCRB "hides" many cases of domestic violence as according to this Rule, each criminal incident is recorded as one crime. If many offences are registered in a single case, only the most heinous crime—one that attracts maximum punishment—is considered as counting unit [ 39 , 40 ]. For example, an incident involving dowry death and cruelty by husband or relative will be reported in NCRB as dowry death as it warrants the maximum punishment, thereby, underreporting the number of cases with cruelty by husband or relative.

The cases under cruelty by husband or his relatives accounted for the majority of reported cases, and the rate of this reporting was comparatively higher in the middle-SDI states over the years studied. Previous research using field notes from cases reported to police indicate that victims are often in an environment that condones violence through active encouragement or tacit approval by the husband’s family members; and that many women lack social support as they experience violence from multiple perpetrators at home [ 34 , 41 ]. It is plausible that this rate is higher in the middle-SDI states because material wealth is highly prized among the Indian middle class, and dowry is seen as an easy path to greater wealth and social status [ 12 ]. A higher dowry demand, and a greater dissatisfaction from inability to meet these demands could possibly result in more domestic violence in these states [ 12 , 42 , 43 ]. Another possible factor in these states could be that the increasing female literacy in these states may be perceived as a threat to the prevalent power structures, prompting violence against women as a means to reinstate control [ 12 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 ].

The middle-SDI states also had a higher rate of reported cases under abetment to suicide. The link between abuse and suicidal behaviour is well established, with research indicating that three out of ten women who undergo domestic violence are likely to attempt suicide [ 5 ]. Furthermore, a significantly higher suicide death rate is reported in Indian women than their global counterparts [ 9 ], and housewives account for the majority of these suicide deaths [ 10 ]. Wide state-level variations in the suicide death rate for women are also reported [ 9 ], and the relationship between the prevalence of domestic violence and suicide death rate needs to be explored further.

In contrast to the increased reporting of cases of cruelty over time, the rate of dowry death cases decreased from 2001 to 2018, with the low-SDI states recording the highest rate of dowry deaths. The dip in these cases may have resulted from the 2010 judgment requiring prior harassment of the victim associated with a dowry shortfall which made it harder to register a dowry death but presumably also harder to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that it was a dowry death, and not in fact.[ 48 ] Furthermore, qualitative research has shown that the families of dowry death cases deter from accusing the husband or his family due to fear of issues with up-bringing of the children of their daughter [ 47 ]. Also dowry deaths or related suicide deaths are less likely to be reported by the natal family, who fear social stigma and negative impact on marriages of their other daughters [ 42 , 49 ]. In this context, it is not easy to interpret the decreased number of cases of dowry deaths in India as actual fewer dowry deaths, for which more evidence is needed.

Very few cases were filed under PWDVA with the middle-SDI states reporting no cases during the period studied. While PWDVA defines domestic violence to include coercive behaviour as well as physical, sexual, emotional and economic abuse [ 11 ], in actuality only extreme forms of physical violence with evidence of injury are seen to evoke a legal response [ 12 ]. Interviews with victims indicate that unless they were able to offer a dowry claim or show evidence of grave physical violence, the police were either reluctant to file an FIR or offer PWDVA as a legal recourse to them [ 12 ]. It is also documented that the police, acting as social brokers, attempt to fit the reported domestic violence cases into ‘normal constructs’ frequently focusing on dowry harassment despite the broadened scope of the law as a recourse for domestic violence beyond dowry harassment [ 5 ]. Thus, data under this crime heading is unlikely to reflect the true picture of domestic violence against women in India.

The poor response of formal system to domestic violence is also reflected in the legal recourse as only 6.8% of the cases filed completed trials in 2018, with the majority of accused being acquitted. This bleak state of waiting, extended trials and low conviction is known to further discourage women from reporting [ 50 ]. The legal process is also influenced by the patriarchy driven attitudes of the police and people in the legal systems [ 44 ], and their unwillingness to act on domestic violence cases which they view as “private matter,”[ 13 , 44 ] such that many cases are not investigated, or dropped due to delay in filing [ 5 ]. In other cases, the investigation is based on the statement of the husband or relatives rather than fingerprints [ 13 ], with the perpetrator of violence not even recorded in over 90% of the cases [ 5 ]. Notably, little empirical research is available on the perceptions of abusive husbands and families on domestic violence that can facilitate intervention programs for abusive husbands [ 34 ].

Limitations and way forward

There are limitations to the data presented and the interpretation. The NCRB data depend on the availability and quality of data recorded by the police at the local level, which is known to have varied quality [ 9 , 10 , 18 ]. The findings have to be interpreted within in this limitation as it is not possible for us to comment on the extent of underreporting of data or the pattern of underreporting by type of crime, year or state. The heterogeneity in the NCRB data at the state level highlighted by the noisy trends or stagnant trend for certain states do not allow for a meaningful interpretation, and calls for a robust assessment of the reporting practices by the police and judiciary at state level to identify the gaps for inadequate documentation and underreporting that can facilitate appropriate corrective measures to improve data quality [ 18 ]. We assumed the age group of affected women to be 15–49 years. Though majority of the cases are likely to be in this age group given the other available information, the unavailability of age of women affected by the type of crime, year and state restricts understanding of the target women for prevention and action. Currently, the data are available in heavily tabulated fixed formats that limit the extent of disaggregated analysis. Because of non-availability of data on number of victims for some years, we assumed the ratio of the number of cases to victims based on the available data for other years. More informative analyses may also be possible if the NCRB reports allow for anonymized individual level data to be available in the public domain, including repeat reports of domestic violence by individual women.

Despite NCRB being a passive surveillance source, efforts can be made to improve the quality of information collected by the police during their routine tasks to improve utilisation of these data for planning action. The World Health Organization injury surveillance guidelines could provide practical advice on collecting systematic data on domestic violence, which can be more comparable over time and location [ 51 ]. Training and sensitisation of the police to address gender violence should also include standardisations in capturing of the data and the quality of data captured.

Disasters, natural or otherwise, disproportionately impact women and girls with some evidence suggesting that violence against women increases in disaster settings, however, there is a lack of rigorously designed and good quality studies that are needed to inform evidence-based policies and safeguard women and girls during and after disasters [ 52 ]. There has also been suggestion of an increase in domestic violence against women during the Covid-19 pandemic, globally [ 53 ] and in India [ 54 , 55 ]. In this context, the urgency to address the gaps highlighted in the NCRB data is even more for India to protect its women against domestic violence.

India needs to address the gaps in the administrative data to effectively respond to the SDG target five to eliminate all forms of violence against women. This longitudual analysis of the reported cases of domestic violence of nearly 20 years across the Indian states has highlighted the under-reporting and almost stagnant data, which hinders formulating of well-informed public health intervention strategies to reduce domestic violence in India.

Availability of data and materials

The domestic violence related data used in these analyses are available at NCRB website ( https://ncrb.gov.in ) and from the authors on request. The GBD population data used in these analyses are available at GBD Results Tool | GHDx (healthdata.org).

Abbreviations

Confidence interval

First information report

Global burden of disease

Indian penal code

National Crimes Records Bureau

National Family Health Survey

Protection of women from domestic violence act

Quantum geographic information system

Sustainable development goal

Socio-demographic index

World Health Organization

United Nations: Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; 2015.

World Health Organization. Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. Geneva: WHO; 2021.

Google Scholar

National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16. http://www.rchiips.org/nfhs .

Kalokhe A, Del Rio C, Dunkle K, Stephenson R, Metheny N, Paranjape A, Sahay S. Domestic violence against women in India: A systematic review of a decade of quantitative studies. Glob Public Health. 2017;12(4):498–513.

Article Google Scholar

International Center for Research on Women: Domestic Violence in India 2: a Summary Report of Four Records Studies. ICRW; 2000.

International Center for Research on Women: Domestic Violence in India 3: a Summary Report of a Multi-Site Household Survey. ICRW; 2000.

International Center for Research on Women.: Domestic Violence in India 1: a Summary Report of Three Studies. ICRW; 1999.

International Center for Research on Women.: Domestic violence in India, part 4. ICRW passion, proof, power. ICRW; 2002.

India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Suicide Collaborators. Gender differentials and state variations in suicide deaths in India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(10):e478–89.

Dandona R, Bertozzi-Villa A, Kumar GA, Dandona L. Lessons from a decade of suicide surveillance in India: who, why and how? Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):983–93.

PubMed Google Scholar

Government of India: Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005. In: 2005.

Sundari AYH, Roy A. Changing nature and emerging patterns of domestic violence in global contexts: Dowry abuse and the transnational abandonment of wives in India. Women’s Stud Int Forum. 2018;69:67–75.

Ravikant NS. Dowry deaths: proposing a standard for implementation of domestic legislation in accordance with human rights obligations. Mich J Gender Law. 2000;6(2):449.

Lolayekar AP, Desouza S, Mukhopadhyay P. Crimes Against Women in India: A District-Level Analysis (1991–2011). J Interpers Violence 2020:886260520967147.

The Woman Stat’s Project. Dowry, Bride Price and Wedding Costs. http://www.womanstats.org/vlbMAPS/images1/brideprice_dowry_wedding_costs_2correct.jpg .

Marriage Markets and the Rise of Dowry in India. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3590730

National Crime Records Bureau. http://ncrb.gov.in/ .

Raban MZ, Dandona L, Dandona R. The quality of police data on RTC fatalities in India. Injury Prev J Int Soc Child Adolescent Injury Prev. 2014;20(5):293–301.

Frequently asked questions about filing an FIR in India. http://www.fixindia.org/fir.php#1

First Information Report and You. https://www.humanrightsinitiative.org/publications/police/fir.pdf .

Government of India: Act No. 46 of 1983, Section 498a. http://www.498a.org/contents/amendments/Act%2046%20of%201983.pdf .

Government of India: Act No. 43 of 1986. Section 304B. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?actid=AC_CEN_5_23_00037_186045_1523266765688&orderno=342 .

Government of India.: Section 306. Abetment of Suicide. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?actid=AC_CEN_5_23_00037_186045_1523266765688&orderno=344

Crime in India. http://nrcb.gov.in .

Ram A, Victor CP, Christy H, Hembrom S, Cherian AG, Mohan VR. Domestic Violence and its Determinants among 15–49-Year-Old Women in a Rural Block in South India. Indian J Community Med. 2019;44(4):362–7.

Nadda A, Malik JS, Bhardwaj AA, Khan ZA, Arora V, Gupta S, Nagar M. Reciprocate and nonreciprocate spousal violence: a cross-sectional study in Haryana, India. J Family Med Primary Care. 2019;8(1):120–4.

Bhattacharya A, Yasmin S, Bhattacharya A, Baur B, Madhwani KP. Domestic violence against women: A hidden and deeply rooted health issue in India. J Family Med Primary Care. 2020;9(10):5229–35.

Leonardsson M, Sebastian M. Prevalence and predictors of help-seeking for women exposed to spousal violence in India—a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17(1):99.

George J, Nair D, Premkumar NR, Saravanan N, Chinnakali P, Roy G. The prevalence of domestic violence and its associated factors among married women in a rural area of Puducherry, South India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016;5(3):672–6.

Bondade S, Iyengar RS, Shivakumar BK, Karthik KN. Intimate partner violence and psychiatric comorbidity in infertile women—a cross-sectional hospital based study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2018;40(6):540–6.

Raj A, Saggurti N, Lawrence D, Balaiah D, Silverman JG. Association between adolescent marriage and marital violence among young adult women in India. Int J Gynaecol Obstetr. 2010;110(1):35–9.

India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Collaborators. Nations within a nation: variations in epidemiological transition across the states of India, 1990–2016 in the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet (London, England). 2017;390(10111):2437–60.

QGIS Geographic Information System: Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. http://qgis.org .

Bhat M, Ullman SE: Examining marital violence in India: review and recommendations for future research and practice. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2014;15(1):57–74.

Chowdhary NPV. The effect of spousal violence on women’s health: findings from the Stree Arogya Shodh in Goa, India. J Postgrad Med. 2008;54(4):306–12.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Burton B, Duvvury N, Rajan A, Varia N. (2000). Health records and domestic violence in Thane district Maharashtra [by] Surinder Jaswal. Summary report.

Johnson PS, Johnson JA. The oppression of women in India. Violence Against Women. 2001;7:1051–1068.

Cullen C. Method matters: underreporting of intimate partner violence in Nigeria and Rwanda. In: Open Knowledge Repository; 2020.

Aebi MF. Measuring the influence of statistical counting rules on cross-national differences in recorded crime. In: Shoham SG, Beck O, Kett M editors. International Handbook of Criminology. Boca Raton; 2010: 211–227.

Dutta PK. NCRB 2018: Have Indians become less criminal, more civilised? https://www.indiatoday.in/news-analysis/story/ncrb-2018-data-have-indians-become-less-criminal-more-civilised-1635601-2020-01-10

Burton B, Duvvury N, Rajan A, Varia N. (2000). Special Cell for Women and Children: a research study on domestic violence [by] Anjali Dave and Gopika Solanki. Summary report.

Lolayekar AP, Desouza S, Mukhopadhyay P. Crimes against women in India: a district-level analysis (1991–2011). J Interpers Violence 2020; 0886260520967147.

Pallikadavath S, Bradley T. Dowry, dowry autonomy and domestic violence among young married women in India. J Biosoc Sci. 2019;51(3):353–73.

Menon SV, Allen NE. The formal systems response to violence against women in India: a cultural lens. Am J Community Psychol. 2018;62(1–2):51–61.

Nanda P, Gautam A, Verma R, Khanna A, Khan, Brahme D, Boyle S, Kumar S: Study on masculinity, intimate partner violence and son preference in India. In: New Delhi: International Center for Research on Women; 2014.

Bhagat RB. The practice of early marriages among females in India: Persistence and change. In: Mumbai, India: IIPS; 2016.

Jeyaseelan V, Kumar S, Jeyaseelan L, Shankar V, Yadav BK, Bangdiwala SI. Dowry demand and harassment: prevalence and risk factors in India. J Biosoc Sci. 2015;47(6):727–45.

Dang G KV, Gaiha R. Why dowry deaths have risen in India. In: ASARC Working Paper. Brisbane: The Australian National University; 2018.

Belur JTN, Osrin D, Daruwalla N, Kumar M, Tiwari V. Police investigations: discretion denied yet undeniably exercised. Policing Soc. 2014;25(5):439–62.

Conviction Rate for Crimes Against Women Hits Record Low. https://thewire.in/gender/conviction-rate-crimes-women-hits-record-low .

World Health Organization. Injury surveillance guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

Thurston AM, Stöckl H, Ranganathan M. Natural hazards, disasters and violence against women and girls: a global mixed-methods systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(4):10.

Sediri S, Zgueb Y, Ouanes S, Ouali U, Bourgou S, Jomli R, Nacef F. Women’s mental health: acute impact of COVID-19 pandemic on domestic violence. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2020;23(6):749–56.

Indu PV, Vijayan B, Tharayil HM, Ayirolimeethal A, Vidyadharan V. Domestic violence and psychological problems in married women during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: a community-based survey. Asian J Psychiatry. 2021;64:102812.

Iyengar J, Upadhyay AK. Despite the known negative health impact of VAWG, India fails to protect women from the shadow pandemic. Asian J Psychiatry. 2022;67:102958.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Amit Kumar Chetty and Parijat Singh for help with downloading and formatting of the data.

This work was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation [INV-004506]. Under the grant conditions of the Foundation, a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Generic License has already been assigned to the Author Accepted Manuscript version that might arise from this submission

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Public Health Foundation of India, Plot No. 47, Sector 44, Institutional Area, Gurugram, Haryana, 122002, India

Rakhi Dandona, Aradhita Gupta, Sibin George, Somy Kishan & G. Anil Kumar

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, USA

Rakhi Dandona

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

RD and GAK conceptualised this paper. RD drafted the manuscript with contributions from AG and GAK. SG, SK and GAK performed data analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation and agreed with the final version of the paper. RD and GAK had full access to all the data in the study and had the final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All authors had access to the estimates presented in the paper. RD and GAK verified the data underlying this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rakhi Dandona .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The analysis is presented on secondary administrative data available in public domain which does not require consent to participate or ethics approval. All human data are reported in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

. Definitions of crime headings considered under domestic violence. IPC denotes Indian Penal Code.

Additional file 2

. Crime rate for cruelty by husband or his relatives per 100,000 women aged 15-49 years in the Indian states categorised as having low Socio-demographic Index, 2001-18.

Additional file 3.

Crime rate for cruelty by husband or his relatives per 100,000 women aged 15-49 years in the Indian states categorised as having middle Socio-demographic Index, 2001-18. Telangana state not shown as it was formed in 2014.

Additional file 4.

Crime rate for cruelty by husband or his relatives per 100,000 women aged 15-49 years in the Indian states categorised as having high Socio-demographic Index, 2001-18.

Additional file 5.

Mean numbers of persons arrested under cruelty by husband or his relatives and dowry deaths for the years 2001-2018, and under abetment of suicide of women and PWDVA for the years 2014-2018. SDI denotes Socio-demographic Index. The state wise data for mean number of persons arrested was available until 2015 only.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Dandona, R., Gupta, A., George, S. et al. Domestic violence in Indian women: lessons from nearly 20 years of surveillance. BMC Women's Health 22 , 128 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01703-3

Download citation

Received : 07 October 2021

Accepted : 07 April 2022

Published : 21 April 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01703-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Domestic violence

- Intimate partner

BMC Women's Health

ISSN: 1472-6874

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

A global study into indian women’s experiences of domestic violence and control: the role of patriarchal beliefs.

- School of Psychology, Deakin University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Domestic violence (DV) is a serious and preventable human rights issue that disproportionately affects certain groups of people, including Indian women. Feminist theory suggests that patriarchal ideologies produce an entitlement in male perpetrators of DV; however, this has not been examined in the context of women from the Indian subcontinent. This study examined Indian women’s experiences of abuse (physical, sexual, and psychological) and controlling behavior across 31 countries by examining the relationship between the patriarchal beliefs held by the women’s partners and the women’s experience of DV. This study uses an intersectional feminist framework to examine the variables. Data from an online questionnaire was collected from 825 Indian women aged between 18 and 77 years ( M = 35.64, SD = 8.71) living in 31 countries across Asia (37.1%), Europe (18.3%), Oceania (23.8%), the Americas (16.1%) and Africa (3.2%) and analyzed using a hierarchical linear regression. A majority of participants (72.5%) had experienced at least one form of abuse during their relationship, and over a third (35.1%) had experienced controlling behavior. In support of the central hypotheses, after controlling for potential confounders, women whose partners showed greater endorsement of patriarchal beliefs were less likely to have access to freedom during their relationship ( ß = −0.38, p < 0.001) and were more likely to have been abused by their partner or a member of his family ( ß = 0.34, p < 0.001). The findings of this study highlight the need to engage with men in Indian communities through culturally-tailored intervention strategies designed to challenge the patriarchal ideologies that propagate, justify, and excuse DV.

Introduction

Domestic violence (DV) is the most common form of violence against women, and occurs in every country around the world, transgressing social, economic, religious, and cultural divides ( García-Moreno et al., 2005 ; Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018 ). Although men can be abused by female partners and violence also occurs in non-heterosexual relationships, the vast majority of DV victims are women, and their perpetrators are a current or former male partner ( World Health Organization, 2019 ). In the context of this study, DV includes physical, sexual abuse, or emotional abuse and controlling behaviors such as enforced isolation, excessive jealousy, and limiting access to economic resources or support ( Our Watch, 2015 ; World Health Organization, 2019 ). In research, the terms, domestic violence, intimate partner violence, family violence, sexual violence and spousal abuse are used interchangeably. For the purposes of the present study, ‘domestic violence’ is used to refer to the violence women experience from their current or former intimate partner.

In addition to representing the leading cause of death for women around the world, with more than 50,000 women being killed by a partner or family member each year ( UNODC, 2018 ), the physical, psychological, and social effects of DV are profound and enduring. Along with physical injuries, women who have been subjected to DV report higher rates of depression, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, cognitive impairment, substance abuse, and are more likely to have thought about or attempted suicide ( Ellsberg et al., 2008 ; Chandra et al., 2009 ). They are also at a heightened risk of experiencing sexually-transmitted infections, gynecological problems, unwanted pregnancies, and miscarriages ( Ellsberg et al., 2008 ; Stephenson et al., 2008 ; Dalal and Lindqvist, 2010 ). Moreover, violence in the home places women at significant risk of homelessness, unemployment, and poverty ( Specialist homelessness services annual report, Summary, 2021 ). Although some men also experience violence from their female partners, prevalence rates from across the world show that women experience violence at three times a greater rate than men; the risk factors for men and women could also vary and therefore, these need to be clearly delineated for each group. Given the deleterious outcomes associated with DV, understanding the factors that drive it is vital in research, policy, as well as in clinical practice ( Ellsberg et al., 2008 ).

A landmark study by the WHO which collected data from over 24,000 women in 10 countries about the extent of domestic violence they experienced found that depending on country and context (e.g., rural versus urban locations), between 15 and 71% of women had been physically or sexually assaulted by an intimate partner during their lifetime ( García-Moreno et al., 2005 ). These findings raise three pertinent points: first, that the apparent universality of DV confirms that its occurrence is not a random aberration, but instead a reflection of gender inequalities that are deeply entrenched and systemically enacted in many cultures and societies around the world. Second, that in addition to gender, factors such as socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and immigration status intersect with gender to shape women’s experiences of abuse. Third, that high rates of violence against women are not inevitable, nor intractable, and therefore should be the aim of global prevention efforts. In sum, it is clear that the harmful effects of DV are universal, but not experienced by all women equally. As such, identifying how diverse groups of women experience DV in their particular cultural context is essential for designing culturally relevant interventions for both victims and perpetrators ( Bhuyan and Senturia, 2005 ). Studies have shown that the experiences of migrant and refugee women can vary significantly to their non-migrant counterparts, therefore, we need a clearer understanding of the nuances of these differences and the impacts of their experiences.

Indian women are one group of women that remain at high risk of DV with or without migration from India ( Natarajan, 2002 ; Ahmed-Ghosh, 2004 ; Bhuyan and Senturia, 2005 ) compared to women from Europe, the Western Pacific or North America ( Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018 ). However, the largely Western-centric feminist discourse surrounding DV means there is a dearth of Indian-specific research. In addition, common methodological limitations such as the lack of psychometrically-validated, culturally-appropriate DV measurement tools, small and single-location sample sizes, and a failure to recognize forms of abuse other than physical abuse means that the voices of Indian women remain both under-and mis-represented in the extant literature ( Yoshihama, 2001 ; Kalokhe et al., 2016 ).

While much progress has been made toward gender equality in India ( Bhatia, 2012 ), the prevalence of DV is high. Data from the 2015–2016 Indian National Family Health Survey indicated that 33% of the 67,000 women surveyed in India had experienced DV during their marriage, with the most common type being physical violence (30%), followed by emotional (14%) and sexual violence (7%) ( National Family Health Survey, 2017 ). A recent systematic review of 137 quantitative studies examining DV in India by Kalokhe and colleagues ( Kalokhe et al., 2016 ) also found high rates of these types of violence along with a 41% prevalence of multiple types of abuse. The impact of physical, sexual, and psychological abuse on women’s mental, physical, sexual, and reproductive health is severe and leads to greater levels of depression, suicide attempts, post-traumatic stress disorder, and somatic symptoms and a decreased quality of life ( Kalokhe et al., 2016 ). Research also shows that Indian women who have migrated from India to the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada experience higher rates of DV than the general population ( Raj and Silverman, 2002 ; Ahmad et al., 2004 ; Mahapatra, 2012 ). Little is known about the DV rates among Indian women who migrate to other countries. Taken together, these findings suggest that Indian women across the globe experience high rates of DV. As such, it is important to understand the sociocultural factors that contribute to its occurrence.

While there is no single cause of DV, feminist theories emphasize how the circulation and espousal of patriarchal ideologies in society contribute to, create, and maintain DV ( Pagelow, 1981 ; Smith, 1990 ). Although variously defined, patriarchy refers to the hierarchical system of social power arrangements that affords men more power and privilege than women, both structurally and ideologically ( Smith, 1990 ; Hunnicutt, 2009 ) with the origins of the word ‘patriarchy’ coming from the Greek word Πατριάρχης ( patriakh͞es ), meaning male chief or head of a family.

According to an ecological framework ( Heise, 1998 ), patriarchal control, exploitation and oppression of women occurs within all levels of social ecology, including the macrosystem (e.g., government, laws, culture), mesosystem (e.g., the media, workplaces), microsystem (e.g., families and relationships), and at the level of the individual. Through social learning, patriarchal structures are internalized as patriarchal ideologies, which are a set of beliefs that legitimize and justify the expression of male power and authority over women, including DV ( Smith, 1990 ; Yoon et al., 2015 ). More specifically, patriarchal beliefs include notions about the inherent inferiority of women and girls, men’s right to control decision-making in both public and private spheres, traditional and proscriptive gender roles, and the condoning of violence against women ( Our Watch, 2015 ; Yoon et al., 2015 ). Such ideologies preserve and strengthen the structural gender inequalities that set the necessary social context for DV to occur, by giving men the cultural, legal, and social mandate to use varying degrees of violence and control against women ( Our Watch, 2015 ; Yoon et al., 2015 ; World Health Organization, 2019 ).

Research from the United States indicates that positive attitudes toward violence against women and beliefs in traditional gender roles is associated with perpetration of DV ( Sugarman and Frankel, 1996 ; Stith et al., 2004 ). Similarly, Hah-Yahia ( Haj-Yahia, 2005 ) found that Jordanian men who subscribed to patriarchal ideologies were more likely to justify DV, blame women for violence against them, believe that women benefit from beating, and believe that men should not be punished for hurting their wives. Furthermore, a study of South Asian women living in the United States found that women who endorsed patriarchal beliefs were more likely to have experienced DV ( Adam and Schewe, 2007 ), and men in Pakistan who adhered to patriarchal ideology were more likely to use physical violence against their partners ( Adam and Schewe, 2007 ).

Despite its clear theoretical underpinnings, the relationship between patriarchal beliefs as a single construct and DV perpetration in Indian communities has, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, not been quantitatively examined. This is important, as although patriarchy is omnipresent in all societies on earth, culture shapes its manifestation through values, norms, beliefs, traditions, and familial roles that perpetuate patriarchal structures and ideologies ( Duncan, 2002 ).

In Indian families, power and authority is transmitted from father to the eldest son, meaning that females are expected to be subservient to males throughout their lifetimes; in childhood, to their fathers; upon marriage, to their husbands; and in old age (on occasion of the death of their husband), to their sons ( Bhuyan and Senturia, 2005 ). The impact of a father’s violence on children’s development can last a long time. Research suggests that the effects of this violence against girls in childhood are much more serious and deleterious than the effects of violence used by other men, or even a mother, against women such that women who suffer violence by their father have low levels of resilience in adulthood – even though they might report other perpetrators (such as the husband) as committing greater violence ( Tsirigotis and Łuczak, 2018 ). Therefore, women, as adults, can continue to be affected by patriarchal behaviors of men. In the Indian context, historically too, the hierarchy between men and women prevailed. For example, in ancient India, Smriti, Kautilya, and Manu philosophers demanded total subservience of women to their husbands ( Kumar, 2017 ). In spite of advances in society about gender equality and gender roles, such attitudes still exist in India. For instance, the Indian National Family Health Survey found that less than two-thirds, that is, 63% of married women participated in decision-making about major household matters, and less than 41% were allowed to go to places such as the market, a health facility, or visit relatives alone ( National Family Health Survey, 2017 ).

Prescriptive gender roles contribute to the incidence of domestic violence by positioning women as subordinate, with men therefore tasked with ‘protecting’ women and ensuring they uphold the gendered expectations and moral standards imposed on them ( Haj-Yahia, 2005 ; Satyen, 2021 ). Indeed, physical violence is viewed as a common and acceptable response to women’s “disobedience,” or failure to meet her husband’s expectations ( Jejeebhoy and Cook, 1997 ). For example, 42% of men and 52% of women believed that a husband is justified in beating his wife if she goes outside without telling him, neglects the house, argues with him, refuses to have sex, does not cook properly, is suspected of being unfaithful, or is disrespectful. This demonstrates that women have possibly internalized their “inferior” status in society and are more accepting of the inequality they face in the household. Honor killings, where women are killed by male family members for bringing shame to their families, still occurs in India and may represent the most extreme example of such attitudes ( Kumar and Gupta, 2022 ).

Taken together, the aforementioned findings clearly outline the broad links between DV and elements of patriarchal ideology including ideas about the inherent inferiority of women, men’s right to control decision-making, traditional gender roles, and condoning of violence against women ( Our Watch, 2015 ; Yoon et al., 2015 ). However, lacking from this literature is a culturally-specific, comprehensive assessment of the role of individual-level patriarchal beliefs in influencing Indian women’s experiences of DV. Understanding this relationship is vital in order to develop culturally tailored DV interventions and policies.

While cultural expressions of patriarchy provide the necessary context for DV to occur, according to intersectionality theory ( Kumar and Gupta, 2022 ), gender oppression intersects with other forms of inequality, such as poverty, racism, and migration status to increase the risk of DV for certain groups of Indian women ( Sokoloff and Dupont, 2005 ). For example, those who are younger, have more children, live in rural locations, have fewer years of schooling, or who are unemployed are more likely to experience DV during their lifetime ( Sokoloff and Dupont, 2005 ), and may be less likely to seek help for DV ( Leonardsson and San, 2017 ). Furthermore, migration has been identified as a key risk factor for DV ( Satyen et al., 2018 ; UNODC, 2018 ; Satyen, 2021 ), through practical and cultural barriers to accessing help and support ( Raj and Silverman, 2002 ; Colucci et al., 2013 ), as well as so-called ‘backlash’ factors, whereby men increase their use of violence and control following migration to more egalitarian locations, in response to the threatened loss of status and authority ( Dasgupta and Warrier, 1996 ; Zavala and Spohn, 2010 ). In examining DV, it is therefore important to acknowledge the compounding effects of such factors, while underscoring the central role of patriarchy ( Gundappa and Rathod, 2012 ).

The objective of this study was to examine Indian women’s experiences of abuse (physical, sexual, and psychological) and controlling behavior across 31 countries by examining the relationship between the patriarchal beliefs held by the women’s partners and the women’s experience of DV. Given our understanding of how patriarchal beliefs relate to DV, it was hypothesized that a greater endorsement of patriarchal beliefs by a woman’s partner would predict greater occurrence of abuse and controlling behavior during their relationship.

Research design

We examined the relationship between women’s partners’ patriarchal beliefs (as reported by the women) and the women’s experiences of DV using an intersectional feminist lens. This study used a quantitative, cross-sectional design using an online survey, which explored the impact of partners’ patriarchal beliefs on Indian women’s experiences of DV. The inclusion criteria for partaking in the study included: women who identified culturally as belonging to or having origins in the Indian sub-continent. They needed to have been in the past or currently be in an intimate partner relationship. They could be living in the Indian sub-continent or have migrated elsewhere in the world. They needed to also be 18 years and over to take part in the study and have minimal English language skills to comprehend the questionnaires.

Participants

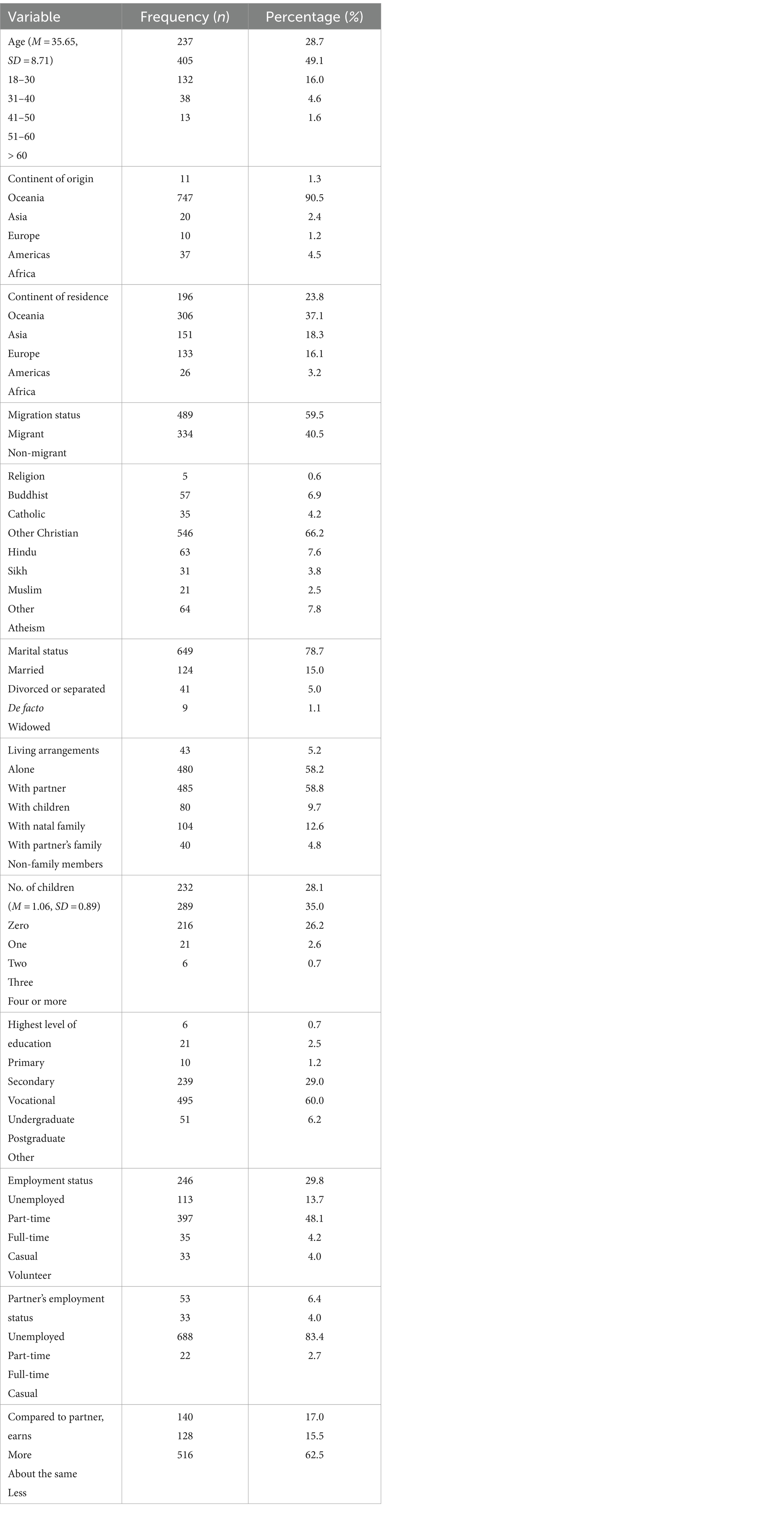

Participants for this study were recruited from across the world via social media and culturally relevant organizations. Through targeted recruitment, Indian women 18 years or over who were currently in or had previously been in an intimate relationship with a male were asked to participate in the study. In addition to recruiting from India and Australia, data from the Government of India’s Ministry of External Affairs ( Population of Overseas Indians, 2018 ) was used to identify the 15 countries with the highest population of people of Indian origin and these were targeted for recruitment in addition to promoting the study across other countries. Target countries included: the United States, United Arab Emirates, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Myanmar, the United Kingdom, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Pakistan, Canada, Kuwait, Mauritius, Qatar, Oman and Singapore. In total, 349 organizations and community groups were contacted by email and provided details of the study. Further, A Facebook page was set up for the project, and a recruitment advertisement was posted to 1,167 public groups relating to Indian women’s interests. In all, 825 participants aged between 18 and 77 years ( M = 35.64, SD = 8.71) from 31 countries across Asia (37.1%), Europe (18.3%), Oceania (23.8%), the Americas (16.1%) and Africa (3.2%) took part. The majority of them were born in India ( n = 720, 87.3%), but 59.3% had migrated from their country (India or other) of birth. See Table 1 for a detailed summary of their demographic characteristics.

Table 1 . Demographic characteristics of the sample ( N = 825).

Participants completed an online questionnaire that assessed demographic information, their experiences of domestic violence, and their partners’ patriarchal beliefs.

Demographic information

Participants’ age, country of birth, country of residence, migration status, religion, marital status, and educational attainment were collected.

Domestic violence

Experiences of abuse including physical, sexual, and psychological and controlling behaviors perpetrated by women’s partners and/or his family members were measured using the 63-item Indian Family Violence and Control Scale [IFVCS; ( National Family Health Survey, 2017 )]. The IFVCS was designed for use in the Indian population, with items being derived from informant and expert interviews with an Indian sample to ensure it captured culturally-specific forms of DV ( Kalokhe et al., 2015 , 2016 ). Preliminary validation of the IFVCS suggested that the scale has strong internal consistency, and good concurrent and construct validity ( Kalokhe et al., 2016 ). Cronbach’s alphas were calculated for the current sample, indicating that both the control and abuse subscales had very good internal reliability (0.94 and 0.97 respectively).

The control subscale consisted of 14 items which asked women to rate their access to various freedoms during their entire relationship (e.g., “freedom to spend my own money on personal things”) on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 ( never ), to 3 ( often ). Total scores for this subscale ranged from 0 to 42, with lower scores indicating lower access to freedom, or more frequent controlling behavior. The 49-item abuse subscale comprised of statements relevant to psychological (22 items), physical (16 items), and sexual violence (11 items) domains and asked women about the frequency of abusive behaviors (e.g., “burnt me or threatened to burn me with a cigarette”) on a 4-point scale, from 0 ( never ) to 3 ( about once a month ). Higher scores indicated greater frequency of abuse, with the total possible abuse score ranging from 0 to147.

Partner’s patriarchal beliefs

Women’s partner’s patriarchal beliefs were measured using 10 items derived from the 5-item Husband’s Patriarchal Beliefs Scale, which was originally developed by Smith (1990) and later adapted by Ahmed-Ghosh (2004) , with the addition of 5 items from the 37-item Patriarchal Beliefs Scale ( Yoon et al., 2015 ). The 10 resultant items captured each of the core dimensions of patriarchal ideology identified by Yoon ( Yoon et al., 2015 ); these include beliefs about the institutional power of men, the inherent inferiority of women, and gendered domestic roles. The scale asked women to rate their perception of their partner’s level of agreement to various patriarchal beliefs (e.g., “men are inherently smarter than women”) on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 ( strongly agree ). Scores ranged from 10 to 70, with higher scores indicating greater endorsement of patriarchal ideology. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated as.96, indicating this new scale had very high internal consistency.

This study was guided by the WHO’s ethical and safety recommendations for DV research ( Ellsberg and Heise, 2002 ) and received approval from the institutional ethics committee in compliance with American Psychological Association (2017) ethical standards ( American Psychological Association, 2017 ). All persons who saw an advertisement or accessed the online link received a plain language statement, as well as information about DV support services in their country, regardless of whether or not they completed the survey. To protect the safety of participants, a Quick Escape button was programmed into the survey. The survey (in English) was anonymous and took approximately 20 min to complete.

Data screening and cleaning

Data cleaning was conducted prior to analysis. Cases missing more than 50% of their data were removed from the sample. For the remaining cases, random missing values were replaced with the series mean. All items across the three abuse subscales, and the control subscale of the IFVCS were summed to obtain a total abuse, and total control score, respectively. For the purposes of regression analyses, employment was dichotomised as employed versus not employed, and education as tertiary education versus non-tertiary education. Each nominal independent variable was treated as a set of dummy variables, with one variable serving as the reference group. For the regression analyses, only women who had reported some form of abuse were included in the analysis; thus, the 15.9% of the sample that reported no abuse were excluded from the analyses.

Analytical strategy

First, descriptive analyses were undertaken to determine the extent of DV and partners’ patriarchal beliefs in the sample and these are presented in Table 2 . As control and abuse were measured on different scales, two hierarchical multiple regression analyses (as seen in Table 3 ) were conducted to test the central hypothesis. For each regression analysis, a three-stage hierarchical regression, and bottom-up model building strategy was used. In model 1, a univariate model including patriarchal beliefs, and either abuse or control as the outcome measure was tested. This provided a baseline estimation of the variance in abuse or control predicted by patriarchal beliefs, enabling estimation of the contribution of the variables added hierarchically in subsequent models. In Model 2, demographic variables (age, marital status, educational attainment, employment status, migration status, and continent of residence) identified in the literature review as potential confounders were entered into the model; all demographic variables were entered into the model together. Two-way interaction effects between patriarchal beliefs and each of the demographic characteristics were examined to exclude potential moderation effects.

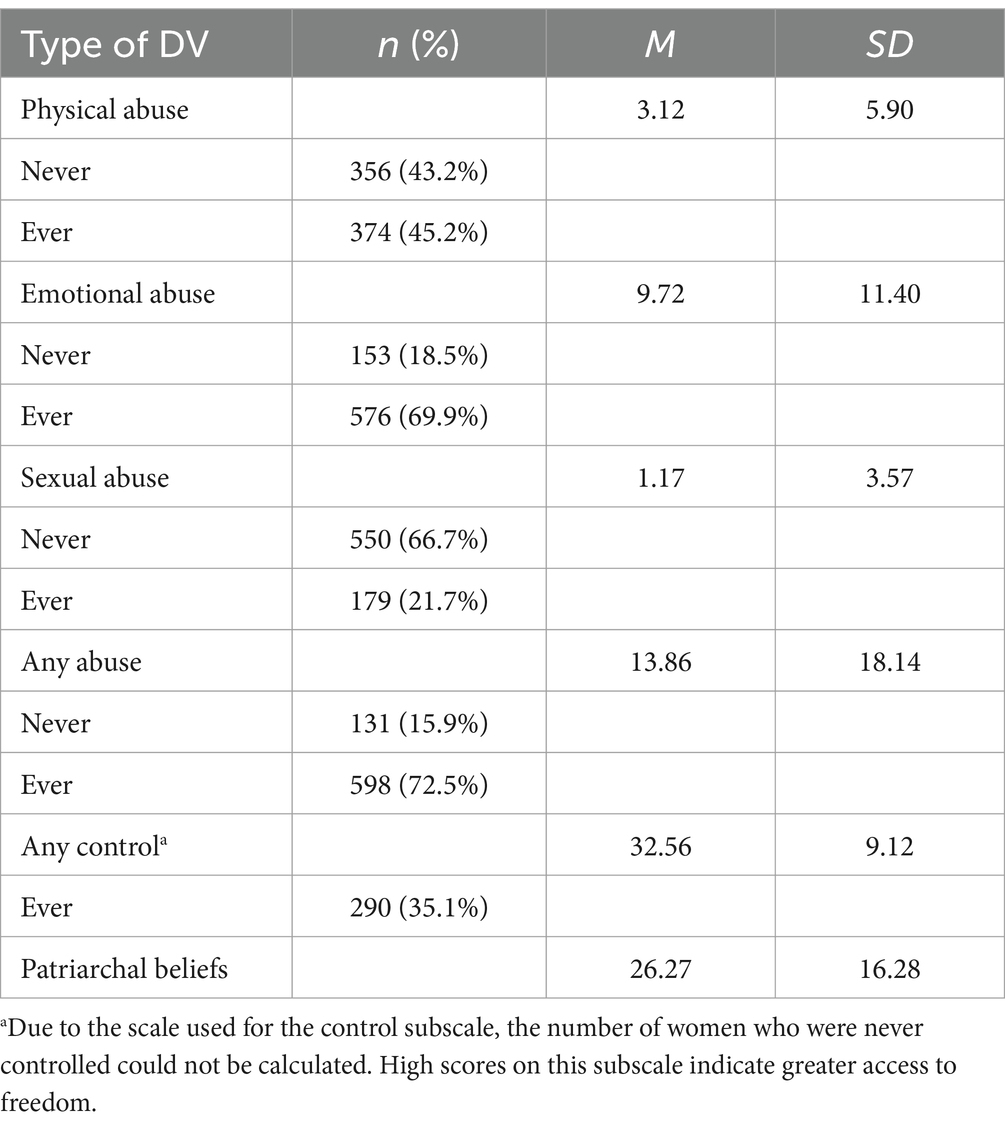

Table 2 . Descriptive statistics for abuse ( N = 729), control ( N = 825) and partners’ patriarchal beliefs ( N = 729).

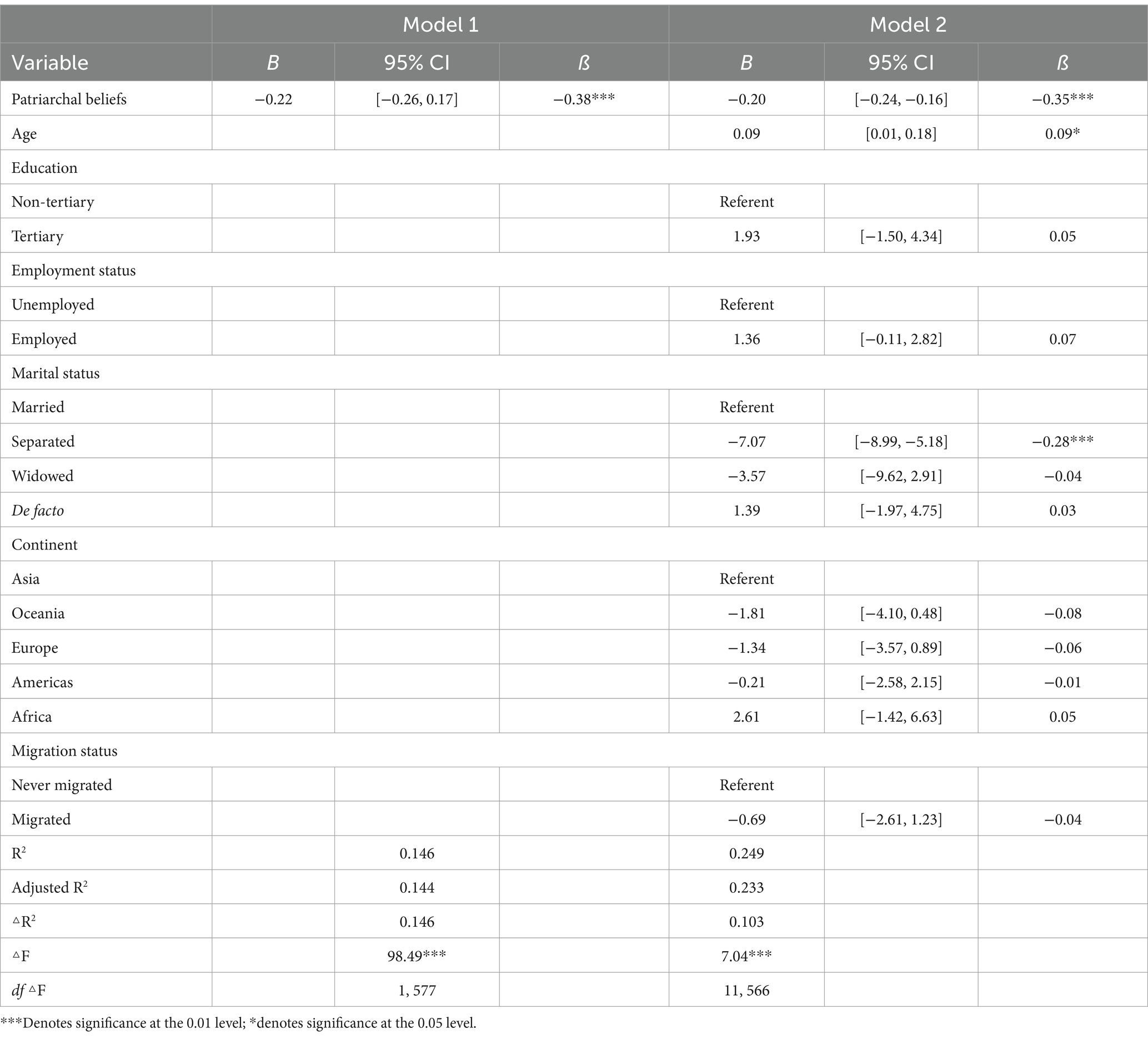

Table 3 . Summary of hierarchical regression analysis for variables predicting control ( N = 579).

Descriptive analyses

Abuse and control.

Results (seen in Table 2 ) demonstrated that 72.5% of women reported having experienced at least one instance of abuse in their lifetime, while 15.9% reported no abuse. Across the different subscales, 69.9% had experienced some form of psychological abuse, 45.2% had experienced physical abuse and 21.7% had experienced sexual abuse. Over a third of participants (35.1%) had on at least one occasion had an aspect of their freedom denied by their partner.

Patriarchal beliefs

The descriptive statistics for patriarchal beliefs are also presented in Table 2 . The Mean scores ( M = 26.27, SD = 16.28) indicated an overall tendency for partners to disagree with patriarchal beliefs.

Multiple regression analyses

A detailed summary of the hierarchical regression is presented in Table 3 .

In Model 1, the univariate model, patriarchal beliefs was associated with a statistically significant 14.4% of the variance in controlling behavior. Women whose partners endorsed stronger patriarchal beliefs had less access to freedom in their relationship ( ß = −0.38, p < 0.001). Introducing demographic variables in Model 2 using the Stepwise method was associated with a statistically significant additional 10.3% of variance in control. Specifically, women experienced significantly more control (<0.05) with increasing age and significantly less control (<0.01) when they were separated compared to women who were married. The beta value for patriarchal beliefs remained statistically significant and largely unchanged with the addition of the demographic variables ( ß = −0.35, p < 0.001). Patriarchal beliefs alone accounted for 11.49% ( sr 2 = 0.12) of the total variance in controlling behavior. In addition to patriarchal beliefs, two of the 11 demographic variables were significant predictors of control. Inspection of two-way interaction effects between PBS and each of the demographic characteristics indicated no evidence of moderation occurring. The final model accounted for 23.3% of the variance in control F (12, 566) = 15.61, p < 0.001, which is considered a large effect ( Cohen, 1988 ).

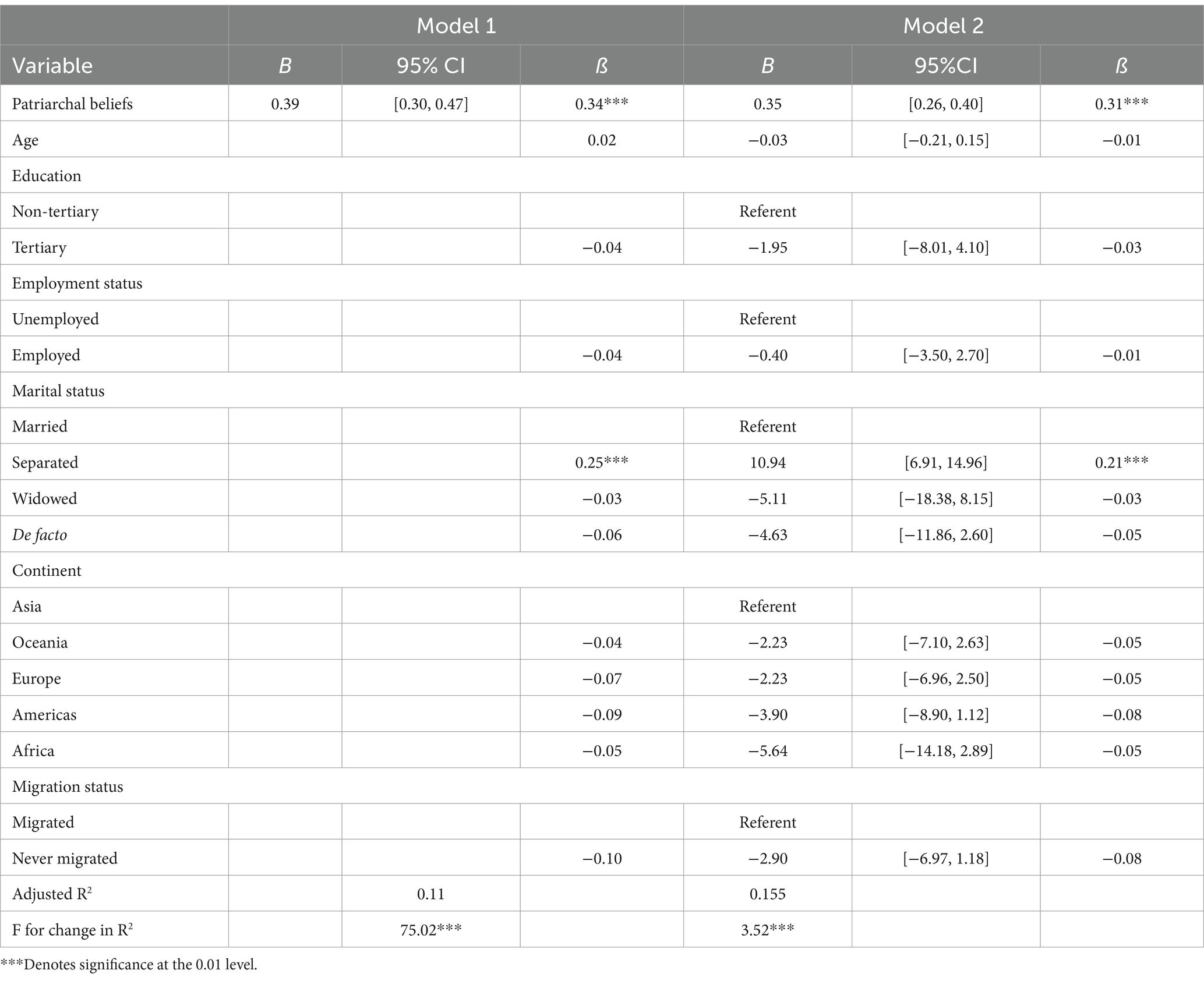

A detailed summary of the hierarchical regression is presented in Table 4 .

Table 4 . Summary of hierarchical regression analysis for variables predicting abuse ( N = 577).

For Model 1, the univariate model, partners’ patriarchal beliefs was associated with a statistically significant 11.4% of the variance in experience of abuse. Women who perceived their partners held stronger patriarchal beliefs were more likely to have been abused ( ß = 0.34, p < 0.001). The addition of demographic variables was associated with a statistically significant additional 5.7% of the variability in abuse (Model 2). This final model explained 15.5% of the variance in abuse, adjusted R 2 = 0.155, F (12, 564) = 9.79, p < 0.001, which is considered a medium effect ( Cohen, 1988 ). The beta value for patriarchal beliefs remained a significant independent predictor of abuse ( ß = 0.31 , p < 0.001). Patriarchal beliefs contributed the highest amount of variance in abuse, independently contributing 9% (sr 2 = 0.09). Inspection of two-way interaction effects between PBS and each of the demographic characteristics indicated no evidence of moderation.

This study is the first to examine the relationship between domestic violence and a partner’s adherence to patriarchal ideology in the global Indian context. The findings support the hypothesis that women who perceived their partners to endorse greater patriarchal beliefs were more likely to have been abused and subjected to controlling behavior.

The finding that partners’ patriarchal beliefs predicted DV victimization lends support to the longstanding feminist propositions that DV occurs mainly in contexts where patriarchal ideologies are dominant ( Jejeebhoy and Cook, 1997 ; Haj-Yahia, 2005 ; Satyen, 2021 ). In this study, women who believed that their partners viewed women in general as inherently inferior to men, legitimized male authority in public and private arenas, endorsed prescriptive gender roles, and condoned the use of violence for gender-role violation were more likely to be abused or controlled by their male partners. This finding is consistent with the limited existing studies that have demonstrated the relationship between male patriarchal ideologies and DV perpetration across three countries including the United States ( Sugarman and Frankel, 1996 ; Stith et al., 2004 ; Haj-Yahia, 2005 ; Adam and Schewe, 2007 ; Watto, 2009 ). By contributing to the understanding of the experiences of Indian women globally, this study highlights the pervasive and enduring negative influence of the patriarchal ideology on women.

The relationship between patriarchal beliefs and DV persisted after controlling for a range of factors such age, educational attainment, marital status, migration status, employment, and geographical location that have been previously used to explain DV victimization in Indian populations [(e.g., Sabri et al., 2014 ; Gender, 2015 ; Kalokhe et al., 2018 )]. It further emerged as the strongest independent predictor of women’s experiences of both abuse and control. Such a finding cautions against any theory of DV in Indian communities that overlooks or minimizes gender as an explanatory factor. It also suggests that merely focusing on the individual characteristics of DV victims is problematic in that it conceals the ways in which DV is embedded in broader sociocultural structures including the violence committed in childhood by a father [(e.g., Tsirigotis and Łuczak, 2018 )]. This finding removes some of responsibility and shame from both victims of DV and from individual cultural groups, by firmly situating their experiences within a patriarchal framework. This finding also has fundamental practical implications for understanding and preventing DV in Indian communities, by identifying patriarchal beliefs and practices as targets for intervention that are amenable to effecting social change in the continuance of DV.

An unexpected finding was that age, educational attainment, marital status, geographical location, migration status, and employment status did not moderate the relationship between patriarchal beliefs and DV experiences. These findings could be considered in light of the universal phenomenon of gendered violence in women and the significant role of patriarchal beliefs. This is in contrast to an intersectional framework ( Crenshaw, 1991 ) which suggests that different social factors interact and intersect with gender oppression to place certain groups of women at increased risk of DV. While it is possible that this finding may be an artefact of the specific sample included in this study, we did not measure structural patriarchy, for example, casteism and classism, which may be a better proxy for the macro-level gender oppressions and inequalities referred to in intersectionality theory ( Heise, 1998 ). In support of this explanation, one salient finding from the present study was that continent of residence was not an independent predictor of either abuse or controlling behavior and did not moderate the relationship between patriarchal beliefs and DV. This suggests that patriarchal beliefs can prevail despite structural gains in women’s empowerment or through migrating to more egalitarian locations ( Hunnicutt, 2009 ). However, the findings also demonstrated that women experienced greater controlling behavior as they became older and, in contrast to women who were married, those who were separated experienced less control. The latter findings could relate to lower levels of control because the women had separated from their partner. It is also possible that as women are older, they are more invested in their relationships and less likely to challenge greater levels of control by their partners. In sum, women’s specific social context does not appear to specify the appropriate conditions for the translation of patriarchal ideas about gender relations and, in particular, DV ( Yoon et al., 2015 ). The findings of this study highlight the need to engage with men at the individual level to challenge the patriarchal beliefs and norms that propagate, justify, and excuse DV.

Based on the findings of this study, it is clear that interventions should use a ‘gender transformative’ approach ( Gupta and Sharma, 2003 ) which acknowledges that DV is inherently gendered and a product of patriarchal ideologies. These interventions could be provided in group or individual formats, should be culturally-tailored, and work with men to promote women’s access to authority and decision-making, as well as challenge traditional gender roles and acceptance of DV ( Violence against women in Australia An overview of research and approaches to primary prevention, 2017 ). Encouraging evidence from the international literature suggest that such programs can lead to short-term changes in both attitudes and behavior, including decreased self-reported use of physical, sexual, and psychological DV ( Whitaker et al., 2006 ; Barker et al., 2010 ). However, the literature does not reveal if such programs have been piloted in Indian communities.

Limitations

The primary limitations of the current study relate to the sample characteristics and subsequent generalizability of findings. This study used a convenience sample and as such may not adequately represent Indian women across a range of societies. However, the strength is that women from 31 countries took part in the study. Second, the Partner’s Patriarchal Beliefs scale asked women to rate their perception of their partner’s beliefs, and therefore may not have accurately reflected men’s ideologies. However, attempting to understand and validate women’s lived experiences and perceptions is important in any feminist enquiry ( Yllö and Bograd, 1984 ) and wives’ accounts of their husband’s behavior have been found to be more accurate than husband’s account of his own behavior ( Arias and Beach, 1987 ). Nevertheless, future research may wish to further establish the validity and psychometric properties of the scale used. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of this study limits the extent to which we can draw conclusions regarding the temporality or causal nature of the observed associations. While theories of patriarchy suggest it fuels DV, it is also plausible that use of DV also strengthens patriarchal beliefs, by further reinforcing a system of male domination and female subordination in the family. Future studies employing a prospective or longitudinal design and representative sample will strengthen the practical significance of the findings described in this study.

Conclusions and implications for future research

Notwithstanding the aforementioned limitations, this study is novel in showing the effects of individual-level patriarchal beliefs on women’s experiences of both abuse and control using a large, cross-national sample that adjusted for a range of established risk factors and employed a validated, culturally-sensitive measure of DV. The findings raise awareness of the extent of DV in Indian communities and emphasize the need to collectively acknowledge how gender and culture interact to shape women’s experiences of DV. Such an understanding can have far-reaching implications for the reduction and prevention of DV in Indian communities, by providing mental health practitioners, community leaders, policy makers, women’s activists, and the wider community more broadly, a principal target for intervention. Given the observed associations between partners’ patriarchal beliefs and both abuse and controlling behavior, efforts should be targeted at developing culturally-tailored education strategies aimed at challenging men’s enactment of their investment in patriarchy regardless of their social situation, includingtheir education level, religion, and caste.