Essays About Eating Healthy Foods: 7 Essay Examples And Topic Ideas

If you’re writing essays about eating healthy foods, here are 7 interesting essay examples and topic ideas.

Eating healthy is one of the best ways to maintain a healthy lifestyle. But we can all struggle to make it a part of our routine. It’s easier to make small changes to your eating habits instead for long-lasting results. A healthy diet is a plan for eating healthier options over the long term and not a strict diet to be followed only for the short.

Writing an essay about eating healthy foods is an exciting topic choice and an excellent way to help people start a healthy diet and change their lifestyles for the better. Tip: For help with this topic, read our guide explaining what is persuasive writing ?

1. The Definitive Guide to Healthy Eating in Real Life By Jillian Kubala

2. eating healthy foods by jaime padilla, 3. 5 benefits of eating healthy by maggie smith, 4. good food bad food by audrey rodriguez, 5. what are the benefits of eating healthy by cathleen crichton-stuart, 6. comparison between healthy food and junk food by jaime padilla, 7. nutrition, immunity, and covid-19 by ayela spiro and helena gibson-moore, essays about eating healthy foods topic ideas, 1. what is healthy food, 2. what is the importance of healthy food, 3. what does eating healthy mean, 4. why should we eat healthy foods, 5. what are the benefits of eating healthy foods, 6. why should we eat more vegetables, 7. can you still eat healthy foods even if you are on a budget.

“Depending on whom you ask, “healthy eating” may take many forms. It seems that everyone, including healthcare professionals, wellness influencers, coworkers, and family members, has an opinion on the healthiest way to eat. Plus, nutrition articles that you read online can be downright confusing with their contradictory — and often unfounded — suggestions and rules. This doesn’t make it easy if you simply want to eat in a healthy way that works for you.”

Author Jillian Kubala is a registered dietitian and holds a master’s degree in nutrition and an undergraduate degree in nutrition science. In her essay, she says that healthy eating doesn’t have to be complicated and explains how it can nourish your body while enjoying the foods you love. Check out these essays about health .

“Eating provides your body with the nourishment it needs to survive. A healthy diet supplies nutrients (such as protein, vitamins and minerals, fiber, and carbohydrates), which are important for your body’s growth, development, and maintenance. However, not all foods are equal when it comes to the nutrition they provide. Some foods, such as fruits and vegetables, are rich in vitamins and minerals; others, such as cookies and soda pop, provide few if any nutrients. Your diet can influence everything from your energy level and intellectual performance to your risk for certain diseases.”

Author Jaime Padilla talks about the importance of a healthy diet in your body’s growth, development, and maintenance. He also mentioned that having a poor diet can lead to some health problems. Check out these essays about food .

“Eating healthy is about balance and making sure that your body is getting the necessary nutrients it needs to function properly. Healthy eating habits require that people eat fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fats, proteins, and starches. Keep in mind that healthy eating requires that you’re mindful of what you eat and drink, but also how you prepare it. For best results, individuals should avoid fried or processed foods, as well as foods high in added sugars and salts.”

Author Maggie Smith believes there’s a fine line between healthy eating and dieting. In her essay, she mentioned five benefits of eating healthy foods – weight loss, heart health, strong bones and teeth, better mood and energy levels, and improved memory and brain health – and explained them in detail.

You might also be interested in our round-up of the best medical authors of all time .

“From old generation to the new generation young people are dying out quicker than their own parents due to obesity-related diseases every day. In the mid-1970s, there were no health issues relevant to obesity-related diseases but over time it began to be a problem when fast food industries started growing at a rapid pace. Energy is naturally created in the body when the nutrients are absorbed from the food that is consumed. When living a healthy lifestyle, these horrible health problems don’t appear, and the chances of prolonging life and enjoying life increase.”

In her essay, author Audrey Rodriguez says that having self-control is very important to achieving a healthy lifestyle, especially now that we’re exposed to all these unhealthy yet tempting foods that all these fast-food restaurants offer. She believes that back in the early 1970s, when fast-food companies had not yet existed and home-cooked meals were the only food people had to eat every day, trying to live a healthy life was never a problem.

“A healthful diet typically includes nutrient-dense foods from all major food groups, including lean proteins, whole grains, healthful fats, and fruits and vegetables of many colors. Healthful eating also means replacing foods that contain trans fats, added salt, and sugar with more nutritious options. Following a healthful diet has many health benefits, including building strong bones, protecting the heart, preventing disease, and boosting mood.”

In her essay, Author Cathleen Crichton-Stuart explains the top 10 benefits of eating healthy foods – all of which are medically reviewed by Adrienne Seitz, a registered and licensed dietitian nutritionist. She also gives her readers some quick tips for a healthful diet.

“In today’s generation, healthy and unhealthy food plays a big role in youths and adults. Many people don’t really understand the difference between healthy and unhealthy foods, many don’t actually know what the result of eating too many unhealthy foods can do to the body. There are big differences between eating healthy food, unhealthy food and what the result of excessively eating them can do to the body. In the ongoing battle of “healthy vs. unhealthy foods”, unhealthy foods have their own advantage.”

Author Jaime Padilla compares the difference between healthy food and junk food so that the readers would understand what the result of eating a lot of unhealthy foods can do to the body. He also said that homemade meals are healthier and cheaper than the unhealthy and pricey meals that you order in your local fast food restaurant, which would probably cost you twice as much.

“The Covid-19 pandemic has sparked both an increased clinical and public interest in the role of nutrition and health, particularly in supporting immunity. During this time, when people may be highly vulnerable to misinformation, there have been a plethora of media stories against authoritative scientific opinion, suggesting that certain food components and supplements are capable of ‘boosting’ the immune system. It is important to provide evidence-based advice and to ensure that the use of non-evidence-based approaches to ‘boost’ immunity is not considered as an effective alternative to vaccination or other recognized measures.”

Authors Ayela Spiro, a nutrition science manager, and Helena Gibson-Moore, a nutrition scientist, enlighten their readers on the misinformation spreading in this pandemic about specific food components and supplements. They say that there’s no single food or supplement, or magic diet that can boost the immune system alone. However, eating healthy foods (along with the right dietary supplements), being physically active, and getting enough sleep can help boost your immunity.

If you’re writing an essay about eating healthy foods, you have to define what healthy food is. Food is considered healthy if it provides you with the essential nutrients to sustain your body’s well-being and retain energy. Carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, minerals, and water are the essential nutrients that compose a healthy, balanced diet.

Eating healthy foods is essential for having good health and nutrition – it protects you against many chronic non-communicable diseases, including heart disease, diabetes, and cancer. If you’re writing an essay about eating healthy foods, show your readers the importance of healthy food, and encourage them to start a healthy diet.

Eating healthy foods means eating a variety of food that give you the nutrients that your body needs to function correctly. These nutrients include carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, minerals, and water. In your essay about eating healthy foods, you can discuss this topic in more detail so that your readers will know why these nutrients are essential.

Eating healthy foods includes consuming the essential nutrients your body requires to function correctly (such as carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, minerals, and water) while minimizing processed foods, saturated fats, and alcohol. In your essay, let your readers know that eating healthy foods can help maintain the body’s everyday functions, promote optimal body weight, and prevent diseases.

Eating healthy foods comes with many health benefits – from keeping a healthy weight to preventing long-term diseases such as heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and cancer. So if you’re looking for a topic idea for your essay, you can consider the benefits of eating healthy foods to give your readers some useful information, especially for those thinking of starting a healthy diet.

Ever since we were a kid, we have all been told that eating vegetables are good for our health, but why? The answer is pretty simple – vegetables are loaded with the essential nutrients, vitamins, and minerals that our body needs. So, if you’re writing an essay about eating healthy foods, this is an excellent topic to get you started.

Of course, you definitely can! Fresh fruits and vegetables are typically the cheapest options for starting a healthy diet. In your essay about eating healthy foods, you can include some other cheap food options for a healthy diet – this will be very helpful, especially for readers looking to start a healthy diet but only have a limited amount of budget set for their daily food.

For help with this topic, read our guide explaining what is persuasive writing ?

If you’re stuck picking your next essay topic, check out our round-up of essay topics about education .

Bryan Collins is the owner of Become a Writer Today. He's an author from Ireland who helps writers build authority and earn a living from their creative work. He's also a former Forbes columnist and his work has appeared in publications like Lifehacker and Fast Company.

View all posts

- CBSE Class 10th

- CBSE Class 12th

- UP Board 10th

- UP Board 12th

- Bihar Board 10th

- Bihar Board 12th

- Top Schools in India

- Top Schools in Delhi

- Top Schools in Mumbai

- Top Schools in Chennai

- Top Schools in Hyderabad

- Top Schools in Kolkata

- Top Schools in Pune

- Top Schools in Bangalore

Products & Resources

- JEE Main Knockout April

- Free Sample Papers

- Free Ebooks

- NCERT Notes

- NCERT Syllabus

- NCERT Books

- RD Sharma Solutions

- Navodaya Vidyalaya Admission 2024-25

- NCERT Solutions

- NCERT Solutions for Class 12

- NCERT Solutions for Class 11

- NCERT solutions for Class 10

- NCERT solutions for Class 9

- NCERT solutions for Class 8

- NCERT Solutions for Class 7

- JEE Main 2024

- JEE Advanced 2024

- BITSAT 2024

- View All Engineering Exams

- Colleges Accepting B.Tech Applications

- Top Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Engineering Colleges Accepting JEE Main

- Top IITs in India

- Top NITs in India

- Top IIITs in India

- JEE Main College Predictor

- JEE Main Rank Predictor

- MHT CET College Predictor

- AP EAMCET College Predictor

- GATE College Predictor

- KCET College Predictor

- JEE Advanced College Predictor

- View All College Predictors

- JEE Main Question Paper

- JEE Main Mock Test

- JEE Main Registration

- JEE Main Syllabus

- Download E-Books and Sample Papers

- Compare Colleges

- B.Tech College Applications

- GATE 2024 Result

- MAH MBA CET Exam

- View All Management Exams

Colleges & Courses

- MBA College Admissions

- MBA Colleges in India

- Top IIMs Colleges in India

- Top Online MBA Colleges in India

- MBA Colleges Accepting XAT Score

- BBA Colleges in India

- XAT College Predictor 2024

- SNAP College Predictor

- NMAT College Predictor

- MAT College Predictor 2024

- CMAT College Predictor 2024

- CAT Percentile Predictor 2023

- CAT 2023 College Predictor

- CMAT 2024 Registration

- TS ICET 2024 Registration

- CMAT Exam Date 2024

- MAH MBA CET Cutoff 2024

- Download Helpful Ebooks

- List of Popular Branches

- QnA - Get answers to your doubts

- IIM Fees Structure

- AIIMS Nursing

- Top Medical Colleges in India

- Top Medical Colleges in India accepting NEET Score

- Medical Colleges accepting NEET

- List of Medical Colleges in India

- List of AIIMS Colleges In India

- Medical Colleges in Maharashtra

- Medical Colleges in India Accepting NEET PG

- NEET College Predictor

- NEET PG College Predictor

- NEET MDS College Predictor

- DNB CET College Predictor

- DNB PDCET College Predictor

- NEET Application Form 2024

- NEET PG Application Form 2024

- NEET Cut off

- NEET Online Preparation

- Download Helpful E-books

- LSAT India 2024

- Colleges Accepting Admissions

- Top Law Colleges in India

- Law College Accepting CLAT Score

- List of Law Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Delhi

- Top Law Collages in Indore

- Top Law Colleges in Chandigarh

- Top Law Collages in Lucknow

Predictors & E-Books

- CLAT College Predictor

- MHCET Law ( 5 Year L.L.B) College Predictor

- AILET College Predictor

- Sample Papers

- Compare Law Collages

- Careers360 Youtube Channel

- CLAT Syllabus 2025

- CLAT Previous Year Question Paper

- AIBE 18 Result 2023

- NID DAT Exam

- Pearl Academy Exam

Animation Courses

- Animation Courses in India

- Animation Courses in Bangalore

- Animation Courses in Mumbai

- Animation Courses in Pune

- Animation Courses in Chennai

- Animation Courses in Hyderabad

- Design Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in Bangalore

- Fashion Design Colleges in Mumbai

- Fashion Design Colleges in Pune

- Fashion Design Colleges in Delhi

- Fashion Design Colleges in Hyderabad

- Fashion Design Colleges in India

- Top Design Colleges in India

- Free Design E-books

- List of Branches

- Careers360 Youtube channel

- NIFT College Predictor

- UCEED College Predictor

- NID DAT College Predictor

- IPU CET BJMC

- JMI Mass Communication Entrance Exam

- IIMC Entrance Exam

- Media & Journalism colleges in Delhi

- Media & Journalism colleges in Bangalore

- Media & Journalism colleges in Mumbai

- List of Media & Journalism Colleges in India

- CA Intermediate

- CA Foundation

- CS Executive

- CS Professional

- Difference between CA and CS

- Difference between CA and CMA

- CA Full form

- CMA Full form

- CS Full form

- CA Salary In India

Top Courses & Careers

- Bachelor of Commerce (B.Com)

- Master of Commerce (M.Com)

- Company Secretary

- Cost Accountant

- Charted Accountant

- Credit Manager

- Financial Advisor

- Top Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Government Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Private Commerce Colleges in India

- Top M.Com Colleges in Mumbai

- Top B.Com Colleges in India

- IT Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- IT Colleges in Uttar Pradesh

- MCA Colleges in India

- BCA Colleges in India

Quick Links

- Information Technology Courses

- Programming Courses

- Web Development Courses

- Data Analytics Courses

- Big Data Analytics Courses

- RUHS Pharmacy Admission Test

- Top Pharmacy Colleges in India

- Pharmacy Colleges in Pune

- Pharmacy Colleges in Mumbai

- Colleges Accepting GPAT Score

- Pharmacy Colleges in Lucknow

- List of Pharmacy Colleges in Nagpur

- GPAT Result

- GPAT 2024 Admit Card

- GPAT Question Papers

- NCHMCT JEE 2024

- Mah BHMCT CET

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Delhi

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Hyderabad

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Maharashtra

- B.Sc Hotel Management

- Hotel Management

- Diploma in Hotel Management and Catering Technology

Diploma Colleges

- Top Diploma Colleges in Maharashtra

- UPSC IAS 2024

- SSC CGL 2024

- IBPS RRB 2024

- Previous Year Sample Papers

- Free Competition E-books

- Sarkari Result

- QnA- Get your doubts answered

- UPSC Previous Year Sample Papers

- CTET Previous Year Sample Papers

- SBI Clerk Previous Year Sample Papers

- NDA Previous Year Sample Papers

Upcoming Events

- NDA Application Form 2024

- UPSC IAS Application Form 2024

- CDS Application Form 2024

- CTET Admit card 2024

- HP TET Result 2023

- SSC GD Constable Admit Card 2024

- UPTET Notification 2024

- SBI Clerk Result 2024

Other Exams

- SSC CHSL 2024

- UP PCS 2024

- UGC NET 2024

- RRB NTPC 2024

- IBPS PO 2024

- IBPS Clerk 2024

- IBPS SO 2024

- Top University in USA

- Top University in Canada

- Top University in Ireland

- Top Universities in UK

- Top Universities in Australia

- Best MBA Colleges in Abroad

- Business Management Studies Colleges

Top Countries

- Study in USA

- Study in UK

- Study in Canada

- Study in Australia

- Study in Ireland

- Study in Germany

- Study in China

- Study in Europe

Student Visas

- Student Visa Canada

- Student Visa UK

- Student Visa USA

- Student Visa Australia

- Student Visa Germany

- Student Visa New Zealand

- Student Visa Ireland

- CUET PG 2024

- IGNOU B.Ed Admission 2024

- DU Admission

- UP B.Ed JEE 2024

- DDU Entrance Exam

- IIT JAM 2024

- IGNOU Online Admission 2024

- Universities in India

- Top Universities in India 2024

- Top Colleges in India

- Top Universities in Uttar Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Bihar

- Top Universities in Madhya Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Tamil Nadu 2024

- Central Universities in India

- CUET PG Admit Card 2024

- IGNOU Date Sheet

- CUET Mock Test 2024

- CUET Application Form 2024

- CUET PG Syllabus 2024

- CUET Participating Universities 2024

- CUET Previous Year Question Paper

- CUET Syllabus 2024 for Science Students

- E-Books and Sample Papers

- CUET Exam Pattern 2024

- CUET Exam Date 2024

- CUET Syllabus 2024

- IGNOU Exam Form 2024

- IGNOU Result

- CUET PG Courses 2024

Engineering Preparation

- Knockout JEE Main 2024

- Test Series JEE Main 2024

- JEE Main 2024 Rank Booster

Medical Preparation

- Knockout NEET 2024

- Test Series NEET 2024

- Rank Booster NEET 2024

Online Courses

- JEE Main One Month Course

- NEET One Month Course

- IBSAT Free Mock Tests

- IIT JEE Foundation Course

- Knockout BITSAT 2024

- Career Guidance Tool

Top Streams

- IT & Software Certification Courses

- Engineering and Architecture Certification Courses

- Programming And Development Certification Courses

- Business and Management Certification Courses

- Marketing Certification Courses

- Health and Fitness Certification Courses

- Design Certification Courses

Specializations

- Digital Marketing Certification Courses

- Cyber Security Certification Courses

- Artificial Intelligence Certification Courses

- Business Analytics Certification Courses

- Data Science Certification Courses

- Cloud Computing Certification Courses

- Machine Learning Certification Courses

- View All Certification Courses

- UG Degree Courses

- PG Degree Courses

- Short Term Courses

- Free Courses

- Online Degrees and Diplomas

- Compare Courses

Top Providers

- Coursera Courses

- Udemy Courses

- Edx Courses

- Swayam Courses

- upGrad Courses

- Simplilearn Courses

- Great Learning Courses

Access premium articles, webinars, resources to make the best decisions for career, course, exams, scholarships, study abroad and much more with

Plan, Prepare & Make the Best Career Choices

Healthy Food Essay

The food that we put into our bodies has a direct impact on our overall health and well-being. Eating a diet that is rich in nutritious, whole foods can help us maintain a healthy weight, prevent chronic diseases, and feel our best. It is important to make conscious, healthy food choices to support our physical and mental well-being. By incorporating a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins into our diets, we can ensure that our bodies are getting the nutrients they need to thrive. Here are a few sample essays on healthy food.

100 Words Essay On Healthy Food

Healthy food is essential to maintaining a healthy and balanced lifestyle. First and foremost, healthy food is food that is nutritious and good for the body. This means that it provides the body with the vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients it needs to function properly. Healthy food can come in many forms, including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats. Healthy food is important for maintaining a healthy body and mind. It provides the nutrients and energy the body needs to function properly and can help to prevent a wide range of health problems. So, if you want to feel your best, be sure to make healthy food a priority in your life.

200 Words Essay On Healthy Food

Healthy food is not just about what you eat – it’s also about how you eat it. For example, eating fresh, whole foods that are prepared at home with love and care is generally considered to be healthier than eating processed, pre-packaged foods that are high in salt, sugar, and unhealthy fats. Additionally, eating in moderation and avoiding excessive portion sizes is key to maintaining a healthy diet.

There are many reasons to eat healthy food, but the most obvious one is that it can help to prevent a wide range of health problems. Eating a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and other healthy foods can help to lower your risk of heart disease, stroke, obesity, and other chronic conditions. Additionally, healthy food can help to boost your immune system, giving your body the tools it needs to fight off illness and infection. But the benefits of healthy food go beyond just physical health. Eating well can also have a profound impact on your mental and emotional well-being. A healthy diet can help to reduce stress and anxiety, improve mood, and increase energy levels. It can also help to improve cognitive function and memory, making it easier to focus and concentrate.

500 Words Essay On Healthy Food

Healthy food is an essential aspect of a healthy lifestyle. It is not only crucial for maintaining physical health, but it can also have a significant impact on our mental and emotional well-being. Eating a balanced diet that includes a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins can help us feel energised, focused, and happy. But for many people, eating healthy can be a challenge. In a world where fast food and processed snacks are readily available and often more convenient than cooking a meal from scratch, it can be tempting to choose unhealthy options. And with busy schedules and hectic lives, it can be difficult to find the time and energy to plan and prepare healthy meals.

However, the benefits of eating healthy far outweigh the challenges. Not only can it help us maintain a healthy weight and reduce our risk of chronic diseases like heart disease, diabetes, and cancer, but it can also improve our mood, energy levels, and overall quality of life.

My Experience

As I sat down at my desk with a bag of chips and a soda for lunch again, I realised that I had been making unhealthy food choices all week. I had been so busy with work and other obligations that I hadn't taken the time to plan and prepare healthy meals. I decided then and there to make a change. I started by making a grocery list of nutritious, whole foods and meal planning for the week ahead. I also made a commitment to myself to cook at home more often instead of relying on takeout or fast food. It wasn't easy at first, but over time, I started to notice a difference in my energy levels and overall mood. I felt better physically and mentally, and I was able to maintain a healthy weight. Making healthy food choices became a priority for me, and I am now reaping the numerous benefits of a nutritious diet.

One of the key components of a healthy diet is variety. Eating a diverse range of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins can provide our bodies with the nutrients, vitamins, and minerals we need to function at our best. It's important to try to incorporate a rainbow of colours into our diets, as each colour group represents different nutrients and health benefits. For example, orange and yellow fruits and vegetables are rich in vitamin C and beta-carotene, which can support healthy skin and eyesight. Green leafy vegetables like spinach and kale are packed with antioxidants and can help support a healthy immune system. And blue and purple fruits and vegetables, like blueberries and eggplants, are high in flavonoids and can help support brain health and cognitive function.

In addition to eating a variety of fruits and vegetables, it's also important to include whole grains in our diets. Whole grains, like quinoa, brown rice, and oatmeal, are a great source of fibre, which can help keep us feeling full and satisfied. They can also help regulate our blood sugar levels, which can keep our energy levels steady and prevent unhealthy cravings.

Explore Career Options (By Industry)

- Construction

- Entertainment

- Manufacturing

- Information Technology

Bio Medical Engineer

The field of biomedical engineering opens up a universe of expert chances. An Individual in the biomedical engineering career path work in the field of engineering as well as medicine, in order to find out solutions to common problems of the two fields. The biomedical engineering job opportunities are to collaborate with doctors and researchers to develop medical systems, equipment, or devices that can solve clinical problems. Here we will be discussing jobs after biomedical engineering, how to get a job in biomedical engineering, biomedical engineering scope, and salary.

Data Administrator

Database professionals use software to store and organise data such as financial information, and customer shipping records. Individuals who opt for a career as data administrators ensure that data is available for users and secured from unauthorised sales. DB administrators may work in various types of industries. It may involve computer systems design, service firms, insurance companies, banks and hospitals.

Ethical Hacker

A career as ethical hacker involves various challenges and provides lucrative opportunities in the digital era where every giant business and startup owns its cyberspace on the world wide web. Individuals in the ethical hacker career path try to find the vulnerabilities in the cyber system to get its authority. If he or she succeeds in it then he or she gets its illegal authority. Individuals in the ethical hacker career path then steal information or delete the file that could affect the business, functioning, or services of the organization.

Data Analyst

The invention of the database has given fresh breath to the people involved in the data analytics career path. Analysis refers to splitting up a whole into its individual components for individual analysis. Data analysis is a method through which raw data are processed and transformed into information that would be beneficial for user strategic thinking.

Data are collected and examined to respond to questions, evaluate hypotheses or contradict theories. It is a tool for analyzing, transforming, modeling, and arranging data with useful knowledge, to assist in decision-making and methods, encompassing various strategies, and is used in different fields of business, research, and social science.

Geothermal Engineer

Individuals who opt for a career as geothermal engineers are the professionals involved in the processing of geothermal energy. The responsibilities of geothermal engineers may vary depending on the workplace location. Those who work in fields design facilities to process and distribute geothermal energy. They oversee the functioning of machinery used in the field.

Remote Sensing Technician

Individuals who opt for a career as a remote sensing technician possess unique personalities. Remote sensing analysts seem to be rational human beings, they are strong, independent, persistent, sincere, realistic and resourceful. Some of them are analytical as well, which means they are intelligent, introspective and inquisitive.

Remote sensing scientists use remote sensing technology to support scientists in fields such as community planning, flight planning or the management of natural resources. Analysing data collected from aircraft, satellites or ground-based platforms using statistical analysis software, image analysis software or Geographic Information Systems (GIS) is a significant part of their work. Do you want to learn how to become remote sensing technician? There's no need to be concerned; we've devised a simple remote sensing technician career path for you. Scroll through the pages and read.

Geotechnical engineer

The role of geotechnical engineer starts with reviewing the projects needed to define the required material properties. The work responsibilities are followed by a site investigation of rock, soil, fault distribution and bedrock properties on and below an area of interest. The investigation is aimed to improve the ground engineering design and determine their engineering properties that include how they will interact with, on or in a proposed construction.

The role of geotechnical engineer in mining includes designing and determining the type of foundations, earthworks, and or pavement subgrades required for the intended man-made structures to be made. Geotechnical engineering jobs are involved in earthen and concrete dam construction projects, working under a range of normal and extreme loading conditions.

Cartographer

How fascinating it is to represent the whole world on just a piece of paper or a sphere. With the help of maps, we are able to represent the real world on a much smaller scale. Individuals who opt for a career as a cartographer are those who make maps. But, cartography is not just limited to maps, it is about a mixture of art , science , and technology. As a cartographer, not only you will create maps but use various geodetic surveys and remote sensing systems to measure, analyse, and create different maps for political, cultural or educational purposes.

Budget Analyst

Budget analysis, in a nutshell, entails thoroughly analyzing the details of a financial budget. The budget analysis aims to better understand and manage revenue. Budget analysts assist in the achievement of financial targets, the preservation of profitability, and the pursuit of long-term growth for a business. Budget analysts generally have a bachelor's degree in accounting, finance, economics, or a closely related field. Knowledge of Financial Management is of prime importance in this career.

Product Manager

A Product Manager is a professional responsible for product planning and marketing. He or she manages the product throughout the Product Life Cycle, gathering and prioritising the product. A product manager job description includes defining the product vision and working closely with team members of other departments to deliver winning products.

Underwriter

An underwriter is a person who assesses and evaluates the risk of insurance in his or her field like mortgage, loan, health policy, investment, and so on and so forth. The underwriter career path does involve risks as analysing the risks means finding out if there is a way for the insurance underwriter jobs to recover the money from its clients. If the risk turns out to be too much for the company then in the future it is an underwriter who will be held accountable for it. Therefore, one must carry out his or her job with a lot of attention and diligence.

Finance Executive

Operations manager.

Individuals in the operations manager jobs are responsible for ensuring the efficiency of each department to acquire its optimal goal. They plan the use of resources and distribution of materials. The operations manager's job description includes managing budgets, negotiating contracts, and performing administrative tasks.

Bank Probationary Officer (PO)

Investment director.

An investment director is a person who helps corporations and individuals manage their finances. They can help them develop a strategy to achieve their goals, including paying off debts and investing in the future. In addition, he or she can help individuals make informed decisions.

Welding Engineer

Welding Engineer Job Description: A Welding Engineer work involves managing welding projects and supervising welding teams. He or she is responsible for reviewing welding procedures, processes and documentation. A career as Welding Engineer involves conducting failure analyses and causes on welding issues.

Transportation Planner

A career as Transportation Planner requires technical application of science and technology in engineering, particularly the concepts, equipment and technologies involved in the production of products and services. In fields like land use, infrastructure review, ecological standards and street design, he or she considers issues of health, environment and performance. A Transportation Planner assigns resources for implementing and designing programmes. He or she is responsible for assessing needs, preparing plans and forecasts and compliance with regulations.

An expert in plumbing is aware of building regulations and safety standards and works to make sure these standards are upheld. Testing pipes for leakage using air pressure and other gauges, and also the ability to construct new pipe systems by cutting, fitting, measuring and threading pipes are some of the other more involved aspects of plumbing. Individuals in the plumber career path are self-employed or work for a small business employing less than ten people, though some might find working for larger entities or the government more desirable.

Construction Manager

Individuals who opt for a career as construction managers have a senior-level management role offered in construction firms. Responsibilities in the construction management career path are assigning tasks to workers, inspecting their work, and coordinating with other professionals including architects, subcontractors, and building services engineers.

Urban Planner

Urban Planning careers revolve around the idea of developing a plan to use the land optimally, without affecting the environment. Urban planning jobs are offered to those candidates who are skilled in making the right use of land to distribute the growing population, to create various communities.

Urban planning careers come with the opportunity to make changes to the existing cities and towns. They identify various community needs and make short and long-term plans accordingly.

Highway Engineer

Highway Engineer Job Description: A Highway Engineer is a civil engineer who specialises in planning and building thousands of miles of roads that support connectivity and allow transportation across the country. He or she ensures that traffic management schemes are effectively planned concerning economic sustainability and successful implementation.

Environmental Engineer

Individuals who opt for a career as an environmental engineer are construction professionals who utilise the skills and knowledge of biology, soil science, chemistry and the concept of engineering to design and develop projects that serve as solutions to various environmental problems.

Naval Architect

A Naval Architect is a professional who designs, produces and repairs safe and sea-worthy surfaces or underwater structures. A Naval Architect stays involved in creating and designing ships, ferries, submarines and yachts with implementation of various principles such as gravity, ideal hull form, buoyancy and stability.

Orthotist and Prosthetist

Orthotists and Prosthetists are professionals who provide aid to patients with disabilities. They fix them to artificial limbs (prosthetics) and help them to regain stability. There are times when people lose their limbs in an accident. In some other occasions, they are born without a limb or orthopaedic impairment. Orthotists and prosthetists play a crucial role in their lives with fixing them to assistive devices and provide mobility.

Veterinary Doctor

Pathologist.

A career in pathology in India is filled with several responsibilities as it is a medical branch and affects human lives. The demand for pathologists has been increasing over the past few years as people are getting more aware of different diseases. Not only that, but an increase in population and lifestyle changes have also contributed to the increase in a pathologist’s demand. The pathology careers provide an extremely huge number of opportunities and if you want to be a part of the medical field you can consider being a pathologist. If you want to know more about a career in pathology in India then continue reading this article.

Speech Therapist

Gynaecologist.

Gynaecology can be defined as the study of the female body. The job outlook for gynaecology is excellent since there is evergreen demand for one because of their responsibility of dealing with not only women’s health but also fertility and pregnancy issues. Although most women prefer to have a women obstetrician gynaecologist as their doctor, men also explore a career as a gynaecologist and there are ample amounts of male doctors in the field who are gynaecologists and aid women during delivery and childbirth.

An oncologist is a specialised doctor responsible for providing medical care to patients diagnosed with cancer. He or she uses several therapies to control the cancer and its effect on the human body such as chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiation therapy and biopsy. An oncologist designs a treatment plan based on a pathology report after diagnosing the type of cancer and where it is spreading inside the body.

Audiologist

The audiologist career involves audiology professionals who are responsible to treat hearing loss and proactively preventing the relevant damage. Individuals who opt for a career as an audiologist use various testing strategies with the aim to determine if someone has a normal sensitivity to sounds or not. After the identification of hearing loss, a hearing doctor is required to determine which sections of the hearing are affected, to what extent they are affected, and where the wound causing the hearing loss is found. As soon as the hearing loss is identified, the patients are provided with recommendations for interventions and rehabilitation such as hearing aids, cochlear implants, and appropriate medical referrals. While audiology is a branch of science that studies and researches hearing, balance, and related disorders.

Hospital Administrator

The hospital Administrator is in charge of organising and supervising the daily operations of medical services and facilities. This organising includes managing of organisation’s staff and its members in service, budgets, service reports, departmental reporting and taking reminders of patient care and services.

For an individual who opts for a career as an actor, the primary responsibility is to completely speak to the character he or she is playing and to persuade the crowd that the character is genuine by connecting with them and bringing them into the story. This applies to significant roles and littler parts, as all roles join to make an effective creation. Here in this article, we will discuss how to become an actor in India, actor exams, actor salary in India, and actor jobs.

Individuals who opt for a career as acrobats create and direct original routines for themselves, in addition to developing interpretations of existing routines. The work of circus acrobats can be seen in a variety of performance settings, including circus, reality shows, sports events like the Olympics, movies and commercials. Individuals who opt for a career as acrobats must be prepared to face rejections and intermittent periods of work. The creativity of acrobats may extend to other aspects of the performance. For example, acrobats in the circus may work with gym trainers, celebrities or collaborate with other professionals to enhance such performance elements as costume and or maybe at the teaching end of the career.

Video Game Designer

Career as a video game designer is filled with excitement as well as responsibilities. A video game designer is someone who is involved in the process of creating a game from day one. He or she is responsible for fulfilling duties like designing the character of the game, the several levels involved, plot, art and similar other elements. Individuals who opt for a career as a video game designer may also write the codes for the game using different programming languages.

Depending on the video game designer job description and experience they may also have to lead a team and do the early testing of the game in order to suggest changes and find loopholes.

Radio Jockey

Radio Jockey is an exciting, promising career and a great challenge for music lovers. If you are really interested in a career as radio jockey, then it is very important for an RJ to have an automatic, fun, and friendly personality. If you want to get a job done in this field, a strong command of the language and a good voice are always good things. Apart from this, in order to be a good radio jockey, you will also listen to good radio jockeys so that you can understand their style and later make your own by practicing.

A career as radio jockey has a lot to offer to deserving candidates. If you want to know more about a career as radio jockey, and how to become a radio jockey then continue reading the article.

Choreographer

The word “choreography" actually comes from Greek words that mean “dance writing." Individuals who opt for a career as a choreographer create and direct original dances, in addition to developing interpretations of existing dances. A Choreographer dances and utilises his or her creativity in other aspects of dance performance. For example, he or she may work with the music director to select music or collaborate with other famous choreographers to enhance such performance elements as lighting, costume and set design.

Videographer

Multimedia specialist.

A multimedia specialist is a media professional who creates, audio, videos, graphic image files, computer animations for multimedia applications. He or she is responsible for planning, producing, and maintaining websites and applications.

Social Media Manager

A career as social media manager involves implementing the company’s or brand’s marketing plan across all social media channels. Social media managers help in building or improving a brand’s or a company’s website traffic, build brand awareness, create and implement marketing and brand strategy. Social media managers are key to important social communication as well.

Copy Writer

In a career as a copywriter, one has to consult with the client and understand the brief well. A career as a copywriter has a lot to offer to deserving candidates. Several new mediums of advertising are opening therefore making it a lucrative career choice. Students can pursue various copywriter courses such as Journalism , Advertising , Marketing Management . Here, we have discussed how to become a freelance copywriter, copywriter career path, how to become a copywriter in India, and copywriting career outlook.

Careers in journalism are filled with excitement as well as responsibilities. One cannot afford to miss out on the details. As it is the small details that provide insights into a story. Depending on those insights a journalist goes about writing a news article. A journalism career can be stressful at times but if you are someone who is passionate about it then it is the right choice for you. If you want to know more about the media field and journalist career then continue reading this article.

For publishing books, newspapers, magazines and digital material, editorial and commercial strategies are set by publishers. Individuals in publishing career paths make choices about the markets their businesses will reach and the type of content that their audience will be served. Individuals in book publisher careers collaborate with editorial staff, designers, authors, and freelance contributors who develop and manage the creation of content.

In a career as a vlogger, one generally works for himself or herself. However, once an individual has gained viewership there are several brands and companies that approach them for paid collaboration. It is one of those fields where an individual can earn well while following his or her passion.

Ever since internet costs got reduced the viewership for these types of content has increased on a large scale. Therefore, a career as a vlogger has a lot to offer. If you want to know more about the Vlogger eligibility, roles and responsibilities then continue reading the article.

Individuals in the editor career path is an unsung hero of the news industry who polishes the language of the news stories provided by stringers, reporters, copywriters and content writers and also news agencies. Individuals who opt for a career as an editor make it more persuasive, concise and clear for readers. In this article, we will discuss the details of the editor's career path such as how to become an editor in India, editor salary in India and editor skills and qualities.

Linguistic meaning is related to language or Linguistics which is the study of languages. A career as a linguistic meaning, a profession that is based on the scientific study of language, and it's a very broad field with many specialities. Famous linguists work in academia, researching and teaching different areas of language, such as phonetics (sounds), syntax (word order) and semantics (meaning).

Other researchers focus on specialities like computational linguistics, which seeks to better match human and computer language capacities, or applied linguistics, which is concerned with improving language education. Still, others work as language experts for the government, advertising companies, dictionary publishers and various other private enterprises. Some might work from home as freelance linguists. Philologist, phonologist, and dialectician are some of Linguist synonym. Linguists can study French , German , Italian .

Public Relation Executive

Travel journalist.

The career of a travel journalist is full of passion, excitement and responsibility. Journalism as a career could be challenging at times, but if you're someone who has been genuinely enthusiastic about all this, then it is the best decision for you. Travel journalism jobs are all about insightful, artfully written, informative narratives designed to cover the travel industry. Travel Journalist is someone who explores, gathers and presents information as a news article.

Quality Controller

A quality controller plays a crucial role in an organisation. He or she is responsible for performing quality checks on manufactured products. He or she identifies the defects in a product and rejects the product.

A quality controller records detailed information about products with defects and sends it to the supervisor or plant manager to take necessary actions to improve the production process.

Production Manager

Merchandiser.

A QA Lead is in charge of the QA Team. The role of QA Lead comes with the responsibility of assessing services and products in order to determine that he or she meets the quality standards. He or she develops, implements and manages test plans.

Metallurgical Engineer

A metallurgical engineer is a professional who studies and produces materials that bring power to our world. He or she extracts metals from ores and rocks and transforms them into alloys, high-purity metals and other materials used in developing infrastructure, transportation and healthcare equipment.

Azure Administrator

An Azure Administrator is a professional responsible for implementing, monitoring, and maintaining Azure Solutions. He or she manages cloud infrastructure service instances and various cloud servers as well as sets up public and private cloud systems.

AWS Solution Architect

An AWS Solution Architect is someone who specializes in developing and implementing cloud computing systems. He or she has a good understanding of the various aspects of cloud computing and can confidently deploy and manage their systems. He or she troubleshoots the issues and evaluates the risk from the third party.

Computer Programmer

Careers in computer programming primarily refer to the systematic act of writing code and moreover include wider computer science areas. The word 'programmer' or 'coder' has entered into practice with the growing number of newly self-taught tech enthusiasts. Computer programming careers involve the use of designs created by software developers and engineers and transforming them into commands that can be implemented by computers. These commands result in regular usage of social media sites, word-processing applications and browsers.

ITSM Manager

Information security manager.

Individuals in the information security manager career path involves in overseeing and controlling all aspects of computer security. The IT security manager job description includes planning and carrying out security measures to protect the business data and information from corruption, theft, unauthorised access, and deliberate attack

Business Intelligence Developer

Applications for admissions are open..

JEE Main Important Chemistry formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Chemistry formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

Aakash iACST Scholarship Test 2024

Get up to 90% scholarship on NEET, JEE & Foundation courses

Resonance Coaching

Enroll in Resonance Coaching for success in JEE/NEET exams

TOEFL ® Registrations 2024

Thinking of Studying Abroad? Think the TOEFL® test. Register now & Save 10% on English Proficiency Tests with Gift Cards

ALLEN JEE Exam Prep

Start your JEE preparation with ALLEN

NEET 2024 Most scoring concepts

Just Study 32% of the NEET syllabus and Score upto 100% marks

Everything about Education

Latest updates, Exclusive Content, Webinars and more.

Download Careers360 App's

Regular exam updates, QnA, Predictors, College Applications & E-books now on your Mobile

Cetifications

We Appeared in

Healthy Food Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on healthy food.

Healthy food refers to food that contains the right amount of nutrients to keep our body fit. We need healthy food to keep ourselves fit.

Furthermore, healthy food is also very delicious as opposed to popular thinking. Nowadays, kids need to eat healthy food more than ever. We must encourage good eating habits so that our future generations will be healthy and fit.

Most importantly, the harmful effects of junk food and the positive impact of healthy food must be stressed upon. People should teach kids from an early age about the same.

Benefits of Healthy Food

Healthy food does not have merely one but numerous benefits. It helps us in various spheres of life. Healthy food does not only impact our physical health but mental health too.

When we intake healthy fruits and vegetables that are full of nutrients, we reduce the chances of diseases. For instance, green vegetables help us to maintain strength and vigor. In addition, certain healthy food items keep away long-term illnesses like diabetes and blood pressure.

Similarly, obesity is the biggest problems our country is facing now. People are falling prey to obesity faster than expected. However, this can still be controlled. Obese people usually indulge in a lot of junk food. The junk food contains sugar, salt fats and more which contribute to obesity. Healthy food can help you get rid of all this as it does not contain harmful things.

In addition, healthy food also helps you save money. It is much cheaper in comparison to junk food. Plus all that goes into the preparation of healthy food is also of low cost. Thus, you will be saving a great amount when you only consume healthy food.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Junk food vs Healthy Food

If we look at the scenario today, we see how the fast-food market is increasing at a rapid rate. With the onset of food delivery apps and more, people now like having junk food more. In addition, junk food is also tastier and easier to prepare.

However, just to satisfy our taste buds we are risking our health. You may feel more satisfied after having junk food but that is just the feeling of fullness and nothing else. Consumption of junk food leads to poor concentration. Moreover, you may also get digestive problems as junk food does not have fiber which helps indigestion.

Similarly, irregularity of blood sugar levels happens because of junk food. It is so because it contains fewer carbohydrates and protein . Also, junk food increases levels of cholesterol and triglyceride.

On the other hand, healthy food contains a plethora of nutrients. It not only keeps your body healthy but also your mind and soul. It increases our brain’s functionality. Plus, it enhances our immunity system . Intake of whole foods with minimum or no processing is the finest for one’s health.

In short, we must recognize that though junk food may seem more tempting and appealing, it comes with a great cost. A cost which is very hard to pay. Therefore, we all must have healthy foods and strive for a longer and healthier life.

FAQs on Healthy Food

Q.1 How does healthy food benefit us?

A.1 Healthy Benefit has a lot of benefits. It keeps us healthy and fit. Moreover, it keeps away diseases like diabetes, blood pressure, cholesterol and many more. Healthy food also helps in fighting obesity and heart diseases.

Q.2 Why is junk food harmful?

A.2 Junk food is very harmful to our bodies. It contains high amounts of sugar, salt, fats, oils and more which makes us unhealthy. It also causes a lot of problems like obesity and high blood pressure. Therefore, we must not have junk food more and encourage healthy eating habits.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Nutrition, Food and Diet in Health and Longevity: We Eat What We Are

Suresh i. s. rattan.

1 Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Aarhus University, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark

Gurcharan Kaur

2 Department of Biotechnology, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar 143005, India

Associated Data

Not applicable.

Nutrition generally refers to the macro- and micro-nutrients essential for survival, but we do not simply eat nutrition. Instead, we eat animal- and plant-based foods without always being conscious of its nutritional value. Furthermore, various cultural factors influence and shape our taste, preferences, taboos and practices towards preparing and consuming food as a meal and diet. Biogerontological understanding of ageing has identified food as one of the three foundational pillars of health and survival. Here we address the issues of nutrition, food and diet by analyzing the biological importance of macro- and micro-nutrients including hormetins, discussing the health claims for various types of food, and by reviewing the general principles of healthy dietary patterns, including meal timing, caloric restriction, and intermittent fasting. We also present our views about the need for refining our approaches and strategies for future research on nutrition, food and diet by incorporating the molecular, physiological, cultural and personal aspects of this crucial pillar of health, healthy ageing and longevity.

1. Introduction

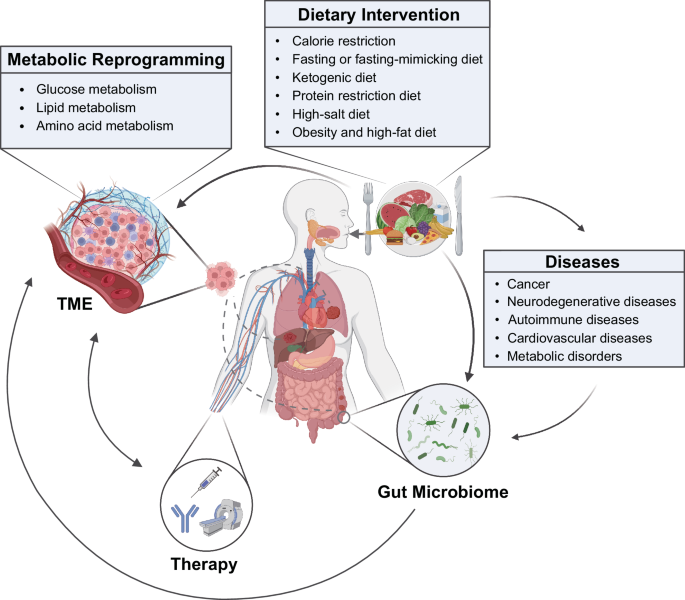

The terms nutrition, food and diet are often used interchangeably. However, whereas nutrition generally refers to the macro- and micro-nutrients essential for survival, we do not simply eat nutrition, which could, in principle, be done in the form of a pill. Instead, we eat food which normally originates from animal- and plant-based sources, without us being aware of or conscious of its nutritional value. Even more importantly, various cultural factors influence and shape our taste, preferences, taboos and practices towards preparing and consuming food as a meal and diet [ 1 ]. Furthermore, geo-political-economic factors, such as governmental policies that oversee the production and consumption of genetically modified foods, geological/climatic challenges of growing such crops in different countries, and the economic affordability of different populations for such foods, also influence dietary habits and practices [ 2 , 3 ]. On top of all this lurks the social evolutionary history of our species, previously moving towards agriculture-based societies from the hunter-gatherer lifestyle, now becoming the consumers of industrially processed food products that affect our general state of health, the emergence of diseases, and overall lifespan [ 1 , 4 ]. The aim of this article is to provide a commentary and perspective on nutrition, food and diet in the context of health, healthy ageing and longevity.

Biogerontological understanding of ageing has identified food as one of the three foundational pillars of health and survival. The other two pillars, especially in the case of human beings, are physical exercise and socio-mental engagement [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. A huge body of scientific and evidence-based information has been amassed with respect to the qualitative and quantitative nature of optimal nutrition for human health and survival. Furthermore, a lot more knowledge has developed regarding how different types of foods provide different kinds of nutrition to different extents, and how different dietary practices have either health-beneficial or health-harming effects.

Here we endeavor to address these issues of nutrition, food and diet by analyzing the biological importance of macro- and micro-nutrients, and by discussing the health-claims about animal-based versus plant-based foods, fermented foods, anti-inflammatory foods, functional foods, foods for brain health, and so on. Finally, we discuss the general principles of healthy dietary patterns, including the importance of circadian rhythms, meal timing, chronic caloric restriction (CR), and intermittent fasting for healthy ageing and extended lifespan [ 8 , 9 ]. We also present our views about the need for refining our approaches and strategies for future research on nutrition, food and diet by incorporating the molecular, physiological, cultural and personal aspects of this crucial pillar of health, healthy ageing and longevity.

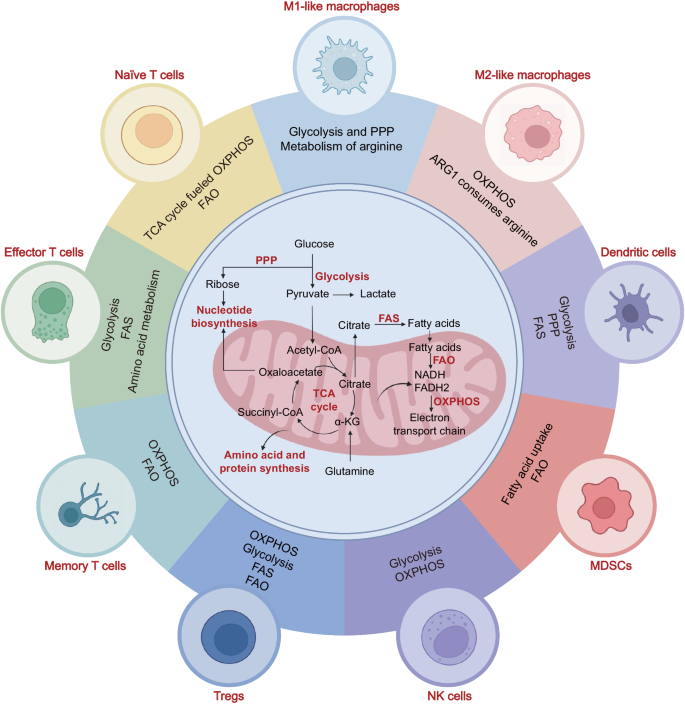

2. Nutrition for Healthy Ageing

The science of nutrition or the “nutritional science” is a highly advanced field of study, and numerous excellent books, journals and other resources are available for fundamental information about all nutritional components [ 10 ]. Briefly, the three essential macronutrients which provide the basic materials for building biological structures and for producing energy required for all physiological and biochemical processes are proteins, carbohydrates and lipids. Additionally, about 18 micronutrients, comprised of minerals and vitamins, facilitate the optimal utilization of macronutrients via their role in the catalysis of numerous biochemical processes, in the enhancement of their bioavailability and absorption, and in the balancing of the microbiome. Scientific literature is full of information about almost all nutritional components with respect to their importance and role in basic metabolism for survival and health throughout one’s life [ 10 ].

In the context of ageing, a major challenge to maintain health in old age is the imbalanced nutritional intake resulting into nutritional deficiency or malnutrition [ 11 , 12 ]. Among the various reasons for such a condition is the age-related decline in the digestive and metabolic activities, exacerbated by a reduced sense of taste and smell and worsening oral health, including the ability to chew and swallow [ 13 , 14 ]. Furthermore, an increased dependency of the older persons on medications for the management or treatment of various chronic conditions can be antagonistic to certain essential nutrients. For example, long term use of metformin, which is the most frequently prescribed drug against Type 2 diabetes, reduces the levels of vitamin B12 and folate in the body [ 15 , 16 ]. Some other well-known examples of the drugs used for the management or treatment of age-related conditions are cholesterol-lowering medicine statin which can cause coenzyme Q10 levels to be too low; various diuretics (water pills) can cause potassium levels to be too low; and antacids can decrease the levels of vitamin B12, calcium, magnesium and other minerals [ 15 , 16 ]. Thus, medications used in the treatment of chronic diseases in old age can also be “nutrient wasting” or “anti-nutrient” and may cause a decrease in the absorption, bioavailability and utilization of essential micronutrients and may have deleterious effects to health [ 11 ]. In contrast, many nutritional components have the potential to interact with various drugs leading to reduced therapeutic efficacy of the drug or increased adverse effects of the drug, which can have serious health consequences. For example, calcium in dairy products like milk, cheese and yoghurt can inhibit the absorption of antibiotics in the tetracycline and quinolone class, thus compromising their ability to treat infection effectively. Some other well-known examples of food sources which can alter the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of various drugs are grape fruits, bananas, apple juice, orange juice, soybean flour, walnuts and high-fiber foods (see: https://www.aarp.org/health/drugs-supplements/info-2022/food-medication-interaction.html (accessed on 13 November 2022)).

It is also known that the nutritional requirements of older persons differ both qualitatively and quantitatively from young adults [ 11 ]. This is mainly attributed to the age-related decline in the bioavailability of nutrients, reduced appetite, also known as ‘anorexia of ageing,’ as well as energy expenditure [ 12 , 17 , 18 ]. Therefore, in order to maintain a healthy energy balance, the daily uptake of total calories may need to be curtailed without adversely affecting the nutritional balance. This may be achieved by using nutritional supplements with various vitamins, minerals and other micronutrients, without adding to the burden of total calories [ 12 , 17 , 18 ]. More recently, the science of nutrigenomics (how various nutrients affect gene expression), and the science of nutrigenetics (how individual genetic variations respond to different nutrients) are generating novel and important information on the role of nutrients in health, survival and longevity.

3. Food for Healthy Ageing

The concept of healthy ageing is still being debated among biogerontologists, social-gerontologists and medical practioners. It is generally agreed that an adequate physical and mental independence in the activities of daily living can be a pragmatic definition of health in old age [ 7 ]. Thus, healthy ageing can be understood as a state of maintaining, recovering and enhancing health in old age, and the foods and dietary practices which facilitate achieving this state can be termed as healthy foods and diets.

From this perspective, although nutritional requirements for a healthy and long life could be, in principle, fulfilled by simply taking macro- and micro-nutrients in their pure chemical forms, that is not realistic, practical, attractive or acceptable to most people. In practice, nutrition is obtained by consuming animals and plants as sources of proteins, carbohydrates, fats and micronutrients. There is a plethora of tested and reliable information available about various food sources with respect to the types and proportion of various nutrients present in them. However, there are still ongoing discussions and debates as to what food sources are best for human health and longevity [ 19 , 20 ]. Often such discussions are emotionally highly charged with arguments based on faith, traditions, economy and, more recently, on political views with respect to the present global climate crisis and sustainability.

Scientifically, there is no ideal food for health and longevity. Varying agricultural and food production practices affect the nutritional composition, durability and health beneficial values of various foods. Furthermore, the highly complex “science of cooking” [ 21 ], evolved globally during thousands of years of human cultural evolution, has discovered the pros and cons of food preparation methods such as soaking, boiling, frying, roasting, fermenting and other modes of extracting, all with respect to how best to use these food sources for increasing the digestibility and bioavailability of various nutrients, as well as how to eliminate the dangers and toxic effects of other chemicals present in the food.

The science of food preparation and utilization has also discovered some paradoxical uses of natural compounds, especially the phytochemicals such as polyphenols, flavonoids, terpenoids and others. Most of these compounds are produced by plants as toxins in response to various stresses, and as defenses against microbial infections [ 22 , 23 ]. However, humans have discovered, mostly by trial and error, that numerous such toxic compounds present in algae, fungi, herbs and other sources can be used in small doses as spices and condiments with potential benefits of food preservation, taste enhancement and health promotion [ 23 ].

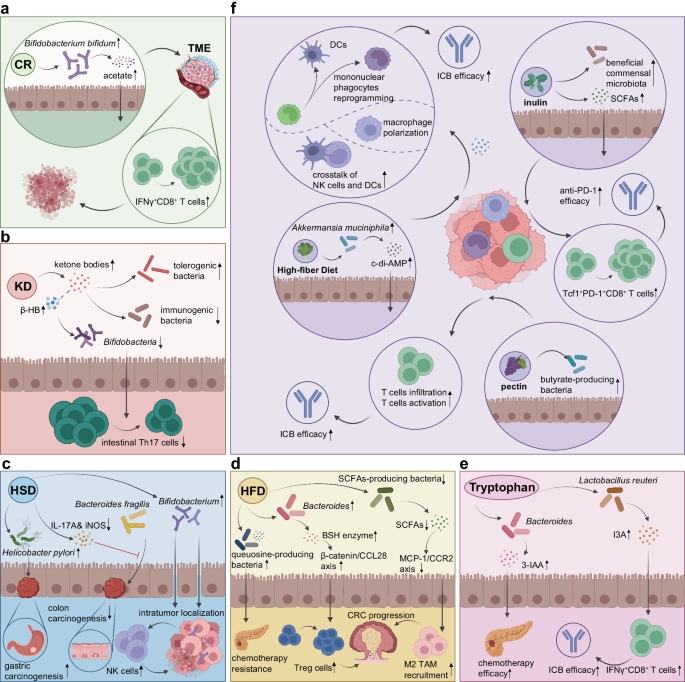

The phenomenon of “physiological hormesis” [ 24 ] is a special example of the health beneficial effects of phytotoxins. According to the concept of hormesis, a deliberate and repeated use of low doses of natural or synthetic toxins in the food can induce one or more stress responses in cells and tissues, followed by the stimulation of numerous defensive repair and maintenance processes [ 25 , 26 ]. Such hormesis-inducing compounds and other conditions are known as hormetins, categorized as nutritional, physical, biological and mental hormetins [ 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Of these, nutritional hormetins, present naturally in the food or as synthetic hormetins to be used as food supplements, are attracting great attention from food-researchers and the nutraceutical and cosmeceutical industry [ 27 , 30 ]. Other food supplements being tested and promoted for health and longevity are various prebiotics and probiotics strengthening and balancing our gut microbiota [ 31 , 32 , 33 ].

Recently, food corporations in pursuit of both exploiting and creating a market for healthy ageing products, have taken many initiatives in producing new products under the flagship of nutraceuticals, super-foods, functional foods, etc. Such products are claimed and marketed not only for their nutritional value, but also for their therapeutic potentials [ 10 ]. Often the claims for such foods are hyped and endorsed as, for example, anti-inflammatory foods, food for the brain, food for physical endurance, complete foods, anti-ageing foods and so on [ 34 , 35 , 36 ]. Traditional foods enriched with a variety of minerals, vitamins and hormetins are generally promoted as “functional foods” [ 37 ]. Even in the case of milk and dairy products, novel and innovative formulations are claimed to improve their functionality and health promotional abilities [ 38 ]. However, there is yet a lot to be discovered and understood about such reformulated, fortified and redesigned foods with respect to their short- and long-term effects on physiology, microbiota balance and metabolic disorders in the context of health and longevity.

4. Diet and Culture for Healthy and Long Life

What elevates food to become diet and a meal is the manner and the context in which that food is consumed [ 4 ]. Numerous traditional and socio-cultural facets of dietary habits can be even more significant than their molecular, biochemical, and physiological concerns regarding their nutritional ingredients and composition. For example, various well-known diets, such as the paleo, the ketogenic, the Chinese, the Ayurvedic, the Mediterranean, the kosher, the halal, the vegetarian, and more recently, the vegan diet, are some of the diverse expressions of such cultural, social, and political practices [ 1 ]. The consequent health-related claims of such varied dietary patterns have influenced their acceptance and adaptation globally and cross-culturally.

Furthermore, our rapidly developing understanding about how biological daily rhythms affect and regulate nutritional needs, termed “chrono-nutrition”, has become a crucial aspect of optimal and healthy eating habits [ 39 , 40 ]. A similar situation is the so-called “nutrient timing” that involves consuming food at strategic times for achieving certain specific outcomes, such as weight reduction, muscle strength, and athletic performance. The meal-timing and dietary patterns are more anticipatory of health-related outcomes than any specific foods or nutrients by themselves [ 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ]. However, encouraging people to adopt healthy dietary patterns and meal-timing requires both the availability, accessibility and affordability of food, and the intentional, cultural and behavioral preferences of the people.

Looking back at the widely varying and constantly changing cultural history of human dietary practices, one realizes that elaborate social practices, rituals and normative behaviors for obtaining, preparing and consuming food, are often more critical aspects of health-preservation and health-promotion than just the right combination of nutrients. Therefore, one cannot decide on a universal food composition and consumption pattern ignoring the history and the cultural practices and preferences of the consumers. After all, “we eat what we are”, and not, as the old adage says, “we are what we eat”.

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Food is certainly one of the foundational pillars of good and sustained health. Directed and selective evolution through agricultural practices and experimental manipulation and modification of food components have been among the primary targets for improving food quality. This is further authenticated by extensive research performed, mainly on experimental animal and cell culture model systems, demonstrating the health-promoting effects of individual nutritional components and biological extracts in the regulation, inhibition or stimulation of different molecular pathways with reference to healthy ageing and longevity [ 45 ]. Similarly, individual nutrients or a combination of a few nutrients are being tested for their potential use as calorie restriction mimetics, hormetins and senolytics [ 46 , 47 , 48 ]. However, most commonly, these therapeutic strategies follow the traditional “one target, one missile” pharmaceutical-like approach, and consider ageing as a treatable disease. Based on the results obtained from such experimental studies, the claims and promises made which can often be either naïve extrapolations from experimental model systems to human applications, or exaggerated claims and even false promises [ 49 ].

Other innovative, and possibly holistic, food- and diet-based interventional strategies for healthy ageing are adopting regimens such as caloric- and dietary-restriction, as well as time-restricted eating (TRE). Intermittent fasting (IF), the regimen based on manipulating the eating/fasting timing, is another promising interventional strategy for healthy ageing. Chrono-nutrition, which denotes the link between circadian rhythms and nutrient-sensing pathways, is a novel concept illustrating how meal timings alignment with the inherent molecular clocks of the cells functions to preserve metabolic health. TRE, which is a variant of the IF regimen, claims that food intake timing in alignment with the circadian rhythm is more beneficial for health and longevity [ 39 , 40 , 41 , 50 ]. Moreover, TRE has translational benefits and is easy to complete in the long term as it only requires limiting the eating time to 8–10 h during the day and the fasting window of 12–16 h without restricting the amount of calories consumed. Some pilot studies on the TRE regimen have reported improvement in glucose tolerance and the management of body weight and blood pressure in obese adults as well as men at risk of T2D. Meta-analyses of several pilot scale studies in human subjects suggest and support the beneficial effects of a TRE regimen on several health indicators [ 39 , 50 ]. Several other practical recommendations, based on human clinical trials have also been recommended for meeting the optimal requirements of nutrition in old age, and for preventing or slowing down the progression of metabolic syndromes [ 39 , 40 , 41 , 50 ].

What we have earlier discussed in detail [ 4 ] is supported by the following quote: “…food is more than just being one of the three pillars of health. Food is both the foundation and the scaffolding for the building and survival of an organism on a daily basis. Scientific research on the macro- and micro-nutrient components of food has developed deep understanding of their molecular, biochemical and physiological roles and modes of action. Various recommendations are repeatedly made and modified for some optimal daily requirements of nutrients for maintaining and enhancing health, and for the prevention and treatment of diseases. Can we envisage developing a “nutrition pill” for perfect health, which could be used globally, across cultures, and at all ages? We don’t think so” [ 4 ].

Our present knowledge about the need and significance of nutrients is mostly gathered from the experimental studies using individual active components isolated from various food sources. In reality, however, these nutritional components co-exist interactively with numerous other compounds, and often become chemically modified through the process of cooking and preservation, affecting their stability and bioavailability. There is still a lot to be understood about how the combination of foods, cooking methods and dietary practices affect health-related outcomes, especially with respect to ageing and healthspan.

An abundance of folk knowledge in all cultures about food-related ‘dos and don’ts’ requires scientific verification and validation. We also need to reconsider and change our present scientific protocols for nutritional research, which seem to be impractical for food and dietary research at the level of the population. It is a great scientific achievement that we have amassed a body of information with respect to the nature of nutritional components required for health and survival, the foods which can provide those nutritional components and the variety of dietary and eating practices which seem to be optimal for healthy survival and longevity.