25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

Essay on Sustainable Development: Samples in 250, 300 and 500 Words

- Updated on

- Nov 18, 2023

On 3rd August 2023, the Indian Government released its Net zero emissions target policy to reduce its carbon footprints. To achieve the sustainable development goals (SDG) , as specified by the UN, India is determined for its long-term low-carbon development strategy. Selfishly pursuing modernization, humans have frequently compromised with the requirements of a more sustainable environment.

As a result, the increased environmental depletion is evident with the prevalence of deforestation, pollution, greenhouse gases, climate change etc. To combat these challenges, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change launched the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) in 2019. The objective was to improve air quality in 131 cities in 24 States/UTs by engaging multiple stakeholders.

‘Development is not real until and unless it is sustainable development.’ – Ban Ki-Moon

The concept of Sustainable Development in India has even greater relevance due to the controversy surrounding the big dams and mega projects and related long-term growth. Since it is quite a frequently asked topic in school tests as well as competitive exams , we are here to help you understand what this concept means as well as the mantras to drafting a well-written essay on Sustainable Development with format and examples.

This Blog Includes:

What is sustainable development, 250-300 words essay on sustainable development, 300 words essay on sustainable development, 500 words essay on sustainable development, introduction, conclusion of sustainable development essay, importance of sustainable development, examples of sustainable development.

As the term simply explains, Sustainable Development aims to bring a balance between meeting the requirements of what the present demands while not overlooking the needs of future generations. It acknowledges nature’s requirements along with the human’s aim to work towards the development of different aspects of the world. It aims to efficiently utilise resources while also meticulously planning the accomplishment of immediate as well as long-term goals for human beings, the planet as well and future generations. In the present time, the need for Sustainable Development is not only for the survival of mankind but also for its future protection.

Looking for ideas to incorporate in your Essay on Sustainable Development? Read our blog on Energy Management – Find Your Sustainable Career Path and find out!

To give you an idea of the way to deliver a well-written essay, we have curated a sample on sustainable development below, with 250-300 words:

To give you an idea of the way to deliver a well-written essay, we have curated a sample on sustainable development below, with 300 + words:

Must Read: Article Writing

To give you an idea of the way to deliver a well-written essay, we have curated a sample on sustainable development below, with 500 + words:

Essay Format

Before drafting an essay on Sustainable Development, students need to get familiarised with the format of essay writing, to know how to structure the essay on a given topic. Take a look at the following pointers which elaborate upon the format of a 300-350 word essay.

Introduction (50-60 words) In the introduction, students must introduce or provide an overview of the given topic, i.e. highlighting and adding recent instances and questions related to sustainable development. Body of Content (100-150 words) The area of the content after the introduction can be explained in detail about why sustainable development is important, its objectives and highlighting the efforts made by the government and various institutions towards it. Conclusion (30-40 words) In the essay on Sustainable Development, you must add a conclusion wrapping up the content in about 2-3 lines, either with an optimistic touch to it or just summarizing what has been talked about above.

How to write the introduction of a sustainable development essay? To begin with your essay on sustainable development, you must mention the following points:

- What is sustainable development?

- What does sustainable development focus on?

- Why is it useful for the environment?

How to write the conclusion of a sustainable development essay? To conclude your essay on sustainable development, mention why it has become the need of the hour. Wrap up all the key points you have mentioned in your essay and provide some important suggestions to implement sustainable development.

The importance of sustainable development is that it meets the needs of the present generations without compromising on the needs of the coming future generations. Sustainable development teaches us to use our resources in the correct manner. Listed below are some points which tell us the importance of sustainable development.

- Focuses on Sustainable Agricultural Methods – Sustainable development is important because it takes care of the needs of future generations and makes sure that the increasing population does not put a burden on Mother Earth. It promotes agricultural techniques such as crop rotation and effective seeding techniques.

- Manages Stabilizing the Climate – We are facing the problem of climate change due to the excessive use of fossil fuels and the killing of the natural habitat of animals. Sustainable development plays a major role in preventing climate change by developing practices that are sustainable. It promotes reducing the use of fossil fuels which release greenhouse gases that destroy the atmosphere.

- Provides Important Human Needs – Sustainable development promotes the idea of saving for future generations and making sure that resources are allocated to everybody. It is based on the principle of developing an infrastructure that is can be sustained for a long period of time.

- Sustain Biodiversity – If the process of sustainable development is followed, the home and habitat of all other living animals will not be depleted. As sustainable development focuses on preserving the ecosystem it automatically helps in sustaining and preserving biodiversity.

- Financial Stability – As sustainable development promises steady development the economies of countries can become stronger by using renewable sources of energy as compared to using fossil fuels, of which there is only a particular amount on our planet.

Mentioned below are some important examples of sustainable development. Have a look:

- Wind Energy – Wind energy is an easily available resource. It is also a free resource. It is a renewable source of energy and the energy which can be produced by harnessing the power of wind will be beneficial for everyone. Windmills can produce energy which can be used to our benefit. It can be a helpful source of reducing the cost of grid power and is a fine example of sustainable development.

- Solar Energy – Solar energy is also a source of energy which is readily available and there is no limit to it. Solar energy is being used to replace and do many things which were first being done by using non-renewable sources of energy. Solar water heaters are a good example. It is cost-effective and sustainable at the same time.

- Crop Rotation – To increase the potential of growth of gardening land, crop rotation is an ideal and sustainable way. It is rid of any chemicals and reduces the chances of disease in the soil. This form of sustainable development is beneficial to both commercial farmers and home gardeners.

- Efficient Water Fixtures – The installation of hand and head showers in our toilets which are efficient and do not waste or leak water is a method of conserving water. Water is essential for us and conserving every drop is important. Spending less time under the shower is also a way of sustainable development and conserving water.

- Sustainable Forestry – This is an amazing way of sustainable development where the timber trees that are cut by factories are replaced by another tree. A new tree is planted in place of the one which was cut down. This way, soil erosion is prevented and we have hope of having a better, greener future.

Related Articles

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a set of 17 global goals established by the United Nations in 2015. These include: No Poverty Zero Hunger Good Health and Well-being Quality Education Gender Equality Clean Water and Sanitation Affordable and Clean Energy Decent Work and Economic Growth Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure Reduced Inequality Sustainable Cities and Communities Responsible Consumption and Production Climate Action Life Below Water Life on Land Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions Partnerships for the Goals

The SDGs are designed to address a wide range of global challenges, such as eradicating extreme poverty globally, achieving food security, focusing on promoting good health and well-being, inclusive and equitable quality education, etc.

India is ranked #111 in the Sustainable Development Goal Index 2023 with a score of 63.45.

Hence, we hope that this blog helped you understand the key features of an essay on sustainable development. If you are interested in Environmental studies and planning to pursue sustainable tourism courses , take the assistance of Leverage Edu ’s AI-based tool to browse through a plethora of programs available in this specialised field across the globe and find the best course and university combination that fits your interests, preferences and aspirations. Call us immediately at 1800 57 2000 for a free 30-minute counselling session

Team Leverage Edu

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Thanks a lot for this important essay.

NICELY AND WRITTEN WITH CLARITY TO CONCEIVE THE CONCEPTS BEHIND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY.

Thankyou so much!

Leaving already?

8 Universities with higher ROI than IITs and IIMs

Grab this one-time opportunity to download this ebook

Connect With Us

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

September 2024

January 2025

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

India behind on progress toward UN Sustainable Development Goals

March 2, 2023—India is not on target to reach more than half of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—a broad set of global goals set in 2015 by UN member states—by the organization’s 2030 deadline, according to a study led by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The study was published in The Lancet Regional Health–Southeast Asia on February 20, 2023. First author was S.V. Subramanian , professor of population health and geography at Harvard Chan School and principal investigator at Harvard University’s Geographic Insights Lab ; other co-authors affiliated with the lab included Rockli Kim , co-principal investigator, and Akhil Kumar, research intern.

The researchers used data from India’s 2016 and 2021 National Family Health Survey to assess progress toward nine out of 17 SDGs by looking at 33 indicators related to health and social determinants of health. Assessing how the indicators changed from 2016 to 2021, the researchers classified 707 districts across India—as well as the nation as a whole—as either achieved, on target, or off target to meeting the SDGs by 2030.

Nationally, India is off target for 19 of the 33 SDG indicators, the study found. And for critical indicators—including access to basic services, wasting and overweight children , anemia, child marriage, partner violence , tobacco use, and modern contraceptive use— more than 75% of districts were off target. There’s been no progress made on anemia, for example, and progress toward other goals is slow. The researchers estimated that India is only a year away from meeting the target for improved water access but that other targets, such as those regarding access to basic services and partner violence, could take until 2062 to reach.

Based on the findings, the study authors recommended that a strategic roadmap be developed toward four particular SDGs: No Poverty, Zero Hunger, Good Health and Wellbeing, and Gender Equality.

“Meeting [the SDGs] would require prioritizing and targeting specific areas within India,” the researchers wrote. “India’s emergence and sustenance as a leading economic power depends on meeting some of the more basic health and social determinants of health-related SDGs in an immediate and equitable manner.”

Read an article in The Hindu: India likely to miss deadline for 50% of SDG indicators: Lancet study

Read the study: Progress on Sustainable Development Goal indicators in 707 districts of India: a quantitative mid-line assessment using the National Family Health Surveys, 2016 and 2021

- Open access

- Published: 21 November 2022

India's achievement towards sustainable Development Goal 6 (Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all) in the 2030 Agenda

- Sourav Biswas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2715-2704 1 ,

- Biswajit Dandapat 2 ,

- Asraful Alam 3 &

- Lakshminarayan Satpati 4

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 2142 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

7 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Clean water and sanitation are global public health issues. Safe drinking water and sanitation are essential, especially for children, to prevent acute and chronic illness death and sustain a healthy life. The UN General Assembly announced the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 targets for the 2030 Agenda on 25 September 2015. SDG 6 is very important because it affects other SDG (1, 2,3,5,11,14 and 15). The present study deals with the national and state-wise analysis of the current status and to access deficiency of India's achievement towards SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation for all) for the 2030 agenda based on targets 6.1, 6.2,6.4,6.6 from 2012 to 2020.

Materials and methods

Data of different indicators of SDG 6 are collected from different secondary sources—NSS 69th (2012) and 76th (2018) round; CGWB annual report 2016–2017 and 2018-2019; NARSS (2019–2020); SBM-Grameen (2020). To understand overall achievement towards SDG 6 in the 2030 agenda, the goal score (arithmetic mean of normalised value) has been calculated.

Major findings

According to NSS data, 88.7% of Indian households had enough drinking water from primary drinking water sources throughout the year, while 79.8% of households had access to toilet facilities in 2018. As per the 2019–2021 goal score for States and UTs in rural India based on SDG 6 indicator, SDG 6 achiever States and UTs (100%) are Sikkim, Himachal Pradesh, Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

Drinking water and sanitation for all ensure a healthy life. It is a matter of concern for the government, policymakers, and people to improve the condition where the goal score and indicator value of SDG 6 are low.

Peer Review reports

Clean Water and sanitation are global public health issues. "Water collected from sources like—piped water into dwelling, piped water into yard/plot, household connection, public standpipes/tap, boreholes/tube well, protected dug wells, protected springs and rainwater collection and bottled water are considered as improved sources of drinking water. Drinking water collected from improved sources located on-premises, available when needed and free from faecal and contamination is known as safely managed drinking water" [ 1 ]. "Hygiene refers to conditions and practices that help maintain health and prevent the spread of diseases” [ 2 ]. Water, sanitation and hygiene are known as WASH. WASH includes the use of safe drinking water; safe disposal and management of human faecal matter, human waste (solid and liquid). Open defecation is much more common in rural India than in urban India. About 70% of the Indian population lives in rural areas. In fact, 89% of households without toilets were in rural areas, according to the 2011 census. Although the Indian government has spent decades building latrines and the country has had consistent economic progress, rural open defecation statistics have remained stubbornly high [ 3 ].Control of vector-borne diseases, handwashing practices. Open Defecation Free (ODF) is the termination of faecal-oral transmission in an open space or ending open defecation using a toilet. India has progressed in access to safe drinking water (tap/hand-pump/tube well) in the household from 38% in 1981 to 85.5% in 2011. Water, sanitation, and hygiene-related diseases are Infectious Diarrhoea, Typhoid and paratyphoid fevers, Acute hepatitis A, Acute hepatitis E and future F, Fluorosis, Arsenosis, Legionellosis, Methamoglobinamia, Schistosomiasis, Trachomaa, Ascariasis, Trichuriasis, Hookworm, Dracunculiasis, Scabies, Dengue, Filariasis, Malaria, Japanese encephalitis, Leishmaniasis, Onchocerciasisa, Yellow fever, Impetigo and Drowning [ 4 ]. The United Nations General Assembly declared 2008 the International Year of Sanitation to recognise the critical need for increased political awareness and action on sanitation. The purpose is to promote awareness and speed up progress toward the Millennium Development Goal of decreasing the proportion of people without access to basic sanitation by 2015. Due to poor sanitation, people suffer from bad health, lost income, inconvenience, and indignity. Despite this, billions of people worldwide do not have access to basic sanitation [ 4 , 5 ]. According to WHO (2015), 2.4 billion people lack sanitation facilities, and 663 million people still lack access to safe and clean drinking water facilities [ 6 ]. WHO (2019) state that 3.3% of global death and 4.6% of DALYs is attributed to inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene condition. "Unsafe sanitation is responsible for 775,000 deaths per year, 5% death in low-income countries due to unsafe sanitation, 15% of the world still practising open defecation [ 7 ]. "Age-standardized death rate attributable to unsafe water, sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH) (per 100,000 population) 268.587 in 1990, 239.719 in 1995, 210.642 in 2000, 180.757 in 2005, 143.453 in 2010 and 104.202 in 2016″ [ 7 ]. So safe drinking water and sanitation are essential, especially for children, to prevent acute and chronic illness death and sustain a healthy life. After the Millennium Development goal, on 25 September 2015, in UN general assembly 17th sustainable development goal (SDG) and 169 targets set up for 2030 agenda [ 8 , 9 ]. "SDG 6 is essential because it affects other SDG (1 – poverty eradication, 2 – ending hunger, 3 – healthy life and well–being, 4 – quality education, 5 – gender equality, 11 – inclusive cities, 14 – life below water and 15 – terrestrial ecosystem)" [ 10 ]. The present study deals with the national and state-wise analysis of current status and to access deficiency of India's Achievement towards SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation for all) for the 2030 agenda based on targets 6.1, 6.2, 6.4, 6.6 from 2012 to 2020. In this study, special focus is given to rural India.

Census of India continuously collecting data about drinking water and sanitation from all households in house listing and housing. “The National Statistical Office (NSO) Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation” (MOSPI), Government of India has been collecting data on housing condition, drinking water, sanitation and hygiene; those were collected by NSO from NSS 7th round (October 1953—March 1954) to NSS 23rd round (July 1968—June 1969), 28th round (October 1973—June 1974), 44th round (July 1988—June 1989), 49th round (January—June 1993), 54th round (January—June 1998) 58th round (July—December 2002), 65th round (July 2008—June 2009), 69th round (July—December 2012), and latest NSS 76th round. The Indian government has undertaken attempts to enhance drinking water and sanitation.

1949: The Environment Hygiene Committee advises that a clean water supply be provided to 90% of India's population within a 40-year timeframe.

1969: The National Rural Drinking Water Supply Program was initiated with UNICEF's technical assistance, and Rs.254.90 crore is spent on 1.2 million bore wells and 17,000 piped water supply systems during this phase.

In 1972–73, the Government of India launched the Accelerated Rural Water Supply Programme (ARWSP) to assist states and union territories in expanding drinking water supply coverage.

1986: The National Drinking Water Mission (NDWM) was established. The National Drinking Water Mission was renamed the Rajiv Gandhi National Drinking Water Mission in 1991 (RGNDWM). The 73rd Constitutional Amendment mandates the provision of drinking water by Panchayati Raj institutions (PRIs).

In 1986, the Central Rural Sanitation Programme (CRSP) was established to provide safe sanitation in rural regions. The Total Sanitation Campaign (TSC) was launched in 1999 to promote local sanitary marts and various technical choices to develop supply-led sanitation.

1999: The Total Sanitation Campaign (TSC) was launched in 1999 as part of the reform principles to provide sanitation facilities in rural regions to eliminate open defecation. Swajal Dhara, a national scale-up of sector reform, was launched in 2002. All drinking water programmers were placed under the RGNDWM's umbrella in 2004.

2005: The Indian government begins the Bharat Nirman Programme, aiming to improve housing, roads, power, telephone, irrigation, and drinking water infrastructure in rural regions [ 11 ].

In 2009, the ARWSP was renamed the National Rural Drinking Water Programme (NRDWP). One of the goals was to allow all households, to the extent practicable, to have access to and utilise safe and adequate drinking water inside the premises.

In 2012, The Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan was reformed and renamed (rural sanitation).

The Swachh Bharat Mission was launched across the country on 2 October 2014 to achieve the objective of a clean India by 2 October 2019. (PM India).

The current National Rural Drinking Water Programme (NRDWP) was reformed and incorporated under Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) on 15 August 2019 to provide Functional Household Tap Connection (FHTC) to every rural household, i.e. Har Ghar Nal Se Jal (HGNSJ) by 2024. Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) is a non-profit organisation.

The goals of SBM(Gmain) are to enhance the general quality of life in rural areas by fostering cleanliness, hygiene, and the elimination of open defecation. The Individual Household Latrines (IHHL) unit cost was increased from Rs. 10,000 to Rs. 12,000 rupees to accommodate for water availability. To meet the Swachh Bharat aim, improve rural sanitation coverage by 2 October 2019. Raising awareness and providing health education encourages communities and Panchayati Raj institutions to adopt sustainable sanitation practices and infrastructure. Encourage the use of cost-effective and suitable sanitation methods that are environmentally safe and long-lasting. Develop community-managed sanitation systems in rural regions, concentrating on scientific Solid and Liquid Waste Management systems for overall cleanliness [ 11 , 12 ].

In New York in 2000, 189 nations approved the Millennium Declaration for 2015, promising to work together to create a safer, more prosperous, and equal world. There are eight objectives, seven of which deal with sanitation and hygiene (target 7. C – Reduce the share of the population without sustainable access to clean drinking water and basic sanitation by 2015). (Millennium Development Goal of the United Nations) Following the millennium development goal (SDG), the United Nations General Assembly approved 17 sustainable development goals and 169 targets for the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development on 25 September 2015. Out of 17 SDGs, SDG 6 ensures availability and sustainable water and sanitation management. SDG 6 has different target for the year 2030—6.1: Achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all; 6.2: Achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying particular attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations; 6.3: Improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally; 6.4: By 2030, substantially increase water-use efficiency across all sectors and ensure sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity and substantially reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity; 6.5: Implement integrated water resources management at all levels, including through transboundary cooperation as appropriate; 6.6: Protect and restore water-related ecosystems, including mountains, forests, wetlands, rivers, aquifers and lakes; 6.a: Expand international cooperation and capacitybuilding support to developing countries in water- and sanitation-related activities and programmes, including water harvesting, desalination, water efficiency, wastewater treatment, recycling and reuse technologies; 6.b: Support and strengthen the participation of local communities in improving water and sanitation management [ 8 ].

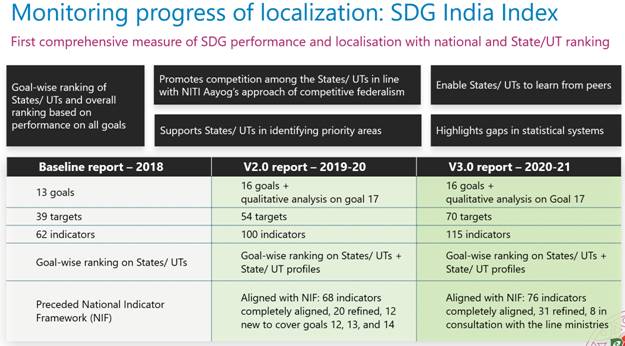

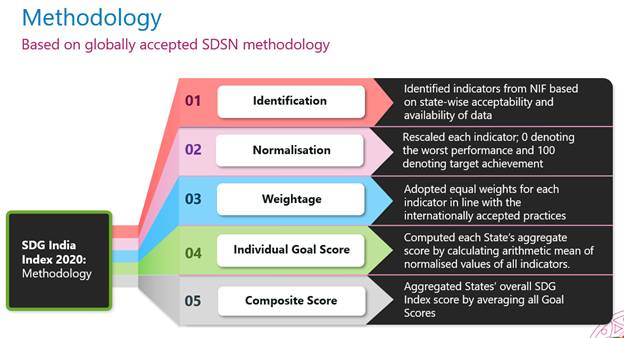

As the nodal institution for SDGs, NITI Aayog, the Government of India has striven to provide the necessary encouragement and support to forge collaborative momentum among them. Since 2018, the SDG India Index & Dashboard has worked as a powerful tool to bring SDGs clearly and firmly into the policy arena in our States and UTs [ 13 ]. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI), Government of India developed a National Indicator Framework (NIF), which is the backbone for facilitating monitoring of SDGs at the national level and provides appropriate direction to the policymakers and the implementing agencies of various schemes and programmes [ 14 ].

The main objective of this study is to find out the status of SDG target 6.1, 6.2, 6.4 and 6. towards the achievement of SDG 6 in the 2030 agenda in India (National and State level) and to assess deficiency towards the Achievement of clean Water and sanitation for all in 2030 agenda India (National and State level).

The present study is based on seven indicators of SDG 6;

a: those are % population having improved source of drinking water- SDG 6.1,

b: % of individual household toilets constructed against target (SBM(G))- SDG 6.2,

c: % of districts verified to be ODF (SBM(G))- SDG 6.2,

d: % of school has a separate toilet for boys and girls- SDG 6.2,

e: % of households having safe disposal of liquid waste- SDG 6.a,

f: % of blocks/ mandals / taluka having safe groundwater extraction—SDG 6.4, and.

g: % of blocks/ mandals / taluka over-exploited- SDG 6.4. Data of those indicators are collected from the following secondary sources:

The present study is based on percentage distribution, normalization and arithmetic mean methods. The percentage of groundwater extraction from extractable groundwater resource annually is calculated by the formula: \(\left(\frac{\mathrm{total}\;\mathrm{annual}\;\mathrm{groundwater}\;\mathrm{extraction}}{\mathrm{annual}\;\mathrm{extractable}\;\mathrm{groundwater}\;\mathrm{resource}}\times100\right)\%\) . And goal score for SDG 6 indicators is calculated by target setting, followed by normalizing the raw data of indicator arithmetic mean of the normalizing value of indicators. The methodology of goal score calculation was developed by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI) in 2019. The target of those indicators was set by United Nations at the global level. The national target value for indicator a:100%, b:100%, c:100%, d:100%, e:100%, f:100% and g:0%. The next step is normalizing the raw data. It is important to maintain a standard indicator value between 0 and 100. An indicator higher value = lower performance, following formula, was used – the normalized value of an indicator \(({N}_{V})=\left(1-\frac{\mathrm{Actual }\;\mathrm{value}\;\mathrm{of}\;\mathrm{an}\;\mathrm{indicator}\;\left(\mathrm i\right)-\mathrm{target}\;\mathrm{value}\;\mathrm{of}\;\mathrm{the}\;\mathrm{indicator}\;(\mathrm i)}{\mathrm{maximum}\;\mathrm{value}\;\mathrm{of}\;\mathrm{the}\;\mathrm{indicator}(i)-\mathrm{Target}\;\mathrm{value}\;\mathrm{of}\;\mathrm{the}\;\mathrm{indicator}\;\left(\mathrm i\right)}\right) \times100\) . Normalization does not require for indicators a, b, c, d, e & f because values of that indicator are already in percentage and g have been done using the above formula. The goal score for all indicators of SDG 6 for each state and UTs have been done by the arithmetic mean of normalized value, using the following formula- Goal score of indicator(GSI) = ( \({\sum }_{i=1}^{Ni}Nv\) and \(Av\) × \(\frac{1}{\mathrm{Ni}}\) ). Whereas Ni means = the number of non-null indicators and \(Nv\) means the normalized value of the indicator and Av means the actual value of the indicator.

Result and Discussion

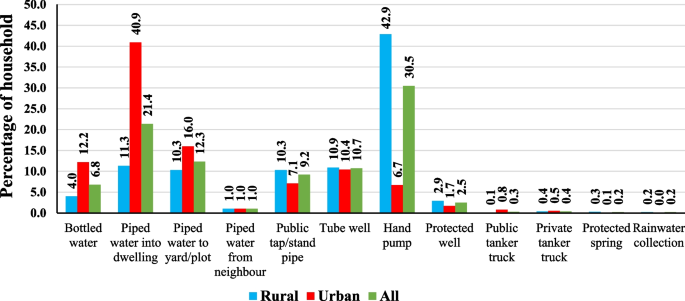

Result of households having access to Drinking Water (SDG 6.1) in India (National level and state level) as per National Sample Survey (NSS) data. Figure 1 depicts the sources of safe drinking from households accessing the drinking water throughout the year.

Percentage of households with access to principle sources of safe drinking water in India with resident type, 2018. Source: NSS 76th round (July—December 2018), graph prepared by the author. Notes: 0.0% indicate the least or negligible Percentage of household

In India 2018, most of household collect safe drinking water from hand pump (30.5%) followed by piped water into dwelling (21.4%), piped water to yard / plot (12.3%), tube well (10.7%), public tap / standpipe (9.2%), bottled water (6.8%), protected well (2.5%), piped water from neighbour (1.0%), private tanker truck (0.4%), public tanker truck (0.3%), protected spring (0.2%) and rainwater collection (0.2%). In urban areas, a higher percentage of households use piped water into the dwelling (40.9%), piped water into yard/plot (16.0%), bottled water (12.2%), public tanker truck (0.8%), private tanker track (0.5%) than a rural area. In rural area higher percentage of household using hand pump (42.9%), tube well (10.9%), public tap / standpipe (10.3%), protected well (2.9%), protected spring (0.3%) and rainwater collection (0.2%) [ 14 ].

"Bottled water, piped water into dwelling, piped water to yard/plot, public tap/standpipe, tube well/borehole, protected well, protected spring and rainwater collection are considered as improved sources of drinking water" [ 15 ]. As of 2018, 88.7% of households have access to drinking water from principal drinking water sources throughout the year, but 95.5% of household’s access improved drinking water sources in India. In contrast, the urban area has a higher percentage of access to principle (90.9%) and improved (97.4%) drinking water sources throughout the year than the rural area 87.6% and 94.5%, respectively. In India, 1.7% of principle sources and 4.9% improved drinking water sources increased from 2012 to 2018. As of 2018, 11.3% of households have a deficit in case of access principle sources of drinking water, and 4.5% of households have an obligation in case of access to improved sources of drinking water throughout the year for achieving safe and affordable drinking water for all (SDG 6.1) in 2030 agenda. Table 1 showing the percentage of households with access and deficit to drinking water with resident type in India.

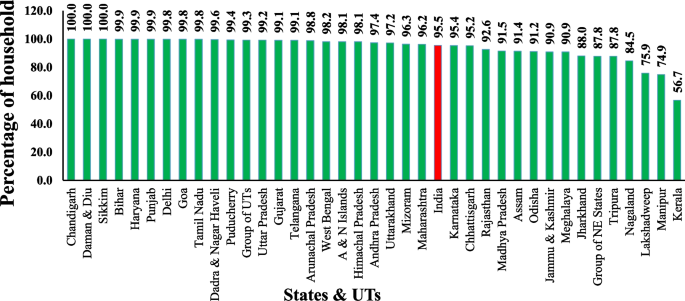

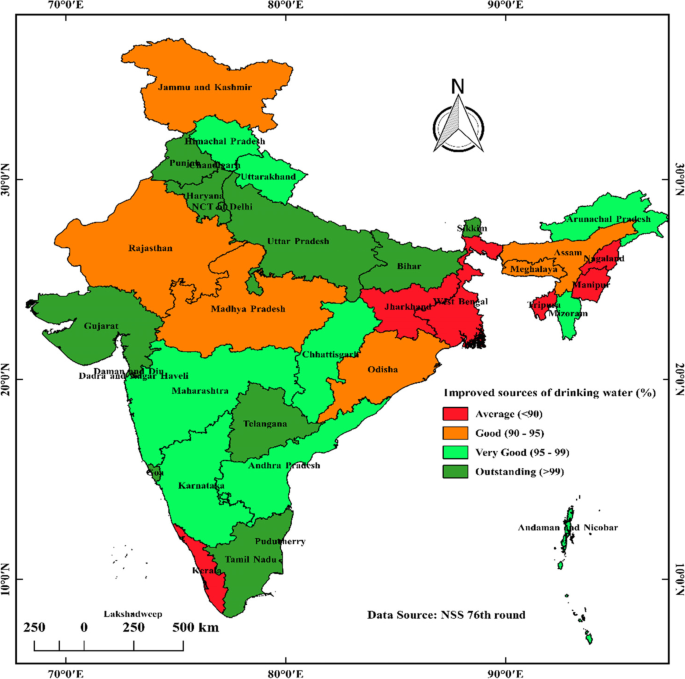

From Fig. 2 , we can say the performance of states and UTs in India towards the Achievement of SDG 6 of target SDG 6.1 by using the percentage of households having access to improved sources of drinking water indicator. As per 2018, SDG 6.1 target achiever ( 100%) states and UTs are Chandigarh, Daman and Diu, Sikkim; Front Runner (65%– 99%) States and UTs are Bihar, Haryana, Punjab, Delhi, Goa, Tamil Nadu, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Puducherry, Group of UTs, Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, Telangana, Arunachal Pradesh, West Bengal, Andaman and Nicober Islands, Himachal Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Mizoram, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Assam, Odisha, Jammu and Kashmir, Meghalaya, Jharkhand, Group of NE States, Tripura, Nagaland, Lakshadweep and Manipur; performer state (50%—64%) in Kerala. Kerala has lower access to improved safe drinking water sources. Deficit of performance to achieve SDG 6.1 target based on the above indicator for states and UTs in India are Bihar 0.1%, Haryana 0.1%, Punjab 0.1%, Delhi 0.2%, Goa 0.2%, Tamil Nadu 0.2%, Dadra and Nagar Haveli 0.4%, Puducherry 0.6%, Group of UTs 0.7%, Uttar Pradesh 0.8%, Gujarat 0.9%, Telangana 0.9%, Arunachal Pradesh 1.2%, West Bengal 1.8%, Andaman and Nicober Islands 1.9%, Himachal Pradesh 1.9%, Andhra Pradesh 2.6%, Uttarakhand 2.8%, Mizoram 3.7%, Maharashtra 3.8%, Karnataka 4.6%, Chhattisgarh 4.8%, Rajasthan 7.4%, Madhya Pradesh 8.5%, Assam 8.6%, Odisha 8.8%, Jammu and Kashmir 9.1%, Meghalaya 9.1%, Jharkhand 12%, Tripura 12.2%, Nagaland 15.5%, Lakshadweep 24.1%, Manipur 25.1% and Kerala 43.3%. Although Kerala has a higher socio-economic development performance, Kerala faces a water crisis. "Urbanisation, modernisation, increasing material prosperity, the disintegration of traditional joint family structure, pressure on land, replacing open dug well with bore well, overexploitation of groundwater contribution to the water crisis in Kerala" [ 16 ]. "Kerala received 80% less rainfall than normal after a flood. So more dry spells and drops in groundwater levels are one of the reasons for the water crisis." (V P Dineshan). In terms of households having toilet facilities, all northeastern states exceed the national average. However, except with Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim, all northeastern states are below the national average regarding access to improved drinking water sources.

Percentage of households having access to improved sources of drinking water in states & UTs in India, 2018. Source: NSS 76th round (July—December 2018), graph prepared by the author

Similarly, the percentage of villages in Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur and Meghalaya where the “Village Health and Sanitation Committee” exist is less than the national figure. Efforts should be made to form a "Village Health and Sanitation Committee" in an increasing number of villages. Financial assistance should promote family toilets and provide safe drinking water [ 17 ].

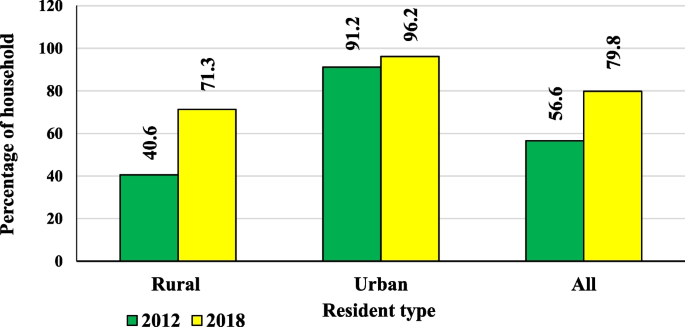

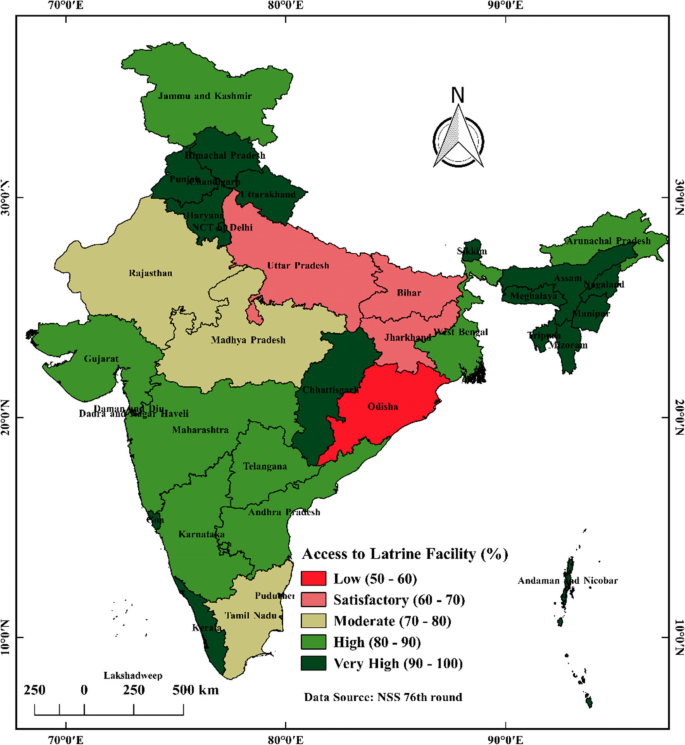

Result of households having access to latrine facility (SDG 6.2) in India (National level and state level) as per National Sample Survey (NSS) data.

As per 2018, in India, 79.8% of households have access to latrine facilities, whereas urban area has a higher percentage of household having access to latrine facility (96.2%), than rural areas (40.6%) given in the Fig. 3 . From 2012 to 2018, India had a 23.2% improvement in accessing latrine facilities, where the urban area has 5%, and the rural area has 30.7% improvement. As of 2018, in India, 20.2% of households have a deficit in accessing latrine facilities towards achieving SDG 6.2 in 2030, whereas in an urban area, it is a low deficit (3.8%) and in rural areas, it is a higher deficit (28.7%).

Percentage of households having access to latrine facility with resident type, 2012 & 2018. Sources: NSS 76th round (July—December 2018) & 69th round (July—December 2012), graph prepared by the author

As per NSS 76th round, it is seen that in 2018 in India, 2.8% of the population never used a toilet. Although households have latrine facilities, it is higher in rural areas at 3.5% and lowers in an urban area at 1.7%. The various reasons behind not using the toilet are that 2.8% there is no superstructure, 8.2% impure unclear and insufficient water, 3% malfunctioning of the latrine, 0.5% deficiency of latrines, 1.3% lack of safety, 6.3% personal preference, 0.6% cannot bear the charge of the paid latrine, and another reason is 76.9%. It is also observed that the female population uses toilets more than the male population. 74.1% of households washed their hands with water and soap/detergent, and 13.4% washed their hands with water only after defecation [ 14 ]. Infrastructure is inadequate in the rural sanitation sector that must be addressed through immediate legislative reforms and government subsidies to develop appropriate and adequate facilities [ 18 ].

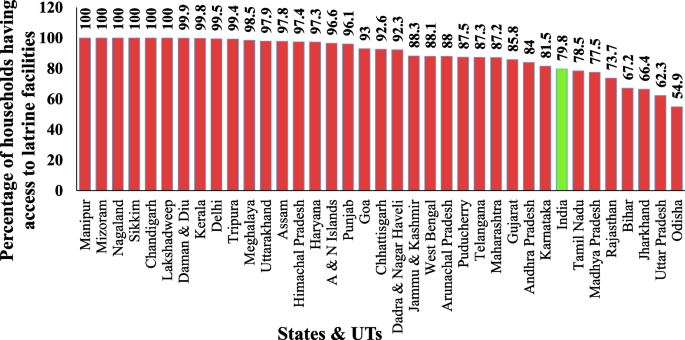

Figure 4 showing the Percentage of households having access to latrine facilities. A higher percentage of households having access to latrine facilities is found in Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, Lakshadweep, etc. A lower percentage of households below the national level are found in Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, Bihar, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. Inadequacies in rural infrastructure are undoubtedly a significant source of the 'failure.' It has multiple causes, which can be baffling at times. Government-subsidized latrines in rural areas are often inappropriate, especially for women, due to a lack of roofs, doors, walls, buried pits, and adequate spatial dimensions, each of which depends on the convenience of latrine usage and, more crucially, privacy [ 18 ]. Performance of states and UTs in India towards the Achievement of SDG 6 of target SDG 6.2 by using the percentage of households having access to latrine facility indicator.

Percentage of households having access to latrine facilities in states & UTs in India, 2018. Source:NSS 76th round (July—December 2018), graph prepared by the author

As per 2018, SDG 6.2 target achiever (100%) states and UTs are Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, Chandigarh and Lakshadweep; front runner ( 65%– 99%) states and UTs are Daman and Diu, Kerala, Delhi, Tripura, Meghalaya, Uttarakhand, Assam, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Andaman and Nicober Islands, Punjab, Goa, Chhattisgarh, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Jammu and Kashmir, West Bengal, Arunachal Pradesh, Puducherry, Telangana, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Bihar and Jharkhand; performer (50% to 64%) states are Uttar Pradesh and Odisha. As per 2018, deficit of performance towards achievement of SDG 6.2 target in 2030 agenda in States and UTs in India are Daman and Diu 0.1%, Kerala 0.2%, Delhi 0.5%, Tripura 0.6%, Meghalaya 1.5%, Uttarakhand 2.1%, Assam 2.2%, Himachal Pradesh 2.6%, Haryana 2.7%, Andaman and Nicober Islands 3.4%, Punjab 3.9%, Goa 7%, Chhattisgarh 7.4%, Dadra and Nagar Haveli 7.7%, Jammu and Kashmir 11.7%, West Bengal 11.9%, Arunachal Pradesh 12%, Puducherry 12.5%, Telangana 12.7%, Maharashtra 12.8%, Gujarat 14.2%, Andhra Pradesh 16%, Karnataka 18.5%, Tamil Nadu 21.5%, Madhya Pradesh 22.5%, Rajasthan 26.3%, Bihar 32.8%, Jharkhand 33.6%, Uttar Pradesh 37.7% and Odisha 45.1%. The result of the Percentage of blocks/mandals/talisie safe extraction of groundwater (SDG 6.4 and 6.6) in India (National level and state level) as per NSS 76 th round data. Infections and illnesses tend to be exacerbated by a lack of latrine facilities. Women and girls are usually disadvantaged due to several socio-cultural and economic factors that deny them equal rights with males. They have distinct physical needs from males, but they also have a greater need for privacy and safety regarding personal cleanliness. Actions such as going long distances in search of a good defecation site and carrying water are a sign of added load, which may be physically unpleasant and hard for women, particularly pregnant women [ 19 ].

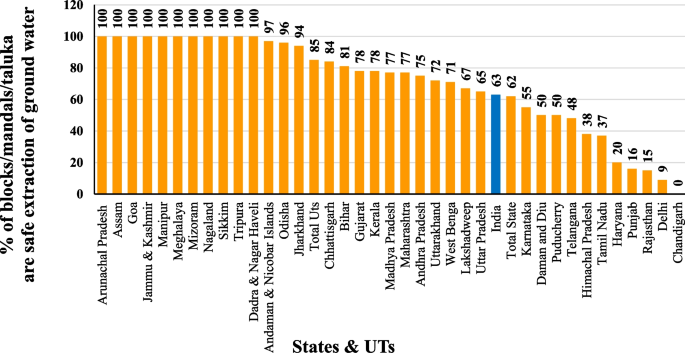

Figure 5 showing the Percentage of blocks/mandals/talisie safe extraction of groundwater. As per 2017, the performance of States and UTs in India towards the Achievement of SDG 6.4 and 6.6 in 2030 agenda based on indicator percentage of blocks/mandals/taluka are safe extraction of groundwater (groundwater extraction does not exceed the total annual groundwater recharge, which is below 70% extraction) shows achiever (100%) States and UTs are Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Goa, Jammu and Kashmir, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, Tripura, Dadra and Nagar Haveli; Front Runner (65%-99%) are Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Odisha, Jharkhand, Total UT's, Chhattisgarh, Bihar, Gujarat, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Uttarakhand, West Bengal, Lakshadweep, Uttar Pradesh; performer (50%-64%) are India, Karnataka, Daman and Diu, Puducherry; aspirant (0%-49%) are Telangana, Himachal Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Haryana, Punjab, Rajasthan, Delhi and Chandigarh. InIndia 63% blocks/mandals/taluka are safe extraction of groundwater.

Percentage of blocks/mandals/taluka are safe extraction of groundwater in States & UTs in India,2017. Source: CGWB annual report 2019–2020, graph prepared by the author

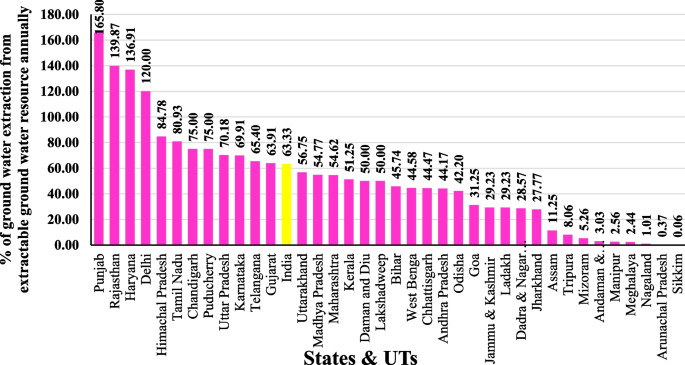

Result of the percentage of groundwater extraction (SDG 6.4) in India (National level and state level) as per 2017:

As per the "National Compilation on Dynamic Ground Water Resources of India (2017)" report by the CGWB, groundwater extraction below 70 per cent is considered a Safe extraction. Over extraction of groundwater annually (groundwater extraction exceed extractable groundwater annually) is found in Punjab (165.80%), Rajasthan (139.87%), Haryana (136.91%) and Delhi (120.00%); safe groundwater extraction is found in Karnataka, Telangana, Gujarat, India, Uttarakhand, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Kerala, Daman and Diu, Lakshadweep, Bihar, West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, Goa, Jammu and Kashmir, Ladakh, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Jharkhand, Assam, Tripura, Mizoram, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Manipur, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim. In India, 63.33% of groundwater is extracted annually as per 2017. The States and UTs with safe groundwater extraction achieve the SDG 6.4 target based on the indicator – the annual percentage of groundwater extraction from extractable groundwater resources. Figure 6 showing the Percentage of groundwater extraction from extractable groundwater resource annually in States and UTs.

Percentage of groundwater extraction from extractable groundwater resource annually in States & UTs in India,2017. Source: CGWB annual report 2019–2020, graph prepared by the author

"In India as per 2017 Total Annual Groundwater Recharge is 431.86 billion cubic meters (bcm) out of which Annual Extractable Ground Water Resource is 392.7 bcm and Current Annual Ground Water Extraction is 248. 7 bcm" (CGWB annual report 2019–2020).

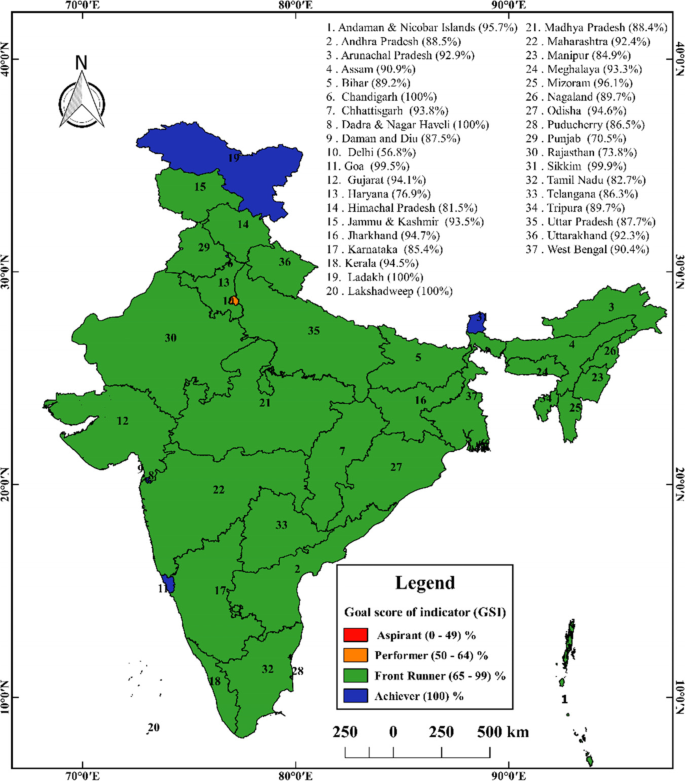

Result of the overall performance of SDG 6 in India (National level and state level) 2019 – 2021.

Table 2 shows the achievements towards SDG 6 of all States and UTs. Overall goal score of the indicator—Percentage of the rural population having improved source of drinking water (SDG 6.1), percentage of individual household toilets constructed against target (SBM(G)) (SDG 6.2), percentage of districts verified to be ODF (SBM(G)) (SDG 6.2), the school has a separate toilet for boys and girl (%) ( SDG 6.2), percentage of Household Safe Disposal of Liquid waste (SDG 6.a), percentage of blocks/ mandals/ taluka having safe groundwater extraction (SDG 6.4) and percentage of blocks/ mandals/ taluka over-exploited (6.4) reveal that states and UTs belonging in achiever stage are Chandigarh, Dadra & Nagar Haveli, Ladakh, Lakshadweep, Sikkim and Goa. The states and UTs belonging to front runner stage (66–99%) are Mizoram, Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Jharkhand, Odisha, Kerala, Gujarat, Chhattisgarh, Jammu & Kashmir, Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, Maharashtra, Uttarakhand, Assam, West Bengal, Nagaland, Tripura, Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Daman and Diu, Puducherry, Telangana, Karnataka, Manipur, Tamil Nadu, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Rajasthan and Punjab. Delhi is the only Union Territory belonging to the aspirant stage.

As per January 2021, the performance of States and UTs in Rural towards Achievement of SDG 6.1 based on indicator Percentage of the rural population having improved source of drinking water shows achiever States and UTs are; Ladakh, Sikkim, Goa, Mizoram, Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Gujarat, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Telangana, Karnataka, Manipur and Himachal Pradesh; front runner are Jammu & Kashmir, Andhra Pradesh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, Chhattisgarh, Uttar Pradesh, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Uttarakhand, Odisha, Bihar, Puducherry, West Bengal, Arunachal Pradesh, Punjab, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Tripura and Assam.

From Fig. 7 , we can see that most of the states and union territories belong to the green colour shade. That means all these states and union territories are in the Front Runner (65–99%) stage as per the Goal Score Indicator (GSI). Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Chandigarh, Dadra & Nagar Haveli, Ladakh, Lakshadweep, Sikkim and Goa are all states and Union Territories observing blue colour shade, indicating that all these states and union territories have reached the achiever stage as per the Goal Score Indicator (GSI). Delhi is the only union territory where orange colour is observed, indicating that the union territory is still at the performer (50–64%) stage.

Overall performance of different indicators of SDG 6 (Goal score of the indicator). Sources: Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Ministry of Jal Shakti, January 2021; Swachh Bharat Mission Gramin Dashboard,2020; NARSS round 3, 2019–2020; map prepared by the author

Figure 8 shows the spatial distribution of households having access to improved sources of drinking water and Fig. 9 shows the spatial distribution of households having access to latrine facilities in States and UTs in India.

Spatial distribution of households having access to improved sources of drinking water (%) in states & UTs in India, 2018. Source: NSS 76th round (July—December 2018), map prepared by the author

Spatial distribution of households having access to latrine facility (%) in states & UTs in India, 2018. Source: NSS 76th round (July—December 2018), map prepared by the author

From Fig. 8 , light green indicates states and union territories with 95–99% coverage of improved drinking water sources. Moreover, deep green indicates those states and union territories with more than 99% coverage of improved drinking water sources. The red colour indicates below 90% coverage of improved drinking water sources. Furthermore, orange indicates those states and union territories with 90–95% coverage of improved drinking water sources. All South Indian states except Kerala fall into more than 95% coverage of improved drinking water sources. Almost all States and Union Territories above and near the Tropic of Cancer have < 95% coverage of Improved Sources of Drinking Water except Chhattisgarh and Gujarat. Almost all states of North India except Jammu and Kashmir have more than 95% coverage of improved drinking water sources.

From Fig. 9 , light green indicates states and union territories with 80–90% coverage of access to latrine facilities. Moreover, deep green indicates those states and union territories with 90–100% coverage of access to latrine facilities. The red indicates below 50–60% coverage of access to latrine facilities. Furthermore, pink indicates those states and union territories with 60–70% coverage of access to latrine facilities. Whitish Grey indicates states and union territories with 70–80% coverage of access to latrine facilities. Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, and Odisha fall into less than 70% coverage of access to latrine facilities. Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Tamil Nadu are found to have 70–80% coverage of access to latrine facilities. The rest of the states and union territories have found more than 80% coverage of access to latrine facilities.As per NSS data in 2018, 30.5% of households collect safe drinking water from the hand pump; in the case of urban areas 40.9% of households use piped water into the dwelling; and in rural areas 42.9% of households use the hand pump. 88.7% of households have access to a principle source of drinking water, and 95.5% use improved drinking water sources throughout the year. 100% of households having access to improved sources of drinking water (SDG 6.1 target achiever) in Chandigarh, Daman and Diu, Sikkim and Kerala has the lowest percentage 56.7%. In India, 79.8% of households have access to latrine facilities, whereas urban area has a higher percentage of household having access to latrine facility 96.2%, than rural areas (40.6%). The female population are more using toilets than the male population. 100% of households have access to latrine facilities (SDG 6.2 target achiever) in Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, Chandigarh, Lakshadweep; and the lowest found in Odisha 54.9%. Safe groundwater extraction from extractable groundwater resources annually (SDG 6.4 target achiever) in States and UTs in India, 2017 are found in Karnataka, Telangana, Gujarat, India, Uttarakhand, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Kerala, Daman and Diu, Lakshadweep, Bihar, West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, Goa, Jammu & Kashmir, Ladakh, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Jharkhand, Assam, Tripura, Mizoram, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Manipur, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim. In India, 63.33% of groundwater is extracted annually as per 2017. As of 2020, all the States and UTs in Rural India 100% individual household toilets constructed against target (SBM(G)) and 100% districts verified to be ODF (SBM(G)) (SDG 6.2 target achiever). As per January 2021, 100% rural population has improved source of drinking water (SDG 6.1 target achiever) in Ladakh, Sikkim, Goa, Himachal Pradesh, Gujarat, Karnataka, Mizoram, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Telangana, Meghalaya, Nagaland and Manipur. As per 2019–2020, 100% school having a separate toilet for boys and girl (SDG 6.2 target achiever) in Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Sikkim, Himachal Pradesh, Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Puducherry. Goa achieves 100% safe disposal of liquid waste. Overall goal score expresses all the states belong to front runner stage (65% to 99%). Based on SDG 6.1 and SDG 6.2, it is observed that in Rural India achiever (100%) state is Sikkim, Himachal Pradesh, Andaman and Nicobar Islands in 2019–2021.Since the population is increasing, the number of sustainable water resources is not. Future population expansion will likely result in further reduced renewable water available per capita. Most changes in India's overall and rural regions, moderate changes in the world's overall and rural areas, and very little change in both India's and the world's urban areas have been seen in terms of access to essential drinking water services [ 20 ]. The top eight states are Gujarat, Jammu & Kashmir, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Telangana; the bottom eight are Delhi, Uttarakhand, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Kerala, and West Bengal. Due to their location in the Ganges basin, most of the eight lowest performing states have abundant water resources, in contrast to the higher performing states, which are comparatively water scarce. Severe droughts have recently affected Gujarat, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Telangana. From an endowment standpoint, this focuses the attention of water concerns in India toward improved management and control of water resources. The top five states in terms of performance are Goa, Delhi, Kerala, Gujarat, and Telangana, whereas the worst five are Chhattisgarh, Bihar, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, and Jharkhand. In Jharkhand, Bihar, and Uttar Pradesh, childhood malnutrition and stunting have increased due to poor sanitation services. Individually, these indices point to significant disparities in access to sanitary facilities and clean water throughout the states. Few states have been able to implement comprehensive planning to meet the key objectives [ 21 , 22 ].

The WHO/UNICEF, joint monitoring program estimated in 2012 that 60% of the world's open defecation occurs in India. While this trend is declining rapidly in other countries, it continues stubbornly in India. According to the 2011 Census of India data, about 90% of rural people in India defecate in the open. Social context always plays a vital role in countries like India, where households with higher income and better education are more likely to use latrines and toilets. Previous research has shown that Muslims are 25% less likely to defecate in the open than Hindus. Although Hindus have 6% more per capita consumption than non-Hindus, Hindus are less likely to use latrines [ 23 ].

Open defecation at the individual level is a more accurate reflection of the disease environment than latrine ownership at the household level. It is particularly true in rural India, where earlier research has shown that many residents of homes with latrines do not use their latrines. The literature indicates that the Indian government's policy of subsidizing pit latrines has not achieved large-scale behaviour change and may still represent a misguided focus. This policy has continued mainly under the current Swachh Bharat Mission (2014–present). Despite the evidence, understanding latrine demand is critical to understanding latrine uptake [ 24 , 25 ]. Sanitation practices and social norms receive minimal consideration in sanitation programmes. Sanitation policy would probably be more effective if it addressed the underlying social environment in which judgments about where to defecate and what kind of latrine is socially acceptable since even the well-educated and wealthiest households adopt latrines at such a slow pace [ 26 ].

After lunch of Swachh Bharat Mission and other programmes related to sanitation and drinking water, sanitation coverage and accessibility of drinking water rise which has reinforcement substantially in accelerating the Achievement of Sustainable Development goal 6. States and UTs having the lower status of sanitation, drinking water, groundwater and hygiene need to improve those condition by increasing availability, accessibility and affordability of the WASH facility. Localisation or bottom-up approach by giving responsibility to rural and urban local body enforced Achievement of SDG 6. Total water withdrawal per capita was 576.96 m 3 in 1975, which was 602.3 m 3 in 2010. Total water withdrawal has increased by about 3.07% in these few decades. From 1962 to 2014, 64.29% per capita of total internal renewable water resources decreased. From 1979 to 2011, 18.4% increase in water stress. To fulfil essential human needs and attain sustainable development aims, central and local governments must collaborate. These initiatives and actions for recyclable and reusable, sufficient, and treated water, as well as enhancing sanitation and hygiene infrastructure, are linked to creating opportunities that improve economic sustainability. Additionally, establishing sanitation, hygiene and drinking water infrastructure in households grants social dignity, which can assist in social sustainability.

Those States and Union Territories that have not achieved the goal of 100% overall SDG-6 should fulfil the goals through a specific regional development approach. If successful locally, it will help the country's overall progress on a large scale. India and other underdeveloped and developing countries need to fulfil the goals of SDG-6. If successful in achieving the target, it will accelerate overall health improvement and help reduce regional disparities. Developed countries need to help developing and underdeveloped countries. Finally, the various organizations of the United Nations should try to solve the problems at the local level through each country-specific regional approach that will accelerate the overall achievement.

To prevent and reduce acute and chronic illness death and sustain a healthy life, we need to increase awareness and facilities to access safe and adequate drinking water, sanitation and hygiene. For raising awareness, different days are celebrated on 22 March as World Water Day for Water, 19 November as World Toilet Day for sanitation and 15 October as Global Handwashing Day for hygiene. Still, we need to maintain safe drinking water, sanitation and hygiene all day.

Availability of data and materials

The study is based on secondary data analysis. No data was collected for this study. The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the NSS (Download Reports | Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation | Government Of India), Central ground water control board (Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation, GOI (jalshakti-ddws.gov.in)), NARSS (Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation, GOI (jalshakti-ddws.gov.in)) NITI Aayog (Reports on SDG | NITI Aayog) repository.

Abbreviations

National Sample Survey

Sustainable Development Goals

Foundation THE, Safe FOR, Care PH, Wash B, Factor THEL, Issue THEQ, et al. WHO / UNICEF Report : Water, Sanitation and Hygiene in Health Care Facilities : status in low-and middle-income countries and way forward 10 Key Findings. Who. 2016;7–8.

Prüss-Ustün A, Wolf J, Bartram J, Clasen T, Cumming O, Freeman MC, et al. Burden of disease from inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene for selected adverse health outcomes: an updated analysis with a focus on low-and middle-income countries. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2019;222(5):765–77.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Coffey D, Gupta A, Hathi P, Khurana N, Spears D, Srivastav N, et al. Revealed preference for open defecation: Evidence from a new survey in rural north India.” forthcoming in Economic and Political Weekly (special articles section). 2014;

Prüss A, Kay D, Fewtrell L, Bartram J. Estimating the burden of disease from water, sanitation, and hygiene at a global level. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(5):537–42.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Apostolidis N. 2008 International year of sanitation. Water. 2008;35(3):10.

Google Scholar

Masanyiwa ZS, Zilihona IJE, Kilobe BM. Users’ perceptions on drinking water quality and household water treatment and storage in small towns in Northwestern Tanzania. Open J Soc Sci. 2019;7(01):28.

Ritchie H, Roser M. Clean water. Our World Data. 2019;

Ritchie H, Roser M. Clean Water and Sanitation. Our World Data. 2021 Jul 1 ; Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/clean-water-sanitation . [cited 2022 Feb 14]

Sustainable Development Goals | United Nations Development Programme. Available from: https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals . [cited 2022 Feb 14]

Dkhar NB, Gamma M, Pvt C, Aerosols A. Discussion Paper : Aligning India ’ s Sanitation Policies with the SDGs ALIGNING INDIA ’ S SANITATION POLICIES WITH SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS ( SDGs ) Girija K Bharat , Nathaniel B Dkhar and Mary Abraham. 2020;(May).

Khurana I, Sen R. Drinking water quality in rural India : Issues and approaches. Water aid. 2008;288701:31.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 6) | United Nations Western Europe. Available from: https://unric.org/en/sdg-6/ . [cited 2022 Jan 14]

GoI. SDG India Index & Dashboard 2020–21 report. Partnerships Decad Action. 2021;348. Available from: https://niti.gov.in/writereaddata/files/SDG_3.0_Final_04.03.2021_Web_Spreads.pdf

UN. Sustainable Development Goals Progress Chart 2020 Technical Note. 2020;1–7. Available from: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/Progress_Chart_2020_Technical_note.pdf

NSS report no.584: Drinking Water, Sanitation, Hygiene and Housing condition in India, NSS 76th round (July –December 2018). Available from: https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1593252 . [cited 2022 May 2]

Sample N, Office S, Implementation P. India - Drinking water , sanitation , hygiene and housing condition : NSS 69th Round : July 2012- Dec 2012. 2016;(July 2012).

Chakrapani R, India W, Samithi CPS. Domestic water and sanitation in Kerala: a situation analysis. In Forum for Policy Dialogue on Water Conflicts in India Pune; 2014.

Chaudhuri S, Roy M. Rural-urban spatial inequality in water and sanitation facilities in India: A cross-sectional study from household to national level. Appl Geogr. 2017;85:27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.05.003 .

Article Google Scholar

Saleem M, Burdett T, Heaslip V. Health and social impacts of open defecation on women: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–12.

Roy A, Pramanick K. Analysing progress of sustainable development goal 6 in India: Past, present, and future. J Environ Manage. 2019;232:1049–65.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ghosh N, Bhowmick S, Saha R. Clean Water and Sanitation: India’s Present and Future Prospects. In: Sustainable Development Goals. Springer; 2020. p. 95–105.

Hazra S, Bhukta A. Sustainable Development Goals. Springer International Publishing; 2020.

Coffey D, Spears D, Vyas S. Switching to sanitation: Understanding latrine adoption in a representative panel of rural Indian households. Soc Sci Med. 2017;188:41–50.

Jenkins MW, Curtis V. Achieving the ‘good life’: Why some people want latrines in rural Benin. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(11):2446–59.

Jenkins MW, Scott B. Behavioral indicators of household decision-making and demand for sanitation and potential gains from social marketing in Ghana. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(12):2427–42.

Dreibelbis R, Jenkins M, Chase RP, Torondel B, Routray P, Boisson S, et al. Development of a multidimensional scale to assess attitudinal determinants of sanitation uptake and use. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49(22):13613–21.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to NSS and NARSS for making the data available for this study.

We did not receive any grants from any funding agency in public, commercial, or non-profit sectors for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Population & Development, International Institute for Population Sciences, Govandi Station Road, Opposite Sanjona Chamber, Deonar, Mumbai, Maharashtra, 400088, India

Sourav Biswas

Department of Geography, Ravenshaw University, College Road, Cuttack, Odisha, 753003, India

Biswajit Dandapat

Department of Geography, Serampore Girls’ College, University of Calcutta, Serampore, 712201, India

Asraful Alam

Professor of Geography & Director, UGC-HRDC, University of Calcutta, Kolkata, 700019, India

Lakshminarayan Satpati

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SB- Background, Methodology, Result & Discussion, Tables and Figures, Conclusion, Final editing and Submit the Manuscript. BD-Background, Methodology, Result & Discussion, Table, Conclusion. AA- Editing the total manuscript and adding some literature. LNS- Overall guidance for making this research and editing some portion of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sourav Biswas .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Since it is secondary data and it is available in the Public domain for free in NSS website. There is no need for ethical clearance.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

We declare that We have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Biswas, S., Dandapat, B., Alam, A. et al. India's achievement towards sustainable Development Goal 6 (Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all) in the 2030 Agenda. BMC Public Health 22 , 2142 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14316-0

Download citation

Received : 25 May 2022

Accepted : 06 October 2022

Published : 21 November 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14316-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Sustainable Development

- Public Health

- Clean Water and Sanitation

- Universal coverage of latrine and sanitation

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

NITI Aayog Releases SDG India Index and Dashboard 2020–21

The third edition of the SDG India Index and Dashboard 2020–21 was released by NITI Aayog today. Since its inaugural launch in 2018, the indexhas been comprehensively documenting and rankingthe progress made by States and Union Territories towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Now in its third year, the index has become the primary tool for monitoring progress on the SDGs in the country and has simultaneously fostered competition among the States and Union Territories.

NITI Aayog ViceChairperson Dr Rajiv Kumar launched the report titled, SDG India Index and Dashboard 2020–21: Partnerships in the Decade of Action , in the presence of Dr Vinod Paul, Member (Health), NITI Aayog, Shri Amitabh Kant, CEO, NITI Aayog, and Ms.Sanyukta Samaddar,Adviser (SDGs), NITI Aayog. Designed and developed by NITI Aayog, the preparation of the index followed extensive consultations with the primary stakeholders—the States and Union Territories; the UN agencies led by United Nations in India;Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI), and the key Union Ministries.

“Our effort of monitoring SDGs through the SDG India Index & Dashboard continues to be widely noticed and applauded around the world. It remains a rare data-driven initiative to rank our States and Union Territories by computing a composite index on the SDGs. We are confident that it will remain a matter of aspiration and emulation and help propel monitoring efforts at the international level,”Dr. Rajiv Kumar, Vice Chairman, NITI Aayog said during the launch.

With one-third of the journey towards achieving the 2030 Agenda behind us, this edition of the index report focuses on the significance of partnerships as its theme. Shri Amitabh Kant, CEO, NITI Aayog said, “The report reflects on the partnerships we have built and strengthened during our SDG efforts. The narrative throws light on how collaborative initiatives can result in better outcomes and greater impacts.”

On thetheme of partnerships which is central to Goal 17, Dr. Vinod Paul, Member (Health), NITI Aayog, said,“It is clear that by working togetherwe can build a more resilient and sustainable future, where no one is left behind.”

“From covering 13 Goals with 62 indicators in its first edition in 2018, the third edition covers 16 Goals on 115 quantitative indicators, with a qualitative assessment on Goal 17, thereby reflecting our continuous efforts towards refining this important tool,” said Ms. Sanyukta Samaddar, Adviser (SDGs), NITI Aayog.

NITI Aayog has the twin mandate to oversee the adoption and monitoring of the SDGs in the country, and also promote competitive and cooperative federalism among States and UTs. The index represents the articulation of the comprehensive nature of the Global Goals under the 2030 Agenda while being attuned to the national priorities. The modular nature of the index has become a policy tool and a ready reckoner for gauging progress of States and UTs on the expansive nature of the Goals, including health, education, gender, economic growth, institutions, climate change and environment.

From right to left: Dr Vinod Paul, Member (Health);Dr Rajiv Kumar,Vice Chairperson; Shri Amitabh Kant, CEO; and Ms. Sanyukta Samaddar, Adviser (SDGs), NITI Aayog

SDG India Index andDashboard 2020–21: An Introduction to the Third Edition

The SDG India Index 2020–21, developed in collaboration with the United Nations in India, tracks progress of all States and UTs on 115 indicators that are aligned to MoSPI’s National Indicator Framework (NIF). The initiative to refine and improve this important tool with each edition has been steered by the need to continuously benchmark performance and measure progress, and to account for the availability of latest SDG-related data on States and UTs. The process of selecting these 115 indicators included multipleconsultations with Union Ministries. Feedback was sought from all States and UTs and as the essential stakeholder and audience of this localisation tool, they played a crucial role in shaping the index by enriching the feedback process with localised insights and experience from the ground.

The SDG India Index 2020–21 is more robust than the previous editions on account of wider coverage of targets and indicators with greater alignment with the NIF.The 115 indicators incorporate16 out of 17 SDGs, with a qualitative assessment on Goal 17,andcover 70 SDG targets. This is an improvement over the 2018–19 and 2019–20 editions of the index, which had utilised 62 indicators across 39 targets and 13 Goals, and 100 indicators across 54 targets and 16 Goals, respectively.

The SDG India Index computes goal-wise scores onthe 16 SDGs for each State and Union Territory. Overall State and UT scores are generated from goal-wise scores to measure aggregate performance of the sub-national unit based on its performance across the 16 SDGs. These scores range between 0–100, and if a State/UT achieves a score of 100, it signifies it has achieved the 2030 targets. The higher the score of a State/UT, the greater the distance to target achieved.

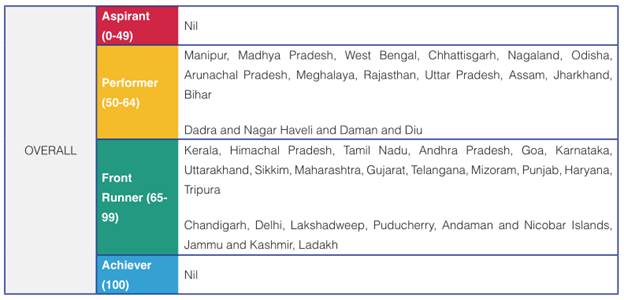

States and Union Territories are classified as below based on their SDG India Index score:

- Aspirant: 0–49

- Performer: 50–64

- Front-Runner: 65–99

- Achiever: 100

Overall Results and Findings

The country’s overall SDG score improved by 6 points—from 60 in 2019 to 66 in 2020–21. This positive stride towards achieving the targets is largely driven by exemplary country-wide performance in Goal 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and Goal 7(Affordable and Clean Energy), where the composite Goal scoresare 83 and 92, respectively.

Goal-wise India results, 2019–20 and 2020–21:

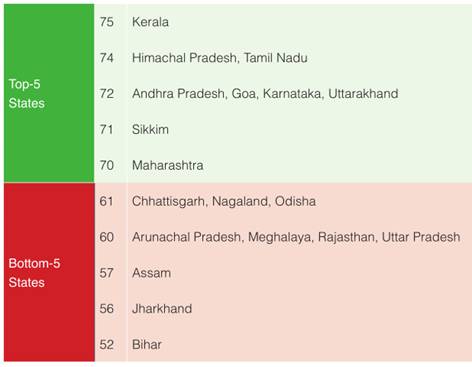

The top-fiveand bottom-fiveStates in SDG India Index 2020–21:

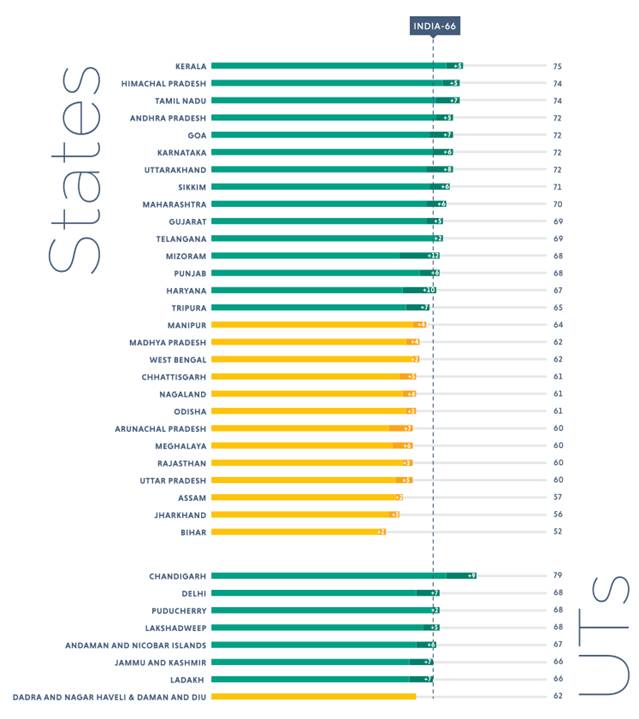

Performance and Ranking of States and UTs on SDGs 2020–21, including change in score from last year:

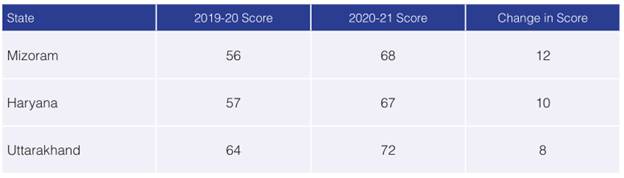

Mizoram, Haryana, and Uttarakhand are the top gainers in 2020–21in terms of improvement in score from 2019, with an increase of 12, 10 and 8 points, respectively.

Top Fast-Moving States (Score-Wise):

While in 2019, ten States/UTs belonged to the category of Front-Runners (score in the range 65–99, including both) twelve more States/UTs find themselves in this category in 2020–21. Uttarakhand, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Mizoram, Punjab, Haryana, Tripura, Delhi, Lakshadweep, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh graduated to the category of Front-Runners (scores between 65 and 99, including both).

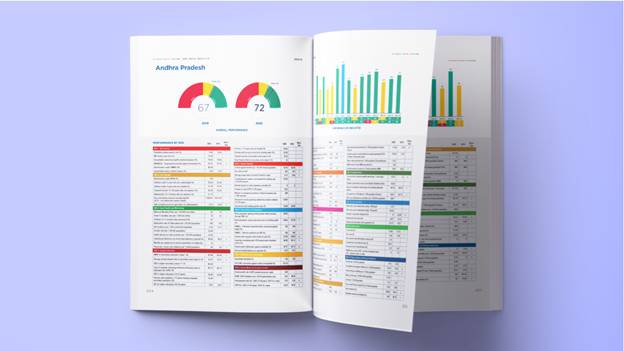

Asection of the SDG India Index report is dedicated to all the 36 Statesand UTs of the country. These State and UT profiles will be very useful for policymakers, scholars and the general public, to analyse the performance on the 115 indicators across all Goals.

Sample of a State/UT profile from the report:

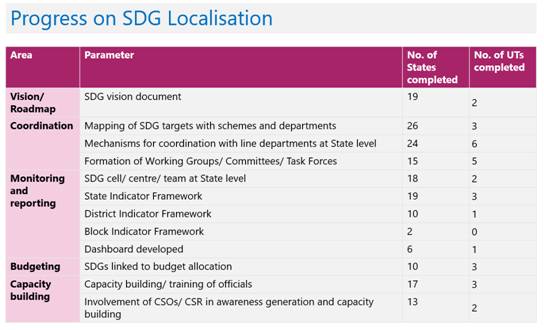

It is followed by a unique section on the progress on SDG localisation in States and Union Territories. It provides an update on the institutional structures, SDG vision documents, State and District Indicator Frameworks and other initiatives taken by the State and UT governments.

The SDG India Index2020–21 is also live on an online dashboard, which has cross-sectoral relevance across policy, civil society, business, and academia. The index is designed to function as a tool for focused policy dialogue, formulation and implementation through development actions,which are pegged to the globally recognisable metric of the SDG framework.The index and dashboardwill also facilitate in identifying crucial gaps related to tracking the SDGs and the need for India to develop its statistical systems at the State/UT levels.As another milestone in the SDG localisation journey of the country, the Index is presently being adapted and developed by NITI Aayogatthe granular level of districts for the upcoming North Eastern Region District SDG Index.

A snapshot of the SDG India Index 2020–21 dashboard:

NITI Aayog has the mandate for coordinating the adoption and monitoring of SDGs at the national and sub-national levels. The SDG India Index and Dashboard represents NITI Aayog’s efforts inencouraging evidence-based policymaking by supporting States and UTs to benchmark their progress, identify the priority areas and share good practices.

The full SDG India Index report can be accessed here: https://wgz.short.gy/SDGIndiaIndex

The interactive dashboard can be accessed here: http://sdgindiaindex.niti.gov.in /

Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals lay out a uniquely ambitious and comprehensive agenda for global development by 2030. NITI Aayog is the nodal institution for achieving SDGs in the country, leading the 2030 Agenda with the spirit of cooperative and competitive federalism.

It monitors the national and sub-national levels progress through various mechanisms like the SDG India Index and Dashboard, Multidimensional Poverty Index: Progress review 2023, North Eastern Region Index and Dashboard and the likes. Localization of the SDGs is the key to reach furthest behind first, and therefore a crucial mandate of the vertical. These efforts have strengthened the statistical systems and developed a monitoring framework covering all the 17 Goals and more than 100 indicators across the country. With this refined and comprehensive edition, we aim to cement India’s place as a trailblazer in SDG achievement.

Call us @ 08069405205

Search Here

- An Introduction to the CSE Exam

- Personality Test

- Annual Calendar by UPSC-2024

- Common Myths about the Exam

- About Insights IAS

- Our Mission, Vision & Values

- Director's Desk

- Meet Our Team

- Our Branches

- Careers at Insights IAS

- Daily Current Affairs+PIB Summary

- Insights into Editorials

- Insta Revision Modules for Prelims

- Current Affairs Quiz

- Static Quiz

- Current Affairs RTM

- Insta-DART(CSAT)

- Insta 75 Days Revision Tests for Prelims 2024

- Secure (Mains Answer writing)

- Secure Synopsis

- Ethics Case Studies

- Insta Ethics

- Weekly Essay Challenge

- Insta Revision Modules-Mains

- Insta 75 Days Revision Tests for Mains

- Secure (Archive)

- Anthropology

- Law Optional

- Kannada Literature

- Public Administration

- English Literature

- Medical Science

- Mathematics

- Commerce & Accountancy

- Monthly Magazine: CURRENT AFFAIRS 30

- Content for Mains Enrichment (CME)

- InstaMaps: Important Places in News

- Weekly CA Magazine

- The PRIME Magazine

- Insta Revision Modules-Prelims

- Insta-DART(CSAT) Quiz

- Insta 75 days Revision Tests for Prelims 2022

- Insights SECURE(Mains Answer Writing)

- Interview Transcripts

- Previous Years' Question Papers-Prelims

- Answer Keys for Prelims PYQs

- Solve Prelims PYQs

- Previous Years' Question Papers-Mains

- UPSC CSE Syllabus

- Toppers from Insights IAS

- Testimonials

- Felicitation

- UPSC Results

- Indian Heritage & Culture

- Ancient Indian History

- Medieval Indian History

- Modern Indian History

- World History

- World Geography

- Indian Geography

- Indian Society

- Social Justice

- International Relations

- Agriculture

- Environment & Ecology

- Disaster Management

- Science & Technology

- Security Issues

- Ethics, Integrity and Aptitude

- Indian Heritage & Culture

- Enivornment & Ecology

EDITORIAL ANALYSIS : India, its SDG pledge goal, and the strategy to apply

Source: The Hindu

- Prelims: Current events of international importance, SDG, covid-19, G20, G7, etc.

- Mains GS Paper II: Bilateral, regional and global grouping and agreements involving India or affecting India’s interests, Significance of G20 countries etc

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS