An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Med Educ

A systematic scoping review of reflective writing in medical education

Jia yin lim.

1 Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, NUHS Tower Block, 1E Kent Ridge Road, Level 11, Singapore, 119228 Singapore

2 Division of Supportive and Palliative Care, National Cancer Centre Singapore, 11 Hospital Crescent, Singapore, 169610 Singapore

Simon Yew Kuang Ong

3 Division of Medical Oncology, National Cancer Centre Singapore, 11 Hospital Crescent, Singapore, 169610 Singapore

4 Division of Cancer Education, National Cancer Centre Singapore, 11 Hospital Crescent, Singapore, 169610 Singapore

5 Duke-NUS Medical School, National University of Singapore, 8 College Rd, Singapore, 169857 Singapore

Chester Yan Hao Ng

Karis li en chan, song yi elizabeth anne wu, wei zheng so, glenn jin chong tey, yun xiu lam, nicholas lu xin gao, yun xue lim, ryan yong kiat tay, ian tze yong leong, nur diana abdul rahman, crystal lim.

6 Medical Social Services, Singapore General Hospital, Outram Rd, Singapore, 169608 Singapore

Gillian Li Gek Phua

7 Lien Centre for Palliative Care, Duke-NUS Medical School, National University of Singapore, 8 College Rd, Singapore, 169857 Singapore

Vengadasalam Murugam

Eng koon ong.

8 Assisi Hospice, 832 Thomson Rd, Singapore, 574627 Singapore

Lalit Kumar Radha Krishna

9 Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, Academic Palliative & End of Life Care Centre, Cancer Research Centre, University of Liverpool, 200 London Road, Liverpool, L3 9TA UK

10 PalC, The Palliative Care Centre for Excellence in Research and Education, PalC c/o Dover Park Hospice, 10 Jalan Tan Tock Seng, Singapore, 308436 Singapore

Associated Data

All data generated or analysed during this review are included in this published article and its supplementary files.

Reflective writing (RW) allows physicians to step back, review their thoughts, goals and actions and recognise how their perspectives, motives and emotions impact their conduct. RW also helps physicians consolidate their learning and boosts their professional and personal development. In the absence of a consistent approach and amidst growing threats to RW’s place in medical training, a review of theories of RW in medical education and a review to map regnant practices, programs and assessment methods are proposed.

A Systematic Evidence-Based Approach guided Systematic Scoping Review (SSR in SEBA) was adopted to guide and structure the two concurrent reviews. Independent searches were carried out on publications featured between 1st January 2000 and 30th June 2022 in PubMed, Embase, PsychINFO, CINAHL, ERIC, ASSIA, Scopus, Google Scholar, OpenGrey, GreyLit and ProQuest. The Split Approach saw the included articles analysed separately using thematic and content analysis. Like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, the Jigsaw Perspective combined the themes and categories identified from both reviews. The Funnelling Process saw the themes/categories created compared with the tabulated summaries. The final domains which emerged structured the discussion that followed.

A total of 33,076 abstracts were reviewed, 1826 full-text articles were appraised and 199 articles were included and analysed. The domains identified were theories and models, current methods, benefits and shortcomings, and recommendations.

Conclusions

This SSR in SEBA suggests that a structured approach to RW shapes the physician’s belief system, guides their practice and nurtures their professional identity formation. In advancing a theoretical concept of RW, this SSR in SEBA proffers new insight into the process of RW, and the need for longitudinal, personalised feedback and support.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-022-03924-4.

Introduction

Reflective practice in medicine allows physicians to step back, review their actions and recognise how their thoughts, feelings and emotions affect their decision-making, clinical reasoning and professionalism [ 1 ]. This approach builds on Dewey [ 2 ], Schon [ 3 , 4 ], Kolb [ 5 ], Boud et al. [ 6 ] and Mezirow [ 7 ]’s concepts of critical self-examination. It sees new insights drawn from the physician’s experiences and considers how assumptions may integrate into their current values, beliefs and principles (henceforth belief system) [ 8 , 9 ].

Teo et al. [ 10 ] build on this concept of reflective practice. The authors suggest that the physician’s belief system informs and is informed by their self-concepts of identity which are in turn rooted in their self-concepts of personhood - how they conceive what makes them who they are [ 11 ]. This posit not only ties reflective practice to the shaping of the physician’s moral and ethical compass but also offers evidence of it's role in their professional identity formation (PIF) [ 8 , 12 – 23 ]. With PIF [ 8 , 24 ] occupying a central role in medical education, these ties underscore the critical importance placed on integrating reflective practice in medical training.

Perhaps the most common form of reflective practice in medical education is reflective writing (RW) [ 25 ]. Identified as one of the distinct approaches used to achieve integrated learning, education, curriculum and teaching [ 26 ], RW already occupies a central role in guiding and supporting longitudinal professional development [ 27 – 29 ]. Its ability to enhance self-monitoring and self-regulation of decisional paradigms and conduct has earned RW a key role in competency-based medical practice and continuing professional development [ 30 – 36 ].

However, the absence of consistent guiding principles, dissonant practices, variable structuring and inadequate assessments have raised concerns as to RW’s efficacy and place in medical training [ 25 , 37 – 39 ]. A Systematic Scoping Review is proposed to map current understanding of RW programs. It is hoped that this SSR will also identify gaps in knowledge and regnant practices, programs and assessment methods to guide the design of RW programs.

Methodology

A Systematic Scoping Review (SSR) is employed to map the employ, structuring and assessment of RW in medical education. An SSR-based review is especially useful in attending to qualitative data that does not lend itself to statistical pooling [ 40 – 42 ] whilst its broad flexible approach allows the identification of patterns, relationships and disagreements [ 43 ] across a wide range of study formats and settings [ 44 , 45 ].

To synthesise a coherent narrative from the multiple accounts of reflective writing, we adopt Krishna’s Systematic Evidence-Based Approach (SEBA) [ 10 , 15 , 21 , 46 – 53 ]. A SEBA-guided Systematic Scoping Review (SSR in SEBA) [ 13 – 24 , 50 , 53 – 55 ] facilitates reproducible, accountable and transparent analysis of patterns, relationships and disagreements from multiple angles [ 56 ].

The SEBA process (Fig. 1 ) comprises the following elements: 1) Systematic Approach, 2) Split Approach, 3) Jigsaw Perspective, 4) Funnelling Process, 5) Analysis of data and non-data driven literature, and 6) Synthesis of SSR in SEBA [ 10 , 15 , 21 , 46 – 53 , 57 – 60 ] . Every stage was overseen by a team of experts that included medical librarians from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSoM) at the National University of Singapore, and local educational experts and clinicians at YLLSoM, Duke-NUS Medical School, Assisi Hospice, Singapore General Hospital, National Cancer Centre Singapore and Palliative Care Institute Liverpool.

The SEBA Process

STAGE 1 of SEBA: Systematic Approach

Determining the title and background of the review.

Ensuring a systematic approach, the expert team and the research team agreed upon the overall goals of the review. Two separate searches were performed, one to look at the theories of reflection in medical education, and another to review regnant practices, programs, and assessment methods used in reflective writing in medical education. The PICOs is featured in Table 1 .

PICOs inclusion and exclusion criteria

Identifying the research question

Guided by the Population Concept, Context (PCC) elements of the inclusion criteria and through discussions with the expert team, the research question was determined to be: “ How is reflective writing structured, assessed and supported in medical education? ” The secondary research question was “ How might a reflective writing program in medical education be structured? ”

Inclusion criteria

All study designs including grey literature published between 1st January 2000 to 30th June 2022 were included [ 61 , 62 ]. We also consider data on medical students and physicians from all levels of training (henceforth broadly termed as physicians).

Ten members of the research team carried out independent searches using seven bibliographic databases (PubMed, Embase, PsychINFO, CINAHL, ERIC, ASSIA, Scopus) and four grey literature databases (Google Scholar, OpenGrey, GreyLit, ProQuest). Variations of the terms “reflective writing”, “physicians and medical students”, and “medical education” were applied.

Extracting and charting

Titles and abstracts were independently reviewed by the research team to identify relevant articles that met the inclusion criteria set out in Table Table1. 1 . Full-text articles were then filtered and proposed. These lists were discussed at online reviewer meetings and Sandelowski and Barroso [ 63 ]’s approach to ‘negotiated consensual validation’ was used to achieve consensus on the final list of articles to be included.

Stage 2 of SEBA: Split Approach

The Split Approach was employed to enhance the trustworthiness of the SSR in SEBA [ 64 , 65 ]. Data from both searches were analysed by three independent groups of study team members.

The first group used Braun and Clarke [ 66 ]’s approach to thematic analysis. Phase 1 consisted of ‘actively’ reading the included articles to find meaning and patterns in the data. The analysis then moved to Phase 2 where codes were constructed. These codes were collated into a codebook and analysed using an iterative step-by-step process. As new codes emerge, previous codes and concepts were incorporated. In Phase 3, codes and subthemes were organised into themes that best represented the dataset. An inductive approach allowed themes to be “defined from the raw data without any predetermined classification” [ 67 ]. In Phase 4, these themes were then further refined to best depict the whole dataset. In Phase 5, the research team discussed the results and consensus was reached, giving rise to the final themes.

The second group employed Hsieh and Shannon [ 68 ]’s approach to directed content analysis. Categories were drawn from Mann et al. [ 9 ]’s article, “Reflection and Reflective Practice in Health Professions Education: A Systematic Review” and Wald and Reis [ 69 ]’s article “Beyond the Margins: Reflective Writing and Development of Reflective Capacity in Medical Education”.

The third group created tabulated summaries in keeping with recommendations drawn from Wong et al. [ 56 ]’s "RAMESES Publication Standards: Meta-narrative Reviews" and Popay et al. [ 70 ]’s “Guidance on the C onduct of N arrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews”. The tabulated summaries served to ensure that key aspects of included articles were not lost.

Stage 3 of SEBA: Jigsaw Perspective

The Jigsaw Perspective [ 71 , 72 ] saw the findings of both searches combined. Here, overlaps and similarities between the themes and categories from the two searches were combined to create themes/categories. The themes and subthemes were compared with the categories and subcategories identified, and similarities were verified by comparing the codes contained within them. Individual subthemes and subcategories were combined if they were complementary in nature.

Stage 4 of SEBA: Funnelling Process

The Funnelling Process saw the themes/categories compared with the tabulated summaries to determine the consistency of the domains created, forming the basis of the discussion.

Stage 5: Analysis of data and non-data driven literature

Amidst concerns that data from grey literature which were neither peer-reviewed nor necessarily evidence-based may bias the synthesis of the discussion, the research team separately thematically analysed the included grey literature. These themes were compared with themes from data-driven or research-based peer-reviewed data and were found to be the same and thus unlikely to have influenced the analysis.

Stage 6: Synthesis of SSR in SEBA

The Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) Collaboration Guide and the Structured approach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis (STORIES) were used to guide the discussion.

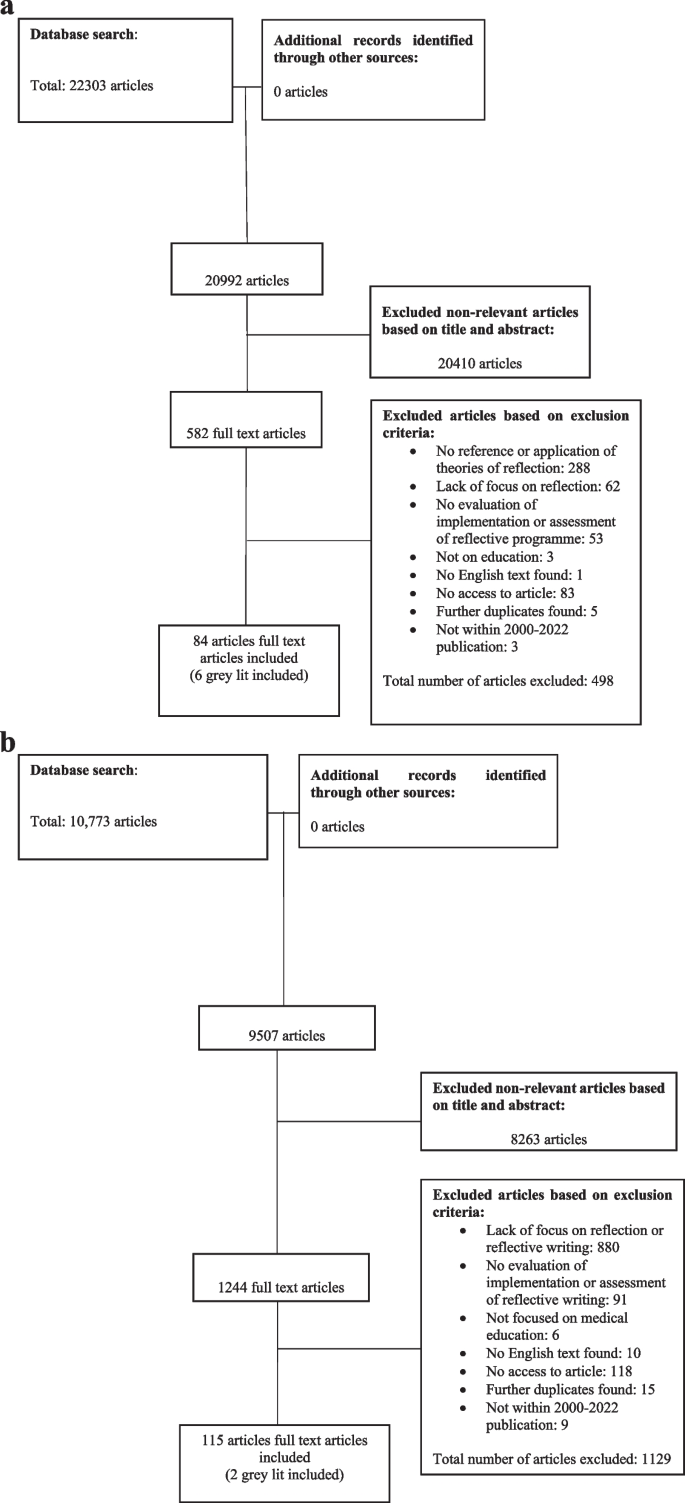

A total of 33,076 abstracts were reviewed from the two separate searches on theories of reflection in medical education, and on regnant practices, programs and assessments of RW programs in medical education. A total of 1826 full-text articles were appraised from the separate searches, and 199 articles were included and analysed. The PRISMA Flow Chart may be found in Fig. 2 a and b. The domains identified when combining the findings of the two separate searches were 1) Theories and Models, 2) Current Methods, 3) Benefits and Shortcomings and 4) Recommendations.

a PRISMA Flow Chart (Search Strat #1: Theories of Reflection in Medical Education). b PRISMA Flow Chart (Search Strat #2: Reflective Writing in Medical Education)

Domain 1: Theories and Models

Many current theories and models surrounding RW in medical education are inspired by Kolb’s Learning Cycle [ 5 ] (Table 2 ). These theories focus on descriptions of areas of reflection; evaluations of experiences and emotions; how events may be related to previous experiences; knowledge critiques of their impact on thinking and practice; integration of learning points; and the physician’s willingness to apply lessons learnt [ 6 , 73 – 75 ]. In addition, some of these theories also consider the physician’s self-awareness, ability and willingness to reflect [ 76 ], contextual factors related to the area of reflection [ 4 , 77 ] and the opportunity to reflect effectively within a supportive environment [ 78 , 79 ]. Ash and Clayton's DEAL Model recommends inclusion of information from all five senses [ 80 – 83 ]. Johns's Model of Structured Reflection [ 84 ] advocates giving due consideration to internal and external influences upon the event being evaluated. Rodgers [ 39 ] underlines the need for appraisal of the suppositions and assumptions that precipitate and accompany the effects and responses that may have followed the studied event. Griffiths and Tann [ 75 ], Mezirow [ 77 ], Kim [ 85 ], Roskos et al. [ 86 ], Burnham et al. [ 87 ], Korthagen and Vasalos [ 78 ] and Koole et al. [ 74 ] build on Dewey [ 2 ] and Kolb [ 5 ]’s notion of creating and experimenting with a ‘working hypothesis’. These models also propose that the lessons learnt from experimentations should be critiqued as part of a reiterative process within the reflective cycle. Underlining the notion of the reflective cycle and the long-term effects of RW, Pearson and Smith [ 88 ] suggest that reflections should be carried out regularly to encourage longitudinal and holistic reflections on all aspects of the physician’s personal and professional life.

Theories and models referred for implementation - iterative stages of reflection

Regnant theories shape assessments of RW (Table 3 ). This extends beyond Thorpe [ 96 ]’s study which categorises reflective efforts into ‘non-reflectors’, ‘reflectors’, ‘critical reflectors’, and focuses on their process, structure, depth and content. van Manen [ 97 ], Plack et al. [ 98 ], Rogers et al. [ 99 ] and Makarem et al. [ 100 ] begin with evaluating the details of the events. Kim’s Critical Reflective Inquiry Model [ 85 ] and Bain’s 5Rs Reflective Framework [ 101 ] also consider characterisations of emotions involved. Other models appraise the intentions behind actions and thoughts [ 85 ], the factors precipitating the event [ 101 ] and meaning-making [ 85 ]. Other theories consider links with previous experiences [ 100 ], the integration of thoughts, justifications and perspectives [ 99 ], and the hypothesising of future strategies [ 98 ].

Theories and models referred for assessment - vertical levels of reflection

Domain 2: Current methods of structuring RW programs

Current programs focus on supporting the physician throughout the reflective process. Whilst due consideration is given to the physician’s motivations, insight, experiences, capacity and capabilities [ 25 , 96 , 112 – 116 ], programs also endeavour to ensure appropriate selection and training of physicians intending to participate in RW. Efforts are also made to align expectations, and guide and structure the RW process [ 37 , 116 – 122 ]. Physicians are provided with frameworks [ 76 , 79 , 105 , 123 , 124 ], rubrics [ 99 , 123 , 125 , 126 ], examples of the expected quality and form of reflection [ 96 , 115 , 116 ], and how to include emotional and contextual information in their responses [ 121 , 127 – 129 ].

Other considerations are enclosed in Table 4 including frequency, modality and the manner in which RW is assessed.

Current methods of structuring RW programs

Domain 3: Benefits and Shortcomings

The benefits of RW are rarely described in detail and may be divided into personal and professional benefits as summarised in Table 5 for ease of review. From a professional perspective, RW improves learning [ 96 , 112 , 119 , 147 , 157 , 170 , 179 , 185 – 192 ], facilitates continuing medical education [ 119 , 128 , 173 , 174 , 193 – 195 ], inculcates moral, ethical, professional and social standards and expectations [ 118 , 156 , 160 ], improves patient care [ 29 , 120 , 129 , 131 , 135 , 142 , 194 , 196 – 199 ] and nurtures PIF [ 150 , 157 , 172 , 191 , 200 ].

Benefits of RW programs

From a personal perspective, RW increases self-awareness [ 114 , 127 , 137 , 161 , 166 , 179 , 185 , 202 , 216 ], self-advancement [ 9 , 131 , 134 , 150 , 168 , 174 , 195 , 205 , 217 , 229 ], facilitates understanding of individual strengths, weaknesses and learning needs [ 112 , 119 , 150 , 152 , 170 , 218 , 219 ], promotes a culture of self-monitoring, self-improvement [ 130 , 172 , 173 , 185 , 193 , 198 , 201 , 210 , 211 ], developing critical perspectives of self [ 193 , 223 ] and nurtures resilience and better coping [ 154 , 160 , 206 ]. RW also guides shifts in thinking and perspectives [ 148 , 149 , 156 , 203 , 207 , 208 ] and focuses on a more holistic appreciation of decision-making [ 37 , 118 , 126 , 174 , 177 , 194 , 196 , 199 , 200 , 224 – 226 ] and their ramifications [ 37 , 112 , 116 , 130 , 131 , 141 , 154 , 179 , 193 , 194 , 196 , 204 , 207 , 218 , 230 ].

Table 6 combines current lists of the shortcomings of RW. These limitations may be characterised by individual, structural and assessment styles.

Shortcomings of RW programs

It is suggested that RW does not cater to the different learning styles [ 220 , 232 ], cultures [ 190 ], roles, values, processes and expectations of RW [ 114 , 129 , 135 , 138 , 142 , 209 , 227 , 234 ], and physicians' differing levels of self-awareness [ 29 , 79 , 119 , 176 , 188 , 226 , 231 , 236 ], motivations [ 29 , 119 , 136 , 138 , 157 , 161 , 167 – 169 , 176 , 181 , 193 , 196 , 226 , 232 , 233 ] and willingness to engage in RW [ 37 , 114 , 136 , 149 , 160 , 183 ]. RW is also limited by poorly prepared physicians and misaligned expectations whilst a lack of privacy and a safe setting may precipitate physician anxiety at having their private thoughts shared [ 129 , 149 , 209 , 231 ]. RW is also compromised by a lack of faculty training [ 143 , 145 , 239 ], mentoring support [ 37 , 50 , 119 , 133 , 196 ] and personalised feedback [ 50 , 114 , 136 , 167 , 229 ] which may lead to self-censorship [ 37 , 114 , 136 , 149 , 160 , 183 ] and an unwillingness to address negative emotions arising from reflecting on difficult events [ 114 , 168 , 176 , 193 , 230 ], circumventing the reflective process [ 118 , 142 , 165 , 196 ] .

Variations in assessment styles [ 9 , 115 , 157 , 161 , 166 , 193 , 209 ], depth [ 29 , 105 , 118 , 126 , 177 , 207 ] and content [ 37 , 114 , 136 , 149 , 169 , 183 , 196 ], and pressures to comply with graded assessments [ 114 , 115 , 118 , 129 , 138 , 143 , 149 , 155 , 157 , 209 , 232 , 237 , 238 ] also undermine efforts of RW.

Domain 4. Recommendations

In the face of practice variations and challenges, there have been several recommendations on improving practice.

Boosting awareness of RW

Acknowledging the importance of a physician’s motivations, willingness and judgement [ 37 ], an RW program must acquaint physicians with information on RW’s role [ 128 ], program expectations, the form, frequency and assessments of RW and the support available to them [ 130 , 132 , 150 , 154 , 242 ] and its benefits to their professional and personal development [ 96 , 227 ] early in their training programs [ 115 , 220 , 242 , 243 ]. Physicians should also be trained on the knowledge and skills required to meet these expectations [ 1 , 37 , 135 , 151 , 160 , 215 , 244 , 245 ].

A structured program and environment

Recognising that effective RW requires a structured program. Recommendations focus on three aspects of the program design [ 132 ]. One is the need for trained faculty [ 9 , 115 , 219 , 220 , 230 , 233 , 242 , 246 ], accessible communications, protected time for RW and debriefs [ 125 ], consistent mentoring support [ 190 ] and assessment processes [ 247 ]. This will facilitate trusting relationships between physicians and faculty [ 30 , 114 , 168 , 196 , 231 , 233 ]. Two, the need to nurture an open and trusting environment where physicians will be comfortable with sharing their reflections [ 96 , 128 ], discussing their emotions, plans [ 127 , 248 ] and receiving feedback [ 9 , 37 , 79 , 114 , 119 , 128 , 135 , 173 , 176 , 179 , 190 , 237 ]. This may be possible in a decentralised classroom setting [ 163 , 190 ]. Three, RW should be part of the formal curriculum and afforded designated time. RW should be initiated early and longitudinally along the training trajectory [ 116 , 122 ].

Adjuncts to RW programs

Several approaches have been suggested to support RW programs. These include collaborative reflection, in-person discussion groups to share written reflections [ 128 , 131 , 138 , 196 , 199 , 231 , 249 ] and reflective dialogue to exchange feedback [ 119 ], use of social media [ 149 , 160 , 169 , 194 , 204 , 230 ], video-recorded observations and interactions for users to review and reflect on later [ 133 ]. Others include autobiographical reflective avenues in addition to practice-oriented reflection [ 137 ], support groups to help meditate stress or emotions triggered by reflections [ 249 ] and mixing of reflective approaches to meet different learning styles [ 169 , 250 ].

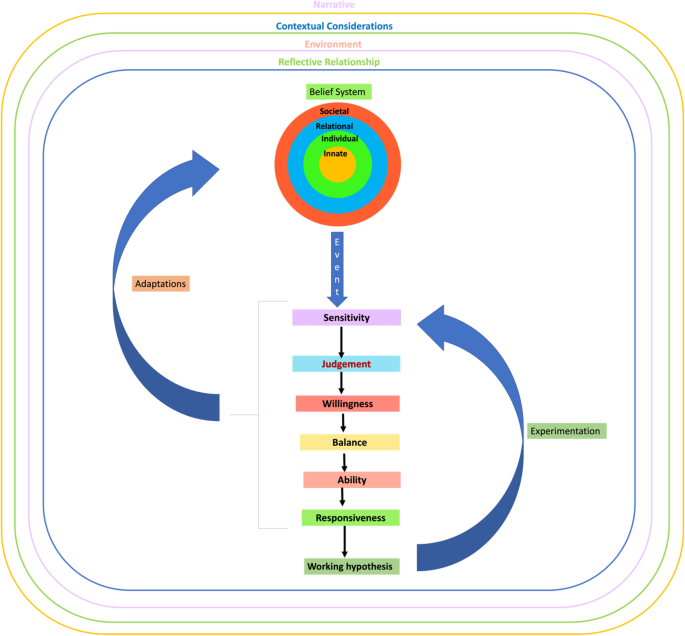

In answering the primary research question, “How is reflective writing structured, assessed and supported in medical education?” , this SSR in SEBA highlights several key insights. To begin, RW involves integrating the insights of an experience or point of reflection (henceforth ‘event’) into the physician’s currently held values, beliefs and principles (henceforth belief system). Recognising that an ‘event’ has occurred and that it needs deeper consideration highlights the physician’s sensitivity . Recognising the presence of an ‘event’ triggers an evaluation as to the urgency in which it needs to be addressed, where it stands amongst other ‘events’ to be addressed and whether the physician has the appropriate skills, support and time to address the ‘event’. This reflects the physician’s judgement . The physician must then determine whether they are willing to proceed and the ramifications involved. These include ethical, medical, clinical, administrative, organisational, sociocultural, legal and professional considerations. This is then followed by contextualising them to their own personal, psychosocial, clinical, professional, research, academic, and situational setting. Weighing these amidst competing ‘events’ underlines the import of the physician’s ability to ‘balance’ considerations. Creating and experimenting on their ‘working hypothesis’ highlights their ‘ability’, whilst how they evaluate the effects of their experimentation and how they adapt their practice underscores their ‘ responsiveness ’ [ 2 , 5 , 74 , 75 , 77 , 78 , 85 – 87 , 90 ].

The concepts of ‘ sensitivity’, ‘judgement’, ‘willingness’, ‘balance’, ‘ability’ and ‘responsiveness’ spotlight environmental and physician-related factors. These include the physician’s motivations, knowledge, skills, attitudes, competencies, working style, needs, availabilities, timelines, and their various medical, clinical, administrative, organisational, sociocultural, legal, professional, personal, psychosocial, clinical, research, academic and situational experiences. It also underlines the role played by the physician’s beliefs, moral values, ethical principles, familial mores, cultural norms, attitudes, thoughts, decisional preferences, roles and responsibilities. The environmental-related factors include the influence of the curriculum, the culture, structure, format, assessment and feedback of the RW process and the program it is situated in. Together, the physician and their environmental factors not only frame RW as a sociocultural construct necessitating holistic review but also underscore the need for longitudinal examination of its effects. This need for holistic and longitudinal appraisal of RW is foregrounded by the experimentations surrounding the ‘working hypothesis’ [ 2 , 5 , 72 , 74 , 77 , 84 – 86 , 90 ]. In turn, experimentations and their effects affirm the notion of regular use of RW and reiterate the need for longitudinal reflective relationships that provide guidance, mentoring and feedback [ 87 , 90 ]. These considerations set the stage for the proffering of a new conceptual model of RW.

To begin, the Krishna Model of Reflective Writing (Fig. 3 ) builds on the Krishna-Pisupati Model [ 10 ] used to describe evaluations of professional identity formation (PIF) [ 8 , 10 , 24 , 251 ]. Evidenced in studies of how physicians cope with death and dying patients, moral distress and dignity-centered care [ 46 , 54 ], the Krishna-Pisupati Model suggests that the physician’s belief system is informed by their self-concepts of personhood and identity. This is effectively characterised by the Ring Theory of Personhood (RToP) [ 11 ].

Krishna Model of Reflective Writing

The Krishna Model of RW posits that the RToP is able to encapsulate various aspects of the physician’s belief system. The Innate Ring which represents the innermost ring of the four concentric rings depicting the RToP is derived from currently held spiritual, religious, theist, moral and ethical values, beliefs and principles [ 13 , 51 , 53 , 252 ]. Encapsulating the Innate Ring is the Individual Ring. The Individual Ring’s belief system is derived from the physician’s thoughts, conduct, biases, narratives, personality, decision-making processes and other facets of conscious function which together inform the physician’s Individual Identity [ 13 , 51 , 53 , 252 ]. The Relational Ring is shaped by the values, beliefs and principles governing the physician’s personal and important relationships [ 13 , 51 , 53 , 252 ]. The Societal Ring, the outermost ring of the RToP is shaped by regnant societal, religious, professional and legal expectations, values, beliefs and principles which inform their interactions with colleagues and acquaintances [ 13 , 51 , 53 , 252 ]. Adoption of the RToP to depict this belief system not only acknowledges the varied aspects and influences that shape the physician’s identity but that the belief system evolves as the physician’s environment, narrative, context and relationships change.

The environmental factors influencing the belief system include the support structures used to facilitate reflections such as appropriate protected time, a consistent format for RW, a structured assessment program, a safe environment, longitudinal support, timely feedback and trained faculty. The Krishna Model of RW also recognises the importance of the relationships which advocate for the physician and proffer the physician with coaching, role modelling, supervision, networking opportunities, teaching, tutoring, career advice, sponsorship and feedback upon the RW process. Of particular importance is the relationship between physician and faculty (henceforth reflective relationship). The reflective relationship facilitates the provision of personalised, appropriate, holistic, and frank communications and support. This allows the reflective relationship to support the physician as they deploy and experiment with their ‘working hypothesis’. As a result, the Krishna Model of RW focuses on the dyadic reflective relationship and acknowledges that there are wider influences beyond this dyad that shape the RW process. This includes the wider curriculum, clinical, organisational, social, professional and legal considerations within specific practice settings and other faculty and program-related factors. Important to note, is that when an ‘event’ triggers ‘ sensitivity’, ‘judgement’, ‘willingness’, ‘balance’, ‘ability’ and ‘responsiveness’, the process of creating and experimenting with a ‘working hypothesis' and adapting one's belief system is also shaped by the physician’s narratives, context, environment and relationships.

In answering its secondary question, “ How might a reflective writing program in medical education be structured? ”, the data suggests that an RW program ought to be designed with due focus on the various factors influencing the physician's belief system, their ‘sensitivity’, ‘judgement’, ‘willingness’, ‘balance’, ‘ability’ and ‘responsiveness’, and their creation and experimentation with their ‘working hypothesis’. These will be termed the ‘physician's reactions’ . The design of the RW program ought to consider the following factors:

- Recognising that the physician’s notion of ‘ sensitivity’, ‘judgement’, ‘willingness’, ‘balance’, ‘ability’ and ‘responsiveness’ is influenced by their experience, skills, knowledge, attitude and motivations, physicians recruited to the RW program should be carefully evaluated

- To align expectations, the physician should be introduced to the benefits and role of RW in their personal and professional development

- The ethos, frequency, goals and format of the reflection and assessment methods should be clearly articulated to the physician [ 253 ]

- The physician should be provided with the knowledge, skills and mentoring support necessary to meet expectations [ 76 , 79 , 105 , 123 , 124 , 254 , 255 ]

- Training and support must also be personalised

- Recognising that the physician’s academic, personal, research, administrative, clinical, professional, sociocultural and practice context will change, the structure, approach, assessment and support provided must be flexible and responsive

- The communications platform should be easily accessible and robust to attend to the individual needs of the physician in a timely and appropriate manner

- The program must support diversity [ 207 ]

- The reflective relationship is shaped by the culture and structure of the environment in which the program is hosted in

- The RW programs must be hosted within a formal structured curriculum, supported and overseen by a host organisation which is able to integrate the program into regnant educational and assessment processes [ 9 , 115 , 219 , 220 , 230 , 233 , 242 , 246 ]

- The faculty must be trained and provided access to counselling, mindfulness meditation and stress management programs [ 249 ]

- The faculty must support the development of the physician’s metacognitive skills [ 256 – 259 ], and should create a platform that facilitates community-centered learning [ 173 , 176 ], structured, timely, personalised open feedback [ 119 , 135 , 179 , 237 ] and support [ 128 , 131 , 138 , 196 , 199 , 231 , 249 ]

- The faculty must be responsive to changes and provide appropriate personal, educational and professional support and adaptations to the assessment process when required [ 207 ]

- To facilitate the development of effective reflective relationships, a consistent faculty member should work with the physician and build a longitudinal trusting, open and supportive reflective relationship

- The evolving nature of the various structures and influences upon the RW process underscores the need for longitudinal assessment and support

- The physician must be provided with timely, appropriate and personalised training and feedback

- The program’s structure and oversight must also be flexible and responsive

- There must be accessible longitudinal mentoring support

- The format and assessment of RW must account for growing experience and competencies as well as changing motivations and priorities

- Whilst social media may be employed to widen sharing [ 149 , 155 , 160 , 169 , 194 ], privacy must be maintained [ 120 , 189 ]

On assessment

- Assessment rubrics should be used to guide the training of faculty, education of physicians and guidance of reflections [ 37 , 116 – 122 ]

- Assessments ought to take a longitudinal perspective to track the physician's progress [ 116 , 122 ]

Based on the results from this SSR in SEBA, we forward a guide catering to novice reflective practitioners (Additional file 1 ).

Limitations

This SSR in SEBA suggests that, amidst the dearth of rigorous quantitative and qualitative studies in RW and in the presence of diverse practices, approaches and settings, conclusions may not be easily drawn. Extrapolations of findings are also hindered by evidence that appraisals of RW remain largely reliant upon single time point self-reported outcomes and satisfaction surveys.

This SSR in SEBA highlights a new model for RW that requires clinical validation. However, whilst still not clinically proven, the model sketches a picture of RW’s role in PIF and the impact of reflective processes on PIF demands further study. As we look forward to engaging in this area of study, we believe further research into the longer-term effects of RW and its potential place in portfolios to guide and assess the development of physicians must be forthcoming.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to dedicate this paper to the late Dr. S Radha Krishna and A/Prof Cynthia Goh whose advice and ideas were integral to the success of this review and Thondy and Maia Olivia whose lives continue to inspire us.

The authors would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers, Dr. Ruaraidh Hill and Dr. Stephen Mason for their helpful comments which greatly enhanced this manuscript.

Abbreviations

Authors’ contributions.

All authors were involved in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, preparing the original draft of the manuscript as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

No funding was received for this review.

Availability of data and materials

Declarations.

All authors have no competing interests for this review.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Reflective writing as...

Reflective writing as an agent for change

- Related content

- Peer review

- Fiona Harding , academic foundation year 2 ,

- Rodger Charlton , professor of primary care education

- Nottingham Medical School, Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham NG7 2UH

- fiona.harding{at}nhs.net

Reflective writing is a difficult task but, done well, can be a powerful agent for change. Fiona Harding and Rodger Charlton provide some tips on how to get it right

To some doctors reflective writing may come easily. The majority, however, are not likely to approach this section of their revalidation or training portfolio with relish. But, valued or not, reflection is an essential practice for today’s doctor.

A reflective practitioner is capable of standing back and observing their actions, identifying patterns, and improving their practice as a consequence. By critiquing cases—challenging or routine—the reflective doctor can achieve the ultimate aim: improved patient care. As well as enabling the clinician to make better decisions for future patients, it can also be personally beneficial 1 and may help to avoid stress, poor job satisfaction, and burnout. 2 3

With that in mind, here are our top 10 tips for transforming trainee and appraisal portfolio entries into an invaluable tool.

1 Write, write, and write some more

Time can change perspective on clinical encounters and documenting as you go along is a useful way to capture that change. Some events continue to develop after the initial writing—an ongoing record may show how the situation has affected you and others over time, thus providing deeper clarity.

2 Read examples

Reflective writing is notoriously difficult to quantify and therefore assess. Reading examples can improve the quality of your reflections. Jenny Moon, an expert in performing and teaching reflective writing, has written a series of reflections on the same event, with varying levels of reflectivity. She highlights the difference between describing what happened compared with reflecting on it. 4

3 Find something meaningful

The literature suggests that reflecting for the sake of it probably doesn’t produce valuable results. More useful reflection will evolve from an event that held some meaning for you. Try using a broad base to select your topic. Simply asking the questions “what went well?” and “what could have been done differently?” provides a sound starting point for reflection. 5

4 Discussion

Good quality reflective work will include other people’s opinions too. Discussions with colleagues involved in the situation could reveal new aspects. This technique is vital to develop the empathetic clinician. Creating an open and safe culture for discussing rather than ignoring difficult situations improves staff wellbeing and patient care.

5 It’s not really about what happened but how it made you feel

Try not to dwell too much on the actual events, instead focus on the emotional impact for you and others involved. Don’t fall into the trap of providing intricate and irrelevant details—the colour of the registrar’s shirt probably won’t matter in the long run. If you are stuck for what to write, just answer the question, “How did it make me feel?”

6 Explore the uncomfortable

If it makes you uncomfortable then you are probably onto something. Why doesn’t it sit right? Why don’t you want to discuss it with others? Questioning the whys of your emotional response is the key to finding patterns in your practice and this insight may change your approach in the future. Doctors have been hard wired to cut the waffle and stick to the facts but going against the grain in this situation will add layers to your account and strengthen the quality of your reflection.

7 Creative writing

Literature suggests that reflective practice is linked closely with creative writing. Creative writing gives writers the opportunity to explore scenarios they may not have come across but that could be useful in the future should that situation arise. 6 The creation of characters can help the writer develop empathy with others and is a platform from which to explore what someone very different may think or feel.

Fun is not a word commonly associated with reflective practice. Challenge yourself to enjoy the process—after all, medicine doesn’t often give you a chance to get to know yourself (rather than your patients) better. Asking the question “Why?” could become both interesting and therapeutic, rather than yet another box ticking exercise.

9 Personal Development Plan

Reflection will help you identify the areas where you need to focus your learning. This will improve your PDP from a list of vague, timeless goals to specific, achievable objectives with a detailed strategy of how and when they will be completed.

10 Evidence of change

Reflection is ultimately meaningless if it doesn’t facilitate change. If you have identified changes you need to make, return later and provide details of the improvement. This might take the form of an audit or responding to feedback from patients or colleagues. Record it all in your portfolio and reflect again—has the cycle been successful or is more work needed?

Reflection is a personal experience and the best results will happen when the user creates their own process and style. However, following the tips above should give a sound base on which to build and complete those portfolio and appraisal entries.

No competing interests.

- ↵ Johns C, Burnie S. Becoming a reflective practitioner. Wiley-Blackwell, 2013 .

- ↵ Kristiansson MH, Troein M, Brorsson A. We lived and breathed medicine - then life catches up: medical students’ reflections. BMC Med Educ 2014 ; 14 : 66 . doi:10.1186/1472-6920-14-66 . pmid:24690405 . OpenUrl

- ↵ Shanafelt TD, West C, Zhao X, et al. Relationship between increased personal well-being and enhanced empathy among internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med 2005 ; 20 : 559 - 64 . doi:10.1007/s11606-005-0102-8 . pmid:16050855 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Moon J. Using story. Routledge, 2010 .

- ↵ Johna S. The Power of Reflective Writing: Narrative Medicine and Medical Education. permj 2013;17:84-85. doi: 10.7812/tpp/13-043

- ↵ Hampshire AJ, Avery AJ. What can students learn from studying medicine in literature? Med Educ 2001 ; 35 : 687 - 90 . doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00969.x . pmid:11437972 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editors Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Author Resources

- Read & Publish

- Reasons to Publish With Us

- About Postgraduate Medical Journal

- About the Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Models and theories.

- Why is reflection important?

- What to reflect on?

- Prior to writing a reflection

- How to write a reflection?

- Legalities around reflection

- < Previous

Reflection in clinical practice: guidance for postgraduate doctors in training

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Emma Richardson, Gordon Jackson Koku, Harjinder Kaul, Reflection in clinical practice: guidance for postgraduate doctors in training, Postgraduate Medical Journal , Volume 99, Issue 1178, December 2023, Pages 1295–1297, https://doi.org/10.1093/postmj/qgad063

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Reflection is a cyclical process [ 1] of understanding and analysis of one’s professional experiences, with the aim of self-improvement within future practice, if a similar event is encountered [ 2]. Reflection is also understood to have a critical role within the learning cycle [ 2] and clinicians should feel confident when engaging in its practice, as it allows them to focus not only on increasing their medical knowledge, but also on advancing nonclinical skills [ 1] such as communication, multidisciplinary work, and leadership and management. Additionally, reflection is considered essential in continuing professional development [ 3] and this skill must be developed and practised by postgraduate doctors in training (PDiT), and indeed all clinicians, during their professional career.

There are many different theories that guide the practice of reflection. An example is the Kolb cycle [ 4], which is an experimental learning theory that describes how each stage supports the next, for effective learning. There are four stages in the Kolb cycle, all of which must be completed. These are concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1469-0756

- Print ISSN 0032-5473

- Copyright © 2024 Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Skip to main content

12 Reflective practice prompts for health professionals

February 16, 2018 by Anne Marie Liebel

[This post available as a podcast episode here .]

I have heard “reflective practice” mentioned a few times, in the years I have been talking with physicians, medical educators, and public health professionals.

Dr. Tasha Wyatt, of the Educational Innovation Institute at the Medical College of Georgia, explained to me:

“Physicians are trained–very much so–to gather data, to make decisions. And reflective practice is a way to slow down that process.”

Reflective practice is certainly a term that gets thrown around. It sometimes elicits groans.

If I could say one thing about the term “reflective practice” in my experience as an educator…it would not be a nice thing to say.

A bad reputation

Let me be clear: I am a reflective practitioner. Critical reflection is the engine of my practice. I have spent most of my time in higher education trying to rescue “reflective practice” from its own reputation in my students’ imaginations.

That’s not to say this reputation is undeserved. From where I stand, there are some punitive, reductive, top-down things going on under the guise of “reflective practice.”

And I’m hearing similar statements from the health sector.

A broad spectrum

Reflective practice is a broad spectrum that covers many different understandings of and approaches to reflection (and practice).

This has advantages and disadvantages. Flexibility is essential in an approach that generally is an alternative to practices that are more didactic or directive.

There seems to be support of reflection as a skill. Health professionals all require critical-thinking and problem-solving skills, and reflective practice has been used to support these. Reflection is used to increase metacognition. It is sometimes invoked as a way to connect theory to practice, or to enhance communication. Professionals reflect in classes, in continuing education, or in communities of practice; alone, in dyads, or in small groups.

Yet this literature review points out the variation in what reflective practice means, and how it is facilitated and assessed, in medical education. This literature review finds similar results in pharmacy education, pointing out the conflicting interpretations and applications of the term ‘reflective practice.’ I highly recommend both these literature reviews for references on reflective practice in health professions.

Both also cite Donald Schön, whose highly-influential books The Reflective Practitioner and Educating the Reflective Practitioner describe and analyze reflection-in-action across multiple professions and professional contexts.

In Educating the Reflective Practitioner , Schön explains why:

[T]he problems of real-world practice do not present themselves to practitioners as well-formed structures. Indeed, they tend not to present themselves as problems at all but as messy, indeterminate situations. Often, situations are problematic in several ways at once. These indeterminate zones of practice—uncertainty, uniqueness, and value conflict—escape the canons of technical rationality. It is just these indeterminate zones of practice, however, that practitioners and critical observers of the professions have come to see with increasing clarity over the past two decades as central to professional practice. (p. 4)

What I want to share here is a key tool in reflective practice: questioning or problem-posing as a way to begin to investigate and address the “problems of real-world practice.”

“Problems of real-world practice”

If I hear ‘what could you have done differently?’ posed as a ‘reflective practice’ question one more time, I’ll scream.

So instead, I’m going to give you twelve prompts that you can ask yourself when you wish to engage in some critical reflection.

These questions are designed to get at your taken-for-granted beliefs and actions. They encourage you to problematize structures, processes, and practices (as these authors do), accepting current arrangements not as given or natural but as politically and historically situated (as these authors point out).

These questions are aimed at those times when you are educating—a patient, or a student. But they can have broader applicability. Overall, they are designed to encourage you to take a critical view of the customary practices and conventional arrangements in your practice context.

After each, there always is a follow-up question: what implications does this have for your practice? In other words, why might this matter to you and your work with patients?

- Which patients tend to draw your attention? Why do you think this is? Which patients tend to escape your notice? Why do you think this is?

- Are there patients you find it difficult to get along with , or relate to, or reach? How do you feel about this?

- What information or knowledge are you assuming patients have when they meet with you? Where would they have acquired this knowledge or information? How have you responded when they do not appear to have this knowledge or information ?

- What’s presenting a challenge to you recently when it comes to patient education, that you did not think would present a challenge?

- Did anything a patient did or said surprise you today? What was it? Why was it surprising to you? How can you let patients surprise you more often? Have you surprised yourself lately? How?

- What’s going on around you that piques your curiosity this week? That you’d like to give more time and attention to, if you could?

- When you meet with a patient, how are you talking to this person? What do you tend to think of people in this social group ? How might your conversational dynamics be based on biases and stereotypes?

- If you broke down the time you spent this week on different tasks and put it on a chart or graph, what would it look like? To what extent does this match your idea of a successful or productive use of your time?

- What have you done this week that you were proud of, no matter how simple it might sound?

- Are there times you are unsure of what you are communicating to a patient or colleague? How do you deal with this?

- If you could wave a magic wand and give yourself the insights, knowledge, dispositions or skills you need in order to succeed this week, what would you give yourself?

- What clever hacks , little-known tricks, or productivity boosts have you discovered lately? What might these be telling you about yourself, or your context?

Again, the important question at the end of each set is always: what implications does this have for your practice?

“Is reflection safe?”

Reflection is an important process for any profession. Yet, at the same time, health care providers are held to such high expectations that reflection can seem risky, as recent events in the UK illustrate.

“Is reflection safe?” Dr. Wyatt wondered aloud, as we were talking. “If so, under what conditions? If not, under what conditions?”

Of course, no one can eliminate the stress and messiness of practice. Reflection, when critically oriented, is designed to press into–and not deny–the stress and messiness of practice. It is an irreplaceable, powerful tool that invites professionals to imagine other possible practices, roles, and relationships.

If you are interested in taking your language use seriously, why not start with your metaphors ? This workshop shows you how to break down the metaphors you use, understand their cognitive and affective aspects, and evaluate them in use. On demand, right on this site .

Take action on health equity

Subscribe to our newsletter

Lots of research-based resources. No deficit perspectives.

- Open access

- Published: 09 January 2023

A systematic scoping review of reflective writing in medical education

- Jia Yin Lim 1 , 2 ,

- Simon Yew Kuang Ong 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Chester Yan Hao Ng 1 , 2 ,

- Karis Li En Chan 1 , 2 ,

- Song Yi Elizabeth Anne Wu 1 , 2 ,

- Wei Zheng So 1 , 2 ,

- Glenn Jin Chong Tey 1 , 2 ,

- Yun Xiu Lam 1 , 2 ,

- Nicholas Lu Xin Gao 1 , 2 ,

- Yun Xue Lim 1 , 2 ,

- Ryan Yong Kiat Tay 1 , 2 ,

- Ian Tze Yong Leong 1 , 2 ,

- Nur Diana Abdul Rahman 4 ,

- Min Chiam 4 ,

- Crystal Lim 6 ,

- Gillian Li Gek Phua 2 , 5 , 7 ,

- Vengadasalam Murugam 2 , 5 ,

- Eng Koon Ong 2 , 4 , 5 , 8 &

- Lalit Kumar Radha Krishna 1 , 2 , 4 , 5 , 9 , 10

BMC Medical Education volume 23 , Article number: 12 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

6116 Accesses

17 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Reflective writing (RW) allows physicians to step back, review their thoughts, goals and actions and recognise how their perspectives, motives and emotions impact their conduct. RW also helps physicians consolidate their learning and boosts their professional and personal development. In the absence of a consistent approach and amidst growing threats to RW’s place in medical training, a review of theories of RW in medical education and a review to map regnant practices, programs and assessment methods are proposed.

A Systematic Evidence-Based Approach guided Systematic Scoping Review (SSR in SEBA) was adopted to guide and structure the two concurrent reviews. Independent searches were carried out on publications featured between 1st January 2000 and 30th June 2022 in PubMed, Embase, PsychINFO, CINAHL, ERIC, ASSIA, Scopus, Google Scholar, OpenGrey, GreyLit and ProQuest. The Split Approach saw the included articles analysed separately using thematic and content analysis. Like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, the Jigsaw Perspective combined the themes and categories identified from both reviews. The Funnelling Process saw the themes/categories created compared with the tabulated summaries. The final domains which emerged structured the discussion that followed.

A total of 33,076 abstracts were reviewed, 1826 full-text articles were appraised and 199 articles were included and analysed. The domains identified were theories and models, current methods, benefits and shortcomings, and recommendations.

Conclusions

This SSR in SEBA suggests that a structured approach to RW shapes the physician’s belief system, guides their practice and nurtures their professional identity formation. In advancing a theoretical concept of RW, this SSR in SEBA proffers new insight into the process of RW, and the need for longitudinal, personalised feedback and support.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Reflective practice in medicine allows physicians to step back, review their actions and recognise how their thoughts, feelings and emotions affect their decision-making, clinical reasoning and professionalism [ 1 ]. This approach builds on Dewey [ 2 ], Schon [ 3 , 4 ], Kolb [ 5 ], Boud et al. [ 6 ] and Mezirow [ 7 ]’s concepts of critical self-examination. It sees new insights drawn from the physician’s experiences and considers how assumptions may integrate into their current values, beliefs and principles (henceforth belief system) [ 8 , 9 ].

Teo et al. [ 10 ] build on this concept of reflective practice. The authors suggest that the physician’s belief system informs and is informed by their self-concepts of identity which are in turn rooted in their self-concepts of personhood - how they conceive what makes them who they are [ 11 ]. This posit not only ties reflective practice to the shaping of the physician’s moral and ethical compass but also offers evidence of it's role in their professional identity formation (PIF) [ 8 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. With PIF [ 8 , 24 ] occupying a central role in medical education, these ties underscore the critical importance placed on integrating reflective practice in medical training.

Perhaps the most common form of reflective practice in medical education is reflective writing (RW) [ 25 ]. Identified as one of the distinct approaches used to achieve integrated learning, education, curriculum and teaching [ 26 ], RW already occupies a central role in guiding and supporting longitudinal professional development [ 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Its ability to enhance self-monitoring and self-regulation of decisional paradigms and conduct has earned RW a key role in competency-based medical practice and continuing professional development [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ].

However, the absence of consistent guiding principles, dissonant practices, variable structuring and inadequate assessments have raised concerns as to RW’s efficacy and place in medical training [ 25 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. A Systematic Scoping Review is proposed to map current understanding of RW programs. It is hoped that this SSR will also identify gaps in knowledge and regnant practices, programs and assessment methods to guide the design of RW programs.

Methodology

A Systematic Scoping Review (SSR) is employed to map the employ, structuring and assessment of RW in medical education. An SSR-based review is especially useful in attending to qualitative data that does not lend itself to statistical pooling [ 40 , 41 , 42 ] whilst its broad flexible approach allows the identification of patterns, relationships and disagreements [ 43 ] across a wide range of study formats and settings [ 44 , 45 ].

To synthesise a coherent narrative from the multiple accounts of reflective writing, we adopt Krishna’s Systematic Evidence-Based Approach (SEBA) [ 10 , 15 , 21 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 ]. A SEBA-guided Systematic Scoping Review (SSR in SEBA) [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 50 , 53 , 54 , 55 ] facilitates reproducible, accountable and transparent analysis of patterns, relationships and disagreements from multiple angles [ 56 ].

The SEBA process (Fig. 1 ) comprises the following elements: 1) Systematic Approach, 2) Split Approach, 3) Jigsaw Perspective, 4) Funnelling Process, 5) Analysis of data and non-data driven literature, and 6) Synthesis of SSR in SEBA [ 10 , 15 , 21 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ] . Every stage was overseen by a team of experts that included medical librarians from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSoM) at the National University of Singapore, and local educational experts and clinicians at YLLSoM, Duke-NUS Medical School, Assisi Hospice, Singapore General Hospital, National Cancer Centre Singapore and Palliative Care Institute Liverpool.

The SEBA Process

STAGE 1 of SEBA: Systematic Approach

Determining the title and background of the review.

Ensuring a systematic approach, the expert team and the research team agreed upon the overall goals of the review. Two separate searches were performed, one to look at the theories of reflection in medical education, and another to review regnant practices, programs, and assessment methods used in reflective writing in medical education. The PICOs is featured in Table 1 .

Identifying the research question

Guided by the Population Concept, Context (PCC) elements of the inclusion criteria and through discussions with the expert team, the research question was determined to be: “ How is reflective writing structured, assessed and supported in medical education? ” The secondary research question was “ How might a reflective writing program in medical education be structured? ”

Inclusion criteria

All study designs including grey literature published between 1st January 2000 to 30th June 2022 were included [ 61 , 62 ]. We also consider data on medical students and physicians from all levels of training (henceforth broadly termed as physicians).

Ten members of the research team carried out independent searches using seven bibliographic databases (PubMed, Embase, PsychINFO, CINAHL, ERIC, ASSIA, Scopus) and four grey literature databases (Google Scholar, OpenGrey, GreyLit, ProQuest). Variations of the terms “reflective writing”, “physicians and medical students”, and “medical education” were applied.

Extracting and charting

Titles and abstracts were independently reviewed by the research team to identify relevant articles that met the inclusion criteria set out in Table 1 . Full-text articles were then filtered and proposed. These lists were discussed at online reviewer meetings and Sandelowski and Barroso [ 63 ]’s approach to ‘negotiated consensual validation’ was used to achieve consensus on the final list of articles to be included.

Stage 2 of SEBA: Split Approach

The Split Approach was employed to enhance the trustworthiness of the SSR in SEBA [ 64 , 65 ]. Data from both searches were analysed by three independent groups of study team members.

The first group used Braun and Clarke [ 66 ]’s approach to thematic analysis. Phase 1 consisted of ‘actively’ reading the included articles to find meaning and patterns in the data. The analysis then moved to Phase 2 where codes were constructed. These codes were collated into a codebook and analysed using an iterative step-by-step process. As new codes emerge, previous codes and concepts were incorporated. In Phase 3, codes and subthemes were organised into themes that best represented the dataset. An inductive approach allowed themes to be “defined from the raw data without any predetermined classification” [ 67 ]. In Phase 4, these themes were then further refined to best depict the whole dataset. In Phase 5, the research team discussed the results and consensus was reached, giving rise to the final themes.

The second group employed Hsieh and Shannon [ 68 ]’s approach to directed content analysis. Categories were drawn from Mann et al. [ 9 ]’s article, “Reflection and Reflective Practice in Health Professions Education: A Systematic Review” and Wald and Reis [ 69 ]’s article “Beyond the Margins: Reflective Writing and Development of Reflective Capacity in Medical Education”.

The third group created tabulated summaries in keeping with recommendations drawn from Wong et al. [ 56 ]’s "RAMESES Publication Standards: Meta-narrative Reviews" and Popay et al. [ 70 ]’s “Guidance on the C onduct of N arrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews”. The tabulated summaries served to ensure that key aspects of included articles were not lost.

Stage 3 of SEBA: Jigsaw Perspective

The Jigsaw Perspective [ 71 , 72 ] saw the findings of both searches combined. Here, overlaps and similarities between the themes and categories from the two searches were combined to create themes/categories. The themes and subthemes were compared with the categories and subcategories identified, and similarities were verified by comparing the codes contained within them. Individual subthemes and subcategories were combined if they were complementary in nature.

Stage 4 of SEBA: Funnelling Process

The Funnelling Process saw the themes/categories compared with the tabulated summaries to determine the consistency of the domains created, forming the basis of the discussion.

Stage 5: Analysis of data and non-data driven literature

Amidst concerns that data from grey literature which were neither peer-reviewed nor necessarily evidence-based may bias the synthesis of the discussion, the research team separately thematically analysed the included grey literature. These themes were compared with themes from data-driven or research-based peer-reviewed data and were found to be the same and thus unlikely to have influenced the analysis.

Stage 6: Synthesis of SSR in SEBA

The Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) Collaboration Guide and the Structured approach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis (STORIES) were used to guide the discussion.

A total of 33,076 abstracts were reviewed from the two separate searches on theories of reflection in medical education, and on regnant practices, programs and assessments of RW programs in medical education. A total of 1826 full-text articles were appraised from the separate searches, and 199 articles were included and analysed. The PRISMA Flow Chart may be found in Fig. 2 a and b. The domains identified when combining the findings of the two separate searches were 1) Theories and Models, 2) Current Methods, 3) Benefits and Shortcomings and 4) Recommendations.

a PRISMA Flow Chart (Search Strat #1: Theories of Reflection in Medical Education). b PRISMA Flow Chart (Search Strat #2: Reflective Writing in Medical Education)

Domain 1: Theories and Models

Many current theories and models surrounding RW in medical education are inspired by Kolb’s Learning Cycle [ 5 ] (Table 2 ). These theories focus on descriptions of areas of reflection; evaluations of experiences and emotions; how events may be related to previous experiences; knowledge critiques of their impact on thinking and practice; integration of learning points; and the physician’s willingness to apply lessons learnt [ 6 , 73 , 74 , 75 ]. In addition, some of these theories also consider the physician’s self-awareness, ability and willingness to reflect [ 76 ], contextual factors related to the area of reflection [ 4 , 77 ] and the opportunity to reflect effectively within a supportive environment [ 78 , 79 ]. Ash and Clayton's DEAL Model recommends inclusion of information from all five senses [ 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 ]. Johns's Model of Structured Reflection [ 84 ] advocates giving due consideration to internal and external influences upon the event being evaluated. Rodgers [ 39 ] underlines the need for appraisal of the suppositions and assumptions that precipitate and accompany the effects and responses that may have followed the studied event. Griffiths and Tann [ 75 ], Mezirow [ 77 ], Kim [ 85 ], Roskos et al. [ 86 ], Burnham et al. [ 87 ], Korthagen and Vasalos [ 78 ] and Koole et al. [ 74 ] build on Dewey [ 2 ] and Kolb [ 5 ]’s notion of creating and experimenting with a ‘working hypothesis’. These models also propose that the lessons learnt from experimentations should be critiqued as part of a reiterative process within the reflective cycle. Underlining the notion of the reflective cycle and the long-term effects of RW, Pearson and Smith [ 88 ] suggest that reflections should be carried out regularly to encourage longitudinal and holistic reflections on all aspects of the physician’s personal and professional life.

Regnant theories shape assessments of RW (Table 3 ). This extends beyond Thorpe [ 96 ]’s study which categorises reflective efforts into ‘non-reflectors’, ‘reflectors’, ‘critical reflectors’, and focuses on their process, structure, depth and content. van Manen [ 97 ], Plack et al. [ 98 ], Rogers et al. [ 99 ] and Makarem et al. [ 100 ] begin with evaluating the details of the events. Kim’s Critical Reflective Inquiry Model [ 85 ] and Bain’s 5Rs Reflective Framework [ 101 ] also consider characterisations of emotions involved. Other models appraise the intentions behind actions and thoughts [ 85 ], the factors precipitating the event [ 101 ] and meaning-making [ 85 ]. Other theories consider links with previous experiences [ 100 ], the integration of thoughts, justifications and perspectives [ 99 ], and the hypothesising of future strategies [ 98 ].

Domain 2: Current methods of structuring RW programs

Current programs focus on supporting the physician throughout the reflective process. Whilst due consideration is given to the physician’s motivations, insight, experiences, capacity and capabilities [ 25 , 96 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 ], programs also endeavour to ensure appropriate selection and training of physicians intending to participate in RW. Efforts are also made to align expectations, and guide and structure the RW process [ 37 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 , 122 ]. Physicians are provided with frameworks [ 76 , 79 , 105 , 123 , 124 ], rubrics [ 99 , 123 , 125 , 126 ], examples of the expected quality and form of reflection [ 96 , 115 , 116 ], and how to include emotional and contextual information in their responses [ 121 , 127 , 128 , 129 ].

Other considerations are enclosed in Table 4 including frequency, modality and the manner in which RW is assessed.

Domain 3: Benefits and Shortcomings

The benefits of RW are rarely described in detail and may be divided into personal and professional benefits as summarised in Table 5 for ease of review. From a professional perspective, RW improves learning [ 96 , 112 , 119 , 147 , 157 , 170 , 179 , 185 , 186 , 187 , 188 , 189 , 190 , 191 , 192 ], facilitates continuing medical education [ 119 , 128 , 173 , 174 , 193 , 194 , 195 ], inculcates moral, ethical, professional and social standards and expectations [ 118 , 156 , 160 ], improves patient care [ 29 , 120 , 129 , 131 , 135 , 142 , 194 , 196 , 197 , 198 , 199 ] and nurtures PIF [ 150 , 157 , 172 , 191 , 200 ].

From a personal perspective, RW increases self-awareness [ 114 , 127 , 137 , 161 , 166 , 179 , 185 , 202 , 216 ], self-advancement [ 9 , 131 , 134 , 150 , 168 , 174 , 195 , 205 , 217 , 229 ], facilitates understanding of individual strengths, weaknesses and learning needs [ 112 , 119 , 150 , 152 , 170 , 218 , 219 ], promotes a culture of self-monitoring, self-improvement [ 130 , 172 , 173 , 185 , 193 , 198 , 201 , 210 , 211 ], developing critical perspectives of self [ 193 , 223 ] and nurtures resilience and better coping [ 154 , 160 , 206 ]. RW also guides shifts in thinking and perspectives [ 148 , 149 , 156 , 203 , 207 , 208 ] and focuses on a more holistic appreciation of decision-making [ 37 , 118 , 126 , 174 , 177 , 194 , 196 , 199 , 200 , 224 , 225 , 226 ] and their ramifications [ 37 , 112 , 116 , 130 , 131 , 141 , 154 , 179 , 193 , 194 , 196 , 204 , 207 , 218 , 230 ].

Table 6 combines current lists of the shortcomings of RW. These limitations may be characterised by individual, structural and assessment styles.

It is suggested that RW does not cater to the different learning styles [ 220 , 232 ], cultures [ 190 ], roles, values, processes and expectations of RW [ 114 , 129 , 135 , 138 , 142 , 209 , 227 , 234 ], and physicians' differing levels of self-awareness [ 29 , 79 , 119 , 176 , 188 , 226 , 231 , 236 ], motivations [ 29 , 119 , 136 , 138 , 157 , 161 , 167 , 168 , 169 , 176 , 181 , 193 , 196 , 226 , 232 , 233 ] and willingness to engage in RW [ 37 , 114 , 136 , 149 , 160 , 183 ]. RW is also limited by poorly prepared physicians and misaligned expectations whilst a lack of privacy and a safe setting may precipitate physician anxiety at having their private thoughts shared [ 129 , 149 , 209 , 231 ]. RW is also compromised by a lack of faculty training [ 143 , 145 , 239 ], mentoring support [ 37 , 50 , 119 , 133 , 196 ] and personalised feedback [ 50 , 114 , 136 , 167 , 229 ] which may lead to self-censorship [ 37 , 114 , 136 , 149 , 160 , 183 ] and an unwillingness to address negative emotions arising from reflecting on difficult events [ 114 , 168 , 176 , 193 , 230 ], circumventing the reflective process [ 118 , 142 , 165 , 196 ] .

Variations in assessment styles [ 9 , 115 , 157 , 161 , 166 , 193 , 209 ], depth [ 29 , 105 , 118 , 126 , 177 , 207 ] and content [ 37 , 114 , 136 , 149 , 169 , 183 , 196 ], and pressures to comply with graded assessments [ 114 , 115 , 118 , 129 , 138 , 143 , 149 , 155 , 157 , 209 , 232 , 237 , 238 ] also undermine efforts of RW.

Domain 4. Recommendations

In the face of practice variations and challenges, there have been several recommendations on improving practice.

Boosting awareness of RW

Acknowledging the importance of a physician’s motivations, willingness and judgement [ 37 ], an RW program must acquaint physicians with information on RW’s role [ 128 ], program expectations, the form, frequency and assessments of RW and the support available to them [ 130 , 132 , 150 , 154 , 242 ] and its benefits to their professional and personal development [ 96 , 227 ] early in their training programs [ 115 , 220 , 242 , 243 ]. Physicians should also be trained on the knowledge and skills required to meet these expectations [ 1 , 37 , 135 , 151 , 160 , 215 , 244 , 245 ].

A structured program and environment

Recognising that effective RW requires a structured program. Recommendations focus on three aspects of the program design [ 132 ]. One is the need for trained faculty [ 9 , 115 , 219 , 220 , 230 , 233 , 242 , 246 ], accessible communications, protected time for RW and debriefs [ 125 ], consistent mentoring support [ 190 ] and assessment processes [ 247 ]. This will facilitate trusting relationships between physicians and faculty [ 30 , 114 , 168 , 196 , 231 , 233 ]. Two, the need to nurture an open and trusting environment where physicians will be comfortable with sharing their reflections [ 96 , 128 ], discussing their emotions, plans [ 127 , 248 ] and receiving feedback [ 9 , 37 , 79 , 114 , 119 , 128 , 135 , 173 , 176 , 179 , 190 , 237 ]. This may be possible in a decentralised classroom setting [ 163 , 190 ]. Three, RW should be part of the formal curriculum and afforded designated time. RW should be initiated early and longitudinally along the training trajectory [ 116 , 122 ].

Adjuncts to RW programs

Several approaches have been suggested to support RW programs. These include collaborative reflection, in-person discussion groups to share written reflections [ 128 , 131 , 138 , 196 , 199 , 231 , 249 ] and reflective dialogue to exchange feedback [ 119 ], use of social media [ 149 , 160 , 169 , 194 , 204 , 230 ], video-recorded observations and interactions for users to review and reflect on later [ 133 ]. Others include autobiographical reflective avenues in addition to practice-oriented reflection [ 137 ], support groups to help meditate stress or emotions triggered by reflections [ 249 ] and mixing of reflective approaches to meet different learning styles [ 169 , 250 ].

In answering the primary research question, “How is reflective writing structured, assessed and supported in medical education?” , this SSR in SEBA highlights several key insights. To begin, RW involves integrating the insights of an experience or point of reflection (henceforth ‘event’) into the physician’s currently held values, beliefs and principles (henceforth belief system). Recognising that an ‘event’ has occurred and that it needs deeper consideration highlights the physician’s sensitivity . Recognising the presence of an ‘event’ triggers an evaluation as to the urgency in which it needs to be addressed, where it stands amongst other ‘events’ to be addressed and whether the physician has the appropriate skills, support and time to address the ‘event’. This reflects the physician’s judgement . The physician must then determine whether they are willing to proceed and the ramifications involved. These include ethical, medical, clinical, administrative, organisational, sociocultural, legal and professional considerations. This is then followed by contextualising them to their own personal, psychosocial, clinical, professional, research, academic, and situational setting. Weighing these amidst competing ‘events’ underlines the import of the physician’s ability to ‘balance’ considerations. Creating and experimenting on their ‘working hypothesis’ highlights their ‘ability’, whilst how they evaluate the effects of their experimentation and how they adapt their practice underscores their ‘ responsiveness ’ [ 2 , 5 , 74 , 75 , 77 , 78 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 90 ].