We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

A collection of essays

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

538 Previews

22 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

EPUB and PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station01.cebu on March 14, 2020

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Authors & Events

Recommendations

- New & Noteworthy

- Bestsellers

- Popular Series

- The Must-Read Books of 2023

- Popular Books in Spanish

- Coming Soon

- Literary Fiction

- Mystery & Thriller

- Science Fiction

- Spanish Language Fiction

- Biographies & Memoirs

- Spanish Language Nonfiction

- Dark Star Trilogy

- Ramses the Damned

- Penguin Classics

- Award Winners

- The Parenting Book Guide

- Books to Read Before Bed

- Books for Middle Graders

- Trending Series

- Magic Tree House

- The Last Kids on Earth

- Planet Omar

- Beloved Characters

- The World of Eric Carle

- Llama Llama

- Junie B. Jones

- Peter Rabbit

- Board Books

- Picture Books

- Guided Reading Levels

- Middle Grade

- Activity Books

- Trending This Week

- Top Must-Read Romances

- Page-Turning Series To Start Now

- Books to Cope With Anxiety

- Short Reads

- Anti-Racist Resources

- Staff Picks

- Memoir & Fiction

- Features & Interviews

- Emma Brodie Interview

- James Ellroy Interview

- Nicola Yoon Interview

- Qian Julie Wang Interview

- Deepak Chopra Essay

- How Can I Get Published?

- For Book Clubs

- Reese's Book Club

- Oprah’s Book Club

- happy place " data-category="popular" data-location="header">Guide: Happy Place

- the last white man " data-category="popular" data-location="header">Guide: The Last White Man

- Authors & Events >

- Our Authors

- Michelle Obama

- Zadie Smith

- Emily Henry

- Amor Towles

- Colson Whitehead

- In Their Own Words

- Qian Julie Wang

- Patrick Radden Keefe

- Phoebe Robinson

- Emma Brodie

- Ta-Nehisi Coates

- Laura Hankin

- Recommendations >

- 21 Books To Help You Learn Something New

- The Books That Inspired "Saltburn"

- Insightful Therapy Books To Read This Year

- Historical Fiction With Female Protagonists

- Best Thrillers of All Time

- Manga and Graphic Novels

- happy place " data-category="recommendations" data-location="header">Start Reading Happy Place

- How to Make Reading a Habit with James Clear

- Why Reading Is Good for Your Health

- 10 Facts About Taylor Swift

- New Releases

- Memoirs Read by the Author

- Our Most Soothing Narrators

- Press Play for Inspiration

- Audiobooks You Just Can't Pause

- Listen With the Whole Family

Look Inside

Orwell: Essays

Introduction by John Carey

By George Orwell Introduction by John Carey Selected by John Carey

Part of everyman's library contemporary classics series, category: essays & literary collections | classic nonfiction | literary criticism | philosophy.

Oct 15, 2002 | ISBN 9780375415036 | 5 x 8 --> | ISBN 9780375415036 --> Buy

Buy from Other Retailers:

Oct 15, 2002 | ISBN 9780375415036

Buy the Hardcover:

- Barnes & Noble

- Books A Million

- Powell’s

About Orwell: Essays

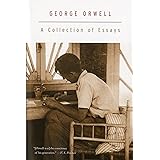

A generous and varied selection–the only hardcover edition available–of the literary and political writings of one of the greatest essayists of the twentieth century.

Although best known as the author of Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-four , George Orwell left an even more lastingly significant achievement in his voluminous essays, which dealt with all the great social, political, and literary questions of the day and exemplified an incisive prose style that is still universally admired. Included among the more than 240 essays in this volume are Orwell’s famous discussion of pacifism, “My Country Right or Left”; his scathingly complicated views on the dirty work of imperialism in “Shooting an Elephant”; and his very firm opinion on how to make “A Nice Cup of Tea.”

In his essays, Orwell elevated political writing to the level of art, and his motivating ideas–his desire for social justice, his belief in universal freedom and equality, and his concern for truth in language–are as enduringly relevant now, a hundred years after his birth, as ever.

Also in Everyman’s Library Contemporary Classics Series

Also by George Orwell

About George Orwell

George Orwell (1903–1950) served with the Imperial Police in Burma, fought with the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War, and was a member of the Home Guard and a writer for the BBC during World War II. He is the… More about George Orwell

Product Details

Category: essays & literary collections | classic nonfiction | literary criticism | philosophy, you may also like.

Selected Non-Fictions

America and Americans and Selected Nonfiction

Selected Essays of Gore Vidal

Working Days

Portraits and Observations

Changing My Mind

Life Sentences

Why I Write

The Glorious American Essay

The Devil Finds Work

“Orwell is the most influential political writer of the twentieth century…He gives us a gritty, personal example of how to engage as a writer in politics.” – New York Review of Books “[Orwell] evolved, in his seemingly offhand way, the clearest and most compelling English prose style this century…But of course he was more than just a great writer. We need him today because [of] his passion for the truth.” – The Sunday Times (London) “Had Orwell lived to a full term, he might well have gone on to become the greatest modern literary critic in the language. But he lived more than long enough to make writing about politics a branch of the humanities, setting a standard of civilized response to the intractably complex texture of life.” – The New Yorker “The real reason we read Orwell is because his own fault-line, his fundamental schism, his hybridity, left him exceptionally sensitive to the fissure–which is everywhere apparent–between what ought to be the case and what actually is the case. He says the unsayable.” – Financial Times “Orwell was the conscience of his generation.” –V. S. Pritchett

Visit other sites in the Penguin Random House Network

Raise kids who love to read

Today's Top Books

Want to know what people are actually reading right now?

An online magazine for today’s home cook

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

George Orwell

Select a format:

About the author, more in this series.

Sign up to the Penguin Newsletter

By signing up, I confirm that I'm over 16. To find out what personal data we collect and how we use it, please visit our Privacy Policy

The Best George Orwell Essays Everyone Should Read

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

George Orwell (1903-50) is known around the world for his satirical novella Animal Farm and his dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four , but he was arguably at his best in the essay form. Below, we’ve selected and introduced ten of Orwell’s best essays for the interested newcomer to his non-fiction, but there are many more we could have added. What do you think is George Orwell’s greatest essay?

1. ‘ Why I Write ’.

This 1946 essay is notable for at least two reasons: one, it gives us a neat little autobiography detailing Orwell’s development as a writer; and two, it includes four ‘motives for writing’ which break down as egoism (wanting to seem clever), aesthetic enthusiasm (taking delight in the sounds of words etc.), the historical impulse (wanting to record things for posterity), and the political purpose (wanting to ‘push the world in a certain direction’).

2. ‘ Politics and the English Language ’.

The English language is ‘in a bad way’, Orwell argues in this famous essay from 1946. As its title suggests, Orwell identifies a link between the (degraded) English language of his time and the degraded political situation: Orwell sees modern political discourse as being less a matter of words chosen for their clear meanings than a series of stock phrases slung together.

Orwell concludes with six rules or guidelines for political writers and essayists, which include: never use a long word when a short one will do, or a specialist or foreign term when a simpler English one should suffice.

We have analysed this classic essay here .

3. ‘ Shooting an Elephant ’.

This is an early Orwell essay, from 1936. In it, he recalls his (possibly fictionalised) experiences as a police officer in Burma, when he had to shoot an elephant that had got out of hand. Orwell extrapolates from this one event, seeing it as a microcosm of imperialism, wherein the coloniser loses his humanity and freedom through oppressing others.

We have analysed this essay here .

4. ‘ Decline of the English Murder ’.

In this 1946 essay, Orwell writes about the British fascination with murder, focusing in particular on the period of 1850-1925, which Orwell identifies as the golden age or ‘great period in murder’ in the media and literature. But what has happened to murder in the British newspapers?

Orwell claims that the Second World War has desensitised people to brutal acts of killing, but also that there is less style and art in modern murders. Oscar Wilde would no doubt agree with Orwell’s point of view!

5. ‘ Confessions of a Book Reviewer ’.

This 1946 essay makes book-reviewing as a profession or trade – something that seems so appealing and aspirational to many book-lovers – look like a life of drudgery. Why, Orwell asks, does virtually every book that’s published have to be reviewed? It would be best, he argues, to be more discriminating and devote more column inches to the most deserving of books.

6. ‘ A Hanging ’.

This is another Burmese recollection from Orwell, and a very early work, dating from 1931. Orwell describes a condemned criminal being executed by hanging, using this event as a way in to thinking about capital punishment and how, as Orwell put it elsewhere, a premeditated execution can seem more inhumane than a thousand murders.

We discuss this Orwell essay in more detail here .

7. ‘ The Lion and the Unicorn ’.

Subtitled ‘Socialism and the English Genius’, this is another essay Orwell wrote about Britain in the wake of the outbreak of the Second World War. Published in 1941, this essay takes its title from the heraldic symbols for England (the lion) and Scotland (the unicorn). Orwell argues that some sort of socialist revolution is needed to wrest Britain out of its outmoded ways and an overhaul of the British class system will help Britain to defeat the Nazis.

The long essay contains a section, ‘England Your England’, which is often reprinted as a standalone essay, written as the German bomber planes were whizzing overhead during the Blitz of 1941. This part of the essay is a critique of blind English patriotism during wartime and an attempt to pin down ‘English’ values at a time when England itself was under threat from Nazi invasion.

8. ‘ My Country Right or Left ’.

This 1940 essay shows what a complex and nuanced thinker Orwell was when it came to political labels such as ‘left-wing’ and ‘right-wing’. Although Orwell was on the left, he also held patriotic (although not exactly fervently nationalistic) attitudes towards England which many of his comrades on the left found baffling.

As with ‘England Your England’ above, the wartime context is central to Orwell’s argument, and lends his discussion of the relationship between left-wing politics and patriotic values an urgency and immediacy.

9. ‘ Bookshop Memories ’.

As well as writing on politics and being a writer, Orwell also wrote perceptively about readers and book-buyers – as in this 1936 essay, published the same year as his novel Keep the Aspidistra Flying , which combined both bookshops and writers (the novel focuses on Gordon Comstock, an aspiring poet).

In ‘Bookshop Memories’, reflecting on his own time working as an assistant in a bookshop, Orwell divides those who haunt bookshops into various types: the snobs after a first edition, the Oriental students, and so on.

10. ‘ A Nice Cup of Tea ’.

Orwell didn’t just write about literature and politics. He also wrote about things like the perfect pub, and how to make the best cup of tea, for the London Evening Standard in the late 1940s. Here, in this essay from 1946, Orwell offers eleven ‘golden rules’ for making a tasty cuppa, arguing that people disagree vehemently how to make a perfect cup of tea because it is one of the ‘mainstays of civilisation’. Hear, hear.

3 thoughts on “The Best George Orwell Essays Everyone Should Read”

Thanks, Orwell was a master at combining wisdom and readability. I also like his essay on Edward Lear, although some of his observations are very much of their time: https://edwardleartrail.wordpress.com/2018/10/16/george-orwell-on-edward-lear/

The Everyman edition of Orwell’s essays (1200 pages !) is my desert island book. I like Shooting the Elephant altho Julian Barnes seems to believe this is fictitious. Is this still a live debate ?

- Pingback: The Best George Orwell Essays Everyone Should Read

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from interesting literature.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- About George Orwell

- Partners and Sponsors

- Accessibility

- Upcoming events

- The Orwell Festival

- The Orwell Memorial Lectures

- Books by Orwell

- Essays and other works

- Encountering Orwell

- Orwell Live

- About the prizes

- Reporting Homelessness

- Enter the Prizes

- Previous winners

- Orwell Fellows

- Introduction

- Enter the Prize

- Terms and Conditions

- Volunteering

- About Feedback

- Responding to Feedback

- Start your journey

- Inspiration

- Find Your Form

- Start Writing

- Reading Recommendations

- Previous themes

- Our offer for teachers

- Lesson Plans

- Events and Workshops

- Orwell in the Classroom

- GCSE Practice Papers

- The Orwell Youth Fellows

- Paisley Workshops

The Orwell Foundation

- The Orwell Prizes

- The Orwell Youth Prize

Why I Write

This material remains under copyright in some jurisdictions, including the US, and is reproduced here with the kind permission of the Orwell Estate . The Orwell Foundation is an independent charity – please consider making a donation or becoming a Friend of the Foundation to help us maintain these resources for readers everywhere.

From a very early age, perhaps the age of five or six, I knew that when I grew up I should be a writer. Between the ages of about seventeen and twenty-four I tried to abandon this idea, but I did so with the consciousness that I was outraging my true nature and that sooner or later I should have to settle down and write books.

I was the middle child of three, but there was a gap of five years on either side, and I barely saw my father before I was eight. For this and other reasons I was somewhat lonely, and I soon developed disagreeable mannerisms which made me unpopular throughout my schooldays. I had the lonely child’s habit of making up stories and holding conversations with imaginary persons, and I think from the very start my literary ambitions were mixed up with the feeling of being isolated and undervalued. I knew that I had a facility with words and a power of facing unpleasant facts, and I felt that this created a sort of private world in which I could get my own back for my failure in everyday life. Nevertheless the volume of serious – i.e. seriously intended – writing which I produced all through my childhood and boyhood would not amount to half a dozen pages. I wrote my first poem at the age of four or five, my mother taking it down to dictation. I cannot remember anything about it except that it was about a tiger and the tiger had ‘chair-like teeth’ – a good enough phrase, but I fancy the poem was a plagiarism of Blake’s ‘Tiger, Tiger’. At eleven, when the war or 1914-18 broke out, I wrote a patriotic poem which was printed in the local newspaper, as was another, two years later, on the death of Kitchener. From time to time, when I was a bit older, I wrote bad and usually unfinished ‘nature poems’ in the Georgian style. I also, about twice, attempted a short story which was a ghastly failure. That was the total of the would-be serious work that I actually set down on paper during all those years.

However, throughout this time I did in a sense engage in literary activities. To begin with there was the made-to-order stuff which I produced quickly, easily and without much pleasure to myself. Apart from school work, I wrote vers d’occasion , semi-comic poems which I could turn out at what now seems to me astonishing speed – at fourteen I wrote a whole rhyming play, in imitation of Aristophanes, in about a week – and helped to edit school magazines, both printed and in manuscript. These magazines were the most pitiful burlesque stuff that you could imagine, and I took far less trouble with them than I now would with the cheapest journalism. But side by side with all this, for fifteen years or more, I was carrying out a literary exercise of a quite different kind: this was the making up of a continuous “story” about myself, a sort of diary existing only in the mind. I believe this is a common habit of children and adolescents. As a very small child I used to imagine that I was, say, Robin Hood, and picture myself as the hero of thrilling adventures, but quite soon my “story” ceased to be narcissistic in a crude way and became more and more a mere description of what I was doing and the things I saw. For minutes at a time this kind of thing would be running through my head: ‘He pushed the door open and entered the room. A yellow beam of sunlight, filtering through the muslin curtains, slanted on to the table, where a matchbox, half-open, lay beside the inkpot. With his right hand in his pocket he moved across to the window. Down in the street a tortoiseshell cat was chasing a dead leaf,’ etc., etc. This habit continued until I was about twenty-five, right through my non-literary years. Although I had to search, and did search, for the right words, I seemed to be making this descriptive effort almost against my will, under a kind of compulsion from outside. The ‘story’ must, I suppose, have reflected the styles of the various writers I admired at different ages, but so far as I remember it always had the same meticulous descriptive quality.

When I was about sixteen I suddenly discovered the joy of mere words, i.e. the sounds and associations of words. The lines from Paradise Lost –

So hee with difficulty and labour hard Moved on: with difficulty and labour hee,

which do not now seem to me so very wonderful, sent shivers down my backbone; and the spelling ‘hee’ for ‘he’ was an added pleasure. As for the need to describe things, I knew all about it already. So it is clear what kind of books I wanted to write, in so far as I could be said to want to write books at that time. I wanted to write enormous naturalistic novels with unhappy endings, full of detailed descriptions and arresting similes, and also full of purple passages in which words were used partly for the sake of their sound. And in fact my first completed novel, Burmese Days , which I wrote when I was thirty but projected much earlier, is rather that kind of book.

I give all this background information because I do not think one can assess a writer’s motives without knowing something of his early development. His subject-matter will be determined by the age he lives in – at least this is true in tumultuous, revolutionary ages like our own – but before he ever begins to write he will have acquired an emotional attitude from which he will never completely escape. It is his job, no doubt, to discipline his temperament and avoid getting stuck at some immature stage, or in some perverse mood: but if he escapes from his early influences altogether, he will have killed his impulse to write. Putting aside the need to earn a living, I think there are four great motives for writing, at any rate for writing prose. They exist in different degrees in every writer, and in any one writer the proportions will vary from time to time, according to the atmosphere in which he is living. They are:

(i) Sheer egoism. Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc., etc. It is humbug to pretend this is not a motive, and a strong one. Writers share this characteristic with scientists, artists, politicians, lawyers, soldiers, successful business men – in short, with the whole top crust of humanity. The great mass of human beings are not acutely selfish. After the age of about thirty they abandon individual ambition – in many cases, indeed, they almost abandon the sense of being individuals at all – and live chiefly for others, or are simply smothered under drudgery. But there is also the minority of gifted, willful people who are determined to live their own lives to the end, and writers belong in this class. Serious writers, I should say, are on the whole more vain and self-centered than journalists, though less interested in money.

(ii) Aesthetic enthusiasm. Perception of beauty in the external world, or, on the other hand, in words and their right arrangement. Pleasure in the impact of one sound on another, in the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story. Desire to share an experience which one feels is valuable and ought not to be missed. The aesthetic motive is very feeble in a lot of writers, but even a pamphleteer or writer of textbooks will have pet words and phrases which appeal to him for non-utilitarian reasons; or he may feel strongly about typography, width of margins, etc. Above the level of a railway guide, no book is quite free from aesthetic considerations.

(iii) Historical impulse. Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity.

(iv) Political purpose – using the word ‘political’ in the widest possible sense. Desire to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other people’s idea of the kind of society that they should strive after. Once again, no book is genuinely free from political bias. The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.

It can be seen how these various impulses must war against one another, and how they must fluctuate from person to person and from time to time. By nature – taking your ‘nature’ to be the state you have attained when you are first adult – I am a person in whom the first three motives would outweigh the fourth. In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer. First I spent five years in an unsuitable profession (the Indian Imperial Police, in Burma), and then I underwent poverty and the sense of failure. This increased my natural hatred of authority and made me for the first time fully aware of the existence of the working classes, and the job in Burma had given me some understanding of the nature of imperialism: but these experiences were not enough to give me an accurate political orientation. Then came Hitler, the Spanish Civil War, etc. By the end of 1935 I had still failed to reach a firm decision. I remember a little poem that I wrote at that date, expressing my dilemma:

A happy vicar I might have been Two hundred years ago, To preach upon eternal doom And watch my walnuts grow But born, alas, in an evil time, I missed that pleasant haven, For the hair has grown on my upper lip And the clergy are all clean-shaven. And later still the times were good, We were so easy to please, We rocked our troubled thoughts to sleep On the bosoms of the trees. All ignorant we dared to own The joys we now dissemble; The greenfinch on the apple bough Could make my enemies tremble. But girls’ bellies and apricots, Roach in a shaded stream, Horses, ducks in flight at dawn, All these are a dream. It is forbidden to dream again; We maim our joys or hide them; Horses are made of chromium steel And little fat men shall ride them. I am the worm who never turned, The eunuch without a harem; Between the priest and the commissar I walk like Eugene Aram; And the commissar is telling my fortune While the radio plays, But the priest has promised an Austin Seven, For Duggie always pays. I dreamt I dwelt in marble halls, And woke to find it true; I wasn’t born for an age like this; Was Smith? Was Jones? Were you?

The Spanish war and other events in 1936-37 turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it. It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects. Everyone writes of them in one guise or another. It is simply a question of which side one takes and what approach one follows. And the more one is conscious of one’s political bias, the more chance one has of acting politically without sacrificing one’s aesthetic and intellectual integrity.

What I have most wanted to do throughout the past ten years is to make political writing into an art. My starting point is always a feeling of partisanship, a sense of injustice. When I sit down to write a book, I do not say to myself, ‘I am going to produce a work of art’. I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing. But I could not do the work of writing a book, or even a long magazine article, if it were not also an aesthetic experience. Anyone who cares to examine my work will see that even when it is downright propaganda it contains much that a full-time politician would consider irrelevant. I am not able, and do not want, completely to abandon the world view that I acquired in childhood. So long as I remain alive and well I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style, to love the surface of the earth, and to take a pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information. It is no use trying to suppress that side of myself. The job is to reconcile my ingrained likes and dislikes with the essentially public, non-individual activities that this age forces on all of us.

It is not easy. It raises problems of construction and of language, and it raises in a new way the problem of truthfulness. Let me give just one example of the cruder kind of difficulty that arises. My book about the Spanish civil war, Homage to Catalonia , is of course a frankly political book, but in the main it is written with a certain detachment and regard for form. I did try very hard in it to tell the whole truth without violating my literary instincts. But among other things it contains a long chapter, full of newspaper quotations and the like, defending the Trotskyists who were accused of plotting with Franco. Clearly such a chapter, which after a year or two would lose its interest for any ordinary reader, must ruin the book. A critic whom I respect read me a lecture about it. ‘Why did you put in all that stuff?’ he said. ‘You’ve turned what might have been a good book into journalism.’ What he said was true, but I could not have done otherwise. I happened to know, what very few people in England had been allowed to know, that innocent men were being falsely accused. If I had not been angry about that I should never have written the book.

In one form or another this problem comes up again. The problem of language is subtler and would take too long to discuss. I will only say that of late years I have tried to write less picturesquely and more exactly. In any case I find that by the time you have perfected any style of writing, you have always outgrown it. Animal Farm was the first book in which I tried, with full consciousness of what I was doing, to fuse political purpose and artistic purpose into one whole. I have not written a novel for seven years, but I hope to write another fairly soon. It is bound to be a failure, every book is a failure, but I do know with some clarity what kind of book I want to write.

Looking back through the last page or two, I see that I have made it appear as though my motives in writing were wholly public-spirited. I don’t want to leave that as the final impression. All writers are vain, selfish, and lazy, and at the very bottom of their motives there lies a mystery. Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist or understand. For all one knows that demon is simply the same instinct that makes a baby squall for attention. And yet it is also true that one can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one’s own personality. Good prose is like a windowpane. I cannot say with certainty which of my motives are the strongest, but I know which of them deserve to be followed. And looking back through my work, I see that it is invariably where I lacked a political purpose that I wrote lifeless books and was betrayed into purple passages, sentences without meaning, decorative adjectives and humbug generally.

Gangrel , No. 4, Summer 1946

- Become a Friend

- Become an International Friend

- Becoming a Patron

We use cookies. By browsing our site you agree to our use of cookies. Accept

- Ethics & Leadership

- Fact-Checking

- Media Literacy

- The Craig Newmark Center

- Reporting & Editing

- Ethics & Trust

- Tech & Tools

- Business & Work

- Educators & Students

- Training Catalog

- Custom Teaching

- For ACES Members

- All Categories

- Broadcast & Visual Journalism

- Fact-Checking & Media Literacy

- In-newsroom

- Memphis, Tenn.

- Minneapolis, Minn.

- St. Petersburg, Fla.

- Washington, D.C.

- Poynter ACES Introductory Certificate in Editing

- Poynter ACES Intermediate Certificate in Editing

- Ethics & Trust Articles

- Get Ethics Advice

- Fact-Checking Articles

- International Fact-Checking Day

- Teen Fact-Checking Network

- International

- Media Literacy Training

- MediaWise Resources

- Ambassadors

- MediaWise in the News

Support responsible news and fact-based information today!

How politicians abuse language to magnify fear and reflect grievances

Orwell, trump, and the zombie apocalypse: an essay about diss, dys, and dat.

An essay by George Orwell, “Politics and the English Language,” changed the trajectory of my career. I pivoted from a job as a college literature teacher to become a writing coach for students, journalists and other public writers.

“Political language,” wrote Orwell, “is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.”

The author of the dystopian novels “Animal Farm” and “1984” posited this vicious yin-yang: that political corruption requires language abuse; and that abuse of language enables political corruption.

Orwell found evidence of language abuse at the heart of the most oppressive political systems: from fascism to communism, from British imperialism to heartless capitalism.

Rereading his essays on language, I wondered what the author of “1984” might think of the political language of 2024, especially the rhetoric of one Donald Trump.

Euphemism and dysphemism

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, Orwell argued that tyrants made murder sound respectable by their use of euphemisms and other forms of cloudy language. Euphemisms are language veils that can be thrown over any reality you don’t want people to see. Edward R. Murrow described what he saw in the concentration camps in vivid language. Nazi propagandists called it the “ultimate solution” to the “Jewish problem.”

When someone dies, and we explain that they “passed away,” or, in religious terms, “transitioned,” we are using euphemisms in harmless, even beneficial ways. When we revert to slang phrases such as “kick the bucket,” or “push up daisies,” or “food for worms,” we are at the other end of the spectrum. At some point in the last century, undertakers became morticians became the caretakers of funeral homes.

Political battles are often fought with verbal weapons such as euphemism vs. dysphemism. The argument over those rare abortions that occur late in pregnancy depends, in part, on whether you refer to the procedure as the soft jargon “intact dilation and extraction” or as the visceral “partial-birth abortion.” Think of the difference between “illegal aliens,” which sounds like an invasion of Martians, and “undocumented workers,” which sounds like a clerical error.

Orwell offers evidence of the power of euphemism to blind us to what is really happening:

Defenseless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called pacification . Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry: this is called transfer of population or rectification of frontiers .

His examples go on and on.

Orwell’s discourse makes me wonder if he would be surprised or even puzzled by the political rhetoric of Donald Trump and its influence on his followers. The former president — perhaps the once and future president — is no euphemist, and would scoff at the pointy-headed term. He is the dysphemist-in-chief, a speaker and writer who does not want to hide things from sight, but who wants you to see things that are not really there.

Language of Trump

There is no need for a full recitation of Trump’s statements and overstatements, especially when the topic is immigration or crime.

Immigrants, he insists, are “poisoning the blood of our country,” a familiar Nazi trope. Those crossing our borders are a horde of drug dealers, gang members, murderers and rapists. Some of them are coming from “shithole countries.” His political opponents are “vermin.” Crime in Chicago amounts to “carnage.”

Even when he was imagining the possible collapse of the auto industry, he could not avoid the dysphemism that it would mean a “blood bath” for the country.

An old propaganda tool is to dehumanize the enemy, which explains this description of some immigrants: “I don’t know if you call them people. In some cases, they’re not people. But I’m not allowed to say that because the radical left says that’s a terrible thing to say.”

Here’s his promise: “Among my very first actions upon taking office will be to stop the invasion of our country.” Invasion is a strong word, a scary word, so scary that when American troops have invaded countries, such as Vietnam, the generals and politicians preferred the Orwellian euphemism “incursion.”

Zombie apocalypse

Words such as euphemism and dysphemism can be used to describe the language of political discourse. More important, that language creates stories; narratives that can be used to spread hate or to support the common good.

When I read descriptions of immigrants as aliens or invading hordes, I am reminded of perhaps the most popular form of horror entertainment over the last quarter century: the narrative of the zombie apocalypse.

You must have seen at least one of the cinematic versions by now. Some outside force or infection or radiation turns ordinary people into monsters. Not just ordinary monsters, but flesh-eating ones. If they scratch or bite you, they pollute your blood so that you too turn into a zombie. The only way to stop them is to burn them, decapitate them, or shoot them in what is left of their brains. There are delightful variations, but that is the crux.

In the old days, zombies shambled. The more recent living dead can move quickly and in hordes.

Look, we’ve suffered through a pandemic, countless mass shootings, terrible problems on the southern border, race hatred and other forms of intolerance. No wonder the stories we tell, even for entertainment, are dystopian.

The word dystopia is the opposite of utopia. Plato wrote “The Republic,” Thomas More wrote “Utopia,” both narratives of ideal places. I have been more influenced and entertained by dystopian fiction: “Brave New World,” “1984,” “A Clockwork Orange,” just to name the ones I read in my youth.

In the cinema, Godzilla, a monster created by radiation, appeared in the aftermath of the atomic bombings of Japan. In the 1950s, during the anticommunist witch hunts, we were introduced to body snatchers who looked like us. More recently, gorgeous androgynous vampires multiplied just as Americans became more tolerant of gender differences.

I have no record of Donald Trump including “zombie” in his lexicon of insults, but there can be little doubt that his language and storytelling are meant to reflect the fears and grievances of his followers, fears that they are being invaded by creatures who are not quite human.

Voice of the people

It would be comical to argue that Trump has the eloquence of presidents such as Abraham Lincoln, Ronald Reagan or Barack Obama. Joe Biden has his own verbal issues, but Trump has something distinctive in his rhetorical style that has inspired an army of followers. We can begin by calling it a populist style, speaking and tweeting insults, slogans and catchphrases more associated with the feuds of professional wrestlers than the discourse of common politicians.

Orwell might have used Trump-speak as an example in his essay “Propaganda and Demotic Speech.” The word “demotic” is fancy talk that I had to look up: “Of or relating to the common people.” It shares the same root as “democracy” and derives from the Greek word for “people.”

As a world war became more inevitable in the early 1940s, Orwell noted that to defeat fascism the British people would have to make significant sacrifices. Life would change in countless undesirable ways. Who could persuade them to make the effort? Not the aristocrats, he argued. Not the high-toned speakers on the BBC. Not politicians with fancy educations. Their voices might only alienate people already feeling oppressed by rigid class distinctions. Persuasion could only come from those who spoke in the voice of the people.

Those who defend Trump’s language say things like “he tells it like it is” or “he says what he means” or “he speaks in plain English.” Others argue that we should “take Trump seriously, but not literally.” Or, “I don’t judge him by what he says. I judge him by what he does.”

I think I am pretty good with words. I can go high or low. I am a Philistine with a Ph.D. That means, if I were running for office, I could lie to you in the voice of a super scholar or the voice of the barely literate. I have wondered whether the language of Trump’s messages, filled with “mistakes” in grammar and usage, were so intended, to attract an audience already cynical about “elites” and their phony talk.

In 1976, I met the segregationist governor of Alabama, George Wallace, who made fun of people going up to the statehouse holding briefcases. The only thing in them, he argued, were “baloney sandwiches.” He described political speech as “getting the hay down where the goats can eat it.”

Even if we understand how certain politicians are abusing language, we are left with a problem: how to diss the effects of Trump’s dysphemistic language and dystopian narratives without having to resort to those fancy “dys” words in an essay such as “dys” one.

Roy Peter Clark is the author of “ Tell It Like It Is: A Guide to Clear and Honest Writing ,” now available in a paperback edition.

Opinion | Wall Street Journal marks one year of reporter’s detainment in Russian jail

Evan Gershkovich was arrested a year ago today in Russia while on a reporting assignment for the Journal

A Baltimore bridge collapsed in the middle of the night and two metro newsrooms leapt into action

Coverage from The Baltimore Sun and The Baltimore Banner had much in common but with some marked differences — especially in visuals.

Private equity reporting grants show good return

Projects in Hawaii, Milwaukee and south central Indiana knit news organizations into community life

Opinion | How misinformation will be gender-based in Ghana’s upcoming elections

Fact-checkers must be on the lookout for narratives that target and diminish women candidates

Opinion | The bombing of Erbil is a case study in misinformation

Real events spawn online fabrications, making data analysis an important tool for truth

You must be logged in to post a comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Start your day informed and inspired.

Get the Poynter newsletter that's right for you.

Description de l’éditeur

"Essays" by George Orwell is a compelling anthology that encapsulates the profound observations and critical reflections of one of the 20th century's most influential writers. Known for his keen intellect and incisive prose, Orwell tackles a wide array of subjects with insight and wit. From political commentary to social critique, his essays offer a timeless exploration of human nature and societal dynamics. Orwell's distinctive voice shines through as he dissects the complexities of power, language, and truth. Whether delving into the impact of propaganda or examining the nuances of literature, Orwell's essays resonate with relevance, providing readers with a thoughtful lens through which to view the world. This collection serves as both a testament to Orwell's enduring literary legacy and a thought-provoking examination of the issues that continue to shape our societies.

Plus de livres par George Orwell

- Literature & Fiction

- History & Criticism

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $17.32 $17.32 FREE delivery: Saturday, April 6 on orders over $35.00 shipped by Amazon. Ships from: Amazon Sold by: TheWorldShopUSA

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Buy used: $15.84

Other sellers on amazon.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Selected Essays (Oxford World's Classics) 1st Edition

Purchase options and add-ons.

- ISBN-10 0198804172

- ISBN-13 978-0198804178

- Edition 1st

- Publisher Oxford University Press

- Publication date March 1, 2021

- Language English

- Dimensions 5.08 x 0.75 x 7.68 inches

- Print length 368 pages

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may deliver to you quickly

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Oxford University Press; 1st edition (March 1, 2021)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 368 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0198804172

- ISBN-13 : 978-0198804178

- Item Weight : 2.31 pounds

- Dimensions : 5.08 x 0.75 x 7.68 inches

- #612 in British & Irish Literature

- #2,050 in Essays (Books)

- #14,744 in Classic Literature & Fiction

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

Top reviews from other countries.

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Advertisement

Use Your Allusion: See How Many Literary References You Recognize

By J. D. Biersdorfer March 28, 2024

- Share full article

Lines from poems and plays frequently serve as inspiration for later literary allusions. This 12-question quiz is crafted from a running list created by the Book Review’s staff to test your knowledge on a wide variety of referenced works. The source material spans thousands of years and includes ancient Greek history and modern pop songs.

The quiz is in the multiple-choice format, so just tap or click your answers. After you finish, you’ll get your score and a list of links to the original works. (And yes, the headline above does allude to a pair of 1991 albums from the rock band Guns N’ Roses. Give yourself extra credit if you spotted it.)

Video illustration by Erik Carter

Over the years, “I Sing the Body Electric” has been used repeatedly, including as the title for a Ray Bradbury short story (and his “Twilight Zone” script), as a musical anthem to creativity in the 1980 film “Fame” and in the lyrics of a 2012 Lana Del Rey song. But who said it first?

Benjamin Franklin

Mary Shelley

Walt Whitman

Paule Marshall

Chinua Achebe’s 1958 novel “Things Fall Apart,” Joan Didion’s 1968 essay collection “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” and Robert B. Parker’s 1983 thriller “The Widening Gyre” all take their titles from the same poem. What is the original poem — and who is its author?

“The Second Coming,” by William Butler Yeats

“The Road Not Taken,” by Robert Frost

“‘Hope’ Is the Thing With Feathers,” by Emily Dickinson

“The Charge of the Light Brigade,” by Alfred Tennyson

“Band of Brothers,” the 2001 World War II television drama, is based on a 1992 book by Stephen E. Ambrose. But which previous work used the phrase “band of brothers” quite notably?

“All Quiet on the Western Front,” by Erich Maria Remarque

“Henry V,” by William Shakespeare

“Richard III,” by William Shakespeare

“The Red Badge of Courage,” by Stephen Crane

Wait! “Band of Brothers” was decades ago and I just finished watching the new “Masters of the Air” series. Is that show’s title an allusion as well? If so, quiz me!

George Orwell

Winston S. Churchill

John Maynard Keynes

Moving on from land and air to water now: The title of “The Sea, the Sea,” Iris Murdoch’s 1978 novel, is also a famous line (“Θάλαττα! θάλαττα!” in the original language) shouted by Greek warriors when they reached the top of a mountain and could see a nearby body of water. What is the name of the Greek work?

“Odyssey,” by Homer

“Lysistrata,” by Aristophanes

“The Persians,” by Aeschylus

“Anabasis,” by Xenophon

Which 1951 poem by Langston Hughes gave the playwright Lorraine Hansberry the title for her 1959 stage play, “A Raisin in the Sun”?

“Let America Be America Again”

“The Weary Blues”

OK, back to Shakespeare, because that guy had a serious literary output that is still influential centuries later: Which one of the following books does NOT take its title from “Macbeth”?

“The Sound and the Fury,” by William Faulkner

“Let It Come Down,” by Paul Bowles

“For Whom the Bell Tolls,” by Ernest Hemingway

“Something Wicked This Way Comes,” by Ray Bradbury

“The Moon Is Down,” by John Steinbeck

The last line of Paul Laurence Dunbar’s 1899 poem “Sympathy” gave Maya Angelou the title for her first autobiography in 1969. What is that title?

“Little Brown Baby”

“Invitation to Love”

“I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings”

Elif Batuman has named both a novel and a nonfiction book after works by a certain 19th-century Russian author who wrote, among other things, “The Brothers Karamazov.” Who is this writer?

Alexander Pushkin

Leo Tolstoy

Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Nikolai Gogol

Which novelist is renowned for his allusions to popular music and literature in his work — and named his 1987 novel after a Beatles song on the band’s 1965 “Rubber Soul” album?

Bret Easton Ellis

Haruki Murakami

Paul Beatty

Hanif Kureishi

In the epigraph of his 2015 book, “Between the World and Me,” Ta-Nehisi Coates quotes a passage of a poem with the same title that influenced him. Who wrote that poem?

Gwendolyn Brooks

James Baldwin

Toni Morrison

Richard Wright

Which Scotsman’s work inspired the titles of John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men” and J.D. Salinger’s “The Catcher in the Rye”?

Sir Walter Scott

Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Burns

James Boswell

Iowa Poll: Half say new law requiring schools to ban books depicting sex acts goes too far

The des moines register has documented about 1,820 books — including 615 unique titles — removed from iowa schools since the law went into effect july 1..

© Copyright 2024, Des Moines Register and Tribune Co.

Half of Iowans believe the state’s new book ban law — which has resulted in the removal of more than a thousand books from public schools — goes too far, a new Des Moines Register/Mediacom Iowa Poll finds, while a third view the law and subsequent removals as “about right.”

Thirteen percent believe “this does not go far enough,” and 3% aren’t sure.

In May 2023, Gov. Kim Reynolds signed Senate File 496 , a sweeping education law that bans nearly all books depicting sex acts from public schools, among other changes. The law exempts religious books.

The Iowa Poll asked respondents to give their opinion on “Iowa’s new law requiring schools to ban books depicting sex acts,” which “has resulted in the removal of more than 1,300 books from Iowa public schools.”

The Des Moines Register documented more than 1,300 book removals from public schools due to the law by mid-February, when the poll question was written.

The Register is now aware of about 1,820 books — 615 of which are unique titles — removed from schools since the law went into effect July 1.

A federal judge has since blocked the state from enforcing the book ban as two lawsuits work their way through the courts

The poll of 804 Iowa adults was conducted by Selzer & Co. Feb. 25-28 and has a margin of error of plus or minus 3.5 percentage points.

Michelle Leaverton, of Urbandale, a poll respondent who agreed to a follow-up interview, described banning books as “absurd.”

The 51-year-old Democrat said depriving children of the ability to make choices about what they read and of perspectives they may see reflected in their own lives is damaging — including for her own children who identify as LGBTQ.

Leaverton said she is shocked by the lists of classic novels that have been removed from schools, such as “1984” and “Animal Farm” by George Orwell, and feels the law is further marginalizing LGBTQ and other underrepresented voices

Iowans with children under the age of 18 show more support for the law and book removals: 39% say this goes too far, 40% say this is about right, and 16% say this does not go far enough. Five percent of parents with children are not sure.

Independent voter Tracy Alberts of Cedar Rapids, 45, a poll respondent who agreed to a follow-up interview, feels the ban does not go far enough.

“I think parents should be put in charge of what is in the school's library and what is applicable for the grade level,” said the mother of three.

Outside of history, schools should allow books only on topics that a person can safely discuss in an office— meaning sexual content and politics do not have a place in schools, said Alberts, who works in human resources.

Views on book ban, removals divide by political party, gender

A large majority of Democrats (75%) and most independents (55%) view the book ban and removals as going too far. The plurality of Republicans (44%) see this situation as about right. Almost a quarter of Republicans (23%) say this does not go far enough.

The poll also shows a large gap by gender: 60% of women feel the law and book removals have gone too far, while 41% of men feel that way.

Republican Steven Davies of Corning, 54, feels the ban is about right for his family, but he has mixed emotions about outright banning of books for other students.

“Do I think that certain books in school shouldn't be in there?” Davies said. “Absolutely.”

He believes literature that’s sexual in nature should not be in schools and pointed to the LGBTQ memoir “Gender Queer” by Maia Kobabe. Iowa Republican lawmakers have targeted the visual novel, which traces the author’s journey with gender and sexuality through adolescence and adulthood, for its candid sexual images and scenes.

“I also acknowledge it is a slippery slope, because where does it end?” Davies said. “And who’s going to be the judge and jury of what gets banned?”

Iowa’s book ban law follows high-profile challenges over sexual content

High-profile attempts to restrict or remove books from schools popped up in the Des Moines metro and around the country in recent years as some residents challenged books that they felt were inappropriate for students. The divisive issue turned politically potent, and Iowa legislators took notice .

The Des Moines Register documented 99 challenges to 60 books from August 2020 to May 2023, before Reynolds signed the book ban law. Nearly 90 percent of Iowa school districts had no challenges in that time frame.

About three-quarters of challenges ended with retaining the book without restrictions.

About 76% of challenges that gave specific reasons were due to books’ sexual content, while about 26% cited profanity and 14% involved violence. (More than one reason was sometimes cited.)

The most-challenged books before the book ban passed were LGBTQ coming-of-age memoirs “Gender Queer” by Maia Kobabe and “All Boys Aren’t Blue” by George M. Johnson, alongside the semi-autobiographical novel “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian” by Sherman Alexie.

About 55% of challenges before the law passed were for books about people of color ; about 47% of challenges were for books featuring LGBTQ people; and about 25% of challenges were for books about people who survived sexual violence.

Conservative activists lobby for legislation; after passage, critics file lawsuits

Conservative activists, some with ties to the conservative parental rights group Moms for Liberty, took their case to the Iowa Legislature in 2023 and called the existing district-level book challenge process too difficult, subjective, biased and unresponsive to their concerns about books they felt were inappropriate for schools.

The new law, which took effect in July 2023, requires books in school libraries to be “age appropriate” and bans books depicting or describing sex acts. It also prohibits instruction or curriculum about gender identity and sexual orientation through sixth grade, which some school districts have interpreted to also include banning children's books with LGBTQ themes.

The results have been inconsistent : Some districts stripped dozens of books from shelves in their efforts to comply with the law, while others removed zero in the absence of guidance from the state Department of Education. Many districts have never disclosed to the Register which books they removed, if any.

The Register documented more than 1,300 books that were removed under the law by the time of this Iowa Poll, including controversial LGBTQ memoirs, popular young adult books, classic novels and nonfiction books about historical events.

The number includes some books that have since been restored. The three most-banned books have been “Nineteen Minutes” by Jodi Picoult, “Looking for Alaska” by John Green and “The Perks of Being a Wallflower” by Stephen Chbosky.

LGBTQ students and their families, authors whose books have been banned and advocacy groups filed two lawsuits against the state of Iowa over Senate File 496, saying the law is unconstitutional and amounts to censorship and discrimination against LGBTQ viewpoints.

Iowa’s book ban remains tied up in court

Judge Stephen Locher temporarily blocked the state from enforcing the book ban and disciplinary penalties for educators while the two lawsuits are pending in federal court. The decision did not require districts to restore the books they had removed.

Some districts have restored books — about 560 books in total, according to the Register’s tracking — while others have kept them off the shelves.

Supporters of Senate File 496 have said the law protects children from pornographic and age-inappropriate content and that books removed from schools are not “banned” because they’re still available in city libraries or bookstores and online.

Opponents have said book removals deprive students of enlightening stories about the diverse world around them while conflating literature with porn. They say librarians and parents should be trusted to decide what’s appropriate for students.

Chris Higgins covers the eastern and northern suburbs for the Register. Reach him at [email protected] or 515-423-5146 and follow him on Twitter @chris_higgins_ .

Samantha Hernandez covers education for the Register. Reach her at (515) 851-0982 or [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @svhernandez or Facebook at facebook.com/svhernandezreporter .

About the Iowa Poll

The Iowa Poll, conducted Feb. 25-28, 2024, for The Des Moines Register and Mediacom by Selzer & Co. of Des Moines, is based on telephone interviews with 804 Iowans ages 18 or older. Interviewers with Quantel Research contacted households with randomly selected landline and cell phone numbers supplied by Dynata. Interviews were administered in English. Responses were adjusted by age, sex and congressional district to reflect the general population based on recent American Community Survey estimates.

Questions based on the sample of 804 Iowa adults have a maximum margin of error of plus or minus 3.5 percentage points. This means that if this survey were repeated using the same questions and the same methodology, 19 times out of 20, the findings would not vary from the true population value by more than plus or minus 3.5 percentage points. Results based on smaller samples of respondents — such as by gender or age — have a larger margin of error.

Republishing the copyright Iowa Poll without credit and, on digital platforms, links to originating content on The Des Moines Register and Mediacom is prohibited.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A Collection of Essays Paperback - October 21, 1970. A Collection of Essays. Paperback - October 21, 1970. by George Orwell (Author) 4.6 438 ratings. See all formats and editions. A clear-eyed, uncompromising collection of essays from the "conscience of his generation" and the author of 1984 (V. S. Pritchett).

Reviews by Orwell. Anonymous Review of Burmese Interlude by C. V. Warren (The Listener, 1938) Anonymous Review of Trials in Burma by Maurice Collis (The Listener, 1938) Review of The Pub and the People by Mass-Observation (The Listener, 1943) Letters and other material. BBC Archive: George Orwell; Free will (a one act drama, written 1920)

George Orwell. 4.30. 7,746 ratings521 reviews. George Orwell's collected nonfiction, written in the clear-eyed and uncompromising style that earned him a critical following. One of the most thought-provoking and vivid essayists of the twentieth century, George Orwell fought the injustices of his time with singular vigor through pen and paper.

The Collected Essays, Journalism, and Letters of George Orwell "The nearest thing to Orwell's testament is sprawling rather than compact, the four-volume Collected Essays, Journalism, and Letters.Coedited by Ian Angus and Sonia Orwell, George Orwell's widow, it includes nearly all his nonfiction from 1920 to 1950….The set was first published fifty years ago and was reissued last year ...

A collection of essays by Orwell, George, 1903-1950. Publication date 1953 Topics Orwell, George, 1903-1950, English authors ... Language English. 316 pages ; 19 cm George Orwell's collected nonfiction, written in the clear-eyed and uncompromising style that earned him a critical following One of the most thought-provoking and vivid essayists ...

This is an enormous doorstop of a book, with over 1,300 pages of George Orwell's essays. Of course that doesn't cover everything he wrote, but it's an awful lot. While best known for his novels Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell was probably a better essayist than a novelist. This volume contains Orwell's best and most famous ...

George Orwell. HarperCollins, Oct 21, 1970 - Literary Criticism - 336 pages. In this bestselling compilation of essays, written in the clear-eyed, uncompromising language for which he is famous, Orwell discusses with vigor such diverse subjects as his boyhood schooling, the Spanish Civil War, Henry Miller, British imperialism, and the ...

George Orwell is most famous for his novels "1984" and "Animal Farm," but was a superb essayist as well. In this collection of essays from the 1930s and 1940s, Orwell holds forth on a wide range of topics. The reader learns much about the author's home country of England in this book. Orwell remembers his challenges as a child in an English ...

Included among the more than 240 essays in this volume are Orwell's famous discussion of pacifism, "My Country Right or Left"; his scathingly complicated views on the dirty work of imperialism in "Shooting an Elephant"; and his very firm opinion on how to make "A Nice Cup of Tea.". In his essays, Orwell elevated political writing ...

George Orwell's Essays illuminate the life and work of one of the greatest writers of this century - a man who elevated political writing to an art This outstanding collection brings together Orwell's longer, major essays and a fine selection of shorter pieces that includes 'My Country Right or Left', 'Decline of the English Murder', 'Shooting an Elephant' and 'A Hanging'.

Overview. A clear-eyed, uncompromising collection of essays from the "conscience of his generation" and the author of 1984 (V. S. Pritchett). One of the most thought-provoking and vivid essayists of the twentieth century, George Orwell fought the injustices of his time with singular vigor through pen and paper.

George Orwell's Essays illuminate the life and work of one of the greatest writers of this century - a man who elevated political writing to an art This outstanding collection brings together Orwell's longer, major essays and a fine selection of shorter pieces that includes 'My Country Right or Left', 'Decline of the English Murder', 'Shooting an Elephant' and 'A Hanging'.

Repro Books Limited, Sep 4, 2022 - Fiction - 246 pages. The collected nonfiction of George Orwell, written in the clear-eyed and uncompromising style that garnered him a devoted following. George Orwell, one of the most thought-provoking and vivid essayists of the twentieth century, used pen and paper to fight the injustices of his time.

9. ' Bookshop Memories '. As well as writing on politics and being a writer, Orwell also wrote perceptively about readers and book-buyers - as in this 1936 essay, published the same year as his novel Keep the Aspidistra Flying, which combined both bookshops and writers (the novel focuses on Gordon Comstock, an aspiring poet).

The articles collected in George Orwell's Essays illuminate the life and work of one of the most individual writers of this century - a man who elevated political writing to an art. This outstanding collection brings together Orwell's longer, major essays and a fine selection of shorter pieces that includes 'My Country Right or Left', 'Decline of the English Murder', 'Shooting an Elephant' and ...

Critical Essays. (Orwell) First edition (publ. Secker & Warburg) Critical Essays (1946) is a collection of wartime pieces by George Orwell. It covers a variety of topics in English literature, and also includes some pioneering studies of popular culture. It was acclaimed by critics, and Orwell himself thought it one of his most important books.

The bibliography of George Orwell includes journalism, essays, novels, and non-fiction books written by the British writer Eric Blair (1903-1950), either under his own name or, more usually, under his pen name George Orwell.Orwell was a prolific writer on topics related to contemporary English society and literary criticism, who has been declared "perhaps the 20th century's best chronicler ...

1 of 5 stars 2 of 5 stars 3 of 5 stars 4 of 5 stars 5 of 5 stars. George Orwell Omnibus: The Complete Novels: Animal Farm, Burmese Days, A Clergyman's Daughter, Coming up for Air, Keep the Aspidistra Flying, and Nineteen Eighty-Four. by. George Orwell. 4.41 avg rating — 1,214 ratings — published 1949 — 7 editions.

About the author (1954) George Orwell was born Eric Hugh Blair in 1903 in Motihari in Bengal, India and later studied at Eton for four years. Orwell was an assistant superintendent with the Indian Imperial Police in Burma. He left the position after five years and then moved to Paris, where he wrote his first two books, Burmese Days and Down ...

Mass Market Paperback. $8.88 14 Used from $5.00 1 New from $21.21 2 Collectible from $18.00. One of the most thought-provoking and vivid essayists of the twentieth century, George Orwell fought the injustices of his time with singular vigor through pen and paper. In this selection of essays, he ranges from reflections on his boyhood schooling ...

Why I Write. This material remains under copyright in some jurisdictions, including the US, and is reproduced here with the kind permission of the Orwell Estate.The Orwell Foundation is an independent charity - please consider making a donation or becoming a Friend of the Foundation to help us maintain these resources for readers everywhere.. From a very early age, perhaps the age of five or ...

An essay by George Orwell, "Politics and the English Language," changed the trajectory of my career. I pivoted from a job as a college literature teacher to become a writing coach for students ...

Téléchargez et lisez la version électronique du livre Essay écrit par George Orwell sur Apple Books. "Essays" by George Orwell is a compelling anthology that encapsulates the profou Romans et littérature · 2023. Quitter;

The Collected Essays, Journalism, and Letters of George Orwell. George Orwell. 4.7 out of 5 stars. 72. Paperback. 14 offers from $10.77. The George Orwell Complete Classic Essential Collection 6 Books Box Set (Keep the Aspidistra Flying, Clergyman's Daughter, Coming Up for Air, Burmese Days, Animal Farm & Nineteen Eighty-Four) George Orwell. 4. ...

Lines from poems and plays frequently serve as inspiration for later literary allusions. This 12-question quiz is crafted from a running list created by the Book Review's staff to test your ...

Twentieth century viewsFontana modern mastersGeorge Orwell: A Collection of Critical Essays, Raymond WilliamsSpectrum bookVolume 119 of Twentieth century views, ISSN0496-6058. The eleven essays included are arranged so that Orwell's works may be studied in the general order in which they were written.

Leaverton said she is shocked by the lists of classic novels that have been removed from schools, such as "1984" and "Animal Farm" by George Orwell, and feels the law is further ...