Revising an Argumentative Paper

Download this Handout PDF

Introduction

You’ve written a full draft of an argumentative paper. You’ve figured out what you’re generally saying and have put together one way to say it. But you’re not done. The best writing is revised writing, and you want to re–view, re–see, re–consider your argument to make sure that it’s as strong as possible. You’ll come back to smaller issues later (e.g., Is your language compelling? Are your paragraphs clearly and seamlessly connected? Are any of your sentences confusing?). But before you get into the details of phrases and punctuation, you need to focus on making sure your argument is as strong and persuasive as it can be. This page provides you with eight specific strategies for how to take on the important challenge of revising an argument.

- Give yourself time.

- Outline your argumentative claims and evidence.

- Analyze your argument’s assumptions.

- Revise with your audience in mind.

- Be your own most critical reader.

- Look for dissonance.

- Try “provocative revision.”

- Ask others to look critically at your argument.

1. Give yourself time.

The best way to begin re–seeing your argument is first to stop seeing it. Set your paper aside for a weekend, a day, or even a couple of hours. Of course, this will require you to have started your writing process well before your paper is due. But giving yourself this time allows you to refresh your perspective and separate yourself from your initial ideas and organization. When you return to your paper, try to approach your argument as a tough, critical reader. Reread it carefully. Maybe even read it out loud to hear it in a fresh way. Let the distance you created inform how you now see the paper differently.

2. Outline your argumentative claims and evidence.

This strategy combines the structure of a reverse outline with elements of argument that philosopher Stephen Toulmin detailed in his influential book The Uses of Argument . As you’re rereading your work, have a blank piece of paper or a new document next to you and write out:

- Your main claim (your thesis statement).

- Your sub–claims (the smaller claims that contribute to the larger claim).

- All the evidence you use to back up each of your claims.

Detailing these core elements of your argument helps you see its basic structure and assess whether or not your argument is convincing. This will also help you consider whether the most crucial elements of the argument are supported by the evidence and if they are logically sequenced to build upon each other.

In what follows we’ve provided a full example of what this kind of outline can look like. In this example, we’ve broken down the key argumentative claims and kinds of supporting evidence that Derek Thompson develops in his July/August 2015 Atlantic feature “ A World Without Work. ” This is a provocative and fascinating article, and we highly recommend it.

Charted Argumentative Claims and Evidence “ A World Without Work ” by Derek Thompson ( The Atlantic , July/August 2015) Main claim : Machines are making workers obsolete, and while this has the potential to disrupt and seriously damage American society, if handled strategically through governmental guidance, it also has the potential of helping us to live more communal, creative, and empathetic lives. Sub–claim : The disappearance of work would radically change the United States. Evidence: personal experience and observation Sub–claim : This is because work functions as something of an unofficial religion to Americans. Sub–claim : Technology has always guided the U.S. labor force. Evidence: historical examples Sub–claim: But now technology may be taking over our jobs. Sub–claim : However, the possibility that technology will take over our jobs isn’t anything new, nor is the fear that this possibility generates. Evidence: historical examples Sub–claim : So far, that fear hasn’t been justified, but it may now be because: 1. Businesses don’t require people to work like they used to. Evidence: statistics 2. More and more men and youths are unemployed. Evidence: statistics 3. Computer technology is advancing in majorly sophisticated ways. Evidence: historical examples and expert opinions Counter–argument: But technology has been radically advancing for 300 years and people aren’t out of work yet. Refutation: The same was once said about the horse. It was a key economic player; technology was built around it until technology began to surpass it. This parallels what will happen with retail workers, cashiers, food service employees, and office clerks. Evidence:: an academic study Counter–argument: But technology creates jobs too. Refutation: Yes, but not as quickly as it takes them away. Evidence: statistics Sub–claim : There are three overlapping visions of what the world might look like without work: 1. Consumption —People will not work and instead devote their freedom to leisure. Sub–claim : People don’t like their jobs. Evidence: polling data Sub–claim : But they need them. Evidence: expert insight Sub–claim : People might be happier if they didn’t have to work. Evidence: expert insight Counter–argument: But unemployed people don’t tend to be socially productive. Evidence: survey data Sub–claim : Americans feel guilty if they aren’t working. Evidence: statistics and academic studies Sub–claim : Future leisure activities may be nourishing enough to stave off this guilt. 2. Communal creativity —People will not work and will build productive, artistic, engaging communities outside the workplace. Sub–claim: This could be a good alternative to work. Evidence: personal experience and observation 3. Contingency —People will not work one big job like they used to and so will fight to regain their sense of productivity by piecing together small jobs. Evidence: personal experience and observation. Sub–claim : The internet facilitates gig work culture. Evidence: examples of internet-facilitated gig employment Sub–claim : No matter the form the labor force decline takes, it would require government support/intervention in regards to the issues of taxes and income distribution. Sub–claim : Productive things governments could do: • Local governments should create more and more ambitious community centers to respond to unemployment’s loneliness and its diminishment of community pride. • Government should create more small business incubators. Evidence: This worked in Youngstown. • Governments should encourage job sharing. Evidence: This worked for Germany. Counter–argument: Some jobs can’t be shared, and job sharing doesn’t fix the problem in the long term. Given this counter argument: • Governments should heavily tax the owners of capital and cut checks to all adults. Counter–argument: The capital owners would push against this, and this wouldn’t provide an alternative to the social function work plays. Refutation: Government should pay people to do something instead of nothing via an online job–posting board open up to governments, NGOs, and the like. • Governments should incentivize school by paying people to study. Sub–claim : There is a difference between jobs, careers, and calling, and a fulfilled life is lived in pursuit of a calling. Evidence: personal experience and observations

Some of the possible, revision-informing questions that this kind of outline can raise are:

- Are all the claims thoroughly supported by evidence?

- What kinds of evidence are used across the whole argument? Is the nature of the evidence appropriate given your context, purpose, and audience?

- How are the sub–claims related to each other? How do they build off of each other and work together to logically further the larger claim?

- Do any of your claims need to be qualified in order to be made more precise?

- Where and how are counter–arguments raised? Are they fully and fairly addressed?

For more information about the Toulmin Method, we recommend John Ramage, John Bean, and June Johnson’s book Written Arguments: A Rhetoric with Readings.

3. Analyze your argument’s assumptions.

In building arguments we make assumptions either explicitly or implicitly that connect our evidence to our claims. For example, in “A World Without Work,” as Thompson makes claims about the way technology will change the future of work, he is assuming that computer technology will keep advancing in major and surprising ways. This assumption helps him connect the evidence he provides about technology’s historical precedents to his claims about the future of work. Many of us would agree that it is reasonable to assume that technological advancement will continue, but it’s still important to recognize this as an assumption underlying his argument.

To identify your assumptions, return to the claims and evidence that you outlined in response to recommendation #2. Ask yourself, “What assumptions am I making about this piece of evidence in order to connect this evidence to this claim?” Write down those assumptions, and then ask yourself, “Are these assumptions reasonable? Are they acknowledged in my argument? If not, do they need to be?”

Often you will not overtly acknowledge your assumptions, and that can be fine. But especially if your readers don’t share certain beliefs, values, or knowledge, you can’t guarantee that they will just go along with the assumptions you make. In these situations, it can be valuable to clearly account for some of your assumptions within your paper and maybe even rationalize them by providing additional evidence. For example, if Thompson were writing his article for an audience skeptical that technology will continue advancing, he might choose to identify openly why he is convinced that humanity’s progression towards more complex innovation won’t stop.

4. Revise with your audience in mind.

We touched on this in the previous recommendation, but it’s important enough to expand on it further. Just as you should think about what your readers know, believe, and value as you consider the kinds of assumptions you make in your argument, you should also think about your audience in relationship to the kind of evidence you use. Given who will read your paper, what kind of argumentative support will they find to be the most persuasive? Are these readers who are compelled by numbers and data? Would they be interested by a personal narrative? Would they expect you to draw from certain key scholars in their field or avoid popular press sources or only look to scholarship that has been published in the past ten years? Return to your argument and think about how your readers might respond to it and its supporting evidence.

5. Be your own most critical reader.

Sometimes writing handbooks call this being the devil’s advocate. It is about intentionally pushing against your own ideas. Reread your draft while embracing a skeptical attitude. Ask questions like, “Is that really true?” and, “Where’s the proof?” Be as hard on your argument as you can be, and then let your criticisms inform what you need to expand on, clarify, and eliminate.

This kind of reading can also help you think about how you might incorporate or strengthen a counter–argument. By focusing on possible criticisms to your argument, you might encounter some that are particularly compelling that you’ll need to include in your paper. Sometimes the best way to revise with criticism in mind is to face that criticism head on, fairly explain what it is and why it’s important to consider, and then rationalize why your argument still holds even in light of this other perspective.

6. Look for dissonance.

In her influential 1980 article about how expert and novice writers revise differently, writing studies scholar Nancy Sommers claims that “at the heart of revision is the process by which writers recognize and resolve the dissonance they sense in their writing” (385). In this case, dissonance can be understood as the tension that exists between what you want your text to be, do, or sound like and what is actually on the page. One strategy for re–seeing your argument is to seek out the places where you feel dissonance within your argument—that is, substantive differences between what, in your mind, you want to be arguing, and what is actually in your draft.

A key to strengthening a paper through considering dissonance is to look critically—really critically—at your draft. Read through your paper with an eye towards content, assertions, or logical leaps that you feel uncertain about, that make you squirm a little bit, or that just don’t line up as nicely as you’d like. Some possible sources of dissonance might include:

- logical steps that are missing

- questions a skeptical reader might raise that are left unanswered

- examples that don’t actually connect to what you’re arguing

- pieces of evidence that contradict each other

- sources you read but aren’t mentioning because they disagree with you

Once you’ve identified dissonance within your paper, you have to decide what to do with it. Sometimes it’s tempting to take the easy way out and just delete the idea, claim, or section that is generating this sense of dissonance—to remove what seems to be causing the trouble. But don’t limit yourself to what is easy. Perhaps you need to add material or qualify something to make your argumentative claim more nuanced or more contextualized.

Even if the dissonance isn’t easily resolved, it’s still important to recognize. In fact, sometimes you can factor that recognition into how you revise; maybe your revision can involve considering how certain concepts or ideas don’t easily fit but are still important in some way. Maybe your revision can involve openly acknowledging and justifying the dissonance.

Sommers claims that whether expert writers are substituting, adding, deleting, or reordering material in response to dissonance, what they are really doing is locating and creating new meaning. Let your recognition of dissonance within your argument lead you through a process of discovery.

7. Try “provocative revision.”

Composition and writing center scholar Toby Fulwiler wrote in 1992 about the benefits of what he calls “provocative revision.” He says this kind of revision can take four forms. As you think about revising your argument, consider adopting one of these four strategies.

a. Limiting

As Fulwiler writes, “Generalization is death to good writing. Limiting is the cure for generality” (191). Generalization often takes the form of sweeping introduction statements (e.g., “Since the beginning of time, development has struggled against destruction.”), but arguments can be too general as well. Look back at your paper and ask yourself, “Is my argument ever not grounded in specifics? Is my evidence connected to a particular time, place, community, and circumstance?” If your claims are too broad, you may need to limit your scope and zoom in to the particular.

Inserting new content is a particularly common revision strategy. But when your focus is on revising an argument, make sure your addition of another source, another example, a more detailed description, or a closer analysis is in direct service to strengthening the argument. Adding material may be one way to respond to dissonance. It also can be useful for offering clarifications or for making previously implicit assumptions explicit. But adding isn’t just a matter of dropping new content into a paragraph. Adding something new in one place will probably influence other parts of the paper, so be prepared to make other additions to seamlessly weave together your new ideas.

c. Switching

For Fulwiler, switching is about radically altering the voice or tone of a text—changing from the first–person perspective to a third–person perspective or switching from an earnest appeal to a sarcastic critique. When it comes to revising your argument, it might not make sense to make any of these switches, but imaging what your argument might sound like coming from a very different voice might be generative. For example, how would Thompson’s “A World Without Work,” be altered if it was written from the voice and perspective of an unemployed steel mill worker or someone running for public office in Ohio or a mechanical robotics engineer? Re–visioning how your argument might come across if the primary voice, tone, and perspective was switched might help you think about how someone disinclined to agree with your ideas might approach your text and open additional avenues for revision.

d. Transforming

According to Fulwiler, transformation is about altering the genre and/or modality of a text—revising an expository essay into a letter to the editor, turning a persuasive research paper into a ballad. If you’re writing in response to a specific assignment, you may not have the chance to transform your argument in this way. But, as with switching, even reflecting on the possibilities of a genre or modality transformation can be useful in helping you think differently about your argument. If Thompson has been writing a commencement address instead of an article, how would “A World Without Work” need to change? How would he need to alter his focus and approach if it was a policy paper or a short documentary? Imagining your argument in a completely different context can help you to rethink how you are presenting your argument and engaging with your audience.

8. Ask others to look critically at your argument.

Sometimes the best thing you can do to figure out how your argument could improve is to get a second opinion. Of course, if you are a currently enrolled student at UW–Madison, you are welcome to make an appointment to talk with a tutor at our main center or stop by one of our satellite locations. But you have other ways to access quality feedback from other readers. You may want to ask someone else in your class, a roommate, or a friend to read through your paper with an eye towards how the argument could be improved. Be sure to provide your reader with specific questions to guide his or her attention towards specific parts of your argument (e.g., “How convincing do you find the connection I make between the claims on page 3 and the evidence on page 4?” “What would clarify further the causal relationship I’m suggesting between the first and second sub-argument?”). Be ready to listen graciously and critically to any recommendations these readers provide.

Works Cited

Fulwiler, Toby. “Provocative Revision.” Writing Center Journal, vol. 12, no. 2, 1992, pp. 190-204.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. Writing Arguments: A Rhetoric with Readings, 8th ed., Longman, 2010.

Sommers, Nancy. “Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 31, no. 4, 1980, pp. 378-88.

Thompson, Derek. “A World Without Work.” The Atlantic, July/August 2015, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/07/world-without-work/395294/. Accessed 11 July 2017.

Toulmin, Stephen. The Uses of Argument. Updated ed., Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Developing a Thesis Statement

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.4 Revising and Editing

Learning objectives.

- Identify major areas of concern in the draft essay during revising and editing.

- Use peer reviews and editing checklists to assist revising and editing.

- Revise and edit the first draft of your essay and produce a final draft.

Revising and editing are the two tasks you undertake to significantly improve your essay. Both are very important elements of the writing process. You may think that a completed first draft means little improvement is needed. However, even experienced writers need to improve their drafts and rely on peers during revising and editing. You may know that athletes miss catches, fumble balls, or overshoot goals. Dancers forget steps, turn too slowly, or miss beats. For both athletes and dancers, the more they practice, the stronger their performance will become. Web designers seek better images, a more clever design, or a more appealing background for their web pages. Writing has the same capacity to profit from improvement and revision.

Understanding the Purpose of Revising and Editing

Revising and editing allow you to examine two important aspects of your writing separately, so that you can give each task your undivided attention.

- When you revise , you take a second look at your ideas. You might add, cut, move, or change information in order to make your ideas clearer, more accurate, more interesting, or more convincing.

- When you edit , you take a second look at how you expressed your ideas. You add or change words. You fix any problems in grammar, punctuation, and sentence structure. You improve your writing style. You make your essay into a polished, mature piece of writing, the end product of your best efforts.

How do you get the best out of your revisions and editing? Here are some strategies that writers have developed to look at their first drafts from a fresh perspective. Try them over the course of this semester; then keep using the ones that bring results.

- Take a break. You are proud of what you wrote, but you might be too close to it to make changes. Set aside your writing for a few hours or even a day until you can look at it objectively.

- Ask someone you trust for feedback and constructive criticism.

- Pretend you are one of your readers. Are you satisfied or dissatisfied? Why?

- Use the resources that your college provides. Find out where your school’s writing lab is located and ask about the assistance they provide online and in person.

Many people hear the words critic , critical , and criticism and pick up only negative vibes that provoke feelings that make them blush, grumble, or shout. However, as a writer and a thinker, you need to learn to be critical of yourself in a positive way and have high expectations for your work. You also need to train your eye and trust your ability to fix what needs fixing. For this, you need to teach yourself where to look.

Creating Unity and Coherence

Following your outline closely offers you a reasonable guarantee that your writing will stay on purpose and not drift away from the controlling idea. However, when writers are rushed, are tired, or cannot find the right words, their writing may become less than they want it to be. Their writing may no longer be clear and concise, and they may be adding information that is not needed to develop the main idea.

When a piece of writing has unity , all the ideas in each paragraph and in the entire essay clearly belong and are arranged in an order that makes logical sense. When the writing has coherence , the ideas flow smoothly. The wording clearly indicates how one idea leads to another within a paragraph and from paragraph to paragraph.

Reading your writing aloud will often help you find problems with unity and coherence. Listen for the clarity and flow of your ideas. Identify places where you find yourself confused, and write a note to yourself about possible fixes.

Creating Unity

Sometimes writers get caught up in the moment and cannot resist a good digression. Even though you might enjoy such detours when you chat with friends, unplanned digressions usually harm a piece of writing.

Mariah stayed close to her outline when she drafted the three body paragraphs of her essay she tentatively titled “Digital Technology: The Newest and the Best at What Price?” But a recent shopping trip for an HDTV upset her enough that she digressed from the main topic of her third paragraph and included comments about the sales staff at the electronics store she visited. When she revised her essay, she deleted the off-topic sentences that affected the unity of the paragraph.

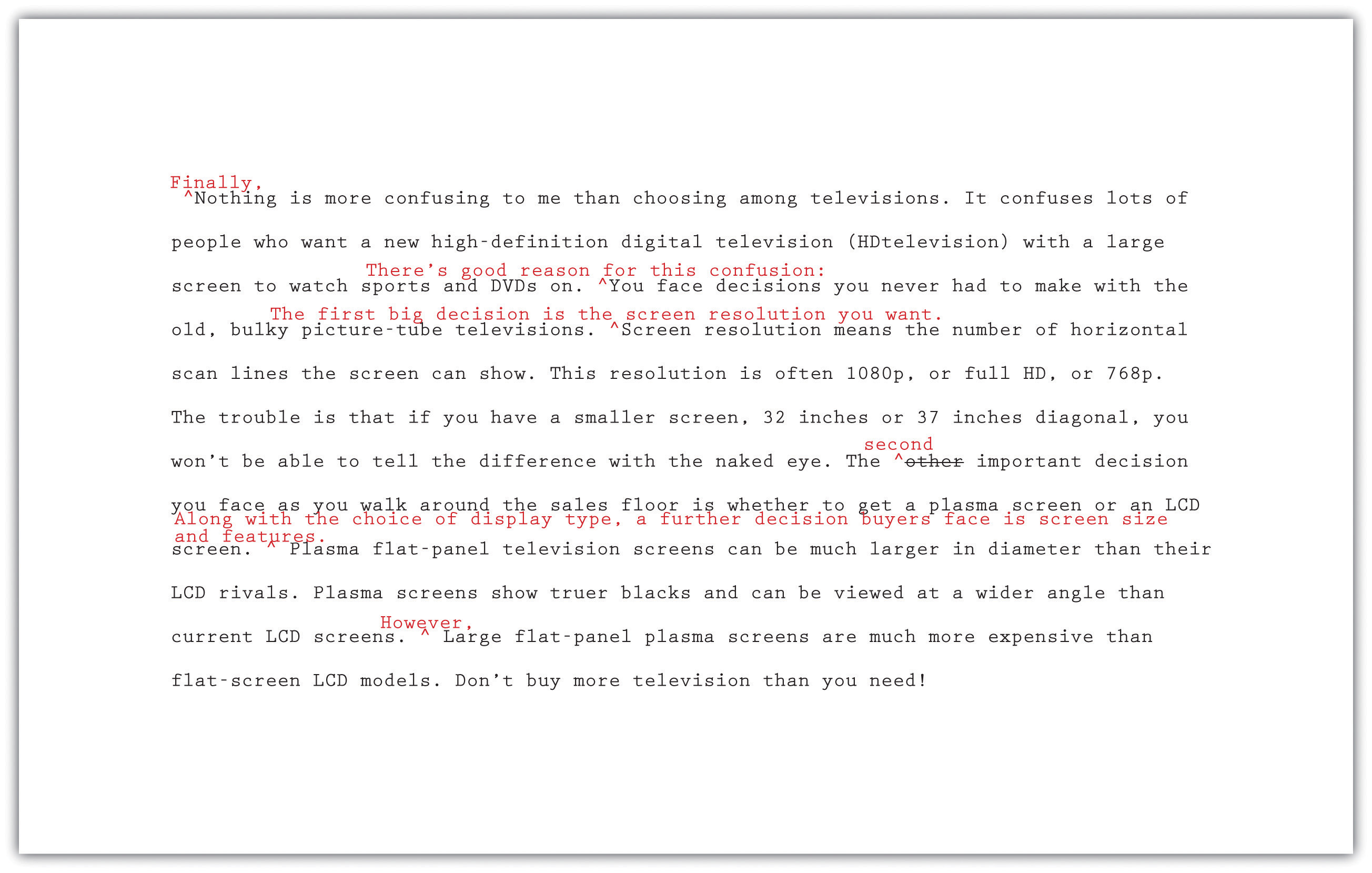

Read the following paragraph twice, the first time without Mariah’s changes, and the second time with them.

Nothing is more confusing to me than choosing among televisions. It confuses lots of people who want a new high-definition digital television (HDTV) with a large screen to watch sports and DVDs on. You could listen to the guys in the electronics store, but word has it they know little more than you do. They want to sell what they have in stock, not what best fits your needs. You face decisions you never had to make with the old, bulky picture-tube televisions. Screen resolution means the number of horizontal scan lines the screen can show. This resolution is often 1080p, or full HD, or 768p. The trouble is that if you have a smaller screen, 32 inches or 37 inches diagonal, you won’t be able to tell the difference with the naked eye. The 1080p televisions cost more, though, so those are what the salespeople want you to buy. They get bigger commissions. The other important decision you face as you walk around the sales floor is whether to get a plasma screen or an LCD screen. Now here the salespeople may finally give you decent info. Plasma flat-panel television screens can be much larger in diameter than their LCD rivals. Plasma screens show truer blacks and can be viewed at a wider angle than current LCD screens. But be careful and tell the salesperson you have budget constraints. Large flat-panel plasma screens are much more expensive than flat-screen LCD models. Don’t let someone make you by more television than you need!

Answer the following two questions about Mariah’s paragraph:

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

- Now start to revise the first draft of the essay you wrote in Section 8 “Writing Your Own First Draft” . Reread it to find any statements that affect the unity of your writing. Decide how best to revise.

When you reread your writing to find revisions to make, look for each type of problem in a separate sweep. Read it straight through once to locate any problems with unity. Read it straight through a second time to find problems with coherence. You may follow this same practice during many stages of the writing process.

Writing at Work

Many companies hire copyeditors and proofreaders to help them produce the cleanest possible final drafts of large writing projects. Copyeditors are responsible for suggesting revisions and style changes; proofreaders check documents for any errors in capitalization, spelling, and punctuation that have crept in. Many times, these tasks are done on a freelance basis, with one freelancer working for a variety of clients.

Creating Coherence

Careful writers use transitions to clarify how the ideas in their sentences and paragraphs are related. These words and phrases help the writing flow smoothly. Adding transitions is not the only way to improve coherence, but they are often useful and give a mature feel to your essays. Table 8.3 “Common Transitional Words and Phrases” groups many common transitions according to their purpose.

Table 8.3 Common Transitional Words and Phrases

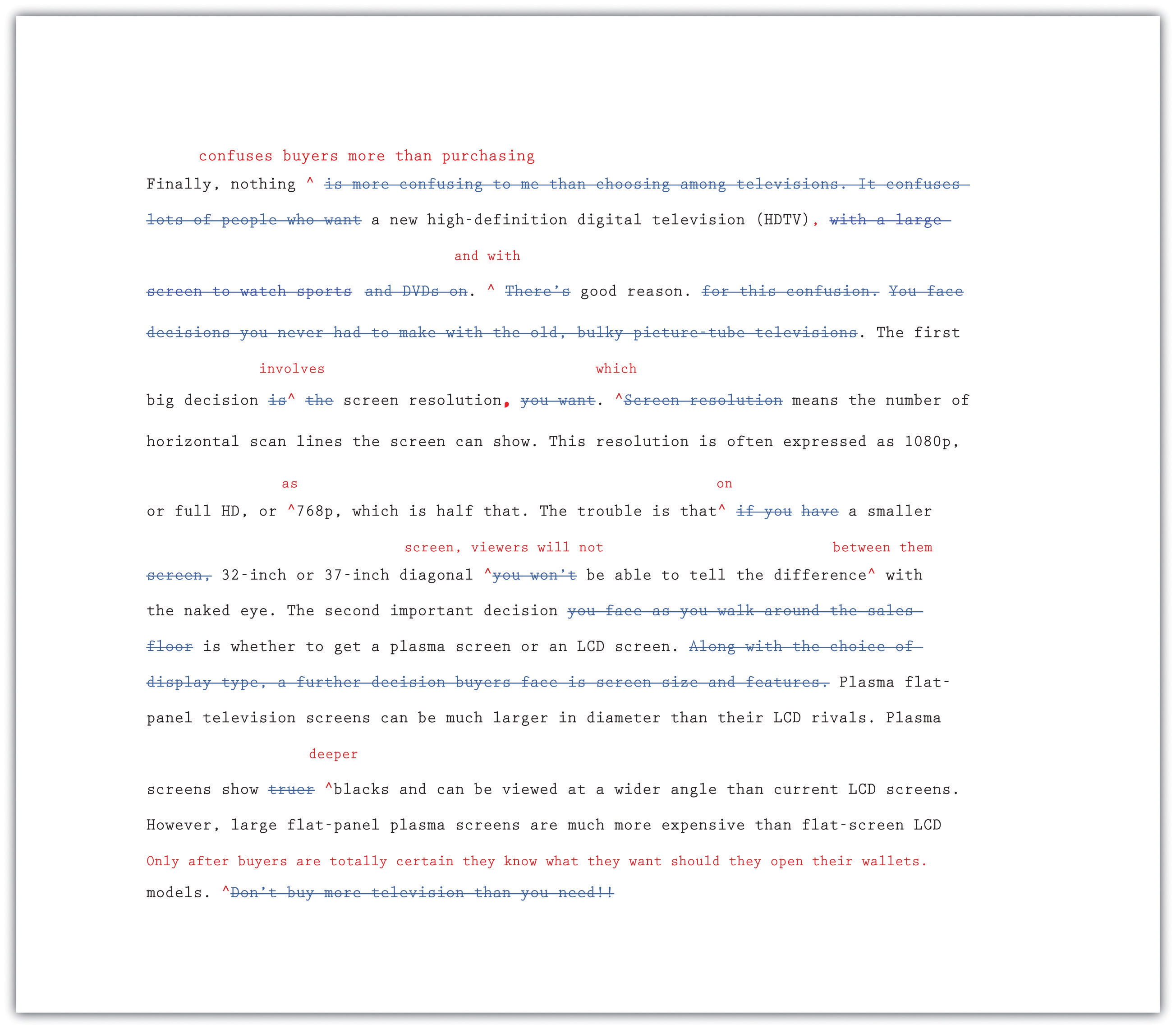

After Maria revised for unity, she next examined her paragraph about televisions to check for coherence. She looked for places where she needed to add a transition or perhaps reword the text to make the flow of ideas clear. In the version that follows, she has already deleted the sentences that were off topic.

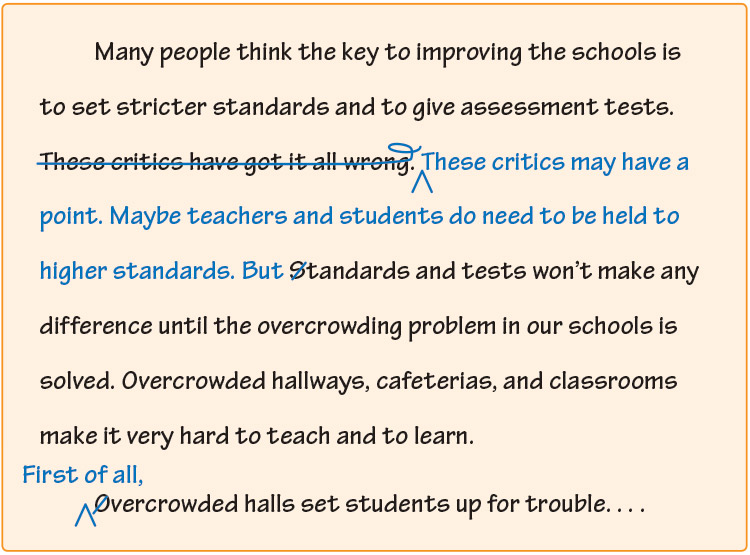

Many writers make their revisions on a printed copy and then transfer them to the version on-screen. They conventionally use a small arrow called a caret (^) to show where to insert an addition or correction.

1. Answer the following questions about Mariah’s revised paragraph.

2. Now return to the first draft of the essay you wrote in Section 8 “Writing Your Own First Draft” and revise it for coherence. Add transition words and phrases where they are needed, and make any other changes that are needed to improve the flow and connection between ideas.

Being Clear and Concise

Some writers are very methodical and painstaking when they write a first draft. Other writers unleash a lot of words in order to get out all that they feel they need to say. Do either of these composing styles match your style? Or is your composing style somewhere in between? No matter which description best fits you, the first draft of almost every piece of writing, no matter its author, can be made clearer and more concise.

If you have a tendency to write too much, you will need to look for unnecessary words. If you have a tendency to be vague or imprecise in your wording, you will need to find specific words to replace any overly general language.

Identifying Wordiness

Sometimes writers use too many words when fewer words will appeal more to their audience and better fit their purpose. Here are some common examples of wordiness to look for in your draft. Eliminating wordiness helps all readers, because it makes your ideas clear, direct, and straightforward.

Sentences that begin with There is or There are .

Wordy: There are two major experiments that the Biology Department sponsors.

Revised: The Biology Department sponsors two major experiments.

Sentences with unnecessary modifiers.

Wordy: Two extremely famous and well-known consumer advocates spoke eloquently in favor of the proposed important legislation.

Revised: Two well-known consumer advocates spoke in favor of the proposed legislation.

Sentences with deadwood phrases that add little to the meaning. Be judicious when you use phrases such as in terms of , with a mind to , on the subject of , as to whether or not , more or less , as far as…is concerned , and similar expressions. You can usually find a more straightforward way to state your point.

Wordy: As a world leader in the field of green technology, the company plans to focus its efforts in the area of geothermal energy.

A report as to whether or not to use geysers as an energy source is in the process of preparation.

Revised: As a world leader in green technology, the company plans to focus on geothermal energy.

A report about using geysers as an energy source is in preparation.

Sentences in the passive voice or with forms of the verb to be . Sentences with passive-voice verbs often create confusion, because the subject of the sentence does not perform an action. Sentences are clearer when the subject of the sentence performs the action and is followed by a strong verb. Use strong active-voice verbs in place of forms of to be , which can lead to wordiness. Avoid passive voice when you can.

Wordy: It might perhaps be said that using a GPS device is something that is a benefit to drivers who have a poor sense of direction.

Revised: Using a GPS device benefits drivers who have a poor sense of direction.

Sentences with constructions that can be shortened.

Wordy: The e-book reader, which is a recent invention, may become as commonplace as the cell phone.

My over-sixty uncle bought an e-book reader, and his wife bought an e-book reader, too.

Revised: The e-book reader, a recent invention, may become as commonplace as the cell phone.

My over-sixty uncle and his wife both bought e-book readers.

Now return once more to the first draft of the essay you have been revising. Check it for unnecessary words. Try making your sentences as concise as they can be.

Choosing Specific, Appropriate Words

Most college essays should be written in formal English suitable for an academic situation. Follow these principles to be sure that your word choice is appropriate. For more information about word choice, see Chapter 4 “Working with Words: Which Word Is Right?” .

- Avoid slang. Find alternatives to bummer , kewl , and rad .

- Avoid language that is overly casual. Write about “men and women” rather than “girls and guys” unless you are trying to create a specific effect. A formal tone calls for formal language.

- Avoid contractions. Use do not in place of don’t , I am in place of I’m , have not in place of haven’t , and so on. Contractions are considered casual speech.

- Avoid clichés. Overused expressions such as green with envy , face the music , better late than never , and similar expressions are empty of meaning and may not appeal to your audience.

- Be careful when you use words that sound alike but have different meanings. Some examples are allusion/illusion , complement/compliment , council/counsel , concurrent/consecutive , founder/flounder , and historic/historical . When in doubt, check a dictionary.

- Choose words with the connotations you want. Choosing a word for its connotations is as important in formal essay writing as it is in all kinds of writing. Compare the positive connotations of the word proud and the negative connotations of arrogant and conceited .

- Use specific words rather than overly general words. Find synonyms for thing , people , nice , good , bad , interesting , and other vague words. Or use specific details to make your exact meaning clear.

Now read the revisions Mariah made to make her third paragraph clearer and more concise. She has already incorporated the changes she made to improve unity and coherence.

1. Answer the following questions about Mariah’s revised paragraph:

2. Now return once more to your essay in progress. Read carefully for problems with word choice. Be sure that your draft is written in formal language and that your word choice is specific and appropriate.

Completing a Peer Review

After working so closely with a piece of writing, writers often need to step back and ask for a more objective reader. What writers most need is feedback from readers who can respond only to the words on the page. When they are ready, writers show their drafts to someone they respect and who can give an honest response about its strengths and weaknesses.

You, too, can ask a peer to read your draft when it is ready. After evaluating the feedback and assessing what is most helpful, the reader’s feedback will help you when you revise your draft. This process is called peer review .

You can work with a partner in your class and identify specific ways to strengthen each other’s essays. Although you may be uncomfortable sharing your writing at first, remember that each writer is working toward the same goal: a final draft that fits the audience and the purpose. Maintaining a positive attitude when providing feedback will put you and your partner at ease. The box that follows provides a useful framework for the peer review session.

Questions for Peer Review

Title of essay: ____________________________________________

Date: ____________________________________________

Writer’s name: ____________________________________________

Peer reviewer’s name: _________________________________________

- This essay is about____________________________________________.

- Your main points in this essay are____________________________________________.

- What I most liked about this essay is____________________________________________.

These three points struck me as your strongest:

These places in your essay are not clear to me:

a. Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because__________________________________________

b. Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because ____________________________________________

c. Where: ____________________________________________

The one additional change you could make that would improve this essay significantly is ____________________________________________.

One of the reasons why word-processing programs build in a reviewing feature is that workgroups have become a common feature in many businesses. Writing is often collaborative, and the members of a workgroup and their supervisors often critique group members’ work and offer feedback that will lead to a better final product.

Exchange essays with a classmate and complete a peer review of each other’s draft in progress. Remember to give positive feedback and to be courteous and polite in your responses. Focus on providing one positive comment and one question for more information to the author.

Using Feedback Objectively

The purpose of peer feedback is to receive constructive criticism of your essay. Your peer reviewer is your first real audience, and you have the opportunity to learn what confuses and delights a reader so that you can improve your work before sharing the final draft with a wider audience (or your intended audience).

It may not be necessary to incorporate every recommendation your peer reviewer makes. However, if you start to observe a pattern in the responses you receive from peer reviewers, you might want to take that feedback into consideration in future assignments. For example, if you read consistent comments about a need for more research, then you may want to consider including more research in future assignments.

Using Feedback from Multiple Sources

You might get feedback from more than one reader as you share different stages of your revised draft. In this situation, you may receive feedback from readers who do not understand the assignment or who lack your involvement with and enthusiasm for it.

You need to evaluate the responses you receive according to two important criteria:

- Determine if the feedback supports the purpose of the assignment.

- Determine if the suggested revisions are appropriate to the audience.

Then, using these standards, accept or reject revision feedback.

Work with two partners. Go back to Note 8.81 “Exercise 4” in this lesson and compare your responses to Activity A, about Mariah’s paragraph, with your partners’. Recall Mariah’s purpose for writing and her audience. Then, working individually, list where you agree and where you disagree about revision needs.

Editing Your Draft

If you have been incorporating each set of revisions as Mariah has, you have produced multiple drafts of your writing. So far, all your changes have been content changes. Perhaps with the help of peer feedback, you have made sure that you sufficiently supported your ideas. You have checked for problems with unity and coherence. You have examined your essay for word choice, revising to cut unnecessary words and to replace weak wording with specific and appropriate wording.

The next step after revising the content is editing. When you edit, you examine the surface features of your text. You examine your spelling, grammar, usage, and punctuation. You also make sure you use the proper format when creating your finished assignment.

Editing often takes time. Budgeting time into the writing process allows you to complete additional edits after revising. Editing and proofreading your writing helps you create a finished work that represents your best efforts. Here are a few more tips to remember about your readers:

- Readers do not notice correct spelling, but they do notice misspellings.

- Readers look past your sentences to get to your ideas—unless the sentences are awkward, poorly constructed, and frustrating to read.

- Readers notice when every sentence has the same rhythm as every other sentence, with no variety.

- Readers do not cheer when you use there , their , and they’re correctly, but they notice when you do not.

- Readers will notice the care with which you handled your assignment and your attention to detail in the delivery of an error-free document..

The first section of this book offers a useful review of grammar, mechanics, and usage. Use it to help you eliminate major errors in your writing and refine your understanding of the conventions of language. Do not hesitate to ask for help, too, from peer tutors in your academic department or in the college’s writing lab. In the meantime, use the checklist to help you edit your writing.

Editing Your Writing

- Are some sentences actually sentence fragments?

- Are some sentences run-on sentences? How can I correct them?

- Do some sentences need conjunctions between independent clauses?

- Does every verb agree with its subject?

- Is every verb in the correct tense?

- Are tense forms, especially for irregular verbs, written correctly?

- Have I used subject, object, and possessive personal pronouns correctly?

- Have I used who and whom correctly?

- Is the antecedent of every pronoun clear?

- Do all personal pronouns agree with their antecedents?

- Have I used the correct comparative and superlative forms of adjectives and adverbs?

- Is it clear which word a participial phrase modifies, or is it a dangling modifier?

Sentence Structure

- Are all my sentences simple sentences, or do I vary my sentence structure?

- Have I chosen the best coordinating or subordinating conjunctions to join clauses?

- Have I created long, overpacked sentences that should be shortened for clarity?

- Do I see any mistakes in parallel structure?

Punctuation

- Does every sentence end with the correct end punctuation?

- Can I justify the use of every exclamation point?

- Have I used apostrophes correctly to write all singular and plural possessive forms?

- Have I used quotation marks correctly?

Mechanics and Usage

- Can I find any spelling errors? How can I correct them?

- Have I used capital letters where they are needed?

- Have I written abbreviations, where allowed, correctly?

- Can I find any errors in the use of commonly confused words, such as to / too / two ?

Be careful about relying too much on spelling checkers and grammar checkers. A spelling checker cannot recognize that you meant to write principle but wrote principal instead. A grammar checker often queries constructions that are perfectly correct. The program does not understand your meaning; it makes its check against a general set of formulas that might not apply in each instance. If you use a grammar checker, accept the suggestions that make sense, but consider why the suggestions came up.

Proofreading requires patience; it is very easy to read past a mistake. Set your paper aside for at least a few hours, if not a day or more, so your mind will rest. Some professional proofreaders read a text backward so they can concentrate on spelling and punctuation. Another helpful technique is to slowly read a paper aloud, paying attention to every word, letter, and punctuation mark.

If you need additional proofreading help, ask a reliable friend, a classmate, or a peer tutor to make a final pass on your paper to look for anything you missed.

Remember to use proper format when creating your finished assignment. Sometimes an instructor, a department, or a college will require students to follow specific instructions on titles, margins, page numbers, or the location of the writer’s name. These requirements may be more detailed and rigid for research projects and term papers, which often observe the American Psychological Association (APA) or Modern Language Association (MLA) style guides, especially when citations of sources are included.

To ensure the format is correct and follows any specific instructions, make a final check before you submit an assignment.

With the help of the checklist, edit and proofread your essay.

Key Takeaways

- Revising and editing are the stages of the writing process in which you improve your work before producing a final draft.

- During revising, you add, cut, move, or change information in order to improve content.

- During editing, you take a second look at the words and sentences you used to express your ideas and fix any problems in grammar, punctuation, and sentence structure.

- Unity in writing means that all the ideas in each paragraph and in the entire essay clearly belong together and are arranged in an order that makes logical sense.

- Coherence in writing means that the writer’s wording clearly indicates how one idea leads to another within a paragraph and between paragraphs.

- Transitional words and phrases effectively make writing more coherent.

- Writing should be clear and concise, with no unnecessary words.

- Effective formal writing uses specific, appropriate words and avoids slang, contractions, clichés, and overly general words.

- Peer reviews, done properly, can give writers objective feedback about their writing. It is the writer’s responsibility to evaluate the results of peer reviews and incorporate only useful feedback.

- Remember to budget time for careful editing and proofreading. Use all available resources, including editing checklists, peer editing, and your institution’s writing lab, to improve your editing skills.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Revising Drafts

Rewriting is the essence of writing well—where the game is won or lost. —William Zinsser

What this handout is about

This handout will motivate you to revise your drafts and give you strategies to revise effectively.

What does it mean to revise?

Revision literally means to “see again,” to look at something from a fresh, critical perspective. It is an ongoing process of rethinking the paper: reconsidering your arguments, reviewing your evidence, refining your purpose, reorganizing your presentation, reviving stale prose.

But I thought revision was just fixing the commas and spelling

Nope. That’s called proofreading. It’s an important step before turning your paper in, but if your ideas are predictable, your thesis is weak, and your organization is a mess, then proofreading will just be putting a band-aid on a bullet wound. When you finish revising, that’s the time to proofread. For more information on the subject, see our handout on proofreading .

How about if I just reword things: look for better words, avoid repetition, etc.? Is that revision?

Well, that’s a part of revision called editing. It’s another important final step in polishing your work. But if you haven’t thought through your ideas, then rephrasing them won’t make any difference.

Why is revision important?

Writing is a process of discovery, and you don’t always produce your best stuff when you first get started. So revision is a chance for you to look critically at what you have written to see:

- if it’s really worth saying,

- if it says what you wanted to say, and

- if a reader will understand what you’re saying.

The process

What steps should i use when i begin to revise.

Here are several things to do. But don’t try them all at one time. Instead, focus on two or three main areas during each revision session:

- Wait awhile after you’ve finished a draft before looking at it again. The Roman poet Horace thought one should wait nine years, but that’s a bit much. A day—a few hours even—will work. When you do return to the draft, be honest with yourself, and don’t be lazy. Ask yourself what you really think about the paper.

- As The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers puts it, “THINK BIG, don’t tinker” (61). At this stage, you should be concerned with the large issues in the paper, not the commas.

- Check the focus of the paper: Is it appropriate to the assignment? Is the topic too big or too narrow? Do you stay on track through the entire paper?

- Think honestly about your thesis: Do you still agree with it? Should it be modified in light of something you discovered as you wrote the paper? Does it make a sophisticated, provocative point, or does it just say what anyone could say if given the same topic? Does your thesis generalize instead of taking a specific position? Should it be changed altogether? For more information visit our handout on thesis statements .

- Think about your purpose in writing: Does your introduction state clearly what you intend to do? Will your aims be clear to your readers?

What are some other steps I should consider in later stages of the revision process?

- Examine the balance within your paper: Are some parts out of proportion with others? Do you spend too much time on one trivial point and neglect a more important point? Do you give lots of detail early on and then let your points get thinner by the end?

- Check that you have kept your promises to your readers: Does your paper follow through on what the thesis promises? Do you support all the claims in your thesis? Are the tone and formality of the language appropriate for your audience?

- Check the organization: Does your paper follow a pattern that makes sense? Do the transitions move your readers smoothly from one point to the next? Do the topic sentences of each paragraph appropriately introduce what that paragraph is about? Would your paper work better if you moved some things around? For more information visit our handout on reorganizing drafts.

- Check your information: Are all your facts accurate? Are any of your statements misleading? Have you provided enough detail to satisfy readers’ curiosity? Have you cited all your information appropriately?

- Check your conclusion: Does the last paragraph tie the paper together smoothly and end on a stimulating note, or does the paper just die a slow, redundant, lame, or abrupt death?

Whoa! I thought I could just revise in a few minutes

Sorry. You may want to start working on your next paper early so that you have plenty of time for revising. That way you can give yourself some time to come back to look at what you’ve written with a fresh pair of eyes. It’s amazing how something that sounded brilliant the moment you wrote it can prove to be less-than-brilliant when you give it a chance to incubate.

But I don’t want to rewrite my whole paper!

Revision doesn’t necessarily mean rewriting the whole paper. Sometimes it means revising the thesis to match what you’ve discovered while writing. Sometimes it means coming up with stronger arguments to defend your position, or coming up with more vivid examples to illustrate your points. Sometimes it means shifting the order of your paper to help the reader follow your argument, or to change the emphasis of your points. Sometimes it means adding or deleting material for balance or emphasis. And then, sadly, sometimes revision does mean trashing your first draft and starting from scratch. Better that than having the teacher trash your final paper.

But I work so hard on what I write that I can’t afford to throw any of it away

If you want to be a polished writer, then you will eventually find out that you can’t afford NOT to throw stuff away. As writers, we often produce lots of material that needs to be tossed. The idea or metaphor or paragraph that I think is most wonderful and brilliant is often the very thing that confuses my reader or ruins the tone of my piece or interrupts the flow of my argument.Writers must be willing to sacrifice their favorite bits of writing for the good of the piece as a whole. In order to trim things down, though, you first have to have plenty of material on the page. One trick is not to hinder yourself while you are composing the first draft because the more you produce, the more you will have to work with when cutting time comes.

But sometimes I revise as I go

That’s OK. Since writing is a circular process, you don’t do everything in some specific order. Sometimes you write something and then tinker with it before moving on. But be warned: there are two potential problems with revising as you go. One is that if you revise only as you go along, you never get to think of the big picture. The key is still to give yourself enough time to look at the essay as a whole once you’ve finished. Another danger to revising as you go is that you may short-circuit your creativity. If you spend too much time tinkering with what is on the page, you may lose some of what hasn’t yet made it to the page. Here’s a tip: Don’t proofread as you go. You may waste time correcting the commas in a sentence that may end up being cut anyway.

How do I go about the process of revising? Any tips?

- Work from a printed copy; it’s easier on the eyes. Also, problems that seem invisible on the screen somehow tend to show up better on paper.

- Another tip is to read the paper out loud. That’s one way to see how well things flow.

- Remember all those questions listed above? Don’t try to tackle all of them in one draft. Pick a few “agendas” for each draft so that you won’t go mad trying to see, all at once, if you’ve done everything.

- Ask lots of questions and don’t flinch from answering them truthfully. For example, ask if there are opposing viewpoints that you haven’t considered yet.

Whenever I revise, I just make things worse. I do my best work without revising

That’s a common misconception that sometimes arises from fear, sometimes from laziness. The truth is, though, that except for those rare moments of inspiration or genius when the perfect ideas expressed in the perfect words in the perfect order flow gracefully and effortlessly from the mind, all experienced writers revise their work. I wrote six drafts of this handout. Hemingway rewrote the last page of A Farewell to Arms thirty-nine times. If you’re still not convinced, re-read some of your old papers. How do they sound now? What would you revise if you had a chance?

What can get in the way of good revision strategies?

Don’t fall in love with what you have written. If you do, you will be hesitant to change it even if you know it’s not great. Start out with a working thesis, and don’t act like you’re married to it. Instead, act like you’re dating it, seeing if you’re compatible, finding out what it’s like from day to day. If a better thesis comes along, let go of the old one. Also, don’t think of revision as just rewording. It is a chance to look at the entire paper, not just isolated words and sentences.

What happens if I find that I no longer agree with my own point?

If you take revision seriously, sometimes the process will lead you to questions you cannot answer, objections or exceptions to your thesis, cases that don’t fit, loose ends or contradictions that just won’t go away. If this happens (and it will if you think long enough), then you have several choices. You could choose to ignore the loose ends and hope your reader doesn’t notice them, but that’s risky. You could change your thesis completely to fit your new understanding of the issue, or you could adjust your thesis slightly to accommodate the new ideas. Or you could simply acknowledge the contradictions and show why your main point still holds up in spite of them. Most readers know there are no easy answers, so they may be annoyed if you give them a thesis and try to claim that it is always true with no exceptions no matter what.

How do I get really good at revising?

The same way you get really good at golf, piano, or a video game—do it often. Take revision seriously, be disciplined, and set high standards for yourself. Here are three more tips:

- The more you produce, the more you can cut.

- The more you can imagine yourself as a reader looking at this for the first time, the easier it will be to spot potential problems.

- The more you demand of yourself in terms of clarity and elegance, the more clear and elegant your writing will be.

How do I revise at the sentence level?

Read your paper out loud, sentence by sentence, and follow Peter Elbow’s advice: “Look for places where you stumble or get lost in the middle of a sentence. These are obvious awkwardness’s that need fixing. Look for places where you get distracted or even bored—where you cannot concentrate. These are places where you probably lost focus or concentration in your writing. Cut through the extra words or vagueness or digression; get back to the energy. Listen even for the tiniest jerk or stumble in your reading, the tiniest lessening of your energy or focus or concentration as you say the words . . . A sentence should be alive” (Writing with Power 135).

Practical advice for ensuring that your sentences are alive:

- Use forceful verbs—replace long verb phrases with a more specific verb. For example, replace “She argues for the importance of the idea” with “She defends the idea.”

- Look for places where you’ve used the same word or phrase twice or more in consecutive sentences and look for alternative ways to say the same thing OR for ways to combine the two sentences.

- Cut as many prepositional phrases as you can without losing your meaning. For instance, the following sentence, “There are several examples of the issue of integrity in Huck Finn,” would be much better this way, “Huck Finn repeatedly addresses the issue of integrity.”

- Check your sentence variety. If more than two sentences in a row start the same way (with a subject followed by a verb, for example), then try using a different sentence pattern.

- Aim for precision in word choice. Don’t settle for the best word you can think of at the moment—use a thesaurus (along with a dictionary) to search for the word that says exactly what you want to say.

- Look for sentences that start with “It is” or “There are” and see if you can revise them to be more active and engaging.

- For more information, please visit our handouts on word choice and style .

How can technology help?

Need some help revising? Take advantage of the revision and versioning features available in modern word processors.

Track your changes. Most word processors and writing tools include a feature that allows you to keep your changes visible until you’re ready to accept them. Using “Track Changes” mode in Word or “Suggesting” mode in Google Docs, for example, allows you to make changes without committing to them.

Compare drafts. Tools that allow you to compare multiple drafts give you the chance to visually track changes over time. Try “File History” or “Compare Documents” modes in Google Doc, Word, and Scrivener to retrieve old drafts, identify changes you’ve made over time, or help you keep a bigger picture in mind as you revise.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Elbow, Peter. 1998. Writing With Power: Techniques for Mastering the Writing Process . New York: Oxford University Press.

Lanham, Richard A. 2006. Revising Prose , 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

Zinsser, William. 2001. On Writing Well: The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction , 6th ed. New York: Quill.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Teacher Habits

Helping Teachers inside the Classroom and Out

How to Write an Opinion Essay (With Tips and Examples)

Are you struggling with how to write an opinion essay that effectively communicates your viewpoint on a particular topic while providing strong evidence to back it up? Fear not! In this comprehensive guide, we will walk you through the process of crafting a quality opinion essay, from understanding the purpose and structure to choosing engaging topics and employing effective writing techniques. Let’s dive in!

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

- Opinion essays are formal pieces of writing that express the author’s viewpoint on a given subject.

- Crafting an effective thesis statement and outline, choosing engaging topics, using formal language and tone, addressing counterarguments and maintaining logical flow are essential for creating compelling opinion essays.

- The revision process is key to producing polished opinion essays that effectively convey one’s opinions.

What is an Opinion Essay?

An opinion essay, also known as an opinion paper, is a formal piece of writing wherein the author expresses their viewpoint on a given subject and provides factual and anecdotal evidence to substantiate their opinion. The purpose of an opinion essay is to articulate a position in a clear and informative manner, following a proper opinion essay structure. Opinion essays are commonly found in newspapers and social media, allowing individuals to articulate their perspectives and opinions on a specific topic, striving to create a perfect opinion essay.

While the focus of an opinion essay should be on the writer’s own opinion concerning the issue, it necessitates more meticulous planning and effort than simply articulating one’s own thoughts on a particular topic. The arguments in an opinion essay should be grounded on well-researched data, making it crucial to consult pertinent information, including the definition, topics, opinion writing examples, and requirements, to write an opinion essay and transform novice writers into proficient writers.

Crafting the Perfect Thesis Statement

A strong thesis statement is the foundation of a great essay. It clearly expresses the writer’s opinion and sets the stage for the rest of the essay. To craft the perfect thesis statement, start by perusing the essay prompt multiple times to ensure you fully understand the question or topic you are being asked to discuss. Once you have a clear understanding of the topic, construct your opinion and conduct thorough research to locate evidence to corroborate your stance and examine counterarguments or contrasting perspectives.

Remember, your thesis statement should provide a succinct overview of the opinion essay and serve as a guide for the remainder of the paper. By crafting a strong thesis statement, you will be able to capture your reader’s attention and set the tone for a well-structured and persuasive essay.

Building a Solid Opinion Essay Outline

A well-structured opinion essay format is crucial for organizing your thoughts and ensuring that your entire essay flows smoothly from one point to the next. An opinion essay outline typically comprises an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion, following the standard five-paragraph essay structure.

Let’s delve deeper into each component of the outline. The introduction should provide a brief overview of the topic and your opinion on it. It should be.

Introduction

The introduction of your opinion essay should hook the reader and provide an overview of the essay’s content. To achieve this, consider addressing the reader directly, introducing a quotation, posing thought-provoking or rhetorical questions, or referring to a remarkable or unconventional fact, concept, or scenario.

It is essential to introduce the topic clearly in the introduction to avoid superfluous phrases and inapplicable facts that are not pertinent to the topic. By crafting an engaging introduction, you will set the stage for a compelling and well-organized opinion essay.

Body Paragraphs

The body paragraphs of your good opinion essay should provide arguments and supporting examples to substantiate your opinion. Begin each paragraph with a distinct topic sentence and use credible sources to provide substantiation for your viewpoint with dependable data.

Addressing counterarguments in your body paragraphs can also enhance your essay by illustrating a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter and fortifying your stance.

Organize your body paragraphs in a coherent manner, ensuring that each argument and supporting example flows logically from one to the next. This will make it easier for your reader to follow your train of thought and strengthen the overall impact of your essay.

The conclusion of your opinion essay should summarize the main points and restate your opinion in a new manner, providing a sense of closure and completion to your argument. Keep your conclusion concise and avoid introducing new information or arguments at this stage. By effectively summarizing your main points and restating your opinion, you will leave a lasting impression on your reader and demonstrate the strength of your argument.

In addition to summarizing your main ideas, consider providing a final thought or call to action that will leave your reader pondering the implications of your essay. This can further reinforce the impact of your conclusion and leave a lasting impression on your reader.

Choosing Engaging Opinion Essay Topics

Selecting engaging topics for opinion essays is crucial for capturing the reader’s interest and encouraging critical thinking. While there are an abundance of potential questions or topics that could be utilized for an opinion essay, it is important to choose topics that are relevant, interesting, and thought-provoking.

To find inspiration for engaging opinion essay topics, consider browsing the Op-Ed sections of newspapers, exploring social media debates, or even reflecting on your own experiences and interests. Keep in mind that a well-chosen topic not only draws the reader’s attention, but also stimulates critical thinking and fosters insightful discussions.

Opinion Essay Writing Techniques

Effective opinion essay writing techniques include using formal language and tone, addressing counterarguments, and maintaining logical flow.

Let’s explore each of these techniques in more detail.

Formal Language and Tone

Using formal language and tone in your opinion essay is essential for conveying a sense of professionalism and credibility. This can be achieved by avoiding slang, jargon, and colloquial expressions, as well as short forms and over-generalizations. Moreover, expressing your opinion without utilizing the personal pronoun “I” can give your essay a seemingly more objective approach.

Remember that the recommended tense for composing an opinion essay is present tense. By maintaining a formal language and tone throughout your essay, you will demonstrate your expertise on the subject matter and instill confidence in your reader.

Addressing Counterarguments

Addressing counterarguments in your opinion essay is an effective way to demonstrate a well-rounded understanding of the topic and strengthen your position. To do this, introduce opposing viewpoints in a straightforward manner and provide evidence to counter them. This not only showcases your comprehension of the subject matter, but also bolsters your own argument by refuting potential objections.

By acknowledging and addressing counterarguments, you will create a more balanced and persuasive opinion essay that encourages critical thinking and engages your reader.

Maintaining Logical Flow

Ensuring your opinion essay maintains a logical flow is critical for enabling your reader to follow your arguments and evidence with ease. To achieve this, utilize precise and succinct words, compose legible sentences, and construct well-structured paragraphs. Incorporating transitional words and varied sentence structures can also enhance the flow of your essay.

By maintaining a logical flow throughout your opinion essay, you will create an organized and coherent piece of writing that effectively communicates your viewpoint and supporting arguments to your reader.

Analyzing Opinion Essay Examples

Analyzing opinion essay examples can help improve your understanding of the structure and style required for this type of writing. Numerous examples are available online as a source of reference, providing valuable insights into how other writers have approached similar topics and structured their essays.

By examining opinion essay examples, you will be better equipped to identify the elements of a successful essay and apply them to your own writing. This will not only enhance your understanding of opinion essay writing, but also inspire you to develop your own unique voice and style.

The Revision Process: Polishing Your Opinion Essay

The revision process is essential for polishing your opinion essay, ensuring clarity, logical flow, and proper grammar and punctuation. Start by rereading your first draft, making improvements as you progress and rectifying any grammar errors that may be observed. Having another individual review your writing, such as a family member or friend, can provide candid feedback, allowing you to refine your essay further.

The ultimate step in composing an opinion essay is proofreading. This final review will ensure that your essay is polished and free from errors, resulting in a well-crafted and persuasive piece of writing that effectively communicates your opinion on the topic at hand.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do you start an opinion essay.

To start an opinion essay, begin by stating the subject of your essay and expressing your perspective on it. Follow up by using an interesting or provocative statement to capture the reader’s attention.

Introduce your essay by restating the question in your own words, making sure to make your opinion clear throughout your essay.

What is the structure of an opinion essay?

An opinion essay is typically structured with an introduction containing a thesis statement, body paragraphs providing arguments or reasons that support your view, and a conclusion.

Each section of the essay should be written in a formal tone to ensure clarity and effectiveness.

What is the format of an opinion paragraph?

An opinion paragraph typically begins with a clear statement of the opinion, followed by body sentences providing evidence and support for the opinion, before finally summarizing or restating the opinion in a concluding sentence.

It should be written in a formal tone.

What not to write in an opinion essay?

When writing an opinion essay, make sure to stay on topic, avoid slang and jargon, introduce the topic clearly and concisely, and do not include unnecessary facts that do not relate directly to the question.

Use a formal tone and keep your conclusion clear in the first sentence.

What is the purpose of an opinion essay?

The purpose of an opinion essay is to articulate a position in a clear and informative manner, providing evidence to support it.

This type of essay requires the writer to research the topic thoroughly and present their opinion in a logical and convincing way. They must also be able to back up their opinion with facts and evidence.

In conclusion, crafting a quality opinion essay requires a clear understanding of the purpose and structure of this type of writing, as well as the ability to choose engaging topics and employ effective writing techniques. By following the guidelines and tips provided in this guide, you will be well on your way to creating a compelling and persuasive opinion essay that effectively articulates your viewpoint and supporting arguments.

Remember, practice makes perfect. The more you write and revise, the more adept you will become at crafting insightful and impactful opinion essays. So, go forth and share your opinions with the world, backed by strong evidence and persuasive writing!

Have a language expert improve your writing

Check your paper for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- College essay

How to Revise Your College Admissions Essay | Examples

Published on September 24, 2021 by Kirsten Courault . Revised on December 8, 2023.

Revision and editing are essential to make your college essay the best it can be.

When you’ve finished your draft, first focus on big-picture issues like the overall narrative and clarity of your essay. Then, check your style and tone . You can do this for free with a paraphrasing tool . Finally, when you’re happy with your essay, polish up the details of grammar and punctuation with the essay checker , and don’t forget to check that it’s within the word count limit .

Remember to take a break after you finish writing and after each stage of revision. You should go through several rounds of revisions and ask for feedback on your drafts from a teacher, friend or family member, or professional essay coach. If you don’t have much time , focus on clarity and grammar by using a grammar checker .

You can also check out our college essay examples to get an idea of how to turn a weak essay into a strong one.

Table of contents

Big picture: check for overall message, flow, and clarity, voice: check for style and tone, details: check for grammar and punctuation, feedback: get a second opinion, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about college application essays.

In your first reading, don’t touch grammatical errors; just read through the entire essay to check the overall message, flow, and content quality.

Check your overall message

After reading your essay, answer the following questions:

- What message do I take away from my essay?

- Did I answer the prompt?

- Does it end with an insight, or does it just tell a story?

- Do I use stories and examples to demonstrate my values? Do these values match the university’s values?

- Is it focused on me, or is it too focused on another person or idea?

If you answer any of these questions negatively, rewrite your essay to fix these problems.

Check transitions and flow

Underline every paragraph’s topic and transition sentence to visualize whether a clear structure and natural flow are maintained throughout your essay. If necessary, rewrite or rearrange these topic and transition sentences to create a logical outline. Then, reread the entire essay to check it flows naturally.

Also check that your application essay’s introduction catches the reader’s attention and that you end the essay with an effective payoff that builds on what comes before.

Check for content quality

Highlight any parts that are unclear, boring, or unnecessary. Afterward, go back and clarify the unclear sections, embellish the boring parts with vivid language to help your essay stand out , and delete any unnecessary sentences or words.

Make sure everything in the essay is showing off what colleges are looking for : your personality, interests, and positive traits.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

To ensure you use the correct tone for your essay, check whether there’s vulnerability, authenticity, a positive and polite tone, and a balance between casual and formal. Ask yourself the following questions:

- Does the essay sound like me? Do my word choices seem natural?

- Is it vulnerable? Do I write about myself in a way that demonstrates genuine self-reflection?

- Is the tone conversational but respectful?

- Is it polite and respectful about sensitive topics?

Read it aloud to catch errors

Hearing your essay read aloud can help you to catch problems with style and voice that you might miss when reading it silently. For example, you may overuse certain words, have unparallel sentence structures , or use vocabulary that sounds unnatural.

You should read your essay aloud several times throughout the revision process. This can also help you find grammar and punctuation errors. You can try the following:

- Read it aloud yourself.

- Have someone read it aloud for you.

- Put it into a text-to-speech program.

- Record yourself and play it back.

After checking for big-picture and stylistic issues, read your essay again for grammar and punctuation errors.

Run spell check

First, run spell check in your word processor to find any obvious spelling, grammar, or punctuation mistakes.

Punctuation, capitalization, and verb errors

Spell check might miss some minor errors in punctuation and capitalization . With verbs , check for correct subject-verb agreement and verb tense .

Sentence structure

Check for common sentence structure mistakes such as sentence fragments and run-ons. Throughout your essay, ensure you vary your sentence lengths and structures for an interesting flow.

Check for parallel structure in more complex sentences. Maintain clarity by fixing any dangling or misplaced modifiers .

Consistency

Be consistent with your use of contractions, acronyms, and verb tenses.

Whenever you reuse an essay for another university, make sure you replace any names from or references to the previous university.

You should get feedback on your essay before you submit your application. Stick to around two to three readers to avoid too much conflicting advice.

Ask for feedback from people who know you well, such as teachers or family members. It’s also important to get feedback on the content, tone, and flow of your essay from someone who is familiar with the college admissions process and has strong language skills.

You might want to consider getting professional help from an essay coach or editor. Editors should only give advice and suggestions; they should never rewrite your essay for you.