Everything You Should Know about the John Locke Institute (JLI) Essay Competition

By Jin Chow

Co-founder of Polygence, Forbes 30 Under 30 for Education

2 minute read

We first wrote about the world-famous John Locke Institute (JLI) Essay Competition in our list of 20 writing contests for high school students . This contest is a unique opportunity to refine your argumentation skills on fascinating and challenging topics that aren’t explored in the classroom.

The Oxford philosopher, medical doctor, political scientist, and economist John Locke was a big believer in challenging old habits of the mind. In that spirit, the JLI started this contest to challenge students to be more adventurous in their thinking.

While not quite as prestigious as getting published in The Concord Review , winning the grand prize or placing in one of the 7 categories of the JLI Essay Competition can get your college application noticed by top schools like Princeton, Harvard, Oxford, and Cambridge. Awards include $2,000 scholarships (for category winners) and a $10,000 scholarship for the grand prize. (The scholarships can be applied to the JLI’s Summer Schools at Oxford, Princeton, or Washington D.C., or to its Gap Year programs in Oxford, Guatemala, or Washington, D.C.)

But winning isn’t necessarily the best thing about it. Simply entering the contest and writing your essay will give you a profound learning experience like no other. Add to that the fact that your entry will be read and possibly commented on by some of the top minds at Oxford and Princeton and it’s free to enter the competition . The real question is: why wouldn’t you enter? Here’s a guide to get you started on your essay contest entry.

Eligibility

The John Locke Institute Essay Competition is open to any student anywhere in the world , ages 15-18. Students 14 or under are eligible for the Junior prize.

JLI Essay Competition Topics

The essay questions change from year to year. You can choose from 7 different categories (Philosophy, Politics, Economics, History, Psychology, Theology, and Law). Within each category, there are 3 intriguing questions you can pick from. When you’re debating which question to write about, here’s a tip. Choose whichever question excites, upsets, or gives you any kind of strong emotional response. If you’re passionate about a topic, it will come through in your research and your writing. If you have any lived experience on the subject, that also helps.

re are some sample questions the 2023 contest for each of the seven JLI essay subject categories and the Junior Prize (the questions change each year):

Philosophy : Is tax theft?

Politics : Do the results of elections express the will of the people?

Economics : What would happen if we banned billionaires?

History : Which has a bigger effect on history: the plans of the powerful or their mistakes?

Psychology : Can happiness be measured?

Theology : What distinguishes a small religion from a large cult?

Law : Are there too many laws?

Junior Prize : What, if anything, do your parents owe you?

John Locke Writing Contest Requirements

Your essay must not exceed 2,000 words (not counting diagrams, tables of data, endnotes, bibliography, or authorship declaration) and must address only one of the questions in your chosen subject category. No footnotes are allowed, but you may include in-text citations or endnotes.

Timeline and Deadlines

January - New essay questions are released

April 1st - Registration opens

May 31st - Registration deadline

June 30th - Essay submission deadline

We highly recommend you check the JLI website as soon as the new questions are released in January and start researching and writing as soon as you can after choosing your topic. You must register for the contest by the end of May. The deadline for the essay submission itself is at the end of June, but we also recommend that you submit it earlier in case any problems arise. If you start right away in January, you can have a few months to work on your essay.

John Locke Institute Essay Competition Judging Criteria

While the JLI says that their grading system is proprietary, they do also give you this helpful paragraph that describes what they are looking for: “Essays will be judged on knowledge and understanding of the relevant material , the competent use of evidence , quality of argumentation, originality, structure, writing style and persuasive force. The very best essays are likely to be those which would be capable of changing somebody's mind . Essays which ignore or fail to address the strongest objections and counter-arguments are unlikely to be successful. Candidates are advised to answer the question as precisely and directly as possible. ” (We’ve bolded important words to keep in mind.)

You can also join the JLI mailing list (scroll to the bottom of that page) to get contest updates and to learn more about what makes for a winning essay.

Research and Essay Writing Tactics

Give yourself a baseline. First, just write down all your thoughts on the subject without doing any research. What are your gut-level opinions? What about this particular question intrigued you the most? What are some counter-arguments you can think of right away? What you are trying to do here is identify holes in your knowledge or understanding of the subject. What you don’t know or are unsure about can guide your research. Be sure to find evidence to support all the things you think you already know.

Create a reading/watching list of related books, interviews, articles, podcasts, documentaries, etc. that relate to your topic. Find references that both support and argue against your argument. Choose the most highly reputable sources you can find. You may need to seek out and speak to experts to help you locate the best sources. Read and take notes. Address those questions and holes in the knowledge you identified earlier. Also, continue to read widely and think about your topic as you observe the world from day to day. Sometimes unrelated news stories, literature, film, songs, and visual art can give you an unexpected insight into your essay question. Remember that c is a learning experience and that you are not going to have a rock-solid argument all at once.

Read past winning essays . These will give you a sense of the criteria judges are using to select winning work. These essays are meant to convince the judges of a very specific stance. The argument must be clear and must include evidence to support it. You will note that winning entries tend to get straight to the point, show an impressive depth of knowledge on the subject with citations to reputable sources, flow with excellent reasoning, and use precise language. They don’t include flowery digressions. Save that for a different type of writing.

Proof your work with a teacher or mentor if possible . Even though your argument needs to be wholly your own, it certainly helps to bounce ideas around with someone who cares about the topic. A teacher or mentor can help you explore different options if you get stuck and point you toward new resources. They can offer general advice and point out errors or weaknesses. Working with a teacher or mentor is important for another reason. When you submit your entry, you will be required to provide the email address of an “academic referee” who is familiar with your work. This should be a teacher or mentor who is not related to you.

Research and Prepare for your Competition or Fair

Polygence pairs you with an expert mentor in your area of passion. Together, you work to create a high quality research project that is uniquely your own. Our highly-specialized mentors can help guide you to feel even more prepared for an upcoming fair or competion. We also offer options to explore multiple topics, or to showcase your final product!

Second Treatise of Government

42 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Preface-Chapter 3

Chapters 4-7

Chapters 8-11

Chapters 12-15

Chapters 16-19

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Is there a modern-day equivalent to Robert Filmer’s assertion of the divine right of kings? If so, what is it?

If human beings inhabit the state of nature continually, do they also in some way inhabit the state of war continually as well? Explaining your reasoning.

What are the key differences between a community and a political society? Use examples from the text to support your reasoning.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By these authors

An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

The First Treatise of Government

Featured Collections

Challenging Authority

View Collection

Essays & Speeches

Philosophy, Logic, & Ethics

Politics & Government

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: September 20, 2019 | Original: November 9, 2009

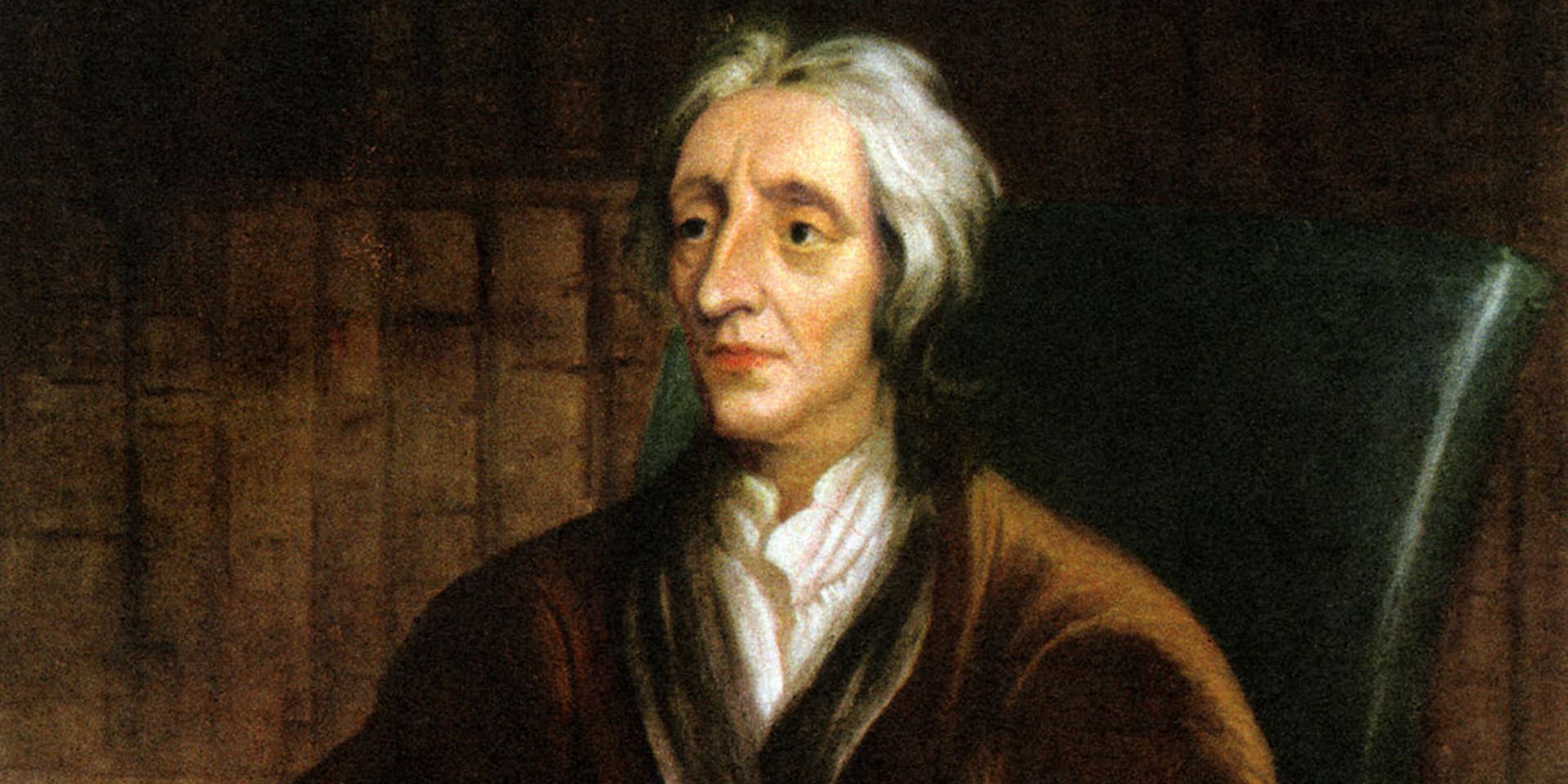

The English philosopher and political theorist John Locke (1632-1704) laid much of the groundwork for the Enlightenment and made central contributions to the development of liberalism. Trained in medicine, he was a key advocate of the empirical approaches of the Scientific Revolution. In his “Essay Concerning Human Understanding,” he advanced a theory of the self as a blank page, with knowledge and identity arising only from accumulated experience. His political theory of government by the consent of the governed as a means to protect the three natural rights of “life, liberty and estate” deeply influenced the United States’ founding documents. His essays on religious tolerance provided an early model for the separation of church and state.

John Locke’s Early Life and Education

John Locke was born in 1632 in Wrighton, Somerset. His father was a lawyer and small landowner who had fought on the Parliamentarian side during the English Civil Wars of the 1640s. Using his wartime connections, he placed his son in the elite Westminster School.

Did you know? John Locke’s closest female friend was the philosopher Lady Damaris Cudworth Masham. Before she married the two had exchanged love poems, and on his return from exile, Locke moved into Lady Damaris and her husband’s household.

Between 1652 and 1667, John Locke was a student and then lecturer at Christ Church, Oxford, where he focused on the standard curriculum of logic, metaphysics and classics. He also studied medicine extensively and was an associate of Robert Hooke, Robert Boyle and other leading Oxford scientists.

John Locke and the Earl of Shaftesbury

In 1666 Locke met the parliamentarian Anthony Ashley Cooper, later the first Earl of Shaftesbury. The two struck up a friendship that blossomed into full patronage, and a year later Locke was appointed physician to Shaftesbury’s household. That year he supervised a dangerous liver operation on Shaftesbury that likely saved his patron’s life.

For the next two decades, Locke’s fortunes were tied to Shaftesbury, who was first a leading minister to Charles II and then a founder of the opposing Whig Party . Shaftesbury led the 1679 “exclusion” campaign to bar the Catholic duke of York (the future James II) from the royal succession. When that failed, Shaftesbury began to plot armed resistance and was forced to flee to Holland in 1682. Locke would follow his patron into exile a year later, returning only after the Glorious Revolution had placed the Protestant William III on the throne.

John Locke’s Publications

During his decades of service to Shaftesbury, John Locke had been writing. In the six years following his return to England he published all of his most significant works.

Locke’s “Essay Concerning Human Understanding” (1689) outlined a theory of human knowledge, identity and selfhood that would be hugely influential to Enlightenment thinkers. To Locke, knowledge was not the discovery of anything either innate or outside of the individual, but simply the accumulation of “facts” derived from sensory experience. To discover truths beyond the realm of basic experience, Locke suggested an approach modeled on the rigorous methods of experimental science, and this approach greatly impacted the Scientific Revolution .

John Locke’s Views on Government

The “Two Treatises of Government” (1690) offered political theories developed and refined by Locke during his years at Shaftesbury’s side. Rejecting the divine right of kings, Locke said that societies form governments by mutual (and, in later generations, tacit) agreement. Thus, when a king loses the consent of the governed, a society may remove him—an approach quoted almost verbatim in Thomas Jefferson 's 1776 Declaration of Independence . Locke also developed a definition of property as the product of a person’s labor that would be foundational for both Adam Smith’s capitalism and Karl Marx ’s socialism. Locke famously wrote that man has three natural rights: life, liberty and property.

In his “Thoughts Concerning Education” (1693), Locke argued for a broadened syllabus and better treatment of students—ideas that were an enormous influence on Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s novel “Emile” (1762).

In three “Letters Concerning Toleration” (1689-92), Locke suggested that governments should respect freedom of religion except when the dissenting belief was a threat to public order. Atheists (whose oaths could not be trusted) and Catholics (who owed allegiance to an external ruler) were thus excluded from his scheme. Even within its limitations, Locke’s toleration did not argue that all (Protestant) beliefs were equally good or true, but simply that governments were not in a position to decide which one was correct.

John Locke’s Death

Locke spent his final 14 years in Essex at the home of Sir Francis Masham and his wife, the philosopher Lady Damaris Cudworth Masham. He died there on October 28, 1704 , as Lady Damaris read to him from the Psalms.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Upcoming Summer 2024 Application Deadline is April 14, 2024.

Click here to apply.

Featured Posts

10 Tips to Help You Win Stanford’s ProCo Competition in 2024

8 High School Entrepreneurship Programs You Should Check Out

10 Forensic Science Summer Camps for High School Students

10 Lab Internships For High School Students

7 Tips to Help You Win NASA's Space Apps Challenge

Ohio State University's YSP - Should You Consider It?

Why the Road to College Starts in Freshman Year – Part 1

10 Tips to Help You Win the PicoCTF Competition in 2024

Georgia Tech's Pre-College Program - Is it Worth It?

25+ Best Science Research Ideas for High School Students

- 12 min read

The Ultimate Guide to the John Locke Essay Competition

Humanities and social sciences students often lack the opportunities to compete at the global level and demonstrate their expertise. Competitions like ISEF, Science Talent Search, and MIT Think are generally reserved for students in fields like biology, physics, and chemistry.

At Lumiere, many of our talented non-STEM students, who have a flair for writing are looking for ways to flex their skills. In this piece, we’ll go over one such competition - the John Locke Essay Competition. If you’re interested in learning more about how we guide students to win essay contests like this, check out our main page .

What is the John Locke Essay Competition?

The essay competition is one of the various programs conducted by the John Locke Institute (JLI) every year apart from their summer and gap year courses. To understand the philosophy behind this competition, it’ll help if we take a quick detour to know more about the institute that conducts it.

Founded in 2011, JLI is an educational organization that runs summer and gap year courses in the humanities and social sciences for high school students. These courses are primarily taught by academics from Oxford and Princeton along with some other universities. The organization was founded by Martin Cox. Our Lumiere founder, Stephen, has met Martin and had a very positive experience. Martin clearly cares about academic rigor.

The institute's core belief is that the ability to evaluate the merit of information and develop articulate sound judgments is more important than merely consuming information. The essay competition is an extension of the institute - pushing students to reason through complex questions in seven subject areas namely Philosophy, Politics, Economics, History, Psychology, Theology, and Law.

The organization also seems to have a strong record of admissions of alumni to the top colleges in the US and UK. For instance, between 2011 and 2022, over half of John Locke alumni have gone on to one of eight colleges: Chicago, Columbia, Georgetown, Harvard, Pennsylvania, Princeton, Stanford, and Yale.

How prestigious is the John Locke Contest?

The John Locke Contest is a rigorous and selective writing competition in the social sciences and humanities. While it is not as selective as the Concord Review and has a much broader range of students who can receive prizes, it is still considered a highly competitive program.

Winning a John Locke essay contest will have clear benefits for you in your application process to universities and would reflect well on your application. On the other hand, a shortlist or a commendation might not have a huge impact given that it is awarded to many students (more on this later).

What is the eligibility for the contest?

Students, of any country, who are 18 years old or younger before the date of submission can submit. They also have a junior category for students who are fourteen years old, or younger, on the date of the submission deadline.

Who SHOULD consider this competition?

We recommend this competition for students who are interested in social sciences and humanities, in particular philosophy, politics, and economics. It is also a good fit for students who enjoy writing, want to dive deep into critical reasoning, and have some flair in their writing approach (more on that below).

While STEM students can of course compete, they will have to approach the topics through a social science lens. For example, in 2021, one of the prompts in the division of philosophy was, ‘Are there subjects about which we should not even ask questions?’ Here, students of biology can comfortably write about topics revolving around cloning, gene alteration, etc, however, they will have to make sure that they are able to ground this in the theoretical background of scientific ethics and ethical philosophy in general.

Additional logistics

Each essay should address only one of the questions in your chosen subject category, and must not exceed 2000 words (not counting diagrams, tables of data, footnotes, bibliography, or authorship declaration).

If you are using an in-text-based referencing format, such as APA, your in-text citations are included in the word limit.

You can submit as many essays as you want in any and all categories. (We recommend aiming for only one given how time-consuming it can be to come up with a single good-quality submission)

Important dates

Prompts for the 2023 competition will be released in January 2023. Your submission will be due around 6 months later in June. Shortlisted candidates will be notified in mid-July which will be followed by the final award ceremony in September.

How much does it cost to take part?

What do you win?

A scholarship that will offset the cost of attending a course at the JLI. The amount will vary between $2000 and $10,000 based on whether you are a grand prize winner (best essay across all categories) or a subject category winner. (JLI programs are steeply-priced and even getting a prize in your category would not cover the entire cost of your program. While the website does not mention the cost of the upcoming summer program, a different website mentions it to be 3,000 GBP or 3600 USD)

If you were shortlisted, most probably, you will also receive a commendation certificate and an invitation to attend an academic ceremony at Oxford. However, even here, you will have to foot the bill for attending the conference, which can be a significant one if you are an international student.

How do you submit your entry?

You submit your entry through the website portal that will show up once the prompts for the next competition are up in January! You have to submit your essay in pdf format where the title of the pdf attachment should read SURNAME, First Name, Category, and Question Number (e.g. POPHAM, Alexander, Psychology, Q2).

What are the essay prompts like?

We have three insights here.

Firstly, true to the spirit of the enlightenment thinker it is named after, most of the prompts have a philosophical bent and cover ethical, social, and political themes. In line with JLI’s general philosophy, they force you to think hard and deeply about the topics they cover. Consider a few examples to understand this better:

“Are you more moral than most people you know? How do you know? Should you strive to be more moral? Why or why not?” - Philosophy, 2021

“What are the most important economic effects - good and bad - of forced redistribution? How should this inform government policy?” - Economics, 2020

“Why did the Jesus of Nazareth reserve his strongest condemnation for the self-righteous?” - Theology, 2021

“Should we judge those from the past by the standards of today? How will historians in the future judge us?” - History, 2021

Secondly, at Lumiere, our analysis is that most of these prompts are ‘deceptively rigorous’ because the complexity of the topic reveals itself gradually. The topics do not give you a lot to work with and it is only when you delve deeper into one that you realize the extent to which you need to research/read more. In some of the topics, you are compelled to define the limits of the prompt yourself and in turn, the scope of your essay. This can be a challenging exercise. Allow me to illustrate this with an example of the 2019 philosophy prompt.

“Aristotelian virtue ethics achieved something of a resurgence in the twentieth century. Was this progress or retrogression?”

Here you are supposed to develop your own method for determining what exactly constitutes progress in ethical thought. This in turn involves familiarizing yourself with existing benchmarks of measurement and developing your own method if required. This is a significant intellectual exercise.

Finally, a lot of the topics are on issues of contemporary relevance and especially on issues that are contentious . For instance, in 2019, one of the prompts for economics was about the benefits and costs of immigration whereas the 2020 essay prompt for theology was about whether Islam is a religion of peace . As we explain later, your ‘opinion’ here can be as ‘outrageous’ as you want it to be as long as you are able to back it up with reasonable arguments. Remember, the JLI website clearly declares itself to be, ‘ not a safe space, but a courteous one ’.

How competitive is the JLI Essay Competition?

In 2021, the competition received 4000 entries from 101 countries. Given that there is only one prize winner from each category, this makes this a very competitive opportunity. However, because categories have a different number of applicants, some categories are more competitive than others. One strategy to win could be to focus on fields with fewer submissions like Theology.

There are also a relatively significant number of students who receive commendations called “high commendation.” In the psychology field, for example, about 80 students received a commendation in 2022. At the same time, keep in mind that the number of students shortlisted and invited to Oxford for an academic conference is fairly high and varies by subject. For instance, Theology had around 50 people shortlisted in 2021 whereas Economics had 238 . We, at Lumiere, estimate that approximately 10% of entries of each category make it to the shortlisting stage.

How will your essay be judged?

The essays will be judged on your understanding of the discipline, quality of argumentation and evidence, and writing style. Let’s look at excerpts from various winning essays to see what this looks like in practice.

Level of knowledge and understanding of the relevant material: Differentiating your essay from casual musing requires you to demonstrate knowledge of your discipline. One way to do that is by establishing familiarity with relevant literature and integrating it well into their essay. The winning essay of the 2020 Psychology Prize is a good example of how to do this: “People not only interpret facts in a self-serving way when it comes to their health and well-being; research also demonstrates that we engage in motivated reasoning if the facts challenge our personal beliefs, and essentially, our moral valuation and present understanding of the world. For example, Ditto and Liu showed a link between people’s assessment of facts and their moral convictions” By talking about motivated reasoning in the broader literature, the author can show they are well-versed in the important developments in the field.

Competent use of evidence: In your essay, there are different ways to use evidence effectively. One such way involves backing your argument with results from previous studies . The 2020 Third Place essay in economics shows us what this looks like in practice: “Moreover, this can even be extended to PTSD, where an investigation carried out by Italian doctor G. P. Fichera, led to the conclusion that 13% of the sampling units were likely to have this condition. Initiating economic analysis here, this illustrates that the cost of embarking on this unlawful activity, given the monumental repercussions if caught, is not equal to the costs to society...” The study by G.P. Fichera is used to strengthen the author’s claim on the social costs of crime and give it more weight.

Structure, writing style, and persuasive force: A good argument that is persuasive rarely involves merely backing your claim with good evidence and reasoning. Delivering it in an impactful way is also very important. Let’s see how the winner of the 2020 Law Prize does this: “Slavery still exists, but now it applies to women and its name in prostitution”, wrote Victor Hugo in Les Misérables. Hugo’s portrayal of Fantine under the archetype of a fallen woman forced into prostitution by the most unfortunate of circumstances cannot be more jarringly different from the empowerment-seeking sex workers seen today, highlighting the wide-ranging nuances associated with commercial sex and its implications on the women in the trade. Yet, would Hugo have supported a law prohibiting the selling of sex for the protection of Fantine’s rights?” The use of Victor Hugo in the first line of the essay gives it a literary flair and enhances the impact of the delivery of the argument. Similarly, the rhetorical question, in the end, adds to the literary dimension of the argument. Weaving literary and argumentative skills in a single essay is commendable and something that the institute also recognizes.

Quality of argumentation: Finally, the quality of your argument depends on capturing the various elements mentioned above seamlessly . The third place in theology (2020) does this elegantly while describing bin-Laden’s faulty and selective use of religious verses to commit violence: “He engages in the decontextualization and truncation of Qur'anic verses to manipulate and convince, which dissociates the fatwas from bonafide Islam. For example, in his 1996 fatwa, he quotes the Sword verse but deliberately omits the aforementioned half of the Ayat that calls for mercy. bin-Laden’s intention is not interpretive veracity, but the indoctrination of his followers.” The author’s claim is that bin-Laden lacks religious integrity and thus should not be taken seriously, especially given the content of his messages. To strengthen his argument, he uses actual incidents to dissect this display of faulty reasoning.

These excerpts are great examples of the kind of work you should keep in mind when writing your own draft.

6 Winning Tips from Lumiere

Focus on your essay structure and flow: If logic and argumentation are your guns in this competition, a smooth flow is your bullet. What does a smooth flow mean? It means that the reader should be able to follow your chain of reasoning with ease. This is especially true for essays that explore abstract themes. Let’s see this in detail with the example of a winning philosophy essay. “However, if society were the moral standard, an individual is subjected to circumstantial moral luck concerning whether the rules of the society are good or evil (e.g., 2019 Geneva vs. 1939 Munich). On the other hand, contracts cannot be the standard because people are ignorant of their being under a moral contractual obligation, when, unlike law, it is impossible to be under a contract without being aware. Thus, given the shortcomings of other alternatives, human virtue is the ideal moral norm.” To establish human virtue as the ideal norm, the author points out limitations in society and contracts, leaving out human virtue as the ideal one. Even if you are not familiar with philosophy, you might still be able to follow the reasoning here. This is a great example of the kind of clarity and logical coherence that you should strive for.

Ground your arguments in a solid theoretical framework : Your essay requires you to have well-developed arguments. However, these arguments need to be grounded in academic theory to give them substance and differentiate them from casual opinions. Let me illustrate this with an example of the essay that won second place in the politics category in 2020. “Normatively, the moral authority of governments can be justified on a purely associative basis: citizens have an inherent obligation to obey the state they were born into. As Dworkin argued, “Political association, like family or friendship and other forms of association more local and intimate, is itself pregnant of obligation” (Dworkin). Similar to a family unit where children owe duties to their parents by virtue of being born into that family regardless of their consent, citizens acquire obligations to obey political authority by virtue of being born into a state.” Here, the author is trying to make a point about the nature of political obligation. However, the core of his argument is not the strength of his own reasoning, but the ability to back his reasoning with prior literature. By quoting Dworkin, he includes important scholars of western political thought to give more weight to his arguments. It also displays thorough research on the part of the author to acquire the necessary intellectual tools to write this paper.

The methodology is more important than the conclusion: The 2020 history winners came to opposite conclusions in their essays on whether a strong state hampers or encourages economic growth. While one of them argued that political strength hinders growth when compared to laissez-faire, the other argues that the state is a prerequisite for economic growth . This reflects JLI’s commitment to your reasoning and substantiation instead of the ultimate opinion. The lesson: Don’t be afraid to be bold! Just make sure you are able to back it up.

Establish your framework well: A paragraph (or two) that is able to succinctly describe your methodology, core arguments, and the reasoning behind them displays academic sophistication. A case in point is the introduction of 2019’s Philosophy winner: “To answer the question, we need to construct a method that measures progress in philosophy. I seek to achieve this by asserting that, in philosophy, a certain degree of falsification is achievable. Utilizing philosophical inquiry and thought experiments, we can rationally assess the logical validity of theories and assign “true” and “false” status to philosophical thoughts. With this in mind, I propose to employ the fourth process of the Popperian model of progress…Utilizing these two conditions, I contend that Aristotelian virtue ethics was progress from Kantian ethics and utilitarianism.” Having a framework like this early on gives you a blueprint for what is in the essay and makes it easier for the reader to follow the reasoning. It also helps you as a writer since distilling down your core argument into a paragraph ensures that the first principles of your essay are well established.

Read essays of previous winners: Do this and you will start seeing some patterns in the winning essays. In economics, this might be the ability to present a multidimensional argument and substantiating it with data-backed research. In theology, this might be your critical analysis of religious texts .

Find a mentor: Philosophical logic and argumentation are rarely taught at the high school level. Guidance from an external mentor can fill this academic void by pointing out logical inconsistencies in your arguments and giving critical feedback on your essay. Another important benefit of having a mentor is that it will help you in understanding the heavy literature that is often a key part of the writing/research process in this competition. As we have already seen above, having a strong theoretical framework is crucial in this competition. A mentor can make this process smoother.

Lumiere Research Scholar Program

If you’re looking for a mentor to do an essay contest like John Locke or want to build your own independent research paper, then consider applying to the Lumiere Research Scholar Program . Last year over 2100 students applied for about 500 spots in the program. You can find the application form here.

You can see our admission results here for our students.

Manas is a publication strategy associate at Lumiere Education. He studied public policy and interactive media at NYU and has experience in education consulting.

Jesus loves you!

Feeling overwhelmed with academic demands? Don't worry, I've got you covered! I just found a website that provides assistance with research papers. From topic https://www.phdresearchproposal.org/ selection to formatting, they offer comprehensive support throughout the writing process. Say goodbye to academic stress!

Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, historic document, an essay concerning human understanding (1690).

John Locke | 1690

John Locke (1632-1704) was the author of A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689), An Essay concerning Human Understanding (1690), Two Treatises on Government (1690), and other works. Prior to the American Revolution, Locke was best known in America for his epistemological work. Contrary to the Cartesian view of innate ideas, Locke claimed that the human mind is a tabula rasa and that knowledge is accessible to us through sense perception and experience. Of the significance of Locke’s contribution to the theory of knowledge, James Madison compared him to Sir Isaac Newton’s discoveries in natural science: Both established “immortal systems, the one [Newton] in matter, the other [Locke] in mind” ("Spirit of Governments," 1791).

Selected by

Professor of History and Charles O. Lee and Louise K. Lee Chair in the Western Heritage at Hillsdale College

Jeffrey Rosen

President and CEO, National Constitution Center

Colleen A. Sheehan

Professor of Politics at the Arizona State University School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership

CHAP. II.: No Innate Principles in the Mind.

The way shewn how we come by any knowledge, sufficient to prove it not innate.

§ 1. It is an established opinion amongst some men, that there are in the understanding certain innate principles; some primary notions, ϰοιναὶ ἔννοιαι, characters, as it were, stamped upon the mind of man, which the soul receives in its very first being; and brings into the world with it. It would be sufficient to convince unprejudiced readers of the falseness of this supposition, if I should only shew (as I hope I shall in the following parts of this discourse) how men, barely by the use of their natural faculties, may attain to all the knowledge they have, without the help of any innate impressions; and may arrive at certainty, without any such original notions or principles. For I imagine any one will easily grant, that it would be impertinent to suppose, the ideas of colours innate in a creature, to whom God hath given sight, and a power to receive them by the eyes, from external objects: and no less unreasonable would it be to attribute several truths to the impressions of nature, and innate characters, when we may observe in ourselves faculties, fit to attain as easy and certain knowledge of them, as if they were originally imprinted on the mind. . . .

CHAP. I: Of Idea in general, and their Original.

§ 2. Let us then suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper, void of all characters, without any ideas: —How comes it to be furnished? Whence comes it by that vast store which the busy and boundless fancy of man has painted on it with an almost endless variety? Whence has it all the materials of reason and knowledge? To this I answer, in one word, from EXPERIENCE. In that all our knowledge is founded, and from that it ultimately derives itself. Our observation employed either, about external sensible objects, or about the internal operations of our minds perceived and reflected on by ourselves, is that which supplies our understandings with all the materials of thinking. These two are the fountains of knowledge, from whence all the ideas we have, do spring. . . .

CHAP. XI.: Of Discerning, and other Operations of the Mind.

§ 17. I pretend not to teach, but to inquire, and therefore cannot but confess here again, that external and internal sensation are the only passages that I can find of knowledge to the understanding. These alone, as far as I can discover, are the windows by which light is let into this dark room: for methinks the understanding is not much unlike a closet wholly shut from light, with only some little opening left, to let in external visible resemblances, or ideas of things without: would the pictures coming into such a dark room but stay there, and lie so orderly as to be found upon occasion, it would very much resemble the understanding of a man, in reference to all objects of sight, and the ideas of them. . . .

CHAP. XXI.: Of Power.

§ 51. As therefore the highest perfection of intellectual nature lies in a careful and constant pursuit of true and solid happiness, so the care of ourselves, that we mistake not imaginary for real happiness, is the necessary foundation of our liberty. The stronger ties we have to an unalterable pursuit of happiness in general, which is our greatest good, and which, as such, our desires always follow, the more are we free from any necessary determination of our will to any particular action, and from a necessary compliance with our desire, set upon any particular, and then appearing preferable good, till we have duly examined, whether it has a tendency to, or be inconsistent with our real happiness: and therefore till we are as much informed upon this inquiry, as the weight of the matter, and the nature of the case demands; we are, by the necessity of preferring and pursuing true happiness as our greatest good, obliged to suspend the satisfaction of our desires in particular cases.

§ 52. This is the hinge on which turns the liberty of intellectual beings, in their constant endeavours after and a steady prosecution of true felicity, that they can suspend this prosecution in particular cases, till they have looked before them, and informed themselves whether that particular thing, which is then proposed or desired, lie in the way to their main end, and make a real part of that which is their greatest good: for the inclination and tendency of their nature to happiness is an obligation and motive to them, to take care not to mistake or miss it; and so necessarily puts them upon caution, deliberation, and wariness, in the direction of their particular actions, which are the means to obtain it. Whatever necessity determines to the pursuit of real bliss, the same necessity with the same force establishes suspense, deliberation, and scrutiny of each successive desire, whether the satisfaction of it does not interfere with our true happiness, and mislead us from it. This, as seems to me, is the great privilege of finite intellectual beings; and I desire it may be well considered, whether the great inlet and exercise of all the liberty men have, are capable of, or can be useful to them, and that whereon depends the turn of their actions, does not lie in this, that they can suspend their desires, and stop them from determining their wills to any action, till they have duly and fairly examined the good and evil of it, as far forth as the weight of the thing requires.

§ 2. . . . Sense and intuition reach but a very little way. The greatest part of our knowledge depends upon deductions and intermediate ideas: and in those cases, where we are fain to substitute assent instead of knowledge, and take propositions for true, without being certain they are so, we have need to find out, examine, and compare the grounds of their probability. In both these cases, the faculty which finds out the means, and rightly applies them to discover certainty in the one, and probability in the other, is that which we call reason. For as reason perceives the necessary and indubitable connexion of all the ideas or proofs one to another, in each step of any demonstration that produces knowledge: so it likewise perceives the probable connexion of all the ideas or proofs one to another, in every step of a discourse, to which it will think assent due. This is the lowest degree of that which can be truly called reason. . . .

§ 23. By what has been before said of reason, we may be able to make some guess at the distinction of things, into those that are according to, above, and contrary to reason. 1. According to reason are such propositions, whose truth we can discover by examining and tracing those ideas we have from sensation and reflection; and by natural deduction find to be true or probable. 2. Above reason are such propositions, whose truth or probability we cannot by reason derive from those principles. 3. Contrary to reason are such propositions, as are inconsistent with, or irreconcileable to, our clear and distinct ideas. Thus the existence of one God is according to reason; the existence of more than one God, contrary to reason; the resurrection of the dead, above reason. . . .

Explore the full document

Modal title.

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Locke’s Political Philosophy

John Locke (1632–1704) is among the most influential political philosophers of the modern period. In the Two Treatises of Government , he defended the claim that men are by nature free and equal against claims that God had made all people naturally subject to a monarch. He argued that people have rights, such as the right to life, liberty, and property, that have a foundation independent of the laws of any particular society. Locke used the claim that men are naturally free and equal as part of the justification for understanding legitimate political government as the result of a social contract where people in the state of nature conditionally transfer some of their rights to the government in order to better ensure the stable, comfortable enjoyment of their lives, liberty, and property. Since governments exist by the consent of the people in order to protect the rights of the people and promote the public good, governments that fail to do so can be resisted and replaced with new governments. Locke is thus also important for his defense of the right of revolution. Locke also defends the principle of majority rule and the separation of legislative and executive powers. In the Letter Concerning Toleration , Locke denied that coercion should be used to bring people to (what the ruler believes is) the true religion and also denied that churches should have any coercive power over their members. Locke elaborated on these themes in his later political writings, such as the Second Letter on Toleration and Third Letter on Toleration .

For a more general introduction to Locke’s history and background, the argument of the Two Treatises , and the Letter Concerning Toleration , see Section 1 , Section 4 , and Section 5 , respectively, of the main entry on John Locke in this encyclopedia. The present entry focuses on eight central concepts in Locke’s political philosophy.

1. Natural Law and Natural Rights

2. state of nature, 3. property, 4. consent, political obligation, and the ends of government, 5. locke and punishment, 6. separation of powers and the dissolution of government, 7. toleration, 8. education and politics, select primary sources, select secondary sources, other internet resources, related entries.

Perhaps the most central concept in Locke’s political philosophy is his theory of natural law and natural rights. The natural law concept existed long before Locke as a way of expressing the idea that there were certain moral truths that applied to all people, regardless of the particular place where they lived or the agreements they had made. The most important early contrast was between laws that were by nature, and thus generally applicable, and those that were conventional and operated only in those places where the particular convention had been established. This distinction is sometimes formulated as the difference between natural law and positive law.

Natural law is also distinct from divine law in that the latter, in the Christian tradition, normally referred to those laws that God had directly revealed through prophets and other inspired writers. Natural law can be discovered by reason alone and applies to all people, while divine law can be discovered only through God’s special revelation and applies only to those to whom it is revealed and whom God specifically indicates are to be bound. Thus some seventeenth-century commentators, Locke included, held that not all of the 10 commandments, much less the rest of the Old Testament law, were binding on all people. The 10 commandments begin “Hear O Israel” and thus are only binding on the people to whom they were addressed ( Works 6:37). (Spelling and formatting are modernized in quotations from Locke in this entry). As we will see below, even though Locke thought natural law could be known apart from special revelation, he saw no contradiction in God playing a part in the argument, so long as the relevant aspects of God’s character could be discovered by reason alone. In Locke’s theory, divine law and natural law are consistent and can overlap in content, but they are not coextensive. Thus there is no problem for Locke if the Bible commands a moral code that is stricter than the one that can be derived from natural law, but there is a real problem if the Bible teaches what is contrary to natural law. In practice, Locke avoided this problem because consistency with natural law was one of the criteria he used when deciding the proper interpretation of Biblical passages.

The language of natural rights also gained prominence through the writings of thinkers in the generation before Locke, such as Grotius and Hobbes, and of his contemporary Pufendorf. Whereas natural law emphasized duties, natural rights normally emphasized privileges or claims to which an individual was entitled. There is considerable disagreement as to how these factors are to be understood in relation to each other in Locke’s theory. Leo Strauss (1953), and many of his followers, take rights to be paramount, going so far as to portray Locke’s position as essentially similar to that of Hobbes. They point out that Locke defended a hedonist theory of human motivation ( Essay 2.20) and claim that he must agree with Hobbes about the essentially self-interested nature of human beings. Locke, they claim, recognizes natural law obligations only in those situations where our own preservation is not in conflict, further emphasizing that our right to preserve ourselves trumps any duties we may have.

On the other end of the spectrum, more scholars have adopted the view of Dunn (1969), Tully (1980), and Ashcraft (1986) that it is natural law, not natural rights, that is primary. They hold that when Locke emphasized the right to life, liberty, and property he was primarily making a point about the duties we have toward other people: duties not to kill, enslave, or steal. Most scholars also argue that Locke recognized a general duty to assist with the preservation of mankind, including a duty of charity to those who have no other way to procure their subsistence ( Two Treatises 1.42). These scholars regard duties as primary in Locke because rights exist to ensure that we are able to fulfill our duties. Simmons (1992) takes a position similar to the latter group, but claims that rights are not just the flip side of duties in Locke, nor merely a means to performing our duties. Instead, rights and duties are equally fundamental because Locke believes in a “robust zone of indifference” in which rights protect our ability to make choices. While these choices cannot violate natural law, they are not a mere means to fulfilling natural law either. Brian Tierney (2014) questions whether one needs to prioritize natural law or natural right since both typically function as corollaries. He argues that modern natural rights theories are a development from medieval conceptions of natural law that included permissions to act or not act in certain ways.

There have been some attempts to find a compromise between these positions. Michael Zuckert’s (1994) version of the Straussian position acknowledges more differences between Hobbes and Locke. Zuckert still questions the sincerity of Locke’s theism, but thinks that Locke does develop a position that grounds property rights in the fact that human beings own themselves, something Hobbes denied. Adam Seagrave (2014) has gone a step further. He argues that the contradiction between Locke’s claim that human beings are owned by God and that human beings own themselves is only apparent. He bases this argument on passages from Locke’s other writings (especially the Essay Concerning Human Understanding ). In the passages about divine ownership, Locke is speaking about humanity as a whole, while in the passages about self-ownership he is talking about individual human beings with the capacity for property ownership. God created human beings who are capable of having property rights with respect to one another on the basis of owning their labor. Both of them emphasize differences between Locke’s use of natural rights and the earlier tradition of natural law.

Another point of contestation has to do with the extent to which Locke thought natural law could, in fact, be known by reason. Both Strauss (1953) and Peter Laslett (Introduction to Locke’s Two Treatises ), though very different in their interpretations of Locke generally, see Locke’s theory of natural law as filled with contradictions. In the Essay Concerning Human Understanding , Locke defends a theory of moral knowledge that negates the possibility of innate ideas ( Essay Book 1) and claims that morality is capable of demonstration in the same way that Mathematics is ( Essay 3.11.16, 4.3.18–20). Yet nowhere in any of his works does Locke make a full deduction of natural law from first premises. More than that, Locke at times seems to appeal to innate ideas in the Second Treatise (2.11), and in The Reasonableness of Christianity ( Works 7:139) he admits that no one has ever worked out all of natural law from reason alone. Strauss infers from this that the contradictions exist to show the attentive reader that Locke does not really believe in natural law at all. Laslett, more conservatively, simply says that Locke the philosopher and Locke the political writer should be kept very separate.

Many scholars reject this position. Yolton (1958), Colman (1883), Ashcraft (1987), Grant (1987), Simmons (1992), Tuckness (1999), Israelson (2013), Rossiter (2016), Connolly (2019), and others all argue that there is nothing strictly inconsistent in Locke’s admission in The Reasonableness of Christianity . That no one has deduced all of natural law from first principles does not mean that none of it has been deduced. The supposedly contradictory passages in the Two Treatises are far from decisive. While it is true that Locke does not provide a deduction in the Essay , it is not clear that he was trying to. Section 4.10.1–19 of that work seems more concerned to show how reasoning with moral terms is possible, not to actually provide a full account of natural law. Nonetheless, it must be admitted that Locke did not treat the topic of natural law as systematically as one might like. Attempts to work out his theory in more detail with respect to its ground and its content must try to reconstruct it from scattered passages in many different texts.

To understand Locke’s position on the ground of natural law it must be situated within a larger debate in natural law theory that predates Locke, the so-called “voluntarism-intellectualism,” or “voluntarist-rationalist” debate. At its simplest, the voluntarist declares that right and wrong are determined by God’s will and that we are obliged to obey the will of God simply because it is the will of God. Unless these positions are maintained, the voluntarist argues, God becomes superfluous to morality since both the content and the binding force of morality can be explained without reference to God. The intellectualist replies that this understanding makes morality arbitrary and fails to explain why we have an obligation to obey God. Graedon Zorzi (2019) has argued that “person” is a relational term for Locke, indicating that we will be held accountable by God for whether we have followed the law.

With respect to the grounds and content of natural law, Locke is not completely clear. On the one hand, there are many instances where he makes statements that sound voluntarist to the effect that law requires a legislator with authority ( Essay 1.3.6, 4.10.7). Locke also repeatedly insists in the Essays on the Law of Nature that created beings have an obligation to obey their creator ( Political Essays 116–120). On the other hand there are statements that seem to imply an external moral standard to which God must conform ( Two Treatises 2.195; Works 7:6). Locke clearly wants to avoid the implication that the content of natural law is arbitrary. Several solutions have been proposed. One solution suggested by Herzog (1985) makes Locke an intellectualist by grounding our obligation to obey God on a prior duty of gratitude that exists independent of God. A second option, suggested by Simmons (1992), is simply to take Locke as a voluntarist since that is where the preponderance of his statements point. A third option, suggested by Tuckness (1999) (and implied by Grant 1987 and affirmed by Israelson 2013), is to treat the question of voluntarism as having two different parts, grounds and content. On this view, Locke was indeed a voluntarist with respect to the question “why should we obey the law of nature?” Locke thought that reason, apart from the will of a superior, could only be advisory. With respect to content, divine reason and human reason must be sufficiently analogous that human beings can reason about what God likely wills. Locke takes it for granted that since God created us with reason in order to follow God’s will, human reason and divine reason are sufficiently similar that natural law will not seem arbitrary to us.

Those interested in the contemporary relevance of Locke’s political theory must confront its theological aspects. Straussians make Locke’s theory relevant by claiming that the theological dimensions of his thought are primarily rhetorical; they were “cover” to keep him from being persecuted by the religious authorities of his day. Others, such as Dunn (1969) and Stanton (2018), take Locke to be of only limited relevance to contemporary politics precisely because so many of his arguments depend on religious assumptions that are no longer widely shared. Some authors, such as Simmons (1992) and Vernon (1997), have tried to separate the foundations of Locke’s argument from other aspects of it. Simmons, for example, argues that Locke’s thought is over-determined, containing both religious and secular arguments. He claims that for Locke the fundamental law of nature is that “as much as possible mankind is to be preserved” ( Two Treatises 2.135). At times, he claims, Locke presents this principle in rule-consequentialist terms: it is the principle we use to determine the more specific rights and duties that all have. At other times, Locke hints at a more Kantian justification that emphasizes the impropriety of treating our equals as if they were mere means to our ends. Waldron (2002) explores the opposite claim: that Locke’s theology actually provides a more solid basis for his premise of political equality than do contemporary secular approaches that tend to simply assert equality.

With respect to the specific content of natural law, Locke never provides a comprehensive statement of what it requires. In the Two Treatises , Locke frequently states that the fundamental law of nature is that as much as possible mankind is to be preserved. Simmons (1992) argues that in Two Treatises 2.6 Locke presents (1) a duty to preserve one’s self, (2) a duty to preserve others when self-preservation does not conflict, (3) a duty not to take away the life of another, and (4) a duty not to act in a way that “tends to destroy” others. Libertarian interpreters of Locke tend to downplay duties of type 1 and 2. Locke presents a more extensive list in his earlier, and unpublished in his lifetime, Essays on the Law of Nature . Interestingly, Locke here includes praise and honor of the deity as required by natural law as well as what we might call good character qualities.

Locke’s concept of the state of nature has been interpreted by commentators in a variety of ways. At first glance it seems quite simple. Locke writes “want [lack] of a common judge, with authority, puts all men in a state of nature” and again, “Men living together according to reason, without a common superior on earth, with authority to judge between them, is properly the state of nature.” ( Two Treatises 2.19) Many commentators have taken this as Locke’s definition, concluding that the state of nature exists wherever there is no legitimate political authority able to judge disputes and where people live according to the law of reason. On this account the state of nature is distinct from political society, where a legitimate government exists, and from a state of war where men fail to abide by the law of reason.

Simmons (1993) presents an important challenge to this view. Simmons points out that the above statement is worded as a sufficient rather than necessary condition. Two individuals might be able, in the state of nature, to authorize a third to settle disputes between them without leaving the state of nature, since the third party would not have, for example, the power to legislate for the public good. Simmons also claims that other interpretations often fail to account for the fact that there are some people who live in states with legitimate governments who are nonetheless in the state of nature: visiting aliens ( Two Treatises 2.9), children below the age of majority (2.15, 118), and those with a “defect” of reason (2.60). He claims that the state of nature is a relational concept describing a particular set of moral relations that exist between particular people, rather than a description of a particular geographical territory where there is no government with effective control. The state of nature is just the way of describing the moral rights and responsibilities that exist between people who have not consented to the adjudication of their disputes by the same legitimate government. The groups just mentioned either have not or cannot give consent, so they remain in the state of nature. Thus A may be in the state of nature with respect to B, but not with C.

Simmons’ account stands in sharp contrast to that of Strauss (1953). According to Strauss, Locke presents the state of nature as a factual description of what the earliest society is like, an account that when read closely reveals Locke’s departure from Christian teachings. State of nature theories, he and his followers argue, are contrary to the Biblical account in Genesis and evidence that Locke’s teaching is similar to that of Hobbes. As noted above, on the Straussian account Locke’s apparently Christian statements are only a façade designed to conceal his essentially anti-Christian views. According to Simmons, since the state of nature is a moral account, it is compatible with a wide variety of social accounts without contradiction. If we know only that a group of people are in a state of nature, we know only the rights and responsibilities they have toward one another; we know nothing about whether they are rich or poor, peaceful or warlike.

A complementary interpretation is made by John Dunn (1969) with respect to the relationship between Locke’s state of nature and his Christian beliefs. Dunn claimed that Locke’s state of nature is less an exercise in historical anthropology than a theological reflection on the condition of man. On Dunn’s interpretation, Locke’s state of nature thinking is an expression of his theological position, that man exists in a world created by God for God’s purposes but that governments are created by men in order to further those purposes.

Locke’s theory of the state of nature will thus be tied closely to his theory of natural law, since the latter defines the rights of persons and their status as free and equal persons. The stronger the grounds for accepting Locke’s characterization of people as free, equal, and independent, the more helpful the state of nature becomes as a device for representing people. Still, it is important to remember that none of these interpretations claims that Locke’s state of nature is only a thought experiment, in the way Kant and Rawls are normally thought to use the concept. Locke did not respond to the argument “where have there ever been people in such a state” by saying it did not matter since it was only a thought experiment. Instead, he argued that there are and have been people in the state of nature ( Two Treatises 2.14). It seems important to him that at least some governments have actually been formed in the way he suggests. How much it matters whether they have been or not will be discussed below under the topic of consent, since the central question is whether a good government can be legitimate even if it does not have the actual consent of the people who live under it; hypothetical contract and actual contract theories will tend to answer this question differently.

Locke’s treatment of property is generally thought to be among his most important contributions in political thought, but it is also one of the aspects of his thought that has been most heavily criticized. There are important debates over what exactly Locke was trying to accomplish with his theory. One interpretation, advanced by C.B. Macpherson (1962), sees Locke as a defender of unrestricted capitalist accumulation. On Macpherson’s interpretation, Locke is thought to have set three restrictions on the accumulation of property in the state of nature: (1) one may only appropriate as much as one can use before it spoils ( Two Treatises 2.31), (2) one must leave “enough and as good” for others (the sufficiency restriction) (2.27), and (3) one may (supposedly) only appropriate property through one’s own labor (2.27). Macpherson claims that as the argument progresses, each of these restrictions is transcended. The spoilage restriction ceases to be a meaningful restriction with the invention of money because value can be stored in a medium that does not decay (2.46–47). The sufficiency restriction is transcended because the creation of private property so increases productivity that even those who no longer have the opportunity to acquire land will have more opportunity to acquire what is necessary for life (2.37). According to Macpherson’s view, the “enough and as good” requirement is itself merely a derivative of a prior principle guaranteeing the opportunity to acquire, through labor, the necessities of life. The third restriction, Macpherson argues, was not one Locke actually held at all. Though Locke appears to suggest that one can only have property in what one has personally labored on when he makes labor the source of property rights, Locke clearly recognized that even in the state of nature, “the Turfs my Servant has cut” (2.28) can become my property. Locke, according to Macpherson, thus clearly recognized that labor can be alienated. As one would guess, Macpherson is critical of the “possessive individualism” that Locke’s theory of property represents. He argues that its coherence depends upon the assumption of differential rationality between capitalists and wage-laborers and on the division of society into distinct classes. Because Locke was bound by these constraints, we are to understand him as including only property owners as voting members of society.

Macpherson’s understanding of Locke has been criticized from several different directions. Alan Ryan (1965) argued that since property for Locke includes life and liberty as well as estate ( Two Treatises 2.87), even those without land could still be members of political society. The dispute between the two would then turn on whether Locke was using “property” in the more expansive sense in some of the crucial passages. James Tully (1980) attacked Macpherson’s interpretation by pointing out that the First Treatise specifically includes a duty of charity toward those who have no other means of subsistence (1.42). While this duty is consistent with requiring the poor to work for low wages, it does undermine the claim that those who have wealth have no social duties to others.

Tully also argued for a fundamental reinterpretation of Locke’s theory. Previous accounts had focused on the claim that since persons own their own labor, when they mix their labor with that which is unowned it becomes their property. Robert Nozick (1974) criticized this argument with his famous example of mixing tomato juice one rightfully owns with the sea. When we mix what we own with what we do not, why should we think we gain property instead of losing it? On Tully’s account, focus on the mixing metaphor misses Locke’s emphasis on what he calls the “workmanship model.” Locke believed that makers have property rights with respect to what they make just as God has property rights with respect to human beings because he is their maker. Human beings are created in the image of God and share with God, though to a much lesser extent, the ability to shape and mold the physical environment in accordance with a rational pattern or plan. Waldron (1988) has criticized this interpretation on the grounds that it would make the rights of human makers absolute in the same way that God’s right over his creation is absolute. Sreenivasan (1995) has defended Tully’s argument against Waldron’s response by claiming a distinction between creating and making. Only creating generates an absolute property right, and only God can create, but making is analogous to creating and creates an analogous, though weaker, right.

Another controversial aspect of Tully’s interpretation of Locke is his interpretation of the sufficiency condition and its implications. On his analysis, the sufficiency argument is crucial for Locke’s argument to be plausible. Since Locke begins with the assumption that the world is owned by all, individual property is only justified if it can be shown that no one is made worse off by the appropriation. In conditions where the good taken is not scarce, where there is much water or land available, an individual’s taking some portion of it does no harm to others. Where this condition is not met, those who are denied access to the good do have a legitimate objection to appropriation. According to Tully, Locke realized that as soon as land became scarce, previous rights acquired by labor no longer held since “enough and as good” was no longer available for others. Once land became scarce, property could only be legitimated by the creation of political society.

Waldron (1988) claims that, contrary to Macpherson (1962), Tully (1980), and others, Locke did not recognize a sufficiency condition at all. He notes that, strictly speaking, Locke makes sufficiency a sufficient rather than necessary condition when he says that labor generates a title to property “at least where there is enough, and as good left in common for others” ( Two Treatises 2.27). Waldron takes Locke to be making a descriptive statement, not a normative one, about the conditions that initially existed. Waldron also argues that in the text “enough and as good” is not presented as a restriction and is not grouped with other restrictions. Waldron thinks that the condition would lead Locke to the absurd conclusion that in circumstances of scarcity everyone must starve to death since no one would be able to obtain universal consent and any appropriation would make others worse off.

One of the strongest defenses of Tully’s position is presented by Sreenivasan (1995). He argues that Locke’s repetitious use of “enough and as good” indicates that the phrase is doing some real work in the argument. In particular, it is the only way Locke can be thought to have provided some solution to the fact that the consent of all is needed to justify appropriation in the state of nature. If others are not harmed, they have no grounds to object and can be thought to consent, whereas if they are harmed, it is implausible to think of them as consenting. Sreenivasan does depart from Tully in some important respects. He takes “enough and as good” to mean “enough and as good opportunity for securing one’s preservation,” not “enough and as good of the same commodity (such as land).” This has the advantage of making Locke’s account of property less radical since it does not claim that Locke thought the point of his theory was to show that all original property rights were invalid at the point where political communities were created. The disadvantage of this interpretation, as Sreenivasan admits, is that it saddles Locke with a flawed argument. Those who merely have the opportunity to labor for others at subsistence wages no longer have the liberty that individuals had before scarcity to benefit from the full surplus of value they create. Moreover, poor laborers no longer enjoy equality of access to the materials from which products can be made. Sreenivasan thinks that Locke’s theory is thus unable to solve the problem of how individuals can obtain individual property rights in what is initially owned by all people without consent.

Simmons (1992) presents a still different synthesis. He sides with Waldron (1988) and against Tully (1980) and Sreenivasan (1995) in rejecting the workmanship model. He claims that the references to “making” in chapter five of the Two Treatises are not making in the right sense of the word for the workmanship model to be correct. Locke thinks we have property in our own persons even though we do not make or create ourselves. Simmons claims that while Locke did believe that God had rights as creator, human beings have a different limited right as trustees , not as makers. Simmons bases this in part on his reading of two distinct arguments he takes Locke to make: the first justifies property based on God’s will and basic human needs, the second based on “mixing” labor. According to the former argument, at least some property rights can be justified by showing that a scheme allowing appropriation of property without consent has beneficial consequences for the preservation of mankind. This argument is overdetermined, according to Simmons, in that it can be interpreted either theologically or as a simple rule-consequentialist argument. With respect to the latter argument, Simmons takes labor not to be a substance that is literally “mixed” but rather as a purposive activity aimed at satisfying needs and conveniences of life. Like Sreenivasan, Simmons sees this as flowing from a prior right of people to secure their subsistence, but Simmons also adds a prior right to self-government. Labor can generate claims to private property because private property makes individuals more independent and able to direct their own actions. Simmons thinks Locke’s argument is ultimately flawed because he underestimated the extent to which wage labor would make the poor dependent on the rich, undermining self-government. He also joins the chorus of those who find Locke’s appeal to consent to the introduction of money inadequate to justify the very unequal property holdings that now exist.

Some authors have suggested that Locke may have had an additional concern in mind in writing the chapter on property. Tully (1993) and Barbara Arneil (1996) point out that Locke was interested in and involved in the affairs of the American colonies and that Locke’s theory of labor led to the convenient conclusion that the labor of Native Americans generated property rights only over the animals they caught, not the land on which they hunted which Locke regarded as vacant and available for the taking. David Armitage (2004) even argues that there is evidence that Locke was actively involved in revising the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina at the same time he was drafting the chapter on property for the Second Treatise . Mark Goldie (1983), however, cautions that we should not miss the fact that political events in England were still Locke’s primary focus in writing the Second Treatise .

A final question concerns the status of those property rights acquired in the state of nature after civil society has come into being. It seems clear that at the very least Locke allows taxation to take place by the consent of the majority rather than requiring unanimous consent (2.140). Nozick (1974) takes Locke to be a libertarian, with the government having no right to take property to use for the common good without the consent of the property owner. On his interpretation, the majority may only tax at the rate needed to allow the government to successfully protect property rights. At the other extreme, Tully (1980) thinks that, by the time government is formed, land is already scarce and so the initial holdings of the state of nature are no longer valid and thus are no constraint on governmental action. Waldron’s (1988) view is in between these, acknowledging that property rights are among the rights from the state of nature that continue to constrain the government, but seeing the legislature as having the power to interpret what natural law requires in this matter in a fairly substantial way.

The most direct reading of Locke’s political philosophy finds the concept of consent playing a central role. His analysis begins with individuals in a state of nature where they are not subject to a common legitimate authority with the power to legislate or adjudicate disputes. From this natural state of freedom and independence, Locke stresses individual consent as the mechanism by which political societies are created and individuals join those societies. While there are of course some general obligations and rights that all people have from the law of nature, special obligations come about only when we voluntarily undertake them. Locke clearly states that one can only become a full member of society by an act of express consent ( Two Treatises 2.122). The literature on Locke’s theory of consent tends to focus on how Locke does or does not successfully answer the following objection: few people have actually consented to their governments so no, or almost no, governments are actually legitimate. This conclusion is problematic since it is clearly contrary to Locke’s intention.