Slavery, Abolition, Emancipation and Freedom

- Explore the Collection

- Collections in Context

- Teaching the Collection

- Advanced Collection Research

Reconstruction, 1865-1877

Donald Brown, Harvard University, G6, English PhD Candidate

No period in American history has had more wide-reaching implications than Reconstruction. However, white supremacist mythologies about those contentious years from 1865-1877 reigned supreme both inside and outside the academy until the 1960s. Columbia University’s now-infamous Dunning School (1900-1930) epitomizes the dominant narrative regarding Reconstruction for over half of the twentieth century. From their point of view, Reconstruction was a tragic period of American history in which vengeful White Northern radicals took over the South. In order to punish the White Southerners they had just defeated in the Civil War, these Radical Republicans gave ignorant freedmen the right to vote. This resulted in at least 2,000 elected Black officeholders, including two United States senators and 21 representatives. In order to discredit the sweeping changes taking place across the American South, conservative historians argued this period was full of corruption and disorder and proved that Black Americans were not fit to leadership or citizenship.

Thanks to the work of a number of Black and leftist historians—most notably John Roy Lynch, W.E.B. Du Bois, Willie Lee Rose, and Eric Foner—that negative depiction of Reconstruction is being overturned. As Du Bois famously wrote in Black Reconstruction in America (1935), this was a time in which “the slave went free; stood for a brief moment in the sun; and then moved back again toward slavery.” During that short time in the sun, underfunded biracial state governments taxed big planters to pay for education, healthcare, and roads that benefited everyone. There is still much more to be unpacked from this rich period of American history, and Houghton Library contains a wealth of material to further buttress new narratives of that era.

Reconstructing Reconstruction

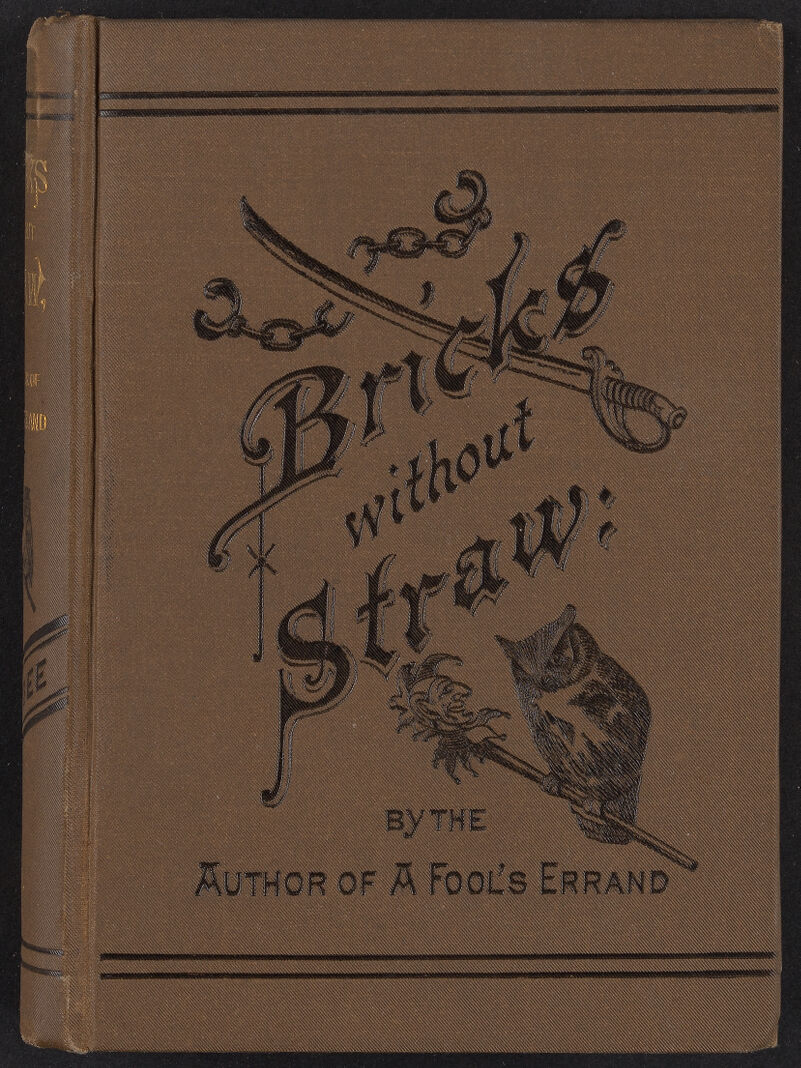

While some academics, like those of the Dunning School, interpreted Reconstruction as doomed to failure, in the years immediately following the Civil War there were many Americans, Black and White, who saw the radical reforms as being sabotaged from the outset. Writer and civil rights activist Albion W. Tourgée published his best selling novel Bricks Without Straw in 1880. Unlike most White authors at the time, Tourgée centered Black characters in his novel, showing how the recently emancipated were faced with violence and political oppression in spite of their attempts to be equal citizens.

In this period, two of the most iconic amendments were implemented. The Fourteenth Amendment ratified several crucial civil rights clauses. The natural born citizenship clause overturned the 1857 supreme court case, Dred Scott v. Sandford , which stated that descendants of African slaves could not be citizens of the United States. The equal protection clause ensured formerly enslaved persons crucial legal rights and validated the equality provisions contained in the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Even though many of these clauses were cleverly disregarded by numerous states once Reconstruction ended, particularly in the Deep South, the equal protection clause was the basis of the NAACP’s victory in the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). The Fifteenth Amendment guaranteed another important civil right: the right to vote. No longer could any state discriminate on the basis of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. At Houghton, we have proof of the exhilarating response Black Americans had to the momentous progress they worked so hard to bring about: Nashvillians organized a Fifteenth Amendment Celebration on May 4, 1870. And once again, during the classical period of the Civil Rights Movement, leaders appealed to this amendment to make their case for what became the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The Reign of Kings Alpha and Abadon

Lorenzo D. Blackson's fantastical allegory novel, The Rise and Progress of the Kingdoms of Light & Darkness ; Reign of Kings Alpha and Abadon (1867), is one of the most ambitious creative efforts of Black authors during Reconstruction. A Protestant religious allegory in the lineage of John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress , Blackson's novel follows his vision of a holy war between good and evil, showing slavery and racial oppression on the side of evil King Abadon and Protestant abolitionists and freemen on the side of good King Alpha. The combination of fantasy holy war, religious pedagogy, and Reconstruction era optimism provide a unique insight to one contemporary Black perspective on the time.

It is important to emphasize that these radical policy initiatives were set by Black Americans themselves. It was, in fact, from formerly enslaved persons, not those who formerly enslaved them, that the most robust notions of freedom were imagined and enacted. With the help of the nation’s first civil rights president, Ulysses S. Grant (1869-1877), and Radical Republicans, such as Benjamin Franklin Wade and Thaddeus Stevens, substantial strides in racial advancement were made in those short twelve years. Houghton Library is home to a wide array of examples of said advancement, such as a letter written in 1855 by Frederick Douglass to Charles Sumner, the nation’s leading abolitionist. In it, he argues that Black Americans, not White abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison, founded the antislavery movement. That being said, Douglass was appreciative of allies, such as President Grant, of whom he said: “in him the Negro found a protector, the Indian a friend, a vanquished foe a brother, an imperiled nation a savior.” Houghton Library also houses an extraordinary letter dated December 1, 1876 from Sojourner Truth , famous abolitionist and women’s rights activist, who could neither read nor write. She had someone help steady her hand so she could provide a signed letter to a fan, and promised to also send her supporter an autobiography, Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Bondswoman of Olden Time, Emancipated by the New York Legislature in the Early Part of the Present Century: with a History of Her Labors and Correspondence.

In this hopeful time, Black Americans, primarily located in the South, were determined to use their demographic power to demand their right to a portion of the wealth and property their labor had created. In states like South Carolina and Mississippi, which were majority Black at the time, and Louisiana , Alabama, and Georgia , with Black Americans consisting of nearly half of the population, the United States elected its first Black U.S. congressmen. Now that Black Southern men had the power to vote, they eagerly elected Black men to represent their best interests. Jefferson Franklin Long (U.S. congressman from Georgia), Joseph Hayne Rainey (U.S. congressman from South Carolina), and Hiram Rhodes Revels (Mississippi U.S. Senator) all took office in the 41st Congress (1869-1871). These elected officials were memorialized in a lithograph by popular firm Currier and Ives. Other federal agencies, such as the Freedmen’s Bureau , also assisted Black Americans build businesses, churches, and schools; own land and cultivate crops; and more generally establish cultural and economic autonomy. As Frederick Douglass wrote in 1870, “at last, at last the black man has a future.”

Black Americans quickly took full advantage of their newfound freedom in a myriad of ways. Alfred Islay Walden’s story is a particularly remarkable example of this. Born a slave in Randolph County, North Carolina, he only gained freedom after Emancipation. He traveled by foot to Washington, D.C. and made a living selling poems and giving lectures across the Northeast. He also attended school at Howard University on scholarship, graduating in 1876, and used that formal education to establish a mission school and become one of the first Black graduates of New Brunswick Theological Seminary. Walden’s Miscellaneous Poems, Which The Author Desires to Dedicate to The Cause of Education and Humanity (1872) celebrates the “Impeachment of President Johnson,” one of the most racist presidents in American history; “The Election of Mayor Bowen,” a Radical Republican mayor of Washington, D.C. (Sayles Jenks Bowen); and Walden’s own religious convictions, such as in “Jesus my Friend;” among other topics.

Black newspapers quickly emerged during Reconstruction as well, such as the Colored Representative , a Black newspaper based in Lexington, KY in the 1870s. As editor George B. Thomas wrote in an “Extra,” dated May 25, 1871 : “We want all the arts and fashions of the North, East and Western states, for the benefit of the colored people. They cannot know what is going on, unless they read our paper.... Now, we want everything that is a benefit to our colored people. Speeches, debates, and sermons will be published.”

Reconstruction proves that Black people, when not impeded by structural barriers, are enthusiastic civic participants. Houghton houses rich archival material on Black Americans advocating for civil rights in Vicksburg, Mississippi , Little Rock, Arkansas , and Atlanta, Georgia , among other states, in the forms of state Colored Conventions and powerful political speeches . For anyone interested in the long history of the Civil Rights Movement, these holdings are a treasure trove waiting to be mined. Though the moment in the sun was brief, the heat exuded during Reconstruction left a deep impact on progressive Americans and will continue to provide an exemplary political model for generations to come.

- HISTORY & CULTURE

- RACE IN AMERICA

Reconstruction offered a glimpse of equality for Black Americans. Why did it fail?

During the Reconstruction era, the U.S. abolished slavery and guaranteed Black men the right to vote. But it was marred by tragedy and political infighting—and ended with a disastrous backlash.

Members of the first South Carolina legislature after the Civil War. Approximately 2,000 Black men were elected to office during the post-war Reconstruction period, which briefly provided political and social power to formerly enslaved people before a backlash ushered in an era of segregation.

On April 11, 1865, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln spoke to an ecstatic crowd at the White House. In the last speech he ever gave, Lincoln could have waxed poetic about Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s recent surrender and the impending end of America’s bloodiest conflict. Instead, he made a case for stitching the country back together after the Civil War by restoring rebel states to the Union and undoing the evils of slavery.

“Let us all join in doing the acts necessary to restoring the proper practical relations between [Confederate] states and the Union,” Lincoln said. “I believe it is not only possible, but in fact, easier, to do this, without deciding, or even considering, whether these states have even been out of the Union.”

The ensuing period of reform and rebuilding, known as Reconstruction, briefly succeeded in providing Black people with political and social power. But it was marred by tragedy, political infighting, and a disastrous backlash that set the stage for more than a century of segregation and voter suppression.

Lincoln’s vision for Reconstruction

Plans to readmit Confederate states to the Union began long before the war’s end. Lincoln wanted to make it easy for them to return, fearing that too harsh a plan would make reunification impossible.

In December 1863, the Republican president issued a proclamation that offered to reinstate former Confederate states once 10 percent of their voters pledged allegiance to the Union and promised to adhere to the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that the United States would “recognize and maintain” the freedom of all people enslaved in seceded states. Those who took the oath would be pardoned, and states that cleared the bar could draft new constitutions and convene state governments.

President Abraham Lincoln signs the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, declaring that all enslaved people within the rebel states would be freed. It would take another two years to abolish slavery throughout the nation with the passage of the 13th Amendment.

But a group of congressmen and senators known as Radical Republicans disliked the plan, both for its perceived lenience to the rebels, and because it didn’t provide formerly enslaved people any civil rights aside from their freedom. Their response, the 1864 Wade-Davis Bill , would have required half of a state’s voters to take a loyalty oath and swear they had never voluntarily taken up arms against the Union. Former Confederates would be stripped of their right to vote, while formerly enslaved Black men would gain it. However, Lincoln thought the plan was too punitive and refused to sign it.

FREE BONUS ISSUE

As Confederate defeat became inevitable, Union leaders turned their attention to the future prosperity of enslaved people. In January 1865, General William Tecumseh Sherman issued an order to seize land from slaveholders in occupied Georgia and South Carolina and divide it among freedmen. Although the policy didn’t mention farm animals, it became known as the “40 acres and a mule” pledge.

Congress also set out to enshrine emancipation in the Constitution by passing the 13th Amendment on January 31, 1865, abolishing slavery. Lincoln made it clear that in order to rejoin the Union, Confederate states would have to agree to ratify the amendment. In March, at Lincoln’s behest, Congress created the Freedmen’s Bureau , a dedicated agency that would provide education, food, and assistance to emancipated people and oversee the division of land.

President Johnson’s leniency and the Black Codes

Tragedy reshaped the trajectory of Reconstruction—and ultimately undermined its promise. On April 15, 1865—just days after his final speech—Lincoln was assassinated and his vice president, Andrew Johnson, became president.

Although Johnson was a southern Democrat and a former enslaver who had joined Lincoln on a unity ticket, most Republicans expected him to continue Lincoln’s agenda. They underestimated Johnson’s racism and southern sympathies: Johnson’s vision for Reconstruction included blanket pardons for most former Confederates, including many high-level officials, and a lenient stance toward rebel states. He made no attempt to integrate Black people into southern institutions.

Johnson allowed former Confederate states to create all-white governments. When Congress reconvened in December 1865, its new members included many high-ranking Confederates, including former Vice President of the Confederacy Alexander Hamilton Stephens. Although Congress refused to admit them, Johnson had made his sympathies clear.

William Andrew Johnson—pictured here during a 1937 visit to Washington, D.C.—was the last living person to have been enslaved by a U.S. president: Andrew Johnson. Although Johnson freed the people he had enslaved before taking office, he remained sympathetic to former slave states after the Civil War.

His leniency would have disastrous consequences for Black people in the South, where former Confederates quickly established a slavery-like system to ensure white dominance and exploit Black labor.

You May Also Like

Americans have hated tipping almost as long as they’ve practiced it

Why are U.S. presidents allowed to pardon anyone—even for treason?

Lincoln was killed before their eyes. Then their own horror began.

In November 1865, Mississippi’s all-white legislature enacted a set of draconian laws called Black Codes, which curtailed Black people’s ability to own or rent property, move freely, control their own employment, and marry. Harsh penalties included forced, unpaid labor, seizure of possessions, and even the removal of children, who could be “apprenticed” to former slaveholders. All white people could legally enforce the codes.

The codes prompted other former Confederate states to enact copycat laws. In response, Radical Republicans in Congress introduced the nation’s first civil rights law, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 . It granted citizenship to all non-Native American men born in the United States, regardless of race or former servitude, and guaranteed they would benefit from all laws concerning “the security of person and property.” When Johnson vetoed the bill, Congress overrode it.

Congressional Reconstruction begins

Empowered by an election that swayed Congressional power in their direction, Radical Republicans took the reins of Reconstruction in 1866 and began undoing Johnson’s policies.

In 1867 and 1868, Congress passed four Reconstruction Acts establishing military rule in former Confederate states and revoking some high-ranking Confederates’ right to vote and hold office. In order to reestablish ties to the Union, rebel states had to let Congress review their constitutions, extend voting rights to all men, and ratify the 13 th and 14 th Amendments.

The 14 th Amendment , adopted in July 1868, granted citizenship to all people born or naturalized in the United States, forbade states from depriving any person of “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law,” and provided all people equal protection under the law.

Although citizenship technically guaranteed Black men the right to vote, most were kept from southern polls through violence and intimidation. The 15 th Amendment , ratified in February 1870, made it unconstitutional to abridge someone’s right to vote because of their race.

On March 31, 1870, Thomas Mundy Peterson of Perth Amboy, New Jersey, became the first African American to vote in an election under the just-enacted provisions of the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The Reconstruction Acts and Reconstruction Amendments reshaped the political structure of the South. Two sets of white Republican operatives rose to prominence: the derisively named “carpetbaggers,” who had moved south after the war, and “scalawags,” white Southerners who supported the rise of Black Southerners’ political power. ( Today ‘physical symbols of white supremacy’ are coming down. What changed? )

Men who had once been enslaved now constituted a political majority throughout much of the South—and most were fervent Republicans. Hundreds of thousands of Black men registered to vote, and between 1863 and 1877, about 2,000 served were elected to public office. Among them were South Carolina’s Joseph H. Rainey , a formerly enslaved man who in 1869 became the first Black U.S. Congressman, and Mississippi’s Hiram Revels , a freeborn man who became the first Black U.S. Senator in 1870.

White backlash and the dismantling of Reconstruction

White Southerners resented what they saw as overly punitive policies and argued that Black people were racially inferior and unfit to govern. This white backlash spawned paramilitaries and hate groups like the Ku Klux Klan, which terrorized Black lawmakers and would-be voters. White Southerners carried out mass lynchings , attempted to overthrow Reconstruction governments, and fought their policies in court. ( Here's how the Confederate battle flag became an enduring symbol of racism. )

In the early 1870s, an economic depression and political scandals tarnished the Republican party’s reputation, giving Democrats a chance to regain power and end Reconstruction. The 1876 presidential election was bitterly contested amid allegations of voter suppression and tampering on both sides. After months of deadlock, southern Democrats made a backroom deal to accept Republican Rutherford B. Hayes’ win over Democrat Samuel Tilden in exchange for an end to Reconstruction.

As federal oversight of southern states ended, so did the protections that had allowed Black people to exercise their political and social rights. White lawmakers—many the same Confederate leaders who had formed all-white legislatures under Johnson—swiftly dismantled Reconstruction policies and enacted cruel “ Jim Crow ” laws that reestablished white rule. Jim Crow laws segregated social spaces, criminalized interaction between races, and disenfranchised Black voters through poll taxes, literacy tests, and other barriers.

Ultimately, the promise of Reconstruction offered Black Southerners only a fleeting taste of freedom. But the opportunities it so briefly enabled still resonate today. In the words of historian George Lipsitz, it was “a victory without victory”—a failure with disastrous consequences that nonetheless sowed the potential for future change.

It would take nearly a century for the civil rights movement to prompt legislation that ensured voting rights for all and spur other social reforms. More than a century and a half later, Black Americans still face deep disparities in everything from policing to homeownership , economic opportunity , education , and health . But Reconstruction also made it clear that with institutional and social will, racial equality could one day be achieved and protected.

Related Topics

- AMERICAN CIVIL WAR

- GOVERNMENTS

- LAW AND LEGISLATION

- PRESIDENTS OF THE UNITED STATES

General Grant's surprising rise from cadet to commander

Gettysburg was no ordinary battle. These maps reveal how Lee lost the fight.

How mail-in voting began on Civil War battlefields

This dish towel ended the Civil War

What was Leonard Bernstein and JFK's friendship really like?

- History & Culture

- Photography

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Reconstruction: A Timeline of the Post-Civil War Era

By: Farrell Evans

Updated: February 22, 2021 | Original: February 3, 2021

Between 1863 and 1877, the U.S. government undertook the task of integrating nearly four million formerly enslaved people into society after the Civil War bitterly divided the country over the issue of slavery . A white slaveholding south that had built its economy and culture on slave labor was now forced by its defeat in a war that claimed 620,000 lives to change its economic, political and social relations with African Americans.

“The war destroyed the institution of slavery, ensured the survival of the union, and set in motion economic and political changes that laid the foundation for the modern nation,” wrote Eric Foner, the author of Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863-1877 . “During Reconstruction, the United States made its first attempt. . .to build an egalitarian society on the ashes of slavery.”

Reconstruction is generally divided into three phases: Wartime Reconstruction, Presidential Reconstruction and Radical or Congressional Reconstruction, which ended with the Compromise of 1877, when the U.S. government pulled the last of its troops from southern states, ending the Reconstruction era.

Wartime Reconstruction

December 8, 1863: The Ten-Percent Plan Two years into the Civil War in 1863 and nearly a year after signing the Emancipation Proclamation , President Abraham Lincoln announced the Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction or the Ten-Percent Plan, which required 10 percent of a Confederate state’s voters to pledge an oath of allegiance to the Union to begin the process of readmission to the Union.

With the exception of top Confederate leaders, the proclamation also included a full pardon and restoration of property, excluding enslaved people, for those who took part in the war against the Union. Eric Foner writes that Lincoln’s Ten-Percent Plan “might be better viewed as a device to shorten the war and solidify white support for emancipation” rather than a genuine effort to reconstruct the south.

July 2, 1864: The Wade Davis Bill Radical Republicans from the House and the Senate considered Lincoln’s Ten-Percent plan too lenient on the South. They considered success nothing less than a complete transformation of southern society.

Passed in Congress in July 1864, the Wade-Davis Bill required that 50 percent of white males in rebel states swear a loyalty oath to the constitution and the union before they could convene state constitutional convents. Co-sponsored by Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio and Congressman Henry Davis of Maryland, the bill also called for the government to grant African American men the right to vote and that “anyone who has voluntarily borne arms against the United States,” should be denied the right to vote.

Asserting that he wasn’t ready to be “inflexibly committed to any single plan of restoration,” Lincoln pocket-vetoed the bill, which infuriated Wade and Davis, who accused the President in a manifesto of “executive usurpation” in an effort to ensure the support of southern whites once the war was over. The Wade-Davis Bill was never implemented.

January 16, 1865: Forty-Acres and a Mule On this day, General William Tecumseh Sherman issued Field Order No. 15, which redistributed roughly 400,000 confiscated acres of land in Lowcountry Georgia and South Carolina in 40-acre plots to newly freed Black families. When the Freedmen’s Bureau was established in March 1865, created partly to redistribute confiscated land from southern whites, it gave legal title for 40-acre plots to African Americans and white southern unionists.

After the war was over, President Andrew Johnson returned most of the land to the former white slaveowners. At its peak during Reconstruction, the Freedmen’s Bureau had 900 agents scattered across 11 southern states handling everything from labor disputes to distributing clothing and food to starting schools to protecting freedmen from the Ku Klux Klan .

April 14, 1865: Lincoln's Assassination Six days after General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia to the Union Army’s Commanding General Ulysses Grant in Appomattox, Virginia, effectively ending the Civil War, Lincoln was shot at Ford’s Theater in Washington D.C. by John Wilkes Booth , a stage actor.

Just 41 days before his assassination, the 16th President had used his second inaugural address to signal reconciliation between the north and south. “With malice toward none; with charity for all ... let us strive to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds,” he said. But the effort to bind these wounds through Reconstruction policies would be left to Vice President Andrew Johnson, who became President when Lincoln died.

READ MORE: At His Second Inauguration, Abraham Lincoln Tried to Unite the Nation

Presidential Reconstruction

May 29, 1865: Andrew Johnson’s Reconstruction Plan President’s Johnson’s Reconstruction plan offered general amnesty to southern white people who pledged a future loyalty to the U.S. government, with the exception of Confederate leaders who would later receive individual pardons.

The plan also gave southern whites the power to reclaim property, with the exception of enslaved people and granted the states the right to start new governments with provisional governors. Yet Johnson’s plan did nothing to deter the white landowners from continuing to economically exploit their former slaves.

“Virtually from the moment the Civil War ended,” writes Eric Foner, “ the search began for the legal means of subordinating a volatile Black population that regarded economic independence as a corollary of freedom and the old labor discipline as a badge of slavery.”

December 6, 1865: The 13th Amendment The ratification of the 13th Amendment abolished slavery in the United States, with the “ exception as a punishment for a crime.” Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863 only covered the 3 million slaves in Confederate-controlled states during the Civil War. The 13th amendment was the first of three Reconstruction amendments.

READ MORE: Does an Exception Clause in the 13th Amendment Still Permit Slavery?

1865: The Black Codes To thwart any social and economic mobility that Black people might take under their status as free people, southern states beginning in late 1865 with Mississippi and South Carolina enacted Black Codes, various laws that reinforced Black economic subjugation to their former slaveowners.

In South Carolina there were vagrancy laws that could lead to imprisonment for “persons who lead idle or disorderly lives” and apprenticeship laws that allowed white employers to take Black children from homes for labor if they could prove that the parents were destitute, unfit or vagrants. According to Foner, “the entire complex of labor regulations and criminal laws was enforced by a police apparatus and judicial system in which Blacks enjoyed virtually no voice whatever.”

READ MORE: How the Black Codes Limited African American Progress After the Civil War

Congressional Reconstruction

March 2, 1867: Reconstruction Act of 1867 The Reconstruction Act of 1867 outlined the terms for readmission to representation of rebel states. The bill divided the former Confederate states, except for Tennessee, into five military districts. Each state was required to write a new constitution, which needed to be approved by a majority of voters—including African Americans—in that state. In addition, each state was required to ratify the 13th and 14th amendments to the Constitution. After meeting these criteria related to protecting the rights of African Americans and their property, the former Confederate states could gain full recognition and federal representation in Congress.

July 9, 1868 : 14th Amendment The 14 th amendment granted citizenship to all persons "born or naturalized in the United States," including former enslaved persons, and provided all citizens with “equal protection under the laws,” extending the provisions of the Bill of Rights to the states. The amendment authorized the government to punish states that abridged citizens’ right to vote by proportionally reducing their representation in Congress.

WATCH: The 15th Amendment

February 3, 1870: 15 th Amendment The 15th Amendment prohibited states from disenfranchising voters “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” The amendment left open the possibility, however, that states could institute voter qualifications equally to all races, and many former confederate states took advantage of this provision, instituting poll taxes and literacy tests, among other qualifications.

READ MORE: When Did African Americans Get the Right to Vote?

February 23, 1870: Hiram Revels Elected as First Black U.S. Senator On this day, Hiram Revels, an African Methodist Episcopal minister, became the first African American to serve in Congress when he was elected by the Mississippi State Legislature to finish the last two years of a term.

During Reconstruction, 16 African Americans served in Congress. By 1870, Black men held three Congressional seats in South Carolina and a seat on the state Supreme Court—Jonathan J. Wright. Over 600 Black men served in state legislators during the Reconstruction period.

Blanche K. Bruce, another Mississippian, became the first African American in 1875 to serve a full term in the U.S. Senate.

READ MORE: The First Black Man Elected to Congress Was Nearly Blocked From Taking His Seat

April 20, 1871: The Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 To suppress Black economic and political rights in the South during Reconstruction, the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist groups like the Knights of the White Camelia were formed to enforce the Black Codes and terrorize Black people and any white people who supported them.

Founded in 1865 in Pulaski, Tennessee by a group of Confederate veterans, the Ku Klux Klan carried out a reign of terror during Reconstruction that forced Congress to empower President Ulysses S. Grant to stop the group’s violence. The Third Enforcement Act or the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 , as it is better known, allowed federal troops to make hundreds of arrests in South Carolina, forcing perhaps 2,000 Klansmen to flee the state. According to Foner, the Federal intervention had “broken the Klan’s back and produced a dramatic decline in violence throughout the South.”

March 1, 1875: Civil Rights Act of 1875 The last major piece of major Reconstruction legislation, the Civil Rights Act of 1875, guaranteed African Americans equal treatment in public transportation, public accommodations and jury service. In 1883 the decision was overturned in the Supreme Court, however. Justices ruled that the legislation was unconstitutional on the grounds that the Constitution did not extend to private businesses and that it was unauthorized by the 13 th and 14 th amendments.

The End of Reconstruction

April 24, 1877: Rutherford B. Hayes and the Compromise of 1877 Twelve years after the close of the Civil War, President Rutherford B. Hayes pulled federal troops from their posts surrounding the capitals of Louisiana and South Carolina—the last states occupied by the U.S. government.

According Foner, Hayes didn’t withdraw the troops as widely believed, but the few that remained were of no consequence to the reemergence of a white political rule in these states. In what is widely known as the Compromise of 1877 , Democrats accepted Hayes’ victory as long as he made concessions such as the troop withdrawal and naming a southerner to his cabinet. “Every state in the South,” said a Black Louisianan, “had got into the hands of the very men that that held us as slaves.”

READ MORE: How the 1876 Election Effectively Ended Reconstruction

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The Reconstruction Era (1865–1877)

An era marked by thwarted progress and racial strife

- Important Historical Figures

- U.S. Presidents

- Native American History

- American Revolution

- America Moves Westward

- The Gilded Age

- Crimes & Disasters

- The Most Important Inventions of the Industrial Revolution

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- B.S., Texas A&M University

The Reconstruction era was a period of healing and rebuilding in the Southern United States following the American Civil War (1861-1865) that played a critical role in the history of civil rights and racial equality in America. During this tumultuous time, the U.S. government attempted to deal with the reintegration of the 11 Southern states that had seceded from the Union, along with 4 million newly freed enslaved people.

Reconstruction demanded answers to a multitude of difficult questions. On what terms would the Confederate states be accepted back into the Union? How were for former Confederate leaders, considered traitors by many in the North, to be dealt with? And perhaps most momentously, did emancipation mean that Black people were to enjoy the same legal and social status as White people?

Fast Facts: Reconstruction Era

- Short Description: The period of recovery and rebuilding in the Southern United States following the American Civil War

- Key Players: U.S. Presidents Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Johnson, and Ulysses S. Grant; U.S. Senator Charles Sumner

- Event Start Date: December 8, 1863

- Event End Date: March 31, 1877

- Location: Southern United States of America

In 1865 and 1866, during the administration of President Andrew Johnson , the Southern states enacted restrictive and discriminatory Black Codes —laws intended to control the behavior and labor of Black Americans. Outrage over these laws in Congress led to the replacement of Johnson’s so-called Presidential Reconstruction approach with that of the more radical wing of the Republican Party . The ensuing period known as Radical Reconstruction resulted in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 , which for the first time in American history gave Black people a voice in government. By the mid-1870s, however, extremist forces—such as the Ku Klux Klan —succeeded in restoring many aspects of white supremacy in the South.

Reconstruction After the Civil War

As a Union victory became more of certainty, America’s struggle with Reconstruction began before the end of the Civil War. In 1863, months after signing his Emancipation Proclamation , President Abraham Lincoln introduced his Ten Percent Plan for Reconstruction. Under the plan, if one-tenth of a Confederate state’s prewar voters signed an oath of loyalty to the Union, they be would be allowed to form a new state government with the same constitutional rights and powers they had enjoyed before secession.

More than a blueprint for rebuilding the postwar South, Lincoln saw the Ten Percent Plan as a tactic for further weakening the resolve of the Confederacy. After none of the Confederate states agreed to accept the plan, Congress in 1864 passed the Wade-Davis Bill , barring the Confederate states from rejoining the Union until a majority of the state’s voters had sworn their loyalty. Though Lincoln pocket vetoed the bill, he and many of his fellow Republicans remained convinced that equal rights for all formerly enslaved Black persons had to be a condition of a state’s readmission to the Union. On April 11, 1865, in his last speech before his assassination , Lincoln express his opinion that some “very intelligent” Black men or Black men who had joined the Union army deserved the right to vote. Notably, no consideration for the rights of Black women was expressed during Reconstruction.

Presidential Reconstruction

Taking office in April 1865, following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, President Andrew Johnson ushered in a two-year-long period known as Presidential Reconstruction. Johnson’s plan for restoring the splintered Union pardoned all Southern White persons except Confederate leaders and wealthy plantation owners and restored all of their constitutional rights and property except enslaved persons.

To be accepted back into the Union, the former Confederate states were required to abolish the practice of slavery, renounce their secession, and compensate the federal government for its Civil War expenses. Once these conditions were met, however, the newly restored Southern states were allowed to manage their governments and legislative affairs. Given this opportunity, the Southern states responded by enacting a series of racially discriminatory laws known as the Black Codes.

Black Codes

Enacted during 1865 and 1866, the Black Codes were laws intended to restrict the freedom of Black Americans in the South and ensure their continued availability as a cheap labor force even after the abolishment of slavery during the Civil War.

All Black persons living in the states that enacted Black Code laws were required to sign yearly labor contracts. Those who refused or were otherwise unable to do so could be arrested, fined, and if unable to pay their fines and private debts, forced to perform unpaid labor. Many Black children—especially those without parental support—were arrested and forced into unpaid labor for white planters.

The restrictive nature and ruthless enforcement of the Black Codes drew the outrage and resistance of Black Americans and seriously reduced Northern support for President Johnson and the Republican Party. Perhaps more significant to the eventual outcome of Reconstruction, the Black Codes gave the more radical arm of the Republican Party renewed influence in Congress.

Radical Republicans

Arising around 1854, before the Civil War, the Radical Republicans were a faction within the Republican Party who demanded the immediate, complete and permanent eradication of slavery. During the Civil War, they were opposed by the moderate Republicans, including President Abraham Lincoln, and by pro-slavery Democrats and Northern liberals until the end of Reconstruction in 1877.

After the Civil War, the Radical Republicans pushed for full implementation of emancipation through the immediate and unconditional establishment of civil rights for formerly enslaved persons. After the Reconstruction measures of President Andrew Johnson in 1866 resulted in the continued abuse of formerly enslaved Blacks in the South, the Radical Republicans pushed for the enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment and civil rights laws. They opposed allowing former Confederate military officers in the Southern states to hold elected offices and pressed for granting “freedmen,” people who had been enslaved before emancipation.

Influential Radical Republicans such as Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Senator Charles Sumner from Massachusetts demanded that the new governments of the Southern states be based on racial equality and the granting of universal voting rights for all male residents regardless of race. However, the more moderate Republican majority in Congress favored working with President Johnson to modify his Reconstruction measures. In early 1866, Congress refused to recognize or seat representatives and senators who had been elected from the former Confederate states of the South and passed the Freedmen’s Bureau and Civil Rights Bills.

Civil Rights Bill of 1866 and Freedmen’s Bureau

Enacted by Congress on April 9, 1866, over President Johnson’s veto , the Civil Rights Bill of 1866 became America’s first civil rights legislation. The bill mandated that all male persons born in the United States, except for American Indians, regardless of their “race or color, or previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude” were “declared to be citizens of the United States” in every state and territory. The bill thus granted all citizens the “full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property.”

Believing the federal government should take an active role in creating a multiracial society in the postwar South, the Radical Republicans saw the bill as a logical next step in Reconstruction. Taking a more anti-federalist stance, however, President Johnson vetoed the bill, calling it “another step, or rather a stride, toward centralization and the concentration of all legislative power in the national Government.” In overriding Johnson’s veto, lawmakers set the stage for a showdown between Congress and the president over the future of the former Confederacy and the civil rights of Black Americans.

The Freedmen’s Bureau

In March 1865, Congress, at the recommendation of President Abraham Lincoln, enacted the Freedmen’s Bureau Act creating a U.S. government agency to oversee the end of slavery in the South by providing food, clothing, fuel, and temporary housing to newly freed enslaved persons and their families.

During the Civil War, Union forces had confiscated vast areas of farmland owned by Southern plantation owners. Known as the “ 40 acres and a mule ” provision, part of Lincoln’s Freedmen’s Bureau Act authorized the bureau to rent or sell land this land to formerly enslaved persons. However, in the summer of 1865, President Johnson ordered all of this federally controlled land to be returned to its former White owners. Now lacking land, most formerly enslaved persons were forced to return to working on the same plantations where they had toiled for generations. While they now worked for minimal wages or as sharecroppers, they had little hope of achieving the same economic mobility enjoyed by White citizens. For decades, most Southern Black people were forced to remain propertyless and mired in poverty.

Reconstruction Amendments

Although President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation had ended the practice of slavery in the Confederate states in 1863, the issue remained at the national level. To be allowed to reenter the Union, the former Confederate states were required to agree to abolish slavery, but no federal law had been enacted to prevent those states from simply reinstituting the practice through their new constitutions. Between 1865 and 1870, the U.S. Congress addressed passed and the states ratified a series of three Constitutional amendments that abolished slavery nationwide and addressed other inequities in the legal and social status of all Black Americans.

Thirteenth Amendment

On February 8, 1864, with the Union victory in the Civil War virtually ensured, Radical Republicans led by Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania introduced a resolution calling for the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Passed by Congress on January 31, 1865, and ratified by the states on December 6, 1865—the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery “within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” The former Confederate states were required to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment as a condition of regaining their pre-secession representation in Congress.

Fourteenth Amendment

Ratified on July 9, 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment granted citizenship to all persons “born or naturalized in the United States,” including formerly enslaved persons. Extending the protections of the Bill of Rights to the states, the Fourteenth Amendment also provided all citizens regardless of race or former condition of enslavement with “equal protection under the laws” of the United States. It further ensures that no citizen’s right to “life, liberty, or property” will be denied without due process of law . States that unconstitutionally attempted to restrict their citizens’ right to vote could be punished by having their representation in Congress reduced.

Finally, in granting Congress the power to enforce its provisions, the Fourteenth Amendment enabled the enactment of landmark 20th-century racial equality legislation, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 , and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 .

Fifteenth Amendment

Shortly after the election of President Ulysses S. Grant on March 4, 1869, Congress approved the Fifteenth Amendment , prohibiting the states from restricting the right to vote because of race.

Ratified on February 3, 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment prohibited the states from limiting the voting rights of their male citizens “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” However, the amendment did not prohibit the states from enacting restrictive voter qualifications laws that applied equally to all races. Many former Confederate states took advantage of this omission by instituting poll taxes, literacy tests , and “ grandfather clauses ” clearly intended to prevent Black persons from voting. Though always controversial, these discriminatory practices would be allowed to continue until the enactment of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Congressional or Radical Reconstruction

In the 1866 mid-term congressional elections , Northern voters overwhelmingly rejected President Johnson’s Reconstruction policies, giving Radical Republicans nearly total control of Congress. Now controlling both the House of Representatives and the Senate, Radical Republicans were assured the votes needed to override any of Johnson’s vetoes to their soon-to-come Reconstruction legislation. This political uprising ushered in the period of Congressional or Radical Reconstruction.

The Reconstruction Acts

Enacted during 1867 and 1868, the Radical Republican-sponsored Reconstruction Acts specified the conditions under which the formerly seceded Southern states of the Confederacy would be readmitted to the Union after the Civil War.

Enacted in March 1867, the First Reconstruction Act, also known as the Military Reconstruction Act, divided the former Confederate states into five Military Districts, each governed by a Union general. The Act placed the Military Districts under martial law, with Union troops deployed to keep the peace and protect formerly enslaved persons.

The Second Reconstruction Act, enacted on March 23, 1867, supplemented the First Reconstruction Act by assigning Union troops to oversee voter registration and voting in the Southern states.

The deadly 1866 New Orleans and Memphis Race Riots had convinced Congress that Reconstruction policies needed to be enforced. By creating “radical regimes” and enforcing martial law throughout the South, the Radical Republicans hoped to facilitate their Radical Reconstruction plan. Though most Southern White people hated the “regimes” and being overseen by Union troops, the Radical Reconstruction policies resulted in all of the Southern states being readmitted to the Union by the end of 1870.

When Did Reconstruction End?

During the 1870s, the Radical Republicans began to back away from their expansive definition of the power of the federal government. Democrats argued that the Republican’s Reconstruction plan’s exclusion of the South’s “best men”—the White plantation owners—from political power was to blame for much of the violence and corruption in the region. The effectiveness of the Reconstruction Acts and constitutional amendments was further diminished by a series of Supreme Court decisions, beginning in 1873.

An economic depression from 1873 to 1879 saw much of the South fell into poverty, allowing the Democratic Party to win back control of the House of Representatives and heralding the end Reconstruction. By 1876, the legislatures of only three Southern states: South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana remained under Republican control. The outcome of the 1876 presidential election between Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel J. Tilden, was decided by disputed vote counts from those three states. After a controversial compromise saw Hayes's inaugurate president, Union troops were withdrawn from all Southern states. With the federal government no longer responsible for protecting the rights of the formerly enslaved people, Reconstruction had ended.

However, unforeseen results of the period from 1865 to 1876 would continue to impact Black Americans and the societies of both the South and North for over a century.

Reconstruction in the South

In the South, Reconstruction brought a massive, often painful, social, and political transition. While nearly four million formerly enslaved Black Americans gained freedom and some political power, those gains were diminished by lingering poverty and racist laws such as the Black Codes of 1866 and the Jim Crow laws of 1887.

Though freed from slavery, most Black Americans in the South remained hopelessly mired in rural poverty. Having been denied educations under slavery, many formerly enslaved people were forced by economic necessity to

Despite being free, most southern Black Americans continued to live in desperate rural poverty. Having been denied education and wages under slavery, ex-slaves were often forced by the necessity of their economic circumstances to return to or remain with their former White slave owners, working on their plantations for minimal wages or as sharecroppers .

According to historian Eugene Genovese, over 600,000 formerly enslaved persons stayed with their masters. As Black activists and scholar W.E.B. Du Bois wrote, the “slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.”

As a result of Reconstruction, Black citizens in the Southern states gained the right to vote. In many congressional districts across the South, Black people comprised a majority of the population. In 1870, Joseph Rainey of South Carolina was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, becoming the first popularly elected Black member of Congress. Though they never achieved representation proportionate to their total number, some 2,000 Black held elected office from the local to national level during Reconstruction.

In 1874, Black members of Congress, led by South Carolina Representative Robert Brown Elliot, were instrumental in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1875 , outlawing discrimination based on race in hotels, theaters, and railway cars.

However, the growing political power of Black people provoked a violent backlash from many White people who struggled to hold on to their supremacy . By implementing racially motivated voter disenfranchisement measures such as poll taxes and literacy tests, Whites in the South succeeded in undermining the very purpose of Reconstruction. The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments went largely unenforced, setting the stage for the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

Reconstruction in the North

Reconstruction in the South meant a massive social and political upheaval and a devastated economy. By contrast, the Civil War and Reconstruction brought opportunities for progress and growth. Passed during the Civil War, economic stimulus legislation such as the Homestead Act and the Pacific Railway Act opened the Western territories to waves of settlers .

Debates over the newly acquired voting rights for Black Americans helped drive the women’s suffrage movement , which eventually succeeded with the election of Jeannette Rankin of Montana to the U.S. Congress in 1917 and the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

The Legacy of Reconstruction

Though they were repeatedly either ignored or flagrantly violated, the anti-racial discrimination Reconstruction amendments remained in the Constitution. In 1867, U.S. Senator Charles Sumner had prophetically called them “sleeping giants” that would be awakened by future generations of Americans struggling to at last bring true freedom and equality to the descendants of slavery. Not until the civil rights movement of the 1960s—aptly called the “Second Reconstruction”—did America again attempt to fulfill the political and social promises of Reconstruction.

- Berlin, Ira. “Slaves Without Masters: The Free Negro in the Antebellum South.” Oxford University Press, 1981, ISBN-10 : 1565840283.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. “Black Reconstruction in America.” Transaction Publishers, 2013, ISBN:1412846676.

- Berlin, Ira, editor. “Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861–1867.” University of North Carolina Press (1982), ISBN: 978-1-4696-0742-9.

- Lynch, John R. “The Facts of Reconstruction.” The Neale Publishing Company (1913), http://www.gutenberg.org/files/16158/16158-h/16158-h.htm.

- Fleming, Walter L. “Documentary History of Reconstruction: Political, Military, Social, Religious, Educational, and Industrial.” Palala Press (April 22, 2016), ISBN-10: 1354267508.

- Timeline of the Reconstruction Era

- Black History Timeline: 1865–1869

- 14th Amendment Summary

- The Wade-Davis Bill and Reconstruction

- Biography of Andrew Johnson, 17th President of the United States

- Thaddeus Stevens

- The Black Struggle for Freedom

- 10 Facts to Know About Andrew Johnson

- Black History and Women Timeline 1860-1869

- The Black Codes and Why They Still Matter Today

- The Jim Crow Era

- The American Civil War and Secession

- What Is a Literacy Test?

- Women's Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment

- The History of Juneteenth Celebrations

- Slavery in 19th Century America

Home — Essay Samples — History — Civil War — Civil War Reconstruction

Civil War Reconstruction

- Categories: Civil War Reconstruction

About this sample

Words: 1270 |

Published: Jan 15, 2019

Words: 1270 | Pages: 3 | 7 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: History Life

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

5 pages / 2220 words

2 pages / 961 words

3 pages / 1415 words

2 pages / 945 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Civil War

The American Civil War, fought from 1861 to 1865, remains one of the most defining and consequential events in U.S. history. It was a conflict born out of a complex web of political, economic, and social factors. In this essay, [...]

Harriet Tubman's greatest achievement lies in her ability to inspire hope and instill a sense of agency in those who had been stripped of their humanity by the institution of slavery. Her unwavering commitment to freedom and [...]

The Civil War was a pivotal moment in American history, a time of great conflict and division. It was a time when the power of rhetoric was at its peak, as leaders on both sides of the conflict used speeches and propaganda to [...]

The Civil War was a pivotal moment in American history, pitting the North against the South in a bloody conflict that ultimately led to the abolition of slavery in the United States. While the outcome of the war favored the [...]

“War is what happens when language fails” said Margaret Atwood. Throughout history and beyond, war has been contemplated differently form one nation to another, or even, one person to another. While some people believe in what [...]

The primary role of the military is the protection of territorial sovereignty. This does not preclude it from being involved in operations other than war to enhance total national defence. The employment of the Infantry [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 5

- An overview and the 13th Amendment

Life after slavery for African Americans

- Black Codes

- The First KKK

- The Freedmen's Bureau

- The 14th Amendment

- The 15th Amendment

- The Compromise of 1877

- Failure of Reconstruction

- Comparing the effects of the Civil War on American national identity

Reconstruction

- The Thirteenth Amendment (1865) ended slavery, and slavery’s end meant newfound freedom for African Americans.

- During the period of Reconstruction , some 2000 African Americans held government jobs.

- The black family, the black church, and education were central elements in the lives of post-emancipation African Americans.

- Many African Americans lived in desperate rural poverty across the South in the decades following the Civil War.

Emancipation: promise and poverty

Family, faith, and education, the kkk and the end of reconstruction, what do you think, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

SOCIALSTUDIESHELP.COM

Effects of the civil war: socioeconomic, political, & cultural impacts, effects of the civil war, introduction.

The American Civil War, fought between 1861 and 1865, remains one of the most significant events in the nation’s history. This brutal confrontation between the Northern states (Union) and the Southern states (Confederacy) has been analyzed from countless perspectives, with many historians focusing on its causes, primary battles, and political dynamics. However, the war’s effects extend far beyond its immediate aftermath, leaving an indelible mark on America’s socioeconomic fabric, political landscape, and cultural ethos.

The necessity to study the war’s aftereffects arises from the profound changes it brought about. Understanding these changes can help shed light on many current societal issues, and highlight the deep-rooted complexities of America’s historical trajectory. This essay delves into these profound aftereffects, tracing the impacts of the war on various aspects of American life.

Emancipation and the African American Experience

At the heart of the Civil War lay the contentious issue of slavery. While not the sole cause of the conflict, the abolitionist sentiments in the North, coupled with the South’s economic reliance on slave labor, intensified the rift. The war’s conclusion heralded major changes for the African American population.

With the Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863, approximately 3.5 million enslaved African Americans in the Confederate states were declared free. Although this did not immediately free all slaves, it was a significant political move that paved the way for the eventual end of slavery. The ratification of the 13th Amendment in 1865 legally abolished slavery throughout the United States.

While emancipation was a monumental step forward, it was just the beginning of a long struggle for true equality for African Americans. The Reconstruction era (1865-1877) was intended to reintegrate the Southern states and rebuild the South’s devastated economy, all while ensuring the newly acquired rights of the former enslaved population. However, many white Southerners resented these changes. Laws known as Black Codes were swiftly enacted in Southern states, restricting the rights and movements of African Americans and ensuring they remained a cheap labor force.

The federal government’s efforts to protect African American rights culminated in the 14th Amendment (1868), granting citizenship to anyone born or naturalized in the U.S., and the 15th Amendment (1870), which prohibited voting discrimination based on race, color, or previous servitude. Yet, the South’s resistance persisted.

By the late 19th century, a systematic and oppressive system of racial segregation emerged in the South: the Jim Crow era. Under Jim Crow laws , African Americans were relegated to a status of second-class citizens, denied basic rights, subjected to racial terror, and routinely disenfranchised. This period solidified racial disparities that would persist well into the 20th century, and its implications for racial relations in America are still felt today.

Economic Transformations

The Civil War had profound effects on the American economy. The conflict not only altered the immediate economic realities due to wartime destruction but also catalyzed long-term shifts in economic structures and priorities.

One of the most prominent transformations was the decline of the Southern plantation system. Before the war, the South was heavily reliant on its plantation-based economy, which was undergirded by slave labor. With the abolition of slavery, the plantation system became untenable. Large plantations were often divided into smaller plots and farmed by freedmen as sharecroppers. However, this new system, sharecropping , while different in structure, still trapped many African Americans in cycles of debt and poverty.

Conversely, the Northern states witnessed an economic boom, particularly in industrial sectors. The war necessitated the rapid production of goods, from weapons to clothing. Factories burgeoned, and with the increasing reach of the railroad system, goods could be transported more easily than ever before. This industrial growth laid the foundation for America’s Gilded Age, a period of rapid economic expansion and technological innovation.

The need for more structured labor systems emerged with industrial expansion. Labor unions began to form, championing workers’ rights and protesting against poor working conditions, long hours, and inadequate pay. This period saw significant labor movements, such as the Haymarket Riot in 1886 and the Pullman Strike in 1894, reflecting the ongoing tensions between workers and industrial capitalists.

Sociopolitical Changes

The conclusion of the Civil War heralded a new era in American politics. The balance of power between the federal government and states, the very issue at the heart of the secessionist movement, shifted substantially.

The federal government emerged from the war with increased authority. Its role in dictating domestic policies and overruling state decisions became more pronounced, setting a precedent for the expanding scope of federal governance in subsequent years. This shift was evident in the federal government’s efforts during the Reconstruction era to oversee the reintegration of the Southern states and ensure the rights of African Americans.

Political dynamics also underwent significant change. The Radical Republicans, a faction within the Republican Party, gained substantial influence during and after the war. Advocating for the strict punishment of the secessionist states and robust rights for African Americans, they played a central role in shaping Reconstruction policies. The Reconstruction Acts of 1867, which mandated military oversight in the South and enforced voting rights for African Americans, were heavily influenced by their ideals.

However, the dominance of the Radical Republicans was short-lived. By the late 1870s, there was growing Northern fatigue with the “Southern problem.” This culminated in the Compromise of 1877, where Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was granted the presidency in exchange for the withdrawal of federal troops from the South, effectively ending Reconstruction. The power dynamics once again shifted, allowing for the Democratic South’s resurgence and setting the stage for the oppressive Jim Crow era.

Cultural and Intellectual Repercussions

The Civil War, given its magnitude and significance, had an undeniable influence on American culture and intellectual thought. Its legacy is evident not just in political or economic realms but also in the myriad artistic expressions and intellectual discourses it inspired.

Artistically, the war and its aftermath found representation in various forms. Literature, in particular, became a powerful medium to convey the struggles, hopes, and tragedies of the era. Novels like “The Red Badge of Courage” by Stephen Crane presented a realistic portrayal of the war, capturing the psychological complexities of its soldiers. Poetry, with notable contributions from Walt Whitman like “Drum-Taps,” expressed the sorrow, pride, and desolation of the times.

Visual arts, too, played a role in shaping the collective memory of the war. Paintings and photographs documented the horrors of battlefields, the plight of soldiers, and the devastation of entire communities. The era’s photography, especially works by figures like Mathew Brady, brought the grim realities of war directly to the American public, creating a lasting visual record.

Educational institutions and curricula were not untouched by the war’s impact. Universities, especially in the South, grappled with financial challenges and loss of students. Post-war, there was a concerted effort to reinterpret and teach the war’s causes and consequences, with some narratives, especially in the South, pushing the “Lost Cause” myth. This myth romanticized the Confederate cause, portraying it as a noble but doomed struggle against overwhelming odds, conveniently downplaying or ignoring the central role of slavery in the conflict.

Long-Term Effects on American Military and Foreign Policy

The Civil War left an indelible mark on American military strategy and foreign policy. While the immediate repercussions were evident in the war’s tactics and technologies, the longer-term effects are discerned in how America approached conflicts and its position on the global stage.

Militarily, the war was a harbinger of modern warfare. Innovations in weaponry, such as rifled muskets and the use of railroads for troop movements, changed the dynamics of battles. Traditional line infantry tactics became less effective against the improved range and accuracy of new firearms, leading to the development of trench warfare, a precursor to what would be seen on a larger scale in World War I.

The concept of total war, as exemplified by General Sherman’s March to the Sea, became an integral part of military strategy. This approach, targeting not just enemy combatants but also civilian infrastructure and resources, aimed to break the opponent’s will to fight.

On the international front, the Civil War had several implications. The European powers, closely observing the conflict, learned valuable lessons in warfare and military technology. Moreover, the war affected America’s foreign relations. The Confederacy’s attempts to gain official recognition and support from European powers, especially Britain and France, created diplomatic challenges. Although the Confederacy’s efforts were unsuccessful, they revealed the intricacies of international politics and the significance of economic interests, with the British textile industry’s reliance on Southern cotton playing a pivotal role in diplomacy.

Post-war, the United States, having resolved its internal conflict, began to assert itself more confidently on the world stage. The doctrine of Manifest Destiny , although conceived before the war, gained momentum, leading to further territorial expansion and underpinning America’s approach to international relations well into the 20th century.

Social and Gender Dynamics

Beyond the visible economic and political changes the Civil War instigated, it also catalyzed profound shifts in social hierarchies and gender roles. The very fabric of American society was redefined in the war’s crucible.

For the African American community, the war and subsequent Reconstruction represented a period of hope and tumultuous change. The promise of equality, though enshrined in constitutional amendments, was constantly challenged by white supremacy. However, the war did facilitate the emergence of African American leaders, both in politics and community spheres. Institutions, primarily churches and schools, became centers of empowerment and played pivotal roles in the struggle for civil rights.

Women, too, experienced transformative shifts in their societal roles. The exigencies of war thrust many women into roles previously deemed unsuitable for them. Women not only took charge of households and farms in the absence of men but also actively contributed to the war effort. They served as nurses, spies, and even soldiers in some instances. Organizations like the United States Sanitary Commission saw significant female participation, as women organized fundraisers, cared for the wounded, and provided supplies to the troops.

The aftermath of the war further solidified women’s roles in public spheres. Inspired by the abolitionist movement and their contributions during the war, many women began to advocate for their own rights, leading to the rise of the women’s suffrage movement. Figures like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony championed the cause, drawing parallels between the plight of enslaved African Americans and the systemic oppression of women.

The American Civil War was not merely a clash of armies; it was a monumental event that reshaped every aspect of American life. From the economy’s restructuring to the profound shifts in political dynamics, from the cultural expressions it inspired to the alterations in social and gender hierarchies, its effects were both immediate and lasting.

To understand modern America, one must reckon with the Civil War’s legacy. The issues it brought to the fore, especially racial inequality, continue to resonate. The struggles and hopes of the era remind us of the enduring nature of the pursuit of justice and equality. As the nation has grown and evolved, the lessons of the Civil War serve as both a cautionary tale and a beacon of hope, illuminating the complexities and potential of the American experiment.

Class Outline – Effects of the Civil War

The Civil War was one of the most tragic wars in American history. More Americans died then in all other wars combined. Brother fought against brother and the nation was torn apart. In the end, we must look at the important consequences of the conflict. There may be others, but this is a good list to work off.

A. The nation was reunited and the southern states were not allowed to secede.

B. The South was placed under military rule and divided into military districts. Southern states then had to apply for readmission to the Union.

C. The Federal government proved itself supreme over the states. Essentially this was a war over states rights and federalism and the victor was the power of the national government.

D. Slavery was effectively ended. While slavery was not officially outlawed until the passage of the 13th amendment, the slaves were set free upon the end of the war.

E. Reconstruction, the plan to rebuild America after the war, began.

F. Industrialism began as a result of the increase in wartime production and the development of new technologies.

Why the Reconstruction After the Civil War Was a Failure Essay

Introduction.

Bibliography

The success or the failure of the implementation of a national policy is normally subject to contention. However, the fundamental consent is that if the prime objectives of its implementation are not met, then it is ultimately considered a failure. The reconstruction era refers to the period following the civil war whereby the numerous different affiliations in the government intended to find a solution to the socio-economic and political problems imposed by the civil war, which was characterized by intense disarray and disorder in the government.

The whites from the south opposed all aspects of equality, while blacks were after complete liberty and their own land in the United States, which resulted to riots. The reconstruction era is arguably one of the most divisive periods in the history of the United States and took place during 1865-1877 [1] .

Many people are of the opinion that the failure of the reconstruction after the civil war can be significantly attributed to black politics, which was commonly referred as Negro government. Foner notes that paradoxically, racism diminished due to the Northern Democratic Appeal. This paper discusses why the reconstruction after the civil war is considered a failure.

The most probable cause of the failure of the reconstruction following the civil war is black legislatures. The court’s intervention also played a significant role in ensuring that the reconstruction of the south failed in the realization of its goals and objectives. Foner is of the opinion that the court was initially reluctant in attempting to solve the controversies associated with the reconstruction.

In addition, the compromise of 1877 can be perceived to be a solution to the disputed presidential election of 1877 played an important role in ending the reconstruction era after the civil war. The banks also had a role in accelerating the failure of the reconstruction of the south after the civil war. This arguably evident by the fact that the Freedman’s Savings bank held large sums of the black’s money, lacking even the money to give to its depositors.

The Freedman’s Savings Bank operations came to a halt. The reduction of the prices of the crops was also a significant contributor to the failure of the reconstruction of the south, because most of the farmers could make a decent living out of their earnings. The depression had adverse effects on commerce and the economic situation, which significantly impaired social mobility for the blacks [2] .

The reconstruction of the south under the administration of President Lincoln and Johnson are major indicators of the difficulties that were inherent in the quest to reshape the South following the civil war.