- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

100+ Research Vocabulary Words & Phrases

The academic community can be conservative when it comes to enforcing academic writing style , but your writing shouldn’t be so boring that people lose interest midway through the first paragraph! Given that competition is at an all-time high for academics looking to publish their papers, we know you must be anxious about what you can do to improve your publishing odds.

To be sure, your research must be sound, your paper must be structured logically, and the different manuscript sections must contain the appropriate information. But your research must also be clearly explained. Clarity obviously depends on the correct use of English, and there are many common mistakes that you should watch out for, for example when it comes to articles , prepositions , word choice , and even punctuation . But even if you are on top of your grammar and sentence structure, you can still make your writing more compelling (or more boring) by using powerful verbs and phrases (vs the same weaker ones over and over). So, how do you go about achieving the latter?

Below are a few ways to breathe life into your writing.

1. Analyze Vocabulary Using Word Clouds

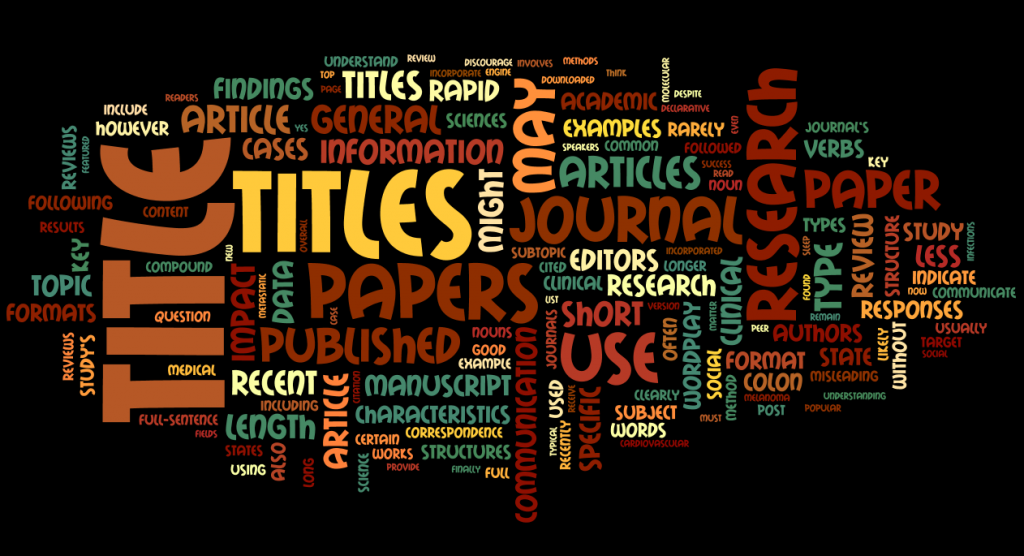

Have you heard of “Wordles”? A Wordle is a visual representation of words, with the size of each word being proportional to the number of times it appears in the text it is based on. The original company website seems to have gone out of business, but there are a number of free word cloud generation sites that allow you to copy and paste your draft manuscript into a text box to quickly discover how repetitive your writing is and which verbs you might want to replace to improve your manuscript.

Seeing a visual word cloud of your work might also help you assess the key themes and points readers will glean from your paper. If the Wordle result displays words you hadn’t intended to emphasize, then that’s a sign you should revise your paper to make sure readers will focus on the right information.

As an example, below is a Wordle of our article entitled, “ How to Choose the Best title for Your Journal Manuscript .” You can see how frequently certain terms appear in that post, based on the font size of the text. The keywords, “titles,” “journal,” “research,” and “papers,” were all the intended focus of our blog post.

2. Study Language Patterns of Similarly Published Works

Study the language pattern found in the most downloaded and cited articles published by your target journal. Understanding the journal’s editorial preferences will help you write in a style that appeals to the publication’s readership.

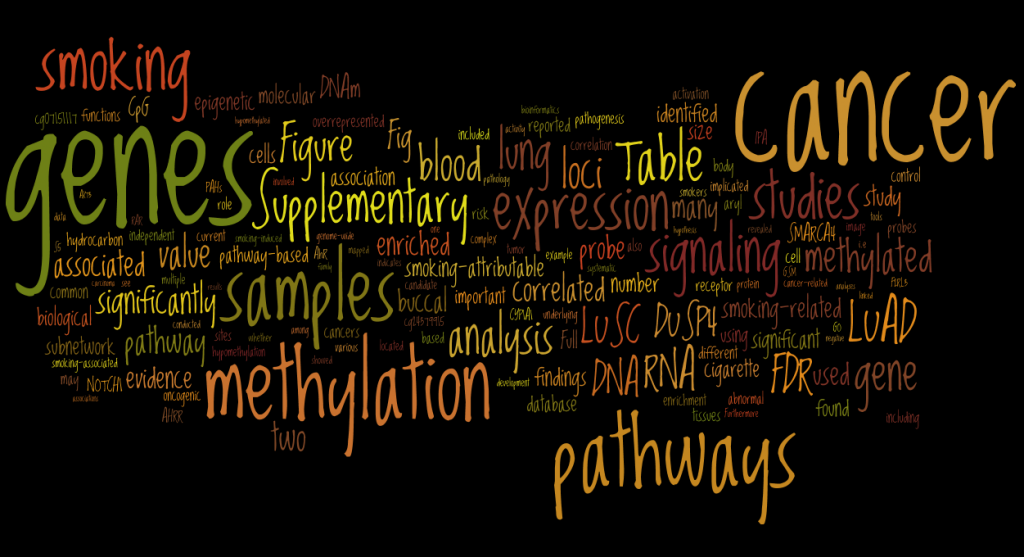

Another way to analyze the language of a target journal’s papers is to use Wordle (see above). If you copy and paste the text of an article related to your research topic into the applet, you can discover the common phrases and terms the paper’s authors used.

For example, if you were writing a paper on links between smoking and cancer , you might look for a recent review on the topic, preferably published by your target journal. Copy and paste the text into Wordle and examine the key phrases to see if you’ve included similar wording in your own draft. The Wordle result might look like the following, based on the example linked above.

If you are not sure yet where to publish and just want some generally good examples of descriptive verbs, analytical verbs, and reporting verbs that are commonly used in academic writing, then have a look at this list of useful phrases for research papers .

3. Use More Active and Precise Verbs

Have you heard of synonyms? Of course you have. But have you looked beyond single-word replacements and rephrased entire clauses with stronger, more vivid ones? You’ll find this task is easier to do if you use the active voice more often than the passive voice . Even if you keep your original sentence structure, you can eliminate weak verbs like “be” from your draft and choose more vivid and precise action verbs. As always, however, be careful about using only a thesaurus to identify synonyms. Make sure the substitutes fit the context in which you need a more interesting or “perfect” word. Online dictionaries such as the Merriam-Webster and the Cambridge Dictionary are good sources to check entire phrases in context in case you are unsure whether a synonym is a good match for a word you want to replace.

To help you build a strong arsenal of commonly used phrases in academic papers, we’ve compiled a list of synonyms you might want to consider when drafting or editing your research paper . While we do not suggest that the phrases in the “Original Word/Phrase” column should be completely avoided, we do recommend interspersing these with the more dynamic terms found under “Recommended Substitutes.”

A. Describing the scope of a current project or prior research

B. outlining a topic’s background, c. describing the analytical elements of a paper, d. discussing results, e. discussing methods, f. explaining the impact of new research, wordvice writing resources.

For additional information on how to tighten your sentences (e.g., eliminate wordiness and use active voice to greater effect), you can try Wordvice’s FREE APA Citation Generator and learn more about how to proofread and edit your paper to ensure your work is free of errors.

Before submitting your manuscript to academic journals, be sure to use our free AI proofreader to catch errors in grammar, spelling, and mechanics. And use our English editing services from Wordvice, including academic editing services , cover letter editing , manuscript editing , and research paper editing services to make sure your work is up to a high academic level.

We also have a collection of other useful articles for you, for example on how to strengthen your writing style , how to avoid fillers to write more powerful sentences , and how to eliminate prepositions and avoid nominalizations . Additionally, get advice on all the other important aspects of writing a research paper on our academic resources pages .

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, 113 great research paper topics.

General Education

One of the hardest parts of writing a research paper can be just finding a good topic to write about. Fortunately we've done the hard work for you and have compiled a list of 113 interesting research paper topics. They've been organized into ten categories and cover a wide range of subjects so you can easily find the best topic for you.

In addition to the list of good research topics, we've included advice on what makes a good research paper topic and how you can use your topic to start writing a great paper.

What Makes a Good Research Paper Topic?

Not all research paper topics are created equal, and you want to make sure you choose a great topic before you start writing. Below are the three most important factors to consider to make sure you choose the best research paper topics.

#1: It's Something You're Interested In

A paper is always easier to write if you're interested in the topic, and you'll be more motivated to do in-depth research and write a paper that really covers the entire subject. Even if a certain research paper topic is getting a lot of buzz right now or other people seem interested in writing about it, don't feel tempted to make it your topic unless you genuinely have some sort of interest in it as well.

#2: There's Enough Information to Write a Paper

Even if you come up with the absolute best research paper topic and you're so excited to write about it, you won't be able to produce a good paper if there isn't enough research about the topic. This can happen for very specific or specialized topics, as well as topics that are too new to have enough research done on them at the moment. Easy research paper topics will always be topics with enough information to write a full-length paper.

Trying to write a research paper on a topic that doesn't have much research on it is incredibly hard, so before you decide on a topic, do a bit of preliminary searching and make sure you'll have all the information you need to write your paper.

#3: It Fits Your Teacher's Guidelines

Don't get so carried away looking at lists of research paper topics that you forget any requirements or restrictions your teacher may have put on research topic ideas. If you're writing a research paper on a health-related topic, deciding to write about the impact of rap on the music scene probably won't be allowed, but there may be some sort of leeway. For example, if you're really interested in current events but your teacher wants you to write a research paper on a history topic, you may be able to choose a topic that fits both categories, like exploring the relationship between the US and North Korea. No matter what, always get your research paper topic approved by your teacher first before you begin writing.

113 Good Research Paper Topics

Below are 113 good research topics to help you get you started on your paper. We've organized them into ten categories to make it easier to find the type of research paper topics you're looking for.

Arts/Culture

- Discuss the main differences in art from the Italian Renaissance and the Northern Renaissance .

- Analyze the impact a famous artist had on the world.

- How is sexism portrayed in different types of media (music, film, video games, etc.)? Has the amount/type of sexism changed over the years?

- How has the music of slaves brought over from Africa shaped modern American music?

- How has rap music evolved in the past decade?

- How has the portrayal of minorities in the media changed?

Current Events

- What have been the impacts of China's one child policy?

- How have the goals of feminists changed over the decades?

- How has the Trump presidency changed international relations?

- Analyze the history of the relationship between the United States and North Korea.

- What factors contributed to the current decline in the rate of unemployment?

- What have been the impacts of states which have increased their minimum wage?

- How do US immigration laws compare to immigration laws of other countries?

- How have the US's immigration laws changed in the past few years/decades?

- How has the Black Lives Matter movement affected discussions and view about racism in the US?

- What impact has the Affordable Care Act had on healthcare in the US?

- What factors contributed to the UK deciding to leave the EU (Brexit)?

- What factors contributed to China becoming an economic power?

- Discuss the history of Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies (some of which tokenize the S&P 500 Index on the blockchain) .

- Do students in schools that eliminate grades do better in college and their careers?

- Do students from wealthier backgrounds score higher on standardized tests?

- Do students who receive free meals at school get higher grades compared to when they weren't receiving a free meal?

- Do students who attend charter schools score higher on standardized tests than students in public schools?

- Do students learn better in same-sex classrooms?

- How does giving each student access to an iPad or laptop affect their studies?

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of the Montessori Method ?

- Do children who attend preschool do better in school later on?

- What was the impact of the No Child Left Behind act?

- How does the US education system compare to education systems in other countries?

- What impact does mandatory physical education classes have on students' health?

- Which methods are most effective at reducing bullying in schools?

- Do homeschoolers who attend college do as well as students who attended traditional schools?

- Does offering tenure increase or decrease quality of teaching?

- How does college debt affect future life choices of students?

- Should graduate students be able to form unions?

- What are different ways to lower gun-related deaths in the US?

- How and why have divorce rates changed over time?

- Is affirmative action still necessary in education and/or the workplace?

- Should physician-assisted suicide be legal?

- How has stem cell research impacted the medical field?

- How can human trafficking be reduced in the United States/world?

- Should people be able to donate organs in exchange for money?

- Which types of juvenile punishment have proven most effective at preventing future crimes?

- Has the increase in US airport security made passengers safer?

- Analyze the immigration policies of certain countries and how they are similar and different from one another.

- Several states have legalized recreational marijuana. What positive and negative impacts have they experienced as a result?

- Do tariffs increase the number of domestic jobs?

- Which prison reforms have proven most effective?

- Should governments be able to censor certain information on the internet?

- Which methods/programs have been most effective at reducing teen pregnancy?

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of the Keto diet?

- How effective are different exercise regimes for losing weight and maintaining weight loss?

- How do the healthcare plans of various countries differ from each other?

- What are the most effective ways to treat depression ?

- What are the pros and cons of genetically modified foods?

- Which methods are most effective for improving memory?

- What can be done to lower healthcare costs in the US?

- What factors contributed to the current opioid crisis?

- Analyze the history and impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic .

- Are low-carbohydrate or low-fat diets more effective for weight loss?

- How much exercise should the average adult be getting each week?

- Which methods are most effective to get parents to vaccinate their children?

- What are the pros and cons of clean needle programs?

- How does stress affect the body?

- Discuss the history of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians.

- What were the causes and effects of the Salem Witch Trials?

- Who was responsible for the Iran-Contra situation?

- How has New Orleans and the government's response to natural disasters changed since Hurricane Katrina?

- What events led to the fall of the Roman Empire?

- What were the impacts of British rule in India ?

- Was the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki necessary?

- What were the successes and failures of the women's suffrage movement in the United States?

- What were the causes of the Civil War?

- How did Abraham Lincoln's assassination impact the country and reconstruction after the Civil War?

- Which factors contributed to the colonies winning the American Revolution?

- What caused Hitler's rise to power?

- Discuss how a specific invention impacted history.

- What led to Cleopatra's fall as ruler of Egypt?

- How has Japan changed and evolved over the centuries?

- What were the causes of the Rwandan genocide ?

- Why did Martin Luther decide to split with the Catholic Church?

- Analyze the history and impact of a well-known cult (Jonestown, Manson family, etc.)

- How did the sexual abuse scandal impact how people view the Catholic Church?

- How has the Catholic church's power changed over the past decades/centuries?

- What are the causes behind the rise in atheism/ agnosticism in the United States?

- What were the influences in Siddhartha's life resulted in him becoming the Buddha?

- How has media portrayal of Islam/Muslims changed since September 11th?

Science/Environment

- How has the earth's climate changed in the past few decades?

- How has the use and elimination of DDT affected bird populations in the US?

- Analyze how the number and severity of natural disasters have increased in the past few decades.

- Analyze deforestation rates in a certain area or globally over a period of time.

- How have past oil spills changed regulations and cleanup methods?

- How has the Flint water crisis changed water regulation safety?

- What are the pros and cons of fracking?

- What impact has the Paris Climate Agreement had so far?

- What have NASA's biggest successes and failures been?

- How can we improve access to clean water around the world?

- Does ecotourism actually have a positive impact on the environment?

- Should the US rely on nuclear energy more?

- What can be done to save amphibian species currently at risk of extinction?

- What impact has climate change had on coral reefs?

- How are black holes created?

- Are teens who spend more time on social media more likely to suffer anxiety and/or depression?

- How will the loss of net neutrality affect internet users?

- Analyze the history and progress of self-driving vehicles.

- How has the use of drones changed surveillance and warfare methods?

- Has social media made people more or less connected?

- What progress has currently been made with artificial intelligence ?

- Do smartphones increase or decrease workplace productivity?

- What are the most effective ways to use technology in the classroom?

- How is Google search affecting our intelligence?

- When is the best age for a child to begin owning a smartphone?

- Has frequent texting reduced teen literacy rates?

How to Write a Great Research Paper

Even great research paper topics won't give you a great research paper if you don't hone your topic before and during the writing process. Follow these three tips to turn good research paper topics into great papers.

#1: Figure Out Your Thesis Early

Before you start writing a single word of your paper, you first need to know what your thesis will be. Your thesis is a statement that explains what you intend to prove/show in your paper. Every sentence in your research paper will relate back to your thesis, so you don't want to start writing without it!

As some examples, if you're writing a research paper on if students learn better in same-sex classrooms, your thesis might be "Research has shown that elementary-age students in same-sex classrooms score higher on standardized tests and report feeling more comfortable in the classroom."

If you're writing a paper on the causes of the Civil War, your thesis might be "While the dispute between the North and South over slavery is the most well-known cause of the Civil War, other key causes include differences in the economies of the North and South, states' rights, and territorial expansion."

#2: Back Every Statement Up With Research

Remember, this is a research paper you're writing, so you'll need to use lots of research to make your points. Every statement you give must be backed up with research, properly cited the way your teacher requested. You're allowed to include opinions of your own, but they must also be supported by the research you give.

#3: Do Your Research Before You Begin Writing

You don't want to start writing your research paper and then learn that there isn't enough research to back up the points you're making, or, even worse, that the research contradicts the points you're trying to make!

Get most of your research on your good research topics done before you begin writing. Then use the research you've collected to create a rough outline of what your paper will cover and the key points you're going to make. This will help keep your paper clear and organized, and it'll ensure you have enough research to produce a strong paper.

What's Next?

Are you also learning about dynamic equilibrium in your science class? We break this sometimes tricky concept down so it's easy to understand in our complete guide to dynamic equilibrium .

Thinking about becoming a nurse practitioner? Nurse practitioners have one of the fastest growing careers in the country, and we have all the information you need to know about what to expect from nurse practitioner school .

Want to know the fastest and easiest ways to convert between Fahrenheit and Celsius? We've got you covered! Check out our guide to the best ways to convert Celsius to Fahrenheit (or vice versa).

These recommendations are based solely on our knowledge and experience. If you purchase an item through one of our links, PrepScholar may receive a commission.

Christine graduated from Michigan State University with degrees in Environmental Biology and Geography and received her Master's from Duke University. In high school she scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT and was named a National Merit Finalist. She has taught English and biology in several countries.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

50 Useful Academic Words & Phrases for Research

Like all good writing, writing an academic paper takes a certain level of skill to express your ideas and arguments in a way that is natural and that meets a level of academic sophistication. The terms, expressions, and phrases you use in your research paper must be of an appropriate level to be submitted to academic journals.

Therefore, authors need to know which verbs , nouns , and phrases to apply to create a paper that is not only easy to understand, but which conveys an understanding of academic conventions. Using the correct terminology and usage shows journal editors and fellow researchers that you are a competent writer and thinker, while using non-academic language might make them question your writing ability, as well as your critical reasoning skills.

What are academic words and phrases?

One way to understand what constitutes good academic writing is to read a lot of published research to find patterns of usage in different contexts. However, it may take an author countless hours of reading and might not be the most helpful advice when faced with an upcoming deadline on a manuscript draft.

Briefly, “academic” language includes terms, phrases, expressions, transitions, and sometimes symbols and abbreviations that help the pieces of an academic text fit together. When writing an academic text–whether it is a book report, annotated bibliography, research paper, research poster, lab report, research proposal, thesis, or manuscript for publication–authors must follow academic writing conventions. You can often find handy academic writing tips and guidelines by consulting the style manual of the text you are writing (i.e., APA Style , MLA Style , or Chicago Style ).

However, sometimes it can be helpful to have a list of academic words and expressions like the ones in this article to use as a “cheat sheet” for substituting the better term in a given context.

How to Choose the Best Academic Terms

You can think of writing “academically” as writing in a way that conveys one’s meaning effectively but concisely. For instance, while the term “take a look at” is a perfectly fine way to express an action in everyday English, a term like “analyze” would certainly be more suitable in most academic contexts. It takes up fewer words on the page and is used much more often in published academic papers.

You can use one handy guideline when choosing the most academic term: When faced with a choice between two different terms, use the Latinate version of the term. Here is a brief list of common verbs versus their academic counterparts:

Although this can be a useful tip to help academic authors, it can be difficult to memorize dozens of Latinate verbs. Using an AI paraphrasing tool or proofreading tool can help you instantly find more appropriate academic terms, so consider using such revision tools while you draft to improve your writing.

Top 50 Words and Phrases for Different Sections in a Research Paper

The “Latinate verb rule” is just one tool in your arsenal of academic writing, and there are many more out there. But to make the process of finding academic language a bit easier for you, we have compiled a list of 50 vital academic words and phrases, divided into specific categories and use cases, each with an explanation and contextual example.

Best Words and Phrases to use in an Introduction section

1. historically.

An adverb used to indicate a time perspective, especially when describing the background of a given topic.

2. In recent years

A temporal marker emphasizing recent developments, often used at the very beginning of your Introduction section.

3. It is widely acknowledged that

A “form phrase” indicating a broad consensus among researchers and/or the general public. Often used in the literature review section to build upon a foundation of established scientific knowledge.

4. There has been growing interest in

Highlights increasing attention to a topic and tells the reader why your study might be important to this field of research.

5. Preliminary observations indicate

Shares early insights or findings while hedging on making any definitive conclusions. Modal verbs like may , might , and could are often used with this expression.

6. This study aims to

Describes the goal of the research and is a form phrase very often used in the research objective or even the hypothesis of a research paper .

7. Despite its significance

Highlights the importance of a matter that might be overlooked. It is also frequently used in the rationale of the study section to show how your study’s aim and scope build on previous studies.

8. While numerous studies have focused on

Indicates the existing body of work on a topic while pointing to the shortcomings of certain aspects of that research. Helps focus the reader on the question, “What is missing from our knowledge of this topic?” This is often used alongside the statement of the problem in research papers.

9. The purpose of this research is

A form phrase that directly states the aim of the study.

10. The question arises (about/whether)

Poses a query or research problem statement for the reader to acknowledge.

Best Words and Phrases for Clarifying Information

11. in other words.

Introduces a synopsis or the rephrasing of a statement for clarity. This is often used in the Discussion section statement to explain the implications of the study .

12. That is to say

Provides clarification, similar to “in other words.”

13. To put it simply

Simplifies a complex idea, often for a more general readership.

14. To clarify

Specifically indicates to the reader a direct elaboration of a previous point.

15. More specifically

Narrows down a general statement from a broader one. Often used in the Discussion section to clarify the meaning of a specific result.

16. To elaborate

Expands on a point made previously.

17. In detail

Indicates a deeper dive into information.

Points out specifics. Similar meaning to “specifically” or “especially.”

19. This means that

Explains implications and/or interprets the meaning of the Results section .

20. Moreover

Expands a prior point to a broader one that shows the greater context or wider argument.

Best Words and Phrases for Giving Examples

21. for instance.

Provides a specific case that fits into the point being made.

22. As an illustration

Demonstrates a point in full or in part.

23. To illustrate

Shows a clear picture of the point being made.

24. For example

Presents a particular instance. Same meaning as “for instance.”

25. Such as

Lists specifics that comprise a broader category or assertion being made.

26. Including

Offers examples as part of a larger list.

27. Notably

Adverb highlighting an important example. Similar meaning to “especially.”

28. Especially

Adverb that emphasizes a significant instance.

29. In particular

Draws attention to a specific point.

30. To name a few

Indicates examples than previously mentioned are about to be named.

Best Words and Phrases for Comparing and Contrasting

31. however.

Introduces a contrasting idea.

32. On the other hand

Highlights an alternative view or fact.

33. Conversely

Indicates an opposing or reversed idea to the one just mentioned.

34. Similarly

Shows likeness or parallels between two ideas, objects, or situations.

35. Likewise

Indicates agreement with a previous point.

36. In contrast

Draws a distinction between two points.

37. Nevertheless

Introduces a contrasting point, despite what has been said.

38. Whereas

Compares two distinct entities or ideas.

Indicates a contrast between two points.

Signals an unexpected contrast.

Best Words and Phrases to use in a Conclusion section

41. in conclusion.

Signifies the beginning of the closing argument.

42. To sum up

Offers a brief summary.

43. In summary

Signals a concise recap.

44. Ultimately

Reflects the final or main point.

45. Overall

Gives a general concluding statement.

Indicates a resulting conclusion.

Demonstrates a logical conclusion.

48. Therefore

Connects a cause and its effect.

49. It can be concluded that

Clearly states a conclusion derived from the data.

50. Taking everything into consideration

Reflects on all the discussed points before concluding.

Edit Your Research Terms and Phrases Before Submission

Using these phrases in the proper places in your research papers can enhance the clarity, flow, and persuasiveness of your writing, especially in the Introduction section and Discussion section, which together make up the majority of your paper’s text in most academic domains.

However, it's vital to ensure each phrase is contextually appropriate to avoid redundancy or misinterpretation. As mentioned at the top of this article, the best way to do this is to 1) use an AI text editor , free AI paraphrasing tool or AI proofreading tool while you draft to enhance your writing, and 2) consult a professional proofreading service like Wordvice, which has human editors well versed in the terminology and conventions of the specific subject area of your academic documents.

For more detailed information on using AI tools to write a research paper and the best AI tools for research , check out the Wordvice AI Blog .

- How It Works

- PhD thesis writing

- Master thesis writing

- Bachelor thesis writing

- Dissertation writing service

- Dissertation abstract writing

- Thesis proposal writing

- Thesis editing service

- Thesis proofreading service

- Thesis formatting service

- Coursework writing service

- Research paper writing service

- Architecture thesis writing

- Computer science thesis writing

- Engineering thesis writing

- History thesis writing

- MBA thesis writing

- Nursing dissertation writing

- Psychology dissertation writing

- Sociology thesis writing

- Statistics dissertation writing

- Buy dissertation online

- Write my dissertation

- Cheap thesis

- Cheap dissertation

- Custom dissertation

- Dissertation help

- Pay for thesis

- Pay for dissertation

- Senior thesis

- Write my thesis

211 Research Topics in Linguistics To Get Top Grades

Many people find it hard to decide on their linguistics research topics because of the assumed complexities involved. They struggle to choose easy research paper topics for English language too because they think it could be too simple for a university or college level certificate.

All that you need to learn about Linguistics and English is sprawled across syntax, phonetics, morphology, phonology, semantics, grammar, vocabulary, and a few others. To easily create a top-notch essay or conduct a research study, you can consider this list of research topics in English language below for your university or college use. Note that you can fine-tune these to suit your interests.

Linguistics Research Paper Topics

If you want to study how language is applied and its importance in the world, you can consider these Linguistics topics for your research paper. They are:

- An analysis of romantic ideas and their expression amongst French people

- An overview of the hate language in the course against religion

- Identify the determinants of hate language and the means of propagation

- Evaluate a literature and examine how Linguistics is applied to the understanding of minor languages

- Consider the impact of social media in the development of slangs

- An overview of political slang and its use amongst New York teenagers

- Examine the relevance of Linguistics in a digitalized world

- Analyze foul language and how it’s used to oppress minors

- Identify the role of language in the national identity of a socially dynamic society

- Attempt an explanation to how the language barrier could affect the social life of an individual in a new society

- Discuss the means through which language can enrich cultural identities

- Examine the concept of bilingualism and how it applies in the real world

- Analyze the possible strategies for teaching a foreign language

- Discuss the priority of teachers in the teaching of grammar to non-native speakers

- Choose a school of your choice and observe the slang used by its students: analyze how it affects their social lives

- Attempt a critical overview of racist languages

- What does endangered language means and how does it apply in the real world?

- A critical overview of your second language and why it is a second language

- What are the motivators of speech and why are they relevant?

- Analyze the difference between the different types of communications and their significance to specially-abled persons

- Give a critical overview of five literature on sign language

- Evaluate the distinction between the means of language comprehension between an adult and a teenager

- Consider a native American group and evaluate how cultural diversity has influenced their language

- Analyze the complexities involved in code-switching and code-mixing

- Give a critical overview of the importance of language to a teenager

- Attempt a forensic overview of language accessibility and what it means

- What do you believe are the means of communications and what are their uniqueness?

- Attempt a study of Islamic poetry and its role in language development

- Attempt a study on the role of Literature in language development

- Evaluate the Influence of metaphors and other literary devices in the depth of each sentence

- Identify the role of literary devices in the development of proverbs in any African country

- Cognitive Linguistics: analyze two pieces of Literature that offers a critical view of perception

- Identify and analyze the complexities in unspoken words

- Expression is another kind of language: discuss

- Identify the significance of symbols in the evolution of language

- Discuss how learning more than a single language promote cross-cultural developments

- Analyze how the loss of a mother tongue affect the language Efficiency of a community

- Critically examine how sign language works

- Using literature from the medieval era, attempt a study of the evolution of language

- Identify how wars have led to the reduction in the popularity of a language of your choice across any country of the world

- Critically examine five Literature on why accent changes based on environment

- What are the forces that compel the comprehension of language in a child

- Identify and explain the difference between the listening and speaking skills and their significance in the understanding of language

- Give a critical overview of how natural language is processed

- Examine the influence of language on culture and vice versa

- It is possible to understand a language even without living in that society: discuss

- Identify the arguments regarding speech defects

- Discuss how the familiarity of language informs the creation of slangs

- Explain the significance of religious phrases and sacred languages

- Explore the roots and evolution of incantations in Africa

Sociolinguistic Research Topics

You may as well need interesting Linguistics topics based on sociolinguistic purposes for your research. Sociolinguistics is the study and recording of natural speech. It’s primarily the casual status of most informal conversations. You can consider the following Sociolinguistic research topics for your research:

- What makes language exceptional to a particular person?

- How does language form a unique means of expression to writers?

- Examine the kind of speech used in health and emergencies

- Analyze the language theory explored by family members during dinner

- Evaluate the possible variation of language based on class

- Evaluate the language of racism, social tension, and sexism

- Discuss how Language promotes social and cultural familiarities

- Give an overview of identity and language

- Examine why some language speakers enjoy listening to foreigners who speak their native language

- Give a forensic analysis of his the language of entertainment is different to the language in professional settings

- Give an understanding of how Language changes

- Examine the Sociolinguistics of the Caribbeans

- Consider an overview of metaphor in France

- Explain why the direct translation of written words is incomprehensible in Linguistics

- Discuss the use of language in marginalizing a community

- Analyze the history of Arabic and the culture that enhanced it

- Discuss the growth of French and the influences of other languages

- Examine how the English language developed and its interdependence on other languages

- Give an overview of cultural diversity and Linguistics in teaching

- Challenge the attachment of speech defect with disability of language listening and speaking abilities

- Explore the uniqueness of language between siblings

- Explore the means of making requests between a teenager and his parents

- Observe and comment on how students relate with their teachers through language

- Observe and comment on the communication of strategy of parents and teachers

- Examine the connection of understanding first language with academic excellence

Language Research Topics

Numerous languages exist in different societies. This is why you may seek to understand the motivations behind language through these Linguistics project ideas. You can consider the following interesting Linguistics topics and their application to language:

- What does language shift mean?

- Discuss the stages of English language development?

- Examine the position of ambiguity in a romantic Language of your choice

- Why are some languages called romantic languages?

- Observe the strategies of persuasion through Language

- Discuss the connection between symbols and words

- Identify the language of political speeches

- Discuss the effectiveness of language in an indigenous cultural revolution

- Trace the motivators for spoken language

- What does language acquisition mean to you?

- Examine three pieces of literature on language translation and its role in multilingual accessibility

- Identify the science involved in language reception

- Interrogate with the context of language disorders

- Examine how psychotherapy applies to victims of language disorders

- Study the growth of Hindi despite colonialism

- Critically appraise the term, language erasure

- Examine how colonialism and war is responsible for the loss of language

- Give an overview of the difference between sounds and letters and how they apply to the German language

- Explain why the placement of verb and preposition is different in German and English languages

- Choose two languages of your choice and examine their historical relationship

- Discuss the strategies employed by people while learning new languages

- Discuss the role of all the figures of speech in the advancement of language

- Analyze the complexities of autism and its victims

- Offer a linguist approach to language uniqueness between a Down Syndrome child and an autist

- Express dance as a language

- Express music as a language

- Express language as a form of language

- Evaluate the role of cultural diversity in the decline of languages in South Africa

- Discuss the development of the Greek language

- Critically review two literary texts, one from the medieval era and another published a decade ago, and examine the language shifts

Linguistics Essay Topics

You may also need Linguistics research topics for your Linguistics essays. As a linguist in the making, these can help you consider controversies in Linguistics as a discipline and address them through your study. You can consider:

- The connection of sociolinguistics in comprehending interests in multilingualism

- Write on your belief of how language encourages sexism

- What do you understand about the differences between British and American English?

- Discuss how slangs grew and how they started

- Consider how age leads to loss of language

- Review how language is used in formal and informal conversation

- Discuss what you understand by polite language

- Discuss what you know by hate language

- Evaluate how language has remained flexible throughout history

- Mimicking a teacher is a form of exercising hate Language: discuss

- Body Language and verbal speech are different things: discuss

- Language can be exploitative: discuss

- Do you think language is responsible for inciting aggression against the state?

- Can you justify the structural representation of any symbol of your choice?

- Religious symbols are not ordinary Language: what are your perspective on day-to-day languages and sacred ones?

- Consider the usage of language by an English man and someone of another culture

- Discuss the essence of code-mixing and code-switching

- Attempt a psychological assessment on the role of language in academic development

- How does language pose a challenge to studying?

- Choose a multicultural society of your choice and explain the problem they face

- What forms does Language use in expression?

- Identify the reasons behind unspoken words and actions

- Why do universal languages exist as a means of easy communication?

- Examine the role of the English language in the world

- Examine the role of Arabic in the world

- Examine the role of romantic languages in the world

- Evaluate the significance of each teaching Resources in a language classroom

- Consider an assessment of language analysis

- Why do people comprehend beyond what is written or expressed?

- What is the impact of hate speech on a woman?

- Do you believe that grammatical errors are how everyone’s comprehension of language is determined?

- Observe the Influence of technology in language learning and development

- Which parts of the body are responsible for understanding new languages

- How has language informed development?

- Would you say language has improved human relations or worsened it considering it as a tool for violence?

- Would you say language in a black populous state is different from its social culture in white populous states?

- Give an overview of the English language in Nigeria

- Give an overview of the English language in Uganda

- Give an overview of the English language in India

- Give an overview of Russian in Europe

- Give a conceptual analysis on stress and how it works

- Consider the means of vocabulary development and its role in cultural relationships

- Examine the effects of Linguistics in language

- Present your understanding of sign language

- What do you understand about descriptive language and prescriptive Language?

List of Research Topics in English Language

You may need English research topics for your next research. These are topics that are socially crafted for you as a student of language in any institution. You can consider the following for in-depth analysis:

- Examine the travail of women in any feminist text of your choice

- Examine the movement of feminist literature in the Industrial period

- Give an overview of five Gothic literature and what you understand from them

- Examine rock music and how it emerged as a genre

- Evaluate the cultural association with Nina Simone’s music

- What is the relevance of Shakespeare in English literature?

- How has literature promoted the English language?

- Identify the effect of spelling errors in the academic performance of students in an institution of your choice

- Critically survey a university and give rationalize the literary texts offered as Significant

- Examine the use of feminist literature in advancing the course against patriarchy

- Give an overview of the themes in William Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar”

- Express the significance of Ernest Hemingway’s diction in contemporary literature

- Examine the predominant devices in the works of William Shakespeare

- Explain the predominant devices in the works of Christopher Marlowe

- Charles Dickens and his works: express the dominating themes in his Literature

- Why is Literature described as the mirror of society?

- Examine the issues of feminism in Sefi Atta’s “Everything Good Will Come” and Bernadine Evaristos’s “Girl, Woman, Other”

- Give an overview of the stylistics employed in the writing of “Girl, Woman, Other” by Bernadine Evaristo

- Describe the language of advertisement in social media and newspapers

- Describe what poetic Language means

- Examine the use of code-switching and code-mixing on Mexican Americans

- Examine the use of code-switching and code-mixing in Indian Americans

- Discuss the influence of George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” on satirical literature

- Examine the Linguistics features of “Native Son” by Richard Wright

- What is the role of indigenous literature in promoting cultural identities

- How has literature informed cultural consciousness?

- Analyze five literature on semantics and their Influence on the study

- Assess the role of grammar in day to day communications

- Observe the role of multidisciplinary approaches in understanding the English language

- What does stylistics mean while analyzing medieval literary texts?

- Analyze the views of philosophers on language, society, and culture

English Research Paper Topics for College Students

For your college work, you may need to undergo a study of any phenomenon in the world. Note that they could be Linguistics essay topics or mainly a research study of an idea of your choice. Thus, you can choose your research ideas from any of the following:

- The concept of fairness in a democratic Government

- The capacity of a leader isn’t in his or her academic degrees

- The concept of discrimination in education

- The theory of discrimination in Islamic states

- The idea of school policing

- A study on grade inflation and its consequences

- A study of taxation and Its importance to the economy from a citizen’s perspectives

- A study on how eloquence lead to discrimination amongst high school students

- A study of the influence of the music industry in teens

- An Evaluation of pornography and its impacts on College students

- A descriptive study of how the FBI works according to Hollywood

- A critical consideration of the cons and pros of vaccination

- The health effect of sleep disorders

- An overview of three literary texts across three genres of Literature and how they connect to you

- A critical overview of “King Oedipus”: the role of the supernatural in day to day life

- Examine the novel “12 Years a Slave” as a reflection of servitude and brutality exerted by white slave owners

- Rationalize the emergence of racist Literature with concrete examples

- A study of the limits of literature in accessing rural readers

- Analyze the perspectives of modern authors on the Influence of medieval Literature on their craft

- What do you understand by the mortality of a literary text?

- A study of controversial Literature and its role in shaping the discussion

- A critical overview of three literary texts that dealt with domestic abuse and their role in changing the narratives about domestic violence

- Choose three contemporary poets and analyze the themes of their works

- Do you believe that contemporary American literature is the repetition of unnecessary themes already treated in the past?

- A study of the evolution of Literature and its styles

- The use of sexual innuendos in literature

- The use of sexist languages in literature and its effect on the public

- The disaster associated with media reports of fake news

- Conduct a study on how language is used as a tool for manipulation

- Attempt a criticism of a controversial Literary text and why it shouldn’t be studied or sold in the first place

Finding Linguistics Hard To Write About?

With these topics, you can commence your research with ease. However, if you need professional writing help for any part of the research, you can scout here online for the best research paper writing service.

There are several expert writers on ENL hosted on our website that you can consider for a fast response on your research study at a cheap price.

As students, you may be unable to cover every part of your research on your own. This inability is the reason you should consider expert writers for custom research topics in Linguistics approved by your professor for high grades.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Comment * Error message

Name * Error message

Email * Error message

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

As Putin continues killing civilians, bombing kindergartens, and threatening WWIII, Ukraine fights for the world's peaceful future.

Ukraine Live Updates

Research Paper Topics

Choose your Topic Smart

What starts well, ends well, so you need to be really careful with research paper topics. The topic of a research paper defines the whole piece of writing. How often have you chosen the book by its title? First impression is often influential, so make sure your topic will attract the reader instantly. By choosing your topic smart, the half of your job is done. That is why we have singled out several secrets on how to pick the best topic for you.

Browse Research Paper Topics by Category:

- Anthropology

- Argumentative

- Communication

- Criminal Justice

- Environmental

- Political Science

What is the Key to a Perfect Topic for a Research Paper?

The key to a perfect topic includes three main secrets: interest, precision, and innovation.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

It is impossible to do something great if you have no interest in what you are doing. For this reason, make sure you choose the topic that drives you. If you are bored by what you investigate, do not expect that your paper will be exciting. Right now, spend some minutes or even hours thinking about what interests you. Jot down all your preferences in life, science, politics, social issues etc. It will help you get the idea what you can write about.

After realizing what drives you, narrow this general idea to a more specific one. A research paper is not about beating around the bush. You will need clear facts and data. You will have to provide evidence to your ideas. You will need to be precise, specific and convincing.

Finally, the idea of any research is that it should be surprising and distinctive. Think what makes your perspective and approach special. What is the novelty of your research?

Use Technology

If you are still stuck, use technology. Today we have an opportunity to make our lives easier with a bit of technology used. You can find paper topic generators online. This software will examine the category you want to investigate and the keywords from your research. Within several seconds, this program generates paper topics, so you can try it yourself. It can help you get started with your assignment.

100% Effective Advice

We will now give you advice that is 100% effective when picking the topic. Firstly, forget about what others may think about your topic. This is your topic and this is your perception of the world. Stay personal and let your personal style get you the top grades. Secondly, never decide on the topic before analyzing the background for your research. By this we mean, investigate the topic before you start the research proper. It happens quite often that students choose the topic and later they realize there is no data or information to use. That is why conduct some research beforehand. Thirdly, read other researchers’ papers on the topic you want to write about. It will help you get the idea of the investigation. Moreover, it will help you understand whether you truly want to write a paper on this topic. Finally, when you have picked the topic, started your research, make sure you dedicate your time and energy. If you want to get high results, you need to study every little details of your research.

Examine Different Ideas

People often come up with genius ideas after analyzing thousands of other people’s ideas. This is how our brain works. That is why you can analyze other people’s ideas for research paper topics and think up your own. If you have never written any paper of that kind, it will help you understand the gist of this assignment, the style and the requirements. By comparing different topics, you can motivate yourself and get inspired with these ideas. Luckily, you have come to the right place. Here is our list of top 100 research paper topics.

Top 10 Argumentative Research Paper Topics:

Argumentative research papers examine some controversial issues. Your task is to provide your point of view, your argument, and support your idea with the evidence. This academic assignment requires appropriate structuring and formatting.

- Does a College Education Pay?

- Dual Career Families and Working Mothers

- Electronic Copyright and Piracy

- Drinking on Campus

- Education for Homeless Children

- Glass ceiling

- Honor System at Colleges

- Sex and Violence on TV

- Word Population and Hunger

- World Trade and Globalization

Top 10 Economics Research Paper Topics:

If you are studying economics, you can find various topics at our site. Check out topics of micro- and macroeconomics. See ideas for urgent economic problems, economic models and strategies. Get inspired and come up with your perfect topic.

- Beyond Make-or-Buy: Advances in Transaction Cost Economics

- Economic Aspects of Cultural Heritage

- Economics of Energy Markets

- Globalization and Inequality

- International Trade and Trade Restrictions

- Aggregate Expenditures Model and Equilibrium Output

- Taxes Versus Standards

- Predatory Pricing and Strategic Entry Barriers

- Marxian and Institutional Industrial Relations in the United States

- Twentieth-Century Economic Methodology

Top 10 Education Research Paper Topics:

Education has so many questions, and yet few answers. The list of education topic is endless. We have chosen the top 10 topics on the urgent issues in education. You can find ideas related to different approaches, methodology, classroom management, etc.

- Teachers Thinking About Their Practice

- Cognitive Approaches to Motivation in Education

- Responsive Classroom Management

- Ten Steps to Complex Learning

- Economics and School-to-Work

- Reading and Literacy in Adolescence

- Diversifying the Teaching Force

- Teacher-Student Relationships

- Preparing for College and Graduate School

- Role of Professional Learning

Top 10 History Research Paper Topics:

Choose your topic regarding cultural, economic, environmental, military, political or social history. See what other researchers investigated, compare their ideas and pick the topic that interests you.

- European Expansion

- Orientalism

- Current trends in Historiography

- Green Revolution

- Religion and War

- Women’s Emancipation Movements

- History of Civilization

Top 10 Psychology Research Paper Topics:

The list of psychology categories and topics is enormous. We have singled out the most popular topics on psychology in 2019. It is mostly topics on modern psychology. Choose the topic the appeals to you the most or ask our professionals to help you come up with some original idea.

- Imaging Techniques for the Localization of Brain Function

- Memory and Eyewitness Testimony

- Traditional Neuroscience Research Methods

- Meditation and the Relaxation Response

- Assessment of Mental Health in Older Adults

- Cross-Cultural Psychology and Research

- Industrial and Organizational Psychology

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- Prejudice and Stereotyping

- Nature Versus Nurture

Top 10 Biology Research Paper Topics:

Here you can find topics related to the science of all forms of life. Examine the topics from different fields in biology and choose the best one for you.

- Biological Warfare

- Clone and Cloning

- Genetic Disorders

- Genetic Engineering

- Kangaroos and Wallabies

- Mendelian Laws of Inheritance

- Molecular Biology

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Top 10 Chemistry Research Paper Topics:

The best way to understand chemistry is to write a paper on chemistry topic. Below you can see the topics from different fields of chemistry: organic, inorganic, physical, analytical and others.

- Acids and Bases

- Alkaline Earth Metals

- Dyes and Pigments

- Chemical Warfare

- Industrial Minerals

- Photochemistry

- Soaps and Detergents

- Transition Elements

Top 10 Physics Research Paper Topics:

Check out the topics on classical and modern physics. Find ideas for writing about interrelationships of physics to other sciences.

- Aerodynamics

- Atomic Theory

- Celestial Mechanics

- Fluid Dynamics

- Magnetic recording

- Microwave Communication

- Quantum mechanics

- Subatomic particles

Top 10 Sociology Research Paper Topics:

Find ideas related to different sociological theories, research and methodologies.

- Feminist Methodologies and Epistemology

- Quality-of-Life Research

- Sociology of Men and Masculinity

- Sociology of Leisure and Recreation

- Environmental Sociology

- Teaching and Learning in Sociology

- The History of Sociology: The North American Perspective

- The Sociology of Voluntary Associations

- Marriage and Divorce in the United States

- Urban Sociology in the 21 st Century

Top 10 Technology Research Paper Topics:

See topics related to the cutting-edge technology or dive into history of electronics, or even early advances in agriculture.

- Food Preservation: Freeze Drying, Irradiation, and Vacuum Packing

- Tissue Culturing

- Digital Telephony

- Computer-Aided Control Technology

- Minerals Prospecting

- Prefabricated Buildings

- Timber Engineering

- Quantum Electronic Devices

- Thermal Water Moderated Nuclear Reactors

- Long Range Radars and Early Warning Systems

What Makes a Good Topic for a Research Paper?

A good research paper topic is the one that is successful and manageable in your particular case. A successful research paper poses an interesting question you can actually answer. Just as important, it poses a question you can answer within the time available. The question should be one that interests you and deserves exploration. It might be an empirical question or a theoretical puzzle. In some fields, it might be a practical problem or policy issue. Whatever the question is, you need to mark off its boundaries clearly and intelligently so you can complete the research paper and not get lost in the woods. That means your topic should be manageable as well as interesting and important.

A topic is manageable if you can:

- Master the relevant literature

- Collect and analyze the necessary data

- Answer the key questions you have posed

- Do it all within the time available, with the skills you have

A topic is important if it:

- Touches directly on major theoretical issues and debates, or

- Addresses substantive topics of great interest in your field

Ideally, your topic can do both, engaging theoretical and substantive issues. In elementary education, for example, parents, teachers, scholars, and public officials all debate the effectiveness of charter schools, the impact of vouchers, and the value of different reading programs. A research paper on any of these would resonate within the university and well beyond it. Still, as you approach such topics, you need to limit the scope of your investigation so you can finish your research and writing on time. After all, to be a good research paper, it first has to be a completed one. A successful research paper poses an interesting question you can actually answer within the time available for the project. Some problems are simply too grand, too sweeping to master within the time limits. Some are too minor to interest you or anybody else.

The solution, however, is not to find a lukewarm bowl of porridge, a bland compromise. Nor is it to abandon your interest in larger, more profound issues such as the relationship between school organization and educational achievement or between immigration and poverty. Rather, the solution is to select a well-defined topic that is closely linked to some larger issue and then explore that link. Your research paper will succeed if you nail a well-defined topic. It will rise to excellence if you probe that topic deeply and show how it illuminates wider issues.The best theses deal with important issues, framed in manageable ways. The goal is to select a well-defined topic that is closely linked to some larger issue and can illuminate it.

You can begin your project with either a large issue or a narrowly defined topic, depending on your interests and the ideas you have generated. Whichever way you start, the goals are the same: to connect the two in meaningful ways and to explore your specific topic in depth.

Of course, the choice of a particular research paper topic depends on the course you’re taking. Our site can offer you the following research paper topics and example research papers:

Moving from a Research Paper Idea to a Research Paper Topic

Let’s begin as most students actually do, by going from a “big issue” to a more manageable research paper topic. Suppose you start with a big question such as, “Why has the United States fought so many wars since 1945?” That’s certainly a big, important question. Unfortunately, it’s too complex and sprawling to cover well in a research paper. Working with your professor or instructor, you could zero in on a related but feasible research topic, such as “Why did the Johnson administration choose to escalate the U.S. war in Vietnam?” By choosing this topic, your research paper can focus on a specific war and, within that, on a few crucial years in the mid-1960s.

You can draw on major works covering all aspects of the Vietnam War and the Johnson administration’s decision making. You have access to policy memos that were once stamped top secret. These primary documents have now been declassified, published by the State Department, and made available to research libraries. Many are readily available on the Web. You can also take advantage of top-quality secondary sources (that is, books and articles based on primary documents, interviews, and other research data).

Drawing on these primary and secondary sources, you can uncover and critique the reasons behind U.S. military escalation. As you answer this well-defined question about Vietnam, you can (and you should) return to the larger themes that interest you, namely, “What does the escalation in Southeast Asia tell us about the global projection of U.S. military power since 1945?” As one of America’s largest military engagements since World War II, the war in Vietnam should tell us a great deal about the more general question.

The goal here is to pick a good case to study, one that is compelling in its own right and speaks to the larger issue. It need not be a typical example, but it does need to illuminate the larger question. Some cases are better than others precisely because they illuminate larger issues. That’s why choosing the best cases makes such a difference in your research paper.

Since you are interested in why the United States has fought so often since 1945, you probably shouldn’t focus on U.S. invasions of Grenada, Haiti, or Panama in the past two decades. Why? Because the United States has launched numerous military actions against small, weak states in the Caribbean for more than a century. That is important in its own right, but it doesn’t say much about what has changed so dramatically since 1945. The real change since 1945 is the projection of U.S. power far beyond the Western Hemisphere, to Europe and Asia. You cannot explain this change—or any change, for that matter—by looking at something that remains constant.

In this case, to analyze the larger pattern of U.S. war fighting and the shift it represents, you need to pick examples of distant conflicts, such as Korea, Vietnam, Kosovo, Afghanistan, or Iraq. That’s the noteworthy change since 1945: U.S. military intervention outside the Western Hemisphere. The United States has fought frequently in such areas since World War II but rarely before then. Alternatively, you could use statistics covering many cases of U.S. intervention around the world, perhaps supplemented with some telling cases studies.

Students in the humanities want to explore their own big ideas, and they, too, need to focus their research. In English literature, their big issue might be “masculinity” or, to narrow the range a bit, “masculinity in Jewish American literature.” Important as these issues are, they are too vast for anyone to read all the major novels plus all the relevant criticism and then frame a comprehensive research paper.

If you don’t narrow these sprawling topics and focus your work, you can only skim the surface. Skimming the surface is not what you want to do in a research paper. You want to understand your subject in depth and convey that understanding to your readers.

That does not mean you have to abandon your interest in major themes. It means you have to restrict their scope in sensible ways. To do that, you need to think about which aspects of masculinity really interest you and then find works that deal with them.

You may realize your central concern is how masculinity is defined in response to strong women. That focus would still leave you considerable flexibility, depending on your academic background and what you love to read. That might be anything from a reconsideration of Macbeth to an analysis of early twentieth-century American novels, where men must cope with women in assertive new roles. Perhaps you are interested in another aspect of masculinity: the different ways it is defined within the same culture at the same moment. That would lead you to novelists who explore these differences in their characters, perhaps contrasting men who come from different backgrounds, work in different jobs, or simply differ emotionally. Again, you would have considerable flexibility in choosing specific writers.

Connecting a Specific Research Paper Topic to a Bigger Idea

Not all students begin their research paper concerned with big issues such as masculinity or American wars over the past half century. Some start with very specific topics in mind. One example might be the decision to create NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement encompassing Canada, the United States, and Mexico. Perhaps you are interested in NAFTA because you discussed it in a course, heard about it in a political campaign, or saw its effects firsthand on local workers, companies, and consumers. It intrigues you, and you would like to study it in a research paper. The challenge is to go from this clear-cut subject to a larger theme that will frame your paper.

Why do you even need to figure out a larger theme? Because NAFTA bears on several major topics, and you cannot explore all of them. Your challenge—and your opportunity—is to figure out which one captures your imagination.

One way to think about that is to finish this sentence: “For me, NAFTA is a case of ___________.” If you are mainly interested in negotiations between big and small countries, then your answer is, “For me, NAFTA is a case of a large country like the United States bargaining with a smaller neighbor.” Your answer would be different if you are mainly interested in decision making within the United States, Mexico, or Canada. In that case, you might say, “NAFTA seems to be a case where a strong U.S. president pushed a trade policy through Congress.” Perhaps you are more concerned with the role played by business lobbies. “For me, NAFTA is a case of undue corporate influence over foreign economic policy.” Or you could be interested in the role of trade unions, environmental groups, or public opinion.

The NAFTA decision is related to all these big issues and more. You cannot cover them all. There is not enough time, and even if there were, the resulting paper would be too diffuse, too scattershot. To make an impact, throw a rock, not a handful of pebbles.

Choosing one of these large issues will shape your research paper on NAFTA. If you are interested in U.S. decision making, for example, you might study the lobbying process or perhaps the differences between Democrats and Republicans. If you are interested in diplomacy, you would focus on negotiations between the United States, Canada, and Mexico. Either would make an interesting research paper, but they are different topics.

Although the subject matter and analysis are decidedly different in the humanities, many of the same considerations still apply to topic selection. In English or comparative literature, for example, you may be attracted to a very specific topic such as several poems by William Wordsworth. You are not trying, as a social scientist would, to test some generalizations that apply across time or space. Rather, you want to analyze these specific poems, uncover their multiple meanings, trace their allusions, and understand their form and beauty.

As part of the research paper, however, you may wish to say something bigger, something that goes beyond these particular poems. That might be about Wordsworth’s larger body of work. Are these poems representative or unusual? Do they break with his previous work or anticipate work yet to come? You may wish to comment on Wordsworth’s close ties to his fellow “Lake Poets,” Coleridge and Southey, underscoring some similarities in their work. Do they use language in shared ways? Do they use similar metaphors or explore similar themes? You may even wish to show how these particular poems are properly understood as part of the wider Romantic movement in literature and the arts. Any of these would connect the specific poems to larger themes.

How to Refine Your Research Paper Topic

One of your professor’s or instructor’s most valuable contributions to the success of your research paper is to help you refine your topic. She can help you select the best cases for detailed study or the best data and statistical techniques. S/he can help you find cases that shed light on larger questions, have good data available, and are discussed in a rich secondary literature. She may know valuable troves of documents to explore. That’s why it is so important to bring these issues up in early meetings. These discussions with your instructor are crucial in moving from a big but ill-defined idea to a smart, feasible topic.Some colleges supplement this advising process by offering special workshops and tutorial support for students. These are great resources, and you should take full advantage of them. They can improve your project in at least two ways.

First, tutors and workshop leaders are usually quite adept at helping you focus and shape your topic. That’s what they do best. Even if they are relatively new teachers, they have been writing research papers themselves for many years. They know how to do it well and how to avoid common mistakes. To craft their own papers, they have learned how to narrow their topics, gather data, interpret sources, and evaluate conjectures. They know how to use appropriate methods and how to mine the academic literature. In all these ways, they can assist you with their own hard-won experience. To avoid any confusion, just make sure your instructor knows what advice you are getting from workshop leaders and tutors. You want everyone to be pulling in the same direction.

Second, you will benefit enormously from batting around your research paper in workshops. The more you speak about your subject, the better you will understand it yourself. The better you understand it, the clearer your research and writing will be. You will learn about your project as you present your ideas; you will learn more as you listen to others discuss your work; and you will learn still more as you respond to their suggestions. Although you should do that in sessions with your instructor, you will also profit from doing it in workshops and tutorial sessions.

Secrets to Keep in Mind when Writing a Research Paper