Wilderness, settlement, American identity

Cole feared for the American landscape as his country expanded westward

Test your knowledge with a quiz

Cole, hunter's return.

- White Americans used the concept of Manifest Destiny to justify the westward expansion of the United States in the 19th century. Increased white settlement and industry transformed the landscape of the American frontier.

- Cole sought to represent the sublime grandeur of the American landscape. The painting represents his conflicted feelings over the inevitable loss of wilderness that accompanied economic development.

- Cole was one of the first environmentalists. He shared the notion, popular in the early 19th century, that God’s divine presence was embodied in nature, and saw the American wilderness as central to the nation’s identity.

- Cole is credited as the founder of the Hudson River School , which is often described as the first style of painting to be considered American.

“The seemingly untouched quality of the nation’s wilderness distinguished the United States from Europe. The landscape came increasingly to embody what Americans most valued in themselves: an “unstoried” past, and “Adamic” freedom, an openness to the future, a fresh lease on life. In time, Americans came to think of themselves as “nature’s nation.” And yet one of the paradoxes of American history…lay in the unresolved tension between the subduing of the wilderness and the honoring of it. The tension is still alive with us today, in the competing voices of environmentalists and advocates of development.”

— Angela L. Miller, Janet Catherine Berlo, Bryan J. Wolf, and Jennifer L. Roberts, American Encounters: Art, History, and Cultural Identity (Washington University Libraries, 2018), p. 24 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

An unresolved tension

For much of the nineteenth century, America’s landscape was intimately connected with the nation’s identity (unlike Europe, nature in North America was seen as untouched by the hand of man). But the United States has also always prided itself on its entrepreneurial spirit, its economic progress, and its industry. This tension between the nation’s natural beauty and the inevitable expansion of industry was clearly felt in the mid-nineteenth century as logging, mining, railroads, and factories were quickly diminishing what once seemed an endless wilderness. Thomas Cole (1801-48) beautifully expressed the tension between these two American ideals in many of his landscape paintings.

Thomas Jefferson had envisioned that American democracy would be sustained by a nation of yeoman farmers who worked small farms with their families—such as the household pictured by Cole. By the end of 19th century, however, manufacturing had became a primary driver of the American economy.

The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 linked midwestern farms with cities on the east coast. Tanneries (where animal hides were processed to make leather using tannin, which was derived from hemlock trees) proliferated and lumber merchants deforested the landscape. As many as 70 million eastern hemlock trees were cut down to provide tannin. Beginning in the 1830s, the railroad had begun to cut across the American landscape, allowing for easier transportation of goods and passengers.

As the east coast grew increasingly populous and developed, more people moved westward in search of economic opportunity. The Homestead Acts were a series of laws enacted in 1862 to provide 160-acre lots of land at low cost, to encourage settlers to move west, answering Manifest Destiny’s [popup] call for westward expansion (the term was coined in 1845, the year this painting was made). Importantly, the popular conception of the west as unspoiled territory ignored the many nations of American Indians who had already settled the North American continent.

Cole’s painting

Though Cole’s The Hunter’s Return features human figures, it was seen as a landscape painting, since nature is dominant. In the art academies of Europe landscapes were not accorded the same respect as history paintings (whose subjects came from history, the bible or mythology, and therefore had clear moral elements and treated noble subjects), but Cole was intent on elevating his landscapes by imbuing them with a more serious message.

At first glance, a viewer might assume that this painting is set in the Catskill Mountains in the Hudson River Valley in New York State where Cole lived and painted, but in fact this painting is a composite of many scenes, and promotes a specific point of view—one that is ambivalent about the ways that Americans were rapidly transforming the natural beauty that was so fundamental to the nation’s understanding of itself. The foreground of the painting juxtaposes the tree stumps left by man’s axe against the more pristine wilderness seen in the middle and background of the painting.

Cole’s image then is not real, but nostalgic. The artist gave voice to the longing for a pristine, pre-industrial America. Cole wrote,

“I cannot but express my sorrow that the beauty of such landscapes are quickly passing away. The ravages of the axe are daily increasing. The most noble scenes are made desolate, and oftentimes with a wantonness and barbarism scarcely credible in a civilized nation. This is a regret rather than a complaint. Such is the road society has to travel.” — Thomas Cole, “Essay on American Scenery,” The American Monthly Magazine , vol. 7, January 1836, p. 12 .

Learn more about this painting from the Amon Carter Museum

Who was Thomas Cole?

Read Thomas Cole’s “An Essay on American Scenery”

Learn about Cole and the other painters in the Hudson River School

Learn about the impact of tanneries on the landscape of the Catskill mountains

How did the Erie canal impact the development of the midwest?

More to think about

Compare Cole’s The Hunter’s Return with John Gast’s American Progress. Discuss how these works suggest different perspectives on westward expansion of the United States in the 19th century.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”ColeAmon,”]

More Smarthistory images…

Find this video in...

Seeing america.

- Theme: National Identity

- Period: 1800 - 1848

- Topic: The frontier, Manifest Destiny, and the American West

Art histories

- Thomas Cole, The Hunter's Return

Teaching guides

- Teaching guide for The Hunter's Return

- All teaching guides

Explore the diverse history of the United States through its art. Seeing America is funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art and the Alice L. Walton Foundation.

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

Support 110 years of independent journalism.

The greats outdoors: How Thomas Cole shaped the American landscape

Why Cole’s wounded pride helped inspire a national school of painting.

By Michael Prodger

The origins of what has come to be adopted as the US’s national landscape painting lie not in natural beauty but in wounded pride. In 1829 Captain Basil Hall, an English traveller and veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, published Travels in North America in the Years 1827 and 1828 . The snooty observations it contained – on American life, manners, government and topography – caused a transatlantic furore. Hall’s disobliging comments about the young nation included the suggestions that Americans were spittoon-using parvenus obsessed with money, and that not only were they rough around the edges but their political and cultural institutions were inferior to those of Europe. To add insult to injury, someone who hosted Captain Hall and his wife during their trip recalled that Mrs Hall also “indulged herself in certain criticisms upon the American ladies”.

Those Americans were not a people subject to the cultural cringe or willing to be patronised by a scion of the Old World, and Hall’s book prompted numerous outraged responses in the press and even in books: the sense of hurt continued to sting for a decade. One of Hall’s criticisms, however, bore fruit. “Where the fine arts are not steadily cultivated,” he had observed, “there cannot possibly be much hearty admiration of the beauties of nature.” This affront to American sensibility was seen as a challenge and one painter in particular took it up.

Ironically, the artist was English-born. Thomas Cole (1801-48) came from Lancashire and moved to the US with his family in 1818. As a naturalised citizen he was instrumental in founding the Hudson River School, a group of landscape painters who took the river valley and its scenes – boatmen and hunters, waterfalls and weather – as their theme, and who formed the nation’s first indigenous school of repute.

In 1836 Cole published his “ Essay on American Scenery”, which was, in part, a riposte to Hall. In it he lauded his adopted land, pointing out that its landscapes offered not just the sublime but also the picturesque and the beautiful – three themes that had been an important part of artistic discourse in Europe since the mid-18th century. What’s more, he said, American landscapes were all the better for not being burdened by associations with ancient civilisations. “You see no ruined tower to tell of outrage,” he wrote, “no gorgeous temple to speak of ostentation; but freedom’s offspring – peace, security and happiness dwell there, the spirits of the scene.” As he hit his stride his prose turned bright purple: “And in looking over the yet uncultivated scene, the mind’s eye may see far into futurity – mighty deeds shall be done in the now pathless wilderness; and poets yet unborn shall sanctify the soil.” One in the eye for the Old World.

The Saturday Read

Morning call, events and offers, the green transition.

- Administration / Office

- Arts and Culture

- Board Member

- Business / Corporate Services

- Client / Customer Services

- Communications

- Construction, Works, Engineering

- Education, Curriculum and Teaching

- Environment, Conservation and NRM

- Facility / Grounds Management and Maintenance

- Finance Management

- Health - Medical and Nursing Management

- HR, Training and Organisational Development

- Information and Communications Technology

- Information Services, Statistics, Records, Archives

- Infrastructure Management - Transport, Utilities

- Legal Officers and Practitioners

- Librarians and Library Management

- OH&S, Risk Management

- Operations Management

- Planning, Policy, Strategy

- Printing, Design, Publishing, Web

- Projects, Programs and Advisors

- Property, Assets and Fleet Management

- Public Relations and Media

- Purchasing and Procurement

- Quality Management

- Science and Technical Research and Development

- Security and Law Enforcement

- Service Delivery

- Sport and Recreation

- Travel, Accommodation, Tourism

- Wellbeing, Community / Social Services

That same year Cole gave a painted rejoinder to Hall too, ponderously titled View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm , but better known as The Oxbow , and now in the Met in New York City. Mount Holyoke was a popular 19th-century tourist destination, some 145km west of Boston, overlooking the Connecticut river, that offered long-reaching views of the New England landscape (even Hall admired its vistas, despite the ginger-beer seller and fake hermit who could be found at the peak). Cole, however, treated it as both a literal and an allegorical place.

He came to the painting in the middle of working on his epic Course of Empire series, which showed the rise, peak and fall of a classical civilisation. His patron, the dry goods plutocrat Luman Reed, saw that work on the five paintings was wearing Cole down and suggested he try something else. Indeed, Cole had previously confessed in his diary that “my mind has been occupied with so many cares & anxieties, sickness of my Mother & Father etc, & so many interruptions that it has not been in proper tone for pursuing my profession”. He felt he was being sidelined by younger painters and that “my best days are passing away without being able to apply talents I possess so entirely to my art as I should wish”.

Cole had made sketches of the view in 1833 and for his painting he conflated a broader panorama and then, on a canvas nearly six feet wide, divided it diagonally in two. In one portion he showed wild nature – a storm tail passing overhead, leaving broken tree trunks and twisted foliage in its wake. In the other portion, beyond the glistening oxbow bend of the river, he showed an American Arcadia, all neatly tended fields, careful husbandry, peace and prosperity. Here is the futurity he spoke of and here, too, the idea of “manifest destiny” made real: Americans could and should tame the wilderness and shepherd it to civilisation.

Cole himself perhaps felt some ambiguity about the relentless recasting of the American landscape. The hill in the background bears logging scars that form the shapes of Hebrew words: one reads “Noah”, the other “Shaddai” – the Almighty. What is not altogether clear in this Eden is whether God is looking down approvingly on man’s work. There may be a boat and a barge on the river and farms on the plain, but there is only one human to be seen; it is a self- portrait of Cole at his easel, almost lost in the foreground undergrowth, as he fixes this moment of national transition in paint.

Cole has painted a series of contrasts: past and future, wild and temperate, innocence and experience, the sublime and the beautiful. There is a sense, too, that he knew how precariously balanced all these elements were. In his Course of Empire paintings he showed what fate had in store for an overreaching civilisation.

The painting met with great acclaim when it was exhibited and he pocketed a very welcome $500 for his trouble. What it proved, however, was that American artists could depict their own land in ways unbeholden to the European tradition. Intriguingly, X-rays reveal that beneath the paint of The Oxbow lies the outline of a quite different picture, one containing ranks of classical buildings. In making a distinctively American art, Cole quite literally overpainted all traces of the Old World. Basil Hall, meanwhile, suffered mental illness in later life and was confined to an asylum in Plymouth, dying eight years after The Oxbow appeared.

Content from our partners

How can we deliver better rail journeys for customers?

The promise of prevention

How Labour hopes to make the UK a leader in green energy

Why men shouldn’t control artificial intelligence

Germany and its discontents

Sahra Wagenknecht’s plan for peace

This article appears in the 13 May 2020 issue of the New Statesman, Land of confusion

- OH&S, Risk Management

"The soul of all scenery": Thomas Cole's Clouds

Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848). View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow (detail), 1836. Oil on canvas, 51 1/2 x 76 in. (130.8 x 193 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1908 (08.228)

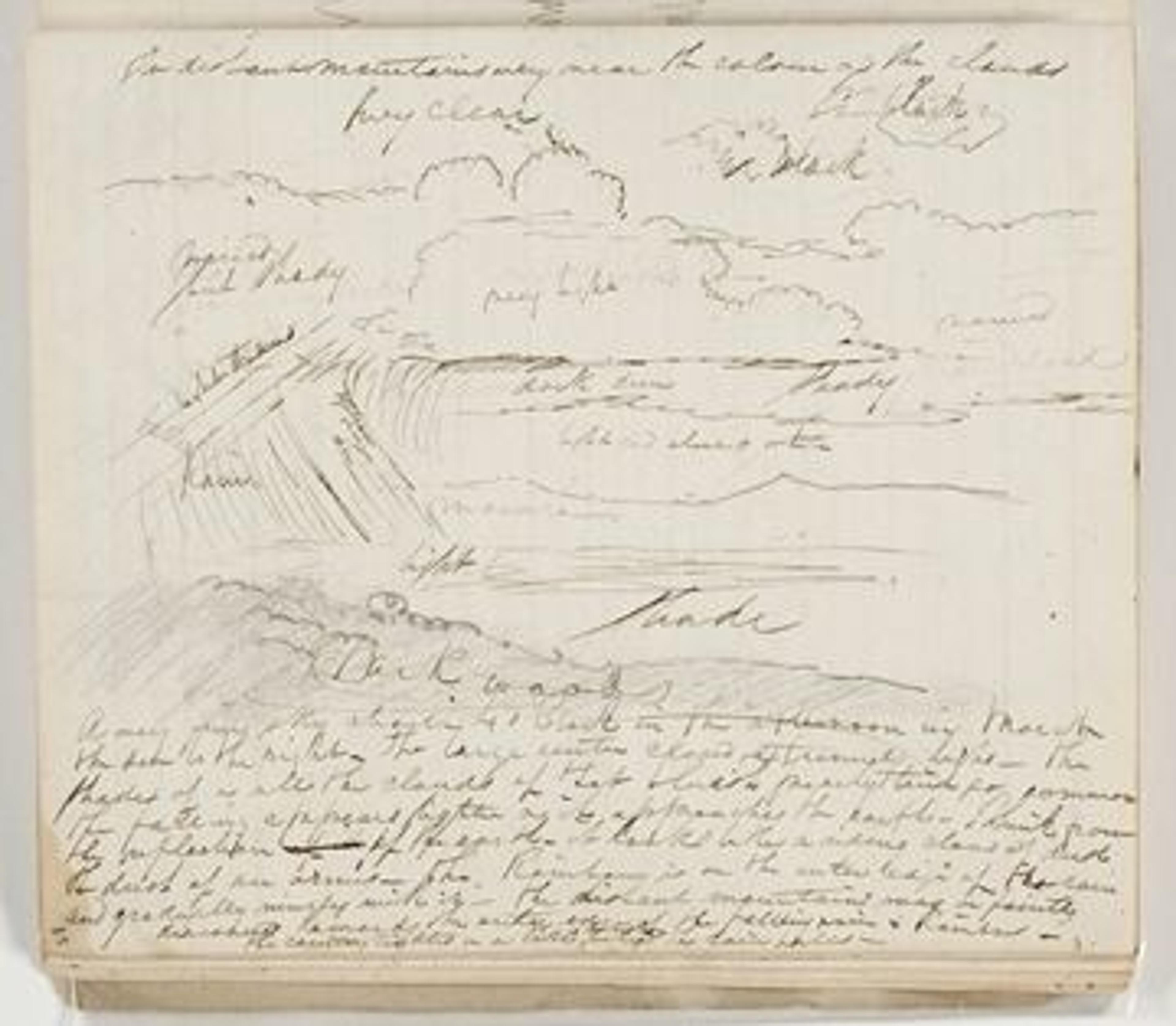

Thomas Cole—the subject of a recently closed exhibition at The Met , traveling soon to The National Gallery, London —studied, sketched, and painted clouds throughout his career. As early as 1825, he copied in his notebook the formula for painting skies found in William Oram's Precepts and Observations on the Art of Colouring in Landscape Painting (1810), and his notebooks are filled with written empirical observations as well as graphite on-site studies of clouds, such as Atmospheric Study with Notations , which he inscribed, "Thunderstorm after Sunset."

Left: Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848). Atmospheric Study with Notations , ca. 1825. Pen and brown ink over graphite pencil on off-white wove paper, sheet: 6 1/2 x 7 5/8 in. (16.5 x 19.4 cm). Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase, William H. Murphy Fund (39.681.24)

While in London from 1829 to 1831 , Cole was exposed to the grand-scale canvases that included dramatic cloud effects as well as the on-site, or plein-air, cloud studies of Joseph Mallord William Turner and John Constable. On a visit to the Royal Academy on June 29, 1829, for example, Cole saw Constable's Hadleigh Castle, The Mouth of the Thames—Morning after a Stormy Night , which he greatly admired and which features a dramatic cloud-filled sky.

John Constable (British, 1776–1837). Hadleigh Castle, The Mouth of the Thames—Morning after a Stormy Night , 1829. Oil on canvas, 48 x 64 3/4 in. (121.9 x 164.5 cm). Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Paul Mellon Collection (B1977.14.42)

Cole met Constable later that year and had the opportunity to view Constable's oil studies. Constable had studied meteorological treatises and, working directly from nature, produced a series of now-celebrated cloud studies in the 1820s, including such examples as Rainstorm over the Sea and Study of a Cloudy Sky .

Left: John Constable (British, 1776–1837). Rainstorm over the Sea , ca. 1824–28. Oil on paper laid on canvas, 9 1/4 x 12 7/8 in. (23.5 x 32.6 cm). Royal Academy of Arts, London, Given by Isabel Constable, 1888 (03/1390). Right: John Constable (British, 1776–1837). Study of a Cloudy Sky , ca. 1825. Oil on paper on millboard, 10 3/8 x 13 in. (26.4 x 33 cm). Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Paul Mellon Collection (B1981.25.124)

In a famous letter penned October 1821, Constable wrote:

I have done a great deal of skying. . . . That landscape painter who does not make his sky a very material part of his composition, neglects to avail himself of one of his greatest aids. . . . It will be difficult to name a class of landscape in which the sky is not the key-note, the standard of scale, and the chief organ of sentiment.

Cole, in his famous " Essay on American Scenery " of 1836, echoed Constable's sentiment, writing that the sky is "the soul of all scenery, in it are the fountains of light, and shade, and color," and declaring that "for variety and magnificence, American skies are unsurpassed."

As a keen observer of weather conditions, Cole used the sky in such major works as The Met's View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow to convey the central narrative and "soul" of the painting. His storm-filled sky, or swirling vortex of clouds, was directly inspired by Turner's Snow Storm: Hannibal and His Army Crossing the Alps , which he had greatly admired while visiting the artist's London studio in 1831.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (British, 1775–1851). Snow Storm: Hannibal and His Army Crossing the Alps , exhibited 1812. Oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 93 1/2 in. (146 x 237.5 cm). Tate Britain, London, Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856 (N00490)

Cole eventually mastered the pure cloud study, including the fine example Clouds from The Met collection. Here, the palpable brushstrokes suggest the immediacy of the artist's perceptions. His handling of color is subtle: the lower section of the towering cloud formation is gray, gray-purple, and gray-white, while the upper portion tends toward pure bright white. Inspired by Constable's cloud studies, Cole included a line of treetops at the lower edge of the composition to establish a sense of scale.

Left: Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848). Clouds , ca. 1830s. Oil on paper laid down on canvas, 8 3/4 x 10 7/8 in. (22.2 x 27.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Morris K. Jesup Fund, 2013 (2013.201). Right: Frederic Edwin Church (American, 1826–1900). Sunset across the Hudson Valley , 1870. Oil and graphite on paperboard, 11 1/8 x 15 1/4 in. (28.3 x 38.7 cm). Copper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, Gift of Louis P. Church (1917-4-582-a)

This study, and others by Cole, may well have been seen by young Frederic Edwin Church during his two-year instruction with Cole, in his Catskill studio from 1844 to 1846, when Cole directly taught Church the art of plein-air painting. Church would go on to paint his own scientifically observed cloud studies, including Sunset across the Hudson Valley , a work that looks southwest across the Hudson River toward Cedar Grove, Cole's home and studio where Church first learned the art of painting clouds.

Related Content

Thomas Cole's Journey: Atlantic Crossings was on view at The Met Fifth Avenue January 30–May 13, 2018.

Read a blog series about Thomas Cole on Now at The Met .

See more digital content related to Thomas Cole, including a walkthrough of the recent exhibition .

The exhibition catalogue is available for purchase in The Met Store .

Elizabeth Kornhauser

Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser is the Alice Pratt Brown Curator of American Paintings and Sculpture in The American Wing.

- No results found

Essay on American Scenery Thomas Cole

The American Monthly Magazine 1 (January 1836) [I. Introduction]

The essay, which is here offered, is a mere sketch of an almost illimitable subject-- American Scenery; and in selecting the theme the writer placed more confidence in its overflowing richness, than in his own capacity for treating it in a manner worthy of its vastness and importance.

It is a subject that to every American ought to be of surpassing interest; for, whether he beholds the Hudson mingling waters with the Atlantic--explores the central wilds of this vast continent, or stands on the margin of the distant Oregon, he is still in the midst of American scenery--it is his own land; its beauty, its magnificence, its sublimity--all are his; and how undeserving of such a birthright, if he can turn towards it an unobserving eye, an unaffected heart!

Before entering into the proposed subject, in which I shall treat more particularly of the scenery of the Northern and Eastern States, I shall be excused for saying a few words on the advantages of cultivating a taste for scenery, and for exclaiming against the apathy with which the beauties of external nature are regarded by the great mass, even of our refined community.

[1. The Contemplation of Scenery as a Source of Delight and Improvement]

It is generally admitted that the liberal arts tend to soften our manners; but they do more-- they carry with them the power to mend our hearts.

Poetry and Painting sublime and purify thought, by grasping the past, the present, and the future--they give the mind a foretaste of its immortality, and thus prepare it for

performing an exalted part amid the realities of life. And rural nature is full of the same quickening spirit--it is, in fact, the exhaustless mine from which the poet and the painter have brought such wondrous treasures--an unfailing fountain of intellectual enjoyment, where all may drink, and be awakened to a deeper feeling of the works of genius, and a keener perception of the beauty of our existence. For those whose days are all consumed in the low pursuits of avarice, or the gaudy frivolities of fashion, unobservant of nature's loveliness, are unconscious of the harmony of creation--

Heaven's roof to them

Is but a painted ceiling hung with lamps; No more--that lights them to their purposes-- They wander 'loose about;' they nothing see, Themselves except, and creatures like themselves,

What to them is the page of the poet where he describes or personifies the skies, the mountains, or the streams, if those objects themselves have never awakened observation or excited pleasure? What to them is the wild Salvator Rosa, or the aerial Claude Lorrain? There is in the human mind an almost inseparable connection between the beautiful and the good, so that if we contemplate the one the other seems present; and an excellent author has said, "it is difficult to look at any objects with pleasure--unless where it arises from brutal and tumultuous emotions--without feeling that disposition of mind which tends towards kindness and benevolence; and surely, whatever creates such a disposition, by increasing our pleasures and enjoyments, cannot be too much cultivated."

It would seem unnecessary to those who can see and feel, for me to expatiate on the loveliness of verdant fields, the sublimity of lofty mountains, or the varied magnificence of the sky; but that the number of those who seek enjoyment in such sources is

comparatively small. From the indifference with which the multitude regard the beauties of nature, it might be inferred that she had been unnecessarily lavish in adorning this world for beings who take no pleasure in its adornment. Who in grovelling pursuits forget their glorious heritage. Why was the earth made so beautiful, or the sun so clad in glory at his rising and setting, when all might be unrobed of beauty without affecting the insensate multitude, so they can be "lighted to their purposes?"

It has not been in vain--the good, the enlightened of all ages and nations, have found pleasure and consolation in the beauty of the rural earth. Prophets of old retired into the solitudes of nature to wait the inspiration of heaven. It was on Mount Horeb that Elijah witnessed the mighty wind, the earthquake, and the fire; and heard the "still small voice"- -that voice is YET heard among the mountains! St. John preached in the desert;--the wilderness is YET a fitting place to speak of God. The solitary Anchorites of Syria and Egypt, though ignorant that the busy world is man's noblest sphere of usefulness, well knew how congenial to religious musings are the pathless solitudes.

He who looks on nature with a "loving eye," cannot move from his dwelling without the salutation of beauty; even in the city the deep blue sky and the drifting clouds appeal to him. And if to escape its turmoil--if only to obtain a free horizon, land and water in the play of light and shadow yields delight--let him be transported to those favored regions, where the features of the earth are more varied, or yet add the sunset, that wreath of glory daily bound around the world, and he, indeed, drinks from pleasure's purest cup. The delight such a man experiences is not merely sensual, or selfish, that passes with the occasion leaving no trace behind; but in gazing on the pure creations of the Almighty, he feels a calm religious tone steal through his mind, and when he has turned to mingle with his fellow men, the chords which have been struck in that sweet communion cease not to vibrate.

In what has been said I have alluded to wild and uncultivated scenery; but the cultivated must not be forgotten, for it is still more important to man in his social capacity--

bosoms mingled with a thousand domestic affections and heart-touching associations-- human hands have wrought, and human deeds hallowed all around.

And it is here that taste, which is the perception of the beautiful, and the knowledge of the principles on which nature works, can be applied, and our dwelling-places made fitting for refined and intellectual beings.

[2. The Advantages of Cultivating a Taste for Scenery]

If, then, it is indeed true that the contemplation of scenery can be so abundant a source of delight and improvement, a taste for it is certainly worthy of particular cultivation; for the capacity for enjoyment increases with the knowledge of the true means of obtaining it. In this age, when a meager utilitarianism seems ready to absorb every feeling and

sentiment, and what is sometimes called improvement in its march makes us fear that the bright and tender flowers of the imagination shall all be crushed beneath its iron tramp, it would be well to cultivate the oasis that yet remains to us, and thus preserve the germs of a future and a purer system. And now, when the sway of fashion is extending widely over society--poisoning the healthful streams of true refinement, and turning men from the love of simplicity and beauty, to a senseless idolatry of their own follies--to lead them gently into the pleasant paths of Taste would be an object worthy of the highest efforts of genius and benevolence. The spirit of our society is to contrive but not to enjoy--toiling to produce more toil-accumulating in order to aggrandize. The pleasures of the imagination, among which the love of scenery holds a conspicuous place, will alone temper the

harshness of such a state; and, like the atmosphere that softens the most rugged forms of the landscape, cast a veil of tender beauty over the asperities of life.

Did our limits permit I would endeavor more fully to show how necessary to the

complete appreciation of the Fine Arts is the study of scenery, and how conducive to our happiness and well-being is that study and those arts; but I must now proceed to the proposed subject of this essay--American Scenery!

[II. The Elements of American Scenery]

There are those who through ignorance or prejudice strive to maintain that American scenery possesses little that is interesting or truly beautiful--that it is rude without

picturesqueness, and monotonous without sublimity--that being destitute of those vestiges of antiquity, whose associations so strongly affect the mind, it may not be compared with European scenery. But from whom do these opinions come? From those who have read of European scenery, of Grecian mountains, and Italian skies, and never troubled themselves to look at their own; and from those travelled ones whose eyes were never opened to the beauties of nature until they beheld foreign lands, and when those lands faded from the sight were again closed and forever; disdaining to destroy their trans- atlantic impressions by the observation of the less fashionable and unfamed American scenery. Let such persons shut themselves up in their narrow shell of prejudice--I hope

they are few,--and the community increasing in intelligence, will know better how to appreciate the treasures of their own country.

I am by no means desirous of lessening in your estimation the glorious scenes of the old world--that ground which has been the great theater of human events--those mountains, woods, and streams, made sacred in our minds by heroic deeds and immortal song--over which time and genius have suspended an imperishable halo. No! But I would have it remembered that nature has shed over this land beauty and magnificence, and although the character of its scenery may differ from the old world's, yet inferiority must not therefore be inferred; for though American scenery is destitute of many of those circumstances that give value to the European, still it has features, and glorious ones, unknown to Europe.

[1. Wildness]

A very few generations have passed away since this vast tract of the American continent, now the United States, rested in the shadow of primeval forests, whose gloom was peopled by savage beasts, and scarcely less savage men; or lay in those wide grassy plains called prairies--

The Gardens of the Desert, these

The unshorn fields, boundless and beautiful.

And, although an enlightened and increasing people have broken in upon the solitude, and with activity and power wrought changes that seem magical, yet the most distinctive, and perhaps the most impressive, characteristic of American scenery is its wildness. It is the most distinctive, because in civilized Europe the primitive features of scenery have long since been destroyed or modified--the extensive forests that once

overshadowed a great part of it have been felled--rugged mountains have been smoothed, and impetuous rivers turned from their courses to accommodate the tastes and necessities of a dense population--the once tangled wood is now a grassy lawn; the turbulent brook a navigable stream--crags that could not be removed have been crowned with towers, and the rudest valleys tamed by the plough.

And to this cultivated state our western world is fast approaching; but nature is still predominant, and there are those who regret that with the improvements of cultivation the sublimity of the wilderness should pass away: for those scenes of solitude from which the hand of nature has never been lifted, affect the mind with a more deep toned emotion than aught which the hand of man has touched. Amid them the consequent associations are of God the creator--they are his undefiled works, and the mind is cast into the contemplation of eternal things.

[2. Mountains]

It is true that in the eastern part of this continent there are no mountains that vie in altitude with the snow-crowned Alps--that the Alleghanies and the Catskills are in no point higher than five thousand feet; but this is no inconsiderable height; Snowdon in Wales, and Ben-Nevis in Scotland, are not more lofty; and in New Hampshire, which has been called the Switzerland of the United States, the White Mountains almost pierce the region of perpetual snow. The Alleghanies are in general heavy in form; but the Catskills, although not broken into abrupt angles like the most picturesque mountains of Italy, have varied, undulating, and exceedingly beautiful outlines--they heave from the valley of the Hudson like the subsiding billows of the ocean after a storm.

American mountains are generally clothed to the summit by dense forests, while those of Europe are mostly bare, or merely tinted by grass or heath. It may be that the mountains of Europe are on this account more picturesque in form, and there is a grandeur in their nakedness; but in the gorgeous garb of the American mountains there is more than an equivalent; and when the woods "have put their glory on," as an American poet has beautifully said, the purple heath and yellow furze of Europe's mountains are in comparison but as the faint secondary rainbow to the primal one.

But in the mountains of New Hampshire there is a union of the picturesque, the sublime, and the magnificent; there the bare peaks of granite, broken and desolate, cradle the clouds; while the vallies and broad bases of the mountains rest under the shadow of noble and varied forests; and the traveller who passes the Sandwich range on his way to the White Mountains, of which it is a spur, cannot but acknowledge, that although in some regions of the globe nature has wrought on a more stupendous scale, yet she has nowhere so completely married together grandeur and loveliness--there he sees the sublime

melting into the beautiful, the savage tempered by the magnificent. [3. Water]

I will now speak of another component of scenery, without which every landscape is defective--it is water. Like the eye in the human countenance, it is a most expressive feature: in the unrippled lake, which mirrors all surrounding objects, we have the expression of tranquillity and peace--in the rapid stream, the headlong cataract, that of turbulence and impetuosity.

In this great element of scenery, what land is so rich? I would not speak of the Great Lakes, which are in fact inland seas--possessing some of the attributes of the ocean, though destitute of its sublimity; but of those smaller lakes, such as Lake George,

Champlain, Winnipisiogee, Otsego, Seneca, and a hundred others, that stud like gems the bosom of this country. There is one delightful quality in nearly all these lakes--the purity and transparency of the water. In speaking of scenery it might seem unnecessary to mention this; but independent of the pleasure that we all have in beholding pure water, it is a circumstance which contributes greatly to the beauty of landscape; for the reflections

of surrounding objects, trees, mountains, sky, are most perfect in the clearest water; and the most perfect is the most beautiful.

I would rather persuade you to visit the "Holy Lake," the beautiful "Horican," than attempt to describe its scenery--to behold you rambling on its storied shores, where its southern expanse is spread, begernmed with isles of emerald, and curtained by green receding hills--or to see you gliding over its bosom, where the steep and rugged

mountains approach from either side, shadowing with black precipices the innumerable islets--some of which bearing a solitary tree, others a group of two or three, or a "goodly company," seem to have been sprinkled over the smiling deep in Nature's frolic hour. These scenes are classic--History and Genius have hallowed them. War's shrill clarion once waked the echoes from these now silent hills--the pen of a living master has portrayed them in the pages of romance--and they are worthy of the admiration of the enlightened and the graphic hand of Genius.

Though differing from Lake George, Winnipisiogee resembles it in multitudinous and uncounted islands. Its mountains do not stoop to the water's edge, but through varied screens of forest may be seen ascending the sky softened by the blue haze of distance--on the one hand rise the Gunstock Mountains; on the other the dark Ossipees, while above and far beyond, rear the "cloud capt" peaks of the Sandwich and White Mountains. I will not fatigue with a vain attempt to describe the lakes that I have named; but would turn your attention to those exquisitely beautiful lakes that are so numerous in the Northern States, and particularly in New Hampshire. In character they are truly and peculiarly American. I know nothing in Europe which they resemble; the famous lakes of Albano and Nemi, and the small and exceedingly picturesque lakes of Great Britain may be compared in size, but are dissimilar in almost every other respect. Embosomed in the primitive forest, and sometimes overshadowed by huge mountains, they are the chosen places of tranquillity; and when the deer issues from the surrounding woods to drink the cool waters, he beholds his own image as in a polished mirror,--the flight of the eagle can be seen in the lower sky; and if a leaf falls, the circling undulations chase each other to the shores unvexed by contending tides.

There are two lakes of this description, situated in a wild mountain gorge called the Franconia Notch, in New Hampshire. They lie within a few hundred feet of each other, but are remarkable as having no communication--one being the source of the wild

Amonoosuck, the other of the Pemigiwasset. Shut in by stupendous mountains which rest on crags that tower more than a thousand feet above the water, whose rugged brows and shadowy breaks are clothed by dark and tangled woods, they have such an aspect of deep seclusion, of utter and unbroken solitude, that, when standing on their brink a lonely traveller, I was overwhelmed with an emotion of the sublime, such as I have rarely felt. It was not that the jagged precipices were lofty, that the encircling woods were of the dimmest shade, or that the waters were profoundly deep; but that over all, rocks, wood, and water, brooded the spirit of repose, and the silent energy of nature stirred the soul to its inmost depths.

I would not be understood that these lakes are always tranquil; but that tranquillity is their great characteristic. There are times when they take a far different expression; but in scenes like these the richest chords are those struck by the gentler hand of nature. [b. Waterfalls]

And now I must turn to another of the beautifiers of the earth--the Waterfall; which in the

- Essay on American Scenery Thomas Cole (You are here)

Related documents

Essay on American Scenery

Moundbuilders' Art

Output Formats

Copy the code below into your web page

Proudly powered by Omeka .

Early American Lit and Culture, Fall 2014

A middlebury blog, thomas cole.

Why does Cole think it is important to observe and paint American scenery? How does he think nature and humans should interact? How does one painting depict (or fail to depict) the ideals he discusses in his essay?

9 thoughts on “ Thomas Cole ”

As others have noted, Cole places much emphasis on the exceptionalism of the untouched American landscape, where one can witness “the sublime melting into the beautiful.” He praises the deeply emotional and spiritual connection that such scenery encourages, for it is not symbolic of man’s history, but of a solely divinely altered past. Interestingly, far from encouraging the preservation of this unadulterated landscape, Cole states that the “cultivated state of our western world is fast approaching,” without suggestion of a call to action to prevent it. In this way, Cole’s Course of Empire paintings seem to suggest a necessary path dependency of the building of civilization that America will soon follow. He does not however, see the ruin of such as inevitable. While Cole’s hope for the future does not appear to be in natural preservation, he instead seeks to build American “historical and legendary associations” through newly manipulated landscape that are marked not by destruction or desolation, as Europe has been, but instead by “peace, security and happiness.”

Thomas Cole makes many points about why American scenery should be recorded. His opening point about the American landscape is that the land belongs to everyone. No matter if you are looking on the river or in the mountains, the American Landscape is the land of Americans. Cole writes, “For wether he beholds the Hudson mingling waters with the Atlantic – explores the central wilds of this vast continent, or stands on the margin of the distant Oregon, he is still in the midst of American scenery – it is his own land” (98). The beauty and magnificence of the land belongs to the American people, and they should embrace it. Cole does not discredit the beauty of European lands, he simply acknowledges that the two sceneries are different. The lands of Europe lack the primitiveness and untouched forests and landscapes, whereas American scenery remains untouched. I especially like when Cole mentions the “one season when the American forest surpasses all the world in gorgeousness – that is the autumnal; then every hill and dale is riant in the luxury of color”. Cole is admirable about the landscape and highlights many points about the value of the American landscape in art. The painting “Daniel Boone and His Cabin”, depicts Cole’s exact thoughts about the American Landscape. Boone is sitting at his home and behind him is a vast and unexplored landscape of grand mountains and deep waters. This type of scene would not exist in Europe anymore.

Thomas Cole views American scenery as a source of joy and consolation. He writes of the tranquility, peace and transparency of water as well as other beautifiers of the earth including the forest scenery, hills, and sky. He challenges those that view American scenery as inferior to European scenery by asserting that it has magnificent features no longer present in Europe. He writes that features such as “extensive forests, felled-rugged mountains, tangled wood, and turbulent brooks” – features abundant in American scenery – no longer exist in Europe due its “cultivated state”and consequently take away from its magnificence (102). Cole believes that humans should view nature as an “escape from the ordinary pursuits of life” and as a place for emotional reflection and enjoyment (109).

I disagree with the general assertion of the previous comments that Cole believes Americans should consider the wild landscape greater than themselves, and work to preserve it just for its own sake. In my view, Cole’s primary appreciation of wilderness is for its impact on the American consciousness, and the way in which interaction with one’s environment can lead to the formation of a new national ethic. This ethic, embodied by frontier men like Daniel Boone, is what serves to radically distinguish America from its European roots, providing the seed of the concept of “American exceptionalism” (“the theory that the United States is qualitatively different from other nation states” –Wikipedia) that is still ubiquitous in American politics and culture.

Though European observers may look view American scenery as “less fashionable and unframed” (101), they overlook the land’s “unbounded capacity for improvement by art” (106). These artificial improvements are desirable because they will be a reflection of the people that will carve out a new nation in the wilderness. One of the huge differences between European and American landscapes is the “want of associations” (108) that stems from America’s comparatively short history as a “civilized nation.” Cole may believe nature can be sublime on its own, but he also writes that “he who stands on the mounds of the West…may experience the emotion of the sublime, but it is the sublimity of the shoreless ocean un-islanded by the recorded deeds of man” (ibid.). Already, Cole looks for ways in which the landscape has been “sanctified,” or made more meaningful by some important human deed, and he finds ample sanctification in the memory of the Revolution, which also goes hand-in-hand with the notion of exceptionalism. One might argue that Cole decries artificial corruption of the wilderness when he laments the “ravages of the axe” (109), but as the painter himself notes, “this is a regret rather than a complaint” (ibid.), because such actions are necessary for the advance of society. He hopes that nature’s beauty is not mindlessly destroyed and left desolate, but rather artfully cultivated in the name of taste. While it is arguable that Cole would like to see large tracts of land preserved for the sake of their aesthetic/spiritual beauty, he gives at least equal weight to the wilderness as blank canvas that will inspire the unfolding drama of American nationhood.

Cole thinks it is important to observe and paint American scenery, rural nature, because one becomes awakened to the deeper feeling of the works of God and the beauty of one’s existence in America. Cole believes that the observation of scenery is a source of delight and improvement for man. He believes that while looking upon the work of God, one “feels a calm religious tone seal through his mind, and when he has turned to mingle with his fellow men, the chords have been struck in that sweet communion cease not to vibrate” (100). Also, Cole speaks to those with a prejudice of pro-European scenery from reading. This is another reason why Cole believes in the power of observing scenery. He believes that these ignorant people have never had their eyes opened to the beauties of God’s creation, and they have not found pleasure in the beauty of rural earth before the beauty faded from the sight and was closed forever.

The exceptionalism of American nature, Cole believes, is its wilderness, which though approaching levels of English civilization still possesses a distance from humankind’s touch that allows for more significant spiritual and emotional reflection. Citing widespread forests, crystalline rivers and majestic mountains which implicitly invoke the wonder of God’s creation to the viewer, Cole notes every American’s birthright and duty to revel in their unique landscape. Perception of American nature through poetry and painting creates an “intellectual enjoyment,” “deeper feeling,” and “keener perception” of the world for the viewer, and Cole warns against the distractions of utilitarianism and increasingly popular man made creations like fashion, arguing that the simple contemplation of scenery delights and improves the mind in a way that extends to every facet of life, therefore improving the benevolence of men and the conditions of society. Painting, then, is a method of preserving this American wilderness and allowing future generations to experience the spiritual and emotional benefits of viewing a natural world which Cole knows may change rapidly over time. The future road to refinement, Cole believes, is paved with “improvements” that will forever alter the current landscape of the wilderness. In a painting like Home in the Woods, Cole immortalizes an unrippled lake in which “the reflections of surrounding objects, trees, mountains, sky, are most perfect in the clearest water,” also featuring a lush American forest and formidable mountain range in the background. Most importantly, Cole paints a modest cabin and family living in harmony with the natural splendor, perhaps suggesting to the viewer that this lifestyle – not that of the wealthy or most ‘civilized’ – will most easily lead to enlightenment and social peace.

Cole believes it is important to paint American scenery because he views it as importantly distinct from European landscape and that it offers a glimpse of the human condition compared to the vastness of everything else created by God’s hand. He proposes that being alone in nature, especially the untamed, magnificent, and ‘sublime’ landscape of the (at the time) significantly less developed American wilderness can equate to a kind of religious experience. He asserts that experiencing and comprehending the immense and diverse aspects of beauty that characterize American scenery is an important step for those with “unobserving eyes” and “unaffected hearts” to actually deserve a place surrounded by such overwhelmingly awe-inspiring sights. He cherishes the fact that American landscapes have not been tamed and developed to the extent of European land, insinuating that humans should work to preserve in some way the natural sublimity of the American wilderness. However he also notes the pleasant character of cultivated landscapes as well, revealing a complexity about his attitude regarding tamed versus untamed land. The first two paintings of his Course of Empire aptly represent how Cole renders nature’s beauty in depictions of both wilderness and pastoral lands.

Cole has a very spiritual relationship with nature. Cole said that, “the wilderness is yet a fitting place to speak of God.” Observing and painting American scenery is so important to Cole because he believes that American scenery is an illimitable subject and that Americans are undeserving of it if they do not worship it (painting is very spiritual/a form of worship to Cole).

Thomas Cole sees American scenery as something to be revered with the upmost respect. He worries that people take for granted the earth and its beauty. It is most beautiful when it runs wild, unimpeded by the human race. He discusses the mountains, the waterways, and the forests. While some say it lacks the picturesque qualities of the European landscape, Thomas Cole believes it holds beauties, the likes of which even Europe does not have. Thomas Cole uses the earth and its beauty almost as though it is a metaphor for the people who inhabit it. Although many think it is not attractive in the ways of Europe, he believes its diversity makes it special in ways Europe could never be. From the wilderness to the more cultivated grounds, American scenery finds its greatest appeal in the many ways in which it represents itself. In his painting, “Daniel Boone and His Cabin,” Cole depicts his beliefs in summation. With the heavens shining down warm light from above and the mountains, woods, and lake all melding into one glorious scene, man sits to appreciate the splendor around him. Man does not wish to destroy the majesty, only to become part of it, part of the greater beauty.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

${pageClass}

River in the Catskills

Choose collection.

Explore Thomas Cole

- Interactive Tour

- Virtual Gallery

- Cole's Landscapes

- Definitions

- Cole's Circle

Archival Sources

- Asher B. Durand Papers, 1812-1886, Manuscripts and Archives, New York Public Library, New York, N.Y.

- Luman Reed Papers, 1820-1895, New-York Historical Society Mss Collection.

- Thomas Cole, Catskill Sketchbook, Prints and Drawings Department, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- Thomas Cole Papers, 1821-1863, Manuscripts and Special Collections, New York State Library (NYSL), Albany, N.Y.

- Thomson-Cole papers, Greene County Historical Society, Coxsackie, N.Y.

Published Sources

- Anderson, Patricia. The Course of Empire: The Erie Canal and the New York Landscape, 1825-1875. Rochester: Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, 1984.

- Avery, Kevin J. and Franklin Kelly, eds. Hudson River School Visions: The Landscapes of Sanford R. Gifford. Assisted by Claire A. Conway, with essays by Heidi Applegate and Eleanor Jones Harvey. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

- Baigell, Matthew. Thomas Cole. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1981.

- Bedell, Rebecca Bailey. The Anatomy of Nature: Geology and American Landscape Painting, 1825-1875. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- Civosky, Nikolai Jr. "The Ravages of the Axe: The Meaning of the Tree Stump in Nineteenth-Century Art," Art Bulletin 61 (1979): 611-626.

- Cole, Thomas. The Collected Essays and Prose Sketches. Edited By Marshall Tymn. St. Paul: The John Colet Press, 1980.

- Cole, Thomas. The Correspondence Of Thomas Cole and Daniel Wadsworth: Letters in the Watkinson Library, Trinity College, Hartford and New York State Library, Albany N.Y. Edited by J. Bard McNulty. Hartford: Connecticut Historical Society, 1983.

- Cole, Thomas. Thomas Cole's Poetry: The Collected Poems Of America's Foremost Painter of the Hudson River School Reflecting His Feelings for Nature and the Romantic Spirit of the Nineteenth Century. Compiled and edited by Marshall B. Tymn. York, Penns.: Liberty Cap Books, 1972.

- Cole, Thomas. "Essay on American Scenery," American Monthly Magazine 1 (January 1836): 1-12.

- Comstock, J.L. Outlines of Geology. New York: Robinson, Pratt, 1838.

- Dunlap, William. History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States , 3 vols. New York, 1834; 1918 (reprint).

- Durand, Asher B. "Letters on Landscape Painting," in American Art: 1700-1960; Sources and Documents . Edited by John McCoubrey. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1965.

- Durand, John. The Life and Times of Asher B. Durand. Introduction by Linda S. Ferber. Hensonville, N.Y.: Black Dome Press, 2007 (reprint).

- Earenfight, Phillip, and Nancy Siegel, eds. Within the Landscape: Essays on Nineteenth-Century American Art and Culture . University Park, Penns.: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005.

- Felker, Tracie. "First Impressions: Thomas Cole's Drawings of His 1825 Trip up the Hudson River," American Art Journal 24, nos. 1/2 (1992): 60-93.

- Ferber, Linda S., ed. Kindred Spirits: Asher B. Durand and the American Landscape. New York: Brooklyn Museum in association with D Giles Limited, 2007.

- Field, George. Chromatics: or, an Essay on the Analogy and Harmony of Colours. London: Printed for the author by A.J. Valpy and sold by Mr. Newman, 1817.

- Flexner, James Thomas. History of American Painting: That Wilder Image, the Native School from Thomas Cole to Winslow Homer. Boston: Little, Brown, 1962; New York: Dover Publications, 1970.

- Foshay, Ella M. and Barbara Novak. Intimate Friends: Thomas Cole, Asher B. Durand, and William Cullen Bryant. New York: The New-York Historical Society, 2000.

- Foshay, Ella M. Mr. Luman Reed's Picture Gallery: A Pioneer Collection of American Art. Introduction by Wayne Craven. Catalogue by Timothy Anglin Burgard. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. in association with the New-York Historical Society, 1990.

- Gildersleeve, Robert A. Catskill Mountain House Trail Guide: In the Footsteps of the Hudson River School. Hensonville, N.Y.: Black Dome Press, 2005.

- Gillaspie, Caroline. "The Influence on and Application of Thomas Cole's Color Theories," paper presented at "Cedar Grove Intern Symposium," 13 September 2008.

- Griffin, Randall C. "The Untrammeled Vision: Thomas Cole and the Dream of the Artist," Art Journal 52, no. 2 (Summer 1993): 66-73.

- Harvey, Eleanor Jones. The Painted Sketch: American Impressions from Nature, 1830-1880. New York: Dallas Museum of Art in association with Harry N. Abrams, 1998.

- Helmer, William F. Rip Van Winkle Railroads. Hensonville, N.Y.: Black Dome Press, 1999.

- Hone, Philip. The Diary of Philip Hone. Edited by Allan Nevins. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1927.

- Horn, Field. The Greene County Catskills: A History. Hensonville, N.Y.: Black Dome Press, 1994.

- Howat, John K. The Hudson River and its Painters. New York: Viking Press, 1972.

- Huntington, Daniel C. The Landscapes of Frederic Edwin Church: Vision of an American Era . New York: George Braziller, 1966.

- The Hudson River Portfolio. Views from drawings by W. G. Wall by John Hill. New York: Published by Henry I. Megarey, 1823-24.

- Katlan, Alexander. "The American Artist's Tools and Materials for On-Site Oil Sketching," Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 38, no.1 (Spring 1999): 21-32.

- Kelly, Franklin. Frederic Edwin Church and the National Landscape. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1988.

- Kornhauser, Elizabeth Mankin and Amy Ellis. Hudson River School: Masterworks from the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art . New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, 2003.

- Maddox, Kenneth W. "Thomas Cole and the Railroad: Gentle Maledictions," Archives of American Art Journal 26, no. 1 (1986): 2-10.

- Maynard, Barksdale W. "Thomas Cole Drawing on Stone Found at Cedar Grove," American Art Journal 30, nos. 1/2 (1999): 133-139.

- Merritt, Howard S. To Walk with Nature: The Drawings of Thomas Cole. Yonkers, N.Y.: Hudson River Museum, 1981.

- Miller, Angela L. The Empire of the Eye: Landscape Representation and American Cultural Politics, 1825-1875. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1993.

- Myers, Kenneth. The Catskills: Painters, Writers, and Tourists in the Mountains, 1820-1895. Yonkers, N.Y.: Hudson River Museum of Westchester, 1987.

- Myers, Kenneth. "On the Cultural Construction of Landscape Experience: Contact to 1830," in American Iconology. Edited by David C. Miller. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1993.

- Noble, Louis Legrand. The Life and Works of Thomas Cole. Edited by Elliot S. Vesell. Hensonville, N.Y.: Black Dome Press, 1997 (reprint).

- Novak, Barbara. American Painting of the Nineteenth Century: Realism, Idealism, and the American Experience. New York: Harper & Row, 1979.

- Novak, Barbara. Nature and Culture: American Landscape and Painting, 1825-1875. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980.

- Nygren, Edward J., Bruce Robertson, et al. Views and Visions: American Landscape before 1830. Washington, D.C.: The Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1986.

- Oram, William and Charles Clarke. Precepts and Observations on the Art of Colouring in Landscape Painting. London: Printed for White and Cochranne by Richard Taylor, 1810.

- Parry, Ellwood C., III. The Art of Thomas Cole: Ambition and Imagination. Newark, Dela.: University of Delaware Press, 1988.

- Parry, Ellwood C., III. "Thomas Cole and the Problem of Figure Painting," American Art Journal 4, no. 1 (May 1972): 66-86.

- Peck, H. Daniel. "Unlikely Kindred Spirits: A New Vision of Landscape in the Works of Henry David Thoreau and Asher B. Durand," American Literary History 17, no. 4 (2005): 687-713.

- Phillips, Sandra S. and Linda Weintraub, eds. Charmed Places: Hudson River Artists and Their Houses, Studios, and Vistas. New York: Bard College and Vassar College in association with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1988.

- Powell, Earl A. Thomas Cole. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1990, 2000.

- Rosenthal, Gertrude, Howard S. Merritt, William H. Gerdts, Jr., and Kay Silberfeld. Studies on Thomas Cole, An American Romanticist. Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1967.

- Schuyler, David. The New Urban Landscape: The Redefinition of City Form in Nineteenth-Century America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986, 1988.

- Schweizer, Paul D., Ellwood C. Parry III, and Dan A. Kushel. The Voyage of Life by Thomas Cole: Paintings, Drawings, and Prints . Utica: Museum of Art, Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, 1985.

- Schweizer, Paul D. "'So Exquisite a Transcript': James Smillie's Engravings after Thomas Cole's Voyage of Life " (Part I), Imprint 11, no. 2 (Autumn 1986): 2-13.

- Schweizer, Paul D. "'So Exquisite a Transcript': James Smillie's Engravings after Thomas Cole's Voyage of Life " (Part II), Imprint 12, no. 1 (Spring 1987): 13-24.

- Sears, John. Sacred Places: American Tourist Attractions in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Siegel, Nancy. Along The Juniata: Thomas Cole and the Dissemination of American Landscape Imagery . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003.

- Stebbins, Theodore E., with contributions by Eleanor Jones [Harvey], et al. The Lure of Italy: American Artists and the Italian Experience, 1760-1914. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts; New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992.

- Stilgoe, John R., Ellwood C. Parry III, Frances Dunwell, and Christine T. Robinson. Thomas Cole: Drawn to Nature. Albany: Albany Institute of History and Art, 1993.

- Sweeney, J. Gray. "'Embued with Rare Genius:' Frederic Edwin Church's To the Memory of Cole, " Smithsonian Studies in American Art 2, no. 1 (Winter 1988): 45-71.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River School. Introduction by John K. Howat with contributions by Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, Kevin J. Avery, Barbara Ball Buff, et al. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Distributed by Harry N. Abrams, 1987.

- Truettner, William H. and Alan Wallach, eds., with contributions by J. Gray Sweeney, et al. Thomas Cole: Landscape into History. New Haven: Yale University Press; Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1994.

- Van Zandt, Roland. The Catskill Mountain House. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1966.

- Veith, Gene Edward. Painters of Faith: The Spiritual Landscape in Nineteenth-Century America . Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing, 2001.

- Wallach, Alan. "Cole, Byron and The Course of Empire ," The Art Bulletin 50, no. 4 (1968): 375-379.

- Wallach, Alan."Making a Picture of The View from Mt. Holyoke ," in American Iconology. Edited by David C. Miller. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1993.

- Wallach, Alan. "Thomas Cole and the Aristocracy," in Reading American Art . Edited by Marianne Doezema and Elizabeth Milroy. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Wallach, Alan. "Thomas Cole's River in the Catskills as Antipastoral," The Art Bulletin 84, no. 2 (June 2002): 334-351.

- Wallach, Alan."Wadsworth's Tower: an Episode in the History of American Landscape Vision," American Art 10 (Fall 1996): 8-27.

- Wharton, Edith. The House of Mirth . First published in New York by Charles Scribner's Sons, 1905. London: Virago Press, 2007.

- Williams, Henry. Elements of Drawing Exemplified in a Variety of Figures and Sketches of Parts of the Human Form Consisting of Twenty-six Copperplate Engravings, with Instructions for the Young Beginner. Boston: R.P. and C. Williams, 1818.

- Willis, Nathaniel Parker. American Scenery, or, Land, Lake and River Illustrations of Transatlantic Nature. With illustrations by W.H. Bartlett. London: George Virtue, 1840.

- Wilmerding, John, et al. American Light: The Luminist Movement, 1850-75. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1980.

- Wilton, Andrew and Tim Barringer. American Sublime: Landscape Painting in the United States, 1820-1880. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

- Zucker, Joyce. "From the Ground Up: The Ground in 19th-Century American Pictures," Journal for the American Institute for Conservation 38, no. 1 (Spring 1999): 3-20. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3179834

Online Resources

- Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution: http://www.aaa.si.edu/

- Detroit Institute of Arts: http://www.dia.org/

- Greene County Historical Society: http://www.gchistory.org/

- Hudson River Museum: http://www.hrm.org/

- Hudson River Portfolio, featuring the collections of the New York Public Library: http://www.nypl.org/research/hudson/index.html

- Hudson River School Art Trail: http://thomascole.org/trail

- Hudson River School Glossary, The Albany Institute of History and Art: http://www.albanyinstitute.org/education/Hudson%20River%20School/hrs.glossary.htm

- James Fenimore Cooper's The Pioneers : http://xroads.virginia.edu/~UG02/COOPER/cooperhome.html

- Metropolitan Museum of Art: http://www.metmuseum.org/

- Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Utica, New York: http://www.mwpai.org/

- National Gallery of Art: http://www.nga.gov

- New-York Historical Society: http://www.nyhistory.org

- New York State Library, Albany: http://www.nysl.nysed.gov/

- Official Tourism Site of the Catskills: http://www.visitthecatskills.com/

- Official website of the Thomas Cole House: http://www.thomascole.org

- Olana State Historic Site: http://www.olana.org

- Smithsonian American Art Museum, Inventories of American Painting and Sculpture, Thomas Cole: http://siris-artinventories.si.edu/...

- The Newington-Cropsey Foundation: http://www.newingtoncropsey.com

- Thomas Cole's "Essay on American Scenery": http://xroads.virginia.edu/~HYPER/detoc/hudson/cole.html

- Thomas Cole's poetry: http://lion.chadwyck.com/...

- Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Conn.: http://www.wadsworthatheneum.org/

- William Cullen Bryant's "Funeral Oration" for Cole: http://www.catskillarchive.com/cole/wcb.htm

This site employs current web standards and accessibility best practices for CSS, XHTML, Flash, and JavaScript. It performs best with Firefox 3.x and Apple Safari 3.x or greater , Opera 9.x and Adobe Flash Player 10 or greater.

- Contributors

- © 2015

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Essay on American Scenery. By Thomas Cole Published in American Monthly Magazine 1 (January 1836) [I. Introduction] The essay, which is here offered, is a mere sketch of an almost illimitable subject--American Scenery; and in selecting the theme the writer placed more confidence in its overflowing richness, than in his own capacity for treating ...

—Thomas Cole, "Essay on American Scenery," The American Monthly Magazine, vol. 7, January 1836, p. 12. Go deeper. Learn more about this painting from the Amon Carter Museum. Who was Thomas Cole? Read Thomas Cole's "An Essay on American Scenery" ...

In 1836 Cole published his "Essay on American Scenery", which was, in part, a riposte to Hall.In it he lauded his adopted land, pointing out that its landscapes offered not just the sublime but also the picturesque and the beautiful - three themes that had been an important part of artistic discourse in Europe since the mid-18th century.

Thomas Cole inspired the generation of American landscape painters that came to be known as the Hudson River School.Born in Bolton-le-Moors, Lancashire, England, in 1801, at the age of seventeen he emigrated with his family to the United States, first working as a wood engraver in Philadelphia before going to Steubenville, Ohio, where his father had established a wallpaper manufacturing business.

Emerson had first written a version of that passage in his journal on January 16, 1836—at just about the same time Cole published his "Essay on American Scenery" in the January issue of American Monthly magazine. Cole's essay argued that the United States was full of beauty that Americans had yet to appreciate fully.

Thomas Cole's Essay on American Scenery is a seminal work of American environmentalism, first published in 1836. The text of this edition is based on a revised version, which Cole delivered as a lecture before the Catskill Lyceum in 1841. Paperbound, 24 pages, 4.5 x 7 inches.

Cole, in his famous "Essay on American Scenery" of 1836, echoed Constable's sentiment, writing that the sky is "the soul of all scenery, in it are the fountains of light, and shade, ... Left: Thomas Cole (American, 1801-1848). Clouds, ca. 1830s. Oil on paper laid down on canvas, 8 3/4 x 10 7/8 in. (22.2 x 27.6 cm).

Essay on American Scenery Thomas Cole. In document American Beauty: Nineteenth-Century Landscapes (Page 60-70) The American Monthly Magazine 1 (January 1836) [I. Introduction] The essay, which is here offered, is a mere sketch of an almost illimitable subject-- American Scenery; and in selecting the theme the writer placed more confidence in ...

5 thoughts on " Thomas Cole " Tamir Williams November 21, 2013 at 10:27 am. In his essay, Cole expresses his fondness and preference for American scenery, which, in his opinion, "[is] unsurpassed" by other countries where "the primitive features of scenery have long since been destroyed or modified…to accommodate the tastes and necessities of a dense population" (108, 102).

landscape/essay-on-american-scenery (accessed 18 October 2010) Essay on American Scenery Thomas Cole, "Essay on American Scenery," The American Magazine, n.s. 1 (Jan. 1836): 1-12. The Essay, which is here offered, is a mere sketch of an almost illimitable subject--American Scenery; and in selecting the theme the writer placed more confidence in its

Thomas Cole, "Essay on American Scenery," Open Virtual Worlds, accessed January 28, 2024, https://openvirtualworlds.org/omeka/items/show/1157.

Thomas Cole, Catskills Mountain Landscape, 1826. It seems that Cole was ahead of the curve regarding how Christians should understand and interact with the environment - as a way to connect with the divine. In "Essay on American Scenery" (1836) Cole himself wrote: It has not been in vain - the good, the enlightened of all ages and ...

Drawing on influences from both sides of the Atlantic, Thomas Cole brought attention to the glory of pure wilderness and the encroaching order of civilization. "The most distinctive, and perhaps the most impressive, characteristic of American scenery is its wildness," wrote the painter Thomas Cole (1801-48) in an 1836 essay.

In Thomas Cole's Essay on American Scenery, the reader is able to appreciate Cole's predilection and love for the American scenery. It is his belief this scenery is superior to the European scenery, since the latter's "primitive features of scenery have long since been destroyed or modified … to accommodate the tastes and necessities of a dense population."

Bailey Marshall November 19, 2014 at 11:15 am. Thomas Cole views American scenery as a source of joy and consolation. He writes of the tranquility, peace and transparency of water as well as other beautifiers of the earth including the forest scenery, hills, and sky.

Cole's decision to incorporate a train into his natural landscape may refer to the artist's well-known writings about the destructive impact of industry on nature, particularly his 1836 "Essay on American Scenery."[1]His ambivalent attitude was shared by many of his contemporaries, who witnessed their world being dramatically ...

Cole, Thomas. "Essay on American Scenery," American Monthly Magazine 1 (January 1836): 1-12. Comstock, J.L. Outlines of Geology. New York: Robinson, Pratt, 1838. Dunlap, William. History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, 3 vols. New York, 1834; 1918 (reprint).

In the eyes of such folks American scenery is "rude without picturesqueness, and monotonous without sublimity." You can almost hear Cole's frustration when he addresses the argument that American scenery is inferior because it lacks the "vestiges of antiquity" - the ancient buildings and ruins - that are associated with European landscapes.