The ‘Me’ Decade

The new alchemical dream is: changing one’s personality—remaking, remodeling, elevating, and polishing one’s very self..

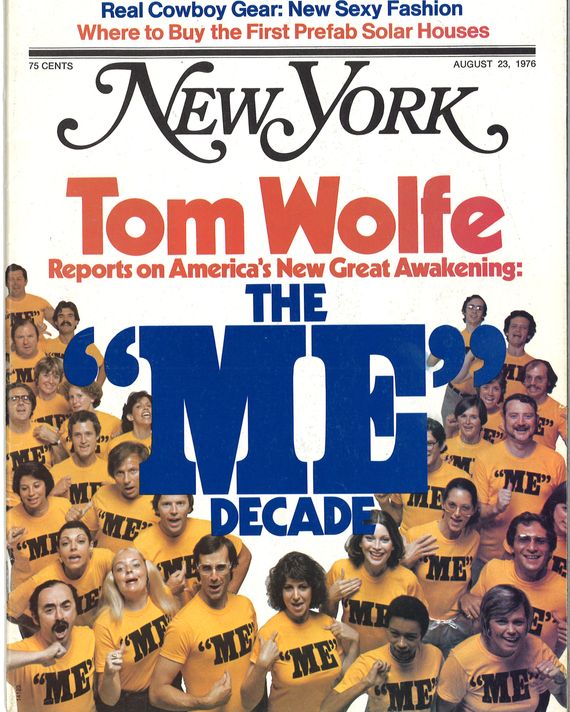

Editor’s note: This story first appeared in the August 23, 1976, issue of New York . It was also featured in Reread , New York’s subscriber-only archives newsletter. Click here to read the newsletter this appeared in.

I. Me and My Hemorrhoids

The trainer said, “Take your finger off the repress button.” Everybody was supposed to let go, let all the vile stuff come up and gush out. They even provided vomit bags, like the ones on a 747, in case you literally let it gush out! Then the trainer told everybody to think of “the one thing you would most like to eliminate from your life.” And so what does our girl blurt over the microphone?

“Hemorrhoids!”

That was how she ended up in her present state … stretched out on the wall-to-wall carpet of the banquet hall of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles with her eyes closed and her face pressed into the stubble of the carpet, which is a thick commercial weave and feels like clothes-brush bristles against her face and smells a bit high from cleaning solvent. That was how she ended up lying here concentrating on her hemorrhoids.

Eyes shut! deep in her own space! her hemorrhoids! the grisly peanut—

Many others are stretched out on the carpet all around her; some 249 other souls, in fact. They’re all strewn across the floor of the banquet hall with their eyes closed, just as she is. But Christ, the others are concentrating on things that sound serious and deep when you talk about them. And how they had talked about them! They had all marched right up to the microphone and “shared,” as the trainer called it. What did they want to eliminate from their lives? Why, they took their fingers right off the old repress button and told the whole room. My husband! my wife! my homosexuality! my inability to communicate, my self-hatred, self-destructiveness, craven fears, puling weaknesses, primordial horrors, premature ejaculation, impotence, frigidity, rigidity, subservience, laziness, alcoholism, major vices, minor vices, grim habits, twisted psyches, tortured souls—and then it had been her turn, and she had said, “Hemorrhoids.”

You can imagine what that sounded like. That broke the place up. The trainer looked like a cocky little bastard up there on the podium with his deep tan, white tennis shirt, and peach-colored sweater, a dynamite color combination, all very casual and spontaneous—after about two hours of trying on different outfits in front of a mirror, that kind of casual and spontaneous, if her guess was right. And yet she found him attractive. Commanding was the word. He probably wondered if she were playing the wiseacre, with her “hemorrhoids,” but he rolled with it. Maybe she was being playful. Just looking at him made her feel mischievous. In any event, hemorrhoids was what had bubbled up into her brain.

Then the trainer had told them to stack their folding chairs in the back of the banquet hall and lie down on the floor and close their eyes and get deep into their own spaces and concentrate on that one item they wanted to get rid of the most—and really feel it and let the feeling gush out.

So now she’s lying here concentrating on her hemorrhoids. The strange thing is … it’s no joke after all! She begins to feel her hemorrhoids in all their morbid presence. She can actually feel them. The sieges always began with her having the sensation that a peanut was caught in her anal sphincter. That meant a section of swollen varicose vein had pushed its way out of her intestines and was actually coming out of her bottom. It was as hard as a peanut and felt bigger and grislier than a peanut. Well—for God’s sake!—in her daily life, even at work, especially at work, and she works for a movie distributor, her whole picture of herself was of her … seductive physical presence. She was not the most successful businesswoman in Los Angeles, but she was certainly successful enough, and quite in addition to that, she was … the main sexual presence in the office. When she walked into the office each morning, everyone, women as well as men, checked her out. She knew that. She could feel her sexual presence go through the place like an invisible chemical, like a hormone, a scent, a universal solvent.

The most beautiful moments came when she would be in her office or in a conference room or at Mr. Chow’s taking a meeting—nobody “had” meetings anymore, they “took” them—with two or three men, men she had never met before or barely knew. The overt subject was, inevitably, eternally, “the deal.” She always said there should be only one credit line up on the screen for any movie: “Deal by… .” But the meeting would also have a subplot. The overt plot would be “The Deal.” The subplot would be “The Men Get Turned On by Me.” Pretty soon, even though the conversation had not strayed overtly from “The Deal,” the men would be swaying in unison like dune grass at the beach. And she was the wind, of course. And then one of the men would say something and smile and at the same time reach over and touch her … on top of the hand or on the side of the arm … as if it meant nothing … as if it were just a gesture for emphasis … but in fact a man is usually deathly afraid of reaching out and touching a woman he doesn’t know … and she knew it meant she had hypnotized him sexually… .

Well—for God’s sake!—at just that sublime moment, likely as not, the goddam peanut would be popping out of her tail! As she smiled sublimely at her conquest, she also had to sit in her chair lopsided, with one cheek of her buttocks higher than the other, as if she were about to crepitate, because it hurt to sit squarely on the peanut. If for any reason she had to stand up at that point and walk, she would have to walk as if her hip joints were rusted out, as if she were 65 years old, because a normal stride pressed the peanut, and the pain would start up, and the bleeding, too, very likely. Or if she couldn’t get up and had to sit there for a while and keep her smile and her hot hormonal squinted eyes pinned on the men before her, the peanut would start itching or burning, and she would start double-tracking, as if her mind were a tape deck with two channels going at once. In one she’s the sexual princess, the Circe, taking a meeting and clouding men’s minds … and in the other she’s a poor bitch who wants nothing more in this world than to go down the corridor to the ladies’ room and get some Kleenex and some Vaseline and push the peanut back up into her intestines with her finger.

And even if she’s able to get away and do that, she will spend the rest of that day and the next, and the next, with a deep worry in the back of her brain, the sort of worry that always stays on the edge of your consciousness, no matter how hard you think of something else. She will be wondering at all times what the next bowel movement will be like, how solid and compact the bolus will be, trying to think back and remember if she’s had any milk, cream, chocolate, or any other binding substance in the last 24 hours, or any nuts or fibrous vegetables like broccoli. Is she really in for it this time—

The Sexual Princess! On the outside she has on her fireproof grin and her Fiorio scarf as if to say she lives in a world of Sevilles and 450SL’s and dinner last night at Dominick’s, a movie-business restaurant on Beverly Boulevard that’s so exclusive, Dominick keeps his neon sign (DOMINICK’S) turned off to make the wimps think it’s closed, but she (Hi, Dominick!) can get a table—but inside her it’s all the battle between the bolus and the peanut—

—and is it too late to leave the office and go get some mineral oil and let some of that vile glop roll down her gullet or get a refill on the softener tablets or eat some prunes or drink some coffee or do something else to avoid one of those horrible hard-clay boluses that will come grinding out of her, crushing the peanut and starting not only the bleeding but … the pain! … a horrible humiliating pain that feels like she’s getting a paper cut in her anus, like the pain you feel when the edge of a piece of bond paper slices your finger, plus a horrible hellish purple bloody varicose pressure, but lasting not for an instant, like a paper cut, but for an eternity, prolonged until the tears are rolling down her face as she sits in the cubicle, and she wants to cry out, to scream until it’s over, to make the screams of fear, fury, and humiliation obliterate the pain. But someone would hear! No doubt they’d come bursting right into the ladies’ room to save her! and feed their morbid curiosities! And what could she possibly say? And so she had simply held that feeling in all these years, with her eyes on fire and her entire pelvic saddle a great purple tub of pain. She had repressed the whole squalid horror of it— the searing peanut—

—until now. The trainer had said, “Take your finger off the repress button!” Let it gush up and pour out!

And now, as she lies here on the floor of the banquet hall of the Ambassador Hotel with 249 other souls, she knows exactly what he meant. She can feel it all, all of the pain, and on top of the pain all the humiliation, and for the first time in her life she has permission from the Management, from herself, and from everyone around her to let the feeling gush forth. So she starts moaning.

“Ooooooooooooooohhhhhhhhhhhh!”

And when she starts moaning, the most incredible and exhilarating thing begins to happen. A wave of moans spreads through the people lying around her, as if her energy were radiating out like a radar pulse.

So she lets her moan rise into a keening sound.

“Oooooooooooooohhhhhhhhhhhhhhhheeeeeeeeeeeeeeee!”

And when she begins to keen, the souls near her begin keening, even while the moans are still spreading to the prostrate folks farther from her, on the edges of the room.

“Eeeeeeeeeooooooohhhhhhhhheeeeeooooooooh!”

So she lets her keening sound rise up into a real scream.

“Eeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeaiaiaiaiaiaiaiaiai!”

And this rolls out in a wave, too, first through those near her, and then toward the far edges.

“Aiaiaiaiaiaiaiaiaiaiaieeeeeeeeeeeeeeohhhhhhhhhheeeeeeaiaiai!”

And so she turns it all the way up, into a scream such as she has never allowed herself in her entire life.

“AiaiaiaiaiaiaiaiaiaiaaaaAAAAAAAAAARRRRRRGGGGGGHHHHHH!”

And her full scream spreads from soul to soul, over top of the keens and fading moans . . .

“AAAAAAAARRRRRRGGGGGHHHaiaiaiaieeeeeeeeeooooohhheeeeaiaiaiaiaiaiaaaaAAAAAAAARRRRRRRRRRRGGGGHHHHHH!”

…until at last the entire room is consumed in her scream, as if there are no longer 250 separate souls but one noosphere of souls united in some incorporeal way by her scream. . .

“AAAAAAAAAAARGGGGGGGGHHHHHH!”

Which is not simply her scream any longer … but the world’s! Each soul is concentrated on its own burning item … my husband! my wife! my homosexuality! my inability to communicate, my self-hatred, self-destruction, craven fears, puling weaknesses, primordial horrors, premature ejaculation, impotence, frigidity, rigidity, subservience, laziness, alcoholism, major vices, minor vices, grim habits, twisted psyches, tortured souls—and yet each unique item has been raised to a cosmic level and united with every other until there is but one piercing moment of release and liberation at last—a whole world of anguish set free by . . .

My hemorrhoids.

“Me and My Hemorrhoids Star at the Ambassador” … during a three-day Erhard Seminars Training (est) course in the hotel banquet hall. The truly odd part, however, is yet to come. In her experience lies the explanation of certain grand puzzles of the 1970s, a period that will come to be known as the Me Decade.

II. The Holy Roll

In 1972 a farsighted caricaturist did a drawing of Teddy Kennedy captioned “President Kennedy campaigning for re-election in 1980 … courting the so-called Awakened vote.”

The picture shows Kennedy ostentatiously wearing not only a crucifix but also (if one looks just above the cross) a pendant of the Bleeding Heart of Jesus. The crucifix is the symbol of Christianity in general, but the Bleeding Heart is the symbol of some of Christianity’s most ecstatic, nonrational, holy-rolling cults. I should point out that the artist’s prediction lacked certain refinements. For one thing, Kennedy may be campaigning to be president in 1980, but he is not terribly likely to be the incumbent. For another, the odd spectacle of politicians using ecstatic, nonrational, holy-rolling religion in presidential campaigning was to appear first not in 1980 but in 1976.

The two most popular new figures in the 1976 campaign, Jimmy Carter and Jerry Brown, are men who rose up from state politics … absolutely aglow with mystical religious streaks. Carter turned out to be an evangelical Baptist who had recently been “born again” and “saved,” who had “accepted Jesus Christ as my personal Savior”—i.e., he was of the Missionary lectern-pounding amen ten-finger C-major-chord Sister-Martha-at-the-Yamaha-keyboard loblolly piny-woods Baptist faith in which the members of the congregation stand up and “give witness” and “share it. Brother” and “share it, Sister” and “Praise God!” during the service. Jerry Brown turned out to be the Zen Jesuit, a former Jesuit seminarian who went about like a hair-shirt Catholic monk, but one who happened to believe also in the Gautama Buddha, and who got off koans in an offhand but confident manner, even on political issues, as to how it is not the right answer that matters but the right question, and so forth.

Newspaper columnists and newsmagazine writers continually referred to the two men’s “enigmatic appeal.” Which is to say, they couldn’t explain it. Nevertheless, they tried. They theorized that the war in Vietnam, Watergate, the FBI and CIA scandals, had left the electorate shell-shocked and disillusioned and that in their despair the citizens were groping no longer for specific remedies but for sheer faith, something, anything (even holy rolling), to believe in. This was in keeping with the current fashion of interpreting all new political phenomena in terms of recent disasters, frustration, protest, the decline of civilization … the Grim Slide. But when the New York Times and CBS employed a polling organization to try to find out just what great gusher of “frustration” and “protest” Carter had hit, the results were baffling. A Harvard political scientist, William Schneider, concluded for the L.A. Times that “the Carter protest” was a new kind of protest, “a protest of good feelings.” That was a new kind, sure enough—a protest that wasn’t a protest.

In fact, both Carter and Brown had stumbled upon a fabulous terrain for which there are no words in current political language. A couple of politicians had finally wandered into the Me Decade.

III. Him? — The New Man?

The saga of the Me Decade begins with one of those facts that is so big and so obvious (like the Big Dipper), no one ever comments on it anymore. Namely: the 30-year boom. Wartime spending in the United States in the 1940s touched off a boom that has continued for more than 30 years. It has pumped money into every class level of the population on a scale without parallel in any country in history. True, nothing has solved the plight of those at the very bottom, the chronically unemployed of the slums. Nevertheless, in Compton, California, today it is possible for a family at the very lowest class level, which is known in America today as “on welfare,” to draw an income of $8,000 a year entirely from public sources. This is more than most British newspaper columnists and Italian factory foremen make, even allowing for differences in living costs. In America truck drivers, mechanics, factory workers, policemen, firemen, and garbagemen make so much money—$15,000 to $20,000 (or more) per year is not uncommon—that the word proletarian can no longer be used in this country with a straight face. So one now says lower middle class. One can’t even call workingmen blue collar any longer. They all have on collars like Joe Namath’s or Johnny Bench’s or Walt Frazier’s. They all have on $35 Superstar Qiana sport shirts with elephant collars and 1940s Airbrush Wallpaper Flowers Buncha Grapes and Seashell designs all over them.

Well, my God, the old utopian socialists of the nineteenth century—such as Saint-Simon, Owen, Fourier, and Marx— lived for the day of the liberated workingman. They foresaw a day when industrialism (Saint-Simon coined the word) would give the common man the things he needed in order to realize his potential as a human being: surplus (discretionary) income, political freedom, free time (leisure), and freedom from grinding drudgery. Some of them, notably Owen and Fourier, thought all this might come to pass first in the United States. So they set up communes here: Owen’s New Harmony commune in Indiana and 34 Fourier-style “phalanx” settlements—socialist communes, because the new freedom was supposed to be possible only under socialism. The old boys never dreamed that the new freedom would come to pass instead as the result of a Go-Getter Bourgeois business boom such as began in the United States in the 1940s. Nor would they have liked it if they had seen it. For one thing, the homo novus , the new man, the liberated man, the first common man in the history of the world with the much-dreamed-of combination of money, free time, and personal freedom—this American workingman didn’t look right. The Joe Namath-Johnny Bench—Walt Frazier-Superstar Qiana Wallpaper sport shirt, for a start.

He didn’t look right, and he wouldn’t … do right! I can remember what brave plans visionary architects at Yale and Harvard still had for the common man in the early 1950s. (They actually used the term “common man.”) They had brought the utopian socialist dream forward into the twentieth century. They had things figured out for the workingman down to truly minute details such as lamp switches. The new liberated workingman would live as the Cultivated Ascetic. He would be modeled on the B.A.-degree Greenwich Village bohemian of the late 1940s—dark wool Hudson Bay shirts, tweed jackets, flannel trousers, briarwood pipes, good books, sandals and simplicity—except that he would live in a Worker Housing project. All Yale and Harvard architects worshiped Bauhaus principles and had the Bauhaus vision of Worker Housing. The Bauhaus movement absolutely hypnotized American architects, once its leaders, such as Walter Gropius and Ludwig Miës van der Rohe, came to the United States from Germany in the 1930s. Worker Housing in America would have pure beige rooms, stripped, freed, purged of all moldings, cornices, and overhangs—which Gropius regarded as symbolic “crowns” and therefore loathsome. Worker Housing would be liberated from all wallpaper, “drapes,” Wilton rugs with flowers on them, lamps with fringed shades and bases that looked like vases or Greek columns. It would be cleansed of all doilies, knickknacks, mantelpieces, headboards, and radiator covers. Radiator coils would be left bare as honest, abstract sculptural objects.

But somehow the workers, incurable slobs that they were, avoided Worker Housing, better known as “the projects,” as if it had a smell. They were heading out instead to the suburbs—the suburbs! —to places like Islip, Long Island, and the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles—and buying houses with clapboard siding and a high-pitched roof and shingles and gaslight-style front-porch lamps and mailboxes set up on top of lengths of stiffened chain that seemed to defy gravity and all sorts of other unbelievably cute or antiquey touches, and they loaded these houses up with “drapes” such as baffled all description and wall-to-wall carpet you could lose a shoe in, and they put barbecue pits and fish ponds with concrete cherubs urinating into them on the lawn out back, and they parked 25-foot-long cars out front and Evinrude cruisers up on tow trailers in the carport just beyond the breezeway.

By the 1960s the common man was also getting quite interested in this business of “realizing his potential as a human being.” But once again he crossed everybody up! Once more he took his money and ran—determined to do-it-himself!

IV. Lemon Sessions

In 1971 I made a lecture tour of Italy, talking (at the request of my Italian hosts) about “contemporary American life.” Everywhere I went, from Turin to Palermo, Italian students were interested in just one question: Was it really true that young people in America, no older than themselves, actually left home, and lived communally according to their own rules and created their own dress styles and vocabulary and had free sex and took dope? They were talking, of course, about the hippie or psychedelic movement that had begun flowering about 1965. What fascinated them the most, however, was the first item on the list: that the hippies actually left home and lived communally according to their own rules.

To Italian students this seemed positively amazing. Several of the students I met lived wild enough lives during daylight hours. They were in radical organizations and had fought pitched battles with police, on the barricades, as it were. But by 8:30 P.M. they were back home, obediently washing their hands before dinner with Mom&Dad&Buddy&Sis&theMaidenAunt. Their counterparts in America, the New Left students of the late sixties, lived in communes that were much like the hippies’, except that the costumery tended to be semimilitary: the noncom officers’ shirts, combat boots, commando berets—worn in combination with blue jeans or a turtleneck jersey, however, to show that one was not a uniform freak.

That people so young could go off on their own, without taking jobs, and live a life completely of their own design—to Europeans it was astounding. That ordinary factory workers could go off to the suburbs and buy homes and create their own dream houses—this, too, was astounding. And yet the new life of old people in America in the 1960s was still more astounding. Throughout European history and in the United States up to the Second World War, old age was a time when you had to cling to your children or other kinfolk, and to their sufferance and mercy, if any. The Old Folks at Home happily mingling in the old manse with the generations that followed? The little ones learning at grandpa’s and grandma’s bony knees? These are largely the myths of nostalgia. The beloved old folks were often exiled to the attic or the outbuildings, and the servants brought them their meals. They were not considered decorative in the dining room or the parlor.

In the 1960s, old people in America began doing something that was more extraordinary than it ever seemed at the time. They cut through the whole dreary humiliation of old age by heading off to “retirement villages” and “leisure developments”—which quickly became Old Folks communes. Some of the old parties managed to take this to a somewhat psychedelic extreme, joining trailer caravans … and rolling … creating some of the most amazing sights of the modern American landscape … such as 30, 40, 50 Airstream trailers, the ones that are silver and have rounded corners and ends and look like silver bullets … 30, 40, 50 of these silver bullets in a line, in a caravan, hauling down the highway in the late afternoon with the sun at a low angle and exploding off the silver surfaces of the Airstreams until the whole convoy looks like some gigantic and improbable string of jewelry, each jewel ablaze with a highlight, rolling over the face of the earth—the million-volt billion-horsepower bijoux of America! The Trailer Sailors!

Ignored or else held in contempt by working people, Bauhaus design eventually triumphed as a symbol of wealth and privilege, attuned chiefly to the tastes of businessmen’s wives. For example, Miës’s most famous piece of furniture design, the Barcelona chair, now sells for $1.680 and is available only through one’s decorator. The high price is due in no small part to the chair’s Worker Housing Honest Materials: stainless steel and leather. No chromed iron is allowed, and customers are refused if they want to have the chair upholstered in material of their own choice. Only leather is allowed, and only six shades of that: Seagram’s Building Lobby Palomino, Monsanto Company Lobby Antelope, Architectural Digest Pecan, Transamerica Building Ebony, Bank of America Building Walnut, and Embarcadero Center Mink.

It was remarkable enough that ordinary folks now had enough money to take it and run off and alter the circumstances of their lives and create new roles for themselves, such as Trailer Sailor or Gerontoid Cowboy. But, simultaneously, still others decided to go … all the way. They plunged straight toward what has become the alchemical dream of the Me Decade.

The old alchemical dream was changing base metals into gold. The new alchemical dream is: changing one’s personality—remaking, remodeling, elevating, and polishing one’s very self … and observing, studying, and doting on it. (Me!) This had always been an aristocratic luxury, confined throughout most of history to the life of the courts, since only the very wealthiest classes had the free time and the surplus income to dwell upon this sweetest and vainest of pastimes. It smacked so much of vanity, in fact, that the noble folk involved in it always took care to call it quite something else.

Much of the satisfaction well-born people got from what is known historically as the “chivalric tradition” was precisely that: dwelling upon Me and every delicious nuance of my conduct and personality. At Versailles, Louis XIV founded a school for the daughters of impoverished noblemen, called L’Ecole Saint-Cyr. At the time most schools for girls were in convents. Louis had quite something else in mind, a secular school that would develop womenfolk suitable for the superior race guerrière that he believed himself to be creating in France. Saint-Cyr was the forerunner of what was known up until a few years ago as the finishing school . And what was the finishing school? Why, a school in which the personality was to be shaped and buffed like a piece of high-class psychological cabinetry. For centuries most of upper-class college education in France and England has been fashioned in the same manner: with an eye toward sculpting the personality as carefully as the intellectual faculties.

At Yale the students on the outside wondered for 80 years what went on inside the fabled secret senior societies, such as Skull and Bones. On Thursday nights one would see the secret-society members walking silently and single file, in black flannel suits, white shirts, and black knit ties with gold pins on them, toward their great Greek Revival temples on the campus, buildings whose mystery was doubled by the fact that they had no windows. What in the name of God or Mammon went on in those 30-odd Thursday nights during the senior years of these happy few? What went on was … lemon sessions! —a regularly scheduled series of lemon sessions, just like the ones that occurred informally in girls’ finishing schools.

In the girls’ schools these lemon sessions tended to take place at random on nights when a dozen or so girls might end up in someone’s dormitory room. One girl would become “it,” and the others would light into her personality, pulling it to pieces to analyze every defect … her spitefulness, her awkwardness, her bad breath, embarrassing clothes, ridiculous laugh, her suck-up fawning, latent lesbianism, or whatever. The poor creature might be reduced to tears. She might blurt out the most terrible confessions, hatreds, and primordial fears. But, it was presumed, she would be the stronger for it afterward. She would be on her way toward a new personality. Likewise, in the secret societies: They held lemon sessions for boys. Is masturbation your problem? Out with the truth, you ridiculous weenie! And Thursday night after Thursday night the awful truths would out, as he who was It stood up before them and answered the most horrible questions. Yes! I do it! I whack whack whack it! I’m afraid of women! I’m afraid of you! And I get my shirts at Rosenberg’s instead of Press! (Oh, you dreary turkey, you wet smack, you little shit!) … But out of the fire and the heap of ashes would come a better man, a brother, of good blood and good bone, for the American race guerrière. And what was more … they loved it. No matter how dreary the soap opera, the star was Me.

By the mid-1960s this service, this luxury, had become available for one and all, i.e., the middle classes. Lemon Session Central was the Esalen Institute, a lodge perched on a cliff over-looking the Pacific in Big Sur, California, Esalen’s specialty was lube jobs for the personality. Businessmen, businesswomen, housewives—anyone who could afford it, and by now many could—paid $220 a week to come to Esalen to learn about themselves and loosen themselves up and wiggle their fannies a bit, in keeping with methods developed by William C. Schutz and Frederick Perls. Fritz Perls, as he was known, was a remarkable figure, a psychologist who had a gray beard and went about in a blue terry-cloth jump suit and looked like a great blue grizzled father bear. His lemon sessions sprang not out of the manly virtues and cold showers Protestant-prep-school tradition of Yale but out of psychoanalysis. His sessions were a variety of the “marathon encounter.” He put the various candidates for personality change in groups, and they met in close quarters day after day. They were encouraged to bare their own souls and to strip away one another’s defensive facades. Everyone was to face his own emotions squarely for the first time.

Encounter sessions, particularly of the Schutz variety, were often wild events. Such aggression! such sobs! tears! moans, hysteria, vile recriminations, shocking revelations, such explosions of hostility between husbands and wives, such mud balls of profanity from previously mousy mommies and workadaddies, such red-mad attacks! Only physical assault was prohibited. The encounter session became a standard approach in many other movements, such as Scientology, Arica, the Mel Lyman movement, Synanon, Daytop Village, and Primal Scream. Synanon had started out as a drug rehabilitation program, but by the late 1960s the organization was recruiting “lay members,” a lay member being someone who had never been addicted to heroin … but was ready for the lemon-session life.

Outsiders, hearing of these sessions, wondered what on earth their appeal was. Yet the appeal was simple enough. It is summed up in the notion: “Let’s talk about Me. ” No matter whether you managed to renovate your personality through encounter sessions or not, you had finally focused your attention and your energies on the most fascinating subject on earth: Me. Not only that, you also put Me up on stage before a live audience. The popular “est” movement has managed to do that with great refinement. Just imagine … Me and My Hemorrhoids … moving an entire hall to the most profound outpouring of emotion! Just imagine … my life becoming a drama with universal significance … analyzed, like Hamlet’s, for what it signifies for the rest of mankind… .

The encounter session—although it was not called that—was also a staple practice in psychedelic communes and, for that matter, in New Left communes. In fact, the analysis of the self, and of one another, was unceasing. But in these groups and at Esalen and in movements such as Arica there were two common assumptions that distinguished them from the aristocratic lemon sessions and personality finishings of yore. The first was: I, with the help of my brothers and sisters, must strip away all the shams and excess baggage of society and my upbringing in order to find the Real Me. Scientology uses the word “clear” to identify the state that one must strive for. But just what is that state? And what will the Real Me be like? It is at this point that the new movements tend to take on a religious or spiritual atmosphere. In one form or another they arrive at an axiom first propounded by the Gnostic Christians some 1,800 years ago: namely, that at the apex of every human soul there exists a spark of the light of God. In most mortals that spark is “asleep” (the Gnostics’ word), all but smothered by the facades and general falseness of society. But those souls who are clear can find that spark within themselves and unite their souls with God’s. And with that conviction comes the second assumption: There is an other order that actually reigns supreme in the world. Like the light of God itself, this other order is invisible to most mortals. But he who has dug himself out from under the junk heap of civilization can discover it.

And with that … the Me movements were about to turn righteous.

V. Young Faith, Aging Groupies

By the early 1970s so many of the Me movements had reached this Gnostic religious stage, they now amounted to a new religious wave. Synanon, Arica, and the Scientology movement had become religions. The much-publicized psychedelic or hipple communes of the 1960s, although no longer big items in the press, were spreading widely and becoming more and more frankly religious. The huge Steve Gaskin commune in the Tennessee scrublands was a prime example. A New York Times survey concluded that there were at least two thousand communes in the United States by 1970, barely five years after the idea first caught on in California. Both the Esalen-style and Primal Therapy or Primal Scream encounter movements were becoming progressively less psychoanalytical and more mystical in their approach. The Oriental “meditation” religions—which had existed in the United States mainly in the form of rather intellectual and bohemian Zen and yoga circles—experienced a spectacular boom. Groups such as the Hare Krishna, the Sufi, and the Maharaj Ji communes began to discover that they could enroll thousands of new members and (in some cases) make small fortunes in real estate to finance the expansion. Many members of the New Left communes of the 1960s began to turn up in Me movements in the 1970s, including two of the celebrated “Chicago Seven.” Rennie Davis became a follower of the Maharaj Ji. Jerry Rubin enrolled in both est and Arica. Barbara Garson, who with the help of her husband, Marvin, wrote the great agitprop drama of the New Left, MacBird, would later observe, with considerable bitterness: “My husband Marvin forsook everything (me included) to find peace. For three years he wandered without shoes or money or glasses. Now he is in Israel with some glasses and possibly with some peace.” And not just him, she said, but so many other New Lefters as well: “Some follow a guru, some are into Primal Scream, some seek a rest from the diaspora—a home in Zion.” It is entirely possible that in the long run historians will regard the entire New Left experience as not so much a political as a religious episode wrapped in semi military gear and guerrilla talk.

Meanwhile the ESP or “psychic phenomena” movement began to grow very rapidly in the new religious atmosphere, ESP devotees had always believed that there was an other order that ran the universe, one that revealed itself occasionally through telepathy, déjà vu experiences, psychokinesis, dematerialization, and the like. It was but a small step from there to the assumption that all men possess a conscious energy paralleling the world of physical energy and that this mysterious energy can unite the universe (after the fashion of the light of God). A former astronaut, Edgar Mitchell, who has a doctor-of-science degree from MIT, founded the Institute of Noetic Sciences in an attempt to channel the work of all the ESP groups. “Noetic” is an adjective derived from the same root as that of “the Noosphere”—the name that Teilhard de Chardin gave his dream of a cosmic union of all souls. Even the Flying Saucer cults began to reveal their essentially religious nature at about this time. The Flying Saucer folk quite literally believed in an other order : It was under the command of superior beings from other planets or solar systems who had spaceships. A physician named Andrija Puharich wrote a book ( Uri ) in which he published the name of the God of the UFO’s: Hoova. He said Hoova had a herald messenger named Spectra, and Hoova’s and Spectra’s agent on earth, the human connection, as it were, was Uri Geller, the famous Israeli psychic and showman. Geller’s powers were also of great interest to people in the ESP movement, and there were many who wished that Puharich and the UFO people would keep their hands off him.

By the early 1970s a quite surprising movement, tagged as the Jesus People, had spread throughout the country. At the outset practically all the Jesus People were young acid heads, i.e., LSD users, who had sworn off drugs (except, occasionally, in “organic form,” meaning marijuana and peyote) but still wanted the ecstatic spiritualism of the psychedelic or hippie life. This they found in Fundamentalist evangelical holy-rolling Christianity of a sort that ten years before would have seemed utterly impossible to revive in America. The Jesus People, such as the Children of God, the Fresno God Squad, the Tony and Susan Alamo Christian Foundation, the Sun Myung Moon sect, lived communally and took an ecstatic or “charismatic” (literally: “God-imbued”) approach to Christianity, after the manner of the Oneida, Shaker, and Mormon communes of the nineteenth century … and, for the matter, after the manner of the early Christians themselves, including the Gnostics.

There was considerable irony here. Ever since the late 1950s both the Catholic Church and the leading Protestant denominations had been aware that young people, particularly in the cities, were drifting away from the faith. At every church conference and convocation and finance-committee meeting the cry went up: We must reach the urban young people. It became an obsession, this business of “the urban young people.” The key—one and all decided—was to “modernize” and “update” Christianity. So the Catholics gave the nuns outfits that made them look like World War II Wacs. The Protestants set up “beatnik coffee-houses” in church basements for poetry reading and bongo playing. They had the preacher put on a turtleneck sweater and sing “Joe Hill” and “Frankie and Johnny” during the hootenanny at the Sunday vespers. Both the priests and the preachers carried placards in civil rights marches, gay rights marches, women’s rights marches, prisoners’ rights marches, bondage lovers’ rights marches, or any other marches, so long as they might appear hip to the urban young people.

In fact, all these strenuous gestures merely made the churches look like rather awkward and senile groupies of secular movements. The much-sought-after Urban Young People found the Hip Churchman to be an embarrassment, if they noticed him at all. What finally started attracting young people to Christianity was something the churches had absolutely nothing to do with: namely, the psychedelic or hippie movement. The hippies had suddenly made religion look hip. Very few people went into the hippie life with religious intentions, but many came out of it absolutely righteous. The sheer power of the drug LSD is not to be underestimated. It was quite easy for an LSD experience to take the form of a religious vision, particularly if one were among people already so inclined. You would come across someone you had known for years, a pal, only now he was jacked up on LSD and sitting in the middle of the street saying. “I’m in the Pudding at last! I’ve met the Manager!” Without knowing it, many heads were reliving the religious fervor of their grandparents or great-grandparents … the Bible-Belting lectern-pounding amen ten-finger C-majorchord Sister-Martha-at-the-keyboard tent-meeting loblolly piny-woods share-it-brother believers of the nineteenth century. The hippies were religious and incontrovertibly hip at the same time.

Today it is precisely the most rational, intellectual, secularized, modernized, updated, relevant religions—all the brave, forward-looking Ethical Culture, Unitarian, and Swedenborgian movements of only yesterday—that are finished, gasping, breathing their last. What the Urban Young People want from religion is a little Hallelujah! … and talking in tongues! … Praise God! Precisely that! In the most prestigious divinity schools today, Catholic. Presbyterian, and Episcopal, the avant-garde movement, the leading edge, is “charismatic Christianity” … featuring talking in tongues, ululation, visions, holy rolling, and other nonrational, even antirational, practices. Some of the most respectable old-line Protestant congregations, in the most placid suburban settings, have begun to split into the Charismatics and the Easter Christians (“All they care about is being seen in church on Easter”). The Easter Christians still usually control the main Sunday-morning service—but the Charismatics take over on Sunday evening and do the holy roll.

This curious development has breathed new life into the existing Fundamentalists, theosophists, and older salvation seekers of all sorts. Ten years ago, if anyone of wealth, power, or renown had publicly “announced for Christ,” people would have looked at him as if his nose had been eaten away by weevils. Today it happens regularly … Harold Hughes resigns from the U.S. Senate to become an evangelist … Jim Irwin, the astronaut, teams up with a Baptist evangelist in an organization called High Flight … singers like Pat Boone and Anita Bryant announce for Jesus … Charles Colson, the former hardballer of the Nixon administration, announces for Jesus, and the man who is likely to be the next president of the United States, Jimmy Carter, announces for Jesus. Oh Jesus People.

VI. Only One Life

In 1961 a copywriter named Shirley Polykoff was working for the Foote, Cone & Belding advertising agency on the Clairol hair-dye account when she came up with the line: “If I’ve only one life, let me live it as a blonde!” In a single slogan she had summed up what might be described as the secular side of the Me Decade. “If I’ve only one life, let me live it as a—!” (You have only to fill in the blank.)

This formula accounts for much of the popularity of the women’s-liberation or feminist movement. “What does a woman want?” said Freud. Perhaps there are women who want to humble men or reduce their power or achieve equality or even superiority for themselves and their sisters. But for every one such woman, there are nine who simply want to fill in the blank as they see fit. “If I’ve only one life, let me live it as … a free spirit!” (Instead of … a house slave: a cleaning woman, a cook, a nursemaid, a station-wagon hacker, and an occasional household sex aid.) But even that may be overstating it, because often the unconscious desire is nothing more than: Let’s talk about Me. The great unexpected dividend of the feminist movement has been to elevate an ordinary status—woman, housewife—to the level of drama. One’s very existence as a woman —as Me —becomes something all the world analyzes, agonizes over, draws cosmic conclusions from, or, in any event, takes seriously. Every woman becomes Emma Bovary, Cousin Bette, or Nora … or Erica Jong or Consuelo Saah Baehr.

Among men the formula becomes: “If I’ve only one life, let me live it as a … Casanova or a Henry VIII” … instead of a humdrum workadaddy, eternally faithful, except perhaps for a mean little skulking episode here and there, to a woman who now looks old enough to be your aunt and has atrophied calves, and is an embarrassment to be seen with when you take her on trips. The right to shuck overripe wives and take on fresh ones was once seen as the prerogative of kings only, and even then it was scandalous. In the 1950s and 1960s it began to be seen as the prerogative of the rich, the powerful, and the celebrated (Nelson Rockefeller, Henry Ford, and show-business figures), although it retained the odor of scandal. Wife-shucking damaged Adlai Stevenson’s chances of becoming president in 1952 and Rockefeller’s chances of becoming the Republican presidential nominee in 1964 and 1968. Until the 1970s, wife-shucking made it impossible for an astronaut to be chosen to go into space. Today, in the Me Decade, it becomes normal behavior, one of the factors that have pushed the divorce rate above 50 percent.

When Eugene McCarthy filled in the blank in 1972 and shucked his wife, it was hardly noticed. Likewise in the case of several astronauts. When Wayne Hays filled in the blank in 1976 and shucked his wife of 38 years, it did not hurt his career in the slightest, although copulating with the girl in the office was still regarded as scandalous. (Elizabeth Ray filled in the blank in another popular fashion: “If I’ve only one life, let me live it as a … Celebrity!” As did Arthur Bremer, who kept a diary during his stalking of Nixon and, later, George Wallace … with an eye toward the book contract. Which he got.) Some wiseacre has remarked, supposedly with levity, that the federal government may in time have to create reservations for women over 35, to take care of the swarms of shucked wives and widows. In fact, women in precisely those categories have begun setting up communes or “extended families” to provide one another support and companionship in a world without workadaddies. (“If I’ve only one life, why live it as an anachronism?”)

Much of what is now known as “the sexual revolution” has consisted of both women and men filling in the blank this way: “If I’ve only one life, let me live it as … a Swinger!” (Instead of a frustrated, bored monogamist.) In “swinging,” a husband and wife give each other license to copulate with other people. There are no statistics on the subject that mean anything, but I do know that it pops up in conversation today in the most unexpected corners of the country. It is an odd experience to be in De Kalb, Illinois, in the very corncrib of America,* and have some conventional-looking housewife (not housewife, damn it!) come up to you and ask: “Is there much tripling going on in New York?”

“Tripling?”

Tripling turns out to be a practice, in De Kalb, anyway, in which a husband and wife invite a third party—male or female, but more often female—over for an evening of whatever, including polymorphous perversity, even the practices written of in the one-hand magazines, all the things involving tubes and hoses and tourniquets and cups and double-jointed sailors.

One of the satisfactions of this sort of life, quite in addition to the groin spasms, is talk: Let’s talk about Me. Sexual adventurers are given to the most relentless and deadly serious talk… about Me. They quickly succeed in placing themselves onstage in the sexual drama whose outlines were sketched by Freud and then elaborated upon by Wilhelm Reich. Men and women of all sorts, not merely swingers, are given just now to the most earnest sort of talk about the Sexual Me.

A key drama of our own day is Ingmar Bergman’s movie Scenes From a Marriage. In it we see a husband and wife who have good jobs and a well-furnished home but who are unable to “communicate”—to cite one of the signature words of the Me Decade. Then they begin to communicate, and there upon their marriage breaks up and they start divorce proceedings. For the rest of the picture they communicate endlessly, with great candor, but the “relationship”—another signature word—remains doomed. Ironically, the lesson that people seem to draw from this movie has to do with … “the need to communicate.” Scenes From a Marriage is one of those rare works of art, like The Sun Also Rises, that not only succeed in capturing a certain mental atmosphere in fictional form … but also turn around and help radiate it throughout real life. I personally know of two instances in which couples, after years of marriage, went to see Scenes From a Marriage and came home convinced of the “need to communicate.” The discussions began with one of the two saying. Let’s try to be completely candid for once. You tell me exactly what you don’t like about me, and I’ll do the same for you. At this, the starting point, the whole notion is exciting. We’re going to talk about Me! (And I can take it.) I’m going to find out what he (or she) really thinks about me! (Of course, I have my faults, but they’re minor, or else exciting.)

She says. “Go ahead. What don’t you like about me?”

They’re both under the Bergman spell. Nevertheless, a certain sixth sense tells him that they’re on dangerous ground. So he decides to pick something that doesn’t seem too terrible.

“Well,” he says, “one thing that bothers me is that when we meet people for the first time, you never know what to say. Or else you get nervous and start babbling away, and it’s all so banal, it makes me look bad.”

Consciously she’s still telling herself, “I can take it.” But what he has just said begins to seep through her brain like scalding water. What’s he talking about? … makes him look bad? He’s saying I’m unsophisticated, a social liability, and an embarrassment. All those times we’ve gone out, he’s been ashamed of me! (And what makes it worse—it’s the sort of disease for which there’s no cure!) She always knew she was awkward. His crime is: He noticed! He’s known it, too, all along. He’s had contempt for me.

Out loud she says. “Well, I’m afraid there’s nothing I can do about that.”

He detects the petulant note. “Look,” he says. “you’re the one who said to be candid.”

She says, “I know. I want you to be.”

He says, “Well, it’s your turn.”

“Well,” she says, “I’ll tell you something about when we meet people and when we go places. You never clean yourself properly—you don’t know how to wipe yourself. Sometimes we’re standing there talking to people, and there’s … a smell. And I’ll tell you something else. People can tell it’s you.”

And he’s still telling himself, “I can take it”—but what inna namea Christ is this?

He says, “But you’ve never said anything—about anything like that.”

She says, “But I tried to. How many times have I told you about your dirty drawers when you were taking them off at night?”

Somehow this really makes him angry… . All those times … and his mind immediately fastens on Harley Thatcher and his wife, whom he has always wanted to impress… . From underneath my $250 suits—I smelled of shit! What infuriates him is that this is a humiliation from which there’s no recovery. How often have they sniggered about it later?—or not invited me places? Is it something people say every time my name comes up? And all at once he is intensely annoyed with his wife, not because she never told him all these years—but simply because she knows about his disgrace—and she was the one who brought him the bad news!

From that moment on they’re ready to get the skewers in. It’s only a few minutes before they’ve begun trying to sting each other with confessions about their little affairs, their little slipping around, their little coitus on the sly—“Remember that time I told you my flight from Buffalo was canceled?”—and at that juncture the ranks of those who can take it become very thin, indeed. So they communicate with great candor! and break up! and keep on communicating! and then find the relationship hopelessly doomed.

One couple went into group therapy. The other went to a marriage counselor. Both types of therapy are very popular forms, currently, of Let’s talk about Me. This phase of the breakup always provides a rush of exhilaration, for what more exhilarating topic is there than … Me? Through group therapy, marriage counseling, and other forms of “psychological consultation” they can enjoy that same Me euphoria that the very rich have enjoyed for years in psychoanalysis. The cost of the new Me sessions is only $10 to $30 an hour, whereas psychoanalysis runs from $50 to $125. The woman’s exhilaration, however, is soon complicated by the fact that she is (in the typical case) near or beyond the cutoff age of 35 and will have to retire to the reservation.

Well, my dear Mature Moderns … Ingmar never promised you a rose garden!

VII. How You Do It, My Boys!

In September of 1969, in London, on the King’s Road, in a restaurant called Alexander’s, I happened to have dinner with a group of people that included a young American named Jim Haynes and an Australian woman named Germaine Greer. Neither name meant anything to me at the time, although I never forgot Germaine Greer. She was a thin, hard-looking woman with a tremendous curly electric hairdo and the most outrageous Naugahyde mouth I had ever heard on a woman. (I was shocked.) After a while she got bored and set fire to her hair with a match. Two waiters ran over and began beating the flames out with napkins. This made a noise like pigeons taking off in the park. Germaine Greer sat there with a sublime smile on her face, as if to say: “How you do it, my boys!”

Jim Haynes and Germaine Greer had just published the first issue of a newspaper that All London was talking about. It was called Suck. It was founded shortly after Screw in New York, and was one of the progenitors of the sex newspapers that today are so numerous that in Los Angeles it is not uncommon to see fifteen coin-operated newspaper racks in a row on the sidewalk. One will be for the Los Angeles Times, a second for the Herald-Examiner, and the other thirteen for the sex papers. Suck was full of pictures of gaping thighs, moist lips, stiffened giblets, glistening nodules, dirty stories, dirty poems, essays on sexual freedom, and a gossip column detailing the sexual habits of people whose names I assumed were fictitious. Then I came to an item that said, “Anyone who wants group sex in New York and likes fat girls, contact L——— R———,” except that it gave her full name. She was a friend of mine.

Even while Germaine Greer’s hair blazed away, the young American, Jim Haynes, went on with a discourse about the aims of Suck. To put it in a few words, the aim was sexual liberation and, through sexual liberation, the liberation of the spirit of man. If you were listening, to this speech and had read Suck, or even if you hadn’t, you were likely to be watching Jim Haynes’s face for the beginnings of a campy grin, a smirk, a wink, a roll of the eyeballs—something to indicate that he was just having his little joke. But it soon became clear that he was one of those people who exist on a plane quite … Beyond Irony. Whatever it had been for him once, sex had now become a religion, and he had developed a theology in which the orgasm had become a form of spiritual ecstasy.

The same curious journey—from sexology to theology—has become a feature of swinging in the United States. At the Sandstone sex farm in the Santa Monica Mountains, people of all class levels gather for weekends in the nude, and copulate in the living room, on the lawn, out by the pool, on the tennis courts, with the same open, free, liberated spirit as dogs in the park or baboons in a tree. In conversation, however, the atmosphere is quite different. The air becomes humid with solemnity. Close your eyes and you think you’re at a nineteenth-century Wesleyan summer encampment and tent-meeting lecture series. It’s the soul that gets a workout here, brethren. And yet this is not a hypocritical cover-up. It is merely an example of how people in even the most secular manifestation of the Me Decade—free-lance spread-‘em, ziggy-zag rutting—are likely to go through the usual stages… . Let’s talk about Me… . Let’s find the Real Me… . Let’s get rid of all the hypocrisies and impedimenta and false modesties that obscure the Real Me… . Ah! At the apex of my soul is a spark of the Divine … which I perceive in the pure moment of ecstasy (which your textbooks call “the orgasm,” but which I know to be Heaven)… .

This notion even has a pedigree. Many sects, such as the Left-handed Shakti and the Gnostic onanists, have construed the orgasm to be the kairos, the magic moment, the divine ecstasy. There is evidence that the early Mormons and the Oneida movement did likewise. In fact, the notion of some sort of divine ecstasy runs throughout the religious history of the past 2,500 years. As Max Weber and Joachim Wach have illustrated in detail, every major modern religion, as well as countless long-gone minor ones, has originated not with a theology or a set of values or a social goal or even a vague hope of a life hereafter. They have all originated, instead, with a small circle of people who have shared some over-whelming ecstasy or seizure, a “vision,” a “trance,” a hallucination—an actual neurological event, in fact, a dramatic change in metabolism, something that has seemed to light up the entire central nervous system. The Mohammedan movement (Islam) originated in hallucinations, apparently the result of fasting, meditation, and isolation in the darkness of caves, which can induce sensory deprivation. Some of the same practices were common with many types of Buddhists. The early Hindus and Zoroastrians seem to have been animated by a hallucinogenic drug known as soma in India and haoma in Persia. The origins of Christianity are replete with “visions.” The early Christians used wine for ecstatic purposes, to the point where the Apostle Paul (whose conversion on the road to Damascus began with a “vision”) complained that it was degenerating into sheer drunkenness at the services. These great drafts of wine survive in minute quantities in the ritual of Communion. The Bacchic orders, the Sufi, Voodooists, Shakers, and many others used feasts (the bacchanals), ecstatic dancing (“the whirling dervishes”), and other forms of frenzy to achieve the kairos … the moment … here and now! … the feeling! … In every case the believers took the feeling of ecstasy to be the sensation of the light of God flooding into their souls. They felt like vessels of the Divine, of the All-in-One. Only afterward did they try to interpret the experience in the form of theologies, earthly reforms, moral codes, liturgies.

Nor have these been merely the strange practices of the Orient and the Middle East. Every major religious wave that has developed in America has started out the same way: with a flood of ecstatic experiences. The First Great Awakening, as it is known to historians, came in the 1740s and was led by preachers of “the New Light” such as Jonathan Edwards, Gilbert Tennent, and George Whitefield. They and their followers were known as “enthusiasts” and “come-outers,” terms of derision that referred to the frenzied, holy-rolling, pentecostal shout tempo of their services and to their visions, trances, shrieks, and agonies, which are preserved in great Rabelaisian detail in the writings of their detractors.

The Second Great Awakening came in the period from 1825 to 1850 and took the form of a still wilder hoe-down camp-meeting revivalism, of ceremonies in which people barked, bayed, fell down in fits and swoons, rolled on the ground, talked in tongues, and even added a touch of orgy. The Second Awakening originated in western New York State, where so many evangelical movements caught fire it became known as “the Burned-Over District.” Many new seets, such as Oneida and the Shakers, were involved. But so were older ones, such as the evangelical Baptists. The fervor spread throughout the American frontier (and elsewhere) before the Civil War. The most famous sect of the Second Great Awakening was the Mormon movement, founded by a 24-year-old. Joseph Smith, and a small group of youthful comrades. This bunch was regarded as wilder, crazier, more obscene, more of a threat, than the entire lot of hippie communes of the 1960s put together. Smith was shot to death by a lynch mob in Carthage, Illinois, in 1844, which was why the Mormons, now with Brigham Young at the helm, emigrated to Utah. A sect, incidentally, is a religion with no political power. Once the Mormons settled, built, and ruled Utah, Mormonism became a religion sure enough … and eventually wound down to the slow, firm beat of respectability… .

We are now—in the Me Decade—seeing the upward roll (and not yet the crest, by any means) of the third great religious wave in American history, one that historians will very likely term the Third Great Awakening. Like the others it has begun in a flood of ecstasy, achieved through LSD and other psychedelics, orgy, dancing (the New Sufi and the Hare Krishna), meditation, and psychic frenzy (the marathon encounter). This third wave has built up from more diverse and exotic sources than the first two, from therapeutic movements as well as overtly religious movements, from hippies and students of “psi phenomena” and Flying Saucerites as well as charismatic Christians. But other than that, what will historians say about it?

The historian Perry Miller credited the First Great Awakening with helping to pave the way for the American Revolution through its assault on the colonies’ religious establishment and, thereby, on British colonial authority generally. The sociologist Thomas O’Dea credited the Second Great Awakening with creating the atmosphere of Christian asceticism (known as “bleak” on the East Coast) that swept through the Midwest and the West during the nineteenth century and helped make it possible to build communities in the face of great hardship. And the Third Great Awakening? Journalists (historians have not yet tackled the subject) have shown a morbid tendency to regard the various movements in this wave as “fascist.” The hippie movement was often attacked as “fascist” in the late 1960s. Over the past several years a barrage of articles has attacked Scientology, the est movement, and “the Moonies” (followers of the Reverend Sun Myung Moon) along the same lines.

Frankly, this tells us nothing except that journalists bring the same conventional Grim Slide concepts to every subject. The word fascism derives from the old Roman symbol of power and authority, the fasces, a bundle of sticks bound together by thongs (with an ax head protruding from one end). One by one the sticks would be easy to break. Bound together they are invincible Fascist ideology called for binding all classes, all levels, all elements of an entire nation together into a single organization with a single will.

The various movements of the current religious wave attempt very nearly the opposite. They begin with … “Let’s talk about Me.” They begin with the most delicious look inward; with considerable narcissism, in short. When the believers bind together into religions, it is always with a sense of splitting off from the rest of society. We, the enlightened (lit by the sparks at the apexes of our souls), hereby separate ourselves from the lost souls around us. Like all religions before them, they proselytize—but always on promising the opposite of nationalism: a City of Light that is above it all. There is no ecumenical spirit within this Third Great Awakening. If anything, there is a spirit of schism. The contempt the various seers have for one another is breathtaking. One has only to ask, say, Oscar Ichazo of Arica about Carlos Castaneda or Werner Erhard of est to learn that Castaneda is a fake and Erhard is a shallow sloganeer. It’s exhilarating!—to watch the faithful split off from one another to seek ever more perfect and refined crucibles in which to fan the Divine spark … and to talk about Me.

Whatever the Third Great Awakening amounts to, for better or for worse, will have to do with this unprecedented post-World War II American development: the luxury, enjoyed by so many millions of middling folk, of dwelling upon the self. At first glance, Shirley Polykoff’s slogan—“If I’ve only one life, let me live it as a blonde!”—seems like merely another example of a superficial and irritating rhetorical trope ( antanaclasis ) that now happens to be fashionable among advertising copywriters. But in fact the notion of “If I’ve only one life” challenges one of those assumptions of society that are so deep-rooted and ancient, they have no name—they are simply lived by. In this case: man’s age-old belief in serial immortality.

The husband and wife who sacrifice their own ambitions and their material assets in order to provide “a better future” for their children … the soldier who risks his life, or perhaps consciously sacrifices it, in battle … the man who devotes his life to some struggle for “his people” that cannot possibly be won in his lifetime … people (or most of them) who buy life insurance or leave wills … and, for that matter, most women upon becoming pregnant for the first time … are people who conceive of themselves, however unconsciously, as part of a great biological stream. Just as something of their ancestors lives on in them, so will something of them live on in their children … or in their people, their race, their community—for childless people, too, conduct their lives and try to arrange their postmortem affairs with concern for how the great stream is going to flow on. Most people, historically, have not lived their lives as if thinking, “I have only one life to live.” Instead they have lived as if they are living their ancestors’ lives and their offspring’s lives and perhaps their neighbors’ lives as well. They have seen themselves as inseparable from the great tide of chromosomes of which they are created and which they pass on. The mere fact that you were only going to be here a short time and would be dead soon enough did not give you the license to try to climb out of the stream and change the natural order of things. The Chinese, in ancestor worship, have literally worshiped the great tide itself, and not any god or gods. For anyone to renounce the notion of serial immortality, in the West or the East, has been to defy what seems like a law of Nature. Hence the wicked feeling—the excitement!—of “If I’ve only one life, let me live it as a ———!” Fill in the blank, if you dare.

And now many dare it! In Democracy in America, Tocqueville (the inevitable and ubiquitous Tocqueville) saw the American sense of equality itself as disrupting the stream, which he called “time’s pattern”: “Not only does democracy make each man forget his ancestors, it hides his descendants from him, and divides him from his contemporaries; it continually turns him back into himself, and threatens, at last, to enclose him entirely in the solitude of his own heart.” A grim prospect to the good Alexis de T.—but what did he know about … Let’s talk about Me!

Tocqueville’s idea of modern man lost “in the solitude of his own heart” has been brought forward into our time in such terminology as alienation (Marx), anomie (Durkheim), the mass man (Ortega y Gasset), and the lonely crowd (Riesman). The picture is always of a creature uprooted by industrialism, packed together in cities with people he doesn’t know, helpless against massive economic and political shifts—in short, a creature like Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times, a helpless, bewildered, and dispirited slave to the machinery. This victim of modern times has always been a most appealing figure to intellectuals, artists, and architects. The poor devil so obviously needs us to be his Engineers of the Soul, to use a term popular in the Soviet Union in the 1920s. We will pygmalionize this sad lump of clay into a homo novus, a New Man, with a new philosophy, a new aesthetics, not to mention new Bauhaus housing and furniture.

But once the dreary little bastards started getting money in the 1940s, they did an astonishing thing—they took their money and ran. They did something only aristocrats (and intellectuals and artists) were supposed to do—they discovered and started doting on Me! They’ve created the greatest age of individualism in American history! All rules are broken! The prophets are out of business! Where the Third Great Awakening will lead—who can presume to say? One only knows that the great religious waves have a momentum all their own. Neither arguments nor policies nor acts of the legislature have been any match for them in the past. And this one has the mightiest, holiest roll of all, the beat that goes … Me … Me … . Me … Me . . .

- from the archives

- new york magazine

Most viewed

- Madame Clairevoyant: Horoscopes for the Week of April 7–13

- Get Ready for the Solar Eclipse in Aries to Change You

- Behold, the Ballet Sneaker

- Cracks Are Back

- Andrew Huberman’s Mechanisms of Control

- What Quiet on Set Leaves Out Is Just As Damning

- The Case for Marrying an Older Man

- Saturday Night Live Recap: Kristen Wiig Brings Her Friends

What is your email?

This email will be used to sign into all New York sites. By submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy and to receive email correspondence from us.

Sign In To Continue Reading

Create your free account.

Password must be at least 8 characters and contain:

- Lower case letters (a-z)

- Upper case letters (A-Z)

- Numbers (0-9)

- Special Characters (!@#$%^&*)

As part of your account, you’ll receive occasional updates and offers from New York , which you can opt out of anytime.

Subscribe to our newsletter

15 great articles by tom wolfe, on american culture, the last american hero is junior johnson. yes, the me decade, the rich have feelings, too, the secret vice, on technology, what if he’s right, the tinkerings of robert noyce, sorry, but your soul just died, one giant leap to nowhere, on politics, radical chic: that party at lenny’s, mau-mauing the flak catchers.

The Birth of The New Journalism

Stalking the billion-footed beast, the kandy-kolored tangerine-flake streamline baby, the electric kool-aid acid test, see also…, 15 great essays by joan didion, 20 great articles by hunter s. thompson.

About The Electric Typewriter We search the net to bring you the best nonfiction, articles, essays and journalism

Tom Wolfe and the Age of Self-Involvement

There’s writers in there like Pynchon. But if he were a realist. There’s thorough knowledge of American history and the people who wrote it down and made it up. There’s glee in repetition and reinvention, and smart set-ups that read like omissions at first, and omissions that you then make do the work of a smart setup. Tom Wolfe’s signature essay “The ‘Me’ Decade and the Third Great Awakening” is a joyful trip into the American maudlin, dateline 1976. It’s narrated like a novel, the art form Wolfe denied its primus inter pares place in the literary quiver; that is, until he succumbed to it.

Wolfe, who wrote like he dressed – impeccably and with sprezzatura , but in an initially off-putting way – died on Monday, May 14, 2018. His iconoclasm did not end in death. The New York Times obituary managed to get his age and birth date wrong in its first go-around, and required a second correction to fix the title of one of his novels. Much hyperbole, as with any literary death, has accompanied Wolfe’s passing, as has much reflection on his place in the media world, and the media that he placed in the world.

If Wolfe was an icon, he also behaved like one. The white suit he trademark wore, Wolfe said, made him look like a Martian, and that helped people relate to him, tell him their stories, see him as an impartial third, an observer from a disinterested place reporting back to the mothership. Only the mothership sat pat in New York City, sharing the life of the elites he castigated in his most successful novel, Bonfire of the Vanities . Before Wolfe was a novelist, however, lauded and applauded first, panned and criticized for his later works, he was non-fiction writer. A journalist; a New Journalist. In essence, a fiction writer of non-fiction.

“Me”

Reading the “Me Decade” essay, you’ll be struck by what passes for reporting here, even by the standards of the scene-setting New Journalism that Wolfe co-created with, among others, Hunter S. Thompson. In one of the most-cited passages (presumably because it starts the thing off), Wolfe reports from the plush, solvent-cleaned floor of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. His heroine is the woman who screams “hemorrhoids!” when asked to name the one thing in her life she most wants to get rid off. Wolfe smilingly berates her on the self-centeredness of her choice, then goes on to imagine a deep dive into her mind, constructing the story that lies behind that moment of clarity and catharsis:

She begins to feel her hemorrhoids in all their morbid presence. […] Well–for God’s sake!–in her daily life, even at work, especially at work, and she works for a movie distributor, her whole picture of herself was of her… seductive physical presence . […] When she walked into the office each morning, everyone, women as well as men, checked her out. She knew that.

But, alas, the hemorrhoidal “peanut” intervenes (the same essay features a description of Jimmy Carter, so who knows, peanuts may have been on the national mind in America two centuries post Declaration of Independence), messes up that picture, creates a cleavage between how she looks (“The Sexual Princess!”) and what she wants vs. what she thinks about: “As she smiled sublimely at her conquest, she also had to sit on her chair lopsided, with one cheek of her buttocks higher than the other…”

The age of the piece shows. Not just in its inherent unquestioned sexism or casual inclusion of homosexuality as among the host of things people at self-help or self-actualization seminars want to get rid of, or the mentions of lifestyles involving either “Sevilles and 450SL’s” or “Superstar Qiana sport shirts,” things a present-day reader likely will have to punch into a search box. That is, if they don’t just stare at the brand names in confusion for a microsecond and then decide they don’t care enough to even do that.

The age of the piece also presents itself, and somewhat sadly, in the fact that there was a gushing inventiveness to Wolfe’s 70s and 80s pieces of reporting, pieces which he was actually able to get published and paid for, and that’s not something we’re used to anymore. New Journalism, to be sure, was influential. But its excesses have been cut down to size. Journalism, even the highly readable kind, seems tame in comparison today. Not in content, but in language; edited or self-edited into tonal conformity. Even if a writer as gifted as Wolfe produced something in a style as eccentric as Wolfe’s today, it obviously cannot have the same effect. You can only break new ground once. The frivolousness would be muted.

That is not to say that journalism is rulebound now. In an increasingly fragmented media ecosphere, the fraying and frothing fringes, the extremists and rightwing million-dollar pundits hired to be performance artists against the other side, have long lost any semblance of decorum. But inventive, happy about the language they use, knowledgeable and excited to try out and on words for size, to break the molds of the newspaper article headline/standfirst/body text triad or the scripted TV narrative, they are not. And in terms of value: on cable, certainly, money follows the performance. But are writer-journalists highly paid? To the tune of being able to afford 12 rooms in Manhattan ?

Admittedly, there is a “look here” flashiness in a Wolfe essay. There’s that stringing-too-many-words-together-with-hyphens tendency (on Jimmy Carter: “he was of the Missionary lectern-pounding amen ten-finger C-major-chord Sister-Martha-at-the-Yamaha-keyboard loblolly piny-woods Baptist faith”). And some of the things that in 1976 were fresh forty plus years on no longer are.

But these are not just the rantings of a word-heavy Cassandra who doesn’t like the way that America, filled to its cultural gills with baby boomers cusping into adulthood, is suddenly behaving. They are that, but they also are the observation of an astute critic, of someone trained in American Studies by his Yale PhD program, someone whose referential drive-bys include swift freethrows to Perry Miller and Max Weber and snide digs at Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe – a prefigurement here of Wolfe’s more ornate taste in architecture and his longer takedown of the Bauhaus in his 1981 From Bauhaus to Our House . Even if you find, as I do, the criticism of the German-inspired clean, functional architecture and design misguided and overwrought, you cannot deny that, it has in the reverence that acolytes award it, departed from the ideal of a democratic, down-to-earth way of equipping people with living spaces and material goods. As Wolfe writes in a footnote included with “Me Decade”:

Ignored or else held in contempt by working people, Bauhaus design eventually triumphed as a symbol of wealth and privilege […]. [T]he Barcelona chair [.] now sells for $1.680 […]. The high price is due in no small part to the chair’s Worker Housing Honest Materials: stainless steel and leather.

Some of this is just Wolfe being a grouch, a Christopher Lasch-type social critic with more of a flourish and less academic rigor – in his 2006 NEH Jefferson Lecture, for example, Wolfe casually omits both Johann Gottfried Herder and Henri Bergson’s coinages when he talks about “homo loquax,” misidentifying that creature, too, as “talking man” instead of the “chattering man” Bergson had in mind. 1

Tom, “Me,” and You

But Wolfe’s writings contain truly original insight and a rare talent for telling stories of approachable verisimilitude. Ken Kesey, the author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and subject’s of Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test , attested Wolfe that his book was highly accurate. It was a driving narrative about an almost Christlike guru and his “Merry Pranksters” traveling the United States in a VW bus, taking LSD-laced Kool-Aid. Wolfe’s imaginative language made that book as much as its story did. Writing upon the publication of Electric Kool-Aid in 1969, the Guardian 2 summed up Wolfe’s use of language and cadence:

The style uses the repetition and the compressed adjectival forms of a poem, and the reader is pleasantly caught up in the internal rhythms. For all its seeming superabundance of punctuation and participles, every word seems placed with a care and a skill of contrivance which should command respect.

Gay Talese, fellow New Journalist and impeccable dresser, called Wolfe a magician for his use of words. But it was not only words that Wolfe’s writing consisted of. It was ellipses, too, dots, dashes, exclamation marks and transcribed primal screams:

“Eeeeeeeeeooooooohhhhhhhhheeeeeooooooooh!” “Aiaiaiaiaiaiaiaiaiaiaieeeeeeeeeeeeeeohhhhhhhhhheeeeeeaiaiai!”