François Voltaire

- Literature Notes

- Alexander Pope's Essay on Man

- Book Summary

- Character List

- Summary and Analysis

- Chapters II-III

- Chapters IV-VI

- Chapters VII-X

- Chapters XI-XII

- Chapters XIII-XVI

- Chapters XVII-XVIII

- Chapter IXX

- Chapters XX-XXIII

- Chapters XXIV-XXVI

- Chapters XXVII-XXX

- Francois Voltaire Biography

- Critical Essays

- The Philosophy of Leibnitz

- Poème Sur Le Désastre De Lisoonne

- Other Sources of Influence

- Structure and Style

- Satire and Irony

- Essay Questions

- Cite this Literature Note

Critical Essays Alexander Pope's Essay on Man

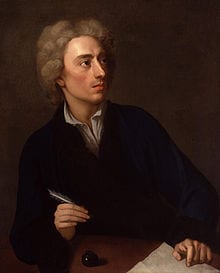

The work that more than any other popularized the optimistic philosophy, not only in England but throughout Europe, was Alexander Pope's Essay on Man (1733-34), a rationalistic effort to justify the ways of God to man philosophically. As has been stated in the introduction, Voltaire had become well acquainted with the English poet during his stay of more than two years in England, and the two had corresponded with each other with a fair degree of regularity when Voltaire returned to the Continent.

Voltaire could have been called a fervent admirer of Pope. He hailed the Essay of Criticism as superior to Horace, and he described the Rape of the Lock as better than Lutrin. When the Essay on Man was published, Voltaire sent a copy to the Norman abbot Du Resnol and may possibly have helped the abbot prepare the first French translation, which was so well received. The very title of his Discours en vers sur l'homme (1738) indicates the extent Voltaire was influenced by Pope. It has been pointed out that at times, he does little more than echo the same thoughts expressed by the English poet. Even as late as 1756, the year in which he published his poem on the destruction of Lisbon, he lauded the author of Essay on Man. In the edition of Lettres philosophiques published in that year, he wrote: "The Essay on Man appears to me to be the most beautiful didactic poem, the most useful, the most sublime that has ever been composed in any language." Perhaps this is no more than another illustration of how Voltaire could vacillate in his attitude as he struggled with the problems posed by the optimistic philosophy in its relation to actual experience. For in the Lisbon poem and in Candide , he picked up Pope's recurring phrase "Whatever is, is right" and made mockery of it: "Tout est bien" in a world filled with misery!

Pope denied that he was indebted to Leibnitz for the ideas that inform his poem, and his word may be accepted. Those ideas were first set forth in England by Anthony Ashley Cowper, Earl of Shaftesbury (1671-1731). They pervade all his works but especially the Moralist. Indeed, several lines in the Essay on Man, particularly in the first Epistle, are simply statements from the Moralist done in verse. Although the question is unsettled and probably will remain so, it is generally believed that Pope was indoctrinated by having read the letters that were prepared for him by Bolingbroke and that provided an exegesis of Shaftesbury's philosophy. The main tenet of this system of natural theology was that one God, all-wise and all-merciful, governed the world providentially for the best. Most important for Shaftesbury was the principle of Harmony and Balance, which he based not on reason but on the general ground of good taste. Believing that God's most characteristic attribute was benevolence, Shaftesbury provided an emphatic endorsement of providentialism.

Following are the major ideas in Essay on Man: (1) a God of infinite wisdom exists; (2) He created a world that is the best of all possible ones; (3) the plenum, or all-embracing whole of the universe, is real and hierarchical; (4) authentic good is that of the whole, not of isolated parts; (5) self-love and social love both motivate humans' conduct; (6) virtue is attainable; (7) "One truth is clear, WHATEVER IS, IS RIGHT." Partial evil, according to Pope, contributes to the universal good. "God sends not ill, if rightly understood." According to this principle, vices, themselves to be deplored, may lead to virtues. For example, motivated by envy, a person may develop courage and wish to emulate the accomplishments of another; and the avaricious person may attain the virtue of prudence. One can easily understand why, from the beginning, many felt that Pope had depended on Leibnitz.

Previous The Philosophy of Leibnitz

Next Poème Sur Le Désastre De Lisoonne

British Literature Wiki

An Essay on Man

“Is the great chain, that draws all to agree, And drawn supports, upheld by God, or Thee?” – Alexander Pope (From “An Essay on Man”)

“Then say not Man’s imperfect, Heav’n in fault; Say rather, Man’s as perfect as he ought.” – Alexander Pope (From “An Essay on Man”)

“All are but parts of one stupendous whole, Whose body Nature is, and God the soul.” – Alexander Pope (From “An Essay on Man”)

Awake, my St. John! leave all meaner things

To low ambition, and the pride of kings., let us (since life can little more supply, than just to look about us and die), expatiate free o’er all this scene of man;, a mighty maze but not without a plan;, a wild, where weed and flow’rs promiscuous shoot;, or garden, tempting with forbidden fruit., together let us beat this ample field,, try what the open, what the covert yield;, the latent tracts, the giddy heights explore, of all who blindly creep, or sightless soar;, eye nature’s walks, shoot folly as it flies,, and catch the manners living as they rise;, laugh where we must, be candid where we can;, but vindicate the ways of god to man. (pope 1-16), background on alexander pope.

Alexander Pope is a British poet who was born in London, England in 1688 (World Biography 1). Growing up during the Augustan Age, his poetry is heavily influenced by common literary qualities of that time, which include classical influence, the importance of human reason and the rules of nature. These qualities are widely represented in Pope’s poetry. Some of Pope’s most notable works are “The Rape of the Lock,” “An Essay on Criticism,” and “An Essay on Man.”

Overview of “An Essay on Man”

“An Essay on Man” was published in 1734 and contained very deep and well thought out philosophical ideas. It is said that these ideas were partially influenced by his friend, Henry St. John Bolingbroke, who Pope addresses in the first line of Epistle I when he says, “Awake, my St. John!”(Pope 1)(World Biography 1) The purpose of the poem is to address the role of humans as part of the “Great Chain of Being.” In other words, it speaks of man as just one small part of an unfathomably complex universe. Pope urges us to learn from what is around us, what we can observe ourselves in nature, and to not pry into God’s business or question his ways; For everything that happens, both good and bad, happens for a reason. This idea is summed up in the very last lines of the poem when he says, “And, Spite of pride in erring reason’s spite, / One truth is clear, Whatever IS, is RIGHT.”(Pope 293-294) The poem is broken up into four epistles each of which is labeled as its own subcategory of the overall work. They are as follows:

- Epistle I – Of the Nature and State of Man, with Respect to the Universe

- Epistle II – Of the Nature and State of Man, with Respect to Himself, as an Individual

- Epistle III – Of the Nature and State of Man, with Respect to Society

- Epistle IV – Of the Nature and State of Man with Respect to Happiness

Epistle 1 Intro In the introduction to Pope’s first Epistle, he summarizes the central thesis of his essay in the last line. The purpose of “An Essay on Man” is then to shift or enhance the reader’s perception of what is natural or correct. By doing this, one would justify the happenings of life, and the workings of God, for there is a reason behind all things that is beyond human understanding. Pope’s endeavor to highlight the infallibility of nature is a key aspect of the Augustan period in literature; a poet’s goal was to convey truth by creating a mirror image of nature. This is envisaged in line 13 when, keeping with the hunting motif, Pope advises his reader to study the behaviors of Nature (as hunter would watch his prey), and to rid of all follies, which we can assume includes all that is unnatural. He also encourages the exploration of one’s surroundings, which provides for a gateway to new discoveries and understandings of our purpose here on Earth. Furthermore, in line 12, Pope hints towards vital middle ground on which we are above beats and below a higher power(s). Those who “blindly creep” are consumed by laziness and a willful ignorance, and just as bad are those who “sightless soar” and believe that they understand more than they can possibly know. Thus, it is imperative that we can strive to gain knowledge while maintaining an acceptance of our mental limits.

1. Pope writes the first section to put the reader into the perspective that he believes to yield the correct view of the universe. He stresses the fact that we can only understand things based on what is around us, embodying the relationship with empiricism that characterizes the Augustan era. He encourages the discovery of new things while remaining within the bounds one has been given. These bounds, or the Chain of Being, designate each living thing’s place in the universe, and only God can see the system in full. Pope is adamant in God’s omniscience, and uses that as a sure sign that we can never reach a level of knowledge comparable to His. In the last line however, he questions whether God or man plays a bigger role in maintaining the chain once it is established.

2. The overarching message in section two is envisaged in one of the last couplets: “Then say not Man’s imperfect, Heav’n in fault; Say rather, Man’s as perfect as he ought.” Pope utilizes this section to explain the folly of “Presumptuous Man,” for the fact that we tend to dwell on our limitations rather than capitalize on our abilities. He emphasizes the rightness of our place in the chain of being, for just as we steer the lives of lesser creatures, God has the ability to pilot our fate. Furthermore, he asserts that because we can only analyze what is around us, we cannot be sure that there is not a greater being or sphere beyond our level of comprehension; it is most logical to perceive the universe as functioning through a hierarchal system.

3. Pope utilizes the beginning of section three to elaborate on the functions of the chain of being. He claims that each creatures’ ignorance, including our own, allows for a full and happy life without the possible burden of understanding our fates. Instead of consuming ourselves with what we cannot know, we instead should place hope in a peaceful “life to come.” Pope connects this after-life to the soul, and colors it with a new focus on a more primitive people, “the Indian,” whose souls have not been distracted by power or greed. As humble and level headed beings, Indian’s, and those who have similar beliefs, see life as the ultimate gift and have no vain desires of becoming greater than Man ought to be.

4. In the fourth stanza, Pope warns against the negative effects of excessive pride. He places his primary examples in those who audaciously judge the work of God and declare one person to be too fortunate and another not fortunate enough. He also satirizes Man’s selfish content in destroying other creatures for his own benefit, while complaining when they believe God to be unjust to Man. Pope capitalizes on his point with the final and resonating couplet: “who but wishes to invert the laws of order, sins against th’ Eternal Cause.” This connects to the previous stanza in which the soul is explored; those who wrestle with their place in the universe will disturb the chain of being and warrant punishment instead of gain rewards in the after-life.

5. In the beginning of the fifth stanza, Pope personifies Pride and provides selfish answers to questions regarding the state of the universe. He depicts Pride as a hoarder of all gifts that Nature yields. The image of Nature as a benefactor and Man as her avaricious recipient is countered in the next set of lines: Pope instead entertains the possible faults of Nature in natural disasters such as earthquakes and storms. However, he denies this possibility on the grounds that there is a larger purpose behind all happenings and that God acts by “general laws.” Finally, Pope considers the emergence of evil in human nature and concludes that we are not in a place that allows us to explain such things–blaming God for human misdeeds is again an act of pride.

6. Stanza six connects the different inhabitants of the earth to their rightful place and shows why things are the way they should be. After highlighting the happiness in which most creatures live, Pope facetiously questions if God is unkind to man alone. He asks this because man consistently yearns for the abilities specific to those outside of his sphere, and in that way can never be content in his existence. Pope counters the notorious greed of Man by illustrating the pointless emptiness that would accompany a world in which Man was omnipotent. Furthermore, he describes a blissful lifestyle as one centered around one’s own sphere, without the distraction of seeking unattainable heights.

7. The seventh stanza explores the vastness of the sensory and cognitive spectrums in relation to all earthly creatures. Pope uses an example related to each of the five senses to conjure an image that emphasizes the intricacies with which all things are tailored. For instance, he references a bee’s sensitivity, which allows it to collect only that which is beneficial amid dangerous substances. Pope then moves to the differences in mental abilities along the chain of being. These mental functions are broken down into instinct, reflection, memory, and reason. Pope believes reason to trump all, which of course is the one function specific to Man. Reason thus allows man to synthesize the means to function in ways that are unnatural to himself.

8. In section 8 Pope emphasizes the depths to which the universe extends in all aspects of life. This includes the literal depths of the ocean and the reversed extent of the sky, as well as the vastness that lies between God and Man and Man and the simpler creatures of the earth. Regardless of one’s place in the chain of being however, the removal of one link creates just as much of an impact as any other. Pope stresses the maintenance of order so as to prevent the breaking down of the universe.

9. In the ninth stanza, Pope once again puts the pride and greed of man into perspective. He compares man’s complaints of being subordinate to God to an eye or an ear rejecting its service to the mind. This image drives home the point that all things are specifically designed to ensure that the universe functions properly. Pope ends this stanza with the Augustan belief that Nature permeates all things, and thus constitutes the body of the world, where God characterizes the soul.

10. In the tenth stanza, Pope secures the end of Epistle 1 by advising the reader on how to secure as many blessings as possible, whether that be on earth or in the after life. He highlights the impudence in viewing God’s order as imperfect and emphasizes the fact that true bliss can only be experienced through an acceptance of one’s necessary weaknesses. Pope exemplifies this acceptance of weakness in the last lines of Epistle 1 in which he considers the incomprehensible, whether seemingly miraculous or disastrous, to at least be correct, if nothing else.

1. Epistle II is broken up into six smaller sections, each of which has a specific focus. The first section explains that man must not look to God for answers to the great questions of life, for he will never find the answers. As was explained in the first epistle, man is incapable of truly knowing anything about the things that are higher than he is on the “Great Chain of Being.” For this reason, the way to achieve the greatest knowledge possible is to study man, the greatest thing we have the ability to comprehend. Pope emphasizes the complexity of man in an effort to show that understanding of anything greater than that would simply be too much for any person to fully comprehend. He explains this complexity with lines such as, “Created half to rise, and half to fall; / Great lord of all things, yet a prey to all / Sole judge of truth, in endless error hurl’d: / The glory, jest, and riddle of the world!”(15-18) These lines say that we are created for two purposes, to live and die. We are the most intellectual creatures on Earth, and while we have control over most things, we are still set up to die in some way by the end. We are a great gift of God to the Earth with enormous capabilities, yet in the end we really amount to nothing. Pope describes this contrast between our intellectual capabilities and our inevitable fate as a “riddle” of the world. The first section of Epistle II closes by saying that man is to go out and study what is around him. He is to study science to understand all that he can about his existence and the universe in which he lives, but to fully achieve this knowledge he must rid himself of all vices that may slow down this process.

2. The second section of Epistle II tells of the two principles of human nature and how they are to perfectly balance each other out in order for man to achieve all that he is capable of achieving. These two principles are self-love and reason. He explains that all good things can be attributed to the proper use of these two principles and that all bad things stem from their improper use. Pope further discusses the two principles by claiming that self-love is what causes man to do what he desires, but reason is what allows him to know how to stay in line. He follows that with an interesting comparison of man to a flower by saying man is “Fix’d like a plant on his peculiar spot, / To draw nutrition, propagate and rot,” (Pope 62-63) and also of man to a meteor by saying, “Or, meteor-like, flame lawless thro’ the void, / Destroying others, by himself destroy’d.” (Pope 64-65) These comparisons show that man, according to Pope, is born, takes his toll on the Earth, and then dies, and it is all part of a larger plan. The rest of section two continues to talk about the relationship between self-love and reason and closes with a strong argument. Humans all seek pleasure, but only with a good sense of reason can they restrain themselves from becoming greedy. His final remarks are strong, stating that, “Pleasure, or wrong or rightly understood, / Our greatest evil, or our greatest good,”(Pope 90-91) which means that pleasure in moderation can be a great thing for man, but without the balance that reason produces, a pursuit of pleasure can have terrible consequences.

3. Part III of Epistle II also pertains to the idea of self-love and reason working together. It starts out talking about passions and how they are inherently selfish, but if the means to which these passions are sought out are fair, then there has been a proper balance of self-love and reason. Pope describes love, hope and joy as being “Fair treasure’s smiling train,”(Pope 117) while hate, fear and grief are “The family of pain.”(Pope 118) Too much of any of these things, whether they be from the negative or positive side, is a bad thing. There is a ratio of good to bad that man must reach to have a well balanced mind. We learn, grow, and gain character and perspective through the elements of this “Family of pain,”(Pope 118) while we get great rewards from love, hope and joy. While our goal as humans is to seek our pleasure and follow certain desires, there is always one overall passion that lives deep within us that guides us throughout life. The main points to take away from Section III of this Epistle is that there are many aspects to the life of man, and these aspects, both positive and negative, need to coexist harmoniously to achieve that balance for which man should strive.

4. The fourth section of Epistle II is very short. It starts off by asking what allows us to determine the difference between good and bad. The next line answers this question by saying that it is the God within our minds that allows us to make such judgements. This section finishes up by discussing virtue and vice. The relationship between these two qualities are interesting, for they can exist on their own but most often mix, and there is a fine line between something being a virtue and becoming a vice.

5. Section V is even shorter than section IV with just fourteen lines. It speaks only of the quality of vice. Vices are temptations that man must face on a consistent basis. A line that stands out from this says that when it comes to vices, “We first endure, then pity, then embrace.”(Pope 218) This means that vices start off as something we know is wrong, but over time they become an instinctive part of us if reason is not there to push them away.

6. Section VI, the final section of Epistle II, relates many of the ideas from Sections I-V back to ideas from Epistle I. It works as a conclusion that ties in the main theme of Epistle II, which mainly speaks of the different components of man that balance each other out to form an infinitely complex creature, into the idea from Epistle I that man is created as part of a larger plan with all of his qualities given to him for a specific purpose. It is a way of looking at both negative and positive aspects of life and being content with them both, for they are all part of God’s purpose of creating the universe. This idea is well concluded in the third to last line of this Epistle when Pope says, “Ev’n mean self-love becomes, by force divine.”(Pope 288) This shows that even a negative quality in a man, such as excessive self-love without the stability of reason, is technically divine, for it is what God intended as part of the balance of the universe.

Contributors

- Dan Connolly

- Nicole Petrone

“Alexander Pope.” : The Poetry Foundation . N.p., n.d. Web. 14 May 2013. < http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/alexander-pope >.

“Alexander Pope Photos.” Rugu RSS . N.p., n.d. Web. 14 May 2013. < http://www.rugusavay.com/alexander-pope-photos/ >.

“An Essay on Man: Epistle 1 by Alexander Pope • 81 Poems by Alexander PopeEdit.” An Essay on Man: Epistle 1 by Alexander Pope Classic Famous Poet . N.p., n.d. Web. 14 May 2013. < http://allpoetry.com/poem/8448567-An_Essay_on_Man_Epistle_1-by-Alexander_Pope >.

“An Essay on Man: Epistle II.” By Alexander Pope : The Poetry Foundation. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 May 2013. < http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/174166 >.

“Benjamin Franklin’s Mastodon Tooth.” About.com Archaeology . N.p., n.d. Web. 14 May 2013. < http://archaeology.about.com/od/artandartifacts/ss/franklin_4.htm >.

“First Edition of An Essay on Man by Alexander Pope Offered by The Manhattan Rare Book Company.” First Edition of An Essay on Man by Alexander Pope Offered by The Manhattan Rare Book Company. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 May 2013. < http://www.manhattanrarebooks- literature.com/pope_essay.htm>.

Alexander Pope's Essay on Man: An Introduction

David cody , associate professor of english, hartwick college.

Victorian Web Home —> Some Pre-Victorian Authors —> Neoclassicism —> Alexander Pope ]

The Essay on Man is a philosophical poem, written, characteristically, in heroic couplets , and published between 1732 and 1734. Pope intended it as the centerpiece of a proposed system of ethics to be put forth in poetic form: it is in fact a fragment of a larger work which Pope planned but did not live to complete. It is an attempt to justify, as Milton had attempted to vindicate, the ways of God to Man, and a warning that man himself is not, as, in his pride, he seems to believe, the center of all things. Though not explicitly Christian, the Essay makes the implicit assumption that man is fallen and unregenerate, and that he must seek his own salvation.

The "Essay" consists of four epistles, addressed to Lord Bolingbroke, and derived, to some extent, from some of Bolingbroke's own fragmentary philosophical writings, as well as from ideas expressed by the deistic third Earl of Shaftesbury. Pope sets out to demonstrate that no matter how imperfect, complex, inscrutable, and disturbingly full of evil the Universe may appear to be, it does function in a rational fashion, according to natural laws; and is, in fact, considered as a whole, a perfect work of God. It appears imperfect to us only because our perceptions are limited by our feeble moral and intellectual capacity. His conclusion is that we must learn to accept our position in the Great Chain of Being — a "middle state," below that of the angels but above that of the beasts — in which we can, at least potentially, lead happy and virtuous lives.

Epistle I concerns itself with the nature of man and with his place in the universe; Epistle II, with man as an individual; Epistle III, with man in relation to human society, to the political and social hierarchies; and Epistle IV, with man's pursuit of happiness in this world. An Essay on Man was a controversial work in Pope's day, praised by some and criticized by others, primarily because it appeared to contemporary critics that its emphasis, in spite of its themes, was primarily poetic and not, strictly speaking, philosophical in any really coherent sense: Dr. Johnson , never one to mince words, and possessed, in any case, of views upon the subject which differed materially from those which Pope had set forth, noted dryly (in what is surely one of the most back-handed literary compliments of all time) that "Never were penury of knowledge and vulgarity of sentiment so happily disguised." It is a subtler work, however, than perhaps Johnson realized: G. Wilson Knight has made the perceptive comment that the poem is not a "static scheme" but a "living organism," (like Twickenham ) and that it must be understood as such.

Considered as a whole, the Essay on Man is an affirmative poem of faith: life seems chaotic and patternless to man when he is in the midst of it, but is in fact a coherent portion of a divinely ordered plan. In Pope's world God exists, and he is benificent: his universe is an ordered place. The limited intellect of man can perceive only a tiny portion of this order, and can experience only partial truths, and hence must rely on hope, which leads to faith. Man must be cognizant of his rather insignificant position in the grand scheme of things: those things which he covets most — riches, power, fame — prove to be worthless in the greater context of which he is only dimly aware. In his place, it is man's duty to strive to be good, even if he is doomed, because of his inherent frailty, to fail in his attempt. Do you find Pope's argument convincing? In what ways can we relate the Essay on Man to works like Swift's Gulliver's Travels , Johnson's "The Vanity of Human Wishes" ( text ), Tennyson's In Memoriam and Eliot's The Wasteland ?

Incorporated in the Victorian Web July 2000

An Essay on Man

30 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Epistle Summaries & Analyses

Symbols & Motifs

Literary Devices

Further Reading & Resources

Discussion Questions

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Summary Epistle 1: “Of the Nature and State of Man with Respect to the Universe”

Lines 1-16 are a dedication to Henry St. John, a friend of Pope’s. The speaker urges St. John to abandon the “meaner things” (Line 1) in life and turn his attention toward the higher, grander sphere by reflecting on human nature and God.

In section 1 (Lines 17-34), the speaker argues that humans cannot see the universe from God’s perspective . Therefore, people cannot understand the entirety of the universe. The universe is composed of “worlds unnumber’d” (Line 21); only God can see how everything is connected through “nice dependencies” (Line 30). The speaker compares these connections to a “great chain” (Line 33).

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,300+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,950+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Ready to dive in?

Get unlimited access to SuperSummary for only $ 0.70 /week

Related Titles

By Alexander Pope

An Essay on Criticism

Alexander Pope

Eloisa to Abelard

The Dunciad

The Rape of the Lock

Featured Collections

Philosophy, logic, & ethics.

View Collection

Religion & Spirituality

School book list titles, valentine's day reads: the theme of love.

Essay on Man, by Alexander Pope

Transcribed from the 1891 Cassell & Company edition by Les Bowler.

An Essay on Man . moral essays and satires

By ALEXANDER POPE.

CASSELL & COMPANY, Limited : london , paris & melbourne . 1891.

INTRODUCTION.

Pope’s life as a writer falls into three periods, answering fairly enough to the three reigns in which he worked. Under Queen Anne he was an original poet, but made little money by his verses; under George I. he was chiefly a translator, and made much money by satisfying the French-classical taste with versions of the “Iliad” and “Odyssey.” Under George I. he also edited Shakespeare, but with little profit to himself; for Shakespeare was but a Philistine in the eyes of the French-classical critics. But as the eighteenth century grew slowly to its work, signs of a deepening interest in the real issues of life distracted men’s attention from the culture of the snuff-box and the fan. As Pope’s genius ripened, the best part of the world in which he worked was pressing forward, as a mariner who will no longer hug the coast but crowds all sail to cross the storms of a wide unknown sea. Pope’s poetry thus deepened with the course of time, and the third period of his life, which fell within the reign of George II., was that in which he produced the “Essay on Man,” the “Moral Essays,” and the “Satires.” These deal wholly with aspects of human life and the great questions they raise, according throughout with the doctrine of the poet, and of the reasoning world about him in his latter day, that “the proper study of mankind is Man.”

Wrongs in high places, and the private infamy of many who enforced the doctrines of the Church, had produced in earnest men a vigorous antagonism. Tyranny and unreason of low-minded advocates had brought religion itself into question; and profligacy of courtiers, each worshipping the golden calf seen in his mirror, had spread another form of scepticism. The intellectual scepticism, based upon an honest search for truth, could end only in making truth the surer by its questionings. The other form of scepticism, which might be traced in England from the low-minded frivolities of the court of Charles the Second, was widely spread among the weak, whose minds flinched from all earnest thought. They swelled the number of the army of bold questioners upon the ways of God to Man, but they were an idle rout of camp-followers, not combatants; they simply ate, and drank, and died.

In 1697, Pierre Bayle published at Rotterdam, his “Historical and Critical Dictionary,” in which the lives of men were associated with a comment that suggested, from the ills of life, the absence of divine care in the shaping of the world. Doubt was born of the corruption of society; Nature and Man were said to be against faith in the rule of a God, wise, just, and merciful. In 1710, after Bayle’s death, Leibnitz, a German philosopher then resident in Paris, wrote in French a book, with a title formed from Greek words meaning Justice of God, Theodicee, in which he met Bayle’s argument by reasoning that what we cannot understand confuses us, because we see only the parts of a great whole. Bayle, he said, is now in Heaven, and from his place by the throne of God, he sees the harmony of the great Universe, and doubts no more. We see only a little part in which are many details that have purposes beyond our ken. The argument of Leibnitz’s Theodicee was widely used; and although Pope said that he had never read the Theodicee, his “Essay on Man” has a like argument. When any book has a wide influence upon opinion, its general ideas pass into the minds of many people who have never read it. Many now talk about evolution and natural selection, who have never read a line of Darwin.

In the reign of George the Second, questionings did spread that went to the roots of all religious faith, and many earnest minds were busying themselves with problems of the state of Man, and of the evidence of God in the life of man, and in the course of Nature. Out of this came, nearly at the same time, two works wholly different in method and in tone—so different, that at first sight it may seem absurd to speak of them together. They were Pope’s “Essay on Man,” and Butler’s “Analogy of Religion, Natural and Revealed, to the Constitution and Course of Nature.”

Butler’s “Analogy” was published in 1736; of the “Essay on Man,” the first two Epistles appeared in 1732, the Third Epistle in 1733, the Fourth in 1734, and the closing Universal Hymn in 1738. It may seem even more absurd to name Pope’s “Essay on Man” in the same breath with Milton’s “Paradise Lost;” but to the best of his knowledge and power, in his smaller way, according to his nature and the questions of his time, Pope was, like Milton, endeavouring “to justify the ways of God to Man.” He even borrowed Milton’s line for his own poem, only weakening the verb, and said that he sought to “vindicate the ways of God to Man.” In Milton’s day the questioning all centred in the doctrine of the “Fall of Man,” and questions of God’s Justice were associated with debate on fate, fore-knowledge, and free will. In Pope’s day the question was not theological, but went to the root of all faith in existence of a God, by declaring that the state of Man and of the world about him met such faith with an absolute denial. Pope’s argument, good or bad, had nothing to do with questions of theology. Like Butler’s, it sought for grounds of faith in the conditions on which doubt was rested. Milton sought to set forth the story of the Fall in such way as to show that God was love. Pope dealt with the question of God in Nature, and the world of Man.

Pope’s argument was attacked with violence my M. de Crousaz, Professor of Philosophy and Mathematics in the University of Lausanne, and defended by Warburton, then chaplain to the Prince of Wales, in six letters published in 1739, and a seventh in 1740, for which Pope (who died in 1744) was deeply grateful. His offence in the eyes of de Crousaz was that he had left out of account all doctrines of orthodox theology. But if he had been orthodox of the orthodox, his argument obviously could have been directed only to the form of doubt it sought to overcome. And when his closing hymn was condemned as the freethinker’s hymn, its censurers surely forgot that their arguments against it would equally apply to the Lord’s Prayer, of which it is, in some degree, a paraphrase.

The first design of the Essay on Man arranged it into four books, each consisting of a distinct group of Epistles. The First Book, in four Epistles, was to treat of man in the abstract, and of his relation to the Universe. That is the whole work as we have it now. The Second Book was to treat of Man Intellectual; the Third Book, of Man Social, including ties to Church and State; the Fourth Book, of Man Moral, was to illustrate abstract truth by sketches of character. This part of the design is represented by the Moral Essays, of which four were written, to which was added, as a fifth, the Epistle to Addison which had been written much earlier, in 1715, and first published in 1720. The four Moral essays are two pairs. One pair is upon the Characters of Men and on the Characters of Women, which would have formed the opening of the subject of the Fourth Book of the Essay: the other pair shows character expressed through a right or a wrong use of Riches: in fact, Money and Morals. The four Epistles were published separately. The fourth (to the Earl of Burlington) was first published in 1731, its title then being “Of Taste;” the third (to Lord Bathurst) followed in 1732, the year of the publication of the first two Epistles on the “Essay on Man.” In 1733, the year of publication of the Third Epistle of the “Essay on Man,” Pope published his Moral Essay of the “Characters of Men.” In 1734 followed the Fourth Epistle of the “Essay on Man;” and in 1735 the “Characters of Women,” addressed to Martha Blount, the woman whom Pope loved, though he was withheld by a frail body from marriage. Thus the two works were, in fact, produced together, parts of one design.

Pope’s Satires, which still deal with characters of men, followed immediately, some appearing in a folio in January, 1735. That part of the epistle to Arbuthnot forming the Prologue, which gives a character of Addison, as Atticus, had been sketched more than twelve years before, and earlier sketches of some smaller critics were introduced; but the beginning and the end, the parts in which Pope spoke of himself and of his father and mother, and his friend Dr. Arbuthnot, were written in 1733 and 1734. Then follows an imitation of the first Epistle of the Second Book of the Satires of Horace, concerning which Pope told a friend, “When I had a fever one winter in town that confined me to my room for five or six days, Lord Bolingbroke, who came to see me, happened to take up a Horace that lay on the table, and, turning it over, dropped on the first satire in the Second Book, which begins, ‘Sunt, quibus in satira.’ He observed how well that would suit my case if I were to imitate it in English. After he was gone, I read it over, translated it in a morning or two, and sent it to press in a week or a fortnight after” (February, 1733). “And this was the occasion of my imitating some others of the Satires and Epistles.” The two dialogues finally used as the Epilogue to the Satires were first published in the year 1738, with the name of the year, “Seventeen Hundred and Thirty-eight.” Samuel Johnson’s “London,” his first bid for recognition, appeared in the same week, and excited in Pope not admiration only, but some active endeavour to be useful to its author.

The reader of Pope, as of every author, is advised to begin by letting him say what he has to say, in his own manner to an open mind that seeks only to receive the impressions which the writer wishes to convey. First let the mind and spirit of the writer come into free, full contact with the mind and spirit of the reader, whose attitude at the first reading should be simply receptive. Such reading is the condition precedent to all true judgment of a writer’s work. All criticism that is not so grounded spreads as fog over a poet’s page. Read, reader, for yourself, without once pausing to remember what you have been told to think.

POPE’S POEMS.

An essay on man. to h. st. john lord bolingbroke., the design..

Having proposed to write some pieces of Human Life and Manners, such as (to use my Lord Bacon’s expression) come home to Men’s Business and Bosoms, I thought it more satisfactory to begin with considering Man in the abstract, his Nature and his State; since, to prove any moral duty, to enforce any moral precept, or to examine the perfection or imperfection of any creature whatsoever, it is necessary first to know what condition and relation it is placed in, and what is the proper end and purpose of its being.

The science of Human Nature is, like all other sciences, reduced to a few clear points: there are not many certain truths in this world. It is therefore in the anatomy of the Mind as in that of the Body; more good will accrue to mankind by attending to the large, open, and perceptible parts, than by studying too much such finer nerves and vessels, the conformations and uses of which will for ever escape our observation. The disputes are all upon these last, and, I will venture to say, they have less sharpened the wits than the hearts of men against each other, and have diminished the practice more than advanced the theory of Morality. If I could flatter myself that this Essay has any merit, it is in steering betwixt the extremes of doctrines seemingly opposite, in passing over terms utterly unintelligible, and in forming a temperate yet not inconsistent, and a short yet not imperfect system of Ethics.

This I might have done in prose, but I chose verse, and even rhyme, for two reasons. The one will appear obvious; that principles, maxims, or precepts so written, both strike the reader more strongly at first, and are more easily retained by him afterwards: the other may seem odd, but is true, I found I could express them more shortly this way than in prose itself; and nothing is more certain, than that much of the force as well as grace of arguments or instructions depends on their conciseness. I was unable to treat this part of my subject more in detail, without becoming dry and tedious; or more poetically, without sacrificing perspicuity to ornament, without wandering from the precision, or breaking the chain of reasoning: if any man can unite all these without diminution of any of them I freely confess he will compass a thing above my capacity.

What is now published is only to be considered as a general Map of Man, marking out no more than the greater parts, their extent, their limits, and their connection, and leaving the particular to be more fully delineated in the charts which are to follow. Consequently, these Epistles in their progress (if I have health and leisure to make any progress) will be less dry, and more susceptible of poetical ornament. I am here only opening the fountains, and clearing the passage. To deduce the rivers, to follow them in their course, and to observe their effects, may be a task more agreeable. P.

ARGUMENT OF EPISTLE I.

Of the Nature and State of Man, with respect to the Universe.

Of Man in the abstract. I. That we can judge only with regard to our own system, being ignorant of the relations of systems and things, v.17, etc. II. That Man is not to be deemed imperfect, but a being suited to his place and rank in the Creation, agreeable to the general Order of Things, and conformable to Ends and Relations to him unknown, v.35, etc. III. That it is partly upon his ignorance of future events, and partly upon the hope of future state, that all his happiness in the present depends, v.77, etc. IV. The pride of aiming at more knowledge, and pretending to more Perfection, the cause of Man’s error and misery. The impiety of putting himself in the place of God, and judging of the fitness or unfitness, perfection or imperfection, justice or injustice of His dispensations, v.109, etc. V. The absurdity of conceiting himself the final cause of the Creation, or expecting that perfection in the moral world, which is not in the natural, v.131, etc. VI. The unreasonableness of his complaints against Providence, while on the one hand he demands the Perfections of the Angels, and on the other the bodily qualifications of the Brutes; though to possess any of the sensitive faculties in a higher degree would render him miserable, v.173, etc. VII. That throughout the whole visible world, an universal order and gradation in the sensual and mental faculties is observed, which cause is a subordination of creature to creature, and of all creatures to Man. The gradations of sense, instinct, thought, reflection, reason; that Reason alone countervails all the other faculties, v.207. VIII. How much further this order and subordination of living creatures may extend, above and below us; were any part of which broken, not that part only, but the whole connected creation, must be destroyed, v.233. IX. The extravagance, madness, and pride of such a desire, v.250. X. The consequence of all, the absolute submission due to Providence, both as to our present and future state, v.281, etc., to the end.

Awake, my St. John! leave all meaner things To low ambition, and the pride of kings. Let us (since life can little more supply Than just to look about us and to die) Expatiate free o’er all this scene of man; A mighty maze! but not without a plan; A wild, where weeds and flowers promiscuous shoot; Or garden tempting with forbidden fruit. Together let us beat this ample field, Try what the open, what the covert yield; The latent tracts, the giddy heights, explore Of all who blindly creep, or sightless soar; Eye Nature’s walks, shoot Folly as it flies, And catch the manners living as they rise; Laugh where we must, be candid where we can; But vindicate the ways of God to man.

I. Say first, of God above, or man below What can we reason, but from what we know? Of man, what see we but his station here, From which to reason, or to which refer? Through worlds unnumbered though the God be known, ’Tis ours to trace Him only in our own. He, who through vast immensity can pierce, See worlds on worlds compose one universe, Observe how system into system runs, What other planets circle other suns, What varied being peoples every star, May tell why Heaven has made us as we are. But of this frame, the bearings, and the ties, The strong connections, nice dependencies, Gradations just, has thy pervading soul Looked through? or can a part contain the whole? Is the great chain, that draws all to agree, And drawn supports, upheld by God, or thee?

II. Presumptuous man! the reason wouldst thou find, Why formed so weak, so little, and so blind? First, if thou canst, the harder reason guess, Why formed no weaker, blinder, and no less; Ask of thy mother earth, why oaks are made Taller or stronger than the weeds they shade? Or ask of yonder argent fields above, Why Jove’s satellites are less than Jove? Of systems possible, if ’tis confest That wisdom infinite must form the best, Where all must full or not coherent be, And all that rises, rise in due degree; Then in the scale of reasoning life, ’tis plain, There must be, somewhere, such a rank as man: And all the question (wrangle e’er so long) Is only this, if God has placed him wrong? Respecting man, whatever wrong we call, May, must be right, as relative to all. In human works, though laboured on with pain, A thousand movements scarce one purpose gain; In God’s one single can its end produce; Yet serves to second too some other use. So man, who here seems principal alone, Perhaps acts second to some sphere unknown, Touches some wheel, or verges to some goal; ’Tis but a part we see, and not a whole. When the proud steed shall know why man restrains His fiery course, or drives him o’er the plains: When the dull ox, why now he breaks the clod, Is now a victim, and now Egypt’s god: Then shall man’s pride and dulness comprehend His actions’, passions’, being’s, use and end; Why doing, suffering, checked, impelled; and why This hour a slave, the next a deity. Then say not man’s imperfect, Heaven in fault; Say rather man’s as perfect as he ought: His knowledge measured to his state and place; His time a moment, and a point his space. If to be perfect in a certain sphere, What matter, soon or late, or here or there? The blest to-day is as completely so, As who began a thousand years ago.

III. Heaven from all creatures hides the book of Fate, All but the page prescribed, their present state: From brutes what men, from men what spirits know: Or who could suffer being here below? The lamb thy riot dooms to bleed to-day, Had he thy reason, would he skip and play? Pleased to the last, he crops the flowery food, And licks the hand just raised to shed his blood. Oh, blindness to the future! kindly given, That each may fill the circle, marked by Heaven: Who sees with equal eye, as God of all, A hero perish, or a sparrow fall, Atoms or systems into ruin hurled, And now a bubble burst, and now a world. Hope humbly, then; with trembling pinions soar; Wait the great teacher Death; and God adore. What future bliss, He gives not thee to know, But gives that hope to be thy blessing now. Hope springs eternal in the human breast: Man never is, but always to be blest: The soul, uneasy and confined from home, Rests and expatiates in a life to come. Lo, the poor Indian! whose untutored mind Sees God in clouds, or hears Him in the wind; His soul, proud science never taught to stray Far as the solar walk, or milky way; Yet simple Nature to his hope has given, Behind the cloud-topped hill, an humbler heaven; Some safer world in depth of woods embraced, Some happier island in the watery waste, Where slaves once more their native land behold, No fiends torment, no Christians thirst for gold. To be, contents his natural desire, He asks no angel’s wing, no seraph’s fire; But thinks, admitted to that equal sky, His faithful dog shall bear him company.

IV. Go, wiser thou! and, in thy scale of sense, Weigh thy opinion against providence; Call imperfection what thou fanciest such, Say, here He gives too little, there too much; Destroy all creatures for thy sport or gust, Yet cry, if man’s unhappy, God’s unjust; If man alone engross not Heaven’s high care, Alone made perfect here, immortal there: Snatch from His hand the balance and the rod, Re-judge His justice, be the God of God. In pride, in reasoning pride, our error lies; All quit their sphere, and rush into the skies. Pride still is aiming at the blest abodes, Men would be angels, angels would be gods. Aspiring to be gods, if angels fell, Aspiring to be angels, men rebel: And who but wishes to invert the laws Of order, sins against the Eternal Cause.

V. Ask for what end the heavenly bodies shine, Earth for whose use? Pride answers, “’Tis for mine: For me kind Nature wakes her genial power, Suckles each herb, and spreads out every flower; Annual for me, the grape, the rose renew The juice nectareous, and the balmy dew; For me, the mine a thousand treasures brings; For me, health gushes from a thousand springs; Seas roll to waft me, suns to light me rise; My footstool earth, my canopy the skies.” But errs not Nature from this gracious end, From burning suns when livid deaths descend, When earthquakes swallow, or when tempests sweep Towns to one grave, whole nations to the deep? “No, (’tis replied) the first Almighty Cause Acts not by partial, but by general laws; The exceptions few; some change since all began; And what created perfect?”—Why then man? If the great end be human happiness, Then Nature deviates; and can man do less? As much that end a constant course requires Of showers and sunshine, as of man’s desires; As much eternal springs and cloudless skies, As men for ever temperate, calm, and wise. If plagues or earthquakes break not Heaven’s design, Why then a Borgia, or a Catiline? Who knows but He, whose hand the lightning forms, Who heaves old ocean, and who wings the storms; Pours fierce ambition in a Cæsar’s mind, Or turns young Ammon loose to scourge mankind? From pride, from pride, our very reasoning springs; Account for moral, as for natural things: Why charge we heaven in those, in these acquit? In both, to reason right is to submit. Better for us, perhaps, it might appear, Were there all harmony, all virtue here; That never air or ocean felt the wind; That never passion discomposed the mind. But all subsists by elemental strife; And passions are the elements of life. The general order, since the whole began, Is kept in nature, and is kept in man.

VI. What would this man? Now upward will he soar, And little less than angel, would be more; Now looking downwards, just as grieved appears To want the strength of bulls, the fur of bears Made for his use all creatures if he call, Say what their use, had he the powers of all? Nature to these, without profusion, kind, The proper organs, proper powers assigned; Each seeming want compensated of course, Here with degrees of swiftness, there of force; All in exact proportion to the state; Nothing to add, and nothing to abate. Each beast, each insect, happy in its own: Is Heaven unkind to man, and man alone? Shall he alone, whom rational we call, Be pleased with nothing, if not blessed with all? The bliss of man (could pride that blessing find) Is not to act or think beyond mankind; No powers of body or of soul to share, But what his nature and his state can bear. Why has not man a microscopic eye? For this plain reason, man is not a fly. Say what the use, were finer optics given, To inspect a mite, not comprehend the heaven? Or touch, if tremblingly alive all o’er, To smart and agonize at every pore? Or quick effluvia darting through the brain, Die of a rose in aromatic pain? If Nature thundered in his opening ears, And stunned him with the music of the spheres, How would he wish that Heaven had left him still The whispering zephyr, and the purling rill? Who finds not Providence all good and wise, Alike in what it gives, and what denies?

VII. Far as Creation’s ample range extends, The scale of sensual, mental powers ascends: Mark how it mounts, to man’s imperial race, From the green myriads in the peopled grass: What modes of sight betwixt each wide extreme, The mole’s dim curtain, and the lynx’s beam: Of smell, the headlong lioness between, And hound sagacious on the tainted green: Of hearing, from the life that fills the flood, To that which warbles through the vernal wood: The spider’s touch, how exquisitely fine! Feels at each thread, and lives along the line: In the nice bee, what sense so subtly true From poisonous herbs extracts the healing dew? How instinct varies in the grovelling swine, Compared, half-reasoning elephant, with thine! ’Twixt that, and reason, what a nice barrier, For ever separate, yet for ever near! Remembrance and reflection how allayed; What thin partitions sense from thought divide: And middle natures, how they long to join, Yet never passed the insuperable line! Without this just gradation, could they be Subjected, these to those, or all to thee? The powers of all subdued by thee alone, Is not thy reason all these powers in one?

VIII. See, through this air, this ocean, and this earth, All matter quick, and bursting into birth. Above, how high, progressive life may go! Around, how wide! how deep extend below? Vast chain of being! which from God began, Natures ethereal, human, angel, man, Beast, bird, fish, insect, what no eye can see, No glass can reach; from Infinite to thee, From thee to nothing. On superior powers Were we to press, inferior might on ours: Or in the full creation leave a void, Where, one step broken, the great scale’s destroyed: From Nature’s chain whatever link you strike, Tenth or ten thousandth, breaks the chain alike. And, if each system in gradation roll Alike essential to the amazing whole, The least confusion but in one, not all That system only, but the whole must fall. Let earth unbalanced from her orbit fly, Planets and suns run lawless through the sky; Let ruling angels from their spheres be hurled, Being on being wrecked, and world on world; Heaven’s whole foundations to their centre nod, And nature tremble to the throne of God. All this dread order break—for whom? for thee? Vile worm!—Oh, madness! pride! impiety!

IX. What if the foot, ordained the dust to tread, Or hand, to toil, aspired to be the head? What if the head, the eye, or ear repined To serve mere engines to the ruling mind? Just as absurd for any part to claim To be another, in this general frame: Just as absurd, to mourn the tasks or pains, The great directing Mind of All ordains. All are but parts of one stupendous whole, Whose body Nature is, and God the soul; That, changed through all, and yet in all the same; Great in the earth, as in the ethereal frame; Warms in the sun, refreshes in the breeze, Glows in the stars, and blossoms in the trees, Lives through all life, extends through all extent, Spreads undivided, operates unspent; Breathes in our soul, informs our mortal part, As full, as perfect, in a hair as heart: As full, as perfect, in vile man that mourns, As the rapt seraph that adores and burns: To him no high, no low, no great, no small; He fills, he bounds, connects, and equals all.

X. Cease, then, nor order imperfection name: Our proper bliss depends on what we blame. Know thy own point: this kind, this due degree Of blindness, weakness, Heaven bestows on thee. Submit. In this, or any other sphere, Secure to be as blest as thou canst bear: Safe in the hand of one disposing Power, Or in the natal, or the mortal hour. All nature is but art, unknown to thee; All chance, direction, which thou canst not see; All discord, harmony not understood; All partial evil, universal good: And, spite of pride in erring reason’s spite, One truth is clear, whatever is, is right.

ARGUMENT OF EPISTLE II.

Of the Nature and State of Man with respect to Himself, as an Individual.

I. The business of Man not to pry into God, but to study himself. His Middle Nature; his Powers and Frailties, v.1 to 19. The Limits of his Capacity, v.19, etc. II. The two Principles of Man, Self-love and Reason, both necessary, v.53, etc. Self-love the stronger, and why, v.67, etc. Their end the same, v.81, etc. III. The Passions, and their use, v.93 to 130. The predominant Passion, and its force, v.132 to 160. Its Necessity, in directing Men to different purposes, v.165, etc. Its providential Use, in fixing our Principle, and ascertaining our Virtue, v.177. IV. Virtue and Vice joined in our mixed Nature; the limits near, yet the things separate and evident: What is the Office of Reason, v.202 to 216. V. How odious Vice in itself, and how we deceive ourselves into it, v.217. VI. That, however, the Ends of Providence and general Good are answered in our Passions and Imperfections, v.238, etc. How usefully these are distributed to all Orders of Men, v.241. How useful they are to Society, v.251. And to the Individuals, v.263. In every state, and every age of life, v.273, etc.

EPISTLE II.

I. Know, then, thyself, presume not God to scan; The proper study of mankind is man. Placed on this isthmus of a middle state, A being darkly wise, and rudely great: With too much knowledge for the sceptic side, With too much weakness for the stoic’s pride, He hangs between; in doubt to act, or rest; In doubt to deem himself a god, or beast; In doubt his mind or body to prefer; Born but to die, and reasoning but to err; Alike in ignorance, his reason such, Whether he thinks too little, or too much: Chaos of thought and passion, all confused; Still by himself abused, or disabused; Created half to rise, and half to fall; Great lord of all things, yet a prey to all; Sole judge of truth, in endless error hurled: The glory, jest, and riddle of the world! Go, wondrous creature! mount where science guides, Go, measure earth, weigh air, and state the tides; Instruct the planets in what orbs to run, Correct old time, and regulate the sun; Go, soar with Plato to th’ empyreal sphere, To the first good, first perfect, and first fair; Or tread the mazy round his followers trod, And quitting sense call imitating God; As Eastern priests in giddy circles run, And turn their heads to imitate the sun. Go, teach Eternal Wisdom how to rule— Then drop into thyself, and be a fool! Superior beings, when of late they saw A mortal man unfold all Nature’s law, Admired such wisdom in an earthly shape And showed a Newton as we show an ape. Could he, whose rules the rapid comet bind, Describe or fix one movement of his mind? Who saw its fires here rise, and there descend, Explain his own beginning, or his end? Alas, what wonder! man’s superior part Unchecked may rise, and climb from art to art; But when his own great work is but begun, What reason weaves, by passion is undone. Trace Science, then, with Modesty thy guide; First strip off all her equipage of pride; Deduct what is but vanity or dress, Or learning’s luxury, or idleness; Or tricks to show the stretch of human brain, Mere curious pleasure, or ingenious pain; Expunge the whole, or lop th’ excrescent parts Of all our vices have created arts; Then see how little the remaining sum, Which served the past, and must the times to come!

II. Two principles in human nature reign; Self-love to urge, and reason, to restrain; Nor this a good, nor that a bad we call, Each works its end, to move or govern all And to their proper operation still, Ascribe all good; to their improper, ill. Self-love, the spring of motion, acts the soul; Reason’s comparing balance rules the whole. Man, but for that, no action could attend, And but for this, were active to no end: Fixed like a plant on his peculiar spot, To draw nutrition, propagate, and rot; Or, meteor-like, flame lawless through the void, Destroying others, by himself destroyed. Most strength the moving principle requires; Active its task, it prompts, impels, inspires. Sedate and quiet the comparing lies, Formed but to check, deliberate, and advise. Self-love still stronger, as its objects nigh; Reason’s at distance, and in prospect lie: That sees immediate good by present sense; Reason, the future and the consequence. Thicker than arguments, temptations throng. At best more watchful this, but that more strong. The action of the stronger to suspend, Reason still use, to reason still attend. Attention, habit and experience gains; Each strengthens reason, and self-love restrains. Let subtle schoolmen teach these friends to fight, More studious to divide than to unite; And grace and virtue, sense and reason split, With all the rash dexterity of wit. Wits, just like fools, at war about a name, Have full as oft no meaning, or the same. Self-love and reason to one end aspire, Pain their aversion, pleasure their desire; But greedy that, its object would devour, This taste the honey, and not wound the flower: Pleasure, or wrong or rightly understood, Our greatest evil, or our greatest good.

III. Modes of self-love the passions we may call; ’Tis real good, or seeming, moves them all: But since not every good we can divide, And reason bids us for our own provide; Passions, though selfish, if their means be fair, List under Reason, and deserve her care; Those, that imparted, court a nobler aim, Exalt their kind, and take some virtue’s name. In lazy apathy let stoics boast Their virtue fixed; ’tis fixed as in a frost; Contracted all, retiring to the breast; But strength of mind is exercise, not rest: The rising tempest puts in act the soul, Parts it may ravage, but preserves the whole. On life’s vast ocean diversely we sail, Reason the card, but passion is the gale; Nor God alone in the still calm we find, He mounts the storm, and walks upon the wind. Passions, like elements, though born to fight, Yet, mixed and softened, in his work unite: These, ’tis enough to temper and employ; But what composes man, can man destroy? Suffice that Reason keep to Nature’s road, Subject, compound them, follow her and God. Love, hope, and joy, fair pleasure’s smiling train, Hate, fear, and grief, the family of pain, These mixed with art, and to due bounds confined, Make and maintain the balance of the mind; The lights and shades, whose well-accorded strife Gives all the strength and colour of our life. Pleasures are ever in our hands or eyes; And when in act they cease, in prospect rise: Present to grasp, and future still to find, The whole employ of body and of mind. All spread their charms, but charm not all alike; On different senses different objects strike; Hence different passions more or less inflame, As strong or weak, the organs of the frame; And hence once master passion in the breast, Like Aaron’s serpent, swallows up the rest. As man, perhaps, the moment of his breath Receives the lurking principle of death; The young disease that must subdue at length, Grows with his growth, and strengthens with his strength: So, cast and mingled with his very frame, The mind’s disease, its ruling passion came; Each vital humour which should feed the whole, Soon flows to this, in body and in soul: Whatever warms the heart, or fills the head, As the mind opens, and its functions spread, Imagination plies her dangerous art, And pours it all upon the peccant part. Nature its mother, habit is its nurse; Wit, spirit, faculties, but make it worse; Reason itself but gives it edge and power; As Heaven’s blest beam turns vinegar more sour. We, wretched subjects, though to lawful sway, In this weak queen some favourite still obey: Ah! if she lend not arms, as well as rules, What can she more than tell us we are fools? Teach us to mourn our nature, not to mend, A sharp accuser, but a helpless friend! Or from a judge turn pleader, to persuade The choice we make, or justify it made; Proud of an easy conquest all along, She but removes weak passions for the strong; So, when small humours gather to a gout, The doctor fancies he has driven them out. Yes, Nature’s road must ever be preferred; Reason is here no guide, but still a guard: ’Tis hers to rectify, not overthrow, And treat this passion more as friend than foe: A mightier power the strong direction sends, And several men impels to several ends: Like varying winds, by other passions tossed, This drives them constant to a certain coast. Let power or knowledge, gold or glory, please, Or (oft more strong than all) the love of ease; Through life ’tis followed, even at life’s expense; The merchant’s toil, the sage’s indolence, The monk’s humility, the hero’s pride, All, all alike, find reason on their side. The eternal art, educing good from ill, Grafts on this passion our best principle: ’Tis thus the mercury of man is fixed, Strong grows the virtue with his nature mixed; The dross cements what else were too refined, And in one interest body acts with mind. As fruits, ungrateful to the planter’s care, On savage stocks inserted, learn to bear; The surest virtues thus from passions shoot, Wild nature’s vigour working at the root. What crops of wit and honesty appear From spleen, from obstinacy, hate, or fear! See anger, zeal and fortitude supply; Even avarice, prudence; sloth, philosophy; Lust, through some certain strainers well refined, Is gentle love, and charms all womankind; Envy, to which th’ ignoble mind’s a slave, Is emulation in the learned or brave; Nor virtue, male or female, can we name, But what will grow on pride, or grow on shame. Thus Nature gives us (let it check our pride) The virtue nearest to our vice allied: Reason the bias turns to good from ill And Nero reigns a Titus, if he will. The fiery soul abhorred in Catiline, In Decius charms, in Curtius is divine: The same ambition can destroy or save, And makes a patriot as it makes a knave. This light and darkness in our chaos joined, What shall divide? The God within the mind. Extremes in nature equal ends produce, In man they join to some mysterious use; Though each by turns the other’s bound invade, As, in some well-wrought picture, light and shade, And oft so mix, the difference is too nice Where ends the virtue or begins the vice. Fools! who from hence into the notion fall, That vice or virtue there is none at all. If white and black blend, soften, and unite A thousand ways, is there no black or white? Ask your own heart, and nothing is so plain; ’Tis to mistake them, costs the time and pain. Vice is a monster of so frightful mien, As, to be hated, needs but to be seen; Yet seen too oft, familiar with her face, We first endure, then pity, then embrace. But where th’ extreme of vice, was ne’er agreed: Ask where’s the north? at York, ’tis on the Tweed; In Scotland, at the Orcades; and there, At Greenland, Zembla, or the Lord knows where. No creature owns it in the first degree, But thinks his neighbour farther gone than he; Even those who dwell beneath its very zone, Or never feel the rage, or never own; What happier nations shrink at with affright, The hard inhabitant contends is right. Virtuous and vicious every man must be, Few in th’ extreme, but all in the degree, The rogue and fool by fits is fair and wise; And even the best, by fits, what they despise. ’Tis but by parts we follow good or ill; For, vice or virtue, self directs it still; Each individual seeks a several goal; But Heaven’s great view is one, and that the whole. That counter-works each folly and caprice; That disappoints th’ effect of every vice; That, happy frailties to all ranks applied, Shame to the virgin, to the matron pride, Fear to the statesman, rashness to the chief, To kings presumption, and to crowds belief: That, virtue’s ends from vanity can raise, Which seeks no interest, no reward but praise; And build on wants, and on defects of mind, The joy, the peace, the glory of mankind. Heaven forming each on other to depend, A master, or a servant, or a friend, Bids each on other for assistance call, Till one man’s weakness grows the strength of all. Wants, frailties, passions, closer still ally The common interest, or endear the tie. To these we owe true friendship, love sincere, Each home-felt joy that life inherits here; Yet from the same we learn, in its decline, Those joys, those loves, those interests to resign; Taught half by reason, half by mere decay, To welcome death, and calmly pass away. Whate’er the passion, knowledge, fame, or pelf, Not one will change his neighbour with himself. The learned is happy nature to explore, The fool is happy that he knows no more; The rich is happy in the plenty given, The poor contents him with the care of Heaven. See the blind beggar dance, the cripple sing, The sot a hero, lunatic a king; The starving chemist in his golden views Supremely blest, the poet in his muse. See some strange comfort every state attend, And pride bestowed on all, a common friend; See some fit passion every age supply, Hope travels through, nor quits us when we die. Behold the child, by Nature’s kindly law, Pleased with a rattle, tickled with a straw: Some livelier plaything gives his youth delight, A little louder, but as empty quite: Scarves, garters, gold, amuse his riper stage, And beads and prayer-books are the toys of age: Pleased with this bauble still, as that before; Till tired he sleeps, and life’s poor play is o’er. Meanwhile opinion gilds with varying rays Those painted clouds that beautify our days; Each want of happiness by hope supplied, And each vacuity of sense by pride: These build as fast as knowledge can destroy; In folly’s cup still laughs the bubble, joy; One prospect lost, another still we gain; And not a vanity is given in vain; Even mean self-love becomes, by force divine, The scale to measure others’ wants by thine. See! and confess, one comfort still must rise, ’Tis this, though man’s a fool, yet God is wise.

ARGUMENT OF EPISTLE III.

Of the Nature and State of Man with respect to Society.

I. The whole Universe one system of Society, v.7, etc. Nothing made wholly for itself, nor yet wholly for another, v.27. The happiness of Animals mutual, v.49. II. Reason or Instinct operate alike to the good of each Individual, v.79. Reason or Instinct operate also to Society, in all Animals, v.109. III. How far Society carried by Instinct, v.115. How much farther by Reason, v.128. IV. Of that which is called the State of Nature, v.144. Reason instructed by Instinct in the invention of Arts, v.166, and in the Forms of Society, v.176. V. Origin of Political Societies, v.196. Origin of Monarchy, v.207. Patriarchal Government, v.212. VI. Origin of true Religion and Government, from the same principle, of Love, v.231, etc. Origin of Superstition and Tyranny, from the same principle, of Fear, v.237, etc. The Influence of Self-love operating to the social and public Good, v.266. Restoration of true Religion and Government on their first principle, v.285. Mixed Government, v.288. Various forms of each, and the true end of all, v.300, etc.

EPISTLE III.

Here, then, we rest: “The Universal Cause Acts to one end, but acts by various laws.” In all the madness of superfluous health, The trim of pride, the impudence of wealth, Let this great truth be present night and day; But most be present, if we preach or pray. Look round our world; behold the chain of love Combining all below and all above. See plastic Nature working to this end, The single atoms each to other tend, Attract, attracted to, the next in place Formed and impelled its neighbour to embrace. See matter next, with various life endued, Press to one centre still, the general good. See dying vegetables life sustain, See life dissolving vegetate again: All forms that perish other forms supply (By turns we catch the vital breath, and die), Like bubbles on the sea of matter borne, They rise, they break, and to that sea return. Nothing is foreign: parts relate to whole; One all-extending, all-preserving soul Connects each being, greatest with the least; Made beast in aid of man, and man of beast; All served, all serving: nothing stands alone; The chain holds on, and where it ends, unknown. Has God, thou fool! worked solely for thy Thy good, Thy joy, thy pastime, thy attire, thy food? Who for thy table feeds the wanton fawn, For him as kindly spread the flowery lawn: Is it for thee the lark ascends and sings? Joy tunes his voice, joy elevates his wings. Is it for thee the linnet pours his throat? Loves of his own and raptures swell the note. The bounding steed you pompously bestride, Shares with his lord the pleasure and the pride. Is thine alone the seed that strews the plain? The birds of heaven shall vindicate their grain. Thine the full harvest of the golden year? Part pays, and justly, the deserving steer: The hog, that ploughs not nor obeys thy call, Lives on the labours of this lord of all. Know, Nature’s children all divide her care; The fur that warms a monarch, warmed a bear. While man exclaims, “See all things for my use!” “See man for mine!” replies a pampered goose: And just as short of reason he must fall, Who thinks all made for one, not one for all. Grant that the powerful still the weak control; Be man the wit and tyrant of the whole: Nature that tyrant checks; he only knows, And helps, another creature’s wants and woes. Say, will the falcon, stooping from above, Smit with her varying plumage, spare the dove? Admires the jay the insect’s gilded wings? Or hears the hawk when Philomela sings? Man cares for all: to birds he gives his woods, To beasts his pastures, and to fish his floods; For some his interest prompts him to provide, For more his pleasure, yet for more his pride: All feed on one vain patron, and enjoy The extensive blessing of his luxury. That very life his learned hunger craves, He saves from famine, from the savage saves; Nay, feasts the animal he dooms his feast, And, till he ends the being, makes it blest; Which sees no more the stroke, or feels the pain, Than favoured man by touch ethereal slain. The creature had his feast of life before; Thou too must perish when thy feast is o’er! To each unthinking being, Heaven, a friend, Gives not the useless knowledge of its end: To man imparts it; but with such a view As, while he dreads it, makes him hope it too; The hour concealed, and so remote the fear, Death still draws nearer, never seeming near. Great standing miracle! that Heaven assigned Its only thinking thing this turn of mind.

II. Whether with reason, or with instinct blest, Know, all enjoy that power which suits them best; To bliss alike by that direction tend, And find the means proportioned to their end. Say, where full instinct is the unerring guide, What pope or council can they need beside? Reason, however able, cool at best, Cares not for service, or but serves when pressed, Stays till we call, and then not often near; But honest instinct comes a volunteer, Sure never to o’er-shoot, but just to hit; While still too wide or short is human wit; Sure by quick nature happiness to gain, Which heavier reason labours at in vain, This too serves always, reason never long; One must go right, the other may go wrong. See then the acting and comparing powers One in their nature, which are two in ours; And reason raise o’er instinct as you can, In this ’tis God directs, in that ’tis man. Who taught the nations of the field and wood To shun their poison, and to choose their food? Prescient, the tides or tempests to withstand, Build on the wave, or arch beneath the sand? Who made the spider parallels design, Sure as Demoivre, without rule or line? Who did the stork, Columbus-like, explore Heavens not his own, and worlds unknown before? Who calls the council, states the certain day, Who forms the phalanx, and who points the way?

III. God in the nature of each being founds Its proper bliss, and sets its proper bounds: But as He framed a whole, the whole to bless, On mutual wants built mutual happiness: So from the first, eternal order ran, And creature linked to creature, man to man. Whate’er of life all-quickening ether keeps, Or breathes through air, or shoots beneath the deeps, Or pours profuse on earth, one nature feeds The vital flame, and swells the genial seeds. Not man alone, but all that roam the wood, Or wing the sky, or roll along the flood, Each loves itself, but not itself alone, Each sex desires alike, till two are one. Nor ends the pleasure with the fierce embrace; They love themselves, a third time, in their race. Thus beast and bird their common charge attend, The mothers nurse it, and the sires defend; The young dismissed to wander earth or air, There stops the instinct, and there ends the care; The link dissolves, each seeks a fresh embrace, Another love succeeds, another race. A longer care man’s helpless kind demands; That longer care contracts more lasting bands: Reflection, reason, still the ties improve, At once extend the interest and the love; With choice we fix, with sympathy we burn; Each virtue in each passion takes its turn; And still new needs, new helps, new habits rise. That graft benevolence on charities. Still as one brood, and as another rose, These natural love maintained, habitual those. The last, scarce ripened into perfect man, Saw helpless him from whom their life began: Memory and forecast just returns engage, That pointed back to youth, this on to age; While pleasure, gratitude, and hope combined, Still spread the interest, and preserved the kind.