In gun debate, both sides have evidence to back them up

Ph.D. Student in Political Science, University of Missouri-Columbia

Kinder Institute Assistant Professor of Constitutional Democracy, University of Missouri-Columbia

Disclosure statement

Jennifer Selin has received funding for her research on the executive branch from the Administrative Conference of the United States. In addition, she has received funding for her research on Congress from the Dirksen Congressional Center and the Center for Effective Lawmaking.

Zach Lang does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

Gun control is back in the U.S. political debate, in the wake of mass shootings in California, Boulder and Atlanta.

Democrats see stricter gun control as a step toward addressing the problem. In March 2021, as the House of Representatives passed two gun control bills, Speaker Nancy Pelosi claimed that the “ solutions will save lives .”

Many Republicans disagree, arguing as Sen. Ted Cruz has that proposed laws seeking to require background checks on all firearms sales and transfers and to ban assault weapons are “ ridiculous theater ” that fail to reduce mass shootings.

As two political scientists trained in data analysis , we set out to determine whether gun control legislation actually prevents mass shootings. We collected data on all mass shootings that occurred between February 1980 and February 2020. We then examined key information on the perpetrators, weapons used and laws in effect at the time of shooting.

Our research, which is yet to be published in an academic journal, suggests that there is statistical evidence to support both parties’ positions about gun control legislation.

While stricter gun control laws may make mass shootings slightly less common, our research suggests that the rhetoric of both parties may not tell the full story. Rather than federal gun control laws, policies that focus on violence prevention at the community or individual levels may be more effective at preventing mass shooting deaths.

Mass shootings in the past 40 years

We defined a mass shooting as a single incident in which a perpetrator with no connection to gang activity or organized crime shot and killed three or more people. This is similar to the definition Congress uses .

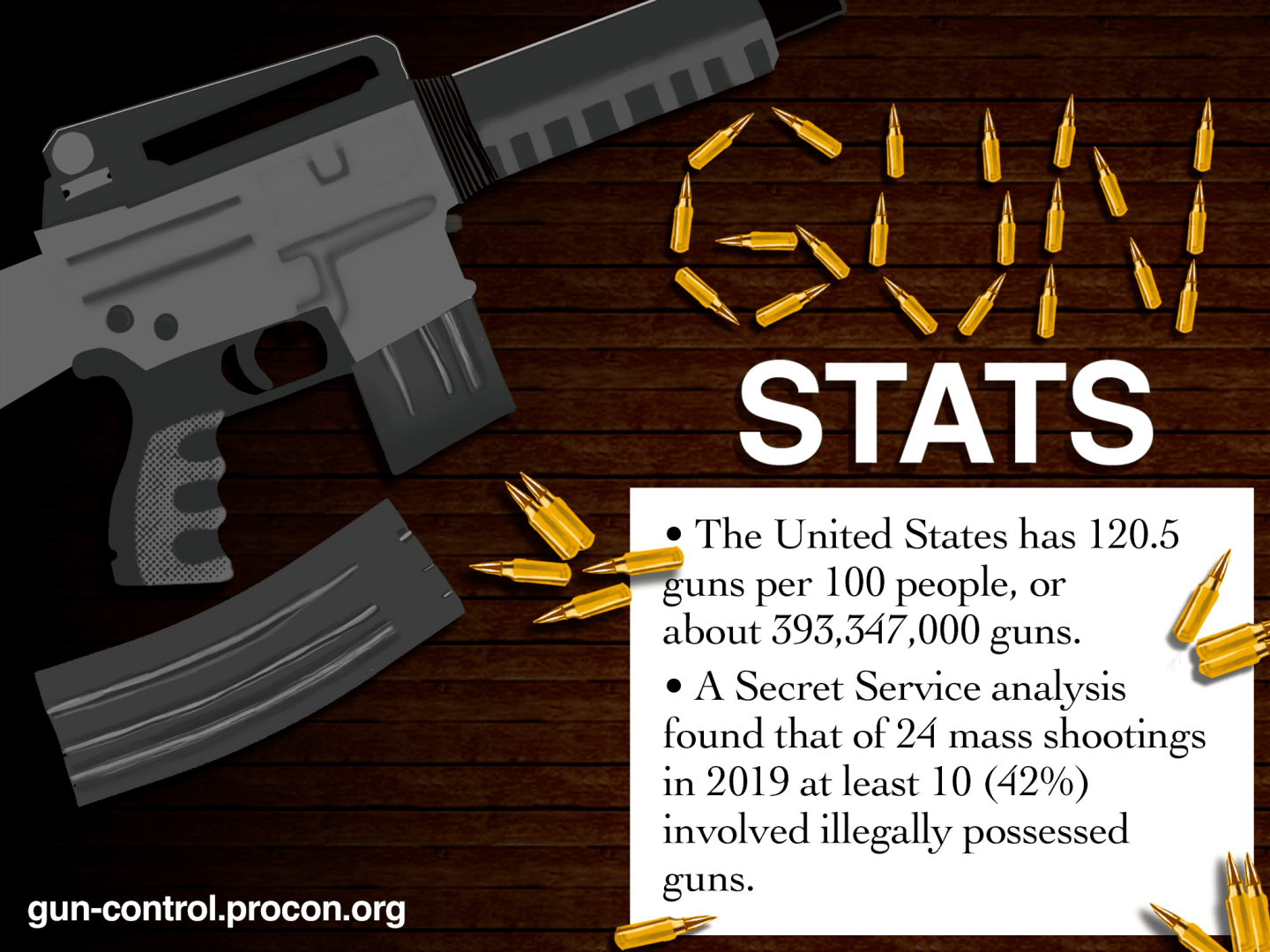

We found there were 112 of these events between 1980 and 2020; the number of mass shootings each year has increased over time. An overwhelming majority of mass shooters – 87% of them – obtained their firearms legally. Nearly all shooters – 93% – shot their victims in the same state where they obtained their weapons.

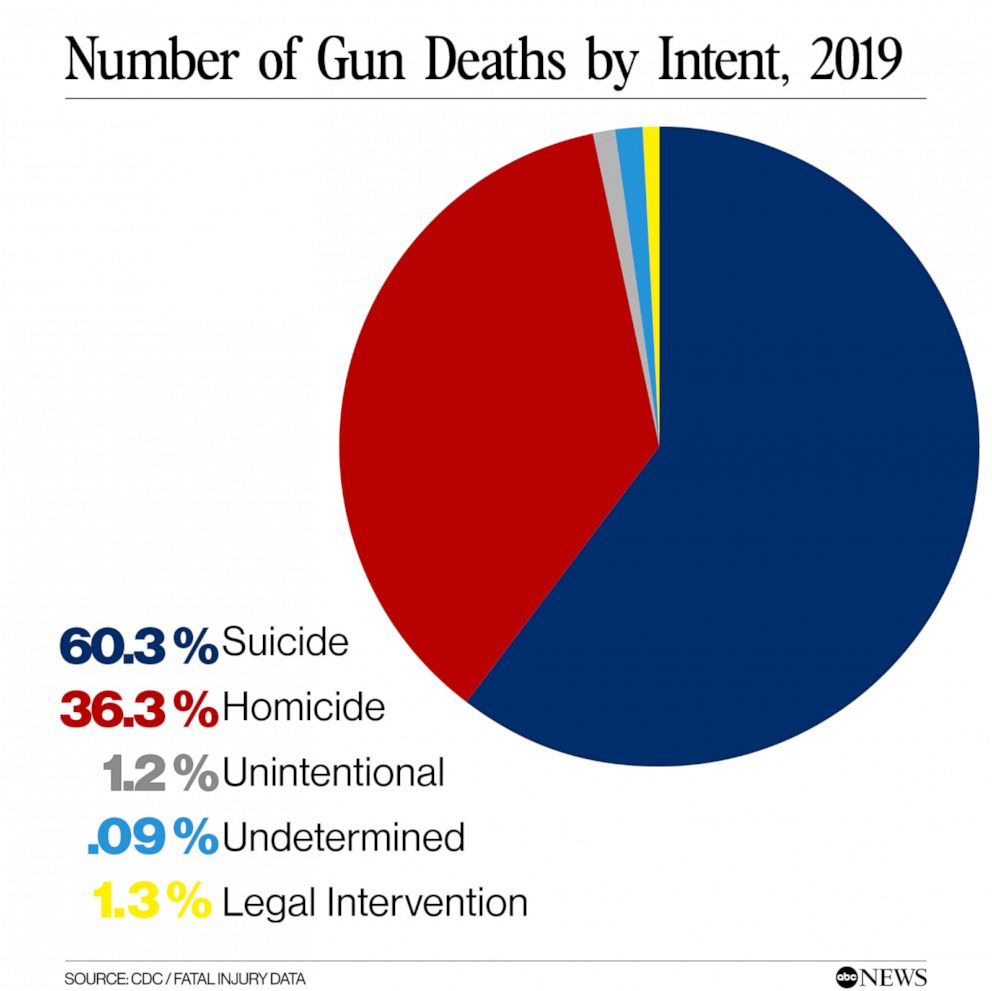

These facts suggest that existing gun laws and regulations governing gun purchases and firearms that cross state lines may not be working to reduce mass shootings. Our study did not address whether or how other forms of gun violence might be affected by those laws.

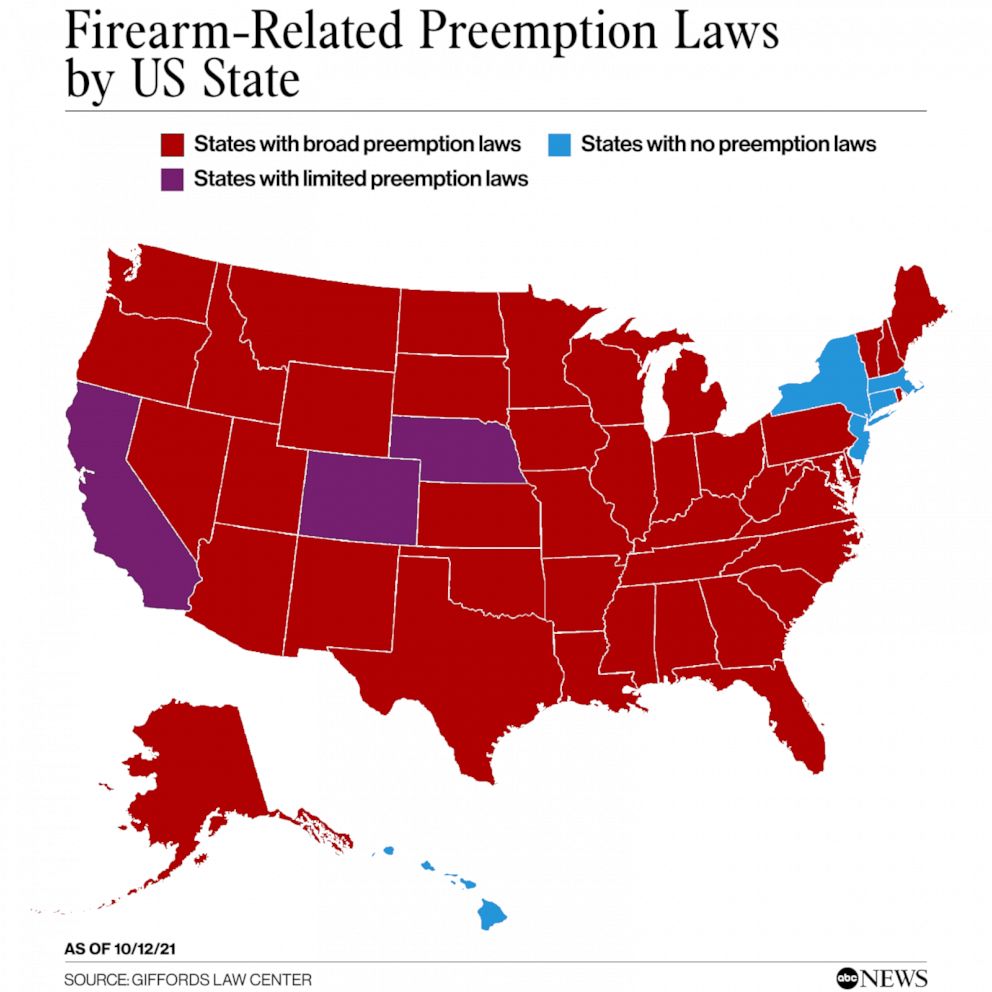

In fact, mass shootings tended to occur in states with stricter regulations. Of the states with the highest per capita rates of mass shootings, many – like Connecticut, Maryland and California – employ background checks and assault weapons bans.

By contrast, 18 states did not have a single mass shooting event over the entire 40-year period. Many of these states – like West Virginia, Wyoming and South Dakota – have high rates of gun ownership and relatively loose gun control laws.

But those data patterns don’t tell the full story of our analysis.

The effects of gun laws

Gun laws aren’t the only factors that affect where and when mass shootings occur. The number of police officers per capita, a community’s population density and crime rate, and other demographic characteristics such as unemployment rates and average income can also matter.

We used statistical methods to control for those factors, narrowing our analysis to find out whether various types of gun control laws affected the number of mass shootings or number of mass shooting deaths in each state each year.

Specifically, we examined the effects of four different types of gun control legislation: background checks; assault weapons bans; high-capacity magazine bans; and “ extreme risk protection order ” or “red flag laws” that let a court determine whether to confiscate the guns of someone deemed a threat to themselves or others.

We found that background check requirements, assault weapons bans and high-capacity magazine bans each reduce the number of mass shootings in the United States – but only by a small amount. For instance, enacting a statewide assault weapons ban decreases the number of mass shootings in the state by one shooting every six years. And none of the four types of gun control legislation correlate with fewer total mass shooting deaths.

And laws that remove an individual’s right to own firearms if that individual poses a risk to the community do not affect the number of mass shooting events.

Beyond gun control

Our analysis suggests that Americans who want to make mass shootings less frequent and less deadly may want to think beyond gun control legislation.

Statistically, mass shootings tend to occur in large, densely populated states with higher income and education levels per capita. While these states often respond to mass shootings by passing gun control legislation, it may be that alternative avenues are more successful.

For example, we find that increasing the number of police officers per capita decreases the number of mass shootings.

There is a wide variety of policy options designed to prevent mass shootings. The American Psychological Association suggests a comprehensive community approach that works to identify prevention strategies that bring public safety officials, schools, public health systems and faith-based groups together to reduce gun violence.

Aaron Stark , who says he was almost a mass shooter, explains that mass shootings can be an act of desperation resulting from frustration, stress and an individual’s perception that they lack power. This is in line with a new U.S. Secret Service report that suggests politicians may need to think beyond the accessibility of guns. Violence prevention strategies that focus on interpersonal and community relations may be more effective than gun control legislation.

Framing the debate

Many policy options involve value judgments stemming from beliefs about the U.S. Constitution and the power of government to regulate guns.

Among people who think that restricting gun access reduces mass shootings, people disagree over whether the country should prioritize the individual freedoms of gun owners or the safety and peace of mind of non-gun owners. These differing views can reflect different interpretations of the extent to which the Constitution protects the rights of individuals to keep and bear arms.

States have a role to play, too. Federal gun policy covers the entire nation. But our data indicates that attention to state and local factors can play an important role in preventing mass shootings.

In the end, gun control remains a debate about facts and context, complicated by a disagreement over constitutional values.

[ Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter .]

- Gun control

- Gun violence

- Mass shootings

- Second Amendment

- Gun policy US

- Gun research

Events Officer

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

- Our Supporters

One Reason For Persistent Speeding? Roads Whose Designs Seem To Invite It

Photos: Hanging 18 With A Woofing Waverider On Oahu’s North Shore

Ben Lowenthal: The Surprising Persistence Of Conservatism In True Blue Hawaii

Maui Budget Earmarks $2.6 Million For Lahaina Wastewater Permit

This State Agency Transformed Kakaako. Should It Do The Same For Lahaina?

- Special Projects

- Mobile Menu

In Gun Debate, Both Sides Have Evidence To Back Them Up

Gun control is back in the U.S. political debate, in the wake of mass shootings in California, Boulder and Atlanta.

Democrats see stricter gun control as a step toward addressing the problem. In March, as the House of Representatives passed two gun control bills, Speaker Nancy Pelosi claimed that the “ solutions will save lives .”

Many Republicans disagree, arguing as Sen. Ted Cruz has that proposed laws seeking to require background checks on all firearms sales and transfers and to ban assault weapons are “ ridiculous theater ” that fail to reduce mass shootings.

As two political scientists trained in data analysis , we set out to determine whether gun control legislation actually prevents mass shootings. We collected data on all mass shootings that occurred between February 1980 and February 2020. We then examined key information on the perpetrators, weapons used and laws in effect at the time of shooting.

Our research, which is yet to be published in an academic journal, suggests that there is statistical evidence to support both parties’ positions about gun control legislation.

While stricter gun control laws may make mass shootings slightly less common, our research suggests that the rhetoric of both parties may not tell the full story. Rather than federal gun control laws, policies that focus on violence prevention at the community or individual levels may be more effective at preventing mass shooting deaths.

Mass Shootings In The Past 40 years

We defined a mass shooting as a single incident in which a perpetrator with no connection to gang activity or organized crime shot and killed three or more people. This is similar to the definition Congress uses .

We found there were 112 of these events between 1980 and 2020; the number of mass shootings each year has increased over time. An overwhelming majority of mass shooters – 87% of them – obtained their firearms legally. Nearly all shooters – 93% – shot their victims in the same state where they obtained their weapons.

These facts suggest that existing gun laws and regulations governing gun purchases and firearms that cross state lines may not be working to reduce mass shootings. Our study did not address whether or how other forms of gun violence might be affected by those laws.

In fact, mass shootings tended to occur in states with stricter regulations. Of the states with the highest per capita rates of mass shootings, many – like Connecticut, Maryland and California – employ background checks and assault weapons bans.

By contrast, 18 states did not have a single mass shooting event over the entire 40-year period. Many of these states – like West Virginia, Wyoming and South Dakota – have high rates of gun ownership and relatively loose gun control laws.

But those data patterns don’t tell the full story of our analysis.

The Effects Of Gun Laws

Gun laws aren’t the only factors that affect where and when mass shootings occur. The number of police officers per capita, a community’s population density and crime rate, and other demographic characteristics such as unemployment rates and average income can also matter.

We used statistical methods to control for those factors, narrowing our analysis to find out whether various types of gun control laws affected the number of mass shootings or number of mass shooting deaths in each state each year.

Specifically, we examined the effects of four different types of gun control legislation: background checks; assault weapons bans; high-capacity magazine bans; and “ extreme risk protection order ” or “red flag laws” that let a court determine whether to confiscate the guns of someone deemed a threat to themselves or others.

We found that background check requirements, assault weapons bans and high-capacity magazine bans each reduce the number of mass shootings in the United States – but only by a small amount. For instance, enacting a statewide assault weapons ban decreases the number of mass shootings in the state by one shooting every six years. And none of the four types of gun control legislation correlate with fewer total mass shooting deaths.

And laws that remove an individual’s right to own firearms if that individual poses a risk to the community do not affect the number of mass shooting events.

Beyond Gun Control

Our analysis suggests that Americans who want to make mass shootings less frequent and less deadly may want to think beyond gun control legislation.

Statistically, mass shootings tend to occur in large, densely populated states with higher income and education levels per capita. While these states often respond to mass shootings by passing gun control legislation, it may be that alternative avenues are more successful.

For example, we find that increasing the number of police officers per capita decreases the number of mass shootings.

There is a wide variety of policy options designed to prevent mass shootings. The American Psychological Association suggests a comprehensive community approach that works to identify prevention strategies that bring public safety officials, schools, public health systems and faith-based groups together to reduce gun violence.

Increasing the number of police officers per capita decreases the number of mass shootings.

Aaron Stark , who says he was almost a mass shooter, explains that mass shootings can be an act of desperation resulting from frustration, stress and an individual’s perception that they lack power. This is in line with a new U.S. Secret Service report that suggests politicians may need to think beyond the accessibility of guns. Violence prevention strategies that focus on interpersonal and community relations may be more effective than gun control legislation.

Framing The Debate

Many policy options involve value judgments stemming from beliefs about the U.S. Constitution and the power of government to regulate guns.

Among people who think that restricting gun access reduces mass shootings, people disagree over whether the country should prioritize the individual freedoms of gun owners or the safety and peace of mind of non-gun owners. These differing views can reflect different interpretations of the extent to which the Constitution protects the rights of individuals to keep and bear arms.

States have a role to play, too. Federal gun policy covers the entire nation. But our data indicates that attention to state and local factors can play an important role in preventing mass shootings.

In the end, gun control remains a debate about facts and context, complicated by a disagreement over constitutional values.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

--> Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed. --> Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

Before you go.

Civil Beat is a small nonprofit newsroom that provides free content with no paywall. That means readership growth alone can’t sustain our journalism.

The truth is that less than 1% of our monthly readers are financial supporters. To remain a viable business model for local news, we need a higher percentage of readers-turned-donors.

Will you consider becoming a new donor today?

About the Authors

- Jennifer Selin Jennifer Selin is the Kinder Institute Assistant Professor of Constitutional Democracy, University of Missouri-Columbia Use the RSS feed to subscribe to Jennifer Selin's posts today

Top Stories

UH Regents Are Stepping Up The Search For A New President

Your Electric Bill Could Be Going Up To Help Pay For Wildfire Prevention Measures

Naka Nathaniel: Are We Coming To The End Of A Cycle Of Accountability In Hawaii?

The Sunshine Blog: The Pot Bill Goes Up In Smoke And Other Tales Of Political Woe

Hawaii’s Deaf Community Is Struggling With Lack Of Certified ASL Interpreters

Get in-depth reporting on hawaii’s biggest issues, sign up for our free morning newsletter.

You're officially signed up for our daily newsletter, the Morning Beat. A confirmation email will arrive shortly.

In the meantime, we have other newsletters that you might enjoy. Check the boxes for emails you'd like to receive.

- Breaking News Alerts What's this? Be the first to hear about important news stories with these occasional emails.

- Special Projects & Investigations What's this? You'll hear from us whenever Civil Beat publishes a major project or investigation.

- Environment What's this? Get our latest environmental news on a monthly basis, including updates on Nathan Eagle's 'Hawaii 2040' series.

- Ideas What's this? Get occasional emails highlighting essays, analysis and opinion from IDEAS, Civil Beat's commentary section.

Inbox overcrowded? Don't worry, you can unsubscribe or update your preferences at any time.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Consider This from NPR

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

As Lawmakers Debate Gun Control, What Policies Could Actually Help?

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) speaks during a rally against gun violence outside the U.S. Capitol on June 6, 2022 in Washington, DC. Drew Angerer/Getty Images hide caption

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) speaks during a rally against gun violence outside the U.S. Capitol on June 6, 2022 in Washington, DC.

President Biden urged Congress to act and the House is preparing to pass multiple gun control measures. But the Senate is where a compromise must be made. A bipartisan group of lawmakers is reportedly discussing policies like enhanced background checks and a federal red flag law. While it's unclear what Congress might agree to, researchers do have ideas about what policies could help prevent mass shootings and gun violence. NPR's Nell Greenfieldboyce explains. Hear more from her reporting on Short Wave , NPR's daily science podcast, via Apple , Google , or Spotify . NPR's Cory Turner reports on what school safety experts think can be done to prevent mass shootings, and former FBI agent Katherine Schweit describes where Uvalde police may have erred their active shooter response. Schweit is the author of Stop the Killing: How to End the Mass Shooting Crisis . Help NPR improve podcasts by completing a short, anonymous survey at npr.org/podcastsurvey . In participating regions, you'll also hear a local news segment to help you make sense of what's going on in your community. Email us at [email protected] .

This episode was produced by Brent Baughman, Ayen Bior, and Michael Levitt. It was edited by Patrick Jarenwattananon, Nicole Cohen, Will Stone, Courtney Dorning, and Connor Donevan. Our executive producer is Cara Tallo.

The Reflector News

Featured stories, pros and cons of gun control in the united states, pro by lindsey wormuth | distribution manager.

Stricter gun control can sometimes seem like a never-ending argument against the Second Amendment and about whether gun laws can really keep people safe. The Second Amendment states that because a well-regulated militia is necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed upon. I never thought gun laws were too weak until I was in a situation involving a minor who had access to guns.

In May of 2018, I was at Noblesville High School the day that a school shooting took place at Noblesville West Middle School, nearly eight minutes away. I remember being told to barricade the door and windows and take cover in a corner. Although the shooting was not at my high school, not knowing what was going on and whether there also would be an active shooter at the high school was terrifying. The middle school shooter was a 13-year-old boy who injured a teacher and a student. According to The Washington Post , there were 90 school shootings nationwide in the two years of 2020-2022. Parents should be able to send their children to school and not worry about their children having to barricade themselves because their school has an active shooter.

“When the Post analyzed these [school] shootings, it found that more than two-thirds were committed by shooters under the age of 18,” according to the Austin American-Statesman . “The analysis found that the median age for school shooters was 16.” To gain more control over who has access to guns, they need to be less accessible to teenagers.

Besides school shootings, a gunman at the Greenwood Park Mall on July 17 “fired shots inside the food court . . . killing three people,” according to WTHR. The gunman was 20 years old, another young shooter.

Gun safety will always be an issue in the United States. To reduce shootings and gun-related suicides, we need to raise the minimum age to purchase guns, ban assault weapons, and require a permit in all states to carry a handgun. Despite the ongoing arguments, gun control legislation must be passed. People are suffering mass tragedies as a result of legislators’ inaction. According to the Indiana Government website , as of July 1, 2022 the State of Indiana will no longer require a handgun permit to legally carry, conceal or transport a handgun within the state. A common misconception about the law is that it allows anyone to be able to carry a handgun. There are still standards you have to meet to be able to legally carry. For example, anyone who was convicted of domestic violence or battery charges, was imprisoned for a federal offense “exceeding one year” or anyone under the age of 18 will not be able to legally carry a gun in Indiana, according to the Indiana Government website.

According to the National Rifle Association , “Even if criminals did submit to background checks, we’ve seen that these checks aren’t effective at stopping those who intend to use guns to commit crimes.” The NRA-ILA has created scenarios showing how background checks can be ineffective. One NRA-ILA scenario says this: “A drug addict lies about their addiction on a federal background check form. Although this individual is committing a federal crime, a background check most likely won’t stop them.” Another NRA-ILA scenario says this: “A person with no criminal history walks into a store to buy a gun they’ll use to commit a crime. A background check most likely won’t stop them.”Ultimately, there is no guaranteed way to identify whether someone who is purchasing a gun will commit a crime, but minimizing the people who can access guns can. Increasing the amount of steps with a background check could help eliminate the people who buy them to commit crimes. People should be able to go to school, the mall, or a club without the fear or threat of a shooting. The only way to reduce shootings is to change the laws.

Con by Olivia Pastrick | Staff Writer

Many proponents of an increase in gun control in the United States do not take into consideration the ineffectiveness of the current laws in place regarding citizens’ rights to bear arms. For example, the Gun Control Act of 1968 prohibits holders of Federal Firearms Licenses from transferring licenses to certain groups of people classified as irresponsible or potentially dangerous, according to the U.S. Department of Justice . However, this small form of gun control is clearly not doing its supposed job to stop or limit gun violence in the United States, as indicated by the 110 homicides in Indianapolis alone this year as of June 30, according to Fox59 . The question is still whether federally imposed gun control laws can be effective in reducing gun violence in the United States.

For starters, the root of the problem is not guns, it is people. Criminals with the intent to kill people would not likely be swayed from committing crime by additional laws when they are already breaking other laws. According to the National Rifle Association’s Institute for Legislative Action , 43.2% of prisoners in state or federal prison got their guns “off the street or on the underground market,” which would not be affected by additional gun control laws. Similar logic can be applied in examining the effectiveness of background checks for people who purchase firearms with the intent to harm others. These individuals already intend to break the law, so they would not likely be deterred by having to lie on a government form to pass a background check to obtain a gun.

Similarly, homicide rates in countries where guns are banned have not gone down. According to the California Rifle and Pistol Association , the United Kingdom’s homicide rate in 1996, before handguns were banned, was 1.12 per 100,000 people. In 1997, the year handguns were banned, it rose to 1.24, and in 2002 it peaked at 2.1 homicides per 100,000 people.

There have been times when, in U.S. cities, bans have been placed on the purchase and possession of guns. For example, the city of Chicago enacted a handgun ban in 1982 that prohibited residents from owning handguns for their own use even in their homes and required existing gun owners to re-register their weapons every year, according to ABC7 . This law made Chicago the city with the strictest gun laws in the country at that time, yet it did not curb murders in the city. According to the Chicago Tribune , in the decade after it banned handguns, murders jumped by 41 percent, compared with an 18 percent increase throughout the country. Again, this ban did not deter criminals with the intent to cause harm from obtaining firearms. The law was effectively made unenforceable by a 2010 Supreme Court decision that the Second Amendment protection of the individual’s right to possess firearms applies to cities and states, according to ABC7.

Additionally, there have been situations in the United States in which citizens armed with guns have helped take down people trying to inflict harm. For example, the Greenwood Park Mall shooting on July 17 was stopped within 15 seconds after it began by a citizen with a gun, according to WTHR . A ban on guns, or even stricter gun control laws, might have prevented the bystander from carrying a gun in the mall; and the shooting could have been much worse. Finally, with distrust in the government so high in the United States, pro-gun citizens consider their guns a level of protection against tyrannical government practices, according to NPR . People fighting for their right to bear arms also worry that if the government infringes upon the Second Amendment, nothing will stop the government from changing or taking away other rights that are seen as cornerstones of American life.

Recommended for You

Indianapolis Potholes

Why We Should Not Observe Presidents Day

Daylight Saving Time Should Stay for Good

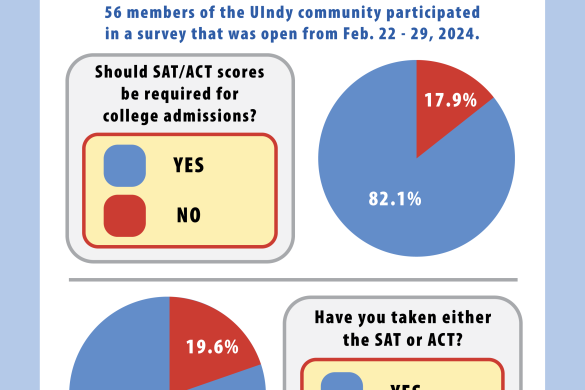

Requiring Standardized Tests Should be a Thing of the Past

‘BookTok’ Thrives on Marketability Rather than Artistic Integrity

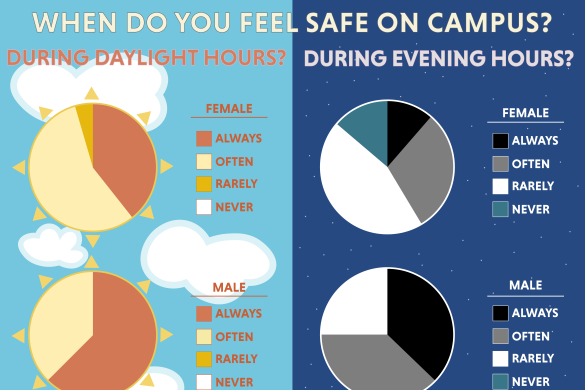

Let’s Change the Campus Security Narrative

I Am Tired of Being a Hoosier in the Current Political Climate

Stop Bullying Taylor Swift for Supporting Her Boyfriend

Advertisement

General Info

- Advertising

- Print Editions

- Reflector Archives

- Accessibility Statement

Subscribe to The Reflector’s email newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest campus news.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 10 December 2019

The psychology of guns: risk, fear, and motivated reasoning

- Joseph M. Pierre 1

Palgrave Communications volume 5 , Article number: 159 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

250k Accesses

25 Citations

412 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Politics and international relations

- Social policy

The gun debate in America is often framed as a stand-off between two immutable positions with little potential to move ahead with meaningful legislative reform. Attempts to resolve this impasse have been thwarted by thinking about gun ownership attitudes as based on rational choice economics instead of considering the broader socio-cultural meanings of guns. In this essay, an additional psychological perspective is offered that highlights how concerns about victimization and mass shootings within a shared culture of fear can drive cognitive bias and motivated reasoning on both sides of the gun debate. Despite common fears, differences in attitudes and feelings about guns themselves manifest in variable degrees of support for or opposition to gun control legislation that are often exaggerated within caricatured depictions of polarization. A psychological perspective suggests that consensus on gun legislation reform can be achieved through understanding differences and diversity on both sides of the debate, working within a common middle ground, and more research to resolve ambiguities about how best to minimize fear while maximizing personal and public safety.

Discounting risk

Do guns kill people or do people kill people? Answers to that riddle draw a bright line between two sides of a caricatured debate about guns in polarized America. One side believes that guns are a menace to public safety, while the other believes that they are an essential tool of self-preservation. One side cannot fathom why more gun control legislation has not been passed in the wake of a disturbing rise in mass shootings in the US and eyes Australia’s 1996 sweeping gun reform and New Zealand’s more recent restrictions with envy. The other, backed by the Constitutional right to bear arms and the powerful lobby of the National Rifle Association (NRA), fears the slippery slope of legislative change and refuses to yield an inch while threatening, “I’ll give you my gun when you pry it from my cold, dead hands”. With the nation at an impasse, meaningful federal gun legislation aimed at reducing firearm violence remains elusive.

Despite the 1996 Dickey Amendment’s restriction of federal funding for research on gun violence by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Rostron, 2018 ), more than 30 years of public health research supports thinking of guns as statistically more of a personal hazard than a benefit. Case-control studies have repeatedly found that gun ownership is associated with an increased risk of gun-related homicide or suicide occurring in the home (Kellermann and Reay, 1986 ; Kellermann et al., 1993 ; Cummings and Koepsell, 1998 ; Wiebe, 2003 ; Dahlberg et al., 2004 ; Hemenway, 2011 ; Anglemeyer et al., 2014 ). For homicides, the association is largely driven by gun-related violence committed by family members and other acquaintances, not strangers (Kellermann et al., 1993 , 1998 ; Wiebe, 2003 ).

If having a gun increases the risk of gun-related violent death in the home, why do people choose to own guns? To date, the prevailing answer from the public health literature has been seemingly based on a knowledge deficit model that assumes that gun owners are unaware of risks and that repeated warnings about “overwhelming evidence” of “the health risk of a gun in the home [being] greater than the benefit” (Hemenway, 2011 ) should therefore decrease gun ownership and increase support for gun legislation reform. And yet, the rate of US households with guns has held steady for two decades (Smith and Son, 2015 ) with owners amassing an increasing number of guns such that the total civilian stock has risen to some 265 million firearms (Azrael et al., 2017 ). This disparity suggests that the knowledge deficit model is inadequate to explain or modify gun ownership.

In contrast to the premise that people weigh the risks and benefits of their behavior based on “rational choice economics” (Kahan and Braman, 2003 ), nearly 50 years of psychology and behavioral economics research has instead painted a picture of human decision-making as a less than rational process based on cognitive short-cuts (“availability heuristics”) and other error-prone cognitive biases (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974 ; Kunda, 1990 ; Haselton and Nettle, 2006 ; Hibert, 2012 ). As a result, “consequentialist” approaches to promoting healthier choices are often ineffective. Following this perspective, recent public health efforts have moved beyond educational campaigns to apply an understanding of the psychology of risky behavior to strike a balance between regulation and behavioral “nudges” aimed at reducing harmful practices like smoking, unhealthy eating, texting while driving, and vaccine refusal (Atchley et al., 2011 ; Hansen et al., 2016 ; Matjasko et al., 2016 ; Pluviano et al., 2017 ).

A similar public health approach aimed at reducing gun violence should take into account how gun owners discount the risks of ownership according to cognitive biases and motivated reasoning. For example, cognitive dissonance may lead those who already own guns to turn a blind eye to research findings about the dangers of ownership. Optimism bias, the general tendency of individuals to overestimate good outcomes and underestimate bad outcomes, can likewise make it easy to disregard dangers by externalizing them to others. The risk of suicide can therefore be dismissed out of hand based on the rationale that “it will never happen to me,” while the risk of homicide can be discounted based on demographic factors. Kleck and Gertz ( 1998 ) noted that membership in street gangs and drug dealing might be important confounds of risk in case control studies, just as unsafe storage practices such as keeping a firearm loaded and unlocked may be another (Kellerman et al., 1993 ). Other studies have found that the homicide risk associated with guns in the home is greater for women compared to men and for non-whites compared to whites (Wiebe, 2003 ). Consequently, white men—by far the largest demographic that owns guns—might be especially likely to think of themselves as immune to the risks of gun ownership and, through confirmation bias, cherry-pick the data to support pre-existing intuitions and fuel motivated disbelief about guns. These testable hypotheses warrant examination in future research aimed at understanding the psychology of gun ownership and crafting public health approaches to curbing gun violence.

Still, while the role of cognitive biases should be integrated into a psychological understanding of attitudes towards gun ownership, cognitive biases are universal liabilities that fall short of explaining why some people might “employ” them as a part of motivated reasoning to support ownership or to oppose gun reform. To understand the underlying motivation that drives cognitive bias, a deeper analysis of why people own guns is required. In the introductory essay to this journal’s series on “What Guns Mean,” Metzl ( 2019 ) noted that public health efforts to reduce firearm ownership have failed to “address beliefs about guns among people who own them”. In a follow-up piece, Galea and Abdalla ( 2019 ) likewise suggested that the gun debate is complicated by the fact that “knowledge and values do not align” and that “these values create an impasse, one where knowing is not enough” (Galea and Abdalla, 2019 ). Indeed, these and other authors (Kahan and Braman, 2003 ; Braman and Kahan, 2006 ; Pierre, 2015 ; Kalesan et al., 2016 ) have enumerated myriad beliefs and values, related to the different “symbolic lives” and “social meanings” of firearms both within and outside of “gun culture” that drive polarized attitudes towards gun ownership in the US. This essay attempts to further explore the meaning of guns from a psychological perspective.

Fear and gun ownership

Modern psychological understanding of human decision-making has moved beyond availability heuristics and cognitive biases to integrate the role of emotion and affect. Several related models including the “risk-as-feelings hypothesis” (Loewenstein et al., 2001 ), the “affect heuristic” (Slovic et al., 2007 ); and the “appraisal-tendency framework” (Lerner et al., 2015 ) illustrate how emotions can hijack rational-decision-making processes to the point of being the dominant influence on risk assessments. Research has shown that “perceived risk judgments”—estimates of the likelihood that something bad will happen—are especially hampered by emotion (Pachur et al., 2012 ) and that different types of affect can bias such judgments in different ways (Lerner et al., 2015 ). For example, fear can in particular bias assessments away from rational analysis to overestimate risks, as well as to perceive negative events as unpredictable (Lerner et al., 2015 ).

Although gun ownership is associated with positive feelings about firearms within “gun culture” (Pierre, 2015 ; Kalesan et al., 2016 ; Metzl, 2019 ), most research comparing gun owners to non-gun owners suggests that ownership is rooted in fear. While long guns have historically been owned primarily for hunting and other recreational purposes, US surveys dating back to the 1990s have revealed that the most frequent reason for gun ownership and more specifically handgun ownership is self-protection (Cook and Ludwig, 1997 ; Azrael et al., 2017 ; Pew Research Center, 2017 ). Research has likewise shown that the decision to obtain a firearm is largely motivated by past victimization and/or fears of future victimization (Kleck et al., 2011 ; Hauser and Kleck, 2013 ).

A few studies have reported that handgun ownership is associated with past victimization, perceived risk of crime, and perceived ineffectiveness of police protection within low-income communities where these concerns may be congruent with real risks (Vacha and McLaughlin, 2000 , 2004 ). However, gun ownership tends to be lower in urban settings and in low-income families where there might be higher rates of violence and crime (Vacha and McLaughlin, 2000 ). Instead, the largest demographic of gun owners in the US are white men living in rural communities who are earning more than $100K/year (Azrael et al., 2017 ). Mencken and Froese ( 2019 ) likewise reported that gun owners tend to have higher incomes and greater ratings of life happiness than non-owners. These findings suggest a mismatch between subjective fear and objective reality.

Stroebe and colleagues ( 2017 ) reported that the specific perceived risk of victimization and more “diffuse” fears that the world is a dangerous place are both independent predictors of handgun ownership, with perceived risk of assault associated with having been or knowing a victim of violent crime and belief in a dangerous world associated with political conservatism. These findings hint at the likelihood that perceived risk of victimization can be based on vicarious sources with a potential for bias, whether through actual known acquaintances or watching the nightly news, conducting a Google search or scanning one’s social media feed, or reading “The Armed Citizen” column in the NRA newsletter The American Rifleman . It also suggests that a general fear of crime, independent of actual or even perceived individual risk, may be a powerful motivator for gun ownership for some that might track with race and political ideology.

Several authors have drawn a connection between gun ownership and racial tensions by examining the cultural symbolism and socio-political meaning of guns. Bhatia ( 2019 ) detailed how the NRA’s “disinformation campaign reliant on fearmongering” is constructed around a narrative of “fear and identity politics” that exploits current xenophobic sentiments related to immigrants. Metzl ( 2019 ) noted that during the 1960s, conservatives were uncharacteristically in favor of gun control when armed resistance was promoted by Malcolm X, the Black Panther Party, and others involved in the Black Power Movement. Today, Metzl argues, “mainstream society reflexively codes white men carrying weapons in public as patriots, while marking armed black men as threats or criminals.” In support of this view, a 2013 study found that having a gun in the home was significantly associated with racism against black people as measured by the Symbolic Racism Scale, noting that “for each 1 point increase in symbolic racism, there was a 50% greater odds of having a gun in the home and a 28% increase in the odds of supporting permits to carry concealed handguns” (O’Brien et al., 2013 ). Hypothesizing that guns are a symbol of hegemonic masculinity that serves to “shore up white male privilege in society,” Stroud ( 2012 ) interviewed a non-random sample of 20 predominantly white men in Texas who had licenses for concealed handgun carry. The men described how guns help to fulfill their identities as protectors of their families, while characterizing imagined dangers with rhetoric suggesting specific fears about black criminals. These findings suggest that gun ownership among white men may be related to a collective identity as “good guys” protecting themselves against “bad guys” who are people of color, a premise echoed in the lay press with headlines like, “Why Are White Men Stockpiling Guns?” (Smith, 2018 ), “Report: White Men Stockpile Guns Because They’re Afraid of Black People” (Harriott, 2018 ), and “Gun Rights Are About Keeping White Men on Top” (Wuertenberg, 2018 ).

Connecting the dots, the available evidence therefore suggests that for many gun owners, fears about victimization can result in confirmation, myside, and optimism biases that not only discount the risks of ownership, but also elevate the salience of perceived benefit, however remote, as it does when one buys a lottery ticket (Rogers and Webley, 2001 ). Indeed, among gun owners there is widespread belief that having a gun makes one safer, supported by published claims that where there are “more guns”, there is “less crime” (Lott, 1998 , 1999 ) as well as statistics and anecdotes about successful defensive gun use (DGU) (Kleck and Gertz, 1995 , 1998 ; Tark and Kleck, 2004 ; Cramer and Burnett, 2012 ). Suffice it to say that there have been numerous debates about how to best interpret this body of evidence, with critics claiming that “more guns, less crime” is a myth (Ayres and Donohue, 2003 ; Moyer, 2017 ) that has been “discredited” (Wintemute, 2008 ) and that the incidence of DGU has been grossly overestimated and pales in comparison to the risk of being threatened or harmed by a gun in the home (Hemenway, 1997 , 2011 ; Cook and Ludwig, 1998 ; Azrael and Hemenway, 2000 ; Hemenway et al., 2000 ). Attempts at objective analysis have concluded that surveys to date have defined and measured DGU inconsistently with unclear numbers of false positives and false negatives (Smith, 1997 ; McDowall et al., 2000 ; National Research Council, 2005 ; RAND, 2018 ), that the causal effects of DGU on reducing injury are “inconclusive” (RAND, 2018 ), and that “neither side seems to be willing to give ground or see their opponent’s point of view” (Smith, 1997 ). With the scientific debate about DGU mirrored in the lay press (Defilippis and Hughes, 2015 ; Kleck, 2015 ; Doherty, 2015 ), a rational assessment of whether guns make owners safer is hampered by a lack of “settled science”. With no apparent consensus, motivated reasoning can pave the way to the nullification of opposing arguments in favor of personal opinions and ideological stances.

For gun owners, even if it is acknowledged that on average successful DGU is much less likely than a homicide or suicide in the home, not having a gun at all translates to zero chance of self-preservation, which are intolerable odds. The bottom line is that when gun owners believe that owning a gun will make them feel safer, little else may matter. Curiously however, there is conflicting evidence that gun ownership actually decreases fears of victimization (Hauser and Kleck, 2013 ; Dowd-Arrow et al., 2019 ). That gun ownership may not mitigate such fears could help to account for why some individuals go on to acquire multiple guns beyond their initial purchase with US gun owners possessing an average of 5 firearms and 8% of owners having 10 or more (Azrael et al., 2017 ).

Gun owner diversity

A psychological model of the polarized gun debate in America would ideally compare those for or against gun control legislation. However, research to date has instead focused mainly on differences between gun owners and non-gun owners, which has several limitations. For example, of the nearly 70% of Americans who do not own a gun, 36% report that they can see themselves owning one in the future (Pew Research Center, 2017 ) with 11.5% of all gun owners in 2015 having newly acquired one in the previous 5 years (Wertz et al., 2018 ). Gun ownership and non-ownership are therefore dynamic states that may not reflect static ideology. Personal accounts such as Willis’ ( 2010 ) article, “I Was Anti-gun, Until I Got Stalked,” illustrate this point well.

With existing research heavily reliant on comparing gun owners to non-gun owners, a psychological model of gun attitudes in the US will have limited utility if it relies solely on gun owner stereotypes based on their most frequent demographic characteristics. On the contrary, Hauser and Kleck ( 2013 ) have argued that “a more complete understanding of the relationship between fear of crime and gun ownership at the individual level is crucial”. Just so, looking more closely at the diversity of gun owners can reveal important details beyond the kinds of stereotypes that are often used to frame political debates.

Foremost, it must be recognized that not all gun owners are conservative white men with racist attitudes. Over the past several decades, women have comprised 9–14% of US gun owners with the “gender gap” narrowing due to decreasing male ownership (Smith and Son, 2015 ). A 2017 Pew Survey reported that 22% of women in the US own a gun and that female gun owners are just as likely as men to belong to the NRA (Pew Research Center, 2017 ). Although the 36% rate of gun ownership among US whites is the highest for any racial demographic, 25% of blacks and 15% of Hispanics report owning guns with these racial groups being significantly more concerned than whites about gun violence in their communities and the US as a whole (Pew Research Center, 2017 ). Providing a striking counterpoint to Stroud’s ( 2012 ) interviews of white gun owners in Texas, Craven ( 2017 ) interviewed 11 black gun owners across the country who offered diverse views on guns and the question of whether owning them makes them feel safer, including if confronted by police during a traffic stop. Kelly ( 2019 ) has similarly offered a self-portrait as a female “left-wing anarchist” against the stereotype of guns owners as “Republicans, racist libertarians, and other generally Constitution-obsessed weirdos”. She reminds us that, “there is also a long history of armed community self-defense among the radical left that is often glossed over or forgotten entirely in favor of the Fox News-friendly narrative that all liberals hate guns… when the cops and other fascists see that they’re not the only ones packing, the balance of power shifts, and they tend to reconsider their tactics”.

Although Mencken and Froese ( 2019 ) concluded that “white men in economic distress find comfort in guns as a means to reestablish a sense of individual power and moral certitude,” their study results actually demonstrated that gun owners fall into distinguishable groups based on different levels of “moral and emotional empowerment” imparted by guns. For example, those with low levels of gun empowerment were more likely to be female and to own long guns for recreational purposes such as hunting and collecting. Other research has shown that the motivations to own a gun, and the degree to which gun ownership is related to fear and the desire for self-protection, also varies according to the type of gun (Stroebe et al., 2017 ). Owning guns, owning specific types of guns (e.g. handguns, long guns, and so-called “military style” semi-automatic rifles like AR-15s), carrying a gun in public, and keeping a loaded gun on one’s nightstand all have different psychological implications. A 2015 study reported that new gun owners were younger and more likely to identify as liberal than long-standing gun owners (Wertz et al., 2018 ). Although Kalesan et al. ( 2016 ) found that gun ownership is more likely among those living within a “gun culture” where ownership is prevalent, encouraged, and part of social life, it would therefore be a mistake to characterize gun culture as a monolith.

It would also be a mistake to equate gun ownership with opposition to gun legislation reform or vice-versa. Although some evidence supports a strong association (Wolpert and Gimpel, 1998 ), more recent studies suggest important exceptions to the rule. While only about 30% of the US population owns a gun, over 70% believes that most citizens should be able to legally own them (Pew Research Center, 2017 ). Women tend to be more likely than men to support gun control, even when they are gun owners themselves (Kahan and Braman, 2003 ; Mencken and Froese, 2019 ). Older (age 70–79) Americans likewise have some of the highest rates of gun ownership, but also the highest rates of support for gun control (Pederson et al., 2015 ). In Mencken and Froese’s study ( 2019 ), most gun owners reporting lower levels of gun empowerment favored bans on semi-automatic weapons and high-capacity magazines and opposed arming teachers in schools. Kahan and Braman ( 2003 ) theorized that attitudes towards gun control are best understood according to a “cultural theory of risk”. In their study sample, those with “hierarchical” and “individualist” cultural orientations were more likely than those with “egalitarian” views to oppose gun control and these perspectives were more predictive than other variables including political affiliation and fear of crime.

In fact, both gun owners and non-owners report high degrees of support for universal background checks; laws mandating safe gun storage in households with children; and “red flag” laws restricting access to firearms for those hospitalized for mental illness or those otherwise at risk of harming themselves or others, those convicted of certain crimes including public display of a gun in a threatening manner, those subject to temporary domestic violence restraining orders, and those on “no-fly” or other watch lists (Pew Research Center, 2017 ; Barry et al., 2018 ). According to a 2015 survey, the majority of the US public also opposes carrying firearms in public spaces with most gun owners opposing public carry in schools, college campuses, places of worship, bars, and sports stadiums (Wolfson et al., 2017 ). Despite broad public support for gun legislation reform however, it is important to recognize that the threat of gun restrictions is an important driver of gun acquisition (Wallace, 2015 ; Aisch and Keller, 2016 ). As a result, proposals to restrict gun ownership boosted gun sales considerably under the Obama administration (Depetris-Chauvin, 2015 ), whereas gun companies like Remington and United Sporting Companies have since filed for bankruptcy under the Trump administration.

A shared culture of fear

Developing a psychological understanding of attitudes towards guns and gun control legislation in the US that accounts for underlying emotions, motivated reasoning, and individual variation must avoid the easy trap of pathologizing gun owners and dismissing their fears as irrational. Instead, it should consider the likelihood that motivated reasoning underlies opinion on both sides of the gun debate, with good reason to conclude that fear is a prominent source of both “pro-gun” and “anti-gun” attitudes. Although the research on fear and gun ownership summarized above implies that non-gun owners are unconcerned about victimization, a closer look at individual study data reveals both small between-group differences and significant within-group heterogeneity. For example, Stroebe et al.’s ( 2017 ) findings that gun owners had greater mean ratings of belief in a dangerous world, perceived risk of victimization, and the perceived effectiveness of owning a gun for self-defense were based on inter-group differences of <1 point on a 7-point Likert scale. Fear of victimization is therefore a universal fear for gun owners and non-gun owners alike, with important differences in both quantitative and qualitative aspects of those fears. Kahan and Braham ( 2003 ) noted that the gun debate is not so much a debate about the personal risks of gun ownership, as it is a one about which of two potential fears is most salient—that of “firearm casualties in a world with insufficient gun control or that of personal defenselessness in a world with excessive control”.

Although this “shared fear” hypothesis has not been thoroughly tested in existing research, there is general support for it based on evidence that fear is an especially potent influence on risk assessment and decision-making when considering low-frequency catastrophic events (Chanel et al., 2009 ). In addition, biased risk assessments have been linked to individual feelings about a specific activity. Whereas many activities in the real world have both high risk and high benefit, positive attitudes about an activity are associated with biased judgments of low risk and high benefit while negative attitudes are associated with biased judgments of high risk and low benefit (Slovic et al., 2007 ). These findings match those of the gun debate, whereby catastrophic events like mass shootings can result in “probability neglect,” over-estimating the likelihood of risk (Sunstein, 2003 ; Sunstein and Zeckhauser, 2011 ) with polarized differences regarding guns as a root cause and gun control as a viable solution. For those that have positive feelings about guns and their perceived benefit, the risk of gun ownership is minimized as discussed above. However, based on findings from psychological research on fear (Loewenstein et al., 2001 ; Slovic et al., 2007 ), the reverse is also likely to be true—those with negative feelings about guns who perceive little benefit to ownership may tend to over-estimate risks. Consistent with this dichotomy, both calls for legislative gun reform, as well as gun purchases increase in the wake of mass shootings (Wallace, 2015 ; Wozniak, 2017 ), with differences primarily predicted by the relative self-serving attributional biases of gun ownership and non-ownership alike (Joslyn and Haider-Markel, 2017 ).

Psychological research has shown that fear is associated with loss of control, with risks that are unfamiliar and uncontrollable perceived as disproportionately dangerous (Lerner et al., 2015 ; Sunstein, 2003 ). Although mass shootings have increased in recent years, they remain extremely rare events and represent a miniscule proportion of overall gun violence. And yet, as acts of terrorism, they occur in places like schools that are otherwise thought of as a suburban “safe spaces,” unlike inner cities where violence is more mundane, and are often given sensationalist coverage in the media. A 2019 Harris Poll found that 79% of Americans endorse stress as a result of the possibility of a mass shooting, with about a third reporting that they “cannot go anywhere without worrying about being a victim” (American Psychological Association, 2019 ). While some evidence suggests that gun owners may be more concerned about mass shootings than non-gun owners (Dowd-Arrow et al., 2019 ), this is again a quantitative difference as with fear of victimization more generally. There is little doubt that parental fears about children being victims of gun violence were particularly heightened in the wake of Columbine (Altheide, 2019 ) and it is likely that subsequent school shootings at Virginia Tech, Sandy Hook Elementary, and Stoneman Douglas High have been especially impactful in the minds of those calling for increasing restrictions on gun ownership. For those privileged to be accustomed to community safety who are less worried about home invasion and have faith in the police to provide protection, fantasizing about “gun free zones” may reflect a desire to recreate safe spaces in the wake of mass shootings that invoke feelings of loss of control.

Altheide ( 2019 ) has argued that mass shootings in the US post-Columbine have been embedding within a larger cultural narrative of terrorism, with “expanded social control and policies that helped legitimate the war on terror”. Sunstein and Zeckhauser ( 2011 ) have similarly noted that following terrorist attacks, the public tends to demand responses from government, favoring precautionary measures that are “not justified by any plausible analysis of expected utility” and over-estimating potential benefits. However, such responses may not only be ineffective, but potentially damaging. For example, although collective anxieties in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks resulted in the rapid implementation of new screening procedures for boarding airplanes, it has been argued that the “theater” of response may have done well to decrease fear without any evidence of actual effectiveness in reducing danger (Graham, 2019 ) while perhaps even increasing overall mortality by avoiding air travel in favor of driving (Sunstein, 2003 ; Sunstein and Zeckhauser, 2011 ).

As with the literature on DGU, the available evidence supporting the effectiveness of specific gun laws in reducing gun violence is less than definitive (Koper et al., 2004 ; Hahn et al., 2005 ; Lee et al., 2017 ; Webster and Wintemute, 2015 ), leaving the utility of gun reform legislation open to debate and motivated reasoning. Several authors have argued that even if proposed gun control measures are unlikely to deter mass shooters, “doing something is better than nothing” (Fox and DeLateur, 2014 ) and that ineffective counter-terrorism responses are worthwhile if they reduce public fear (Sunstein and Zeckhauser, 2011 ). Crucially however, this perspective fails to consider the impact of gun control legislation on the fears of those who value guns for self-protection. For them, removing guns from law-abiding “good guys” while doing nothing to deter access to the “bad guys” who commit crimes is illogical anathema. Gun owners and gun advocates likewise reject the concept of “safe spaces” and regard the notion of “gun free zones” as a liability that invites rather than prevents acts of terrorism. In other words, gun control proposals designed to decrease fear have the opposite of their intended effect on those who view guns as symbols of personal safety, increasing rather than decreasing their fears independently of any actual effects on gun violence. Such policies are therefore non-starters, and will remain non-starters, for the sizeable proportion of Americans who regard guns as essential for self-preservation.

In 2006, Braman and Kahan noted that “the Great American Gun Debate… has convulsed the national polity for the better part of four decades without producing results satisfactory to either side” and argued that consequentialist arguments about public health risks based on cost–benefit analysis are trumped by the cultural meanings of guns to the point of being “politically inert” (Braman and Kahan, 2006 ). More than a decade later, that argument is iterated in this series on “What Guns Mean”. In this essay, it is further argued that persisting debates about the effectiveness of DGU and gun control legislation are at their heart trumped by shared concerns about personal safety, victimization, and mass shootings within a larger culture of fear, with polarized opinions about how to best mitigate those fears that are determined by the symbolic, cultural, and personal meanings of guns and gun ownership.

Coming full circle to the riddle, “Do guns kill people or do people kill people?”, a psychologically informed perspective rejects the question as a false dichotomy that can be resolved by the statement, “people kill people… with guns”. It likewise suggests a way forward by acknowledging both common fears and individual differences beyond the limited, binary caricature of the gun debate that is mired in endless arguments over disputed facts. For meaningful legislative change to occur, the debate must be steered away from its portrayal as two immutable sides caught between not doing anything on the one hand and enacting sweeping bans or repealing the 2nd Amendment on the other. In reality, public attitudes towards gun control are more nuanced than that, with support or opposition to specific gun control proposals predicted by distinct psychological and cultural factors (Wozniak, 2017 ) such that achieving consensus may prove less elusive than is generally assumed. Accordingly, gun reform proposals should focus on “low hanging fruit” where there is broad support such as requiring and enforcing universal background checks, enacting “red flag” laws balanced by guaranteeing gun ownership rights to law-abiding citizens, and implementing public safety campaigns that promote safe firearm handling and storage. Finally, the Dickey Amendment should be repealed so that research can inform public health interventions aimed at reducing gun violence and so that individuals can replace motivated reasoning with evidence-based decision-making about personal gun ownership and guns in society.

Aisch G, Keller J (2016). What happens after calls for new gun restrictions? Sales go up. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/12/10/us/gun-sales-terrorism-obama-restrictions.html . Accessed 19 Nov 2019.

Altheide DL (2019) The Columbine shootings and the discourse of fear. Am Behav Sci 52:1354–1370

Article Google Scholar

American Psychological Association (2019). One-third of US adults say fear of mass shootings prevents them from going to certain places or events. Press release, 15 August 2019. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2019/08/fear-mass-shooting . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Anglemeyer A, Horvath T, Rutherford G (2014) The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Int Med 160:101–110

Google Scholar

Atchley P, Atwood S, Boulton A (2011) The choice to text and drive in younger drivers: behavior may shape attitude. Accid Anal Prev 43:134–142

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ayres I, Donohue III JJ (2003) Shooting down the more guns, less crime hypothesis. Stanf Law Rev 55:1193–1312

Azrael D, Hemenway D (2000) ‘In the safety of your own home’: results from a national survey on gun use at home. Soc Sci Med 50:285–291

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Azrael D, Hepburn L, Hemenway D, Miller M (2017) The stock and flow of U.S. firearms: results from the 2015 National Firearms Survey. Russell Sage Found J Soc Sci 3:38–57

Barry CL, Webster DW, Stone E, Crifasi CK, Vernick JS, McGinty EE (2018) Public support for gun violence prevention policies among gun owners and non-gun owners in 2017. Am J Public Health 108:878–881

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bhatia R (2019). Guns, lies, and fear: exposing the NRA’s messaging playbook. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/guns-crime/reports/2019/04/24/468951/guns-lies-fear/ . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Braman D, Kahan DM (2006) Overcoming the fear of guns, the fear of gun control, and the fear of cultural politics: constructing a better gun debate. Emory Law J 55:569–607

Cook PJ, Ludwig J (1997). Guns in America: National survey on private ownership and use of firearms. National Institute of Justice. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/165476.pdf . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Chanel O, Chichilnisky G(2009) The influence of fear in decisions: Experimental evidence. J Risk Uncertain 39(3):271–298

Article MATH Google Scholar

Cook PJ, Ludwig J (1998) Defensive gun use: new evidence from a national survey. J Quant Criminol 14:111–131

Cramer CE, Burnett D (2012). Tough targets: when criminals face armed resistance from citizens. Cato Institute https://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/pubs/pdf/WP-Tough-Targets.pdf . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Craven J (2017). Why black people own guns. Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/black-gun-ownership_n_5a33fc38e4b040881bea2f37 . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Cummings P, Koepsell TD (1998) Does owning a firearm increase or decrease the risk of death? JAMA 280:471–473

Dahlberg LL, Ikeda RM, Kresnow M (2004) Guns in the home and risk of a violent death in the home: findings from a national study. Am J Epidemiol 160:929–936

Defilippis E, Hughes D (2015). The myth behind defensive gun ownership: guns are more likely to do harm than good. Politico. https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/01/defensive-gun-ownership-myth-114262 . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Depetris-Chauvin E (2015) Fear of Obama: an empirical study of the demand for guns and the U.S. 2008 presidential election. J Pub Econ 130:66–79

Doherty B (2015). How to count the defensive use of guns: neither survey calls nor media and police reports capture the importance of private gun ownership. Reason. https://reason.com/2015/03/09/how-to-count-the-defensive-use-of-guns/ . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Dowd-Arrow B, Hill TD, Burdette AM (2019) Gun ownership and fear. SSM Pop Health 8:100463

Fox JA, DeLateur MJ (2014) Mass shootings in America: moving beyond Newtown. Homicide Stud 18:125–145

Galea S, Abdalla SM (2019) The public’s health and the social meaning of guns. Palgrave Comm 5:111

Graham DA. The TSA doesn’t work—and never has. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/06/the-tsa-doesnt-work-and-maybe-it-doesnt-matter/394673/ . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Hahn RA, Bilukha O, Crosby A, Fullilove MT, Liberman A, Moscicki E, Synder S, Tuma F, Briss PA, Task Force on Community Preventive Services (2005) Firearms laws and the reduction of violence: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 28:40–71

Hansen PG, Skov LR, Skov KL (2016) Making healthy choices easier: regulation versus nudging. Annu Rev Public Health 37:237–51

Harriott M (2018). Report: white men stockpile guns because they’re afraid of black people. The Root. https://www.theroot.com/report-white-men-stockpile-guns-because-they-re-afraid-1823779218 . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Haselton MG, Nettle D (2006) The paranoid optimist: an integrative evolutionary model of cognitive biases. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 10:47–66

Hauser W, Kleck G (2013) Guns and fear: a one-way street? Crime Delinquency 59:271–291

Hemenway (1997) Survey research and self-defense gun use: an explanation of extreme overestimates. J Crim Law Criminol 87:1430–1445

Hemenway D, Azrael D, Miller M (2000) Gun use in the United States: results from two national surveys. Inj Prev 6:263–267

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hemenway D (2011) Risks and benefits of a gun in the home. Am J Lifestyle Med 5:502–511

Hibert M (2012) Toward a synthesis of cognitive biases: how noisy information processing can bias human decision making. Psychol Bull 138:211–237

Joslyn MR, Haider-Markel DP (2017) Gun ownership and self-serving attributions for mass shooting tragedies. Soc Sci Quart 98:429–442

Kahan DM, Braman D (2003) More statistics, less persuasion: a cultural theory of gun-risk perceptions. Univ Penn Law Rev 151:1291–1327

Kalesan B, Villarreal MD, Keyes KM, Galea S (2016) Gun ownership and social gun culture. Inj Prev 22:216–220

Kellermann AL, Reay DT (1986) Protection or peril? An analysis of fire-arm related deaths in the home. N Engl J Med 314:1557–1560

Kellermann AL, Rivara FP, Rushforth NB, Banton JG, Reay DT, Francisco JT, Locci A, Prodzinski J, Hackman BB, Somes G (1993) Gun ownership as a risk factor for homicide in the home. N Engl J Med 329:1084–1091

Kellerman AL, Somes G, Rivara F, Lee R, Banton J (1998) Injuries and deaths due to firearms in the home. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care 45:263–267

Kelly K (2019) I’m a left-wing anarchist. Guns aren’t just for right-wingero. Vox. https://www.vox.com/first-person/2019/7/1/18744204/guns-gun-control-anarchism . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Kleck G (2015) Defensive gun use is not a myth: why my critics still have it wrong. Politico. https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/02/defensive-gun-ownership-gary-kleck-response-115082 . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Kleck G, Kovandzic T, Saber M, Hauser W (2011) The effect of perceived risk and victimization on plans to purchase a gun for self-protection. J Crim Justice 39:312–319

Kleck G, Gertz M (1995) Armed resistance to crime: the prevalence and nature of self-defense with a gun. J Crim Law Criminol 86:150–187

Kleck G, Gertz M (1998) Carrying guns for protection: results from the national self-defense survey. J Res Crime Delinquency 35:193–224

Koper CS, Woods DJ, Roth JA (2004) An updated assessment of the federal assault weapons ban: impacts on gun markets and gun violence, 1994–2003. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/204431.pdf . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Kunda Z (1990) The case for motivated reasoning. Psychol Bull 108:480–498

Lee LK, Fleegler EW, Farrell C, Avakame E, Srinivasan S, Hemenway D, Monuteaux MC (2017) Firearm laws and firearm homicides: a systematic review. JAMA Int Med 177:106–119

Lerner JS, Li Y, Valdesolo P, Kassam KS (2015) Emotion and decision making. Ann Rev Psychol 66:799–823

Loewenstein GF, Weber EU, Hsee CK, Welch N (2001) Risk as feelings. Psychol Bull 127:267–286

Lott JR (1998) More guns, less crime. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Lott JR (1999) More guns, less crime: a response to Ayres and Donohue. Yale Law & Economics Research paper no. 247 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=248328 . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Matjasko JL, Cawley JH, Baker-Goering M, Yokum DV (2016) Applying behavioral economics to public health policy: illustrative examples and promising directions. Am J Prev Med 50:S13–S19

McDowall D, Loftin C, Presser S (2000) Measuring civilian defensive firearm use: a methodological experiment. J Quant Criminol 16:1–19

Mencken FC, Froese P (2019) Gun culture in action. Soc Prob 66:3–27

Metzl J (2019) What guns mean: the symbolic lives of firearms. Palgrave Comm 5:35

Article ADS Google Scholar

Moyer MW (2017). More guns do not stop more crimes, evidence shows. Sci Am https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/more-guns-do-not-stop-more-crimes-evidence-shows/ . Accessed 19 Nov 2019.

National Research Council (2005) Firearms and violence: a critical review. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC

O’Brien K, Forrest W, Lynott D, Daly M (2013) Racism, gun ownership and gun control: Biased attitudes in US whites may influence policy decisions. PLoS ONE 8(10):e77552

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Pachur T, Hertwig R, Steinmann F (2012) How do people judge risks: availability heuristic, affect heuristic, or both? J Exp Psychol Appl 18:314–330

Pederson J, Hall TL, Foster B, Coates JE (2015) Gun ownership and attitudes toward gun control in older adults: reexamining self interest theory. Am J Soc Sci Res 1:273–281

Pew Research Center (2017) America’s complex relationship with guns. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2017/06/Guns-Report-FOR-WEBSITE-PDF-6-21.pdf . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Pierre JM (2015) The psychology of guns. Psych Unseen. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/psych-unseen/201510/the-psychology-guns . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Pluviano S, Watt C, Della Salla S (2017) Misinformation lingers in memory: failure of three pro-vaccination strategies. PLoS ONE 23(7):e0811640

RAND (2018) The challenges of defining and measuring defensive gun use. https://www.rand.org/research/gun-policy/analysis/essays/defensive-gun-use.html . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Rogers P, Webley P (2001) “It could be us!”: cognitive and social psychological factors in UK National Lottery play. Appl Psychol Int Rev 50:181–199

Rostron A (2018) The Dickey Amendment on federal funding for research on gun violence: a legal discussion. Am J Public Health 108:865–867

Slovic P, Finucane ML, Peters E, MacGregor DG (2007) The affect heuristic. Eur J Oper Res 177:1333–1352

Smith TW (1997) A call for a truce in the DGU war. J Crim Law Criminol 87:1462–1469

Smith JA (2018) Why are white men stockpiling guns? Sci Am Blogs. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/why-are-white-men-stockpiling-guns/ . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Smith TW, Son J (2015). General social survey final report: Trends in gun ownership in the United States, 1972–2014. http://www.norc.org/PDFs/GSS%20Reports/GSS_Trends%20in%20Gun%20Ownership_US_1972-2014.pdf . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Stroebe W, Leander NP, Kruglanski AW (2017) Is it a dangerous world out there? The motivational biases of American gun ownership. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 43:1071–1085

Stroud A (2012) Good guys with guns: hegemonic masculinity and concealed handguns. Gend Soc 26:216–238

Sunstein CR (2003) Terrorism and probability neglect. J Risk Uncertain 26:121–136

Sunstein CR, Zeckhauser R (2011) Overreaction to fearsome risks. Environ Resour Econ 48:435–449

Tark J, Kleck G (2004) Resisting crime: the effects of victim action on the outcomes of crimes. Criminol 42:861–909

Tversky A, Kahneman D (1974) Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science 185:1124–1131

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Vacha EF, McLaughlin TF (2000) The impact of poverty, fear of crime, and crime victimization on keeping firearms for protection and unsafe gun-storage practices” A review and analysis with policy recommendations. Urban Educ 35:496–510

Vacha EF, McLaughlin TF (2004) Risky firearms behavior in low-income families of elementary school children: the impact of poverty, fear of crime, and crime victimization on keeping and storing firearms. J Fam Violence 19:175–184

Wallace LN (2015) Responding to violence with guns: mass shootings and gun acquisition. Soc Sci J 52:156–167

Webster DW, Wintemute GJ (2015) Effects of policies designed to keep firearms from high-risk individuals. Ann Rev Public Health 36:21–37

Wertz J, Azrael D, Hemenway D, Sorenson S, Miller M (2018) Differences between new and long-standing US gun owners: results from a National Survey. Am J Public Health 108:871–877

Wiebe DJ (2003) Homicide and suicide risks associated with firearms in the home: a national case-control study. Ann Emerg Med 47:771–782

Willis J (2010). I was anti-gun, until I got stalked. Salon. https://www.salon.com/2010/10/21/buying_gun_protect_from_stalker/ . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Wintemute GJ (2008) Guns, fear, the constitution, and the public’s health. N. Engl J Med 358:1421–1424

Wolfson JA, Teret SP, Azrael D, Miller M (2017) US public opinion on carrying firearms in public places. Am J Public Health 107:929–937

Wolpert RM, Gimpel JG (1998) Self-interest, symbolic politics, and public attitudes toward gun control. Polit Behav 20:241–262

Wozniak KH (2017) Public opinion about gun control post-Sandy Hook. Crim Just Pol Rev 28:255–278

Wuertenberg N (2018). Gun rights are about keeping white men on top. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/made-by-history/wp/2018/03/09/gun-rights-are-about-keeping-white-men-on-top . Accessed 19 Nov 2019

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, Los Angeles, USA

Joseph M. Pierre

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Joseph M. Pierre .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Pierre, J.M. The psychology of guns: risk, fear, and motivated reasoning. Palgrave Commun 5 , 159 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0373-z

Download citation

Received : 30 July 2019

Accepted : 27 November 2019

Published : 10 December 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0373-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Packing heat: on the affective incorporation of firearms.

- Jussi A. Saarinen

Topoi (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The major tests US gun control activists face in 2024

Gun safety groups say they remain undaunted as they plan to push for more change – but they will still face steep hurdles in a crucial election year