- Privacy Policy

Transition Words and Phrases for Japanese Essays

June 9, 2020

By Alexis Papa

Are you having a hard time connecting between your ideas in your Japanese essay? In this article, we have listed useful transition words and phrases that you can use to help you let your ideas flow and have an organized essay.

Japanese Phrases for Giving Examples and Emphasis

For example,

がいこく、たとえばちゅうごくへいったことがありますか。 Gaikoku, tatoeba Chuugoku e itta koto ga arimasu ka?

Have you been abroad, for instance China?

たぶんちゅうごくへいったことがあります。 Tabun Chuugoku e itta koto ga arimasu.

I have probably been to China.

Japanese Essay Phrases: General Explaining

しけんにごうかくするのために、まじめにべんきょうしなきゃ。 Shiken ni goukaku suru no tame ni, majime ni benkyou shinakya.

In order to pass the exam, I must study.

あしたあめがふるそう。だから、かさをもってきて。 Ashita ame ga furu sou. Dakara, kasa wo motte kite.

It seems that it will rain tomorrow. So, bring an umbrella.

Showing Sequence

まず、あたらしいさくぶんのがいせつをしようとおもう。 Mazu, atarashii sakubun no gaisetsu wo shiyou to omou.

First, I am going to do an outline of my new essay.

つぎに、さくぶんをかきはじめます。 Tsugi ni, sakubun wo kaki hajimemasu.

Then, I will begin writing my essay.

Adding Supporting Statements

かれはブレーキをかけ、そしてくるまはとまった。 Kare wa bureki wo kake, soshite kuruma wa tomatta.

He put on the brakes and then the car stopped.

いえはかなりにみえたし、しかもねだんがてごろだった。 Ie wa kanari ni mieta shi, shikamo nedan ga tegoro datta.

The house looked good; moreover,the (selling) price was right.

Demonstrating Contrast

にほんごはむずかしいですが、おもしろいです。 Nihongo wa muzukashii desu ga, omoshiroi desu.

Although Japanese language is difficult, it is enjoyable.

にほんごはむずかしいです。でも、おもしろいです。 Nihongo wa muzukashii desu. Demo, omoshiroi desu.

Japanese language is difficult. Nevertheless, it is enjoyable.

にほんごはむずかしいです。しかし、おもしろいです。 Nihondo wa muzukashii desu. Shikashi, omoshiroi desu.

Japanese language is difficult. However, it is enjoyable.

にほんごはむずかしいですけれど、おもしろいです。 Nihongo wa muzakashii desu keredo, omoshiroi desu.

Japanese Essay Phrases for Summarizing

われわれはこのはなしはじつわだというけつろんにたっした。 Wareware wa kono hanashi wa jitsuwa da to iu ketsuron ni tasshita.

We have come to a conclusion that this is a true story.

Now that you have learned these Japanese transitional words and phrases, we hope that your Japanese essay writing has become easier. Leave a comment and write examples of sentences using these Japanese essay phrases!

Alexis Papa

Alexis is a Japanese language and culture enthusiast from the Philippines. She is a Japanese Studies graduate, and has worked as an ESL and Japanese instructor at a local language school. She enjoys her free time reading books and watching series.

Your Signature

Subscribe to our newsletter now!

LEARN JAPANESE WITH MY FREE LEARNING PACKAGE

- 300 Useful Japanese Adjectives E-book

- 100 Days of Japanese Words and Expressions E-book

Sign up below and get instant access to the free package!

Unconventional language hacking tips from Benny the Irish polyglot; travelling the world to learn languages to fluency and beyond!

Looking for something? Use the search field below.

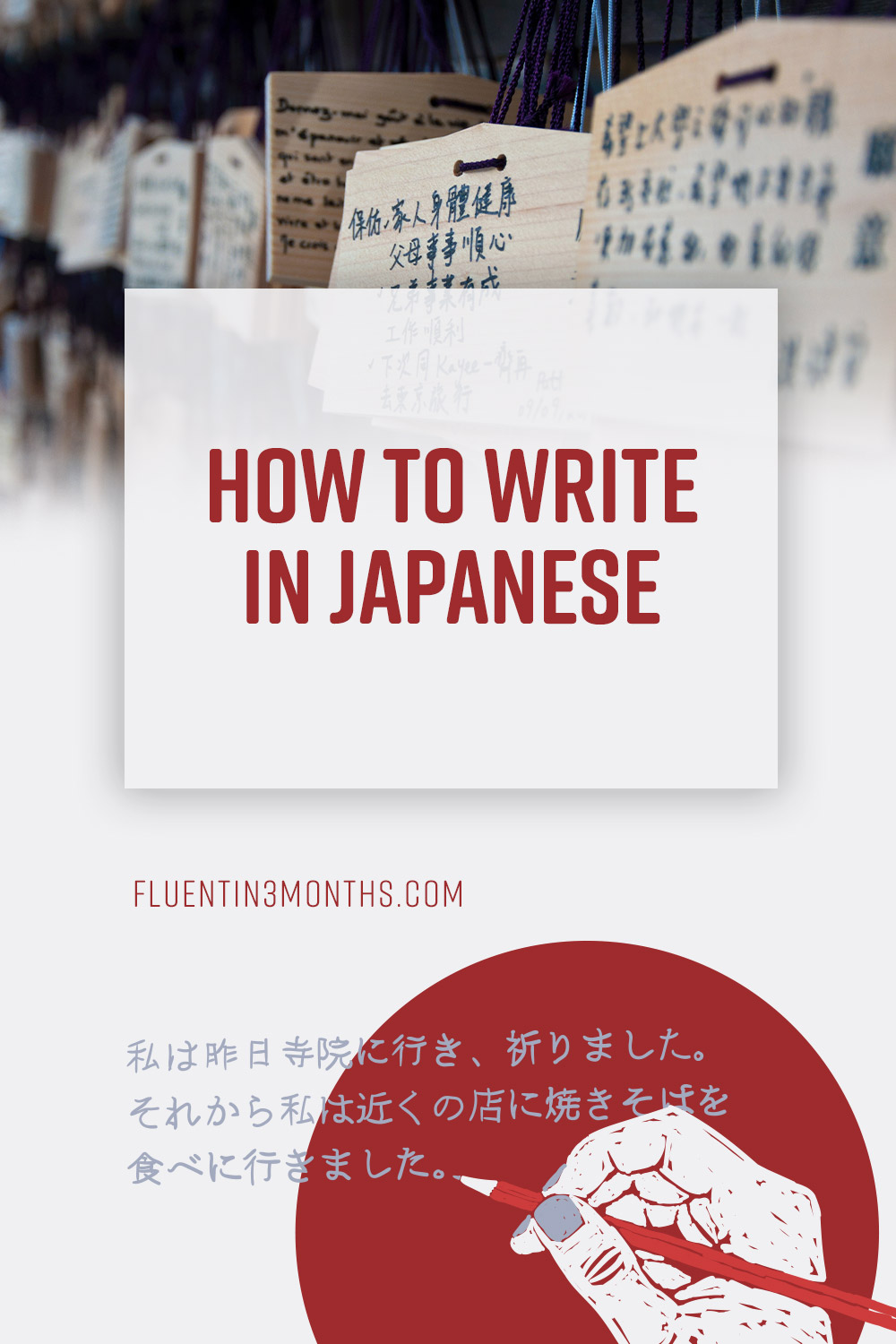

Home » Articles » How to Write in Japanese — A Beginner’s Guide to Japanese Writing

Full disclosure: This post contains affiliate links. ?

written by Caitlin Sacasas

Language: Japanese

Reading time: 13 minutes

Published: Apr 2, 2021

Updated: Oct 18, 2021

How to Write in Japanese — A Beginner’s Guide to Japanese Writing

Does the Japanese writing system intimidate you?

For most people, this seems like the hardest part of learning Japanese. How to write in Japanese is a bit more complex than some other languages. But there are ways to make it easier so you can master it!

Here at Fluent in 3 Months , we encourage actually speaking over intensive studying, reading, and listening. But writing is an active form of learning too, and crucial for Japanese. Japanese culture is deeply ingrained in its writing systems. If you can’t read or write it, you’ll struggle as you go along in your studies.

Some of the best Japanese textbooks expect you to master these writing systems… fast . For instance, the popular college textbook Genki , published by the Japan Times, expects you to master the basics in as little as a week. After that, they start to phase out the romanized versions of the word.

It’s also easy to mispronounce words when they’re romanized into English instead of the original writing system. If you have any experience learning how to write in Korean , then you know that romanization can vary and the way it reads isn’t often how it’s spoken.

Despite having three writing systems, there are benefits to it. Kanji, the “most difficult,” actually makes memorizing vocabulary easier!

So, learning to write in Japanese will go a long way in your language studies and help you to speak Japanese fast .

Why Does Japanese Have Three Writing Systems? A Brief Explainer

Japanese has three writing systems: hiragana, katakana, and kanji. The first two are collectively called kana and are the basics of writing in Japanese.

Writing Kana

If you think about English, we have two writing systems — print and cursive. Both print and cursive write out the same letters, but they look “sharp” and “curvy.” The same is true for kana. Hiragana is “curvy” and katakana is “sharp,” but they both represent the same Japanese alphabet (which is actually called a syllabary). They both represent sounds, or syllables, rather than single letters (except for vowels and “n”, hiragana ん or katakana ン). Hiragana and katakana serve two different purposes.

Hiragana is the most common, and the first taught to Japanese children. If this is all you learn, you would be understood (although you’d come across child-like). Hiragana is used for grammar functions, like changing conjugation or marking the subject of a sentence. Because of this, hiragana helps break up a sentence when combined with kanji. It makes it easier to tell where a word begins and ends, especially since Japanese doesn’t use spaces. It’s also used for furigana, which are small hiragana written next to kanji to help with the reading. You see furigana often in manga , Japanese comics, for younger audiences who haven’t yet learned to read all the kanji. (Or learners like us!)

Katakana serves to mark foreign words. When words from other languages are imported into Japanese, they’re often written in Japanese as close as possible to the original word. (Like how you can romanize Japanese into English, called romaji). For example, パン ( pan ) comes from Spanish, and means “bread.” Or from English, “smartphone” is スマートフォン ( suma-tofon ) or shortened, slang form スマホ ( sumaho ). Katakana can also be used to stylistically write a Japanese name, to write your own foreign name in Japanese, or to add emphasis to a word when writing.

Writing Kanji

Then there’s kanji. Kanji was imported from Chinese, and each character means a word, instead of a syllable or letter. 犬, read inu , means “dog.” And 食, read ta or shoku , means “food” or “to eat.” They combine with hiragana or other kanji to complete their meaning and define how you pronounce them.

So if you wanted to say “I’m eating,” you would say 食べます ( tabemasu ), where -bemasu completes the verb and puts it in grammatical tense using hiragana. If you wanted to say “Japanese food,” it would be 日本食 ( nipponshoku ), where it’s connected to other kanji.

If you didn’t have these three forms, it would make reading Japanese very difficult. The sentences would run together and it would be confusing. Like in this famous Japanese tongue twister: にわにはにわにわとりがいる, or romanized niwa ni wa niwa niwatori ga iru . But in kanji, it looks like 庭には二羽鶏がいる. The meaning? “There are chickens in the garden.” Thanks to the different writing systems, we know that the first niwa means garden, the second ni wa are the grammatical particles, the third niwa is to say there are at least two, and niwatori is “chickens.”

Japanese Pronunciation

Japanese has fewer sounds than English, and except for “r,” most of them are in the English language. So you should find most of the sounds easy to pick up!

Japanese has the same 5 vowels, but only 16 consonants. For the most part, all syllables consist of only a vowel, or a consonant plus a vowel. But there is the single “n,” and “sh,” “ts,” and “ch” sounds, as well as consonant + -ya/-yu/-yo sounds. I’ll explain this more in a minute.

Although Japanese has the same 5 vowel sounds, they only have one sound . Unlike English, there is no “long A” and “short A” sound. This makes it easy when reading kana because the sound never changes . So, once you learn how to write kana, you will always know how to pronounce it.

Here’s how the 5 vowels sound in Japanese:

- あ / ア: “ah” as in “latte”

- い / イ: “ee” as in “bee”

- う / ウ: “oo” as in “tooth”

- え / エ: “eh” as in “echo”

- お / オ: “oh” as in “open”

Even when combined with consonants, the sound of the vowel stays the same. Look at these examples:

- か / カ: “kah” as in “copy”

- ち / チ: “chi” as in “cheap”

- む / ム: “mu” as in “move”

- せ / セ: “se” as in “set”

- の / ノ: “no” as in “note”

Take a look at the entire syllabary chart:

Based on learning how to pronounce the vowels, can you pronounce the rest of the syllables? The hardest ones will be the R-row of sounds, “tsu,” “fu,” and “n.”

For “r” it sounds between an “r” and an “l” sound in English. Almost like the Spanish, actually. First, try saying “la, la, la.” Your tongue should push off of the back of your teeth to make this sound. Now say “rah, rah, rah.” Notice how your tongue pulls back to touch your back teeth. Now, say “dah, dah, dah.” That placement of your tongue to make the “d” sound is actually where you make the Japanese “r” sound. You gently push off of this spot on the roof of your mouth as you pull back your tongue like an English “r.”

“Tsu” blends together “t” and “s” in a way we don’t quite have in English. You push off the “t” sound, and should almost sound like the “s” is drawn out. The sound “fu” is so soft, and like a breath of air coming out. Think like a sigh, “phew.” It doesn’t sound like “who,” but a soft “f.” As for our lone consonant, “n” can sound like “n” or “m,” depending on the word.

Special Japanese Character Readings and How to Write Them

There are a few Japanese characters that combine with others to create more sounds. You’ll often see dakuten , which are double accent marks above the character on the right side ( ゙), and handakuten , which is a small circle on the right side ( ゚).

Here’s how dakuten affect the characters:

And handakuten are only used with the H-row characters, changing it from “h” to “p.” So か ( ka ) becomes が ( ga ), and ひ ( hi ) becomes either び ( bi ) or ぴ ( pi ).

A sokuon adds a small っ between two characters to double the consonant that follows it and make a “stop” in the word. In the saying いらっしゃいませ ( irasshaimase , “Welcome!”), the “rahs-shai” has a slight glottal pause where the “tsu” emphasizes the double “s.”

One of the special readings that tend to be mispronounced are the yoon characters. These characters add a small “y” row character to the other rows to blend the sounds together. These look like ちゃ ( cha ), きょ ( kyo ), and しゅ ( shu ). They’re added to the “i” column of kana characters.

An example of a common mispronunciation is “Tokyo.” It’s often said “Toh-key-yo,” but it’s actually only two syllables: “Toh-kyo.” The k and y are blended; there is no “ee” sound in the middle.

How to Read, Write, and Pronounce Kanji Characters

Here’s where things get tricky. Kanji, since it represents a whole word or idea, and combines with hiragana… It almost always has more than one way to read and pronounce it. And when it comes to writing them, they have a lot more to them.

Let’s start by breaking down the kanji a bit, shall we?

Most kanji consist of radicals, the basic elements or building blocks. For instance, 日 (“sun” or “day”) is a radical. So is 言 (“words” or “to say”) and 心 (“heart”). So when we see the kanji 曜, we see that “day” has been squished in this complex kanji. This kanji means “day of the week.” It’s in every weekday’s name: 月曜日 ( getsuyoubi , “Monday”), 火曜日 ( kayoubi , “Tuesday”), 水曜日 ( suiyoubi , “Wednesday”), etc.

When the kanji for “words” is mixed into another kanji, it usually has something to do with conversation or language. 日本語 ( nihongo ) is the word for “Japanese” and the final kanji 語 includes 言. And as for 心, it’s often in kanji related to expressing emotions and feelings, like 怒る ( okoru , “angry”) and 思う ( omou , “to think”).

In this way, some kanji make a lot of sense when we break them down like this. A good example is 妹 ( imouto ), the kanji for “little sister.” It’s made up of two radicals: 女, “woman,” and 未, “not yet.” She’s “not yet a woman,” because she’s your kid sister.

So why learn radicals? Because radicals make it easier to memorize, read, and write the kanji. By learning radicals, you can break the kanji down using mnemonics (like “not yet a woman” to remember imouto ). If you know each “part,” you’ll remember how to write it. 妹 has 7 strokes to it, but only 2 radicals. So instead of memorizing tons of tiny lines, memorize the parts.

As for pronouncing them, this is largely a memorization game. But here’s a pro-tip. Each kanji has “common” readings — often only one or two. Memorize how to read the kanji with common words that use them, and you’ll know how to read that kanji more often than not.

Japanese Writing: Stroke Order

So, I mentioned stroke order with kanji. But what is that? Stroke order is the proper sequence you use to write Japanese characters.

The rule of stroke order is you go from top to bottom, left to right.

This can still be confusing with some complex kanji, but again, radicals play a part here. You would break down each radical top left-most stroke to bottom right stroke, then move on to the next radical. A helpful resource is Jisho.org , which shows you how to properly write all the characters. Check out how to write the kanji for “kanji” as a perfect example of breaking down radicals.

When it comes to kana, stroke order still matters. Even though they’re simpler, proper stroke order makes your characters easier to read. And some characters rely on stroke order to tell them apart. Take シ and ツ:

[Shi and Tsu example]

If you didn’t use proper stroke order, these two katakana characters would look the same!

How to Memorize Japanese Kanji and Kana

When it comes to Japanese writing, practice makes perfect. Practice writing your sentences down in Japanese, every day. Practice filling in the kana syllabary chart for hiragana and katakana, until there are no blank boxes and you’ve got them all right.

Create mnemonics for both kanji and kana. Heisig’s method is one of the best ways to memorize how to write kanji with mnemonics. Using spaced repetition helps too, like Anki. Then you’re regularly seeing each character, and you can input your mnemonics into the note of the card so you have it as a reminder.

Another great way to practice is to write out words you already know. If you know mizu means “water,” then learn the kanji 水 and write it with the kanji every time from here on out. If you know the phrase おはようございます means “good morning,” practice writing in in kana every morning. That phrase alone gives you practice with 9 characters and two with dakuten! And try looking up loan words to practice katakana.

Tools to Help You with Japanese Writing

There are some fantastic resources out there to help you practice writing in Japanese. Here are a few to help you learn it fast:

- JapanesePod101 : Yes, JapanesePod101 is a podcast. But they often feature YouTube videos and have helpful PDFs that teach you kanji and kana! Plus, you’ll pick up all kinds of helpful cultural insights and grammar tips.

- LingQ : LingQ is chock full of reading material in Japanese, giving you plenty of exposure to kana, new kanji, and words. It uses spaced repetition to help you review.

- Skritter : Skritter is one of the best apps for Japanese writing. You can practice writing kanji on the app, and review them periodically so you don’t forget. It’s an incredible resource to keep up with your Japanese writing practice on the go.

- Scripts : From the creator of Drops, this app was designed specifically for learning languages with a different script from your own.

How to Type in Japanese

It’s actually quite simple to type in Japanese! On a PC, you can go to “Language Settings” and click “Add a preferred language.” Download Japanese — 日本語 — and make sure to move it below English. (Otherwise, it will change your laptop’s language to Japanese… Which can be an effective study tool , though!)

To start typing in Japanese, you would press the Windows key + space. Your keyboard will now be set to Japanese! You can type the romanized script, and it will show you the suggestions for kanji and kana. To easily change back and forth between Japanese and English, use the alt key + “~” key.

For Mac, you can go to “System Preferences”, then “Keyboard” and then click the “+” button to add and set Japanese. To toggle between languages, use the command key and space bar.

For mobile devices, it’s very similar. You’ll go to your settings, then language and input settings. Add the Japanese keyboard, and then you’ll be able to toggle back and forth when your typing from the keyboard!

Japanese Writing Isn’t Scary!

Japanese writing isn’t that bad. It does take practice, but it’s fun to write! It’s a beautiful script. So, don’t believe the old ideology that “three different writing systems will take thousands of hours to learn!” A different writing system shouldn’t scare you off. Each writing system has a purpose and makes sense once you start learning. They build on each other, so learning it gets easier as you go. Realistically, you could read a Japanese newspaper after only about two months of consistent studying and practice with kanji!

Caitlin Sacasas

Content Writer, Fluent in 3 Months

Caitlin is a copywriter, content strategist, and language learner. Besides languages, her passions are fitness, books, and Star Wars. Connect with her: Twitter | LinkedIn

Speaks: English, Japanese, Korean, Spanish

Have a 15-minute conversation in your new language after 90 days

- Top page -->>

- Japan Guide & Information -->>

- Learning -->>

How to improve your writing skills in Japanese

UPDATE | October 1, 2022

The ability to write Japanese, which is necessary for living in Japan. Here are four recommended ways to do just that.

- Copying example sentences from Japanese textbooks and reference books

- Write a 3-line diary in Japanese

- Decide on a theme and write a short essay.

- Post to SNS. write a comment. send a message.

In order to go on to higher education or find a job in Japan, you need to be able to write in Japanese. What kind of training do you do to improve your writing skills in Japanese? What should I do to improve my writing ability?

In this column, I will introduce four ways to improve your writing skills in Japanese!

1. Copy the example sentences from Japanese textbooks and reference books

Do you have any Japanese textbooks or reference books? The book can be used not only for reading, but also for improving your writing skills. It's easy to do. Just write an example sentence. You can write the example sentences in a notebook, or you can write them using computer software.

This method is very easy, but it can be a little boring. However, the example sentences in recent textbooks are created by Japanese teachers considering whether they will really use them in their daily lives. Therefore, if you write down the example sentences and memorize them as they are, they will be useful in your daily life.

If you write example sentences properly, you will be able to memorize grammar and words at the same time. If you think writing example sentences is too easy, start from the last page of your textbook. Many people haven't read the last page (maybe for the first time!), so it's a great practice.

2. Write a 3-line diary in Japanese

The next method is to write a diary in Japanese. Don't you think you have to write long sentences in your diary? But short sentences are fine. Write a lot of short sentences, until you have three lines. It can be a little tough at first.

When writing a diary, you don't have to write "I'm amazing". Rather than that, let's honestly write "bad self". "I couldn't study today," "I couldn't do the laundry even though the weather was nice," or "I slept until noon."

After I write about myself, I write about what happened today and what I noticed. "I took a walk and the wind felt good," "It seems that the neighborhood bakery is closed today," and "It's nice weather." If you write every day, you will get used to "writing".

3. Decide on a theme and try to write a mini composition.

A third way is to write an essay. Think writing is difficult? Actually, it's the same as a diary, and you should keep writing down what you're thinking. This composition is to improve your writing skills, so you don't have to show it to anyone. So feel free to get started.

It may be difficult to decide on a theme for writing, so I prepared a few themes. From the themes below, choose one that you think you can write, and try to write it in 200 to 400 characters. Even if it's not the theme below, you can write what you want to write.

"self-introduction" "Things I want to do in Japan" "My favorite 〇〇" "How to study Japanese" "How to spend your day off" "Friend 〇〇" "Let me introduce you to my family." "Recommended shop" "How to cook national dishes" "What I want to study more"

4. Post to SNS. write a comment. send a message.

Have you ever sent a message in Japanese on SNS (LINE, Facebook, Twitter, etc.)? You can improve your Japanese writing skills by using Japanese on SNS and messaging apps. However, the thing to be careful about with SNS is that there are people who read it.

Send messages with the other person in mind so that the person reading the message doesn't feel bad. The same is true when posting on SNS or writing comments.

And Japanese on SNS and messaging apps often uses "spoken language" rather than "written language". It's a different style of word than the Japanese used for higher education or job hunting, so be careful when using it properly. SNS is fun, so I want to make good use of it to improve my Japanese writing skills.

This time, I introduced four ways to improve your writing skills in Japanese. Please feel free to challenge yourself in whatever way you like. See you in the next column!

I teach Japanese at Japanese language schools and universities in Kyushu. I love games and manga. I also work as a coordinator and web writer to create a local Japanese language class for those who are studying Japanese.

September 20, 2022

【International Student Interview】 Meiji University (MEIJI UNIVERSITY)

June 15, 2022

【International Student Interview】Kanagawa University

August 19, 2021

February 01, 2022

[For Japanese language schools] Why don't you teach Japanese through manga at "Trial Manga Library"?

May 27, 2022

What is a famous school-oriented cram school?

Recommended articles.

March 05, 2019

3 reasons why you should start a "school search" right now

January 16, 2019

Three points to find a “school that suits you”

“How to Gather Japanese School Information” Guide for International Students

January 09, 2019

“Scholarship” guide for international students

Useful tips.

- KU Libraries

- Subject & Course Guides

- Resource Guide for Japanese Language Students

Resource Guide for Japanese Language Students: Essays

- Short Stories

- Translated Foreign Literature

- Japanese and English

- Comics with Furigana

- Comics with no Furigana

- Picture Books

- Online Reading Materials

- Apps, Sites, Extensions, and Podcasts

- For Listening Practice: Read Aloud Picture Books

- For Listening Practice: Children's Literature

- For Listening Practice: Young Adults

- Japanese-Language Proficiency Test (JLPT)

- Japanese Research & Bibliographic Methods for Undergraduates

- Japan Studies This link opens in a new window

- Guidebooks for Academic and Business Writing

About This Page

This page introduces the variety of essays written by popular contemporary authors. Unless noted, all are in Japanese.

The author, さくらももこ, is known for writing a comic titled 『 ちびまる子ちゃん 』. The comic is based on her own childhood experiences and depicts the everyday life of a girl with a nickname of Chibi Maruko-chan. The author has been constantly writing casual and humorous essays, often recollecting her childhood memories. We have both the『 ちびまる子ちゃん 』 comic series and other essays by the author.

To see a sample text in a new tab, please click on the cover image or the title .

中島らも(1952-2004) started his career as a copyrigher but changed his path to become a prolific writer, publishing novels, essays, drama scripts and rakugo stories. He became popular with his "twisted sense of humour." He is also active in the music industry when he formed his own band. He received the 13th Eiji Yoshikawa New Author Prize with his 『今夜、すべてのバーで』 and Mystery Writers of Japan Aaward with 『 ガダラの豚 』.

東海林(しょうじ)さだお

東海林さだお(1937-) is a well-known cartoonist, but he is also famous for his essays on food. His writing style is light and humorous and tends to pay particular attention toward regular food, such as bananas, miso soup, and eggd in udon noodles, rather than talk about gourmet meals. (added 5/2/2014)

Collection of Essays: 天声人語 = Vox Populi, Vox Deli (Bilingual)

A collection of essays which appear on the front page of Asahi Shinbun . Each essay is approx. 600 words. KU has collections published around 2000. Seach KU Online catalog with call number AC145 .T46 for more details.

To see a sample text, please click on the cover image or the title .

Other Essays

Online Essay

- 村上さんのところ "Mr. Murakami's Place" -- Haruki Murakami's Advice Column Part of Haruki Murakami's official site. He answers questions sent to this site. He will also take questions in English. Questions will be accepted until Jan. 31, 2015.

Search from KU Collection

If you are looking for essays in Japanese available at KU, use this search box. If you know the author, search by last name, then first name, such as "Sakura, Momoko." Make sure to select "Author" in the search field option.:

- << Previous: Level 4

- Next: Short Stories >>

- Last Updated: Feb 1, 2024 11:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.ku.edu/c.php?g=95189

Free Shipping from $225 | Shipping Updates

Discover trending products from Japan.

Shopping Cart

Continue Shopping

Welcome to OMG Japan!

How to Write Japanese Essays

Product Description

A new and revised edition of this book is now available here: How to Write Japanese Essays - 2nd Edition

If you are planning to study at a Japanese University or work at a Japanese company, your Japanese writing skills will need to be at an academic level. This book is a good guide for writing essays/papers in Japanese. It offers help with essay structure, from the first paragraph right through to the summary. It also teaches correct punctuation and quotation use, in addition to the construction of explanations. You will also learn suitable vocabulary/expressions to use in essays/papers; these are often very different from casual writing and spoken Japanese. It will also help you to improve your spoken Japanese for formal situations. The book includes a lot of practice essays and sections for you to test yourself with. This book is aimed at upper-intermediate to advanced learners. 122 pages language: Japanese

Customer Reviews

Related products.

Tobira II: Beginning Japanese Workbook 1

EJU Reading Comprehension - Points & Practice

The News in Japanese 50 - Listening for Upper Intermediate and Advanced students

Kit Kat Milky Ice Cream Flavor

Conan's Vocabulary Adventure: Learn 1000 Challenging Words by Age 10

Elementary Japanese: PANORAMA - Fast-Track to Mastery in Just 12 Grammar Points

Compass Japanese Intermediate Resource Book

Pretz Osatsu Sweet Potato

Pringles Triple Sour Cream and Onion

Black Thunder

Fundodai Clear Soy Sauce with a Golden Leaf [limited edition]

Starbucks Stainless TOGO Logo Tumbler Peachful Paradise 355ml - Japan Summer Edition 2023

Quick links.

- Important Shipping Updates

- Blog - Pop Culture

- Blog - Learn Japanese

- Terms of Service

- Refund policy

Become an Affiliate

Keep in touch.

Short essay: Thoughts on learning to speak and write in a foreign language… naturally

When learning a foreign language, I think we all tend to go through stages. First, we may have a mild (or major) interest in the culture of a foreign country, and begin to pick up a few words here or there in that country’s native language. In the case of Japanese, it might be a few phrases from subtitled Anime where it’s easy to pick words that frequently appear. I still vividly remember learning one of my first Japanese expressions from a good friend in high school: “ Hajimemashite, douzo yoroshiku onegaishimasu “.

The next stage involves more formal learning by taking one or more classes or devoting some of your spare time to properly learn the basics of the language, especially grammar, pronunciation, and alphabet(s). For many people, memorizing isn’t that challenging (given the time and effort), but the tricky part here is to start learning the ins and outs of that language’s grammar, including certain tendencies that are different from one’s native language, like how in Japanese subjects are often omitted.

After a few years of extensive study, most people can probably manage to figure out the meaning of text in that language, assuming they have access to a dictionary. Learning to understand spoken language can be much tricker due to differences individual speech (in Japanese there are significant differences across genders and ages) and also due to regional accents/dialects. But, even for listening, I think practice really does make perfect, at least in the sense that you “understand enough” to either enjoy the content in that language, or learn something from it. For reading and listening, which I’ll call passive tasks, there is typically so much context to go by that you can just guess things as you go–essentially every sentence becomes a mini puzzle. If you are living your day-to-day life in that language, any misunderstandings you have about the meaning of a certain expression will probably get ironed out by time, as you undertake a gradual process of trial and error.

Now we come to the real challenge: the active tasks of writing and speaking in a foreign language. It depends on the person, but for me I feel speaking is generally the harder of these two. One reason is that you typically have to respond in real time, and the other is the need to be concerned about pronunciation, not only of individual words but also of phrases, since in Japanese the intonation of words can influence words later in the sentence. You also have to worry about things like aizuchi (words used to show you are listening, like “ sou desu ka “) and words that show you are thinking (like “ etto… ” which is a little similar to the English “umm…”). You also have to inflect your speech to express your emotions. Finally, you need a conversation partner in order to make any progress. This condition alone means that self-taught students who don’t live in a country which speaks that language will have a very hard time of getting to an advanced level in their speech.

There are some advantages to learning to speak as compared to learning to write. For example, when speaking there is a quick feedback cycle between expressing something and getting a response. Although it’s usually pretty hard to find someone to correct your mistakes during a conversation (except maybe a private tutor who is paid for that), there is often an opportunity to reuse an expression you just heard, which allows you to cement it in your memory for more easy recall later.

Learning to write, on the other hand, lacks many of the difficult aspects of learning to speak, like pronunciation and a need to respond in real time. For those doing self-study, especially those living outside of Japan, it should be easier to pick up writing (and by writing, I am mostly referring to inputting with a keyboard, though writing by hand is also included) because there is nearly an infinite set of resources available in the form of websites and in many books which can be pretty easily acquired from online retailers. One can also write all day long, in the form of a blog or essay, without needing anyone available at that moment (unlike speaking which usually requires a partner). So, in a certain sense, you can study writing as much as your free time allows.

However, herein lies one of the challenges of learning to write natively. Just as with speech, it is pretty difficult to find someone to correct your mistakes on somewhere like a daily blog. The problem comes when you know just enough grammar and vocabulary to be dangerous, meaning that you can just start writing nearly anything that comes to mind, using only a dictionary and knowledge of grammar rules. However, if you are not careful you might end with extremely unnatural prose that sounds like something that came out of a computer translator. Ok, maybe not that horrific, but you get the point.

Getting to the final stage, where you can write like a native, such that none of your language has the scent of your native language, is quite a challenge, and I feel many people are never able to achieve this goal. I myself still have a long way to come, though I tell myself this is because I have placed an emphasis on passive Japanese (i.e. reading and listening) over active for many of my years of study.

Completely natural writing (as well as speech) requires not just learning a complete set of grammar rules to build sentences with, but also a large set of exceptions , without necessarily any logic behind them. To put it another way–how often have you read the text written by a non-native speaker of your native tongue and said to yourself “this just doesn’t feel right”. It isn’t technically grammatically incorrect, and there is no official rule that has been broken. Some of this can be explained by the linguistic phenomenon called “collocation” which describes how certain groups of words are used more commonly together than others.

To help get your writing to sound more natural, I suggest you try and create a tight feedback loop which mimics a conversation. This means that you should favor writing emails (either to a friend or coworker) over writing a blog. When writing emails, try to force yourself to reuse words and expressions used by the person you are communicating with (hopefully a native speaker). Also, if you say something unnatural it’s more likely to be pointed out as opposed to a blog where mistakes can sit for years on a webpage without anyone pointing them out. Text chat provides an even shorter feedback loop (nearly immediate), though you should keep in mind the expressions you learn from chatting with someone may not be applicable to an email or other more formal type of writing (think of the abbreviation “l8r” used in English chat, which would be strange to use in a business email).

If you really want to keep a blog in a foreign language, I recommend reading other blogs written by native speakers immediately before and after you make a post, and be sure to do a thorough proofread of your text before posting it, looking for unnatural or incorrect parts. When I have written a blog in the past in Japanese, I frequently googled combinations of words to verify if they were common before using them. This helped me write much more natural sentences, but it had the disadvantage of being quite tedious and taking out some of the fun out of blog writing.

Another option when you are reading is to take notes whenever you come across an expression that seems useful, and force yourself to use it in the next day or so in your own writing. This can be an effective way of increasing your vocabulary, though it takes a good amount of persistence and willpower to not get lazy and quit after a few days. If you have the time you can write a few example sentences on the spot, though that can interrupt your reading practice.

One other way to help raise your writing and speech to native level is to find one or more role models–native speakers who you can respect and pick up phrases from. I think to a certain extent this automatically happens when speaking, especially when we make friends and talk to them on a frequent basis, but for writing I feel it requires a bit more conscious effort to find and leverage such linguistic role models.

Once in a while, ask a native speaker to give you detailed criticism of your writing so you can have a sanity check to see how close to native level you are. Doing this for everything you write would be way too tedious (for both you and the other person), though there are some tools out there like Lang 8 which can help make this process more efficient (disclaimer: I have not actually used this site but think it is worth experimenting with). Writing in a foreign language for weeks, months, or longer, without having someone double check your work carries the risk of developing certain bad habits that will be hard to break later.

Another thing I am considering getting into is writing fiction short stories in Japanese. I feel this is one of the hardest domains because much of the internet doesn’t contain full texts of proper ‘literature’, so the technique of google for natural sentences isn’t nearly as useful. Also, it is harder to find someone to correct your language since you’ll need a person that is pretty well-read. Finally, the lexicon of words used in literature is much higher than in normal everyday conversation, emails, or chat. The best thing you can do is just read as much as you can in that language, ideally from published authors, and try to remember as much as you can as you read.

At the end of the day, learning to write and speak naturally in a foreign language is essentially about learning to imitate others in an efficient way, and match up thoughts and feelings with the appropriate words. I feel the number one enemy is not the large number of words nor the foreign concepts you need to master, but complacency . The danger is when we realize we’ve reached the level where native speakers actually understand what we are saying (or at least seem to), and we slack off, telling ourselves that we’ve made it. Learning to speak and write such that we can communicate basic ideas is very different from doing so with native-like expressions, and making sure we are aware of the massive gulf between these two things is one of the steps to true fluency.

This reminds me of a book I once read about Zen meditation many years ago, “Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind” . The central theme of this book was that there is something special about people when they start to learn something new: they look at everything with an unbiased, fresh mind, devoid of expectations and thoughts of “I should be pretty good at this since I have this much experience”. Though the book was focused on meditation, I think applying the concept of Beginners Mind to our language studies may have a surprisingly large impact, especially for those that have been studying a few years or longer.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

7 thoughts on “ Short essay: Thoughts on learning to speak and write in a foreign language… naturally ”

HiNative and Lang-8 were designed just for that purpose: to have natives correct your writing. HiNative has a spoken aspect too, and while it is shorter, that makes it easier for everyone. Trying to learn from longer clips is exhausting.

Thanks for letting me know about HiNative, it looks interesting! Maybe I’ll check it out sometime.

Your assessment of higher level language learning is very true. Mimicking native patterns and habits is key to improving your ability. Writing and speaking are also very different, in all languages. In most cases your writing is not going to exactly replicate the way you would speak it, and sometimes writing like you would speak comes out quite strange. As with learning the language in the first place, I think practice, as you suggest, is key. It’s really nice that there are websites to help with your writing, because it can be hard even to get friends to correct your writing, especially if they don’t want to be harsh on you.

Thanks for the comment, glad you agree with that I said (:

Totally agree with what you said. When I read your entry, nuances like 分かる being preferred over 知る came to mind. I have used Lang-8 for years, and I can vouch that it is a very good tool for studying Japanese, if one is hardworking. Since others correct one’s entries, one should correct other people’s entries for a balanced exchange, so it does become time-consuming. However, it is really good because one gets to see a variety of expressions recommended by a variety of people. While this is good for N3-ish learners and above, lower level learners might find it confusing to have so many different options to choose from and may require a non-native to explain the difference to them. But all in all, I definitely recommend Lang-8 🙂

Thanks for the response. Good to know you have gotten so much use out of Lang-8.

Actually I’ve created my own program to help everyone practice writing in Japanese, maybe you’d get some use out of that as well?

If you are interested, check this out:

http://selftaughtjapanese.com/japanese-writing-lab-improve-your-writing-skills/

Hello locksleyu 🙂

Thank you for your recommendation. I have just slaved over a script for a Japanese speech contest, so I’ll take a break from writing for a bit ^^;; (bit.ly/JapSpeech) if you’re interested 🙂

I’ll join the writing lab when I feel up to it 😀

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Currently you have JavaScript disabled. In order to post comments, please make sure JavaScript and Cookies are enabled, and reload the page. Click here for instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your browser.

- Dec 15, 2022

How to Start Writing a Japanese Diary Today

Updated: Aug 26, 2023

Konnichiy’all!

I hope your studying is going well! And if you took the JLPT a few weeks back, I hope you’ve had some nice time to rest and relax and maybe even actually enjoy Japanese again.

Today I’ve got another new study method to introduce. This one is geared towards practicing writing and expressing thoughts in Japanese. A lot of the time we get really caught up in studying all the vocabulary, grammar, and kanji that comes with Japanese, and everything just becomes example sentence after example sentence. We forget to make time to practice thinking for ourselves as well. So, one habit that I highly recommend everyone stacking into their study routine is…

A Japanese language diary!

Now, by diary I don’t mean that you need to write out all your deepest thoughts and feelings and spill your secrets in Japanese. I mean, you can do this. It would certainly be wonderful practice. But rather, I just mean keeping a journal or notebook where you write about your day in Japanese on a consistent basis .

A Simple Format for Your Japanese Diary

Language diary entries don't need to be anything special or lengthy. You can talk about where you went, who you saw, what you did or ate or watched or felt - anything is okay! Short and simple is absolutely fine. I recommend locking the habit down with just a couple sentences a day at first, rather than straining to write an essay each time.

The important part here is the word consistent . As always, our goal here is to build long term language habits that are easy, accessible, and meaningful. We don’t ever want studying to feel like too much of a chore.

Here’s the format that I used at first, and that I’ve also used with my students studying English:

Weather. Sentence 1. Sentence 2.

So, for example:

12月14日(水曜日)

天気は晴れです。今日は朝ごはんにたまごやきを食べました。おいしかったです。

(Tenki wa hare desu. Kyou ha asagohan ni tamagoyaki wo tabemashita. Oishikattadesu.)

(The weather is sunny. Today I ate rolled omelets for breakfast. They were delicious!)

It’s as simple as that. And it’s scalable to any level. When I was first starting out and didn’t know many kanji, vocabulary, or verb tenses, it may have looked like this:

てんきがいいです。きょうはたまごやきをたべました。おいしい!

(Tenki ga ii desu. Kyou ha tamagoyaki wo tabemashita. Oishii!)

(The weather is nice. Today I ate rolled omelets. Delicious!

And at a higher level, it will start to sound more natural:

最近天気が暖かくなってきました。今日の朝ご飯に彼女が卵焼きを作ってくれたんです。美味しくて最高でした♡

(Saikin tenki ga atatakaku natte kimashita. Kyou no asagohan ni kanojo ga tamagoyaki wo tsukutte kuretandesu. Oishikutesaikoudeshita.)

Naturally, as your Japanese knowledge and speed increases, your entries will probably increase in length. It’s exciting to be able to express more complex thoughts! However, even once you’ve started branching into longer entries, you can always come back to this weather + 2 sentences format to maintain the writing habit on a busy day, or when you’re not feeling very motivated. Just like how you can save your Duolingo streak with a single lesson, just a sentence or two means you didn’t miss your writing habit for the day.

6 tips to make the most of your Japanese diary:

1. write in polite japanese.

When I started writing my diary, the teacher who checked my entries had a rule that I had to write in polite language. That meant desu/masu form, all the time. I hated this rule. I wanted to practice casual Japanese too! I didn’t want to sound like a robot.

Oh my god, I am so grateful now. The fact is that no matter what your plans are with Japanese, you are going to need to use polite language a lot. For starters, any interactions that happen with staff at restaurants, izakaya, hotels, stores, etc., should happen in polite language. And yes, there is definitely a foreigner card for not using the correct level of politeness in your speech, but it can still be shocking and make someone come off as rude when that was never the intention. Even if you make Japanese friends or date Japanese people while living in Japan, you’ll start off using polite language with new people - just like you would at home.

Of course, I’m not saying you shouldn’t ever use or practice casual language. But whether you’re interested in traveling, studying, living, or working here, you should be able to speak politely first and foremost. Please don’t be the foreigner who speaks anime Japanese in Japan. In 99% of situations, it’s way more acceptable to speak too politely than it is to speak too casually here, especially if you’re young. So, I recommend practicing expressing your thoughts in polite Japanese, so that when it’s time to convey them to a Japanese person, you won’t accidentally let bad vibes slip off your tongue.

2. Find the frequency and entry length that works for you

I gave a weather + 2 sentences/day recommendation above, but the truth is that I’ve actually used a slightly different format for about two years now. I had Japanese lessons with a volunteer teacher twice a week when I was living in the Kansai region, and my diary was my homework. I work very well with deadlines, so having the twice a week deadline meant I built the habit of writing my diary twice a week. To make up for the lower frequency, I wrote slightly longer entries, about 5-7 sentences per entry. It was really easy to stack the habit of writing my diary entries at lunch before my lesson. So, find the frequency and length that will play to your strengths and fit easily into your schedule.

3. Choose your focus and format

If you want to learn to write Japanese, I definitely recommend a written diary in a notebook or journal. As you build your writing habit, the most important and commonly used kanji for you personally will become muscle memory. There’s a ton of benefit beyond just learning to write as well - your hand is connected to your mind, and you’ll remember the readings and meanings of kanji and words more clearly by writing them down yourself.

That being said, many people these days don’t bother learning to write Japanese . I do have to say, even living in Japan I barely ever need to write in Japanese. Though I can’t speak for working in an actual Japanese company, as far as daily life goes, just knowing how to read and type is definitely enough to get by these days. Japanese people themselves are also forgetting how to write a lot of more complex kanji as we shift to using more and more technology in our lives.

So, if you’d rather only focus on learning how to express your thoughts in Japanese, then a typed diary in a Google document might be the way to go. It’s way easier to access, and therefore do, since most of us have our phones all the time. The choice is up to you and your language learning goals!

4. Don’t write the same thing every day

This is probably common sense for someone learning a language because of internal motivation, but my Japanese students are very guilty of submitting a full week of English diaries that all say “The weather is sunny. Today I ate curry/stew/a hamburger/corn. It was delicious.” Now, they’re probably all really wonderful at saying that their lunch was great, but I’m not sure that the diary homework benefitted them much outside of that.

For best results, mix and match the vocabulary and grammar you know to express lots of different ideas and opinions. It’s more fun this way, and you’ll learn a lot of stuff along the way without having to open a textbook.

5. Read it back to yourself out loud to check for mistakes

This was something I didn’t do for a long time because I had a teacher reading it for me, but I wish I had been doing it all along. Oftentimes when we’re writing fast we forget words, make small mistakes, or throw out something awkward or incorrect, even in our mother tongues. Naturally, it’s going to happen in Japanese too, probably to a greater extent.

More often than you’d expect, you can sense when something’s off just by reading it over one more time. Speaking aloud also lets you know if it sounds off for some reason, such as strange wording or a grammar mistake. (Actually, I’d recommend this strategy for editing any English writing as well, to be honest!)

Beyond this, reading your entries back to yourself provides nice reading practice and review of any of the new words you’ve looked up and learned while writing, as well as rare speaking practice of more than a sentence at a time.

6. If you fall off the horse, just get back on

As with any habit, study or otherwise, sometimes life gets in the way of consistency. To be honest, when I moved and my daily routine changed so much, I stopped writing my diary for a time as well. But even if you miss a day or a week or a month or a year, what’s important with is just picking it up again and getting back on track. Don’t bite off more than you can chew, stick to the weather and 2-sentence structure for as long as you need to, and build (and rebuild) habits at your own pace. I promise the effort pays off over time.

Well, that’s it for your Japanese diary! As always, good luck with your studies and I hope you find this method to be useful!

If you enjoyed this post and don't want to miss the next ones, please make sure to hit the like button and use the box below to subscribe to Konnichiyall! Additionally, any social shares of this post will help so much to grow the community!

読でくれてありがとうございます!

P.S. I’m planning to put together a Japanese diary circle with weekly deadlines to help with motivation. Ideally, I’d like for it to be a space where we can share diary entries, questions, and support each other in the learning process. I’ll be polling soon about frequency and potential platforms to use on my Twitter , so please give me a follow and vote!

Want more Japanese Language Learning content? Here are some of my go-to study methods and tips for learning Japanese on your own!

Where to Start with Self-Studying Japanese: Habit Building

The Secret to Actually Speaking Japanese: Podcasts

How to Fail the JLPT in 5 Steps

- Japanese Language Learning

Recent Posts

The Trick I Used to Read Japanese Faster: Study with Karaoke

How to Learn Japanese Kanji the Fast Way: WaniKani

How to Learn Japanese Fast: Beat the Japanese Memorization Game

Join the Konnichiyall Community

Subscribe to our email list and be the first to know about new posts.

Thanks for submitting!

- Jumps to the header

- Jumps to the menu

- Jumps to the text

Start of Header

The list summarizes "what successful JLPT examinees of each level think they can do in Japanese," based on self-evaluation survey results. It is not a syllabus (question outline) of the JLPT, nor does it guarantee the Japanese-language proficiency of successful examinees. For language proficiency measured by the JLPT and question outline, please refer to " Summary of Linguistic Competence Required for Each Level ." The list can be used as a reference to help examinees and others get an idea of "what successful examinees of a particular level can do in Japanese." ※Please use "PDF for printout" when making hard copies, as the line height of tables varies by computer and character display size.

※Percentages of successful examinees of each level who think they "can do" an item are shown in four ranges. When estimating percentages, the responses of only "successful examinees near the passing line" were used. For details, please refer to " 2.List preparation " at the beginning.

JLPT Can-do Self-Evaluation List

End of Text

- Site Policy

- Privacy Policy

Start Learning Japanese in the next 30 Seconds with a Free Lifetime Account

Learn Japanese - JapanesePod101.com

Skip to content

- Board index Japanese Language - Learn Japanese Learn All About Japanese

SHORT Japanese essay

Moderators: Moderator Team , Admin Team

Post by yamiisan93_509416 » December 12th, 2015 10:24 pm

Re: SHORT Japanese essay

Post by community.japanese » December 21st, 2015 2:35 pm

Return to “Learn All About Japanese”

- General Information

- Learn Japanese Forum Help and Posting Guidelines

- Tech Updates

- Japanese Language - Learn Japanese

- Learn All About Japanese

- Japanese Resources & Reviews

- JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test) - 日本語能力試験

- Practice Japanese - 日本語を練習しましょう

- Japanese Culture

- General Japanese Culture

- Japanese Anime & Manga

- Japanese History & Tradition

- Japanese Food & Entertainment

- Travel Japan - Life in Japan

- Visiting Japan

- Working & Studying in Japan

- Everything Else Japan Related

- JapanesePod101 Listener's Lounge

- Feedback & Support

- Feature Requests

- Japanese Lesson Suggestions

- Technical Support

- Moderator Corner

More From Forbes

Artificial general intelligence or agi: a very short history.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Artificial General Intelligence, AGI concept. AI can learn and solve any human's intellectual tasks.

AGI is the new AI, promoted by tech leaders and AI experts , all promising its imminent arrival, for better or for worse. Anyone frightened by Elon Musk’s warning that “AGI poses a grave threat to humanity, perhaps the greatest existential threat we face today,” should first study the evolution of AGI from science-fiction to real-world fiction.

The term AGI was coined in 2007 when a collection of essays on the subject was published. The book, titled Artificial General intelligence , was co-edited by Ben Goertzel and Cassio Pennachin. In their introduction, they provided a definition:

“AGI is, loosely speaking, AI systems that possess a reasonable degree of self-understanding and autonomous self-control, and have the ability to solve a variety of complex problems in a variety of contexts, and to learn to solve new problems that they didn’t know about at the time of their creation.” The rationale for “christening” AGI for Goertzel and Pennachin was to distinguish it from “run-of-the-mill ‘artificial intelligence’ research,” as AGI is “explicitly focused on engineering general intelligence in the short term.”

In 2007, “run-of-the-mill” research focused on narrow challenges and AI programs of the time could only “generalize within their limited context.” While “work on AGI has gotten a bit of a bad reputation,” according to Goertzel and Pennachin, “AGI appears by all known science to be quite possible. Like nanotechnology, it is ‘merely an engineering problem’, though certainly a very difficult one.”

AGI is considered by Goertzel and Pennachin as only an engineering challenge because “we know that general intelligence is possible, in the sense that humans – particular configurations of atoms – display it. We just need to analyze these atom configurations in detail and replicate them in the computer.”

Best High-Yield Savings Accounts Of 2024

Best 5% interest savings accounts of 2024.

Goertzel and Pennachin seem to contradict themselves when they also assert that the Japanese 5 th generation Computer System project “was doomed by its pure engineering approach, by its lack of an underlying theory of mind.” But maybe there’s no contradiction here because they assume that the mind is also a collection of atoms that can be emulated in a computer by the right engineering approach: “We have several contributions in this book that are heavily based on cognitive psychology and its ideas about how the mind works. These contributions pay greater than zero attention to neuroscience, but they are clearly more mind-focused than brain-focused.”

The brain-focused approach presented in the book is “a neural net based approach, trying to model the behavior of nerve cells in the brain and the emergence of intelligence therefrom. Or one can proceed at a higher level, looking at the general ways that information processing is carried out in the brain, and seeking to emulate these in software.”

This was written, of course, when the real fringe of the AI community—ignored in this 2007 book—were the handful of people (e.g., 2018 Turing Award winners Geoffrey Hinton, Yann LeCun and Joshua Bengio) who in 2007 coined the term “deep learning” to describe their machine learning approach to finding patterns in lots of data using statistical analysis algorithms. These have been called since the 1950s “artificial neural networks,” algorithms that have been presented throughout the years with no empirical evidence as “mimicking the brain.”

In 2007, the people that were the first to discuss various approaches to achieving the newly-termed “AGI” completely ignored the fringe approach to “AI” that in 2012 became the mainstream approach to AI with the successful marriage of GPUs, lots of data, and artificial neural networks. Still, the researchers previously on the fringe of AI and now the kings of the data mountain understood well the branding and marketing power of “AGI” and continued in the exalted tradition of promising the imminent arrival of machines with human-like intelligence (or superintelligence) and the possible extinction of humanity by these possibly malevolent machines.

The key person in the importation of this tradition to the new successful approach to AI was apparently Shane Legg, a co-founder of DeepMind. Legg suggested to Goertzel the term “Artificial General Intelligence” and described to Cade Metz (who quoted Legg in his book Genius Makers ) the general attitude to the subject in the AI community around 2007: “If you talked to anybody about general AI, you would be considered at best eccentric, at worst some kind of delusional, nonscientific character.”

Aspiring to build superintelligence while worrying about what it could do to humanity, Legg joined his colleague Demis Hassabis (they were exploring the connections between the brain and machine learning at UCL) to establish DeepMind. Hassabis told Legg that “they could raise far kore money from venture capitalists than they ever could writing grant proposals as professors,” Metz reports. With AGI as the stated aim of DeepMind, mentioned in the first line of their business plan, “they told anyone who would listen, including potential investors, that this research could be dangerous.”

To get to Peter Thiel, their first investor, Hassabis gave a presentation at the 2010 Singularity Conference, arguing that the best way to build artificial intelligence was to mimic the way the brain worked: “We should be focusing on the algorithmic level of the brain, extracting the kind of representations and algorithms the brain uses to solve the kind of problems we want to solve with AGI.”

There you have it. Using the term “AGI”—with its exciting connotations of both saving and destroying humanity—to get the attention and deep pockets of investors, claiming to replicate the human brain in the computer while pursuing a statistical analysis method that has nothing to do empirically speaking with how the human brain works .

Whether insisting that their approach to AI resembles the biological processes of the human brain (“connectionism”) or that they can replicate the process of human thinking in the computer (“symbolic AI”), the two key approaches to AI since the term was coined in 1955 have banked on the widely accepted notion that “ we are as gods .” This belief in modern man’s ability to conquer all frontiers, even replicate man in the machine, has been based on the centuries-old idea that humans are a “particular configurations of atoms.”

Next in my AGI Washing Series, I will offer a short pre-history of AGI.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

How to write the title of Sakubun, your full name, school and class. Before writing the content of Sakubun, you need to write your full name, your class and the title of Sakubun first. Title: Write in the first line. Leave the first two or three squares blank (from top to bottom). Full name: Write in the last squares in the second line, but you ...

Speculating on the reasons why Japanese students fail to write well-organized paragraphs, we propose that many Japanese students consider English paragraphs to be identical with Japanese danraku. In order to investigate this supposition, this study examines Japanese students' writing — comparing danraku and English paragraph structures. 1. Reply.

生 life, birth. 活 vivid, lively. "Block of meaning" is the best phrase, because one kanji is not necessarily a "word" on its own. You might have to combine one kanji with another in order to make an actual word, and also to express more complex concepts: 生 + 活 = 生活 lifestyle. 食 + 生活 = 食生活 eating habits.

Japanese Essay Phrases: General Explaining. しけんにごうかくするのために、まじめにべんきょうしなきゃ。. Shiken ni goukaku suru no tame ni, majime ni benkyou shinakya. In order to pass the exam, I must study. あしたあめがふるそう。. だから、かさをもってきて。. Ashita ame ga furu sou. Dakara ...

Here's how the 5 vowels sound in Japanese: あ / ア: "ah" as in "latte". い / イ: "ee" as in "bee". う / ウ: "oo" as in "tooth". え / エ: "eh" as in "echo". お / オ: "oh" as in "open". Even when combined with consonants, the sound of the vowel stays the same. Look at these examples: か / カ ...

This article represents the first writing assignment of that program. For this assignment, I'd like to focus on a very common, but important topic: self-introduction, known as 自己紹介 (jiko shoukai) in Japanese. Self-introductions can range widely from formal to casual, and from very short (name only) to much longer.

2. Write a 3-line diary in Japanese. The next method is to write a diary in Japanese. Don't you think you have to write long sentences in your diary? But short sentences are fine. Write a lot of short sentences, until you have three lines. It can be a little tough at first. When writing a diary, you don't have to write "I'm amazing".

A collection of essays by Murakami Haruki who is a best-selling contemporary Japanese writer. Each essay, originally published in a women's magazine "an-an" from 2000 to 2001, is approx. 4-8 pages. No furiganas are provided. (added 4/8/2014) To see a sample text in a new tab, please click on the cover image or the title.

Product Description. $16.00 USD $19.99 USD. A new and revised edition of this book is now available here: How to Write Japanese Essays - 2nd Edition. If you are planning to study at a Japanese University or work at a Japanese company, your Japanese writing skills will need to be at an academic level. This book is a good guide for writing essays ...

(essay paper) Traditionally, Japanese is written from top to bottom and right to left. Start the composition on the Title: 1. Title is on the first line 2. Indent three boxes Name: 1. Family name first 2. Separate the family name and first name by inserting ・(a dot) in the middle of the box 3. Leave one box on the bottom third line.

7 thoughts on " Short essay: Thoughts on learning to speak and write in a foreign language… naturally " Erica May 4, 2016. HiNative and Lang-8 were designed just for that purpose: to have natives correct your writing. HiNative has a spoken aspect too, and while it is shorter, that makes it easier for everyone.

6 tips to make the most of your Japanese diary: 1. Write in polite Japanese. When I started writing my diary, the teacher who checked my entries had a rule that I had to write in polite language. That meant desu/masu form, all the time. I hated this rule. I wanted to practice casual Japanese too!

Tea Ceremony in Japanese Culture. The Beauty of Japanese Gardens. The Art of Japanese Floral Arrangement. Festivals and Matsuri in Japanese Culture. The Code of Bushido and Its Influence on Society. Pop Culture Phenomena of J-Pop and Kawaii. Sushi, Ramen, and Other Culinary Delights of Japan.

Note when writing a paragraph about life in Japan. You can write about life in Japan as an international student. Try to recall what you have experienced, what you have learned, what you did while living in Japan. Then make an outline and develop the detailed content. You can refer to the following outline:

I can write instructions such as how to make meals and how to use machines. 4: I can write reports on fields I am concerned about. 5: I can write letters and e-mails using basic polite Japanese to senior acquaintances (e.g. teachers, etc.). 6: I can write a short speech for my farewell party, etc. 7: I can write statements of purpose for school ...

SHORT Japanese essay. Post December 12th, 2015 10:24 pm. I'm quite new to learning Japanese and yet my teacher asked me to write a rather complicated text so now I'm a bit lost. I've written some short sentences and I'm sure I've made plenty of mistakes. Would be so happy if any of you out there could help me out a bit!

Kay's essay gives good insight into the best times to visit Japan. 5. A Day Trip To Kobe by David Swanson. "When planning a visit to Kobe, consider the fact that the city has been completely rebuilt since 1995, following the great Hanshin earthquake that leveled much of the city.

This video demonstrates "How to say Essay in Japanese"Talk with a native teacher on italki: https://foreignlanguage.center/italkiLearn Japanese with Japanese...

Goertzel and Pennachin seem to contradict themselves when they also assert that the Japanese 5 th generation Computer System project "was doomed by its pure engineering approach, by its lack of ...

Ningen ni totte kazoku to wa soudan aite ni natte kure tari issho ni tanoshime tari mamotte kure tari suru. For each person, family is a counseling partner and a place where we are protected and can enjoy together. こんな家族を私は、大切にしたい。. Konna kazoku wo watashi wa, taisetsu ni shitai.