School of Biological Sciences

University of Manchester

Tutorial – Appendix 2: A Practical Guide to Writing Essays – Level 1

Appendix 2: a practical guide to writing essays.

Writing an essay is a big task that will be easier to manage if you break it down into five main tasks as shown below:

An essay-writing Model in 5 steps

- Analyse the question

What is the topic?

What are the key verbs?

Question the question—brainstorm and probe

What information do you need?

How are you going to find information?

Find the information

Make notes and/or mind maps

- Plan and sort

Arrange information in a logical structure

Plan sections and paragraphs

Introduction and conclusion

- Edit (and proofread)

For sense and logical flow

For grammar and spelling

My Learning Essentials offers a number of online resources and workshops that will help you to, understand the importance of referencing your sources, use appropriate language and style in your writing, write and proofread your essays. For more information visit the writing skills My Learning Essentials pages: http://www.library.manchester.ac.uk/services-and-support/students/support-for-your-studies/my-learning-essentials/

1. Analyse the question

Many students write great essays — but not on the topic they were asked about. First, look at the main idea or topic in the question. What are you going to be writing about? Next, look at the verb in the question — the action word. This verb, or action word, is asking you to do something with the topic.

Here are some common verbs or action words and explanations:

2. Research

Once you have analysed the question, start thinking about what you need to find out. It’s better and more efficient to have a clear focus for your research than to go straight to the library and look through lots of books that may not be relevant.

Start by asking yourself, ‘What do I need to find out?’ Put your ideas down on paper. A mind map is a good way to do this. Useful questions to start focusing your research are: What? Why? When? How? Where? Who?

My Learning Essentials offer a number of online resources and workshops to help you to plan your research. Visit the My Learning Essentials page: http://www.library.manchester.ac.uk/services-and-support/students/support-for-your-studies/my-learning-essentials/workshops-and-online-resources/

3. Plan and sort

First, scan through your source . Find out if there’s any relevant information in what you are reading. If you’re reading a book, look at the contents page, any headings, and the index. Stick a Post-It note on useful pages.

Next, read for detail . Read the text to get the information you want. Start by skimming your eyes over the page to pick our relevant headings, summaries, words. If it’s useful, make notes.

Making notes

There are two rules when you are making notes:

- page reference

- date of publication

- publisher’s name (book)

- place where it was published (book or journal)

- the journal number, volume and date (journal)

- Make brief notes rather than copy text, but if you feel an extract is very valuable put it in quotation marks so that when you write your essay, you’ll know that you have to put it in your own words. Failing to rewrite the text in your own words would be plagiarism.

For more information on plagiarism, refer to the semester 1 section of this handbook, the First Level Handbook, and the My Learning Essentials Plagiarism Resource http://libassets.manchester.ac.uk/mle/avoiding-plagiarism/

Everyone will make notes differently and as it suits them. However, the aim of making notes when you are researching an essay is to use them when you write the essay. It is therefore important that you can:

- Read your notes

- Find their source

- Determine what the topics and main points are on each note (highlight the main ideas, key points or headings).

- Compose your notes so you can move bits of information around later when you have to sort your notes into an essay.

For example:

- Write/type in chunks (one topic for one chunk) with a space between them so you can cut your notes up later, or

- write the main topics or questions you want to answer on separate pieces of paper before you start making notes. As you find relevant information, write it on the appropriate page. (This takes longer as you have to write the source down a number of times, but it does mean you have ordered your notes into headings.)

Sort information into essay plans

You’ve got lots of information now: how do you put it all together to make an essay that makes sense? As there are many ways to sort out a huge heap of clothes (type of clothes, colour, size, fabric…), there are many ways of sorting information. Whichever method you use, you are looking for ways to arrange the information into groups and to order the groups into a logical sequence . You need to play around with your notes until you find a pattern that seems right and will answer the question.

- Find the main points in your notes, put them on a separate page – a mind map is a good way to do this – and see if your main points form any patterns or groups.

- Is there a logical order? Does one thing have to come after another? Do points relate to one another somehow? Think about how you could link the points.

- Using the information above, draw your essay plan. You could draw a picture, a mind map, a flow chart or whatever you want. Or you could build a structure by using bits of card that you can move around.

- Select and put the relevant notes into the appropriate group so you are ready to start writing your first draft.

The essay has four main parts:

- introduction

- references.

People usually write the introduction and conclusion after they have written the main body of the essay, so we have covered the essay components in that order below.

For more information on essay writing visit the My Learning Essentials web pages:

http://www.library.manchester.ac.uk/services-and-support/students/support-for-your-studies/my-learning-essentials/workshops-and-online-resources/?level=3&level1Link=3&level2Links=writing

Structure . The main body should have a clear structure. Depending on the length of the essay, you may have just a series of paragraphs, or sections with headings, or possibly even subsections. In the latter case, make sure that the hierarchy of headings is obvious so that the reader doesn’t get lost.

Flow . The main body of the essay answers the question and flows logically from one key point to another (each point needs to be backed up by evidence [experiments, research, texts, interviews, etc …] that must be referenced). You should normally write one main idea per paragraph and the main ideas in your essay should be linked or ‘signposted’. Signposts show readers where they are going, so they don’t get lost. This lets the reader know how you are going to tackle the idea, or how one idea is linked with the one before it or after it.

Some signpost words and phrases are:

- ‘These changes . . . “

- ‘Such developments

- ‘This

- ‘In the first few paragraphs . . . “

- ‘I will look in turn at. . . ‘

- ‘However, . . . “

- ‘Similarly’

- ‘But’.

Figures: purpose . You should try to include tables, diagrams, and perhaps photographs in your essay. Tables are valuable for summarising information, and are most likely to impress if they show the results of relevant experimental data. Diagrams enable the reader to visualise things, replacing the need for lengthy descriptions. Photographs must be selected with care, to show something meaningful. Nobody will be impressed by a picture of a giraffe – we all know what one looks like, so the picture would be mere decoration. But a detailed picture of a giraffe’s markings might be useful if it illustrates a key point.

Figures: labelling, legends and acknowledgment . Whenever you use a table, diagram or image in your essay you must:

- cite the source

- write a legend (a small box of text that describes the content of the figure).

- make sure that the legend and explanation are adapted to your purpose.

For example: Figure 1. The pathway of synthesis of the amino acid alanine, showing… From Bloggs (1989). [When using a figure originally produced by someone else, never use the original legend, because it is likely to have a different Figure number and to have information that is not relevant for your purposes. Also, make sure that you explain any abbreviations or other symbols that your reader needs to know about the Figure, including details of different colours if they are used to highlight certain aspects of the Figure].

Checklist for the main body of text

- Does your text have a clear structure?

- Does the text follow a logical sequence so that the argument flows?

- Does your text have both breadth and depth – i.e. general coverage of the major issues with in-depth treatment of particularly important points?

- Does your text include some illustrative experimental results?

- Have you chosen the diagrams or photographs carefully to provide information and understanding, or are the illustrations merely decorative?

- Are your figures acknowledged properly? Did you label them and include legend and explanation?

Introduction

The introduction comes at the start of the essay and sets the scene for the reader. It usually defines clearly the subject you will address (e.g. the adaptations of organisms to cold environments), how you will address this subject (e.g. by using examples drawn principally from the Arctic zone) and what you will show or argue (e.g. that all types of organism, from microbes through to mammals, have specific adaptations that fit them for life in cold environments). The length of an introduction depends on the length of your essay, but is usually between 50 to 200 words.

Remember that reading the introduction constitutes the first impression on your reader (i.e. your assessor). Therefore, it should be the last section that you revise at the editing stage, making sure that it leads the reader clearly into the details of the subject you have covered and that it is completely free of typos and spelling mistakes.

Check-list for the Introduction

- Does your introduction start logically by telling the reader what the essay is about – for example, the various adaptations to habitat in the bear family?

- Does your introduction outline how you will address this topic – for example, by an overview of the habitats of bears, followed by in-depth treatment of some specific adaptations?

- Is it free of typos and spelling mistakes?

Conclusion

An essay needs a conclusion. Like the introduction, this need not be long: 50 to 200 words is sufficient, depending on the length of the essay. It should draw the information together and, ideally, place it in a broader context by personalising the findings, stating an opinion or supporting a further direction which may follow on from the topic. The conclusion should not introduce facts in addition to those in the main body.

Check-list for the Conclusion

- Does your conclusion sum up what was said in the main body?

- If the title of the essay was a question, did you give a clear answer in the conclusion?

- Does your conclusion state your personal opinion on the topic or its future development or further work that needs to be done? Does it show that you are thinking further?

In all scientific writing you are expected to cite your main sources of information. Scientific journals have their own preferred (usually obligatory) method of doing this. The piece of text below shows how you can cite work in an essay, dissertation or thesis. Then you supply an alphabetical list of references at the end of the essay. The Harvard style of referencing adopted at the University of Manchester will be covered in the Writing and Referencing Skills unit in semester 2. For more information refer to the Referencing Guide from the University Library (http://subjects.library.manchester.ac.uk/referencing/referencing-harvard).

Citations in the text

Jones and Smith (1999) showed that the ribosomal RNA of fungi differs from that of slime moulds. This challenged the previous assumption that slime moulds are part of the fungal kingdom (Toby and Dean, 1987). However, according to Bloggs et al . (1999) the slime moulds can still be accommodated in the fungal kingdom for convenience. Slime moulds are considered part of the Eucarya domain by Todar (2012).

Reference list at the end of the essay:

List the references in alphabetical order and if you have several publications written by the same author(s) in the same year, add a letter (a,b,c…) after the year to distinguish between them.

Bloggs, A.E., Biggles, N.H. and Bow, R.T. (1999). The Slime Moulds . 2 nd edn. London and New York: Academic Press.

[ Guidance: this reference is to a book. We give the names of all authors, the publication date, title, name of publisher and place of publication. Note that we referred to Bloggs et al .(1999) in the text. The term “ et al .” is an abbreviation of the Latin et alia (meaning “and others”). Note also that within the text “Bloggs et al .” is part of a sentence, so we put only the date in parentheses for the citation in the text. If you wish to cite the entire book, then no page numbers are listed. To cite a specific portion of a book, page numbers are added following the book title in the reference list (see Toby and Dean below).

Todar K. (2012) Overview Of Bacteriology. Available at: http://textbookofbacteriology.net, [Accessed 15 November 2013].

Jones, B.B. and Smith, J.O.E. (1999). Ribosomal RNA of slime moulds, Journal of Ribosomal RNA 12, 33-38.

Toby F.S. and Dean P.L. (1987). Slime moulds are part of the fungal kingdom, in Edwards A.E. and Kane Y. (eds.) The Fungal Kingdom. Luton: Osbert Publishing Co., pp. 154-180 .

EndNote: This is an electronic system for storing and retrieving references. It is very powerful and simple to use, but you must always check that the output is consistent with the instructions given in this section. EndNote will be covered (and assessed) in the Writing and Referencing Skills online unit in Semester 2 to help you research and reference your written work.

Visit the My Learning Essentials online resource for a guide to using EndNote: https://www.escholar.manchester.ac.uk/learning-objects/mle/endnote-guide/ (we recommend EndNote online if you wish to use your own computer).

Note that journals have their own house style so there will be minor differences between them, particularly in their use of punctuation, but all reference lists for the same journal will be in the same format.

First Draft

When you write your first draft, keep two things in mind:

- Length: you may lose marks if your essay is too long. Ensure therefore that your essay is within the page limit that has been set.

- Expression: don’t worry about such matters as punctuation, spelling or grammar at this stage. You can get this right at the editing stage. If you put too much time into getting these things right at the drafting stage, you will have less time to spend on thinking about the content, and you will be less willing to change it when you edit for sense and flow at the editing stage.

Writing style

The style of your essay should fit the task or the questions asked and be targeted to your reader. Just as you are careful to use the correct tone of voice and language in different situations so you must take care with your writing. Generally writing should be:

- Make sure that you write exactly what you mean in a simple way.

- Write briefly and keep to the point. Use short sentences. Make sure that the meaning of your sentences is obvious.

- Check that you would feel comfortable reading your essay if you were actually the reader.

- Make sure that you have included everything of importance. Take care to explain or define any abbreviations or specialised jargon in full before using a shortened version later. Do not use slang, colloquialisms or cliches in formal written work.

When you are editing your essay, you will need to bear in mind a number of things. The best way to do this, without forgetting something, is to edit in ‘layers’, using a check-list to make sure you have not forgotten anything.

Check-list for Style

- Tone – is it right for the purpose and the receiver?

- Clarity – is it simple, clear and easy to understand?

- Complete – have you included everything of importance?

Check-list for Sense

- Does your essay make sense?

- Does it flow logically?

- Have you got all the main points in?

- Are there bits of information that aren’t useful and need to be deleted?

- Are your main ideas in paragraphs?

- Are the paragraphs linked to one another so that the essay flows rather than jumps from one thing to another?

- Is the essay within the page limit?

Check-list for Proofreading

- Are the punctuation, grammar, spelling and format correct?

- If you have written your essay on a word-processor, run the spell check over it.

- Have you referenced all quotes and names correctly?

- Is the essay written in the correct format? (one and a half line spacing, margins at least 2.5cm all around the text, minimum font size 10 point).

School Writer in Residence

The School has three ‘Writers in Residence’ who are funded by The Royal Literary Fund.

Susan Barker – Monday and Friday

Tania Hershman – Tuesday

Katherine Clements – Wednesday and Thursday

The Writers in Residence are based in the Simon Building. Please see the BIOL10000 Blackboard site for further information about the writers’ expertise and instructions for appointment booking.

- ← Tutorial – Appendix 5: A practical guide to writing essays – Level 2

- Tutorial Guide – Employability Skills P2 – Level 2 →

Writing a strong scientific paper in medicine and the biomedical sciences: a checklist and recommendations for early career researchers

- Open access

- Published: 28 July 2021

- Volume 72 , pages 395–407, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Payam Behzadi 1 &

- Márió Gajdács ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1270-0365 2 , 3

15k Accesses

51 Citations

407 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Scientific writing is an important skill in both academia and clinical practice. The skills for writing a strong scientific paper are necessary for researchers (comprising academic staff and health-care professionals). The process of a scientific research will be completed by reporting the obtained results in the form of a strong scholarly publication. Therefore, an insufficiency in scientific writing skills may lead to consequential rejections. This feature results in undesirable impact for their academic careers, promotions and credits. Although there are different types of papers, the original article is normally the outcome of experimental/epidemiological research. On the one hand, scientific writing is part of the curricula for many medical programs. On the other hand, not every physician may have adequate knowledge on formulating research results for publication adequately. Hence, the present review aimed to introduce the details of creating a strong original article for publication (especially for novice or early career researchers).

Similar content being viewed by others

A Practical Guide to Writing (and Understanding) a Scientific Paper: Clinical Studies

Writing a Scientific Article

A brief guide to the science and art of writing manuscripts in biomedicine

Diego A. Forero, Sandra Lopez-Leon & George Perry

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The writing and editing of scientific papers should be done in parallel with the collection and analysis of epidemiological data or during the performance of laboratory experiments, as it is an integral step of practical research. Indeed, a scholar paper is the figurative product of scientific investigations (Behzadi and Behzadi 2011 ; Singh and Mayer 2014 ). Moreover, the publication of scholarly papers is important from the standpoint of providing relevant information—both locally and internationally—that may influence clinical practice, while in academia, national and international academic metrics (in which the number and quality of papers determine the score and rank of the scientists) are relevant to fulfill employment criteria and to apply for scientific grants (Grech and Cuschieri 2018 ; Singer and Hollander 2009 ). Thus, scientific writing and the publication of quality peer-reviewed papers in prestigious academic journals are an important challenge for medical professionals and biomedical scientists (Ahlstrom 2017 ). Writing a strong scholarly paper is a multi-procedure task, which may be achieved in a right manner by using a balanced and well-designed framework or blueprint (Gemayel 2016 ; Tóth et al. 2020 ). All in all, time needs to be spent of writing a well-designed and thoughtful scientific proposal to support the research, which will subsequently end in the publication of a paper in a prestigious, peer-reviewed, indexed and scholarly journal with an impact factor (IF). A well-designed scientific project encompasses well-supported and strong hypotheses and up-to-date methodology, which may lead to the collection of remarkable (and reproducible!) data. When a study is based on a strong hypothesis, suitable methodology and our studies result in usable data, the next step is the analysis and interpretation of the said data to present a valuable conclusion at the end of our studies. These criteria give you an influent confidence to prepare a robust and prestigious scholarly paper (Ahlstrom 2017 ; Behzadi 2021 ; Kallet 2004 ; Stenson et al. 2019 ). The aim of this review is to highlight all the necessary details for publication of a strong scientific writing of original article, which may especially be useful for novice or early career researchers.

Approaches for writing and formatting manuscripts before submission

In the presence of effective and appropriate items for writing a strong scientific paper, the author must know the key points and the main core of the study. Thus, preparing a blueprint for the paper will be much easier. The blueprint enables you to draft your work in a logical order (Gemayel 2016 ). In this regard, employment of a mass of charge, free or pay-per-use online and offline software tools can be particularly useful (Gemayel 2016 ; Behzadi and Gajdács 2020 ; Behzadi et al. 2021 ; Ebrahim 2018 ; Issakhanian and Behzadi 2019 ; O'Connor and Holmquist 2009 ; Petkau et al. 2012 ; Singh and Mayer 2014 ; Tomasello et al. 2020 ). Today, there are a wide range of diverse software tools which can be used for design and organization of different parts of your manuscript in the correct form and order. Although traditionally, many scientist do not use these softwares to help formulate their paper and deliver their message in the manuscript, they can indeed facilitate some stages of the manuscript preparation process. Some of these online and offline software facilities are shown in Table 1 .

The first step of writing any scientific manuscript is the writing of the first draft. When writing the first draft, the authors do not need to push themselves to write it in it’s determined order (Behzadi and Gajdács 2020 ; Gemayel 2016 ); however, the finalized manuscript should be organized and structured, according to the publisher’s expectations (Berman et al. 2000 ; Behzadi et al. 2016 ). Based on the contents of the manuscripts, there are different types of papers including original articles, review articles, systematic reviews, short communications, case reports, comments and letters to the editor (Behzadi and Gajdács 2020 ; Gemayel 2016 ), but the present paper will only focus on the original articles structured in the IMRAD (Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion) structure. Materials and methods, results, discussion or introduction sections are all suitable target sections to begin writing the primary draft of the manuscript, although in most cases, the methods section is the one written first, as authors already have a clear sense and grasp on the methodologies utilized during their studies (Ebrahim 2018 ). The final sections of IMRAD papers which should be completed are the abstract (which is basically the mini-version of the paper) and conclusion (Liumbruno et al. 2013 ; Paróczai et al. 2021 ; Ranjbar et al. 2016 ). The authors should be aware that the final draft of the manuscript should clearly express: the reason of performing the study, the individuality (novelty and uniqueness) of the work, the methodology of the study, the specific outcomes examined in this work, the importance, meaning and worth of the study. The lack of any of the items in the manuscript will usually lead to the direct rejection of the manuscript from the journals. During the composition of the manuscript (which corresponds to any and all sections of the IMRAD), some basics of scientific writing should be taken into consideration: scientific language is characterized by short, crisp sentences, as the goal of the publication is to deliver the main message concisely and without confusion. It is a common misconception that scientific writing needs to be “colorful” and “artistic,” which may have the opposite effect on the clarity of the message. As the main goal of publishing is to deliver the message (i.e., the results) of our study, it is preferred that scientific or technical terms (once defined) are used uniformly, with avoiding synonyms. If young scientists have linguistic difficulties (i.e., English is not their first language), it is desirable to seek the help of professional proofreading services to ensure the correct grammar use and clarity. Traditionally, the passive voice was expected to be used in scientific communication, which was intended to strengthen the sense of generalization and universality of research; however, nowadays the active voice is preferred (symbolizing that authors take ownership and accountability of their work) and sentences in passive voice should take up < 10% of the paper (Berman et al. 2000 ; Behzadi et al. 2016 ).

Every scientist should be able to present and discuss their results in their own words, without copy–pasting sentences from other scientists or without referring to the work of others, if it was used in our paper. If an author copies or represents another authors’ intellectual property or words as their own (accidentally or more commonly on purpose) is called plagiarism. Scientific journals use plagiarism checker softwares to cross-check the level of similarity between the submitted works and scientific papers or other materials already published; over a certain threshold of similarity, journals take action to address this issue. Plagiarism is highly unethical and frowned upon in the scientific community, and it is strictly forbidden by all relevant scientific publishers, and if one is caught with plagiarism, the scientific paper is usually rejected immediately (if this occurs during the submission process) or is retracted. There are some freely available online software tools (e.g., iThenticate® ( http://www.ithenticate.com/ ) and SMALL SEO TOOLS ( https://smallseotoolz.net/plagiarism-checker ) for authors to screen their works for similarities with other sources; nevertheless, it is also unethical to use these tools to determine the “acceptable” level of similarity (i.e., cheating) before submitting a paper.

The structure of an IMRAD article includes the title, author’s(s’) name(s), author’s(s’) affiliation(s), author’s(s’) ORCID iD(s) ( https://orcid.org/ ), abstract, keywords, introduction, methods (or materials and methods), results, discussion, conclusion, acknowledgements, conflict of interest and references (Behzadi and Behzadi 2011 ; Singh and Mayer 2014 ). The acronym of ORCID (with a hard pronunciation of C ( https://orcid.org/blog/2013/01/07/how-should-orcid-be-pronounced )) (abbreviation of Open Researcher & Contributor ID) is considered as unique international identifier for researchers (Haak et al. 2012 ; Hoogenboom and Manske 2012 ). The ORCID iD is composed of 16 digits and introduced in the format of https URI ( https://support.orcid.org/hc/en-us/articles/360006897674 ). It is recommended for the authors to register their ORCID iD. The ORCID is important for manuscript submissions, manuscript citations, looking at the works of other researchers among other things (Haak et al. 2012 ; Hoogenboom and Manske 2012 ).

The contents of the IMRAD-structured manuscripts

Although the IMRAD format seems to be a cul-de-sac structure, it can be a suitable mold for both beginners and professional writers and authors. Each manuscript should contain a title page which includes the main and running (shortened) titles, authors’ names, authors’ affiliations (such as research place, e-mail, and academic degree), authors’ ORCID iDs, fund and financial supports (if any), conflicts of interest, corresponding author’s(s’) information, manuscript’s word count and number of figures, tables and graphs (Behzadi and Gajdács 2020 ).

As the title is the first section of your paper which is seen by the readers, it is important for the authors to take time on appropriately formulating it. The nature of title may attract or dismiss the readers (Tullu and Karande 2017 ). In this regard, a title should be the mirror of the paper’s content; hence, a proper title should be attractive, tempting, specific, relevant, simple, readable, clear, brief, concise and comprehensive. Avoid jargons, acronyms, opinions and the introduction of bias . Short and single-sentenced titles have a “magic power” on the readers. Additionally, the use of important and influent keywords could affect the readers and could be easy searchable by the search engines (Cuschieri et al. 2019 ). This can help to increase the citation of a paper. Due to this fact, it is recommended to consider a number of titles for your manuscript and finally select the most appropriate one, which reflects the contents of the paper the best. The number of titles’ and running titles’ characters is limited in a wide range of journals (Cuschieri et al. 2019 ).

The abstract is the vitrine of a manuscript, which should be sequential, arranged, structured and summarized with great effort and special care. This section is the second most important part of a manuscript after title (Behzadi and Gajdács 2020 ). The abstract should be written very carefully, deliberately and comprehensively in perfect English, because a well-written abstract invites the readers (the editors, reviewers, and readers who may cite the paper in the future) to read the paper entirely from A to Z and a rough one discourages readers (the editors and reviewers) from even handling the manuscript (Cuschieri et al. 2019 ). Whether we like it or not, the abstract is the only part of the manuscript that will be read for the most part; thus, the authors should make an effort to show the impressiveness and quality of the paper in this section.

The abstract as an independent structured section of a manuscript stands alone and is the appetizer of your work (Jirge 2017 ). So as mentioned, this part of paper should be written accurately, briefly, clearly, and to be facile and informative. For this section, the word count is often limited (150 to 250/300 words) and includes a format of introduction/background/, aim/goal/objective, methods, results and conclusions. The introduction or background refers to primary observations and the importance of the work, goal/aim/objective should represent the hypothesis of the study (i.e., why did you do what you did?), the methods should cover the experimental procedures (how did you do what you did?), the results should consider the significant and original findings, and finally, the clear message should be reported as the conclusion. It is recommended to use verbs in third person (unless specified by the Journal’s instructions). Moreover, the verbs depicting the facts which already have been recognized should be used in present tense while those verbs describing the outcomes gained by the current work should be used in past tense. For beginners in scientific publishing, it is a common mistake to start the writing of the manuscript with the abstract (which—in fact—should be the finalizing step, after the full text of the paper has already been finished and revised). In fact, abstract ideally is the copy-pasted version of the main messages of the manuscript, until the word limit (defined by the journal) has been reached. Another common mistake by inexperienced authors is forgetting to include/integrate changes in the abstract to reflect the amendments made in the bulk text of the paper. All in all, even a paper with very good contents and significant results may could be rejected because of a poor and weak abstract (Behzadi and Gajdács 2020 ).

Keywords are the key point words and terms of the manuscript which come right after abstract section. The keywords are used for searching papers in the related fields by internet search engines. It is recommended to employ 3 to 10 keywords in this section. The keywords should be selected from the MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) service, NCBI ( https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/ ). An appropriate title should involve the most number of keywords (Behzadi and Gajdács 2020 ; Jirge 2017 ).

Introduction section should be framed up to four paragraphs (up to 15% of the paper’s content). This section should be progressed gradually from general to specific information and gaps (in a funnel-formed fashion). In another words, the current condition of the problem and the previous studies should be briefly presented in the first paragraph. More explanation should be brought in discussion section, where the results of the paper should be discussed in light of the other findings in the literature (Ahlstrom 2017 ; Behzadi 2021 ). In this regard, the original articles and some key references should be cited to have a clarified description. The second paragraph should clarify the lack of knowledge regarding the problem at present, the current status of the scientific issue and explain shortly the necessity and the importance of the present investigation. Subsequently, the relevance of this work should be described to fill the current gaps relating to the problem. The questions (hypothesis/purpose) of the study comprising “Why did you do?/What did you do?/So What?” should be clarified as the main goal in the last paragraph (Ahlstrom 2017 ; Behzadi 2021 ; Burian et al. 2010 ; Lilleyman 1995 ; Tahaei et al. 2021 ). A concise and focused introduction lets the readers to have an influent understanding and evaluation for the performance of the study. The importance of the work presented should never be exaggerated, if the readers feel that they have been misled in some form that may damage the credibility of the authors’ reputation. It is recommended to use standard abbreviations in this section by writing the complete word, expression or phrase for the first time and mentioning the related abbreviation within parenthesis in this section. Obviously, the abbreviations will be used in the following sentences throughout the manuscript. The authors should also adhere to international conventions related to writing certain concepts, e.g., taxonomic names or chemical formulas. In brief, the introduction section contains four key points including: previous studies, importance of the subject, the presence of serious gap(s) in current knowledge regarding the subject, the hypothesis of the work (Ahlstrom 2017 ; Behzadi 2021 ; Lilleyman 1995 ; Tahaei et al. 2021 ). Previously, it was recommended by majority of journals to use verbs in past tense and their passive forms; however, this shows a changing trend, as more and more journals recommend the use of the active voice.

Materials and methods

As the materials and methods section constitutes the skeleton of a paper (being indicative of the quality of the data), this section is known as the keystone of the research. A poor, flawed or incorrect methodology may result in the direct rejection of manuscripts, especially in high IF journals, because it cannot link the introduction section into the results section (Haralambides 2018 ; Meo 2018 ). In other words, the methods are used to test the study’s hypothesis and the readers judge the validity of a research by the released information in this section. This part of manuscript belongs to specialists and researchers; thus, the application of subheadings in a determined and relevant manner will support the readers to follow information in a right order at the earliest. The presentation of the methodologies in a correct and logical order in this section clarifies the direction of the methods used, which can be useful for those who want to replicate these procedures (Haralambides 2018 ; Juhász et al. 2021 ; Meo 2018 ). An effective, accurate, comprehensive and sufficient description guarantees the clarity and transparency of the work and satisfies the skeptical reviewers and readers regarding the basis of the research. The following questions should be answered in this section: “What was done?” and “How was it done?” and “Why was it done?”

The cornerstones of the methods section including defining the type of study, materials (e.g., concentration, dose, generic and manufacturer names of chemicals, antibiotics), participants (e.g., humans, animals, microorganisms), demographic data (e.g., age, gender, race, time, duration, place), the need for and the existence of an ethical approval or waiver (in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its revisions) for humans and animals, experimental designs (e.g., sampling methods, time and duration of the study, place), protocols, procedures, rationale, criteria, devices/tools/techniques (together with their manufacturers and country of origin), calibration plots, measurement parameters, calculations, statistical methods, tests and analyses, statistical software tools and version among many other things should be described here in methods section (Haralambides 2016 ; Stájer et al. 2020 ). If the details of protocols make this section extremely long, mention them in brief and cite the related papers (if they are already published). If the applied protocol was modified by the researcher, the protocol should be mentioned as modified protocol with the related address. Moreover, it is recommended to use flow charts (preferably standard flow charts) and tables to shorten this section, because “a picture paints a thousand words” (Ahlstrom 2017 ; Behzadi 2021 ; Lilleyman 1995 ; Tahaei et al. 2021 ).

The used online guidelines in accordance with the type of study should be mentioned in the methods section. In this regard, some of these online check lists, including the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statement ( http://www.consort-statement.org/ ) (to improve the reporting randomized trials), the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement ( http://www.prisma-statement.org/ ) (to improve the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses), the STARD (Standards for Reporting Diagnostic accuracy studies) statement ( http://www.equator-network.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/STARD-2015-checklist.pdf ) (to improve the reporting of diagnostic accuracy studies), the STORBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology) statement ( https://www.strobe-statement.org/index.php?id=strobe-home ) (to improve the reporting of observational studies in Epidemiology), should be mentioned and highlighted in medical articles. Normally, the methods section begins with mentioning of exclusion (depicting safe selection) and inclusion (depicting no bias has happened) criteria (regarding the populations studied) and continues by the description of procedures and data collection. This section usually ends by the description of statistical data analyses. As mentioned in a previous section, older recommendations in “Instructions for authors” suggested the use of verbs in past tense, in 3rd person and passive forms, whereas novel guidelines suggest more text written in the active voice (Ahlstrom 2017 ; Behzadi 2021 ; Lilleyman 1995 ; Tahaei et al. 2021 ).

The results including negative and positive outcomes should be reported clearly in this section with no interpretation (Audisio et al. 2009 ; Behzadi et al. 2013 ). The most original information of an IMRAD paper originates from the results section. Indeed, the reported findings are the main core of the study which answers to the research question (hypothesis) “what was found?” The results section should answer all points brought up in the methods section. Categorization of findings by subheadings from the major to minor results, chronologically or by any logical order, facilitates readers to comprehend the results in an effective and influent manner (Ahlstrom 2017 ; Behzadi 2021 ; Lilleyman 1995 ; Tahaei et al. 2021 ).

Representing the motive of experiments, the related experimental setups, and the gained outcomes supports the quality and clarity of your results, because these components create logical and influent communications between obtained data, observations and measurements. The results section should represent all types of data (major to minor), variables (dependent and independent), variables effects and even accidental findings. The statistical analyses should be represented at the end of results section. The statistical significance should be represented by an exact amount of p value ( p < 0.05 is usually recognized and set as the threshold for statistical significance, while p > 0.05 depicts no statistical significance). Moreover, the mentioning of the 95% confidence intervals and related statistical parameters is also needed, especially in epidemiological studies (Mišak et al. 2005 ).

It is recommended to use tables, figures, graphs and charts in this section to give an influent representation of results to the readers. Using well-structured tables deeply impresses the readers. Usually the limitation of the number of figures, graphs, tables and charts is represented in the section of instructions for authors of the journal. Remember that well-designed tables and figures act as clean mirrors which transfer a clear and sharp illustration of your work and your efforts in preparing the manuscript. Thus, a well-designed graph, table, charts or figure should be understood easily; in other words, they should be represented as self-explanatory compartments. Avoid repeating the represented data in figures, tables, charts and graphs within the text. Citing figures, graphs, charts and tables in right positions within the text increases the impact and quality of your manuscript (Ahlstrom 2017 ; Behzadi 2021 ; Lilleyman 1995 ; Tahaei et al. 2021 ). Showing the highest and lowest amounts in tables by bolding or highlighting them is very effective. Normally, the legends are placed under graphs and figures and above the tables. It is recommended to begin the figure legends with conclusion and finish it by important technical key points.

Discussion and conclusion

This section represents the interpretations of results. In other words, discussion describes what these results do mean by the help of mechanistic interpretations of causes and effects. This argument should be achieved sharp and strong in a logical manner (Gajdács 2020 ; Rasko et al. 2016 ). The interpretations should be supported by relevant references and evidences. Usually, the first paragraph of discussion involves the key points of results. The represented data in results section should not be repeated within the discussion section. Magnification and exaggeration of data should never occur! “A good wine needs no bush.” Care about the quality of discussion section, because this part of the manuscript is determinative item for the acceptance of the paper (Ahlstrom 2017 ; Behzadi 2021 ).

Avoid representing new data in discussion, which were not mentioned in the results section. The following paragraphs should represent the novelty, differences and/or similarities of the obtained findings. Unusual and findings not predicted should be highlighted (Gajdács 2020 ; Rasko et al. 2016 ). It is important to interpret the obtained results by the strong references and evidences. Remember that citation of strong and relevant references enforces your evaluations and increases the quality of your points of view (Mack 2018 ; Shakeel et al. 2021 ). The probable weaknesses or strengths of the project should be discussed. This critical view of the results supports the discussion of the manuscript. The discussion section is finished by the final paragraph of conclusion. A critical paragraph in which the potential significance of obtained findings should be represented in brief (Ahlstrom 2017 ; Behzadi 2021 ). The bring/take-home message of the study in conclusion section should be highlighted. For writing a conclusion, it is recommended to use non-technical language in perfect English as it should be done in abstract section (Alexandrov 2004 ). It is suggested to use verbs in present tense and passive forms, if not otherwise mandated by the journal’s instructions. In accordance with policy of journals, the conclusion section could be the last part of discussion or presented within a separate section after discussion section (Ahlstrom 2017 ; Behzadi 2021 ).

Acknowledgements

This section is placed right after discussion and/or conclusion section. The unsaid contributors with pale activities who cannot be recognized as the manuscripts’ authors should be mentioned in acknowledgement section. Financial sponsors, coordinators, colleagues, laboratory staff and technical supporters, scientific writing proof readers, institutions and organizations should be appreciated in this section. The names listed in acknowledgements section will be indexed by some databases like US National Library Medicine (NLM) ( https://www.nlm.nih.gov/ ) (Ahlstrom 2017 ).

Conflict of interest

If the authors have any concerns regarding moral or financial interests, they should declare it unambiguously, because the related interests may lead to biases and suspicions of misconducts (Ahlstrom 2017 ; Behzadi 2021 ; Lilleyman 1995 ; Tahaei et al. 2021 ). This section usually comes right after acknowledgements and before references.

Application of relevant and pertinent references supports the manuscript’s scientific documentary. Moreover, utilization of related references with high citation helps the quality of the manuscript. For searching references, it is recommended to use search engines like Google Scholar ( https://scholar.google.com/ ), databases such as MEDLINE ( https://www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/medline.html ) and NCBI ( https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ ) and Web sites including SCOPUS ( https://www.scopus.com/ ), etc.; in this regard, the keywords are used for a successful and effective search. Each journal has its own bibliographic system; hence, it is recommended to use reference management software tools, e.g., EndNote®. The most common bibliographic styles are APA American Psychological Association, Harvard and Vancouver. Nevertheless, the authors should aware of retracted articles and making sure not to use them as references (Ahlstrom 2017 ; Behzadi 2021 ; Lilleyman 1995 ; Tahaei et al. 2021 ). Depending on the journal, there are different limitations for the number of references. It is recommended to read carefully the instructions for authors section of the journal.

Conclusions for future biology

From the societal standpoint, the publication of scientific results may lead to important advances in technology and innovation. In medicine, patient care—and the biomedical sciences in general—the publication of scientific research may also lead to substantial benefits to advancing the medical practice, as evidence-based medicine (EBM) is based on the available scientific data at the present time. Additionally, academic institutions and many academic centers require young medical professionals to be active in the scientific scene for promotions and many employment prospects. Although scientific writing is part of the curricula for many medical programs, not every physician may have adequate knowledge on formulating research results for publication adequately. The present review aimed to briefly and concisely summarize the details of creating a favorable original article to aid early career researchers in the submission to peer-reviewed journal and subsequent publication. Although not all concepts have been discussed in detail, the paper allows for current and future authors to grasp the basic ideas regarding scientific writing and the authors hope to encourage everyone to take the “leap of faith” into scientific research in medicine and to submit their first article to international journals.

Data accessibility

Not applicable.

Ahlstrom D (2017) How to publish in academic journals: writing a strong and organized introduction section. J East Eur Cent Asian Res 4(2):1–9

Google Scholar

Alexandrov AV (2004) How to write a research paper. Cerebrovasc Dis 18(2):135–138

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Audisio RA, Stahel RA, Aapro MS, Costa A, Pandey M, Pavlidis N (2009) Successful publishing: how to get your paper accepted. Surg Oncol 18(4):350–356

Behzadi P (2021) Peer review publication skills matter for academicians. Iran J Pathol 16(1):95–96

Behzadi P, Behzadi E (2011) A new aspect on how to write an original article, 1st edn. Persian Science & Research Publisher, Tehran

Behzadi P, Gajdács M (2020) Dos and don’ts of a successfully peer-reviewed publication: from A-Z. Eur J Microbiol Immun 10:125–130

Article Google Scholar

Behzadi E, Behzadi P, Ranjbar R (2013) Abc’s of writing scientific paper. Infectioro 33(1):6–7

Behzadi P, Najafi A, Behzadi E, Ranjbar R (2016) Microarray long oligo probe designing for Escherichia coli: an in-silico DNA marker extraction. Cent Eur J Urol 69(1):105–111

CAS Google Scholar

Behzadi P, García-Perdomo HA, Karpiński TA (2021) Toll-like receptors: general molecular and structural biology. J Immunol Res 2021:e9914854

Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE (2000) The protein data bank. Nucl Acids Res 28(1):235–242

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Burian K, Endresz V, Deak J, Kormanyos Z, Pal A, Nelson D, Virok DP (2010) Transcriptome analysis indicates an enhanced activation of adaptive and innate immunity by chlamydia-infected murine epithelial cells treated with interferon γ. J Infect Dis 202:1405–1414

Cuschieri S, Grech V, Savona-Ventura C (2019) WASP (write a scientific paper): structuring a scientific paper. Early Human Dev 128:114–117

Ebrahim AN (2018) Publishing Procedure and Strategies to Improve Research Visibility and Impact. https://figshare.com/articles/presentation/Publishing_Procedure_and_Strategies_to_Improve_Research_Visibility_and_Impact/7475036

Gajdács M (2020) Taxonomy and nomenclature of bacteria with clinical and scientific importance: current concepts for pharmacists and pharmaceutical scientists. Acta Pharm Hung 89(4):99–108

Gemayel R (2016) How to write a scientific paper. FEBS 283(21):3882–3885

Article CAS Google Scholar

Grech V, Cuschieri S (2018) Write a scientific paper (WASP)-a career-critical skill. Early Human Dev 117:96–97

Haak LL, Fenner M, Paglione L, Pentz E, Ratner H (2012) ORCID: a system to uniquely identify researchers. Learn Publ 25(4):259–264

Haralambides HE (2016) Dos and don’ts in scholarly publishing. Marit Econ Logist 18(2):101–102

Haralambides HE (2018) Dos and don’ts of scholarly publishing (part II). Marit Econ Logist 20(3):321–326

Hoogenboom BJ, Manske RC (2012) How to write a scientific article. Int J Sports Phys Ther 7(5):512–517

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Issakhanian L, Behzadi P (2019) Antimicrobial Agents and Urinary Tract Infections. Curr Pharm Des 25(12):1409–1423

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Jirge PR (2017) Preparing and publishing a scientific manuscript. J Hum Reprod Sci 10(1):3–9

Juhász J, Ligeti B, Gajdács M, Makra N, Ostorházi E, Farkas FB, Stercz B, Tóth Á, Domokos J, Pongor S, Szabó D (2021) Colonization dynamics of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae are dictated by microbiota-cluster group behavior over individual antibiotic susceptibility: a metataxonomic analysis. Antibiotics 10(3):e268

Kallet RH (2004) How to write the methods section of a research paper. Resp Care 49(10):1229–1232

Lilleyman J (1995) How to write a scientific paper—a rough guide to getting published. Arch Dis Child 72(3):268–270

Liumbruno GM, Velati C, Pasqualetti P, Franchini M (2013) How to write a scientific manuscript for publication. Blood Transf 11(2):217–226

Mack CA (2018) How to write a good scientific paper. The United States of America: Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers (SPIE) Press. ISBN 9781510619135

Meo SA (2018) Anatomy and physiology of a scientific paper. Saudi J Biol Sci 25(7):1278–1283

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mišak A, Marušić M, Marušić A (2005) Manuscript editing as a way of teaching academic writing: experience from a small scientific journal. J Second Lang Writ 14(2):122–131

O’Connor TR, Holmquist GP (2009) Algorithm for writing a scientific manuscript. Biochem Mol Biol Educ 37(6):344–348

Paróczai D, Sejben A, Kókai D, Virók DP, Endrész V, Burián K (2021) Beneficial immunomodulatory effects of fluticasone propionate in chlamydia pneumoniae-infected mice. Pathogens 10(3):e338

Petkau A, Stuart-Edwards M, Stothard P, Van Domselaar G (2012) Interactive microbial genome visualization with GView. Bioinformatics 26(24):3125–3126

Ranjbar R, Behzadi P, Mammina C (2016) Respiratory tularemia: Francisella tularensis and microarray probe designing. Open Microbiol J 10:176–182

Rasko Z, Nagy L, Radnai M, Piffkó J, Baráth Z (2016) Assessing the accuracy of cone-beam computerized tomography in measuring thinning oral and buccal bone. J Oral Implant 42:311–314

Shakeel S, Iffat W, Qamar A, Ghuman F, Yamin R, Ahmad N, Ishaq SM, Gajdács M, Patel I, Jamshed S (2021) Pediatricians’ compliance to the clinical management guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia in infants and young children in Pakistan. Healthcare 9(6):e701

Singer AJ, Hollander JE (2009) How to write a manuscript. J Emerg Med 36(1):89–93

Singh V, Mayer P (2014) Scientific writing: strategies and tools for students and advisors. Biochem Mol Biol Educ 42(5):405–413

Stájer A, Kajári S, Gajdács M, Musah-Eroje A, Baráth Z (2020) Utility of photodynamic therapy in dentistry: current concepts. Dent J 8(2):43

Stenson JF, Foltz C, Lendner M, Vaccaro AR (2019) How to write an effective materials and methods section for clinical studies. Clin Spine Surg 32(5):208–209

Tahaei SAS, Stájer A, Barrak I, Ostorházi E, Szabó D, Gajdács M (2021) Correlation between biofilm-formation and the antibiotic resistant phenotype in staphylococcus aureus isolates: a laboratory-based study in Hungary and a review of the literature. Infect Drug Res 14:1155–1168

Tomasello G, Armenia I, Molla G (2020) The protein imager: a full-featured online molecular viewer interface with server-side HQ-rendering capabilities. Bioinformatics 36(9):2909–2911

Tóth Á, Makai A, Jánvári L, Damjanova I, Gajdács M, Urbán E (2020) Characterization of a rare bla VIM-4 metallo-β-lactamase-producing Serratia marcescens clinical isolate in Hungary. Heliyon 6(6):e04231

Tullu M, Karande S (2017) Writing a model research paper: a roadmap. J Postgrad Med 63(3):143–146

Download references

Payam Behzadi would like to thank the Islamic Azad University, Shahr-e-Qods Branch, Tehran, Iran, for approving the organization of the workshop on “How to write a scientific paper?” Márió Gajdács would also like to acknowledge the support of ESCMID’s “30 under 30” Award.

Open access funding provided by University of Szeged. Márió Gajdács was supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship (BO/00144/20/5) of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and the New National Excellence Programme (ÚNKP-20-5-SZTE-330) of the Ministry of Human Resources.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Microbiology, College of Basic Sciences, Shahr-e-Qods Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, 37541-374, Iran

Payam Behzadi

Institute of Medical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Nagyvárad tér 4, 1089, Hungary

Márió Gajdács

Department of Pharmacodynamics and Biopharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Szeged, Szeged, Eötvös utca 6., 6720, Hungary

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Márió Gajdács .

Ethics declarations

The authors declare that they have no competing interests, monetary or otherwise.

Ethical statement

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Behzadi, P., Gajdács, M. Writing a strong scientific paper in medicine and the biomedical sciences: a checklist and recommendations for early career researchers. BIOLOGIA FUTURA 72 , 395–407 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42977-021-00095-z

Download citation

Received : 08 April 2021

Accepted : 16 July 2021

Published : 28 July 2021

Issue Date : December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s42977-021-00095-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Scientific research

- Publications

- Medical publications

- Clinical medicine

- Peer review

- Academic training

- Abstracting and indexing

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 10 November 2020

A brief guide to the science and art of writing manuscripts in biomedicine

- Diego A. Forero 1 , 2 ,

- Sandra Lopez-Leon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7504-3441 3 &

- George Perry 4

Journal of Translational Medicine volume 18 , Article number: 425 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

22 Citations

210 Altmetric

Metrics details

Publishing articles in international scientific journals is the primary method for the communication of validated research findings and ideas. Journal articles are commonly used as a major input for evaluations of researchers and institutions. Few articles have been published previously about the different aspects needed for writing high-quality articles. In this manuscript, we provide an updated and brief guide for the multiple dimensions needed for writing manuscripts in the health and biological sciences, from current, international and interdisciplinary perspectives and from our expertise as authors, peer reviewers and editors. We provide key suggestions for writing major sections of the manuscript (e.g. title, abstract, introduction, methods, results and discussion), for submitting the manuscript and bring an overview of the peer review process and of the post-publication impact of the articles.

Introduction

Publishing articles in international scientific journals is the current primary approach for the communication of validated research findings and ideas. Scientific papers are commonly used as a major input for evaluations of researchers and institutions [ 1 , 2 ]. However, taking into account the evolving and multidimensional landscape of the publishing process, there is a need for additional updated training in the science and art of writing manuscripts for scientific journals.

Few articles have been published previously about the different aspects needed for writing high-quality articles [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. In this article, we provide an updated and brief guide for the multiple dimensions needed for writing manuscripts in the health and biological sciences, from current, international and interdisciplinary perspectives and from our expertise as authors, peer reviewers and editors, extending and complementing previous publications about this topic. The writing of manuscripts in biomedicine has its own standards, including the availability of multiple guidelines for reporting different types of studies, which are discussed in this article.

General recommendations

One of the first steps before starting to write an article should be to read the main papers that have been previously published on the subject. The first search might be focused on the available literature reviews and meta-analyses, and key for a scientist, the technique of performing a proper literature review [ 7 ]. Science advances by building on what it is known and there is no point in re-inventing the wheel [ 8 ].

It has been suggested, when writing scientific papers, to keep it short, compact and simple, avoiding the excessive use of adjectives and adverbs [ 9 ]. If you read a word or sentence and it does not add anything, delete it.

The success of an article depends on the quality of primary data and their analyses, on the way it is written and on the clearness of the tables and figures. It is fundamental to follow the current standards of research integrity (such as avoiding plagiarism and data manipulation) [ 10 ]. Both negative and positive results should be published, to avoid publication bias [ 11 ].

Authors should keep in mind that scientific writing is a process that involves multiple steps, takes time, dedication and inspiration, and involves patience, motivation, analytical thinking and adherence to high-quality standards [ 86 ]. Table 1 provides an important number of online resources that facilitate the writing of scientific manuscripts.

Following international recommendations for the authorship of articles in the biomedical sciences, such as the ones from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), is a fundamental topic in scientific publications, in order to avoid ghost and gift authorship practices [ 12 , 13 ]. In general, authors should have a significant involvement in these 4 points: (1) study concept/design, data collection or data analysis/interpretation (2) drafting/revising the manuscript, (3) approving the final version and (4) holding responsibility for accuracy and integrity of all aspects of the reported research [ 14 ].

There is a trend for the increase of the number of authors over the years [ 15 ], which is a reflection of globalization and the increasing complexity of medical research [ 16 ]. In the last two decades, there has been an increased use of consortia authorship with very long lists of authors, usually derived from international mega-collaborations. Authors from non-English speaking countries might have to take into account the current standards for names (two first names and one last name), to avoid confusion in the indexing processes in databases. Authors with two last names can hyphen their two last names to avoid confusing their first last name with a middle name, although the use of ORCID identifiers facilitates the disambiguation of author profiles.

The meaning of the order of the listed authors varies between fields. In many disciplines, the author order indicates the magnitude of the contribution, with the last author usually representing the principal investigator [ 17 ]. It is possible to have an equal co-authorship, either for the first or corresponding authors [ 18 ].

Title and abstract

The Title [ 19 ] and the Abstract [ 20 ] are the two most visible items of the article [ 21 ], as they are the main sections indexed in bibliographic databases. These two elements compete for the reader’s attention; therefore both should be informative, accurate, attractive, concise, clear and specific [ 19 , 20 ]. It is advisable that the title of the manuscript reflects the actual findings of the work and be concise.

The Abstract section should provide a brief description of the main sections of the manuscript, describing key methods, findings and conclusions. It is recommended that the abstract be specific, clear, unbiased, honest, concise, precise, stand-alone, complete, and scholarly [ 22 ]. An important number of medical journals ask for structured abstracts. Usually, keywords are provided at the end of the Abstract section and the use of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) as keywords is quite helpful.

Introduction section

Although the standards of the length of the Introduction vary between scientific fields (for example, they are longer in psychology journals), it is recommended that the introduction section should be concise, avoiding long reviews about the topics of the article. It has been proposed that the introduction section be designed as a cone or funnel, starting with the main points of the general topic, followed by a highlight of the existing knowledge gap, the hypothesis or main question of the article and ending with a brief overview of the approach of the current work [ 23 ].

Another recommendation is to keep it simple, including three main paragraphs: the first paragraph explaining what is known, the second what is not known and the third what the objective of the study is and explain what it will add to the scientific knowledge. When stating what is known, it should not be a full review of the literature, but it should be the essential information needed to understand the background. Information from the introduction should not overlap with the discussion. The paragraph explaining what is unknown should be focused on helping the reader understand why the research is being performed. The last paragraph should state the research question or hypothesis [ 24 ]. It is important to cite key articles (both recent reviews and related primary works) and to highlight the novelty of the current work.

Methods section

This section is essential and should be written to facilitate other researchers enabling them to replicate the study. This section has been compared to a recipe, which includes all the ingredients and how they need to be combined [ 25 ].

Key details of methods employed, such as overall design of the study, inclusion and exclusion criteria, sample sizes and statistical power, should be described [ 26 ]. Another way to subdivide it is with subheadings that might include: study design, setting, subjects, data collection and data analysis [ 25 ]. The incorporation of data about the origins of samples and validated criteria for diagnoses is indispensable, including key references to validated instruments and methodologies. Description of approval by institutional ethics committees and use of informed consent, when needed, is fundamental. In the case of the use of equipment and reagents, details of the respective manufacturers are needed. Statistical and bioinformatic analyses should be described clearly, including the details of statistical tests and the software used [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ]. It is fundamental that all the results described in the Results section correlate with the procedures described in the Methods section.

Results section

The Results section should provide an adequate and complete description of the main findings of the work carried out. It is suggested to avoid the repetition of the same exact content of the Tables or Figures and to leave the interpretation of the results of the findings to the Discussion section [ 31 ]. The main messages and details of the Results section should be provided in the Figures and Tables. No interpretation should be provided in this section.

The results section should be seen as a mirror of the methods: for every method provided, there should be a corresponding result. Subheadings can be included and some suggestions might be: recruitment/response, characteristics of the sample, findings from primary analyses, secondary analyses and additional findings [ 32 ]. Exact p values should be presented and must always be shown together with the estimates and confidence intervals. There should be a consistency with the number of decimal places presented in the results section and in the tables. It is common to present one or two decimals places. Always present the absolute number of cases, in addition to relative measures (e.g. percentage was 22% -33/150-) [ 32 ].

Tables and figures

Tables facilitate the detailed presentation of the results and they should be constructed adequately. Abbreviations are useful for avoiding repetitions of phrases and should be explained in the footnotes [ 33 ]. Each table or figure should be self-explanatory, and there should be no need to read the text to be able to understand it. They have to be presented in the same chronological order, following how they are presented in the text [ 34 ].

For tables where a lot of information is presented, the p values that are statistically significant can be presented in bold. In case of long or complex tables, it is helpful to provide them as supplementary files, leaving the key data in the tables of the main text. It is important to provide details of statistical significance in the table, in order to avoid going back and forth between the tables and the text to read key data.

The creation of figures for scientific articles involves data visualization. A major element in the creation of figures is their focus on the representation of key findings without biases, avoiding the generation of overly complex figures. In addition, it is important to remove the repetition of the same data that is also presented as tables in the main manuscript. Description of key conventions should be provided in detail in the figure legends and it is important to avoid the misrepresentation of data [ 35 ], particularly digital enhancement. As the large majority of journals are published and distributed in digital formats, there are no actual restrictions for the adequate use of colors in scientific images. In case of photographs, it is important to follow the guidelines of the journals regarding image size and resolution. In addition, other recommendations are related to the use of adequate tools and parameters for the generation of figures [ 36 ].

Discussion section

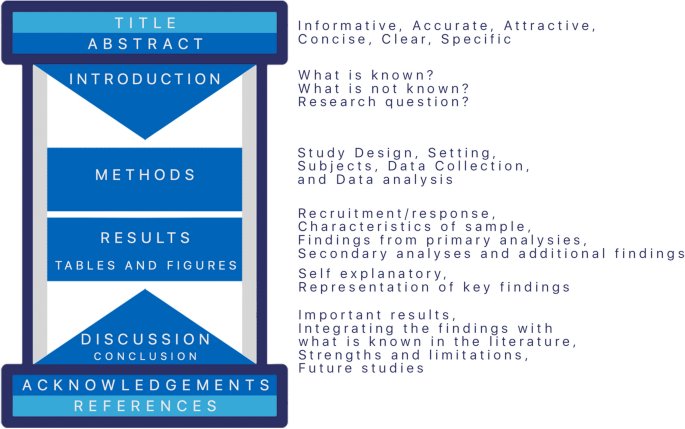

It has been proposed that the general outline of the discussion can be seen as an inverted funnel. Thus, it has been suggested that the configurations of the introduction and discussion sections can have, together, the form of an hourglass [ 37 ] (Fig. 1 ). The first paragraph is usually a summary of the important results, focused on answering the research question. The next paragraphs should focus on integrating the findings with what is known in the literature. If there are different findings, each should have a separate paragraph. The discussion of each result should follow the same order of the methods and results. A balanced contextualization of findings of the current study should be provided by citing the key previous original articles and related reviews that put the results in perspective [ 38 ]. If there are differences between the findings and previously published studies, the differences and similarities of the results and studies should be stated.

A graphical overview of the general structure of research articles

It is important to list the strengths and the limitations of the study. An explanation of the implications of those limitations should be included. An essential point is to include the needs and the perspectives for future studies. It can be stated that the results need replication or to highlight new questions that appeared after the analyses. This point can be of great guidance for future studies and can help the advance of science. It is highly advisable to avoid very long discussion sections and overstatements about the actual findings. The discussion section should not have results that were not described in the Results section. The last paragraph should include a conclusion that clearly states what the study adds to the knowledge.

References section

Although each journal usually has its own citation style, the Vancouver style is quite common in medical journals. There are several freely and commercially available programs (such as EndNote, Zotero or Mendeley) that facilitate the citations process and the generation of the bibliography, including the details for multiple citation styles. They can help to organize, store, download -and most importantly- format the references to the style requirements of the journal you want to submit to. By having the references in these programs, it is easy to reformat the style for any other journal in a matter of seconds.

Always try to cite the original source behind a key statement, making sure that the reference you mention is not only mentioning another source. If you need to choose among several references, take into consideration the level of evidence, the year of publication and the quality of the work [ 39 ].

It is important to verify that the bibliography includes all the publications cited and to check issues with names of authors or journals. Several journals have limitations in the number of citations for certain types of publications.

Acknowledgments and other sections

Usually, the authors thank their funding agencies for their economical support for the studies carried out. In addition, it is possible to include acknowledgements to people who helped with the development of the work (technical support, for example) or in the writing of the manuscript (such as corrections of use of the English language) [ 40 ]. In several cases, the journals ask for declarations about ethical considerations and declarations of the roles of individual authors (such as the design of the study and/or the collection or analysis of the data) [ 41 ]. Declarations of potential conflicts of interest is fundamental for the transparency of scientific activities [ 12 , 42 ].

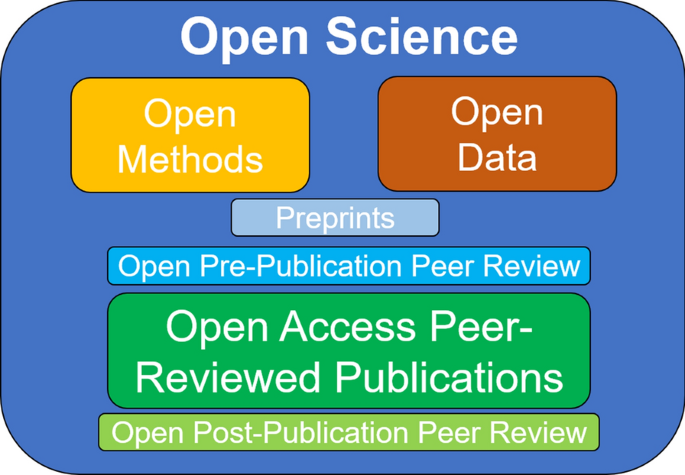

Supplementary data

With modern high-throughput methods, the size of the analyzed datasets is becoming larger and larger. This means that there is a growing need to provide access to the large datasets as supplementary files (such as spreadsheets or pdf files) or to include them in publicly available repositories (such as OSF or figshare) [ 43 ]. In addition, certain fields have specific guidelines asking authors to submit their data to specific online repositories (such as the NCBI GEO database for whole genome expression data) [ 44 ].

Review articles and other types of publications

There are two main types of review articles: systematic reviews and narrative reviews. In the case of systematic reviews and meta-analyses there are important standards to follow, including the need for well-defined search strategies [ 45 ]. For the writing of narrative reviews [ 46 , 47 ], it is essential to define its scope and current needs and it is highly advisable to construct tables and figures to consolidate and visualize the key information. Articles for case reports follow a different structure and there are recommendations about their development [ 48 ].

Reporting guidelines

It is important to follow published guidelines for the reporting of studies in clinical research, such as STROBE for observational studies [ 49 ], STROBE-ME for molecular epidemiology studies [ 50 ], STREGA for genetic association studies [ 51 ], PRISMA for systematic reviews and meta-analyses [ 52 ], TRIPOD for prediction models of diagnosis or prognosis [ 53 ], CONSORT for clinical trials [ 54 ], CARE for case reports [ 55 ] and AGREE II for practice guidelines [ 56 ], in addition to ARRIVE 2.0 for animal research [ 57 ]. For molecular and cellular analyses, there are several important guidelines, such as MIQE for qPCR [ 58 , 59 ], flow cytometry [ 60 ], cell death [ 61 ], mutational analyses [ 62 ], simulation experiments [ 63 ] and gene nomenclatures [ 64 , 65 ].

Find the best candidate journals

There are several aspects that the authors should take into account in the selection of a journal, such as local standards of publications, the visibility or impact of the journals and their affinities with the topics of the manuscripts. It is highly advisable to verify the indexing of the journals in key databases, such as PubMed, Scopus/Scimago (quartiles) and Journal Citation Reports (impact factor) [ 66 , 67 ]. Finally, authors should be careful with the growing number of predatory journals [ 68 ], which commonly mention spurious impact factors [ 69 ]. Another way to determine which journal is suitable is to see the list of the references in your study. Before selecting the journal, read all the instructions and make sure the scope of the journal and editor preference fits your manuscript. Make a list of 3 to 5 journals, and rank them [ 70 ]. In several cases, sending a pre-submission enquiry to the editor of the journal is helpful [ 71 ]. There is a growing trend for the initial divulgation of manuscripts as preprints, in repositories such as bioRxiv and medRxiv [ 72 ].

Submission and peer review