- Social Media

The Importance of Maintaining Native Language

The United States is often proudly referred to as the “melting pot.” Cultural diversity has become a part of our country’s identity. However, as American linguist, Lilly Wong Fillmore, pointed out in her language loss study, minority languages remain surprisingly unsupported in our education system (1991, p. 342). Although her research was conducted more than twenty years ago, this fact still rings true. Many non-minority Americans are not aware of the native language loss that has become prevalent in children of immigrant parents. While parents can maintain native language, children educated in U.S. schools quickly lose touch with their language heritage. This phenomenon, called subtractive bilingualism, was first discovered by psychologist Wallace Lambert, in his study of the language acquisition of French-Canadian children. The term refers to the fact that learning a second language directly affects primary language, causing loss of native language fluency (Fillmore, 1991, p. 323). This kind of language erosion has been integral to the narrative of this country for some time. Many non-minority Americans can trace their family tree back to a time when their ancestors lost fluency in a language that was not English. Today, due to the great emphasis on assimilation into the United States’ English-speaking culture, children of various minorities are not only losing fluency, but also their ability to speak in their native language, at all (Fillmore, 1991, p. 324).

The misconceptions surrounding bilingual education has done much to increase the educational system’s negative outlook on minority languages. In Lynn Malarz’s bilingual curriculum handbook, she states that “the main purpose of the bilingual program is to teach English as soon as possible and integrate the children into the mainstream of education” (1998). This handbook, although written in 1998, still gives valuable insight into how the goals of bilingual education were viewed. Since English has become a global language, this focus of bilingual education, which leads immigrant children to a future of English monolingualism, seems valid to many educators and policymakers. Why support minority languages in a country where English is the language of the prosperous? Shouldn’t we assimilate children to English as soon as possible, so that they can succeed in the mainstream, English-speaking culture? This leads us to consider an essential question: does language loss matter? Through the research of many linguists, psychologists, and language educators, it has been shown that the effect of native language loss reaches far. It impacts familial and social relationships, personal identity, the socio-economic world, as well as cognitive abilities and academic success. This paper aims to examine the various benefits of maintaining one’s native language, and through this examination, reveal the negative effects of language loss.

Familial Implications

The impact of native language loss in the familial sphere spans parent-child and grandparent-grandchild relationships, as well as cultural respects. Psychologists Boutakidis, Chao, and Rodríguez, (2011) conducted a study of Chinese and Korean immigrant families to see how the relationships between the 9th-grade adolescences and their parents were impacted by native language loss. They found that, because the adolescents had limited understanding and communicative abilities in the parental language, there were key cultural values that could not be understood (Boutakidis et al., 2011, p. 129). They also discovered there was a direct correlation between respect for parents and native language fluency. For example, honorific titles, a central component of respect unique to Chinese and Korean culture, have no English alternatives (p.129). They sum up their research pertaining to this idea by stating that “children’s fluency in the parental heritage language is integral to fully understanding and comprehending the parental culture” (Boutakidis et al., 2011, p. 129). Not only is language integral to maintaining parental respect, but also cultural identity.

In her research regarding parental perceptions of maintaining native language, Ruth Lingxin Yan (2003) found that immigrant parents not only agree on the importance of maintaining native language, but have similar reasoning for their views. She discovered that maintaining native language was important to parents, because of its impact on heritage culture, religion, moral values, community connections, and broader career opportunities.

Melec Rodriguez, whose parents immigrated to the United States before he was born, finds that his native language loss directly impacts his relationship with his grandparents. Rodriguez experienced his language loss in high school. He stated that due to his changing social group and the fact that he began interacting with his family less, he found himself forgetting “uncommon words in the language.” His “struggle to process information” causes him to “take a moment” to “form sentences in [his] mind during conversations” (M. Rodriguez, personal communication, Nov. 3, 2019). Of his interactions with his grandparents, who have a limited understanding of English, he stated:

“I find very often that I simply cannot think of a way to reply while conveying genuine emotion, and I know they feel I am detached at times because of that. I also struggle to tell exciting stories about my experiences and find it hard to create meaningful conversations with family” (M. Rodriguez, personal communication, Nov. 3, 2019).

Rodriguez’s native language loss creates a distinct communicative barrier between him and his grandparents, causing him difficulty in genuine connection building. Although this is a relatively obvious implication of native language loss, it is nonetheless a concerning effect.

Personal Implications

Native language, as an integral part of the familial sphere, also has strong connections on a personal level. The degree of proficiency in one’s heritage language is intrinsically connected to self-identity. The Intercultural Development Research Association noted this connection, stating that “the child’s first language is critical to his or her identity. Maintaining this language helps the child value his or her culture and heritage, which contributes to a positive self-concept. (“Why Is It Important to Maintain the Native Language?” n.d.). Grace Cho, professor and researcher at California State University, concluded “that [heritage language] development can be an important part of identity formation and can help one retain a strong sense of identity to one's own ethnic group” (Cho, 2000, p. 369). In her research paper, she discussed the “identity crisis” many Korean American students face, due to the lack of proficiency they have in their heritage language (p. 374). Cho found that students with higher levels of fluency could engage in key aspects of their cultural community, which contributed greatly to overcoming identity crises and establishing their sense of self (p. 375).

Social Implications

Native language loss’ connections to family relationships and personal identity broaden to the social sphere, as well. Not only can native language loss benefit social interactions and one’s sense of cultural community, it has large-scale socioeconomic implication. In Cho’s study (2000) she found that college-aged participants with Korean ancestry were faced with many social challenges due to limited fluency in Korean. Participants labeled with poor proficiency remarked on the embarrassment they endured, leading them to withdraw from social situations that involved their own ethnic group (p. 376). These students thus felt isolated and excluded from the heritage culture their parents actively participated in. Native language loss also caused students to face rejection from their own ethnic communities, resulting in conflicts and frustration (p. 377). Participants that did not complain of any conflict actively avoided their Korean community due to their lack of proficiency (p. 378). Participants who were labeled as highly proficient in Korean told of the benefits this had, allowing them to “participate freely in cultural events or activities” (p. 374). Students who were able to maintain their native language were able to facilitate meaningful and beneficial interactions within their cultural community.

Melec Rodriguez made similar comments in his experience as a Spanish and English- speaking individual. Although his native language loss has negatively affected his familial relationships, he has found that, in the past, his Spanish fluency “allowed for a greater social network in [his] local community (school, church, events) as [he] was able to more easily understand and converse with others” (M. Rodriguez, personal communication, Nov. 3, 2019). As this research suggests, native language fluency has a considerate influence on social interactions. Essentially, a lack of fluency in one’s native language creates a social barrier; confident proficiency increases social benefits and allows genuine connections to form in one’s cultural community.

Benefits to the Economy

Maintaining native language not only benefits personal social spheres, but also personal career opportunities, and thereby the economy at large. Peeter Mehisto and David Marsh (2011), educators central to the Content and Language Integrated Learning educational approach, conducted research into the economic implications of bilingualism. Central to their discussion was the idea that “monolingualism acts as a barrier to trade and communication” (p. 26). Thus, bilingualism holds an intrinsic communicative value that benefits the economy. Although they discovered that the profits of bilingualism can change depending on the region, they referred to the Fradd/Boswell 1999 report, that showed Spanish and English-speaking Hispanics living in the United States earned more than Hispanics who had lost their Spanish fluency (Mehisto & Marsh, 2011, p. 22). Mehisto and Marsh also found that bilingualism makes many contributions to economic growth, specifically “education, government, [and] culture…” (p. 25). Bilingualism is valuable in a society in which numerous services are demanded by speakers of non-English languages. The United States is a prime example of a country in which this is the case.

Increased Job Opportunites

Melec Rodriguez, although he has experienced native language loss, explained that he experienced increased job opportunities due to his Spanish language background. He stated:

“Living in south Texas, it is very common for people to struggle with either English or Spanish, or even be completely unable to speak one of the languages. There are many restaurants or businesses which practice primarily in one language or the other. Being bilingual greatly increased the opportunity to get a job at many locations and could make or break being considered as a candidate” (M. Rodriguez, personal communication, Nov. 3, 2019).

Rodriguez went on to explain that if he were more confident in his native language, he would have been able to gain even more job opportunities. However, as his language loss has increased through the years, Spanish has become harder to utilize in work environments. Thus, maintaining one’s native language while assimilating to English is incredibly valuable, not only to the economy but also to one’s own occupational potential.

Cognitive and Academic Implications

Those who are losing native language fluency due to English assimilation are missing out on the cognitive and academic benefits of bilingualism. The Interculteral Development Research Association addresses an important issue in relation to immigrant children and academic success. When immigrant children begin at U. S. schools, most of their education is conducted in English. However, since these students are not yet fluent in English, they must switch to a language in which they function “at an intellectual level below their age” (“Why Is It Important to Maintain the Native Language?” n.d.). Thus, it is important that educational systems understand the importance of maintaining native language. It is also important for them to understand the misconceptions this situation poses for the academic assessments of such students.

In Enedina Garcia-Vazquez and her colleague's (1997) study of language proficiency’s connection to academic success, evidence was found that contradicted previous ideas about the correlation. The previous understanding of bilingualism in children was that it caused “mental confusion,” however, this was accounted for by the problematic methodologies used (Garcia- Vazquez, 1997, p. 395). In fact, Garcia-Vazquez et al. discuss how bilingualism increases “reasoning abilities” which influence “nonverbal problem-solving skills, divergent thinking skills, and field independence” (p. 396). Their study of English and Spanish speaking students revealed that proficiency in both languages leads to better scores on standardized tests (p. 404). The study agreed with previous research that showed bilingual children to exceed their monolingual peers when it came to situations involving “high level…cognitive control” (p. 396). Bilingualism thus proves to have a distinct influence on cognitive abilities.

Mehisto and Marsh (2011) discuss similar implications, citing research that reveals neurological differences in bilingual versus monolingual brains. This research indicates that the “corpus callosum in the brain of bilingual individuals is larger in area than is the case for monolinguals” (p. 30). This proves to be an important difference that reveals the bilingual individual’s superiority in many cognitive functions. When it comes to cognitive ability, Mehisto and Marsh discuss how bilinguals are able to draw on both languages, and thus “bring extra cognitive capacity” to problem-solving. Not only can bilingualism increase cognitive abilities, but it is also revealed to increase the “cognitive load” that they are able to manage at once (p.30). Many of the academic benefits of bilingualism focus on reading and writing skills. Garcia-Vazquez’s study focuses on how students who were fluent in both Spanish and English had superior verbal skills in both writing and reading, as well as oral communication (p. 404). However, research indicates that benefits are not confined to this area of academics. Due to increased cognition and problem-solving skills, research indicates that bilingual individuals who are fluent in both languages achieved better in mathematics than monolinguals, as well as less proficient bilinguals (Clarkson, 1992). Philip Clarkson, a mathematics education scholar, conducted one of many studies with students in Papua New Guinea. One key factor that Clarkson discovered was the importance of fluency level (p. 419). For example, if a student had experienced language loss in one of their languages, this loss directly impacted their mathematical competence. Not only does Clarkson’s research dissuade the preconceived notions that bilingualism gets in the way of mathematical learning, it actually proves to contribute “a clear advantage” for fluent bilingual students (p. 419). Clarkson goes on to suggest that this research disproves “the simplistic argument that has held sway for so long for not using languages other than English in Papua New Guinea schools” (p. 420). He thus implies the importance of maintaining the native language of the students in Papua New Guinea since this bilingual fluency directly impacts mathematical competency.

Both Garcia-Vazquez et al. and Mehisto and Marsh reveal how proficiency in two languages directly benefits a brain’s functions. Their research thus illustrates how maintaining one’s native language will lead to cognitive and academic benefits. Clarkson expands on the range of academic benefits a bilingual student might expect to have. It is important to note that, as Clarkson’s research showed, the fluency of a bilingual student has much influence on their mathematical abilities. Thus, maintaining a solid fluency in one’s native language is an important aspect of mathematical success.

Suggested Educational Approach

The acculturation that occurs when immigrants move to the United States is the main force causing language loss. Because of the misconceptions of bilingual education, this language loss is not fully counteracted. Policymakers and educators have long held the belief that bilingual education is essentially a “cop-out” for immigrants who do not wish to assimilate to the United States’ English-speaking culture (Fillmore, 1991, p. 325). However, bilingual education is central to the maintenance of native language. Due to the misconceptions and varied views on this controversial subject, there are two extremes of bilingual education in the United States. In Malarz’s (1998) curriculum handbook, she explains the two different viewpoints of these approaches. The first pedological style’s goal is to fully assimilate language-minority students to English as quickly and directly as possible. Its mindset is based on the idea that English is the language of the successful, and that by teaching this language as early as possible, language- minority children will have the best chance of prospering in mainstream society. However, this mindset is ignorant of the concept of subtractive bilingualism, and thus is not aware that its approach is causing native language loss. The second approach Malarz discusses is the bilingual education that places primary importance on retaining the student’s heritage culture, and thereby, their native language. This approach faces much criticism ,since it seems to lack the appropriate focus of a country that revolves around its English-speaking culture. Neither of these approaches poses a suitable solution to the issue at hand. Maintaining native language, as we have discussed, is extremely valuable. However, learning English is also an important goal for the future of language-minority students. Thus, the most appropriate bilingual educational approach is one of careful balance. Native language, although important, should not be the goal, just as English assimilation should not be the central focus. Instead, the goal of bilingual education should be to combine the two former goals and consider them as mutually inclusive. This kind of balanced education is certainly not mainstream, although clearly needed. In Yan’s research regarding parental perceptions of maintaining native language, she found that parents sought after “bilingual schools or those that provided instruction with extra heritage language teaching” (2003, p. 99). Parents of language-minority students recognize the importance of this kind of education and educators and policymakers need to, as well.

The ramifications of native language loss should not be disregarded. Unless bilingual children are actively encouraged and assisted by parents and teachers to maintain their native language, these children will lose their bilingualism. They will not only lose their native fluency and the related benefits, but they will also experience the drawbacks associated with language loss. As the research presented in this article illustrates, there are several specific advantages to maintaining native language. The familial implications reveal that native language loss is detrimental to close relationships with parents and grandparents. Maintaining native language allows for more meaningful communication that can facilitate respect for these relationships as well as heritage culture as a whole. Native language maintenance is also an important factor in the retainment of personal identity. In regard to the social sphere, isolation and a feeling of rejection can occur if native language is not maintained. Additionally, it was found that maintaining native language allows for greater involvement in one’s cultural community. Other social factors included the benefits of bilingualism to the economy as well as the greater scope of job opportunities for bilingual individuals. A variety of studies concluded that there are many cognitive and academic benefits of retaining bilingualism. Due to the many effects of native language loss and the variety of benefits caused by maintaining native language, it can be determined that native language retainment is incredibly important.

Boutakidis, I. P., Chao, R. K., & Rodríguez, J. L. (2011). The role of adolescent’s native language fluency on quality of communication and respect for parents in Chinese and Korean immigrant families. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 2(2), 128–139. doi: 10.1037/a0023606.

Cho, G. (2000). The role of heritage language in social interactions and relationships: Reflections from a language minority group. Bilingual Research Journal, 24(4), 369-384. doi:10.1080/15235882.2000.10162773

Clarkson, P. C. (1992). Language and mathematics: A comparison of bilingual and monolingual students of mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 23(4), 417.

Fillmore, L. W. (1991). When learning a second language means losing the first. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 6(3), 323–346. doi: 10.1016/s0885-2006(05)80059-6

Garcia-Vazquez, E., Vazquez, L. A., Lopez, I. C., & Ward, W. (1997). Language proficiency and academic success: Relationships between proficiency in two languages and achievement among Mexican American students. Bilingual Research Journal, 21(4), 395.

Malarz, L. (1998). Bilingual Education: Effective Programming for Language-Minority Students. Retrieved November 10, 2019, from http://www.ascd.org/publications/curriculum_handbook/413/chapters/Biling... n@_Effective_Programming_for_Language-Minority_Students.aspx .

Mehisto, P., & Marsh, D. (2011). Approaching the economic, cognitive and health benefits of bilingualism: Fuel for CLIL. Linguistic Insights - Studies in Language and Communication, 108, 21-47.

Rodriguez, M. (2019, November 3). Personal interview.

Why is it Important to Maintain the Native Language? (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.idra.org/resource-center/why-is-it-important-to-maintain-the... language/.

Yan, R. (2003). Parental Perceptions on Maintaining Heritage Languages of CLD Students.

Bilingual Review / La Revista Bilingüe, 27(2), 99-113. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25745785

The UNESCO Courier

Indigenous languages: Knowledge and hope

By Minnie Degawan

The state of indigenous languages today mirrors the situation of indigenous peoples. In many parts of the world, they are on the verge of disappearance. The biggest factor contributing to their loss is state policy. Some governments have embarked on campaigns to extinguish indigenous languages by criminalizing their use – as was the case in the Americas, in the early days of colonialism. Some countries continue to deny the existence of indigenous peoples in their territories – indigenous languages are referred to as dialects, and accorded less importance than national languages, contributing to their eventual loss.

But today, the major influence on the sorry state of their languages is the fact that indigenous peoples are threatened themselves.

Grave threats

The biggest threat comes from climate change, which is gravely impacting their subsistence economies. So-called development projects such as dams, plantations, mines and other extractive activities are also taking their toll, as are government policies that minimize diversity and encourage homogeneity. There is an increasing propensity of states to criminalize any dissent, resulting in more and more rights violations. We have witnessed an unprecedented rise in the number of indigenous peoples harassed, arrested, imprisoned, and even summarily executed for daring to defend their territories.

What is often overlooked in discussions on these concerns is the impact of these threats on indigenous cultures and values. Indigenous peoples derive their identities, values and knowledge systems from their interaction with their territories, whether forests or seas. Their languages are shaped by their environment – it is their attempts to describe their surroundings that forms the bases of their unique tongues. Thus, when the territory is altered, changes also occur in the culture and eventually, in the language.

The Inuit, for example, have more than fifty terms for snow, each appropriately describing different types of snow, in different situations. Snow is a prime element that the Inuit live with, and therefore have come to know intimately. The same is true with the Igorot of the Cordillera in the Philippines when describing rice – from when it is but a seed ready for planting to when it is fully ripe and ready for harvesting, to when it is newly cooked and ready to be eaten and when it takes the form of wine.

While new information and communication technologies could be used to enhance the learning process and provide tools to preserve indigenous languages, this is sadly not the case. Because indigenous peoples are considered minorities, their languages are often overlooked in positive efforts by governments to protect languages. For instance, in the Philippines, the government has launched the use of mother tongues in schools, but no resources are available in terms of teachers and learning materials to allow for indigenous children to be taught in their mother tongues. As a result, they end up mastering another language and eventually losing their own.

Notions and values lost

In addition, because of years of discrimination, many indigenous parents choose to teach and talk to their children in the dominant languages – in order to create optimal conditions for their social success. Since their mother tongue is often used only by older people, an entire generation of indigenous children can no longer communicate with their grandparents.

In my community, the Kankanaey Igorot, we have the concept of inayan , which basically prescribes the proper behaviour in various circumstances. It encapsulates the relationship of the individual to the community and to the ancestors. It goes beyond simply saying “be good”; it carries the admonition that “the spirits/ancestors will not approve”. Because many of the young people now no longer speak the local language and use English or the national language instead, this notion and value is being lost. The lack of dialogue between elders and the youth is exacting a toll, not just in terms of language but in ancestral ethical principles.

Keeping languages alive

However, with the growing global recognition of indigenous knowledge systems, the hope that indigenous languages will thrive and spread in spoken and written forms is being rekindled. Many indigenous communities have already instituted their own systems of revitalizing their languages. The Ainu of Japan have set up a learning system where the elders teach the language to their youth. Schools of Living Tradition in different indigenous communities in the Philippines similarly keep their cultural forms, including languages, alive.

This edition of the Courier is a welcome contribution to the worldwide effort to focus more on indigenous languages. It is a valuable companion to the UNESCO-Cambridge University Press book, Indigenous Knowledge for Climate Change Assessment and Adaptation , published in 2018. The book illustrates the importance of indigenous knowledge in addressing contemporary global challenges.

Photo: Jacob Maentz

Minnie Degawan

A Kankanaey Igorot from the Cordillera in the Philippines, Minnie Degawan is Director of the Indigenous and Traditional Peoples Program at Conservation International, based at its international headquarters in Virginia, United States. She has years of experience advocating for the greater recognition and respect of indigenous peoples’ rights, and has participated in various policy-making processes, including the drafting of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples ( UNDRIP ).

In the same issue

Related items

- Indigenous Languages and Knowledge (IYIL 2019)

- Topics: 2019_1

- Topics: Wide Angle

Other recent articles

Definition and Examples of Native Languages

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In most cases, the term native language refers to the language that a person acquires in early childhood because it is spoken in the family and/or it is the language of the region where the child lives. Also known as a mother tongue , first language , or arterial language .

A person who has more than one native language is regarded as bilingual or multilingual .

Contemporary linguists and educators commonly use the term L1 to refer to a first or native language, and the term L2 to refer to a second language or a foreign language that's being studied.

As David Crystal has observed, the term native language (like native speaker ) "has become a sensitive one in those parts of the world where native has developed demeaning connotations " ( Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics ). The term is avoided by some specialists in World English and New Englishes .

Examples and Observations

"[Leonard] Bloomfield (1933) defines a native language as one learned on one's mother's knee, and claims that no one is perfectly sure in a language that is acquired later. 'The first language a human being learns to speak is his native language; he is a native speaker of this language' (1933: 43). This definition equates a native speaker with a mother tongue speaker. Bloomfield's definition also assumes that age is the critical factor in language learning and that native speakers provide the best models, although he does say that, in rare instances, it is possible for a foreigner to speak as well as a native. . . . "The assumptions behind all these terms are that a person will speak the language they learn first better than languages they learn later, and that a person who learns a language later cannot speak it as well as a person who has learned the language as their first language. But it is clearly not necessarily true that the language a person learns first is the one they will always be best at . . .." (Andy Kirkpatrick, World Englishes: Implications for International Communication and English Language Teaching . Cambridge University Press, 2007)

Native Language Acquisition

"A native language is generally the first one a child is exposed to. Some early studies referred to the process of learning one's first or native language as First Language Acquisition or FLA , but because many, perhaps most, children in the world are exposed to more than one language almost from birth, a child may have more than one native language. As a consequence, specialists now prefer the term native language acquisition (NLA); it is more accurate and includes all sorts of childhood situations." (Fredric Field, Bilingualism in the USA: The Case of the Chicano-Latino Community . John Benjamins, 2011)

Language Acquisition and Language Change

"Our native language is like a second skin, so much a part of us we resist the idea that it is constantly changing, constantly being renewed. Though we know intellectually that the English we speak today and the English of Shakespeare's time are very different, we tend to think of them as the same--static rather than dynamic." (Casey Miller and Kate Swift, The Handbook of Nonsexist Writing , 2nd ed. iUniverse, 2000) "Languages change because they are used by human beings, not machines. Human beings share common physiological and cognitive characteristics, but members of a speech community differ slightly in their knowledge and use of their shared language. Speakers of different regions, social classes, and generations use language differently in different situations ( register variation). As children acquire their native language , they are exposed to this synchronic variation within their language. For example, speakers of any generation use more and less formal language depending on the situation. Parents (and other adults) tend to use more informal language to children. Children may acquire some informal features of the language in preference to their formal alternatives, and incremental changes in the language (tending toward greater informality) accumulate over generations. (This may help explain why each generation seems to feel that following generations are ruder and less eloquent , and are corrupting the language!) When a later generation acquires an innovation in the language introduced by a previous generation, the language changes." (Shaligram Shukla and Jeff Connor-Linton, "Language Change." An Introduction to Language And Linguistics , ed. by Ralph W. Fasold and Jeff Connor-Linton. Cambridge University Press, 2006)

Margaret Cho on Her Native Language

"It was hard for me to do the show [ All-American Girl ] because a lot of people didn't even understand the concept of Asian-American. I was on a morning show, and the host said, 'Awright, Margaret, we're changing over to an ABC affiliate! So why don't you tell our viewers in your native language that we're making that transition?' So I looked at the camera and said, 'Um, they're changing over to an ABC affiliate.'" (Margaret Cho, I Have Chosen to Stay and Fight . Penguin, 2006)

Joanna Czechowska on Reclaiming a Native Language

"As a child growing up in Derby [England] in the 60s I spoke Polish beautifully, thanks to my grandmother. While my mother went out to work, my grandmother, who spoke no English, looked after me, teaching me to speak her native tongue . Babcia, as we called her, dressed in black with stout brown shoes, wore her grey hair in a bun, and carried a walking stick.

"But my love affair with Polish culture began to fade when I was five--the year Babcia died. "My sisters and I continued to go to Polish school, but the language would not return. Despite the efforts of my father, even a family trip to Poland in 1965 could not bring it back. When six years later my father died too, at just 53, our Polish connection almost ceased to exist. I left Derby and went to university in London. I never spoke Polish, never ate Polish food nor visited Poland. My childhood was gone and almost forgotten. "Then in 2004, more than 30 years later, things changed again. A new wave of Polish immigrants had arrived and I began to hear the language of my childhood all around me--every time I got on a bus. I saw Polish newspapers in the capital and Polish food for sale in the shops. The language sounded so familiar yet somehow distant--as if it were something I tried to grab but was always out of reach.

"I began to write a novel [ The Black Madonna of Derby ] about a fictional Polish family and, at the same time, decided to enroll at a Polish language school.

"Each week I went through half-remembered phrases, getting bogged down in the intricate grammar and impossible inflections . When my book was published, it put me back in touch with school friends who like me were second-generation Polish. And strangely, in my language classes, I still had my accent and I found words and phrases would sometimes come unbidden, long lost speech patterns making a sudden reappearance. I had found my childhood again."

Joanna Czechowska, "After My Polish Grandmother Died, I Did Not Speak Her Native Language for 40 Years." The Guardian , July 15, 2009

Margaret Cho, I Have Chosen to Stay and Fight . Penguin, 2006

Shaligram Shukla and Jeff Connor-Linton, "Language Change." An Introduction to Language And Linguistics , ed. by Ralph W. Fasold and Jeff Connor-Linton. Cambridge University Press, 2006

Casey Miller and Kate Swift, The Handbook of Nonsexist Writing , 2nd ed. iUniverse, 2000

Fredric Field, Bilingualism in the USA: The Case of the Chicano-Latino Community . John Benjamins, 2011

Andy Kirkpatrick, World Englishes: Implications for International Communication and English Language Teaching . Cambridge University Press, 2007

- Get the Definition of Mother Tongue Plus a Look at Top Languages

- Nigerian English

- Language Acquisition in Children

- Chunk (Language Acquisition)

- New Englishes: Adapting the Language to Meet New Needs

- Universal Grammar (UG)

- How to Know When You Mispronounce a Word

- Native Speaker - Definition and Examples in English

- Overgeneralization Definition and Examples

- What Is Fluency?

- What Is American English (AmE)?

- An Introduction to Semantics

- English as a Global Language

- Postposition (Grammar)

- Generative Grammar: Definition and Examples

- Definition and Examples of Syntax

Reading, Writing and Preserving: Native Languages Sustain Native Communities

MAGAZINE OF SMITHSONIAN'S NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

- From Issue: Summer 2017 / Vol. 18 No. 2

- by John Haworth

“Most people know that we are losing species. Ask schoolchildren, and they’ll know about the panda or the orchid…but ask someone if they know that languages all over the world are dying, maybe one in 10 might.”

These are the words of Bob Holman, poet and expert on oral traditions, sounding the alarm on an impending Extinction Event in indigenous languages. Holman played a key role in the PBS documentary Language Matters with Bob Holman , produced by David Grubin. Scholars estimate that there are more than 6,000 languages spoken throughout the world, but we lose on average one every couple of weeks and hundreds will likely be lost within the next generation. According to Holman, “By the end of this century, half the world’s languages will have vanished. The die-off parallels the extinction of plant and animal species. The death of a language robs humanity of ideas, belief systems and knowledge of the natural world.”

Karis Jackson (left) and Nina Sanders (right) discuss the evolution of Crow beadwork while studying historic beaded martingales at the Cultural Resources Center of the National Museum of the American Indian, 2016. Photo By Zach Nelson, Recovering Voices Project, Smithsonian Institution

Ke Kula ‘o Na-wahı-okalani‘o-pu‘u is a Hawaiian language immersion school with grades K–12 on the Island of Hawaii, also known as Big Island, Hawaii. All the classes at Nawahi are taught in Hawaiian. Image Courtesy David Grubin Productions From The Film Language Matters With Bob Holman

The volcano at Kilauea on Hawaii Island. The volcano is called Pele by Hawaiians after the Hawaiian goddess who, according to legend, lives there. Image courtesy David Grubin Productions From The Film Language Matters With Bob Holman

Still image from The Fireflies that Embellish the Trees , (2015, 1:05 min. Mexico), an animated short fi lm based on a tradition from the Matlatzinca people. The story tells of resuming a Saint Peter’s Day tradition in which people and fireflies took care of trees so they bore more fruit. The film short told in the Matlatzinca language is part of the 68 Voices, 68 Hearts project, a featured partner of the 2017 Mother Tongue Film Festival.

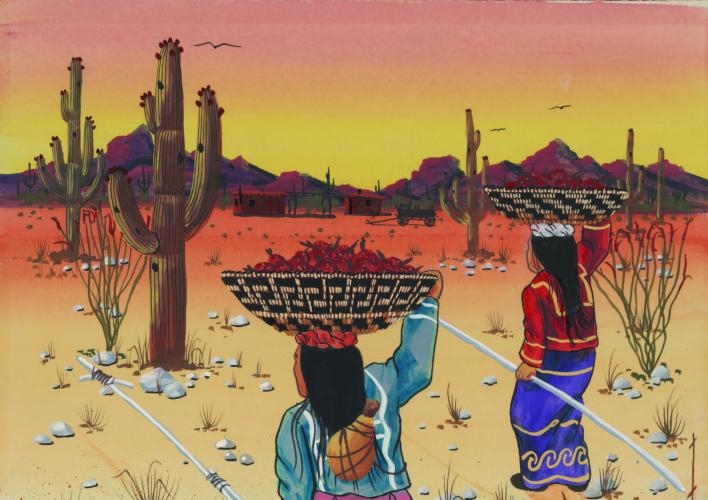

Harvest, 1992 by Michael M. Chiago (Tohono O’odham/Piipaash/Akimel O’odham), b. 1946. Paper, watercolor. Donated to NMAI by Ms. Patricia R. Wakeling in 2001 in memory of Dr. M. Kent Wilson. 25/8464

In some ways, the loss is even greater than the loss of an animal or plant species. According to Joshua A. Bell, anthropologist and curator of globalization at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, “Language diversity is one of humanity’s most remarkable achievements.” Indigenous people are the greatest source of this diversity and have the greatest stake in its preservation. Natives who can communicate in their own languages have an even richer appreciation of their own heritages and command a deeper understanding of their culture and communities. For the Native communities themselalves, fluency in Native languages complements efforts for greater social unity, self-sufficiency and identity. And for those outside these communities, sustaining this cultural diversity enriches all of us and helps greater cross-cultural understanding.

Declaring Emergency

International organizations recognize the crisis. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) publishes an Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger , edited by Christopher Moseley, and now in its third edition. UNESCO estimates that there are about 3,000 endangered languages worldwide, and the Atlas lists about 2,500 (among which 230 have become extinct since 1950). The interactive online version of this publication uses intergenerational language transmission to measure degrees of endangerment.

The U.S. government, major Native organizations and the Smithsonian itself have long been part of the fight to save Native languages, where possible marshaling resources to support tribes and Native speakers. Congress passed the Esther Martinez Native American Languages Preservation Act in 2006, providing support for Native language immersion and restoration programs. The Native American Languages Act of 1990 recognized that “the status of the cultures and languages of Native Americans is unique, and the United States has the responsibility to act together with Native Americans to ensure [their] survival.”

In late 2012, the Department of Health and Human Service’s Administration for Native Americans, the Department of Interior’s Bureau of Indian Education and the White House Initiative on American Indian and Alaska Native Education signed a Memorandum of Understanding to collaborate on promoting instruction and preservation of Native American languages. A Native American Languages Summit met in Washington, D.C. in September 2015, to celebrate 25 years of the Native American Languages Act. The Summit discussed long-term strategies for immersion language programs, trumpeted the work of youth-led efforts to revitalize languages and encouraged evidence-based research, education and collection of language documentation.

American Indian organizations are increasingly active. In 2010, The National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) declared Native languages to be in a state of emergency. This leading Indian advocacy organization declared that the crisis was the result of “longstanding government policies – enacted particularly through boarding schools – that sought to break the chain of cultural transmission and destroy American Indian and Alaska Native cultures.” Tribes understand that tribal identity depends on language and culture.

Other Native groups, such as the Association of Tribal Archives, Libraries and Museums (ATALM) and the American Indian Language Development Institute, also play a key role. ATALM convenes tribal cultural organizations in conferences and workshops, teaching Indian Country grassroots the importance of preserving historical documents, records, photographs, cultural materials and language materials and recordings. It values tribal librarians, archivists and museum specialists as guardians of “memory, language and lifeways.”

Recovering Voices

The Smithsonian itself has launched the Recovering Voices Initiative, one of the most important language revitalization programs in the world. As a collaborative program of the National Museum of Natural History, the National Museum of the American Indian and the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, Recovering Voices partners with communities worldwide. Its research links communities, museum collections and experts. In collaboration with communities, it is identifying and returning cultural heritage and knowledge held by the Smithsonian and other institutions

Smithsonian geologist and curator Timothy McCoy gives an example. “In the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, our language is being reintroduced to the community using written documentation collected a century or more ago. Language revitalization goes hand-in-hand with cultural revitalization, strengthening traditional ways of thinking about our people, place and relationships.”

The Recovering Voices Initiative ( www.recoveringvoices.edu ) also hosts film programs through its Mother Tongue Film Festival , an annual program now in its second year. Beginning on United Nations Mother Language Day in February, this year’s festival presented more than 30 films representing 33 languages from around the world. Films about language revitalization and efforts to teach younger generations their “mother tongues” are also part of this festival.

Teresa L. McCarty, a scholar who has taught at UCLA and Arizona State University, has written extensively about indigenous language immersion. She is deeply informed by an understanding that the world’s linguistic and cultural diversity is endangered by the forces of globalization, “which works to homogenize and standardize even as they segregate and marginalize.” Language immersion helps counter the pressures on children to communicate exclusively in English.

Although establishing immersion schools – along with the ongoing work required to operate them – requires resources often beyond the capacities of many tribes, there is a growing appreciation that language and cultural immersion approaches are necessary for Native communities to have fluent speakers in their own languages. NCAI has urged the federal government to provide funding, training and technical support.

Many approaches support cultural immersion in communities, from language instruction in early childhood education to bilingual and multi-lingual instruction in schools, to language camps and classes and childcare provided by speakers of the language. Programs include teacher training, family programming designed to support Native language use in the home, development of educational resources (e.g. lesson plans) and creative uses of technology on the Internet and social media. Use of Native languages in local radio, television and in local publications also helps. Some local efforts focus on novice learners, others on learners with prior language knowledge and proficient speakers. Many tribes have found creative ways to advance this work and engage their communities.

One of the most significant federal programs that support this work is a program of the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). Their Native American/Native Hawaiian Museum Services program provides funding to Indian tribes, Native Alaskan villages and corporations, and organizations primarily representing Native Hawaiians. These grants sustain heritage, culture and knowledge, including language preservation work.

Here are three programs supported by IMLS:

- In Neah Bay, Washington State, the Makah Cultural and Research Center is working to preserve oral histories and facilitate access to archival collections by digitizing and indexing fragile audio reel-to-reel tape, cassettes and handwritten transcriptions. These transcripts of the Makah language recordings originally created by elders and fluent speakers, provide avenues for tribal members to learn more about their history, culture and tradition.

- In Taholah, Wash., the Quinault Indian Nation is working to digitize a dictionary, complete with audio recordings and a searchable database, a comprehensive digital repository of their language. This work is critically important to preserving the extinct Tsamosan (Olympic) branch of the Coast Salish family of the Salishan language.

- In Salamanca, N.Y., the Seneca-Iroquois National Museum is developing a permanent, interactive exhibition titled “Ganönyö:g,” commonly referred to as the “Thanksgiving Address,” for its new Seneca Nation Cultural Center building. “Ganönyö:g” will visually represent each section of the speech with corresponding audio recordings featuring local Seneca Nation members speaking in the Seneca language. Through the exhibition, museum visitors will gain a deeper understanding of contemporary Seneca cultural beliefs, philosophy, origins and language.

The Modern Language Association gave strong support to the effort in its annual conference, honoring Ofelia Zepeda, the Tohono O’odham poet and scholar and other leaders in indigenous language research. Scholars presented papers and panels informed by a scholarly commitment to indigenous worldviews. The Association unveiled a Language Map aggregating data from the American Community Survey and the U.S. Census to display the locations and numbers of speakers of 30 languages commonly spoken in the United States. Their Language Map Data Center provides information about more than 300 languages spoken throughout the country.

Though the challenges can be overwhelming, Native languages are being preserved, and becoming part of the daily life of Native communities. As indigenous peoples communicate in their own languages, they honor their rich heritages and cultures.

John Haworth (Cherokee) is senior executive emeritus, National Museum of the American Indian – New York. He has taken a leadership role in the development of the Diker Pavilion for Native Arts and Cultures and Infinity of Nations (a major long-term exhibition currently on view at the GGHC), and serves on the advisory boards of the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation and the Association of Tribal Archives, Libraries and Museums.

© 2023 Smithsonian Institution

Preserving Native Languages in the Classroom

How native educators are creating immersive learning experiences that connect students with their indigenous language, culture, and lifeways..

Laura Zingg

Editorial Project Manager, One Day Studio

Andy Nez taught his Native language, Diné, for two years as a corps member in New Mexico, not far from where he grew up. He says the language represents much more than words—it’s a window into a uniquely Navajo worldview. Words, concepts, and ways of phrasing questions are rooted in relationships between people, land, and all living things.

Līhau Godden is the first in several generations in her family to speak fluent Hawaiian, ever since her mother and grandmother were required to learn English as the dominant language in school. As a 2015 Hawai’i corps member, Līhau returned to the same Hawaiian immersion school that she attended as a student, to help high schoolers gain mastery of their Native language.

These are just two examples of Teach For America alumni who are dedicated to preserving their Native languages for future generations of Indigenous students, in the classroom and beyond.

The most recent American Community Survey data collected from 2009 to 2013 found that there are 150 different Native North American languages collectively spoken by more than 350,000 people across the country. Native languages account for nearly half of the 350 total languages spoken in the United States. Yet, many of these languages are at risk of becoming extinct with only a small number of speakers remaining.

The reasons for this decline are complex and impact nearly every Indigenous language spoken in the U.S. They trace their origins back to when the first European explorers came to North America and the events that unfolded over centuries as Native peoples were displaced from their land by colonists and settlers.

The harmful effects of policies enacted during this time—such as requiring Native students to attend English-only boarding schools and the forced relocation and assimilation at the expense of eradicating Native language and culture—are still playing out today.

While there is still much work to be done, there have been great efforts since the Civil Rights era and over the past decades to restore Native languages and preserve Indigenous culture, specifically in the classroom—a place where Native children often feel invisible. This includes local and national efforts, such as the recent Senate approval to reauthorize the Esther Martinez Native American Languages Preservation Act , which supports language preservation and restoration programs for American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian students.

The vast majority of this work has happened at the grassroots level, led by Native leaders, activists, and educators who are most directly impacted by the loss of their language. Native communities are still working to undo laws enacted long ago, establishing community-based immersion schools, and partnering with education agencies to offer Native language in public schools.

Children who learn their Indigenous language are able to maintain critical ties to their culture, affirm their identity, and preserve important connections with older generations. There is also an additional benefit for students who learn their Indigenous language from a teacher who shares the same background, history, and culture.

Teach For America’s Native Alliance Initiative partners with Native communities across the U.S. to recruit more Native teachers into the classroom, particularly in the communities they are from. TFA alums, Līhau Godden and Andy Nez are part of a community of over 300 Native alumni who are helping Native students feel seen by reinforcing their language, culture, and stories in the classroom.

Nurturing the Next Generation of Navajo Speakers

One of the greatest Navajo teachings that Andy follows is, K'ézhnídisin dóó dadílzinii jidísin . It’s a Diné phrase that means “admire all living beings and respect all that is sacred.”

Andy is an enrolled member of the Navajo Nation and currently works for the Department of Diné Education in Window Rock, Arizona, as a senior education specialist. He says his grandparents played an important role in transmitting the Diné language to him. From a young age, Andy joined his grandmother and aunt in traditional Navajo seasonal ceremonies and learned Diné within the context of the changing landscape, the way his family had done for generations.

“Being able to grow up in that environment and converse with elders from 6 or 7 years old all the way into my early teenage years, that's how I picked up the Navajo language,” Andy says

Today, there are approximately 170,000 fluent Diné speakers. While Diné is one of the more widely-spoken Indigenous languages, the number of speakers has declined significantly over the last generation. Between 2000 and 2010, U.S. Census data found that the percentage of Navajos who spoke their Native language dropped from 76 to 51 percent, with younger generations among those who were least fluent.

While Andy doesn’t consider himself a completely fluent Diné speaker, he can read and write in the language and carry on conversations with the elders in his community. As an undergrad, he tutored young Navajo students and says his love of the Diné language and culture led him into teaching.

“We think about models or strategies or ways that we can pass on the language, which are important. But really, we should just speak the language whenever we can so that kids are familiarizing themselves.”

Senior Education Specialist, Department of Diné Education

New Mexico '14

Andy taught bilingual education in Diné and English for grades K-5 at Chee Dodge Elementary School in Ya-Ta-Hey, New Mexico, as a 2014 corps member. The school was named after Henry Chee Dodge, the first Navajo tribal chairman. While Andy taught primarily Navajo students, he says they had a range of familiarity with the language. Some could speak in full sentences, while others were only familiar with a few specific words.

Andy helped his students build fluency by building conversation into his lessons. Andy recalls one of his favorite projects, in which students wrote a Diné word describing themselves or their mood on a yellow sticky note. They arranged their notes to form a giant ear of corn, representing their interconnectedness to each other and the earth. They then practiced how to ask the question, “How do you feel?”

“We talked about how our identity is important, and how we are all part of a community that looks out for each other,” Andy says.

When students learned about the Navajo Code Talkers who helped the U.S. Army create secret intelligence reports during World War II, they got to practice using Diné to translate their own coded messages.

One of the biggest challenges that Andy ran into was a lack of Navajo being spoken at home, particularly among those who are bilingual, where it’s easy to fall back on English. In order to engage his students’ families in speaking the language, Andy created homework assignments that required students to collaborate with their parents, or a community member or talk with an elder in Diné.

“We think about models or strategies or ways that we can pass on the language, which are important,” Andy says. “But really, we should just speak the language whenever we can so that kids are familiarizing themselves.”

Andy says learning the Diné language helps students stay rooted in their identity and understand their place in the world. He believes that the language has the power to heal the hurts he sees in his community and restore one’s connection with the stories and traditions of the Navajo people.

“Diné language is not just words and sounds. It's teaching the child to appreciate life and to respect their surroundings and all living beings,” Andy says. “When you speak Navajo, you have a sense of respect and a sense of self, and you carry that forward.”

Andy is thinking big about the role he wants to play in preserving the Diné language in the future. He’s currently working on a Ph.D. in educational leadership at Grand Canyon University. He is looking forward to creating Navajo-related programs, teaching gender and sexuality courses through a Navajo cultural lens, and publishing articles in Diné. He says he plans to get more involved in politics and plans to run for Navajo Nation Council in 2022.

Andy has done voice-overs and translation work for various projects, such as a recent documentary called Moroni for President, about a young Navajo man who campaigns to be the first openly gay president of the Navajo Nation. In the meantime, he’s started a series of online lessons called Diné Language in 10 Seconds, in which he uploads videos of himself to his Facebook page, teaching common phrases that can be used at home or in the workplace.

“So as long as I'm on earth, there's going to be a Navajo language speaker, “ Andy says. “That's just my passion and I will continue to do that.”

Teaching Culturally Relevant Science in Hawaiian

When the U.S. government annexed Hawai’i as a territory in 1898, the Hawaiian language was banned from being taught in schools. By the 1980s, English had replaced Hawaiian as the primary language spoken on the islands. Nearly all of the native Hawaiian speakers who were under the age of 18 could fit into a single classroom.

But that all changed in the 1970s, when Hawaiian language activist Larry Kimura led the effort to convince Hawaii’s Department of Education to approve the creation of Hawaiian immersion schools. The campaign was successful, however, the government did not provide any resources or support. The work of creating the schools was left to community members

As a student, Līhau Godden attended one of these immersion schools, Ke Kula ʻo ʻEhunuikaimalino, located in Kona. Then, in 2015 she returned to her alma matter to teach as a corps member.

Because Hawaiian language instruction was banned from schools for several generations, Līhau says she didn’t grow up speaking Hawaiian with her family at home. (Her mother is Hawaiian and her father is not). However, Līhau’s mother wanted Līhau and her siblings to grow up knowing how to speak Hawaiian. In addition to sending her children to the Ke Kula ʻo ʻEhunuikaimalino immersion school, Līhau’s mother also joined the movement to restore Hawaiian language by helping to establish a Hawaiian immersion day-care center.

After college, Līhau returned to Kona and began volunteering at Ke Kula ʻo ʻEhunuikaimalino, helping administer Hawaiian language tests. The school had a shortage of Hawaiian-speaking teachers so Līhau applied through Teach For America, which has a partnership with the school.

“It may seem serendipitous, but it was the perfect fit,” Līhau says.

“Whenever I meet kids who go to immersion schools, I always speak to them in Hawaiian so they can see that there are people out there who use it. It allows us to stay connected to our values and keep stories from our ancestors alive.”

Līhau Godden

Hawai'i '15

Līhau taught 7-12-grade science, entirely in Hawaiian. While Hawaiian immersion schools have come a long way, Līhau says it is still rare to find teachers who are fluent in Hawaiian and also have specific subject matter expertise.

Līhau’s students came in with a range of fluency in Hawaiian. During her first year of teaching, many students were frustrated with the steep learning curve. They were not only learning new science concepts, but they were learning them entirely in Hawaiian.

“It's a lot of new vocabulary,” Līhau says. “Even for the kids who have been speaking Hawaiian, since they were in kindergarten, if they haven't learned those higher-level science vocabulary words in Hawaiian, they're kind of lost too.”

Līhau worked to ground her lessons in Hawaiian culture, helping her students make connections between science, Hawaiian history, and folklore. When learning about the solar system, Līhau wove in traditional Hawaiian stories about the role that the moon phases play in helping people keep time and mark specific rituals throughout the year. They talked about the Hawaiian star compass and how their ancestors used stars to navigate while traveling by sea. During chemistry class, students explored the chemical compounds found in traditional Hawaiian medicine.

“There is so much science baked into the culture,” Līhau says. “You're still touching on all these different science standards and science concepts, but approaching it from a different perspective.”

Līhau says so much of the Hawaiian language and stories are rooted in the idea that everything shares a connection back to the land. The Hawaiian word for land is Āina. But it can also be broken down into words that refer to being fed or nourished, such as ʻai ʻana which means “to eat.” By learning the language, students are also able to view the world through a Hawaiian perspective.

“Through the language, you're able to access cultural protocol and stories and songs,” Līhau says. “Hawaiian is so poetic, and there are so many double meanings that you don't ever fully understand from just the translation.”

During the four years that Līhau taught at Ke Kula ʻo ʻEhunuikaimalino, she was part of a school-wide effort to focus on speaking Hawaiian throughout the school day. She helped the school implement a class in which students were grouped by speaking level, rather than grade level, and worked with her school team to fill in gaps in the school’s Hawaiian-language science curriculum. She also helped develop culturally relevant science standards for immersion schools that were grounded in Hawaiian culture.

“My students made a lot of improvement as the result of teachers and students holding each other accountable for speaking more Hawaiian,” she says. “By the third year, hardly any of my students spoke English to me.”

In 2015 Līhau traveled with her students to Washington, D.C., to perform at TFA’s 25th-anniversary summit. She and her students performed a traditional hula in front of 10,000 people. While Līhau says the experience was a bit nerve-wracking, it was an important moment for her students to be seen and to share their stories in their Native language.

Līhau now lives near where she taught and helps support her family’s business. She’s passionate about preserving the Hawaiian language and contemplating what her next steps will be. For now, she says the most important thing is to normalize the language by speaking it as much as possible in her day-to-day life.

“Whenever I meet kids who go to immersion schools, I always speak to them in Hawaiian so they can see that there are people out there who use it,” Līhau says. “It allows us to stay connected to our values and keep stories from our ancestors alive.”

Sign up to receive articles like this in your inbox!

Thanks for signing up!

Content is loading...

- Families & Communities

- Native Community

Native Language

Related Stories

19 Resources and Ideas to Celebrate the MLK Day of Service

Here are some ways you can serve–virtually or in person–on MLK Day.

The TFA Editorial Team

Season 2, Bonus Episode 2: Not Just Another Building

During an educators' meeting in Memphis, KeAsia Norman, a BIPOC educator and aspiring school leader said, “If a school isn’t actively engaged in the community, it’s just another building.” In this special episode, recorded live at SXSW EDU, host Jonathan Santos Silva is joined by a panel of innovative BIPOC educators and Teach For America alumni passionate about radically re-imagining the role of school within communities. Through their unique insights, we learn how to transform school buildings into vital community spaces that better reflect their students’ and staff’s needs.

Hosted by Jonathan Santos Silva

Season 2, Episode 3: A Black Man’s Classroom

Host Jonathan Santos Silva speaks with leaders and educators from Brothers Liberating Our Communities (BLOC) in Kansas City, MO about making teaching a sustainable career for Black men.

- Our Mission

Incorporating Students’ Native Languages to Enhance Their Learning

Teachers don’t have to speak students’ first languages to make room for these languages in middle and high school classrooms.

I loved my kindergarten teacher, Mrs. Phillips. I will always remember how safe and welcomed she made me feel. I would watch her give instructions in English, not understanding a word of it, and I would copy what my classmates did. When Mrs. Phillips came over, I would speak unabashedly to her in Vietnamese. She would pay careful attention to my gestures to decipher my message and praise me with a smile in celebration of my work.

You do not need to speak the same language to feel someone’s love. I also don’t remember her yelling at me to speak English. What would be the use of finger waving and saying, “Speak English!” when Vietnamese was the only language I knew at the time?

As we embrace culturally responsive and culturally sustaining pedagogies , we are abandoning destructive English-only policies. Unfortunately, English-first policies often place other languages last—and, by extension, the cultures represented by non-English languages.

What messages are multilingual learners (MLs) internalizing when the only sanctioned language they hear in schools is English? With an additive approach to language , MLs can learn another language without having to subtract their existing ones.

3 Ways Multilingualism Helps Students Learn

1. Mastering content. I used to think that students had to learn content in English. However, a concept like tectonic plates remains the same regardless of the language. Now when I have my students complete a research project, I make sure to tell them that using an article or video in another language is absolutely appropriate.

When my 10th graders were learning about how Covid-19 impacted the Thai economy, many of them used articles written in Thai, as they provided more nuanced and relevant details. In this way, we celebrated the students’ multilingualism and dissolved the language hierarchy myth by showing students that content does not have to be learned in only one language.

2. Collaborating. Learning content by reading articles in students’ languages works for students who are literate in other languages. For students who can only speak and understand their heritage language, learning content is still possible while collaborating with classmates who speak the same languages.

For example, when I had my students read an article in English about land subsidence, I had them pause at the end of each paragraph to talk about and process what they had just read. For many of my students, it was easier to understand the article when they talked about it in their Chinese, Thai, or Korean peer groups. Since learning is a social experience , let’s have students learn using all of their languages.

3. Communicating ideas. Often, MLs have ideas swirling in their minds but struggle to formulate them in English. To support these students, we can have them first brainstorm, organize, and outline in their heritage languages. Forcing students to write or speak only in English is like putting speed bumps in their way. The goal is to have idea generation and to connect concepts at this stage, not English output. Once they have all of their ideas organized using their languages, we can support students to transfer these ideas into English.

With these three approaches to heritage language integration, we see that teachers do not have to know all of the languages their students speak. All teachers need to do is see students’ multilingualism as an asset that extends learning and sustains students’ connections to their communities. As MLs engage more through their languages, our eyes are opened to their potential.

Yes, many of us work in places that require English output on summatives, and state assessments are also in English. However, this does not mean that everything we do as teachers has to be monolingual. Think of languages as tools. If we only have a hammer, there’s a limit to what we can construct. When we are free to use all of the linguistic tools from our toolbox, imagine all of the things that we can create.

Lastly, even if we cannot speak our students’ languages, by welcoming them to use those languages we create a space where assets and cultures are recognized and honored. Years from now, when MLs may have forgotten what we’ve taught, they will still recall with affection how we made them feel. Start with embracing all languages in class.

Calgary Journal

Voices: How losing my native language made me struggle with my identity

Share this:.

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

Sitting alone in the change room, the only thing I could hear was my heritage language flying around me. My teammates, people who I should be able to talk to and grow relationships with, seemed to be in a world completely separate from the one I was in.

Going through the motions, warming up and sitting on the bench, I couldn’t communicate with anyone — which was detrimental when I was playing a team sport like soccer.

I was able to speak Spanish fluently when I was very young, as both of my parents spoke to me in the language. Both immigrants from Chile, it was very important to my parents and grandparents to instil elements of their home in the first Canadian member of the family.

I tell people I am Chilean, but only through blood. I have never been to Chile, nor do I even speak the language, even though both of my parents were born there. I feel the most Canadian when I am hanging out with fellow Chileans.

Preserving mother tongues: Why children of immigrants are losing their languages

Losing my mother tongue has had a major impact on my life. I feel a disconnect with my family’s culture. Having meaningful conversations with family members who only speak Spanish is practically impossible.

Children of immigrants losing their parents’ language is not exclusive to me. Second generation immigrants are more likely to lose their first language than to remain bilingual, according to a study by Claudio Toppelberg and Brian Collins that looked at language in immigrant children.

Rennie Lee, a researcher at the University of Queensland who specializes in the social sciences of immigration, says maintaining heritage languages as a child is hard, especially in Canada.

“It’s really hard and I can feel those tensions, the barriers that I’m up against.” Rennie Lee, Researcher at the University of Queensland

“If their language of instruction, the kind of language they communicate with their friends, is in English, it’s really hard to maintain an immigrant language or their parents native tongue.”

Lee is a second generation immigrant herself and she is able to speak her heritage language of Cantonese. But passing on the language to the next generation has proven to be a struggle.

“I now have a son who’s three and I’m trying to speak Cantonese with him, but it is really challenging. Even I, as someone who’s studied this and really tried to preserve my parents language with him,” she says.

“It’s really hard and I can feel those tensions, the barriers that I’m up against.”

Much like Lee, my parents are able to speak my heritage language. When I was old enough to go to school, I asked for them to speak to me in English to better fit in with my peers.

I have countless memories of people learning of my heritage and attempting to speak to me in Spanish, only for me to provide nothing but a confused face and a jaded apology for being monolingual. It pains me to see their excited face slowly fade, and in some cases, even turn into something that feels judgemental.

However, I do not feel any resentment towards my parents. How were they supposed to know? With navigating having children and balancing everything that it takes to provide for your child, language is something that seems to just fall through the cracks. Despite this, there are calls from Toppelberg and Collins in their research to treat bilingualism in a child with more importance.

Benefits of being bilingual

The study states, “Educational, clinical and family efforts to maintain and support the development of competence in the two languages of the dual language child, may prove rewarding in terms of long term wellbeing and mental health, educational and cognitive benefits.”

As I got older and prepared to enter an increasingly competitive job market, I could not help but feel that an opportunity was missed in my childhood to become fluent in Spanish.

One study by Patricia Gandara on the economic value of bilingualism concluded that, “Employers increasingly prefer employees who can reach a wider client base and work collaboratively with colleagues across racial, ethnic, and cultural lines.”

Despite losing my ability to speak Spanish in early childhood, the foundations I established can help me in my attempt to relearn Spanish as an adult.

In a paper on childhood language memory in adult heritage language relearners, it says “Our findings indicate that very early childhood language memory (i.e., from the first year of life) remains accessible in adulthood even after a long period of disuse of the language.”

These findings inspire me to invest time into bettering myself and reclaiming what was lost at a young age. I am determined to find my culture and learn the language that has eluded me my entire life. I have decided to take Spanish language and hispanic culture as a minor, and I am currently enrolled in both Spanish language and Spanish culture classes at Mount Royal University.

Report an Error or Typo

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

current events conversation

Teenagers on What Their Families’ Native Languages Mean to Them

“I’m not that embarrassed,” one student said of his accent, “because it’s a flex to know multiple languages.”

By The Learning Network

Do you speak any languages besides English at home? Did your parents, grandparents or great-grandparents when they were growing up? Do you or anyone else in your family have what might be considered an accent?

In the guest essay “ ‘Don’t Lose Your Accent!’ ” Ilan Stavans urges newcomers to the United States to embrace their “immigrant verbal heritage.” He writes that “far from undermining the American experiment, immigrants enhance our culture by introducing new ideas, cuisines and art. They also enrich the English language.”

What role does your family’s native tongue play in your life? we asked students. We heard from young people who speak Russian, Telugu, Spanish, Farsi, Cantonese, Twi, Quichua, Arabic and Polish. We heard from those who took pride in their family’s multilingualism and from those who were made to feel ashamed of it, but eventually came to cherish it. We also heard from several students who never had the chance to learn their relatives’ native tongue and regretted it.

Benjamin, a student from San Jose, Calif., who grew up speaking English and Mandarin, summed up a sentiment many students expressed about their linguistic heritages: “Back in elementary school, I was often told that I had an accent, but now that I think about it, I’m not that embarrassed, because it’s a flex to know multiple languages.” Read on to see what else teenagers had to say about what their families’ native languages mean to them.

Thank you to all those who joined the conversation on our writing prompts this week, including students from Casa Roble High School in Orangevale, Calif .; Union County Vocational-Technical High School in Scotch Plains, N.J. ; and W.T. Clarke High School in Westbury, N.Y.

Please note: Student comments have been lightly edited for length, but otherwise appear as they were originally submitted.

I bring my culture and language with me wherever I go.

I live in the United States, but my parents immigrated here from India. My parents speak a variety of Indian dialects, and English was not a language they learned until their late teenage years.

I have been exposed to many languages from a young age and being able to pick up on these languages has only benefited me. Sure, there were times in elementary school where I would be told I had incorrect grammar, but for the most part, knowing other languages helped me connect with other children of immigrants. It also helped me connect with my older family, although I have always been aware that I am not quite “Indian” enough.

Also, because of the fact that I know Marathi and some Hindi (the Indian dialects common in Mumbai and Pune), I am able to enjoy movies and music from more than just the English streams. Some of my favorite movies are Marathi movies.