- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Facebook is a harmful presence in our lives. It’s not too late to pull the plug on it

Undaunted by scandals, the social media giant plans to tighten its grip on our everyday activities. We don’t have to just submit

F acebook is in perpetual crisis mode. For years now, the company has confronted waves of critical scrutiny on issues caused or exacerbated by the platform. Recent revelations have lengthened the charge sheet.

That list includes the mass data collection and privacy invasion by Cambridge Analytica ; the accusations of Russian interference during the 2016 presidential election; unrestrained hate speech, inciting, among other things, genocide in Myanmar ; the viral spread of disinformation about the coronavirus and vaccines, with Joe Biden proclaiming about Facebook and other social media platforms: “They’re killing people”. Add to that Facebook Marketplace: with a billion users buying and selling goods, ProPublica found a growing pool of scammers and fraudsters exploiting the site, with Facebook failing “to safeguard users”.

The latest wave of investigative reporting focused on the company, meanwhile, comes from the Wall Street Journal’s Facebook Files series. After pouring over a cache of the company’s internal documents, the WSJ reported that “Facebook’s researchers have identified the platform’s ill effects”. For instance, the company downplayed findings that using Instagram can have significant impacts on the mental health of teenage girls. Meanwhile, it has been implementing strategies to attract more preteen users to Instagram. The platform’s algorithm is designed to foster more user engagement in any way possible, including by sowing discord and rewarding outrage . This issue was raised by Facebook’s integrity team, which also proposed changes to the algorithm that would suppress, rather than accelerate, such animus between users. These solutions were struck down by Facebook’s chief executive, Mark Zuckerberg, because he prioritised growing engagement above other objectives.

What’s more, the WSJ reported, Facebook employees “ raised alarms ” about drug cartels and human traffickers in developing countries using the platform, but the company’s response has been anaemic. Perhaps because executives are, yet again, hesitant to impede growth in these rapidly expanding markets.

This is consistent with claims by Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen, who said at the weekend, in an interview with 60 Minutes , “Facebook, over and over again, has shown it chooses profit over safety.” It also emerged that Haugen has filed at least eight complaints with the US financial watchdog over Facebook’s approach to safety. Haugen testified before the US Senate on Tuesday, backing up her revelations. “I’m here today because I believe Facebook’s products harm children, stoke division and weaken our democracy,” she said. “The company’s leadership knows how to make Facebook and Instagram safer, but won’t make the necessary changes because they have put their astronomical profits before people.” We shouldn’t be surprised that making money hand over fist is any company’s primary motivation. But here we have further evidence that Facebook is a uniquely socially toxic platform.

Despite the executive team’s awareness of these serious problems, despite congressional hearings and scripted pledges to do better, despite Zuckerberg’s grandiose mission statements that change with the tides of public pressure, Facebook continues to shrug off the great responsibility that comes with the great power and wealth it has accumulated.

Each surging wave builds on the last, hitting Facebook even harder, enveloping it in scandal after scandal. In response, the company has decided to go on the offensive – rather than truly address any of its problems.

In August, Zuckerberg signed off on an initiative called Project Amplify , which aims to use Facebook’s news feed “to show people positive stories about the social network”, according to the New York Times . By pushing pro-Facebook stories, including some “written by the company”, it hopes to influence how users perceive the platform. Facebook is no longer happy to just let others use the news feed to propagate misinformation and exert influence – it wants to wield this tool for its own interests, too.

With Project Amplify under way, Facebook is mounting a serious defence against the WSJ Facebook Files. In an article posted on Facebook Newsroom by Nick Clegg, Facebook’s vice-president of global affairs, , accusations of “deliberate mischaracterisations” by the WSJ reporters are lobbed in without supplying any specific details or corrections. Similarly, in an internal memo sent by Clegg to pre-empt Haugen’s interview, Clegg rejected any responsibility for Facebook being “the primary cause of polarisation”, blamed the prevalence of extreme views on individual bad actors like “a rogue uncle” and provided talking points for employees who might “get questions from friends and families about these things”.

It’s all spin, with no substance. A trained politician deflecting accusations while planting seeds of doubt in the public’s mind without acknowledging or addressing the problems at hand.

In another response to the WSJ, Facebook’s head of Instagram, Adam Mosseri, made a strange analogy between social media and cars: “We know that more people die than would otherwise because of car accidents, but by and large, cars create way more value in the world than they destroy,” Mosseri said. “And I think social media is similar.” Mosseri can no longer deny that platforms like his are forces for destruction. His tactic is to convince us that a simple cost-benefit analysis comes out in his favour. He happens to elide the fact that cars cause more than crashes; they are also responsible for systemic social and environmental consequences at every level. Of course, this is exactly the kind of self-interested myopia we should expect from a tech executive under fire.

Beyond pushing back against critical reporting, however, an initiative like Project Amplify should be understood as Facebook attempting to pave the way for its deeper penetration into every facet of our reality. After all, when asked last year by Congress why Facebook is not a monopoly, Zuckerberg said it’s because he views all possible modes of “ people connecting with other people ” as a form of competition for his business. And if we know anything about Facebook, they are very good at capturing market share and crushing competitors – no matter what it takes.

Facebook needs users to form an intimate relationship with the platform. In quick succession this summer, it announced two new products that represent the company’s next planned phase of existence – both its own and ours.

First is the “ metaverse ”. Named after an explicitly dystopian sci-fi idea , the metaverse is, for now, pitched as essentially a virtual reality office – accessed through VR goggles like Facebook Oculus – where you go to see colleagues, attend meetings, and give presentations without having to leave home. Zuckerberg proclaimed that over the next five years, Facebook “will effectively transition from people seeing us as primarily being a social media company to being a metaverse company.”

Second is Ray-Ban Stories, Facebook’s attempt to succeed where Google Glass failed. Ray-Ban Stories are pitched as a frictionless way to stay constantly connected to Facebook and Instagram without that pesky smartphone getting in the way. Now you can achieve the dream of sharing every moment of your day with Facebook – and the valuable data produced from it – without ever needing to think about it.

Importantly, access to both kinds of reality – virtual and augmented – are mediated by Facebook. The executives at Facebook would like you to believe that the company is now a permanent fixture in society. That a platform primarily designed to supercharge targeted advertisements has earned the right to mediate not just our access to information or connection but our perception of reality. And Facebook’s aggressive attempts to combat any scepticism, combined with its reality-shaping ambitions, shows how desperate it is to convince us to accept the social poison it peddles and ask for more.

Days before Facebook’s latest congressional hearing – this time on the mental impacts of Instagram on teenagers – Mosseri announced his team was pausing Instagram Kids, a service aimed at people under 13 years old, and developing “parental supervision tools”. It seems yet again that they will do the bare minimum only when forced to do so. Speaking about this change of direction in her Senate hearing, Haugen was sceptical: “I would be sincerely surprised if they do not continue working on Instagram Kids, and I would be amazed if a year from now we don’t have this conversation again.”

For Facebook, all this negative attention amounts to an image problem: bad publicity that can be counteracted by good propaganda. For the rest of us, this is indicative that Facebook doesn’t just have a problem; Facebook is the problem. Ultimately, an overwhelming case is growing against Facebook’s right to even exist, let alone continue enjoying unrestricted operation and expansion.

We must not forget that Facebook is still young. It was founded in 2004, but didn’t really come into itself, becoming the behemoth we know today, until going public in 2012, buying Instagram for $1bn (£760m) that same year and then acquiring WhatsApp for $19bn two years later. True to its original informal motto – “Move fast and break things” – Facebook has wasted no time wreaking a well-documented path of destruction.

When Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp temporarily went offline this week due to a technical problem , we saw just how dependent we have already become on these services for so many everyday activities. It was a shock to suddenly be without them. The company would probably see this as evidence that our lives are too intertwined with its services for them to ever go away. But, as the company has proven time and time again, our interests and its interests are rarely aligned. We should instead recognise that allowing a rapacious company to design and own critical infrastructure with zero accountability is the worst of all possible options.

If its executives want to compare social media to cars, then at the very least this dangerous technology must be subjected to the same level of heavy regulation and independent oversight as the automotive industry. Otherwise, Facebook must be reminded that it’s not too late for the public to pull the plug on this social experiment gone wrong. Right now, almost any alternative would be better.

Jathan Sadowski is a research fellow in the emerging technologies research lab at Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

- Social networking

- Social media

- Digital media

Most viewed

Smart. Open. Grounded. Inventive. Read our Ideas Made to Matter.

Which program is right for you?

Through intellectual rigor and experiential learning, this full-time, two-year MBA program develops leaders who make a difference in the world.

A rigorous, hands-on program that prepares adaptive problem solvers for premier finance careers.

A 12-month program focused on applying the tools of modern data science, optimization and machine learning to solve real-world business problems.

Earn your MBA and SM in engineering with this transformative two-year program.

Combine an international MBA with a deep dive into management science. A special opportunity for partner and affiliate schools only.

A doctoral program that produces outstanding scholars who are leading in their fields of research.

Bring a business perspective to your technical and quantitative expertise with a bachelor’s degree in management, business analytics, or finance.

A joint program for mid-career professionals that integrates engineering and systems thinking. Earn your master’s degree in engineering and management.

An interdisciplinary program that combines engineering, management, and design, leading to a master’s degree in engineering and management.

Executive Programs

A full-time MBA program for mid-career leaders eager to dedicate one year of discovery for a lifetime of impact.

This 20-month MBA program equips experienced executives to enhance their impact on their organizations and the world.

Non-degree programs for senior executives and high-potential managers.

A non-degree, customizable program for mid-career professionals.

Credit: Roman Martyniuk/Unsplash

Academic study reveals new evidence of Facebook's negative impact on the mental health of college students

MIT Sloan Office of Communications

Sep 27, 2022

Researchers created control group by comparing colleges that had access to the platform to colleges that did not during the first two years of its existence

CAMBRIDGE, Mass., Sept. 27, 2022 — A new study led by researchers from Tel Aviv University, MIT Sloan School of Management and Bocconi University reveals new findings about the negative impact of Facebook on the mental health of American college students. The study focuses on Facebook's first two-and-a-half years (2004-2006), when the new social network was gradually spreading through academic institutions, and it was still possible to detect its impact by comparing colleges that had access to the platform to colleges that did not. The findings found a rise in the number of students who had access to Facebook reporting severe depression and anxiety (7% and 20% respectively).

The study was led by Dr. Roee Levy of the School of Economics at Tel Aviv University, Prof. Alexey Makarin of MIT Sloan School of Management, and Prof. Luca Braghieri of Bocconi University. The paper is forthcoming in the academic journal American Economic Review.

"Over the last fifteen years, the mental health trends of adolescents and young adults in the United States have worsened considerably," said Prof. Braghieri. "Since such worsening in trends coincided with the rise of social media, it seemed plausible to speculate that the two phenomena might be related."

The study goes back to the advent of Facebook at Harvard University in 2004, when it was the world's first social network. Facebook was initially accessible only to Harvard students who had a Harvard email address. Quickly spreading to other colleges in and outside the US, the network was finally made available to the general public in the US and beyond in September 2006.

The researchers studied Facebook's gradual expansion during those first two-and-a-half years to compare the mental health of students in colleges that had access to Facebook with that of students in colleges that did not have access to the platform at that time. Their methodology also took into account any differences in mental health over time or across colleges that were not related to Facebook. This approach enabled conditions similar to those of a 'natural experiment' - clearly impossible today now that billions of people use many different social networks.

Prof. Makarin said, "Many studies have found a correlation between the use of social media and various symptoms related to mental health. However, so far, it has been challenging to ascertain whether social media was actually the cause of poor mental health. In this study, by applying a novel research method, we were able to establish this causality."

The study combined information from two different datasets: the specific dates on which Facebook was introduced at 775 American colleges, and the National College Health Assessment (NCHA), a survey conducted periodically at American colleges.

The researchers built an index based on 15 relevant questions in the NCHA, in which students were asked about their mental health in the past year. They found a statistically significant worsening in mental health symptoms, especially depression and anxiety, after the arrival of Facebook:

- a rise of 7% in the number of students who had suffered, at least once during the preceding year, from depression so severe that it was difficult for them to function;

- a rise of 20% in those who reported anxiety disorders;

- an increase in the percentage of students expected to experience moderate to severe depression - from 25% to 27%;

- a rise in the percentage of students who had experienced impairment to their academic performance due to depression or anxiety - from 13% to 16%.

Moreover, the impact of Facebook on mental health was measured at 25% of the impact of losing a job, and 85% of the gap between the mental states of students with and without financial debt – with loss of employment known of employment and debt known to strongly affect mental health.

Dr. Levy said, "When studying the potential mechanisms, we hypothesized that unfavorable social comparisons could explain the effects we found, and that students more susceptible to such comparisons were more likely to suffer negative effects. To test this interpretation, we looked at more data from the NCHA. We found, for example, a greater negative impact on the mental health of students who lived off-campus and were consequently less involved in social activities, and a greater negative impact on students with credit card debts who saw their supposedly wealthier peers on the network."

"We also found evidence that Facebook had changed students' beliefs about their peers: more students believed that others consumed more alcohol, even though alcohol consumption had not changed significantly. We conclude that even today, despite familiarity with the social networks and their impact, many users continue to envy their online friends and struggle to distinguish between the image on the screen and real life."

About the MIT Sloan School of Management

The MIT Sloan School of Management is where smart, independent leaders come together to solve problems, create new organizations, and improve the world. Learn more at mitsloan.mit.edu .

Related Articles

Positive and negative effects of Facebook

- December 18, 2017

- General , Technology

Facebook is a social networking service working under the aegis of a for-profit organization, Facebook Inc., whose chairman and CEO is Mark Zuckerberg, co-founder of this large network. Confined to a college campus in Massachusetts in 2004, today, it has footage in most of the parts of the world. The services Facebook provides include cost-free registration, sending friend requests to other users, posting and sharing status, photos, and videos, and a free messenger. As of 2017, the users constitute 27% of the global population. In addition, the widespread smartphone usage and accessibility of the internet has enhanced its popularity. Recently, where Facebook is expanding its coverage by modifying its services, it attracted notable attention from the world community following its alleged misuse.

Positive effects of Facebook:

Facebook has changed the definition of the social world.

Brings equality

Facebook provides neutral facilities and services to every person on this planet. Celebrities, national leaders, and wealthy businessmen don’t own special treatment or a classified page or an account that a few people can access. A common citizen and a high-class person, both access, post, and share in the same way.

Large social circle

The existence of a networking site like Facebook benefits an individual in staying in contact with the known and friends for a long and lifetime. Whenever someone needs help or an advice, a friend is a mere second away, because of Facebook. Facebook provides an opportunity to establish contact with people of similar interests, which can be helpful in professional life and self-development.

Digital campaigns

Social media has become commonplace to gain the attention of government toward any social cause and illegal activity. Facebook users show their support by sharing an incident or posting a unique display picture. Reports show that it takes a day for such an issue to reach Parliament house, where an issue took weeks and months for the same in past. Also, Facebook has lowered the burden of police, as users help in finding missing children or a culprit by sharing videos and photos.

Increases awareness

Internet constitutes numerous news websites and the followers are comparatively lower. These websites use the Facebook platform to inform and spread everyday reporting in the different parts of the world. In this way, Facebook makes every user a knowledgeable and intellectual person.

Negative effects of Facebook:

The digital world of Facebook has consumed the normal and healthy living.

Using a Facebook account isn’t a group thing but a sole participation. The willingness to stay in contact with the friends and the world events glued a user to the Facebook via cell phones . This has led to the isolation among youngsters, who feel comfortable and content with a virtual living in a digital world. It, in turn, affects the relationships and mandatory responsibilities in the physical world.

Live crimes

Since the Facebook introduced ‘live’ option in its application, the live crimes have increased where a user records a robbery or sexual harassment through an account. The hunger of publicity and maximum followers have influenced users to perform these inhumane activities. As a criminal can make an anonymous account or hack someone else’s account, police find it difficult to reach the real culprit.

Unstable relationships

Today, youngster find it easy and interesting to make friends on Facebook. They might develop a strong bond with someone and at the same time, a couple might argue regarding posted comments on social media. Figures show that many youngsters face breakups on Facebook. The way people end their relationships despite being physically distant and in a different situation and circumstances have proved a major stain on the social culture that humans have been developing since ages.

24*7 open application impacts normal lives of people to a great extent. The lack of concentration in a task someone is performing in the physical world is a major negative effect of continuous Facebook availability. Facebook disturbs the study time, family and friends get-together. It’s usage in late night hours raise insomnia, eye-stress, and other health issues among users. And the urge of knowing ‘what’s new’ leads to Facebook usage in working hours, which, further, impact the effective delivery of assignments and job, altogether.

Facebook is a revolution itself, which provided a single platform to every human being on this earth to communicate and share their culture. One can’t reverse the hold it possesses in this modern world in coming years. At the same time, many countries have banned the Facebook usage following the fake news and extensive violence on its services. To eliminate these limitations, human behavioral changes is must and government can contribute by creating an awareness among citizens regarding ethical use of the Facebook.

Related Posts

Negative effects of Instagram

- August 4, 2018

Negative effects of online shopping

- August 1, 2018

Negative effects of cursing

- July 28, 2018

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Name *

Email *

Add Comment *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Post Comment

How Facebook is changing our social lives

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Christian Jarrett

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Media, Entertainment and Sport is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, media, entertainment and sport.

With over a billion users, Facebook is changing the social life of our species. Cultural commentators ponder the effects. Is it bringing us together or tearing us apart? Psychologists have responded too – Google Scholar lists more than 27,000 references with Facebook in the title. Common topics for study are links between Facebook use and personality, and whether the network alleviates or fosters loneliness. The torrent of new data is overwhelming and much of it appears contradictory. Here is the psychology of Facebook, digested:

Who uses Facebook?

According to a survey of over a thousand people, “ females, younger people, and those not currently in a committed relationship were the most active Facebook users “. Regarding personality, a study of over 1000 Australians reported that “[FB] users tend to be more extraverted and narcissistic , but less conscientious and socially lonely, than nonusers “. A study of the actual FB use of over a hundred students found that personality was a more important factor than gender and FB experience , with high scorers in neuroticism spending more time on FB. Meanwhile, extraverts were found to have more friends on the network than introverts (“the 10 per cent of our respondents scoring the highest in extraversion had, on average, 484 more friends than the 10 per cent scoring the lowest in extraversion”).

Other findings add to the picture, for example: greater shyness has also been linked with more FB use . Similarly, a study from 2013 found that anxiousness (as well as alcohol and marijuana use) predicted more emotional attachment to Facebook .

There’s also evidence that people use FB to connect with others with specialist interests, such as diabetes patients sharing information and experiences , and that people with autism particularly enjoy interacting via FB and other online networks.

Why do some people use Twitter and others Facebook?

Apparently most people use Facebook “ to get instant communication and connection with their friends ” (who knew?), but why use FB rather than Twitter? A 2014 paper suggested narcissism again is relevant, but that its influence depends on a person’s age: student narcissists prefer Twitter, while more mature narcissists prefer FB . Other research has uncovered intriguing links between personality and reasons for using FB. People who said they used FB as an informational tool (rather than socialising) tended to score higher on neuroticism, sociability, extraversion and openness, but lower on conscientiousness and “need for cognition” . The researchers speculated that using FB to seek and share information could be some people’s way to avoid more cognitively demanding sources such as journal articles and newspaper reports. The same study also found that higher scorers in sociability, neuroticism and extraversion preferred FB, while people who scored higher in “need for cognition” preferred Twitter.

What do we give away about ourselves on Facebook? FB seems like the perfect way to present an idealised version of yourself to the world. However an analysis of the profiles of over 200 people in Germany and the US found that they reflected their actual personalities, not their ideal selves. Consistent with this, another study found that people who are rated as more likeable in the flesh also tend to be rated as more likeable based on their Facebook page. The things you choose to “like” on FB are also revealing. Remarkably, a study out last week found that your “likes” can be analysed by a computer programme to produce a more accurate profile of your personality than the profiles produced by your friends and relatives.

If our FB profiles expose our true selves, this raises obvious privacy issues. A study in 2013 warned that employers often trawl candidates’ FB pages, and that they view photos of drinking and partying as “red flags”, presumably seeing them as a sign of low conscientiousness (in fact the study found photos like these were linked with high extraversion, not with low conscientiousness).

Other researchers have looked specifically at how personality is related to the kind of content people post on FB. A 2014 study reported that “ higher degrees of narcissism led to deeper self-disclosures and more self-promotional content within these messages. [And] Users with higher need to belong disclosed more intimate information “. Another study last year also reported that lonelier people disclose more private information , but fewer opinions.

You might also want to consider the friends you keep on FB – research suggests that their attractiveness (good-lookers give your rep a boost), and the statements they make about you on your wall, affect the way your own profile is perceived . Consider too how many friends you have – somewhat paradoxically, research finds that having an overabundance of friends leads to negative perceptions of your profile .

Finally, we heard about employers frowning on partying photos, but what else do you give away in your FB profile picture? It could reveal your cultural background according to a 2012 study that showed people from Taiwan were more likely to have a zoomed-out picture in which they were seen against a background context, while US users were more likely to have a close-up picture in which their face filled up more of the frame. Your FB pic might also say something about your current romantic relationship. When people feel more insecure about their partner’s feelings, they make their relationship more visible in their pics .

In case you’re wondering, yes, people who post more selfies probably are more narcissistic .

Is Facebook making us lonely and sad?

This is the crunch question that has probably attracted the most newspaper column inches (and books ). A 2012 study took an experimental approach. One group were asked to post more updates than usual for one week – this led them to feel less lonely and more connected to their friends . Similarly, a survey of over a thousand FB users found links between use of the network and greater feelings of belonging and confidence in keeping up with friends, especially for people with low self-esteem. Another study from 2010 found that shy students who use FB feel closer to their friends (on FB) and have a greater sense of social support. A similar story is told by a 2013 paper that said feelings of FB connectedness were associated with “with lower depression and anxiety and greater satisfaction with life” and that Facebook “may act as a separate social medium …. with a range of positive psychological outcomes.” This recent report also suggested the site can help revive old relationships.

Yet there’s also evidence for the negative influence of FB. A 2013 study texted people through the day, to see how they felt before and after using FB. “ The more people used Facebook at one time point, the worse they felt the next time we text-messaged them ; [and] the more they used Facebook over two-weeks, the more their life satisfaction levels declined over time,” the researchers said.

Other findings are more nuanced. This study from 2010 (not specifically focused on FB) found that using the internet to connect with existing friends was associated with less loneliness, but using it to connect with strangers (i.e. people only known online) was associated with more loneliness. This survey of adults with autism found that greater use of online social networking (including FB) was associated with having more close friendships, but only offline relationships were linked with feeling less lonely.

Facebook could also be fuelling envy . In 2012 researchers found that people who’d spent more time on FB felt that other people were happier, and that life was less fair. Similarly, a study of hundreds of undergrads found that more time on FB went hand in hand with more feelings of jealousy . And a paper from last year concluded that “ people feel depressed after spending a great deal of time on Facebook because they feel badly when comparing themselves to others.” However, this new report (on general online social networking, not just FB) found that heavy users are not more stressed than average, but are more aware of other people’s stress.

Is Facebook harming students’ academic work? This is another live issue among newspaper columnists and other social commentators. An analysis of the grades and FB use of nearly 4000 US students found that the more they used the network to socialise, the poorer their grades tended to be (of course, there could be a separate causal factor(s) underlying this association). But not all FB use is the same – the study found that using the site to collect and share information was actually associated with better grades. This survey of over 200 students also found that heavier users of FB tend to have lower academic grades, but note again that this doesn’t prove a causal link. Yet another study , this one from the University of Chicago, which included more convincing longitudinal data, found no evidence for a link between FB use and poorer grades; if anything there were signs of the opposite pattern. Still more positive evidence for FB came from a recent report that suggested FB – along with other social networking tools – could have cognitive benefits for elderly people. And finally, some miscellaneous findings

- These are the unwritten rules of Facebook , according to focus groups with students.

- Viewing your own FB profile boosts self-esteem .

- Emotions are contagious on Facebook (this is the recent study that caused controversy because users’ feeds were manipulated without them knowing).

- Surprise! Both male and female subjects are more willing to initiate friendships with opposite-sex profile owners with attractive photos .

- People publish posts on FB that they later regret for various reasons , including posting when they’re in an emotional state or misunderstanding their online social circles.

Who needs cheap thrills or meditation? Apparently, looking at your FB account is different, physiologically speaking, from stress or relaxation. It provokes what these researchers describe appealingly as a “ core flow state “, characterised by positive mood and high arousal.

This post first appeared on the British Psychological Society’s Research Digest Blog . Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

Author: Christian Jarrett, a cognitive neuroscientist turned science writer, is editor and creator of the British Psychological Society’s Research Digest blog. His latest book is Great Myths of the Brain .

This post is published as part of a blog series by the Human Implications of Digital Media project .

Image: People are silhouetted as they pose with mobile devices. REUTERS/Dado Ruvic.

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Media, Entertainment and Sport .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

The Paris Olympics aims to be the greenest Games in history. Here's how

Paris to host the first-ever gender-equal Olympics

Disinformation is a threat to our trust ecosystem. Experts explain how to curb it

Jesus Serrano

March 7, 2024

What does freedom of speech mean in the internet era?

John Letzing

March 5, 2024

AI and Hollywood: 5 questions for SAG-AFTRA’s chief negotiator

Spencer Feingold

March 4, 2024

AI, leadership, and the art of persuasion – Forum podcasts you should hear this month

Robin Pomeroy

March 1, 2024

REVIEW article

Negative psychological and physiological effects of social networking site use: the example of facebook.

- 1 Digital Business Institute, School of Business and Management, University of Applied Sciences Upper Austria, Steyr, Austria

- 2 Institute of Business Informatics – Information Engineering, Johannes Kepler University Linz, Linz, Austria

- 3 Department of Molecular Psychology, Institute of Psychology and Education, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany

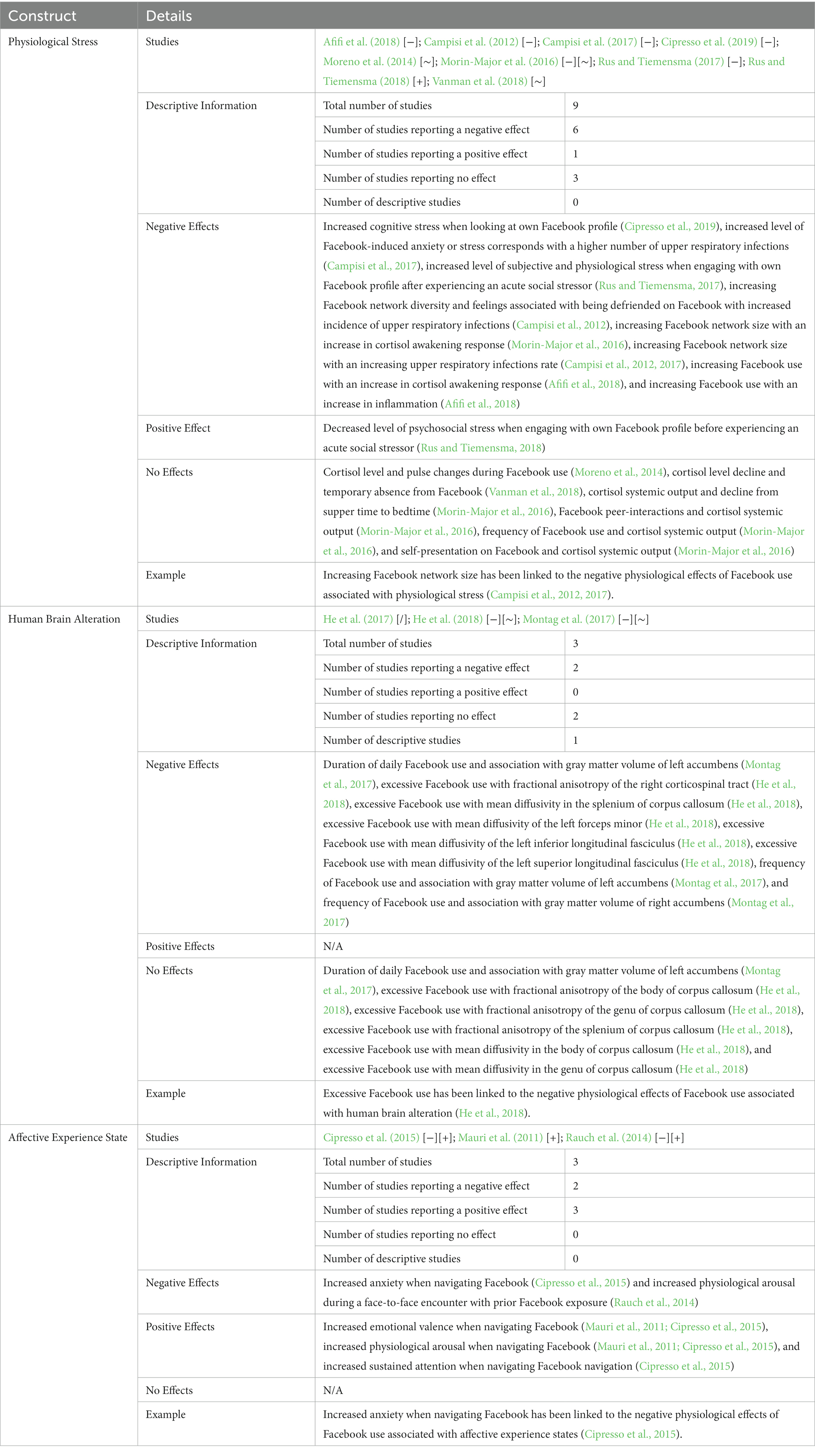

Social networking sites (SNS), with Facebook as a prominent example, have become an integral part of our daily lives and more than four billion people worldwide use SNS. However, the (over-)use of SNS also poses both psychological and physiological risks. In the present article, we review the scientific literature on the risk of Facebook (over-)use. Addressing this topic is critical because evidence indicates the development of problematic Facebook use (“Facebook addiction”) due to excessive and uncontrolled use behavior with various psychological and physiological effects. We conducted a review to examine the scope, range, and nature of prior empirical research on the negative psychological and physiological effects of Facebook use. Our literature search process revealed a total of 232 papers showing that Facebook use is associated with eight major psychological effects (perceived anxiety, perceived depression, perceived loneliness, perceived eating disorders, perceived self-esteem, perceived life satisfaction, perceived insomnia, and perceived stress) and three physiological effects (physiological stress, human brain alteration, and affective experience state). The review also describes how Facebook use is associated with these effects and provides additional details on the reviewed literature, including research design, sample, age, and measures. Please note that the term “Facebook use” represents an umbrella term in the present work, and in the respective sections it will be made clear what kind of Facebook use is associated with a myriad of investigated psychological variables. Overall, findings indicate that certain kinds of Facebook use may come along with significant risks, both psychologically and physiologically. Based on our review, we also identify potential avenues for future research.

1. Introduction

Social networking sites (SNS) have become an integral part of our daily lives and play an important role in many areas. The main benefits of SNSs include creating connections between people ( Hess et al., 2016 ), supporting collaboration and interpersonal communication ( Kane et al., 2014 ), building social capital ( Kwon et al., 2013 ) and generating marketing opportunities ( Schreiner et al., 2021 ). Thus, SNSs provide a platform for social connection and sense of belonging ( Zhao et al., 2012 ; Sariyska et al., 2019 ), which is considered a fundamental biological human need ( Maslow, 1943 ; Kunc, 1992 ; Kenrick et al., 2010 ; Montag et al., 2020b ; Rozgonjuk et al., 2021a ). Also, SNSs promote continuous engagement due to their numerous features and functions. Examples include creating and maintaining personal profiles, sharing posts with family and friends, responding to notifications, or playing games ( Frost and Rickwood, 2017 ; Chuang, 2020 ).

A prominent example of an SNS is Facebook. In fact, it is the most used SNS in the world, with around 2.96 billion active users each month ( Statista, 2022d ). American users, for example, spend an average of 33 min per day on Facebook ( Statista, 2022a ). An excessive and uncontrolled use of Facebook, however, also poses risks, both psychologically and physiologically. For example, frequent interaction with Facebook is associated with greater psychological distress ( Chen and Lee, 2013 ). Mabe et al. (2014) found an association between regular social network use and perceived eating disorders. Other negative consequences that may result from excessive and uncontrolled Facebook use include the perception of depressive symptoms and anxiety (e.g., Wright et al., 2018 ), lower self-esteem (e.g., Hanna et al., 2017 ), as well as psychological (e.g., Brailovskaia et al., 2019a ) and physiological stress (e.g., Campisi et al., 2017 ). Those who spend several hours a day on Facebook run the risk of losing control over their usage behavior ( Brailovskaia and Margraf, 2017 ) and developing a Facebook addiction ( Koc and Gulyagci, 2013 ). Please note that the addiction term is not officially recognized when discussing social media overuse (for debates, please see Carbonell and Panova, 2017 ) and it is of importance to not overpathologize everyday life behavior ( Billieux et al., 2015 ).

Considering the potential risks of an excessive and uncontrolled Facebook use, the aim of this paper is to develop a concise and fundamental understanding of the negative psychological and physiological effects of Facebook use by synthesizing the accumulated knowledge of prior research. This review is therefore designed to provide an in-depth comprehension of the scope, range, and nature of the existing literature on the negative effects of Facebook use, including psychological and physiological effects ( Hart, 1988 ). The term ‘Facebook use’ is an umbrella concept in our work. In the literature, different forms of Facebook use have been discussed ranging from overall use in terms of duration or frequency to active/passive use of Facebook (for recent updates, please see Verduyn et al., 2022 ) to addictive like use ( Sindermann et al., 2020 ). Logically, different forms of Facebook use might be associated with different psychological effects. Therefore, each section will state in detail how Facebook use was operationalized in the different studies. When we speak in the following of “Facebook use,” it should be kept in mind that the term “Facebook use” here describes all kinds of Facebook use investigated in the literature. Accordingly, we address the following research question: What negative psychological and physiological effects of Facebook use are identified by the current state of scientific research?

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the methodology of our review. Then, Section 3 follows with a presentation of the review results. We discuss our results in Section 4 by focusing on contributions and potentials for future research activities. Finally, in Section 5, we provide a concluding statement.

2. Review methodology

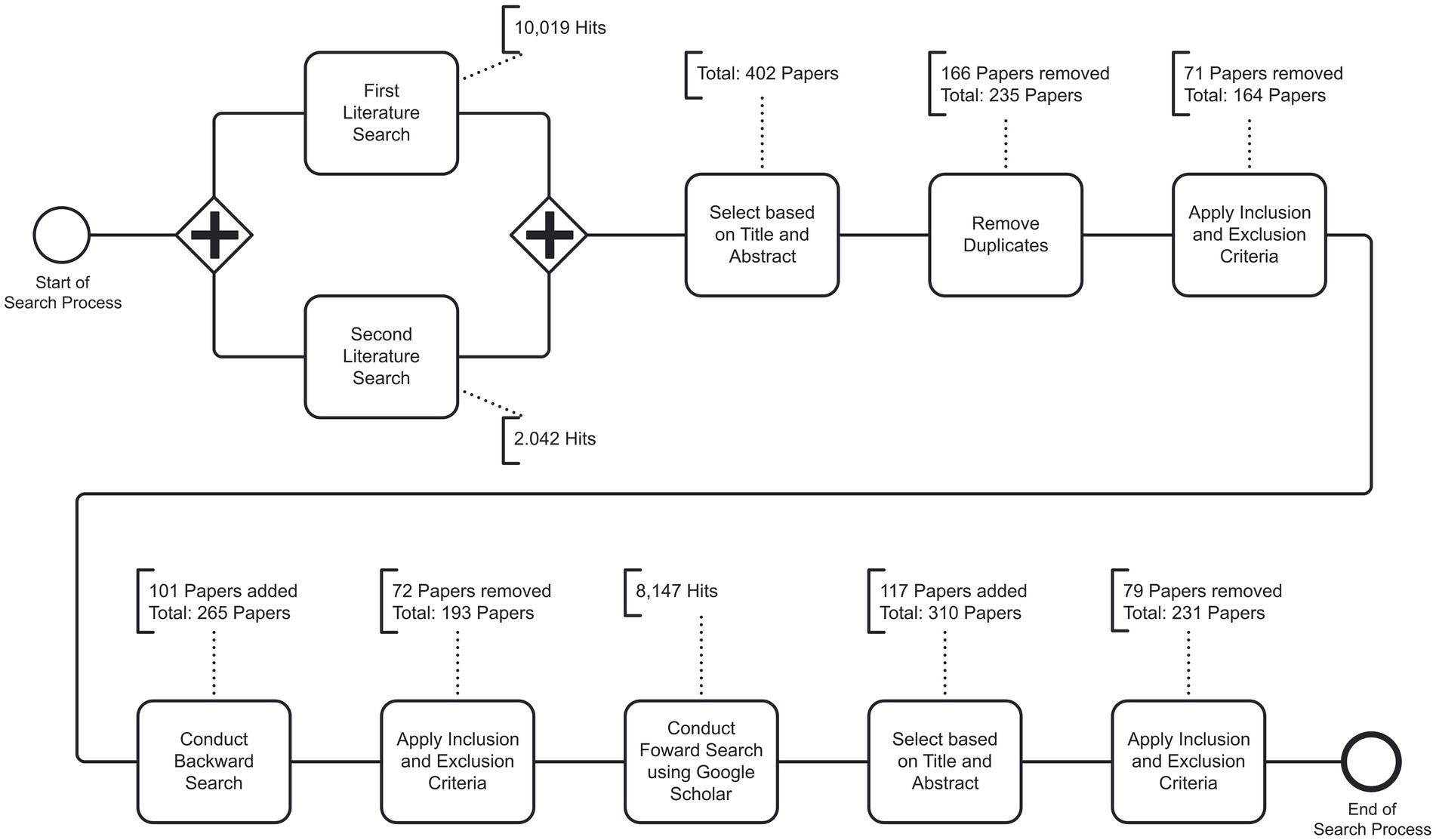

To examine the scope, range, and nature of prior research on the negative psychological and physiological effects of Facebook use, we conducted a scoping review to determine the extent of existing literature and the topics addressed therein (for an overview of the different literature review types, please see Paré et al., 2015 ; Schryen et al., 2017 , 2020 ). The literature search process was based on existing methodological recommendations for conducting literature searches ( Webster and Watson, 2002 ; Kitchenham and Charters, 2007 ; vom Brocke et al., 2009 ) and considered peer-reviewed journal and conference papers in English with no publication year restriction. As outlined in detail below, the present review includes literature published prior to and in April 2022. Based on primary selected papers after a two-wave literature search, we conducted an initial review, followed by backward search, a second review of the associated results, and a subsequent forward search. Figure 1 graphically summarizes the literature search process.

Figure 1 . Overview of literature search process.

2.1. Search strategy

We conducted a two-wave literature search of five literature databases. We searched ACM Digital Library, IEEE Xplore, Science Direct, Scopus, and Web of Science using a combination of the term “Facebook” in conjunction with terms addressing the negative psychological and physiological effects of Facebook use. This search process yielded a total of 12,061 hits.

The following search term syntax was used to identify empirical studies that addressed the negative effects of Facebook use on a psychological and/or physiological level: (“Facebook”) AND (“psychological” OR “physiological” OR “depress*” OR “anxiety” OR “stress” OR “life satisfaction” OR “self-esteem” OR “loneliness” OR “consequence” OR “outcome” OR “disorder” OR “sleep*”). Note that the asterisk was used to generalize the term for searching when it can have multiple meanings (i.e., depress* includes “depression,” “depressing,” or “depressive” and other terms beginning with “depress”). In the databases IEEE Xplore, Science Direct, Scopus, and Web of Science the search terms could be used by default mode (that covers title, abstract, and keywords) to search for relevant papers. For the ACM database search, the abstract was used to narrow the search for relevant papers.

The first wave of our literature search was conducted in March 2022 and yielded 10,019 hits. The second wave was conducted in April 2022 with the goal of obtaining additional empirical studies on the negative physiological effects of Facebook use. To this end, we repeated our literature search in the mentioned literature databases and included the following physiological keywords [adopted from Riedl et al., 2020 ], resulting in the following search term syntax: (“Facebook”) AND (“Nervous system” OR “Neuro-Information Systems” OR “NeuroIS” OR “Neuroscience” OR “Brain” OR “Diffusion Tensor” OR “EEG” OR “fMRI” OR “Infared” OR “MEG” OR “Morpho*” OR “NIRS” OR “Positron emission” OR “Transcranial” OR “Dermal” OR “ECG” OR “ECG” OR “Electrocardiogram” OR “Electromyography” OR “Eye” OR “Facial” OR “Galvan*” OR “Heart” OR “HRV” OR “Muscular” OR “Oculo*” OR “Skin” OR “Blood” OR “Hormone” OR “Saliva” OR “Urine”). The second wave of our literature search yielded 2,042 hits. Note that NeuroIS is a scientific field which relies on neuroscience and neurophysiological knowledge and tools to better understand the development, use, and impact of information and communication technologies, including SNSs ( Riedl et al., 2020 ).

In summary, search terms were chosen to reflect the topic of this paper in its entirety (e.g., “psychological” and “physiological”). Additionally, specific search terms were used to refer specifically to the psychological and physiological effects (e.g., “depress*” and “stress”). We also used keywords such as “ECG” that are representative of the data collection methods for measuring physiological effects to identify additional studies. In both waves of our literature search, we focused exclusively on peer-reviewed English-language journal and conference papers with no publication date restriction.

2.2. Filtering strategy

The filtering strategy included empirical studies that examined the negative effects of Facebook use on a psychological or physiological level as eligibility criteria. The psychological effects include those that are generally consistent with the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5 Update) published by the American Psychiatric Association (2018) . In addition, loneliness, life satisfaction, and self-esteem were also considered, although they are not included in the DSM-5 Update. They are considered as important psychological indicators and are critical for mental and physical well-being ( Mann et al., 2004 ; Mushtaq et al., 2014 ) and subjective well-being along with life satisfaction ( Pavot and Diener, 1993 ).

“Facebook use” was defined as use of all features of Facebook. Common conceptualizations of Facebook use include time spent on Facebook, number of Facebook friends, number of logins to Facebook, attitudes toward Facebook use, or indicators of an addiction construct consisting of a combination of behavioral and attitudinal variables ( Frost and Rickwood, 2017 ): Therefore, we additionally considered the problematic facets of Facebook use, such as Facebook addiction ( Turel et al., 2014 ) and Facebook intrusion ( Cudo et al., 2019 ). Please note that in the literature Facebook overuse is often assessed via an addiction framework, but as mentioned above, neither Facebook addiction nor problematic Facebook use (the more neutral term) are officially recognized conditions in either DSM-5 ( American Psychiatric Association, 2018 ) or the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11; World Health Organization, 2019 ). We do not want to go deeper into this discussion here but highlight that we aim to review both papers dealing with use and overuse of Facebook, independently of how the actual nature of overuse will be seen or characterized in a few years.

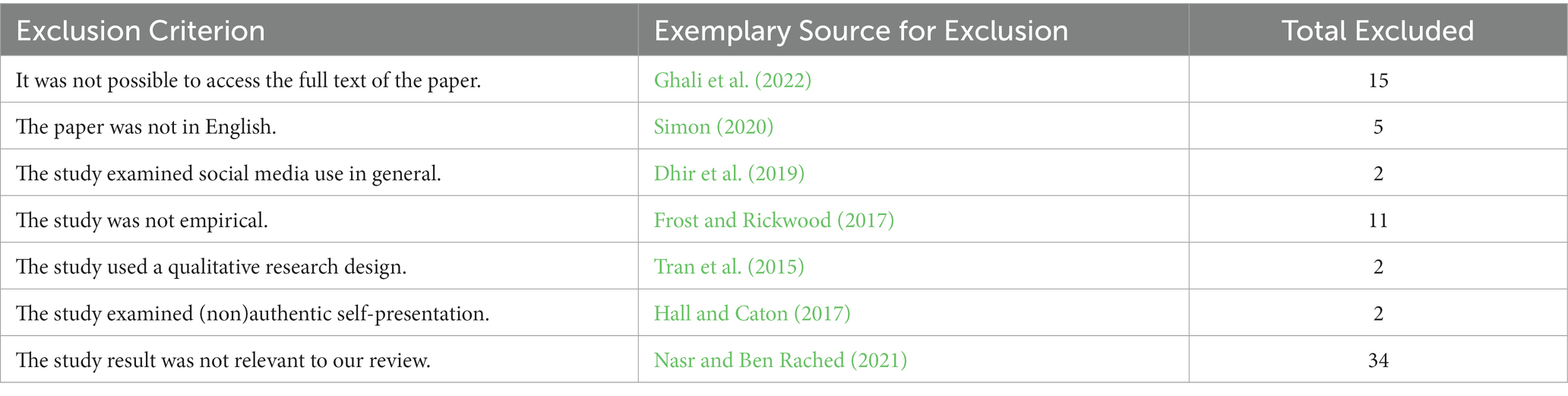

To be included in this review, we focused exclusively on peer-reviewed studies that empirically investigated negative effects of Facebook use on a psychological or physiological level. After conducting the two-wave literature search, we removed unrelated papers based on title and abstract, which left us with 402 papers. We then removed duplicates, which left us with 236 unique papers, which were then analyzed in-depth based on the full text. During this process, we also developed and applied the exclusion criteria listed in Table 1 to exclude papers that were not adequate in the light of the goal of this review. Following this filtering strategy, 165 unique papers remained for further analysis.

Table 1 . Exclusion criteria for literature review.

2.3. Backward and forward search

The 165 identified papers were then used for a backward search (i.e., searching the references), which yielded 101 additional papers, resulting in a total of 266 unique papers. After applying our exclusion criteria, 72 papers were removed, leaving a total of 194 papers. Next, we conducted a forward search (i.e., citation tracking) based on the 194 papers by using Google Scholar. This part of the search process resulted in 5,984 hits, of which 114 papers were selected for further investigation based on title and abstract, yielding a total of 308 papers. As part of this step, we excluded papers that were not peer-reviewed (e.g., Denti et al., 2012 ; Steggink, 2015 ). After applying our full list of exclusion criteria, 76 papers were removed, leaving a total of 232 papers which constitute the basis of all analyses in the present review.

Overall, this review includes empirical literature on the negative psychological and physiological effects of Facebook use published before and in April 2022. Specifically, 217 papers deal with the negative psychological effects of Facebook use, consisting of 213 journal papers (98%) and 4 conference papers (2%), and the remaining 15 papers (all journal articles) deal with the negative physiological effects of Facebook use. The Supplementary material contains an overview of the N = 232 papers.

3. Review results

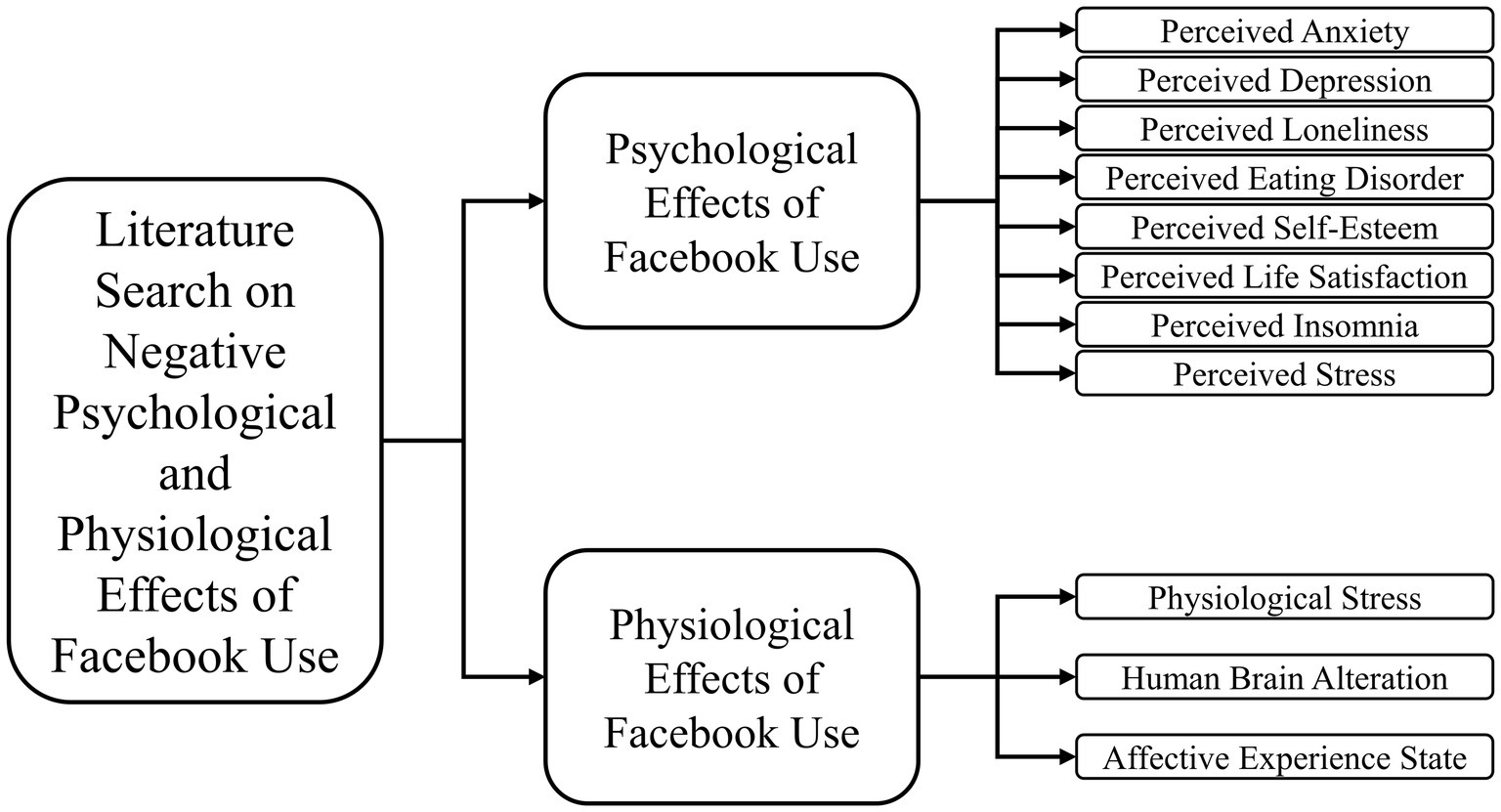

In this section, we present the main findings of our review. Our literature search process revealed a total of 232 papers showing that Facebook use is associated with eight psychological effects (perceived anxiety, perceived depression, perceived loneliness, perceived eating disorders, perceived self-esteem, perceived life satisfaction, perceived insomnia, and perceived stress) and three physiological effects (physiological stress, human brain alteration, and affective experience state). Figure 2 graphically summarizes the main findings of our literature search process. The psychological effects of Facebook use are described in detail below, followed by the physiological effects. The Supplementary material provides additional details on the identified studies by construct (i.e., identified psychological and physiological effects), including research design, sample, age, measures, and strength of associations between Facebook use and its effects.

Figure 2 . Overview of main findings of literature search process.

3.1. Psychological effects of Facebook Use

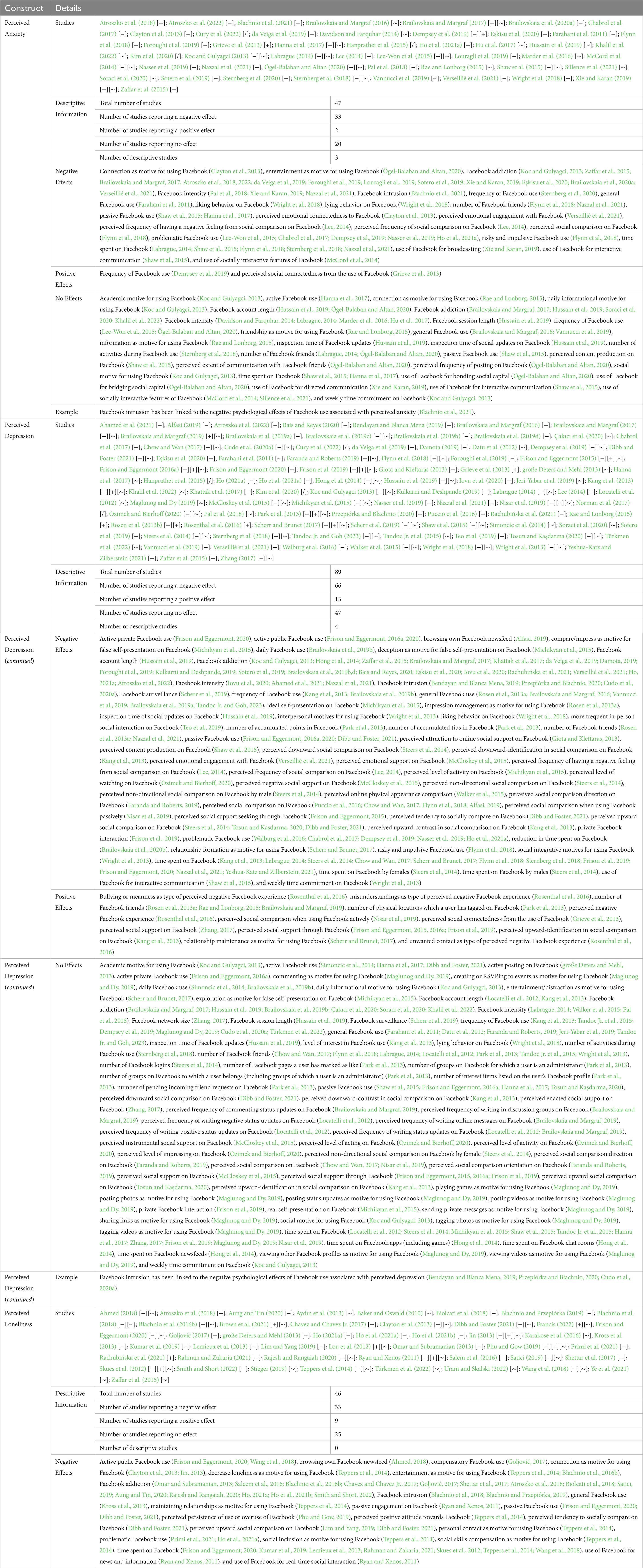

We found 217 empirical studies that examined psychological effects of Facebook use. The 217 studies included 183 cross-sectional studies (85%), 24 longitudinal studies (11%), 5 experimental studies (2%), and 5 studies that conducted a multimethod research design (2%). Our analysis revealed that Facebook use is associated with eight major psychological effects, which we discuss in the following. We summarize the identified papers on the psychological effects of Facebook use with their effect type, based on results which are reported as statistically significant (negative [−], positive [+], no effect [∼] in Table 2 ). To reveal the scope, range, and nature of prior empirical research on how Facebook use is associated with these psychological effects, we considered the research context of the identified studies rather than just the effect direction. For example, we classified the Błachnio et al.’s (2021) paper as a study reporting a negative effect because it found that Facebook intrusion was positively associated with perceived anxiety. Note that we also classified a few papers as “descriptive [/],” referring to studies that reported only descriptive statistics such as frequency distributions associated with Facebook addiction without correlative or more sophisticated statistics ( Jha et al., 2016 ; Norman et al., 2017 ).

Table 2 . Studies on psychological effects of Facebook use.

3.1.1. Perceived anxiety

Forty-seven studies were found that examined the psychological effects of Facebook use on perceived (social) anxiety. Results varied widely, ranging from no effect to a strong effect. The 47 studies included 43 cross-sectional studies (42 surveys and 1 case–control survey), 2 longitudinal studies (2 panel studies), 1 experimental study (1 quasi-experiment), and 1 study that applied a multimethod research design (1 study was a longitudinal panel study and another one an experimental study with a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design).

The results of the review revealed that Facebook addiction was slightly to strongly positively correlated with perceived (social) anxiety ( Koc and Gulyagci, 2013 ; Zaffar et al., 2015 ; Brailovskaia and Margraf, 2017 ; Atroszko et al., 2018 , 2022 ; da Veiga et al., 2019 ; Foroughi et al., 2019 ; Louragli et al., 2019 ; Sotero et al., 2019 ; Xie and Karan, 2019 ; Eşkisu et al., 2020 ; Brailovskaia et al., 2020a , b ; Verseillié et al., 2021 ). Results also suggest that individuals with Facebook addiction are at high risk of developing anxiety ( Hanprathet et al., 2015 ). Further examples of positive effects on perceived (social) anxiety include, for example, Facebook intrusion ( Błachnio et al., 2021 ), lying and liking behavior on Facebook ( Wright et al., 2018 ), number of Facebook friends ( Flynn et al., 2018 ; Nazzal et al., 2021 ), perceived emotional connectedness to Facebook ( Clayton et al., 2013 ), perceived emotional engagement with Facebook ( Verseillié et al., 2021 ), risky and impulsive Facebook use ( Flynn et al., 2018 ), time spent on Facebook ( Labrague, 2014 ; Shaw et al., 2015 ; Flynn et al., 2018 ; Sternberg et al., 2018 ; Nazzal et al., 2021 ), and use of socially interactive features of Facebook ( McCord et al., 2014 ). For individuals who make social comparisons on Facebook, which can lead to a perceived frequency of a negative feeling from social comparisons on Facebook ( Lee, 2014 ), there was a medium positive effect for perceived anxiety. Positive correlations with perceived anxiety were also found to a small to moderate extent for users with passive Facebook use ( Shaw et al., 2015 ; Hanna et al., 2017 ) or problematic Facebook use ( Lee-Won et al., 2015 ; Chabrol et al., 2017 ; Dempsey et al., 2019 ; Nasser et al., 2019 ; Ho et al., 2021a ). Examples of negative effects on perceived (social) anxiety are frequency of Facebook use ( Dempsey et al., 2019 ) or perceived social connectedness from the use of Facebook ( Grieve et al., 2013 ).

No statistically significant effect was found between the following types of Facebook use and perceived (social) anxiety, among others: academic motive for using Facebook ( Koc and Gulyagci, 2013 ), active Facebook use ( Hanna et al., 2017 ), connection as motive for using Facebook ( Rae and Lonborg, 2015 ), daily informational motive for using Facebook ( Koc and Gulyagci, 2013 ), Facebook account length ( Hussain et al., 2019 ; Ögel-Balaban and Altan, 2020 ), friendship as motive for using Facebook ( Rae and Lonborg, 2015 ), information as motive for using Facebook ( Rae and Lonborg, 2015 ), inspection time of Facebook updates ( Hussain et al., 2019 ), inspection time of social updates on Facebook ( Hussain et al., 2019 ), number of activities during Facebook use ( Sternberg et al., 2018 ), perceived frequency of posting on Facebook ( Ögel-Balaban and Altan, 2020 ), social motive for using Facebook ( Koc and Gulyagci, 2013 ), use of Facebook for interactive communication ( Shaw et al., 2015 ), use of socially interactive features of Facebook ( McCord et al., 2014 ; Sillence et al., 2021 ), and weekly time commitment on Facebook ( Koc and Gulyagci, 2013 ). A summary of all effects of the forty-seven studies that examined the psychological effects of Facebook use on perceived (social) anxiety can be found in Table 2 .

3.1.2. Perceived depression

Eighty-nine studies were found that examined the psychological effects of Facebook use on perceived depression. Results varied widely, ranging from no effect to a strong effect. The 89 studies included 76 cross-sectional studies (75 surveys and 1 case–control survey), 10 longitudinal studies (8 panel studies and 2 longitudinal randomized experiments), 2 experimental studies (1 quasi-experiment and 1 experimental study with an RCT design), and 1 study that applied a multimethod research design (1 study was a cross-sectional survey study and another one was a longitudinal study with a time-series design).

Low to high positive effects on perceived depression have been found among individuals who are addicted to Facebook ( Koc and Gulyagci, 2013 ; Hong et al., 2014 ; Zaffar et al., 2015 ; Brailovskaia and Margraf, 2017 ; Khattak et al., 2017 ; da Veiga et al., 2019 ; Damota, 2019 ; Foroughi et al., 2019 ; Kulkarni and Deshpande, 2019 ; Sotero et al., 2019 ; Brailovskaia et al., 2019b , d ; Bais and Reyes, 2020 ; Eşkisu et al., 2020 ; Iovu et al., 2020 ; Rachubińska et al., 2021 ; Verseillié et al., 2021 ; Ho, 2021a ; Atroszko et al., 2022 ) or through perceived social comparisons on Facebook, such as the perceived upward social comparison on Facebook ( Steers et al., 2014 ; Tosun and Kaşdarma, 2020 ; Dibb and Foster, 2021 ). Further positive effects on perceived depression include active private or public Facebook use ( Frison and Eggermont, 2016a , 2020 ), Facebook intensity ( Iovu et al., 2020 ; Ahamed et al., 2021 ; Nazzal et al., 2021 ), Facebook intrusion ( Bendayan and Blanca Mena, 2019 ; Przepiórka and Błachnio, 2020 ; Cudo et al., 2020a , b ), Facebook surveillance ( Scherr et al., 2019 ), liking behavior on Facebook ( Wright et al., 2018 ), passive Facebook use ( Frison and Eggermont, 2016a , 2020 ; Dibb and Foster, 2021 ), perceived negative social support on Facebook ( McCloskey et al., 2015 ), problematic Facebook use ( Walburg et al., 2016 ; Chabrol et al., 2017 ; Dempsey et al., 2019 ; Nasser et al., 2019 ; Ho et al., 2021a ), and time spent on Facebook ( Kang et al., 2013 ; Labrague, 2014 ; Steers et al., 2014 ; Chow and Wan, 2017 ; Scherr and Brunet, 2017 ; Flynn et al., 2018 ; Sternberg et al., 2018 ; Frison et al., 2019 ; Frison and Eggermont, 2020 ; Nazzal et al., 2021 ; Yeshua-Katz and Zilberstein, 2021 ). Also, results suggest that general Facebook use predicts bipolar disorder ( Rosen et al., 2013a , b ).

Examples of negative effects on perceived depression include perceived social comparison when using Facebook actively ( Nisar et al., 2019 ), perceived social connectedness from the use of Facebook ( Grieve et al., 2013 ), perceived social support through Facebook ( Frison and Eggermont, 2015 , 2016a ; Frison et al., 2019 ), perceived upward-identification in social comparison on Facebook ( Kang et al., 2013 ), and relationship maintenance as motive for using Facebook ( Scherr and Brunet, 2017 ). The number of Facebook friends, for example, was both negatively ( Rae and Lonborg, 2015 ; Brailovskaia and Margraf, 2019 ) and positively ( Nazzal et al., 2021 ) associated with perceived depression.

No statistically significant effect was found between the following types of Facebook use and perceived loneliness, among others: Facebook account length ( Locatelli et al., 2012 ; Kang et al., 2013 ), Facebook network size ( Zhang, 2017 ), Facebook session length ( Hussain et al., 2019 ), level of interest in Facebook use ( Kang et al., 2013 ), lying behavior on Facebook ( Wright et al., 2018 ), number of activities during Facebook use ( Sternberg et al., 2018 ), number of Facebook pages a user has marked as like ( Park et al., 2013 ), number of groups on Facebook for which a user is an administrator ( Park et al., 2013 ), number of groups on Facebook to which a user belongs (including groups of which a user is an administrator) ( Park et al., 2013 ), number of interest items listed on the user’s Facebook profile ( Park et al., 2013 ), number of pending incoming friend requests on Facebook ( Park et al., 2013 ), perceived downward social comparison on Facebook ( Dibb and Foster, 2021 ), perceived frequency of writing in discussion groups on Facebook ( Brailovskaia and Margraf, 2019 ), perceived frequency of writing negative status updates on Facebook ( Locatelli et al., 2012 ), perceived frequency of writing online messages on Facebook ( Brailovskaia and Margraf, 2019 ), perceived frequency of writing positive status updates on Facebook ( Locatelli et al., 2012 ), perceived frequency of writing status updates on Facebook ( Locatelli et al., 2012 ; Brailovskaia and Margraf, 2019 ), time spent on Facebook apps (including games) ( Hong et al., 2014 ), time spent on Facebook chat rooms ( Hong et al., 2014 ), time spent on Facebook newsfeeds ( Hong et al., 2014 ), and viewing other Facebook profiles as motive for using Facebook ( Maglunog and Dy, 2019 ). A summary of all effects of the eighty-nine studies that examined the psychological effects of Facebook use on perceived depression can be found in Table 2 .

3.1.3. Perceived loneliness

Forty-six studies were found that examined the psychological effects of Facebook use on perceived loneliness. Results varied widely, ranging from no effect to a strong effect. The 46 studies included 41 cross-sectional studies (40 surveys) and 5 longitudinal studies (4 panel studies and 1 longitudinal randomized experiment).

Very strong positive effects on perceived loneliness were found for perceived upward social comparison on Facebook ( Lim and Yang, 2019 ; Dibb and Foster, 2021 ). Also, a positive medium-strong correlation was found between compensatory Facebook use ( Goljović, 2017 ) or connection as motive for using Facebook ( Clayton et al., 2013 ; Jin, 2013 ) and perceived loneliness. A medium-weak correlation was found between time spent on Facebook ( Skues et al., 2012 ; Lemieux et al., 2013 ; Teppers et al., 2014 ; Kumar et al., 2019 ; Frison and Eggermont, 2020 ; Rahman and Zakaria, 2021 ) and perceived loneliness. Furthermore, Facebook addiction correlates positively with perceived loneliness to a low to moderate level ( Omar and Subramanian, 2013 ; Saleem et al., 2016 ; Błachnio et al., 2016a ; Chavez and Chavez Jr., 2017 ; Goljović, 2017 ; Shettar et al., 2017 ; Atroszko et al., 2018 ; Biolcati et al., 2018 ; Satici, 2019 ; Aung and Tin, 2020 ; Rajesh and Rangaiah, 2020 ; Ho et al., 2021a Ho, 2021a ; Smith and Short, 2022 ). However, Rachubińska et al. (2021) also found a negative correlation between Facebook addiction and perceived loneliness.

A negative effect was found between the number of Facebook friends and perceived loneliness ( Skues et al., 2012 ; Jin, 2013 ; Phu and Gow, 2019 ). That is, the more Facebook friends one has, the lower the feeling of perceived loneliness. Results also indicate that active use of Facebook ( Jin, 2013 ), including connection ( Clayton et al., 2013 ; Jin, 2013 ), maintaining relationships ( Teppers et al., 2014 ), or personal contact ( Teppers et al., 2014 ) as motive for using Facebook can reduce perceived loneliness. Also, results suggest that active posting on Facebook can reduce perceived loneliness ( große Deters and Mehl, 2013 ).

No statistically significant effect was found between the following types of Facebook use and perceived depression, among others: communication as motive for using Facebook ( Aydın et al., 2013 ), Facebook access time via PC ( Ye et al., 2021 ), Facebook access time via smartphone ( Ye et al., 2021 ), following photos, videos, status, comments as motive for using Facebook ( Aydın et al., 2013 ), frequency of Facebook use ( Türkmen et al., 2022 ), new acquaintance as motive for using Facebook ( Aydın et al., 2013 ), number of Facebook logins ( Skues et al., 2012 ), passive engagement on Facebook ( Ryan and Xenos, 2011 ), perceived boredom of use of Facebook ( Phu and Gow, 2019 ), perceived downward social comparison on Facebook ( Dibb and Foster, 2021 ), perceived use experience of Facebook ( Jin, 2013 ), personal contact as motive for using Facebook ( Teppers et al., 2014 ), playing games on Facebook as motive for using Facebook ( Aydın et al., 2013 ), sharing photos, videos, and notifications on Facebook as motive for using Facebook ( Aydın et al., 2013 ), time spent on Facebook for private purposes ( Stieger, 2019 ), use of Facebook chat ( Ahmed, 2018 ), and use of Facebook for news and information ( Ryan and Xenos, 2011 ). A summary of all effects of the forty-six that examined the psychological effects of Facebook use on perceived loneliness can be found in Table 2 .

3.1.4. Perceived eating disorder

Seven studies were found that examined the psychological effects of Facebook use on perceived eating disorder. Results varied widely, ranging from no effect to a strong effect. The 7 studies included 4 longitudinal studies (4 panel studies), 2 cross-sectional studies (2 surveys), and 1 study that applied a multimethod research design (1 study was a cross-sectional survey study and another one was a matched-pair experimental study).

Maladaptive Facebook use was found to be a significant predictor of increases in perceived bulimic symptoms, perceived body dissatisfaction, perceived shape concerns, and perceived episodes of overeating ( Smith et al., 2013 ). Results further indicate that maladaptive Facebook use had moderately strong positive effects on perceived concern about physical shape and weight ( Mannino et al., 2021 ). When Facebook was used to make online comparisons of physical appearance, it had large effects on perceived eating disorder, which means the more comparisons, the more likely the perceived eating disorder ( Walker et al., 2015 ). Perceptions of social comparison on Facebook also correlated significantly positively with perceived food restraint and perceived bulimic symptoms, although perceptions of social comparison on Facebook suggested that perceived bulimic symptoms decreased over time ( Puccio et al., 2016 ). Passive use of Facebook for social comparison ( Mannino et al., 2021 ), perceived negative feedback seeking on Facebook ( Hummel and Smith, 2015 ), personal status updates on Facebook ( Hummel and Smith, 2015 ), and time spent on Facebook ( Mannino et al., 2021 ) showed little to no effect on perceived physical shape concern, perceived concern about weight, or perceived concern about eating. Individuals who spent 20 min on Wikipedia showed greater decreases in perceived concerns about weight and shape than those individuals who spent 20 min on Facebook ( Mabe et al., 2014 ).

Facebook use was not significantly related to the “Eating Attitudes Test-26 (EAT-26)” ( González-Nuevo et al., 2021 ), a screening instrument for eating disorders, dieting, and bulimia ( Garner et al., 1982 ). Similarly, perceived negative feedback seeking on Facebook ( Hummel and Smith, 2015 ) was not associated with perceived dietary restraint ( Hummel and Smith, 2015 ). Also, time spent on Facebook did not significantly correlate with disordered eating behaviors ( Mabe et al., 2014 ). A summary of all effects of the seven that examined the psychological effects of Facebook use on perceived eating disorder can be found in Table 2 .

3.1.5. Perceived self-esteem

Sixty-seven studies were found that examined the psychological effects of Facebook use on perceived self-esteem. Results varied widely, ranging from no effect to a strong effect. The 67 studies included 58 cross-sectional studies (57 surveys and 1 case–control survey), 4 experimental studies (3 experimental studies with an RCT design and 1 quasi-experiment), 3 longitudinal studies (2 panel studies and 1 longitudinal study with a time-series design), and 2 studies that conducted a multimethod research design (specifically a cross-sectional survey study with an experimental study with an RCT design).

Perceptions of social comparison on Facebook, especially perceived upward social comparison on Facebook ( Vogel et al., 2014 ; Lee, 2020 ) and perceived frequency of a negative feeling from social comparisons on Facebook ( Lee, 2014 ) had a strong negative effect on perceived self-esteem ( Lee, 2014 , 2020 ). Facebook addiction also had a particularly negative effect on perceived self-esteem ( Hong et al., 2014 ; Malik and Khan, 2015 ; Błachnio et al., 2016b ; Baturay and Toker, 2017 ; Goljović, 2017 ; Nizami et al., 2017 ; Atroszko et al., 2018 ; Kanat-Maymon et al., 2018 ; Bais and Reyes, 2020 ; Eşkisu et al., 2020 ; Seran et al., 2020 ; Stănculescu and Griffiths, 2021 ; Awobamise et al., 2022 ; Smith and Short, 2022 ; Uram and Skalski, 2022 ). However, different results could be found in this regard. Namely, Sehar et al. (2022) found a strong positive relationship between Facebook addiction and perceived self-esteem. Facebook intensity also had a positive ( Whitman and Gottdiener, 2016 ) and negative ( Błachnio et al., 2016c ; Ahamed et al., 2021 ) effect on perceived self-esteem. Further examples of negative effects on perceived self-esteem include compensatory Facebook use ( Goljović, 2017 ), Facebook fatigue ( Cramer et al., 2016 ), Facebook intrusion ( Błachnio et al., 2019 ; Błachnio and Przepiórka, 2019 ; Przepiórka et al., 2021 ), perceived feeling of connectedness to Facebook ( Tazghini and Siedlecki, 2013 ), perceived frequency of untagging oneself from in photos on Facebook ( Tazghini and Siedlecki, 2013 ), perceived level of Facebook integration into daily activities ( Faraon and Kaipainen, 2014 ), perceived negative activities on Facebook ( Tazghini and Siedlecki, 2013 ), problematic Facebook use ( Tobin and Graham, 2020 ; Primi et al., 2021 ), risky and impulsive Facebook use ( Flynn et al., 2018 ), time spent on Facebook ( Faraon and Kaipainen, 2014 ; Hanna et al., 2017 ; Bergagna and Tartaglia, 2018 ), and use of Facebook for simulation ( Bergagna and Tartaglia, 2018 ). Research also suggests that browsing own Facebook newsfeed ( Alfasi, 2019 ), passive Facebook use ( Hanna et al., 2017 ), and use of Facebook for social comparison ( Ozimek and Bierhoff, 2020 ) are associated with lower perceived self-esteem.

Positive effects on perceived self-esteem included, for example, initiating of online relationships as motive for using Facebook ( Metzler and Scheithauer, 2017 ), liking behavior on Facebook ( Wright et al., 2018 ), number of Facebook friends ( Metzler and Scheithauer, 2017 ), temporary break from Facebook use ( O’Sullivan and Hussain, 2017 ), or use of socially interactive features of Facebook ( Błachnio et al., 2016d ), Facebook users had significantly higher mean score for perceived self-esteem compared to non-Facebook users ( Brailovskaia and Margraf, 2016 ). Individuals who viewed only their own profile reported higher self-esteem than those who viewed other profiles in addition to their own ( Gonzales and Hancock, 2011 ).

No statistically significant effect was found between the following types of Facebook use and perceived self-esteem, among others: active Facebook use ( Hanna et al., 2017 ), active hours on Facebook ( Baturay and Toker, 2017 ), education as intended purpose for using Facebook ( Eşkisu et al., 2017 ), frequency of Facebook use ( Cudo et al., 2020a , b ; Türkmen et al., 2022 ), information search on Facebook ( Castillo de Mesa et al., 2020 ), inspection time of social updates on Facebook ( Hussain et al., 2019 ), lying behavior on Facebook ( Wright et al., 2018 ), mobile Facebook use ( Schmuck et al., 2019 ), number of Facebook logins ( Skues et al., 2012 ), perceived level of activity on Facebook ( Michikyan et al., 2015 ), perceived level of awareness when using Facebook ( Tazghini and Siedlecki, 2013 ), public communication with Facebook friends ( Manago et al., 2012 ), reading on Facebook ( Cramer et al., 2016 ), social interaction as intended purpose for using Facebook ( Eşkisu et al., 2017 ), tolerance of diversity on Facebook ( Castillo de Mesa et al., 2020 ), use and presence of Facebook in life ( Castillo de Mesa et al., 2020 ), and use of Facebook for search for relations ( Bergagna and Tartaglia, 2018 ). A summary of all effects of the sixty-six studies that examined the psychological effects of Facebook use on perceived self-esteem can be found in Table 2 .

3.1.6. Perceived life satisfaction

Forty-four studies were found that examined the psychological effects of Facebook use on perceived life satisfaction. Results varied widely, ranging from no effect to a strong effect. The 44 studies included 37 cross-sectional studies (37 surveys) and 7 longitudinal studies (4 panel studies, 2 longitudinal randomized experiments, and 1 longitudinal study with a time-series design).

Examples of negative effects on perceived life satisfaction at a low to moderate level include various Facebook activities such as looking at other’s photos/videos on Facebook ( Vigil and Wu, 2015 ), tagging photos on Facebook ( Vigil and Wu, 2015 ), or uploading photos on Facebook ( Vigil and Wu, 2015 ). Compensatory Facebook Use ( Goljović, 2017 ), Facebook addiction ( Akın and Akın, 2015 ; Biolcati et al., 2018 ; Satici, 2019 ), Facebook intrusion ( Błachnio et al., 2019 ), passive Facebook use ( Frison and Eggermont, 2016b ), passive following on Facebook ( Wenninger et al., 2014 ), or time spent on Facebook ( Vigil and Wu, 2015 ; Frison and Eggermont, 2016b ; Stieger, 2019 ) were also negatively associated with perceived life satisfaction.

Positive effects on perceived life satisfaction were mainly due to active Facebook use ( Choi, 2022 ), Facebook check-in intensity ( Wang, 2013 ), and general Facebook use ( Basilisco and Cha, 2015 ; Srivastava, 2015 ; Brailovskaia and Margraf, 2016 ). Facebook network size ( Manago et al., 2012 ), number of Facebook friends ( Nabi et al., 2013 ; Srivastava, 2015 ; Vigil and Wu, 2015 ; Lönnqvist and große Deters, 2016 ), number of Facebook hours per week ( Cudo et al., 2020a , b ), perceived social attention on Facebook ( Adnan and Mavi, 2015 ), or perceived social connectedness from the use of Facebook ( Grieve et al., 2013 ) also influenced perceived life satisfaction in positive ways. A 20-min reduction in daily Facebook time produced a steady increase in perceived life satisfaction scores over a three-month period ( Brailovskaia et al., 2020a , 2020b ). Furthermore, one study showed that increasing Facebook use over time is associated with lower perceived life satisfaction ( Kross et al., 2013 ). This finding is consistent with another study that found perceived life satisfaction increased after a one-week absence from Facebook ( Tromholt, 2016 ). In contrast to these results, Facebook users had significantly higher mean scores for perceived life satisfaction compared to non-Facebook users ( Brailovskaia and Margraf, 2016 ).