Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Relationships Articles & More

How life could get better (or worse) after covid, fifty-seven scientists make predictions about potential positive and negative consequences of the pandemic..

How do pandemics change our societies? It is tempting to believe that there will not be a single sector of society untouched by the COVID-19 pandemic . However, a quick look at previous pandemics in the 20th century reveals that such negative forecasts may be vastly exaggerated.

Prior pandemics have corresponded to changes in architecture and urban planning, and a greater awareness of public health . Yet the psychological and societal effects of the Spanish flu, the worst pandemic of the 20th century, were later perceived as less dramatic than anticipated, perhaps because it originated in the shadow of WWI. Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud described Spanish flu as a “ Nebenschauplatz ”—a sideshow in his life of that time, even though he eventually lost one of his daughters to the disease. Neither do we recall much more recent pandemics: the Asian flu of 1957 and the Hong Kong flu from 1968.

Imagining and planning for the future can be a powerful coping mechanism to gain some sense of control in an increasingly unpredictable pandemic life. Over the past year, some experts proclaimed that the world after COVID would be a completely different place , with changed values and a new map of international relations. The opinions of oracles who were not downplaying the virus were mostly negative . Societal unrest and the rise of totalitarian regimes, stunted child social development, mental health crises, exacerbated inequality, and the worst economic recession since the Great Depression were just a few worries discussed by pundits and on the news.

Other predictions were brighter—the disruptive force of the pandemic would provide an opportunity to reshape the world for the better, some said. To complement the voices of journalists, pundits, and policymakers, one of us (Igor Grossmann) embarked on a quest to gather opinions from the world’s leading scholars on behavioral and social science, founding the World after COVID project.

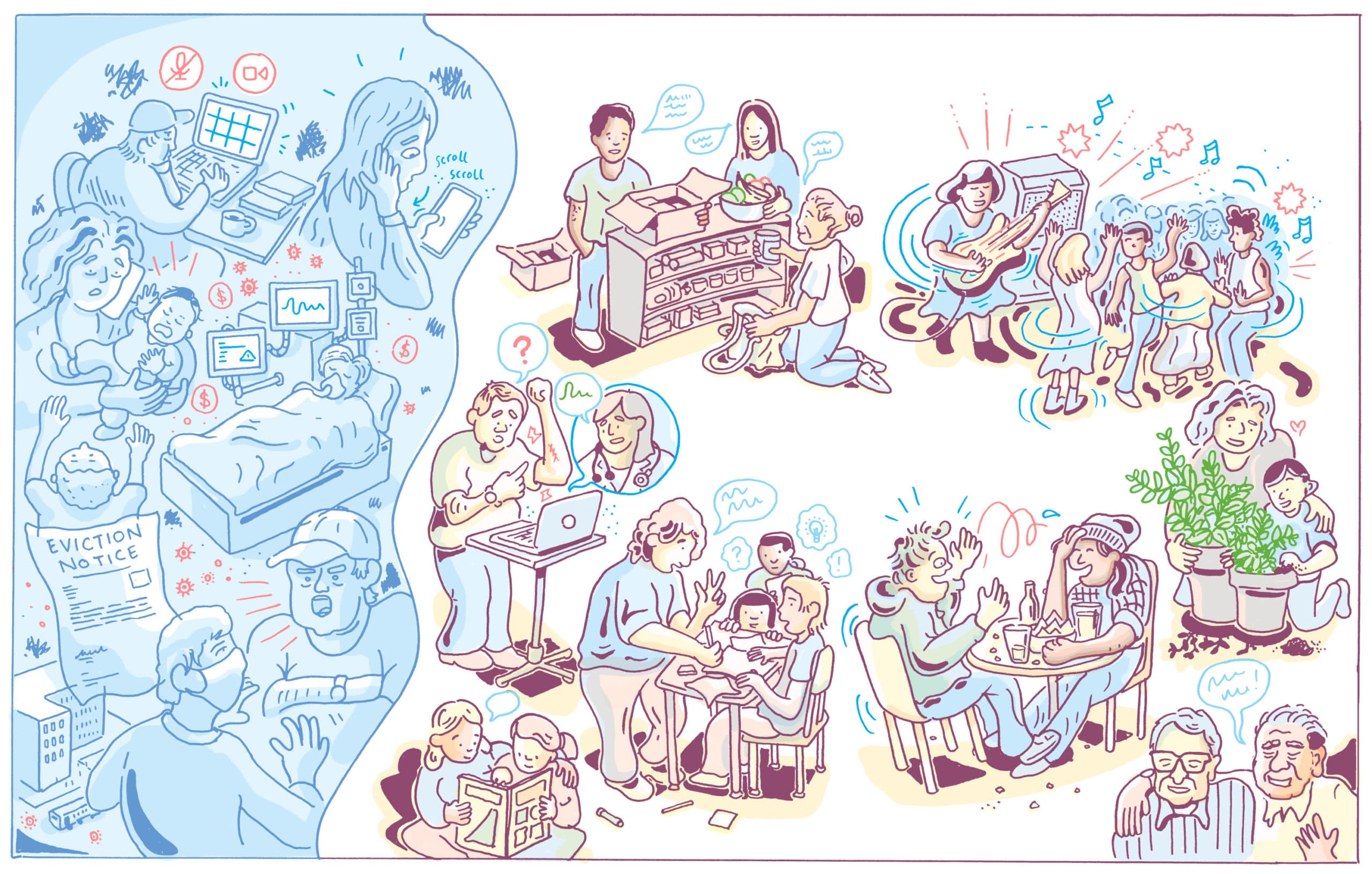

The World after COVID project is a multimedia collection of expert visions for the post-pandemic world, including scientists’ hopes, worries, and recommendations. In a series of 57 interviews, we invited scientists, along with futurists, to reflect on the positive and negative societal or psychological change that might occur after the pandemic, and the type of wisdom we need right now. Our team used a range of methodological techniques to quantify general sentiment, along with common and unique themes in scientists’ responses.

The results of this interview series were surprising, both in terms of the variability and ambivalence in expert predictions. Though the pandemic has and will continue to create adverse effects for many aspects of our society, the experts observed, there are also opportunities for positive change, if we are deliberate about learning from this experience.

Three opportunities after COVID-19

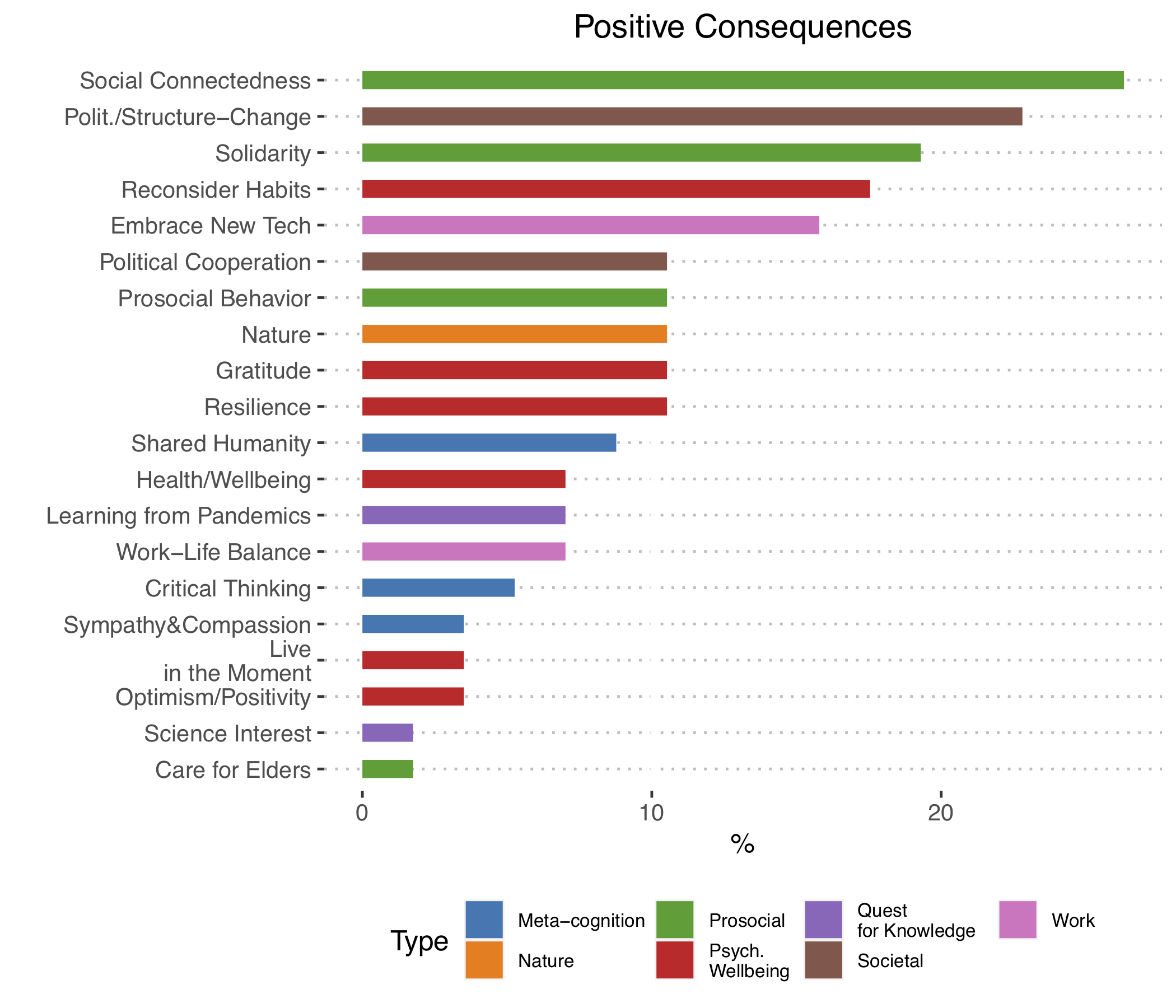

Scientists’ opinions about positive consequences were highly diverse. As the graph shows, we identified 20 distinct themes in their predictions. These predictions ranged from better care for elders, to improved critical thinking about misinformation, to greater appreciation of nature. But the three most common categories concerned social and societal issues.

1. Solidarity. Experts predicted that the shared struggles and experiences that we face due to the pandemic could foster solidarity and bring us closer together, both within our communities and globally. As clinical psychologist Katie A. McLaughlin from Harvard University pointed out, the pandemic could be “an opportunity for us to become more committed to supporting and helping one another.”

Similarly, sociologist Monika Ardelt from the University of Florida noted the possibility that “we realize these kinds of global events can only be solved if we work together as a world community.” Social identities—such as group memberships, nationality, or those that form in response to significant events such as pandemics or natural disasters—play an important role in fostering collective action. The shared experience of the pandemic could help foster a more global, inclusive identity that could promote international solidarity.

2. Structural and political changes. Early in the pandemic, experts also believed that we might also see proactive efforts and societal will to bring about structural and political changes toward a more just and diversity-inclusive society. Experts observed that the pandemic had exposed inequalities and injustices in our societies and hoped that their visibility might encourage societies to address them.

Philosopher Valerie Tiberius from the University of Minnesota suggested that the pandemic might bring about an “increased awareness of our vulnerability and mutual dependence.”

Fellow of the Royal Institute for International Affairs in the U.K. Anand Menon proposed that the pandemic might lead to growing awareness of economic inequality, which could lead to “greater sustained public and political attention paid to that issue.” Cultural psychologist Ayse Uskul from Kent University in the U.K. shared this sentiment and predicted that this awareness “will motivate us to pick up a stronger fight against the unfair distribution of resources and rights not just where we live, but much more globally.”

3. Renewed social connections. Finally, the most common positive consequence discussed was that we might see an increased awareness of the importance of our social connections. The pandemic has limited our ability to connect face to face with friends and families, and it has highlighted just how vulnerable some of our family members and neighbors might be. Greater Good Science Center founding director and UC Berkeley professor Dacher Keltner suggested that the pandemic might teach us “how absolutely sacred our best relationships are” and that the value of these relationships would be much higher in the post-pandemic world. Past president of the Society of Evolution and Human Behavior Douglas Kenrick echoed this sentiment by predicting that “tighter family relationships would be the most positive outcome of this [pandemic].”

Similarly, Jennifer Lerner—professor of decision-making from Harvard University—discussed how the pandemic had led people to “learn who their neighbors are, even though they didn’t know their neighbors before, because we’ve discovered that we need them.” These kinds of social relationships have been tied to a range of benefits, such as increased well-being and health , and could provide lasting benefits to individuals.

Post-pandemic risks

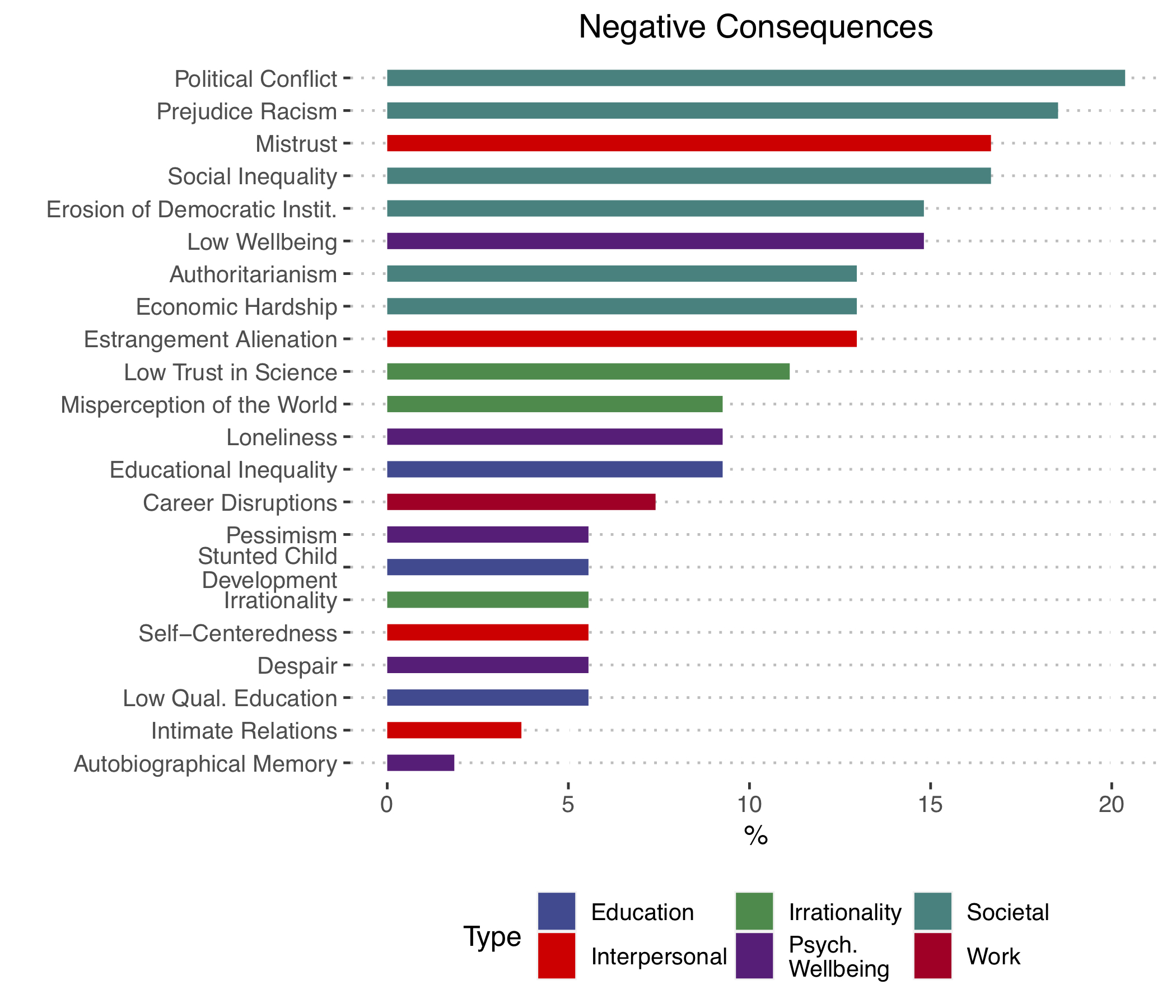

How about predictions for negative consequences of the pandemic? Again, opinions were variable, with more than half of the themes were mentioned by less than 10% of our interviewees. Only two predictions were mentioned by at least ten experts: the potential for political unrest and increased prejudice or racism. These predictions highlight a tension in expert predictions: Whereas some scholars viewed the future bright and “diversity-inclusive,” others fear the rise in racism and prejudice. Before we discuss this tension, let us examine what exactly scholars meant by these two worries.

1. Increased prejudice or racism. Many experts discussed how the conditions brought about by the pandemic could lead us to focus on our in-group and become more dismissive of those outside our circles. Incheol Choi, professor of cultural and positive psychology from Seoul National University, discussed that his main area of concern was that “stereotypes, prejudices against other group members might arise.” Lisa Feldman Barrett, fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences and the Royal Society of Canada, echoed this sentiment, noting that previous epidemics saw “people become more entrenched in their in-group and out-group beliefs.”

2. Political unrest. Similarly, many experts discussed how a greater focus on our in-groups might also exacerbate existing political divisions. Past president of the Society for Philosophy and Psychology Paul Bloom discussed how a greater dismissiveness toward out-groups was visible both within countries and internationally, where “countries are blaming other countries and not working together enough.” Dilip Jeste, past president of the American Psychiatric Association, discussed his concerns that the tendency to view both candidates and supporters as winners and losers in elections could mean that the “political polarization that we are observing today in the U.S. and the world will only increase.”

These predictions were not surprising— pundits and other public figures have been discussing these topics, too. However, as we analyzed and compared predictions for positive and negative consequences, we found something unexpected.

The yin and yang of COVID’s effects

Almost half of the interviewees spontaneously mentioned that the same change could be a force for good and for bad . In other words, they were dialectical , recognizing the multidetermined nature of predictions and acknowledging that context matters—context that determines who may be the winners and losers in the years to come. For example, experts predicted that we may see greater acceptance of digital technologies at home and at work. But besides the benefits of this—flexible work schedules, reduced commutes—they also mentioned likely costs, such as missing social information in virtual communication and disadvantages for people who cannot afford high-speed internet or digital devices.

Share Your Perspective

Curious about the world after COVID? So are we, and we'd love your opinion about possible changes ahead. Fill out this short survey to offer your perspective on the hopes and worries of a post-pandemic world.

Amid this complexity, experts weighed in on what type of wisdom we need to help bring about more positive changes ahead. Not only do we need the will to sustain political and structural change, many argued, but also a certain set of psychological strategies promoting sound judgment: perspective taking, critical thinking, recognizing the limits of our knowledge, and sympathy and compassion.

In other words, experts’ recommended wisdom focuses on meta-cognition, which underlies successful emotion regulation, mindfulness, and wiser judgment about complex social issues. The good news is that these psychological strategies are malleable and trainable ; one way we can cultivate wisdom and perspective, for example, is by adopting a third-person, observer perspective on our challenges.

On the surface, the “it depends” attitude of many experts about the world after COVID may be dissatisfying. However, as research on forecasting shows, such a dialectical attitude is exactly what distinguishes more accurate forecasters from the rest of the population. Forecasting is hard and predictions are often uncertain and likely wrong. In fact, despite some hopes for the future, it is equally possible that the change after the pandemic will not even be noticeable. Not because changes will not happen, but because people quickly adjust to their immediate circumstances.

The future will tell whether and how the current pandemic has altered our societies. In the meantime, the World after COVID project provides a time-stamped window into experts’ apartments and their minds. As we embrace another pandemic spring, these insights can serve as a reminder that the pandemic may lead not only to worries but also to hopes for the years ahead.

About the Authors

Igor Grossmann

Igor Grossmann, Ph.D. , studies people and cultures, sometimes together, and often across time. He is an associate professor of psychology at the University of Waterloo, where he directs the Wisdom and Culture Lab.

Oliver Twardus

Oliver Twardus is the lab manager for the Wisdom and Culture lab and an aspiring researcher. He will be starting his master’s in neuroscience and applied cognitive science in September 2021.

You May Also Enjoy

This article — and everything on this site — is funded by readers like you.

Become a subscribing member today. Help us continue to bring “the science of a meaningful life” to you and to millions around the globe.

Life after Covid: will our world ever be the same?

From cities, to science, to politics, six Observer writers assess how a post-pandemic world will emerge into a new normal

- Coronavirus – latest updates

- See all our coronavirus coverage

Here are some things that the pandemic changed. It accustomed some people – those whose jobs allowed it – to remote working . It highlighted the importance of adequate living space and access to the outdoors. It renewed, through their absence, an appreciation of social contact and large gatherings. It showed up mass daily commuting for the dehumanising drain on energy and resources that it is.

These changes do not add up to the abandonment of big cities and offices predicted by more excitable commentaries, not a future of rural bubbles and of tumbleweed blowing through the City of London, but a welcome shift in priorities. There will always be millions who want to live in cities and millions who want to live in towns and villages, but there are also those for whom these are borderline decisions, with pros and cons on each side.

These decisions might be based on life changes, such as having children. If you no longer have to go to an office daily, you can live further from the city in which it is placed. If the magic spell of the big city, which kept people in the tiny and expensive flats that now look so inadequate, is broken, then you might consider living in cheaper, more relaxed locations that hadn’t occurred to you before. Those ex-urbanites, still valuing social contact and public life, might seek towns and small cities rather than a lonely cottage in a field.

Such changes could help to address, without the pouring of any concrete or the laying of a brick, the imbalance in the nation’s housing that was at breaking point before Covid. On the one hand there are overheated residential markets in London, Bristol, Manchester, Edinburgh and elsewhere. On the other there are towns and small cities with good housing stock, an inherited infrastructure of parks and civic buildings and easy access to beautiful countryside, which through their location suffer from underinvestment and depopulation.

This is not to say that no new homes should be built, nor that there won’t be problems with such a shift. It could simply be gentrification, if done wrong, at a national scale. And this vision assumes that Covid passes, and that it is not one of a future series of equally vicious viruses. But there is at least a chance that the travails of 2020 could lead to a saner approach to the places where we live and work. Rowan Moore, Observer architecture critic

Interaction

The first kiss my baby niece blew me was bittersweet, because like so many pandemic interactions it happened not in person but on camera. Covid means that big chunks of her life have only been seen on a phone screen as she grows into a toddler. And I’m one of the lucky ones: I haven’t had to say goodbye to someone on FaceTime or break the worst news to someone over the phone.

If you live by yourself, you’ve made do without human touch for months on end; if you’re crammed into a small space with your partner, kids and your parents, you may have spent weeks craving time and space not encroached upon by other human beings. Totally different experiences of the same social earthquake: surely they cannot but profoundly change us for the long term?

I’m not so sure. Lockdown, then not-lockdown, then lockdown again have served as a reminder of just how adaptable we are as human beings. I was amazed at how quickly the idea of socialising with friends indoors became a fuzzy memory, then the norm, then distant again. The emotions I felt so acutely back in March – the sharp fear Covid could steal my parents, the communal endeavour of clapping for our carers every Thursday night – soon faded into a new normal, impossible to sustain even though many of the realities have barely changed.

The pandemic has underlined the extent to which digital interaction is no substitute for the real thing. In some ways, I’m more in touch with people than ever thanks to the numerous WhatsApp groups that revived themselves into a constant source of company. But tapping away in a couple of group chats while absent-mindedly watching the latest Netflix offering doesn’t come close to the wonderful feeling of hugging a friend, or spending three hours giving someone you haven’t seen for ages your undivided attention over a meal, or of having a conversation based not just on words but physical cues. I doubt the pandemic will seed a long-term distaste for crowds; if anything, I suspect that, if all goes well with the vaccine rollout, summer 2021 will see a crop of riotous street parties and carnivals.

But a return to life as usual will not mask the emotional toll Covid will have had on so many people. People who suffer from anxiety and depression; women in abusive relationships ; children experiencing abuse or neglect at the hands of their parents: they have had it the worst, and their experiences of isolation and loneliness during lockdown could have consequences for their personal relationships that will not magically disappear with a vaccine.

And that is before you factor in the added strain of the intense financial hardship so many are being forced to endure. As a society, recovering from Covid is about much more than antibodies: it cannot happen without support for those who have experienced its worst financial and mental health impacts. Sonia Sodha, the Observer’s chief leader writer

Britain has had an uncomfortable year in its battle to contain Covid. Failures to test, trace and isolate infected individuals allowed grim numbers of deaths to accumulate while deficiencies in the acquisition of stocks of Personal Protection Equipment (PPE) left countless health workers exposed to danger and illness. However, these deficiencies have been balanced by the manner and striking speed with which our scientists have turned away from existing projects in order to focus their attentions on ridding us of Covid. Their work has earned global praise for its swiftness and precision.

“The Brits are on course to save the world,” wrote leading US economist Tyler Cowen in Bloomberg Opinion about our scientists efforts last summer while the journal Science quoted leading international researchers who have heaped praise on British anti-Covid work. Science in the UK is perceived, correctly, to have done well in facing up to the pandemic.

A perfect example is provided by the UK’s Recovery trial, a drug-testing programme involving more than 3,000 doctors and nurses who worked with more than 12,000 Covid patients in hundreds of hospitals across the nation – from the Western Isles to Truro and from Derry to King’s Lynn. Set up within a few days of the pandemic reaching the UK, and carried out in intensive care units crammed with seriously ill people, Recovery revealed that one cheap inflammation treatment could save the lives of seriously ill Covid patients while two much-touted therapies were shown to be useless at tackling the disease.

No other country has come close to matching these achievements. “We had the people with the right skills and a willingness to drop everything else and contribute to the effort,” says one of Recovery’s founders, Martin Landray of Oxford University. “That made all the difference.” In a nation which had only recently reviled, openly, the concept of expertise, scientists like Landray have restored the reputation of the wise and the informed.

Fiona Fox, director of the Science Media Centre, also points to the willingness of our scientists to communicate. “Time after time, we have asked for comments from leading researchers, epidemiologists and vaccine experts on breaking Covid stories, and despite being inundated with work, they have taken the time to provide clear analyses that have helped to make sense of rapidly changing developments,” she says. “It has been extraordinary.”

And of course, the arrival of three effective vaccines against a disease that was unknown less than a year ago has only further enhanced the image of the scientist. Yes, they may be a bit geeky sometimes, but they have done a lot to help us win the battle against Covid. Robin McKie, Observer Science Editor

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

It may not feel like it at the moment, admittedly. But if this pandemic echoes other defining events in our recent history, from the 9/11 terror attacks to the 2008-09 banking crash, it will leave the political landscape utterly transformed in some respects yet wearily familiar in others.

Last week’s spending review , spelling out how the cost of battling Covid will shape national life for years to come, was a classic example. A public sector pay freeze, plus benefit cuts next April? Well, we’ve been there before; to many families it will feel like austerity all over again.

What’s different this time, however, is that Boris Johnson insists there’ll be no return to austerity-style spending cuts. Instead, taxes will rise. If he actually goes through with threats to target second-home owners or higher earners’ pensions, expect some mutiny in Tory ranks. (The bitter joke among Tory MPs is that they’re implementing more of Jeremy Corbyn’s manifesto than Corbyn ever will.) But the door to a long overdue debate about taxing wealth, as well as income, is at least now open.

The pandemic also seems to be changing what people look for in a leader. The last recession pushed angry, despairing voters towards populists with easy answers; make America great again, take back control. But Covid has been a brutal reminder that in life-and-death situations, competence is everything. Joe Biden isn’t wildly exciting but at least he doesn’t speculate aloud about the merits of drinking bleach. From New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern to Germany’s Angela Merkel and Scotland’s Nicola Sturgeon, the leaders whose reputations have been enhanced by this crisis tend to be pragmatists and consensus-seekers, not excitable culture warriors. Keir Starmer’s rising poll ratings suggest a hunger for steady-as-she-goes leadership in Britain too.

Optimists will hope that this collective near-death experience brings a renewed political focus on what actually makes life worth living, from supportive communities to the beauty of a natural world that sustained many through lockdown. Pessimists, however, will worry that calls to “build back better”, or reset society along fairer and greener lines, could be an early casualty of a hard recession that leaves people focussed purely on economic survival.

For it would be naive not to expect a backlash against all of this. Nigel Farage is already trying to whip one up via his new anti-lockdown party , targeting voters angry at having freedoms curtailed. But if the last crash unleashed an era of radicalism and revolt, it’s not impossible this one will leave people craving a quiet life. After such turmoil, don’t underestimate the longing to get back to normal, even if the normal we once knew is gone. Gaby Hinsliff, Guardian columnist

We know that the spaces from which “culture” emerges won’t look the same after 2020 as they did before. Many theatres, bookshops, music venues and galleries won’t survive the catastrophe of shutdown, and if they do emerge it will be with diminished resources. But what about the attitude and the focus of creativity. Will it be shadowed by the pandemic post-vaccine or will it celebrate liberation?

History suggests both. The terrible mortality, social distancing and economic hardship resulting from the 1918-19 Spanish flu epidemic that followed the war were shaping forces in both the doom-laden experiments of modernism and the high hedonism of the jazz age. The Waste Land and the Charleston emerged within months of each other. TS Eliot wrote much of the former while suffering from the after-effects of the influenza, haunted, as his wife Vivienne noted, by the fear that as a result of the virus, “his mind is not acting as it used to do”. Certainly, that poem’s most memorable lines, with their stress on the mass gathering, read more pointedly from our current vantage point: “Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,/ A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,/ I had not thought death had undone so many./ Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,/ And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.”

But, contrarily, the spirit of the post-pandemic age was equally alive in the bathtub-gin excitement of the Cotton Club, and the rarefied decadence of the Bright Young Things: raucous celebrations of seize-the-day freedoms after the misery of war and virus.

Not much literature or music that directly responds to the current pandemic has yet emerged. Zadie Smith’s brief book of essays , Intimations , hazarded something of what that response might look and sound like. In a memorable phrase, she described the events of this year as “the global humbling”. That moment when we collectively realised that the confident certainties of what we used to call “normal life” were only ever a heartbeat away from unknown threats – and that the US, Smith’s adopted home, having led the world in many things, was now leading the world in death.

Will such experience engender a new and deepening age of anxiety in the books we read and the films we watch? No doubt that apprehension of apocalypse, of environmental emergency, that draws us to The Road or to Chernobyl will become more insistent. But as Eliot also noted, humankind “cannot bear very much reality”. After this year in which the young have been denied so many of their rites of passage – chances to sing, dance, drink or love – we can surely hope for a post-viral creative outpouring of all those things that make us most happy to be alive. Tim Adams, Observer writer

”Imagine there’s no commuting, it’s easy if you try”, is a popular refrain in discussions of the post-Covid world of work predicting the imminent demise of the office. Sometimes it’s combined with the claim that low-earning hospitality and leisure jobs that have dried up mid-pandemic won’t be coming back and so shouldn’t get support now.

These different predictions are likely to be wrong for the same reason: they pay too much attention to crystal balls, and not enough to rear-view mirrors. Yes, the pandemic itself has meant big changes to the world of work. It has changed where some people (generally higher earners) work while hitting the ability of many lower earners to work at all. But imagining a world without lockdowns is best done by focusing on those pandemic-driven trends that reinforce, rather than run against, patterns visible pre-crisis .

So, expect the pandemic’s turbo-charging of retail’s online shift (with Arcadia’s likely administration the latest example) to continue – there will be fewer cashiers and more delivery drivers. But don’t believe the hype on the decline of hospitality and leisure. Workers in those sectors are twice as likely to have lost their jobs or been furloughed as the pandemic has left us spending more on buying things than going out, but the long-term trend is the opposite: hotels and restaurants accounted for a fifth of the pre-pandemic employment surge.

Working from home (or living in the office, as it can feel like) has been the big change for professional Britain. But history warns against the idea that the office is finished. Only one in 20 of us worked entirely remotely pre-crisis. But three times that number worked at home at least one day a week, a trend that was rapidly growing. Hybrid home/office working is the future. But be careful about assuming this transforms Britain’s disgracefully big economic gaps: some will benefit from more choice about where to live but offices in poorer areas, rather than those in central London, may be the ones that end up empty. And remember, we’re only talking about a fraction of the workforce here. Post-Covid, waiters and cleaners won’t be doing their jobs from their spare room or kitchen table.

As well as predicting the future, we should be trying to shape it. Higher pay and more security for the low paid workers who faced the biggest health and economic risks from this crisis would be a good place to start. Torsten Bell, chief executive of the Resolution Foundation

- The Observer

- Coronavirus

- Work & careers

- Vaccines and immunisation

Most viewed

- PERSPECTIVES

- SUBMIT A PERSPECTIVE

- A NEW MAP OF LIFE

THE NEW MAP OF LIFE

AFTER THE PANDEMIC

It is said that culture is like the air we breathe. We don’t notice it until it’s gone.

The COVID-19 pandemic is bringing into focus a once invisible culture that guides us through life. Seemingly overnight, we experienced profound changes in the ways that we work, socialize, learn, and engage with our neighborhoods and larger communities.

For a short time, before new routines and practices replace familiar old ones, we can see with greater clarity the positive and negative aspects of our former lives. The suddenness and starkness of this transformation allows us to examine daily practices, social norms and institutions from perspectives rarely allowed.

The fragility of the global economy becomes glaringly apparent as critical supply chains faulter, unemployment surges, and markets vacillate. Tacit assumptions about health care systems become clear as we see how they function, fail to function, and have long underserved large parts of the population. Just as sure, sheltering in place allows us to appreciate precious details of our lives that we have taken for granted: the appeal of workplaces, the comfort of human touch, dinner parties, travel, and paychecks. Indeed, through ambivalent eyes we also recognize ways that life is better as we shelter in place.

The premise of the New Map of Life:™ After the Pandemic project is that we have a fleeting window of time that affords us an unprecedented opportunity to examine our lives. Going forward, life will be different and by compiling the insights we have today we can inform and guide the culture that will inevitably emerge from our collective experience. Your insights can contribute to the reshaping of social norms, systems, and practices that shape our collective futures.

Since the founding of the Stanford Center on Longevity, we have advocated for a major redesign of life that better supports century-long lives. More recently, we undertook the New Map of Life ™ initiative, which focuses on envisioning a world where people experience a sense of purpose, belonging, and worth at all stages of life. As tragedies unfold before our eyes, we aim to capture the lessons they teach. With your help, we can compile current insights, fleeting thoughts and deeper reflections about the ways we live now so that going forward we bolster, modify and reinvent cultures that improve quality of life for ourselves, our children, and future generations.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the various authors on this website do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs and viewpoints of the Stanford Center on Longevity or official policies of the Stanford Center on Longevity.

Elizabeth Lesser Shares How She Lifted Herself Out of Pandemic Despair

The cofounder of the Omega Institute admits that even as a teacher of mindfulness, sometimes, she is her own worst student.

When it became apparent that a virus was spreading around the globe, my first reaction was one of disbelief: We’ll surely eradicate this before it turns into a pandemic! Soon enough my disbelief morphed into fear, and then horror and grief for those who were sick and dying in Asia, Europe, and slowly, steadily...everywhere. Along with those feelings came a strange kind of optimism, a faith that we all might learn something important. Like when I watched videos of people in Italy under lockdown standing on their balconies holding candles and singing songs of hope into the darkened streets. Or as travel ceased and traffic stood still and the world got a little quieter, the air a little cleaner—I could almost hear the trees breathing sighs of relief.

In the early spring of 2020, when the pandemic took hold here in the United States and life as we knew it ground to a halt, I wondered, even with the trauma and loss, could this be the Great Slowdown we needed? People retweeted the quote “Mother Nature has sent us to our rooms.” Could that message portend a teachable moment? Maybe doing less, and doing with less, would reveal the value of enough instead of chasing after more, more, more. Maybe now we’d start to truly appreciate the people whose work keeps us alive and well: the farmers, truckers, grocery baggers; the staff who work in our hospitals; the home health aides who care for our parents; the daycare instructors and school teachers who safeguard our children’s future. And maybe, just maybe, the pandemic would finally confirm for us thick-headed humans this plain truth: What happens to even just one of us affects all of us.

My grand optimism began to waver as the weeks of isolation became months and Covid-19 cases doubled, then tripled. Schools closed. Hospitals ran out of masks and ventilators; millions of people got sick, and hundreds of thousands died. People lost their jobs, their homes, their loved ones, their mental health, their way of life. Almost no individual, community, or business was untouched by fear or pain or loss, including my own nonprofit center, which for 40 years had been teaching people to meditate, to heal, to spin trauma into the gold of growth.

.css-meat1u:before{margin-bottom:1.2rem;height:2.25rem;content:'“';display:block;font-size:4.375rem;line-height:1.1;font-family:Juana,Juana-weight300-roboto,Juana-weight300-local,Georgia,Times,Serif;font-weight:300;} .css-mn32pc{font-family:Juana,Juana-weight300-upcase-roboto,Juana-weight300-upcase-local,Georgia,Times,Serif;font-size:1.625rem;font-weight:300;letter-spacing:0.0075rem;line-height:1.2;margin:0rem;text-transform:uppercase;}@media(max-width: 64rem){.css-mn32pc{font-size:2.25rem;line-height:1;}}@media(min-width: 48rem){.css-mn32pc{font-size:2.375rem;line-height:1;}}@media(min-width: 64rem){.css-mn32pc{font-size:2.75rem;line-height:1;}}.css-mn32pc b,.css-mn32pc strong{font-family:inherit;font-weight:bold;}.css-mn32pc em,.css-mn32pc i{font-style:italic;font-family:inherit;} “What happens to even just one of us affects all of us.”

As 2020 came to a close, I began to wonder if my dream of the Great Slowdown was becoming a sorrowful nightmare: the Great Meltdown. As a teacher of mindfulness, sometimes I am my own worst student; life during lockdown tested me greatly, and watching the news or doom-scrolling through social media didn’t help. I began to flunk out of inner-peace school, started reacting to stress in decidedly unenlightened ways, yelling at the TV or exploding in anger during interminable Zoom meetings.

I gave in to despair when we had to let go of another staff member at work, or when I couldn’t see my kids, who live in far-flung places. I had stopped accessing my “balcony brain”—that part of myself that can calmly observe any situation, pause before reacting, and make wise, compassionate decisions. I was spending more time in my “basement brain,” heeding the vigilant, volatile caveman within. Eventually, my burnout caught up with me, and I landed in the emergency room with a gastrointestinal issue. It was then that my darling husband suggested I try some of my own medicine—the stuff I have written several books about. “You know,” he said gently, “things like meditation and exercise. Things for your trauma and grief. Things for your soul.” Duh!

So here’s what I did. I turned to the words of some of my greatest teachers. I keep a basket of their quotes on my desk. I’m always adding to it—beautiful lines from poets, mind-blowing bits from scientists, motivation from activists, quiet wisdom from spiritual leaders. I often choose one to guide me through the day. This time, I decided that whatever quote my hand touched first would serve as my GPS back into what I call the four landscapes of the human journey: mind, body, heart, and soul.

The first words I picked gave me goosebumps: “Today’s mighty oak is yesterday’s nut that held its ground.” The phrase is attributed to Rosa Parks, and I felt as though she had reached down from the heavens to remind me that everything I needed was already within me. I could be that little acorn again and reroot and rise strong. I knew how to do that. I had done so before in other difficult times. I had held my ground in the shattered aftermath of divorce and come out the other side a stronger and more empathetic person. I had rooted myself in my inner strength when I was my sister’s bone marrow donor. And when we lost her, I found in those ashes the true heart of friendship. Here I was again, trying, like so many of us, to reemerge from the pandemic with lessons learned, inner strength, and something of value to offer.

I followed Mrs. Parks’ guidance and went back to the tools that never fail me: Meditation to activate my “balcony brain” and lift the veil from my clouded mind. Exercise to reclaim my body and physical vitality. The simple prayer of putting my hand on my heart and feeling flooded with forgiveness and tenderness, hope and gratitude. Walks in nature and dips back into my favorite spiritual texts to reconnect with my all-knowing soul. As I felt my strength returning, I was reminded how despair and negativity can spread like a virus, too. When they do, taking the soul’s vaster view and being an agent of uplift feels almost revolutionary. Doing so is an act of sanity and an offering of healing.

Historically, pandemics have jump-started innovation or they have slid humanity backwards into oppression. This is our era; we get to choose. Life after Covid-19 does not have to be a Great Meltdown, or a Great Slowdown. Maybe, just maybe, it will be a Great Wake-up—a global event that breaks us open and waters the seeds of our best selves. Because each one of us can be that acorn, holding our ground, lifting our sights, and, together, becoming a forest of mighty oaks.

Elizabeth Lesser is the author of Cassandra Speaks: When Women Are the Storytellers, The Human Story Changes as well as the bestselling Broken Open: How Difficult Times Can Help Us Grow and Marrow: Love, Loss & What Matters Most . She is the cofounder of Omega Institute, has given two popular TED talks, and is a member of Oprah Winfrey’s Super Soul 100.

From The Magazine

The Essential Guide to Wigs

10 Ways to Spark Change in Your Community

Spending Less Added Value to My Life

How One Woman Found Freedom—and Joy—in Failure

She Found Love Where She Least Expected It

Expert Tips on How to Shift Your Perspective

Facing Childhood Trauma Led a Grown Son to Healing

One Woman Discovers That Joy Can Be Easy

How to Make Your Life More Joyful—Right Now

4 Perfect HolidayCocktails and Mocktails

The Power of the Thank-You Note

We Asked 10 People To Imagine Life After The Pandemic. Here's What They Said

Copy the code below to embed the wbur audio player on your site.

<iframe width="100%" height="124" scrolling="no" frameborder="no" src="https://player.wbur.org/cognoscenti/2021/03/17/imagining-life-after-the-covid-19-pandemic"></iframe>

- Cloe Axelson

As more and more people get vaccinated, the number of COVID-19 infections and deaths are finally declining. We know this pandemic won’t last forever.

But — what happens next? Do we just pick up where we left off in March 2020? Or have things changed in a fundamental way?

We asked 10 people to imagine life after the pandemic.

What will work look like after COVID? What about parenting? Friendship? Faith? Will our understanding of public health change, as epidemiologists race to get ahead of the next pandemic?

The truth is, nobody knows exactly what comes next. Uncertainty continues to reign. But for the first time in a long time, it feels like we can reasonably contemplate the future — we are no longer locked in the “perpetual present.”

Read through each contributor's short essay below, or jump around to different topics using this navigation:

- Friendship | Joanna Weiss

- Health | Sandro Galea

- Aging | Julie Wittes Schlack

- Parenting | Sara Petersen

- Faith | Taymullah Abdur-Rahman

- Education | Neema Avashia

- Work | Julie Morgenstern

- Community | Roseann Bongiovanni

- Creativity | Desmond Hall

- Climate | Philip Warburg

I’m Ready To Double Down On The Joys Of Physical Friendship

In the beginning, we had Zoom, and it was fine: virtual happy hours and online game nights that kept friendships alive when we had to be physically apart. But the pandemic separation couldn’t last.

In late spring, I took my first illicit walk with friends; we wore masks and glanced sideways to see if we’d be shamed. By summer, we were venting our frustrations during walks around a pond, holding birthday dinners outdoors, taking socially-distanced selfies with the timers on our phones. When winter came, we layered up like ice fishermen and huddled around fire pits on 30-degree nights.

I want to double-dip in the guacamole. I want to sip your cocktail to see if I like it, too. Joanna Weiss, Editor, Experience Magazine

We’ve needed each other, and that’s good to know. One of the hardest things about COVID has been the way it rendered friendship dangerous — so many transmissions springing from in-person gatherings, as friends came together despite the directives. You can condemn all of those people as cavalier about public health. Or you could see their lapses as a feature of humanity.

We’ve learned, this past year, that connection isn’t the same when it’s remote. And while many of us have broken the rules at least once or twice, we should acknowledge the lengths we’ve gone to see each other in relative safety.

When the COVID threat is gone, I predict that we’ll double down on the joys of physical friendship. I want to live dangerously with my besties. I want to double-dip in the guacamole. I want to sip your cocktail to see if I like it, too. I want to scream together into a karaoke microphone. I’ll pick the first song: “With a Little Help From My Friends.” -- Joanna Weiss , Editor, Northeastern University's Experience magazine

We Need To Think About 'Health' In A New Way

In some ways, COVID-19 will be remembered as a triumph of biomedical science. We developed safe and effective vaccines — something that usually takes a decade or more — in less than a year. And, despite a number of stumbles, improved therapeutics reduced mortality from the virus in hospitals more than fourfold in a matter of months.

But COVID-19 provided, even more memorably, a terrifying and revealing view of our failure to create a world that generates health.

Once this pandemic ends, we’ll undoubtedly be having more conversations about how to prevent future pandemics, and ensure a healthier future. But will we be thinking about health in a bigger sense?

Fundamentally, health is not health care. Sandro Galea, Dean, Boston University School of Public Health

Fundamentally, health is not health care. Decades of underinvestment in healthy environments, adequate education, safe workspaces and livable wages resulted in a country that was unhealthy and vulnerable to the ravages of a novel virus. The U.S. has had the highest per capita rate of COVID-19 infections throughout the pandemic.

This moment should teach us that avoiding the next pandemic will require us to rethink how we approach health, so there are no haves and have nots. It’s recognition that we cannot be healthy, unless we build a world with safe housing, good schools, livable wages, gender and racial equity, clean air, drinkable water, a fair economy.

It’s time to change how we think about health. -- Sandro Galea , Dean, Boston University, School Of Public Health

The Pandemic Deepened The Lessons Of Aging

My husband and I are in our late 60s. Fed, housed, and able to freelance, we’ve weathered the past year with gratitude and relative ease. But like many of our peers, the pandemic has intensified our feelings about how we want to live the rest of our lives, in intentional community. Our choices feel quite personal, but they are representative of emerging trends.

In a post-pandemic future, we can expect to see the biggest change in where and with whom the elderly live. With 40% of all fatalities, the virus’s impact on residents of nursing homes has been earth-shaking, fueling people’s desire to age in place or live in settings where mutual aid is the norm. Stunned by the isolation of the pandemic, most of the new recruits to our co-housing community have been people over 60. Local programs supporting in-home care are on the rise, and state and federal programs paying family caregivers are also likely to expand.

Technological advances will also pave the way for aging in place. Telehealth is more widely accepted, and devices like smart speakers will soon notify loved ones if you call out for help. Indeed, the pandemic has highlighted our intergenerational interdependence. With schools and daycares closed, working parents have moved in with their parents so that they can help mind the kids, and many adult children, having been deprived of the ability to see their quarantined loved ones, are determined to pre-empt that scenario in the future.

Don’t take your family and friends for granted. Protect your health. Accept that you’re going to die and live accordingly. Julie Wittes Schlack, Writer, Retired Marketing Executive

Will market volatility make it less likely that people will retire? Or will the COVID-induced knowledge of our own vulnerability fuel our urgency to pursue what we value versus what we’re paid for? I don’t know. But I do know that COVID has deepened the lessons that aging inevitably bestows: Don’t take your family and friends for granted. Protect your health. Accept that you’re going to die and live accordingly. -- Julie Wittes Schlack , Writer

Mothers Continue To Hold Up A Broken System

I never harbored any illusions about living in a culture that values mothers. From day one, my experience as a mom has been peppered with moments of rage and periods of existential crisis. I love the love of motherhood, but the work of mothering is mostly unsupported and un-respected. The nonstop parenting, teaching, cooking, cleaning that mothering has entailed during the pandemic has confirmed that this type of labor is also, for me, largely a drag.

Although the beauty of motherhood is widely celebrated on Instagram and elsewhere, our primary value lies in our ability to raise the next generation of workers and consumers. As the pandemic has shown, mothers’ needs don’t really seem to matter. Our needs don’t impact the bottom line.

The pandemic calcified my fury that mothers are expected to hold up the whole of a very broken system, while being given nothing in return. Sara Petersen, Writer

The pandemic calcified my fury that mothers are expected to hold up the whole of a very broken system, while being given nothing in return. In the past year, we’ve seen a flurry of essays and reporting showing that women and mothers have been disproportionately burdened with the impossible task of keeping society afloat (the latest New York Times series is appropriately titled, “ The Primal Scream .”) The coverage is affirming and necessary, but not a single mother I know has been surprised about any of the awful statistics or heartbreaking personal stories.

When this is over, I’m looking forward to no longer being the sole provider of all things to my kids. But I also wonder if the tidal wave of momentum inspired by the pandemic will carry us through to something better than think-pieces.

We need equal and fair pay for mothers. We need humane prenatal and postnatal care, and paid parental leave legislation. We need to reform our racist health care system that has led to countless Black mothers’ deaths. We need to end the debate on whether women’s reproductive rights are actual rights. And we need to radically rethink our capitalist system, which uses mothers and other care workers to uphold the primary concerns of buying and selling, while denying them adequate compensation — or even cultural respect for their indispensable work.

I wonder if women’s rage will coalesce into action. I hope so. -- Sara Petersen , Writer

The Pandemic Forced Us To Take Faith Into Our Own Hands

I spent many nights in the last year contemplating God’s wisdom and purpose, while fielding the despair and weariness of many Muslims who sought my counsel. They wanted to know, was COVID a pandemic or the plague, and what was the difference? Was it God’s wrath or God’s cleansing? Was there a collective spiritual remedy to make it all go away?

As we begin to see a light at the end of the tunnel, I wonder if and how our faith as Americans has changed.

It was no coincidence that the height of the pandemic in Massachusetts last spring struck during the Holy days of all three Abrahamic faiths. Easter, Passover and Ramadan came and went in our homes. We had to learn to celebrate without the pomp of public worship. People who attended church, temple and mosque — but never took it upon themselves to utter their own personal prayers — were forced to petition God themselves.

God forced us to stop our schedules to give us a moment to take faith into our own hands... Taymullah Abdur-Rahman, Imam

I watched my own teenage children reluctantly read the Quran aloud at home for the Eid Holidays (without the help of the entire mosque). As life returns to normal, I suspect we’ll have a deeper appreciation for our respective worship-communities and the spaces of comfort they provide us.

I also think the goals of the American faithful have shifted slightly. We want a little less of the world now, and more authentic connections with real people. God forced us to stop our schedules to give us a moment to take faith into our own hands — and for the most part we did.

Now I believe God will allow us to embrace one another again, both literally and figuratively. -- Taymullah Abdul-Rahman , Imam, Massachusetts Department of Correction

I Worry Education In A Post-COVID World Won't Change Enough

My greatest fear is that K-12 education in a post-COVID world will not change enough. As an 8th grade teacher, the past 12 months have completely changed how I approach my work.

In-person, Ms. Avashia was all about urgency and rigor and content, content, content. Pandemic-teaching Ms. Avashia moves much more slowly with her students.

Now, I focus my efforts on deep learning, instead of coverage of pages of standards. Each day, we work through one meaningful task, instead of trying to speed through three or four. We play more in class — using riddles or visual puzzles, telling jokes in the chat, changing our Zoom profile pictures, to make each other laugh. I’ve even dressed up in costumes multiple times this year just to bring kids some moments of humor.

Teaching during the pandemic has pushed me to be so much more human with my students, and to teach into their humanity. And that, at its core, is completely different from how education has traditionally been structured in our society.

I believe deeply in the democratic cornerstone of public education. But we have never succeeded in fulfilling its promise for all of our students, particularly those students most impacted by racial and economic injustice in our country.

Our school buildings have been sites of over-policing of students’ bodies, of adultifying and criminalizing adolescent behavior, of reducing student learning down to what can be demonstrated on standardized tests.

We have an opportunity to walk away from those practices forever. To build educational settings that are grounded in students’ humanity, and designed with their voices, needs and interests at the center. To ensure that our schools are structured and staffed to prioritize relationship-building, robust mental health services and targeted academic supports. We can affirm the notion that schools are cornerstones of both our democracy and our communities, by fully funding the work that we as a society are asking them to do.

We can affirm the notion that schools are cornerstones of both our democracy and our communities... Neema Avashia, Teacher, Boston Public Schools

We can do all of this. We should do all of this. The question is: Will we? -- Neema Avashia , Teacher, McCormack Middle School

COVID Forced Companies To Be More Flexible. Will They Harness The Lessons Learned?

The “culture of time” at many companies wasn’t healthy before the pandemic. Some organizations were trying to address bad habits (no time to think, everything-gets-done-by-meetings culture), before new problems like Zoom fatigue and FOLO (Fear Of Logging Off) took hold.

The pandemic accelerated a comeuppance about how the workplace can and should evolve. I think the lessons we learned this year will almost certainly lead to greater flexibility in the long term.

This year proved that a lot of work can be done remotely. It also made clear the handful of things better done in person — bonding, mentoring and new relationship building. Companies will need to bring people together regularly to ensure the kismet that happens in 3D.

The pandemic accelerated a comeuppance about how the workplace can and should evolve. Julie Morgenstern, Author, Productivity Expert

Every worker needs time and space for quiet work, time and space for meetings, and time and space for informal and more casual communication. This was true pre-pandemic, and it’s still true. Future workspaces are likely to reflect these needs: large library-like areas where people can go to do their thinking (like the quiet car on a train); lots of formal and informal meeting areas; and administrative spaces to deal with email and chat with coworkers.

Back-to-back meetings — 7 to 10 Zooms a day — is not an effective way to work. It leaves no time to think, or to actually do the work generated in those meetings.

Companies seem to have finally learned that their employees are whole people. Work is part of their lives, and their lives beyond work are essential and valuable to their well-being. In our post-COVID world, I suspect the role of chief people officer and chief wellness officer will evolve, and be seen as a critical role for a healthy organization.

COVID forced organizations to change. It forced them to be more flexible, and that experience highlighted what went missing in a 100% remote environment. The job of leaders is now to stop, reflect and embrace what we discovered in the last year, and consciously build workplaces and workspaces that harness those lessons, to enable companies to achieve their goals and workers to feel fulfilled. -- Julie Morgenstern , Productivity Expert , Author

We Must Do Right By The Communities, Including Chelsea, That Suffered The Most

I’ve lived in Chelsea my whole life, but I don’t remember my community ever being in the news as much as it was during the first peak of the pandemic. With the highest infection rate in Massachusetts — and blocks’ long lines of people waiting for food — Chelsea was on display for the world to see. Even my family in Argentina saw news reports of our city being slammed by the raging pandemic.

During those difficult days, people opened up their hearts for the residents of our community. Those of us involved in addressing the coronavirus pandemic in Chelsea, received an outpouring of support through donations, volunteering, well wishes and prayers for recovery and hope.

Other low-income, ethnically and racially diverse communities like Chelsea faced the same wrath. Years of structural oppression and racism leading to health, environmental and economic disparities, have made the effects of COVID-19 so much more pronounced.

My post-pandemic hope is that the hearts and minds of those outside of these cities remember how much communities like Chelsea have sacrificed. Will you remember us in six months? Six years? Sixteen years from now?

Will the people of Massachusetts continue to have communities like Chelsea in their hearts and minds? Roseann Bongiovanni, Executive Director, GreenRoots

Will the people of Massachusetts continue to have communities like Chelsea in their hearts and minds? Will you reflect on our disproportionate environmental and industrial burdens, poor public transportation, food insecurity, housing instability and low wages for essential workers? Will others say, “We can shoulder a little bit of the burden, so it’s not all on the backs of low-income communities of color?”

We must learn from the past year, and from the reasons for Chelsea’s soaring infection rates. We must pass laws to protect environmental justice communities. We must say “no” to new toxic facilities. We must prioritize the health and well-being of all people, but particularly those who have faced oppression, discrimination and racism, which caused these health disparities. -- Roseann Bongiovanni , Executive Director, GreenRoots

Will Art Remain The Unifying Force It’s Always Been?

I’m sitting behind my screen, fractured from the world.

I don’t feel the need to see other people as much as I did earlier in the pandemic. Has something happened to me on a molecular level? Is the isolation hitting other writers and artists the way it’s hitting me?

We already live in a world of separate platforms. News broadcasts spin the same events in different ways for different people. The platforms dictate what we see based on what the platforms think we want to see. They strut the arrogance of knowing us better than we do. And now the pandemic has further alienated all of us.

I hope the isolation we’ve endured this year won’t stunt our ability to connect to each other. Desmond Hall, Novelist, Visual Artist

This worries me, because I love when artists create the specific that’s felt universally. I wrote a book about a boy and his family in rural Jamaica . So far it has resonated in other parts of the world. But if we continue to be so isolated will we be too separated to partake in varied experiences?

It was only a short while ago when some Hollywood execs deemed a movie like “Black Panther” was too ethnic to have widespread appeal. They doubted that the specific had universality. The film proved them wrong, but what if we continue to grow apart, divided? Will some art be discarded as irrelevant because large swaths of people can’t relate, can’t see the universality?

I believe in art as a unifying force, as a medium that reveals our commonalities and reasons to strive together. I hope the isolation we’ve endured this year won’t stunt our ability to connect to each other. -- Desmond Hall , Author, Visual Artist

Behavior Change Won't Be Enough To Avert Climate Catastrophe

With more than half a million lives lost in the U.S., the COVID crisis has yielded a sobering lesson about human resistance to change, even in the face of devastating consequences.

Wearing masks in public? A no-brainer. Avoiding large indoor gatherings? Ditto. Yet when official directives and common sense have impinged on individual choice, too often they have collided with indifference, indignation and defiance.

Some wonder if there are lessons to be learned from the pandemic as we seek to avert the worst ravages of climate change. With many working remotely rather than traveling daily to their offices, reduced commuting has doubtless contributed to the past year’s drop of more than 10% in U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. It’s a pretty sure bet, though, that commuters will refill our highways, with more people than ever traveling by car for fear of infection on public transit.

Air travel, too, is likely to rebound as business trips come back into vogue and leisure travelers take to the skies.

The COVID crisis has yielded a sobering lesson about human resistance to change, even in the face of devastating consequences Philip Warburg, Senior Fellow, Boston University Institute Of Sustainable Energy

Rather than placing our bets on behavioral change, we need to demand of government and industry what we cannot expect of ourselves. All levels of government must require a true gearing-up of renewable energy as our primary electricity source.

In addition, the federal government must mandate a shift to cleaner, leaner motor vehicles — a challenge bigger than simply electrifying the behemoths that now roll off our production lines. And governing bodies at all levels must embrace an unprecedented commitment to energy justice, making it possible for low-income people to make their homes more efficient, buy energy-efficient appliances, and install solar power on their rooftops and in their communities.

It would be folly to rely on new patterns of human behavior emerging from the COVID catastrophe to address climate change. We need to make an all-out investment in retooling the engines of our society. -- Philip Warburg , Senior Fellow, Boston University Institute Of Sustainable Energy

Amy Gorel, Lisa Creamer and Kathleen Burge helped with the production of this piece. The audio essay was was produced by Cloe Axelson, with help from David Greene; it was mixed by Michael Garth.

Follow Cognoscenti on Facebook and Twitter .

- Molly Colvin: Why You Can't Shake Pandemic Anxiety

- On Point: Coronavirus, 1 Year Later: How The Pandemic Has Changed Us

- Lisa Creamer and Laney Ruckstuhl: By The Numbers: What We've Lost, A Year Into The COVID-19 Pandemic

Cloe Axelson Senior Editor, Cognoscenti Cloe Axelson is an editor of WBUR’s opinion page, Cognoscenti.

Advertisement

Find anything you save across the site in your account

All products are independently selected by our editors. If you buy something, we may earn an affiliate commission.

The World We Want to Live in After COVID

By Dhruv Khullar

In 1909, the French ethnographer Arnold van Gennep published a book called “ The Rites of Passage .” In it, he explored the rituals that cultures use to transition people from one stage of life to the next. Birth, puberty, graduation, religious initiation, marriage, pregnancy, promotions, the seasons—we’re always on the threshold of one phase or another. How do communities shepherd individuals from the pre- to the post-?

Van Gennep argued that certain universal principles underlie rites of passage across cultures and eras. First, there’s the “pre-liminal” phase, in which “rites of separation” detach individuals from their earlier thoughts, feelings, and perspectives: the Old You dies. Next comes the “liminal” phase, a volatile interregnum that’s simultaneously disorienting and ambiguous, destructive and constructive, during which “rites of transition” open up the possibility of a new and different future. Finally, in the “post-liminal” phase, the “rites of incorporation” allow one to reënter society somehow changed. A New You is inaugurated. “Life itself means to separate and to be reunited, to change form and condition, to die and to be reborn,” van Gennep wrote. “It is to act and to cease, to wait and to rest, and then to begin acting again, but in a different way.”

Van Gennep’s observations were a landmark in the nascent field of anthropology. “Elements of ceremonial behavior were no longer the relics of former superstitious eras,” the anthropologists Richard Huntington and Peter Metcalf later wrote, but “keys to a universal logic of human social life.” In the century since, scholars have applied van Gennep’s framework not just to individuals but to societies in times of turmoil and transformation. Famines, wars, political revolutions, economic downturns, civil-rights movements—societies, too, move from one way of life to another, often experiencing intense periods of renunciation, restructuring, and rebirth.

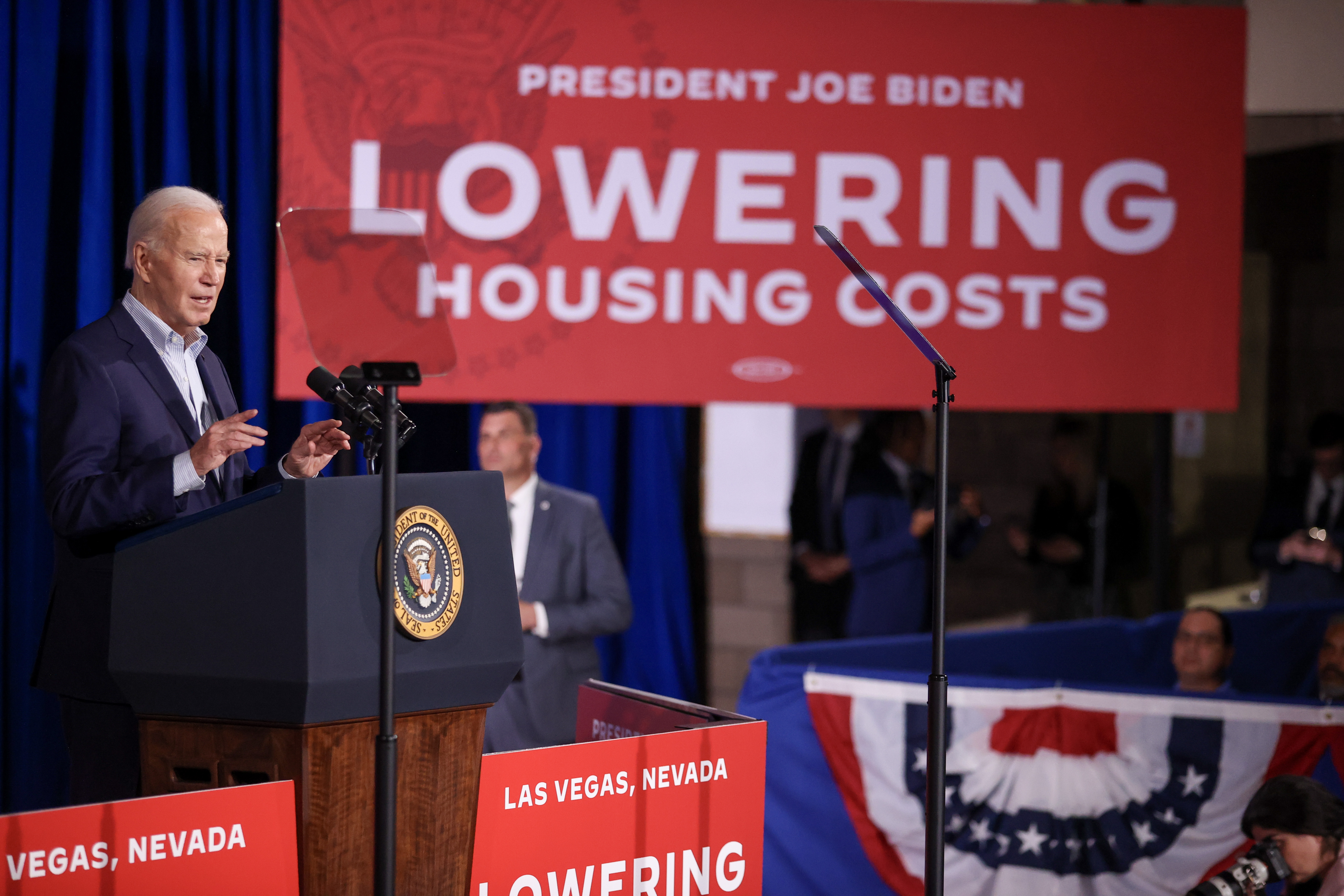

2020, when the pandemic began, was a pre-liminal year—a headlong, vaccine-less descent away from normality and into calamity. We were torn from our established ways, undergoing separation, loss, and upheaval. 2021 was a liminal year—neither here nor there, not quite normal but not wholly abnormal, either. The inauguration of Joe Biden , the widespread availability of vaccines, and the return of weddings, dining, travel, and sports all coexisted alongside vaccine holdouts, breakthrough infections, new variants, booster shots, and regional surges.

Today, Omicron might make it feel as though we’re still squarely in the liminal phase. But, in fact, we may soon be tipping into a post-liminal paradigm. Omicron’s extraordinary contagiousness—combined with rising vaccination and booster rates—could mean that, in the coming months, nearly all Americans will have some level of immunity to COVID . Repeat infections and breakthrough cases will still occur, but, as our individual and collective immunity broadens, these will become milder and less disruptive. The influenza pandemics of the twentieth century each lasted around two years; now, twenty-one months into our battle with the coronavirus, Omicron is accelerating what could be this pandemic’s final chapter. It’s becoming possible to ask, and perhaps answer, some broad questions: Where will we end up in our attitudes toward ourselves and the social web in which we live? Who will we be on the other side of our transition?

The coronavirus crisis is first and foremost a health crisis, and many of the most obvious changes in our attitudes have to do with health. Some of us have come to reflect more regularly on our age and medical conditions. We’ve gained familiarity with obscure scientific jargon, from PCR tests to mRNA. We meditate on the trade-offs involved in social events, examine the threats we pose to others (and vice versa), and judge people for their choices. Americans differ hugely on what to think and do about all this—the behavior of people in one community can seem unfathomable to those in another—but, at least for now, health has shifted from a narrow individual consideration to a more expansive, social one. Going to work, attending a concert, hosting a dinner party, boarding a flight—if you have a cough, a fever, or just the sniffles, these activities now carry an ethical dimension. Will this remain true after the acute threat of COVID -19 has subsided? We may return to inflicting colds, flus, and various G.I. bugs on one another—or, possibly, we’ll adopt some version of the physician’s oath to do no harm.

The sense that making others sick is an action we’ve taken—and that, conversely, it’s within our power to avoid becoming agents of contagion—reflects a more general paradox of the pandemic. Since COVID arrived, we’ve been both powerless and empowered. Many aspects of our lives have been changed by events beyond our control; at the same time, we have sometimes been pushed to make consequential decisions and chart our own course. Over the past two years, for instance, Americans have quit their jobs in record numbers; in some cases, they’ve been forced to do so—perhaps by medical vulnerability, or unprecedented disruptions in schooling—while, in others, the pandemic’s chaos presented an opportunity to reëvaluate priorities. Regardless, faced with historical circumstances, they made big changes. In this crisis, as in many rites of passage, we don’t just passively recite our lines; we write them, taking vows that may reverberate for decades.

One of the questions we face now is whether we can make such changes on a social level, in addition to an individual one. The pandemic’s school disruptions are the result not just of a novel virus but of years of underinvestment that have yielded underpaid teachers, crowded classrooms, and poorly ventilated buildings. We’ve seen the same pattern in many aspects of our pandemic experience. Decades of investment in basic science allowed American scientists to race from genomic sequencing to an effective COVID vaccine in less than a year—but, during the same period, a public-health system that had been neglected for decades hampered our ability to contain the virus at every turn. We’ve made real changes in our lives. Can we make them in our society, too, building capacity so that our institutions can be more resilient and flexible?

The pandemic has posed similar questions for the world as a whole. COVID -19 struck during the seventy-fifth anniversary of the creation of the United Nations, and arrived at a moment characterized by a sharp rise in nationalism and a broadening skepticism about the international arrangements that have governed since the Second World War. Even before the virus, the multilateral system of international coöperation was fraying. After the 2008 financial crisis, Americans had grown increasingly suspicious of globalization and frustrated by their leaders’ failure to address its consequences: inequality, job displacement, social atomization. Now the coronavirus has shown that globalization moves not just goods and people across borders but pathogens, too.

In March, the National Intelligence Council released a report arguing that, in the coming years, the world will face global crises—pandemics, extreme-weather events, technological disruptions—with growing frequency. At the same time, greater international fragmentation and tension will impede our ability to respond to them. The report outlined several possible futures. In the optimistic scenario, called the “renaissance of democracies,” the world settles into a new equilibrium characterized by technological progress, rising incomes, and responsive democratic governance, led by the U.S. and its allies. In another future, “a world adrift,” the international system is “directionless, chaotic, and volatile”; global problems are largely ignored, and multilateral institutions lose their influence.

At a global level, as at the national one, the health crisis of the pandemic has put another preëxisting crisis into sharper relief. Effective pandemic response requires coördination across nations; this is the work of the World Health Organization, of which America has long been the largest funder. In 2019, the U.S. contributed more than four hundred million dollars to the W.H.O., but in April, 2020, Donald Trump announced that the U.S. would stop its funding. For much of the year, the U.S. also declined to join COVAX , the world’s primary global vaccine-distribution mechanism. Today less than nine per cent of people in low-income countries have received a single dose of a COVID vaccine; the rise of ever more concerning variants, such as Delta and Omicron, is due, in part, to a failure of the U.S. and other wealthy countries to vaccinate the world.

Recently, the G-20—a forum comprising nineteen nations and the European Union, which together account for ninety per cent of the world’s economic output—proposed key steps for strengthening the global response to future infectious threats: higher and more consistent funding for the W.H.O.; greater collaboration between governments and the W.H.O. on data collection, humanitarian support, and vaccine development; and the establishment of global norms for the reporting of emerging pathogens. Will countries unite in making such changes? That depends, in large part, on their willingness to act multilaterally—to see that their own security is interwoven with the security of others. It’s an issue that’s larger than the virus. COVID -19, like the Second World War, has created a hinge in the history of the world, which could swing either toward greater cohesion or toward disarray.

In 1954, a researcher named Muzafer Sherif conducted what would become one of the most famous experiments in social psychology. Sherif was interested in the dynamics of group conflict: how easily loyalties form; how little it takes for rival factions to quarrel; what, if anything, can be done to repair relations. As my colleague Elizabeth Kolbert wrote recently, in a piece on political polarization , Sherif invited twenty-two fifth-grade boys to a summer camp at Robbers Cave State Park, in southeastern Oklahoma. The boys were all white, from middle-class, Protestant, two-parent households. Sherif and his team divided them into two groups, each unaware that the other was housed in a cabin at another end of the camp. In the first phase of the study, lasting about a week, the groups, which named themselves the Eagles and the Rattlers, bonded over shared interests and activities—hiking, swimming, a treasure hunt with a ten-dollar reward. In the second phase, the groups were brought together in a series of zero-sum competitions: baseball, tug-of-war, touch football. The researchers, who doubled as camp counsellors, orchestrated hijinks. One group was delayed in arriving at a picnic; when they got there, they were led to believe that the other group had eaten their food. Tensions rose. The Eagles burned the Rattlers’ flag; the Rattlers raided the Eagles’ cabin. Researchers had to step in to break up fights. Division had set in.

The goal of the third phase was to defuse the animosity. As a first step, the researchers organized a series of noncompetitive activities. The boys shared meals, watched a movie together, and celebrated the Fourth of July. Little changed. Only when the campers were given tasks requiring collaboration on a common endeavor—restarting a stalled food truck, pitching a tent with missing supplies, raising money for a movie night—did conflict decline. In the end, one group bought the other malted milk.

The findings of the Robbers Cave experiment have become a staple of undergraduate seminars and psychology textbooks. But they appear not to apply to our current moment. Never before has it been so clear that our work, behavior, and fates are inextricably linked to those around us. Working together to control the virus should have been the ultimate shared goal. And yet, facing viral invasion, Americans couldn’t agree not to sneeze on one another. While fighting the pandemic, America has remained one of the world’s most polarized nations.

It turns out that the Robbers Cave experiment doesn’t tell the whole story. As Gina Perry explains in her book “ The Lost Boys ,” Sherif had conducted a near-identical experiment the year before, in 1953. He’d invited a similar cohort of boys to a camp in upstate New York and divided them into groups: the Panthers and the Pythons. The researchers had carried out a similar series of conflict-generating shenanigans: they’d stolen clothes, ransacked tents, and broken a boy’s ukulele. This time, however, the boys caught on—they realized that they were being manipulated. Instead of fighting one another, they turned on the adults. “Maybe you just wanted to see what our reactions would be,” one boy suggested to a researcher. One of the groups decided that their clothes must have gone missing because of a laundry mishap; both sides worked together to restore an overturned tent. As the experiment unravelled, Sherif began drinking heavily. He grew so despondent that he nearly punched a research assistant in the face. The experiment was stopped early; Sherif never published the findings.

In an era of social-media virality, cable-news punditry, and political celebrity, we, too, are being manipulated. The ire we direct at one another is, at least in part, a result of forces that aim to extract political or financial gain by stoking division and appealing to our basest instincts. Despite knowing better, people in power traffic in half-truths, adding to the cacophony of conflict. They reflect our discord but also create it. We don’t yet know what post-liminal life looks like—but recognizing that truth may be the first step to healing the divide.

More on the Coronavirus

How China’s response set the stage for a worldwide wave of censorship .

Why are preschoolers subject to the strictest COVID rules in New York City ?

Ecuador’s largest city endured one of the world’s most lethal outbreaks .

What it was like to treat some of the oldest and sickest people in New York’s jails .

Young New Yorkers grapple with the pandemic’s mental toll .

In the COVID era, the success of the chickenpox vaccine is staggering to contemplate.

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Amy Davidson Sorkin

By Sam Knight

By Gideon Lewis-Kraus

By Andrew Marantz

COVID-19: Where we’ve been, where we are, and where we’re going

One of the hardest things to deal with in this type of crisis is being able to go the distance. Moderna CEO Stéphane Bancel

Where we're going

Living with covid-19, people & organizations, sustainable, inclusive growth, related collection.

The Next Normal: Emerging stronger from the coronavirus pandemic

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- TikTok’s fate

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66606035/1207638131.jpg.0.jpg)

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.