With Religious Tensions Worsening in India, Understanding Caste Is More Urgent Than Ever

A new Bollywood movie is galvanizing Hindu audiences and stirring up a fresh wave of anti-Muslim bigotry. In the name of India’s Hindu majority, hijabs are banned in one Indian state and Muslims attacked for praying publicly in New Delhi. A hardline Hindu supremacist, infamous for his anti-Muslim comments and for policies that demonize or exclude Muslims, wins a second term as chief minister of India’s most populous state, Uttar Pradesh. His victory is seen as a ringing endorsement of the ideology of Hindutva .

The belief that India is not a secular nation, or even multi-religious, but an intrinsically Hindu country, is the central platform of India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). But the “Hindu majority” invoked by supporters of Hindutva , in their agitation against Muslims and other minorities, is not a monolithic bloc. In fact, it is highly stratified, with elite groups of Hindus exploiting the vulnerability of marginalized communities for their own political ends.

If Hindu unity is a facade, it also follows that the Hindu-Muslim binary, while a common framing for the discussion of Indian politics, cannot be as straightforward as it appears.

Read More: Pakistan, India, and the Trap of Extremism

To understand the nuances of Indian politics , one needs to understand the complex caste system . At three thousand years old, this system of organizing Hindus by their professions and obligations is the world’s longest running hierarchy and probably the most rigid. By some estimates , there are 3,000 main castes and as many as 25,000 sub-castes, with Brahmins (intellectuals) at the top and Shudras (menials) at the bottom.

Lying outside this system are the Dalits (formerly called “untouchables”) and the Adivasi (indigenous tribes), together totaling 350 million people, or just over a quarter of India’s population. They are the most socio-economically marginalized groups in the country, but they are also contested over by Hindu nationalists, who see them as useful foot soldiers in the struggle against Islam.

“Hindu nationalism is led by the upper castes and their incitement of all Hindus against the Muslim minority is a ploy that enables them to keep their grip on Hindu society,” says the welfare economist Jean Drèze . “It makes it all the more difficult for Dalits and other exploited groups to question their own oppression by the upper castes and revolt against it.”

The political manipulation of India’s caste system

At the same time, there is a fear that other religions will prove more attractive to the disadvantaged communities who, being outside the caste system, need not have any particular loyalty to Hinduism. Dalits are not even allowed to enter many Hindu temples. Small wonder that Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (1891-1956), a revered Dalit leader and the head of the committee that drafted Indian constitution, urged every Dalit to convert to Buddhism.

If the 25% of the population represented by such communities were to become Buddhists or Christians, the idea of Hindutva would be seriously weakened. Mass Dalit conversions have already taken place. In response, legal moves have been made in several Indian states to prevent people from leaving the Hindu religion.

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a Hindu Nationalist group and the parent organization of the BJP, is also making strenuous if belated efforts to include Dalits and the Adivasis in the Hindu fold . Mohan Bhagwat, the head of the RSS, told a gathering in January that the caste system was “an obstacle to Hindu unity.” Last year, he also said “we consider every Indian a Hindu.”

Using such language, the RSS is able to appeal to emotionally vulnerable Dalits, helping them feel accepted in a society that has historically excluded them. Dalits are told that they are “the real warriors of Hinduism.”

Read More: The Movement to Outlaw Caste Discrimination in the U.S.

The next step is conversion “into active anti-Muslim sentiments,” says Bhanwar Meghwanshi. Today a Dalit-rights activist, Meghwanshi formerly served in the organization and wrote a book about his experiences entitled I Could Not Be Hindu: The Story of a Dalit in the RSS .

“We were trained to hate Muslims,” he says, “so we could be [RSS] foot soldiers in anti-Muslim riots.” (Tellingly, the great majority of those arrested in the 2002 Gujurat riots were from Dalit and other disadvantaged groups.)

Ironically, its middle initial stands for swayamsevak or “self-reliance,” when the RSS is heavily reliant on Dalits and Adivasis to do its dirty work during periods of communal violence.

Compounding the issue is the fact that the Muslim community is also stratified on caste lines , in ways that mirror the Hindu system. Indian Islam has its ashrafs (nobles), ajlafs (commoners), and arzals (“despicables”).

The political manipulation of disadvantaged castes will continue so long as they refuse to see that they are “simply pawns in the middle,” being led by “oppressor castes,” says Suraj Kumar Bauddh, an anti-caste activist and the founder of Mission Ambedkar . “Whether they are Hindu lower-caste communities, or Muslim lower-caste communities, they are only told to kill and die, to gain acceptance within either fold.”

The existence of a ready supply of expendable fighters can only exacerbate India’s spiraling religious tensions . Now more than ever, Dalits, Adivasis—and disadvantaged Muslims—must reframe the political debate.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Why We're Spending So Much Money Now

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- Breaker Sunny Choi Is Heading to Paris

- Why TV Can’t Stop Making Silly Shows About Lady Journalists

- The Case for Wearing Shoes in the House

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

Religion, Caste and Politics in India

69 citations

60 citations

57 citations

51 citations

47 citations

Related Papers (5)

Trending questions (1).

The traditional Nehruvian system is giving way to a less cohesive but a more active India, a country that has already become what it is against all the odds.

Ask Copilot

Related papers

Related topics

- Post-doc Fellows

- Lang. Instructors

- Admin. Staff

- Linguistics

- Areas of Specialisation (PhD)

- M.A. Culture Society Thought

- M.Sc. in Cognitive Science

- M.Sc. in Economics

- Indian and Foreign Languages Learning Programme

Search form

Call for Papers: Caste and Religion in India

Life-cycle events in India are often determined by identities or “master statuses” acquired at birth, such as caste, which play a significant role in an individual’s everyday social life. While extensive studies have been conducted on the role of caste in Hinduism, the interplay between caste and non-Hindu religions in India has received less attention. Therefore, the objective of this volume is to explore the complex, contingent, and multifaceted nature of caste beyond Hinduism, particularly, in non-Hindu religions. Previous scholarship has examined caste practices among non-Hindu religions, including Islam (Ahmad 1978; Sikand 2014), Christianity (Roberts 2016; Mohan 2015; Mosse 2012; Sahoo 2019), Sikhism (Jodhka 2002), Buddhism (Omvedt 2003), and Jainism (Cort 2004), revealing that while the form of caste may differ from that of Hinduism, its presence is increasingly evident. Scholars have noted that untouchability and caste discrimination have spread to non-Hindu religions, despite the absence of official support for caste-based practices in these religions (Waughray 2010; Jodhka 2002). Further, the Deshpande Report found that in many social contexts, Muslim and Christian Dalits are “Dalits first and Muslims and Christians only second,” suffering from socio-economic and educational disadvantages as well as discrimination on the basis of caste (Deshpande and Bapna 2010). However, it should be noted that the legal recognition of Scheduled Caste status is only applicable to Hindus and to adherents of Sikhism and Buddhism- religions which have been “legally re-absorbed as Hinduism”(Waughray 2010). Caste in Abrahamic religions and non-Hindu Indic religions is a ‘hard to describe’ force; visible but hidden, pervasive but incomprehensible, argued against the core beliefs of the religion but essentially practiced, and profane but exists as sacredness embodied. As improbable as it may sound, an enlightening way to understand how deep-rooted caste and caste discrimination is in Indian societies is to explore how they are practised, integrated, and (mis)interpreted by monolithic Abrahamic religions that present themselves as ‘egalitarian religions’ and Indic religions that emerged as a reform movement against the caste system in Hinduism. Scholars have put forward the argument that affirmative action programs should aim to promote empowerment and eliminate exclusion in minority groups (Waughray 2010; Hassan 2012). However, the present state of academic scholarship and social policies falls short in addressing the issue of exclusion experienced by Dalits in non-Hindu communities (Hassan 2012). To critically analyze the complex intersections between caste and non-Hindu religion in India, this edited volume endeavours to explore the multifaceted ways in which caste operates as a pervasive and pan-religious phenomenon in the Indian subcontinent. In pursuit of this objective, a formal call for contributions has been extended for an edited collection that is currently being developed for a reputed publishing house. The proposed edited volume seeks to centralize non-Hindu religions in the caste debate in India and solicit chapters that offer insights into how various religions in India practice and embody the caste system. The volume invites scholars to examine the intricate relationship between non-Hindu religions and caste in India.

We invite papers on a range of themes and questions, including: • What is the impact of caste on the social, economic, and educational status of Dalits in non-Hindu communities? • How do caste and religion intersect with other forms of identity, such as gender and class, within non-Hindu communities in India? • How has caste affected the life-cycle events, such as birth, marriage, and death, in non-Hindu religions in India? • In what ways has culture or tradition been used as a proxy and justification for caste oppression, and how can demands from the oppressed be considered as paths to reconciliation and healing? • How do micro-events perpetuate caste discrimination and humiliation, and how do the dominant group use them to maintain their status quo, ethnic superiority, privilege and status, cultural hegemony, and control of Bourdieusian economic, social, cultural, and political capitals? • How have non-Dalit members of non-Hindu communities perpetuated or challenged caste-based discrimination within their own communities? • Why does caste survive in non-Hindu religions and how do different political interests either support, reject, or banish the institution?

Please send us an extended abstract of around 500-800 words highlighting your research questions, arguments and data sources and a brief CV (max 2 page) by 30th June 2023, in Word format (.docx) to [email protected] . We will send our decisions on abstracts by 15th July 2023. Accepted papers will be due on 30th September 2022. The length of the final manuscript is expected to be between 5,000 and 7,000 words (including all end notes and bibliographies).

References Ahmad, Imtiaz. 1978. Caste and Social Stratification among the Muslims in India. Manohar: New Delhi. Cort, John E. 2004. “Jains, Caste and Hierarchy in North Gujarat.” Contributions to Indian Sociology 38 (1–2): 73–112. Deshpande, Satish, and Geetika Bapna. 2010. “Dalits in the Muslim and Christian Communities.” New Delhi. Jodhka, Surinder S. 2002. “Caste and Untouchability in Rural Punjab.” Economic and Political Weekly, no. May: 1813–23. Mohan, S. (2015) Modernity of Slavery: Struggles Against Caste Inequality in Colonial Kerala, New Delhi: Oxford University Press. Mosse, David. 2012. The Saint in the Banyan Tree: Christianity and Caste Society in India, Berkeley: University of Californial Press. Omvedt, G. 2003. Buddhism in India: Challenging Brahmanism and Caste. Sage Publications India. Roberts, N. (2016) To be Cared For: The Power of Conversion and Foreignness of Belonging in an Indian Slum, Berkeley: University of California Press. Sahoo, Sarbeswar. 2019. “Caste, Conversion, and Care:Toward an Anthropology of Christianity in India.” Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies 32: 3. Sikand, Yoginder. (2004). Islam, caste, and Dalit-Muslim relations in India. Global Media Publications. Waughray, Annapurna. 2010. “Caste Discrimination and Minority Rights: The Case of India’s Dalits.” International Journal on Minority and Group Rights 17 (2): 327–53.

Contact Details: Prof. Sarbeswar Sahoo Professor of Sociology Dept. of Humanities & Social Sciences Indian Institute of Technology Delhi Email: [email protected]

Dr. Muhammed Haneefa Postdoctoral Fellow Dept. of Humanities & Social Sciences Indian Institute of Technology Delhi Email: [email protected]

- Follow us on social media

Copyright © Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi. All rights Reserved.

- Disciplines

- Publications

- Readers’ Blog

Why Indian politics is based on caste and religion?

I read somewhere, for a successful business, one must cater to customers what they want instead of what they need. It is a very powerful line and applies to every field. While in some fields, people are made aware of their needs letting them decide what they want further, in some others, the lack of knowledge regarding their actual needs is taken advantage of. And what comes to my mind thinking of the second type here is politics. I have often heard and read people complaining of politicians but the thing is, they are voted and they win by majority. They have a customer base and like every successful businessman, they cater what the majority of people want. The wants of people thus become the promises in election campaigns. Do politicians want to divide people based on caste and religion? Unfortunately, people have divided themselves in that manner and people want the divide to continue. Politicians only take advantage of the situation, they say what people want to hear and do what people want to do because at the end of all, it’s only the votes of people that would matter.

A major gap exists in between the adult literacy rates of both men and women of rural and urban India. And the definition of literacy is to be able to read, write and understand at least one language which is different from proper education and knowledge of the developments around the globe. Casteism and religion differences are more prominent in rural India and hence form a major part of “wants’ ‘ of majority there. Urban India is not free from these either but the priorities of many here include bigger things requiring developmental models to fulfil their wants these days. The catch here is the voting ratio between rural and urban India, which shows a reverse gap. Now there can be many reasons for this divide but those don’t change the result. It’s also not about rural and urban completely but about the two sets of people with different wants and clearly, the number of those wanting the divide is higher. WhatsApp groups flooding with forwarded messages invoking hatred against different communities is witness to it. Caste based census would play an important role in highlighting the majority community at different places so that their common wants can be understood better and used as an advantage in upcoming elections. Also, it would help in selection of candidates from that particular community increasing chances of winning multifold.

The only way to disassociate caste and religion from politics is correct education, the one that makes one realize the importance of developmental models in current times. Also, voting in large numbers would help in winning the desired leader. So, the next time you get a chance to contribute, vote and encourage others to vote along with providing good quality education to people around you, especially children because they are the future of our nation. The day we all will have better wants is the day we will be provided with better services.

dear sir you have rightly compared business with poltics. neirher there is no social service involoved in it nor these people are peoples representati...

and these days both business and politics are becoming too and too interlinked.

unless we get rid of caste/religion based quotas in everything, this fooling around by politicians will continue. india needs ews quota and the rest ...

All Comments ( ) +

Doctor who loves to express all that comes to my mind through writings. I seek more and more perspectives from people around so that I can understand everything better.

- The tree of life

- The course of grief and answer to when it will end

- It’s okay to not say

- What if Hindu- Muslim rivalry ends today?

- The core, mantle and crust of our personalities

Story of an Eagle

The role of technology in the future and its impact on society.

Toshan Watts

Today’s time is paramount!

Recently joined bloggers.

Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

1. religious freedom, discrimination and communal relations.

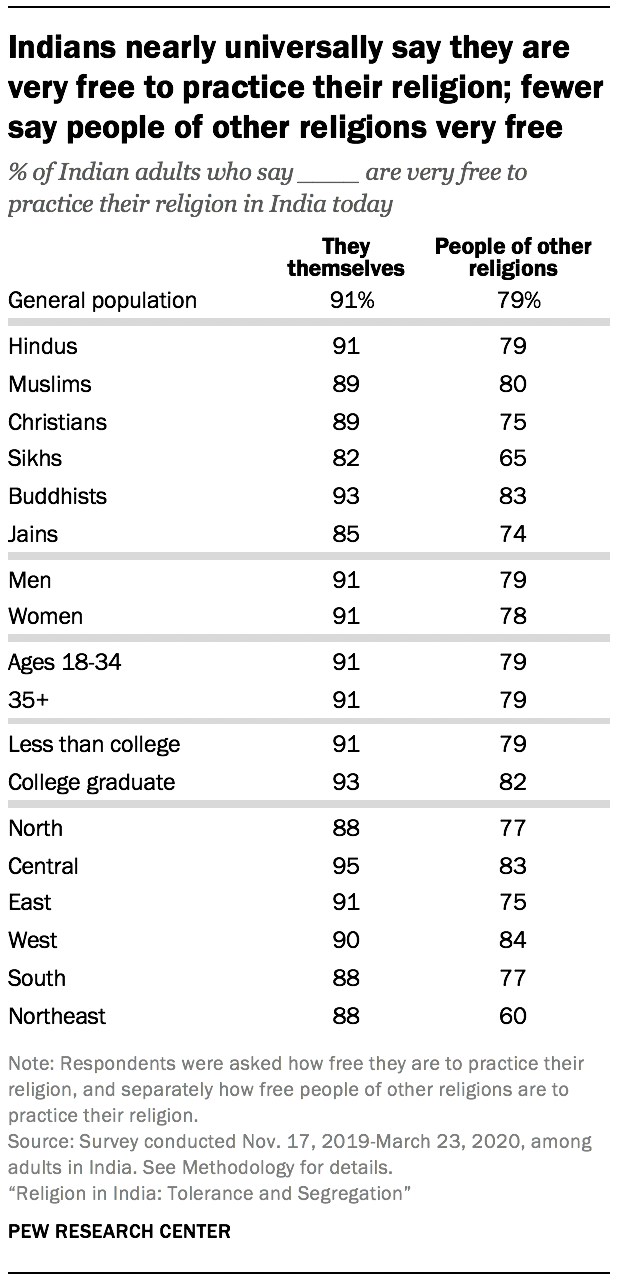

Indians generally see high levels of religious freedom in their country. Overwhelming majorities of people in each major religious group, as well as in the overall public, say they are “very free” to practice their religion. Smaller shares, though still majorities within each religious community, say people of other religions also are very free to practice their religion. Relatively few Indians – including members of religious minority communities – perceive religious discrimination as widespread.

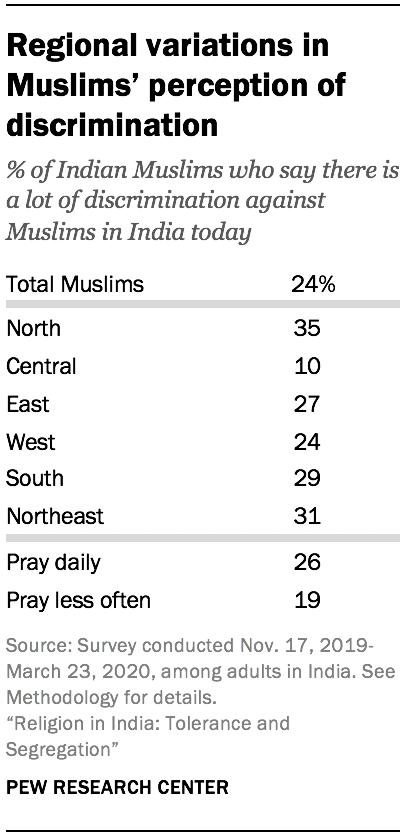

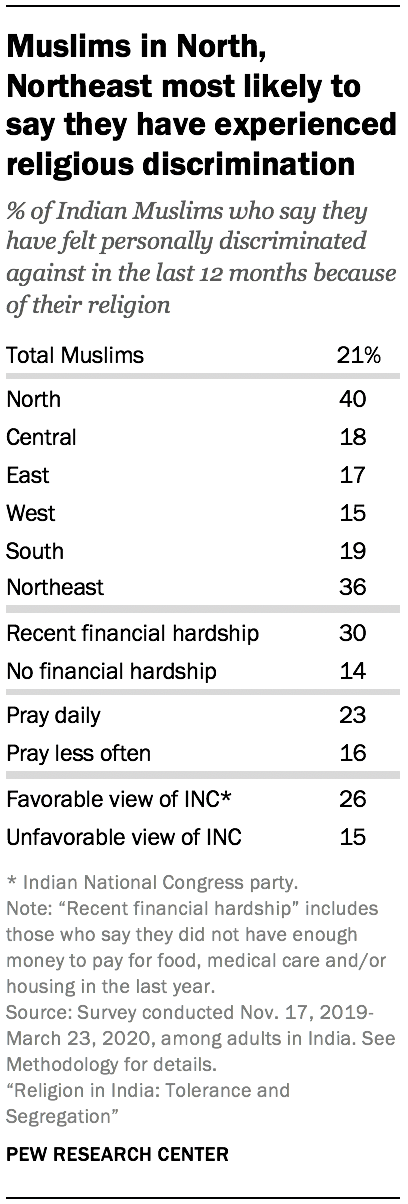

At the same time, perceptions of discrimination vary a great deal by region. For example, Muslims in the Central region of the country are generally less likely than Muslims elsewhere to say there is a lot of religious discrimination in India. And Muslims in the North and Northeast are much more likely than Muslims in other regions to report that they, personally, have experienced recent discrimination.

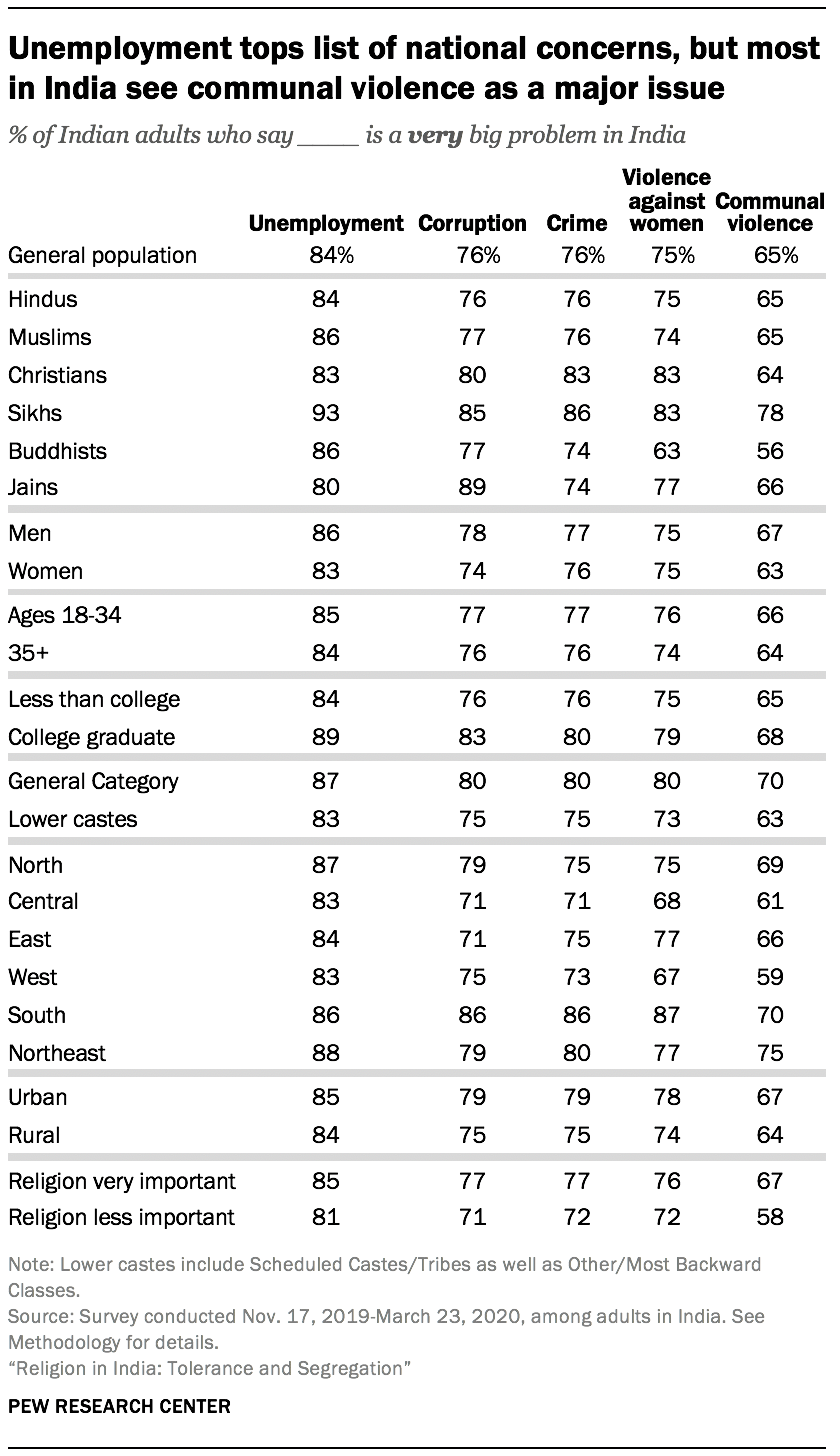

Indians also widely consider communal violence to be an issue of national concern (along with other problems, such as unemployment and corruption). Most people across different religious backgrounds, education levels and age groups say communal violence is a very big problem in India.

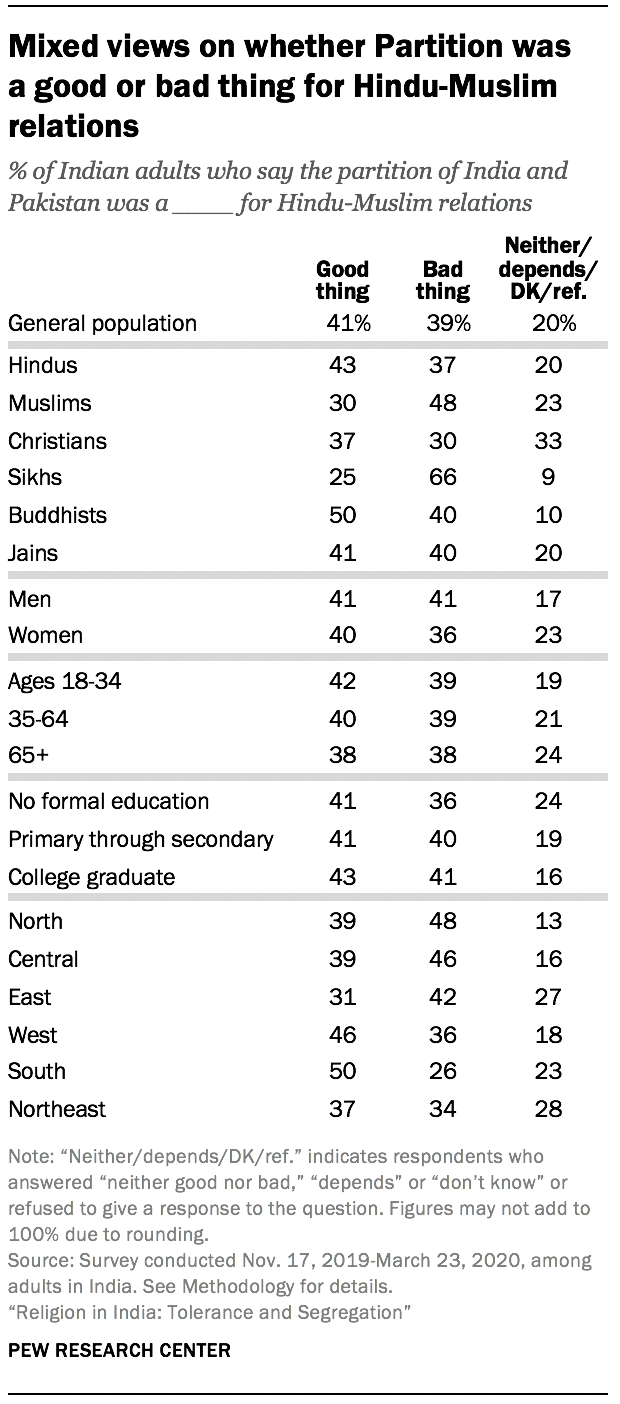

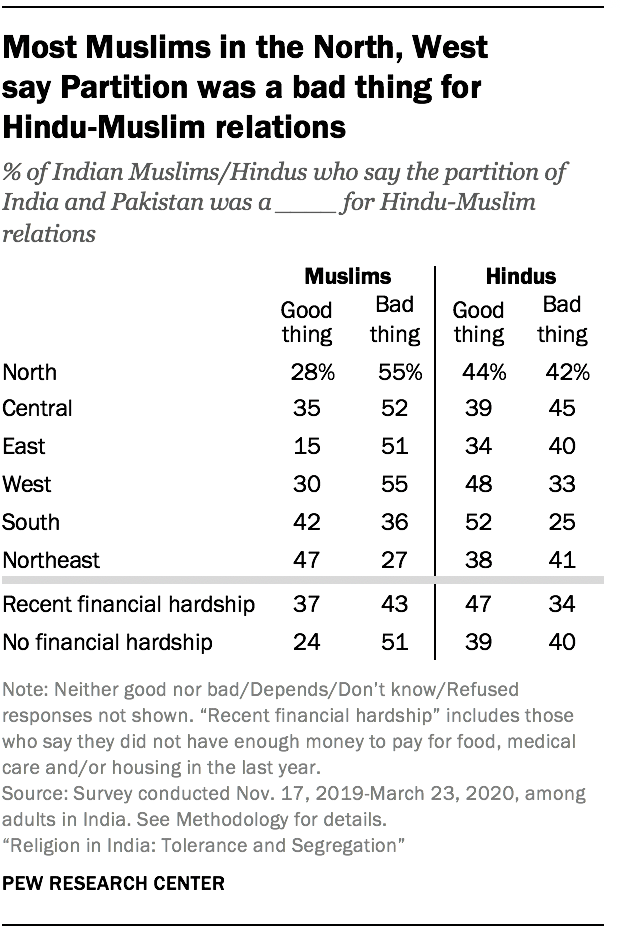

The partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 remains a subject of disagreement. Overall, the survey finds mixed views on whether the establishment of Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan alleviated communal tensions or stoked them. On balance, Muslims tend to see Partition as a “bad thing” for Hindu-Muslim relations, while Hindus lean slightly toward viewing it as a “good thing.”

Most Indians say they and others are very free to practice their religion

Broadly speaking, Indians are more likely to view themselves as having a high degree of religious freedom than to say that people of other religions are very free to practice their faiths. Still, 79% of the overall public – and about two-thirds or more of the members of each of the country’s major religious communities – say that people belonging to other religions are very free to practice their faiths in India today.

Generally, these attitudes do not vary substantially among Indians of different ages, educational backgrounds or geographic regions. Indians in the Northeast are somewhat less likely than those elsewhere to see widespread religious freedom for people of other faiths – yet even in the Northeast, a solid majority (60%) say there is a high level of religious freedom for other religious communities in India.

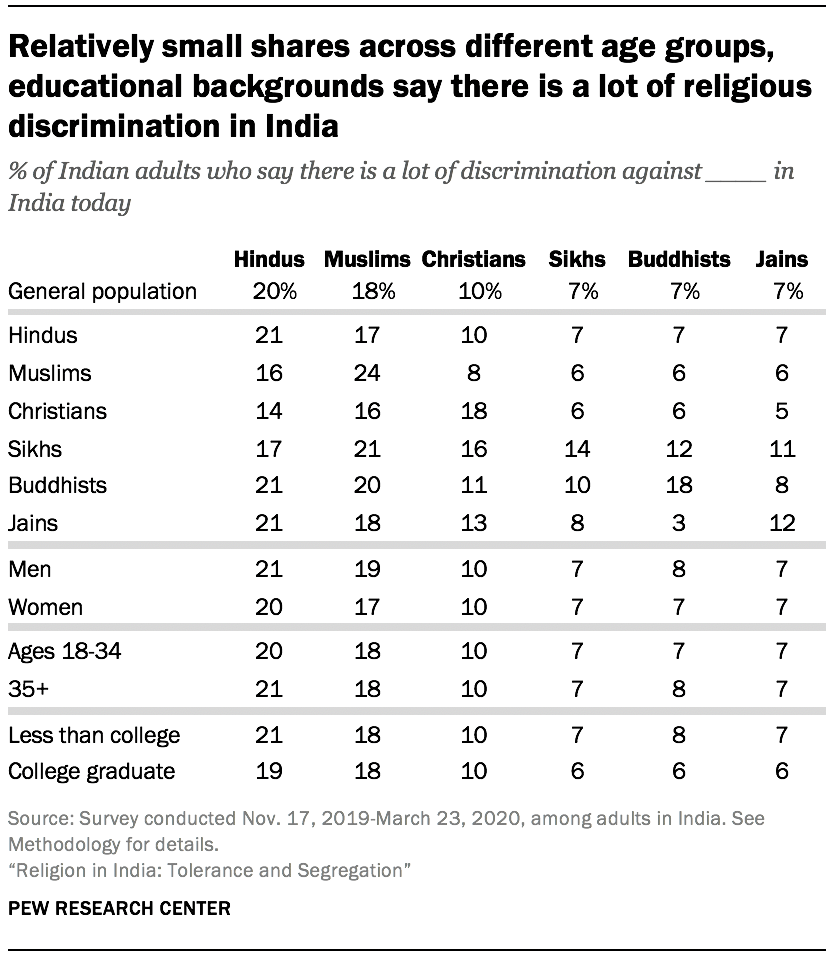

Most people do not see evidence of widespread religious discrimination in India

Generally, Indians’ opinions about religious discrimination do not vary substantially by gender, age or educational background. For example, among college graduates, 19% say there is a lot of discrimination against Hindus, compared with 21% among adults with less education.

Within religious groups as well, people of different ages, as well as both men and women, tend to have similar opinions on religious discrimination.

Among Muslims, perceptions of discrimination against their community can vary somewhat based on their level of religious observance. For instance, about a quarter of Muslims across the country who pray daily say there is a lot of discrimination against Muslims (26%), compared with 19% of Muslims nationwide who pray less often. This difference by observance is pronounced in the North, where 39% of Muslims who pray every day say there is a lot of discrimination against Muslims in India, roughly twice the share among those in the same region who pray less often (20%).

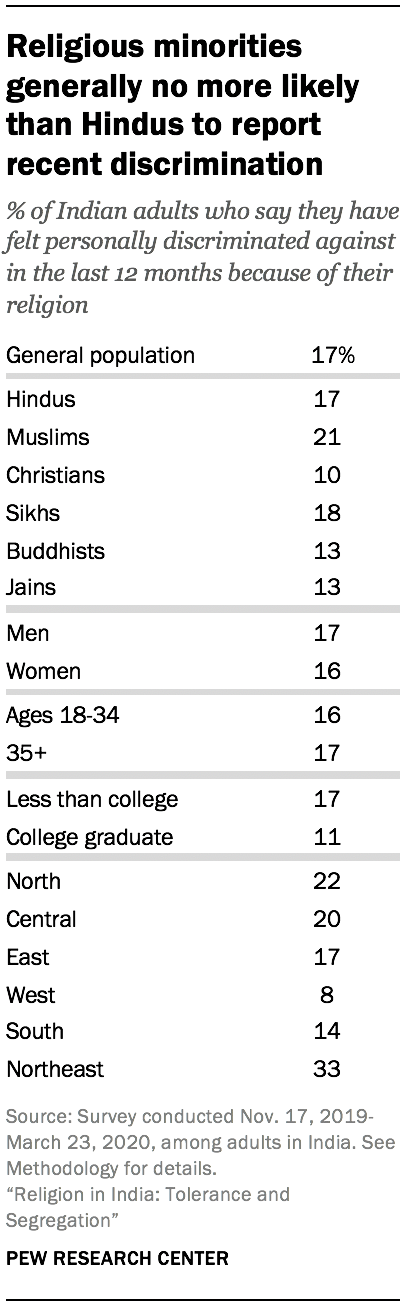

Most Indians report no recent discrimination based on their religion

Nationally, men and women and people belonging to different age groups do not differ significantly from each other in their experiences with religious discrimination. People who have a college degree, however, are somewhat less likely than those with less formal schooling to say they have experienced religious discrimination in the past year.

Experiences with religious discrimination also are more common among Muslims who are more religious and those who report recent financial hardship (that is, they have not been able to afford food, housing or medical care for themselves or their families in the last year).

Muslims who have a favorable view of the Indian National Congress party (INC) are more likely than Muslims with an unfavorable view of the party to say they have experienced religious discrimination (26% vs. 15%). Among Northern Muslims, those who have a favorable view of the INC are much more likely than those who don’t approve of the INC to say they have experienced discrimination (45% vs. 23%). (Muslims in the country, and especially Muslims in the North, tend to say they voted for the Congress party in the 2019 election. See Chapter 6 .)

Hindus with less education and those who have recently experienced poverty also are more likely to say they have experienced religious discrimination.

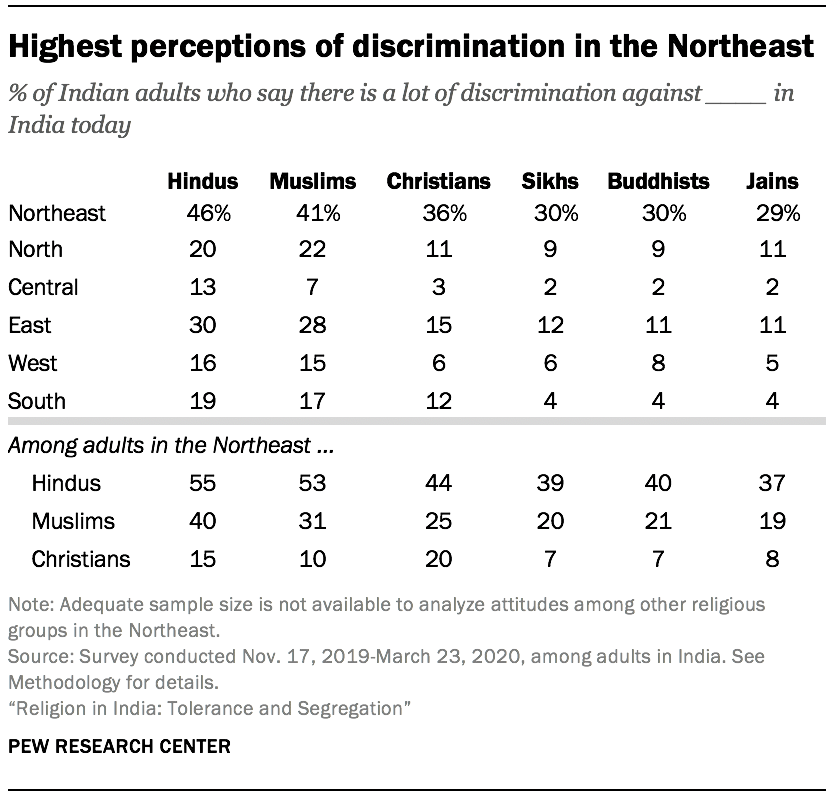

In Northeast India, people perceive more religious discrimination

Less than 5% of India’s population lives in the eight isolated states of the country’s Northeastern region. This region broadly lags behind the country in economic development indicators. And this small segment of the population has a linguistic and religious makeup that differs drastically from the rest of the country.

According to the 2011 census of India, Hindus are still the majority religious group (58%), but they are less prevalent in the Northeast than elsewhere (81% nationally). The smaller proportion of Hindus there is offset by the highest shares of Christians (16% vs. 2% nationally) and Muslims (22% vs. 13% nationally) in any region. And based on the survey, the region also has a higher share of Scheduled Tribes than any other region in the country (25% vs. 9% nationally), and half of Scheduled Tribe members in the Northeast are Christians.

Much of the Northeast’s perception of high religious discrimination is driven by Hindus in the region. A slim majority of Northeastern Hindus (55%) say there is widespread discrimination against Hindus in India, while almost as many (53%) say Muslims face a lot of discrimination. Substantial shares of Hindus in the Northeast say other religious communities also face such mistreatment.

The region’s other religious communities are less likely to say there is religious discrimination in India. For example, while 44% of Northeastern Hindus say Christians face a lot of discrimination, only one-in-five Christians in the Northeast perceive this level of discrimination against their own group. By contrast, at the national level, Christians are more likely than Hindus to see a lot of discrimination against Christians (18% vs. 10%).

People in the Northeast also are more likely to report experiencing religious discrimination. While 17% of individuals nationally say they personally have felt religious discrimination in the last 12 months, one-third of those surveyed in the Northeast say they have had such an experience. Northeastern Hindus, in particular, are much more likely than Hindus elsewhere to report recent religious discrimination (37% vs. 17% nationally).

Most Indians see communal violence as a very big problem in the country

But even larger majorities identify several other national problems. Unemployment tops the list of national concerns, with 84% of Indians saying this is a very big problem. And roughly three-quarters of Indian adults see corruption (76%), crime (76%) and violence against women (75%) as very big national issues. (The survey was designed and mostly conducted before the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic.)

Indians across nearly every religious group, caste category and region consistently rank unemployment as the top national concern. Buddhists, who overwhelmingly belong to disadvantaged castes, widely rank unemployment as a major concern (86%), while just a slim majority see communal violence as a very big problem (56%).

Sikhs are more likely than other major religious groups in India to say communal violence is a major issue (78%). This concern is especially pronounced among college-educated Sikhs (87%).

Among Hindus, those who are more religious are more likely to see communal violence as a major issue: Fully 67% of Hindus who say religion is very important in their lives consider communal violence a major issue, compared with 58% among those who say religion is less important to them.

Indians in different regions of the country also differ in their concern about communal violence: Three-quarters of Indians in the Northeast say communal violence is a very big problem, compared with 59% in the West. Concerns about communal violence are widespread in the national capital of Delhi, where 78% of people say this is a major issue. During fieldwork for this study, major protests broke out in New Delhi (and elsewhere) following the BJP-led government’s passing of a new bill, which creates an expedited path to citizenship for immigrants from some neighboring countries – but not Muslims.

Indians divided on the legacy of Partition for Hindu-Muslim relations

About four-in-ten (41%) say the partition of India and Pakistan was a good thing for Hindu-Muslim relations, while a similar share (39%) say it was a bad thing. The rest of the population (20%) does not provide a clear answer, saying Partition was neither a good thing nor a bad thing, that it depends, or that they don’t know or cannot answer the question. There are no clear patterns by age, gender, education or party preference on opinions on this question.

Among Muslims, the predominant view is that Partition was a bad thing (48%) for Hindu-Muslim relations. Fewer see it as a good thing (30%). Hindus are more likely than Muslims to say Partition was a good thing for Hindu-Muslim relations (43%) and less likely to say it was a bad thing (37%).

Of the country’s six major religious groups, Sikhs have the most negative view of the role Partition played in Hindu-Muslim relations: Nearly two-thirds (66%) say it was a bad thing.

Most Indian Sikhs live in Punjab, along the border with Pakistan. The broader Northern region (especially Punjab) was strongly impacted by the partition of the subcontinent, and Northern Indians as a whole lean toward the position that Partition was a bad thing for Hindu-Muslim relations (48%) rather than a good thing (39%).

Attitudes toward Partition also vary considerably by region within specific religious groups. Among Muslims in the North and West, most say Partition was a bad thing for Hindu-Muslim relations (55% of Muslims in both regions). In the Eastern and Central parts of the country as well, Muslim public opinion leans toward the view that Partition was a bad thing for communal relations. By contrast, Muslims in the South and Northeast tend to see Partition as good for Hindu-Muslim relations.

Among Hindus, meanwhile, those in the North are closely divided on the issue, with 44% saying Partition was a good thing and 42% saying it was a bad thing. But in the West and South, Hindus tend to see Partition as a good thing for communal relations.

Poorer Hindus – that is, those who say they have been unable to afford basic necessities like food, housing and medical care in the last year – tend to say Partition was a good thing. But opinions are more divided among Hindus who have not recently experienced poverty (39% say it was a good thing, while 40% say it was a bad thing). Muslims who have not experienced recent financial hardship, however, are especially likely to see Partition as a bad thing: Roughly half (51%) say Partition was a bad thing for Hindu-Muslim relations, while only about a quarter (24%) see it as a good thing.

Sign up for our Religion newsletter

Sent weekly on Wednesday

Report Materials

Table of contents, india’s sex ratio at birth begins to normalize, how indians view gender roles in families and society, key facts about the religiously and demographically diverse states of india, religious composition of india, key findings about the religious composition of india, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

What to Know About Holi, India’s Most Colorful Tradition

The ancient festival has Hindu roots, but growing numbers worldwide are taking part in the celebration, which features bonfires, singing, dancing, prayer, feasting and clouds of pigmented powder.

By John Yoon and Hari Kumar

A rainbow haze swirls through India, where raucous laughter rings out as friends and strangers douse one another with fists full of pigmented powder. It is time for the ancient Hindu tradition of Holi, an annual celebration of spring.

In 2024, crimson, emerald, indigo and saffron clouds will hover over the country on March 25 for one of its most vibrant, joyful and colorful festivals.

“Playing Holi,” as Indians say, has spread far beyond India’s borders.

The revelry starts at sundown.

Holi (pronounced “holy”), also known as the “festival of colors,” starts on the evening of the full moon during the Hindu calendar month of Phalguna, which falls around February or March.

It begins with the kindling of bonfires. People gather around the flames to sing, dance and pray for an evening ritual called Holika Dahan, which re-enacts the demise of a Hindu demoness, Holika.

All sorts of things are thrown into the fires, like wood, leaves and food, in a symbolic purge of evil and triumph of good.

From Delhi, Archie Singhal, 24, visits her family in Gujarat the day before Holi, when the fire is lit in the evening. The next morning, she prepares for the bursts of powder, called gulal, by applying oil on her body so the colors don’t stick to her skin. She puts on old clothes she doesn’t mind tossing.

Why the colors?

Holi’s roots are in Hinduism. The god Krishna, cursed by a demon with blue skin, complained to his mother, asking why his love interest Radha is fair while he is not. His mother, Yashoda, playfully suggests that he paint Radha’s face with any colors he wishes. So Krishna smears color on her so they look alike.

Holi is in part a celebration of the love between Krishna and Radha that looks past differences. Today, some of the gulal used during Holi is synthetic. But the colors traditionally come from natural ingredients, such as dried flowers, turmeric, dried leaves, grapes, berries, beetroot and tea.

“There is an environment of freedom,” Ms. Singhal said, adding that she doesn’t hesitate to throw colors on her younger brother, parents, aunts, uncles and neighbors.

Everyone takes part.

The ancient Hindu festival eschews the religious, societal, caste and political divisions that underpin India’s often sectarian society . Hindu or not, anybody can be splashed with brightly colored dust, or even eggs and beer.

Some partake in worship, called puja, offering prayers to the gods. For others, Holi is a celebration of community. The festival gets everyone involved — including innocent passers-by.

“People forget their misunderstandings or enmity during this occasion and again become friends,” said Ratikanta Singh, 63, who writes, sometimes about Holi, in Assam, in northeastern India.

There’s a feast.

When not throwing around gulal, friends, families and neighbors partake in a buffet of traditional dishes and drinks. They include gujiya, dumpling-like fried sweets filled with dried fruits and nuts; dahi vada, deep-fried lentil fritters served with yogurt; and kanji, a traditional drink made by fermenting carrots in water and spices.

Some celebrate Holi with thandai, a light green concoction of milk, rose petals, cardamom, almonds, fennel seeds and other ingredients. For thousands of years, the drink has sometimes been laced with bhang, or crushed marijuana leaves, which add to the mood of revelry.

Holi has ancient roots.

Holi has been documented for centuries in Hindu texts. The tradition is observed by people young and old, particularly in Northern India and Nepal, where the stories behind the festival originated.

Holi also marks the harvesting of crops with the arrival of spring in India, where more than half of the population lives in rural areas.

Traditions vary across India.

Holi celebrations are as diverse as the Indian subcontinent. They are particularly wild in North India, considered the birthplace of the Hindu god Krishna, where celebrations can last more than a week.

In Mathura, a northern city where Krishna is said to have been born, people recreate a Hindu story in which Krishna visits Radha to romance her, and her cowherd friends, taking offense at his advances, drive him out with sticks.

In the eastern state of Odisha, people hold a dayslong festival called Dola Purnima . Grand processions of people shouldering richly decorated carriages with idols of Hindu gods are a large part of the festivities there. The processions are full of drumbeats, songs, colorful powder and flower petals thrown into the air.

In southern India, where Holi is not celebrated as widely, many temples carry out religious rites. In the Kudumbi tribal community, in the southwest, temples cut areca palms and transport their trunks to the shrine in a ritual that symbolizes the victory good over evil.

It’s not just in India.

Holi is celebrated around the world, wherever the Indian diaspora has gone. More than 32 million Indians and people of Indian origin are overseas, most in the United States, where 4.4 million reside, according to the Indian government.

It is also widely enjoyed in countries as varied as Fiji, Mauritius, South Africa, Britain and other parts of Europe.

Holi is known as Phagwah in the Indian communities of the Caribbean, including in Guyana , Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago.

The festival has also been used by the Indian government to project soft power and reshape its image as part of its “ Incredible India ” tourism campaign.

On Holi, “the world is a global village,” said Shubham Sachdeva, 29, from an eastern Delhi suburb, who added that his friends in the United States were celebrating Holi with their roommates whether they were Indian or not. “All this brings the world close to each other.”

An earlier version of a picture caption with this article misstated the location of a Holika Dahan celebration. It was in Durban, South Africa, not India.

How we handle corrections

John Yoon is a Times reporter based in Seoul who covers breaking and trending news. More about John Yoon

Hari Kumar covers India, based out of New Delhi. He has been a journalist for more than two decades. More about Hari Kumar

The Next Swaraj: Bansuri’s Political Debut Amid Nepotism Accusations

In a move that has ignited discussions surrounding political nepotism and dynasty politics, Bansuri Swaraj, the daughter of late BJP stalwart Sushma Swaraj, is set to make her electoral debut in the upcoming Lok Sabha elections. The 40-year-old lawyer has been fielded by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) from the prestigious New Delhi constituency, replacing the incumbent Union Minister Meenakshi Lekhi. As she prepares to embark on her political journey, Bansuri finds herself at the intersection of her family’s legacy and the ever-present debate over the influence of political dynasties in Indian democracy

A contested inheritance

Born into a family steeped in politics, Bansuri’s pedigree is undeniable. Her mother, Sushma Swaraj, was a towering figure in Indian politics, serving as the Minister of External Affairs and the Chief Minister of Delhi, among other prominent roles. Sushma’s unwavering dedication to public service and her ability to connect with the masses earned her a widespread following, and her untimely demise in 2019 left a void in the political landscape.

It is this void that Bansuri now aims to fill, inheriting not only her mother’s legacy but also the weight of expectations that come with it. Her entry into the fray has reignited discussions around the role of political dynasties in Indian democracy, with critics arguing that such nepotistic practices undermine the principles of meritocracy and equal opportunity. They contend that political power should be earned through merit and hard work, not inherited through familial connections.

However, Bansuri’s supporters counter these criticisms by pointing to her impressive academic credentials and professional achievements. A graduate of the prestigious Oxford University and the University of Warwick, she was called to the Bar at the Honourable Society of Inner Temple in London. Since 2007, she has carved out a successful legal career, serving as the Additional Advocate General for the state of Haryana and representing high-profile clients in complex litigations spanning contracts, real estate, tax, and international commercial arbitrations.

Her advocates argue that her qualifications and experience in the legal field make her a formidable candidate, regardless of her family background. They contend that her pedigree should not be held against her, as long as she demonstrates her capabilities and earns the trust of the electorate through her actions and policies.

Potential policy priorities

If elected, Bansuri is expected to champion the BJP’s agenda, aligning herself with the party’s ideological principles and policy positions. Given her legal background, she is likely to advocate for judicial reforms and measures to strengthen the rule of law. Her expertise in commercial litigation could also inform her approach to economic policies, with a focus on creating a business-friendly environment and attracting investments.

Moreover, as a woman from a political family, Bansuri may emerge as a voice for women’s empowerment, advocating for greater representation of women in decision-making roles and promoting initiatives aimed at addressing gender-based disparities. Her mother’s legacy as a trailblazer in Indian politics could serve as a guiding force in this regard.

A polarising figure

Bansuri’s foray into politics began last year when she was appointed as the co-convener of the BJP’s legal cell in Delhi. Her vocal criticism of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) government in the national capital and her staunch defence of the BJP’s policies have earned her both praise and criticism from different quarters.

Supporters laud her as a firebrand orator and a worthy successor to her mother’s legacy, capable of carrying forward the BJP’s agenda with passion and conviction. They believe that her legal expertise and her ability to articulate complex issues effectively will resonate with the electorate, particularly in a constituency like New Delhi, which has a sizeable population of educated and discerning voters.

Critics, however, accuse her of benefiting from her family’s political clout and question her ability to connect with the masses, a trait that defined her mother’s political success. They argue that while she may excel in legal circles, the true test of a politician lies in their ability to understand and address the concerns of ordinary citizens.

The AAP Offensive

The AAP, Bansuri’s primary opponent in the New Delhi constituency, has launched a scathing attack on her candidature. Senior AAP leader and Delhi minister Atishi has accused Bansuri of defending “ anti-national forces ” in court, referring to her representation of controversial figures like Lalit Modi, who is facing allegations of financial irregularities. The AAP has also criticised her for defending the BJP-led Centre’s stance on contentious issues like the Manipur violence and the alleged tampering of votes in the Chandigarh mayoral elections.

Bansuri, however, remains unfazed by these allegations, dismissing them as baseless and asserting that the people will give a fitting reply to her detractors at the ballot box. Her confidence stems from her belief that her legal acumen and her ability to articulate complex issues effectively will resonate with the electorate.

As the campaign trail heats up, Bansuri’s candidature will undoubtedly face intense scrutiny, not only from her political opponents but also from those concerned about the influence of political dynasties on Indian democracy. Her ability to carve out her own identity, distinct from her mother’s legacy, and to connect with the diverse constituents of the New Delhi constituency will be put to the test.

Amidst the noise of accusations and counteraccusations, one aspect that cannot be ignored is the potential for sympathy votes. Sushma Swaraj’s enduring popularity and the emotional connection she shared with the people could translate into a groundswell of support for her daughter, as voters seek to honour the late leader’s memory. This phenomenon of sympathy voting has been observed in various elections across India, where the children or spouses of beloved leaders have ridden to victory on the back of their family member’s legacy.

However, relying solely on sympathy votes would be a disservice to the democratic process and to Bansuri’s capabilities as a political aspirant. It is incumbent upon her to articulate her vision, her policies, and her commitment to the welfare of her constituents, transcending the confines of her family’s legacy. She must demonstrate her ability to connect with the electorate on her own merits, addressing their concerns and aspirations in a manner that resonates with their lived experiences.

The dynasty debate

Critics argue that sympathy voting, while understandable on an emotional level, can lead to a perpetuation of political dynasties, stifling the emergence of new leaders and fresh perspectives. They contend that true democracy thrives when the electorate critically evaluates candidates based on their merits, rather than being swayed by familial ties or emotional attachments.

As the nation gears up for the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, Bansuri Swaraj’s political debut will be closely watched, not only for its implications on the balance of power but also for its broader ramifications on the issue of political dynasties in India. Her success or failure at the polls will shape the discourse around this contentious topic and serve as a litmus test for the electorate’s acceptance or rejection of such practices.

Regardless of the outcome, Bansuri’s entry into the political arena is a defining moment in her life, one that will shape her future and potentially pave the way for a new generation of Swarajs to leave their mark on Indian politics. As she navigates the challenges and the controversies, her ability to emerge as a leader in her own right, unburdened by the weight of expectations and accusations, will be the true measure of her mettle.

If she succeeds in winning the hearts and minds of the electorate, she may well blaze a trail for others from political families to follow, proving that nepotism need not be a dirty word if the candidate can demonstrate their capabilities. However, if she falters, it could further fuel the scepticism surrounding dynasty politics and compel political parties to re-evaluate their reliance on familial ties as a means of securing votes.

Ultimately, the ball lies in the court of the voters, who will have the final say in determining whether Bansuri Swaraj’s candidature represents a continuation of dynastic politics or a testament to the democratic ideals of meritocracy and equal opportunity. As the nation watches with bated breath, the stage is set for a pivotal moment in India’s political history, one that could redefine the contours of the debate around dynasty politics for years to come.

Fat, neuro-diverse, and queer are the foremost words Sahil uses to describe themselves. A full-time undergraduate student of Economics at the University of Delhi, Sahil is a Laadli Media awardee of 2023. They are also a recipient of the Reliance Undergraduate Scholar for 2023 and various prestigious fellowships including Global Citizen Year Academy ’22 and Civics Unplugged (Civics Innovator Fellowship ’22). Sahil regularly writes for Thred Media, and also for Youth Ki Awaaz as an alumnus of the Justice-Makers WTP ’22.

Sahil is part of UNICEF India’s YuWaah Young People’s Action Team (YPAT) 2023 and the YLAC Ambassador for Delhi.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Related posts.

Sunita Kejriwal Stepping Into Political Spotlight: Understanding The Gendered Shift

By Nidhi Singh

Gender And Gandhi’s Political Philosophy: Where Are Our Founding Mothers?

By Adrita Bhattacharya

Why Is Sonam Wangchuk On A 21 Day Fast In Ladakh?

By Rahul Yadav

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Kashi Ram on 13 April 1984, a Dalit from Punjab is similar to the. SJP. Angered by the class discriminations, Kashi Ram came to. believe that caste and class were the real issues in Indian politics. and that, for thousands of years, the lower castes had been oppressed by the upper castes. In contemporary India, politics.

ROLE OF CAST IN INDIA POLITICS: In India, caste politics refers to the influence and impact of caste-based identities and considerations on political dynamics. Caste plays a significant role in Indian society, as it has historically been a fundamental social institution that categorizes people based on their birth, occupation, and social status.

: This study aims to explore the complex relationship between politics and caste in India, examining the historical context, socio-cultural factors, and the contemporary impact of caste-based politics on the Indian political landscape. The study will delve into the intricate interplay between caste identities, and political mobilization studies electoral outcomes, shedding light on how caste ...

Pahwa were also instrumental in my understanding of theories on ethnic politics and the dynamics of Indian politics. I am eternally grateful to my peers and family, who have helped shape my own viewpoints by exposing me to diverse perspectives and provided me opportunities to grasp rich experiential lessons. Without the lively debates I have

Some 200 members of Dalit and other castes attend a religious program to convert to Buddhism in Ahmedabad, India, on Sept. 30, 2017. SAM PANTHAKY/AFP via Getty Images The political manipulation of ...

'Political science can and should study the impact of religion on politics. This important book clearly articulates, and brilliantly demonstrates, how and why in India, high religious practice, more than caste, civil society, or parties, is the most significant variable associated with Indian citizens' positive sense of political representation.'

After Independence the Nehruvian approach to socialism in India rested upon three pillars: secularism and democracy in the political domain; state intervention in the economy; and diplomatic Non-Alignment mitigated by pro-Soviet leanings after the 1960s. These features defined the 'Indian model', and even the country's political identity. From this starting point Christophe Jaffrelot explores ...

31 Dec 2009 -. TL;DR: Christophe Jaffrelot tracks India's tumultuous journey of recent decades, exploring the role of religion, caste and politics in weaving the fabric of a modern democratic state as discussed by the authors. But the simultaneous and related rise of Hindu nationalism has put the minorities and secularism on the defensive, and ...

A major new Pew Research Center survey of religion across India, based on nearly 30,000 face-to-face interviews of adults conducted in 17 languages between late 2019 and early 2020 (before the COVID-19 pandemic ), finds that Indians of all these religious backgrounds overwhelmingly say they are very free to practice their faiths.

Please send us an extended abstract of around 500-800 words highlighting your research questions, arguments and data sources and a brief CV (max 2 page) by 30th June 2023, in Word format (.docx) to [email protected]. We will send our decisions on abstracts by 15th July 2023. Accepted papers will be due on 30th September 2022.

: The caste system is a predominant aspect of the social and political structure in India. Caste is the most ancient feature of Indian social system and it is a major factor in the structures and functions of the Indian political system. The word 'caste' is derived from the Spanish word 'caste' which means race. People born in particular race have their separate caste. It defines all ...

beliefs and rituals, and also freedom from discrimination on grounds of. religion, race, caste, place of birth, or gender.2 Article 30(1) recognises the. rights of religious minorities and, unlike other articles applicable to citizens qua individuals, it is a community-based right. Second, Article 30(2) commits.

Casteism and religion differences are more prominent in rural India and hence form a major part of "wants' ' of majority there. Urban India is not free from these either but the priorities ...

1. Religious freedom, discrimination and communal relations. By Neha Sahgal, Jonathan Evans, Ariana Monique Salazar, Kelsey Jo Starr and Manolo Corichi. Indians generally see high levels of religious freedom in their country. Overwhelming majorities of people in each major religious group, as well as in the overall public, say they are "very ...

The Pew Research Center's largest study of India explores the intersection of religion and identity politics. Bounded on the north by the Himalayas, east by the Ganges River and Bay of Bengal, west by the otherworldly salt marshes known as the Rann of Kutch, and south by the spice-scented Cardamom Hills, India's 1.4 billion citizens revere deities as diverse as their nation's topography ...

Reflections on modern India New Delhi: 73-87 Google Scholar. Bhattacharya, Jogendra Nath 1896 Hindu castes and sects (repr. 1973) Calcutta. Bhattacharya, Neeladri 1992 ' Agricultural labour and production ' in Prakash, Gyan (ed.), The world of the rural labourer in colonial India Delhi: 146-204 Google Scholar.

ROLE OF CASTE IN INDIAN POLITICS: 1. Caste and Political Parties: Caste is used as an important element of the Indian party system. Most of political parties in India are directly or indirectly have based on caste and protect the interests of a particular caste. The influence of caste is particularly noticeable among regional political parties.

Religion is important in Indian politics. It affects the country's politics and its democracy. India has many religions and people have strong beliefs. These beliefs affect politics. Religion has been used in different ways in India. Religion has been used in positive and negative ways in politics. It has been used to get people's support.

summarized by arguing that caste-based identity politics has had a dual role in Indian society and polity. It relatively democratized the cáste-based Indian society but simultaneously undermined the evolution of class-based organizations. In all, caste has become an important determinant in Indian society and politics, the

The ancient Hindu festival eschews the religious, societal, caste and political divisions that underpin India's often sectarian society. Hindu or not, anybody can be splashed with brightly ...

Moreover, as a woman from a political family, Bansuri may emerge as a voice for women's empowerment, advocating for greater representation of women in decision-making roles and promoting initiatives aimed at addressing gender-based disparities. Her mother's legacy as a trailblazer in Indian politics could serve as a guiding force in this ...

The Indian Journal of Political Science Vol. LXX, No. 3, July-Sept., 2009, pp. 705-718 RELIGION IN INDIAN POLITICS : Need to be Value Oriented, Not Power Oriented Zenab Banu The paper deals with contemporary issues and conflicts in Indian polity with reference to the debate of secularism and the use of religion in politics in India.