5 Secrets for Helping Middle School Writers Succeed

Even though I spent 19 years as a middle school teacher, I frequently ask myself what makes a middle school writing classroom work. I know successful teaching is a series of flexible moving parts. I know it’s one part inspiration and a bigger part organization. I know that every middle school teacher struggles to achieve more good days than bad.

In Traits of Writing: The Complete Guide for Middle School , I share meaningful and practical ideas for using what I’ve learned about teaching writing in middle school. My aim is to validate what you already know and give you new ways to support students. I also point out obstacles to watch out for and ways around them, so you don’t sacrifice the integrity of your teaching or the writing lives of your students.

As teachers, our greatest challenge may not be understanding best practices, but implementing those practices in classrooms where writing skills vary, time is precious, and the demand for high test scores can smother even the most creative teaching. But take heart. Teaching writing well is not impossible. Here are 5 secrets I know work in middle school and will help your young writers succeed:

1. The teacher must model how to learn.

If we want our students to write, we have to show them we are writers ourselves, which means opening ourselves up to scrutiny.

2. Learning should be infectious.

Look for inspiration everywhere and revise you lesson plans accordingly to foster a fascination with language, not just an understanding of terms. Who knows where this might lead?

3. Students must be active.

Engaging in lively activities, working in small groups, sitting on the floor, listening to music, using the computer, and talking about works in progress keep students moving, and therefore, learning.

4. Students will work hard if we give them rigorous, relevant tasks.

Let students take a giant leap forward and come up with their own projects and use the skills they have learned over the years to accomplish it. What they write matters less than the fact that they choose to write with such passion and determination.

5. Students deserve honest, detailed feedback.

Get serious about providing feedback. Students will appreciate your suggestions for making their writing smoother, clearer, and more interesting, and, like any serious writers, won’t always agree or follow them. But your students trust you to tell them the truth because they know your feedback, as difficult as it sometimes will be to convey, will help propel their work forward.

The secrets of writing, once locked away in the writing teacher’s vault, must be revealed and explored. How else will we sort out what works from what doesn’t? But you know this already. The writing lives of your middle school students depend on our getting it right.

To learn more about Traits of Writing: The Complete Guide for Middle School , you can purchase the book here.

About the author:

Ruth Culham, Ed.D., has published more than 40 best-selling professional books and resources with Scholastic and the International Literacy Association on the traits of writing and teaching writing using reading as a springboard to success. Her steadfast belief that every student is a writer is the hallmark of her work. As the author of Traits Writing: The Complete Writing Program for Grades K–8 (2012), she has launched a writing revolution. Traits Writing is the culmination of 40 years of educational experience, research, practice, and passion.

4 Activities to Help Middle School Students Uncover New Ideas for Writing

No matter how old you are, no matter how much writing you do, no matter how much you improve over time, finding ideas and writing about them clearly and compellingly is a challenge. Small wonder, then, that middle school writers find the ideas trait difficult to master.

Writing must make sense, and that’s what the ideas trait is all about—choosing a topic, narrowing it down, and supporting it with enough details to make the message clear and engaging. In Traits of Writing: The Complete Guide for Middle School , I outline the ideas trait’s 4 key qualities:

1. Finding a topic

2. Focusing the topic

3. Developing the topic

4. Using details

The following activities will help your students develop these qualities. Each is a creative, classroom-tested idea that allows students to try out skills and strategies that you share in warm-ups and focus lessons. These activities can take 5 minutes or 50, depending on your students’ needs and interest levels, and can be carried out by students independently or in small groups.

Finding a topic | Writer’s Notebooks

Often, the best topics are the ones students come up with themselves. As you work with students, encourage them to jot down in a notebook possible ideas for use in writing later—ideas that occur to them during science, social studies, health, fine arts, or English, or in everyday life. Let students select a notebook that makes them feel comfortable. Keep your own notebook and model how you jot down ideas for writing, words and phrases you like, intriguing information and observations, and questions to ponder.

Focusing the topic | The Best and the Worst Activity

Have your students brainstorm a list of real-world jobs that require a great deal of writing: a writer for a late-night talk show, a fund-raiser for a charity, a developer of video games, an author of children’s books, and so on. Write the jobs on a chart. Divide the class into small groups and assign one of the jobs to each group. Ask group members to prepare a panel presentation explaining the best and worst parts of the job and present it to the class, using some sort of visual aid that illustrates key points, such as a chart or diagram. Hang their creations in a prominent place for everyone to read and think about. This activity teaches students that writing is a big part of most professions—a lesson they will come to learn on their own soon enough.

Developing the topic | Top-Ten List

Ask students to write a top-ten list of things every adult should know about middle school students. Encourage them to develop each point in a fun, truthful, and interesting way. Here are examples of 2 developed points:

We don’t like to be told what to do. But if you don’t tell us, we won’t do it. And even when you do tell us, many times we don’t do it unless you get mean about it. We’re kinda flakey.

Remembering to put our names on our papers is harder than being blindfolded and sending a text message with our thumbs.

Using details | Getting Into the Details Activity

Give students a general statement, such as “I love Friday,” and ask them to work with a partner to brainstorm at least 10 details that explain why Friday is their favorite school day. Have pairs share those details with the whole class and make one long list. Now ask students to select their favorite details, at least 5 but no more than 10, and choose the one they consider the most important. From there, have pairs write a paragraph describing all the great things about Friday, emphasizing one detail they feel is most important. When they’re finished, ask students to put their paragraphs on their desks and invite their classmates to walk about and read them. Later, discuss the techniques students used to focus the reader’s attention on one detail more than others.

The time you spend teaching students where ideas come from and how to develop them effectively is critical to their success as writers. Finding a topic, focusing it, developing it, and using precise details to support it is where the writing begins.

Learn more about the ideas trait and other traits critical to writing success with Traits of Writing: The Complete Guide for Middle School . You can purchase the book here .

- CORE CURRICULUM

- LITERACY > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Literature, 6-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Literature, 6-12" aria-label="Into Literature, 6-12"> Into Literature, 6-12

- LITERACY > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Reading, K-6" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Reading, K-6" aria-label="Into Reading, K-6"> Into Reading, K-6

- INTERVENTION

- LITERACY > INTERVENTION > English 3D, 4-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="English 3D, 4-12" aria-label="English 3D, 4-12"> English 3D, 4-12

- LITERACY > INTERVENTION > Read 180, 3-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Read 180, 3-12" aria-label="Read 180, 3-12"> Read 180, 3-12

- LITERACY > READERS > Hero Academy Leveled Libraries, PreK-4" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Hero Academy Leveled Libraries, PreK-4" aria-label="Hero Academy Leveled Libraries, PreK-4"> Hero Academy Leveled Libraries, PreK-4

- LITERACY > READERS > HMH Reads Digital Library, K-5" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="HMH Reads Digital Library, K-5" aria-label="HMH Reads Digital Library, K-5"> HMH Reads Digital Library, K-5

- LITERACY > READERS > inFact Leveled Libraries, K-5" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="inFact Leveled Libraries, K-5" aria-label="inFact Leveled Libraries, K-5"> inFact Leveled Libraries, K-5

- LITERACY > READERS > Rigby PM, K-5" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Rigby PM, K-5" aria-label="Rigby PM, K-5"> Rigby PM, K-5

- LITERACY > READERS > Science & Engineering Leveled Readers, K-5" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Science & Engineering Leveled Readers, K-5" aria-label="Science & Engineering Leveled Readers, K-5"> Science & Engineering Leveled Readers, K-5

- SUPPLEMENTAL

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > A Chance in the World SEL, 8-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="A Chance in the World SEL, 8-12" aria-label="A Chance in the World SEL, 8-12"> A Chance in the World SEL, 8-12

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > Amira Learning, K-6" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Amira Learning, K-6" aria-label="Amira Learning, K-6"> Amira Learning, K-6

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > Classcraft, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Classcraft, K-8" aria-label="Classcraft, K-8"> Classcraft, K-8

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > JillE Literacy, K-3" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="JillE Literacy, K-3" aria-label="JillE Literacy, K-3"> JillE Literacy, K-3

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > Waggle, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Waggle, K-8" aria-label="Waggle, K-8"> Waggle, K-8

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > Writable, 3-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Writable, 3-12" aria-label="Writable, 3-12"> Writable, 3-12

- LITERACY > SUPPLEMENTAL > ASSESSMENT" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="ASSESSMENT" aria-label="ASSESSMENT"> ASSESSMENT

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Arriba las Matematicas, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Arriba las Matematicas, K-8" aria-label="Arriba las Matematicas, K-8"> Arriba las Matematicas, K-8

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Go Math!, K-6" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Go Math!, K-6" aria-label="Go Math!, K-6"> Go Math!, K-6

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Algebra 1, Geometry, Algebra 2, 8-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Algebra 1, Geometry, Algebra 2, 8-12" aria-label="Into Algebra 1, Geometry, Algebra 2, 8-12"> Into Algebra 1, Geometry, Algebra 2, 8-12

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Math, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Math, K-8" aria-label="Into Math, K-8"> Into Math, K-8

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Math Expressions, PreK-6" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Math Expressions, PreK-6" aria-label="Math Expressions, PreK-6"> Math Expressions, PreK-6

- MATH > CORE CURRICULUM > Math in Focus, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Math in Focus, K-8" aria-label="Math in Focus, K-8"> Math in Focus, K-8

- MATH > SUPPLEMENTAL > Classcraft, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Classcraft, K-8" aria-label="Classcraft, K-8"> Classcraft, K-8

- MATH > SUPPLEMENTAL > Waggle, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Waggle, K-8" aria-label="Waggle, K-8"> Waggle, K-8

- MATH > INTERVENTION > Math 180, 5-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Math 180, 5-12" aria-label="Math 180, 5-12"> Math 180, 5-12

- SCIENCE > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Science, K-5" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Science, K-5" aria-label="Into Science, K-5"> Into Science, K-5

- SCIENCE > CORE CURRICULUM > Into Science, 6-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Into Science, 6-8" aria-label="Into Science, 6-8"> Into Science, 6-8

- SCIENCE > CORE CURRICULUM > Science Dimensions, K-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Science Dimensions, K-12" aria-label="Science Dimensions, K-12"> Science Dimensions, K-12

- SCIENCE > READERS > inFact Leveled Readers, K-5" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="inFact Leveled Readers, K-5" aria-label="inFact Leveled Readers, K-5"> inFact Leveled Readers, K-5

- SCIENCE > READERS > Science & Engineering Leveled Readers, K-5" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Science & Engineering Leveled Readers, K-5" aria-label="Science & Engineering Leveled Readers, K-5"> Science & Engineering Leveled Readers, K-5

- SCIENCE > READERS > ScienceSaurus, K-8" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="ScienceSaurus, K-8" aria-label="ScienceSaurus, K-8"> ScienceSaurus, K-8

- SOCIAL STUDIES > CORE CURRICULUM > HMH Social Studies, 6-12" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="HMH Social Studies, 6-12" aria-label="HMH Social Studies, 6-12"> HMH Social Studies, 6-12

- SOCIAL STUDIES > SUPPLEMENTAL > Writable" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Writable" aria-label="Writable"> Writable

- For Teachers

- PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT > For Teachers > Coachly" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Coachly" aria-label="Coachly"> Coachly

- PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT > For Teachers > Teacher's Corner" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Teacher's Corner" aria-label="Teacher's Corner"> Teacher's Corner

- PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT > For Teachers > Live Online Courses" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Live Online Courses" aria-label="Live Online Courses"> Live Online Courses

- For Leaders

- PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT > For Leaders > The Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="The Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)" aria-label="The Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)"> The Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)

- MORE > undefined > Assessment" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Assessment" aria-label="Assessment"> Assessment

- MORE > undefined > Early Learning" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Early Learning" aria-label="Early Learning"> Early Learning

- MORE > undefined > English Language Development" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="English Language Development" aria-label="English Language Development"> English Language Development

- MORE > undefined > Homeschool" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Homeschool" aria-label="Homeschool"> Homeschool

- MORE > undefined > Intervention" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Intervention" aria-label="Intervention"> Intervention

- MORE > undefined > Literacy" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Literacy" aria-label="Literacy"> Literacy

- MORE > undefined > Mathematics" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Mathematics" aria-label="Mathematics"> Mathematics

- MORE > undefined > Professional Development" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Professional Development" aria-label="Professional Development"> Professional Development

- MORE > undefined > Science" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Science" aria-label="Science"> Science

- MORE > undefined > undefined" data-element-type="header nav submenu">

- MORE > undefined > Social and Emotional Learning" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Social and Emotional Learning" aria-label="Social and Emotional Learning"> Social and Emotional Learning

- MORE > undefined > Social Studies" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Social Studies" aria-label="Social Studies"> Social Studies

- MORE > undefined > Special Education" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Special Education" aria-label="Special Education"> Special Education

- MORE > undefined > Summer School" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Summer School" aria-label="Summer School"> Summer School

- BROWSE RESOURCES

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Classroom Activities" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Classroom Activities" aria-label="Classroom Activities"> Classroom Activities

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Customer Success Stories" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Customer Success Stories" aria-label="Customer Success Stories"> Customer Success Stories

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Digital Samples" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Digital Samples" aria-label="Digital Samples"> Digital Samples

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Events" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Events" aria-label="Events"> Events

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Grants & Funding" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Grants & Funding" aria-label="Grants & Funding"> Grants & Funding

- BROWSE RESOURCES > International" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="International" aria-label="International"> International

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Research Library" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Research Library" aria-label="Research Library"> Research Library

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Shaped - HMH Blog" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Shaped - HMH Blog" aria-label="Shaped - HMH Blog"> Shaped - HMH Blog

- BROWSE RESOURCES > Webinars" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Webinars" aria-label="Webinars"> Webinars

- CUSTOMER SUPPORT

- CUSTOMER SUPPORT > Contact Sales" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Contact Sales" aria-label="Contact Sales"> Contact Sales

- CUSTOMER SUPPORT > Customer Service & Technical Support Portal" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Customer Service & Technical Support Portal" aria-label="Customer Service & Technical Support Portal"> Customer Service & Technical Support Portal

- CUSTOMER SUPPORT > Platform Login" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Platform Login" aria-label="Platform Login"> Platform Login

- Learn about us

- Learn about us > About" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="About" aria-label="About"> About

- Learn about us > Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion" aria-label="Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion"> Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Learn about us > Environmental, Social, and Governance" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Environmental, Social, and Governance" aria-label="Environmental, Social, and Governance"> Environmental, Social, and Governance

- Learn about us > News Announcements" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="News Announcements" aria-label="News Announcements"> News Announcements

- Learn about us > Our Legacy" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Our Legacy" aria-label="Our Legacy"> Our Legacy

- Learn about us > Social Responsibility" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Social Responsibility" aria-label="Social Responsibility"> Social Responsibility

- Learn about us > Supplier Diversity" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Supplier Diversity" aria-label="Supplier Diversity"> Supplier Diversity

- Join Us > Careers" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Careers" aria-label="Careers"> Careers

- Join Us > Educator Input Panel" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Educator Input Panel" aria-label="Educator Input Panel"> Educator Input Panel

- Join Us > Suppliers and Vendors" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Suppliers and Vendors" aria-label="Suppliers and Vendors"> Suppliers and Vendors

- Divisions > Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)" aria-label="Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)"> Center for Model Schools (formerly ICLE)

- Divisions > Heinemann" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="Heinemann" aria-label="Heinemann"> Heinemann

- Divisions > NWEA" data-element-type="header nav submenu" title="NWEA" aria-label="NWEA"> NWEA

- Platform Login

SOCIAL STUDIES

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

8 Tips for Teaching Middle School Writing

Middle school is the first-time students learn in-depth writing, and it usually starts with essays. Although writing intimidates many children, the good news is that tweens and young teens have many interests, opinions, and ideas that teachers can help draw out and shape.

Middle-school students are old enough to have experienced a healthy dose of “life,” and with that comes family stories, memories of imaginative play when they were younger, knowledge gleaned from books they’ve read, and curiosity piqued by places they’ve been and events they’ve witnessed. So, they can certainly have a lot to say. Teaching writing to middle schoolers can be an excellent opportunity for educators to really get to know their students and allow them to express their own unique voices.

Here are eight middle school writing strategies teachers can use to improve these skills for students.

Teaching Writing to Middle Schoolers

Tip 1: give them the freedom to freewrite.

Some middle schoolers may look like the proverbial deer in a headlight when you tell them it’s time to write. While writing can be a positive experience and thousands of people write for enjoyment, stress relief, and other productive benefits, some students might find it intimidating. One positive approach is to give students the opportunity to freewrite in personal journals that they will not be required to share unless they choose to. Set a timer for five minutes and tell students to write whatever comes into their minds, without stopping, for the duration. What they write is up to them—it can be a list of random words, a description of what they had for breakfast, or sentences such as “I have no idea what to write!” The important part is to keep the pencil moving across the page. Grammar and spelling don’t matter for this exercise, and students will not be graded or judged on their work.

Tip 2: Start with Poetry

Another great access point to writing is to start with poetry. Glenis Redmond, a poet and teaching artist, says, “When I enter a classroom, I always begin with praise—a praise poem , that is—an introductory poem of origin—because it is an accessible poem form for students and teachers to begin writing. It also allows me to assess where students are developmentally…These poems are made up of metaphors and similes—forms of comparison relating the writer to an object, a person, a color, or a feature in nature.”

“There is a strong correlation between readers of poetry and writers of poetry,” says Ekuwah Moses , an elementary educator, nonfiction picture book author, and literacy specialist from Las Vegas. “Some teachers set up a staged area of their classroom for students to perform weekly open mic time. This is an opportunity for students to read poetry they have written out loud to their peers or read aloud a poet's work. It is a community-building celebration of writing, reading, speaking, and listening.”

Tip 3: Use Anchor Charts

Anchor charts can be an excellent collaborative tool to engage and motivate students in their writing. According to this document from the International Literacy Association, “Anchor charts are organized mentor texts co-created with students. Charts are usually handwritten in large print and displayed in an area of the classroom where they can be easily seen. Used to anchor whole group instruction, the charts provide a scaffold during guided practice and independent work.”

Anchor charts are intended to be homemade—capturing what the students have learned and then remaining on display as an artifact for future reference. Although bold lettering and bright colors can make an anchor chart stand out, you don’t need superior artistic skills to create one; just a pack of markers and some large chart paper will do the trick! An anchor chart for writing could, for example, capture a list of words students could use to replace overused words such as “said” or “very.” It could be an inspirational “doodle-style” sketch of all the reasons writers write, e.g., to share their feelings, to tell their own story, to persuade someone, or to inform people about important events. Or it could show a diagram of how to create an organized paragraph with a hook/topic sentence, details, and a closing statement.

Resources for Teachers : Download these printable anchor charts from HMH Into Literature .

Tip 4: Create a Toolkit of Graphic Organizers

It’s helpful for middle schoolers to organize their ideas before they put pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard). You can make toolkits by assembling file folders with a selection of graphic organizers that can help them brainstorm ideas and create an orderly sequence of thoughts. For example, students could use this word web to break down the larger topic of “The Arctic” into details such as “wildlife,” “climate,” and “geography.”

Other tools that can encourage students to connect more deeply with a topic include a 5 Ws chart , Venn diagram , and KWL chart .

Ekuwah Moses adds: “Keep the brain in mind when using graphic organizers. Handwritten or hand-drawn organizers are the best method for learning to write. The process of drawing and writing teaches children how to organize information for long-term retrieval, versus relying upon or always searching for a pre-made document.”

Tip 5: Break It Down and Give Frequent Feedback

Students can sometimes feel as if writing is subjective. What makes one short story “better” than the next, anyway? Indeed, some of this does relate to a gut instinct: We know when a story or an essay moves us and captures our attention. We know when a character feels real, and we can hear when words are used lyrically to make a piece of writing “sing.” But by showing students that a great piece of writing comes from a series of steps that include prewriting, drafting, and revision, you can demystify the process.

By breaking the writing process—including feedback and evaluation—into bite-sized pieces, you can make the learning more manageable and help students see their progress. Research shows that delivering quality feedback leads to better revisions and results. The real-time, personalized feedback in a program such as Writable helps empower students every step of the way.

Nick Wheeler, a sixth-grade ELA teacher at Bristow Elementary in Kentucky, uses the tools and instructional supports available in Writable to help students take ownership of their writing. The students “are part of each piece of that writing process, from freewriting, to drafting, to revising and editing, and finally publishing,” he says.

Tip 6: Model Your Own Writing Process for Students

Even published authors rarely, if ever, churn out a perfect first draft. It may encourage students to realize that their favorite books were the result of many revisions and, often, collaboration with editors and proofreaders. You can model this process for students in a couple of ways. First, you can talk through the thought process that you go through when writing—for example, a letter to your local town council.

Share your thought process out loud as you write quick notes that the class can see. For example, “Okay, I would like to have a place for my dog to play freely with other dogs. I’d love it if the town created a dog park.” Write “dog park” in the center of the whiteboard as your main topic, and circle it.

You might continue to share further thoughts out loud: “But hmm, I know it might cost money and require community support. What points could I make to convince my readers that a dog park would be a great asset to this town? Maybe I could suggest that the dog park requires a small membership fee, which would bring revenue to the town? Maybe I could suggest that this park might encourage more rescue pet adoptions?” Add “paid membership” and “pet adoptions” to the whiteboard as “spokes” coming from the main topic, as well as any suggestions students might offer.

Then, talk the class through your plans as to how you might organize all these points into a coherent and persuasive piece. Lastly, you could then explain how you might ask a colleague to be your editor and review your letter. Does it make sense to them? Do they find it persuasive? Do they see any errors in spelling or grammar? Students can partner with peers to do the same!

Tip 7: Teach Them to Read Like Writers and Write Like Readers

“It’s important to remember that reading and writing are interconnected,” says Michael Vea, a former classroom teacher and now an education systems-level leader at San Diego Unified School District. “When they read, students can be thinking like writers; e.g., How did the writer of this text craft such a beautiful piece? How did the vocabulary words they chose make the piece more powerful? And when they write, they can think like readers; e.g., How will this piece of writing be received? What emotional reaction might the reader get?”

“One of my favorite mentors in my professional training, Pam Allyn, the founder of LitWorld , used to say that ‘Reading is like breathing in and writing is like breathing out.’,” he adds. “That always resonated with me.”

One tactic to get writers thinking like readers (and vice versa) is to use model writing pieces, such as those available in the Writer’s Notebook in Into Reading , examples of authentic student writing, or photocopies of a favorite passage from a piece of literature. Annotating a sample piece of writing can help scaffold the writing process for students. “We reference the model writing during each day of drafting, editing, and revising,” says Rhode Island teacher Kayla Dyer. “I will prompt students to refer to the model piece as they are drafting so I can have individual conferences or small group conferences.”

Here is an example of how Dyer annotated a piece of nonfiction writing, “The Amazing Sea Pig.”

Tip 8: Use Rubrics

Rubrics are your friend when it comes to writing. They help students build confidence and give teachers a way to help family members understand their grading process. A rubric lets students know and see the expectations and exactly what they will be graded on. Self-review in writing is so important, and a rubric can ensure that students learn to check their work for content as well as for grammar.

“You can further build a writing culture by frequently pulling exemplar student writing, gathered from your classroom or across the grade level, and discussing it anonymously with the class,” recommends Ekuwah Moses. “Project the exemplar, and then use the grade-level writing rubric to highlight where it meets or exceeds the expectations of the rubric. These positive examples help students to see that the ‘impossible' is possible, and students whose work is featured appreciate the praise.”

Another benefit of rubrics is that they can facilitate self-assessment. In addition to evaluating their work against the criteria laid out in the rubric, students can reflect on their writing assignments by answering three questions:

- What did you like best about this assignment?

- What was the most difficult part?

- What do you want me to know about this work you did?

Teaching writing for middle schoolers can be rewarding, frustrating, or both at the same time, but working through the process and giving clear feedback every step of the way can empower your students and help them learn the value of their words. Showing your students how to use their voices can be one of the greatest gifts you can give them, especially if you do it thoughtfully.

Need additional support to improve writing skills in middle school? Try Writable to support your ELA curriculum, district benchmarks, and state standards with more than 600 fully customizable writing assignments and rubrics for students in Grades 3–12. Learn more .

- Professional Learning

Related Reading

Differentiated Instruction Strategies and Examples for Teacher and Student Success

Shaped Contributor

March 26, 2024

What Is Academic Vocabulary?

Jennifer Corujo Shaped Editor

March 25, 2024

Podcast: Partnering with Families to Build Early Literacy Skills with Melissa Hawkins in HI on Teachers in America

March 21, 2024

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Our 2020-21 Writing Curriculum for Middle and High School

A flexible, seven-unit program based on the real-world writing found in newspapers, from editorials and reviews to personal narratives and informational essays.

Update, Aug. 3, 2023: Find our 2023-24 writing curriculum here.

Our 2019-20 Writing Curriculum is one of the most popular new features we’ve ever run on this site, so, of course, we’re back with a 2020-21 version — one we hope is useful whether you’re teaching in person , online , indoors , outdoors , in a pod , as a homeschool , or in some hybrid of a few of these.

The curriculum detailed below is both a road map for teachers and an invitation to students. For teachers, it includes our writing prompts, mentor texts, contests and lesson plans, and organizes them all into seven distinct units. Each focuses on a different genre of writing that you can find not just in The Times but also in all kinds of real-world sources both in print and online.

But for students, our main goal is to show young people they have something valuable to say, and to give those voices a global audience. That’s always been a pillar of our site, but this year it is even more critical. The events of 2020 will define this generation, and many are living through them isolated from their ordinary communities, rituals and supports. Though a writing curriculum can hardly make up for that, we hope that it can at least offer teenagers a creative outlet for making sense of their experiences, and an enthusiastic audience for the results. Through the opportunities for publication woven throughout each unit, we want to encourage students to go beyond simply being media consumers to become creators and contributors themselves.

So have a look, and see if you can find a way to include any of these opportunities in your curriculum this year, whether to help students document their lives, tell stories, express opinions, investigate ideas, or analyze culture. We can’t wait to hear what your students have to say!

Each unit includes:

Writing prompts to help students try out related skills in a “low stakes” way.

We publish two writing prompts every school day, and we also have thematic collections of more than 1,000 prompts published in the past. Your students might consider responding to these prompts on our site and using our public forums as a kind of “rehearsal space” for practicing voice and technique.

Daily opportunities to practice writing for an authentic audience.

If a student submits a comment on our site, it will be read by Times editors, who approve each one before it gets published. Submitting a comment also gives students an audience of fellow teenagers from around the world who might read and respond to their work. Each week, we call out our favorite comments and honor dozens of students by name in our Thursday “ Current Events Conversation ” feature.

Guided practice with mentor texts .

Each unit we publish features guided practice lessons, written directly to students, that help them observe, understand and practice the kinds of “craft moves” that make different genres of writing sing. From how to “show not tell” in narratives to how to express critical opinions , quote or paraphrase experts or craft scripts for podcasts , we have used the work of both Times journalists and the teenage winners of our contests to show students techniques they can emulate.

“Annotated by the Author” commentaries from Times writers — and teenagers.

As part of our Mentor Texts series , we’ve been asking Times journalists from desks across the newsroom to annotate their articles to let students in on their writing, research and editing processes, and we’ll be adding more for each unit this year. Whether it’s Science writer Nicholas St. Fleur on tiny tyrannosaurs , Opinion writer Aisha Harris on the cultural canon , or The Times’s comics-industry reporter, George Gene Gustines, on comic books that celebrate pride , the idea is to demystify journalism for teenagers. This year, we’ll be inviting student winners of our contests to annotate their work as well.

A contest that can act as a culminating project .

Over the years we’ve heard from many teachers that our contests serve as final projects in their classes, and this curriculum came about in large part because we want to help teachers “plan backwards” to support those projects.

All contest entries are considered by experts, whether Times journalists, outside educators from partner organizations, or professional practitioners in a related field. Winning means being published on our site, and, perhaps, in the print edition of The New York Times.

Webinars and our new professional learning community (P.L.C.).

For each of the seven units in this curriculum, we host a webinar featuring Learning Network editors as well as teachers who use The Times in their classrooms. Our webinars introduce participants to our many resources and provide practical how-to’s on how to use our prompts, mentor texts and contests in the classroom.

New for this school year, we also invite teachers to join our P.L.C. on teaching writing with The Times , where educators can share resources, strategies and inspiration about teaching with these units.

Below are the seven units we will offer in the 2020-21 school year.

September-October

Unit 1: Documenting Teenage Lives in Extraordinary Times

This special unit acknowledges both the tumultuous events of 2020 and their outsized impact on young people — and invites teenagers to respond creatively. How can they add their voices to our understanding of what this historic year will mean for their generation?

Culminating in our Coming of Age in 2020 contest, the unit helps teenagers document and respond to what it’s been like to live through what one Times article describes as “a year of tragedy, of catastrophe, of upheaval, a year that has inflicted one blow after another, a year that has filled the morgues, emptied the schools, shuttered the workplaces, swelled the unemployment lines and polarized the electorate.”

A series of writing prompts, mentor texts and a step-by-step guide will help them think deeply and analytically about who they are, how this year has impacted them, what they’d like to express as a result, and how they’d like to express it. How might they tell their unique stories in ways that feel meaningful and authentic, whether those stories are serious or funny, big or small, raw or polished?

Though the contest accepts work across genres — via words and images, video and audio — all students will also craft written artist’s statements for each piece they submit. In addition, no matter what genre of work students send in, the unit will use writing as a tool throughout to help students brainstorm, compose and edit. And, of course, this work, whether students send it to us or not, is valuable far beyond the classroom: Historians, archivists and museums recommend that we all document our experiences this year, if only for ourselves.

October-November

Unit 2: The Personal Narrative

While The Times is known for its award-winning journalism, the paper also has a robust tradition of publishing personal essays on topics like love , family , life on campus and navigating anxiety . And on our site, our daily writing prompts have long invited students to tell us their stories, too. Our 2019 collection of 550 Prompts for Narrative and Personal Writing is a good place to start, though we add more every week during the school year.

In this unit we draw on many of these resources, plus some of the 1,000-plus personal essays from the Magazine’s long-running Lives column , to help students find their own “short, memorable stories ” and tell them well. Our related mentor-text lessons can help them practice skills like writing with voice , using details to show rather than tell , structuring a narrative arc , dropping the reader into a scene and more. This year, we’ll also be including mentor text guided lessons that use the work of the 2019 student winners.

As a final project, we invite students to send finished stories to our Second Annual Personal Narrative Writing Contest .

DECEMBER-January

Unit 3: The Review

Book reports and literary essays have long been staples of language arts classrooms, but this unit encourages students to learn how to critique art in other genres as well. As we point out, a cultural review is, of course, a form of argumentative essay. Your class might be writing about Lizzo or “ Looking for Alaska ,” but they still have to make claims and support them with evidence. And, just as they must in a literature essay, they have to read (or watch, or listen to) a work closely; analyze it and understand its context; and explain what is meaningful and interesting about it.

In our Mentor Texts series , we feature the work of Times movie , restaurant , book and music critics to help students understand the elements of a successful review. In each one of these guided lessons, we also spotlight the work of teenage contest winners from previous years.

As a culminating project, we invite students to send us their own reviews of a book, movie, restaurant, album, theatrical production, video game, dance performance, TV show, art exhibition or any other kind of work The Times critiques.

January-February

Unit 4: Informational Writing

Informational writing is the style of writing that dominates The New York Times as well as any other traditional newspaper you might read, and in this unit we hope to show students that it can be every bit as engaging and compelling to read and to write as other genres. Via thousands of articles a month — from front-page reporting on politics to news about athletes in Sports, deep data dives in The Upshot, recipes in Cooking, advice columns in Style and long-form investigative pieces in the magazine — Times journalists find ways to experiment with the genre to intrigue and inform their audiences.

This unit invites students to take any STEM-related discovery, process or idea that interests them and write about it in a way that makes it understandable and engaging for a general audience — but all the skills we teach along the way can work for any kind of informational writing. Via our Mentor Texts series, we show them how to hook the reader from the start , use quotes and research , explain why a topic matters and more. This year we’ll be using the work of the 2020 student winners for additional mentor text lessons.

At the end of the unit, we invite teenagers to submit their own writing to our Second Annual STEM writing contest to show us what they’ve learned.

March-April

Unit 5: Argumentative Writing

The demand for evidence-based argumentative writing is now woven into school assignments across the curriculum and grade levels, and you couldn’t ask for better real-world examples than what you can find in The Times Opinion section .

This unit will, like our others, be supported with writing prompts, mentor-text lesson plans, webinars and more. We’ll also focus on the winning teenage writing we’ve received over the six years we’ve run our related contest.

At a time when media literacy is more important than ever, we also hope that our annual Student Editorial Contest can serve as a final project that encourages students to broaden their information diets with a range of reliable sources, and learn from a variety of perspectives on their chosen issue.

To help students working from home, we also have an Argumentative Unit for Students Doing Remote Learning .

Unit 6: Writing for Podcasts

Most of our writing units so far have all asked for essays of one kind or another, but this spring contest invites students to do what journalists at The Times do every day: make multimedia to tell a story, investigate an issue or communicate a concept.

Our annual podcast contest gives students the freedom to talk about anything they want in any form they like. In the past we’ve had winners who’ve done personal narratives, local travelogues, opinion pieces, interviews with community members, local investigative journalism and descriptions of scientific discoveries.

As with all our other units, we have supported this contest with great examples from The Times and around the web, as well as with mentor texts by teenagers that offer guided practice in understanding elements and techniques.

June-August

Unit 7: Independent Reading and Writing

At a time when teachers are looking for ways to offer students more “voice and choice,” this unit, based on our annual summer contest, offers both.

Every year since 2010 we have invited teenagers around the world to add The New York Times to their summer reading lists and, so far, 70,000 have. Every week for 10 weeks, we ask participants to choose something in The Times that has sparked their interest, then tell us why. At the end of the week, judges from the Times newsroom pick favorite responses, and we publish them on our site.

And we’ve used our Mentor Text feature to spotlight the work of past winners , explain why newsroom judges admired their thinking, and provide four steps to helping any student write better reader-responses.

Because this is our most open-ended contest — students can choose whatever they like, and react however they like — it has proved over the years to be a useful place for young writers to hone their voices, practice skills and take risks . Join us!

- HOW TO GET STUDENTS WRITING IN 5 MINUTES OR LESS

Writer’s Workshop Middle School: The Ultimate Guide

Feb 23, 2021

Writer’s Workshop Middle School: The Ultimate Guide defines the writer’s workshop model, its essential components, pros and cons, step-by-step set-up, and further resources.

What is the writer’s workshop model?

Writer’s workshop is a method of teaching writing developed by Donald Graves and Donald Murray , amongst other teacher-researchers.

The writer’s workshop provides a student-centered environment where students are given time, choice, and voice in their learning. The teacher nurtures the class by creating and mentoring a community of writers.

So, why does the writer’s workshop in middle school matter?

Students learn more during the writer’s workshop because you can mentor them toward what they need to know and practice, and they have lots of time to write and read in order to improve at their own pace (to an extent).

For example, if the skill I need to teach is how authors use mood and tone to create meaning , then I would use a mentor text to teach that concept. However, after reading, the focus will not be on answering questions about the text in written form. Instead, I demonstrate how writers choose particular words and the arrangement of those words to create a mood and tone.

Students then try creating mood and tone with their own pieces of writing. Only after students have practiced their own creations, do I then circle back around to other literature for students to practice literary analysis of mood and tone and its effect on meaning.

Why I focus on writing in the ELA classroom?

I’ve found students are more likely to read assigned texts if I’ve given them a reason to use those texts. That reason? To apply what they learn from mentor texts to their choice writing. Middle school students love to express themselves in creative ways, and by giving students this choice, you build engagement and motivation to continue learning.

The essential components of the writer’s workshop in middle school are:

- Time to write daily

- Student choice

- Exploring the writer’s voice

- Building a community of writers

- Mentor teaching

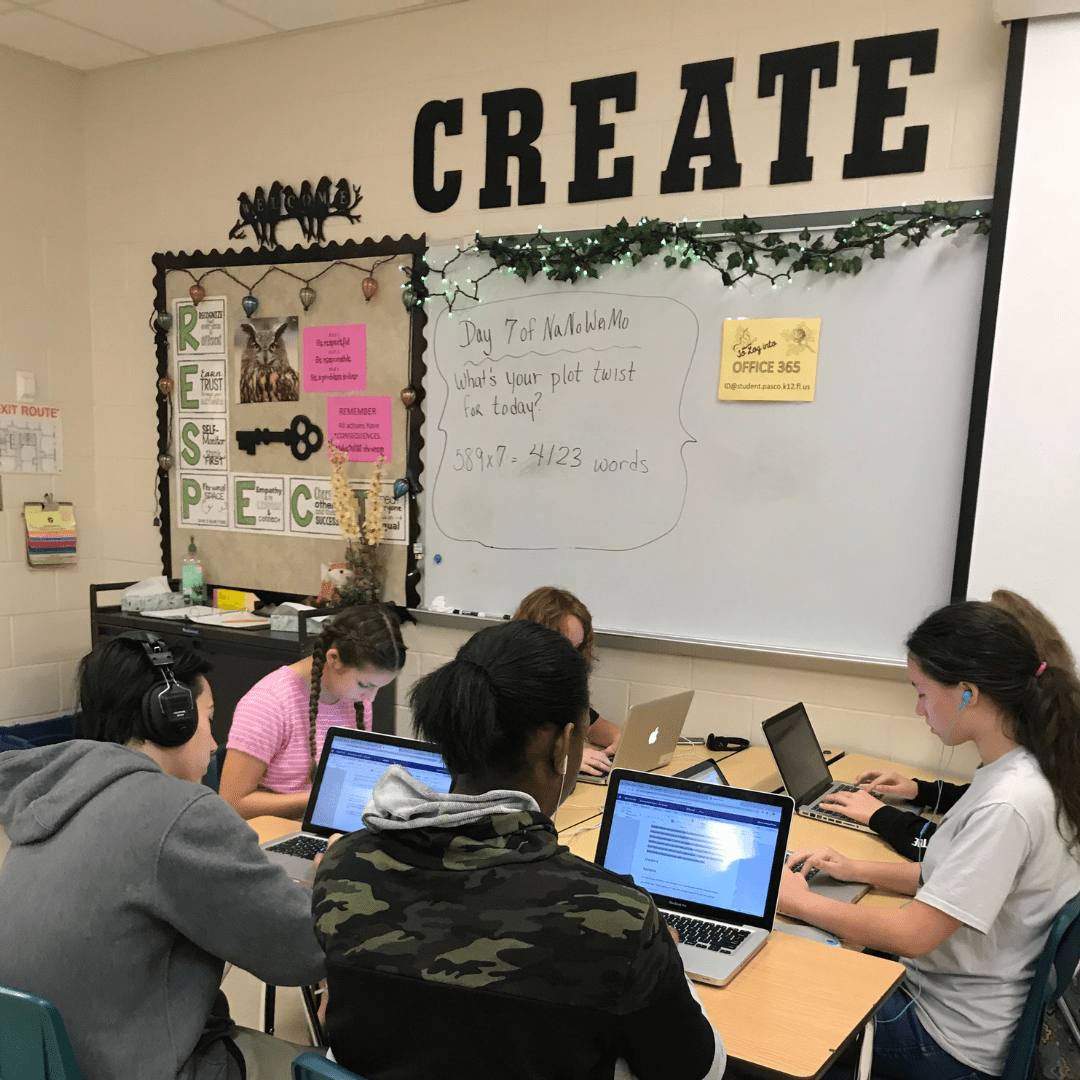

1. Time to Write Daily

Students need a chance to write daily. Various ways you can do this are through Bell Ringers at the beginning of the class, writing during the mini-lesson, and writing projects during workshop time. My students use writing journals because they need a space to think before they face a blank computer screen.

Students do read in my classes. However, their purpose for reading is to become better writers. This reading is either assigned, student choice, or a choice between the assigned reading and student choice, depending on the skill or concept I’m targeting that week.

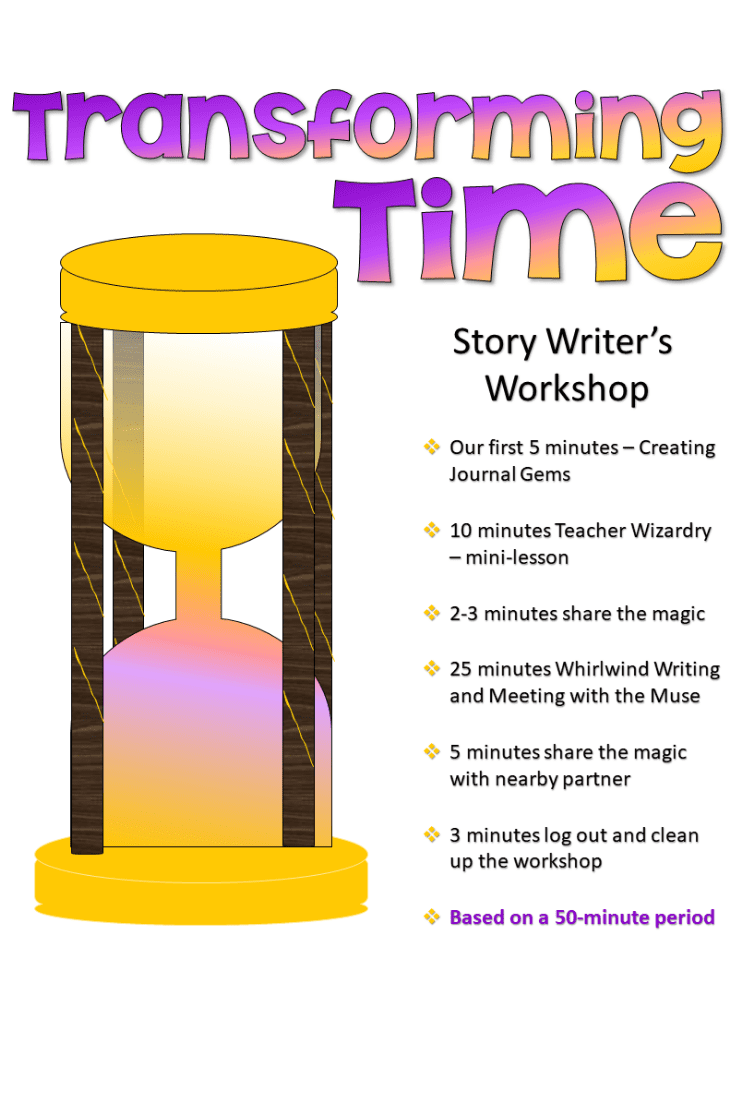

This is how I break up our daily writing:

- Write Now (bell ringer)

- Mini-lesson and sharing

- Writing/Reading Workshop while I confer with writers

- Short turn and talk, log off computers and pack up

Below is an example of my story writer’s workshop time transformation. This is what I use when we are writing narratives. I’m using a fantasy magic theme here:

2. Student Choice

To keep students motivated to write, you want to build in student choice whenever and wherever possible. Just to clarify, you don’t have to give them choices for everything they do.

For one thing, that would be as overwhelming as shopping on the cereal aisle at your local grocery store. Just too many choices.

When I introduce a concept, I may give them a few choices on how students can practice that concept. If I give them a writing assignment, I often allow them ONE choice in topic, genre, audience, or mode of writing.

If you need students to complete an assignment/activity within a certain time period, tell them ahead of time. Let them know they can turn in an excerpt if they want to write something longer than you expect.

Of course, this is not always possible. They need to learn how to write within certain time parameters. So, let them practice this through timed writings or word sprints .

One way to help students with choice is to have them do listing activities frequently. They could even have a section in their writing notebooks just for lists of ideas.

3. Exploring the writer’s voice

Writer’s voice – that elusive term that most writers have no idea how to achieve until they’ve written for a while, and then finally realize they have it. The ultimate goal for me as a writing teacher is to help my students to find their voice.

I want students to be able to explore what is important to them personally and to explore how they can share this with others. From encouraging students to participate in small group sharing to author’s celebrations, students need the opportunity to see their writing voice matters.

There are so many different ways for kids to publish safely online – Edublogs, Adobe Spark, Google Sites, FlipGrid, etc.

4. Building a community of writers in your writer’s workshop for middle school

Middle school students are very social, but even the quiet writers need to socialize often with other writers. This component of the writer’s workshop for middle school is what makes this model an actual workshop.

Students share their writing with each other. Usually, I allow for natural partnerships and groups to form. However, at the beginning of the year, I often pair up students for short activities. This helps everyone feel more comfortable with each other.

One way I build a community of writers is to play the name game at the beginning of the year. We all stand in a circle and we toss a ball to each other and say our name and all the people who have had the ball tossed to them. It gets fun when students start to forget names. They all start out being self-conscious but end up laughing and smiling.

Another way to build a community is during share time. I have students write in their notebooks as soon as they come into the classroom as a warm-up, starter activity that I call Write Nows. These Write Nows are projected up on the screen, and students write for 2-5 minutes. After this, I ask students to turn and talk to a neighbor about what they wrote.

Sometimes this writing is a review of the previous day or another activity that goes along with the skill we are learning. Other times it is a prewriting activity that helps break writer’s block .

Write a Letter to your Students

To help students get to know me as a community member, I write a letter to them and they write back to me. This starts the relationship-building between my students and me within the first week, and I conference with the students about their letters. This also gets them into the swing of a writer’s workshop.

My students love this letter-writing activity that I’ve done every year for the past 24 years. It’s a hit every year and establishes the tone and mood of our workshop.

5. Teacher as Writing Mentor

One of the most important components of the writer’s workshop in middle school is you – the writing teacher.

To teach writing well, you should write along with your students. Over the years, I’ve written on transparencies, used a document camera, and filmed myself writing. All of these methods work. Generally, I write along with students during the bell-ringer activity, which I call Write Now, but sometimes I’ve prewritten the Write Now.

Additionally, I show students my various writing projects, both published and unpublished, during daily lessons.

My students have seen this blog, heard my podcasts , listened to me read aloud from stories I’ve written and/or published. My students are the ones who pushed me to publish my first YA books . You’ll be amazed at what you come up with and how this creates a bond with your students that lasts a lifetime.

Also, by completing the writing assignments you assign, you’ll be able to empathize with and anticipate the writer’s struggle with each assignment.

Terms to Know for Writing Workshop

This is not an exhaustive list, but one that will be added to as I find more terms that should be added here.

Activity: the practice of a skill or process, especially when gaining new knowledge

Assignment: a product created by the student after practicing a skill or process that may be revised up until a particular due date

Bell ringer: a beginning of the period activity (I call these Write Nows in my class)

Blended learning environment: in-person LIVE teaching and learning or digital learning with recorded lessons

Conference: a meeting between teacher and student about their writing

Journal write: handwriting in a journal for ideas, bell ringers, collecting information, etc.

Mini-lesson: a short 5-10 minute lesson that teaches either a whole or partial skill or process

Mastery Learning: quizzing students on their conceptual knowledge, giving them different activities based on the results of their quizzes – either reteach or extend – and quizzing again. Revisions can also be mastery-learning pieces.

Mentor texts: well-written, multicultural texts used to demonstrate a literary concept or style

Rubric: a breakdown of the skill into levels of learning – students revise to earn a higher level

Writing Workshop Middle School Pros and Cons

- Builds student relationships with you and each other – lots of SEL

- Easier to differentiate for students than the traditional classroom model

- Grading can be accomplished during conferences

- Students are more engaged and begin to enjoy writing

- They might even enjoy reading more, too

- Mini-lessons are short, sweet and to the point, less prep time for presentations

- Breaking through writer’s block

- Teaching students how to use the technology

- Helping students revise if they don’t have access to technology

- Adapting to technology challenges that arise (switch to writing journals or change Internet browsers)

- Deadlines can be difficult to manage sometimes

As far as time management is concerned – one of the things I am going to stress to my students is the need for getting assignments turned in, even if it’s not perfect. I need to be able to keep them to deadlines. So, this year, I’m going to teach my student’s Parkinson’s Law :

How to start a writer’s workshop for middle school

These are the steps I’m taking this year to start my writer’s workshop, and I’ve used these for quite a few years now. Some steps may be done simultaneously on the same day. There will be future blog posts about each of these steps.

- Create a welcoming classroom space.

- Decide what technology you will be using – hardware and software. If you need help with Canvas LMS, click here .

- Send out your course syllabus with materials students will need for your course.

- Create a course outline based on your school’s curriculum guides or state standards.

- Plan and post your first 2 weeks of lessons and assignments into your online course (if you are using technology in your course).

- Establish classroom expectations and routines.

- Build a classroom community of writers.

- Show students how to navigate your course online.

- Write a letter to your students and have them write back to you as their first assignment.

- Confer with your writers as they are writing their letters and make a list for yourself of things students need to work on with their writing.

- Set up writing journals and begin writing workshop routines.

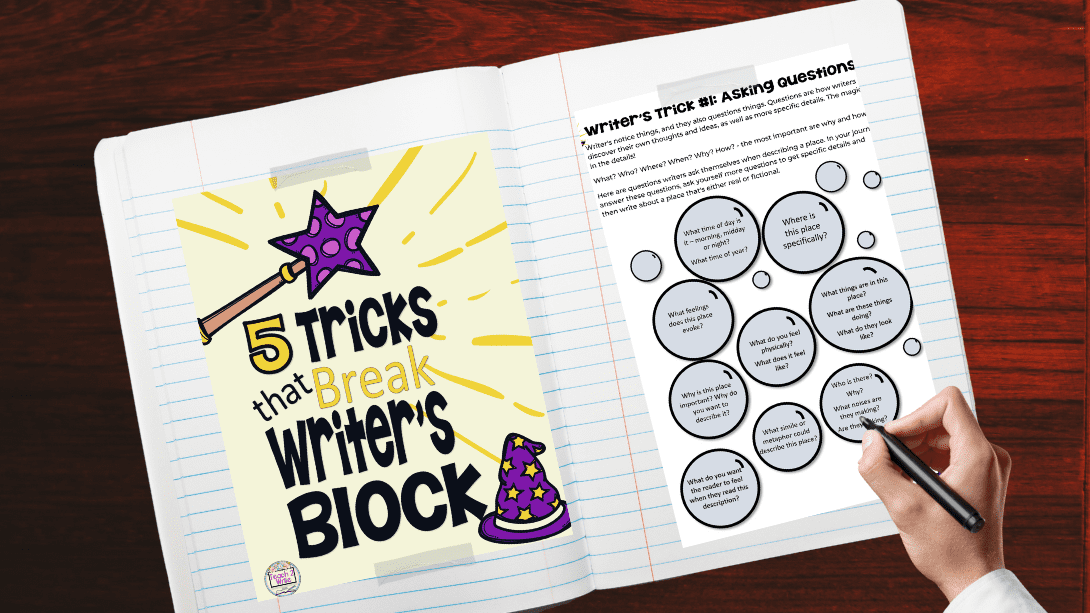

- During mini-lessons, teach the 5 tricks that break writer’s block .

- Students write in journals to gather ideas and begin writing pieces.

- Assign a short writing piece and confer with writers during workshop time.

- Teach ONE revision strategy during a mini-lesson, depending on your curriculum.

- Teach ONE editing strategy during a mini-lesson, depending on your curriculum.

- Allow writers to revise and edit before turning in their first short writing assignment.

- Celebrate your writers with the Author’s Chair presentations.

- Continue writer’s workshop by using daily bell ringers, mini-lessons about writing and reading, sharing, writing/reading workshop, conferencing, and turn and talk.

- Breakaway from the writer’s workshop routine every once in a while to play – escape rooms, read-arounds, watch a movie, celebrate authors, group brainstorm, catching up on overdue assignments.

References for Writing Workshop in Middle School

Atwell, Nancie. In the Middle: A Lifetime of Learning about Writing, Reading, and Adolescence. Heinemann, 2014.

Graves, Donald H. “All Children Can Write.” http://www.ldonline.org/article/6204/

Lane, Barry. After The End: Teaching and Learning Creative Revision. Heinemann, 2015.

Murray, Donald. “The Listening Eye: Reflections on the Writing Conference” https://secure.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Journals/CE/1979/0411-sep1979/CE0411Listening.pdf

Learning materials for Writing Workshop for Middle School

Writing Literary & Informative Analysis Paragraphs

Students struggle with writing a literary analysis , especially in middle school as the text grows more rigorous, and the standards become more demanding. This resource is to help you scaffold your students through the process of writing literary analysis paragraphs for CCSS ELA-Literacy RL.6.1-10 for Reading Literature and RI.6.1-10 Reading Information. These paragraphs can be later grouped together into writing analytical essays.

PEEL, RACE, ACE, and all the other strategies did not work for all of my students all of the time, so that’s why I created these standards-based resources.

These standards-based writing activities for all Common Core Reading Literature and Informational standards help scaffold students through practice and repetition since these activities can be used over and over again with ANY literary reading materials.

Included in these resources:

- step-by-step lesson plans

- poster for literary skills taught in this resource

- rubrics for assessments standards-based

- vocabulary activities and notes standard-based

- graphic organizers that incorporate analysis of the literature and information standard-based

- paragraph frames for students who need extra scaffolding standard-based

- sentence stems to get students started sentence-by-sentence until they master how to write for each standard

- digital version that is Google SlidesTM compatible with all student worksheets

List Making: This resource helps students make 27 different lists of topics they could write about.

Sensory Details: This resource will help you to teach your students to SHOW, not tell. Descriptive writing with a sensory details flipbook and engaging activities that will get your students thinking creatively and writing with style.

Included in this resource are 2 digital files:

- Lesson Plans PDF that includes step-by-step lesson plans, a grading rubric to make grading faster and easier, along with suggestions for what to do after mind mapping.

- Google SlidesTM version of the Student Digital Writer’s Notebook allows students endless amounts of writing simply by duplicating a slide.

Recent Posts

- Text Features Vs Text Structures: How to introduce text structures to your students

- Nurture a Growth Mindset in Your Classroom

- 3 Middle School Writing Workshop Must-Haves

- Writing Strategies for Middle School Students

- Writing Response Paragraphs for Literature

- September 2023

- October 2022

- August 2022

- January 2022

- October 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- September 2019

- February 2019

- October 2018

- February 2018

- Creative Writing

- middle school writing teachers

- Parent Help for Middle School Writers

- writing strategies and techniques for writers

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

Privacy Overview

Writing Expectations

Expectations for all work.

- Heading: name, date, block

- Reasonably neat

- Ready to hand in at beginning of class

Expectations for final-draft quality work (essays, projects, etc.)

- Ready to hand in at beginning of class (printed, stapled)

- No report covers

- Title (centered)

- name, date, block

- 12 pt, easy-to-read font

- 1.5 spaced

- 1” margins

- Indent new paragraphs

- Page numbers

- Name only on title page, not on any pages of paper

Unacceptable errors: Grade 8

- which/witch

- weather/whether

- there/their/they’re

- your/you’re

- No contraction errors: “could of” is incorrect (it’s “could have”)

- No text message or informal spelling: u, 4, gonna, etc.

- “A lot” is two words

- Capitalization: beginning of sentences, proper nouns

- Punctuation: end of sentences, commas

- No magic trick phrasing: “In my paper, I am going to tell you…” “I hope you have enjoyed my paper.”

Unacceptable errors: Grade 7

- Use complete sentences

- Paragraph = Several sentences, all about the same main idea

- Punctuation: end of sentences

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

FREE Book Bracket Template. For March and Beyond!

5 Ways to Help Middle Schoolers Write Beyond the Bare Minimum

Help students go beyond the required word count to create great work.

Teaching writing is not for the faint of heart—especially in middle school! By this age, it’s harder to trick students into thinking writing is fun, and that eagerness to please grown ups may be ancient history. For many students, there is no amount of cajoling, pleading, or threatening that will produce a response other than, “I don’t know what to write.” They seem to want to write the minimum word count and move on to the next task at hand.

It doesn’t have to be this way, though. There are ways to help kids slay the writing dragon while maintaining peace in your kingdom. Er, I mean, classroom.

1. Offer (lots of) word lists and graphic organizers.

This might seem obvious because we all know these supports make writing more accessible for students. But I’ve been in the classroom, and I know they aren’t used often enough. We need to do this as teachers, though. It’s our job to provide students with a battle plan (because writing is a battle for many kids). There are so many graphic organizers out there, and I recommend trying a few different ones to see what your students like. You also want to make word lists easily accessible. Don’t focus on big or fancy words. Instead, concentrate on offering alternatives to “dead” words like very, a lot, great, etc.

2. Embrace mentor texts.

This is a great way to spur reluctant writers into action because they aren’t starting with a blank slate. Mentor texts are a student’s armor as they attempt more sophisticated compositions, protecting students by giving them a guide to good writing while still requiring them to be creative and use their own words. Over the years I’ve used many mentor texts. One of my favorites is the first vignette from The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros. The vignette holds the same title as the book itself, and it describes the different places the main character has lived in her life. Students can model their own writing after Cisneros’ vignette by describing the places they have lived and the people they’ve known in those places along the way.

3. Let the diversity of authors inspire your students.

4. incorporate current events..

Middle school students have lots of opinions, but they often don’t watch the news or get their information from reliable sources. Providing students with a current event article, pairing it with a video, (or song lyrics, or poem, or chapter from a novel or memoir) and then asking them to put down their thoughts really inspire some passionate writing. Current events texts can be paired with nearly any fictitious work to build students’ background knowledge, widen their world view, and yes, nudge them into broadening and deepening their writing lives.

5. Let them choose the adventure.

I know it’s not always possible to let students choose the type of writing they want to do, but when possible, it’s important to let them express themselves. This will definitely help them take ownership of their own work. Think about offering a menu so they have choices—for instance give options such as writing a poem, a chapter in their own memoir, song lyrics, a fictional short story, or even an informative nonfiction article using research (for your fact-loving students!). This will help students see that there are many ways to relate what they know.

Writing is hard, and for many students it can seem like an impossible feat that will never be conquered. However, having your own teacher arsenal of writing strategies and tools will help you lead your mighty army of authors to victory, time and time again. Now, go forth, and WRITE!

You Might Also Like

Teaching High School English Is the Best Gig Ever. Here’s Why.

IYKYK 📚 Continue Reading

Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Nourishing My Scholar

Exceptional Middle School Writing Curriculum

August 16, 2020 by Erin Vincent Leave a Comment

Are you looking for a middle school writing curriculum ? Do you need something flexible, and gentle, yet thorough? Perhaps you have a reluctant writer or a young writer that has trouble putting their thoughts on paper. WriteShop takes the overwhelm out of the writing process. It’s a comprehensive writing curriculum that walks the homeschool parent and their student through the skills needed to find their kiddos writing voice.

*Disclosure: I was compensated for my time in exchange for an honest review of WriteShop I and II Bundle plus the Online Video Course . I was not required to write a positive review. As always, all thoughts and opinions are my own. I only choose to share resources that I would use with my own family and those that I believe other families will enjoy and benefit from.

We’ve used other writing curriculums in the past. And while I love their philosophy and lifestyle, my son was needing something more. He needed a writing curriculum with more structure that would help him with the building blocks of writing while developing his writer’s voice.

I, the parent, needed more direction on HOW to TEACH my son to write papers and essays. He needed more than copy work and dictation.

My son is a multi-sensory learner. But most middle school writing curriculum are boring and only focus on pencil and paper. I spent all spring searching for a better alternative. I kept coming back to WriteShop I for its ability to help students to build strong writing foundations while also allowing the student to go at their own pace. Then there are the videos that WriteShop offers. Not the boring and dry videos I’d seen across the internet, but visually stimulating and creative videos that would hold my son’s attention.

I was so happy to get my hands on WriteShop I and II Bundle plus the Online Video Course !

Middle School Writing Curriculum

What is WriteShop? WriteShop I is a writing curriculum that offers detailed step-by-step lessons to help introduce descriptive, expository, narrative, and persuasive compositions and essays. It provides pre-teens and teens with a solid foundation in brainstorming all the way through the final draft stages and builds self-editing skills. It’s also perfect for your older reluctant writers because of its gentle writing approach.

WriteShop was created by a couple of moms whose sons struggled with writing! So, they understand what it’s like to be in the trenches of homeschooling reluctant writers.

These moms found that most writing programs were great about encouraging kids to “get their ideas onto paper,” but they often failed to help parents teach, guide, and evaluate in a simple way.

With WriteShop , you’ll discover lessons that provide:

- Prewriting games to stimulate creativity.

- A way to introduce and help students develop new skills.

- Creative, varied writing exercises with clearly defined expectations.

- Incremental lessons that built upon previously learned material.

- Writing checklists to help students edit their own work.

- A simple evaluation tool to help us grade final drafts objectively

https://www.instagram.com/p/CCgaVmYpQL-/

Why I Love WriteShop I Homeschool Writing Curriculum

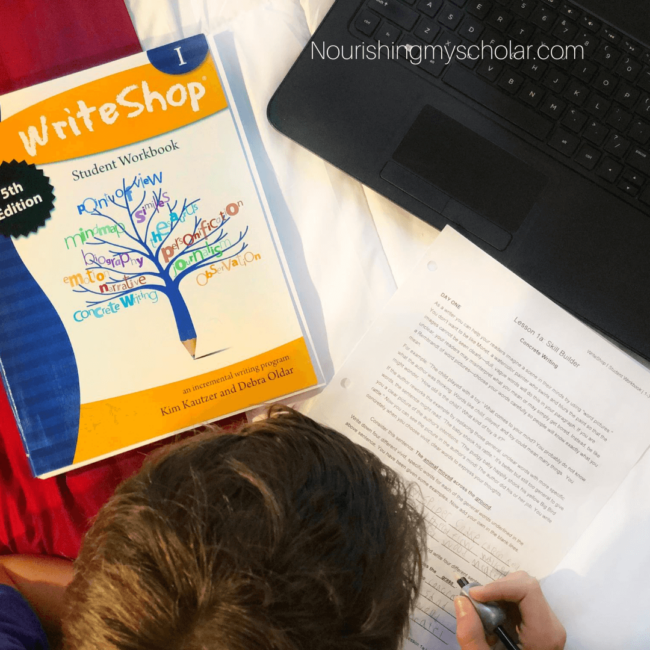

WriteShop I is perfect for most children ages 12-16 in middle and early high school. The student workbook contains the meat of each lesson written directly to the student.

WriteShop I focuses on stylistic techniques, vocabulary development, active voice, and sentence variation in a fully faith neutral way. Writing skills are taught in shorter writing assignments. I love that students are working on the building blocks of more mature sentences and middle school paragraph writing while teaching me how to be my child’s writing coach. WriteShop literally teaches students how to describe an object, write a sentence, a paragraph, and connect it all together! This lays the foundation for all future compositions, essays, and reports.

Benefits of Using WriteShop I for Middle School Writing Curriculum

The beauty of the program is its adaptability! Whether your child is advanced, reluctant, or struggling with learning difficulties WriteShop can meet your kiddo’s needs. Lessons are parsed out in bite-size chunks. My son loves that each day’s assignments aren’t overwhelming. In addition, most compositions are rarely longer than one paragraph. My son also does well with the multisensory aspects of the lessons, whether it’s a game or a fun prewriting activity. This means that WriteShop is especially good for reluctant writers, special needs writers, and parents who need extra support with teaching writing .

Adapting Writing Lessons to Fit Your Middle Schooler’s Needs

With WriteShop I you can use a 1-week schedule, 2-week schedule, or break it up even further for teens with learning disabilities and create a schedule that fits their needs. That means you can plan for it to take 1 semester to 2 years depending on the way you do it. It’s all about doing what works best for your individual kid.

You can go as slowly as you need to, and the assignments are not long, lengthy papers, but focused on building strong paragraphs. New skills are introduced slowly, so I don’t have to worry about my son having to master everything at once.

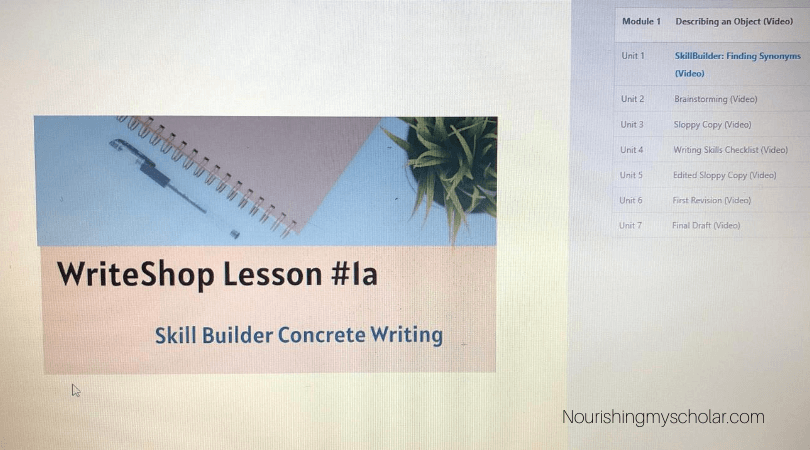

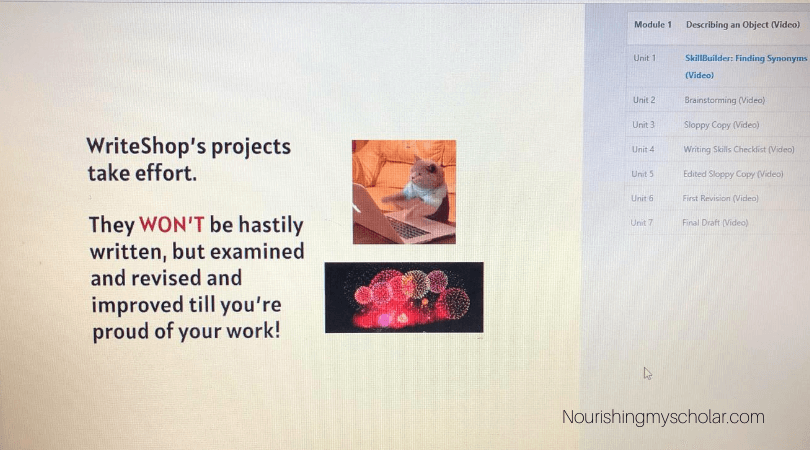

WriteShop Online Video Course

WriteShop also offers an online video course for their WriteShop I & II curriculum.

Play With Education provides this additional support for writers and their parents with the platform for these videos.

WriteShop Online Videos Take One Thing Off Moms Plate

Each 10- to 15-minute video introduces students to the key points of WriteShop’s lesson in a clear and easy-to-understand way.

The WriteShop online video segments cover all the teaching points of each lesson. The videos cover it so fully that I was able to hand the bulk of the teaching over to the videos. I didn’t have to add anything. Though I still watched the videos with my son initially. I also helped my son with his paper, but the beauty of the videos was that I didn’t have to teach the lesson. The videos do this for me!

The video course works beautifully alongside the Teachers Manual. I highly recommend adding the video course as part of your WriteShop I writing curriculum.

WriteShop Middle School Writing Curriculum Resources

WriteShop I does have some grammar mingled into it but it is not enough to be considered a full credit. Because my son does so well with a multi-sensory approach, we paired Winston Grammar program with WriteShop 1.

WriteShop offers homeschool writing curriculum for all grades from K to 12. The Placement Quiz will help you find the best fit.

You can learn more about WriteShop’s Scope and Sequence as well as see Sample Lessons here . Subscribe to WriteShop and get instant access to your FREE gift ! WriteShop offers so many wonderful resources to help you help your child succeed in writing.

WriteShop Homeschool Writing Curriculum

If you’re looking for a most cost-effective alternative to the hard copy curriculum, don’t want to deal with hefty postage costs, or long shipping delays then be sure to check out the E-book Digital version to all of WriteShop’s curriculum.

You can browse the Digital Bundles here .

WriteShop includes everything you need for a successful year of writing for your homeschool. We’ve been using it for several months and I already see a HUGE difference in my son’s approach to writing. He’s becoming more independent and self-motivated while getting his brilliant words and phrases out onto paper! I’m so pleased with the growth we’ve both experienced on this writing journey.

You may also enjoy:

- Are You Unexpectedly Homeschooling

- 10 Things You Need to Know to Homeschool

- U.S. Elections Process for Kids

- Free Typing Games for Kids

About Erin Vincent

Erin is a writer, blogger, and homeschooler to two intense kids. She loves nature, farm life, good books, knitting, new pens, and hot coffee. Erin is a contributing writer for Weird Unsocialized Homeschoolers. Her work has also been featured on Simple Homeschool and Book Shark.

Reader Interactions

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Home » Tips for Teachers » Use These 22 Classroom Rules for Middle School To Help Your Students Learn and Succeed

Use These 22 Classroom Rules for Middle School To Help Your Students Learn and Succeed

Teaching middle school can be……well, interesting, especially when it comes to enforcing middle school classroom rules. Middle schoolers can be a lot of fun. They’re at the age that you can joke around and also start having some serious conversations.

However, middle schoolers can also be challenging to teach at times. They like to socialize and may not always be so interested in what you’re trying to teach them.

When I made the switch from elementary school to middle school, I had a huge learning curve. A lot of the strategies I used with younger students didn’t work anymore.

I had to re-vamp my approach to classroom management and re-write my classroom rules to make them work for the pre-teens and young teenagers I was now responsible for.

These 8th Grade @kmsknights not only understood the assignment, they created it! They wanted a fun way to establish and remember their classroom rules and it appears they succeeded! Kenwood Middle School is where The Best choose to be! pic.twitter.com/JQySih9TeM — Jeremiah Davis (@KMS_Davis) September 10, 2022

Finding the right rules that made a difference took some trial and error. Continue reading, I’d love to share what I learned through research and through working with my students. I’ll share:

- 22 classroom rules for middle school that you can use with your students →

- The best way to teach classroom rules to middle school students →

Otherwise, you can watch the video below. It contains a retelling of the article.

22 Classroom Rules For Middle School