Essay on Financial Literacy for Students and Children

Importance of financial literacy, an introduction to financial literacy.

We go to schools, colleges, universities to complete our educated and start earning our livelihood. We take up jobs, practise professions or start our own businesses so that we can earn money to make our living. But which of these institutions make us capable of managing our own hard-earned money? Probably a very few of them.

Our ability to effectively manage our money by drawing systematic budgets, paying off our debts, making buying and selling decisions and ultimately becoming financially self-sustainable is known as financial literacy.

Financial literacy is knowing the basic financial management principles and applying them in our day-to-day life.

Financial Literacy – What does it Involve?

From simple practices like keeping a track of our expenses and understanding the need to spend money if we like a product to striking a balance between the value of time saved and money lost, paying our taxes and filing of tax returns, finalizing the property deals, etc – everything becomes a part of financial literacy.

Get the huge list of 500+ Essay Topics here

As human beings, we are not expected to know the nitty-gritty of financial management. But managing our own money in a way that it does not affect us and our family in a negative way is important. We certainly do not want to end up having a day with no money at hand and hunger in our stomach.

Why is Financial Literacy so Important?

Financial literacy can enable an individual to build up a budgetary guide to distinguish what he buys, what he spends, and what he owes. This subject additionally influences entrepreneurs, who incredibly add to financial development and strength of our economy.

Financial literacy helps people in becoming independent and self-sufficient. It empowers you with basic knowledge of investment options, financial markets, capital budgeting, etc.

Understanding your money mitigates the danger of facing a fraud-like situation. A few strategies are anything but difficult to accept, particularly when they’re originating from somebody who is by all accounts learned and planned. Basic knowledge of financial literacy will help people with foreseeing the risks and argue/justify with anyone learned and well-informed.

What should you read on / get informed about in Financial Literacy?

- Budgeting and techniques of budgeting

- Direct and indirect taxation system

- Direct tax slabs

- Income and expense tracking

- Loans and debt – EMI management

- Interest rate systems: fixed versus floating

- Business and organisational transaction studies

- Elementary Book-keeping and Accountancy

- Cash in-flow and out-flow Statements

- Investment & personal finance management

- Asset management:

- Business negotiation skills and techniques

- Make or buy decision-making

- Financial markets

- Capital structure – owner’s funds and borrowed funds

- Fundamentals of Risk Management

- Microeconomics and Macroeconomics fundamentals

While there are various media to learn about financial literacy, we recommend that you join a short-term, weekend programme which helps you get financially literate.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

- Conference key note

- Open access

- Published: 24 January 2019

Financial literacy and the need for financial education: evidence and implications

- Annamaria Lusardi 1

Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics volume 155 , Article number: 1 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

385k Accesses

270 Citations

187 Altmetric

Metrics details

1 Introduction

Throughout their lifetime, individuals today are more responsible for their personal finances than ever before. With life expectancies rising, pension and social welfare systems are being strained. In many countries, employer-sponsored defined benefit (DB) pension plans are swiftly giving way to private defined contribution (DC) plans, shifting the responsibility for retirement saving and investing from employers to employees. Individuals have also experienced changes in labor markets. Skills are becoming more critical, leading to divergence in wages between those with a college education, or higher, and those with lower levels of education. Simultaneously, financial markets are rapidly changing, with developments in technology and new and more complex financial products. From student loans to mortgages, credit cards, mutual funds, and annuities, the range of financial products people have to choose from is very different from what it was in the past, and decisions relating to these financial products have implications for individual well-being. Moreover, the exponential growth in financial technology (fintech) is revolutionizing the way people make payments, decide about their financial investments, and seek financial advice. In this context, it is important to understand how financially knowledgeable people are and to what extent their knowledge of finance affects their financial decision-making.

An essential indicator of people’s ability to make financial decisions is their level of financial literacy. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) aptly defines financial literacy as not only the knowledge and understanding of financial concepts and risks but also the skills, motivation, and confidence to apply such knowledge and understanding in order to make effective decisions across a range of financial contexts, to improve the financial well-being of individuals and society, and to enable participation in economic life. Thus, financial literacy refers to both knowledge and financial behavior, and this paper will analyze research on both topics.

As I describe in more detail below, findings around the world are sobering. Financial literacy is low even in advanced economies with well-developed financial markets. On average, about one third of the global population has familiarity with the basic concepts that underlie everyday financial decisions (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011c ). The average hides gaping vulnerabilities of certain population subgroups and even lower knowledge of specific financial topics. Furthermore, there is evidence of a lack of confidence, particularly among women, and this has implications for how people approach and make financial decisions. In the following sections, I describe how we measure financial literacy, the levels of literacy we find around the world, the implications of those findings for financial decision-making, and how we can improve financial literacy.

2 How financially literate are people?

2.1 measuring financial literacy: the big three.

In the context of rapid changes and constant developments in the financial sector and the broader economy, it is important to understand whether people are equipped to effectively navigate the maze of financial decisions that they face every day. To provide the tools for better financial decision-making, one must assess not only what people know but also what they need to know, and then evaluate the gap between those things. There are a few fundamental concepts at the basis of most financial decision-making. These concepts are universal, applying to every context and economic environment. Three such concepts are (1) numeracy as it relates to the capacity to do interest rate calculations and understand interest compounding; (2) understanding of inflation; and (3) understanding of risk diversification. Translating these concepts into easily measured financial literacy metrics is difficult, but Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2008 , 2011b , 2011c ) have designed a standard set of questions around these concepts and implemented them in numerous surveys in the USA and around the world.

Four principles informed the design of these questions, as described in detail by Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2014 ). The first is simplicity : the questions should measure knowledge of the building blocks fundamental to decision-making in an intertemporal setting. The second is relevance : the questions should relate to concepts pertinent to peoples’ day-to-day financial decisions over the life cycle; moreover, they must capture general rather than context-specific ideas. Third is brevity : the number of questions must be few enough to secure widespread adoption; and fourth is capacity to differentiate , meaning that questions should differentiate financial knowledge in such a way as to permit comparisons across people. Each of these principles is important in the context of face-to-face, telephone, and online surveys.

Three basic questions (since dubbed the “Big Three”) to measure financial literacy have been fielded in many surveys in the USA, including the National Financial Capability Study (NFCS) and, more recently, the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), and in many national surveys around the world. They have also become the standard way to measure financial literacy in surveys used by the private sector. For example, the Aegon Center for Longevity and Retirement included the Big Three questions in the 2018 Aegon Retirement Readiness Survey, covering around 16,000 people in 15 countries. Both ING and Allianz, but also investment funds, and pension funds have used the Big Three to measure financial literacy. The exact wording of the questions is provided in Table 1 .

2.2 Cross-country comparison

The first examination of financial literacy using the Big Three was possible due to a special module on financial literacy and retirement planning that Lusardi and Mitchell designed for the 2004 Health and Retirement Study (HRS), which is a survey of Americans over age 50. Astonishingly, the data showed that only half of older Americans—who presumably had made many financial decisions in their lives—could answer the two basic questions measuring understanding of interest rates and inflation (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011b ). And just one third demonstrated understanding of these two concepts and answered the third question, measuring understanding of risk diversification, correctly. It is sobering that recent US surveys, such as the 2015 NFCS, the 2016 SCF, and the 2017 Survey of Household Economics and Financial Decisionmaking (SHED), show that financial knowledge has remained stubbornly low over time.

Over time, the Big Three have been added to other national surveys across countries and Lusardi and Mitchell have coordinated a project called Financial Literacy around the World (FLat World), which is an international comparison of financial literacy (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011c ).

Findings from the FLat World project, which so far includes data from 15 countries, including Switzerland, highlight the urgent need to improve financial literacy (see Table 2 ). Across countries, financial literacy is at a crisis level, with the average rate of financial literacy, as measured by those answering correctly all three questions, at around 30%. Moreover, only around 50% of respondents in most countries are able to correctly answer the two financial literacy questions on interest rates and inflation correctly. A noteworthy point is that most countries included in the FLat World project have well-developed financial markets, which further highlights the cause for alarm over the demonstrated lack of the financial literacy. The fact that levels of financial literacy are so similar across countries with varying levels of economic development—indicating that in terms of financial knowledge, the world is indeed flat —shows that income levels or ubiquity of complex financial products do not by themselves equate to a more financially literate population.

Other noteworthy findings emerge in Table 2 . For instance, as expected, understanding of the effects of inflation (i.e., of real versus nominal values) among survey respondents is low in countries that have experienced deflation rather than inflation: in Japan, understanding of inflation is at 59%; in other countries, such as Germany, it is at 78% and, in the Netherlands, it is at 77%. Across countries, individuals have the lowest level of knowledge around the concept of risk, and the percentage of correct answers is particularly low when looking at knowledge of risk diversification. Here, we note the prevalence of “do not know” answers. While “do not know” responses hover around 15% on the topic of interest rates and 18% for inflation, about 30% of respondents—in some countries even more—are likely to respond “do not know” to the risk diversification question. In Switzerland, 74% answered the risk diversification question correctly and 13% reported not knowing the answer (compared to 3% and 4% responding “do not know” for the interest rates and inflation questions, respectively).

These findings are supported by many other surveys. For example, the 2014 Standard & Poor’s Global Financial Literacy Survey shows that, around the world, people know the least about risk and risk diversification (Klapper, Lusardi, and Van Oudheusden, 2015 ). Similarly, results from the 2016 Allianz survey, which collected evidence from ten European countries on money, financial literacy, and risk in the digital age, show very low-risk literacy in all countries covered by the survey. In Austria, Germany, and Switzerland, which are the three top-performing nations in term of financial knowledge, less than 20% of respondents can answer three questions related to knowledge of risk and risk diversification (Allianz, 2017 ).

Other surveys show that the findings about financial literacy correlate in an expected way with other data. For example, performance on the mathematics and science sections of the OECD Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) correlates with performance on the Big Three and, specifically, on the question relating to interest rates. Similarly, respondents in Sweden, which has experienced pension privatization, performed better on the risk diversification question (at 68%), than did respondents in Russia and East Germany, where people have had less exposure to the stock market. For researchers studying financial knowledge and its effects, these findings hint to the fact that financial literacy could be the result of choice and not an exogenous variable.

To summarize, financial literacy is low across the world and higher national income levels do not equate to a more financially literate population. The design of the Big Three questions enables a global comparison and allows for a deeper understanding of financial literacy. This enhances the measure’s utility because it helps to identify general and specific vulnerabilities across countries and within population subgroups, as will be explained in the next section.

2.3 Who knows the least?

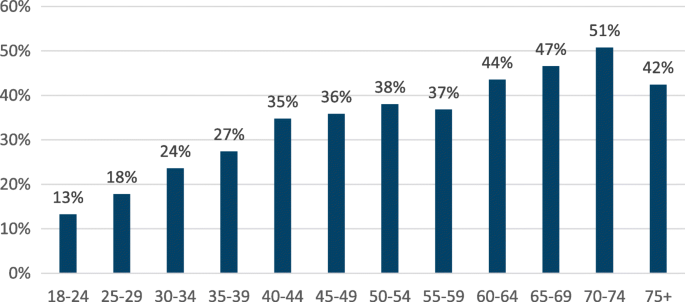

Low financial literacy on average is exacerbated by patterns of vulnerability among specific population subgroups. For instance, as reported in Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2014 ), even though educational attainment is positively correlated with financial literacy, it is not sufficient. Even well-educated people are not necessarily savvy about money. Financial literacy is also low among the young. In the USA, less than 30% of respondents can correctly answer the Big Three by age 40, even though many consequential financial decisions are made well before that age (see Fig. 1 ). Similarly, in Switzerland, only 45% of those aged 35 or younger are able to correctly answer the Big Three questions. Footnote 1 And if people may learn from making financial decisions, that learning seems limited. As shown in Fig. 1 , many older individuals, who have already made decisions, cannot answer three basic financial literacy questions.

Financial literacy across age in the USA. This figure shows the percentage of respondents who answered correctly all Big Three questions by age group (year 2015). Source: 2015 US National Financial Capability Study

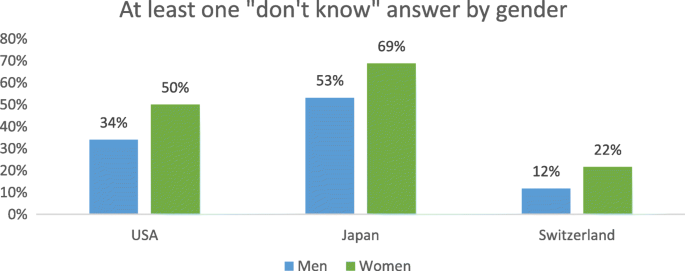

A gender gap in financial literacy is also present across countries. Women are less likely than men to answer questions correctly. The gap is present not only on the overall scale but also within each topic, across countries of different income levels, and at different ages. Women are also disproportionately more likely to indicate that they do not know the answer to specific questions (Fig. 2 ), highlighting overconfidence among men and awareness of lack of knowledge among women. Even in Finland, which is a relatively equal society in terms of gender, 44% of men compared to 27% of women answer all three questions correctly and 18% of women give at least one “do not know” response versus less than 10% of men (Kalmi and Ruuskanen, 2017 ). These figures further reflect the universality of the Big Three questions. As reported in Fig. 2 , “do not know” responses among women are prevalent not only in European countries, for example, Switzerland, but also in North America (represented in the figure by the USA, though similar findings are reported in Canada) and in Asia (represented in the figure by Japan). Those interested in learning more about the differences in financial literacy across demographics and other characteristics can consult Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2011c , 2014 ).

Gender differences in the responses to the Big Three questions. Sources: USA—Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011c ; Japan—Sekita, 2011 ; Switzerland—Brown and Graf, 2013

3 Does financial literacy matter?

A growing number of financial instruments have gained importance, including alternative financial services such as payday loans, pawnshops, and rent to own stores that charge very high interest rates. Simultaneously, in the changing economic landscape, people are increasingly responsible for personal financial planning and for investing and spending their resources throughout their lifetime. We have witnessed changes not only in the asset side of household balance sheets but also in the liability side. For example, in the USA, many people arrive close to retirement carrying a lot more debt than previous generations did (Lusardi, Mitchell, and Oggero, 2018 ). Overall, individuals are making substantially more financial decisions over their lifetime, living longer, and gaining access to a range of new financial products. These trends, combined with low financial literacy levels around the world and, particularly, among vulnerable population groups, indicate that elevating financial literacy must become a priority for policy makers.

There is ample evidence of the impact of financial literacy on people’s decisions and financial behavior. For example, financial literacy has been proven to affect both saving and investment behavior and debt management and borrowing practices. Empirically, financially savvy people are more likely to accumulate wealth (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014 ). There are several explanations for why higher financial literacy translates into greater wealth. Several studies have documented that those who have higher financial literacy are more likely to plan for retirement, probably because they are more likely to appreciate the power of interest compounding and are better able to do calculations. According to the findings of the FLat World project, answering one additional financial question correctly is associated with a 3–4 percentage point greater probability of planning for retirement; this finding is seen in Germany, the USA, Japan, and Sweden. Financial literacy is found to have the strongest impact in the Netherlands, where knowing the right answer to one additional financial literacy question is associated with a 10 percentage point higher probability of planning (Mitchell and Lusardi, 2015 ). Empirically, planning is a very strong predictor of wealth; those who plan arrive close to retirement with two to three times the amount of wealth as those who do not plan (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011b ).

Financial literacy is also associated with higher returns on investments and investment in more complex assets, such as stocks, which normally offer higher rates of return. This finding has important consequences for wealth; according to the simulation by Lusardi, Michaud, and Mitchell ( 2017 ), in the context of a life-cycle model of saving with many sources of uncertainty, from 30 to 40% of US retirement wealth inequality can be accounted for by differences in financial knowledge. These results show that financial literacy is not a sideshow, but it plays a critical role in saving and wealth accumulation.

Financial literacy is also strongly correlated with a greater ability to cope with emergency expenses and weather income shocks. Those who are financially literate are more likely to report that they can come up with $2000 in 30 days or that they are able to cover an emergency expense of $400 with cash or savings (Hasler, Lusardi, and Oggero, 2018 ).

With regard to debt behavior, those who are more financially literate are less likely to have credit card debt and more likely to pay the full balance of their credit card each month rather than just paying the minimum due (Lusardi and Tufano, 2009 , 2015 ). Individuals with higher financial literacy levels also are more likely to refinance their mortgages when it makes sense to do so, tend not to borrow against their 401(k) plans, and are less likely to use high-cost borrowing methods, e.g., payday loans, pawn shops, auto title loans, and refund anticipation loans (Lusardi and de Bassa Scheresberg, 2013 ).

Several studies have documented poor debt behavior and its link to financial literacy. Moore ( 2003 ) reported that the least financially literate are also more likely to have costly mortgages. Lusardi and Tufano ( 2015 ) showed that the least financially savvy incurred high transaction costs, paying higher fees and using high-cost borrowing methods. In their study, the less knowledgeable also reported excessive debt loads and an inability to judge their debt positions. Similarly, Mottola ( 2013 ) found that those with low financial literacy were more likely to engage in costly credit card behavior, and Utkus and Young ( 2011 ) concluded that the least literate were more likely to borrow against their 401(k) and pension accounts.

Young people also struggle with debt, in particular with student loans. According to Lusardi, de Bassa Scheresberg, and Oggero ( 2016 ), Millennials know little about their student loans and many do not attempt to calculate the payment amounts that will later be associated with the loans they take. When asked what they would do, if given the chance to revisit their student loan borrowing decisions, about half of Millennials indicate that they would make a different decision.

Finally, a recent report on Millennials in the USA (18- to 34-year-olds) noted the impact of financial technology (fintech) on the financial behavior of young individuals. New and rapidly expanding mobile payment options have made transactions easier, quicker, and more convenient. The average user of mobile payments apps and technology in the USA is a high-income, well-educated male who works full time and is likely to belong to an ethnic minority group. Overall, users of mobile payments are busy individuals who are financially active (holding more assets and incurring more debt). However, mobile payment users display expensive financial behaviors, such as spending more than they earn, using alternative financial services, and occasionally overdrawing their checking accounts. Additionally, mobile payment users display lower levels of financial literacy (Lusardi, de Bassa Scheresberg, and Avery, 2018 ). The rapid growth in fintech around the world juxtaposed with expensive financial behavior means that more attention must be paid to the impact of mobile payment use on financial behavior. Fintech is not a substitute for financial literacy.

4 The way forward for financial literacy and what works

Overall, financial literacy affects everything from day-to-day to long-term financial decisions, and this has implications for both individuals and society. Low levels of financial literacy across countries are correlated with ineffective spending and financial planning, and expensive borrowing and debt management. These low levels of financial literacy worldwide and their widespread implications necessitate urgent efforts. Results from various surveys and research show that the Big Three questions are useful not only in assessing aggregate financial literacy but also in identifying vulnerable population subgroups and areas of financial decision-making that need improvement. Thus, these findings are relevant for policy makers and practitioners. Financial illiteracy has implications not only for the decisions that people make for themselves but also for society. The rapid spread of mobile payment technology and alternative financial services combined with lack of financial literacy can exacerbate wealth inequality.

To be effective, financial literacy initiatives need to be large and scalable. Schools, workplaces, and community platforms provide unique opportunities to deliver financial education to large and often diverse segments of the population. Furthermore, stark vulnerabilities across countries make it clear that specific subgroups, such as women and young people, are ideal targets for financial literacy programs. Given women’s awareness of their lack of financial knowledge, as indicated via their “do not know” responses to the Big Three questions, they are likely to be more receptive to financial education.

The near-crisis levels of financial illiteracy, the adverse impact that it has on financial behavior, and the vulnerabilities of certain groups speak of the need for and importance of financial education. Financial education is a crucial foundation for raising financial literacy and informing the next generations of consumers, workers, and citizens. Many countries have seen efforts in recent years to implement and provide financial education in schools, colleges, and workplaces. However, the continuously low levels of financial literacy across the world indicate that a piece of the puzzle is missing. A key lesson is that when it comes to providing financial education, one size does not fit all. In addition to the potential for large-scale implementation, the main components of any financial literacy program should be tailored content, targeted at specific audiences. An effective financial education program efficiently identifies the needs of its audience, accurately targets vulnerable groups, has clear objectives, and relies on rigorous evaluation metrics.

Using measures like the Big Three questions, it is imperative to recognize vulnerable groups and their specific needs in program designs. Upon identification, the next step is to incorporate this knowledge into financial education programs and solutions.

School-based education can be transformational by preparing young people for important financial decisions. The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), in both 2012 and 2015, found that, on average, only 10% of 15-year-olds achieved maximum proficiency on a five-point financial literacy scale. As of 2015, about one in five of students did not have even basic financial skills (see OECD, 2017 ). Rigorous financial education programs, coupled with teacher training and high school financial education requirements, are found to be correlated with fewer defaults and higher credit scores among young adults in the USA (Urban, Schmeiser, Collins, and Brown, 2018 ). It is important to target students and young adults in schools and colleges to provide them with the necessary tools to make sound financial decisions as they graduate and take on responsibilities, such as buying cars and houses, or starting retirement accounts. Given the rising cost of education and student loan debt and the need of young people to start contributing as early as possible to retirement accounts, the importance of financial education in school cannot be overstated.

There are three compelling reasons for having financial education in school. First, it is important to expose young people to the basic concepts underlying financial decision-making before they make important and consequential financial decisions. As noted in Fig. 1 , financial literacy is very low among the young and it does not seem to increase a lot with age/generations. Second, school provides access to financial literacy to groups who may not be exposed to it (or may not be equally exposed to it), for example, women. Third, it is important to reduce the costs of acquiring financial literacy, if we want to promote higher financial literacy both among individuals and among society.

There are compelling reasons to have personal finance courses in college as well. In the same way in which colleges and university offer courses in corporate finance to teach how to manage the finances of firms, so today individuals need the knowledge to manage their own finances over the lifetime, which in present discounted value often amount to large values and are made larger by private pension accounts.

Financial education can also be efficiently provided in workplaces. An effective financial education program targeted to adults recognizes the socioeconomic context of employees and offers interventions tailored to their specific needs. A case study conducted in 2013 with employees of the US Federal Reserve System showed that completing a financial literacy learning module led to significant changes in retirement planning behavior and better-performing investment portfolios (Clark, Lusardi, and Mitchell, 2017 ). It is also important to note the delivery method of these programs, especially when targeted to adults. For instance, video formats have a significantly higher impact on financial behavior than simple narratives, and instruction is most effective when it is kept brief and relevant (Heinberg et al., 2014 ).

The Big Three also show that it is particularly important to make people familiar with the concepts of risk and risk diversification. Programs devoted to teaching risk via, for example, visual tools have shown great promise (Lusardi et al., 2017 ). The complexity of some of these concepts and the costs of providing education in the workplace, coupled with the fact that many older individuals may not work or work in firms that do not offer such education, provide other reasons why financial education in school is so important.

Finally, it is important to provide financial education in the community, in places where people go to learn. A recent example is the International Federation of Finance Museums, an innovative global collaboration that promotes financial knowledge through museum exhibits and the exchange of resources. Museums can be places where to provide financial literacy both among the young and the old.

There are a variety of other ways in which financial education can be offered and also targeted to specific groups. However, there are few evaluations of the effectiveness of such initiatives and this is an area where more research is urgently needed, given the statistics reported in the first part of this paper.

5 Concluding remarks

The lack of financial literacy, even in some of the world’s most well-developed financial markets, is of acute concern and needs immediate attention. The Big Three questions that were designed to measure financial literacy go a long way in identifying aggregate differences in financial knowledge and highlighting vulnerabilities within populations and across topics of interest, thereby facilitating the development of tailored programs. Many such programs to provide financial education in schools and colleges, workplaces, and the larger community have taken existing evidence into account to create rigorous solutions. It is important to continue making strides in promoting financial literacy, by achieving scale and efficiency in future programs as well.

In August 2017, I was appointed Director of the Italian Financial Education Committee, tasked with designing and implementing the national strategy for financial literacy. I will be able to apply my research to policy and program initiatives in Italy to promote financial literacy: it is an essential skill in the twenty-first century, one that individuals need if they are to thrive economically in today’s society. As the research discussed in this paper well documents, financial literacy is like a global passport that allows individuals to make the most of the plethora of financial products available in the market and to make sound financial decisions. Financial literacy should be seen as a fundamental right and universal need, rather than the privilege of the relatively few consumers who have special access to financial knowledge or financial advice. In today’s world, financial literacy should be considered as important as basic literacy, i.e., the ability to read and write. Without it, individuals and societies cannot reach their full potential.

See Brown and Graf ( 2013 ).

Abbreviations

Defined benefit (refers to pension plan)

Defined contribution (refers to pension plan)

Financial Literacy around the World

National Financial Capability Study

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Programme for International Student Assessment

Survey of Consumer Finances

Survey of Household Economics and Financial Decisionmaking

Aegon Center for Longevity and Retirement. (2018). The New Social Contract: a blueprint for retirement in the 21st century. The Aegon Retirement Readiness Survey 2018. Retrieved from https://www.aegon.com/en/Home/Research/aegon-retirement-readiness-survey-2018/ . Accessed 1 June 2018.

Agnew, J., Bateman, H., & Thorp, S. (2013). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Australia. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Allianz (2017). When will the penny drop? Money, financial literacy and risk in the digital age. Retrieved from http://gflec.org/initiatives/money-finlit-risk/ . Accessed 1 June 2018.

Almenberg, J., & Säve-Söderbergh, J. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Sweden. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 585–598.

Article Google Scholar

Arrondel, L., Debbich, M., & Savignac, F. (2013). Financial literacy and financial planning in France. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Beckmann, E. (2013). Financial literacy and household savings in Romania. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Boisclair, D., Lusardi, A., & Michaud, P. C. (2017). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Canada. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 16 (3), 277–296.

Brown, M., & Graf, R. (2013). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Switzerland. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Bucher-Koenen, T., & Lusardi, A. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Germany. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 565–584.

Clark, R., Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2017). Employee financial literacy and retirement plan behavior: a case study. Economic Inquiry, 55 (1), 248–259.

Crossan, D., Feslier, D., & Hurnard, R. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in New Zealand. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 619–635.

Fornero, E., & Monticone, C. (2011). Financial literacy and pension plan participation in Italy. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 547–564.

Hasler, A., Lusardi, A., and Oggero, N. (2018). Financial fragility in the US: evidence and implications. GFLEC working paper n. 2018–1.

Heinberg, A., Hung, A., Kapteyn, A., Lusardi, A., Samek, A. S., & Yoong, J. (2014). Five steps to planning success: experimental evidence from US households. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 30 (4), 697–724.

Kalmi, P., & Ruuskanen, O. P. (2017). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Finland. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 17 (3), 1–28.

Klapper, L., Lusardi, A., & Van Oudheusden, P. (2015). Financial literacy around the world. In Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services Global Financial Literacy Survey (GFLEC working paper).

Google Scholar

Klapper, L., & Panos, G. A. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning: The Russian case. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 599–618.

Lusardi, A., & de Bassa Scheresberg, C. (2013). Financial literacy and high-cost borrowing in the United States, NBER Working Paper n. 18969, April .

Book Google Scholar

Lusardi, A., de Bassa Scheresberg, C., and Avery, M. 2018. Millennial mobile payment users: a look into their personal finances and financial behaviors. GFLEC working paper.

Lusardi, A., de Bassa Scheresberg, C., & Oggero, N. (2016). Student loan debt in the US: an analysis of the 2015 NFCS Data, GFLEC Policy Brief, November .

Lusardi, A., Michaud, P. C., & Mitchell, O. S. (2017). Optimal financial knowledge and wealth inequality. Journal of Political Economy, 125 (2), 431–477.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2008). Planning and financial literacy: how do women fare? American Economic Review, 98 , 413–417.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011a). The outlook for financial literacy. In O. S. Mitchell & A. Lusardi (Eds.), Financial literacy: implications for retirement security and the financial marketplace (pp. 1–15). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011b). Financial literacy and planning: implications for retirement wellbeing. In O. S. Mitchell & A. Lusardi (Eds.), Financial literacy: implications for retirement security and the financial marketplace (pp. 17–39). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011c). Financial literacy around the world: an overview. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 10 (4), 497–508.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52 (1), 5–44.

Lusardi, A., Mitchell, O. S., & Oggero, N. (2018). The changing face of debt and financial fragility at older ages. American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings, 108 , 407–411.

Lusardi, A., Samek, A., Kapteyn, A., Glinert, L., Hung, A., & Heinberg, A. (2017). Visual tools and narratives: new ways to improve financial literacy. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 16 (3), 297–323.

Lusardi, A., & Tufano, P. (2009). Teach workers about the peril of debt. Harvard Business Review , 22–24.

Lusardi, A., & Tufano, P. (2015). Debt literacy, financial experiences, and overindebtedness. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 14 (4), 332–368.

Mitchell, O. S., & Lusardi, A. (2015). Financial literacy and economic outcomes: evidence and policy implications. The Journal of Retirement, 3 (1).

Moore, Danna. 2003. Survey of financial literacy in Washington State: knowledge, behavior, attitudes and experiences. Washington State University Social and Economic Sciences Research Center Technical Report 03–39.

Mottola, G. R. (2013). In our best interest: women, financial literacy, and credit card behavior. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Moure, N. G. (2016). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Chile. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 15 (2), 203–223.

OECD. (2017). PISA 2015 results (Volume IV): students’ financial literacy . Paris: PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264270282-en .

Sekita, S. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Japan. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 637–656.

Urban, C., Schmeiser, M., Collins, J. M., & Brown, A. (2018). The effects of high school personal financial education policies on financial behavior. Economics of Education Review . https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272775718301699 .

Utkus, S., & Young, J. (2011). Financial literacy and 401(k) loans. In O. S. Mitchell & A. Lusardi (Eds.), Financial literacy: implications for retirement security and the financial marketplace (pp. 59–75). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van Rooij, M. C., Lusardi, A., & Alessie, R. J. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement preparation in the Netherlands. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 10 (4), 527–545.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This paper represents a summary of the keynote address I gave to the 2018 Annual Meeting of the Swiss Society of Economics and Statistics. I would like to thank Monika Butler, Rafael Lalive, anonymous reviewers, and participants of the Annual Meeting for useful discussions and comments, and Raveesha Gupta for editorial support. All errors are my responsibility.

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

Author information, authors and affiliations.

The George Washington University School of Business Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center and Italian Committee for Financial Education, Washington, D.C., USA

Annamaria Lusardi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Annamaria Lusardi .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares that she has no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lusardi, A. Financial literacy and the need for financial education: evidence and implications. Swiss J Economics Statistics 155 , 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41937-019-0027-5

Download citation

Received : 22 October 2018

Accepted : 07 January 2019

Published : 24 January 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s41937-019-0027-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Writing Prompts for Weekly Journaling in Personal Finance

Thanks to Brian Page of Reading High School for getting the tweets started and for the multiple contributors to his initial inquiry:

What reflection prompts should be required in a student financial literacy journal, as least weekly?

The responses are rolling in:

- What did you learn that you will put to practice now or in the near future?

- What tools did you discover that you plan to use now or in the near future?

- What was the strongest emotion you had this week relating to money? Could be your spending, saving or giving — or friend/family/govnmt.

- Another potential prompt: I wish we would spend additional time exploring ___(name one or more concepts) because __________

- I regularly ask my students: If we had more time in class, I’d like to know more about _____.

- Name something you bought with your own money. Are you happy with the purchase? Or do you wish you still had the money to spend?

- Identify 1 money decision you made this week (saving, spending or giving). Did you consider alternatives? Would you do something different?

- What money topic did you discuss with parent/guardian/friend/sibling this week? What did you learn? Encourage conversation. Uncover myths.

Interested in other writing prompts? Here a few more:

- Ten that we developed

- Ten from the NY Times

About the Author

Tim ranzetta.

Tim's saving habits started at seven when a neighbor with a broken hip gave him a dog walking job. Her recovery, which took almost a year, resulted in Tim getting to know the bank tellers quite well (and accumulating a savings account balance of over $300!). His recent entrepreneurial adventures have included driving a shredding truck, analyzing executive compensation packages for Fortune 500 companies and helping families make better college financing decisions. After volunteering in 2010 to create and teach a personal finance program at Eastside College Prep in East Palo Alto, Tim saw firsthand the impact of an engaging and activity-based curriculum, which inspired him to start a new non-profit, Next Gen Personal Finance.

SEARCH FOR CONTENT

Behavioral Economics

Consumer Skills

Current Events

Curriculum Announcements

ELL Resources

FinCap Friday

Interactive

Paying for College

Press Releases

Podcasts in the Classroom

Professional Development

Question of the Day

So Expensive Series

Subscribe to the blog

Join the more than 11,000 teachers who get the NGPF daily blog delivered to their inbox:

MOST POPULAR POSTS

Question of the Day: How long does the average user spend on TikTok a day?

Top 5 Sub Plan Activities

Question of the Day [Women's History Month]: Match these CEOs with the S&P 500 companies they lead

Useful Personal Finance Movies and Documentaries with Worksheets

Tax Unit Updated for the Current Tax Filing Year

Awarded one of the Top Personal Finance Blogs

Awarded one of the Best Advocacy Blogs and Websites

Sending form...

One more thing.

Before your subscription to our newsletter is active, you need to confirm your email address by clicking the link in the email we just sent you. It may take a couple minutes to arrive, and we suggest checking your spam folders just in case!

Great! Success message here

New to NGPF?

Save time, increase student engagement, and help your students build life-changing financial skills with NGPF's free curriculum and PD.

Start with a FREE Teacher Account to unlock NGPF's teachers-only materials!

Become an ngpf pro in 4 easy steps:.

1. Sign up for your Teacher Account

2. Explore a unit page

3. Join NGPF Academy

4. Become an NGPF Pro!

Teacher Account Log In

Not a member? Sign Up

Forgot Password?

Thank you for registering for an NGPF Teacher Account!

Your new account will provide you with access to NGPF Assessments and Answer Keys. It may take up to 1 business day for your Teacher Account to be activated; we will notify you once the process is complete.

Thanks for joining our community!

The NGPF Team

Want a daily question of the day?

Subscribe to our blog and have one delivered to your inbox each morning, create a free teacher account.

Complete the form below to access exclusive resources for teachers. Our team will review your account and send you a follow up email within 24 hours.

Your Information

School lookup, add your school information.

To speed up your verification process, please submit proof of status to gain access to answer keys & assessments.

Acceptable information includes:

- a picture of you (think selfie!) holding your teacher/employee badge

- screenshots of your online learning portal or grade book

- screenshots to a staff directory page that lists your e-mail address

- any other means that can prove you are not a student attempting to gain access to the answer keys and assessments.

Acceptable file types: .png, .jpg, .pdf.

Create a Username & Password

Once you submit this form, our team will review your account and send you a follow up email within 24 hours. We may need additional information to verify your teacher status before you have full access to NGPF.

Already a member? Log In

Welcome to NGPF!

Take the quiz to quickly find the best resources for you!

ANSWER KEY ACCESS

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Financial Literacy

Course: financial literacy > unit 1.

- Welcome to Financial Literacy

- Welcome to Financial Literacy!

What is financial literacy?

Is financial literacy just about knowing how to budget, is it too late for me to become financially literate, do i need specific math skills to be financially literate, isn't financial literacy only important for people who make a lot of money, is it enough to just put my money in a savings account, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

The Ultimate Guide to Financial Literacy for Adults

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is Financial Literacy?

Personal finance basics.

- Bank Accounts

- Credit Cards

- How to Start Investing

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

The Bottom Line

Learn the skills now that you need for a more financially secure life

Caleb has been the Editor-in-Chief of Investopedia since 2016. He is an award-winning media executive with more than 20 years of experience in business news, digital publishing, and documentaries. Caleb is the on the Board of Governors and Executive Committee of SABEW (Society for Advancing Business Editing & Writing), and his awards include a Peabody, EPPY, SABEW Best in Business, and two Emmy nominations.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/CopyofCaleb_Final-CalebSilver-5c09a16346e0fb000182c90c.jpg)

We know that the earlier you learn the basics of how money works, the more confident and successful you’ll be with your finances later in life. It’s never too late to start learning, but it pays to have a head start. The first steps into the world of money start with education.

Banking, budgeting, saving, credit, debt, and investing are the pillars that support most of the financial decisions that we’ll make in our lives. At Investopedia, we have more than 30,000 articles, terms, Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs), and videos that explore these topics. We’ve spent more than 20 years building and improving our resources to help you make smart financial and investing decisions.

This guide is a great place to start, and today is a great day to do it. Let’s begin with financial literacy —what it is and how it can improve your life.

Key Takeaways

- Financial literacy is the ability to understand and make use of a variety of financial skills.

- Those with higher levels of financial literacy are more likely to spend less income, create an emergency fund, and open a retirement account than those with lower levels.

- Some of the basics of financial literacy and its practical application in everyday life include banking, budgeting, handling debt and credit, and investing.

Financial literacy is the ability to understand and make use of a variety of financial skills, including personal financial management, budgeting, and investing. It also means comprehending certain financial principles and concepts, such as the time value of money , compound interest , managing debt, and financial planning.

Achieving financial literacy can help individuals to avoid making poor financial decisions. It can help them become self-sufficient and achieve financial stability. Key steps to attaining financial literacy include learning how to create a budget, track spending, pay off debt, and plan for retirement.

Educating yourself on these topics also involves learning how money works, setting and achieving financial goals, becoming aware of unethical/discriminatory financial practices, and managing financial challenges that life throws your way.

The Importance of Financial Literacy

In its National Financial Capability Study the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) found that Americans’ with higher levels of financial literacy were more likely to make ends meet, spend less of their income, create a three-month emergency fund, and open a retirement account than those with lower financial literacy.

Making informed financial decisions is more important than ever. Take retirement planning. Many workers once relied on pension plans to fund their retirement lives, with the financial burden and decision-making for pension funds borne by the companies or governments that sponsored them.

Today, few workers get pensions; instead some are offered the option of participating in a 401(k) plan . This involves decisions that employees themselves have to make about contribution levels and investment choices. Those without employer options need to actively seek out and open individual retirement accounts (IRAs) and other tax-advantaged retirement accounts .

Add to this people’s increasing life spans (leading to longer retirements), Social Security benefits that barely support basic survival, complicated health and other insurance options, more complex savings and investment instruments to select from—and a plethora of choices from banks, credit unions, brokerage firms, credit card companies, and more.

It’s clear that financial literacy is a must for making thoughtful and informed decisions, avoiding unnecessary levels of debt, helping family members through these complex decisions, and having adequate income in retirement.

Personal finance is where financial literacy translates into individual financial decision-making. How do you manage your money? Which savings and investment vehicles are you using? Personal finance is about making and meeting your financial goals, whether you want to own a home, help other members of your family, save for your children’s college education, support causes that you care about, plan for retirement, or anything else.

Among other topics, it encompasses banking, budgeting, handling debt and credit, and investing. Let’s take a look at these basics to get you started.

Introduction to Bank Accounts

A bank account is typically the first financial account that you’ll open. Bank accounts can hold and build the money you'll need for major purchases and life events. Here’s some background on bank accounts and why they are step one in creating a stable financial future.

Why Do I Need a Bank Account?

Though the majority of Americans do have bank accounts, 6% of households in the United States still don’t have one. Why is it so important to open a bank account? Because it’s safer than holding cash. Assets held in a bank are harder to steal, and in the U.S., they’re generally insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) . That means you should always have access to your cash, even if every customer decided to withdraw their money at the same time.

Many financial transactions require you to have a bank account to:

- Use a debit or credit card

- Use payment apps like Venmo or PayPal

- Write a check

- Buy or rent a home

- Receive your paycheck from your employer

- Earn interest on your money

Online vs. Brick-and-Mortar Banks

When you think of a bank, you probably picture a building. This is called a brick-and-mortar bank. Many brick-and-mortar banks also allow you to open accounts and manage your money online.

Some banks are only online and have no physical buildings. These banks typically offer the same services as brick-and-mortar banks, aside from the ability to visit them in person.

Which Type of Bank Can I Use?

Retail banks : This is the most common type of bank at which people have accounts. Retail banks are for-profit companies that offer checking and savings accounts, loans, credit cards, and insurance. Retail banks can have physical, in-person buildings that you can visit or they can be online only. Most offer both options. Banks’ online technology tends to be advanced, and they often have more locations and ATMs nationwide than credit unions do.

Credit unions : Credit unions provide savings and checking accounts, issue loans, and offer other financial products, just like banks do. However, they are not-for-profit organizations owned by their members. Credit unions tend to have lower fees and better interest rates on savings accounts and loans. Credit unions are sometimes known for providing more personalized customer service, though they usually have far fewer branches and ATMs.

Assets held in a credit union are insured by the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) , which is equivalent to the FDIC for banks.

What Types of Bank Accounts Can I Open?

There are three main types of bank accounts that the average person may want to open:

1. Savings account : A savings account is an interest-bearing deposit account held at a bank or other financial institution. Savings accounts typically pay a low interest rate, but their safety and reliability make them a sensible option for saving available cash for short-term needs.

They may have some legal limitations on how often you can withdraw money . However, they’re generally very flexible so they’re ideal for building an emergency fund, saving for a short-term goal like buying a car or going on vacation, or simply storing extra cash that you don’t need in your checking account.

2. Checking account : A checking account is also a deposit account at a bank or other financial institution that allows you to make deposits and withdrawals. Checking accounts are very liquid, meaning that they allow numerous withdrawals per month (as opposed to less liquid savings or investment accounts) though they earn little to no interest.

Money can be deposited at banks and ATMs, through direct deposit, or through another type of electronic transfer. Account holders can withdraw funds via banks and ATMs, by writing checks, or using debit cards linked to their accounts.

You may be able to find a checking account with no fees. Others have monthly and other charges (such as for overdrafts or using an out-of-network ATM) based on, for example, how much you keep in the account or whether there’s a direct deposit paycheck or automatic-withdrawal mortgage payment connected to the account.

Lifeline and second-chance accounts , available at some banks, can help those who have difficulty qualifying for a traditional checking account.

3. High-yield savings account : A high-yield savings account usually pays a much higher rate of interest than a standard savings account. The tradeoff for earning more interest on your money is that high-yield accounts tend to require bigger initial deposits, larger minimum balances, and higher fees.

You might be able to open a high-yield savings account at your current bank, but online banks tend to have the highest interest rates.

What’s An Emergency Fund?

An emergency fund is not a specific type of bank account but can be any source of cash that you’ve saved to help you handle financial hardships like job losses, medical bills, or car repairs. Here's how they work:

- Most people use a separate savings account for their emergency savings.

- The account should eventually total enough to cover at least three to six months’ worth of expenses.

- Emergency fund money should be off-limits for paying regular expenses.

Introduction to Credit Cards

You know them as the plastic cards that (almost) everyone carries in their wallets. Credit cards are accounts that let you borrow money from the credit card issuer and pay it back over time. For every month that you don’t pay back the money in full, you’ll be charged interest on your remaining balance . Note that some credit cards, called charge cards , require you to pay your balance in full each month. However, these are less common.

What’s the Difference Between Credit and Debit Cards?

Here is the difference :

Debit cards take money directly out of your checking account. You can’t borrow money with debit cards, which means that you can’t spend more cash than you have in the bank. And debit cards don’t help you to build a credit history and credit rating .

Credit cards allow you to borrow money and do not pull cash from your bank account. This can be helpful for large, unexpected purchases. But carrying a balance every month—not paying back in full the money that you borrowed—means that you’ll owe interest to the credit card issuer. In fact, as of Q4 2022, Americans owed $986 billion in credit card debt. So be very careful about spending more money than you have, because debt can build up quickly and become difficult to pay off.

On the other hand, using a credit card judiciously and paying your credit card bills on time helps you establish a credit history and a good credit rating. It’s important to build a good credit rating not only to qualify for the best credit cards but also because you will get more favorable interest rates on car loans, personal loans, and mortgages.

What Is APR?

APR stands for annual percentage rate. This is the amount of interest that you’ll owe the credit card issuer on any unpaid balance. You’ll want to pay close attention to this number when you apply for a credit card. A higher number can cost you hundreds or even thousands of dollars if you carry a large balance over time. The median APR today is about 24% , but your rate may be higher if you have bad credit . Interest rates also tend to vary by the type of credit card.

Which Credit Card Should I Choose?

Credit scores have a big impact on your odds of getting approved for a credit card. Understanding what range your score falls into can help you narrow the options as you decide on the cards for which you may apply. Beyond your credit score, you’ll also need to decide which perks best suit your lifestyle and spending habits.

If you’ve never had a credit card before, or if you have bad credit, you’ll likely need to apply for either a secured credit card or a subprime credit card . By using one of these and paying back on time, you can raise your credit score and earn the right to credit at better rates.

If you have a fair to good credit score, you can choose from a variety of credit card types, such as:

- Travel rewards cards. These credit cards offer points redeemable for travel—including flights, hotels, and rental cars—with each dollar you spend.

- Cash-back cards . If you don’t travel often—or don’t want to deal with converting points into real-life perks—a cash-back card might be the best fit for you. Every month, you’ll receive a small portion of your spending back, in cash or as a credit to your statement.

- Balance transfer cards. If you have balances on other cards with high interest rates, transferring your balance to a lower-rate credit card could save you money, help you pay off balances, and help improve your credit score.

- Low- or No-APR cards. If you routinely carry a balance from month to month, switching to a credit card with a low or no APR could save you hundreds of dollars per year in interest payments.

Be aware of your protections under the Equal Credit Opportunity Act . Research credit opportunities and available interest rates, and be sure that you are offered the best rates for your particular credit history and financial situation.

How to Create a Budget

Creating a budget is one of the simplest and most effective ways to control your spending, saving, and investing. You can’t begin to improve your financial health if you don’t know where your money is going, so start tracking your expenses against your income. Then set clear goals.

One budget template that helps individuals reach their goals, manage their money, and save for emergencies and retirement is the 50/20/30 budget rule : spending 50% on needs, 20% on savings, and 30% on wants.

How Do I Create a Budget?

Budgeting starts with tracking how much money you receive and spend every month. You can do this in an Excel sheet, on paper, or with a budgeting app . It’s up to you. However you decide to track, clearly lay out the following:

- Income: List all sources of money that you receive in a month, with the dollar amount. This can include paychecks, investment income, alimony, settlements, and money that you make from side jobs or other projects, such as selling crafts.

- Expenses: List every purchase that you make in a month, split into two categories: fixed expenses and discretionary spending . Review your bank statements, credit card statements, and brokerage account statements to be sure to capture them all. Fixed expenses are the purchases that you must make every month. Their amounts don’t change (or change very little) and are considered essential. They include rent/mortgage payments, loan payments, and utilities. Discretionary spending is nonessential spending or varying purchases for things like restaurant meals, shopping, clothes, and travel. Consider them wants rather than needs.

- Savings : Record the amount of money that you’re able to save each month, whether it’s in cash, cash deposited into a bank account, or money that you add to an investment account or retirement account like an IRA or 401(k) (if your employer offers one).

Subtract your total expenses from your total income to get the amount of money you have left at the end of the month. Now that you have a clear picture of money coming in, money going out, and money saved, you can identify which expenses you can cut back on, if necessary.

If you don’t already have one, put your extra money into an emergency fund until you’ve saved at least three to six months’ worth of expenses (in case of a job loss or other emergency). Don’t use this money for discretionary spending. The key is to keep it safe and grow it for times when your income decreases or stops.

How to Start Investing

Once you have enough savings to start investing, you’ll want to learn the basics of where and how to invest your money. Decide what to invest in and how much to invest by understanding the risks (and potential rewards) of different types of investments.

What Is the Stock Market?

The stock market refers to the collection of markets and exchanges where stock buying and selling takes place. The terms “stock market” and “stock exchange” can be used interchangeably. And even though it’s called a stock market, other financial securities , such as exchange-traded funds (ETFs) , corporate bonds , and derivatives based on stocks, commodities, currencies, and bonds, are also traded there. There are multiple stock trading venues. The leading stock exchanges in the U.S. include the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) , Nasdaq , and the Cboe Options Exchange .

How Do I Invest?

To buy stocks , you need to use a broker . This is a professional person or digital platform whose job it is to handle the transaction for you. For new investors, there are three basic categories of brokers:

- A full-service broker who manages your investment transactions and provides advice for a fee.

- An online/discount broker that executes your transactions and provides advice depending on how much you have invested. Examples include Fidelity, TD Ameritrade, and Charles Schwab.

- A robo-advisor that executes your trades and can pick investments for you with little human assistance. Examples include Betterment, Wealthfront, and Schwab Intelligent Portfolios.

What Should I Invest in?

There’s no right answer for everyone. Which securities you buy, and how much you buy, will depend on the amount of money that you have available for investing and how much risk you’re willing to take to try to earn a higher return. Here are the most common securities to invest in, listed in descending order of risk:

Stocks: A stock (also known as “shares” or “equity”) is a type of investment that signifies partial ownership in the issuing company. This entitles the stockholder to a proportion of the corporation’s assets and earnings.

Owning stock gives you the right to vote in shareholder meetings, receive dividends (which come from the company’s profits) if and when they are distributed, and sell your shares to somebody else.

The price of a stock fluctuates throughout the day and can depend on many factors, including the company’s performance, the domestic economy, the global economy, the day’s news, and more. Stocks can rise in value, fall in value, or even become worthless, making them more volatile and potentially riskier than many other types of investments.

ETFs: An exchange-traded fund, or ETF, consists of a collection of securities, such as stocks. It often tracks an underlying index . ETFs can invest in any number of industry sectors or use various strategies.

Think of an ETF as a pie containing many different securities. When you buy shares of an ETF, you’re buying a slice of the pie, which contains slivers of the securities inside. This lets you purchase a variety of many stocks at once, with the ease and convenience of only one purchase—the ETF.

In many ways, ETFs are similar to mutual funds. For instance, they both offer instant diversification and are professionally managed. However, ETFs are listed on exchanges and ETF shares trade throughout the day just like ordinary stocks.

Investing in ETFs is considered less risky than investing in individual stocks because there are many securities inside the ETF. If some of those securities fall in value, others may stay steady or rise in value.

Mutual funds: A mutual fund is a type of investment consisting of a portfolio of stocks, bonds, or other securities. Mutual funds give small or individual investors access to diversified, professionally managed portfolios at a low price.

There are many categories of mutual funds, representing the kinds of securities in which they invest, their investment objectives, and the type of returns that they seek. Most employer-sponsored retirement plans invest in mutual funds.

Investing in shares of a mutual fund is different from investing in individual shares of stock because a mutual fund owns many different stocks (or other securities). Unlike stocks or ETFs that trade at varying prices throughout the day, mutual fund purchases and redemptions take place only at the end of each trading day and at a fund's net asset value (NAV) . Similar to ETFs, mutual funds are considered less risky than stocks because of their diversification .

Mutual funds charge annual fees, called expense ratios , and in some cases, commissions.

Bonds: Bonds are issued by companies, municipalities, states, and sovereign governments to finance projects and operations. When an investor buys a bond, they’re effectively lending their money to the bond issuer, with the promise of repayment plus interest. A bond’s coupon rate is the interest rate that the investor will earn.

A bond is referred to as a fixed-income instrument because bonds traditionally have paid a fixed interest rate to investors, although some bonds pay variable interest rates . Bond prices inversely correlate with interest rates. When rates go up, bond prices fall, and vice versa. Bonds have maturity dates, which are the point in time when the principal amount must be paid back to the investor in full or the issuer will risk default.

Bonds are rated by how likely the issuer is to pay you back. Higher-rated bonds, known as investment grade bonds, are viewed as safer and more stable. Such offerings are tied to publicly traded corporations and government entities that boast positive outlooks.

Investment grade bonds receive “AAA” to “BBB-” ratings from Standard and Poor’s and “Aaa” to “Baa3” ratings from Moody’s. Bonds with higher ratings will usually pay lower rates of interest than those with lower ratings. U.S. Treasury bonds are the most common AAA-rated bond securities.

Are Banks Safe?

Most bank accounts in the United States are insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) up to certain limits, currently defined as “up to at least $250,000 per depositor, per FDIC-insured bank, per ownership category.” If you have a great deal of money to put in the bank, you can make sure that it’s all covered by opening multiple accounts.

Is It Safe to Invest in the Stock Market?

Stocks are inherently risky—some more than others—and you can lose money if their share prices fall. Brokerage accounts are insured by the Securities Investor Protection Corporation for up to $500,000 in securities and cash. However, that applies only if the brokerage firm fails and is unable to repay its customers. It does not cover normal investor losses.

What Is the Safest Investment?

U.S. Treasury securities, including bonds, bills, and notes, are backed by the U.S. government and generally are considered the safest investments in the world. However, these kinds of investments tend to pay low rates of interest, so investors do face a risk that inflation may erode the purchasing power of their money over time.

The topics in this article are just the beginning of a financial education, but they cover the most important and frequently used products, tools, and tips for getting started. If you’re ready to learn more, check out these additional resources from Investopedia:

- Investopedia Academy

- Investopedia YouTube Channel

- Investopedia Dictionary

- Investopedia Stock Market Simulator

FINRA. " National Study by FINRA Foundation Finds U.S. Adults’ Financial Capability Has Generally Grown Despite Pandemic Disruption. "

Federal Reserve System. " Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2022 - May 2023 ."

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. “ What’s Covered: Are My Deposit Accounts Insured by the FDIC? ”

National Credit Union Administration (NCUA). " Mission and Values ."

Federal Reserve Bank of New York. “ Total Household Debt Reaches $16.90 trillion in Q4 2022; Mortgage and Auto Loan Growth Slows ."

S&P Global. " S&P Global Ratings Definitions. "

Moody's. " Rating Scale and Definitions ."

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. “ Deposit Insurance FAQs .”

Securities Investor Protection Corporation. “ Mission .”

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. " Treasury Securities ."

- The Ultimate Guide to Financial Literacy for Adults 1 of 30

- The Racial Gap in Financial Literacy 2 of 30

- How to Go From Unbanked or Underbanked to Banked 3 of 30

- How to Open a Checking Account Online 4 of 30

- Where Can You Cash Checks? 5 of 30

- Money Orders: When, Where, and How 6 of 30

- How to Read a Consumer Credit Report 7 of 30

- How To Build Credit When You Have None 8 of 30

- Debit Card vs. Credit Card: What's the Difference? 9 of 30

- Buy Now, Pay Later vs. Credit Cards 10 of 30

- How to Get Out of Debt in 8 Steps 11 of 30

- Student Debt: What It Means, How It Works, and Forgiveness 12 of 30

- Pros and Cons of Debt Management Plans 13 of 30

- How to File Back Taxes 14 of 30

- What You Should Know About Debt Relief 15 of 30

- Should You Save Your Money or Invest It? 16 of 30

- How to Save Money for Your Big Financial Goals 17 of 30

- Simple Interest vs. Compound Interest: What's the Difference? 18 of 30

- Generational Wealth: Overview, Examples and FAQs 19 of 30

- 10 Investing Concepts Beginners Need to Learn 20 of 30

- How to Invest on a Shoestring Budget 21 of 30

- What You Must Know Before Investing in Cryptocurrency 22 of 30

- What Is a Digital Wallet? 23 of 30

- Apple Pay vs. Google Wallet 24 of 30

- How Safe Is Venmo and Is It Free? 25 of 30

- What Can You Buy With Bitcoin? 26 of 30

- Best Resources for Improving Financial Literacy 27 of 30

- Personal Finance Influencer Red Flags 28 of 30

- Top 10 Personal Finance Podcasts 29 of 30

- Dial 211 for Help With Your Finances 30 of 30

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/mmf-e9fd020388064561be3294b88a9e7760.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

Home — Essay Samples — Economics — Money — Importance of Money Management and Financial Literacy for Students

Importance of Money Management and Financial Literacy for Students

- Categories: Literacy Money Personal Finance

About this sample

Words: 1537 |

Published: Aug 14, 2023

Words: 1537 | Pages: 3 | 8 min read

Table of contents

Importance of financial literacy and financial education, how other countries apply financial literacy, what can be done within our current school systems, my own financial literacy level.

- Anderloni, L. and Vandone, D. (2010), “Risk of overindebtedness and behavioral factors”, Working Paper No 25, Social Science Research Network, Santa Monica, CA.

- ASIC (2011), “National financial literacy strategy: Australian securities & investment commission Report No. 229”, available at: www.financialliteracy.gov.au/media/218312/national-financialliteracy-strategy.pdf (accessed 23 October 2016).

- Atkinson, A. and Messy, F. (2012), “Measuring financial literacy: results of the OECD/International Network on Financial Education (INFE) Pilot study”, Working Paper No. 15, OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Filipiak, U. and Walle, Y.M. (2015), “The financial literacy gender gap: a question of nature or nurture?”, Discussion Papers No. 176, Courant Research Centre: Poverty, Equity and Growth.

- Huston, S.J. (2010), “Measuring financial literacy”, The Journal of Consumer Affairs, Vol. 44 No. 2, pp. 296-316.

- National Strategy for Financial Literacy (2012), “Commission for financial literacy and retirement income”, available at: www.cflri.org.nz/sites/default/files/docs/FL-NS-National%20Strategy2012-Aug.pdf (accessed 24 October 2016).