20 Must-Read Queer Essay Collections

Laura Sackton

Laura Sackton is a queer book nerd and freelance writer, known on the internet for loving winter, despising summer, and going overboard with extravagant baking projects. In addition to her work at Book Riot, she reviews for BookPage and AudioFile, and writes a weekly newsletter, Books & Bakes , celebrating queer lit and tasty treats. You can catch her on Instagram shouting about the queer books she loves and sharing photos of the walks she takes in the hills of Western Mass (while listening to audiobooks, of course).

View All posts by Laura Sackton

I love essay collections, and I love queer books, so obviously I love queer essay collections. An essay collection can be so many things. It can be an opportunity to examine one particular subject in depth. Or it can be a wonderful messy mix of dozens of themes and ideas. The books on this list are a mix of both. Some hone in on an author’s own life, while others look outward, examining current events, history, and pop culture. Some are funny, some are very serious, and some are decidedly both.

In making this list, I used two criteria: 1) queer authors and 2) queer content. There are, of course, plenty of wonderful essay collections out there by queer authors that aren’t about queerness. But this list focuses on essays that explore queerness in all its messy glory. You’ll also find essays here about many other things: tornadoes, step-parenthood, the internet, tarot, activism, online dating, to name just a few. But taken together, the essays in each of these books add up to a queer whole.

I limited myself to living authors, and even so, there were so many amazing queer essay collections I wanted to include but couldn’t. This is just a drop in the bucket, but it’s a great place to start if you need more queer essays in your life — and who doesn’t?

Personal Queer Essay Collections

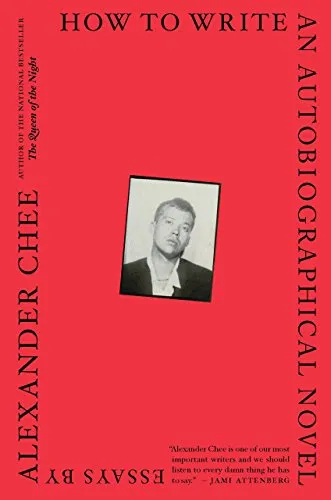

How to Write An Autobiographical Novel by Alexander Chee

It’s hard for me to put my finger on the thing that elevates an essay collection from a handful of individual pieces to a cohesive book. But Chee obviously knows what that thing is, because this book builds on itself. He writes about growing roses and working odd jobs and AIDS activism and drag and writing a novel, and each of these essays is singularly moving. But as a whole they paint a complex portrait of a slice of the writer’s life. They inform and converse with each other, and the result is a book you can revisit again and again, always finding something new.

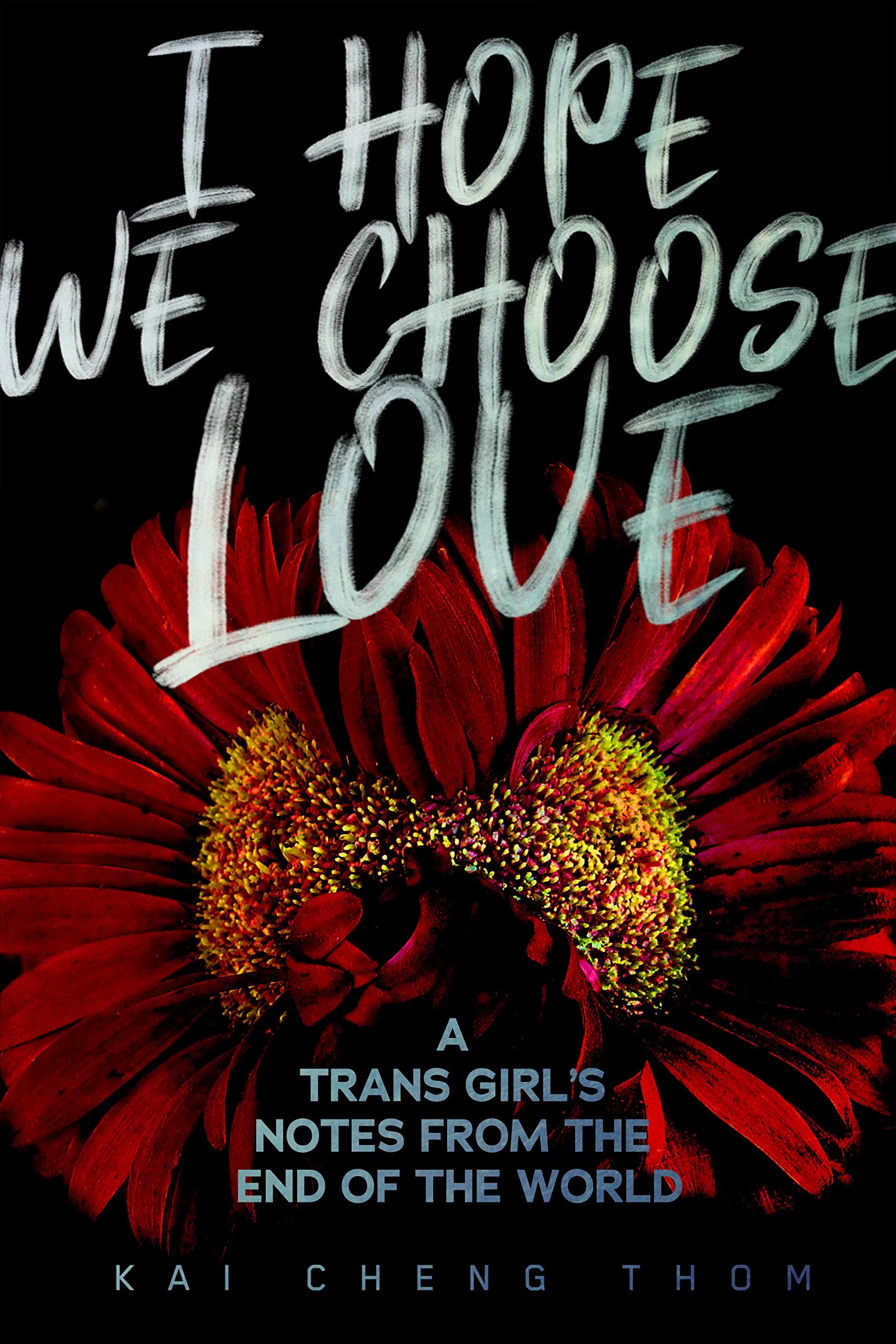

I Hope We Choose Love by Kai Cheng Thom

In this collection of beautiful and thought-provoking essays, Kai Cheng Thom explores the messy, far-from-perfect realties of queer and trans communities and community movements. She writes about what many community organizers, activists, and artists don’t want to talk about: the hard stuff, the painful stuff, the bad times. It’s not all grim, but it’s very real. Thom addresses transphobia, racism, and exclusion, but she also writes about the particular joys she’s found in creating community and family with other queer and trans people of color. This is a must-read for anyone involved in social justice work, or immersed in queer community.

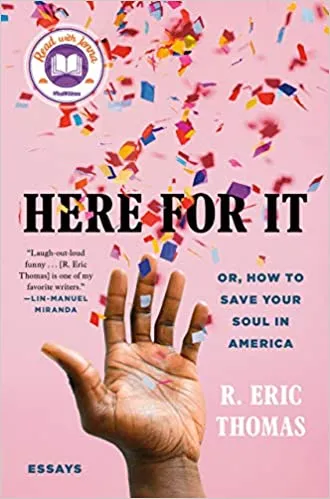

Here For It by R. Eric Thomas

If you enjoy books that blend humor and heartfelt wisdom, you’ll love this collection. R. Eric Thomas writes about coming of age as a writer on the internet, his changing relationship to Christianity, the messy intersections of his queer Black identity. It’s a lovey mix of grappling and quips. It’s full of pop culture references and witty asides, as well as moving, vulnerable personal stories.

The Rib Joint by Julia Koets

This slim memoir-in-essays is entirely personal. Although Koets does weave some history, pop culture, and religion into the work — everything from the history of organs to Sally Ride — her gaze is mostly focused inward. The essays are short and beautifully written; she often leaves the analysis to the reader, simply letting distinct and sometimes contradictory ideas and images sit next to each other on the page. She writes about her childhood in the South, the hidden and often invisible queer relationships she had as a teenager and young adult, secrets and closets, and the tensions and overlaps between religion and queerness.

I Can’t Date Jesus by Michael Arceneaux

This is another fantastic humorous essay collection. Arceneaux somehow manages to be laugh-out-loud funny while also delivering nuanced cultural critique and telling vulnerable stories from his life. He writes about growing up in Houston, family relationships, coming out, and so much more. The whole book wrestles with how to be a young Black queer person striving to make meaning in the world. His second collection, I Don’t Want to Die Poor , is equally wonderful.

Tomboyland by Melissa Faliveno

If you’re wondering, this is the book that contains an essay about tornadoes. It also contains a gorgeous essay about pantry moths (among other things). Those are just two of the many subjects Faliveno plumbs the depths of in this remarkable book. She writes about gender expression and how her relationship with gender has changed throughout her life, about queer desire and family, about Midwestern culture, about place and home, about bisexuality and bi erasure. Her far-ranging essays challenge mainstream ideas about what queer lives do and do not look like. She asks more questions than she answers, delving into the murky terrain of desire and identity.

Something That May Shock and Discredit You by Daniel M. Lavery

Is this book even an essay collection? It is, and it isn’t. Some of these pieces are deeply personal stories about Lavery’s experience with transition. Others are trans retellings of mythology, literature, and film. All of it is weird and smart and impossibly to classify. Lavery examines the idea of transition from every angle, creating new stories about trans history, trans identity, and transformation itself.

Brown White Black by Nishta J. Mehra

If there’s one thing I love most in an essay collection, it’s when an author allows contradictions and messy, fraught truths to live next to each other on the page. I love when an essayist asks more questions than they answer. That’s what Mehra does in this book. An Indian American woman married to a white woman and raising a Black son, she writes with openness and curiosity about her particular family. She explores how race, sexuality, gender, class, and religion impact her life and most intimate relationships, as well as American culture more broadly.

Blood, Marriage, Wine, & Glitter by S. Bear Bergman

This essay collection is an embodiment of queer joy, of what it means to become part of a queer family. Every essay captures some aspect of the complexity and joy that is queer family-making. Bergman writes about being a trans parent, about beloved friends, about the challenges of partnership, about intimacy in myriad forms. His tone is warm and open-hearted and joyful and celebratory.

Forty-Three Septembers by Jewelle Gómez

In these contemplative essays, Jewell Gómez explores the various pieces of her life as a Black lesbian, writing about family, aging, and her own history. Into these personal stories she weaves an analysis of history and current events. She writes about racism and homophobia, both within and outside of queer and Black communities, and about her life as an artist and poet, and how those identities, too, have shaped the way she sees the world.

Pass With Care by Cooper Lee Bombardier

Set mostly against the backdrop of queer culture in 1990s San Francisco, this memoir in essays is about trans identity, being an artist, masculinity, queer activism, and so much more. Bombardier brings particular places and times to life (San Francisco in the 1990s, but other places as well), but he also connects those times and experiences to the present in really interesting ways. He recognizes the importance of queer and trans history, while also exploring the possibilities of queer and trans futures.

Care Work by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

This is a beautiful, rigorous collection of essays about disability justice centering disabled queer and trans people of color. From an exploration of the radical care collectives Piepzna-Samarasinha and other queer and trans BIPOC have organized to an essay where examines the problems with the “survivor industrial complex,” every one of these pieces is full of wisdom, anger, transformation, radical celebration. It challenged me on so many levels, in the best possible way. It’s a must read for anyone engaged in any kind of activist work.

I’m Afraid of Men by Vivek Shraya

I’m cheating a little bit here, because technically I’d classify this book as one essay, singular, rather than a collection of essays. But I’m including it anyway, because it is brilliant, and because I think it exemplifies just what a good essay can do, what a powerful form of writing it can be. By reflection on various experiences Shraya has had with men over the course of her life, she examines the connections and intersections between sexism, transmisogyny, toxic masculinity, and sexual violence. It’s a heavy read, but Shraya’s writing is anything but. It’s agile and graceful, flowing and jumping between disparate thoughts and ideas. This is a book-length essay you can read in one sitting, but it’ll leave you with enough to think about for many days afterward.

Gender Failure by Ivan E. Coyote and Rae Spoon

In this collaborative essay collection, trans writers and performers Ivan E. Coyote and Rae Spoon play with both gender and form. The book is a combination of personal essays, short vignettes, song lyrics, and images. Using these various kinds of storytelling, they both recount their own particular journeys around gender — how their genders have changed throughout their lives, the ways the gender binary has continually harmed them both, and the many communities, people, and experiences that have contributed to joyful self-expression and gender freedom.

The Groom Will Keep His Name by Matt Ortile

Matt Ortile uses his experiences as a gay Filipino immigrant as a lens in these witty, insightful, and moving essays. By telling his own stories — of dating, falling in love, struggling to “fit in” — he illuminates the intersections among so many issues facing America right now (and always). He writes about the model minority myth and many other myths he told himself about assimilation, sex, power, what it means to be an American. It’s a heartfelt collection of personal essays that engage meaningfully, and critically, with the wider world.

Wow, No Thank You by Samantha Irby

I’m not a big fan of humorous essays in this vein, heavy on pop culture references I do not understand and full of snark. But I absolutely love Irby’s books, which is about the highest praise I can give. I honestly think there is something in here for everyone. Irby is just so very much herself: she writes about whatever the hell she wants to, whether that’s aging or the weirdness of small town America or snacks (there is a lot to say about snacks). And whatever the subject, she’s always got something funny or insightful or new or just super relatable to say.

Queer Essay Anthologies

She Called Me Woman Edited by Azeenarh Mohammed, Chitra Nagarajan, and Aisha Salau

This anthology collects 30 first-person narratives by queer Nigerian women. The essays reflect a range of experiences, capturing the challenges that queer Nigerian women face, as well as the joyful lives and communities they’ve built. The essays explore sexuality, spirituality, relationships, money, love, societal expectations, gender expression, and so much more.

Untangling the Knot: Queer Voices on Marriage, Relationships & Identity by Carter Sickels

When gay marriage was legalized, I felt pretty ambivalent about it, even though I knew I was supposed to be excited. But I have never wanted or cared about marriage. Reading this book made me feel so seen. That’s not to say it’s anti-marriage — it isn’t! It’s a collection of personal essays from a diverse range of queer people about the families they’ve made. Some are traditional. Some are not. The essays are about marriages and friendships, parenthood and siblinghood, polyamorous relationships and monogamous ones. It’s a book that celebrates the different forms queer families take, never valuing any one kind of family or relationship over another.

Nonbinary: Memoirs of Gender and Identity Edited by Micah Rajunov and Scott Duane

This book collects essays from 30 nonbinary writers, and trans and gender-nonconforming writers whose genders fall outside the binary. The writers inhabit a diverse range of identity and experience in terms of race, age, class, sexuality. Some of the essays are explicitly about gender identity, others are about family and relationships, and still others are about activism and politics. As a whole, the book celebrates the expansiveness of trans experiences, and the many ways there are to inhabit a body.

Moving Truth(s): Queer and Transgender Desi Writings on Family Edited by Aparajeeta ‘Sasha’ Duttchoudhury and Rukie Hartman

This anthology brings together a collection of diverse essays by queer and trans Desi writers. The pieces explore family in all its shapes and iterations. Contributors write about community, friendship, culture, trauma, healing. It’s a wonderfully nuanced collection. Though there is a thread that runs through the whole book — queer and trans Desi identity — the range of viewpoints, styles and experiences represented makes it clear how expansive identity is.

Looking for more queer books? I made a list of 40 of my favorites . If you’re looking for more essay collections to add to your list, check out 10 Must-Read Essay Collections by Women , and The Best Essays from 2019 . And if you’re not in the mood for a whole book right now, why not try one of these free essays available online (including some great queer ones)?

You Might Also Like

The Greatest Queer Love Letters of All Time

By maria popova.

UPDATE: Since this piece was originally published in 2014, more gorgeous additions to this canon of the heart’s radiance have come to light: Emily Dickinson to Susan Gilbert , Herman Melville to Nathaniel Hawthorne , Tove Jansson to Tuulikki Pietilä , Iris Murdoch to Brigid Brophy , and John Cage to Merce Cunningham .

As we turn the leaf on a new chapter of modern history that embraces a more inclusive definition of love — both culturally and, at last, politically — here is a celebration of the human heart’s highest capacity through history’s most beautiful and timelessly bewitching LGBTQ love letters.

VIRGINIA WOOLF AND VITA SACKVILLE-WEST

Look here Vita — throw over your man, and we’ll go to Hampton Court and dine on the river together and walk in the garden in the moonlight and come home late and have a bottle of wine and get tipsy, and I’ll tell you all the things I have in my head, millions, myriads — They won’t stir by day, only by dark on the river. Think of that. Throw over your man, I say, and come.

On January 21, Vita sends Virginia this disarmingly honest, heartfelt, and unguarded letter, which stands in beautiful contrast with Virginia’s passionate prose:

I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia. I composed a beautiful letter to you in the sleepless nightmare hours of the night, and it has all gone: I just miss you, in a quite simple desperate human way. You, with all your undumb letters, would never write so elementary a phrase as that; perhaps you wouldn’t even feel it. And yet I believe you’ll be sensible of a little gap. But you’d clothe it in so exquisite a phrase that it should lose a little of its reality. Whereas with me it is quite stark: I miss you even more than I could have believed; and I was prepared to miss you a good deal. So this letter is really just a squeal of pain. It is incredible how essential to me you have become. I suppose you are accustomed to people saying these things. Damn you, spoilt creature; I shan’t make you love me any more by giving myself away like this — But oh my dear, I can’t be clever and stand-offish with you: I love you too much for that. Too truly. You have no idea how stand-offish I can be with people I don’t love. I have brought it to a fine art. But you have broken down my defenses. And I don’t really resent it.

On the day of Orlando ’s publication, Vita received a package containing not only the printed book, but also Virginia’s original manuscript, bound specifically for her in Niger leather and engraved with her initials on the spine.

MARGARET MEAD AND RUTH BENEDICT

Margaret’s love letters to Ruth, posthumously gathered in To Cherish the Life of the World: Selected Letters of Margaret Mead ( public library ) — which also gave us Mead’s prescient position on homosexuality — are a thing of absolute, soul-stirring beauty, on par with such famed epistolary romances as those between Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera , Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz , Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin , and Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir .

In August of 1925, 24-year-old Mead sailed to Samoa, beginning the journey that would produce her enormously influential treatise Coming of Age in Samoa: A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western Civilisation . (Mead, who believed that “one can love several people and that demonstrative affection has its place in different types of relationship,” was married at the time to her first husband and they had an unconventional arrangement that both allowed her to do field work away from him for extended periods of time and accommodated her feelings for Ruth.) On her fourth day at sea, she writes Benedict with equal parts devotion and urgency:

Ruth, dear heart, . . . The mail which I got just before leaving Honolulu and in my steamer mail could not have been better chosen. Five letters from you — and, oh, I hope you may often feel me near you as you did — resting so softly and sweetly in your arms. Whenever I am weary and sick with longing for you I can always go back and recapture that afternoon out at Bedford Hills this spring, when your kisses were rained down on my face, and that memory ends always in peace, beloved.

A few days later:

Ruth, I was never more earthborn in my life — and yet never more conscious of the strength your love gives me. You have convinced me of the one thing in life which made living worthwhile. You have no greater gift, darling. And every memory of your face, every cadence of your voice is joy whereon I shall feed hungrily in these coming months.

In another letter:

[I wonder] whether I could manage to go on living, to want to go on living if you did not care.

Does Honolulu need your phantom presence? Oh, my darling — without it, I could not live here at all. Your lips bring blessings — my beloved.

In December of that year, Mead was offered a position as assistant curator at the American Museum of Natural History, where she would go on to spend the rest of her career. She excitedly accepted, in large part so that she could at last be closer to Benedict, and moved to New York with her husband, Luther Cressman, firmly believing that the two relationships would neither harm nor contradict one another. As soon as the decision was made, she wrote to Benedict on January 7, 1926:

Your trust in my decision has been my mainstay, darling, otherwise I just couldn’t have managed. And all this love which you have poured out to me is very bread and wine to my direct need. Always, always I am coming back to you. I kiss your hair, sweetheart.

Four days later, Mead sends Benedict a poignant letter, reflecting on her two relationships and how love crystallizes of its own volition:

In one way this solitary existence is particularly revealing — in the way I can twist and change in my attitudes towards people with absolutely no stimulus at all except such as springs from within me. I’ll awaken some morning just loving you frightfully much in some quite new way and I may not have sufficiently rubbed the sleep from my eyes to have even looked at your picture. It gives me a strange, almost uncanny feeling of autonomy. And it is true that we have had this loveliness “near” together for I never feel you too far away to whisper to, and your dear hair is always just slipping through my fingers. . . . When I do good work it is always always for you … and the thought of you now makes me a little unbearably happy.

Five weeks later, in mid-February, Mead and Benedict begin planning a three-week getaway together, which proves, thanks to their husbands’ schedules, to be more complicated than the two originally thought. Exasperated over all the planning, Margaret writes Ruth:

I’ll be so blinded by looking at you, I think now it won’t matter — but the lovely thing about our love is that it will. We aren’t like those lovers of Edward’s “now they are sleeping cheek to cheek” etc. who forgot all the things their love had taught them to love — Precious, precious. I kiss your hair.

By mid-March, Mead is once again firmly rooted in her love for Benedict:

I feel immensely freed and sustained, the dark months of doubt washed away, and that I can look you gladly in the eyes as you take me in your arms. My beloved! My beautiful one. I thank God you do not try to fence me off, but trust me to take life as it comes and make something of it. With that trust of yours I can do anything — and come out with something precious saved. Sweet, I kiss your hands.

As the summer comes, Mead finds herself as in love with Benedict as when they first met six years prior, writing in a letter dated August 26, 1926:

Ruth dearest, I am very happy and an enormous number of cobwebs seem to have been blown away in Paris. I was so miserable that last day, I came nearer doubting than ever before the essentially impregnable character of our affection for each other. And now I feel at peace with the whole world. You may think it is tempting the gods to say so, but I take all this as high guarantee of what I’ve always temperamentally doubted — the permanence of passion — and the mere turn of your head, a chance inflection of your voice have just as much power to make the day over now as they did four years ago. And so just as you give me zest for growing older rather than dread, so also you give me a faith I never thought to win in the lastingness of passion. I love you, Ruth.

In September of 1928, as Mead travels by train to marry her second husband after her first marriage crumbled, another bittersweet letter to Ruth leaves us speculating about what might have been different had the legal luxuries of modern love been a reality in Mead’s day, making it possible for her and Ruth to marry and formalize their steadfast union under the law:

Darling, […] I’ve slept mostly today trying to get rid of this cold and not to look at the country which I saw first from your arms. Mostly, I think I’m a fool to marry anyone. I’ll probably just make a man and myself unhappy. Right now most of my daydreams are concerned with not getting married at all. I wonder if wanting to marry isn’t just another identification with you, and a false one. For I couldn’t have taken you away from Stanley and you could take me away from [Reo] — there’s no blinking that. […] Beside the strength and permanence and all enduring feeling which I have for you, everything else is shifting sand. Do you mind terribly when I say these things? You mustn’t mind — ever — anything in the most perfect gift God has given me. The center of my life is a beautiful walled place, if the edges are a little weedy and ragged — well, it’s the center which counts — My sweetheart, my beautiful, my lovely one. Your Margaret

By 1933, despite the liberal arrangements of her marriage, Mead felt that it forcibly squeezed out of her the love she had for Benedict. In a letter to Ruth from April 9, she reflects on those dynamics and gasps at the relief of choosing to break free of those constraints and being once again free to love fully:

Having laid aside so much of myself, in response to what I mistakenly believed was the necessity of my marriage I had no room for emotional development. … Ah, my darling, it is so good to really be all myself to love you again. . . . The moon is full and the lake lies still and lovely — this place is like Heaven — and I am in love with life. Goodnight, darling.

Over the years that followed, both Margaret and Ruth explored the boundaries of their other relationships, through more marriages and domestic partnerships, but their love for each other only continued to grow. In 1938, Mead captured it beautifully by writing of “the permanence of [their] companionship.” Mead and her last husband, Gregory Bateson, named Benedict the guardian of their daughter. The two women shared their singular bond until Benedict’s sudden death from a heart attack in 1948. In one of her final letters, Mead wrote:

Always I love you and realize what a desert life might have been without you.

See more of their gorgeous correspondence here .

ALLEN GINSBERG AND PETER ORLOVSKY

Their letters, filled with typos, missing punctuation, and the grammatical oddities typical of writing propelled by bursts of intense emotion rather than literary precision, are absolutely beautiful.

In a letter from January 20, 1958, Ginsberg writes to Orlovsky from Paris, recounting a visit with his close friend and fellow beatnik, William S. Burroughs , another icon of literature’s gay subculture:

Dear Petey: O Heart O Love everything is suddenly turned to gold! Don’t be afraid don’t worry the most astounding beautiful thing has happened here! I don’t know where to begin but the most important. When Bill [ ed: William S. Burroughs ] came I, we, thought it was the same old Bill mad, but something had happened to Bill in the meantime since we last saw him . . . . but last night finally Bill and I sat down facing each other across the kitchen table and looked eye to eye and talked, and I confessed all my doubt and misery — and in front of my eyes he turned into an Angel! What happened to him in Tangiers this last few months? It seems he stopped writing and sat on his bed all afternoons thinking and meditating alone & stopped drinking — and finally dawned on his consciousness, slowly and repeatedly, every day, for several months — awareness of “a benevolent sentient (feeling) center to the whole Creation” — he had apparently, in his own way, what I have been so hung up in myself and you, a vision of big peaceful Lovebrain. . . . I woke up this morning with great bliss of freedom & joy in my heart, Bill’s saved, I’m saved, you’re saved, we’re all saved, everything has been all rapturous ever since — I only feel sad that perhaps you left as worried when we waved goodby and kissed so awkwardly — I wish I could have that over to say goodby to you happier & without the worries and doubts I had that dusty dusk when you left… — Bill is changed nature, I even feel much changed, great clouds rolled away, as I feel when you and I were in rapport, well, our rapport has remained in me, with me, rather than losing it, I’m feeling to everyone, something of the same as between us.

A couple of weeks later, in early February, Orlovsky sends a letter to Ginsberg from New York, in which he writes with beautiful prescience:

…dont worry dear Allen things are going ok — we’ll change the world yet to our dessire — even if we got to die — but OH the world’s got 25 rainbows on my window sill. . . .

As soon as he receives the letter the day after Valentine’s Day, Ginsberg writes back, quoting Shakespeare like only a love-struck poet would:

I have been running around with mad mean poets & world-eaters here & was longing for kind words from heaven which you wrote, came as fresh as a summer breeze & “when I think on thee dear friend / all loses are restored & sorrows end,” came over & over in my mind — it’s the end of a Shakespeare Sonnet — he must have been happy in love too. I had never realized that before. . . . Write me soon baby, I’ll write you big long poem I feel as if you were god that I pray to — Love, Allen

In another letter sent nine days later, Ginsberg writes:

I’m making it all right here, but I miss you, your arms & nakedness & holding each other — life seems emptier without you, the soulwarmth isn’t around. . . .

Citing another conversation he had had with Burroughs, he goes on to presage the enormous leap for the dignity and equality of love that we’ve only just seen more than half a century after Ginsberg wrote this:

Bill thinks new American generation will be hip & will slowly change things — laws & attitudes, he has hope there — for some redemption of America, finding its soul. . . . — you have to love all life, not just parts, to make the eternal scene, that’s what I think since we’ve made it, more & more I see it isn’t just between us, it’s feeling that can [be] extended to everything. Tho I long for the actual sunlight contact between us I miss you like a home. Shine back honey & think of me.

He ends the letter with a short verse:

Goodbye Mr. February. as tender as ever swept with warm rain love from your Allen

EDNA ST. VINCENT MILLAY AND EDITH WYNN MATTHISON

Listen; if ever in my letters to you, or in my conversation, you see a candor that seems almost crude, — please know that it is because when I think of you I think of real things, & become honest, — and quibbling and circumvention seem very inconsiderable.

In another, she pleads:

I will do whatever you tell me to do. … Love me, please; I love you. I can bear to be your friend. So ask of me anything. … But never be ‘tolerant,’ or ‘kind.’ And never say to me again — don’t dare to say to me again — ‘Anyway, you can make a trial’ of being friends with you! Because I can’t do things that way. … I am conscious only of doing the thing that I love to do — that I have to do — and I have to be your friend.

In yet another, Millay articulates brilliantly the “proud surrender” at the heart of every materialized infatuation and every miracle of “real, honest, complete love” :

You wrote me a beautiful letter, — I wonder if you meant it to be as beautiful as it was. — I think you did; for somehow I know that your feeling for me, however slight it is, is of the nature of love. … nothing that has happened to me for a long time has made me so happy as I shall be to visit you sometime. — You must not forget that you spoke of that, — because it would disappoint me cruelly. … I shall try to bring a few quite nice things with me; I will get together all that I can, and then when you tell me to come, I will come, by the next train, just as I am. This is not meekness, be assured; I do not come naturally by meekness; know that it is a proud surrender to you; I don’t talk like that to many people. With love, Vincent Millay

ELEANOR ROOSEVELT AND LORENA HICKOK

But her personal life has been the subject of lasting controversy.

In the summer of 1928, Roosevelt met journalist Lorena Hickok , whom she would come to refer to as Hick. The thirty-year relationship that ensued has remained the subject of much speculation, from the evening of FDR’s inauguration, when the First Lady was seen wearing a sapphire ring Hickok had given her, to the opening up of her private correspondence archives in 1998. Though many of the most explicit letters had been burned, the 300 published in Empty Without You: The Intimate Letters Of Eleanor Roosevelt And Lorena Hickok ( public library ) — at once less unequivocal than history’s most revealing woman-to-woman love letters and more suggestive than those of great female platonic friendships — strongly indicate the relationship between Roosevelt and Hickok had been one of great romantic intensity.

On March 5, 1933, the first evening of FDR’s inauguration, Roosevelt wrote Hick:

Hick my dearest– I cannot go to bed tonight without a word to you. I felt a little as though a part of me was leaving tonight. You have grown so much to be a part of my life that it is empty without you.

Then, the following day:

Hick, darling Ah, how good it was to hear your voice. It was so inadequate to try and tell you what it meant. Funny was that I couldn’t say je t’aime and je t’adore as I longed to do, but always remember that I am saying it, that I go to sleep thinking of you.

And the night after:

Hick darling All day I’ve thought of you & another birthday I will be with you, & yet tonite you sounded so far away & formal. Oh! I want to put my arms around you, I ache to hold you close. Your ring is a great comfort. I look at it & think “she does love me, or I wouldn’t be wearing it!”

And in yet another letter:

I wish I could lie down beside you tonight & take you in my arms.

Hick herself responded with equal intensity. In a letter from December 1933, she wrote:

I’ve been trying to bring back your face — to remember just how you look. Funny how even the dearest face will fade away in time. Most clearly I remember your eyes, with a kind of teasing smile in them, and the feeling of that soft spot just north-east of the corner of your mouth against my lips.

Granted, human dynamics are complex and ambiguous enough even for those directly involved, making it hard to assume anything with absolute certainty from the sidelines of an epistolary relationship long after the correspondents’ deaths. But wherever on the spectrum of the platonic and romantic the letters in Empty Without You may fall, they offer a beautiful record of a tender, steadfast, deeply loving relationship between two women who meant the world to one another, even if the world never quite condoned or understood their profound connection.

OSCAR WILDE AND SIR ALFRED “BOSIE” DOUGLAS

In June of 1891, Wilde met Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas, a 21-year-old Oxford undergraduate and talented poet, who would come to be the author’s own Dorian Gray — his literary muse, his evil genius, his restless lover. It was during the course of their affair that Wilde wrote Salomé and the four great plays which to this day endure as the cornerstones of his legacy. Their correspondence, collected Oscar Wilde: A Life in Letters ( public library ), makes for an infinitely inspired addition to the most beautiful love letters exchanged between history’s greatest creative and intellectual power couples.

In January of 1893, Wilde writes to Bosie:

My Own Boy, Your sonnet is quite lovely, and it is a marvel that those red rose-leaf lips of yours should be made no less for the madness of music and song than for the madness of kissing. Your slim gilt soul walks between passion and poetry. I know Hyacinthus, whom Apollo loved so madly, was you in Greek days. Why are you alone in London, and when do you go to Salisbury? Do go there to cool your hands in the grey twilight of Gothic things, and come here whenever you like. It is a lovely place and lacks only you; but go to Salisbury first. Always, with undying love, yours, Oscar

In early March of 1893, Wilde channels love’s exasperating sense of urgency:

Dearest of All Boys — Your letter was delightful — red and yellow wine to me — but I am sad and out of sorts — Bosie — you must not make scenes with me — they kill me — they wreck the loveliness of life — I cannot see you , so Greek and gracious, distorted with passion; I cannot listen to your curved lips saying hideous things to me — don’t do it — you break my heart — I’d sooner be rented* all day, than have you bitter, unjust, and horrid — horrid. I must see you soon — you are the divine thing I want — the thing of grace and genius — but but I don’t know how to do it — Shall I come to Salisbury — ? There are many difficulties — my bill here is £49 for a week! I have also got a new sitting-room over the Thames — but you, why are you not here, my dear, my wonderful boy — ? I fear I must leave; no money, no credit, and a heart of lead — Ever your own, Oscar

* “renter” was slang for male prostitute in London

Their affair was intense, bustling with dramatic tempestuousness, but underpinning it was a profound and genuine love. In a letter from late December of 1893, after a recent rift, Wilde writes to Douglas:

My dearest Boy, Thanks for your letter. I am overwhelmed by the wings of vulture creditors, and out of sorts, but I am happy in the knowledge that we are friends again, and that our love has passed through the shadow and the light of estrangement and sorrow and come out rose-crowned as of old. Let us always be infinitely dear to each other, as indeed we have been always. […] I think of you daily, and am always devotedly yours. Oscar

In July of the following year, Wilde writes:

My own dear Boy, I hope the cigarettes arrived all right. I lunched with Gladys de Grey, Reggie and Aleck York there. They want me to go to Paris with them on Thursday: they say one wears flannels and straw hats and dines in the Bois, but, of course, I have no money, as usual, and can’t go. Besides, I want to see you. It is really absurd. I can’t live without you . You are so dear, so wonderful. I think of you all day long, and miss your grace, your boyish beauty, the bright sword-play of your wit, the delicate fancy of your genius, so surprising always in its sudden swallow-flights towards north and south, towards sun and moon — and, above all, yourself. The only thing that consoles me is what Sybil of Mortimer Street (whom mortals call Mrs. Robinson) said to me*. If I could disbelieve her I would, but I can’t, and I know that early in January you and I will go away together for a long voyage, and that your lovely life goes always hand in hand with mine. My dear wonderful boy, I hope you are brilliant and happy. I went to Bertie, today I wrote at home, then went and sat with my mother. Death and Love seem to walk on either hand as I go through life: they are the only things I think of, their wings shadow me. London is a desert without your dainty feet… Write me a line and take all my love — now and for ever. Always, and with devotion — but I have no words for how I love you. Oscar

* The fortuneteller’s prophesy apparently came true — Wilde and Douglas travelled to Algiers together the following January.

In 1895, at the height of his literary success, with his masterpiece The Importance of Being Earnest drawing continuous acclaim across the stages of London, Wilde had Douglas’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry, prosecuted for libel. But the evidence unearthed during the trial led to Wilde’s own arrest on charges of “gross indecency” with members of the same sex. Two more trials followed, after which he was sentenced for two years of “hard labor” in prison. On April 29 of that year, having hit emotional and psychological rock-bottom, his reputation ruined and his health deteriorating, Wilde wrote to Douglas on the eve of the final trial:

My dearest boy, This is to assure you of my immortal, my eternal love for you. Tomorrow all will be over. If prison and dishonour be my destiny, think that my love for you and this idea, this still more divine belief, that you love me in return will sustain me in my unhappiness and will make me capable, I hope, of bearing my grief most patiently. Since the hope, nay rather the certainty, of meeting you again in some world is the goal and the encouragement of my present life, ah! I must continue to live in this world because of that.

Another letter, written on August 31, 1897, shortly after Wilde’s release from prison, reads:

Café Suisse, Dieppe Tuesday, 7:30 My own Darling Boy, I got your telegram half an hour ago, and just send a line to say that I feel that my only hope of again doing beautiful work in art is being with you. It was not so in the old days, but now it is different, and you can really recreate in me that energy and sense of joyous power on which art depends. Everyone is furious with me for going back to you, but they don’t understand us. I feel that it is only with you that I can do anything at all. Do remake my ruined life for me, and then our friendship and love will have a different meaning to the world. I wish that when we met at Rouen we had not parted at all. There are such wide abysses now of space and land between us. But we love each other. Goodnight, dear. Ever yours, Oscar

But perhaps the most eloquent articulation of their relationship comes from a letter Wilde wrote to Leonard Smithers — a Sheffield solicitor with a side business of printing erotica, who became the only publisher interested in Wilde’s books in his post-prison years — on October 1, 1897:

How can you keep on asking is Lord Alfred Douglas in Naples? You know quite well he is — we are together. He understands me and my art, and loves both. I hope never to be separated from him. He is a most delicate and exquisite poet, besides — far the finest of all the young poets in England. You have got to publish his next volume; it is full of lovely lyrics, flute-music and moon-music, and sonnets in ivory and gold. He is witty, graceful, lovely to look at, lovable to be with. He has also ruined my life, so I can’t help loving him — it is the only thing to do.

More of their exquisite correspondence appears in Oscar Wilde: A Life in Letters , but that one sentence alone — “He understands me and my art, and loves both.” — is an immeasurably beautiful addition to history’s most profound definitions of love , a sublime manifestation of the highest hope one creative soul can have for a union with another.

— Published February 14, 2014 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2014/02/14/greatest-queer-love-letters/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, allen ginsberg culture edna st. vincent millay eleanor roosevelt letters lgbt love love letters margaret mead oscar wilde peter orlovsky psychology virginia woolf vita sackville-west, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

- The Open University

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

What LGBTQ+ Relationships Can Teach Us About Love

Find out more about The Open University's Open degree

As we reach LGBTQ+ history month, there’s no better time to look back on the lessons we’ve learnt along the way – not least on our ability to bring about rapid social, cultural and legal changes via respectful debate, patience and listening to the views or our opponents.

I’d also like to take this opportunity to acknowledge how, in doing so, the LGBTQ+ community has learnt a lot about what makes relationships work, and researchers now have hundreds of studies under their belt for why this is.

Download the Paired app for LGBTQ+ dating and relationship advice , daily questions, quizzes and more.

A study published by the Open University has found that gay couples are likely to be happier in their relationships than their heterosexual counterparts and several reasons have been posed, from less gender stereotypes featuring in the relationship to a historical predisposition for inner reflexiveness.

Let’s take a look at few more lessons to learn from our same-sex counterparts.

Lesson 1: A fairer split of household jobs

Gender stereotypes can be a breeding ground for dissatisfaction in relationships. Inequalities in pay, expectations around childcare and historical perceptions of gender roles at home can all cause resentment, miscommunication and tension.

According to a study authored by Daniel Carlson and colleagues, relationship quality and stability is generally highest when couples are happy with their divisions of labor and find them equitable and fair. This is often the case with same-sex couples. In their study, Abbie E. Goldberg and Maureen Perry-Jenkins found that same-sex couples are much more willing to share traditionally ‘masculine’ or ‘feminine’ roles at home alongside routine tasks.

In contrast, research on heterosexual relationships consistently shows that the responsibility for domestic chores falls disproportionately onto women. Men are far more likely to overestimate the time they spend on chores, while women underestimate their time.

LGBTQ+ parents are also more likely to mutually interact with their children, whereas in heterosexual relationships, parentood can highlight further gender divides in the division of household jobs. While women are now an essential part of the labour market and often work as many hours as their male partners, they are still expected to put in a ‘second shift’ back at home.

In essence, LGBTQ+ couples don’t have cultural norms, predefined gender roles or stereotypes to fall back on when it comes to splitting labor at home, so they must find a balance that feels fair to them, talk through their preferences, and negotiate their individual schedules and commitments to agree to an even split.

Lesson 2: Celebrate your sexuality

LGBTQ+ people have faced centuries of prejudice – and still face it today, even from friends, family and work colleagues. Yet, the fight for equality has pushed LGBTQ+ communities to truly celebrate their sexuality and gender, take pride in it and explore what it really means – something heterosexual or cisgender couples may take for granted.

One caveat here is that this celebration of sexuality doesn't always apply to the public arena. The Open University study found that LGBTQ+ partners were less likely to show affection in public, often caused by fears around social stigma and personal safety. Living in a society where your wellbeing is at risk takes bravery and courage to be who you are. It also requires you to own your vulnerabilities and be sensitive to those of your partner.

Heterosexual couples seldom, if ever, sit down and talk about their sexuality or how they celebrate this in public. Yet being attentive to a partner’s sense of personal comfort around public displays of affection (PDA) is beneficial for any relationship, whatever the couple’s sexuality.

Lesson 3: Think outside the box

As the research on gender roles suggests, outdated socio-cultural norms can structure the couple dynamic in heterosexual relationships resulting in imbalances in power and unfairness in the domestic division of labour. This is likely to cause resentment and conflict.

LGBTQ+ couples, on the other hand, are more willing to think outside the box of what a typical relationship should look like and be more open to non-traditional relationship models. They are more likely to resist social norms in their partnerships and embrace polyamory and non-monogamy, for example, than heterosexual couples are.

The lack of social scripts and cultural templates give LGBTQ+ partners a chance to make their own rules. Not being bound to social expectations allows them to create a relationship of their own making rather than be limited by what they’ve been told it should be. LGBTQ+ partners can make their own traditions, celebrations and relationship priorities.

Heterosexual could perhaps take a leaf out the the LGBTQ+ relationship rule book or discard the book altogether. Psychologist and author Meg-John Barker suggests that all couples can rewrite the rules, for example practicing 'new monogamy', alternative commitment ceremonies, and different ways of understanding gender, and that this can generate novel ideas for managing conflict and improving their connection together.

Lesson 4: Establish boundaries

One of the most common causes of relationship dissatisfaction is frustration caused by uncommunicated boundaries and expectations. We often forget to have these discussions because our partner is supposed to already know and act on our needs and wants.

In our ‘Enduring Love?’ study, we found that acknowledging that a partner is not adept at mind-reading facilitated open communication that resulted in a greater sense of togetherness. Talking over and establishing healthy boundaries in a relationship created limits and guidelines which allowed both partners to feel comfortable.

LGBTQ+ couples are well practiced in working out boundaries in their relationships. This can open up the conversation around public displays of affection to be more attentive to a partner’s sense of self and emotional security, or start a discussion around the boundaries of consensual non-monogamous relationships.

A study by Colleen Hoff and Sean Beougher found that many gay couples spend time working out detailed agreements about what kinds of sexual contact are permissible outside the relationship, under what conditions or circumstances and how often. This fostered a sense of trust and openness in the relationship that extended beyond sex and intimacy.

Lesson 5. Communicate positively

While negativity bias can often make us focus on our weaknesses or irritations, the benefits of positive thinking can significantly improve our psychological and physical wellbeing.

According to a study led by Giuseppina Valle Holway, LGBTQ+ couples show a tendency to manage disagreements in a more positive way, being more likely to use praise and encouragement rather than criticism, blame or nagging – and are happier in return.

This corroborates other research which has shown that giving praise is a core factor in relationship happiness. One study revealed that couples who communicate partners’ achievements and strengths were more committed to each other, more hopeful of the future, and experienced a greater sense of intimacy. Plus, partners felt more confident and motivated to reciprocate these strengths in return. And Dr Terri Orbuch’s study of long-term couples, on the other hand, found that men were twice as likely to break up with their partners if they didn’t get affirmation often.

Lesson 6: Talk openly about sex

Studies show that heterosexual couples are particularly likely to believe that they “should” know all about each other, sexually, without discussing it. In fact, one of Dr. John Gottman’s laboratory studies found that when listening into heterosexual couple’s conversations, third parties couldn’t tell what heterosexual couples were discussing, even when the couples had been instructed to talk about sex.

Same-sex couples, on the other hand, tend to speak about their sexual wants and needs specifically, often, and throughout their relationship. They devote time and energy into de-stigmatizing sex, sexual activity and sexual body parts. They start from a position of wanting to learn about a partner’s eroticism and desires rather than taking them for granted. And this sexual conversation style results in more satisfying sex – emotionally and physically.

As sex writer Dan Savage says, gay couples often ask, “What are you into?” – these four "magic” words are something that most straight couples simply don’t use.

Lesson 7: Be reflexive

Because “taken for grantedness” is not an option that is available for LGBTQ+ couples, research by Jeffrey Weeks and colleagues has shown how they are more likely to think about what they’re doing and why they’re doing.

LGBTQ+ couples are therefore more reflexive, they actively and explicitly work through – together – how they want their relationship to work.

In their study of young same-sex couples’ decision-making around commitment ceremonies, Brian Heaphy and colleagues found that young LGBTQ+ people expressed highly emotional, rational and pragmatic reasons for committing rather than simply falling into the trope of marriage. As such, while they conformed to traditional relationship scripts in one way, they were also active and sometimes highly reflexive 'scripters' of convention. Being reflexive enabled them to craft the relationships that they chose rather than fall into the ones that were chosen for them.

LGBTQ+ couples’ openness and creativity may thus make them more amenable to change and adaptability, qualities that are crucial in long-term relationships. The absence of cultural scripts, and commitment to actively working at a relationship, may also explain why the ’Enduring Love?’ study also found that LGBTQ+ couples are happier in their relationships and with each other than their heterosexual counterparts.

This article was originally published on Paired.

Find out more

LGBTQ youth and homelessness: We can all make a difference

While so much progress has been made regarding the rights of the LGBTQ community, it might come as a surprise that young people in this community are at considerable risk of becoming homeless. Dr Mathijs Lucassen explores this issue and how we can overcome it.

Five things to know about being disabled and LGBTQ

Disabled people are often wrongly assumed not to have sexuality or interest in sex! Here, Jamie Hale reels off 5 things you need to know about being disabled and LGBTQ...

Why school-based sex education isn’t inclusive enough

Only a small minority of LGBT young people learn about sexual health in the classroom, which could put them at risk.

Cognition and gender development

This course taster is taken from the Open University’s ‘Child Development’ course (ED209). It is an extract from one of the four course text books (Banerjee, R. (2005) ‘Gender identity and the development of gender roles’, in Ding, S. and Littleton, K. S. (eds) Children’s Personal and Social Development, Oxford, Blackwell.) © Open University 2005

When do children develop a sense of gender?

Young children are flexible about their ideas of gender - but, for most, that flexibility soon vanishes. When do ideas about gender become fixed in children's minds?

Timeline: LGBTQ History

Explore some snapshots of LGBTQ history with our timeline.

Tumble And Twirl: David Bowie and gender transgression

Throughout his career, David Bowie has pushed at the edges and limits of the gender binary. Lisa Perrott offers a brief guide.

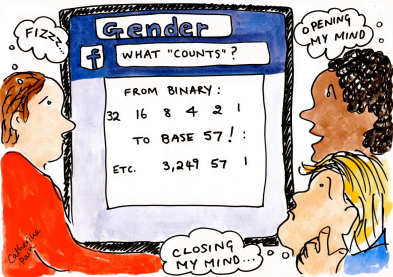

57 genders (and none for me?) - Part One

Meg Barker explores the world of Facebook gender categories, in the first of two posts.

Workshops on gender diversity – helping us move from insults to inclusion.

How can we tackle the bullying of transgender youth in schools? Can workshops on gender diversity help?

Why do transgender students need safe bathrooms?

Which bathroom transgender people use has become a flashpoint in a lot of educational institutions - and other public spaces are likely to follow. Alison Gash explains why it's important.

What's life like for Jordan's LGBTQ community?

Jordan removed legal punishments for same-gender relationships nearly two decades before the UK decriminalised consensual gay male intercourse. But day-to-day life for LGBTQ people in the country isn't easy. Nora B reports.

57 genders (and none for me?) - Part two

Meg Barker points to some of the problems with Facebook's new range of gender options.

Study a free course

Making sense of ourselves

This free course, Making sense of ourselves, introduces you to well-known psychological topics by asking and answering everyday questions, such as Why don’t we like one another? Why would I hang around with you? Do you see what I see? What’s the point of childhood? You’ll learn how psychologists can go about addressing these questions using ...

Starting with psychology

The most 'important and greatest puzzle' we face as humans is ourselves (Boring, 1950, p. 56). Humans are a puzzle, one that is complex, subtle and multi-layered, and it gets even more complicated as we evolve over time and change within different contexts. When answering the question 'what makes us who we are?' psychologists put forward a ...

Become an OU student

Ratings & comments, share this free course, copyright information, publication details.

- Originally published: Thursday, 4 February 2021

- Body text - Creative Commons BY-ND 4.0 : Originally published by Paired

- Image 'pink background, with silhouttes of people in front, shown in profile, different genders.' - Copyright free: Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

- Image 'LGBTQ flag at the top and below silhouttes in black of a wide variety of different figures..' - Copyright free: Image by blende12 from Pixabay

- Image 'a pair of wings, separated, in a rainbow of colours' - Copyright free: Image by Sabrina Schmidt from Pixabay

- Image 'two silver tin cans with a white string connecting them, with two white cartoon figures, no faces, by each can. ' - Copyright free: Image by Peggy und Marco Lachmann-Anke from Pixabay

- Image 'The word love in upper case, in rainbow colours' - Copyright free: Image by Alexandra_Koch from Pixabay

- Image 'two hands, palms up, holding a lace heart in LGBTQ rainbow colours' - Copyright free: Image by M Harris from Pixabay

- Image 'graphic of a hand wearing a rubber glove holding a sponge applying water to clean a surface' - Copyright free: Image by mohamed Hassan from Pixabay

- Image 'When do children develop a sense of gender?' - Brian Sawyer under Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 license

- Image 'Tumble And Twirl: David Bowie and gender transgression' - Jerome Coppee under CC-BY-SA licence under Creative-Commons license

- Image 'Workshops on gender diversity – helping us move from insults to inclusion.' - flickr under Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 license

- Image 'What's life like for Jordan's LGBTQ community?' - Bucketlisty Photos under Creative Commons BY-NC 4.0 license

- Image 'LGBTQ youth and homelessness: We can all make a difference' - Image by Taufiq Klinkenborg on pexels.com under Creative Commons BY-NC 4.0 license

- Image 'Why do transgender students need safe bathrooms?' - James Green under CC-BY-ND licence under Creative-Commons license

- Image 'Cognition and gender development' - Copyright: Open2 team

- Image 'Five things to know about being disabled and LGBTQ' - Maddie Blackburn under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

- Image 'Starting with psychology' - Copyright: Used with permission

- Image '57 genders (and none for me?) - Part One' - Catherine Pain under Creative-Commons license

- Image 'Timeline: LGBTQ History' - under Creative-Commons license

- Image 'Why school-based sex education isn’t inclusive enough' - Virhemarginaali Podcast under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

- Image '57 genders (and none for me?) - Part two' - Catherine Pain under Creative-Commons license

- Image 'Making sense of ourselves' - Copyright free

Rate and Review

Rate this article, review this article.

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

For further information, take a look at our frequently asked questions which may give you the support you need.

- Relationships

Two Decades of LGBTQ Relationships Research

To what extent is relationship science reflective of lgbtq+ experiences.

Posted September 29, 2022 | Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

- Why Relationships Matter

- Find a therapist to strengthen relationships

- While same-sex marriage has been legal in some jurisdictions for two decades, relationships research continues to focus on mixed-sex couples.

- A review of 2,181 relationship science articles published since 2001 found that 85.8% excluded LGBTQ+ relationships.

- Without LGBTQ+ relationships research, it is hard to provide empirically-supported advice to same-sex and gender-diverse relationships.

In 2014, I attended the annual meeting of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology—one of the largest annual social psychology conferences. The conference covers a wide range of topics and one of the sub-areas is Close Relationships, which hosts a wonderful pre-conference each year leading up to the larger event. As I found myself strolling through the poster presentations for this section of the conference, I began to notice that most of them were reporting the results of research conducted with mixed-sex and presumably heterosexual couples. The pattern became so apparent that I decided to review each poster a bit more systematically and to ask the presenters some standard questions about the demographics of their samples. I was able to visit 58 of the 71 posters listed on the program for the Close Relationships section—there were quite a few posters missing due to a horrendous winter storm that made the annual trip to SPSP impossible for many. Of the posters reviewed, only 15.5% included LGBTQ participants and only one study specifically focused on LGBTQ relationships. Following the conference, I wrote an article for the Relationships Research Newsletter published by the International Association for Relationships Research discussing the "state of LGBTQ-inclusive research methods" in the field of relationship science.

The following year, a somewhat more systematic approach to evaluating the inclusion of sexual minority couples in research was undertaken by Judith Andersen and Christopher Zou, who published their findings in the Health Science Journal . Their analysis focused on the inclusion of sexual minority couples in research relevant to relationships and health and they focused on publications indexed by Medline and PsychINFO between 2002-2012. Their results indicated that a striking 88.7% of the studies reviewed had excluded sexual minority couples from participating—meaning that even fewer of the papers in their sample were inclusive than my snapshot of the posters presented during the 2014 Close Relationships Poster Session.

Fast forward nearly another decade and the International Association for Relationship Research decided to launch two special issues of their flagship journals, Personal Relationships and the Journal of Social and Personal Relationships , dedicated to reviewing the last two decades of relationship science. Along with two other leading researchers in the area of LGBTQ+ relationships, I was invited to write a review focused on LGBTQ+ relationship science. The burning question in my mind was whether or not we would see a stark increase in inclusion as time progressed. After all, the two decades spanning 2002-2022 represent a time of significant advancements for LGBTQ+ civil rights, particularly those related to the legal recognition of same-sex relationships.

What Is the State of LGBTQ Inclusion in Relationships Research Today?

To answer this question, we gathered every single article published in Personal Relationships (PR) and the Journal of Social and Personal Relationships (JSPR) starting in 2002 until April 2021. This resulted in 2,181 articles; 1,392 articles from JPSR and 789 from PR. We used a variety of coding techniques, including automatic keyword coding and manual screening of articles, to identify which articles contained any information relevant to LGBTQ+ identities and relationships. Roughly 85.8% of these articles were excluded from further analysis as they did not contain any words relevant to sexual or gender minority identities or relationships. The remaining 329 articles were manually coded to identify how they handled issues related to sexual and gender identity . Some articles mentioned LGBTQ+ issues in their limitations section (n = 58), for example to state that future research should consider testing similar questions with a more inclusive and diverse sample. Another 42 articles explicitly stated that they excluded LGBTQ+ participants from their recruitment or analysis process, and while this may seem harsh, it still reflects a methodological improvement over the 1,852 articles that did not even provide adequate information to understand how the exclusion process took place. Some studies did include LGBTQ+ participants in their recruitment process and analyses, but often the sample sizes were small, meaning that no further efforts were taken to understand whether LGBTQ+ participants had unique experiences.

Ultimately, of the 2,181 articles published in these two journals between 2002 and April 2021, 92 articles, or 4.2%, presented LGBTQ-relevant information that we considered capable of providing empirical evidence concerning the lives and experiences of sexual and gender minorities within the context of close relationships. Thus, with only 4.2% of the articles being LGBTQ-relevant, our review of two decades of relationship science research did not seem to suggest that great improvement was occurring over time.

Has LGBTQ Inclusion Increased Over Time?

However, when we broke our data down into smaller periods, we did see a slight indication of improvement over time for the general inclusion of LGBTQ+ participants in relationship science published in these two journals. For example, research published in Personal Relationships climbed from roughly 2% of articles being LGBTQ-relevant between 2002 and 2006 to a peak of just over 4% in 2012-2015, a rate that either slightly decreased or remained constant for the final five-year period, 2016-2021. The Journal of Social and Personal Relationships had a somewhat higher inclusion rate over time, with roughly 3.5% of articles in 2002-2006 being LGBTQ-relevant, peaking at nearly 6% between 2007-2011, and then settling back between 4% and 5% for the periods ranging from 2012-2015 and 2016-2021. Despite these slight differences, overall, there was no significant difference between the proportion of articles considered LGBTQ-relevant in each of the two journals reviewed.

Additional Patterns of Inclusion and Exclusion

Most of the research in the review that was deemed "LGBTQ-relevant" tended to explore the LGBTQ+ community as a whole, rather than presenting studies that specifically explored the experiences of one identity group or another (e.g., lesbian women vs. gay men). Only one of the 92 articles exclusively focused on the experiences of bisexual individuals and 54.3% of the LGBTQ-relevant articles did not include bisexuals in their sample at all. The overall body of research also had an androcentric slant, such that 17.4% of the articles focused exclusively on sexual minority men while only 9.8% focused exclusively on sexual minority women.

Finally, although our interest was in exploring relationship science that was considered relevant to LGBTQ+ populations, a better descriptor would be LGBQ, as very few of the studies included transgender , non-binary, or gender-diverse relationship experiences. In total, 15 articles included transgender participants while only four included non-binary participants.

LGBTQ+ Specific Journals

Of course, this review focused on two of the leading relationship science journals and thus did not cover research published in other journals. Anecdotally, many researchers working in LGBTQ psychology and related areas note that when they try to publish in mainstream journals, reviewers often recommend that they send their LGBTQ-relevant research to more specialized, niche journals. Thus, there is likely more research on LGBTQ+ relationship experiences in journals such as Psychology & Sexuality , LGBT Health, Journal of Lesbian Studies, Journal of Homosexuality, and the APA Journal of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. However, none of these journals specifically focus on relationship science and may not be widely read by other scholars studying relationships specifically. While one of the benefits of LGBTQ-inclusive research is that it helps us to better understand the experiences within this specific population, such research also benefits the wider population, as often LGBTQ-inclusive research suggests new and novel questions that help to shed light on relationship experiences that are relevant to all individuals, regardless of sexual or gender identity.

Despite the indication that there is still a long way to go in terms of encouraging broad inclusion of LGBTQ+ experiences in mainstream relationship research, there were still many positive signs. The overall trajectory of inclusion appears to be increasing over time, conferences are beginning to include specific programming on how to increase the inclusivity of relationship research, and the editors of the special issues celebrating the past two decades of relationship science saw fit to include a review that was specific to LGBTQ+ relationship experiences. The review concluded by noting that we, the authors, were "looking forward to the next 20 years" of LGBTQ-inclusive relationship research, with a specific "focus on deciphering the minutiae of all the colourful intersection of identity that make up the true richness of human relationships."

Pollitt, A. M., Blair, K. L., & Lannutti, P. J. (2022). A review of two decades of LGBTQ‐inclusive research in JSPR and PR . Personal Relationships . https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12432

Andersen, J. P., & Zou, C. (2015). Exclusion of sexual minority couples from research. Health Science Journal, 9(6), 1.

Blair, K. L., McKenna, O., & Holmberg, D. (2022). On guard: Public versus private affection-sharing experiences in same-sex, gender-diverse, and mixed-sex relationships . Journal of Social and Personal Relationships , 02654075221090678.

Karen Blair, Ph.D. , is an assistant professor of psychology at Trent University. She researches the social determinants of health throughout the lifespan within the context of relationships.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Yale @RT books

We've moved! Yale Artbooks blog posts are now available on blog.yalebooks.com

Liberating Love: Anthony Friedkin’s “The Gay Essay” / Interview with Nayland Blake by David Ebony

David Ebony—

Coinciding with this development, an exhibition of Anthony Friedkin’s photographs in a series titled “The Gay Essay,” and an accompanying catalogue , examine the nascent gay liberation movement on the West Coast in the late 1960s and early ’70s. On view at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, through January 11, 2015, “Anthony Friedkin: The Gay Essay” features 75 vintage photographs that constitute a personal account of the times and an intimate view of the gay scene. Organized by museum curator Julian Cox, the exhibition is the first to include all of the photos in the series, which Friedkin began in 1969, at age 19. At that time, homosexual acts were illegal in every state except Illinois.

Anthony Friedkin Self-Portrait with Leica M4 Camera, ca. 1970 Gelatin Silver Print, 10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm) Collection of the artist

“The mistreatment of people in the gay community was one of the initial reasons that I wanted to photograph The Gay Essay ,” Friedkin writes in the book’s afterword. “It seemed tragically unfair and deplorable that people were hostile and threatening to others based on their sexual identity.”

The Los Angeles photographer, known for images of surfers and surfing culture, had in mind at the time an ambitious endeavor to be the first to document the local gay scene. While the mainstream press had previously covered certain aspects of the gay community, it rarely reflected an objective, let alone sympathetic, point of view. Friedkin befriended Morris Kight and Don Kilhhefner, who were then directors of the Gay Community Services Center in L.A., and through them gained access to the gay activist circles at the heart of the budding movement. Eventually embraced by the gay community, and using a compact and portable 35mm Leica M4 camera, Friedkin was able to photograph politically charged events as well as very personal, intimate moments.

Anthony Friedkin Don Kilhefner and Morris Kight at the Gay Community Services Center, Los Angeles, 1972 Gelatin silver print 14 × 11 in. (35.6 × 27.9 cm) Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon

To further explore Friedkin’s exemplary work and discuss its significance today, I recently met at New York’s International Center of Photography with Nayland Blake, an artist, writer and ICP instructor, who, along with Friedkin, Cox and Eileen Myles, contributed to the book. In his inspired and inspiring essay, Blake suggests an underlying story in Friedkin’s photographs that conveys a sense of joy and love through intimate images of interracial and same-sex couples, which may be as profound and revolutionary as the more overt pictures of political strife and protest.

David Ebony You mention in your essay that struggle and pain as subject matter for documentary photos is more appropriate than joy or pleasure. Why do you think that is the case?

Nayland Blake I think that the documentary tradition is one that privileges depictions of suffering and pain. I don’t necessarily agree with it. It’s especially problematic for social movements that are trying to argue for pleasure when the depiction of pleasure is seen as somehow less serious than images of pain. Certainly art history of past 20 years or more has not been one of valorizing depictions of pleasure or connection. That’s what I was thinking about in the essay.

One the powerful things about the Friedkin photographs is that while they show moments of struggle, like the bombed out MCC [the gay-friendly Metropolitan Community Church in Los Angeles, which was attacked in 1973, an apparent act of arson] and the various community leaders and protests, there are more casual and intimate scenes depicted. We would expect to see images of conflict in mainstream magazines like Life or Time. But in “The Gay Essay” there are pictures of people whose only historical role is that they were having a good time and in a unique way. That’s a real strength in the work.

Anthony Friedkin The Reverend Troy Perry, Gay Activist, in His Burnt Down Church, Los Angeles, 1973 Gelatin silver print 14 × 11 in. (35.6 × 27.9 cm) Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco Anonymous gift in honor of Sheila Glassman

Ebony What is the importance of The Gay Essay today?

Blake I think its importance has to do with the fact that Friedkin manages to connect with people through the work without a lot of editorializing. He speaks and writes movingly about the project as being centered on the idea of acceptance into a community. It’s rare in a photographer’s published works that you get a sense that he or she understands the community and has had the privilege of being accepted into it. Friedkin’s role as photographer was not exactly that of a participant. But normally the approach at the time would be much more anthropological—capturing images of these people and events to bring to another audience. But these pictures have a very different tone.

Anthony Friedkin May Doll, Gay Liberation Parade, Hollywood, 1972 Gelatin silver print 14 × 11 in. (35.6 × 27.9 cm) Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco Anonymous gift

Ebony What other aspects of Friedkin’s work set it apart from other photographs of the period?

Blake It has to do with a different kind of art history, one that’s not so grandstanding. Today, we’re accustomed to cameras being ubiquitous. We’re more used to seeing casual pictures coming out of various communities or groups of friends. But these photographs drew on that spirit long before their time. That’s one of the reasons why there’s so much renewed interest in them now. This idea struck me when I compared them with Bill Eppridge’s pictures for the groundbreaking 1964 Life article, “Homosexuality in America.” Eppridge’s images are very much those of an outsider having something to say about a community and trying to find the historical story. By contrast, Friedkin wasn’t so much aiming to tell the “big tale” as he was trying to experience the personalities within the scene. In some of the most memorable images, like those of two women just hanging out on the street, he’s talking about flirtation and sexual attraction. He addresses these kinds of small moments that are so often left out of the discussion. It’s the moment when you feel safe enough to express your desire and your pleasure.

Anthony Friedkin Couple in Front of Church, Los Angeles, 1970 Gelatin silver print 14 × 11 in. (35.6 × 27.9 cm) Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco Anonymous gift

Ebony What were the differences between early gay rights activism on the West Coast and the East Coast?

Blake First, you have to break down the West Coast to Los Angeles and San Francisco. They were very different scenes. L.A. was the initial home of the Mattachine Society in the 1950s, the earliest homophile/homosexual movement. The political issues at stake were generally more socially based, like police entrapment. There was an anonymous gay population cruising in parks that was a constant police target. Friedkin’s San Francisco photos are not so overtly political. The scene there was more about a kind of hippie, gender-queer, performance-art kind of thing. The emphasis was on freedom of personal expression and sexual identity. You can see it in his photos of performers like Divine and the Cockettes. You might say the politics were richer and more esthetic, related to personal presentation and living. By comparison, the East Coast gay liberation movement seems to me to have been more closely allied with the New Left, closer to the student protest movements of the time.