Get 25% OFF new yearly plans in our Spring Sale

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

Hero's Journey 101: How to Use the Hero's Journey to Plot Your Story

Dan Schriever

How many times have you heard this story? A protagonist is suddenly whisked away from their ordinary life and embarks on a grand adventure. Along the way they make new friends, confront perils, and face tests of character. In the end, evil is defeated, and the hero returns home a changed person.

That’s the Hero’s Journey in a nutshell. It probably sounds very familiar—and rightly so: the Hero’s Journey aspires to be the universal story, or monomyth, a narrative pattern deeply ingrained in literature and culture. Whether in books, movies, television, or folklore, chances are you’ve encountered many examples of the Hero’s Journey in the wild.

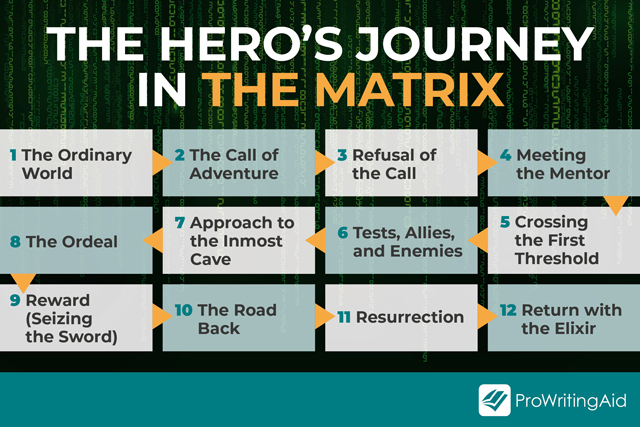

In this post, we’ll walk through the elements of the Hero’s Journey step by step. We’ll also study an archetypal example from the movie The Matrix (1999). Once you have mastered the beats of this narrative template, you’ll be ready to put your very own spin on it.

Sound good? Then let’s cross the threshold and let the journey begin.

What Is the Hero’s Journey?

The 12 stages of the hero’s journey, writing your own hero’s journey.

The Hero’s Journey is a common story structure for modeling both plot points and character development. A protagonist embarks on an adventure into the unknown. They learn lessons, overcome adversity, defeat evil, and return home transformed.

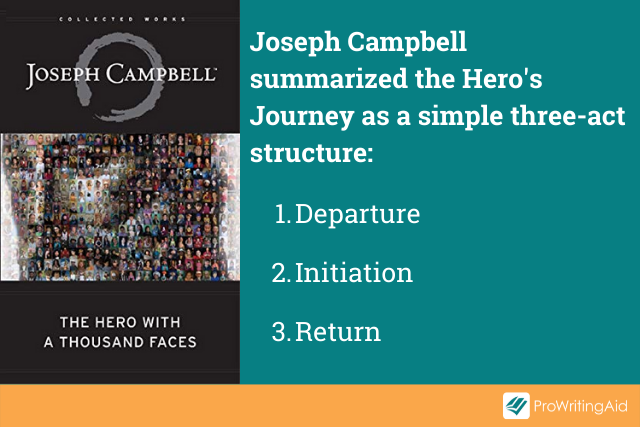

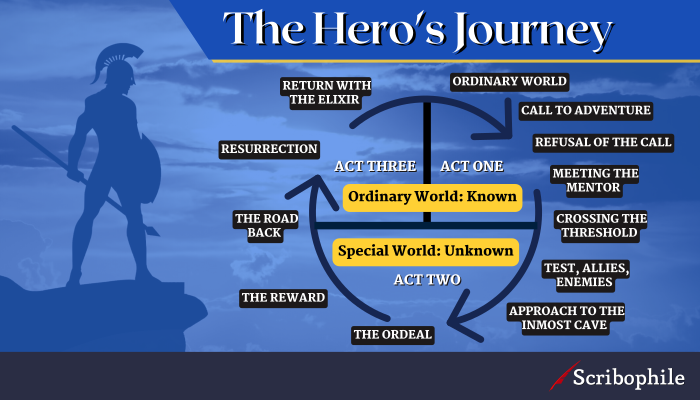

Joseph Campbell , a scholar of literature, popularized the monomyth in his influential work The Hero With a Thousand Faces (1949). Looking for common patterns in mythological narratives, Campbell described a character arc with 17 total stages, overlaid on a more traditional three-act structure. Not all need be present in every myth or in the same order.

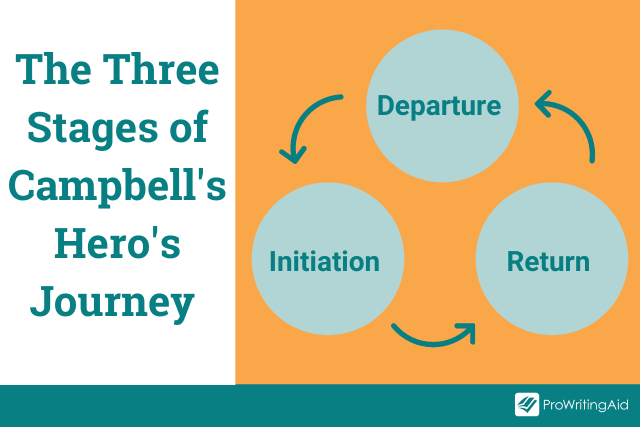

The three stages, or acts, of Campbell’s Hero’s Journey are as follows:

1. Departure. The hero leaves the ordinary world behind.

2. Initiation. The hero ventures into the unknown ("the Special World") and overcomes various obstacles and challenges.

3. Return. The hero returns in triumph to the familiar world.

Hollywood has embraced Campbell’s structure, most famously in George Lucas’s Star Wars movies. There are countless examples in books, music, and video games, from fantasy epics and Disney films to sports movies.

In The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers (1992), screenwriter Christopher Vogler adapted Campbell’s three phases into the "12 Stages of the Hero’s Journey." This is the version we’ll analyze in the next section.

For writers, the purpose of the Hero’s Journey is to act as a template and guide. It’s not a rigid formula that your plot must follow beat by beat. Indeed, there are good reasons to deviate—not least of which is that this structure has become so ubiquitous.

Still, it’s helpful to master the rules before deciding when and how to break them. The 12 steps of the Hero's Journey are as follows :

- The Ordinary World

- The Call of Adventure

- Refusal of the Call

- Meeting the Mentor

- Crossing the First Threshold

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies

- Approach to the Inmost Cave

- Reward (Seizing the Sword)

- The Road Back

- Resurrection

- Return with the Elixir

Let’s take a look at each stage in more detail. To show you how the Hero’s Journey works in practice, we’ll also consider an example from the movie The Matrix (1999). After all, what blog has not been improved by a little Keanu Reeves?

#1: The Ordinary World

This is where we meet our hero, although the journey has not yet begun: first, we need to establish the status quo by showing the hero living their ordinary, mundane life.

It’s important to lay the groundwork in this opening stage, before the journey begins. It lets readers identify with the hero as just a regular person, “normal” like the rest of us. Yes, there may be a big problem somewhere out there, but the hero at this stage has very limited awareness of it.

The Ordinary World in The Matrix :

We are introduced to Thomas A. Anderson, aka Neo, programmer by day, hacker by night. While Neo runs a side operation selling illicit software, Thomas Anderson lives the most mundane life imaginable: he works at his cubicle, pays his taxes, and helps the landlady carry out her garbage.

#2: The Call to Adventure

The journey proper begins with a call to adventure—something that disrupts the hero’s ordinary life and confronts them with a problem or challenge they can’t ignore. This can take many different forms.

While readers may already understand the stakes, the hero is realizing them for the first time. They must make a choice: will they shrink from the call, or rise to the challenge?

The Call to Adventure in The Matrix :

A mysterious message arrives in Neo’s computer, warning him that things are not as they seem. He is urged to “follow the white rabbit.” At a nightclub, he meets Trinity, who tells him to seek Morpheus.

#3: Refusal of the Call

Oops! The hero chooses option A and attempts to refuse the call to adventure. This could be for any number of reasons: fear, disbelief, a sense of inadequacy, or plain unwillingness to make the sacrifices that are required.

A little reluctance here is understandable. If you were asked to trade the comforts of home for a life-and-death journey fraught with peril, wouldn’t you give pause?

Refusal of the Call in The Matrix :

Agents arrive at Neo’s office to arrest him. Morpheus urges Neo to escape by climbing out a skyscraper window. “I can’t do this… This is crazy!” Neo protests as he backs off the ledge.

#4: Meeting the Mentor

Okay, so the hero got cold feet. Nothing a little pep talk can’t fix! The mentor figure appears at this point to give the hero some much needed counsel, coaching, and perhaps a kick out the door.

After all, the hero is very inexperienced at this point. They’re going to need help to avoid disaster or, worse, death. The mentor’s role is to overcome the hero’s reluctance and prepare them for what lies ahead.

Meeting the Mentor in The Matrix :

Neo meets with Morpheus, who reveals a terrifying truth: that the ordinary world as we know it is a computer simulation designed to enslave humanity to machines.

#5: Crossing the First Threshold

At this juncture, the hero is ready to leave their ordinary world for the first time. With the mentor’s help, they are committed to the journey and ready to step across the threshold into the special world . This marks the end of the departure act and the beginning of the adventure in earnest.

This may seem inevitable, but for the hero it represents an important choice. Once the threshold is crossed, there’s no going back. Bilbo Baggins put it nicely: “It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you don't keep your feet, there's no knowing where you might be swept off to.”

Crossing the First Threshold in The Matrix :

Neo is offered a stark choice: take the blue pill and return to his ordinary life none the wiser, or take the red pill and “see how deep the rabbit hole goes.” Neo takes the red pill and is extracted from the Matrix, entering the real world .

#6: Tests, Allies, and Enemies

Now we are getting into the meat of the adventure. The hero steps into the special world and must learn the new rules of an unfamiliar setting while navigating trials, tribulations, and tests of will. New characters are often introduced here, and the hero must navigate their relationships with them. Will they be friend, foe, or something in between?

Broadly speaking, this is a time of experimentation and growth. It is also one of the longest stages of the journey, as the hero learns the lay of the land and defines their relationship to other characters.

Wondering how to create captivating characters? Read our guide , which explains how to shape characters that readers will love—or hate.

Tests, Allies, and Enemies in The Matrix :

Neo is introduced to the vagabond crew of the Nebuchadnezzar . Morpheus informs Neo that he is The One , a savior destined to liberate humanity. He learns jiu jitsu and other useful skills.

#7: Approach to the Inmost Cave

Time to get a little metaphorical. The inmost cave isn’t a physical cave, but rather a place of great danger—indeed, the most dangerous place in the special world . It could be a villain’s lair, an impending battle, or even a mental barrier. No spelunking required.

Broadly speaking, the approach is marked by a setback in the quest. It becomes a lesson in persistence, where the hero must reckon with failure, change their mindset, or try new ideas.

Note that the hero hasn’t entered the cave just yet. This stage is about the approach itself, which the hero must navigate to get closer to their ultimate goal. The stakes are rising, and failure is no longer an option.

Approach to the Inmost Cave in The Matrix :

Neo pays a visit to The Oracle. She challenges Neo to “know thyself”—does he believe, deep down, that he is The One ? Or does he fear that he is “just another guy”? She warns him that the fate of humanity hangs in the balance.

#8: The Ordeal

The ordeal marks the hero’s greatest test thus far. This is a dark time for them: indeed, Campbell refers to it as the “belly of the whale.” The hero experiences a major hurdle or obstacle, which causes them to hit rock bottom.

This is a pivotal moment in the story, the main event of the second act. It is time for the hero to come face to face with their greatest fear. It will take all their skills to survive this life-or-death crisis. Should they succeed, they will emerge from the ordeal transformed.

Keep in mind: the story isn’t over yet! Rather, the ordeal is the moment when the protagonist overcomes their weaknesses and truly steps into the title of hero .

The Ordeal in The Matrix :

When Cipher betrays the crew to the agents, Morpheus sacrifices himself to protect Neo. In turn, Neo makes his own choice: to risk his life in a daring rescue attempt.

#9: Reward (Seizing the Sword)

The ordeal was a major level-up moment for the hero. Now that it's been overcome, the hero can reap the reward of success. This reward could be an object, a skill, or knowledge—whatever it is that the hero has been struggling toward. At last, the sword is within their grasp.

From this moment on, the hero is a changed person. They are now equipped for the final conflict, even if they don’t fully realize it yet.

Reward (Seizing the Sword) in The Matrix :

Neo’s reward is helpfully narrated by Morpheus during the rescue effort: “He is beginning to believe.” Neo has gained confidence that he can fight the machines, and he won’t back down from his destiny.

#10: The Road Back

We’re now at the beginning of act three, the return . With the reward in hand, it’s time to exit the inmost cave and head home. But the story isn’t over yet.

In this stage, the hero reckons with the consequences of act two. The ordeal was a success, but things have changed now. Perhaps the dragon, robbed of his treasure, sets off for revenge. Perhaps there are more enemies to fight. Whatever the obstacle, the hero must face them before their journey is complete.

The Road Back in The Matrix :

The rescue of Morpheus has enraged Agent Smith, who intercepts Neo before he can return to the Nebuchadnezzar . The two foes battle in a subway station, where Neo’s skills are pushed to their limit.

#11: Resurrection

Now comes the true climax of the story. This is the hero’s final test, when everything is at stake: the battle for the soul of Gotham, the final chance for evil to triumph. The hero is also at the peak of their powers. A happy ending is within sight, should they succeed.

Vogler calls the resurrection stage the hero’s “final exam.” They must draw on everything they have learned and prove again that they have really internalized the lessons of the ordeal . Near-death escapes are not uncommon here, or even literal deaths and resurrections.

Resurrection in The Matrix :

Despite fighting valiantly, Neo is defeated by Agent Smith and killed. But with Trinity’s help, he is resurrected, activating his full powers as The One . Isn’t it wonderful how literal The Matrix can be?

#12: Return with the Elixir

Hooray! Evil has been defeated and the hero is transformed. It’s time for the protagonist to return home in triumph, and share their hard-won prize with the ordinary world . This prize is the elixir —the object, skill, or insight that was the hero’s true reward for their journey and transformation.

Return with the Elixir in The Matrix :

Neo has defeated the agents and embraced his destiny. He returns to the simulated world of the Matrix, this time armed with god-like powers and a resolve to open humanity’s eyes to the truth.

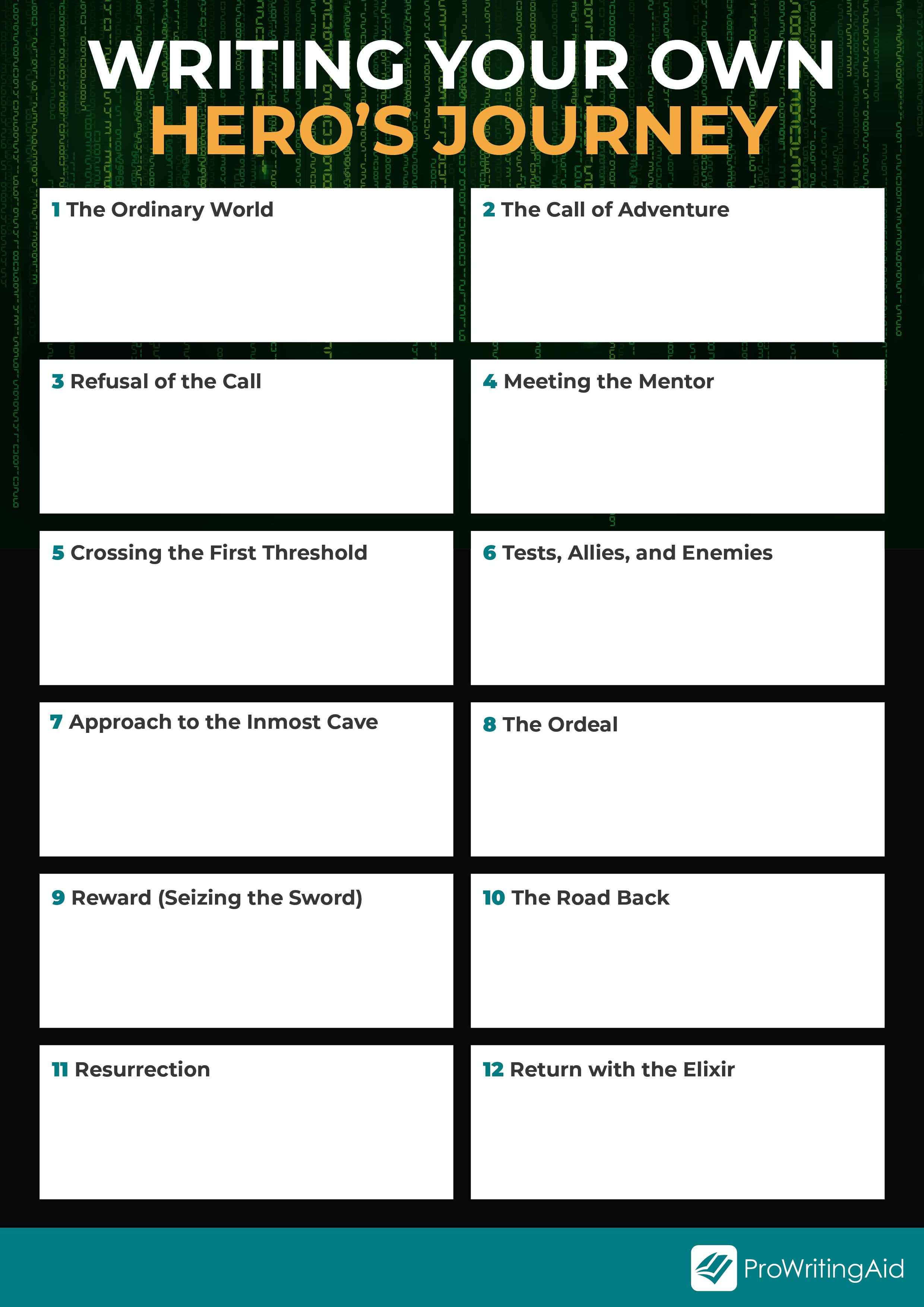

If you’re writing your own adventure, you may be wondering: should I follow the Hero’s Journey structure?

The good news is, it’s totally up to you. Joseph Campbell conceived of the monomyth as a way to understand universal story structure, but there are many ways to outline a novel. Feel free to play around within its confines, adapt it across different media, and disrupt reader expectations. It’s like Morpheus says: “Some of these rules can be bent. Others can be broken.”

Think of the Hero’s Journey as a tool. If you’re not sure where your story should go next, it can help to refer back to the basics. From there, you’re free to choose your own adventure.

Are you prepared to write your novel? Download this free book now:

The Novel-Writing Training Plan

So you are ready to write your novel. excellent. but are you prepared the last thing you want when you sit down to write your first draft is to lose momentum., this guide helps you work out your narrative arc, plan out your key plot points, flesh out your characters, and begin to build your world..

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Dan holds a PhD from Yale University and CEO of FaithlessMTG

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Improve your writing in one of the largest and most successful writing groups online

Join our writing community!

The Hero’s Journey Ultimate Writing Guide with Examples

by Alex Cabal

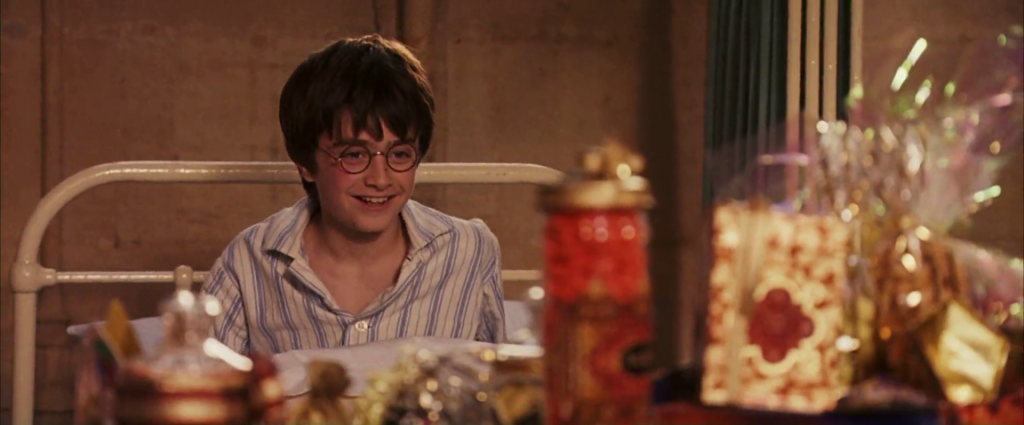

What do Star Wars , The Hobbit , and Harry Potter have in common? They’re all examples of a story archetype as old as time. You’ll see this universal narrative structure in books, films, and even video games.

This ultimate Hero’s Journey writing guide will define and explore all quintessential elements of the Hero’s Journey—character archetypes, themes, symbolism, the three act structure, as well as 12 stages of the Hero’s Journey. We’ll even provide a downloadable plot template, tips for writing the Hero’s Journey, and writing prompts to get the creative juices flowing.

What is the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey is a universal story structure that follows the personal metamorphosis and psychological development of a protagonist on a heroic adventure. The protagonist goes through a series of stages to overcome adversity and complete a quest to attain an ultimate reward—whether that’s something tangible, like the holy grail, or something internal, like self confidence.

In the process of self-discovery, the archetypal Hero’s Journey is typically cyclical; it begins and ends in the same place (Think Frodo leaving and then returning to the Shire). After the epic quest or adventure has been completed by overcoming adversity and conflict—both physical and mental—the hero arrives where they once began, changed in some as they rose to meet the ultimate conflict or ordeal of the quest.

Joseph Campbell and Christopher Vogler

The Hero’s Journey has a long history of conversation around the form and its uses, with notable contributors including Joseph Campbell and the screenwriter Christopher Vogler , who later revised the steps of the Hero’s Journey.

Joseph Campbell’s “monomyth” framework is the traditional story structure of the Hero’s Journey archetype. Campbell developed it through analysis of ancient myths, folktales, and religious stories. It generally follows three acts in a cyclical, rather than a linear, way: a hero embarks on a journey, faces a crisis, and then returns home transformed and victorious.

Campbell’s ideation of the monomyth in his book The Hero With a Thousand Faces was influenced by Carl Jung’s perspective of psychology and models of self-transformation , where the Hero’s Journey is a path of transformation to a higher self, psychological healing, and spiritual growth.

While Campbell’s original take on the monomyth included 17 steps within the three acts, Christopher Vogler, in his book The Writer’s Journey , refined those 17 steps into 12 stages—the common formula for the modern structure many writers use today.

It’s also worth checking out Maureen Murdock’s work on the archetype, “The Heroine’s Journey.” This takes a look at the female Hero’s Journey, which examines the traditionally masculine journey through a feminist lens.

Hero’s Journey diagram: acts, steps, and stages

Below, you can see the way Volger’s Hero’s Journey is broken into twelve story beats across three acts.

Why is the Hero’s Journey so popular?

The structure of the Hero’s Journey appears in many of our most beloved classic stories, and it continues to resonate over time because it explores the concept of personal transformation and growth through both physical and mental trials and tribulations. In some sense, every individual in this mythic structure experiences rites of passage, the search for home and the true authentic self, which is mirrored in a protagonist’s journey of overcoming obstacles while seeking to fulfill a goal.

Additionally, the Hero’s Journey typically includes commonly shared symbols and aspects of the human psyche—the trickster, the mother, the child, etc. These archetypes play a role in creating a story that the reader can recognize from similar dynamics in their own relationships, experiences, and familiar world. Archetypes allow the writer to use these “metaphorical truths”—a playful deceiver, a maternal bond, a person of innocence and purity—to deeply and empathetically connect with the reader through symbolism. That’s why they continue to appear in countless stories all around the world.

Hero’s Journey character archetypes

Character archetypes are literary devices based on a set of qualities that are easy for a reader to identify, empathize with, and understand, as these qualities and traits are common to the human experience.

It should be noted that character archetypes are not stereotypes . While stereotypes are oversimplifications of demographics or personality traits, an archetype is a symbol of a universal type of character that can be recognized either in one’s self or in others in real life.

The following archetypes are commonly used in a Hero’s Journey:

The hero is typically the protagonist or principal point-of-view character within a story. The hero transforms—internally, externally, often both—while on their journey as they experience tests and trials and are aided or hindered by the other archetypes they encounter. In general, the hero must rise to the challenge and at some point make an act of sacrifice for the ultimate greater good. In this way, the Hero’s Journey represents the reader’s own everyday battles and their power to overcome them.

Heroes may be willing or unwilling. Some can be downright unheroic to begin with. Antiheroes are notably flawed characters that must grow significantly before they achieve the status of true hero.

The mentor often possesses divine wisdom or direct experience with the special world, and has faith in the hero. They often give the hero a gift or supernatural aid, which is usually something important for the quest: either a weapon to destroy a monster, or a talisman to enlighten the hero. The mentor may also directly aid the hero or present challenges to them that force internal or external growth. After their meeting, the hero leaves stronger and better prepared for the road ahead.

The herald is the “call to adventure.” They announce the coming of significant change and become the reason the hero ventures out onto a mysterious adventure. The herald is a catalyst that enters the story and makes it impossible for the hero to remain in status quo. Existing in the form of a person or an event, or sometimes just as information, they shift the hero’s balance and change their world.

The Threshold Guardian

This archetype guards the first threshold—the major turning point of the story where the hero must make the true commitment of the journey and embark on their quest to achieve their destiny. Threshold guardians spice up the story by providing obstacles the hero must overcome, but they’re usually not the main antagonist.

The role of the threshold guardian is to help round out the hero along their journey. The threshold guardian will test the hero’s determination and commitment and will drive them forward as the hero enters the next stage of their journey, assisting the development of the hero’s character arc within the plot. The threshold guardian can be a friend who doesn’t believe in the hero’s quest, or a foe that makes the hero question themselves, their desires, or motives in an attempt to deter the hero from their journey. Ultimately, the role of the threshold guardian is to test the hero’s resolve on their quest.

The Shape Shifter

The shape shifter adds dramatic tension to the story and provides the hero with a puzzle to solve. They can seem to be one thing, but in fact be something else. They bring doubt and suspense to the story and test the hero’s ability to discern their path. The shape shifter may be a lover, friend, ally, or enemy that somehow reveals their true self from the hero’s preconceived notion. This often causes the hero internal turmoil, or creates additional challenges and tests to overcome.

The shadow is the “monster under the bed,” and could be repressed feelings, deep trauma, or festering guilt. These all possess the dark energy of the shadow. It is the dark force of the unexpressed, unrealized, rejected, feared aspects of the hero and is often, but not necessarily, represented by the main antagonist or villain.

However, other characters may take the form of the shadow at different stages of the story as “foil characters” that contrast against the hero. They might also represent what could happen if the hero fails to learn, transform, and grow to complete their quest. At times, a hero may even succumb to the shadow, from which they will need to make sacrifices to be redeemed to continue on their overall quest.

The Trickster

The trickster is the jester or fool of the story that not only provides comic relief, but may also act as a commentator as the events of the plot unfold. Tricksters are typically witty, clever, spontaneous, and sometimes even ridiculous. The trickster within a story can bring a light-hearted element to a challenge, or find a clever way to overcome an obstacle.

Hero’s Journey themes and symbols

Alongside character archetypes, there are also archetypes for settings, situations, and symbolic items that can offer meaning to the world within the story or support your story’s theme.

Archetypes of themes, symbols, and situations represent shared patterns of human existence. This familiarity can provide the reader insight into the deeper meaning of a story without the writer needing to explicitly tell them. There are a great number of archetypes and symbols that can be used to reinforce a theme. Some that are common to the Hero’s Journey include:

Situational archetypes

Light vs. dark and the battle of good vs. evil

Death, rebirth, and transformation in the cycle of life

Nature vs. technology, and the evolution of humanity

Rags to riches or vice versa, as commentary on the material world and social status

Wisdom vs. knowledge and innocence vs. experience, in the understanding of intuition and learned experience

Setting archetypes

Gardens may represent the taming of nature, or living in harmony with nature.

Forests may represent reconnection with nature or wildness, or the fear of the unknown.

Cities or small towns may represent humanity at its best and at its worst. A small town may offer comfort and rest, while simultaneously offering judgment; a city may represent danger while simultaneously championing diversity of ideas, beings, and cultures.

Water and fire within a landscape may represent danger, change, purification, and cleansing.

Symbolic items

Items of the past self. These items are generally tokens from home that remind the hero of where they came from and who or what they’re fighting for.

Gifts to the hero. These items may be given to the hero from a mentor, ally, or even a minor character they meet along the way. These items are typically hero talismans, and may or may not be magical, but will aid the hero on their journey.

Found items. These items are typically found along the journey and represent some sort of growth or change within the hero. After all, the hero would never have found the item had they not left their everyday life behind. These items may immediately seem unimportant, but often carry great significance.

Earned rewards. These items are generally earned by overcoming a test or trial, and often represent growth, or give aid in future trials, tests, and conflicts.

The three act structure of the Hero’s Journey

The structure of the Hero’s Journey, including all 12 steps, can be grouped into three stages that encompass each phase of the journey. These acts follow the the external and internal arc of the hero—the beginning, the initiation and transformation, and the return home.

Act One: Departure (Steps 1—5)

The first act introduces the hero within the ordinary world, as they are—original and untransformed. The first act will typically include the first five steps of the Hero’s Journey.

This section allows the writer to set the stage with details that show who the hero is before their metamorphosis—what is the environment of the ordinary world? What’s important to the hero? Why do they first refuse the call, and then, why do they ultimately accept and embark on the journey to meet with the conflict?

This stage introduces the first major plot point of the story, explores the conflict the hero confronts, and provides the opportunity for characterization for the hero and their companions.

The end of the first act generally occurs when the hero has fully committed to the journey and crossed the threshold of the ordinary world—where there is no turning back.

Act Two: Initiation (Steps 6—9)

Once the hero begins their journey, the second act marks the beginning of their true initiation into the unfamiliar world—they have crossed the threshold, and through this choice, have undergone their first transformation.

The second act is generally the longest of the three and includes steps six through nine.

In this act, the hero meets most of the characters that will be pivotal to the plot, including friends, enemies, and allies. It offers the rising action and other minor plot points related to the overarching conflict. The hero will overcome various trials, grow and transform, and navigate subplots—the additional and unforeseen complexity of the conflict.

This act generally ends when the hero has risen to the challenge to overcome the ordeal and receives their reward. At the end of this act, it’s common for the theme and moral of the story to be fully unveiled.

Act Three: Return (Steps 10—12)

The final stage typically includes steps 10—12, generally beginning with the road back—the point in the story where the hero must recommit to the journey and use all of the growth, transformation, gifts and tools acquired along the journey to bring a decisive victory against their final conflict.

From this event, the hero will also be “reborn,” either literally or metaphorically, and then beginning anew as a self-actualized being, equipped with internal knowledge about themselves, external knowledge about the world, and experience.

At the end of the third act, the hero returns home to the ordinary world, bringing back the gifts they earned on their journey. In the final passages, both the hero and their perception of the ordinary world are compared with what they once were.

The 12 steps of the Hero’s Journey

The following guide outlines the 12 steps of the Hero’s Journey and represents a framework for the creation of a Hero’s Journey story template. You don’t necessarily need to follow the explicit cadence of these steps in your own writing, but they should act as checkpoints to the overall story.

We’ll also use JRR Tolkien’s The Hobbit as a literary example for each of these steps. The Hobbit does an exemplary job of following the Hero’s Journey, and it’s also an example of how checkpoints can exist in more than one place in a story, or how they may deviate from the typical 12-step process of the Hero’s Journey.

1. The Ordinary World

This stage in the Hero’s Journey is all about exposition. This introduces the hero’s backstory—who the hero is, where they come from, their worldview, culture, and so on. This offers the reader a chance to relate to the character in their untransformed form.

As the story and character arc develop, the reader is brought along the journey of transformation. By starting at the beginning, a reader has a basic understanding of what drives the hero, so they can understand why the hero makes the choices they do. The ordinary world shows the protagonist in their comfort zone, with their worldview being limited to the perspective of their everyday life.

Characters in the ordinary world may or may not be fully comfortable or satisfied, but they don’t have a point of reference to compare—they have yet to leave the ordinary world to gain the knowledge to do so.

Step One example

The Hobbit begins by introducing Bilbo in the Shire as a respectable and well-to-do member of the community. His ordinary world is utopian and comfortable. Yet, even within a village that is largely uninterested in the concerns of the world outside, the reader is provided a backstory: even though Bilbo buys into the comforts and normalcy of the Shire, he still yearns for adventure—something his neighbors frown upon. This ordinary world of the Shire is disrupted with the introduction of Gandalf—the “mentor”—who is somewhat uncomfortably invited to tea.

2. Call to Adventure

The call to adventure in the Hero’s Journey structure is the initial internal conflict that the protagonist hero faces, that drives them to the true conflict that they must overcome by the end of their journey.

The call occurs within the known world of the character. Here the writer can build on the characterization of the protagonist by detailing how they respond to the initial call. Are they hesitant, eager, excited, refusing, or willing to take a risk?

Step Two example

Bilbo’s call to adventure takes place at tea as the dwarves leisurely enter his home, followed by Gandalf, who identifies Bilbo as the group’s missing element—the burglar, and the lucky 14th member.

Bilbo and his ordinary world are emphasized by his discomfort with his rambunctious and careless guests. Yet as the dwarves sing stories of old adventures, caverns, and lineages, which introduce and foreshadow the conflict to come, a yearning for adventure is stirred. Though he still clings to his ordinary world and his life in the Shire, he’s conflicted. Should he leave the shire and experience the world, or stay in his comfortable home? Bilbo continues to refuse the call, but with mixed feelings.

3. Refusal of the Call

The refusal of the call in the Hero’s Journey showcases a “clinging” to one’s original self or world view. The initial refusal of the call represents a fear of change, as well as a resistance to the internal transformation that will occur after the adventure has begun.

The refusal reveals the risks that the protagonist faces if they were to answer the call, and shows what they’ll leave behind in the ordinary world once they accept.

The refusal of the call creates tension in the story, and should show the personal reasons why the hero is refusing—inner conflict, fear of change, hesitation, insecurity, etc. This helps make their character clearer for the reader.

These are all emotions a reader can relate to, and in presenting them through the hero, the writer deepens the reader’s relationship with them and helps the reader sympathize with the hero’s internal plight as they take the first step of transformation.

Step Three example

Bilbo refuses the call in his first encounter with Gandalf, and in his reaction to the dwarves during tea. Even though Bilbo’s “Tookish” tendencies make him yearn for adventure, he goes to bed that night still refusing the call. The next morning, as Bilbo awakes to an empty and almost fully clean hobbit home, he feels a slight disappointment for not joining the party, but quickly soothes his concerns by enjoying the comfort of his home—i.e. the ordinary world. Bilbo explores his hesitation to disembark from the ordinary world, questioning why a hobbit would become mixed up in the adventures of others, and choosing not to meet the dwarves at the designated location.

4. Meeting the Mentor

Meeting the mentor in the Hero’s Journey is the stage that provides the hero protagonist with a guide, relationship, and/or informational asset that has experience outside the ordinary world. The mentor offers confidence, advice, wisdom, training, insight, tools, items, or gifts of supernatural wonder that the hero will use along the journey and in overcoming the ultimate conflict.

The mentor often represents someone who has attempted to overcome, or actually has overcome, an obstacle, and encourages the hero to pursue their calling, regardless of the hero’s weaknesses or insecurities. The mentor may also explicitly point out the hero’s weaknesses, forcing them to reckon with and accept them, which is the first step to their personal transformation.

Note that not all mentors need to be a character . They can also be objects or knowledge that has been instilled in the hero somehow—cultural ethics, spiritual guidance, training of a particular skill, a map, book, diary, or object that illuminates the path forward, etc. In essence, the mentor character or object has a role in offering the protagonist outside help and guidance along the Hero’s Journey, and plays a key role in the protagonist’s transition from normalcy to heroism.

The mentor figure also offers the writer the opportunity to incorporate new information by expanding upon the story, plot, or backstory in unique ways. They do this by giving the hero information that would otherwise be difficult for the writer to convey naturally.

The mentor may accompany the hero throughout most of the story, or they may only periodically be included to facilitate changes and transformation within them.

Step Four example

The mentor, Gandalf, is introduced almost immediately. Gandalf is shown to be the mentor, firstly through his arrival from—and wisdom of—the outside world; and secondly, through his selection of Bilbo for the dwarven party by identifying the unique characteristics Bilbo has that are essential to overcoming the challenges in the journey. Gandalf doesn’t accompany Bilbo and the company through all of the trials and tribulations of the plot, but he does play a key role in offering guidance and assistance, and saves the group in times of dire peril.

5. Crossing the Threshold

As the hero crosses the first threshold, they begin their personal quest toward self-transformation. Crossing the threshold means that the character has committed to the journey, and has stepped outside of the ordinary world in the pursuit of their goal. This typically marks the conclusion of the first act.

The threshold lies between the ordinary world and the special world, and marks the point of the story where the hero fully commits to the road ahead. It’s a crucial stage in the Hero’s Journey, as the hero wouldn’t be able to grow and transform by staying in the ordinary world where they’re comfortable and their world view can’t change.

The threshold isn’t necessarily a specific place within the world of the story, though a place can symbolize the threshold—for example a border, gateway, or crossroads that separate what is safe and “known” from what is potentially dangerous. It can also be a moment or experience that causes the hero to recognize that the comforts and routine of their world no longer apply—like the loss of someone or something close to the hero, for example. The purpose of the threshold is to take the hero out of their element and force them, and the reader, to adapt from the known to the unknown.

This moment is crucial to the story’s tension. It marks the first true shift in the character arc and the moment the adventure has truly begun. The threshold commonly forces the hero into a situation where there’s no turning back. This is sometimes called the initiation stage or the departure stage.

Step Five example

The threshold moment in The Hobbit occurs when the party experiences true danger as a group for the first time. Bilbo, voted as scout by the party and eager to prove his burglar abilities, sneaks upon a lone fire in the forest where he finds three large trolls. Rather than turn back empty-handed—as he initially wants to—Bilbo chooses to prove himself, plucking up the courage to pickpocket the trolls—but is caught in the process. The dwarves are also captured and fortunately, Gandalf, the mentor, comes to save the party.

Bilbo’s character arc is solidified in this threshold moment. He experiences his first transformation when he casts aside fear and seeks to prove himself as a burglar, and as an official member of the party. This moment also provides further characterization of the party as a whole, proving the loyalty of the group in seeking out their captured member.

Gandalf’s position as the mentor is also firmly established as he returns to ultimately save all of the members of the party from being eaten by trolls. The chapter ends with Bilbo taking ownership of his first hero talisman—the sword that will accompany him through the rest of the adventure.

6. Tests, Allies, Enemies

Once the hero has crossed the threshold, they must now encounter tests of courage, make allies, and inevitably confront enemies. All these elements force the hero to learn the new ways of the special world and how it differs from the hero’s ordinary world—i.e. how the rules have changed, the conditions of the special world vs. the ordinary world, and the various beings and places within it.

All these elements spark stages of transformation within the hero—learning who they can trust and who they can’t, learning new skills, seeking training from the mentor, and overcoming challenges that force and drive them to grow and transform.

The hero may both succeed and fail at various points of this stage, which will test their commitment to the journey. The writer can create tension by making it clear that the hero may or may not succeed at the critical moment of crisis. These crises can be external or internal.

External conflicts are issues that the character must face and overcome within the plot—e.g. the enemy has a sword drawn and the hero must fight to survive.

Internal conflicts occur inside the hero. For example, the hero has reached safety, but their ally is in peril; will they step outside their comfort zone and rise to the occasion and save their friend? Or will they return home to their old life and the safety of the ordinary world?

Tests are conflicts and threats that the hero must face before they reach the true conflict, or ordeal, of the story. These tests set the stage and prime the hero to meet and achieve the ultimate goal. They provide the writer the opportunity to further the character development of the hero through their actions, inactions, and reactions to what they encounter. The various challenges they face will teach them valuable lessons, as well as keep the story compelling and the reader engaged.

Allies represent the characters that offer support to the protagonist along the journey. Some allies may be introduced from the beginning, while others may be gained along the journey. Secondary characters and allies provide additional nuance for the hero, through interactions, events, and relationships that further show who the hero is at heart, what they believe in, and what they’re willing to fight for. The role of the allies is to bring hope, inspiration, and further drive the hero to do what needs to be done.

Enemies represent a foil to the allies. While allies bring hope and inspiration, enemies will provide challenges, conflicts, tests, and challenges. Both allies and enemies may instigate transformative growth, but enemies do so in a way that fosters conflict and struggle.

Characterization of enemies can also enhance the development of the hero through how they interact and the lessons learned through those interactions. Is the hero easily duped, forgiving, empathetic, merciful? Do they hold a grudge and seek revenge? Who is the hero now that they have been harmed, faced an enemy, and lost pieces of their innocent worldview? To answer that, the hero is still transforming and gestating with every lesson, test, and enemy faced along the way.

Step Six example

As the plot of The Hobbit carries on, Bilbo encounters many tests, allies, and enemies that all drive complexity in the story. A few examples include:

The first major obstacle that Bilbo faces occurs within the dark and damp cave hidden in the goblin town. All alone, Bilbo must pluck up the wit and courage to outriddle a creature named Gollum. In doing so, Bilbo discovers the secret power of a golden ring (another hero talisman) that will aid him and the party through the rest of the journey.

The elves encountered after Bilbo “crosses the threshold” are presented as allies in the story. The hero receives gifts of food, a safe place to rest, and insight and guidance that allows the party to continue on their journey. While the party doesn’t dwell long with the elves, the elves also provide further character development for the party at large: the serious dwarf personalities are juxtaposed against the playful elvish ones, and the elves offer valuable historical insight with backstory to the weapons the party gathered from the troll encounter.

Goblins are a recurring enemy within the story that the hero and party must continue to face, fight, and run from. The goblins present consistent challenges that force Bilbo to face fear and learn and adapt, not only to survive but to save his friends.

7. Approach to the Inmost Cave

The approach to the inmost cave of the Hero’s Journey is the tense quiet before the storm; it’s the part of the story right before the hero faces their greatest fear, and it can be positioned in a few different ways. By now, the hero has overcome obstacles, setbacks, and tests, gained and lost allies and enemies, and has transformed in some way from the original protagonist first introduced in the ordinary world.

The moment when the hero approaches the inmost cave can be a moment of reflection, reorganization, and rekindling of morale. It presents an opportunity for the main characters of the story to come together in a moment of empathy for losses along the journey; a moment of planning and plotting next steps; an opportunity for the mentor to teach a final lesson to the hero; or a moment for the hero to sit quietly and reflect upon surmounting the challenge they have been journeying toward for the length of their adventure.

The “cave” may or may not be a physical place where the ultimate ordeal and conflict will occur. The approach represents the momentary period where the hero assumes their final preparation for the overall challenge that must be overcome. It’s a time for the hero and their allies, as well as the reader, to pause and reflect on the events of the story that have already occurred, and to consider the internal and external growth and transformation of the hero.

Having gained physical and/or emotional strength and fortitude through their trials and tests, learned more rules about the special world, found and lost allies and friends, is the hero prepared to face danger and their ultimate foe? Reflection, tension, and anticipation are the key elements of crafting the approach to the cave.

Step Seven example

The approach to the cave in The Hobbit occurs as the party enters the tunnel of the Lonely Mountain. The tunnel is the access point to the ultimate goal—Thorin’s familial treasure, as well as the ultimate test—the formidable dragon Smaug. During this part of the story, the party must hide, plot, and plan their approach to the final conflict. It’s at this time that Bilbo realizes he must go alone to scout out and face the dragon.

8. The Ordeal

The ordeal is the foreshadowed conflict that the hero must face, and represents the midpoint of the story. While the ordeal is the ultimate conflict that the hero knows they must overcome, it’s a false climax to the complete story—there’s still much ground to cover in the journey, and the hero will still be tested after completing this, the greatest challenge. In writing the ordeal phase of the Hero’s Journey, the writer should craft this as if it actually were the climax to the tale, even though it isn’t.

The first act, and the beginning of the second act, have built up to the ordeal with characterization and the transformation of the hero through their overcoming tests and trials. This growth—both internal and external—has all occurred to set the hero up to handle this major ordeal.

As this stage commences, the hero is typically faced with fresh challenges to make the ordeal even more difficult than they previously conceived. This may include additional setbacks for the hero, the hero’s realization that they were misinformed about the gravity of the situation, or additional conflicts that make the ordeal seem insurmountable.

These setbacks cause the hero to confront their greatest fears and build tension for both the hero and the reader, as they both question if the hero will ultimately succeed or fail. In an epic fantasy tale, this may mean a life-or-death moment for the hero, or experiencing death through the loss of an important ally or the mentor. In a romance, it may be the moment of crisis where a relationship ends or a partner reveals their dark side or true self, causing the hero great strife.

This is the rock-bottom moment for the hero, where they lose hope, courage, and faith. At this point, even though the hero has already crossed the threshold, this part of the story shows how the hero has changed in such a way that they can never return to their original self: even if they return to the ordinary world, they’ll never be the same; their perception of the world has been modified forever.

Choosing to endure against all odds and costs to face the ordeal represents the loss of the hero’s original self from the ordinary world, and a huge internal transformation occurs within the hero as they must rise and continue forth to complete their journey and do what they set out to do from the beginning.

The ordeal may also be positioned as an introduction to the greater villain through a trial with a shadow villain, where the hero realizes that the greatest conflict is unveiled as something else, still yet to come. In these instances, the hero may fail, or barely succeed, but must learn a crucial lesson and be metaphorically resurrected through their failure to rise again and overcome the greater challenge.

Step Eight example

Bilbo must now face his ultimate challenge: burgle the treasure from the dragon. This is the challenge that was set forth from the beginning, as it’s his purpose as the party’s 14th member, the burglar, anointed by Gandalf, the mentor. Additional conflicts arise as Bilbo realizes that he must face the dragon alone, and in doing so, must rely on all of the skills and gifts in the form of talismans and tokens he has gained throughout the adventure.

During the ordeal, Bilbo uses the courage he has gained by surmounting the story’s previous trials; he’s bolstered by his loyalty to the group and relies upon the skills and tools he has earned in previous trials. Much as he outwitted Gollum in the cave, Bilbo now uses his wit as well as his magical ring to defeat Smaug in a game of riddles, which ultimately leads Smaug out of the lair so that Bilbo can complete what he was set out to do—steal the treasure.

The reward of the Hero’s Journey is a moment of triumph, celebration, or change as the hero achieves their first major victory. This is a moment of reflection for both the reader and the hero, to take a breath to contemplate and acknowledge the growth, development, and transformation that has occurred so far.

The reward is the boon that the hero learns, is granted, or steals, that will be crucial to facing the true climax of the story that is yet to come. The reward may be a physical object, special knowledge, or reconciliation of some sort, but it’s always a thing that allows for some form of celebration or replenishment and provides the drive to succeed before the journey continues.

Note that the reward may not always be overtly positive—it may also be a double-edged sword that could harm them physically or spiritually. This type of reward typically triggers yet another internal transformation within the hero, one that grants them the knowledge and personal drive to complete the journey and face their remaining challenges.

From the reward, the hero is no longer externally driven to complete the journey, but has evolved to take on the onus of doing so.

Examples of rewards may include:

A weapon, elixir, or object that will be necessary to complete the quest.

Special knowledge, or a personal transformation to use against a foe.

An eye-opening experience that provides deep insight and fundamentally changes the hero and their position within the story and world.

Reconciliation with another character, or with themselves.

No matter what the reward is, the hero should experience some emotional or spiritual revelation and a semblance of inner peace or personal resolve to continue the journey. Even if the reward is not overtly positive, the hero and the reader deserve a moment of celebration for facing the great challenge they set out to overcome.

Step Nine example

Bilbo defeats the dragon at a battle of wits and riddles, and now receives his reward. He keeps the gifts he has earned, both the dagger and the gold ring. He is also granted his slice of the treasure, and the Lonely Mountain is returned to Thorin. The party at large is rewarded for completing the quest and challenge they set out to do.

However, Tolkien writes the reward to be more complex than it first appears. The party remains trapped and hungry within the Mountain as events unfold outside of it. Laketown has been attacked by Smaug, and the defenders will want compensation for the damage to their homes and for their having to kill the dragon. Bilbo discovers, and then hides, the Arkenstone (a symbolic double edged reward) to protect it from Thorin’s selfishness and greed.

10. The Road Back

The road back in the Hero’s Journey is the beginning of the third act, and represents a turning point within the story. The hero must recommit to the journey, alongside the new stakes and challenges that have arisen from the completion of the original goal.

The road back presents roadblocks—new and unforeseen challenges to the hero that they must now face on their journey back to the ordinary world. The trials aren’t over yet, and the stakes are raised just enough to keep the story compelling before the final and ultimate conflict—the hero’s resurrection—is revealed in the middle of the third act.

The hero has overcome their greatest challenge in the Ordeal and they aren’t the same person they were when they started. This stage of the story often sees the hero making a choice, or reflecting on their transformed state compared to their state at the start of the journey.

The writer’s purpose in the third act is not to eclipse the upcoming and final conflict, but to up the stakes, show the true risk of the final climax, and to reflect on what it will take for the hero to ultimately prevail. The road back should offer a glimmer of hope—the light at the end of the tunnel—and should let the reader know the dramatic finale is about to arrive.

Step Ten example

What was once a journey to steal treasure and slay a dragon has developed new complications. Our hero, Bilbo, must now use all of the powers granted in his personal transformation, as well as the gifts and rewards he earned on the quest, to complete the final stages of the journey.

This is the crisis moment of The Hobbit ; the armies of Laketown are prepared for battle to claim their reward for killing Smaug; the fearless leader of their party, Thorin, has lost reason and succumbed to greed; and Bilbo makes a crucial choice based his personal growth: he gives the Arkenstone to the king as a bargaining chip for peace. Bilbo also briefly reconnects with the mentor, Gandalf, who warns him of the unpleasant times ahead, but comforts Bilbo by saying that things may yet turn out for the best. Bilbo then loyally returns to his friends, the party of dwarves, to stand alongside them in the final battle.

11. Resurrection

The resurrection stage of the Hero’s Journey is the final climax of the story, and the heart of the third act. By now the hero has experienced internal and external transformation and a loss of innocence, coming out with newfound knowledge. They’re fully rooted in the special world, know its rules, and have made choices that underline this new understanding.

The hero must now overcome the final crisis of their external quest. In an epic fantasy tale, this may be the last battle of light versus darkness, good versus evil, a cumulation of fabulous forces. In a thriller, the hero might ultimately face their own morality as they approach the killer. In a drama or romance, the final and pivotal encounter in a relationship occurs and the hero puts their morality ahead of their immediate desires.

The stakes are the highest they’ve ever been, and the hero must often choose to make a sacrifice. The sacrifice may occur as a metaphoric or symbolic death of the self in some way; letting go of a relationship, title, or mental/emotional image of the self that a hero once used as a critical aspect of their identity, or perhaps even a metaphoric physical death—getting knocked out or incapacitated, losing a limb, etc.

Through whatever the great sacrifice is, be it loss or a metaphoric death, the hero will experience a form of resurrection, purification, or internal cleansing that is their final internal transformation.

In this stage, the hero’s character arc comes to an end, and balance is restored to the world. The theme of the story is fully fleshed out and the hero, having reached some form of self-actualization, is forever changed. Both the reader and the hero experience catharsis—the relief, insight, peace, closure, and purging of fear that had once held the hero back from their final transformation.

Step Eleven example

All the armies have gathered, and the final battle takes place. Just before the battle commences, Bilbo tells Thorin that it was he who gave the Arkenstone to the city of men and offers to sacrifice his reward of gold for taking the stone. Gandalf, the mentor, arrives, standing beside Bilbo and his decision. Bilbo is shunned by Thorin and is asked to leave the party for his betrayal.

Bilbo experiences a symbolic death when he’s knocked out by a stone. Upon awakening, Bilbo is brought to a dying Thorin, who forgives him of his betrayal, and acknowledges that Bilbo’s actions were truly the right thing to do. The theme of the story is fully unveiled: that bravery and courage comes in all sizes and forms, and that greed and gold are less worthy than a life rich in experiences and relationships.

12. Return with the Elixir

The elixir in the Hero’s Journey is the final reward the hero brings with them on their return, bridging their two worlds. It’s a reward hard earned through the various relationships, tests, and growth the hero has experienced along their journey. The “elixir” can be a magical potion, treasure, or object, but it can also be intangible—love, wisdom, knowledge, or experience.

The return is key to the circular nature of the Hero’s Journey. It offers a resolution to both the reader and the hero, and a comparison of their growth from when the journey began.

Without the return, the story would have a linear nature, a beginning and an end. In bringing the self-actualized hero home to the ordinary world, the character arc is completed, and the changes they’ve undergone through the journey are solidified. They’ve overcome the unknown, and though they’re returning home, they can no longer resume their old life because of their new insight and experiences.

Step Twelve example

The small yet mighty hero Bilbo is accompanied on his journey home by his mentor Gandalf, as well as the allies he gathered along his journey. He returns with many rewards—his dagger, his golden ring, and his 1/14th split of the treasure—yet his greatest rewards are his experience and the friends he has made along the way. Upon entering the Shire Bilbo sings a song of adventure, and the mentor Gandalf remarks, “My dear Bilbo! Something is the matter with you, you are not the hobbit you were.”

The final pages of The Hobbit explore Bilbo’s new self in the Shire, and how the community now sees him as a changed hobbit—no longer quite as respectable as he once was, with odd guests who visit from time to time. Bilbo also composes his story “There and Back Again,” a tale of his experiences, underlining his greatest reward—stepping outside of the Shire and into the unknown, then returning home, a changed hobbit.

Books that follow the Hero’s Journey

One of the best ways to become familiar with the plot structure of the Hero’s Journey is to read stories and books that successfully use it to tell a powerful tale. Maybe they’ll inspire you to use the hero’s journey in your own writing!

The Lord of the Rings trilogy by J. R. R. Tolkien.

The Harry Potter series by J. K. Rowling.

The Earthsea series by Ursula K. Le Guin.

The Odyssey by Homer.

Siddhartha by Herman Hesse.

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen.

Writing tips for the Hero’s Journey

Writing a Hero’s Journey story often requires planning beforehand to organize the plot, structure, and events of the story. Here are some tips to use the hero’s journey archetype in a story:

Use a template or note cards to organize and store your ideas. This can assist in ensuring that you tie up any loose ends in the plot, and that the cadence of your story is already outlined before you begin writing.

Use word count goals for writing different sections of your story. This can help you keep pace while you plan and write the first draft. You can always revise, edit, and add in detail at later stages of development, but getting the ideas written without bogging them down with details can assist in preparing your outline, and may perhaps provide additional inspiration and guidance along the way.

Lean into creativity and be flexible with the 12 steps. They don’t need to occur in the exact order we’ve listed above, but that ordering can offer great checkpoint moments for your story.

Invest in characterization and ensure that your main character is balanced with credible strengths and weaknesses. A perfect, pure hero has no room to grow. A one-dimensional villain who relies on the trope of “pure evil” without any motivations for their actions is boring and predictable.

Ensure tension and urgency is woven into the story. An epic tale to the grocery store for baby formula may still be fraught with danger, and the price of failure is a hungry child. Without urgency, tension, and risk, a Hero’s Journey will fall flat.

Be hard on your characters. Give them deep conflicts that truly test their nature, and their mental, physical, and spiritual selves. An easy journey isn’t a memorable one.

Have a balance of scenes that play on both positive and negative emotions and outcomes for the hero to create a compelling plot line that continues to engage your reader. A story that’s relentlessly positive doesn’t provide a pathway for the hero to transform. Likewise, a story that’s nothing but doom, strife, and turmoil, without a light at the end of the tunnel or an opportunity for growth, can make a story feel stagnant and unengaging.

Reward your characters and your reader. Personal transformation and the road to the authentic self may be grueling, but there’s peace or joy at the end of the tunnel. Even if your character doesn’t fully saved the world, they—and the reader—should be rewarded with catharsis, a new perspective, or personal insight at the end of the tale.

Hero’s Journey templates

Download these free templates to help you plan out your Hero’s Journey:

Download the Hero’s Journey template template (docx) Download the Hero’s Journey template template (pdf)

Prompts and practices to help you write your own Hero’s Journey

Use the downloadable template listed below for the following exercises:

Read a book or watch a movie that follows the Hero’s Journey. Use the template to fill in when each step occurs or is completed. Make note of themes and symbols, character arcs, the main plot, and the subplots that drive complexity in the story.

When writing, use a timer set to 2—5 minutes per section to facilitate bursts of creativity. Brainstorm ideas for cadence, plot, and characters within the story. The outline you create can always be modified, but the timer ensures you can get ideas on paper without a commitment; you’re simply jotting down ideas as quickly as you can.

Use the downloadable template above to generate outlines based on the following prompts.

A woman’s estranged mother has died. A friend of the mother arrives at the woman’s home to tell her that her mother has left all her belongings to her daughter, and hands her a letter. The letter details the mother’s life, and the daughter must visit certain places and people to find her mother’s house and all the belongings in it—learning more about her mother’s life, and herself, along the way.

The last tree on earth has fallen, and technology can no longer sustain human life on Earth. An engineer, having long ago received alien radio signals from a tower in their backyard, has dedicated their life to building a spaceship in their garage. The time has come to launch, and the engineer must select a group of allies to bring with them to the stars, on a search for a new life, a new home, and “the others” out there in the universe.

A detective is given a new case: to find a much-talked-about murderer. The twist is, the murderer has sent a letter to the detective agency, quietly outing a homicidal politician who is up for re-election and is a major financial contributor to the police. In the letter, the murderer states that if the politician doesn’t come clean about their crimes, the murderer will kill the politician on the night of the election. The detective must solve the case before the election, and come to terms with their own feelings of justice and morality.

Get feedback on your writing today!

Scribophile is a community of hundreds of thousands of writers from all over the world. Meet beta readers, get feedback on your writing, and become a better writer!

Join now for free

Related articles

Writing the Rebel Archetype: Fictional Characters Who Make Their Own Rules (with Examples)

How to Write a Book Outline for a Nonfiction Book

What Are Character Archetypes? 16 Archetypes, Plus Examples

What are the Elements of a Story? 12 Central Story Elements

What is the Mentor Archetype? Definition and Examples

How to End a Story: 7 Different Kinds of Endings

Hero’s Journey in the 21st Century Essay

Introduction, the hero’s journey, the relevance of hero’s journey today.

Perhaps most people have heard hero stories before, especially when one is young as they form part of their inspiration. As such, a lonely individual trying to find himself embarks on an unexpected and treacherous journey that promises peril and adventure. During this period, the hero’s character, skill, and strength are tested with the ultimate battle that determines individuals’ resolve as they return home triumphantly. Drawing from Joseph Campbell’s book on the hero who had a thousand faces, Hamby (2019) has incorporated many examples of exemplary individuals through video games, books, and movies in The Hero’s Guidebook . Through the book, he shows the influence the works have on present society. Consequently, questions on the prevalence of such individuals in the 21 st century remain, with the young people having ideas of flawless, staller, and a perfect individual as their hero. As a result, this has led to a major question: do heroes exist in the current era? Against this background, the paper highlights the existence and relevance of such ideas in society.

A hero is an individual who aspires to achieve a specific task against all odds and works persistently to get results for the benefit of other people. Furthermore, they are willing to make a difference; promoting change for the welfare of others despite obstacles. Similarly, numerous incidents indicate how anybody can become a hero depending on the journey such a person follows in life. While highlighting the same, Hamby (2019) reaffirms Campbell’s mystic hero’s journey steps one passes through that are prevalent in the present world. As such, to be deemed a conqueror, one encounters and overcomes various obstacles or stages daily. Consequently, there are three main stages of travel such as departure, initiation, and return. In addition, the journey is an archetypal universal narrative structure found in cultural stories around the world sometimes referred to as monomyth or a single story with variations. Further, coined from numerous interesting literary traditions, the term is synonymous with success stories that follow the same narrative structure regardless of its culture or period.

On one hand, many movies have been produced based on the hero’s journey while on the other hand, their major characters become role models for young people. For instance, in the Star Wars film, Luke Skywalker learns to use the force and power of Jedi, and together with his fried they destroy the death star and rescue Princess Leia. During the initial stage of departure, Skywalker leaves the home planet in Tatooine trying to conquer the Galactic Empire. Further, he undergoes tribulations and trials during initiation along the journey which he overcomes by training with Obi-Wan Kenoi. Despite all that, he destroys death hence attaining his quest (Hamby, 2019). In addition, during the return, he comes back and wins a medal in commemoration of the victory.

Countless stories have been told in different parts of the world with the same theme to the present times. Notwithstanding, the hero’s journey in the 21 st century depicts personal life experiences involving an individual’s unique gift that differs from one another. Furthermore, its relevance to personal heroes’ journey relies on the usefulness of the narrative as a monomyth making it vital for people to recognize its limitations and apply it as a principal storytelling metaphor. As such, it brings meaning to the coexistence of people in their daily life struggles. Although the challenges, trials, and obstacles faced and overcome by individuals in society may seem trivial, such experiences encourage them to do better.

Further, the idea that through persistence and practice one can acquire power and help society resonates with many people in the present world. Perhaps such ideas and actions are exemplified by heroic people such as the armed forces serving in various parts of the world. The armies are not only brave but also, variant by putting themselves in danger to save the lives and human rights of strangers around the globe.

The hero’s journey applies to people’s daily lives and can take place at home, in battle, or anywhere during one’s lifetime. Unlike the original storyline, the individuals can fail on their travels since failure is part of the journey. However, the first step is to acquire a unique personal history, differentiating one another. In addition, the second step involves change which results in self-awareness. Therefore, people are initiated into believing in themselves, and hence they can achieve set goals in life. Third, after performing their duties or doing what they were destined to accomplish, there is triumph returning home.

In conclusion, by looking into their lives people can find hope and courage hence heroes exist in every individual thus the relevance of the story during the 21 st century. Although many might not be perfect and are prone to mistakes, they can all stand for their convictions and make a change in the community. Lastly, the ideas remain relevant in the present since people undergo continuous journeys in form of challenges throughout their lives and aspire to triumph over the obstacles.

Hamby, Z. (2019). The hero’s guidebook: Creating your own hero’s journey . Creative English Teacher Press.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, February 20). Hero’s Journey in the 21st Century. https://ivypanda.com/essays/heros-journey-in-the-21st-century/

"Hero’s Journey in the 21st Century." IvyPanda , 20 Feb. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/heros-journey-in-the-21st-century/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Hero’s Journey in the 21st Century'. 20 February.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Hero’s Journey in the 21st Century." February 20, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/heros-journey-in-the-21st-century/.

1. IvyPanda . "Hero’s Journey in the 21st Century." February 20, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/heros-journey-in-the-21st-century/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Hero’s Journey in the 21st Century." February 20, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/heros-journey-in-the-21st-century/.

- Gilgamesh: The Hero’s Journey by Joseph Campbell (The Monomyth)

- Movie Luc Skywalker as an Archetypal Warrior Hero

- Anakin Skywalker and Borderline Personality Disorder

- Siddhartha’s Monomyth: Journey to Self-Knowledge

- "Speckled Trout" by Ron Rash

- Interweaving Conflict in "Star Wars" Series' Plot

- Myth Analysis: "Star Wars" and "Tristan and Isolde"

- Campbell's "The Hero With a Thousand Faces"

- Stress Among College Students: Causes, Effects and Overcomes

- “Young Goodman Brown” and “The Alchemist”: Comparison

- "Waiting for the Barbarians" by J. M. Coetzee

- The Dismissal of Miss Ruth Brown Book by Robbins

- Rhetorical Awareness in the First Chapters of “Maus” by Spiegelman

- The Use of Dark Symbolism in "Othello" and "Paradise Lost"

- "Bhagavad Gita": The Reading Reflection

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

34 Your Hero’s Journey: Telling Stories that Matter

Your hero’s journey: telling stories that matter.

By Liza Long

I teach a popular online course at the College of Western Idaho called “Survey of World Mythology.” [1] Every semester, my students start the course thinking that they are going to learn about Zeus, Hera, and maybe Thor—and in all fairness, Thor is why I initially wanted to teach the course.

About three weeks in, we get to the part where I introduce Jesus as just one of many examples from world religions of the “dying god” archetype, and there’s the delicious sound of young minds being blown. “What? We’re reading Christian scriptures as myths?” Well, yes.

Stories, wherever they come from, have power. Stories can shape our cultures—and our individual stories can shape our values and our sense of meaning in a world that might otherwise feel like pure chaos.

A possibly spurious [2] quote attributed to British novelist John Gardner famously asserts that there are only two basic stories in the entire world: the hero’s journey, and a stranger walks into town. Today, we’re going to talk about the first kind of story.

In my world mythology class, I spend an entire unit on the hero’s journey. This universal archetype, a story that exists across all world cultures, was described by anthropologist Joseph Campbell in his seminal 1949 work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces. The book heavily influenced George Lucas—so I guess we have Campbell to thank for Star Wars (well, at least the good movies, the ones that you all know as four, five, and six) [3] .

What is it about the hero’s journey that makes it such a powerful story for pretty much every human being?

Joseph Campbell outlines 17 stages of his monomyth [4] —but we’ll be here all day if we try to get through all of them, and I know some of you have a life outside of class. So I’d like to focus on just three elements of the hero’s journey and consider how these elements apply to the stories we are telling about ourselves in the world, right now:

- Answering the Call

- The Belly of the Whale

- Ultimate Boon/Freedom to Live

Let’s Start with Answering the Call.

Here you are, minding your own business. Maybe you’re working a desk job. Maybe you are surrounded by small children who are continually asking you “why?” and demanding peanut butter and honey sandwiches. Maybe you’re a modern day Jonah, preaching to people who comfortably agree with you, your Facebook friends, your book club group, your liberal or conservative friends.

Suddenly, everything changes. The telephone rings. An email hits your inbox. You see a social media message from a long-lost high school friend.

Campbell says that the call to adventure is:

to a forest, a kingdom underground, beneath the waves, or above the sky, a secret island, lofty mountaintop, or profound dream state; but it is always a place of strangely fluid and polymorphous beings, unimaginable torments, super human deeds, and impossible delight. The hero can go forth of his own volition to accomplish the adventure, as did Theseus when he arrived in his father’s city, Athens, and heard the horrible history of the Minotaur; or he may be carried or sent abroad by some benign or malignant agent as was Odysseus, driven about the Mediterranean by the winds of the angered god, Poseidon. The adventure may begin as a mere blunder… or still again, one may be only casually strolling when some passing phenomenon catches the wandering eye and lures one away from the frequented paths of man.” [5]

When did the call come to you? How did you answer?

If you’re like me, the call has come many times, and I’ve answered in different ways. Sometimes I’ve been like Jonah—Run away! Sometimes I’ve proudly crossed the thresholds and stormed the barricades. But my most important calls have been the last kind Campbell describes—the calling by accident. When an anonymous blog I wrote about parenting a child who had a then undiagnosed mental illness, titled “I Am Adam Lanza’s Mother,” [6] went suddenly viral in 2012, I wanted to run away. But I answered the call. I put my name on the story and told our family’s truth about just how hard it is to raise a child who has mental illness, without a village to support us.

Think for a moment about an accident in your life that in hindsight, changed everything. What truths do you need to tell?

Next, let’s look at the Belly of the Whale.

This idea comes straight from the Judeo-Christian tradition and the story of Jonah and the whale. I think it’s important to remember that, like Jonah, whether or not we accept the call, we can and probably will still end up in the fish’s belly at some point in our lives.

But it’s not as bad as you think. In fact, Campbell describes the image as one of rebirth. He says:

The hero… is swallowed into the unknown and would appear to have died. This popular motif gives emphasis to the lesson that the passage of the threshold is a form of self-annihilation. Instead of passing outward, beyond the confines of the visible world, the hero goes inward, to be born again. [7]

The belly of the whale is where we have to do the hard work that accepting the call requires of us. I suspect that it’s where many of us are right now.

According to NBC News :

Across America today, rates of depression and anxiety are rising dramatically. A 2018 Blue Cross study found that depression diagnosis rates had increased by 33% since 2013—and that’s for people who have health insurance. Our teenagers are especially hard hit, with experts blaming everything from social media to video games to the loss of community. [8]

In the belly of the whale, we are alone, and we feel helpless. Do you feel helpless right now? Does the endless and exhausting news cycle—children in cages, women’s reproductive rights under threat, journalists murdered, migrant caravans—feel overwhelming to you?

I think that collectively, what we’re really experiencing is a cultural belly of the whale. We wanted something different for our country, and for ourselves. We wanted the American Dream, but now we just have to pay the bills, and we are tired.