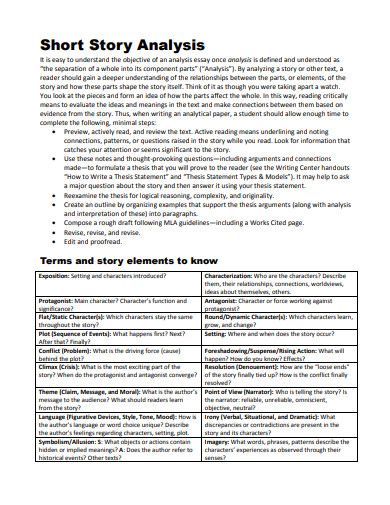

How to Write a Short Story: The Short Story Checklist

Rosemary Tantra Bensko and Sean Glatch | November 17, 2023 | 6 Comments

The short story is a fiction writer’s laboratory: here is where you can experiment with characters, plots, and ideas without the heavy lifting of writing a novel. Learning how to write a short story is essential to mastering the art of storytelling . With far fewer words to worry about, storytellers can make many more mistakes—and strokes of genius!—through experimentation and the fun of fiction writing.

Nonetheless, the art of writing short stories is not easy to master. How do you tell a complete story in so few words? What does a story need to have in order to be successful? Whether you’re struggling with how to write a short story outline, or how to fully develop a character in so few words, this guide is your starting point.

Famous authors like Virginia Woolf, Haruki Murakami, and Agatha Christie have used the short story form to play with ideas before turning those stories into novels. Whether you want to master the elements of fiction, experiment with novel ideas, or simply have fun with storytelling, here’s everything you need on how to write a short story step by step.

The Core Elements of a Short Story

There’s no secret formula to writing a short story. However, a good short story will have most or all of the following elements:

- A protagonist with a certain desire or need. It is essential for the protagonist to want something they don’t have, otherwise they will not drive the story forward.

- A clear dilemma. We don’t need much backstory to see how the dilemma started; we’re primarily concerned with how the protagonist resolves it.

- A decision. What does the protagonist do to resolve their dilemma?

- A climax. In Freytag’s Pyramid , the climax of a story is when the tension reaches its peak, and the reader discovers the outcome of the protagonist’s decision(s).

- An outcome. How does the climax change the protagonist? Are they a different person? Do they have a different philosophy or outlook on life?

Of course, short stories also utilize the elements of fiction , such as a setting , plot , and point of view . It helps to study these elements and to understand their intricacies. But, when it comes to laying down the skeleton of a short story, the above elements are what you need to get started.

Note: a short story rarely, if ever, has subplots. The focus should be entirely on a single, central storyline. Subplots will either pull focus away from the main story, or else push the story into the territory of novellas and novels.

The shorter the story is, the fewer of these elements are essentials. If you’re interested in writing short-short stories, check out our guide on how to write flash fiction .

How to Write a Short Story Outline

Some writers are “pantsers”—they “write by the seat of their pants,” making things up on the go with little more than an idea for a story. Other writers are “plotters,” meaning they decide the story’s structure in advance of writing it.

You don’t need a short story outline to write a good short story. But, if you’d like to give yourself some scaffolding before putting words on the page, this article answers the question of how to write a short story outline:

https://writers.com/how-to-write-a-story-outline

How to Write a Short Story Step by Step

There are many ways to approach the short story craft, but this method is tried-and-tested for writers of all levels. Here’s how to write a short story step by step.

1. Start With an Idea

Often, generating an idea is the hardest part. You want to write, but what will you write about?

What’s more, it’s easy to start coming up with ideas and then dismissing them. You want to tell an authentic, original story, but everything you come up with has already been written, it seems.

Here are a few tips:

- Originality presents itself in your storytelling, not in your ideas. For example, the premise of both Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Ostrovsky’s The Snow Maiden are very similar: two men and two women, in intertwining love triangles, sort out their feelings for each other amidst mischievous forest spirits, love potions, and friendship drama. The way each story is written makes them very distinct from one another, to the point where, unless it’s pointed out to you, you might not even notice the similarities.

- An idea is not a final draft. You will find that exploring the possibilities of your story will generate something far different than the idea you started out with. This is a good thing—it means you made the story your own!

- Experiment with genres and tropes. Even if you want to write literary fiction , pay attention to the narrative structures that drive genre stories, and practice your storytelling using those structures. Again, you will naturally make the story your own simply by playing with ideas.

If you’re struggling simply to find ideas, try out this prompt generator , or pull prompts from this Twitter .

2. Outline, OR Conceive Your Characters

If you plan to outline, do so once you’ve generated an idea. You can learn about how to write a short story outline earlier in this article.

If you don’t plan to outline, you should at least start with a character or characters. Certainly, you need a protagonist, but you should also think about any characters that aid or inhibit your protagonist’s journey.

When thinking about character development, ask the following questions:

- What is my character’s background? Where do they come from, how did they get here, where do they want to be?

- What does your character desire the most? This can be both material or conceptual, like “fitting in” or “being loved.”

- What is your character’s fatal flaw? In other words, what limitation prevents the protagonist from achieving their desire? Often, this flaw is a blind spot that directly counters their desire. For example, self hatred stands in the way of a protagonist searching for love.

- How does your character think and speak? Think of examples, both fictional and in the real world, who might resemble your character.

In short stories, there are rarely more characters than a protagonist, an antagonist (if relevant), and a small group of supporting characters. The more characters you include, the longer your story will be. Focus on making only one or two characters complex: it is absolutely okay to have the rest of the cast be flat characters that move the story along.

Learn more about character development here:

https://writers.com/character-development-definition

3. Write Scenes Around Conflict

Once you have an outline or some characters, start building scenes around conflict. Every part of your story, including the opening sentence, should in some way relate to the protagonist’s conflict.

Conflict is the lifeblood of storytelling: without it, the reader doesn’t have a clear reason to keep reading. Loveable characters are not enough, as the story has to give the reader something to root for.

Take, for example, Edgar Allan Poe’s classic short story The Cask of Amontillado . We start at the conflict: the narrator has been slighted by Fortunato, and plans to exact revenge. Every scene in the story builds tension and follows the protagonist as he exacts this revenge.

In your story, start writing scenes around conflict, and make sure each paragraph and piece of dialogue relates, in some way, to your protagonist’s unmet desires.

4. Write Your First Draft

The scenes you build around conflict will eventually be stitched into a complete story. Make sure as the story progresses that each scene heightens the story’s tension, and that this tension remains unbroken until the climax resolves whether or not your protagonist meets their desires.

Don’t stress too hard on writing a perfect story. Rather, take Anne Lamott’s advice, and “write a shitty first draft.” The goal is not to pen a complete story at first draft; rather, it’s to set ideas down on paper. You are simply, as Shannon Hale suggests, “shoveling sand into a box so that later [you] can build castles.”

5. Step Away, Breathe, Revise

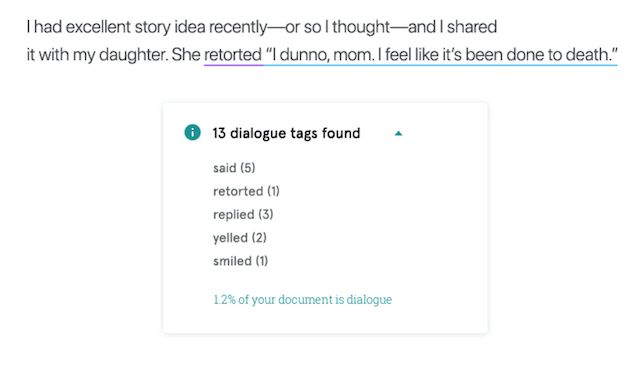

Whenever Stephen King finishes a novel, he puts it in a drawer and doesn’t think about it for 6 weeks. With short stories, you probably don’t need to take as long of a break. But, the idea itself is true: when you’ve finished your first draft, set it aside for a while. Let yourself come back to the story with fresh eyes, so that you can confidently revise, revise, revise .

In revision, you want to make sure each word has an essential place in the story, that each scene ramps up tension, and that each character is clearly defined. The culmination of these elements allows a story to explore complex themes and ideas, giving the reader something to think about after the story has ended.

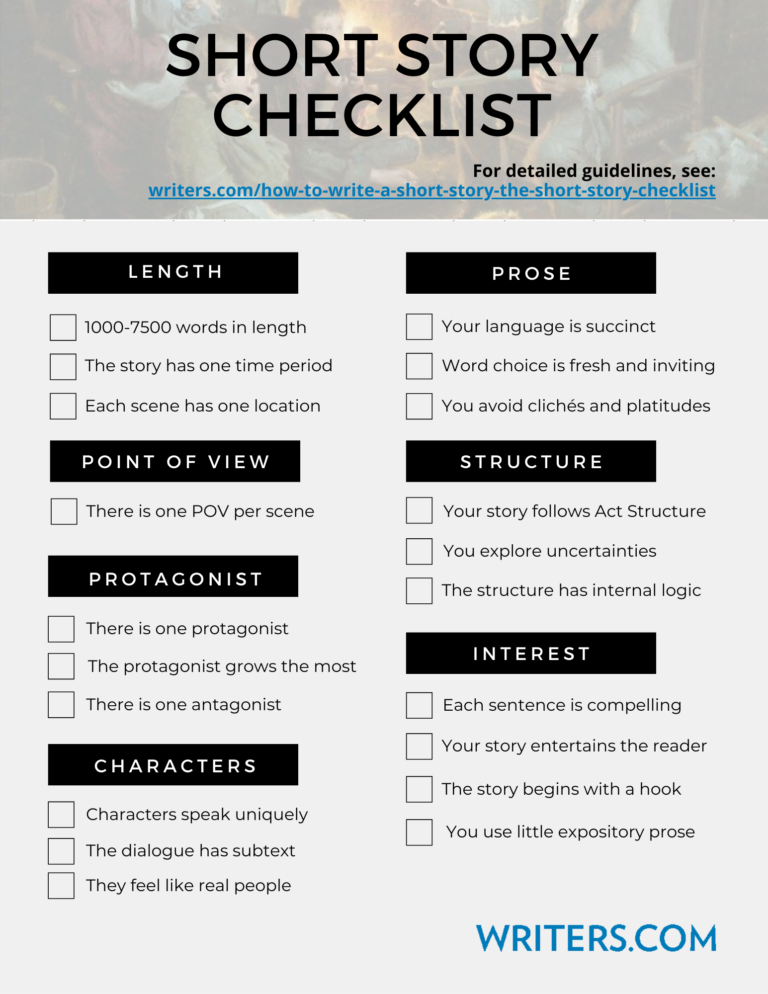

6. Compare Against Our Short Story Checklist

Does your story have everything it needs to succeed? Compare it against this short story checklist, as written by our instructor Rosemary Tantra Bensko.

Below is a collection of practical short story writing tips by Writers.com instructor Rosemary Tantra Bensko . Each paragraph is its own checklist item: a core element of short story writing advice to follow unless you have clear reasons to the contrary. We hope it’s a helpful resource in your own writing.

Update 9/1/2020: We’ve now made a summary of Rosemary’s short story checklist available as a PDF download . Enjoy!

Click to download

How to Write a Short Story: Length and Setting

Your short story is 1000 to 7500 words in length.

The story takes place in one time period, not spread out or with gaps other than to drive someplace, sleep, etc. If there are those gaps, there is a space between the paragraphs, the new paragraph beginning flush left, to indicate a new scene.

Each scene takes place in one location, or in continual transit, such as driving a truck or flying in a plane.

How to Write a Short Story: Point of View

Unless it’s a very lengthy Romance story, in which there may be two Point of View (POV) characters, there is one POV character. If we are told what any character secretly thinks, it will only be the POV character. The degree to which we are privy to the unexpressed thoughts, memories and hopes of the POV character remains consistent throughout the story.

You avoid head-hopping by only having one POV character per scene, even in a Romance. You avoid straying into even brief moments of telling us what other characters think other than the POV character. You use words like “apparently,” “obviously,” or “supposedly” to suggest how non-POV-characters think rather than stating it.

How to Write a Short Story: Protagonist, Antagonist, Motivation

Your short story has one clear protagonist who is usually the character changing most.

Your story has a clear antagonist, who generally makes the protagonist change by thwarting his goals.

(Possible exception to the two short story writing tips above: In some types of Mystery and Action stories, particularly in a series, etc., the protagonist doesn’t necessarily grow personally, but instead his change relates to understanding the antagonist enough to arrest or kill him.)

The protagonist changes with an Arc arising out of how he is stuck in his Flaw at the beginning of the story, which makes the reader bond with him as a human, and feel the pain of his problems he causes himself. (Or if it’s the non-personal growth type plot: he’s presented at the beginning of the story with a high-stakes problem that requires him to prevent or punish a crime.)

The protagonist usually is shown to Want something, because that’s what people normally do, defining their personalities and behavior patterns, pushing them onward from day to day. This may be obvious from the beginning of the story, though it may not become heightened until the Inciting Incident , which happens near the beginning of Act 1. The Want is usually something the reader sort of wants the character to succeed in, while at the same time, knows the Want is not in his authentic best interests. This mixed feeling in the reader creates tension.

The protagonist is usually shown to Need something valid and beneficial, but at first, he doesn’t recognize it, admit it, honor it, integrate it with his Want, or let the Want go so he can achieve the Need instead. Ideally, the Want and Need can be combined in a satisfying way toward the end for the sake of continuity of forward momentum of victoriously achieving the goals set out from the beginning. It’s the encounters with the antagonist that forcibly teach the protagonist to prioritize his Needs correctly and overcome his Flaw so he can defeat the obstacles put in his path.

The protagonist in a personal growth plot needs to change his Flaw/Want but like most people, doesn’t automatically do that when faced with the problem. He tries the easy way, which doesn’t work. Only when the Crisis takes him to a low point does he boldly change enough to become victorious over himself and the external situation. What he learns becomes the Theme.

Each scene shows its main character’s goal at its beginning, which aligns in a significant way with the protagonist’s overall goal for the story. The scene has a “charge,” showing either progress toward the goal or regression away from the goal by the ending. Most scenes end with a negative charge, because a story is about not obtaining one’s goals easily, until the end, in which the scene/s end with a positive charge.

The protagonist’s goal of the story becomes triggered until the Inciting Incident near the beginning, when something happens to shake up his life. This is the only major thing in the story that is allowed to be a random event that occurs to him.

How to Write a Short Story: Characters

Your characters speak differently from one another, and their dialogue suggests subtext, what they are really thinking but not saying: subtle passive-aggressive jibes, their underlying emotions, etc.

Your characters are not illustrative of ideas and beliefs you are pushing for, but come across as real people.

How to Write a Short Story: Prose

Your language is succinct, fresh and exciting, specific, colorful, avoiding clichés and platitudes. Sentence structures vary. In Genre stories, the language is simple, the symbolism is direct, and words are well-known, and sentences are relatively short. In Literary stories, you are freer to use more sophisticated ideas, words, sentence structures and underlying metaphors and implied motifs.

How to Write a Short Story: Story Structure

Your plot elements occur in the proper places according to classical Act Structure so the reader feels he has vicariously gone through a harrowing trial with the protagonist and won, raising his sense of hope and possibility. Literary short stories may be more subtle, with lower stakes, experimenting beyond classical structures like the Hero’s Journey. They can be more like vignettes sometimes, or even slice-of-life, though these types are hard to place in publications.

In Genre stories, all the questions are answered, threads are tied up, problems are solved, though the results of carnage may be spread over the landscape. In Literary short stories, you are free to explore uncertainty, ambiguity, and inchoate, realistic endings that suggest multiple interpretations, and unresolved issues.

Some Literary stories may be nonrealistic, such as with Surrealism, Absurdism, New Wave Fabulism, Weird and Magical Realism . If this is what you write, they still need their own internal logic and they should not be bewildering as to the what the reader is meant to experience, whether it’s a nuanced, unnameable mood or a trip into the subconscious.

Literary stories may also go beyond any label other than Experimental. For example, a story could be a list of To Do items on a paper held by a magnet to a refrigerator for the housemate to read. The person writing the list may grow more passive-aggressive and manipulative as the list grows, and we learn about the relationship between the housemates through the implied threats and cajoling.

How to Write a Short Story: Capturing Reader Interest

Your short story is suspenseful, meaning readers hope the protagonist will achieve his best goal, his Need, by the Climax battle against the antagonist.

Your story entertains. This is especially necessary for Genre short stories.

The story captivates readers at the very beginning with a Hook, which can be a puzzling mystery to solve, an amazing character’s or narrator’s Voice, an astounding location, humor, a startling image, or a world the reader wants to become immersed in.

Expository prose (telling, like an essay) takes up very, very little space in your short story, and it does not appear near the beginning. The story is in Narrative format instead, in which one action follows the next. You’ve removed every unnecessary instance of Expository prose and replaced it with showing Narrative. Distancing words like “used to,” “he would often,” “over the years, he,” “each morning, he” indicate that you are reporting on a lengthy time period, summing it up, rather than sticking to Narrative format, in which immediacy makes the story engaging.

You’ve earned the right to include Expository Backstory by making the reader yearn for knowing what happened in the past to solve a mystery. This can’t possibly happen at the beginning, obviously. Expository Backstory does not take place in the first pages of your story.

Your reader cares what happens and there are high stakes (especially important in Genre stories). Your reader worries until the end, when the protagonist survives, succeeds in his quest to help the community, gets the girl, solves or prevents the crime, achieves new scientific developments, takes over rule of his realm, etc.

Every sentence is compelling enough to urge the reader to read the next one—because he really, really wants to—instead of doing something else he could be doing. Your story is not going to be assigned to people to analyze in school like the ones you studied, so you have found a way from the beginning to intrigue strangers to want to spend their time with your words.

Where to Read and Submit Short Stories

Whether you’re looking for inspiration or want to publish your own stories, you’ll find great literary journals for writers of all backgrounds at this article:

https://writers.com/short-story-submissions

Learn How to Write a Short Story at Writers.com

The short story takes an hour to learn and a lifetime to master. Learn how to write a short story with Writers.com. Our upcoming fiction courses will give you the ropes to tell authentic, original short stories that captivate and entrance your readers.

Rosemary – Is there any chance you could add a little something to your checklist? I’d love to know the best places to submit our short stories for publication. Thanks so much.

Hi, Kim Hanson,

Some good places to find publications specific to your story are NewPages, Poets and Writers, Duotrope, and The Submission Grinder.

“ In Genre stories, all the questions are answered, threads are tied up, problems are solved, though the results of carnage may be spread over the landscape.”

Not just no but NO.

See for example the work of MacArthur Fellow Kelly Link.

[…] How to Write a Short Story: The Short Story Checklist […]

Thank you for these directions and tips. It’s very encouraging to someone like me, just NOW taking up writing.

[…] Writers.com. A great intro to writing. https://writers.com/how-to-write-a-short-story […]

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Looking to publish? Meet your dream editor, designer and marketer on Reedsy.

Find the perfect editor for your next book

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Last updated on Oct 29, 2023

How to Write a Short Story in 9 Simple Steps

This post is written by UK writer Robert Grossmith. His short stories have been widely anthologized, including in The Time Out Book of London Short Stories , The Best of Best Short Stories , and The Penguin Book of First World War Stories . You can collaborate with him on your own short stories here on Reedsy .

The joy of writing short stories is, in many ways, tied to its limitations. Developing characters, conflict, and a premise within a few pages is a thrilling challenge that many writers relish — even after they've "graduated" to long-form fiction.

In this article, I’ll take you through the process of writing a short story, from idea conception to the final draft.

How to write a short story:

1. Know what a short story is versus a novel

2. pick a simple, central premise, 3. build a small but distinct cast of characters, 4. begin writing close to the end, 5. shut out your internal editor, 6. finish the first draft, 7. edit the short story, 8. share the story with beta readers, 9. submit the short story to publications.

But first, let’s talk about what makes a short story different from a novel.

The simple answer to this question, of course, is that the short story is shorter than the novel, usually coming in at between, say, 1,000-15,000 words. Any shorter and you’re into flash fiction territory. Any longer and you’re approaching novella length .

As far as other features are concerned, it’s easier to define the short story by what it lacks compared to the novel . For example, the short story usually has:

- fewer characters than a novel

- a single point of view, either first person or third person

- a single storyline without subplots

- less in the way of back story or exposition than a novel

If backstory is needed at all, it should come late in the story and be kept to a minimum.

It’s worth remembering too that some of the best short stories consist of a single dramatic episode in the form of a vignette or epiphany.

GET ACCOUNTABILITY

Meet writing coaches on Reedsy

Industry insiders can help you hone your craft, finish your draft, and get published.

A short story can begin life in all sorts of ways.

It may be suggested by a simple but powerful image that imprints itself on the mind. It may derive from the contemplation of a particular character type — someone you know perhaps — that you’re keen to understand and explore. It may arise out of a memorable incident in your own life.

For example:

- Kafka began “The Metamorphosis” with the intuition that a premise in which the protagonist wakes one morning to find he’s been transformed into a giant insect would allow him to explore questions about human relationships and the human condition.

- Herman Melville’s “Bartleby the Scrivener” takes the basic idea of a lowly clerk who decides he will no longer do anything he doesn’t personally wish to do, and turns it into a multi-layered tale capable of a variety of interpretations.

When I look back on some of my own short stories, I find a similar dynamic at work: a simple originating idea slowly expands to become something more nuanced and less formulaic.

So how do you find this “first heartbeat” of your own short story? Here are several ways to do so.

Experiment with writing prompts

Eagle-eyed readers will notice that the story premises mentioned above actually have a great deal in common with writing prompts like the ones put forward each week in Reedsy’s short story competition . Try it out! These prompts are often themed in a way that’s designed to narrow the focus for the writer so that one isn’t confronted with a completely blank canvas.

Turn to the originals

Take a story or novel you admire and think about how you might rework it, changing a key element. (“Pride and Prejudice and Vampires” is perhaps an extreme product of this exercise.) It doesn’t matter that your proposed reworking will probably never amount to more than a skimpy mental reimagining — it may well throw up collateral narrative possibilities along the way.

Keep a notebook

Finally, keep a notebook in which to jot down stray observations and story ideas whenever they occur to you. Again, most of what you write will be stuff you never return to, and it may even fail to make sense when you reread it. But lurking among the dross may be that one rough diamond that makes all the rest worthwhile.

Like I mentioned earlier, short stories usually contain far fewer characters than novels. Readers also need to know far less about the characters in a short story than we do in a novel (sometimes it’s the lack of information about a particular character in a story that adds to the mystery surrounding them, making them more compelling).

Yet it remains the case that creating memorable characters should be one of your principal goals. Think of your own family, friends and colleagues. Do you ever get them confused with one another? Probably not.

Your dramatis personae should be just as easily distinguishable from one another, either through their appearance, behavior, speech patterns, or some other unique trait. If you find yourself struggling, a character profile template like the one you can download for free below is particularly helpful in this stage of writing.

FREE RESOURCE

Reedsy’s Character Profile Template

A story is only as strong as its characters. Fill this out to develop yours.

- “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman features a cast of two: the narrator and her husband. How does Gilman give her narrator uniquely identifying features?

- “The Tell-Tale Heart” by Edgar Allan Poe features a cast of three: the narrator, the old man, and the police. How does Poe use speech patterns in dialogue and within the text itself to convey important information about the narrator?

- “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” by Flannery O’Connor is perhaps an exception: its cast of characters amounts to a whopping (for a short story) nine. How does she introduce each character? In what way does she make each character, in particular The Misfit, distinct?

He’s right: avoid the preliminary exposition or extended scene-setting. Begin your story by plunging straight into the heart of the action. What most readers want from a story is drama and conflict, and this is often best achieved by beginning in media res . You have no time to waste in a short story. The first sentence of your story is crucial, and needs to grab the reader’s attention to make them want to read on.

One way to do this is to write an opening sentence that makes the reader ask questions. For example, Kingsley Amis once said, tongue-in-cheek, that in the future he would only read novels that began with the words: “A shot rang out.”

This simple sentence is actually quite telling. It introduces the stakes: there’s an immediate element of physical danger, and therefore jeopardy for someone. But it also raises questions that the reader will want answered. Who fired the shot? Who or what were they aiming at, and why? Where is this happening?

We read fiction for the most part to get answers to questions. For example, if you begin your story with a character who behaves in an unexpected way, the reader will want to know why he or she is behaving like this. What motivates their unusual behavior? Do they know that what they’re doing or saying is odd? Do they perhaps have something to hide? Can we trust this character?

As the author, you can answer these questions later (that is, answer them dramatically rather than through exposition). But since we’re speaking of the beginning of a story, at the moment it’s enough simply to deliver an opening sentence that piques the reader’s curiosity, raises questions, and keeps them reading.

“Anything goes” should be your maxim when embarking on your first draft.

FREE COURSE

How to Craft a Killer Short Story

From pacing to character development, master the elements of short fiction.

By that, I mean: kill the editor in your head and give your imagination free rein. Remember, you’re beginning with a blank page. Anything you put down will be an improvement on what’s currently there, which is nothing. And there’s a prescription for any obstacle you might encounter at this stage of writing.

- Worried that you’re overwriting? Don’t worry. It’s easier to cut material in later drafts once you’ve sketched out the whole story.

- Got stuck, but know what happens later? Leave a gap. There’s no necessity to write the story sequentially. You can always come back and fill in the gap once the rest of the story is complete.

- Have a half-developed scene that’s hard for you to get onto the page? Write it in note form for the time being. You might find that it relieves the pressure of having to write in complete sentences from the get-go.

Most of my stories were begun with no idea of their eventual destination, but merely an approximate direction of travel. To put it another way, I’m a ‘pantser’ (flying by the seat of my pants, making it up as I go along) rather than a planner. There is, of course, no right way to write your first draft. What matters is that you have a first draft on your hands at the end of the day.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of the ending of a short story : it can rescue an inferior story or ruin an otherwise superior one.

If you’re a planner, you will already know the broad outlines of the ending. If you’re a pantser like me, you won’t — though you’ll hope that a number of possible endings will have occurred to you in the course of writing and rewriting the story!

In both cases, keep in mind that what you’re after is an ending that’s true to the internal logic of the story without being obvious or predictable. What you want to avoid is an ending that evokes one of two reactions:

- “Is that it?” aka “The author has failed to resolve the questions raised by the story.”

- “WTF!” aka “This ending is simply confusing.”

Like Truman Capote said, “Good writing is rewriting.”

Once you have a first draft, the real work begins. This is when you move things around, tightening the nuts and bolts of the piece to make sure it holds together and resembles the shape it took in your mind when you first conceived it.

In most cases, this means reading through your first draft again (and again). In this stage of editing , think to yourself:

- Which narrative threads are already in place?

- Which may need to be added or developed further?

- Which need to perhaps be eliminated altogether?

All that’s left afterward is the final polish . Here’s where you interrogate every word, every sentence, to make sure it’s earned its place in the story:

- Is that really what I mean?

- Could I have said that better?

- Have I used that word correctly?

- Is that sentence too long?

- Have I removed any clichés?

Trust me: this can be the most satisfying part of the writing process. The heavy lifting is done, the walls have been painted, the furniture is in place. All you have to do now is hang a few pictures, plump the cushions and put some flowers in a vase.

Eventually, you may reach a point where you’ve reread and rewritten your story so many times that you simply can’t bear to look at it again. If this happens, put the story aside and try to forget about it.

When you do finally return to it, weeks or even months later, you’ll probably be surprised at how the intervening period has allowed you to see the story with a fresh pair of eyes. And whereas it might have felt like removing one of your own internal organs to cut such a sentence or paragraph before, now it feels like a liberation.

The story, you can see, is better as a result. It was only your bloated appendix you removed, not a vital organ.

It’s at this point that you should call on the services of beta readers if you have them. This can be a daunting prospect: what if the response is less enthusiastic than you’re hoping for? But think about it this way: if you’re expecting complete strangers to read and enjoy your story, then you shouldn’t be afraid of trying it out first on a more sympathetic audience.

This is also why I’d suggest delaying this stage of the writing process until you feel sure your story is complete. It’s one thing to ask a friend to read and comment on your new story. It’s quite another thing to return to them sometime later with, “I’ve made some changes to the story — would you mind reading it again?”

So how do you know your story’s really finished? This is a question that people have put to me. My reply tends to be: I know the story’s finished when I can’t see how to make it any better.

This is when you can finally put down your pencil (or keyboard), rest content with your work for a few days, then submit it so that people can read your work. And you can start with this directory of literary magazines once you're at this step.

The truth is, in my experience, there’s actually no such thing as a final draft. Even after you’ve submitted your story somewhere — and even if you’re lucky enough to have it accepted — there will probably be the odd word here or there that you’d like to change.

Don’t worry about this. Large-scale changes are probably out of the question at this stage, but a sympathetic editor should be willing to implement any small changes right up to the time of publication.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Bring your short stories to life

Fuse character, story, and conflict with tools in the Reedsy Book Editor. 100% free.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

How to Write a Short Story: 5 Major Steps from Start to Finish

by Sarah Gribble | 81 comments

Do you want to learn how to write a short story ? Maybe you'd like to try writing a short story instead of a novel-length work, or maybe you're hoping to get more writing practice without the lengthy time commitment that a novel requires.

The reality of writing stories? Not every short story writer wants to write a novel, but every novelist can benefit from writing short stories. However, short stories and novels are different—so naturally, how you write them has its differences, too.

Short stories are often a fiction writer’s first introduction to writing, but they can be frustrating to write and difficult to master. How do you fit everything that makes a great story into something so short?

And then, once you do finish a short story you’re proud of, what do you do with it?

That's what we'll cover in this article, along with additional resources I'll link to that will help you get started step-by-step with shorts.

Short Stories Made Me a Better Writer

I fell into writing short stories when I first started writing.

I'd written a book , and it was terrible. But it opened up my mind and I kept having all these story ideas I just had to get out.

Before long, I had dozens of stories and within about two years, I had around three dozen of them published traditionally. That first book went nowhere, by the way. But my short stories surely did.

And I learned a whole lot about the writing craft because I spent so much time practicing writing with my short stories. This is why, whether you want to make money as a short story writer or experiment writing them, I think writing short stories is important for every writer who wants to become a novelist.

But how do you write a short story? And what do you do afterwards? I hope that by sharing my personal experiences and suggestions, I can help you write your own short stories with confidence.

Why Should You Write Short Stories?

I get a lot of pushback when I suggest new writers should write short stories.

Everyone wants to write a book. (Okay, maybe not everyone, but if you ask a hundred people if they’d like to write one, I’d bet seventy-something of them would say yes.) Anthologies and short story collections don’t make a ton of money because no one really wants to read them. So why waste time writing short stories when books are what people read ?

There are three main reasons you should be a short story writer:

1. Training

Short stories help you hone your writing skills .

Short stories are often only one scene and about one character. That’s a level of focus you can’t have in a novel. Writing short stories forces you to focus on writing clearly and concisely while still making a scene entertaining.

You’re working with the basic level of structure here (a scene) and learning to perfect it .

Short stories are a place to experiment with your creative process, to play with character development techniques, to dabble in different kinds of writing styles.

And you're learning what a finished story feels like. So many aspiring novelists have only half-done drafts in drawers. A short is training yourself to finish.

2. Building contacts and readers

Most writers I know do not want to hear this, but this whole writing thing is the same as any other industry: if you want to make it, you better network.

When my first book, Surviving Death , was released, I had hundreds of people on my launch team. How? I’d had about three dozen short stories published traditionally by that time. I’d gathered a readership base, and not only that, I’d become acquainted with some fellow writers in my genre along the way. And those people were more than willing to help me get the word out about my book.

You want loyal readers and you want friends in the industry. And the way to get those is to continuously be writing.

Writing is like working out. If you take a ton of time off, you’re going to hurt when you get back into it.

It’s a little difficult to be working on a novel all the time. Most writers have one or two in them a year, and those aren’t written without a bit of a break in between.

Short story writing helps you keep up your writing habit , or develop one, and they make for a nice break in between larger projects.

I always write short stories between novels, and even between drafts of my novels. It keeps me going and puts use to all the random story ideas I had while working on the larger project. I've found over the years that keeping up the writing habit is the only way to actually keep yourself in “writer mode.”

All the cool kids are doing it. Stephen King, Neil Gaiman, Edgar Allan Poe, Kurt Vonnegut, Margaret Atwood . . . Google your favorite writers and they probably have a short story collection or two out there. Most successful authors have cut their teeth on short stories.

What is a Short Story?

Now that you know why you should be writing short stories, let’s talk about what a short story is. This might seem obvious, but it’s a question I’ve gotten a lot. A short story is short, right? Essentially, yes. But how short is short?

You can Google how long a short story is and get a bunch of different answers. There are a lot of different editors out there running a lot of different anthologies, magazines, ezines, podcasts, you name it. They all have slightly different definitions of what a short story is because they all have slightly different needs when it comes to providing content on their platform and meeting the expectations of their audiences.

A podcast, for instance, often wants a story to take up about thirty minutes of airtime. They know how long it takes their producers to read a story, so that thirty minutes means they’re looking for a very specific word count. An ezine might aim for a certain estimated reading time. A magazine or anthology might have a certain number of pages they’re trying to fill.

Everyone has a different definition of how short a short story is, so for the purpose of this series, I’m going to be broad in my definition of a short story.

What qualifies as a short story?

A short story word count normally falls somewhere between 1,000 words and 10,000 words. If you’re over ten thousand, you’re running into novelette territory, though some publications consider up to 20,000 words to be a short story. If you’re under a thousand words, you’re looking at flash fiction.

The sweet spot is between 2,000 and 5,000 words. The majority of short stories I’ve had published were between 2,500 words and 3,500 words.

That’s not a lot of words, and you’ve got a lot to fit in—backstory, world-building, a character arc—in that tiny amount of space. (A book, by the way, is normally 60,000 to 90,000 words or longer. Big difference.)

A short story is one to three scenes. That’s it. Think of it as a “slice of life,” as in someone peeked into your life for maybe an hour or two and this is what they saw.

You’re not going to flesh out every detail about your characters. (I normally don’t even know the last names of my short story characters, and it doesn’t matter.) You’re not trying to build a Tolkien-level world. You don’t need to worry about subplots.

To focus your writing, think of a short story as a short series of events happening to a single character. The rest of the cast of characters should be small.

How to Write a Short Story: The Short Version

Throughout this blog series, I’ll take a deep dive into the process of writing short stories. If you’re looking for the fast answer, here it is:

- Write the story in one sitting.

- Take a break.

- Edit with a mind for brevity.

- Get feedback and do a final edit.

Write the story in one sitting

For the most part, short stories are meant to be read in one sitting, so it makes sense that you should write them in one sitting.

Obviously, if you’re in the 10K range, that’s probably going to take more than one writing session, but a 2,500-word short story can easily be written in one sitting. This might seem a little daunting, but you’ll find your enthusiasm will drive you to the ending and your story will flow better for it.

You’re not aiming for prize-winning writing during this stage. You’re aiming to get the basic story out of your head and on paper.

Forget about grammar . Forget about beautiful prose. Forget about even making a ton of sense.

You’re not worrying about word count at this stage, either. Don’t research and don’t pause over trying to find the exact right word. Don't agonize over the perfect story title.

Just get the basic story out. You can’t edit a blank page.

Take a break

Don’t immediately begin the editing process. After you’ve written anything, books included, you need to take a step back . Your brain needs to shift from “writer mode” to “reader mode.” With a short story, I normally recommend a three-day break.

If you have research to do, this is the time to do it, though I highly recommend not thinking about your story at all.

The further away you can get from it, the better you’ll edit.

Edit with a mind for brevity

Now that you’ve had a break, you’re ready to come back with a vengeance. This is the part where you “kill your darlings” and have absolutely no mercy for the story you produced less than a week ago. The second draft is where you get critical.

Remember we’re writing a short story here, not a novel. You don’t have time to go into each and every detail about your characters’ lives. You don’t have time for B-plots, a ton of characters, or Stephen King-level droning on.

Short stories should have a beginning, a middle, and an end, though. They’re short, but they’re still stories.

As you edit , ask yourself if each bit of backstory, world building, and anything else is something your reader needs to know. If they do, do they need to know it right at that moment? If they don’t, cut it.

Get feedback

If this is your first time letting other people see your writing, this can be a scary step. No one wants to be given criticism. But getting feedback is the most important step in the writing process next to writing.

The more eyes you can get on a piece of writing, the better.

I highly recommend getting feedback from someone who knows about writing, not your mother or your best friend. People we love are great, but they love you and won’t give you honest feedback. If you want praise, go to them. If you want to grow as a writer, join a writing community and get feedback from other writers.

When you’ve gotten some feedback from a handful of people, make any changes you deem necessary and do a final edit for smaller issues like grammar and punctuation.

Here at The Write Practice, we’re huge fans of publishing your work . In fact, we don’t quite consider a story finished until it’s published.

Whether you’re going the traditional route and submitting your short story to anthologies and magazines, or you’re more into self- publishing , don’t let your story languish on your computer. Get it out into the world so you can build your reader base.

And it’s pretty cool getting to say you’re a published author.

That’s the short version of how to go about writing short stories. Throughout this series, I’ll be taking a more in-depth look at different elements of these steps. Stick with me throughout the series, and you’ll have a short story of your own ready to publish by the end.

A Preview of My How to Write a Short Story Series

My goal in this blog series is to walk you through the process of writing a short story from start to finish and then point you in the right direction for getting that story published.

By the end of this series, you’ll have a story ready to submit to publishers and a plan for how to submit.

Below is a list of topics I’ll be covering during this blog series. Keep coming back as these topics are updated over the coming months.

How to Come up With Ideas For Short Stories

Creative writing is like a muscle: use it or lose it. Coming up with ideas is part of the development of that muscle. In this post , I’ll go over how to train your mind to put out ideas consistently.

How to Plan a Short Story (Without Really Planning It)

Short stories often don’t require extensive planning. They’re short, after all. But a little bit of outlining can help. Don’t worry, I’m mostly a pantser! I promise this won’t be an intense method of planning. It will, however, give you a start with the elements of story structure—and motivation to get you to finish (and publish) your story. Read this article to see how a little planning can go a long way toward writing a successful story.

What You Need in a Short Story/Elements of a Short Story

One of the biggest mistakes I see from new writers is their short stories aren’t actually stories. They're often missing a climax, don't have an ending, or just ramble on in a stream-of-consciousness way without any story structure. In this article , I’ll show you what you need to make sure your short is a complete story.

Writing Strategies for Short Stories

The writing process varies from person to person, and often from project to project. In this blog , I’ll talk about different writing strategies you can use to write short stories.

How to Edit a Short Story

Editing is my least favorite part of writing. It’s overwhelming and often tedious. I’ll talk about short story editing strategies to take the confusion out of the process, and ensure you can edit with confidence.Learn how to confidently edit your story here .

Writing a Better Short Story

Short stories are their own art form, mainly because of the small word count. In this post, I’ll discuss ways to write a better short, including fitting everything you want and need into that tiny word count.

Weaving backstory and worldbuilding into your story without overdoing it. Remember, you don't need every detail about the world or a character's life in a short story—but the setting shouldn't be ignored. How your protagonist interacts with it should be significant and interesting.

How to Submit a Short Story to Publications

There are plenty of literary magazines, ezines, anthologies, etc. out there that accept short stories for publication (and you can self-publish your stories, too). In this article, I’ll demystify the submission process so you can submit your own stories to publications and start getting your work out there. You'll see your work in a short story anthology soon after using the tips in this article !

Professionalism in the Writing Industry

Emotions can run high when you put your work out there for others to see. In this article, I’ll talk about what’s expected of you in this profession and how to maintain professionalism so that you don't shoot yourself in the foot when you approach publishers, editors, and agents.

Write, Write, Write!

As you follow this series, I challenge you to begin writing at least one short story a week. I'll be giving you in-depth tips on creating a compelling story as we go along, but for now, I want you to write. That habit is the hardest thing to start and the hardest thing to keep up.

You may not use all the stories you're going to write over the next months. You may hate them and never want them to see the light of day. But you can't get better if you don't practice. Start practicing now.

As Ray Bradbury says:

“Write a short story every week. It's not possible to write 52 bad short stories in a row.”

When it comes to writing short stories, what do you find most challenging? Let me know in the comments .

For today’s practice, let’s just take on Step #1 (and begin tackling the challenge I laid down a moment ago): Write the basic story idea, the gist of the premise, as you’d tell it to a friend. Don’t think about it too much, and don’t worry about going into detail. Just write.

Write for fifteen minutes .

When your time is up, share your practice in the Pro Practice Workshop. And after you post, please be sure to give feedback to your fellow writers.

Happy writing!

Sarah Gribble

Sarah Gribble is the author of dozens of short stories that explore uncomfortable situations, basic fears, and the general awe and fascination of the unknown. She just released Surviving Death , her first novel, and is currently working on her next book.

Follow her on Instagram or join her email list for free scares.

Work with Sarah Gribble?

Bestselling author with over five years of coaching experience. Sarah Gribble specializes in working with Dark Fantasy, Fantasy, Horror, Speculative Fiction, and Thriller books. Sound like a good fit for you?

81 Comments

! ! ! JACKPOT ! ! !

I mean it! Finally, after months and months of reading literally hundreds of blog posts and comments, I find that you have addressed the writing of short stories in a manner that is direct, practical, and clear.

It is not my intention to write TGAN. It never was.

I hope, rather, to entertain with short stories drawn from the experiences of my living. This post has illuminated a clear path through the (often valuable, genuinely valid, but – for me, anyway – not-directly-relevant) facts, experiences and anecdotes of other writers and would-be practitioners of the art that all seem focused on novel-length work.

I would encourage you to entertain the possibility of more posts on the art form and production of short stories.

Wow, Bob. That’s so good to hear.

Speaking of short story articles, have you read my book Let’s Write a Short Story? You might enjoy it! Check out letswriteashortstory.com.

The picture on how to write a short story is pretty much how I wrote my first one and have started my second. I had my first one critiqued, then revised it to the critters suggestions (they made perfect sense) and my story has improved considerably. I thought I was being lame on how I came to write them, but I see now, I accidentally stumbled on the formula for writing. Thanks Joe. I’m writing easier now.

Love that, Susan. Like Neil said, there is no formula. You have to write the story the way it wants to be written. But I find that I need structure to keep myself motivated and moving, so this process usually helps me stay focused. Glad you’re finding the writing process easier!

This is such a great post, Joe! I used to be primarily a short story writer but have been working on a novel for so long I feel as though I can’t remember how short stories work – but this brought it all back, and in a much better more clear cut manner than my old ways! I used to meander through a short story like a blind woman in the dark until I bumped into the ending – but I had a lot more time on my hands to do such meandering than I do now, so I’ll definitely give this technique a try!

I’ve done the same, Dana. However haltingly and messy my process has been, though, it usually follows this rough pattern I listed above. Has that been true for you as well?

I was always a “pantser” for stories, and would start with a concept or opening scene, and then feel my way through. It could take weeks to get a first draft. Then I’d edit. The first step of yours blew me away, the idea of writing a “story” without any pressure to make it great, to just get to the gist of it, is pretty brilliant. I often put so much pressure on myself to get it right on the page that it slows me down. I’m already at work (in my head) on part 1 of a story I’ve been meaning to rewrite, and I feel very confident about it thanks to your advice 🙂

There is nothing wrong with pantsing it! I would be labeled a “pantser” but as I tell every one, it only looks that way. Outlines form around character so quickly in my head, it seems to be unplanned, but that is not true. I always have an outline, I just don’t spend a lot of time on it. The important thing is to write to end before doing any re-writing!

I’ve never been a big fan of writing short stories. They’ve always seemed like “a good start on a novel-length story”.

But your outline for writing a short story has me rethinking that philosophy. I may just give it a try.

Thanks for a new idea on a Saturday morning!

DO IT! And let me know how it goes, Carrie. 🙂

Agreed! ….on a Saturday afternoon! Fabulous tips to try. Thanks, Joe.

Short stories are an important marketing tool for all writers. And so is flash fiction. Lee Goldberg, creator/head writer for Monk and several other TV mystery series, writes short stories and novels using the Monk character. I hate the TV show Monk, but loved the short story Mr. Monk and The Seventeen Steps in the Dec 2010 Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine. I plan to read some of novels. Lee Goldberg is an excellent writer. The stories and novels support the TV series and the TV series supports the short stories and novel.

If you plan to traditionally publish, published short stories can get you a better agent and open door that may otherwise stay shut.

If you plan to self-publish, free short stories using your characters can be a good way to turn non-fans in customers for your wears. Think on them as test for readers–but don’t think it while you are writing the story.

I play to use this strategy to publish my Old West book series.

Wow, this is a very creepy story, Tom! You should work on it!

Reading this post made me reflect on my own writing routine. I tend to do steps 1-5 in one sitting, pumping out ~2,500-3,500 words in an hour, which is usually all I have for a short story. It’s the editing that definitely takes up the most time. I give it a day before going back and seeing how I can optimize the plot and the finer details.

The number one motivating factor for me to finish writing is my initial interest and excitement of the original idea for the story itself. A wasted story is such a shame, after all.

Impressive Patrick. I could do Steps 1-3 in one sitting, but breaking it into scenes, and especially the research, take me a lot of time.

Scrivener is a great tool for breaking it into workable chances. My second most favorite thing about it!

Agreed Cynthia! Have you seen my review of it? https://thewritepractice.com/scrivener

I had the exact same experience! I need to learn about the word count goals. My favorite feature is the ability to move scenes around and then read it as one long document without actually moving anything.

I am new at it, but look forward to learning more! Great review!

How to write short story? For me he only way is to order it on custom essay writing services reviews pa . To write something you need to be creative person, and it’s not about me 🙁

Love this post! Your first point, write the entire story, is great piece of advice. I say this all this time, “Write the story from beginning to end before doing any re-writing!”

Research being the #5 is great! I don’t find many other writer’s agreeing with on this. They will insist on doing the research upfront. I will see them a year later and ask how the project is going and the answer will be, “I’m still doing research.” I call it The Blackhole of Research and many writers get sucked it. I fell into it once myself when working on a play based on Shakespeare’s Sonnets. I got caught up it wanting to know if Shakespeare wrote the sonnets or not. I never wrote the play. The research thoroughly obscured what I believe would have been an interesting musical. For my series of novel set in the old west, I’m using a time line of events with scant details. I found I need this for the storytelling. But that is it.

I agree with you 100% about Scrivener. It has a bit of learning curve, but is worth it. I started to using it on my last story and now am using it to edit my novel. You can rearrange your scenes any way you want and then read is if it was a continuous document, but without changing the original order of scenes. Valuable in the editing process. It made me happy!

The Only Story They’ll Ever Read. This is excellent advice. It is where many talented writer’s fail.

How I Write Short Stories It takes me about 30 hours to do a draft of a story and then three times that to edit. If I have a real deadline (Not the self imposed kind) I can write it in 8 hours or less and edit it in 12.

I have learned that all I have to do is start writing and a story will emerge. Every time I do a writing prompt, I end up with a story. Every time I write for practice or to take a break from another project, I end up with a story. They are not always good.

Something unusual about me. I hate writing first drafts and love, love, love re-writing them.

How is that “unusual?” I know lots of people who enjoy rewriting over first drafts…? (There’s always someone who believes their “strange” in their habits. You must be from a small town or something lol

Once again, Joe, you cut through all the garbage that’s usually out there about writing to make the process simple. I especially like the idea of doing research after fleshing out the story. I was doing research before starting and I drove myself into a sticky mess. Thank you for pointing out the obvious – even though it wasn’t obvious to me.

I was alone, sitting next to a window on a commercial flight paid for by another who I was convinced cared little for my well being while offering an all expense paid year in a foreign land, no strings attached accept the one holding the sword of Damocles.

One thing I would add, and it’s the best practice I’ve picked up over the years, is to start with the ending. So for number #3, I would suggest come up with both the open and close and fill in the rest.

Thank you so much for this post. It finally got me started on a short story I have been wanting to write for more than a year. Writing down the basic story helped me see the story first.

Thank You… the guide is helpful. Our Lecturer gave an assignment she obliged that we must write a short story in our Journal but i think with your guide i’m going to make it great in the procedure of writing my short story…Thank Alot.

Thank you for this guide! My son is in eighth grade and assigned to write a short story in his honors English class. He’s very analytical and excelling in science and math. He does well in English but this short story has him flummoxed. He keeps saying he doesn’t know how to write a story, which is perplexing because throughout elementary school he wrote long, imaginative stories well above his grade level.

He desperately wants to write this short story but It’s as if his analytical mind has blocked access to his imagination and creativity. What served him well as a child has been squashed by puberty and the inevitable march to maturity. Oh, the sadness.

I just have a feeling though your guide will provide the structure he’s seeking and reopen the pathway to his creativity. It’s still there. We see it all the time. Your guide is organized around the process with time frames to boot! What more could an analytical mind want.

Thank you so much for this post. Sometimes the story gets lost while spending time researching. I always believed the story benefited from a little brewing time before taking on a life outside of my mind. I see now that I’ve been missing out on the valuable steps that can take place once the story is down and the transformation that can take place to form a short story. Your advice is elegant in it’s simplicity.

Great post, but I have one question though to the numer 5.

What am I supposed to research? Research for what? I just don’t understand this.

To me you research for different things. Location and setting of the storiy, maybe it in La Havana, Cuba you should know they speak Spanish, they were in a economy regression so the building are not painted. Maybe one character has some type of illness (PTSD, Lupus, etc.) You would have to know how would that influence how they act, are perceive or look in a story. If he has PTSD he may have flashback’s, or deprecion, ect.

Maybe is a historical fiction you need to know how people acted in that time, what they wore, what was happening, etc.

It give you a better understanding of what is happening. So what you write is believed or make senses.

Thanks for breaking this process down into simple steps! I naturally tend to sit down and spill out the whole story but often don’t know where to go from there. Your post gives me guidelines on how to approach the editing process that I know my work needs.

The best part is your distinction between “the story” and “the short story”. Knowing that makes it so much easier to write that first draft – without agonizing over a sloppy beginning or the overly vague details that require more research.

What a great way to get into your writing with the confidence that you’ll know how to make it better later!

Wow! You make it sound soo easy. Got a load of stories at different stages and feel I should try your steps.

Thanks, Mwai Gichimu http://www.creativeheritage.org

I didn’t realize until fairly recently that short stories were . . . well, so short. I typically write fanfiction that would be consider more of a novella at least 40,000 words. I actually don’t like reading short stories less than 7 chapters and/or 10,000 words. I don’t know I just like more meat on my books than the typical 7 chapter deal.

A Day in the Life of the Samurai.

It was an ordinary day — in the life of the samurai, that is. Samurai and heir to the Hagi residential, Kento Kadesheke, was engaged in a duel with his well recognized, self esteemed master.

“Dodge,” commanded his brain as he curled into a ball and escaped a fatal blow by what marked his people, the sword. Then he leapt up and swished his sword here and there, in defence. Next, he went all-out in a sword batting contest with his master. This gave his time to regain his breath. Now, as many know, the more experienced mostly comes on top, so was the case here. Tired and impatient, Kento tried to disarm his master and opponent. His master expected it and dodged it, not so long before launching a barrage of sword hits, disarming Kento.

Per the rules, disarms end battles, so Kento bowed and fetched his sword. He asked “What did I do wrong, milord,” His master smiled and gently said ” Nothing but thou were a bit impatient,” he added “I can see quick and great improvement,” Now all of this was said in Japanese, but I daren’t mention in imagined sesquipedalophobia

The importance of step six cannot be overstated. I think a second pair of eyes is essential for editing. For example, this non-sentence is from Joe’s promo for his book: http://letswriteashortstory.com/why-short-stories/ “Even more importantly, to practice deliberately have to put your writing skills to the test.” See what I mean?

“Run Isola!”

Isola’s mother yelled over the wind. Isola’s heart was pounding, and she felt as if she might faint. Her brown hair whipped fast, stinging her face. Her mother was rushing her into the safe house. They prepared it a month before when they heard about the Vortex Storm. The name was fitting because there was a big whirl of dark, ravenous clouds. They seemed to eat the whole sky.

“Where is Will and Dad?” Isola asked. “I thought they were coming with us!”

“I am going to get them,” Isola’s mother answered. “Just go and get there before you get hurt!”

She turned and went back to the house while Gloria went toward the safe house.

The wind was so strong, Isola felt as if it would lift her and pick her off her feet. Debris flew everywhere. Other people in her neighborhood were gathering belongings, children, pets, and driving away to the community safe house. Isola was tempted to follow them.

Isola finally made it to the safe house. Its interior was located underground and the door were made of steel. Underground Isola knew there were also steel bars to support the roof the steel ceiling. The lock on the door was located inside. Her father was a construction worker so getting the materials to build it was easy. Isola’s mind flashed back to the time her father stayed up for weeks at a time making sure everything was secure. When she asked if she could help or see what he was working on, he simply told her that it wasn’t time yet. Whatever that meant.

Isola began to open the door, when she heard familiar voices behind her.

“Isola! Watch out!”

Relief comforted her heart for a moment. It was Will’s voice, and he was okay. He’s head popped out around the corner. His brown curly hair waving on his face in the harsh wind. But, that relief was replaced with panic when she saw a big massive tree branch about to fall. On her.

Maybe it wasn’t a good idea to build a safe house by a tree Isola thought. Maybe it wasn’t a good idea to build a safe house, period.

That was all Isola had time to think about before the tree branch fell, and she was forced back by some invisible force. It felt like a hand grabbing her. She stumbled backwards and bumped into something.

Or someone.

“Isola, what are you crazy? You just stand there watching it fall on you, and do absolutely nothing while the branch almost crushes you!”

She turned around to the look to who was speaking to her. And a concerned, upset, face was peering down back at her. Her father. Despite her father scolding at her, she was relieved to see he was okay. Her mother came running in after them.

“Are you okay? What happened?” She turned to Isola’s father. “Mark.”

Mark put a hand on his wife’s arm. “Anna, she’s fine” He started toward the safe house again. “Let’s just hurry and all go inside-” Mark stopped.

“What? What is it?”

Isola followed to where he was staring. The tree branch was on top of the safe house. Blocking the only entrance inside.

Mark shook his head. Swore a few latin words. Anna shot daggers at him covering Will’s ears.

Will looked to me with eyes of confusion. I shrugged.

“Why are we going in here? Why don’t we go in with the other kids and adults?” Will asked.

Will spoke with an accent that his mom said came from his father. When he said ‘adults’ he pronounced it adoolts He pulled his mother’s hands off his ears.

“Will-” His father said will a warning tone in his voice.

“There is a branch on blocking the door. Besides, everybody else is going!” Will argued.

“They don’t want to go to the Community safe house, Will.” Isola told him.

“But, all my friends are there! I wanna go too!” Will whined.

“We have a safe house right here.” Anna said ignoring Will.

Isola made a motion to the safe house which was still stable, but had an impossible entrance. She opened her mouth to say something sarcastic but her mother must of saw the expression on her face because she held up her hand.

“That is enough Isola.” Her mother yelled over the wind. “You have been complaining about this the whole time, and show no appreciation for what your father is doing for you-”

“Dad what are you doing?” Will interrupted.

Gloria and her mom turned around to see what Will was talking about. Mark was pushing the branch-or at least trying to-off the entrance. Anna looked to Will and Isola.

“Come on, don’t just stand there, go help out your father!”

They didn’t need to be asked twice. They all went over and helped Mark push the branch. They pushed, pulled, lifted, but the branch didn’t move more than a couple of inches. But, even by then they were all tired and each second they stayed outside was each second to their death.

Mark reached through one of the openings of the branch and opened the door. “Will or Gloria, one of you can fit in here. Try to go through.”

Will crosses his arms. “No way! I want to go to the Community safe house. Besides you guys could lock us in there and go without us so you can go have fun.” Will stared at his mom and dad with accusing eyes. He had his jaw set in way that showed he wasn’t going to budge.

“Will” His father said angrily.

Isola started toward the entrance. “I’ll go, if you won’t go. Let’s just get in before we get hit by one of those meteorites.” She pointed to the sky. It was darker now blocking out so much sun, the light detectors triggered on the street lights for night time.

Isola started in, going feet first, having a little of a hard time getting in. When she felt her feet touch the ground she called up.

“Okay I’m in!”

There was no response. She looked up to see if anyone was looking in but she saw no one there.

“Mom? Dad?”

She heard something up there that sound like arguing, then panic, and then a moment of silence.

“Isola, are okay down there?” Her mom asked.

“Yeah, what are you guys waiting for?”

“We are going to the Community shelter.”

Isola didn’t know whether to laugh or scream.

“Isola, don’t worry you can wait down there-”

“Wait here? No!” Isola said shaking her head. “Bring me up with you guys.”

“The branch is stuck here, and plus we are running out of time, we are going to see if we can make it-”

Isola heard her father’s voice in the background. She only caught a few words and sentences like: ‘he said’ and ‘not good idea’ and ‘listen’

“I don’t care about what Jem thinks, we are leaving.” Isola heard her mom say.

And the door shut.

Isola heard screams outside. She heard some of Will’s screams, mixed with her mother’s, and other screams of children, frightened animals, and other people. She didn’t want to think about going out there. She knew she couldn’t. So, when the door shut Isola locked the door and went to the furthest corner of the room.

There were blankets, food, water, first aid items, and a radio there. The food and water was packed into four different black book bags. Looking at them made her feel anxious and worried. They’ll be okay. Everything is fine. She thought. When she still didn’t feel any better, she said out loud, “It’s okay. Everything is fine.” Even she knew the words sounded empty and unconvincing.

She wasn’t hungry at the moment. Fatigue washed over Isola so suddenly, that she felt dizzy. Grabbing her blanket from the corner she moved the rest of the items by the door. After, she walked to the corner, sat putting her knees up to her chin, and wrapped the blanket around herself, over her head and ears. She tried to huddle as far as she could into the corner. She wanted to be as far away from the screams as possible. Isola shivered. Though it wasn’t against the cold.

( For more or the rest of the story email me at [email protected] ) 🙂 Tell what you think.

This has been incrediably helpful! Making myself put off researching wasn’t something I would have thought would make a big difference but it really has.

I might be a bit late to the party…my 15 mins.

———- Hugh set the knife against his knee and started sawing through the skin.

As the pain coursed through his nerves, he lost his grip. “Damn bugs,” he hissed as his fingers failed to listen to his brain.

Laying his head against the cold metal of the bathtub, Hugh swore he could feel the lowjack implant in his spinal cord thrumming. A few moments later, the door opened on rusty hinges, allowing the light from the rest of the apartment in.

A falsetto voice spoke from the doorway. “Human, you have sustained an injury to your right knee. Medical personnel have been summoned.”

Hugh turned suddenly, knocking the knife to the floor. “Don’t you dare let those butchers in here!” Sitting up, he started to sob. “I’ve got nothing left for them to take.”

A six foot tall mechanical figure strode calmly into the room. “Human, I’m going to freeze you until the medical personnel arrive.” A green light started blinking in its eye socket. “Do not be alarmed, it is for your own safety.”

Hugh was half way out of the bathtub before the lowjack cut off any control he had over his body.

The android moved to the tub, and gingerly picked Hugh up, moving him through the spacious apartment to a chair by the front door.

“I will be in stasis until they arrive,” the android stated.

Hugh couldn’t detect any difference from a few moments ago. The android stood stone still, the only difference an irregular pattern to the blinking green light.

Waiting a full minute to ensure the thing wasn’t aware, Hugh tried moving his hand. The fingers twitched.

i have a short story , would it be too late to post here , i need some opinion

I opened my eyes to see a dark shadow in my bedroom, it looked like a figure of a man. I had been thinking a lot about my uncle Herbert who had died in the first world war ,l was stunned! Could he be the person on my bed? To stunned to talk to him l recalled speaking to a medium early on in the day about Herbert he came through and said he wondered what his life would have been like if he had lived he died aged 26 . I looked more closely at this figure on my bed then he said come on Pam get up!! We’re on holiday now!!! Pew!!!

Thanks for the great advice Joe Bunting. What I read, helps me know what’s ahead of me to be a writer. I love how you explained about it being hard to finish a story, when you are in the middle of the story. As to rowing a boat to an island. I’ve started stories, got to the middle and didn’t know where to go. Now I know that’s common to happen. I’ll close at this point and get started writing something that I wrote in High School that others loved. Thanks again for inspiring me with what you wrote.

Rick Olmsted

Nice blog here. I think this would be more helpful in my writing career. But if you really need a professional to write a children short story for you, I would recommend a gig I use on Fiverr https://www.fiverr.com/sophiebrown/write-kindle-children-bestseller-book-for-publishing

This is a great intro in short story writing! Usually the only writing I do is assignments and essays. I’ve been toying with the idea of writing a story for a while and this post provided great motivation. So here it is.. my first 15 minute attempt at putting ideas down in words.

The time had come to meet face to face with her biggest rival. She had never met her before but the stories were enough for her to realise the threat that she posed. The environment wasn’t one which forged the women together, to bond. It promoted rivalry. Only the fittest would survive the night and walk away with cash in the hand. Tonight was the same as every other night. It started out with the usual routine. She would meticulously apply her make up to accentuate her pale blue eyes. Her greatest asset, or at least that’s what they told her. The blackness of the eyeliner was unforgiving; no amount of it could cover up the turbulent storm brewing in her blue eyes. Her reflection showed no hint of the emotions she was trying to deny. Her hair was down around her shoulders, glistening from the heat in the room. The air was muggy despite it being a cool night. She looked around the room wondering how her life had brought her to be here in this moment. The walls were as red as bitten lips, that’s what they reminded her of. The other girls were getting impatient that she had taken so much time in the one mirror, which covered the wall above the alcove. There was barely enough room for all four of them to get ready in there. Bags of make up, shoes and dresses, if you could call them that, were scattered at their feet. The buzz of the dryer in the adjoining room reminded her that there was work to be done. Fresh sheets and towels needed to be put out in the rooms before the men arrived. This job gave her a reprieve from being in that suffocating red room. She left the girls to decide on the dresses they would wear tonight.

I was fine, good in fact, realizing that I was stuck in a rut of step 1, Telling my stories. I can do step two, even three. Now I’m lost at step four: I’m writing a short story, not a novel. I’m stopping here; lost my interest, for the moment.