Essay on Independence And Individuality

Students are often asked to write an essay on Independence And Individuality in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Independence And Individuality

Understanding independence.

Independence means making choices for yourself without others telling you what to do. Like a bird flying alone, it’s about being free to live your life. When you pick your clothes or decide on a game to play, that’s you being independent. It’s important because it helps you grow and learn to trust yourself.

What is Individuality?

Individuality is what makes you special and different from others. It’s your own style and thoughts. Imagine everyone wearing the same hat; it would be boring. Your unique ideas and choices, like a rare hat, make you stand out and be you.

The Power of Being You

When you mix independence with individuality, you become strong and confident. You’re like a superhero with your own powers. By choosing your path and being true to yourself, you can achieve great things. Remember, being independent and individual is about celebrating who you are.

250 Words Essay on Independence And Individuality

What is independence.

Independence means being able to do things on your own, without needing help from others. It’s like when you learn to tie your shoes by yourself. You feel proud and capable because you don’t have to wait for someone to do it for you. Being independent is important because it helps you grow and make your own choices.

Individuality is what makes you special and different from everyone else. It’s your unique mix of likes, dislikes, and talents. Imagine if all your friends liked only one kind of ice cream. It would be boring, right? Your individuality is like having your favorite flavor that’s just yours. It adds variety to the world.

Why Independence Is Important

Being independent helps you become stronger. You learn to solve problems, like figuring out a difficult homework question on your own. It also gives you the freedom to choose what you want to do, whether it’s picking a game to play or deciding what to eat for lunch.

Why Individuality Matters

Your individuality lets you express who you are. It could be through the clothes you wear, the music you enjoy, or the way you decorate your room. When you share your own ideas and style, you make the world more interesting.

Bringing Them Together

Independence and individuality go hand in hand. When you’re independent, you can make choices that reflect your individuality. Both are keys to being happy with who you are and living a life that’s true to yourself. Remember, being different is good, and being able to stand on your own makes you strong.

500 Words Essay on Independence And Individuality

Independence means being able to make choices for yourself and do things without needing help from others. It is like when you learn to tie your shoes by yourself or make a sandwich without anyone’s help. For grown-ups, it means they can make bigger decisions, like where to work or live, without asking for permission or waiting for someone else to tell them what to do.

Understanding Individuality

Individuality is what makes you unique from everyone else. It is the special mix of qualities, likes, and dislikes that makes you, well, you! Just like no two snowflakes are the same, no two people are exactly alike. Your individuality is like your personal fingerprint on the world—it shows who you are and what you stand for.

Independence Helps Individuality Grow

When you have independence, you have the freedom to express your individuality. Imagine you want to paint your room. If you can decide the color without anyone else choosing for you, that choice shows a bit of who you are. When people are free to make their own choices, they can show their true colors, like artists painting on a big, blank canvas.

The Balance Between Getting Help and Being Independent

It’s important to remember that even though independence is good, asking for help is okay too. Everyone needs a little help sometimes, and it doesn’t mean you’re not independent. It’s like when you’re learning to ride a bike. At first, you might need training wheels or someone to hold on, but eventually, you learn to ride on your own. Getting help is part of the journey to doing things by yourself.

Why Individuality is Important

Your individuality is important because it is all about what makes you special. It’s like having your own superpower that nobody else has. When you are true to yourself and show your unique qualities, you add something special to the world that wasn’t there before. It’s like adding a new color to a painting that makes it even more beautiful.

How to Respect Others’ Independence and Individuality

Just as you like to make your own choices and be yourself, it’s important to let others do the same. This means not making fun of someone because they are different or telling them they have to like what you like. When you respect others, you let them be who they are, and that’s a great way to make friends and learn new things.

In the end, independence and individuality are like two peas in a pod. They go together perfectly. Independence lets you be the boss of yourself, and individuality is your secret sauce that makes you stand out. Remember, being independent doesn’t mean you never need help, and being individual doesn’t mean you can’t fit in with others. Both are super important for everyone, and respecting them makes the world a happier place for all of us.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Independence Day In Philippines

- Essay on Indian Air Force

- Essay on Ethiopia

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

What does Emerson say about self-reliance?

In Emerson's essay “ Self-Reliance ,” he boldly states society (especially today’s politically correct environment) hurts a person’s growth.

Emerson wrote that self-sufficiency gives a person in society the freedom they need to discover their true self and attain their true independence.

Believing that individualism, personal responsibility , and nonconformity were essential to a thriving society. But to get there, Emerson knew that each individual had to work on themselves to achieve this level of individualism.

Today, we see society's breakdowns daily and wonder how we arrived at this state of society. One can see how the basic concepts of self-trust, self-awareness, and self-acceptance have significantly been ignored.

Who published self-reliance?

Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote the essay, published in 1841 as part of his first volume of collected essays titled "Essays: First Series."

It would go on to be known as Ralph Waldo Emerson's Self Reliance and one of the most well-known pieces of American literature.

The collection was published by James Munroe and Company.

What are the examples of self-reliance?

Examples of self-reliance can be as simple as tying your shoes and as complicated as following your inner voice and not conforming to paths set by society or religion.

Self-reliance can also be seen as getting things done without relying on others, being able to “pull your weight” by paying your bills, and caring for yourself and your family correctly.

Self-reliance involves relying on one's abilities, judgment, and resources to navigate life. Here are more examples of self-reliance seen today:

Entrepreneurship: Starting and running your own business, relying on your skills and determination to succeed.

Financial Independence: Managing your finances responsibly, saving money, and making sound investment decisions to secure your financial future.

Learning and Education: Taking the initiative to educate oneself, whether through formal education, self-directed learning, or acquiring new skills.

Problem-Solving: Tackling challenges independently, finding solutions to problems, and adapting to changing circumstances.

Personal Development: Taking responsibility for personal growth, setting goals, and working towards self-improvement.

Homesteading: Growing your food, raising livestock, or becoming self-sufficient in various aspects of daily life.

DIY Projects: Undertaking do-it-yourself projects, from home repairs to crafting, without relying on external help.

Living Off the Grid: Living independently from public utilities, generating your energy, and sourcing your water.

Decision-Making: Trusting your instincts and making decisions based on your values and beliefs rather than relying solely on external advice.

Crisis Management: Handling emergencies and crises with resilience and resourcefulness without depending on external assistance.

These examples illustrate different facets of self-reliance, emphasizing independence, resourcefulness, and the ability to navigate life autonomously.

What is the purpose of self reliance by Emerson?

In his essay, " Self Reliance, " Emerson's sole purpose is the want for people to avoid conformity. Emerson believed that in order for a man to truly be a man, he was to follow his own conscience and "do his own thing."

Essentially, do what you believe is right instead of blindly following society.

Why is it important to be self reliant?

While getting help from others, including friends and family, can be an essential part of your life and fulfilling. However, help may not always be available, or the assistance you receive may not be what you had hoped for.

It is for this reason that Emerson pushed for self-reliance. If a person were independent, could solve their problems, and fulfill their needs and desires, they would be a more vital member of society.

This can lead to growth in the following areas:

Empowerment: Self-reliance empowers individuals to take control of their lives. It fosters a sense of autonomy and the ability to make decisions independently.

Resilience: Developing self-reliance builds resilience, enabling individuals to bounce back from setbacks and face challenges with greater adaptability.

Personal Growth: Relying on oneself encourages continuous learning and personal growth. It motivates individuals to acquire new skills and knowledge.

Freedom: Self-reliance provides a sense of freedom from external dependencies. It reduces reliance on others for basic needs, decisions, or validation.

Confidence: Achieving goals through one's own efforts boosts confidence and self-esteem. It instills a belief in one's capabilities and strengthens a positive self-image.

Resourcefulness: Being self-reliant encourages resourcefulness. Individuals learn to solve problems creatively, adapt to changing circumstances, and make the most of available resources.

Adaptability: Self-reliant individuals are often more adaptable to change. They can navigate uncertainties with a proactive and positive mindset.

Reduced Stress: Dependence on others can lead to stress and anxiety, especially when waiting for external support. Self-reliance reduces reliance on external factors for emotional well-being.

Personal Responsibility: It promotes a sense of responsibility for one's own life and decisions. Self-reliant individuals are more likely to take ownership of their actions and outcomes.

Goal Achievement: Being self-reliant facilitates the pursuit and achievement of personal and professional goals. It allows individuals to overcome obstacles and stay focused on their objectives.

Overall, self-reliance contributes to personal empowerment, mental resilience, and the ability to lead a fulfilling and purposeful life. While collaboration and support from others are valuable, cultivating a strong sense of self-reliance enhances one's capacity to navigate life's challenges independently.

What did Emerson mean, "Envy is ignorance, imitation is suicide"?

According to Emerson, no kernel of nourishing corn can come to you independently, but every person is given a plot of ground to till.

In other words, Emerson believed that a person's main focus in life is to work on oneself, increasing their maturity and intellect, and overcoming insecurities, which will allow a person to be self-reliant to the point where they no longer envy others but measure themselves against how they were the day before.

When we do become self-reliant, we focus on creating rather than imitating. Being someone we are not is just as damaging to the soul as suicide.

Envy is ignorance: Emerson suggests that feeling envious of others is a form of ignorance. Envy often arises from a lack of understanding or appreciation of one's unique qualities and potential. Instead of being envious, individuals should focus on discovering and developing their talents and strengths.

Imitation is suicide: Emerson extends the idea by stating that imitation, or blindly copying others, is a form of self-destruction. He argues that true individuality and personal growth come from expressing one's unique voice and ideas. In this context, imitation is seen as surrendering one's identity and creativity, leading to a kind of "spiritual death."

What are the transcendental elements in Emerson’s self-reliance?

The five predominant elements of Transcendentalism are nonconformity, self-reliance, free thought, confidence, and the importance of nature.

The Transcendentalism movement emerged in New England between 1820 and 1836. It is essential to differentiate this movement from Transcendental Meditation, a distinct practice.

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Transcendentalism is characterized as "an American literary, political, and philosophical movement of the early nineteenth century, centered around Ralph Waldo Emerson." A central tenet of this movement is the belief that individual purity can be 'corrupted' by society.

Are Emerson's writings referenced in pop culture?

Emerson has made it into popular culture. One such example is in the film Next Stop Wonderland released in 1998. The reference is a quote from Emerson's essay on Self Reliance, "A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds."

This becomes a running theme in the film as a single woman (Hope Davis ), who is quite familiar with Emerson's writings and showcases several men taking her on dates, attempting to impress her by quoting the famous line, only to botch the line and also giving attribution to the wrong person. One gentleman says confidently it was W.C. Fields, while another matches the quote with Cicero. One goes as far as stating it was Karl Marx!

Why does Emerson say about self confidence?

Content is coming very soon.

Self-Reliance: The Complete Essay

Ne te quaesiveris extra."

Man is his own star; and the soul that can Render an honest and a perfect man, Commands all light, all influence, all fate ; Nothing to him falls early or too late. Our acts our angels are, or good or ill, Our fatal shadows that walk by us still." Epilogue to Beaumont and Fletcher's Honest Man's Fortune Cast the bantling on the rocks, Suckle him with the she-wolf's teat; Wintered with the hawk and fox, Power and speed be hands and feet.

Ralph Waldo Emerson left the ministry to pursue a career in writing and public speaking. Emerson became one of America's best known and best-loved 19th-century figures. More About Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson Self Reliance Summary

The essay “Self-Reliance,” written by Ralph Waldo Emerson, is, by far, his most famous piece of work. Emerson, a Transcendentalist, believed focusing on the purity and goodness of individualism and community with nature was vital for a strong society. Transcendentalists despise the corruption and conformity of human society and institutions. Published in 1841, the Self Reliance essay is a deep-dive into self-sufficiency as a virtue.

In the essay "Self-Reliance," Ralph Waldo Emerson advocates for individuals to trust in their own instincts and ideas rather than blindly following the opinions of society and its institutions. He argues that society encourages conformity, stifles individuality, and encourages readers to live authentically and self-sufficient lives.

Emerson also stresses the importance of being self-reliant, relying on one's own abilities and judgment rather than external validation or approval from others. He argues that people must be honest with themselves and seek to understand their own thoughts and feelings rather than blindly following the expectations of others. Through this essay, Emerson emphasizes the value of independence, self-discovery, and personal growth.

What is the Meaning of Self-Reliance?

I read the other day some verses written by an eminent painter which were original and not conventional. The soul always hears an admonition in such lines, let the subject be what it may. The sentiment they instill is of more value than any thought they may contain. To believe your own thought, to think that what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men, — that is genius.

Speak your latent conviction, and it shall be the universal sense; for the inmost in due time becomes the outmost,—— and our first thought is rendered back to us by the trumpets of the Last Judgment. Familiar as the voice of the mind is to each, the highest merit we ascribe to Moses, Plato, and Milton is, that they set at naught books and traditions, and spoke not what men but what they thought. A man should learn to detect and watch that gleam of light that flashes across his mind from within, more than the luster of the firmament of bards and sages. Yet he dismisses without notice his thought because it is his. In every work of genius, we recognize our own rejected thoughts: they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty.

Great works of art have no more affecting lessons for us than this. They teach us to abide by our spontaneous impression with good-humored inflexibility than most when the whole cry of voices is on the other side. Else, tomorrow a stranger will say with masterly good sense precisely what we have thought and felt all the time, and we shall be forced to take with shame our own opinion from another.

There is a time in every man's education when he arrives at the conviction that envy is ignorance; that imitation is suicide; that he must take himself for better, for worse, as his portion; that though the wide universe is full of good, no kernel of nourishing corn can come to him but through his toil bestowed on that plot of ground which is given to him to till. The power which resides in him is new in nature, and none but he knows what that is which he can do, nor does he know until he has tried. Not for nothing one face, one character, one fact, makes much impression on him, and another none. This sculpture in the memory is not without preestablished harmony. The eye was placed where one ray should fall, that it might testify of that particular ray. We but half express ourselves and are ashamed of that divine idea which each of us represents. It may be safely trusted as proportionate and of good issues, so it be faithfully imparted, but God will not have his work made manifest by cowards. A man is relieved and gay when he has put his heart into his work and done his best; but what he has said or done otherwise, shall give him no peace. It is a deliverance that does not deliver. In the attempt his genius deserts him; no muse befriends; no invention, no hope.

Trust Thyself: Every Heart Vibrates To That Iron String.

Accept the place the divine providence has found for you, the society of your contemporaries, and the connection of events. Great men have always done so, and confided themselves childlike to the genius of their age, betraying their perception that the absolutely trustworthy was seated at their heart, working through their hands, predominating in all their being. And we are now men, and must accept in the highest mind the same transcendent destiny; and not minors and invalids in a protected corner, not cowards fleeing before a revolution, but guides, redeemers, and benefactors, obeying the Almighty effort, and advancing on Chaos and the Dark.

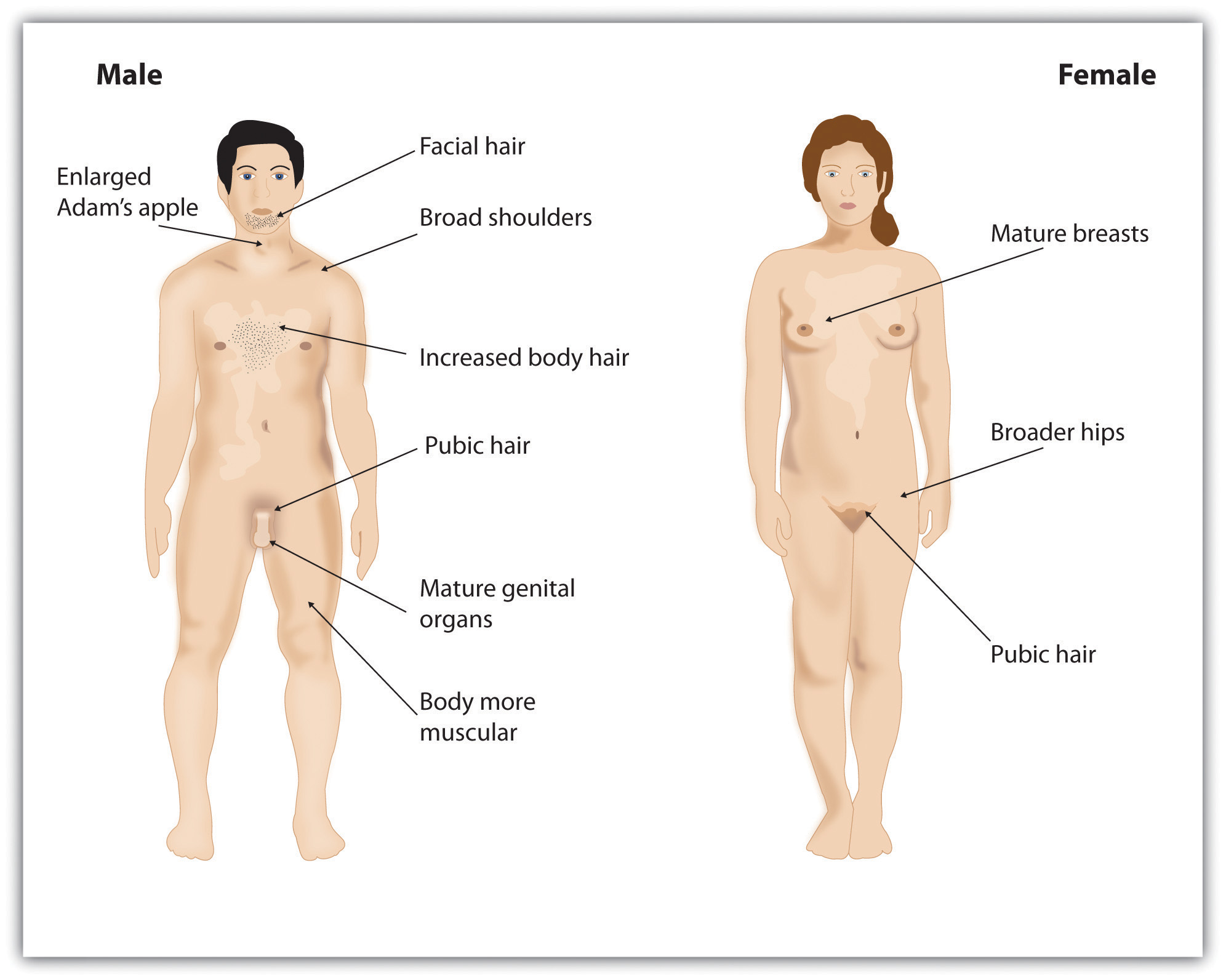

What pretty oracles nature yields to us in this text, in the face and behaviour of children, babes, and even brutes! That divided and rebel mind, that distrust of a sentiment because our arithmetic has computed the strength and means opposed to our purpose, these have not. Their mind being whole, their eye is as yet unconquered, and when we look in their faces, we are disconcerted. Infancy conforms to nobody: all conform to it, so that one babe commonly makes four or five out of the adults who prattle and play to it. So God has armed youth and puberty and manhood no less with its own piquancy and charm, and made it enviable and gracious and its claims not to be put by, if it will stand by itself. Do not think the youth has no force, because he cannot speak to you and me. Hark! in the next room his voice is sufficiently clear and emphatic. It seems he knows how to speak to his contemporaries. Bashful or bold, then, he will know how to make us seniors very unnecessary.

The nonchalance of boys who are sure of a dinner, and would disdain as much as a lord to do or say aught to conciliate one, is the healthy attitude of human nature. A boy is in the parlour what the pit is in the playhouse; independent, irresponsible, looking out from his corner on such people and facts as pass by, he tries and sentences them on their merits, in the swift, summary way of boys, as good, bad, interesting, silly, eloquent, troublesome. He cumbers himself never about consequences, about interests: he gives an independent, genuine verdict. You must court him: he does not court you. But the man is, as it were, clapped into jail by his consciousness. As soon as he has once acted or spoken with eclat, he is a committed person, watched by the sympathy or the hatred of hundreds, whose affections must now enter into his account. There is no Lethe for this. Ah, that he could pass again into his neutrality! Who can thus avoid all pledges, and having observed, observe again from the same unaffected, unbiased, unbribable, unaffrighted innocence, must always be formidable. He would utter opinions on all passing affairs, which being seen to be not private, but necessary, would sink like darts into the ear of men, and put them in fear.

These are the voices which we hear in solitude, but they grow faint and inaudible as we enter into the world. Society everywhere is in conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members. Society is a joint-stock company, in which the members agree, for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater. The virtue in most request is conformity. Self-reliance is its aversion. It loves not realities and creators, but names and customs.

Whoso would be a man must be a nonconformist. He who would gather immortal palms must not be hindered by the name of goodness, but must explore if it be goodness. Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind. Absolve you to yourself, and you shall have the suffrage of the world. I remember an answer which when quite young I was prompted to make to a valued adviser, who was wont to importune me with the dear old doctrines of the church. On my saying, What have I to do with the sacredness of traditions, if I live wholly from within? my friend suggested, — "But these impulses may be from below, not from above." I replied, "They do not seem to me to be such; but if I am the Devil's child, I will live then from the Devil." No law can be sacred to me but that of my nature. Good and bad are but names very readily transferable to that or this; the only right is what is after my constitution, the only wrong what is against it. A man is to carry himself in the presence of all opposition, as if every thing were titular and ephemeral but he. I am ashamed to think how easily we capitulate to badges and names, to large societies and dead institutions. Every decent and well-spoken individual affects and sways me more than is right. I ought to go upright and vital, and speak the rude truth in all ways. If malice and vanity wear the coat of philanthropy, shall that pass? If an angry bigot assumes this bountiful cause of Abolition, and comes to me with his last news from Barbadoes, why should I not say to him, 'Go love thy infant; love thy wood-chopper: be good-natured and modest: have that grace; and never varnish your hard, uncharitable ambition with this incredible tenderness for black folk a thousand miles off. Thy love afar is spite at home.' Rough and graceless would be such greeting, but truth is handsomer than the affectation of love. Your goodness must have some edge to it, — else it is none. The doctrine of hatred must be preached as the counteraction of the doctrine of love when that pules and whines. I shun father and mother and wife and brother, when my genius calls me. The lintels of the door-post I would write on, Whim . It is somewhat better than whim at last I hope, but we cannot spend the day in explanation. Expect me not to show cause why I seek or why I exclude company. Then, again, do not tell me, as a good man did to-day, of my obligation to put all poor men in good situations. Are they my poor? I tell thee, thou foolish philanthropist, that I grudge the dollar, the dime, the cent, I give to such men as do not belong to me and to whom I do not belong. There is a class of persons to whom by all spiritual affinity I am bought and sold; for them I will go to prison, if need be; but your miscellaneous popular charities; the education at college of fools; the building of meeting-houses to the vain end to which many now stand; alms to sots; and the thousandfold Relief Societies; — though I confess with shame I sometimes succumb and give the dollar, it is a wicked dollar which by and by I shall have the manhood to withhold.

Virtues are, in the popular estimate, rather the exception than the rule. There is the man and his virtues. Men do what is called a good action, as some piece of courage or charity, much as they would pay a fine in expiation of daily non-appearance on parade. Their works are done as an apology or extenuation of their living in the world, — as invalids and the insane pay a high board. Their virtues are penances. I do not wish to expiate, but to live. My life is for itself and not for a spectacle. I much prefer that it should be of a lower strain, so it be genuine and equal, than that it should be glittering and unsteady. Wish it to be sound and sweet, and not to need diet and bleeding. The primary evidence I ask that you are a man, and refuse this appeal from the man to his actions. For myself it makes no difference that I know, whether I do or forbear those actions which are reckoned excellent. I cannot consent to pay for a privilege where I have intrinsic right. Few and mean as my gifts may be, I actually am, and do not need for my own assurance or the assurance of my fellows any secondary testimony.

What I must do is all that concerns me, not what the people think.

This rule, equally arduous in actual and in intellectual life, may serve for the whole distinction between greatness and meanness. It is the harder, because you will always find those who think they know what is your duty better than you know it. The easy thing in the world is to live after the world's opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.

The objection to conforming to usages that have become dead to you is, that it scatters your force. It loses your time and blurs the impression of your character. If you maintain a dead church, contribute to a dead Bible-society, vote with a great party either for the government or against it, spread your table like base housekeepers, — under all these screens I have difficulty to detect the precise man you are. And, of course, so much force is withdrawn from your proper life. But do your work, and I shall know you. Do your work, and you shall reinforce yourself. A man must consider what a blindman's-buff is this game of conformity. If I know your sect, I anticipate your argument. I hear a preacher announce for his text and topic the expediency of one of the institutions of his church. Do I not know beforehand that not possibly can he say a new and spontaneous word? With all this ostentation of examining the grounds of the institution, do I not know that he will do no such thing? Do not I know that he is pledged to himself not to look but at one side, — the permitted side, not as a man, but as a parish minister? He is a retained attorney, and these airs of the bench are the emptiest affectation. Well, most men have bound their eyes with one or another handkerchief, and attached themselves to some one of these communities of opinion. This conformity makes them not false in a few particulars, authors of a few lies, but false in all particulars. Their every truth is not quite true. Their two is not the real two, their four not the real four; so that every word they say chagrins us, and we know not where to begin to set them right. Meantime nature is not slow to equip us in the prison-uniform of the party to which we adhere. We come to wear one cut of face and figure, and acquire by degrees the gentlest asinine expression. There is a mortifying experience in particular, which does not fail to wreak itself also in the general history; I mean "the foolish face of praise," the forced smile which we put on in company where we do not feel at ease in answer to conversation which does not interest us. The muscles, not spontaneously moved, but moved by a low usurping wilfulness, grow tight about the outline of the face with the most disagreeable sensation.

For nonconformity the world whips you with its displeasure. And therefore a man must know how to estimate a sour face. The by-standers look askance on him in the public street or in the friend's parlour. If this aversation had its origin in contempt and resistance like his own, he might well go home with a sad countenance; but the sour faces of the multitude, like their sweet faces, have no deep cause, but are put on and off as the wind blows and a newspaper directs. Yet is the discontent of the multitude more formidable than that of the senate and the college. It is easy enough for a firm man who knows the world to brook the rage of the cultivated classes. Their rage is decorous and prudent, for they are timid as being very vulnerable themselves. But when to their feminine rage the indignation of the people is added, when the ignorant and the poor are aroused, when the unintelligent brute force that lies at the bottom of society is made to growl and mow, it needs the habit of magnanimity and religion to treat it godlike as a trifle of no concernment.

The other terror that scares us from self-trust is our consistency; a reverence for our past act or word, because the eyes of others have no other data for computing our orbit than our past acts, and we are loath to disappoint them.

But why should you keep your head over your shoulder? Why drag about this corpse of your memory, lest you contradict somewhat you have stated in this or that public place? Suppose you should contradict yourself; what then? It seems to be a rule of wisdom never to rely on your memory alone, scarcely even in acts of pure memory, but to bring the past for judgment into the thousand-eyed present, and live ever in a new day. In your metaphysics you have denied personality to the Deity: yet when the devout motions of the soul come, yield to them heart and life, though they should clothe God with shape and color. Leave your theory, as Joseph his coat in the hand of the harlot, and flee.

A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines. With consistency a great soul has simply nothing to do. He may as well concern himself with his shadow on the wall. Speak what you think now in hard words, and to-morrow speak what to-morrow thinks in hard words again, though it contradict every thing you said to-day. — 'Ah, so you shall be sure to be misunderstood.' — Is it so bad, then, to be misunderstood? Pythagoras was misunderstood, and Socrates, and Jesus, and Luther, and Copernicus, and Galileo, and Newton, and every pure and wise spirit that ever took flesh. To be great is to be misunderstood.

I suppose no man can violate his nature.

All the sallies of his will are rounded in by the law of his being, as the inequalities of Andes and Himmaleh are insignificant in the curve of the sphere. Nor does it matter how you gauge and try him. A character is like an acrostic or Alexandrian stanza; — read it forward, backward, or across, it still spells the same thing. In this pleasing, contrite wood-life which God allows me, let me record day by day my honest thought without prospect or retrospect, and, I cannot doubt, it will be found symmetrical, though I mean it not, and see it not. My book should smell of pines and resound with the hum of insects. The swallow over my window should interweave that thread or straw he carries in his bill into my web also. We pass for what we are. Character teaches above our wills. Men imagine that they communicate their virtue or vice only by overt actions, and do not see that virtue or vice emit a breath every moment.

There will be an agreement in whatever variety of actions, so they be each honest and natural in their hour. For of one will, the actions will be harmonious, however unlike they seem. These varieties are lost sight of at a little distance, at a little height of thought. One tendency unites them all. The voyage of the best ship is a zigzag line of a hundred tacks. See the line from a sufficient distance, and it straightens itself to the average tendency. Your genuine action will explain itself, and will explain your other genuine actions. Your conformity explains nothing. Act singly, and what you have already done singly will justify you now. Greatness appeals to the future. If I can be firm enough to-day to do right, and scorn eyes, I must have done so much right before as to defend me now. Be it how it will, do right now. Always scorn appearances, and you always may. The force of character is cumulative. All the foregone days of virtue work their health into this. What makes the majesty of the heroes of the senate and the field, which so fills the imagination? The consciousness of a train of great days and victories behind. They shed an united light on the advancing actor. He is attended as by a visible escort of angels. That is it which throws thunder into Chatham's voice, and dignity into Washington's port, and America into Adams's eye. Honor is venerable to us because it is no ephemeris. It is always ancient virtue. We worship it today because it is not of today. We love it and pay it homage, because it is not a trap for our love and homage, but is self-dependent, self-derived, and therefore of an old immaculate pedigree, even if shown in a young person.

I hope in these days we have heard the last of conformity and consistency. Let the words be gazetted and ridiculous henceforward. Instead of the gong for dinner, let us hear a whistle from the Spartan fife. Let us never bow and apologize more. A great man is coming to eat at my house. I do not wish to please him; He should wish to please me, that I wish. I will stand here for humanity, and though I would make it kind, I would make it true. Let us affront and reprimand the smooth mediocrity and squalid contentment of the times, and hurl in the face of custom, and trade, and office, the fact which is the upshot of all history, that there is a great responsible Thinker and Actor working wherever a man works; that a true man belongs to no other time or place, but is the centre of things. Where he is, there is nature. He measures you, and all men, and all events. Ordinarily, every body in society reminds us of somewhat else, or of some other person. Character, reality, reminds you of nothing else; it takes place of the whole creation. The man must be so much, that he must make all circumstances indifferent. Every true man is a cause, a country, and an age; requires infinite spaces and numbers and time fully to accomplish his design; — and posterity seem to follow his steps as a train of clients. A man Caesar is born, and for ages after we have a Roman Empire. Christ is born, and millions of minds so grow and cleave to his genius, that he is confounded with virtue and the possible of man. An institution is the lengthened shadow of one man; as, Monachism, of the Hermit Antony; the Reformation, of Luther; Quakerism, of Fox; Methodism, of Wesley; Abolition, of Clarkson. Scipio, Milton called "the height of Rome"; and all history resolves itself very easily into the biography of a few stout and earnest persons.

Let a man then know his worth, and keep things under his feet. Let him not peep or steal, or skulk up and down with the air of a charity-boy, a bastard, or an interloper, in the world which exists for him. But the man in the street, finding no worth in himself which corresponds to the force which built a tower or sculptured a marble god, feels poor when he looks on these. To him a palace, a statue, or a costly book have an alien and forbidding air, much like a gay equipage, and seem to say like that, 'Who are you, Sir?' Yet they all are his, suitors for his notice, petitioners to his faculties that they will come out and take possession. The picture waits for my verdict: it is not to command me, but I am to settle its claims to praise. That popular fable of the sot who was picked up dead drunk in the street, carried to the duke's house, washed and dressed and laid in the duke's bed, and, on his waking, treated with all obsequious ceremony like the duke, and assured that he had been insane, owes its popularity to the fact, that it symbolizes so well the state of man, who is in the world a sort of sot, but now and then wakes up, exercises his reason, and finds himself a true prince.

Our reading is mendicant and sycophantic. In history, our imagination plays us false. Kingdom and lordship, power and estate, are a gaudier vocabulary than private John and Edward in a small house and common day's work; but the things of life are the same to both; the sum total of both is the same. Why all this deference to Alfred, and Scanderbeg, and Gustavus? Suppose they were virtuous; did they wear out virtue? As great a stake depends on your private act to-day, as followed their public and renowned steps. When private men shall act with original views, the lustre will be transferred from the actions of kings to those of gentlemen.

The world has been instructed by its kings, who have so magnetized the eyes of nations. It has been taught by this colossal symbol the mutual reverence that is due from man to man. The joyful loyalty with which men have everywhere suffered the king, the noble, or the great proprietor to walk among them by a law of his own, make his own scale of men and things, and reverse theirs, pay for benefits not with money but with honor, and represent the law in his person, was the hieroglyphic by which they obscurely signified their consciousness of their own right and comeliness, the right of every man.

The magnetism which all original action exerts is explained when we inquire the reason of self-trust.

Who is the Trustee? What is the aboriginal Self, on which a universal reliance may be grounded? What is the nature and power of that science-baffling star, without parallax, without calculable elements, which shoots a ray of beauty even into trivial and impure actions, if the least mark of independence appear? The inquiry leads us to that source, at once the essence of genius, of virtue, and of life, which we call Spontaneity or Instinct. We denote this primary wisdom as Intuition, whilst all later teachings are tuitions. In that deep force, the last fact behind which analysis cannot go, all things find their common origin. For, the sense of being which in calm hours rises, we know not how, in the soul, is not diverse from things, from space, from light, from time, from man, but one with them, and proceeds obviously from the same source whence their life and being also proceed. We first share the life by which things exist, and afterwards see them as appearances in nature, and forget that we have shared their cause. Here is the fountain of action and of thought. Here are the lungs of that inspiration which giveth man wisdom, and which cannot be denied without impiety and atheism. We lie in the lap of immense intelligence, which makes us receivers of its truth and organs of its activity. When we discern justice, when we discern truth, we do nothing of ourselves, but allow a passage to its beams. If we ask whence this comes, if we seek to pry into the soul that causes, all philosophy is at fault. Its presence or its absence is all we can affirm. Every man discriminates between the voluntary acts of his mind, and his involuntary perceptions, and knows that to his involuntary perceptions a perfect faith is due. He may err in the expression of them, but he knows that these things are so, like day and night, not to be disputed. My wilful actions and acquisitions are but roving; — the idlest reverie, the faintest native emotion, command my curiosity and respect. Thoughtless people contradict as readily the statement of perceptions as of opinions, or rather much more readily; for, they do not distinguish between perception and notion. They fancy that I choose to see this or that thing. But perception is not whimsical, but fatal. If I see a trait, my children will see it after me, and in course of time, all mankind, — although it may chance that no one has seen it before me. For my perception of it is as much a fact as the sun.

The relations of the soul to the divine spirit are so pure, that it is profane to seek to interpose helps. It must be that when God speaketh he should communicate, not one thing, but all things; should fill the world with his voice; should scatter forth light, nature, time, souls, from the centre of the present thought; and new date and new create the whole. Whenever a mind is simple, and receives a divine wisdom, old things pass away, — means, teachers, texts, temples fall; it lives now, and absorbs past and future into the present hour. All things are made sacred by relation to it, — one as much as another. All things are dissolved to their centre by their cause, and, in the universal miracle, petty and particular miracles disappear. If, therefore, a man claims to know and speak of God, and carries you backward to the phraseology of some old mouldered nation in another country, in another world, believe him not. Is the acorn better than the oak which is its fulness and completion? Is the parent better than the child into whom he has cast his ripened being? Whence, then, this worship of the past? The centuries are conspirators against the sanity and authority of the soul. Time and space are but physiological colors which the eye makes, but the soul is light; where it is, is day; where it was, is night; and history is an impertinence and an injury, if it be anything more than a cheerful apologue or parable of my being and becoming.

Man is timid and apologetic; he is no longer upright; 'I think,' 'I am,' that he dares not say, but quotes some saint or sage. He is ashamed before the blade of grass or the blowing rose. These roses under my window make no reference to former roses or to better ones; they are for what they are; they exist with God today. There is no time to them. There is simply the rose; it is perfect in every moment of its existence. Before a leaf bud has burst, its whole life acts; in the full-blown flower there is no more; in the leafless root there is no less. Its nature is satisfied, and it satisfies nature, in all moments alike. But man postpones or remembers; he does not live in the present, but with reverted eye laments the past, or, heedless of the riches that surround him, stands on tiptoe to foresee the future. He cannot be happy and strong until he too lives with nature in the present, above time.

This should be plain enough. Yet see what strong intellects dare not yet hear God himself, unless he speak the phraseology of I know not what David, or Jeremiah, or Paul. We shall not always set so great a price on a few texts, on a few lives. We are like children who repeat by rote the sentences of grandames and tutors, and, as they grow older, of the men of talents and character they chance to see, — painfully recollecting the exact words they spoke; afterwards, when they come into the point of view which those had who uttered these sayings, they understand them, and are willing to let the words go; for, at any time, they can use words as good when occasion comes. If we live truly, we shall see truly. It is as easy for the strong man to be strong, as it is for the weak to be weak. When we have new perception, we shall gladly disburden the memory of its hoarded treasures as old rubbish. When a man lives with God, his voice shall be as sweet as the murmur of the brook and the rustle of the corn.

And now at last the highest truth on this subject remains unsaid; probably cannot be said; for all that we say is the far-off remembering of the intuition. That thought, by what I can now nearest approach to say it, is this. When good is near you, when you have life in yourself, it is not by any known or accustomed way; you shall not discern the foot-prints of any other; not see the face of man; and you shall not hear any name;—— the way, the thought, the good, shall be wholly strange and new. It shall exclude example and experience. You take the way from man, not to man. All persons that ever existed are its forgotten ministers. Fear and hope are alike beneath it. There is somewhat low even in hope. In the hour of vision, there is nothing that can be called gratitude, nor properly joy. The soul raised over passion beholds identity and eternal causation, perceives the self-existence of Truth and Right, and calms itself with knowing that all things go well. Vast spaces of nature, the Atlantic Ocean, the South Sea, — long intervals of time, years, centuries, — are of no account. This which I think and feel underlay every former state of life and circumstances, as it does underlie my present, and what is called life, and what is called death.

Life only avails, not the having lived.

Power ceases in the instant of repose; it resides in the moment of transition from a past to a new state, in the shooting of the gulf, in the darting to an aim. This one fact the world hates is that the soul becomes ; for that forever degrades the past, turns all riches to poverty, all reputation to a shame, confounds the saint with the rogue, shoves Jesus and Judas equally aside. Why, then, do we prate of self-reliance? Inasmuch as the soul is present, there will be power, not confidence but an agent. To talk of reliance is a poor external way of speaking. Speak rather of that which relies, because it works and is. Who has more obedience than I masters me, though he should not raise his finger. Round him I must revolve by the gravitation of spirits. We fancy it rhetoric, when we speak of eminent virtue. We do not yet see that virtue is Height, and that a man or a company of men, plastic and permeable to principles, by the law of nature must overpower and ride all cities, nations, kings, rich men, poets, who are not.

This is the ultimate fact which we so quickly reach on this, as on every topic, the resolution of all into the ever-blessed ONE. Self-existence is the attribute of the Supreme Cause, and it constitutes the measure of good by the degree in which it enters into all lower forms. All things real are so by so much virtue as they contain. Commerce, husbandry, hunting, whaling, war, eloquence , personal weight, are somewhat, and engage my respect as examples of its presence and impure action. I see the same law working in nature for conservation and growth. Power is in nature the essential measure of right. Nature suffers nothing to remain in her kingdoms which cannot help itself. The genesis and maturation of a planet, its poise and orbit, the bended tree recovering itself from the strong wind, the vital resources of every animal and vegetable, are demonstrations of the self-sufficing, and therefore self-relying soul.

Thus all concentrates: let us not rove; let us sit at home with the cause. Let us stun and astonish the intruding rabble of men and books and institutions, by a simple declaration of the divine fact. Bid the invaders take the shoes from off their feet, for God is here within. Let our simplicity judge them, and our docility to our own law demonstrate the poverty of nature and fortune beside our native riches.

But now we are a mob. Man does not stand in awe of man, nor is his genius admonished to stay at home, to put itself in communication with the internal ocean, but it goes abroad to beg a cup of water of the urns of other men. We must go alone. I like the silent church before the service begins, better than any preaching. How far off, how cool, how chaste the persons look, begirt each one with a precinct or sanctuary! So let us always sit. Why should we assume the faults of our friend, or wife, or father, or child, because they sit around our hearth, or are said to have the same blood? All men have my blood, and I have all men's. Not for that will I adopt their petulance or folly, even to the extent of being ashamed of it. But your isolation must not be mechanical, but spiritual, that is, must be elevation. At times the whole world seems to be in conspiracy to importune you with emphatic trifles. Friend, client, child, sickness, fear, want, charity, all knock at once at thy closet door, and say, — 'Come out unto us.' But keep thy state; come not into their confusion. The power men possess to annoy me, I give them by a weak curiosity. No man can come near me but through my act. "What we love that we have, but by desire we bereave ourselves of the love."

If we cannot at once rise to the sanctities of obedience and faith, let us at least resist our temptations; let us enter into the state of war, and wake Thor and Woden, courage and constancy, in our Saxon breasts. This is to be done in our smooth times by speaking the truth. Check this lying hospitality and lying affection. Live no longer to the expectation of these deceived and deceiving people with whom we converse. Say to them, O father, O mother, O wife, O brother, O friend, I have lived with you after appearances hitherto. Henceforward I am the truth's. Be it known unto you that henceforward I obey no law less than the eternal law. I will have no covenants but proximities. To nourish my parents, to support my family I shall endeavour, to be the chaste husband of one wife, — but these relations I must fill after a new and unprecedented way. I appeal from your customs that I must be myself. I cannot break myself any longer for you, or you. If you can love me for what I am, we shall be the happier. If you cannot, I will still seek to deserve that you should. I will not hide my tastes or aversions. I will so trust that what is deep is holy, that I will do strongly before the sun and moon whatever inly rejoices me, and the heart appoints. If you are noble, I will love you; I will not hurt you and myself by hypocritical attentions if you are not. If you are true, but not in the same truth with me, cleave to your companions; I will seek my own. I do this not selfishly, but humbly and truly. It is alike your interest, and mine, and all men's, however long we have dwelt in lies, to live in truth. Does this sound harsh today? You will soon love what is dictated by your nature as well as mine, and, if we follow the truth, it will bring us out safe at last. — But so you may give these friends pain. Yes, but I cannot sell my liberty and my power, to save their sensibility. Besides, all persons have their moments of reason, when they look out into the region of absolute truth; then will they justify me, and do the same thing.

The populace think that your rejection of popular standards is a rejection of all standard, and mere antinomianism; and the bold sensualist will use the name of philosophy to gild his crimes. But the law of consciousness abides. There are two confessionals, in one or the other of which we must be shriven. You may fulfil your round of duties by clearing yourself in the direct , or in the reflex way. Consider whether you have satisfied your relations to father, mother, cousin, neighbour, town, cat, and dog; whether any of these can upbraid you. But I may also neglect this reflex standard, and absolve me to myself. I have my own stern claims and perfect circle. It denies the name of duty to many offices that are called duties. But if I can discharge its debts, it enables me to dispense with the popular code. If anyone imagines that this law is lax, let him keep its commandment one day.

And truly it demands something godlike in him who has cast off the common motives of humanity, and has ventured to trust himself for a taskmaster. High be his heart, faithful his will, clear his sight, that he may in good earnest be doctrine, society, law, to himself, that a simple purpose may be to him as strong as iron necessity is to others!

If any man consider the present aspects of what is called by distinction society , he will see the need of these ethics. The sinew and heart of man seem to be drawn out, and we are become timorous, desponding whimperers. We are afraid of truth, afraid of fortune, afraid of death, and afraid of each other. Our age yields no great and perfect persons. We want men and women who shall renovate life and our social state, but we see that most natures are insolvent, cannot satisfy their own wants, have an ambition out of all proportion to their practical force, and do lean and beg day and night continually. Our housekeeping is mendicant, our arts, our occupations, our marriages, our religion, we have not chosen, but society has chosen for us. We are parlour soldiers. We shun the rugged battle of fate , where strength is born.

If our young men miscarry in their first enterprises, they lose all heart.

Men say he is ruined if the young merchant fails . If the finest genius studies at one of our colleges, and is not installed in an office within one year afterwards in the cities or suburbs of Boston or New York, it seems to his friends and to himself that he is right in being disheartened, and in complaining the rest of his life. A sturdy lad from New Hampshire or Vermont, who in turn tries all the professions, who teams it , farms it , peddles , keeps a school, preaches, edits a newspaper, goes to Congress, buys a township, and so forth, in successive years, and always, like a cat, falls on his feet, is worth a hundred of these city dolls. He walks abreast with his days, and feels no shame in not 'studying a profession,' for he does not postpone his life, but lives already. He has not one chance, but a hundred chances. Let a Stoic open the resources of man, and tell men they are not leaning willows, but can and must detach themselves; that with the exercise of self-trust, new powers shall appear; that a man is the word made flesh, born to shed healing to the nations, that he should be ashamed of our compassion, and that the moment he acts from himself, tossing the laws, the books, idolatries, and customs out of the window, we pity him no more, but thank and revere him, — and that teacher shall restore the life of man to splendor, and make his name dear to all history.

It is easy to see that a greater self-reliance must work a revolution in all the offices and relations of men; in their religion; education; and in their pursuits; their modes of living; their association; in their property; in their speculative views.

1. In what prayers do men allow themselves! That which they call a holy office is not so much as brave and manly. Prayer looks abroad and asks for some foreign addition to come through some foreign virtue, and loses itself in endless mazes of natural and supernatural, and mediatorial and miraculous. It is prayer that craves a particular commodity, — anything less than all good, — is vicious. Prayer is the contemplation of the facts of life from the highest point of view. It is the soliloquy of a beholding and jubilant soul. It is the spirit of God pronouncing his works good. But prayer as a means to effect a private end is meanness and theft. It supposes dualism and not unity in nature and consciousness. As soon as the man is at one with God, he will not beg. He will then see prayer in all action. The prayer of the farmer kneeling in his field to weed it, the prayer of the rower kneeling with the stroke of his oar, are true prayers heard throughout nature, though for cheap ends. Caratach, in Fletcher's Bonduca, when admonished to inquire the mind of the god Audate, replies, —

"His hidden meaning lies in our endeavours; Our valors are our best gods."

Another sort of false prayers are our regrets. Discontent is the want of self-reliance: it is infirmity of will. Regret calamities, if you can thereby help the sufferer; if not, attend your own work, and already the evil begins to be repaired. Our sympathy is just as base. We come to them who weep foolishly, and sit down and cry for company, instead of imparting to them truth and health in rough electric shocks, putting them once more in communication with their own reason. The secret of fortune is joy in our hands. Welcome evermore to gods and men is the self-helping man. For him all doors are flung wide: him all tongues greet, all honors crown, all eyes follow with desire. Our love goes out to him and embraces him, because he did not need it. We solicitously and apologetically caress and celebrate him, because he held on his way and scorned our disapprobation. The gods love him because men hated him. "To the persevering mortal," said Zoroaster, "the blessed Immortals are swift."

As men's prayers are a disease of the will, so are their creeds a disease of the intellect . They say with those foolish Israelites, 'Let not God speak to us, lest we die. Speak thou, speak any man with us, and we will obey.' Everywhere I am hindered of meeting God in my brother, because he has shut his own temple doors, and recites fables merely of his brother's, or his brother's brother's God. Every new mind is a new classification. If it prove a mind of uncommon activity and power, a Locke, a Lavoisier, a Hutton, a Bentham, a Fourier, it imposes its classification on other men, and lo! a new system. In proportion to the depth of the thought, and so to the number of the objects it touches and brings within reach of the pupil, is his complacency. But chiefly is this apparent in creeds and churches, which are also classifications of some powerful mind acting on the elemental thought of duty, and man's relation to the Highest. Such as Calvinism, Quakerism, Swedenborgism. The pupil takes the same delight in subordinating everything to the new terminology, as a girl who has just learned botany in seeing a new earth and new seasons thereby. It will happen for a time, that the pupil will find his intellectual power has grown by the study of his master's mind. But in all unbalanced minds, the classification is idolized, passes for the end, and not for a speedily exhaustible means, so that the walls of the system blend to their eye in the remote horizon with the walls of the universe; the luminaries of heaven seem to them hung on the arch their master built. They cannot imagine how you aliens have any right to see, — how you can see; 'It must be somehow that you stole the light from us.' They do not yet perceive, that light, unsystematic, indomitable, will break into any cabin, even into theirs. Let them chirp awhile and call it their own. If they are honest and do well, presently their neat new pinfold will be too strait and low, will crack, will lean, will rot and vanish, and the immortal light, all young and joyful, million-orbed, million-colored, will beam over the universe as on the first morning.

2. It is for want of self-culture that the superstition of Travelling, whose idols are Italy, England, Egypt, retains its fascination for all educated Americans. They who made England, Italy, or Greece venerable in the imagination did so by sticking fast where they were, like an axis of the earth. In manly hours, we feel that duty is our place. The soul is no traveller; the wise man stays at home, and when his necessities, his duties, on any occasion call him from his house, or into foreign lands, he is at home still, and shall make men sensible by the expression of his countenance, that he goes the missionary of wisdom and virtue, and visits cities and men like a sovereign, and not like an interloper or a valet.

I have no churlish objection to the circumnavigation of the globe, for the purposes of art, of study, and benevolence, so that the man is first domesticated, or does not go abroad with the hope of finding somewhat greater than he knows. He who travels to be amused, or to get somewhat which he does not carry, travels away from himself, and grows old even in youth among old things. In Thebes, in Palmyra, his will and mind have become old and dilapidated as they. He carries ruins to ruins.

Travelling is a fool's paradise. Our first journeys discover to us the indifference of places. At home I dream that at Naples, at Rome, I can be intoxicated with beauty, and lose my sadness. I pack my trunk, embrace my friends, embark on the sea, and at last wake up in Naples, and there beside me is the stern fact, the sad self, unrelenting, identical, that I fled from. The Vatican, and the palaces I seek. But I am not intoxicated though I affect to be intoxicated with sights and suggestions. My giant goes with me wherever I go.

3. But the rage of travelling is a symptom of a deeper unsoundness affecting the whole intellectual action. The intellect is vagabond, and our system of education fosters restlessness. Our minds travel when our bodies are forced to stay at home. We imitate, and what is imitation but the travelling of the mind? Our houses are built with foreign taste; Shelves are garnished with foreign ornaments, but our opinions, our tastes, our faculties, lean, and follow the Past and the Distant. The soul created the arts wherever they have flourished. It was in his own mind that the artist sought his model. It was an application of his own thought to the thing to be done and the conditions to be observed. And why need we copy the Doric or the Gothic model? Beauty, convenience, grandeur of thought, and quaint expression are as near to us as to any, and if the American artist will study with hope and love the precise thing to be done by him, considering the climate, the soil, the length of the day, the wants of the people, the habit and form of the government, he will create a house in which all these will find themselves fitted, and taste and sentiment will be satisfied also.

Insist on yourself; never imitate. Your own gift you can present every moment with the cumulative force of a whole life's cultivation, but of the adopted talent of another, you have only an extemporaneous, half possession. That which each can do best, none but his Maker can teach him. No man yet knows what it is, nor can, till that person has exhibited it. Where is the master who could have taught Shakespeare? Where is the master who could have instructed Franklin, or Washington, or Bacon, or Newton? Every great man is a unique. The Scipionism of Scipio is precisely that part he could not borrow. Shakespeare will never be made by the study of Shakespeare. Do that which is assigned you, and you cannot hope too much or dare too much. There is at this moment for you an utterance brave and grand as that of the colossal chisel of Phidias, or trowel of the Egyptians, or the pen of Moses, or Dante, but different from all these. Not possibly will the soul all rich, all eloquent, with thousand-cloven tongue, deign to repeat itself; but if you can hear what these patriarchs say, surely you can reply to them in the same pitch of voice; for the ear and the tongue are two organs of one nature. Abide in the simple and noble regions of thy life, obey thy heart, and thou shalt reproduce the Foreworld again.

4. As our Religion, our Education, our Art look abroad, so does our spirit of society. All men plume themselves on the improvement of society, and no man improves.

Society never advances. It recedes as fast on one side as it gains on the other and undergoes continual changes; it is barbarous, civilized, christianized, rich and it is scientific, but this change is not amelioration. For everything that is given, something is taken. Society acquires new arts, and loses old instincts. What a contrast between the well-clad, reading, writing, thinking American, with a watch, a pencil, and a bill of exchange in his pocket, and the naked New Zealander, whose property is a club, a spear, a mat, and an undivided twentieth of a shed to sleep under! But compare the health of the two men, and you shall see that the white man has lost his aboriginal strength. If the traveller tell us truly, strike the savage with a broad axe, and in a day or two, the flesh shall unite and heal as if you struck the blow into soft pitch, and the same blow shall send the white to his grave.

The civilized man has built a coach, but has lost the use of his feet. He is supported on crutches, but lacks so much support of muscle. He has a fine Geneva watch, but he fails of the skill to tell the hour by the sun. A Greenwich nautical almanac he has, and so being sure of the information when he wants it, the man in the street does not know a star in the sky. The solstice he does not observe, the equinox he knows as little, and the whole bright calendar of the year are without a dial in his mind. His note-books impair his memory; his libraries overload his wit; the insurance office increases the number of accidents; and it may be a question whether machinery does not encumber; whether we have not lost by refinement some energy, by a Christianity entrenched in establishments and forms, some vigor of wild virtue. For every Stoic was a Stoic, but in Christendom, where is the Christian?

There is no more deviation in the moral standard than in the standard of height or bulk. No greater men are now than ever were. A singular equality may be observed between the great men of the first and of the last ages; nor can all the science, art, religion, and philosophy of the nineteenth century avail to educate greater men than Plutarch's heroes, three or four and twenty centuries ago. Not in time is the race progressive. Phocion, Socrates, Anaxagoras, Diogenes, are great men, but they leave no class. He who is really of their class will not be called by their name, but will be his own man, and, in his turn, the founder of a sect. The arts and inventions of each period are only its costume, and do not invigorate men. The harm of the improved machinery may compensate its good. Hudson and Behring accomplished so much in their fishing boats, as to astonish Parry and Franklin, whose equipment exhausted the resources of science and art. Galileo, with an opera-glass, discovered a more splendid series of celestial phenomena than anyone since. Columbus found the New World in an undecked boat. It is curious to see the periodical disuse and perishing of means and machinery, which were introduced with loud laudation a few years or centuries before. The great genius returns to essential man. We reckoned the improvements of the art of war among the triumphs of science, and yet Napoleon conquered Europe by the bivouac, which consisted of falling back on naked valor and disencumbering it of all aids. The Emperor held it impossible to make a perfect army, says Las Casas, "without abolishing our arms, magazines, commissaries, and carriages, until, in imitation of the Roman custom, the soldier should receive his supply of corn, grind it in his hand-mill, and bake his bread himself."

Society is a wave. The wave moves onward, but the water of which it is composed does not. The same particle does not rise from the valley to the ridge. Its unity is only phenomenal. The persons who make up a nation today, next year die, and their experience with them.

And so the reliance on Property, including the reliance on governments which protect it, is the want of self-reliance. Men have looked away from themselves and at things so long, that they have come to esteem the religious, learned, and civil institutions as guards of property, and they deprecate assaults on these, because they feel them to be assaults on property. They measure their esteem of each other by what each has, and not by what each is. But a cultivated man becomes ashamed of his property, out of new respect for his nature. Especially he hates what he has, if he see that it is accidental, — came to him by inheritance, or gift, or crime; then he feels that it is not having; it does not belong to him, has no root in him, and merely lies there, because no revolution or no robber takes it away. But that which a man is does always by necessity acquire, and what the man acquires is living property, which does not wait the beck of rulers, or mobs, or revolutions, or fire, or storm, or bankruptcies, but perpetually renews itself wherever the man breathes. "Thy lot or portion of life," said the Caliph Ali, "is seeking after thee; therefore, be at rest from seeking after it." Our dependence on these foreign goods leads us to our slavish respect for numbers. The political parties meet in numerous conventions; the greater the concourse, and with each new uproar of announcement, The delegation from Essex! The Democrats from New Hampshire! The Whigs of Maine! the young patriot feels himself stronger than before by a new thousand of eyes and arms. In like manner the reformers summon conventions, and vote and resolve in multitude. Not so, O friends! will the God deign to enter and inhabit you, but by a method precisely the reverse. It is only as a man puts off all foreign support, and stands alone, that I see him to be strong and to prevail. He is weaker by every recruit to his banner. Is not a man better than a town? Ask nothing of men, and in the endless mutation, thou only firm column must presently appear the upholder of all that surrounds thee. He who knows that power is inborn, that he is weak because he has looked for good out of him and elsewhere, and so perceiving, throws himself unhesitatingly on his thought, instantly rights himself, stands in the erect position, commands his limbs, works miracles; just as a man who stands on his feet is stronger than a man who stands on his head.

So use all that is called Fortune. Most men gamble with her, and gain all, and lose all, as her wheel rolls. But do thou leave as unlawful these winnings, and deal with Cause and Effect, the chancellors of God. In the Will work and acquire, and thou hast chained the wheel of Chance, and shalt sit hereafter out of fear from her rotations. A political victory, a rise of rents, the recovery of your sick, or the return of your absent friend, or some other favorable event, raises your spirits, and you think good days are preparing for you. Do not believe it. Nothing can bring you peace but yourself. Nothing can bring you peace but the triumph of principles.

Which quotation from "Self-reliance" best summarizes Emerson’s view on belief in oneself?

One of the most famous quotes from Ralph Waldo Emerson's "Self-Reliance" that summarizes his view on belief in oneself is:

"Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string."

What does Emerson argue should be the basis of human actions in the second paragraph of “self-reliance”?

In the second paragraph of "Self-Reliance," Emerson argues that individual conscience, or a person's inner voice, should be the basis of human actions. He writes, "Whoso would be a man must be a nonconformist." He believes that society tends to impose conformity and discourage people from following their own inner truth and intuition. Emerson encourages individuals to trust themselves and to act according to their own beliefs, instead of being influenced by the opinions of others. He argues that this is the way to live a truly authentic and fulfilling life.

Which statement best describes Emerson’s opinion of communities, according to the first paragraph of society and solitude?

According to the first paragraph of Ralph Waldo Emerson's " Society and Solitude, " Emerson has a mixed opinion of communities. He recognizes the importance of social interaction and the benefits of being part of a community but also recognizes the limitations that come with it.

He writes, "Society everywhere is in a conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members." He argues that society can be limiting and restrictive, and can cause individuals to conform to norms and values that may not align with their own beliefs and desires. He believes that it is important for individuals to strike a balance between the benefits of social interaction and the need for solitude and self-discovery.

Which best describes Emerson’s central message to his contemporaries in "self-reliance"?

Ralph Waldo Emerson's central message to his contemporaries in "Self-Reliance" is to encourage individuals to trust in their own beliefs and instincts, and to break free from societal norms and expectations. He argues that individuals should have the courage to think for themselves and to live according to their own individual truth, rather than being influenced by the opinions of others. Through this message, he aims to empower people to live authentic and fulfilling lives, rather than living in conformity and compromise.

Yet, it is critical that we first possess the ability to conceive our own thoughts. Prior to venturing into the world, we must be intimately acquainted with our own selves and our individual minds. This sentiment echoes the concise maxim inscribed at the ancient Greek site of the Delphic Oracle: 'Know Thyself.'

In essence, Emerson's central message in "Self-Reliance" is to promote self-reliance and individualism as the key to a meaningful and purposeful life.

Understanding Emerson: "The American scholar" and his struggle for self-reliance.

Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09982-0

Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Other works from ralph waldo emerson for book clubs, the over-soul.

There is a difference between one and another hour of life, in their authority and subsequent effect. Our faith comes in moments; our vice is habitual.

The American Scholar

An Oration delivered before the Phi Beta Kappa Society, at Cambridge, August 31, 1837

Essays First Series

Essays: First Series First published in 1841 as Essays. After Essays: Second Series was published in 1844, Emerson corrected this volume and republished it in 1847 as Essays: First Series.

Emerson's Essays

Research the collective works of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Read More Essay

Self-Reliance

Emerson's most famous work that can truly change your life. Check it out

Early Emerson Poems

America's best known and best-loved poems. More Poems

Winslow Homer, Woodcutter, 1891

Alex Zakaras on The Roots of American Individualism

By Alex Zakaras November 04, 2022

Individualism is a defining feature of American public life. Its influence is pervasive today, with liberals and conservatives alike promising to expand personal freedom and defend individual rights against unwanted intrusion, be it from big government, big corporations, or intolerant majorities. The Roots of American Individualism traces the origins of individualist ideas to the turbulent political controversies of the Jacksonian era (1820–1850) and explores their enduring influence on American politics and culture.

What are political myths, and what led you to focus on them in this book?

AZ: Broadly speaking, political myths are widely accepted stories that help us make sense of political events and experiences. In the book, I focus on a certain kind of political myth, which I call foundational myth. A foundational myth paints a glorified portrait of the nation and its people. It tells a story of national origins that explains who its people are and who they are meant to be. It often does this by contrasting them to some threatening other—some antagonist or rival, or some source of pollution or decay.

For example, one of the foundational myths I explore in the book is the myth of the self-made man. This longstanding myth tells us a story about what America is and who Americans are. America, it says, is a land of limitless opportunity founded by those fleeing hierarchy and oppression in the Old World. For over two hundred years, this myth has taught us that our country is uniquely fluid and classless and that individuals invariably get ahead through hard work, ingenuity, and perseverance. It tells us, moreover, that Americans are a bold and enterprising people with the resolve and self-discipline to chart their own course in the world.

I chose to focus on foundational myths because they are such powerful forces in our politics and culture—and because they haven’t gotten enough attention from historians and political theorists. Like religious myths, foundational myths help us find meaning in the world and a sense of shared identity and purpose. In doing so, they shape our political beliefs, making us receptive to certain political viewpoints and instinctively resistant to others. So if we want to understand why Americans believe what they do about politics, these myths are a good place to start.

Why do you describe the Jacksonian Era as the “crucible” of American political myths?