77 Unique Metamorphosis Essay Topics [with Examples]

When you have to write The Metamorphosis essay, you should find or come up with a solid idea. Our writers developed a number of topics that can help you with your task. In this article, you’ll read the ideas for the paper. Besides, if you click on the links, you’ll open The Metamorphosis samples that you can check for free.

See The Metamorphosis essay topics and examples here:

- Consider the transformation that happened with Grete Samsa throughout the story. How does Gregor’s sister change after Gregor’s transformation ? Explain how her work and house duties turned her into a more mature and confident person. How did it affect the ending of The Metamorphosis ?

- Speculate on the symbolic meaning of food. How does food reflect the relationship between Gregor and his family? Their financial situation? Mention how Gregor gave up eating by the end of the novella, just as he eventually gave up living. What impact did food (especially an apple) have on Gregor’s life and death?

- Examine the character of Mrs. Samsa. Why doesn’t the reader learn her name? What is her role in the story? Elaborate on her relationships with other family members. Why did she want to visit Gregor after his transformation? Was she able to?

- Comment on the tone of the novella. How does Kafka’s style impact the tone of The Metamorphosis ? How does the narrator’s tone contradict the events from the start? Explore the novella’s language and themes to analyze its tone, provide examples from the text.

- Talk about different translations of The Metamorphosis . What are the differences in various translations of the novella? Examplify a few essential ones. Why is translating Kafka’s writing quite tricky?

- Analyze the conflict between the mind and the body. How does Gregor suffer from the conflict after the transformation ? In what ways does his insect body contradict his opinions and logical decisions? Explain how Gregor’s physical transformation led to his mental change.

- Elaborate on the point of view of The Metamorphosis . Why is it crucial that we see the story from Gregor’s perspective? How does it change the narrative? Speculate on whether Kafka was writing from his point of view as well.The Limited Third-Person Narrator in Kafka’s The Metamorphosis. Essay

- Explore the publishing of the novella. Why was the publishing delayed for three years? Find information about the problems regarding the historical context (particularly World War I) and Kafka’s life that led to troubles with the release of The Metamorphosis .

- Examine Gregor’s initial reaction to his transformation. What’s peculiar about it? How does it enhance the surrealism of the situation? Speculate on the ups and downs of the transformation for Gregor. How did his reaction to his new form change?

- Consider the role of Gregor’s job. Why may have Kafka decide to make him a traveling salesman? How did his occupation affect his life? Examine Gregor’s reflections concerning his job, colleagues, and his boss with examples. Mention the conspiracy with the money that the chief clerk brings up in Chapter 1 .

- Talk about the family theme . What was the initial reaction of each member of the Samsa family on Gregor’s transformation? How did their behavior towards the new Gregor change with time? Explain why they struggle with feeling empathy and sympathy towards an insect.

- Elaborate on the role of money. Why was Gregor the sole supporter of the family before his transformation? How did his parents and sister deal with the financial aspect of life after him becoming an insect? Consider Gregor’s feelings about the subject before his transformation, right after, and near the end of the novella. Was his family angry at him for the inability to support them?

- Examine the kind of insect Gregor turns into. What are the most popular interpretations and suggestions concerning the type of bug? Why did Kafka make it as ambiguous as possible? Mention how Kafka insisted on making a cover for The Metamorphosis without a definite cockroach and provide different translations of the original word for the bug.

- Compare Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis and Joseph Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness . What elements are present in both novellas? What features the main characters have in common? Compare the themes of the novellas and explain what movements influenced the authors.

- Analyze the relationship between Gregor and his father. What’s Mr. Samsa’s initial reaction to Gregor’s new form? Does it change? Consider Gregor’s responses to his father’s violent behavior after the transformation. Why was Mr. Samsa angry at his son throughout the novella?

- Explore the historical context. What was happening in the world and Prague in particular when Kafka was writing The Metamorphosis ? What technological advancements were presented to the public eye? Which philosophical tendencies were popular? Elaborate on everything that could’ve influenced Kafka’s novella.

- Comment on Grete’s violin. Why is the violin crucial for Grete’s and Gregor’s relationship? When does it appear? How does the violin concert in Chapter 3 affect the story? Mention how Grete’s mother accidentally broke the violin and explain what this action symbolizes.

- Examine Kafka’s relationship with his father. What do we know about their connection? How is it reflected in the relationship between Gregor and Mr. Samsa?

- Elaborate on Gregor’s room. What furniture and other objects are located in his room? How do they establish Gregor’s personality? Explain why it upsets and satisfies Gregor when his mother and sister move the furniture away from his room. What object does he desire to keep the most, and why?

- Talk about Gregor’s reaction to the chief clerk’s appearance. Why is Gregor scared? How does he react to the clerk’s allegations? Is he afraid of disappointing his family? Speculate on why Gregor is alarmed by this messenger and what role money plays in the conflict.

- Consider the relationship between Grete and Gregor. How does the connection between them differ from that of Gregor and any other person? How does it change after his transformation? Analyze Grete’s attitude towards her brother and why she was the one to ask the rest of the family to get rid of Gregor. Why did she take care of Gregor and his room alone and then stopped?

- Compare and contrast the attitudes towards Gregor. How does each character react to Gregor’s insect form? Elaborate on the father’s violent behavior, the mother’s fear and pity, and the sister’s sympathy and disgust. Then mention the chief clerk’s fear and the curiosity of the charwoman. Why was she the one who got rid of Gregor’s body?

- Comment on Gregor’s guilt. What does Gregor feel guilty about? Provide his reasons for this feeling from the novella, concentrating on the second half of Chapter 2 . What impact does his guilt have on the ending of The Metamorphosis ?

- Analyze the chief clerk’s appearance in Chapter 1. Why did he come to the Samsa’s apartment? Why was he annoyed by Gregor’s behavior? Why did he decide to talk about the conspiracy that Gregor had been stealing money? Mention the attitude of the family members towards him.

- Examine how the Samsa’s family reacted to Gregor’s death. What did each member of the family feel? Why did the father kick the lodgers out of the house? Why were they annoyed by the charwoman’s reaction? Express how hopeful they were in the end and ready to move on.

- Compare the father-son relationships in The Metamorphosis and Oedipus the King . What features do the father characters share? How did the relationships with the respective fathers influence the lives of Gregor and Oedipus? Elaborate on the upbringing of the characters and their impact on future choices.

- Speculate on the inspiration for the novella. How did Kafka develop the idea for The Metamorphosis ? Explore his feeling of isolation, his one-sided romance with Felice Bauer. Analyze the relationship with his father that could have laid the foundation of The Metamorphosis . What philosophical movements may have affected the story as well?

- Elaborate on the portrait of a woman in furs. How do the picture and its frame look like? Speculate on why Gregor keeps this picture in his room and what it symbolizes for him. Why does he hold on to it the most when Mrs. Samsa and Grete take other furniture out of his room?

- Consider the language of The Metamorphosis . What language did Kafka use? Why? How does it affect the tone of the novella? Find prime examples of the ambiguous wording that led to various translations.

- Explore the Kafkaesque style of The Metamorphosis . What does the term Kafkaesque mean? Why is the novella considered an example of Kafkaesque writing? List the aspects from The Metamorphosis that help to define the style.

- Talk about the character of Mr. Samsa. What are his key traits? Elaborate on what his attitude towards Gregor was before and after his transformation. How did Mr. Samsa change by the end of the novella? Elaborate on his attachment to his uniform and willingness to kill his son at the end of Chapter 2. What were his relationships with his wife and daughter?

- Speculate on why Gregor may have turned into an insect. Find the theories that explain his transformation and provide your opinion. Could his isolation and loneliness before the events of the novella cause his metamorphosis? Could the sacrifices he made for his family lead to the transformation?

- Explore Gregor’s mental transformation. How did the transformation of his body affect his mind? How does his thought process change over time? Express how Gregor’s perception changed, how he started to view himself and the others. Mention the impact that the music had on him and his sense of identity.

- Analyze the relationship between Gregor and his mother. What does her monologue during the chief clerk’s visit reveal about her attitude towards her son? Does she understand him? Explain why she agrees not to visit him, even though she desires to see Gregor after his transformation. Elaborate on the “unfortunate son” quote .

- Examine the supporting characters of the novella. How can the reader view the world outside of the Samsa’s apartment through the lodgers, the chief clerk, and the charwoman? Why are these characters introduced in the novella? Analyze each one of them and the role they play in the story.

- Talk about the reasons why Grete wants to take care of Gregor alone. Why does she start to take care of him in the first place? Was she attentive? Did the reasons for such a treatment change or transformed? Why didn’t Grete let anyone help her, including her mother? Provide Gregor’s thoughts concerning the subject. Why did Grete couldn’t bear taking care of him by the end of the novella?

- Speculate on why it’s an insect that Gregor turned into. Is it crucial that Gregor transformed into a bug and not into any other creature? Express your opinion on all the possible reasons why it should’ve been an insect, whether due to its disgusting appearance, inability to talk, or any other significant aspect. Could’ve Gregor’s lack of self-worth led to taking the form of this particular creature?

- Compare how Grete and her mother treat Gregor as opposed to the charwoman. Why isn’t charwoman disgusted or terrified by Gregor? Speculate on whether the difference in their treatment comes from the lack of caring about Gregor on behalf of the charwoman or not knowing him as a human and viewing him solely as an insect. Does the fact that she isn’t burdened by his existence affect her approach?

- Consider Gregor’s inner monologue. As Gregor lost his ability to speak and isn’t allowed to go out, he’s stuck in the room alone with his thoughts. What does the reader learn about him as a character through his inner monologue? What is his attitude towards the world outside and his family?

- Elaborate on the theme of alienation . Did Gregor feel alienated before the transformation? How did his insect body exacerbate his alienation? Explain what role the theme plays in Gregor’s worsening condition and how Kafka expressed his isolation through Gregor’s story.

- Explain how Gregor’s and Grete’s roles in the family changed. At the beginning of The Metamorphosis , Gregor was the leading supporter of the family, while Grete was a young woman without an occupation, aka a useless burden in the eyes of the family. By the end of the story, their roles changed. How did it happen? How did it affect the attitude towards Grete? Explore what impact the new status had on Grete and her attitude towards Gregor.

- Explore Gregor’s physical and mental injuries. How did Gregor suffer from injuries before and after the transformation (exemplify the knife cut that he recalls)? How does he get hurt throughout the novella? Examine how Gregor’s psychological turmoils correlate with his physical damages.

- Talk about Mr. Samsa’s uniform. How did the uniform initially change Mr. Samsa? Analyze the moment from the end of Chapter 2 where Gregor sees his father in the uniform clearly for the first time. What does Gregor feel? Compare this moment to the later transformation of the uniform and the father in Chapter 3. Explain the connection between Mr. Samsa and this clothing.

- Speculate on the correlation between the imagery and Gregor’s emotional state. How does the use of imagery reflect the inner conflicts and emotions of the main character? Elaborate on the striking imagery with the examples from the text and prove their connection with Gregor’s psychological state.

- Explain why it’s improbable that the story happened in Gregor’s dream or imagination. How does the first line of the novella ruin the allegation that Gregor is dreaming? Find examples from the text that support the idea that everything is happening in the real world. How do the family members and the supporting characters also contradict the theory?

- Comment on the Marxist Interpretation of The Metamorphosis . How can the conflict between the Proletariat and the Bourgeois be found in the novella? How does Gregor’s hatred towards his job contribute to it? Does the job have a dehumanizing effect on the main character? Add examples from the text that illustrate the financial concerns of the family.

- Analyze one film adaptation of the novella. Choose one adaptation and compare it to the source material. How did the director handle the image of the insect form? Is the movie true to the original, or had too many changes?

- Examine the moment when Mr. Samsa explains the financial situation to the family. What new information does Gregor find out? What’s his reaction? Why does the family decide to look for jobs right away when they can live off the savings for about a year?

- Elaborate on Gregor’s dreams. What does Gregor desire the most? What does he want for himself, his family, and his sister in particular? Talk about his ambitions and wishes; describe his dream for his sister and how it changed a bit in Chapter 3 .

- Speculate on the significance of the door. The critical thing that physically separates Gregor from his family is the door in his room. How does the level of sympathy correlate with the opening of the door? Express how the family members tried to open it in Chapter 1, then kept it locked in Chapter 2, and decided to leave it open every evening in Chapter 3.

- Consider Gregor’s perception of his insect body. Does Gregor know how he looks? Can he predict the other people’s reactions that his body may cause? Speculate on why Gregor doesn’t realize how disgusting he looks to other people before he gets a response from them. How and why does he start hiding from others and then stop doing so?

- Explore the theme of self-sacrifice . How does Gregor sacrifice his freedom and happiness for his family before the transformation? How does Gregor sacrifice his comfort and his desire to communicate with others after turning into the bug? Talk about his death as the last act of service and sacrifice for his family.

- Analyze the role of communication. How does Gregor’s inability to speak affect the story? Speculate on what could have happened concerning his relationships with the Samsa family if Gregor could talk. How does the lack of conversations reflect the state of the family?

- Examine the aspect of sympathy in The Metamorphosis . Who felt sympathy towards Gregor? Why was all the sympathy from the family lost after the incident with the lodgers? Explain why characters found it challenging to feel positive emotions towards the insect. According to the novella, is it possible to live with such a creature and feel sympathy towards it?

- Elaborate on the symbolism. What are the most prominent symbols in the novella? Express your thoughts about each one and explain their role in the story. Why did Kafka use a few of them in such a short novella?

- Talk about the character of Gregor. What does Gregor value in life? Explain what his relationships are within and outside of the Samsa family. What does he desire the most? Elaborate on the sacrifices that he made for his family.

- Consider Gregor’s humanity. Gregor feels like he’s losing his identity, as he’s turning in the insect on the inside. Can the reader conclude that he saved his human side by the end of The Metamorphosis ? Does his family think so? Mention Gregor’s reaction to music in Chapter 3.

- Explore Grete’s compassion towards Gregor. How does Grete take care of her brother after the transformation? In what ways does she show her sympathy towards him? How do Gregor and the reader understand that Grete stopped caring about him? Elaborate on the moment when she loses her sympathy.

- Speculate on the meaning of the family’s surname. There is the word “samja” in the Czech language that means “being alone.” Knowing that Kafka lived in Prague while writing the novella, can we suspect that he chose the surname Samsa for a reason? Talk about who can be considered lonely in the family.

- Compare and contrast Mr. and Mrs. Samsa. What are their significant differences? How do their attitudes towards their son differ? Explain that the characters express the polar opposite behaviors throughout the story . How do they treat Gregor and Grete before and after the transformation?

- Elaborate on the moment when the human and insect sides of Gregor clash. When does it happen? Why? List all the moments of such confusion (taking out the furniture, changing the food, crawling, swinging from the ceiling) that show how Gregor struggles from his human mind and insect desires.

- Talk about a cure for Gregor. Why did no one call for a doctor? Why didn’t any family member, even Gregor, try to think of a cure for Gregor’s condition? Reflect on the reason for such behavior and how it affects the reader’s interpretation of the story.

- Analyze the themes of The Metamorphosis . What are the major themes of the story? Consider each one of them and their role in the story. Was there a reason why Kafka wanted to elaborate on these particular themes in the novella?

- Examine the symbolism of the writing desk. What does the desk represent? How does Gregor react when his sister and mother try to move it away from his room? Why? Elaborate on the way Gregor clings to his vanishing human side and how it contradicts his insect needs.

- Consider the ending of the novella. Talk about Gregor’s death: was it a noble sacrifice or a tragic one? What does the Samsa family feel? Describe the ending of The Metamorphosis and explain why it sounds hopeful.

- Explore how the plot of The Metamorphosis contradicts Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory. As opposed to Darwin’s revelation that biological forms evolve over a long time to become more complex and adapted, Gregor Samsa, in a moment, turned into a less perfect yet more primal creature. Compare and contrast Gregor’s de-evolution with Darwin’s theory.

- Talk about the weather in the novella. When is it described? What is the significance of the weather at the beginning and the end of The Metamorphosis ? What atmosphere and does it highlight?

- Compare movie adaptations of The Metamorphosis . What are the significant differences between the two films? How did the directors deal with narration and inner monologue? Present the examples from both movies to explain which one, in your opinion, is better or more accurate to the source material.

- Analyze the stage adaptations. Find information about the most prominent stage adaptations of the novella and speculate on what makes them so successful. How is Gregor’s insect form presented? How does the set look like?

- Examine modernism in The Metamorphosis . What modernistic features does the novella bear? On what modernistic themes does Kafka elaborate? Explain how the movement affected the author and his work.

- Consider humor in the novella. Can this story be called a funny one? What types of humor did Kafka incorporate? Talk about the use of irony in The Metamorphosis . Discuss the amusing contrast between the surreal events and the matter-of-fact tone of the narration.

- Elaborate on the symbolism of the windows. When and why did Gregor develop an attachment to the windows in his room? What does Gregor see through them? Explain that the only form of freedom that Gregor can afford comes from viewing the outside world through the windows. Add how Gregor abandoned them in Chapter 3 due to his medical condition and the lack of hope.

- Talk about the genre of The Metamorphosis . Why is it tricky to define the novella’s genre right away? What genres of fiction are the most notable? Provide proof from the text to elaborate on your position.

- Speculate on the significance of the number 3. Find all the instances where the number occurs (time of Gregor’s death, amount of lodgers and doors, the number of chapters, etc.) and provide your explanation for its incorporation in the story.

- Analyze the passage of time. How does time create tension at the beginning of Chapter 1? How does Gregor’s perception of time change as the days go by? Mention how Chapter 1 lasts only a morning, while the other chapters last a lot longer. Why is the passage of time vital for the family after Gregor’s metamorphosis?

- Examine the role of the 3 lodgers. Why did they start living with the Samsa family? What do they represent in the novella? Explore their presence, reaction to Gregor’s form, and the dynamic within the group. Why did Mr. Samsa demand them to leave? What does the relationship between the family and the lodgers signify?

- Evaluate Freud’s influence on the themes of The Metamorphosis . What Freudian theories can be found in the novella? Analyze the plot according to the interaction of 3 parts of Gregor’s mind (Id, Ego, Superego) and the Oedipus complex.

Thank you for reading! We hope that now you have enough ideas and inspiration to write your paper on The Metamorphosis . You can check other articles about the story and essay samples for a better understanding of its themes.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

Study Guide Menu

- Short Summary

- Chapter III

- Characters Analysis

- Symbols & Literary Analysis

- Important Quotes

- Essay Samples

- Essay Topics

- Author’s Biography

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, August 13). 77 Unique Metamorphosis Essay Topics [with Examples]. https://ivypanda.com/lit/study-guide-on-the-metamorphosis/unique-essay-topics-with-examples/

"77 Unique Metamorphosis Essay Topics [with Examples]." IvyPanda , 13 Aug. 2023, ivypanda.com/lit/study-guide-on-the-metamorphosis/unique-essay-topics-with-examples/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '77 Unique Metamorphosis Essay Topics [with Examples]'. 13 August.

IvyPanda . 2023. "77 Unique Metamorphosis Essay Topics [with Examples]." August 13, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/lit/study-guide-on-the-metamorphosis/unique-essay-topics-with-examples/.

1. IvyPanda . "77 Unique Metamorphosis Essay Topics [with Examples]." August 13, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/lit/study-guide-on-the-metamorphosis/unique-essay-topics-with-examples/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "77 Unique Metamorphosis Essay Topics [with Examples]." August 13, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/lit/study-guide-on-the-metamorphosis/unique-essay-topics-with-examples/.

example hypothesis science

Advanced Search (Items only)

- Browse Items

- Browse Exhibits

Kafka's Metamorphosis: A Journey of Identity with Language as a Vehicle

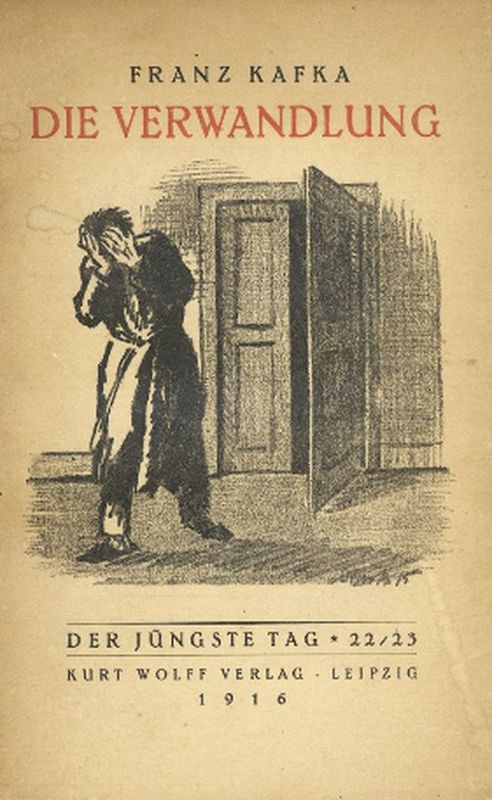

The original cover of Kafka's Metamorphosis , as the author intended it. Ominously, the cover does not contain an image of Gregor Samsa in his transformed state--the nature of his new form is left entirely up to the reader.

Kafka’s Metamorphosis is a magical realist, allegorical tale that touches on the theme most central to us all—that of struggling to find and express one’s own identity in a world of ever-present, all-consuming obligations. As this short essay will explore, the reader leaves the novel feeling unsettled and unsatisfied, imprinted—one might even say scarred—with the message that sometimes the world one lives in makes it impossible to ever express that identity and to have it understood.

The novella opens with a most preposterous scenario , immediately testing, and seeking to expand, the reader’s ability to suspend disbelief. The story’s protagonist, Gregor Samsa, has awoken one morning to find himself “transformed in his bed into a horrible vermin” (7). This first sentence puzzles the reader, as one is not yet sure what to think. What is meant by “vermin,” one wonders? Is Mr. Samsa dreaming? Is the mysterious narrator speaking figuratively? As we read on, we learn that no, Mr. Samsa is not dreaming. The narrator continues on to describe to describe Mr. Samsa’s shivering discovery of his new, grotesque self—“his armor-like back,” “his brown belly, slightly domed and divided by arches into stiff sections,” and “his many legs, pitifully thin” (7). Puzzlingly, however, Mr. Samsa’s reaction is not one of shock or horror. Instead, he refers to his own new form as “nonsense,” and immediately tries with all his might to get himself out of bed so that he can start his day, as though it were like any other.

Mr. Samsa’s reaction from this point on is packed with symbolic meaning. As he tries to get himself out of bed and exclaims “Oh God,” it has nothing to do with his new form! Rather, he completes his sentence by musing, “what a strenuous career it is that I’ve chosen! Travelling day in and day out. ... It can all go to Hell!” (7). He explores more of his new, unsightly body, and continues his thought, noting, “Getting up early all the time, it makes you stupid. ... If I didn’t have my parents to think about I’d have given in my notice a long time ago .... [O]nce I’ve got the money together to pay off my parents’ debt to him – another five or six years I suppose – that’s definitely what I’ll do. First of all though, I’ve got to get up, my train leaves at five” (7-8). Despite having transformed into some ambiguous bug-like creature, Mr. Samsa is so preoccupied by his work as a traveling salesman and his parents’ debt that he is unable to worry about his condition. His only thoughts are how he will get to work and get his family back on solid financial footing. These thoughts continue throughout the work, as Mr. Samsa thinks often about his family’s debt and how they will live without him. He feels his absence only as a provider, rather than a brother, friend, or son.

A trailer for a movie based on Metamorphosis , produced and released in 2012.

A reflective piece in The New Yorker discussing the difficulties in meaning of translating Metamorphosis .

We glean from this opening series of events that Kafka presents Mr. Samsa as a man so utterly controlled by the obligations of his life that his own identity—to the point of his very being as a human—became lost in the mix. Indeed, Kafka sustains this message by maintaining a shroud of mystery around just what Mr. Samsa has become. In the English translation, Mr. Samsa as presented as a “vermin,” “insect,” “dung beetle,” and “bug,” at various points, but the reader never learns for sure. In fact, Kafka was deliberately ambiguous, writing in a letter to his editor before publication that “the insect is not to be drawn,” so that the reader may form his own image (Jones, 2015). Moreover, Kafka’s original German term for Mr. Samsa’s new form, ungeheueres Ungeziefer , “poses one of the greatest challenges to the translator” (Bernofsky, 2014). The term comes from a Middle High German word that means “sacrificial animal” but that also “describes the class of nasty creepy-crawly things.” The English translation of “vermin,” however, evokes the image of a rodent, which is distinct. Though the lack of clarity here might simply stem from the ambiguities of language and translation, one might also view it as an instrument of meaning—that neither the narrator nor Mr. Samsa can precisely describe his new condition signifies the difficulty of coming to terms with one’s identity. Moreover, that Mr. Samsa dies in his new form at the end of the tale leaves the reader with the message that sometimes one becomes wholly swallowed by the various obligations that twist and pull on us all.

The text of a lecture from Professor Warren Breckman at the University of Pennsylvania detailing how Kafka's life may have influenced his writings.

A brief review of Kafka’s family and the context of his life provide added weight to this suggested theme. Indeed, according to those who knew and have studied him, Kafka felt a strong “sense of personal weakness and failure,” and resented his day job as a lawyer and as a bureaucrat with the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute (Breckman, 2000). Just as Mr. Samsa, it seems that Kafka himself struggled to establish his identity—wanting desperately to please his father with his writing, but failing—and devolved into self-loathing. Perhaps Kafka viewed himself as a grostesque alien creature, distant from his family, and fretting about the fiscal obligations around him that he believed prevented him from enjoying his life. In that way, the realist element to Kafka’s magical realist tale comes from his own perspective on his life. While deeply autobiographical in this sense, The Metamorphosis is a tale to which all can relate, as it reminds us powerfully of the glaring monsters within us that we create to shield ourselves from the world.

Bernofsky, Susan. "On Translating Kafka's 'Metamorphosis.'" The New Yorker . 14 January, 2014.

Accessed 23 February 2016.

Breckman, Warren. "Kafka's Metamorphosis in His Time and Ours." Penn Reading Project Lecture .

6 September, 2000. Accessed 23 February 2016.

Jones, Josh. "Franz Kafka Says the Insect in The Metamorphosis Should Never be Drawn; Vladimir

Nabokov Draws It Anyway." Open Culture . 21 October, 2015. Accessed 23 February 2016.

Kafka, Franz. The Metamorphosis . New York: Classix Press, 2009.

My Metamorphosis

"I have always been disillusioned with the limits of human growth," Sabrina Imbler writes. "But insects have a much more fantastic notion of growing up."

For years in my 20s, I wore the wrong shoe size—a 7 when I am actually closer to an 8. I did not know this until I discovered a bunion on my left foot and began ranting to my boyfriend, T, about how all shoes are uncomfortable, how my toes pinched and heels bled, how early hominins may have been right to squelch their naked toes in the soft earth.

T stared at me with polite confusion. “I don’t think shoes are supposed to be uncomfortable,” they eventually responded. They suggested I try on a pair of their shoes, a size up from what I wore. When I slipped my feet inside the shoe, I felt nothing: no squeeze, no pinch, just space. I walked around our apartment, wobbly until I wasn’t. This revelation now seems mortifyingly obvious. But I had become so inured to my ambient discomfort that I assumed everyone felt this way—inconvenienced and constricted by the friction between our bodies and what we use to conceal them.

I have always been disillusioned with the limits of human growth. Even as babies we resemble our future selves, our skin merely stretching, furring, and wrinkling as we age. But insects have a much more fantastic notion of growing up. Their rigid exoskeletons cannot expand with growth, so they molt. They shed old skins and form new ones that are billowing and soft, able to hold more body than before. Some insects like praying mantises undergo transformations with some bodily continuity. They hatch from eggs into tiny wingless adults called nymphs. Nymphs molt into more nymphs, growing larger and sprouting wing buds until the final molt, when the adult emerges like a new, green leaf. But the more famous kind of metamorphosis is more total—that quintessential transmogrification from a caterpillar to chrysalis to butterfly. Born as an egg, growing up as a larva, congealing into a pupa, and unfurling into a winged adult.

.css-lt453j{font-family:NewParisTextBook,NewParisTextBook-roboto,NewParisTextBook-local,Georgia,Times,Serif;font-size:1.75rem;line-height:1.2;margin:0rem;padding-left:5rem;padding-right:5rem;}@media(max-width: 48rem){.css-lt453j{padding-left:2.5rem;padding-right:2.5rem;}}@media(min-width: 64rem){.css-lt453j{font-size:2.5rem;line-height:1.2;}}.css-lt453j b,.css-lt453j strong{font-family:inherit;font-weight:bold;}.css-lt453j em,.css-lt453j i{font-style:italic;font-family:NewParisTextItalic,NewParisTextItalic-roboto,NewParisTextItalic-local,Georgia,Times,Serif;} I had become so inured to my ambient discomfort that I assumed everyone felt this way

It’s idyllic to think that all transitions could be this easy: one form sliding cleanly into another, implying a kind of progression. What could be more aspirational than wings? But molting is no easy feat. A transforming insect cannot eat. Sometimes it cannot move. Mayfly larvae must stop breathing for up to an hour as their exoskeletons slip off. The firebrat, a tiny torpedo that feeds on bookbindings, molts as many as 60 times in the few years it lives. Even for insects, there is no one way to transform. These changes can be creeping; some caterpillars already have tiny wings enclosed, unseen within their bodies. Most caterpillars carry no trace of their past selves after molts. Many will eat the skin they shed, swallowing a past silhouette. But some species cannot bear to part with their old selves. In Australia and New Zealand, a moth called the gum-leaf skeletonizer hoards its old heads, stacking them atop its current head like de-nested Matryoshka dolls. These headpieces grow taller with each molt, tapering into a tower of dead heads that can be nearly half as tall as the caterpillar is long. The display is certainly grotesque. But the many-headed tiara may help the caterpillar avoid the jaws of a predator, offering the gift of a more threatening aura and, perhaps, an extra chance of escape.

Molting is no easy feat.

Maybe this is why I, too, hoard remnants of my past selves. My apartment teems with objects I will never wear again but am afraid to throw away: a sequined chartreuse dress, an unopened vial of hibiscus perfume, a pair of crocodilian heels in a dusty box. Maybe Sabrina—a name that conjures a mold I often do not fit, a name that many of my friends do not use—is also a head I will cast off when I am ready. Maybe hoarding these things makes molting easier, a way of holding onto my past selves. Maybe I will find my way back to them in new ways.

Like all caterpillars, the gum-leaf skeletonizer caterpillar eventually stiffens into a pupa, the protective cocoon in which it will dissolve its body into unrecognizable goo. Here, it reshapes itself into an adult, cells dividing into wings, antennae, legs, and genitals. If you cut open the cocoon, the once-caterpillar would be little more than soup. But if you give it time, something as miraculous as a moth might emerge—silky brown wings corrugated like tree bark.

I, too, hoard remnants of my past selves.

For a few months now, each night before bed, I smear my skin with an ooze that has the power to reshape my body. At first, it felt like nothing was happening, my human form as rigid as ever. But lately, I can feel myself shifting: thrumming gravel in my voice, pimples on my chin, a pinkish bulge that is now larger than an almond, a newly incandescent desire for sex. But unlike something shielded in a cocoon, my soft body is out in the world. Everyone around me is witness to my transformation, whether they know it or not. I karaoke through my voice cracks, hovering between octaves in search of the safest place to land.

In truth, I do not know where that will be. But I know this: I deserve to be comfortable. I deserve to feel at home in my body and what surrounds it. Because in spite of all the voice cracks and pimples and other embarrassments of a second puberty, I have never felt lighter, more free. Because molting is an act of love. It is a promise that you will grow into yourself and your wild and unexpected future. It is a promise to trust the process, that even mired in goo and guts, something like bliss may wait on the other side.

Sabrina Imbler is currently a staff writer at Defector, where they cover creatures. Previously Sabrina worked as a reporting fellow on the science and health desk of The New York Times. They have received fellowships or scholarships from Tin House, the Asian American Writers’ Workshop and Jack Jones Literary Arts. Sabrina’s first book, an essay collection about sea creatures called HOW FAR THE LIGHT REACHES, is out December 2022 with Little, Brown.

Tracing the Legacy of Slavery Through Sculpture

Tierra Whack on Her Most Personal Project Yet

Yara Shahidi Will Host S2 of Cartier's Podcast

100 Empowering Quotes from Inspiring Women

Discovering Joy's Many Layers at a Haunted Retreat

Kim Gordon Is an Artist First, Musician Second

Can Matronage Shift Art’s Gender Imbalance?

Chella Man Is Done Explaining His Existence

The Gay Elders Saving a Part of Black History

Finding Myself in the Queerness of Nature

Jacob Collier on His “Most Ambitious” Project Yet

In an age of minimalism, here’s a celebration of more, more, more

In ‘all things are too small,’ washington post book critic becca rothfeld argues for surplus in love and art.

Printed matter permeates my premises.

To my spouse’s chagrin, books and magazines in our house pile up on shelves and tables, in corners and drawers. The basement has boxes of New Yorker issues dating to the beginning of my subscription, in 2002. The hauling of these boxes — to six residences across three states — is my decades-long performance-art piece: “The Sunk-Cost Follies.”

And so I read Becca Rothfeld’s evisceration of Marie Kondo and her decluttering cronies, in an essay from her new book, with vindication. In Kondo’s abominable advice to rip out and keep only certain favorite pages from your books before getting rid of them, Rothfeld diagnoses the problem as the Philistine’s assumption that “language is a vehicle for the transfer of information, never a source of pleasure in its own right.”

Rothfeld, The Washington Post’s prolific and provocative nonfiction book critic, “lapsed academic philosopher” and recent winner of the National Book Critics Circle’s Nona Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing, never forgets that language is a pleasure source. She celebrates those writers who would “touch every last word” and skewers those who replace “explanation with intimation,” opting for less when more will always do.

“ All Things Are Too Small: Essays in Praise of Excess ” is Rothfeld’s first book, and in it she stakes out her dissent from the culture’s “adventures in parsimony.”

“At every turn,” she writes, “we are inundated with exhortations to smallness: short sentences stitched into short books, professional declutterers who tell us to trash our possessions, meditation ‘practices’ that promise to clear the mind of thought and other detritus, and nostalgic campaigns for sexual restraint.”

Across 12 essays — five of them previously published — Rothfeld makes an impassioned case for cacophony.

Her plea for abundance opens with an insistence on the ability — the imperative — to dislike or discriminate. She argues that political commitments to egalitarianism (she’s described herself as a “Rawlsian socialist”) needn’t commit one to a correspondingly democratic attitude toward every cultural or interpersonal endeavor. We don’t have to love all our friends (or art) the same: “The kind of creatures for whom love and art mean anything at all are the kind with biases and aversions.”

Rothfeld’s language is often extravagant, luxuriating in alliteration and internal rhyme: “The oozing oddity of embodiment, in particular, requires hyperbole.”

That sentence is from an essay in which, at play on the page, she ties together the work of horror-film master David Cronenberg, philosophical ideas about the nature of truly transformative experience and the first flush of her romance with the “alien entity” who “was eventually to become my husband.”

She argues that Cronenberg’s “chief innovation,” in films like “Dead Ringers” and “The Fly,” is the recognition that “whether lusting and falling in love are more like body horror or more like reincarnation is merely a matter of emphasis.”

This is Rothfeld at her very best, dancing across media, experience and scholarship to deliver a surprising conclusion. That essay, “The Flesh, It Makes You Crazy,” is the first of three in which she considers the problem of mere consent in light of her call for romantic abandon: “We cannot know what sort of metamorphosis will ensue if the sex is as jarring as we can only hope it will be” and “we cannot consent to total metamorphosis.”

For the narrators of what Rothfeld, in another essay, calls “the fragment novel,” there is no change of any kind — much less total — on the table.

In these short books of short sentences, by writers such as Jenny Offill and Kate Zambreno, Rothfeld sees “an artwork from which the art has been removed, a body drained of all its blood and carnality.” And she laments, in their rise in popularity, a Kondo-fication of American fiction.

Rather than psychic verisimilitude — that these books are a representation on the page of being too sad and defeated to care — Rothfeld sees a “performance of profundity.”

“Why clarify when it is so much more efficient to nod at clarification?” she asks. “Why think when you can mimic thinking?”

But isn’t it also true that we think in fragments?

Or maybe that “we” is doing a lot of work here. There are those of us without Rothfeld’s seemingly full control of her ideas and syntax; we sacks of synapses sometimes need a tool for when too many axons light up at once.

Some of us less able to make the fragments cohere derive use from certain meditative “practices” (the scare quotes are Rothfeld’s), which come under sustained attack in “Wherever You Go, You Could Leave,” the book’s second-longest essay. Here I’ll disclose that, though I once shared Rothfeld’s skepticism of this kind of thing, I have more recently found relief via an approach called “Mindful Self-Compassion.” (The quotes, in this case, are mine, and I cringe to imagine Rothfeld rolling her eyes.)

Rothfeld opens her chapter on mindfulness with her own bit of autobiography: “My first year of college, I attempted suicide and was promptly hastened home.” To return to school, she had “to undergo something cumbersomely called ‘cognitive behavioral therapy.’” (The scare quotes, again, are hers.)

At her therapist’s urging, she started running. She went to the movies. Both helped. She also tried to “practice mindfulness.” It didn’t help. At all.

“Non-judgmental awareness,” the goal of the meditation that was suggested to her, is Rothfeld’s own special hell. It “sounded to me indistinguishable from depression or desolation or whatever it was that rendered the minutes too long to endure and their inhabitants too listless to detest even detestable things.”

By now, we understand why. Asking Rothfeld to surrender her judgmental faculties is like asking Steph Curry to stop shooting threes. It’s fundamental to her self-conception, and she’s great at it.

In this light, her allergy to the Mindfulness-Industrial Complex is easy to understand. But that allergy can lead her into caricature. She looks for the worst, and she finds it.

It’s difficult to define mindfulness as a coherent movement in the first place. Rothfeld uses as her avatar Jon Kabat-Zinn, whose groovy baby boomer ramblings are ripe for parody. She then traces — not entirely persuasively — a connection between mindfulness and “mind cure,” the turn-of-the-20th-century movements that included Christian Science and New Thought, “in which mental ministrations have masqueraded as balms for the body.”

Rothfeld quotes, but does not take, the off-ramp that philosopher William James offered on this question: “Mind-cure gives to some of us serenity, moral poise, and happiness.” She is less forgiving: “If mindfulness were presented not as a panacea or a metaphysical system but as one technique among many for keeping the wolves at bay, I could look on it kindly.”

Depending on your framing, mindfulness does not have to be presented as either a panacea or a full cosmology. Rothfeld’s own cognitive-behavioral therapist, in the wake of the cataclysmic episode that opens the essay, presented mindfulness “as one technique among many.” She could look on it kindly but chooses not to.

A hint as to why might be found elsewhere in this book. In her paean to Norman Rush’s novel “Mating,” Rothfeld says that “the drama of Rush’s opus is emotional, yes, but it is also and primarily intellectual.” His characters catch “cherished ephemera in the net of their relentless overanalysis.”

The drama of reading Rothfeld is primarily — thrillingly — intellectual, and her analysis is indeed relentless. It’s impossible to do justice to each of her arguments in the space allotted, but I’ve aimed to evoke the pleasure of reading “All Things Are Too Small”: Having just recovered from a dazzling insight, we might be provoked to argue with her (one can imagine she likes it that way), and we are never bored.

Sebastian Stockman is a teaching professor in the English department at Northeastern University and the writer of an infrequent newsletter, “A Saturday Letter.”

All Things Are Too Small

Essays in Praise of Excess

By Becca Rothfeld

Metropolitan. 285 pp. $27.99

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

- Share full article

There’s an Explosion of Plastic Waste. Big Companies Say ‘We’ve Got This.’

Big brands like Procter & Gamble and Nestlé say a new generation of plants will help them meet environmental goals, but the technology is struggling to deliver.

Recycled polypropylene pellets at a PureCycle Technologies plant in Ironton, Ohio. Credit... Maddie McGarvey for The New York Times

Supported by

By Hiroko Tabuchi

- April 5, 2024

By 2025, Nestle promises not to use any plastic in its products that isn’t recyclable. By that same year, L’Oreal says all of its packaging will be “refillable, reusable, recyclable or compostable.”

And by 2030, Procter & Gamble pledges that it will halve its use of virgin plastic resin made from petroleum.

To get there, these companies and others are promoting a new generation of recycling plants, called “advanced” or “chemical” recycling, that promise to recycle many more products than can be recycled today.

So far, advanced recycling is struggling to deliver on its promise. Nevertheless, the new technology is being hailed by the plastics industry as a solution to an exploding global waste problem.

The traditional approach to recycling is to simply grind up and melt plastic waste. The new, advanced-recycling operators say they can break down the plastic much further, into more basic molecular building blocks, and transform it into new plastic.

PureCycle Technologies, a company that features prominently in Nestlé, L’Oréal, and Procter & Gamble’s plastics commitments, runs one such facility, a $500 million plant in Ironton, Ohio. The plant was originally to start operating in 2020 , with the capacity to process as much as 182 tons of discarded polypropylene, a hard-to-recycle plastic used widely in single-use cups, yogurt tubs, coffee pods and clothing fibers, every day.

But PureCycle’s recent months have instead been filled with setbacks: technical issues at the plant, shareholder lawsuits, questions over the technology and a startling report from contrarian investors who make money when a stock price falls. They said that they had flown a drone over the facility that showed that the plant was far from being able to make much new plastic.

PureCycle, based in Orlando, Fla., said it remained on track. “We’re ramping up production,” its chief executive, Dustin Olson, said during a recent tour of the plant, a constellation of pipes, storage tanks and cooling towers in Ironton, near the Ohio River. “We believe in this technology. We’ve seen it work,” he said. “We’re making leaps and bounds.”

Nestlé, Procter & Gamble and L’Oréal have also expressed confidence in PureCycle. L’Oréal said PureCycle was one of many partners developing a range of recycling technologies. P.&G. said it hoped to use the recycled plastic for “numerous packaging applications as they scale up production.” Nestlé didn’t respond to requests for comment, but has said it is collaborating with PureCycle on “groundbreaking recycling technologies.”

PureCycle’s woes are emblematic of broad trouble faced by a new generation of recycling plants that have struggled to keep up with the growing tide of global plastic production, which scientists say could almost quadruple by midcentury .

A chemical-recycling facility in Tigard, Ore., a joint venture between Agilyx and Americas Styrenics, is in the process of shutting down after millions of dollars in losses. A plant in Ashley, Ind., that had aimed to recycle 100,000 tons of plastic a year by 2021 had processed only 2,000 tons in total as of late 2023, after fires, oil spills and worker safety complaints.

At the same time, many of the new generation of recycling facilities are turning plastic into fuel, something the Environmental Protection Agency doesn’t consider to be recycling, though industry groups say some of that fuel can be turned into new plastic .

Overall, the advanced recycling plants are struggling to make a dent in the roughly 36 million tons of plastic Americans discard each year, which is more than any other country. Even if the 10 remaining chemical-recycling plants in America were to operate at full capacity, they would together process some 456,000 tons of plastic waste, according to a recent tally by Beyond Plastics , a nonprofit group that advocates stricter controls on plastics production. That’s perhaps enough to raise the plastic recycling rate — which has languished below 10 percent for decades — by a single percentage point.

For households, that has meant that much of the plastic they put out for recycling doesn’t get recycled at all, but ends up in landfills. Figuring out which plastics are recyclable and which aren’t has turned into, essentially, a guessing game . That confusion has led to a stream of non-recyclable trash contaminating the recycling process, gumming up the system.

“The industry is trying to say they have a solution,” said Terrence J. Collins, a professor of chemistry and sustainability science at Carnegie Mellon University. “It’s a non-solution.”

‘Molecular washing machine’

It was a long-awaited day last June at PureCycle’s Ironton facility: The company had just produced its first batch of what it describes as “ultra-pure” recycled polypropylene pellets.

That milestone came several years late and with more than $350 million in cost overruns. Still, the company appeared to have finally made it. “Nobody else can do this,” Jeff Kramer, the plant manager, told a local news crew .

PureCycle had done it by licensing a game-changing method — developed by Procter & Gamble researchers in the mid-2010s, but unproven at scale — that uses solvent to dissolve and purify the plastic to make it new again. “It’s like a molecular washing machine,” Mr. Olson said.

There’s a reason Procter & Gamble, Nestlé and L’Oréal, some of the world’s biggest users of plastic, are excited about the technology. Many of their products are made from polypropylene, a plastic that they transform into a plethora of products using dyes and fillers. P.&G. has said it uses more polypropylene than any other plastic, more than a half-million tons a year.

But those additives make recycling polypropylene more difficult.

The E.P.A. estimates that 2.7 percent of polypropylene packaging is reprocessed. But PureCycle was promising to take any polypropylene — disposable beer cups, car bumpers, even campaign signs — and remove the colors, odors, and contaminants to transform it into new plastic.

Soon after the June milestone, trouble hit.

On Sept. 13, PureCycle disclosed that its plant had suffered a power failure the previous month that had halted operations and caused a vital seal to fail. That meant the company would be unable to meet key milestones, it told lenders.

Then in November, Bleecker Street Research — a New York-based short-seller, an investment strategy that involves betting that a company’s stock price will fall — published a report asserting that the white pellets that had rolled off PureCycle’s line in June weren’t recycled from plastic waste. The short-sellers instead claimed instead that the company had simply run virgin polypropylene through the system as part of a demonstration run.

Mr. Olsen said PureCycle hadn’t used consumer waste in the June 2023 run, but it hadn’t used virgin plastic, either. Instead it had used scrap known as “post industrial,” which is what’s left over from the manufacturing process and would otherwise go to a landfill, he said.

Bleecker Street also said it had flown heat-sensing drones over the facility and said it found few signs of commercial-scale activity. The firm also raised questions about the solvent PureCycle was using to break down the plastic, calling it “a nightmare concoction” that was difficult to manage.

PureCycle is now being sued by other investors who accuse the company of making false statements and misleading investors about its setbacks.

Mr. Olson declined to describe the solvent. Regulatory filings reviewed by The New York Times indicate that it is butane, a highly flammable gas, stored under pressure. The company’s filing described the risks of explosion, citing a “worst case scenario” that could cause second-degree burns a half-mile away, and said that to mitigate the risk the plant was equipped with sprinklers, gas detectors and alarms.

Chasing the ‘circular economy’

It isn’t unusual, of course, for any new technology or facility to experience hiccups. The plastics industry says these projects, once they get going, will bring the world closer to a “circular” economy, where things are reused again and again.

Plastics-industry lobbying groups are promoting chemical recycling. At a hearing in New York late last year, industry lobbyists pointed to the promise of advanced recycling in opposing a packaging-reduction bill that would eventually mandate a 50 percent reduction in plastic packaging. And at negotiations for a global plastics treaty , lobby groups are urging nations to consider expanding chemical recycling instead of taking steps like restricting plastic production or banning plastic bags.

A spokeswoman for the American Chemistry Council, which represents plastics makers as well as oil and gas companies that produce the building blocks of plastic, said that chemical recycling potentially “complements mechanical recycling, taking the harder-to-recycle plastics that mechanical often cannot.”

Environmental groups say the companies are using a timeworn strategy of promoting recycling as a way to justify selling more plastic, even though the new recycling technology isn’t ready for prime time. Meanwhile, they say, plastic waste chokes rivers and streams, piles up in landfills or is exported .

“These large consumer brand companies, they’re out over their skis,” said Judith Enck, the president of Beyond Plastics and a former regional E.P.A. administrator. “Look behind the curtain, and these facilities aren’t operating at scale, and they aren’t environmentally sustainable,” she said.

The better solution, she said, would be, “We need to make less plastic.”

Touring the plant

Mr. Olsen recently strolled through a cavernous warehouse at PureCycle’s Ironton site, built at a former Dow Chemical plant. Since January, he said, PureCycle has been processing mainly consumer plastic waste and has produced about 1.3 million pounds of recycled polypropylene, or about 1 percent of its annual production target.

“This is a bag that would hold dog food,” he said, pointing to a bale of woven plastic bags. “And these are fruit carts that you’d see in street markets. We can recycle all of that, which is pretty cool.”

The plant was dealing with a faulty valve discovered the day before, so no pellets were rolling off the line. Mr. Olson pulled out a cellphone to show a photo of a valve with a dark line ringing its interior. “It’s not supposed to look like that,” he said.

The company later sent video of Mr. Olson next to white pellets once again streaming out of its production line.

PureCycle says every kilogram of polypropylene it recycles emits about 1.54 kilograms of planet-warming carbon dioxide. That’s on par with a commonly used industry measure of emissions for virgin polypropylene. PureCycle said that it was improving on that measure.

Nestlé, L’Oréal and Procter & Gamble continue to say they’re optimistic about the technology. In November, Nestlé said it had invested in a British company that would more easily separate out polypropylene from other plastic waste.

It was “just one of the many steps we are taking on our journey to ensure our packaging doesn’t end up as waste,” the company said.

Hiroko Tabuchi covers the intersection of business and climate for The Times. She has been a journalist for more than 20 years in Tokyo and New York. More about Hiroko Tabuchi

Learn More About Climate Change

Have questions about climate change? Our F.A.Q. will tackle your climate questions, big and small .

The Italian energy giant Eni sees future profits from collecting carbon dioxide and pumping it into natural gas fields that have been exhausted.

”Buying Time,” a new series from The New York Times, looks at the risky ways humans are starting to manipulate nature to fight climate change.

Ocean Conservation Namibia is disentangling a record number of seals, while broadcasting the perils of marine debris in a largely feel-good way. Here’s how .

New satellite-based research reveals how land along the East Coast is slumping into the ocean, compounding the danger from global sea level rise . A major culprit: the overpumping of groundwater.

Did you know the ♻ symbol doesn’t mean something is actually recyclable ? Read on about how we got here, and what can be done.

Advertisement

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The metamorphosis itself forms a central part of these discussions. Explanation: The story'Metamorphosis' is a classic work written by Franz Kaf-ka. In it, the protagonist, Gregor Samsa, awakens one day to find himself transformed into a gigantic insect. Writing an essay on this metamorphosis might focus on themes of alienation, guilt, and ...

Metamorphosis, when you hear this word, you probably think of process of transformation of butterflies, bees, and frogs from an immature to an adult's stage. Metamorphosis is just the development of something from one stage to another. During metamorphosis, insects, and some amphibians go through different processes or stages, just like how ...

It provides him both with a sense of purpose and it created his identity as the money-earner of the family. After his metamorphosis, Gregor struggles with the idea that he can't work and that he no longer acts as the family's breadwinner. He continues to hope that he will suddenly turn back to his former self and return to work.

The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka is a rich and multi-layered work that offers insights into the human condition and the complexities of human relationships. The main themes in The Metamorphosis are isolation, identity, transformation, and family. The theme of isolation is central to the story, as the protagonist Gregor Samsa wakes up one day to ...

Explore the author's fascinating life and literary legacy Metamorosis: A Biography of Franz Kafka. Explore Franz Kafka's 'The Metamorphosis' with our comprehensive study guide. Dive into analysis, uncover themes, and get to know the intriguing characters in this iconic literary work.

The Metamorphosis is a novella by Franz Kafka, first published in 1915. It is a story about a young man named Gregor Samsa who wakes up one day to find that he has transformed into a giant insect. The novella explores themes of isolation, identity, and the human condition. It has become one of Kafka's most famous works and is considered a ...

In Franz Kafka 's The Metamorphosis, Gregor is not the only one who transforms. His sister, Grete, morphs from being Gregor's only hope of help to ultimately the cause of his death. When Gregor transforms, the only person who he wishes to see is his sister, Grete. He wants her to come in and save him because …show more content….

77 Unique Metamorphosis Essay Topics [with Examples] by IvyPanda Updated on: Aug 13th, 2023. 13 min. 1,856. When you have to write The Metamorphosis essay, you should find or come up with a solid idea. Our writers developed a number of topics that can help you with your task. In this article, you'll read the ideas for the paper.

The Metamorphosis. The notion of the "extended metaphor," which Sokel considers in an early essay to be "significant" and "interesting" though "insufficient as a total explanation of The Metamorphosis, "5 reemerges in his Writer in Extremis as a crucial determinant of Expres sionism: "The character Gregor Samsa has been transformed into a

As Gregor's mother and sister argue over the removal of furniture from his room, Gregor leaves his space in an attempt to save some of his belongings from being discarded. While he is out, his mother spots him, cries out in horror, and faints. Gregor's father walks in on this scene and, assuming that Gregor committed some act of aggression ...

77 Unique Metamorphosis Essay Topics [with Examples] When you have to write The Metamorphosis essay, you should find or come up with a solid idea. Our writers developed a number o

Discussion of themes and motifs in Franz Kafka's The Metamorphosis. eNotes critical analyses help you gain a deeper understanding of The Metamorphosis so you can excel on your essay or test.

This critical essay aims to analyze the work by examining themes such as isolation, identity, and the symbolism of the transformation. The purpose of this essay is to provide a comprehensive analysis of The Metamorphosis that sheds light on Kafka's literary techniques and the novella's reception.

metamorphosis the metamorphosis 3 pages The human mind is so active that an individual experiences approximately 70,000 thoughts each day. These thoughts are often conflicting in their nature, as the stream of consciousness does not readily divide thoughts into categories, and thoughts enter and exit the mind freely.

SOURCE: "Kafka's 'Metamorphosis' as Death and Resurrection Fantasy," in The American Imago, Vol. 16, No. 4, Winter, 1959, pp. 349-65. [In the following essay, Webster offers a psychoanalytic ...

Kafka's Metamorphosis is a magical realist, allegorical tale that touches on the theme most central to us all—that of struggling to find and express one's own identity in a world of ever-present, all-consuming obligations. As this short essay will explore, the reader leaves the novel feeling unsettled and unsatisfied, imprinted—one might even say scarred—with the message that ...

Their rigid exoskeletons cannot expand with growth, so they molt. They shed old skins and form new ones that are billowing and soft, able to hold more body than before. Some insects like praying ...

April 6, 2024. On a quiet street in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, just a few steps from my back door, is a vacant lot that my wife, Anne, and I share with our neighbors. This patch ...

And so I read Becca Rothfeld's evisceration of Marie Kondo and her decluttering cronies, in an essay from her new book, with vindication. In Kondo's abominable advice to rip out and keep only ...

Explanation: Metamorphosis in Animal Life Cycles: Metamorphosis is a biological process during which an animal physically develops after birth or hatching, involving a conspicuous and relatively abrupt change in the animal's body structure through cell growth and differentiation. This is seen prominently in insects and amphibians, which undergo ...

April 5, 2024. By 2025, Nestle promises not to use any plastic in its products that isn't recyclable. By that same year, L'Oreal says all of its packaging will be "refillable, reusable ...

You need a quote from the book or passage to be able to support whatever your answer is to paragraph 3. Make sure to cite the book and page number. :) You also need transition sentences in your essay. Here's an example: 1st paragraph: [based off of a friend :)] Paranoid or paranormal? My science fair topic was to investigate the things we can't ...

Brainly is the knowledge-sharing community where hundreds of millions of students and experts put their heads together to crack their toughest homework questions. Brainly - Learning, Your Way. - Homework Help, AI Tutor & Test Prep